7 Volumes

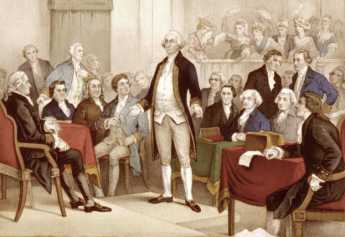

Constitutional Era

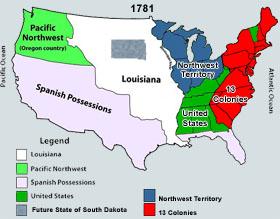

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Invaders of Pennsylvania

For a peaceful state, Pennsylvania has suffered many invasions. It's all been one-way; Pennsylvania has never invaded anyone else.

Colonial Times

More than half of American history took place before 1776, but after 1492. For Philadelphia, Colonial history lasted about a century.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Worldwide Common Currency and Corporate Headquarters

The Death of Money

Great 1929 Depression and World War Two

The Treaty of Versailles probably caused World War II, making WW II just a continuation of WW I.

Pacifist Pennsylvania, Invaded Many Times

Pennsylvania was founded as a pacifist utopia, and currently regards itself as protected by vast oceans. But Pennsylvania has been seriously invaded at least six times.

Pennyslvania's Boundary: David Rittenhouse, Hero, Lord Baltimore, Villain

|

| David Rittenhouse |

In the Twenty-first Century, when we know how every American creek and river run, we can see it might have been simple to establish a boundary between the new royal grant to William Penn, and an earlier grant to Lord Baltimore by the then-reigning king's father, Charles I. Essentially: Penn got the Delaware Bay and a lot of wilderness to the west of it. George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had long held the top half of the Chesapeake Bay and a strip of wilderness to the west of that. Two bays, with two hazy strips of wilderness attached.

|

| George Calvert, Lord Baltimore |

At what is now Odessa, Delaware, those two bays are only five miles apart; compromise should have settled the issue quickly. Two English gentlemen could have sat down over a pipe and a brew, working something out. However, the English nation was then changing kings, beheading them over matters of religion. A Roman Catholic, Lord Baltimore probably thought an opportunity might emerge from the turmoil if he stalled until matters went his way, since next in line of succession was James, Duke of York, who was a Catholic. But matters fall into the hands of the lawyers when principals of an argument are unable to speak. As we noted elsewhere, in the legal system of the day the last word from the last king was what counted in law courts, accepting any uncertainty about future latest words from future latest kings in order to maintain immediate peace. To lawyers of the time, all this talk about justice, fairness, and geometry was idleness when the nation needed order and stability. So the Calvert family lawyers over the course of eighty years, introduced one specious proposition after another that turned other lawyers purple with rage. Penn's lawyer, Benjamin Chew, beat them at this game, and his mansions in Delaware and Germantown attest to the value attached to this achievement. In other circumstances, posturing might have led to war, as it did in similar disputes with Connecticut. Penn probably knew better, but it takes two to compromise.

|

| Mason-Dixon Line |

It must be admitted that honest confusion was possible. Sometimes, a line of latitude was a line in the sense Euclid intended: all length and no width. At other times, lawyers and kings were talking about "parallels" as if they were strips, roughly sixty miles wide. If a sixty-mile strip was intended, it was important for a grant to specify whether it extended to the southern edge of the strip, or to the northern edge. But in fact, the state of science in the Seventeenth Century contained uncertainty about both where the strips were, and how wide. And if the grant's language didn't even make it clear whether the parties were talking about strips or width-less lines, eighty years could be a comparatively short time for a court to decide the case. To be fair to Lord Baltimore, many people at the time didn't think these matters were capable of fair solution, so the traditional way of dealing with land disputes was either by force or by craftiness.

|

| David Rittenhouse Birth Place |

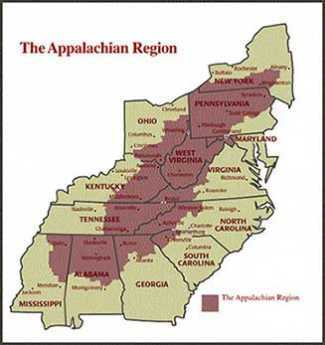

In William Penn the folks from Maryland were, unfortunately, dealing with a friend of the King, who had one of the most brilliant mathematicians in Western civilization as his adviser. David Rittenhouse may have been born in that little farmhouse you can still visit on the Wissahickon Creek, and made his living as a clockmaker, but his native talents in mathematics, astronomy surveying, and instrument construction were so deep and so varied that later biographers are reduced to describing him merely as a "scientist" and letting it go at that. If you want to sample his talents, spend an hour or two learning what a vernier is, and then see if you could apply that insight, as he did, to a compass. So, as it turned out, Rittenhouse was able to describe a twelve-mile circle around New Castle, Delaware, construct a tangent that divides the Delmarva's Peninsula in half, and match it up with an east-west line we now call the Mason Dixon Line. When they finally got around to laying these lines on the ground, Mason and Dixon cut a twenty-four-foot swath through the forest, using astronomical adjustments every night, and laying carved marker stones every fifth of a mile for hundreds of miles. The variation from the line devised by Rittenhouse was at most a fifth of a mile off the mark; the intersection with the north-south line between Maryland and Delaware was less successful. The survey by Mason and Dixon was not quite completed to the Ohio line because the Indians, curious at first, eventually became wild with suspicion at such behavior, particularly the part about going out and aiming cannons at the sky every night. It seems likely that George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had no more confidence in this madness than the Indians did.

So, the next time you take the train from Philadelphia to Washington DC, reflect that strict reading of the words in the land grants did admit the possibility that your whole trip could either have been within the State of Maryland, or else in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, depending on whether lawyers, or scientists, had triumphed in this dispute. Since the Mason Dixon Line later divided not merely two states, but two violently opposed cultures, Rittenhouse must stand out in the history of one of those people who were so smart that most people couldn't understand how smart he was.

City Troop

|

| First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry (FTPCC) |

On 23rd Street, just South of Market, stands a gloomy Victorian castle with big doors opening to the street. It's the armory, housing the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry (FTPCC). The organization is a real fighting unit of the Pennsylvania National Guard, participating with distinction in every war America has fought. Originally a horse cavalry, the unit now drives tanks, except for recreation and on ceremonial occasions. It lays claim to being the oldest military unit in America, although there have been several minor name changes since the days when the City Troop accompanied General Washington to take command of the troops in Boston. Their dress uniforms are pretty splashy, especially on horseback, and they have to pay for them, themselves.

Furthermore, they are required to donate all of their military pay toward the upkeep of the unit and its activities. Although the first step in membership is to become a real member of the National Guard, election to the Troop itself is truly an election, carefully screened after prospective members have been observed and evaluated at invited Troop functions. These soldiers are wealthy, athletic, mostly pretty handsome, and almost invariably well-connected socially. You could almost make up the rest from these essential ingredients. This is the innermost core of Philadelphia society, and it is intensely and sincerely patriotic.

Others have noticed that National Guard duty itself takes up many weekends and much of summer vacation. Add to that the many Troop dinners, the horsemanship activities, the debutante balls, the Chesapeake sailing cruises, the national and local ceremonies, the weddings and funerals for members -- and actually fighting wars overseas. The members of the Troop spend so much of their time on Troop-related activities, that they become both intensely loyal to each other, and necessarily somewhat withdrawn from other people. They gravitate to polo, the Racquet Club, the Savoy, the Orpheus, and the financial world.

There may be an important insight into the generation turmoils to be derived from this. There was once a time when most professions likewise absorbed the lives of their members, with professional clubs and entertainments confining the social life of the member by leaving little time for anything else. But in recent years most occupational and professional societies are experiencing a loss of membership and enthusiasm, leading to the bewildering question of "Where are the younger members, any more?" The pre-fabricated answer is that younger people now want to devote their quality time to their families, but if you believe that, you will believe anything. Let's face it; when one activity absorbs all of your time, it confines you. There have to be some important benefits to being so confined, and even so, it chafes a little. Those of us who are not baby boomers can see that being a slave to intra-generational consensus is only to be a slave in a different way. The remarkable thing is that the baby boomers fail to see it, themselves.

George Washington's View of the British Army

|

| George Washington |

TWO things about George Washington continue to puzzle us. Why would the rich, aristocratic Virginia gentleman become a revolutionary? And, how could he or his backwoodsmen soldiers even imagine they could defeat the British, the greatest military force in the world? The following letter, written to his mother after the defeat of Braddock's army, shows his viewpoint at the age of 23, putting the British regular army in a very bad light, indeed.

"HONORED MADAM: As I doubt not but you have heard of our defeat, and, perhaps, had it represented in a worse light, if possible, than it deserves, I have taken this earliest opportunity to give you some account of the engagement as it happened, within ten miles of the French fort, on Wednesday the 9th instant.

"We marched to that place, without any considerable loss, having only now and then a straggler picked up by the French and scouting Indians. When we came there, we were attacked by a party of French and Indians, whose number, I am persuaded, did not exceed three hundred men; while ours consisted of about one thousand three hundred well-armed troops, chiefly regular soldiers, who were struck with such a panic that they behaved with more cowardice than it is possible to conceive. The officers behaved gallantly, in order to encourage their men, for which they suffered greatly, there being near sixty killed and wounded; a large proportion of the number we had.

"The Virginia troops showed a good deal of bravery and were nearly all killed; for I believe, out of three companies that were there, scarcely thirty men are left alive. Captain Peyrouny and all his officers down to a corporal were killed. Captain Polson had nearly as hard a fate, for only one of his was left. In short, the dastardly behavior of those they call regulars exposed all others, that were inclined to do their duty, to almost certain death; and, at last, in spite of all the efforts of the officers to the contrary, they ran, as sheep pursued by dogs, and it was impossible to rally them.

"The General was wounded, of which he died three days after. Sir Peter Halket was killed in the field, where died many other brave officers. I luckily escaped without a wound, though I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me. Captains Orme and Morris, two of the aids-de-camp, were wounded early in the engagement, which rendered the duty harder upon me, as I was the only person then left to distribute the General's orders, which I was scarcely able to do, as I was not half recovered from a violent illness, that had confined me to my bed and a wagon for above ten days. I am still in a weak and feeble condition, which induces me to halt here two or three days in the hope of recovering a little strength, to enable me to proceed homewards; from whence, I fear, I shall not be able to stir till toward September; so that I shall not have the pleasure of seeing you till then, unless it be in Fairfax... I am, honored Madam, your most dutiful son."

Franklin Bets His Wad on General Braddock

|

| General Edward Braddock |

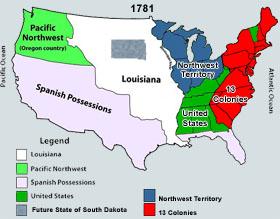

The defeat of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) in 1755 was not a turning point of the French and Indian War, because although the French won the battle, they lost that War, they also lost Canada in the Seven Years War that followed, and eventually had to sell what remained of their American dream in 1804 as the Louisiana Purchase. The French dream was an empire stretching in an arc from the St. Lawrence River to New Orleans, leaving the British only the thirteen Eastern seaboard colonies.

Nevertheless, the disastrous defeat of the Redcoats was a real turning point in the attitudes of two direct participants, Lieutenant Colonel George Washington of Virginia, and Pennsylvania's political leader, Benjamin Franklin. Both men greeted the arrival of Braddock's troops in America with great relief because it was increasingly evident to them that the Colonies themselves were too indecisive to survive. Both of them were in a unique personal position to see that the French and their Indian Allies were serious about conquering the backcountry, even likely to do so. These two staunch British patriots, therefore, threw themselves into the crisis, with Washington eventually having two horses shot from under him, taking charge of the retreat after Braddock's death. And Franklin pledged his considerable personal fortune on Braddock's behalf, almost losing it and spending the rest of his life in debtor's prison as Robert Morris would later actually do. These two men knowingly laid their lives on the line for the British Empire and came very close to losing everything else for their King and country.

Franklin had retired seven years earlier, a rich man at the age of 42. We now know that he lived like a gentleman for another 42 eventful years. Puttering with science and public works, he joined the Assembly in 1750. It was not long before he was the political leader of the Colony, in a peculiar struggle with the dominant Quaker party who not only opposed war for their own self-defense but were enraged that the Penn family had turned away from Quakerism and refused to be taxed for the defense of its colony. The Governor was appointed by the Penns, with an express contract not to agree to any taxation of the Penn holdings. Since it began to look to Franklin as though everybody was trying to commit suicide rather than spend a farthing, he greeted the arrival of General Edward Braddock's redcoats with great relief. But then Braddock himself turned out to be a brave but exasperating ninny.

Braddock's plan was to take the old Indian trail from the Potomac River to the Monongahela (now Route 40), fording the Monongahela just below its junction with Ohio at Fort Duquesne, then blowing up the French fort with artillery. He had brought plenty of troops and cannons on his ocean transports, but he needed horses and wagons from the colonies. When he was warned of the dangers of Indian ambush in the wilderness, he made a much-quoted response, "These savages may be a formidable enemy to your raw American militia, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops, sir, it is impossible they would make an impression." The other thing he said was if he didn't get wagons and horses pretty damned quick, he was going back home to England.

Within two weeks, Franklin and his son William collected 259 horses and 150 wagons for him. But to do so, they had to overcome the Pennsylvania farmer suspicion that the swaggering English General wouldn't pay for the goods. To persuade them, Franklin made a public pledge to stand behind the debts with his own money, and his word was known to be good.

The other thing wrong with Braddock's plan was that the trail wasn't wide enough for the wagons and gun carriages, so he had so sent a body of axeman ahead of the troops to widen the road. Progress was at times as slow as two miles a day, plenty of time for word to be taken to Fort Duquesne that the British were coming with cannon. Since it was clear that the Fort could not withstand a siege army, the French commander ordered his troops to attack Braddock as he was crossing the Monongahela. It was meant to be an ambush, but the two armies blundered into each other on the trail, and the Indians simply fought the way they knew best, from behind trees. Two-thirds of the British were killed and most of those captured were burned at the stake. The death toll would have been even higher, and probably would have included Washington, except the Indians, ignored French orders and delayed pursuit to collect scalps. And by the way, all of Franklin's wagons were burned.

Franklin spent an anxious two months since his later reflection was that the loss of 20,000 pounds sterling would surely have ruined him. However, he was lucky that Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, an old friend of his, was appointed at Braddock's successor, and Shirley ordered the debt to be repaid out of Army funds.

The American Revolution would not come for another twenty years, but you can be sure the Braddock episode had an important impact on the minds of both Franklin and Washington. The British Army was not invincible. It was not even very smart.

Politics of the French and Indian War

|

| Isaac Sharpless |

In the European view, the French and Indian War was a mere skirmish in the many-year conflict between France and England. But the Atlantic is a wide ocean. The local Pennsylvania politics of that war concern the land-hungry settlers striving for Indian lands, the Quaker Assembly doing its best to maintain William Penn's formula for peace ("No settlements without first buying the land from the Indians."), and William Penn's far-from-idealistic Anglican sons, focused on profit from a land rush. Western Pennsylvania belonged to the Delaware tribe, but the Delawares were subject to the Iroquois nation. The year is 1754. The following pro-Quaker description is given by Isaac Sharpless, president of the Quaker Haverford College between 1887 and 1917 (Political Leaders of Colonial Pennsylvania,

|

| Isaac Norris |

Isaac Norris was appointed to another Albany treaty with the Indians in 1754. The commission consisted of John Penn and Richard Peters representing the Proprietors, and Benjamin Franklin and himself, the Assembly. Indian relations were becoming difficult. The Five Nations still claimed the right to the ownership of Pennsylvania and insisted that no sale of land by the Delawares was permissible. In an evil hour, the government of Pennsylvania recognized this claim and this Albany meeting was for the purpose of effecting a purchase. By methods that were more or less unfair, taking advantage of the Indian ignorance of geography, they bought for 400 pounds all of southwestern Pennsylvania. When the Delawares found their land had been sold without their consent, they threw off the Iroquois yoke, joined the French, defeated Braddock's army a year later and for the first time in the history of the Colony the horrors of Indian warfare were known on the frontiers.

Although Sharpless goes directly to the unvarnished truth of the situation, he reveals the depth of his bitterness by openly discarding Franklin's cover story about being in Albany to propose political unity among the British colonies.

It was on this expedition that Franklin presented to his fellow delegates his plan for a union of the Colonies, of course in subordination to the British Crown which was a precursor of the final union in Revolutionary days. Sixty years earlier William Penn had proposed a somewhat similar scheme.

The war came, French intrigue and the unwisdom of the Executive branch of the government of the Province (the Penns) drove the Indians, who for seventy-three years had been friendly, into the warpath. Cries came in from the frontiers of homesteads burnt, men shot at their plows, women, and children scalped or carried into horrible captivity, and a growing sentiment among the red men that the French were the stronger and that the English were to be driven into the sea.

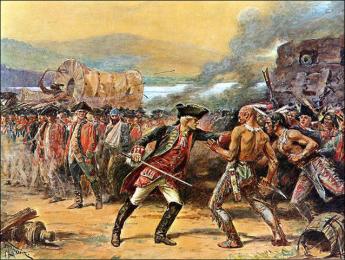

Germantown and the French and Indian War

|

| The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army |

Allegheny Mountains from which to trade with, and possibly convert the Indians, the French had a rather elegant strategy for controlling the center of the continent. It involved urging their Indian allies to attack and harass the English-speaking settlements along the frontier, admittedly a nasty business. The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army at what is now Pittsburgh reported hearing screams for several days as the prisoners were burned at the stake. Rape, scalping and kidnapping children were standard practice, intended to intimidate the enemy. The combative Scotch-Irish settlers beyond the Susquehanna, which was then the frontier, were never terribly congenial with the pacifism of the Eastern Quaker-dominated legislature. The plain fact is, they rather liked to fight dirty, and gouging of eyes was almost their ultimate goal in any mortal dispute. They had an unattractive habit of inflicting what they called the "fishhook", involving thrusting fingers down an enemy's throat and tearing out his tonsils. As might be imagined, the English Quakers in Philadelphia and the German Quakers in Germantown were instinctively hesitant to take the side of every such white man in every dispute with any redone. For their part, the Scotch-Irish frontiersmen were infuriated at what they believed was an unwillingness of the sappy English Quaker-dominated legislature to come to their defense. Meanwhile, the French pushed Eastward across Pennsylvania, almost coming to the edge of Lancaster County before being repulsed and ultimately defeated by the British.

In December 1763, once the French and Iroquois were safely out of range, a group of settlers from Paxtang Township in Dauphin County attacked the peaceable local Conestoga Indian tribe and totally exterminated them. Fourteen Indian survivors took refuge in the Lancaster jail, but the Paxtang Boys searched them out and killed them, too. Then, they marched to Philadelphia to demand greater protection -- for the settlers. Benjamin Franklin was one of the leaders who came to meet them and promised that he would persuade the legislature to give frontiersmen greater representation, and would pay a bounty on Indian scalps.

Very little is usually mentioned about Franklin's personal role in provoking some of this warfare, especially the massacre of Braddock's troops. The Rosenbach Museum today contains an interesting record of his activities at the Conference of Albany. Isaac Norris wrote a daily diary on the unprinted side of his copy of Poor Richard's Almanac while accompanying Franklin and John Penn to the Albany meeting. He records that Franklin persuaded the Iroquois to sell all of western Pennsylvania to the Penn proprietors for a pittance. The Delaware tribe, who really owned the land, were infuriated and went on the warpath on the side of the French at Fort Duquesne. There may thus have been some justice in 1789 when the Penns were obliged to sell 21 million acres to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for a penny an acre.

Subsequently, Franklin became active in raising troops and serving as a soldier. He argued that thirteen divided colonies could not easily maintain a coordinated defense against the unified French strategy, and called upon the colonial meeting in Albany to propose a united confederation. The Albany Convention agreed with Franklin, but not a single suspicious colony ratified the plan, and Franklin was disgusted with them. Out of all this, Franklin emerged strongly anti-French, strongly pro-British, and not a little skeptical of colonial self-rule. Too little has been written about the agonizing self-doubt he must have experienced when all of these viewpoints had to be reversed in 1775, during the nine months between his public humiliation at Whitehall, and his sailing off to meet the Continental Congress. Furthermore, as leader of a political party in the Pennsylvania Legislature, he also became vexed by the tendency of the German Pennsylvanians to vote in harmony with the Philadelphia Quakers, and against the interest of the Scotch-Irish who were eventually the principal supporters of the Revolutionary War. It must here be noticed that Franklin's main competitor in the printing and publishing business was the Sower family in Germantown. Franklin persuaded a number of leading English non-Quakers that the Germans were a coarse and brutish lot, ignorant and illiterate. If they could be sent to English-speaking schools, perhaps they could gradually be won over to a different form of politics.

Since the Germans of Germantown was supremely proud of their intellectual attainments, they were infuriated by Franklin's school proposal. Their response was almost a classic episode of Quaker passive-aggressive warfare. They organized the Union School, just off Market Square. It was eventually to become Germantown Academy. Its instruction and curriculum were so outstanding as to justify the claim that it was the finest school in America at the time. Later on, George Washington would send his adopted son (Parke Custis) to school there. In 1958 the Academy moved to Fort Washington, but needless to say, the offensive idea of forcing the local "ignorant" Germans to go to a proper English school was rapidly shelved. This whole episode and the concept of "steely meekness" which it reflects might be mirrored in the Japanese response, two centuries later, to our nuclear attack. Without the slightest indication of reproach, the Japanese wordlessly achieved the reconstruction of Hiroshima as now the most beautiful city in the modern world.

The Pennamite Wars: Who Had The Last Word?

|

| King Charles II |

Pennsylvania once fought three wars with Connecticut, but nowadays most people in both Connecticut and Pennsylvania have never heard of it. Those who do know, call them the Pennamite Wars. As you might expect, accounts by Connecticut patriots portray the matter as just taking possession of what they owned. Pennsylvania accounts of the wars, on the other hand, describe them as a stout defense against invasion. The matter boils down to the undisputed fact that King Charles II gave what is now the northern third of Pennsylvania to Connecticut in 1662, and in 1681 the same king gave it to William Penn. Eighty years after that, in 1769, Connecticut moved in, and Pennsylvania threw them out. It all happened twice more, and the Continental Congress became distressed that two of the thirteen colonial allies were fighting each other instead of the British. So it had to be resolved in court, and therefore we all have to get a little education in the fine points of real estate law in order to understand why Pennsylvania won the case. In short, Connecticut claimed that Charles II had cruelly and unjustly reversed himself, while the Penn Proprietorship simply maintained they were nonetheless legally entitled to the property.

Let's look at this dumb situation from the lawyers' point of view. If you own some land, but someone says you don't, your first response would be to show that the last owner turned it over to you without strings attached. And then you show that the title passed person-to-person backward in a clear chain of unclouded ownership. As long as this is provable, the critical deciding factor rests on what right the "original" owner had to it, from the Indians, or a King, or government charter. No one can be found to claim ownership earlier than that, so it must be yours.

The critical point is that "the original owner" is, therefore, the first private (non-governmental) owner. We are so used to this legal convention that it can be upsetting to discover that things were exactly opposite when we had a king -- and that our courts still uphold the monarch's decrees. Kings had a right to do absolutely anything, and that divine right, therefore, included the ability to revoke private ownership and take the property back or give it to someone else. Establishing a clear title is now a process of tracing back to the last moment when someone still had an absolute right to do anything he pleased with it. If what he did was cruel and unjust, too bad.

As soon as you trace your title back to a king or other absolute tyrant, the courtroom situation effectively reverses. At that critical turning point, the important issue stops being what a still-earlier owner intended and becomes what the final owner said. The last word of the last monarch extinguishes anything intended by anybody earlier. Even after all this ponderous logic is thoroughly explained, perhaps even repeated, the loser of a case goes away dissatisfied and angry. It ain't right.

It is right, of course, since you can't be an absolute monarch if you can't do what you please. If someone was an absolute monarch in the past, whatever he said was his right, and it would be disruptive to overturn in retrospect what seemed perfectly orderly at the time. The whole progress from Magna Carta to American Revolution was to accept old confiscations as final, as the necessary price of putting an end to having any new ones. After the cutoff point, the right to transfer property became the sole discretion of the current owner. The transfer of sovereignty from governmental to individual ownership was a serious main issue in the Revolutionary War.

Pennsylvania thus fought three Pennamite wars with Connecticut over conflicting land grants by kings, and also got into hot but non-military quarrels with Virginia and Maryland over much the same issues. If Pennsylvania had lost these disputes, the Commonwealth would now be little more than an eighth its present size. Pittsburgh would be in Virginia, Scranton would be in Connecticut, and Philadelphia would be a city in Maryland. Perhaps that wouldn't be so bad -- after all, maybe they don't have a city wage tax in Maryland.

What would be very bad, and therefore is the heart of the matter, is that we probably would have undergone two hundred years of contested titles and maybe even shooting wars, as a result of having property ownership in constant dispute. After a couple of generations, it matters less who was right and who was wrong. What begins to matter more is that things get fairly and finally settled so everyone can get on with his life.

Franklin Declares Independence a Year Early

Joseph Priestly became a close friend of Benjamin Franklin almost as soon as they met. Priestly was an Anglican clergyman who broke loose and formed the Unitarian Church, and meanwhile, his scientific discoveries also entitle him to be called the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, of course, was the discoverer of electricity; it would be hard to be sure which of the two was more brilliant. In July, 1775, Franklin wrote the following letter to Priestly, which makes a trenchant case that the American colonies should, and would, break away from England. Since some legal authorities, following Lincoln's lead, maintain that Jefferson's manifesto "informs" the United States Constitution, it might be well to begin referring to this letter as an even clearer statement of the mindset of America's founding leaders.

|

| General Thomas Gage |

" Dear Friend (wrote Franklin),

"The Congress met at a time when all minds were so exasperated by the perfidy of General Gage, and his attack on the country people (i.e. Of Lexington and Concord), that propositions of attempting an accommodation were not much relished; and it has been with difficulty that we have carried another humble petition to the crown, to give Britain one more chance, one opportunity more of recovering the friendship of the colonies; which however I think she has not sense enough to embrace, and so I conclude she has lost them forever.

"She has begun to burn our seaport towns; secure, I suppose, that we shall never be able to return the outrage in kind. She may doubtless destroy them all; but if she wishes to recover our commerce, are these the probable means? She must certainly be distracted; for no tradesman out of Bedlam ever thought of increasing the number of his customers by knocking them on the head; or of enabling them to pay their debts by burning their houses.

"If she wishes to have us subjects and that we should submit to her as our compound sovereign, she is now giving us such miserable specimens of her government, that we shall ever detest and avoid it, as a complication of robbery, murder, famine, fire, and pestilence.

"You will have heard before this reaches you, of the treacherous conduct to the remaining people in Boston, in detaining their goods, after stipulating to let them go out with their effects; on pretence that merchants goods were not effects; -- the defeat of a great body of his troops by the country people at Lexington; some other small advantages gained in skirmishes with their troops; and the action at Bunker's-hill, in which they were twice repulsed, and the third time gained a dear victory. Enough has happened, one would think, to convince your ministers that the Americans will fight and that this is a harder nut to crack than they imagined.

"We have not yet applied to any foreign power for assistance; nor offered our commerce for their friendship. Perhaps we never may: Yet it is natural to think of it if we are pressed.

"We have now an army on our establishment which still holds yours besieged.

"My time was never more fully employed. In the morning at 6, I am at the committee of safety, appointed by the assembly to put the province in a state of defense; which committee holds till near 9, when I am at the Congress, and that sits till after 4 in the afternoon. Both these bodies proceed with the greatest unanimity, and their meetings are well attended. It will scarce be credited in Britain that men can be as diligent with us from zeal for the public good, as with you for thousands per annum. -- Such is the difference between uncorrupted new states and corrupted old ones.

"Great frugality and great industry now become fashionable here: Gentlemen who used to entertain with two or three courses, pride themselves now in treating with simple beef and pudding. By these means, and the stoppage of our consumptive trade with Britain, we shall be better able to pay our voluntary taxes for the support of our troops. Our savings in the article of trade amount to near five million sterling per annum.

"I shall communicate your letter to Mr. Winthrop, but the camp is at Cambridge, and he has as little leisure for philosophy as myself. * * * Believe me ever, with sincere esteem, my dear friend, Yours most affectionately."

[Philadelphia, 7th July, 1775.]

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

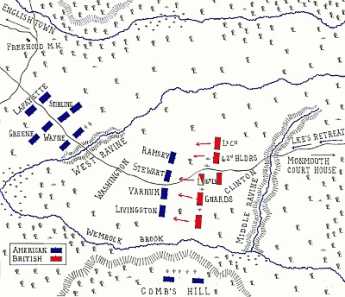

Philadelphia's Two Years Under Attack: A Chronology

June 1776 to June 1777 Although Virginia and New England were rebellious, the Quaker states regarded the British with sympathy until Benjamin Franklin was humiliated at Whitehall and returned to America as an ardent rebel. Either the English did not perceive or were unable to exploit this divisiveness, and made the mistake of dispatching an enormous fleet with 40,000 soldiers in a sign they meant to subjugate all of America. In a second mistake, this expeditionary force was headquartered on Staten Island, an ideal place to dominate the surrounding six colonies rather than the more fractious colonies of Massachusetts and Virginia. With this military force on its doorstep, the middle colonies finally joined the rest on July 2, 1776, and asked Thomas Jefferson to write a proclamation about it. The British soon advanced on land from Perth Amboy to Trenton, left a detachment of Hessians and went into winter quarters in New Brunswick. Washington attacked the Hessians, and when Cornwallis came storming to the rescue, circled around him and went after the unprotected supplies in New Brunswick. Cornwallis gave chase and lost the battle of Princeton. Washington went into winter quarters in Morristown, waiting for General Howe to react in the spring. Howe feigned embarkation and nearly trapped Washington, but soon went back to his lady friend in New York for the winter.

July 25, 1777 Admiral Lord Richard Howe and his brother General Sir Willliam Howe set sail from Staten Island for destination unknown. Washington watches helplessly from across the inlet at Perth Amboy, then falls back toward Philadelphia to protect his options.

July 31, 1777 British fleet sighted at the mouth of Delaware Bay. Washington moves to the Germantown encampment (now Fox and Queen Lane), prepared to defend the capital at Philadelphia.

August 10, 1777 When Howe, feeling he must destroy Washington before attacking the Delaware fortifications, does not enter the Delaware River, Washington orders the troops to go back up Old York Road to the Neshaminy encampment, midway between the head of the Chesapeake Bay and New York Harbor, because Howe's intentions are still unclear. Headquarters at Moland House in Bucks County.

August 23,1777 Howe's fleet is sighted off Patuxent, Maryland, then at Elkton, Maryland. Washington orders troops to defend along the Brandywine Creek. Howe lands Aug 25, in a driving rainstorm, possibly an Atlantic hurricane.

September 11, 1777 Washington is outflanked by Cornwallis' forced march around Dilworthtown, while Howe attacks the Brandywine in the largest military engagement of the Revolutionary War. Washington withdraws to Chester.

September 13, 1777 Washington stays only briefly at Chester, and returns his troops to the Germantown encampment they used a month earlier. From there he destroys all bridges and boats on the Schuylkill, then redeploys around Norristown, the first ford available to the British.

September 16, 1777, Both sides maneuver over a large area in Chester County for a second stage of the Battle of Brandywine, but a second torrential rainstorm ruins everyone's gunpowder ("The Battle of the Clouds") and fighting ceases. A contingent of 1500 Americans under General Wayne is surprised and butchered at night by a bayonet attack ("The Paoli Massacre"), and Howe crosses the Schuylkill on September 23 while Washington is forced to watch helplessly from the Whitemarsh area.

September 26, 1777. Howe marches triumphantly into Philadelphia but immediately splits his army into three groups, one directed at Fort Mifflin, one sent to New Jersey to forage, and the third but main body of troops deployed in Germantown. Washington sees an opportunity and organizes an attack on the Germantown contingent.

October 4, 1777. Battle of Germantown. The British successfully defend their position around the massive stone Cliveden (Chew) Mansion, and Washington is forced to fall back to Whitemarsh.

October 19 - November 16, 1777. Siege of Fort Mifflin, which eventually falls to the British, but not before their stunning defeat at Ft. Mercer on the New Jersey side of the river. The British fleet can now bring supplies up the river to a British army which was running low of them.

December, 1777 - June, 1778. The British enjoy winter quarters in Philadelphia, while Washington's troops suffer at Valley Forge.

June, 1778. The British defeats at Trenton and Saratoga persuaded the French to ally with the Revolutionaries. A hundred miles from blue water, concern about a French fleet prompts the British to withdraw from Philadelphia, crossing Delaware and marching up King's Highway in New Jersey to rejoin the British fleet at Perth Amboy/New Brunswick.

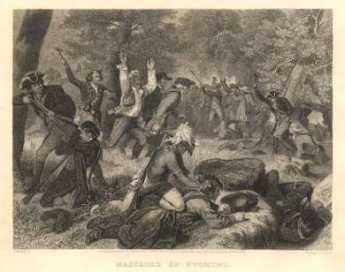

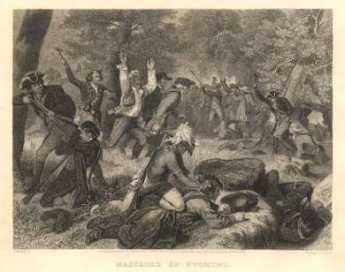

July 3, 1778. The Iroquois, urged on by the British, massacre 600 settlers in the Wyoming Valley, around present-day Wilkes Barre. General Sullivan is dispatched to annihilate the Iroquois. Hostilities in the war now shift to the Southern part of the country for the next six years.

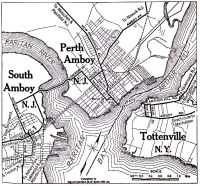

British Headquarters: Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in its 1776 Heyday (B 608)

Not many now think of the town of Perth Amboy as part of Philadelphia's history or culture, but it certainly was so in colonial times. Sadly, the town has since declined to a condition of a quiet middle-class suburb. There are quite a few Spanish-language signs around and some decaying factories. The little house of the Proprietors on the town square and the remains of the Governor's mansion overlooking the ocean are about all that remain of the early Quaker era.

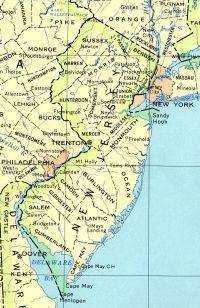

|

| NJ MAP |

To understand the strategic importance of Perth Amboy to Colonial America, remember that James, Duke of York (eventually to become King James the Second) thought of New Jersey as the land between them North (Hudson) River, and the South (Delaware) River. This region has a narrow pinched waist in the middle. It's easy to see why the land-speculating Seventeenth Century regarded the bridging strip across the New Jersey "narrows" as a likely future site of important political and commercial development. The two large and dissimilar land masses which adjoin this strip -- sandy South Jersey, and mountainous North Jersey -- was sparsely inhabited and largely ignored in colonial times. The British in 1776 developed the quite sensible plan that subduing this fertile New Jersey strip would simultaneously enable the conquest of both New York and Philadelphia at the two ends of it. It was a clever plan; it might have subjugated three colonies at once.

|

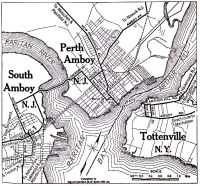

| PERTH AMBOY MAP |

Perth Amboy is a composite name, adding a local Indian word to a Scottish one because East Jersey had been intended for Scottish Quakers. Like Pittsburgh at the conjunction of three rivers, Perth Amboy's geographical importance was that it dominated the mouth of Raritan Bay (Raritan River, extended) as it emptied into New York Bay just inside Sandy Hook. Two of the three "rivers" of the three-way fork are really just channels around Staten Island. Viewed from the sea, Perth Amboy sits on a bluff, commanding that junction. Amboy became the original ocean port in the area, although it was soon overtaken by New Brunswick further inland when increasing commerce required safer harbors. Perth Amboy was the capital of East Jersey, and then the first capital of all New Jersey after East and West were joined in 1704 by Queen Anne. The Royal Governor's mansion stood here, as well as grand houses of Proprietors and Judges overlooking the banks of the bay. The main reason for the Nineteenth-century decline of the state capital region was the narrowness of the New Jersey waist at that point; its main geographical advantage became a curse. Canals, railroads and astounding highway growth simply crowded the Amboy promontory into an unsupportable state of isolation. The same thing can be said of Bristol, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware, but local civic pride has somehow not risen to the challenge to the same degree.

Easy Ride: Perth Amboy to Trenton

The Revolutionary War had been raging for a year in New England before the Declaration of Independence, a point that never ceased to bother John Adams whenever Thomas Jefferson or his devotees took credit for starting the Revolution with a piece of paper nailed to a lamp post a year after Lexington and Concord. This interval nevertheless allowed for the organization of the Continental Army, and Washington's maturing military background by the summer of '76. It also allows the time for the surprisingly immediate landing of Sir William Howe's army on Staten Island at the end of June 1776. A month or so after that, his brother Admiral Howe landed more troops. By September 1776, not all of the signers had yet put their names to the Declaration of Independence, but there were about 40,000 British troops parading around the essentially uninhabited Staten Island in New York harbor, in plain sight of the inhabitants of New Jersey's capital in Perth Amboy, and scarcely a hundred miles from Philadelphia. Massachusetts and other New England Patriots have a point when they claim the Declaration of Independence marked the end of the first year of rebellion against British rule, while the other colonies prefer to say July 4, 1776, was the beginning of the war for independence. It was an irrevocable gesture of unified defiance, a copy of which was sent to the personal attention of George III.

The British shrewdly selected New York harbor as the center of their operation, since their Navy was thereby in position to shift quickly in the protected waters of Long Island Sound from New Jersey to Rhode Island, or up and down the Hudson as far as Albany, meanwhile dominating the considerable expanse of Long Island, not to mention Manhattan. It was only eighty miles travel across the narrow waist of New Jersey to the top of Delaware Bay at Trenton, potentially also leading to control of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, land-locked Washington was faced with crossing numerous rivers to defend hundreds of miles of shoreline, moving foot soldiers to defensive positions. He tried to defend New York, it is true, but the battles on Brooklyn Heights, Harlem, Fort Washington and Fort Lee were essentially unwinnable, and the best he could really do with the situation was escape with an undestroyed army. Being farther from the reach of the British Navy, Philadelphia was more defensible than New York, and besides, it was now the capital of the rebellion.

|

| Cornwallis |

By the fall of 1776 Howe had consolidated his hold on New York, and Washington was reduced to scattering small clusters of troops around the places Howe might likely invade. Those clusters were reassuring to their neighbors and easy to provision locally, but equally easy for the British to overwhelm. Washington was a better general than it seemed; these several bands of about 500 militia were expected to remain in readiness to be summoned as soon as the main British force committed itself to a major objective. In early December, the British started landing in New Jersey and marched toward New Brunswick. Washington thought that meant he was going to head for Trenton, and then down Delaware to Philadelphia. There was not much to stop him except skirmishers and Minute Men, but it was unsafe for Washington to move his troops from the New York region until the intentions of the swifter British were really clear. By that time it might be too late to stop an advance, but it couldn't be helped. Washington was inventing guerrilla warfare, patterned after his observations of the style of Indian fighting, and his observations during the French and Indian War, of the weaknesses of the British style.

Since the Raritan Strip along which Howe and Cornwallis eventually chose to advance, was prosperous and Tory, things went pretty well for the British. After two weeks march, they arrived in Trenton around December 20. In this triumph, the British failed to appreciate the significance of several things, however. Washington was hurriedly summoning six little colonial armies of five hundred to a thousand men each, to join him now that the intentions of the enemy were clear. Furthermore, the Whigs or rebels of New Jersey were aroused in the Pine Barrens of the South and the hills of the North; New Jersey was not nearly as Tory as it seemed during the initial march past the big houses along the Raritan. And, finally, the British and Hessian mercenary soldiers had indeed ravaged the countryside almost as much as the spinsters of the Whig patriot cause shouted out they had. Many neutrals were converted to rebels. The Quaker farmers were particularly upset by the activities of the camp followers, who pillaged curtains and other things not normally attractive to marauding soldiers. And the sharpshooters, both loyalist, and rebel were close enough to their own homes to dispose of another booty. It was a cakewalk down to Trenton, but it was not going to be the same coming back.

|

| Washington |

Washington was getting ready to defend the Capital in Philadelphia, and the wide Delaware river was the best place to do it. When Howe and Cornwallis reached Trenton, they found no boats available on the New Jersey side for miles up and down the river, artillery was planted in strategic places on the Pennsylvania side, ice was beginning to form on the river, it was cold, the December days were short. To them, Washington posed no particular military problem with his naked ragamuffins. Howe had some lady friends in New York, while Cornwallis was planning to spend a month in London before the spring military season. So the British generals made an overconfident miscalculation, and posted their troops in winter quarters, strung out in outposts from Perth Amboy to Trenton and down to Bordentown. A thousand Hessians were quartered in Trenton. By December 20th, it looked like a peaceful but boring Winter lay ahead.

REFERENCES

| Stories of New Jersey: Frank R. Stockton: ISBN-13: 978-0813503691 | Amazon |

Why Did Admiral Howe Choose the Chesapeake?

|

| Philadelphia Airport |

A passenger on a plane approaching a landing at Philadelphia Airport from the south can see long stretches of straight highway along the banks of the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. To drive on that highway (I-495) takes twenty or so minutes at sixty miles an hour. The thought occurs that this would have made an excellent place for Admiral Howe to land his brother's troops, well below the narrow mud flats which made Fort Mifflin so formidable, but considerably closer to his Philadelphia objective than Elkton, Maryland where he actually did land. Why would he sail all the way to Norfolk and back up the Chesapeake when a shorter Delaware trip would provide less time for Washington to prepare a defense? The long confinement of the British horses aboard ship proved to create great difficulties, which essentially undermined his plan to disembark the troops without waiting for baggage and supplies and ride into a surprised and undefended Philadelphia. And, although hurricanes were poorly understood at the time, the extra three weeks pushed the British timetable into a September landing, where they did encounter two huge storms which were probably fall hurricanes. Why did he do this when a shorter voyage seemed available?

|

| Perth Amboy NJ |

Admiral Howe was notoriously secretive about his plans. He embarked at Perth Amboy without telling a single subordinate (or superior, either) what his destination was, and did not issue orders to his helmsmen until the fleet was out of sight of land. He wanted to surprise Washington, and he trusted no one. History will, therefore, have to guess what his thinking was. The question was posed to William Dorsey, a retired river pilot, a former member of the Delaware Board of Pilot Commissioners, and historian of the port. The answer was readily given: navigation of Delaware Bay was too tricky.

Whether or not they harbored rebellious sentiments against the British, or were merely protecting the livelihoods of colonial river pilots, the Board of Port Wardens was tightly protective of the charts and lore of the Bay. One Joshua Fisher had prepared what were recognized to be the most reliable charts of the snags and shallows and was willing to sell them. The Board of Wardens would have none of this, and poor Fisher was ultimately forced to move from Lewes to Philadelphia, where he had a house in what is now Fairmount Park. Furthermore, the Board was very careful to keep Tory sympathizers from becoming Delaware River pilots.

It's never safe to guess other people's motives, and at this distance, they scarcely matter. The plain fact of things is that navigation of a fleet of seven hundred sailboats up a snaggy uncharted river, without any available experienced local pilots, was just too unsafe to attempt. An extra three weeks at sea was a far safer bet.

Battle of the Clouds: September, Remember

|

| Dilworthtown |

Weather satellites, television and so on have taught us much about hurricanes that was unknown in 1777. Benjamin Franklin, it should be noted, was the first to observe that Atlantic Coast "Nor'easters" actually begin in the South and work North, even though the wind seems to be blowing in the opposite way; what's moving toward the northeast is a low-pressure zone. We now know that hurricanes begin in Africa, travel West and then veer North when they reach Florida. A great deal is still to be learned about hurricanes, but the most important thing about their timing is contained in a maritime jingle:

June, too soon.

July, stand by.

And then: September, remember.

October, all over.

Along the Atlantic east coast, the end of August to the middle of September, is hurricane season. That's when houses blow down in Florida, and heavy rains hit Pennsylvania. Admiral Howe might have had some clue to this, since Franklin made his observation around 1750, and storms are important to Admirals. But very likely his brother the General just thought it was one of those things when the British landing at Elkton, Maryland in late August 1777 was greeted with an unusually severe downpour of rain. Howe had planned to surprise Philadelphia from the rear by hitting the ground running on horseback. However, he underestimated the debilitating effect on the horses of three weeks at sea on sailboats; to unload and forage horses during a hurricane was almost too much for the plan. For that purpose, he had given orders for the troops to disembark without waiting to pitch camp, or unpacking their gear. But the drenching rain gave Washington several extra days to organize a defense, although he has been given too little credit for the strenuous accomplishment of moving an army from Bucks County to the banks of the Brandywine in that weather. Howe, whose trademark was surprise, deception, outflanking, had anticipated a sudden cavalry thrust into the backyards of unprepared Philadelphia. What he got was 2000 casualties in the biggest battle of the Revolutionary War, against Washington's well-prepared defense along the steep-sided Brandywine Creek.

Howe won this battle, in the sense that Washington was forced to withdraw, because Howe employed another British military trademark, of driving his own troops beyond humane limits in a huge outflanking movement. The countryside around Kennett Square is hilly and broken almost to West Chester, and the American Army felt reasonably prepared along a front of ten or twelve miles. But Howe drove the main force of his army seventeen miles to the north, to Dillworthtown, before turning the unprepared American right flank. And, in the now hot August weather in full uniform and battle pack, the drive continued for twenty-four consecutive hours until Washington saw he had to withdraw. This was what the British meant when they boasted of seasoned regular troops; you win by enduring more than your opponent can endure.

One has to have equal admiration for Washington. Although he was dislodged from his position, losing the opportunity to catch the British in a hostile region without a reliable source of supplies once the fleet weighed anchor, he preserved his army of marksmen and deer hunters intact during the retreat. The two armies started at roughly the same size, and Washington had only about 1300 casualties; his men had more certain supply sources, and they were fighting for their homes. The British, somewhat outnumbered, had the prospect of fighting their way without resupply through an enemy's home territory, capturing the enemy's capital, but still facing the possibility that the British fleet might not get past the Delaware River defenses. If that happened, they could celebrate their victory by starving to death. Just about the only weakness of the Continental Army was its discomfort with bayonet warfare. They could hit a squirrel at a hundred yards, but those long bayonets on the end of very long muskets were designed to protect foot soldiers from cavalry charges. It takes training to put the butt of the musket against a stone on the ground, hold your ground against an oncoming gallop of horsemen, and trust that at the last moment the horses will rear back and throw the riders. But it also takes naked bravado to wave a sword and ride full tilt into a forest of pointing bayonets, trusting that at the last moment the defenders will break and run.

But Washington knew what he was doing. He pulled the troops back to Chester, then over the Schuylkill to the Germantown encampment at Fox and Queen Lane, then up the Schuylkill to Norristown, the first ford in the river that Howe must use when the boats and bridges were destroyed. The river would hold the British while the Americans came at them from the rear; this was essentially the same river strategy he used at the battle of Trenton. Washington picked his battlefield in Chester County and got ready to fight the second installment of the Battle of Brandywine. The campus of Immaculata University now occupies the site.

And then it rained, again. Hard. The gunpowder on both sides was soaked, useless. In what has come to be known as the "Battle of the Clouds", the fighting was called off by mutual agreement. The second hurricane of the year had arrived, and Washington more or less helplessly had to watch Howe take over Philadelphia unopposed. He lost the capital, provoking dismay among the colonists, but his masterful strategy taught the British to respect him. When the British were later considering whether to hold or abandon Philadelphia, this growing respect for their adversary helped tilt their thinking toward prudence.

But that was not before Howe once more showed he too was not the lazy slacker that others had called him. General "Mad Anthony" Wayne was dispatched with fifteen hundred troops to hassle the rear of Howe's army. Wayne was confident he could hide his troops in the Radnor area where he had been brought up, but the region in fact had many Torys to report his movements. Howe ordered Major General Lord Charles Grey to take the flints from his troops' muskets, attack the American camp near Paoli's tavern in the night, and use only bayonets. Waynes' troops were scattered and slaughtered, in what came to be known as the Paoli massacre.

La Fayette, We Are Here

|

| Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette |

It will be recalled that La Fayette was 19 years old at Valley Forge, spoke no English, had no previous military experience. He nevertheless demanded, and got, a commission as Major General on the prudent condition that he have no troops under his command, at least for a while. Washington had been strongly reminded by various people that this young Frenchman was one of the richest men in France, a personal friend of the Queen, and thus critical to the project of enlisting French assistance in the war. Under the circumstances, it was shrewd to send him on the project of enlisting Indian allies among the Iroquois, since many tribes, particularly the Oneida, spoke French and held their former allies in the French and Indian War in great esteem. The chief of the Oneida Wolf clan (Honyere Tiwahenekarogwen) was visiting General Philip Schuyler in Albany at about the time LaFayette showed up on his mission to get some help for Valley Forge. General Horatio Gates was busy at the time rallying a colonist army to defend against the British under Burgoyne, coming down from Quebec, eventually to collide at the Battle of Saratoga.

Earlier in the war, Honyere's Oneida tribe had tangled with their fellow Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brandt (the Dartmouth graduate who was both biblical scholar and commander of several frontier massacres); the Oneida had many new scores to settle with the English-speaking Iroquois tribes. Honyere made the not unreasonable request that before his warriors went off to war, his new American allies would please build a fortification to protect his women and children from Brandt's Mohawks. LaFayette readily put up the money for this project, quickly becoming the Great French Father of the Oneidas. After some scouting and patrolling for Gates, Honyere and about fifty of his braves followed LaFayette to Valley Forge, where they soon made a nuisance of themselves to the Great White Father George Washington. Finally, word of the official French alliance with the colonists reached London, Howe was replaced by Clinton, and the British began to withdraw from their isolated position at Philadelphia.

It was thus that the jubilant rebels at Valley Forge learned that the fortunes of war had turned in their favor, and the French alliance was the source of it. With the British making preparation to abandon Philadelphia, it seemed a safe thing for Washington to give LaFayette command of two thousand troops, including the fifty Oneida Indians, and post them to Barren Hill (now LaFayette Hill), along Ridge Pike near Plymouth Meeting. Washington gave the strictest orders that they were to take no chances with anything, and particularly were to remain mobile, moving camp every day. This was not exactly what the richest man in France was anticipating, and wouldn't make a very saucy story to tell Marie Antoinette about. So, he promptly set about fortifying Barren Hill. Local Tory spies quickly spread this news to General Clinton, who promptly led eight thousand redcoats up the Ridge Pike to capture the bloody Frog. Clinton's plan was good; a detachment went around LaFayette in the woods and came back down Ridge Pike from the other direction, driving the Americans down the Pike into the open arms of the main body of British troops, coming up Ridge Pike. From this point onward, two entirely different stories have been told.

The more widely-held account has LaFayette climbing the steeple of the local church and noticing that there was an escape path, leading down the hill to the Schuylkill River at Matson's Ford. The Indian scouts were sent forward to hold off the British while the troops made their escape. Clinton sent a cavalry charge of Dragoons forward, yelling and waving their sabers, generally making a terrifying spectacle. The Indian scouts, as was their custom, were lying in the brush shoulder to shoulder, and at command by Honyere rose from the ground to let out a resounding chorus of war whoops. The Indians had never seen a cavalry charge, the Dragoons had never heard a war whoop, so both sides fled the battlefield without doing much damage. Meanwhile, LaFayette and his troops escaped to safety on the far side of the Schuylkill.

Other accounts of this episode relate that when Washington heard of it he remarked sourly that either they were pretty lucky, or else the enemy was pretty sluggish. In any event, a few soldiers were killed on both sides, the Americans crossing the River were described as "kegs bobbing on the pond", and it does seem the British army mostly just watched them do it. In the confusion, of course, everyone involved was fearful of being surrounded by unseen troops, and the British may well have worried the whole thing was a trap.

The saddest postscript to the Battle of Barren Hill is the fate of the Indians. After the war was over in 1783, the colonists busied themselves with taking over Indian land. Honyere pitifully petitioned the New York legislature for some consideration of his tribe's wartime service. They ignored him.

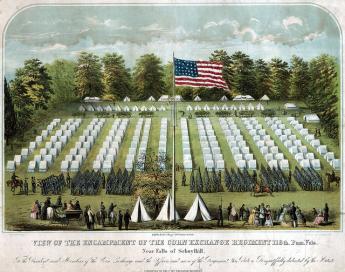

Encampment At East Falls

The urban intersection at Queen Lane and Fox Avenue in East Falls is a busy one, and except for a few stately residences, it easily escapes notice by commuters. However, the landscape forms a bowl atop a steep hill, fairly near the Schuylkill River. George Washington had evidently picked it out as a strong military position near the Capital at Philadelphia, either to defend the city or from which to attack it, as circumstances might dictate.

|

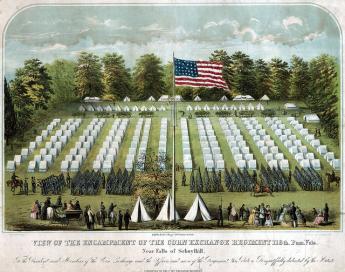

| Encampment at East Falls |

Washington's plans and thought processes are not precisely recorded, but when Lord Howe had sailed south from the Staten Island- New Brunswick area, he ordered his troops to head for an East Falls encampment at the southern edge of Germantown. Crossing the Delaware River at Coryell's Ferry (New Hope), the troops marched inland a few miles and then down the Old York Road to this encampment. Their stay at the beginning of August 1777 was quite brief because Washington changed his mind. When it took Howe's fleet longer than expected to appear in the Chesapeake, Washington became uneasy that Howe might be conducting a feint designed to draw the Continental troops south, and after cruising around the coast, might still return to attack down the undefended New Jersey corridor from Perth Amboy to Trenton. That proved wrong, but in Washington's defense, it must be said it was a plan that had actually been considered by the British. Anyway, Washington ordered his troops to pull out of the East Falls encampment and march back up Old York Road to Coryell's Crossing, which would be a more central place to keep his options open for the time when Howe's true intentions became clear. Washington and his headquarters staff went on ahead of the main body of troops, setting up headquarters at John Moland's House a little beyond Hatboro and a few miles west of Newtown, Buck's County. The Hatboro area was a pocket of Scotch-Irish settlement, without any local Tory sentiment, thus preferable to the rest of largely Quaker Buck's County.

To jump ahead chronologically, the East Falls encampment site must have seemed agreeable to the Continental Army, because a few weeks later it would be sought out as the main refuge and regrouping area, following the defeat at the Battle of Brandywine. The American troops were to withdraw from the Brandywine Creek when Washington realized he had been out-flanked, and head for Chester. Quickly recognizing that Chester was vulnerable, they headed for East Falls. Not only was Washington preparing to defend Philadelphia at that point, but was using the Schuylkill River as a defense barrier. As he had earlier done at the Battle of Trenton, he ordered all boats removed from the riverbanks, and artillery placed at any likely fording places, all the way up the Schuylkill to Norristown. Having accomplished that, this extraordinary guerrilla fighter then moved his troops from Germantown up the river to defend the fords. Meanwhile, Congress decided to move to the town of York on the Susquehanna, just in case.

Wyoming, Fair Wyoming Valley

|

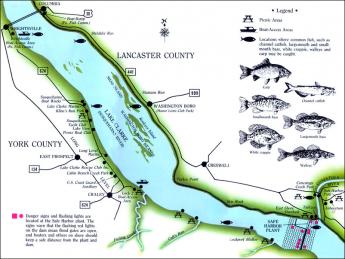

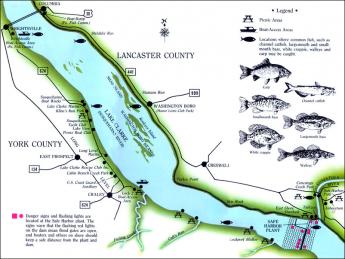

| Lake Clarke |

By 1750, or roughly ninety years after King Charles gave them their charter extending infinitely to the Pacific Ocean, the Connecticut Yankees with Old Testament first names had found their promised land was as disappointing as the King who promised it to them. So, two kings later, an exploratory party was sent west of the Hudson. The party returned with glowing tales of the Wyoming Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, just over the Blue Ridge Mountain. Only one white man had ever been there before them, Count Zinzendorf, the adventurous founder of the Moravian Sect.

|

| Iroquois |

The Wyoming Valley is certainly a jewel. It has comparatively mild weather as a result of being protected on all sides by mountains. The Susquehanna River runs through it, pinched by narrow valleys at both the top and the bottom, and filled with deep rich topsoil. In fact, it constitutes the remains of an ancient lake, whose Southern tip had broken through the Nanticoke Gap, draining the lake. It took another century or so to learn that underneath the topsoil was a thick deposit of anthracite coal. The Connecticut explorers were ecstatic about this little paradise in the mountains, and returned with news that it was everything the real estate promoters (The Susquehanna Company) wanted to hear. Indeed, the promotion of this valley almost got out of hand when news of it reached Europe at the start of the Romantic Period. Wyoming is what everybody wanted to hear about, the home of the noble savage. An epic poet named Thomas Campbell composed a long saga about Gertrude of Wyoming that caught the fancy of the Romanticists, with tales of Gertrude luxuriating on the ocean beaches of Pennsylvania, watching flocks of pink flamingos, and similar fancies, like Gertrude reading Shakespeare in the woods. In 1762 The Susquehanna Company sold six hundred shares to Connecticut adventurers, who were soon off to paradise.

The noble savages turned out to be Iroquois, who watched the new settlers on their land from behind neighboring trees. After a few months it became clear the white settlers intended to stay permanently in the valley, so one day the Indians emerged from the woods, and annihilated them.

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

The Final Capture of Philadelphia (6)

|

| General Howe |

Philadelphia had only 25,000 inhabitants during the Revolutionary War. Now, nearly that many British soldiers of Sir William Howe poured into town, victorious. Victorious, except for being cut off from their supplies on the warships in the Chesapeake. Men war soon sailed up the Delaware River but found the narrow channel between Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer in New Jersey blocked by strange contraptions called chevaux-de-frise. These instruments consisted of heavy timbers sunk to the bottom of the river, containing massive iron prongs that reached almost to the surface but pointing downriver. They were effective blocks to wooden vessels, almost impossible to dislodge. The general arrangement was: Fort Mercer on the top of the New Jersey cliff called Red Bank (now National Park), overlooking the blockaded channel. On the other side of the ship channel, Fort Mifflin on an island. A second channel between Fort Mifflin's island and the Pennsylvania shore was quite shallow, allowing special American gun barges and galleys to come down and attack the larger British vessels, then to escape pursuit by fleeing upstream. The Americans had two years to perfect this defense, and it was formidable. Only one or two large sailing vessels could maneuver near it downriver, and at least the Pennsylvania side was difficult to attack across the mud flats.

When Howe was earlier considering how to attack Philadelphia as he sailed Southward past the mouth of Delaware, he had decided it was hopeless for his fleet to attack this barrier if it was defended by an army, and the strategy evolved to defeat Washington, first. However, in the event, Washington's Army remained essentially intact after the conquest of the city, and from Valley Forge was able to interfere with supplies from the Chesapeake or lower Delaware Bay, but still send reinforcements to the river defense. The communication line on the Westside was essentially what is now the Blue Route, the third side of a triangle, from Conshohocken to Fort Mifflin, containing all of the British troops. The bend in Delaware made two sides of this triangle, and turbulence created by the river bend threw up mud islands which made the channel particularly narrow. These islands have since been filled in for the airport, the stadiums and the Naval yard, so the battleground is today, unfortunately, a little hard to make out, just as is also true of Bunker Hill, North Church, etc. in Boston Harbor.

Four or five hundred Americans were in each of the two forts, and eventually, most of them were wiped out, at least half of them by starvation and exposure as much as cannon and musket fire. They had British on both sides of them, heavy guns bombarding them, under attack for weeks. The British kept at it because to fail meant the loss, by starvation and snipers, of almost the entire British expeditionary force in America. A contingent of Hessians under von Donop was sent to Haddonfield and down the King's Highway to attack Fort Mercer from the rear. In a moment famous in Haddonfield, a champion runner named Jonas Cattell sneaked out of the town and ran to Fort Mercer to tell the troops to turn their guns around for an attack from the rear but lie concealed behind the guns, while meanwhile the Quakers in the little town entertained the Hessians in a very friendly way. There was more to it than that, with some heavy fighting in the open, but von Donop and most of his troops were casualties. The fort had been made smaller in the past, unexpectedly presenting the attackers with a second set of fortifications after they surmounted the outer ones. Later on, a second assault by a different contingent of Hessians did level the Fort. If not, there would have been a third or a fourth assault, because a river passage simply had to be forced to relieve starving Philadelphia. Before the repeated assaults were over, Fort Mifflin had also been bombarded into rubble. But what really carried the day for the British was the late realization that if small Americans boats could sneak down the channel on the Pennsylvania side of Mifflin; then small British boats could go the other way, as well. Although the river blockage was eventually broken, it took six weeks after the battle of Germantown, and meanwhile, the heroic defense did a great deal to rally the sympathies of what had been considered maybe a loyalist city, and partly loyalist Colony of New Jersey. Before the winter was over, Howe had to go back to London to explain himself, being replaced by General Clinton, who was much less clever and much more provocative as a conqueror. The first two years had British control by a minority of hothead aristocrats. For the remaining five years of the war, the sobered British concept was no longer liberation of colonial Tories, but the subjugation of fanatic Rebels. The realization gradually spread, through both England and America, that the war had been lost, since Independence was a more sustainable situation for everyone than continuing endless efforts at subjugation.

Meschianza

|