Related Topics

Whither, Federal Reserve? (1) Before Our Crash

The Federal Reserve seems to be a big black box, containing magic. In fact, its high-wire acrobatics must not be allowed to fail. Nevertheless, it may be time to consider revising or replacing it.

Revisionist Themes

In taking a comprehensive view of a city, an author sometimes makes observations which differ from the common view. Usually with special pride, sometimes a little sullen.

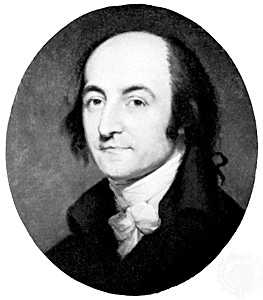

Albert Gallatin

A magnificent but largely forgotten man.

Pacifist Pennsylvania, Invaded Many Times

Pennsylvania was founded as a pacifist utopia, and currently regards itself as protected by vast oceans. But Pennsylvania has been seriously invaded at least six times.

Philadelphia Changes the Nature of Money

Banking changed its fundamentals, on Third Street in Philadelphia, three different times.

Albert Gallatin: Enigma Furioso

|

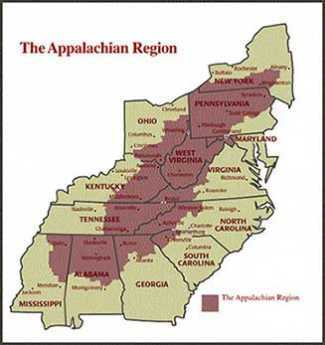

| Appalachia |

Abraham Alphonse Albert Gallatin was born to a rich, famous and noble family in the French part of Switzerland in 1761, but soon became a rich orphan fleeing to America in the 1780s to escape overbearing and grasping relatives. He started out in America teaching French at Harvard but soon purchased Friendship Hill, a 600-acre estate south of Pittsburgh along what was to become the National Road. At first, he ran a busy general store but soon branched out into successfully buying and selling real estate. Although Uniontown now seems a lonesome hermitage in Appalachia, it was then part of the area disputed between Pennsylvania and Virginia, coveted by both states because it seemed like the main route to Ohio when Ohio was the Golden Frontier. Friendship Hill is now a National Park, near Fort Necessity, also near General Braddock's grave, and the birthplace of George Catlett Marshall. So it had its attractions, but Gallatin led such a frenzied life it is hard to believe he spent much time there. There is a reason to believe he was one of the main instigators of the Whiskey Rebellion. Hamilton, and probably Washington, certainly thought so.

|

| Albert Gallatin |

Almost immediately after arrival in America, Gallatin threw in his lot with Thomas Jefferson in resistance to the centralizing, Federalist, qualities of the new Constitution. Both of them were looking for more liberty than the Constitution offered. The movement they led became the anti-Federalist party and would have been the anti-constitution party except for reluctance to oppose the towering figure of George Washington. Gallatin's French loyalties seem to have overcome his aristocratic family background in supporting what enemies of the French Revolution had called Jacobin (or "Republican") notions. His Swiss background additionally gave him great credibility in high finance in backwoods America. In spite of being rather out of place among Virginia Cavaliers, his personal qualities seem to have made him a natural politician. He hated Hamilton's idea of the National Bank, arguing against it effectively in the unsophisticated company. The issue was not so much opposition to banking, but to government dominance in central banking. He was certainly right that mixing the two created a constant risk of inflation from yielding to political demands, an empirical observation almost without any exception for 800 years. However, it was too early in the history of central banking to perceive that it was debtor pressure which promotes inflation. Governments are almost invariably debtors themselves, whereas the elites he was attacking, in general, become creditors, resisting inflation. Inflation is merely a variant of defaulting on debts, which debtor governments happen to have at their disposal because they control the currency.

At this early stage of central banking, America was largely using its vast amounts of land as a substitute for money, but quickly adapted to Hamilton's new monetary system which was far more flexible. Gallatin later played a role in the chartering of both the Second and the Third Banks, although his motives here were somewhat different. (Government caps on interest rates induced the Banks to lend to only the best risks, which amounted to favoring Philadelphia over the frontier, Gallatin's main constituency.) He was appointed U.S. Senator for Pennsylvania at the age of 32 but was evicted on a straight party vote on the ground that he had not been an American citizen for the required nine years. It seems likely that accusation was correct. He was soon elected a Congressman, becoming Chairman of Finance (later called Ways and Means), the majority leader after five years. In retrospect, while it seems perplexing that a sophisticated financier would oppose a central bank, his opposition may have been mainly against having politicians operate one, a rather unavoidable consequence of government control. Hamilton's idea that deliberately going into debt was a way to establish "creditworthiness" was denounced as particularly offensive by those who disdained indebtedness as the most dangerous sin of commercial life. The anti-Federalists were clearly wrong on this point, but it is possible to sympathize with their suspicions. Even today, the unwillingness of banks to lend money to someone who has no history of the previous borrowing is one of those things which seem so natural to bankers, and so irritating to apostles of thrift.

It remains unclear to history whether Gallatin had really never believed what he was saying, or had gradually changed his mind as he gained experience. He did confess or perhaps suddenly realize his error as the War of 1812 approached and he was Secretary of the Treasury. In this awkward event, he found himself charged with organizing the finance of a war with no way to do it. What was worse, Jefferson relentlessly pursued the closure of the National Bank for ideological, even fanatical, reasons; and Jefferson was the boss. The resolution of this conflict was to enrich Stephen Girard even further, while forcing Gallatin to a humiliating public reversal of stance. Nevertheless, America simply had to have a bank to fight a war. It is greatly to Gallatin's credit that his frenzied and obviously sincere entreaties to the bewildered Jefferson and Madison then saved the Nation from a disaster of foolish consistency. In a larger sense, the dramatic reversal of stance also played a role in shifting American sympathies from France to England. American sympathies were then wavering. On one side, there was gratitude to the French for bankrupting themselves with unwisely large loans to our struggling revolution, and for allying themselves with that revolution, soon imitating it with a revolution of their own against the common slogan, oppressive monarchy. True, there was more than a little hankering for the annexation of large chunks of Canada. That was one side of it, which Lafayette, Girard, Gallatin, and Jefferson labored to enhance, probably with their eye on French Quebec. On the other hand, there was that appalling genocide of the Jacobin guillotine, which Napoleon soon threatened to extend to all European monarchies within his reach. The Seven Years War, which we called the War of the French and the Indians, had left memories in America that French ambition could extend from Quebec to Louisiana and include Haiti. The French once even occupied Pittsburgh, and their Indian allies had scalped settlers in Lancaster. That was not so long ago. Furthermore, the English invention of the Industrial Revolution was immensely attractive to artisan Americans. Ultimately, we made our choice for steady prosperous commerce of the British sort, rather than glittering glorious conquest, of the French style. By 1813, Gallatin had served longer as Secretary of Treasury than anyone before or since, and earlier had a more distinguished career as both Congressman and Senator than all but a few have ever achieved. When he was offered the position as a commissioner to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812, it was natural to expect that it would be the final act of his long political career. It was, however, only the beginning of a ten-year diplomatic career as Ambassador, first to France and then to England. Following that with still another new career, he took up academic work, returning to America to found New York University, personally establishing the academic discipline of study in Indian Affairs and language, and founding the American Ethnological Society. Gallatin wrote two books about Indian language patterns and first suggested that the similarities between the languages of North and South American Indians probably meant they were related tribes. In another sphere, Gallatin is credited with originating the American doctrine of manifest destiny.

While skipping from one distinguished career to several others, Gallatin never forgot he was a banker. He wrote the charter for the Second National Bank ("Biddle's Bank"), plus the Third Bank of Pennsylvania, and founded the National Bank of New York, which was named Gallatin's Bank for a while, before gradually evolving into what is now called J.P. Morgan Chase Bank. As a diplomat, he negotiated many boundary disputes, including Oregon, Maine, and Texas. He bitterly opposed the annexation of Texas.

When it comes to writing about Gallatin, there is so much to say it is hard to say anything coherent. He was such a virtuoso of public life that he defeats his biographers in their central task, of telling the world what he was like. There haven't been many if indeed there were any, enough like him to offer a comparison. And yet history has not been kind to him. He can comfortably claim the title of the most famous American, that no one since has ever heard of.

Originally published: Friday, November 02, 2007; most-recently modified: Monday, May 13, 2019

| Posted by: Cardume | Apr 23, 2012 10:31 PM |

| Posted by: Tanya Love | Oct 6, 2011 5:23 PM |