Related Topics

Philadelphia's River Region

A concentration of articles around the rivers and wetland in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Park and Beyond: East Falls, Germantown, Mt. Airy and Chestnut Hill

Fairmount Park is large enough to split the City from its suburbs, and is partly a playground, partly a museum. East Falls, Germantown and Chestnut Hill are almost a separate world on the far side of the park.

To Germantown, a Short Appreciation

Seven miles from the heart of Philadelphia, Germantown was once a separate town, the cultural center of Germans in America. Revolutionary battles were fought here, it was briefly the capital of the United States, and it still has an outstanding collection of schools and colleges.

The British Attack Philadelphia

Fighting in the Revolutionary War lasted eight years; for two years (June 1776 to June 1778) Philadelphia was the main military objective of the British.

Sights to See: The Outer Ring

There are many interesting places to visit in the exurban ring beyond Philadelphia, linked to the city by history rather than commerce.

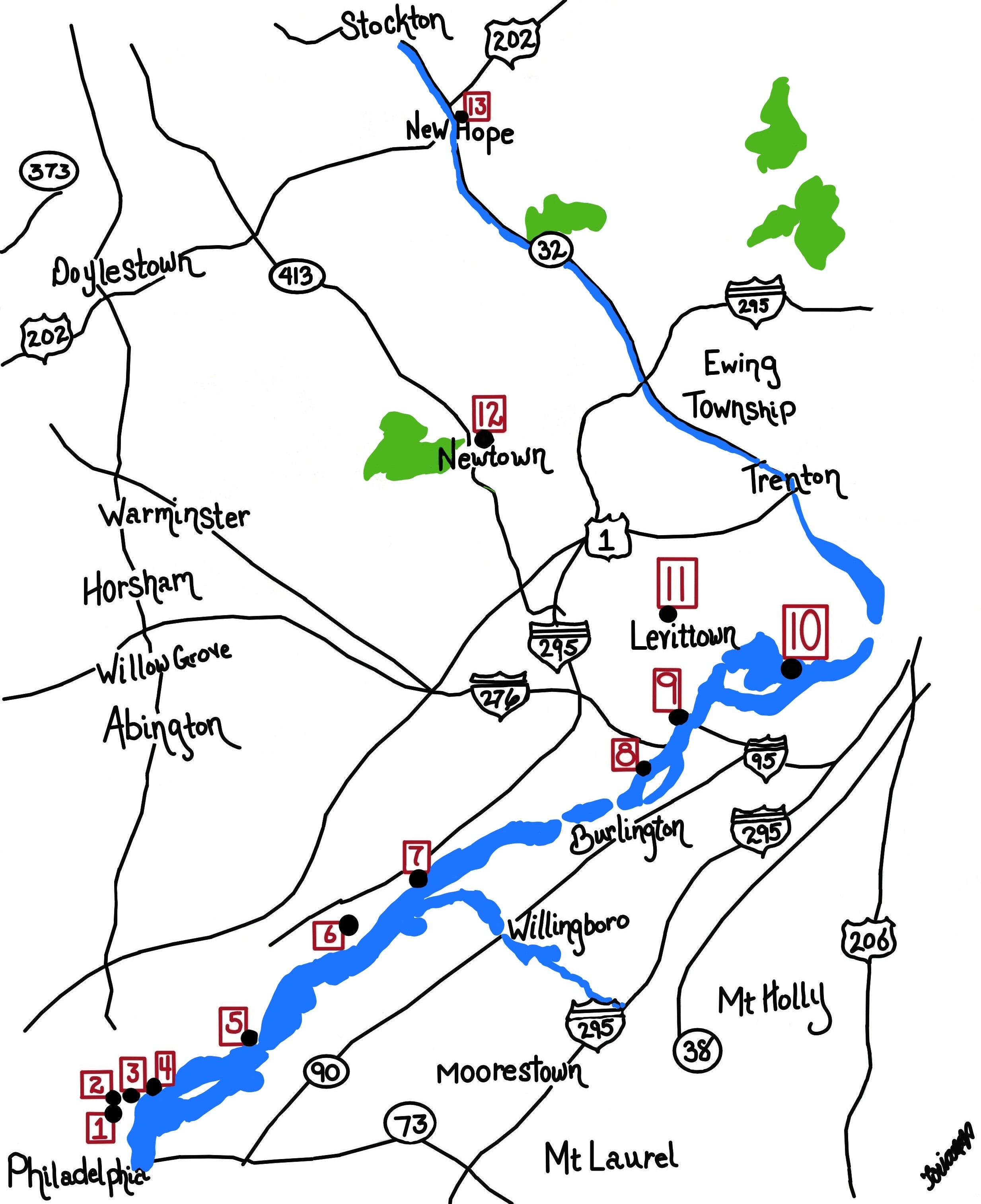

Historical Motor Excursion North of Philadelphia

The narrow waist of New Jersey was the upper border of William Penn's vast land holdings, and the outer edge of Quaker influence. In 1776-77, Lord Howe made this strip the main highway of his attempt to subjugate the Colonies.

Tourist Trips Around Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker. He was the largest private landholder in American history. Using explicit directions, comprehensive touring of the Quaker Colonies takes seven full days. Local residents would need a couple dozen one-day trips to get up to speed.

Pacifist Pennsylvania, Invaded Many Times

Pennsylvania was founded as a pacifist utopia, and currently regards itself as protected by vast oceans. But Pennsylvania has been seriously invaded at least six times.

George Washington in Philadelphia

Philadelphia remains slightly miffed that Washington was so enthusiastic about moving the nation's capital next to his home on the Potomac. The fact remains that the era of Washington's eminence was Philadelphia's era; for thirty years Washington and Philadelphia dominated affairs.

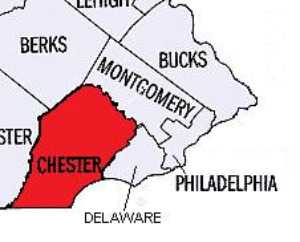

Chester County, Pennsylvania

Chester was an original county of Pennsylvania, one of the largest until Dauphin, Lancaster and Delaware counties were split off. Because the boundaries mainly did not follow rivers or other natural dividers, translating verbal boundaries into actual lines was highly contentious.

Chester was an original county of Pennsylvania, one of the largest until Dauphin, Lancaster and Delaware counties were split off. Because the boundaries mainly did not follow rivers or other natural dividers, translating verbal boundaries into actual lines was highly contentious.

Right Angle Club 2011

As long as there is anything to say about Philadelphia, the Right Angle Club will search it out, and say it.

City Hall to Chestnut Hill

There are lots of ways to go from City Hall to Chestnut Hill, including the train from Suburban Station, or from 11th and Market. This tour imagines your driving your car out the Ben Franklin Parkway to Kelly Drive, and then up the Wissahickon.

Fort Washington, PA

|

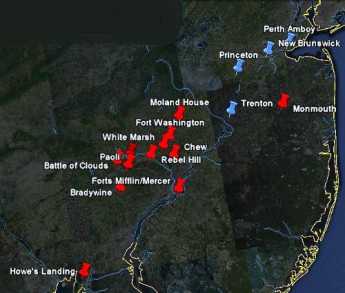

| British Campaigns |

The Revolutionary War lasted eight years, so there are a half dozen Fort Washingtons, in several states. Pennsylvania's Fort Washington gets free advertising from being a stop on the Pennsylvania Turnpike at the intersection of the East-West branch and the North-South branch, near some very large shopping malls. Nevertheless, the suburbs haven't reached it yet, and it is on a series of wooded mountain ridges discouraging housing development. Another way of describing its location is that it is several miles north of Chestnut Hill along the Bethlehem Pike, a road which begins in the center of Chestnut Hill at Germantown Avenue. The Pike is quite old, with many surviving colonial-era houses and inns to liven up the trip.

A third way to describe Fort Washington is that the headquarters were at the point where Bethlehem Pike crosses the Wissahickon Creek. How's that again? How does the western Wissahickon Creek then flow uphill to Chestnut Hill? Of course, it doesn't, but the appearance takes some explaining. The northwestern end of Philadelphia is reached by two ancient roads running on ridges quite close together like the split tail of a fish. Germantown Avenue runs up one ridge, and Ridge Avenue runs up the second ridge closer to the Schuylkill. The Wissahickon runs in the gully between these two ridges and tumbles down the hill at Wissahickon Avenue, or Rittenhousetown if that is more understandable. The ridge of Ridge Avenue is essentially cut off by the creek, but engineers have put Ridge Avenue on a high arching bridge as it crosses the creek far below, and by this magic Ridge Avenue and Germantown Avenue are at about the same height most of the way. The Wissahickon Creek is really running downhill the whole way, but sort of disappears from sight and reappears as it twists through the gorges, misleading the casual visitor (or commuter). As happened so often during the Revolutionary War, Washington showed his understanding here of geography in the service of guerrilla warfare.

Since the British were headquartered in Germantown, and the Americans have camped a few miles away on the same creek, it was inevitable there would be some sort of battle in the region. Washington launched a three-pronged attack on the British soon after arriving at Fort Washington, but his troops fired at each other in the fog, and apparently, two prongs more or less got lost in the gorges. The Americans retreated, and the British consolidated their conquest of Philadelphia. They did launch one surprise attack on the American encampment (the Battle of Whitemarsh), but that was mainly a reconnoiter, given up after a few days when it became clear Washington's troops held the high ground. It really is high ground (hawk-watching platforms and all) for reasons already stated. Chestnut Hill is a pinnacle sticking up on the west side of the Creek, with the Wissahickon snaking around its base.

This really was a perfect place for Washington to aim for after the Brandywine Battle, close enough to threaten the British, located in a bowl-like valley for camping, but terminating at the top of a mountain ridge in case the British counter-attacked. And with plenty of running water from the Wissahickon. However, it was a little too close for comfort, and he withdrew across the Schuylkill into Valley Forge as a more substantial natural fortress. Valley Forge is also on a hilltop, but one sitting in the middle of the Great Valley (Route 202 to Wilmington), as the center of an angel food cake tin. No doubt, the advantages of this new location became evident to him at the earlier skirmishes of the Battle of the Clouds, and the Paoli Massacre, which occurred nearby.

In retrospect, these maneuvers and skirmishes were of little military significance, except for the major Battle of Brandywine. The lost opportunity was the chance to catch the British Army without supplies or access to the Navy, aborted by what was probably a hurricane, the so-called Battle of the Clouds. Philadelphia was lost, and the opportunity to win the war early by smashing a third British army was gone for good. The defeat of the Hessians at Trenton, the loss of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga, and a victory on the outskirts of Philadelphia might together just have finished the War. But things didn't work out, the British similarly missed some opportunities, and the war was to last another five years. Once the French allied themselves, their wealth and naval strength tended to make French priorities dominate strategy.

Nevertheless, a perfectly splendid tourist trip awaits the history buff who travels from Elkton, Maryland, where the British landed, to the Battle of Brandywine battlefield, up the Great Valley to Immaculata University where the Battle of the Clouds took place, over to the Battlefield of the Paoli Massacre, crossing the Schuylkill and going to Whitemarsh, then to Fort Washington, and back up Bethlehem Pike to Germantown Avenue, and down to the Chew Mansion. The campaign for the conquest of Philadelphia ended with the fall of Ft. Mifflin when the British fleet was finally able to re-supply Howe's army. This direct auto tour is a little out of chronological sequence, but it can be done in one day if you don't dawdle. If you slow down and spend an extra day, you can include the Moland House where Washington waited to see where General Howe was going. At the right season, there's hawk watching on the ridge at Fort Washington Park, and maybe on to Trenton, or even up the New Jersey waist to Perth Amboy on lower New York Bay, where the Howe brothers began and ended their Philadelphia adventure. That would take you past Princeton and New Brunswick, or even include a trip to the Monmouth Battleground. With this extension, you have traveled much of the extent of the Revolutionary War in the Mid-Atlantic states.

Originally published: Monday, March 21, 2011; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 08, 2019