8 Volumes

BANKS REDEFINED

American banking was invented in Philadelphia. The banking center of America has moved away and changed in extraordinary ways but the foundations remain.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

Philadelphia: Decline and Fall (1900-2060)

The world's richest industrial city in 1900, was defeated and dejected by 1950. Why? Digby Baltzell blamed it on the Quakers. Others blame the Erie Canal, and Andrew Jackson, or maybe Martin van Buren. Some say the city-county consolidation of 1858. Others blame the unions. We rather favor the decline of family business and the rise of the modern corporation in its place.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Worldwide Common Currency and Corporate Headquarters

The Death of Money

Federal Reserve

New volume 2018-11-07 19:37:15 description

Whither, Federal Reserve? (1) Before Our Crash

The Federal Reserve seems to be a big black box, containing magic. In fact, its high-wire acrobatics must not be allowed to fail. Nevertheless, it may be time to consider revising or replacing it.

|

|

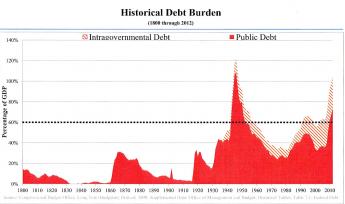

With thanks to: Hon. David M. Walker Founder and CEO The Comeback America Initiative and Former Comptroller General of the United States.

Stephen Girard once personally financed the War of 1812, and before him, Robert Morris had essentially done the same for the Revolutionary War. J.P. Morgan personally financed the Spanish-American War. Since then, American finance has become world finance, immense and too politically sensitive to entrust to bankers, even if their systems could handle the volume. Restoring control of the money supply "to the People" was what the 1913 Federal Reserve was all about. Unfortunately, the monetary system then just grew even bigger and more complex. A mistake might destroy civilization, and in 1929 it seemed it might do it right then and there. Instead of politicians, we think we need financial experts who never make mistakes, but unfortunately in 1929 many mistakes were made by both bankers and experts. We think we have learned a lot about the monetary system since then, and we think Nobel Prize winners have devised a workable system. For twenty years it has indeed seemed to work, because we haven't had another depression; bad inflation is what Austrians had, so they fear it most, and inflation is the other thing that's very bad. But inflation targeting without precious metal reserves, has not stood the test of centuries, and most people could not begin to explain it.

In summary, while we grew uneasy with banker control and political control, the rest of us don't have a clue. We want a Federal Reserve Chairman who explains it to us transparently, but it nevertheless seems better if he keeps his mouth shut. Men who wear beards always look as though they are trying to hide. We need a brand new Chairman, but we need one with a long track record. We want a born winner, but we don't even understand the game well enough to tell who has won. In this sort of confusion our nation always falls back on leaders with character -- Washington, Robert Morris, Ulysses Grant. They play for the breaks, waiting for the other side to make a mistake or quit; the only sure way to lose is to quit.

Monetary Causes of the American Revolutionary War

|

|

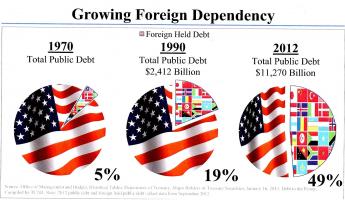

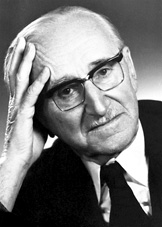

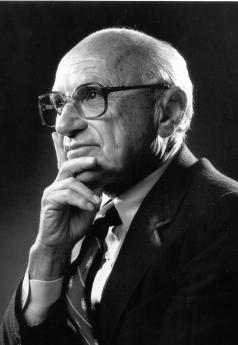

Milton Friedman The Father of Monetarism |

Milton Friedman won the 1976 Nobel Prize in Economics (more accurately, the Bank of Sweden Prize in Memory of Alfred Nobel), for generating controversial ideas made even more annoying to his professional adversaries by his matchless knack for attaching memorable slogans to them. A phrase in question is that "Inflation, always and everywhere, is a monetary phenomenon." Turned around, the converse emerges that the great deflation and depression of the 1930s was caused by a global monetary shortage. Then, to extend the same idea to the American Revolution, it could fairly be argued that inept British contraction of colonial coinage had a lot to do with provoking us to seek independence.

|

| French & Indian War |

Following the French and Indian War, the colonies experienced a major commodity depression which seems to have been caused by wartime shortages followed by post-war surpluses (associated with failure to adjust to the resulting financial confusion). In Milton Friedman's theory, it is the task of any government to maintain stable prices by balancing the amount of currency in circulation with the size of the gross national product. In 1770, the British Exchequer would thus have had to expand and contract the amount of currency in circulation pretty rapidly to maintain economic stability in the bumpy Colonial economy. Essentially, they had to ride a bucking broncho three thousand miles away. In the Eighteenth Century, there was no trace of understanding of the issues involved. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations was only published in the fateful year of 1776, for example. Even if the techniques for maintaining stable prices had been crystal clear, there was a thirty-day lag in communication across the Ocean, and comparable lags between the colonies, where different imports and exports were affected at varying times. So it is a little harsh to blame the British for the chaotic result, except to notice that strongly centralized, the trans-Atlantic government was by nature unsuitable for managing rapidly-changing problems, currency and otherwise. The British government had more than a century of experience that should have made that clear. That's what the colonists said, in effect, and their solution for it was Independence.

|

| George III |

If you believe Friedman, a shortage of coinage causes a fall in prices or deflation. To correct that, you need a central banker constantly fine-tuning the currency. But banking in the colonies was too rudimentary to consider such a thing. If you needed a mortgage, you went to a prosperous neighbor and borrowed directly from him. That was fine because prosperous colonists had limited opportunities to invest their money conveniently, except by loaning money to their neighbors. Indeed, local communities were knit together socially by the mutual assistance of successful farmers directly assisting their less fortunate neighbors. However, pioneer farming

|

| Depression-era Farm Family |

communities are far too unsophisticated to remain tranquil when problems arise out of abstractions. Suddenly and without apparent explanation, in 1770 there was no money for anybody to use, and the fellow with a mortgage on his farm couldn't make his payments even though he was otherwise entirely successful. His creditor himself than couldn't pay his own bills, and eventually, even the kindliest ones were driven to foreclose the mortgage. It was said to be common for a farm worth $5000 to be sold to satisfy a mortgage of $100. And in this way, many honest and once-prospering farmers were forced to walk past their old home, now owned and occupied by a formerly friendly neighbor. It all seemed bitterly unfair, no one understood what was happening, evil motives were readily suspected, and old religious and personal grievances were heightened. When the British finally imposed a total ban on paper money as well as a prohibition of the export of British coinage outside the United Kingdom, things became almost impossible to manage. Almost no one knew exactly what was going on, but everyone could see it was bad. The colonies rapidly deteriorated toward class warfare, which is what the division between Tories and Rebels was soon to become, with both sides quite rightly asserting they were not responsible, and quite wrongly asserting the other must be.

From a far distance, it can be readily perceived the primitive banking and transportation systems of that time were inadequate to respond to the rapidly changing financial problems of a global empire; and it can be readily surmised that many other non-financial issues of governance were similarly hampered by attempting to centralize control over vast distances. In that sense, the colonists were approximately correct in directing their indignation to the person of King George III, whose mother was constantly nagging him to "be a real King". He had the particular misfortune to be dealing with Englishmen, deeply aware of the hidden political agenda made possible in the 13th Century by the Magna Charta and made explicit in 1307, when Edward I agreed not to collect certain taxes without the consent of the realm. Essentially, Parliament placed taxation in the hands of the people, who consistently withheld consent until the king gave them just a little more liberty. This was the reason irksome micromanagement of the distant colonies was immediately countered with the cry of "No taxation without Representation" since membership in the House of Commons was a traditional and historically effective means to the end. But it was getting late for this solution. Maritime New England now wanted to go further than that in order to dominate Western Atlantic trade. Virginia and the rest of the South wanted to go all the way to Independence in order to exploit the vast empty interior wilderness of Ohio and beyond. But the Quaker colonies in the middle felt quite sympathetic with John Dickinson's advice to remain part of the Empire and make a stand for representation in Parliament. When the Lord Howe's British fleet appeared in lower New York harbor an immediate choice had to be made, and ultimately the Quaker colonies were swayed by Benjamin Franklin's embittered report of his mistreatment in Parliament, and his assessment that he could persuade the French to help us. However reluctant they were to resort to force, the Quaker colonies had to choose, and choose immediately: either flee as Tories to Canada, or stand and fight.

Alexander Hamilton, Celebrity

He had the kind of taudry private life and flashy public behavior that Philadelphia will only tolerate in aristocrats, sometimes.

|

It comes as a surprise that most of the serious, important things Alexander Hamilton did for his country were done in Philadelphia, while he lived at 79 South 3rd Street. That surprises because much of his more colorful behavior took place elsewhere. He was born on a fly-speck Caribbean island, the "bastard brat of a Scots peddler" in John Adams' exaggerated view, was orphaned and had to support himself after age 13. The orphan then fought his way to Kings College (now Columbia University) in New York in spite of hoping to go to Princeton, and has been celebrated ever since by Columbia University as a son of New York. He did found the Bank of New York, and he did marry the daughter of a New York patroon, and he was the head of the New York political delegation. As you can see in the statuary collection at the Constitution Center, he was a funny-looking little elf with a long pointed nose, frequently calling attention to himself with hyperkinetic behavior. Even as the legitimate father of eight children, Hamilton had some overly close associations with other men's wives, probably including his wife's sister. Nevertheless, he earned the affection of the stiff and solemn General Washington, probably through a gift of gab and skill getting things done, while outwardly acting as court jester in a difficult and dangerous guerilla war. There is a famous story of his shaking loose from the headquarters staff and fighting in the line at Yorktown, where he insolently stood on the parapet before the British enemy troops, performing the manual of arms. Instead of using him for target practice, the British troops applauded his audacity. Harboring no such illusions, Aaron Burr later killed him in a duel as everyone knows; it was not his first such challenge.

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler told other stories of celeb behavior to reinforce Hamilton's New York flavor. But in the clutch, General Washington learned he could always trust Hamilton, who wrote many of his letters for him and acted as his reliable spymaster. When the first President faced signing or not signing the fateful bill to create the National Bank, a perplexed Washington had to choose between: the violent opposition of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, or the bewildering complexity of Alexander Hamilton's reasoning in arcane economics. On the one hand, there was the simple principle that owing money was seemingly always evil; on the other was the undeniable truth that for every debit created, you create a balancing credit somewhere. Washington ultimately chose to go with Hamilton, whose reasonings he likely didn't understand very well. If you doubt the difficulty, try reading Hamilton's Report on the Bank, written to persuade the nation and its first President of the soundness of his ideas. And then consider the violence of even present-day arguments about such "supply side" economics.

|

| Nicholas Murray Butler |

All of these momentous events happened in Philadelphia at places now easily visited in a morning's stroll. But Hamilton's image as a Philadelphian, doing great things in and for Philadelphia, was forever tarnished at one single dinner he hosted. Jefferson and Madison, his political opponents but his guests, were persuaded to provide Virginia's votes for the federal takeover of state Revolutionary War debts, in return for offering New York's votes for moving the nation's capital to the banks of the Potomac. True, Pennsylvania allowed itself to be pacified with having the capital remain here for ten years while the southern swamps were being drained. But it was Hamilton who cooked up this deal and sold it to the other vote swappers. Philadelphia felt it was entitled to the capital without needing to ask, felt that Hamilton was deliberately under-counting Pennsylvania's war debts, and this city has never appreciated the insolent idea that its entitlements were forever in the hands of wine-swilling hustlers. As the economic consequences of this backroom deal became evident during the 19th Century, it was increasingly unlikely that Philadelphia would lionize the memory of the man responsible for it. Let New York claim him, if it likes that sort of thing. When Albert Gallatin, who was more or less a Pennsylvania home town boy, attacked Hamilton as a person, as a banker, and as a Federalist -- he had a fairly easy time persuading Philadelphians that this needle-nosed philanderer was an embarrassment best forgotten.

REFERENCES

| Alexander Hamilton Ron Chernow ISBN:978-0-14-303475-9 | Amazon |

After the Convention:Hamilton and Madison

|

| Signers |

The Federalist Papers were written by three founding fathers after the Constitution had been completed and adopted by the Convention. Detecting hesitation in New York, the aim was for publication in New York newspapers to persuade that wavering State to ratify the proposal. It is natural that The Federalist was composed of arguments most persuasive to New York, putting less stress on matters of concern to other national regions. This narrow focus may explain the close cooperation of Hamilton and Madison, who must surely have suppressed some latent concerns in order to present a unified position. In view of how much emphasis the courts have placed on the original intent of almost every word in the Constitution, it seems a pity that no one has attempted to reconcile the words of the principal explanatory documents with the hostile disagreements of their two main authors, almost as soon as the Constitution came into action. Perhaps the psychological hangups would be more convincingly dissected by playwrights and poets, than historians.

John Jay wrote five of the essays, mostly concerned with foreign relations; his presence here highlights the historical likelihood that Jay might have been the one who first voiced the idea of replacing the Articles of Confederation. At least, he seems to have been first to carry the idea of a general convention for that purpose to George Washington (in a March 1786 letter). The remaining essays of The Federalist were written under the pen name of Publius by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, both of whom had a strong enough hand in crafting the Constitution, but who quickly became absolutely dominant figures in the two central political factions after the Constitution was actually in operation. And their eagerness to be central is itself telling. They were passing from a stage of pleasing George Washington with his favorite project, into furthering a platform for launching their own emerging agendas. It is true that Madison's Federalist essays were mainly concerned with relations between the several states, while Hamilton concentrated on the powers of the various branches of government. As matters evolved, Hamilton soon displayed a sharper focus on building a powerful nation; Madison scarcely looked beyond the strategies of internal political power except to see clearly that Hamilton was going to get in the way. These two areas are not necessarily incompatible. But it is nevertheless striking that two such relentlessly driven men could work together to achieve the same set of rules for the game they were about to play so unflinchingly. Thomas Jefferson had been in France during the Constitutional Convention. It was he who was most dissatisfied with the resulting concentration of power in the Executive Branch, but Madison eagerly became the most active agent for forming the anti-Federalist party, with all its hints that Washington was too senile to know the difference between a President and a King. Washington abruptly cut him off and never spoke to Madison after the drift of his opinions became undeniable. Today, it is common to slur politicians for pandering to lobbyists and special interests, but that presents only weak competition with the personal forces shaping leadership opinion, chief among them being loyalty to, and perceived disloyalty from, close political associates.

As a curious thing, both Hamilton and Madison were short and elfin, and both relied for influence heavily on their ability to influence the mind of

|

| George Washington |

George Washington, who projected the power and manner of a large formidable athlete. Washington had no strong inclination to run things and, once elected, no particular agenda except to preside in a way that would meet general approval. He had mainly wanted a new form of government so the country could defend itself, and pay its soldiers. Madison was a scholar of political history and a master manipulator of legislative bodies, while Hamilton's role was to supply practically unlimited administrative energy. Washington was good at positioning himself as the decider of everything important; somehow, everybody needed his approval. On the other hand, both Madison and Hamilton were immensely ambitious and needed Washington's approval. This system of puppy dogs bringing the Master a bone worked for a long while, and then it stopped working. Washington was very displeased.

The difference between these two short men immediately appeared in the way they chose a role to play. Madison the Virginian chose to dominate the legislative process as the leader of the largest state delegation within the

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

House of Representatives, in those days the dominant legislative chamber. Hamilton sought to be Secretary of the Treasury, in those days the largest and most powerful department of the executive branch. It's now a familiar pattern: one wanted to form policy through dominating the board of directors, while the manager wanted to run things his way, even if that led in a different direction. Both of them knew they were setting the pattern for the future, and each of them pushed his ideas as far as they would go. Essentially, this could go on until Washington roused himself.

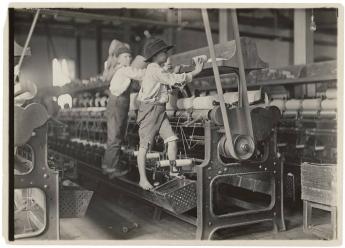

After a short time in office, Hamilton wrote four historic papers about two general goals: a modern financial system, and a modern economy. For the first goal, he wanted a dominant national currency with mint to produce it and a bank to control it. Second, he also wanted the country to switch from an agricultural base to a manufacturing one. You could even say he really wanted only one thing, a national switch to manufacturing, with the necessary financial apparatus to support it. Essentially, Hamilton was the first influential American to recognize the power of the Industrial Revolution which began in England at much the same time as the American Revolution. Hamilton was swept up in dreams of its potential for America, and while puzzled -- as we continue to be today -- about some of its sources, became convinced that the secrets lay in the economic theories of

|

| David Hume |

David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, and of Necker in France. Impetuous Hamilton saw that Time was the essence of opportunity; we quickly needed to gather the war debts of the various states into the national treasury, we quickly needed a bank to hold them, and a mint to make more money quickly as liquidity was needed. It seemed childishly obvious to an impatient Hamilton that manufacturing had a larger profit margin than agricultural products did; it was obvious, absolutely obvious, that this approach would inspire huge wealth for the new nation.

|

| Industrial Revolution |

Well, to someone like Madison who was incredulous that any gentleman would think manufacturing was a respectable way of life, what was truly obvious was that Hamilton must be grabbing control of the nation's money to put it all under his own control. He must want to be king; we had just got rid of kings. Furthermore, Hamilton was all over the place with schemes and deals; you can't trust such a person. In fact, it takes a schemer to know another schemer at sight, even when the nature of the scheme was unclear. Madison and Jefferson couldn't understand how anyone could look at the vast expanses of the open continent stretching to the Pacific without recognizing in this must lie the nation's true destiny. Why would you fiddle with pots and pans when with the same effort and daring you could rule a plantation and watch it bloom? If anyone had used modern business jargon like "Win, win strategy", the Virginian might well have snorted back, "When you say that to me, friend, smile."

Our Federal Reserve (1)

|

| Colonial Coins |

The most enduring, and bitter, controversy in American politics concerns the control of the currency. That's not unusual, since as far back as 1000 B.C. the person or group who controls any government of any country has met resistance in raising taxes, and so was tempted to coin more money. Unless you personally received a big chunk of that new coinage, you were opposed to the system, because of the inflation it invariably created. Prices go up.

So people get upset with watered currency, and once refused to consider something to be real money unless it was made of gold. Gold doesn't rust, there's only a limited amount on the planet, and everybody agrees it's pretty. Silver was maybe all right, too. Gold dust was weighed in the marketplace, but if you trusted the dust you took a risk it had been diluted with something. So coins evolved, with a picture of the king stamped on them, and the edge of the coin serrated, so cheaters would be unable to shave the coin and use the shavings. It didn't matter who stamped the coin, and throughout Colonial times in America, the Spanish piece o'weight was good as gold. But the use of gold and silver coins was cumbersome, and occasionally there were local shortages. One of the important causes of resentment leading to the American Revolution was local discontent with the way the British allowed disruptive shortages of coinage to interfere with commerce in the colonies, at the same time the British prohibited paper currency as too easy to counterfeit. Without a common medium of exchange, commerce is driven to resort to the inefficiencies of barter.

|

| Industrial Revolution |

So, barbarous relic or not, gold was quite effective in restraining governments from their irresistible tendency to promote inflation. The downside began to appear when the Industrial Revolution caused a great increase in a trade because a fixed amount of money in circulation will force all prices lower in a rapidly growing economy. Nobody will buy anything if everything is certain to be worthless if you wait. If people are reluctant to buy, prosperity soon comes to an end. Merchants don't like lower prices, and debtors don't like to repay their debts with money that's scarcer. People are just as unhappy as they were during inflation. Eventually, everybody came to see the best thing was price stability, neither rising nor falling. To accomplish that, the amount of money in circulation has to match the growth of the economy, technically a very difficult balancing act for the government. With the British treasury separated from the colonies by 3000 miles of ocean, and sailboats were used to communicate the distance, the whole thing became impossible.

|

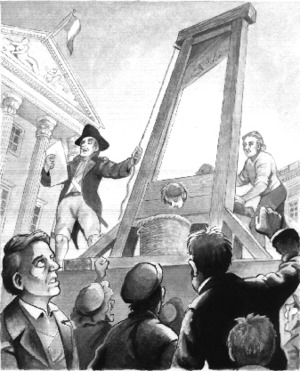

| French Revolution Guillotine |

It's sort of true that an unstable currency puts rich people and poor people into contention. But the more fundamental fact is that it puts creditors and debtors in conflict, thereby paralyzing commerce and injuring everybody else. For three centuries, our political rhetoric has enlisted the support of "workers" against the "the rich", but that's only acceptable shorthand if the balance of currency has gone too far in one direction or the other, and needs to be corrected. If you really let those slogans polarize society, you won't get fairness, you will get another French Revolution and the guillotine. What's needed is to fine-tune temporary imbalances, so the amount of currency in circulation grows gradually in parallel with the economy. During nearly three centuries of struggling with this mysterious issue, we have frequently lost our way with attempts to have "free silver", with honoring or dishonoring the Continental currency, with issuing Greenbacks during the Civil War, War Bonds during various wars, deliberate national deficits during recessions, going off the gold standard, and a host of other expedients and desperate political gestures. The first person to devise a workable system of matching the money in circulation with the size of the economy, was Nicholas Biddle, of 715 Spruce Street.

Our Federal Reserve : Biddle's Bank (2)

|

| Nicholas Biddle |

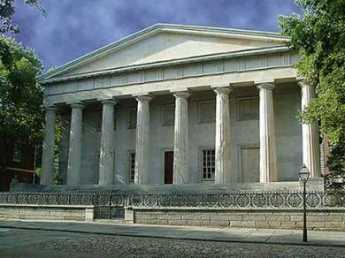

In 1823, the Biddles were prosperous, having made money in real estate (a Biddle ancestor had been a member of the Proprietors), and influential, having been Free Quakers who sided with the Revolution. So, Nicholas Biddle became the president of the Second Bank at 4th and Chestnut. Like all banks, he was given the ability to create money by taking deposits and loaning them out. Since in this process, two people (the depositor and the borrower) think they have the same money, there is effectively twice as much of it -- unless both actually demand it at the same time. If a bank has Federal revenues on deposit, as Biddle did, it is fairly easy for a politically active banker to predict whether that large depositor is likely to withdraw it. Political deposits seemingly make a bank stronger and safer, unless the banker has a fight with a politician. That's banking, but Biddle also became a central banker.

Biddle had ideas, derived in part from Alexander Hamilton. In those days, banks issued their own paper currency, or bank notes, representing the gold in their vaults or the real estate on which they held mortgages. There was a risk in one bank accepting bank notes from another bank that might go bust before you changed their notes into gold. The further away the issuing bank was, the riskier it was to rely on it. So, it was important to be a friendly sort of banker, who knew a lot of other bankers who would accept your money or who were known to be trustworthy.

Nicholas Biddle himself was well known to be pretty rich, and utterly trustworthy. He had a good instinct for how much to charge or discount the banknotes from other banks, or even other states. It was quite profitable to do this, but it became even more profitable when people began to use Biddle's own bank notes because they were safe. By setting a fair standard, he could control the exchange rate -- and hence the lending limits -- of banks that dealt with him. Sometimes a distant bank would get into cash shortages, and Biddle would help them out; if the other bank had a bad reputation, he might not.

|

| Bank of the United States |

In this way, the Second Bank was a reserve bank for other banks, with its banknote currency coming close to being the currency for the whole country. Soon, within a few blocks of Biddle's Bank, there were dozens of other banks, making up the financial capital of the country. Although it was a little obscure, and even Biddle may not have completely realized what he was doing, in effect his system automatically adjust the amount of currency in circulation to the size of the economy. If the correspondent banks prospered, they issued more currency, and if there was a recession, the country had deflation. The volatility of this system was related to the volatility of a pioneer economy, so Biddle made lots of enemies whenever he guessed about the direction of the economy. It wasn't a perfect system, but at least he kept politicians from inflating the currency to get re-elected, and hence annoyed politicians by constraining them. During the great western land rush of those days, all banks were under pressure to issue more loans than was wise, and politicians were under pressure to make them do so.

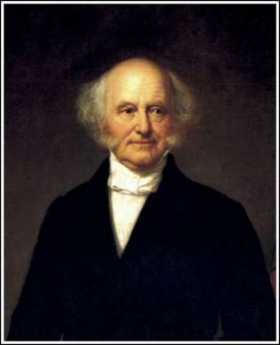

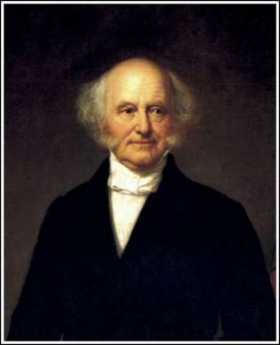

The worst enemy Biddle made was Martin Van Buren of New York. Van Buren was a consummate politician, one of whose many goals was to move the financial capital of the country from Chestnut Street--to Wall Street.

REFERENCES

| America's First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder after the Panic of 1837 Alasdarir Roberts ISBN-13: 978-0801450334 | Amazon |

Our Federal Reserve: Okayed (3)

|

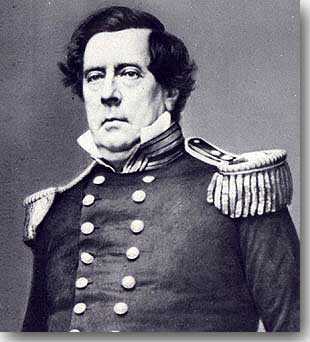

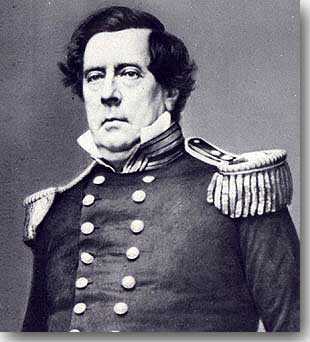

| Martin van Buren |

The 8th President of the United States, Martin van Buren, was born in Kinderhook, New York along the Hudson. He was known as "Old Kinderhook", so in time he initialed his documents "OK", and that's how that slang term originated. It's also of note that his retirement home in Kinderhook was named Lindenwald, although any connection with the terminus of the PATCO high-speed line is unclear. His real claim to fame is that he sort of invented what we know as the a modern political system, particularly that unfortunate doctrine known as the "spoils system". The full allusion is "to the victor belongs the spoils". The two-party a system, the Democratic Party, spinning, log-rolling, and other clever manipulations were of his devising. He must have been pretty shrewd, having defeated De Witt Clinton for Governor of New York, when Clinton was known as one of the most ruthlessly ambitious politicians around. Recognizing he was unlikely to be elected President, van Buren took on Andrew Jackson the war hero and manipulated him into the presidency, with the clear understanding that when Jackson stepped down, van Buren would have the job, next. Van Buren was a cabinet officer during Jackson's first term and Vice President during the second term. During that time, he was the real power running things from the shadows. He ruined the careers of John Calhoun and Henry Clay, regularly taking both sides of a number of disputes over the extension of slavery into new Western territories. What people ultimately thought of all this may be judged from the fact that he ran unsuccessfully for re-election -- three times.

It is therefore not certain just whose ideas were in operation when Jackson blocked the re-chartering of Biddle's bank, but one main benefit, "cui bono?", went to New York. Wall Street had sold stocks under a Buttonwood tree for fifty years, but its real start in the the financial world can be traced from Jackson's action.

The Industrial Revolution and the expansions of the United States by the Louisiana Purchase, the annexation of Texas and the Mexican acquisition caused an an explosion of new wealth, and hence an urgent need to make some better financial alignment of three asset classes: land, precious metals, and currency. Everywhere and at all times it is arguably what the land is really worth; 19th Century America it was particularly speculative, because there was so much of it. Most of the many bank waves of panic during that century can be traced to excessive borrowing to speculate in raw land. When Jackson closed Biddle's reserve bank, the land the speculating public was ecstatic because of any constraints on the lending power of banks made it harder to sell real estate. But what had been done was to eliminate the only reasonably effective way of matching the a true wealth of the country with its circulating monetary assets, and after a brief boom, the almost certain consequence was going to be a national bank panic. It came in 1837, during the first year of Martin van Buren Presidency.

The only imaginable alternative to a market-based monetary system is a government-based one. Van Buren's political behavior was by almost by itself sufficient warning of the danger of allowing politics into this matter. For nearly a century, one warning was enough.

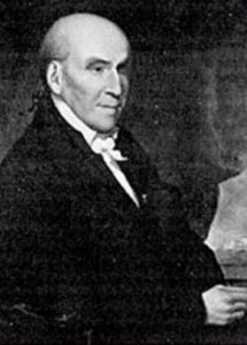

Stephen Girard, Compulsive Gambler

|

| Stephen Girard |

Keep flipping a coin, it's unlikely to come up Heads eighteen times in a row, but it could happen. Once they get to be the richest in the country, most people would quit flipping rather than risk everything on the fifty-fifty chance the next flip will come up Tails. But Robert Morris, William Bingham, Alexander Hamilton, and many others would not only reach the pinnacles of wealth but still gamble everything they owned on a bold chance to get lots more. Stephen Girard was the same way, although in his case he never seemed to lose.

|

| First Bank |

By 1811, Girard was the wealthiest man in America. Among other things, he was the largest stockholder of the First Bank, and ran the largest shipping and merchantile empire in Philadelphia, trading extensively with France and England. From these contacts, he was able to see relationships between France and England, and between England and America, we're going to deteriorate into war. So, Girard cashed out, totally selling his overseas trading interests rather than risk blockades and confiscations. It was a shrewd move, boldly getting out before others could see what he saw. Girard was 61, his wife was permanently hospitalized, and he certainly never had to work again.

As a major stockholder in the bank, Steven Girard was well aware of the strong populist sentiment that the Government had no business running a bank. Although he did his best to preserve the bank, he could see its closure was politically inevitable with Thomas Jefferson as President of the United States, soon to be followed by his Virginia crony, James Madison. When the charter was revoked, Girard took his immense cash horde -- and bought the doomed bank with it. From the Virginians' perspective, they were going to need that money if they went to war with England; while in Girard's view they could not possibly fight a war without a bank to finance it. As matters turned out, the War of 1812 was largely financed by Girard's personal wealth, which ultimately meant that Girard bought the Government's bank with the Government's own money.

|

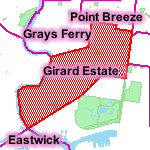

| Girard Estate Map |

Even making allowances for the fact that the troubles over the national banks were a symptom of the immature financial markets of the nation, which made passive investment difficult for those with rentier ambitions, Girard was clearly a compulsive gambler. Most compulsive gamblers are losers, Girard just happened to be a compulsive winner. His new bank was enormously successful, and as late as 1829 he purchased all of Schuylkill County for its coal discoveries, expressly directing in his will that his heirs were never to sell it. His estate still owns a large part of South Philadelphia, based on the same long foresight of a pretty old man. If you think that's easy to do, just ponder what finally happened to Robert Morris, Haym Salomon, and Alexander Hamilton.

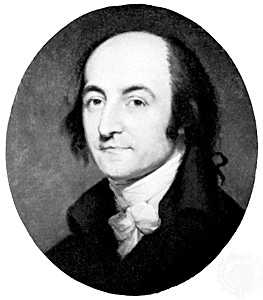

Albert Gallatin: Enigma Furioso

|

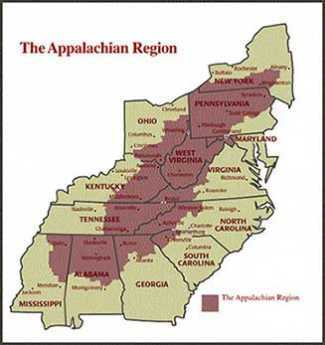

| Appalachia |

Abraham Alphonse Albert Gallatin was born to a rich, famous and noble family in the French part of Switzerland in 1761, but soon became a rich orphan fleeing to America in the 1780s to escape overbearing and grasping relatives. He started out in America teaching French at Harvard but soon purchased Friendship Hill, a 600-acre estate south of Pittsburgh along what was to become the National Road. At first, he ran a busy general store but soon branched out into successfully buying and selling real estate. Although Uniontown now seems a lonesome hermitage in Appalachia, it was then part of the area disputed between Pennsylvania and Virginia, coveted by both states because it seemed like the main route to Ohio when Ohio was the Golden Frontier. Friendship Hill is now a National Park, near Fort Necessity, also near General Braddock's grave, and the birthplace of George Catlett Marshall. So it had its attractions, but Gallatin led such a frenzied life it is hard to believe he spent much time there. There is a reason to believe he was one of the main instigators of the Whiskey Rebellion. Hamilton, and probably Washington, certainly thought so.

|

| Albert Gallatin |

Almost immediately after arrival in America, Gallatin threw in his lot with Thomas Jefferson in resistance to the centralizing, Federalist, qualities of the new Constitution. Both of them were looking for more liberty than the Constitution offered. The movement they led became the anti-Federalist party and would have been the anti-constitution party except for reluctance to oppose the towering figure of George Washington. Gallatin's French loyalties seem to have overcome his aristocratic family background in supporting what enemies of the French Revolution had called Jacobin (or "Republican") notions. His Swiss background additionally gave him great credibility in high finance in backwoods America. In spite of being rather out of place among Virginia Cavaliers, his personal qualities seem to have made him a natural politician. He hated Hamilton's idea of the National Bank, arguing against it effectively in the unsophisticated company. The issue was not so much opposition to banking, but to government dominance in central banking. He was certainly right that mixing the two created a constant risk of inflation from yielding to political demands, an empirical observation almost without any exception for 800 years. However, it was too early in the history of central banking to perceive that it was debtor pressure which promotes inflation. Governments are almost invariably debtors themselves, whereas the elites he was attacking, in general, become creditors, resisting inflation. Inflation is merely a variant of defaulting on debts, which debtor governments happen to have at their disposal because they control the currency.

At this early stage of central banking, America was largely using its vast amounts of land as a substitute for money, but quickly adapted to Hamilton's new monetary system which was far more flexible. Gallatin later played a role in the chartering of both the Second and the Third Banks, although his motives here were somewhat different. (Government caps on interest rates induced the Banks to lend to only the best risks, which amounted to favoring Philadelphia over the frontier, Gallatin's main constituency.) He was appointed U.S. Senator for Pennsylvania at the age of 32 but was evicted on a straight party vote on the ground that he had not been an American citizen for the required nine years. It seems likely that accusation was correct. He was soon elected a Congressman, becoming Chairman of Finance (later called Ways and Means), the majority leader after five years. In retrospect, while it seems perplexing that a sophisticated financier would oppose a central bank, his opposition may have been mainly against having politicians operate one, a rather unavoidable consequence of government control. Hamilton's idea that deliberately going into debt was a way to establish "creditworthiness" was denounced as particularly offensive by those who disdained indebtedness as the most dangerous sin of commercial life. The anti-Federalists were clearly wrong on this point, but it is possible to sympathize with their suspicions. Even today, the unwillingness of banks to lend money to someone who has no history of the previous borrowing is one of those things which seem so natural to bankers, and so irritating to apostles of thrift.

It remains unclear to history whether Gallatin had really never believed what he was saying, or had gradually changed his mind as he gained experience. He did confess or perhaps suddenly realize his error as the War of 1812 approached and he was Secretary of the Treasury. In this awkward event, he found himself charged with organizing the finance of a war with no way to do it. What was worse, Jefferson relentlessly pursued the closure of the National Bank for ideological, even fanatical, reasons; and Jefferson was the boss. The resolution of this conflict was to enrich Stephen Girard even further, while forcing Gallatin to a humiliating public reversal of stance. Nevertheless, America simply had to have a bank to fight a war. It is greatly to Gallatin's credit that his frenzied and obviously sincere entreaties to the bewildered Jefferson and Madison then saved the Nation from a disaster of foolish consistency. In a larger sense, the dramatic reversal of stance also played a role in shifting American sympathies from France to England. American sympathies were then wavering. On one side, there was gratitude to the French for bankrupting themselves with unwisely large loans to our struggling revolution, and for allying themselves with that revolution, soon imitating it with a revolution of their own against the common slogan, oppressive monarchy. True, there was more than a little hankering for the annexation of large chunks of Canada. That was one side of it, which Lafayette, Girard, Gallatin, and Jefferson labored to enhance, probably with their eye on French Quebec. On the other hand, there was that appalling genocide of the Jacobin guillotine, which Napoleon soon threatened to extend to all European monarchies within his reach. The Seven Years War, which we called the War of the French and the Indians, had left memories in America that French ambition could extend from Quebec to Louisiana and include Haiti. The French once even occupied Pittsburgh, and their Indian allies had scalped settlers in Lancaster. That was not so long ago. Furthermore, the English invention of the Industrial Revolution was immensely attractive to artisan Americans. Ultimately, we made our choice for steady prosperous commerce of the British sort, rather than glittering glorious conquest, of the French style. By 1813, Gallatin had served longer as Secretary of Treasury than anyone before or since, and earlier had a more distinguished career as both Congressman and Senator than all but a few have ever achieved. When he was offered the position as a commissioner to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812, it was natural to expect that it would be the final act of his long political career. It was, however, only the beginning of a ten-year diplomatic career as Ambassador, first to France and then to England. Following that with still another new career, he took up academic work, returning to America to found New York University, personally establishing the academic discipline of study in Indian Affairs and language, and founding the American Ethnological Society. Gallatin wrote two books about Indian language patterns and first suggested that the similarities between the languages of North and South American Indians probably meant they were related tribes. In another sphere, Gallatin is credited with originating the American doctrine of manifest destiny.

While skipping from one distinguished career to several others, Gallatin never forgot he was a banker. He wrote the charter for the Second National Bank ("Biddle's Bank"), plus the Third Bank of Pennsylvania, and founded the National Bank of New York, which was named Gallatin's Bank for a while, before gradually evolving into what is now called J.P. Morgan Chase Bank. As a diplomat, he negotiated many boundary disputes, including Oregon, Maine, and Texas. He bitterly opposed the annexation of Texas.

When it comes to writing about Gallatin, there is so much to say it is hard to say anything coherent. He was such a virtuoso of public life that he defeats his biographers in their central task, of telling the world what he was like. There haven't been many if indeed there were any, enough like him to offer a comparison. And yet history has not been kind to him. He can comfortably claim the title of the most famous American, that no one since has ever heard of.

Gallatin, Part 1

|

| Albert Gallatin |

William Shakespeare died two centuries before the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, but he left us a clear outline of his style. Tragedies end with everyone getting killed, comedies end with everyone getting married, but histories have no clear beginning or end. The Hollingshead chronicle underlying this particular effort is the excellent history by Robert E. Wright and David J. Cowen, called Financial Founding Fathers. The story of the young Swiss aristocrat Albert Gallatin, plonked into the backwoods of Pennsylvania only to be relentlessly pursued by his arch enemy General Alexander Hamilton, ends in 1804 when Hamilton is killed in a duel by the Vice President of the United States, Aaron Burr.

Act 1. Ex-Senator Gallatin.

Aged 33, Gallatin was young to be a U.S. Senator, but his Swiss background in finance made him one of only five or six Americans who knew anything about banks. Unfortunately, his passionate Swiss frugality immediately made him the arch enemy of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton who wanted to combine state debts from the Revolutionary War into a national debt. This thorn in Hamilton's side was removed by evicting Gallatin from the Senate on the grounds that he had not been a citizen for the ten years required by the Constitution. Unfortunately, that was true. It was nevertheless galling that Robert Morris, the other Pennsylvania Senator, would vote against him. The humiliation of being forced to leave Philadelphia and ride horseback to his home in Fayette County, right on the Indian frontier among the semi-barbarian Scotch Irish, was extreme.

Act 2. Caught in the Middle.

When Gallatin arrived home in the backwoods, the incensed local farmers instantly rallied around him as the perfect leader of a rebellion they wanted to start. A four-year war with the Indians in nearby Ohio had shut off all hope of marketing their grain to the West, and the Allegheny Mountains made it unprofitable to ship it to the East. Their response was to distill it into whiskey, which would not spoil with storage, and was more compact to transport. Assisted in part by Quakers' horror at selling whiskey to the Indians, Hamilton had pushed through a tax on whiskey which rendered it impractical to make it at all. Gallatin was already Hamilton's enemy, and Gallatin the European knew how to talk to those swells in the East. Gallatin did make rousing speeches about injustice but always cautioned the wild men to behave peacefully. That wasn't exactly what the angry farmers wanted, so Gallatin soon became the enemy of both sides of the dispute when the western Pennsylvanians organized a rebellion. Both sides made threats to assassinate him.

Act 3. The Lion Roars

President George Washington didn't know much about banks or taxes, but he knew a lot about law and order, and he wasn't having any rebellions. Ordering up an army of fifteen thousand men, he and General Hamilton led it across the state of Pennsylvania to hang 'em. Meanwhile, however, General "Mad" Anthony Wayne had defeated the Indians along the Miami River in Ohio, thus removing the main reason for whiskey manufacture, and finally proving to the anti-Constitution Jeffersonians that the federal government really was a useful thing to have. Washington dropped out at Bedford and went back to running the country, allowing the relentless Hamilton to charge forward to Pittsburgh. By that time, the farmers had pretty well dispersed, but to Hamilton they were traitors and that particularly included Gallatin.

Act 4. Local Hero

Two ringleaders were convicted of treason, everyone was threatened and interrogated. Hamilton was particularly anxious to include Gallatin in the net, but no one in that frontier culture would accuse Gallatin of participating in the call to violence or testify to any treasonous speech by him. In the midst of the uproar, Washington rose to the occasion and pardoned them all. Every last one of them.

Act 5. Secretary Gallatin

In a surge of jubilation, western Pennsylvania elected Gallatin as their congressman, sending him back to Philadelphia where he could do them some good. And indeed he quickly assaulted all of Hamilton's policies, both good and bad, as well as just about every other Federalist program. He quickly rose to the effective leadership of Congress and swung the crucial 1800 election from Aaron Burr to Thomas Jefferson. Since Jefferson was another Virginia Cavalier who knew nothing about finance, it was a foregone conclusion that President Jefferson would appoint Gallatin to be Secretary of the Treasury. Finally, in 1804 Burr removed Hamilton from public affairs on the flats of Weehawken. At the news of the death of his enemy, Gallatin shed not a tear. His memorial was the statement that "a majority of both parties seemed disposed.....to deify Hamilton and to treat Burr as a murderer. The duel, for a duel, was certainly fair."

Gallatin Part II

Act 1 Gallatin Triumphantly Returns to Congress.

When Washington pardoned the Whiskey Rebels, Gallatin was immediately elected to Congress. It was his payback time for Hamilton and all his works. The desperate Federalists tried to oust him a second time with a Constitutional Amendment, which failed before the force of Gallatin's oratory. Gallatin then threw his influence behind Jefferson's deadlocked congressional contest with Aaron Burr, electing Jefferson and earning his own reward as Secretary of the Treasury. Although elected Vice President, Burr's fury is turned against Hamilton, foreshadowing the coming duel.

Act 2 The Virtuoso Financier.

Jefferson proves hopeless in domestic affairs, so Gallatin essentially takes over that role, just as Hamilton had taken over from Washington, who was another Virginia cavalier adrift in these matters. Gallatin promptly repealed the whiskey tax, cut government expenses, in particular, the million dollars annual tribute to the Barbary pirates, and almost performed magic in financing the Louisiana Purchase together with Stephen Girard and William Bingham.

Act 3 Burr Kills Hamilton

After his Vice President kills the leader of the opposition party, Jefferson's party was on the political defensive. But not Gallatin, who spits out his famous remark, "A majority of both parties seem disposed to deify Hamilton and treat Burr as a murderer. The duel, for a duel, was certainly fair." It is an all-time low moment in the politics of the young nation.

Act 4 Diplomacy or War?

As the Napoleonic wars engulf the whole world, both England and France harass our merchant ships, and cries go up for war. Partly out of a desire to annex Canada in the process, Gallatin sneers at proposals to restrain the fighting Europeans with mere sanctions. His prediction proves dismayingly correct that nothing would come of it except to make our own citizens into smugglers.

Act 5 War It Is.

The First Bank's charter was to expire in 1811, and the bank closed, creating an opportunity for Girard to buy it out and finance the coming war himself. Gallatin was desperate to end the war as quickly as possible, especially after the British burned Washington. To speed matters up, Gallatin took a leave of absence and went off to the peace conference in St. Petersburg himself.

Epilogue in front of the curtain.

Gallatin finally announces his resignation from the longest term of Treasury Secretary in our history. He is seventy years old, three scores and ten. Rather than play golf, he was to spend the last eighteen years of his life in three more careers. As a diplomat, he negotiated both our permanent northern and southern borders. As an academic, he founded the discipline of ethnology with the study of native Indian languages, meanwhile founding New York University. And as a banker, he founded a bank which has since evolved into JPMorgan Chase. After all, a man has to find something to keep himself busy.

Laundered Money

|

| Judge Edwin O. Lewis |

Judge Edwin O. Lewis finally got his way, the Pennsylvania State Government acquired four blocks of Chestnut Street stretching to the East of Independence Hall, and the Federal Government acquired four blocks stretching to the North. Judge Lewis was determined that a real revival of historic Philadelphia required the clearance of a lot of lands. Those who heard him describe it will remember the emphasis, "It must be BIG if it is to serve its purpose."

The open land is rapidly filling in but for a time the movers and shaker of this town had to scratch a little to find something to put there. That's fundamentally why the historic district has a Mint, a Federal Reserve, a Court Houses, a Jail, and a big Federal Building to house various local offices of the landlord, the federal government. It's where you go to visit your congressman, or to renew your passport, or to argue with the Internal Revenue Service. If you have certain kinds of business, there's an office for the FBI and the U.S. Secret Service. The mission of the Secret Service is a little hard to explain with logic.

The Secret Service is a federal police organization, charged with protecting the President of the United States, and enforcing the laws against counterfeiting money. In unguarded moments, the Secret Service officers will tell you they only have one function: to guard three-dollar bills. The President only comes to town from time to time, but the mandate extends to the President's family, and to the extended family of official candidates for election to that office. So, there is usually always a certain amount of activity relating to running behind limousines with one hand on the fender, or poking around rooftops near the speaker's platform at Independence Hall, or talking apparently to a blank wall, using the microphones hidden in their ear canals. The rest of the time is taken up with counterfeiters, but even then the excitement is only occasional, depending on business.

A few years ago, the buzz around the office was that some very good, even exceptionally good, fake hundred dollar bills were in circulation in our neighborhood. The official stance of The Service is that all counterfeits are of very poor quality, easily detected and no threat to the conduct of trade. Unfortunately, some counterfeits are of very good quality, not easily detected, and when that happens, The Service is made to feel a strong sense of urgency by its employers. These particular hundred dollar fakes were of very good quality.

One evening, a call came in. Don't ask me who I am, don't ask me why I am calling. But I can tell you that a very large bag of hundred dollar wallpaper has just been tossed over the side of the Burlington Bristol Bridge, near the Southside on the Jersey end. Goodbye.

Very soon indeed, boats, divers, searchlights, ropes, and hooks discovered that it was true. A pillowcase stuffed with hundred dollar wallpaper of the highest quality was pulled out of the river. By the time the swag was located and spread out for inspection, it was clear that several million dollars were represented, but they were soaked through and through. Most of the jubilant crew were sent home at midnight, and two officers were detailed to count the money and turn it in by 7 AM. The strict rule about these things is that all of the money confiscated in a "raid" was to be counted to the last penny before it could be turned over to the day shift and the last officers could go home to bed. After an hour or so, it was clear that counting millions of dollars of soggy wet sticky paper was just not possible by the deadline. So, partly exhilarated by the successful treasure hunt, and partly exhausted by lack of sleep, the counters began to struggle with their problem. One of them had the idea: there was an all-night laundromat in Pennsauken. Why not put the bills in the automatic drier, so they could be more easily handled and counted? Away we go.

|

| Burlington Bristol Bridge |

At four in the morning, there aren't very many people in a public laundromat, but there was one. A little old lady was doing her wash in the first machine by the door. It was a long narrow place, and the two officers took their bag of soggy paper past the old lady, and down to the very last drying machine on the end. Stuffed the bills into the machine, slammed the door, and turned it on. Most people don't know what happens when you put counterfeit money in a drier, but what happens is they swell up and sort of explode with a terribly loud noise. The machine becomes unbalanced, and the vibration makes even more noise. The little old lady came to the back of the laundromat to see what was going on.

As soon as she got close, she could see hundred dollar bills plastered against the window, and that was all she stopped to see. She headed for the pay telephone near the front of the door. The secret Servicemen followed quickly with waving of hands and earnest explanations, but within minutes there were sirens and flashing lights on the roof of the Pennsauken Police car. Out came wallets and badges, everyone shouting at once, and then everything calmed down as the bewildered local cop was made to understand the huge social distance between a municipal night patrolman and Officers of the U.S. Secret Service. Now, he quickly became a participant in the great adventure and was delegated the job of finding something to do with armloads of (newly dried) counterfeit hundred dollar bills. He had an idea: the local supermarket was also open all night, and they carried plastic garbage bags for sale. Just the thing. But who was going to pay the supermarket for the bags? Immediately, everyone was thinking the same thing.

Fortunately for law and order, the one who first suggested the the obvious idea of passing one the counterfeits was the little old lady. At that, everyone came to his senses. Wouldn't do at all, quite unthinkable. The local cop was sent off for the bags, relying on his ability to persuade the supermarket clerk. And, yes, they did get the money all counted by 7 A.M.

Making Money (1)

|

| Barbarous Relic |

As 2005 turns into 2006, we watch an upward surge in the price of gold for the first time in three decades. The last time the gold price soared, America had gone off the gold standard completely, ending traditional promises that U.S. dollars could always be exchanged for precious metals at a specific price. A brief flutter of the exchange rate ("the price of gold") under floating-price circumstances was to be expected since it was even conceivable that the price of gold might eventually go down. It didn't, and when things settled out it was roughly true that the price had migrated from about thirty dollars for an ounce of gold to about three hundred dollars an ounce. The conversion price has experienced fluctuations since that time, gradually moving to four hundred dollars an ounce in thirty years. There was a reason to see this as a one-time readjustment. The floating prices of precious metals might drift along independently forever, responding to fashions in gold jewelry and advances in dentistry, but a matter of little interest to anything else. No doubt there would be panics in third-world politics, but anyone one who staked life's savings on predictions of wars and famines in the underdeveloped world was imprudent a nut. A gold bug.

This time, it seems to be different; all is calm. The price of gold now exceeds five hundred dollars an ounce; responsible publications even conjecture it will go to a thousand within five years, perhaps three thousand in fifteen years. You might say wild predictions are thus flying about that our savings will lose ninety percent of their value, but nowadays nobody seems willing to say this is either a crisis or just nutty talk. There is both an absence of alarm that the price of gold is predicting disaster, but also a lack of scorn for dumbbells who would actually believe such a thing. A cynic would say that the columnists in financial magazines all seem to be owners of some gold and are talking up its price. But we were told it didn't matter, so we seem to believe it.

A more reflective view would be that we are experiencing the first real test of the world's new monetary system, at least its first challenge by the marketplace since the convertible link between gold and dollars was officially severed. The value of gold seemingly has little to do with its basic utility for dentists. The value of the dollar seemingly does not attempt to relate to the actual supply in circulation, nor attempt to represent a share of all American assets; those things are too hard to measure. The number of dollars in circulation is governed by watching inflation and unemployment and having the Federal Reserve create more or fewer dollars as needed to keep inflation and unemployment at some steady, pre-determined level. The price of gold is something else, irrelevant to a civilized society. It's all terribly clever, but it ultimately depends on whether those pre-determined levels of inflation or unemployment are well chosen. And whether politicians might tinker with them.

It would, therefore, seem likely that the clearing price between gold and dollars is currently putting a high value on gold for reasons other than a current over-supply of dollars or a world shortage of the metal. We must look elsewhere for the cause of the gold-price panic. The Chinese and the Indians are getting richer; perhaps the value of precious commodities somehow reflects that relativity. Or perhaps we are dealing with political predictions; a civil war in China renewed war between India and Pakistan, a revolution in the Persian Gulf oil kingdoms. Or atomic bomb terrorism directed against the United States. Whatever political upheaval it is that bothers the gold bugs must be pretty big; neither the war in Afghanistan nor the one in Iraq or the combination of both, was enough to stir up gold prices to the present degree.

In a sense, the worst possibility would be: the gold hysteria has no rational basis at all, like the tulip bulb frenzy of several centuries ago. The immediate question gets raised whether a merely intellectualized value for the currency can withstand cataclysmic world events. But if there is no serious threat of world cataclysm, then the remaining question on the poker table becomes whether hysterical financial commentators can topple the dollar system just by mindlessly stampeding. A monetary system which cannot withstand such a trivial threat is not a viable monetary system. The financial world's eggheads would then be in a war with the financial world's green-eyeshade gamblers. It's not entirely safe to predict who will win.

Making Money (2)

|

| counterfeit money |

One of the important provocations of the American Revolutionary War was shortage of cash caused by a primitive currency system. The British government would not permit colonies to print easily counterfeited paper money; while dependence on gold coins regularly caused temporary shortages during seasonal trade imbalances. Colonists became bitter about farm foreclosures when an otherwise prosperous farmer simply couldn't find enough coins to satisfy his mortgage payments. So, from earliest days the monetary system highlighted the important distinction between how much cash you had jingling in your pocket, and how rich you actually were. Electronic banking and funds transfers have now largely eased the cash flow issue; measuring the true wealth of the whole economy still contains much guesswork. When the economy seems to be undervalued (deflated) by the prices collectively set by the marketplace on each of its parts, two common fiscal remedies still provoke political controversy. To inflate the economy, the government can spend money, or it can reduce taxes. The empirical history of the past century seems to show that cutting taxes is quicker and more effective, particularly when taxes were too high, to begin with. It may not work when taxes are insignificant, so the political debate between the two parties who have adopted these programs as pets tends to center on whether taxes are too high or too low and who is paying them.

To a certain extent, this is a tempest in a teapot. Both reducing federal taxes and increasing federal spending lead to increasing federal deficits, which are then covered by issuing federal bonds. Not much difference, there. The important difference on a practical level is that cutting taxes increases money in circulation more quickly than wrangling about what programs might be best, and then painfully organizing them. The choices for spending opportunities are set by the private sector when taxes are reduced, are therefore more effective in stimulating the private economy, less likely to be politically filtered than legislative authorizations are. The fresh funds from cutting taxes go to those who were successful enough to be paying taxes. They personally need them less than poor people do, but they have a better track record in multiplying them. Unless taxes are already too low to make a difference, reducing taxes is clearly quicker and more efficient than authorizing government spending. Finally, the argument about "planning" introduces an unnecessary sour note. Although the Communist Party was famous for five-year plans and the like, the truth is their system of subordinating economic goals to political ones was the main source of their economic collapse. It was a German, Italian and Japanese systems of central planning which can fairly claim a measure of economic success, growing out of their admiration for an earlier era of success by huge industrial corporations, stimulating even in America a spirit of "win the war" top-down organization. We thus have the ironic situation where it is awkward to point out the technical reasons for the post-war failures of the centrally planned Axis nations since the people who now seem most attracted to central planning are the ones most likely to be offended by the comparison. Somehow, we must hope that the French and Chinese learn this lesson by themselves.

Making Money (3)

|

| David Altman |

Daniel Altman draws attention in the January 1, 2006 New York Times to Ben Page's estimation of compensating rises in federal tax revenue after tax cuts. Page (for the Congressional Budget Office) says revenue increases will only offset 28% of tax loss. The Laffer theory (that tax cuts pay for themselves) may be overstated but it's kind of right. Not only is the full amount of the tax reduction immediately released to the private sector, but only 72% of it ever needs to be borrowed and repaid. Tax cuts may not pay for themselves but they fully stimulate the economy immediately; 28% of the stimulus is permanent.

Mr. Altman then comments taxes could never be cut to zero, because lenders would then refuse to lend; surely no one disagrees. But it's extreme to say tax rates must currently be at a point "on the curve" where reducing them further will not generate a worth-while gain in tax revenue to be effectively re-injected back into the economy. All of any tax cut is always a windfall for the private sector; that's its purpose. Ben Page just says that only 72% of this one needs to be borrowed; the other 28% is a permanent cost-free saving for everybody. If you chose to stimulate the economy by increased government spending, all of that would have to be borrowed, all of it would have to be repaid.

But cheers for Mr. Altman, who notices the role of lenders, who place limits on how far you can stretch this idea. You can't cut taxes to zero because lenders won't lend to a government without income. And even as taxes approach zero, lenders will raise interest rates. That gets us to the currently inverted yield curve; why aren't long-term bonds able to command higher interest rates? If they rose, the interest cost would eventually wipe out the free ride for tax cuts.

Well, the big artificiality in this Calder mobile is the fixed exchange rate for Chinese currency. The Chinese are inexperienced, rightly fearing chaos if they allow their currency to float upward against the dollar. When they solve their problem, unless God helps us they bungle it, American bond rates will tell us whether it's safe to cut taxes some more. Interest rates on American long-term bonds will rise, perhaps too uncomfortably high levels. At that point, no government -- R or D -- would cut taxes further.

Making Money (4)

If lowering taxes is inflationary, how can it be that several financial columnists refer to buying low priced

|

| China Man |

Chinese imports as "importing deflation"? It would seem, in both cases, that consumers end up with more money in their pockets, so both cases must be inflationary. To answer that twister, you also need to consider where the inflationary new money comes from.

|

| chinese labor |

When the government lowers its revenue by lowering taxes, it creates a deficit which is paid for by issuing bonds. That's inflationary until the bonds are paid off. If the bonds are ever paid off, the amount of money in circulation then returns to its original level. The public has effectively given itself a loan by lowering taxes, so after a temporary spell of inflation, there is no permanent effect on circulating money at all. By contrast, when Chinese workers agree to work for lower wages than Americans, that causes inflation for the American economy because Americans have more spending power left over. How they spend it is their business; the bonanza may surface as a stock market bubble or a real estate bubble, a credit card bubble or a spectacular Christmas shopping season. But gradually the extra money seeps out into the economy as extra wealth of some sort. Whether you describe it as real added wealth or just inflation, maybe a quibble -- but it clearly is not deflation.

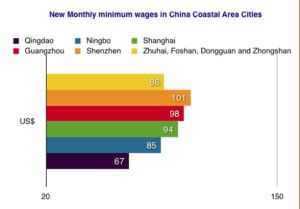

|

| Chinese wages |

But when a successful financier, betting his own money on his analysis, says that America is "importing Chinese deflation", it's likely he says something important, however imprecise technically. In this case, it would seem to be an observation that the globalization method of creating inflation minimizes some of the usual consequences of inflation. Since the low prices of Chinese products are mainly due to low Chinese wages, they discourage wage demands in this country, even in industries which do not compete against imports. That's politically important, even though there are many more consumers than manufacturing workers, and the nation as a whole is better off for the globalization. In short, inflation is not invariably a bad thing.

Now, just think of the problems that create for the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, who is charged with maintaining level prices, and defines our whole currency system on doing whatever it takes -- to avoid inflation.

Making Money (5)

|

| Keynes |

Every newly-rich country seems to experience at least one episode of adolescent giddiness, thinking there is no stopping them, their trees will all grow to the sky. America's comeuppance took place in 1929, Japan's in 1990. Sooner or later the Chinese and the Indians will learn that it is unwise to grow faster than human systems can readjust, overcapacity is certain to appear at some point, and the new bumpkin will then appreciate what it means to have a business cycle. After a variable time, deflation reaches the bottom, and it is past time to inflate back to normal. Lord Keynes (pronounced "Caine's") advised Franklin Roosevelt to promote government spending, even useless spending, but it didn't help as much as they hoped. The Japanese built bridges and tunnels to nowhere, and that didn't help much either, although encouraging residential construction worked better than they expected. Wars are good for deflation, too, but only if you win them.

America has devised three methods for combating deflation: cutting taxes when other nations maintain fixed currencies, cutting consumer prices at the expense of developing countries, and cutting costs by improving productivity. You could combine these three methods into one principle: if you can't increase the amount of money, you must increase virtual spending power by cutting prices. In a deflation, consumer prices have fallen because of overcapacity, so you must cut consumer costs in those areas which will not respond to overcapacity. Same money, more buying power. Other countries are apt to resort to gold as a way of preserving their buying power; it will be an interesting struggle.

Nevertheless, it will be important for America to spend its affluence on increasing productivity rather than trinkets and junkets; we, too, have our share of adolescents. Computers have helped us reduce transactional costs everywhere; transportation is in fair shape. Education is an expensive mess, simply begging for improvement. Housing is still using 19th Century methods. Entertainment is expendable. We have a huge supply of underutilized labor in the black male community, in the early retirees, and in our comfortable work habits. Fighting wars is a pretty expensive hobby. How well we withstand the next world recession will depend to a major degree on how well we solve the problems that obviously need solving.

The business cycle will continue to cycle, but it is possible to feel pretty good about American ingenuity in relating, globalizing and enhancing productivity. There is even a wicked satisfaction in reminding our British cousins of their little witticism which made the rounds after World War II:

In Washington, Lord Halifax

Once whispered across to Lord Keynes:

"It's true that they have big moneybags,

But we have all of the brains."

Making Money (6): The Laffer Curve

|

| Arthur Laffer |

Recall for a moment, the two Republican idols, economists Milton Friedman and Arthur Laffer. Friedman won a Nobel Prize by observing that inflation is "always and everywhere" caused by too much money in circulation. Thus, a potential remedy for inflation was suggested: central banks (i.e. the Federal Reserve) can restrain that by raising short-term interest rates at the first sign of inflation. It certainly seemed to work; by doing so, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan was able to avoid inflation for eighteen years.

Arthur Laffer offered a second idea for Presidents to test. Laffer maintained that if taxes were too high, you would paradoxically collect more taxes by lowering tax rates. The younger George Bush took him up on it, reasoning that if tax collections did rise after tax rates were cut, it would be proof that taxes had been too high all along. The appeal to tax technicians in the Treasury Department was that, by observing tax collections, all changes in tax rates up or down might lead to the identification of the most efficient possible tax rates. So, although President Reagan had felt warm about Laffer, while the senior George Bush rudely dismissed such ideas, George W. was eager to test his gut feeling that tax rates were too high. Each year during his presidency, George W cut taxes. Gratifyingly, each year total tax revenue (adjusted for GDP) increased. Eight years are not the same as eighteen, but it certainly looks as though W proved that taxes had indeed been too high. If some future Congress has the courage to raise taxes, and then tax collections go down, the Bush legacy would seem pretty secure. Two iron laws of national economics would be enshrined: The tax rate should be whatever maximizes tax revenue. Interest rates should be whatever restrains inflation. Live with it.

True, none of this insight casts much light on how to cope with wars and depressions. Raising interest rates seemingly defeats inflation, but lowering interest rates has not always cured recessions. Furthermore, the fiscal and monetary direction of the country may have to be altered when we face war, famine, weather disasters, and demographic shifts. But at least we seem to know how to determine the optimum level of (overnight, interbank) interest rates and taxes, so have a compass for return to those levels after detours around uncertain events. Maybe economists, even Voodoo economists, can suggest some other principles which politicians can test in the real economy. And political science can then start to have some true scientific method in it; propose a theory, test it, revise the theory and test it again.

But there's one more thing that Art Laffer didn't understand when he was drawing his famous curve on the back of a paper napkin. One of the main reasons tax collections rose spectacularly when George Bush finally had the nerve to try lowering taxes -- was that the underground, tax-evading, economy was a great deal larger than anyone had suspected. Laffer made crooks into honest people.

Making Money (7): Fractional Reserve Banking

|

| Money and Credit |