3 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

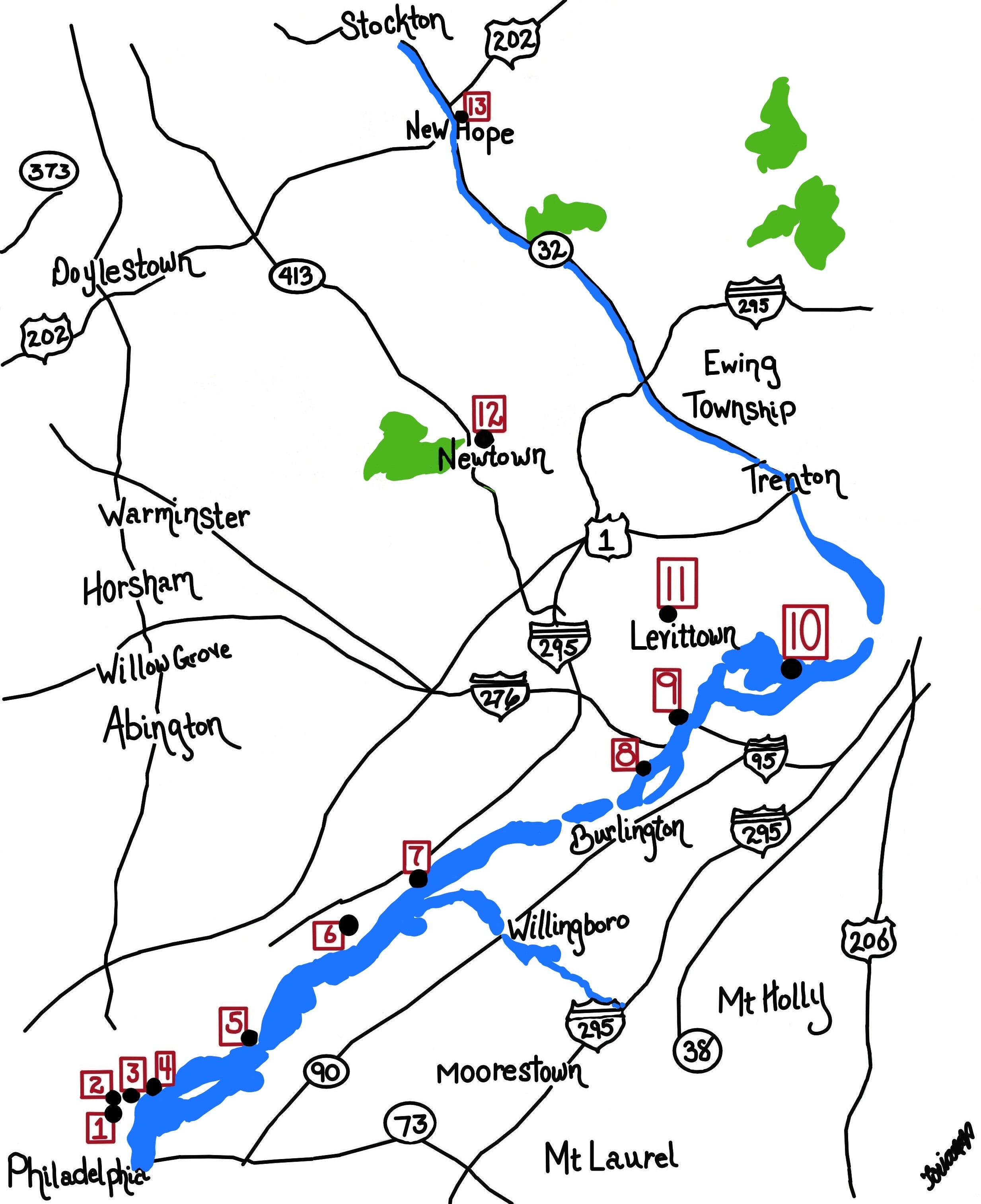

Philadelphia's River Region

A concentration of articles around the rivers and wetland in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Gunk, 27 Million Tons of It

|

| Henry Hudson |

When Henry Hudson reached the mouth of Delaware Bay in 1609, the river was so full of snags he simply went up to what is now the Hudson River in New York rather than try to wiggle his little sailboat up Delaware. By 1900, there had been enough dredging and removal of islands that the channel was 17 feet deep all of the ninety miles up to Philadelphia. One of the consequences was that the new river edge was down at Delaware (Columbus) Avenue, rather than up at Front Street. When you make it deeper, the width of a shallow river often narrows.

Now, the proposal is to deepen the channel to 42 feet, a number mandated by the present size of cargo container ships. Another limiting factor is the construction of the bridges, so the Port of Philadelphia is moving South of the Walt Whitman bridge. That's potentially of great value to the longshoremen who live in that region, although whether it will really bring prosperity is up to them, depending on whether they restrain their aggressive wage and work-rule proposals. There are serious students of the Philadelphia economy who maintain that the economic decline of Philadelphia is more traceable to the intransigence of the longshore unions than to any other factor. Since that comment is specifically made in comparison with the railroad brotherhoods, it is a dramatic accusation indeed.

If you deepen the channel to 42 feet, 800 feet wide (1300 feet at bends in the river), you can be calculated to bring up 27 million tons of sludge. You have to dump that stuff somewhere else, and the current plan is for Philadelphia to build a retaining wall out into the river next to the Packer Avenue terminal area, and dump Philadelphia's share of the stuff behind it. In time, the water will drain out of the gunk, and quite a few acres of dry land would make its appearance. Some engineers question whether the force of the river would permit this. Environmentalists have objections to this project relating to stirring up pollutants lying dormant on the river floor, but without likely effect on the tin ears of those who are presently congratulating themselves on obtaining Federal money to accomplish this "big dig".

The really serious obstructions are coming from the State of New Jersey, which would acquire 9 million tons of gunk as their fair share. Right now, New Jersey is raising taxes and cutting state spending because of a budget deficit, so they are not anxious to take on another big project, particularly one whose benefits will have to be shared with Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania was momentarily sympathetic with this problem until it was learned that New Jersey is actively promoting a FIFTY-foot channel in the Hudson River. Immediately it becomes obvious that there is not enough money for two projects, and there are more New Jersey voters up near the port of New York than down around the Port of Philadelphia. Both New Jersey and Pennsylvania have Democrat governors, while New York has a Republican one. Ordinarily, this would be a decisive point, but the preponderant location of voters up in North Jersey seems to trump that. Keep watching the Saturday papers, on the editorial page down below the fold, the place newspapers ordinarily reserve for retractions, apologies, and local political truths.

What's going on here is attempted exploitation of geographical advantages. Philadelphia is at one of three navigable openings in the Atlantic coast barrier islands adjoining the New York-Washington megalopolis, or five openings if you call it a Boston-Richmond megopolis. Obviously, a seaway opening in the middle is superior to one at the ends, so it really comes down to a New York and Philadelphia competition, with Baltimore a poor third because European ships have to go down to Norfolk and then come come back up the Chesapeake, like Lord Admiral Howe in 1777. There's a huge amount of rail and truck traffic North and South, so crossing the T with ocean traffic arriving in the middle could make quite an economic center. Passenger rail traffic from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh and beyond is pretty anemic, but freight traffic is healthy and could be more so with cargo supplied by container ships. This is the dream, New York is the enemy, New Jersey is the villain, and the longshoremen are the main beneficiary. It is even possible to imagine eighty dollars per hundred in wages for Workman's compensation, but that would be cynical.

Because of the New Jersey problem, proposals have been made to fill up abandoned coal mines with dredging sludge and let the water seep out wherever it, please. Somehow, this isn't thought to be practical, and other suggestions seem to be very welcome, a rather unusual circumstance in itself.

Let's ask ourselves whether we want to return Philadelphia to its old industrial mightiness, or whether we want to encourage the development of a service economy, computers and all that. One way to measure success in the container cargo race is to count the unloading cranes. Philadelphia has about five of them, and most of the time they are sticking straight up, unused. There are many times that many in Seattle, and in Yokohama, there are over a hundred. The port of Kobe has far more, too many to count as you go past on the bullet train. However, there's a secret truth about container ships. When they get to Seattle, there is no cargo to fill them with for a return voyage, and in fact, the empty container pile-up is a rather serious problem. Bill Gates is shipping lots of software to Japan, but it doesn't fill cargo containers, and the economy of the region is going to have high transportation costs until someone figures out a bulk cargo product to ship from Seattle. This is exactly the situation of a century ago when the New York Central, the Baltimore and Ohio, and the Pennsylvania RR were battling it out for transcontinental supremacy. The Pennsy won that battle because oil was discovered in Bradford Pennsylvania, and refineries were built on the Schuylkill to process the oil. The Pennsy had thus found a round-trip cargo for filling its empty East-bound freight cars, and it beat out the other two railroads which didn't. Cheaper freight rates became possible, and therefore other industries prospered in the region.

Right here is a topic which somebody at the Wharton School had better start talking about. No matter how much software and other service industry prosperity a city region may support, it has to find a way to supply bulk cargo to all those container ships that are bringing in the BMW's for the service industry hotshots to drive.

Meanwhile, what does New Jersey do with 9 million tons of gunk?

The Swamps of Philadelphia

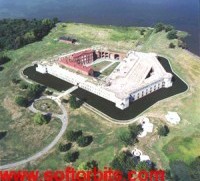

|

| Fort Mifflin |

Fort Mifflin has been restored, somewhat, and gets a surprising number of visitors at Hallowe'en. The explanation offered is that it seems somewhat spooky. A far greater number of people go to Philadelphia International Airport, or the several sports stadia constructed nearby in a project whose financing is described as "borrowing to expand the tax base". In so doing, visitors travel at some height above the edge of the now-closed Philadelphia Naval Base, with a large number of very large naval vessels in storage, the so-called Mothball Fleet. All visitors are naturally impressed with a view of the wide expanse of the deep and impressive Delaware River. How could such a mighty river be the site of mud islands and narrow channels so shallow that British sailboats couldn't navigate past the Friesian Horses sunk on the bottom?

Well, as water spreads out, it gets shallower. Conversely, as water is compressed into narrower channels, the channel gets deeper, eventually deep enough for nuclear aircraft carriers. So, think back to the days when the Dutch sailed around here, finding the first solid land along the Schuylkill at Gray's Landing, opposite where the University of Pennsylvania now has a row of medical skyscrapers on the West Bank. Everything South of that point was once swamp, so there were miles and miles of shallow water before you got to the Delaware; you could sort of say that the Delaware River was five miles wide at that point. Lots of fish, and ducks, muskrats and beaver.

The main highway to the South, the one that Washington and Jefferson traveled regularly, ran near Gray's Landing, along the edge of the great Philadelphia swamp. Later on, the railroads were built along the same path, and the industrial devastation of that area was accelerated immediately. It was a natural place for "landfill", which is to say it was a good place to dump garbage. By 1940, you had to drive for miles through garbage dumps to reach the Municipal Stadium, where the Army-Navy football game, attended by 105,000 spectators, was played in the freezing winds. The Naval Yard had been moved from the foot of Federal Street to a filled-in island near Fort Mifflin and provided a railroad spur on which the President of the United States regularly parked his private railroad car as he attended The Game. Some enormous liquor distilleries were built near the garbage dumps, and it was difficult to prove which was responsible for the greater odor. World War II caused a great proliferation of war industries on the banks of the river to the South, and the gasoline refineries in the area added to the aroma and river pollution.

In time, the garbage dumps were covered with dirt, and thousands of houses were built where the mosquitoes used to swarm. When the wartime river traffic declined, unemployment set in, and housing got cheaper, even abandoned. With abandoned housing comes slums, and there, in a nutshell, you have South Philadelphia, waiting for an industrial revival. Meanwhile, the swamps are mostly gone, and the river is a lot deeper.

Draining Suburbia

|

| Creek |

Philadelphia's triangle of land between two large rivers once was laced with streams, brooks, and creeks. These were great places to catch fish, especially trout, and they had what poets call mossy banks. Nowadays, these streams are enclosed in culverts or their exposed banks are sharp cliffs of clay. Few people have heard of Indian Brook, which was once the brook that ran through town but is now the brook underneath Overbrook.

The Conservancy has given thoughtful consideration to the consequences of building hard surfaces on top of what was once spongy soil. The streets, the roofs, the driveways of progress, of development, cause immediate runoff of water after a rainstorm instead of allowing seepage into the soil and gravel of the wilderness. The rain of a storm quickly surges into the storm sewers, and surges into the neighboring creeks, scouring the banks in a flood surge. The grass slopes cannot withstand such a housing, leading to sharp clay banks, which become undermined by later storms, toppling trees. The clay material from the banks makes the streams muddy, and the deposits of clay suffocate the insect larvae and fish eggs on the stream bottom. It's perhaps true that there are fewer mosquitoes, but there are no fish. The matter is compounded by the heating of the water as it drains over large sunlit surfaces like shopping mall parking lots, and the different water temperature in the streams changes the insect and fish content, too.

It's almost hopeless to do anything useful in the downtown city areas, where the former streams are not only enclosed in pipes but run underneath skyscrapers. There may even be too much disruption involved to contemplate doing anything useful in towns which allowed storm sewage and sanitary sewage to flow in the same pipes. But it would be a comparatively simple thing to divert rainwater into gravel driveways or out over lawn areas since the goal is to slow its flow into the streams rather than dispose of it. Local ordinances could require such forethought for new construction, and perhaps make construction permits conditional on it. Many suburban homeowners would probably follow suit voluntarily, and gradually the situation might come under control with education and minor pain.

There are other approaches that would get results quicker. In present China, "infrastructure" is upgraded much more directly. One recent visitor was discussing the problem of construction in an area where there was a Chinese town. He was told not to worry about it. The next time he visited the area, that town would be gone.

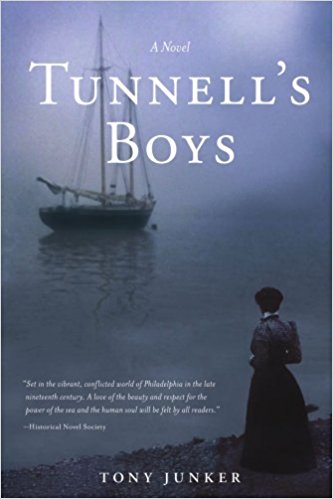

Tony Junker: Tunnell's Boys

|

| Henry Hudson |

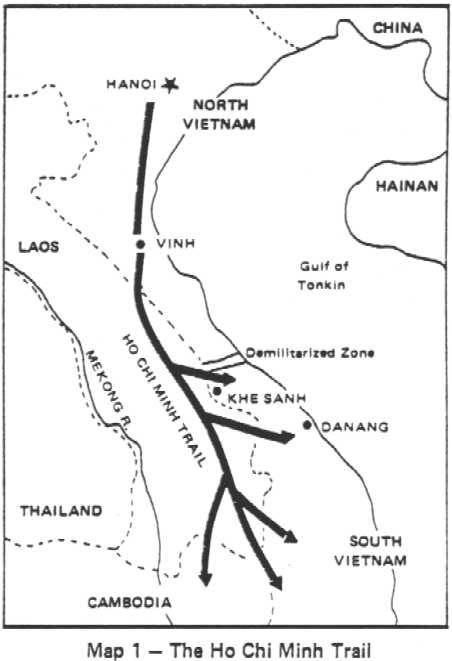

When you take the ferry across the mouth of Delaware Bay from Lewes to Cape May, you are out of sight of land for half an hour. But the Army Corps of Engineers have thoroughly dredged it out. By contrast, when Henry Hudson first discovered the river while searching for a Northwest passage to the Indies, it was so full of snags and shoals that he just gave up and sailed on to what is now New York harbor. So, for centuries the river pilots were an essential part of ocean commerce to Philadelphia. As you might well imagine, the earliest pilots were members of local Indian tribes. Eventually, a proud colony of professional pilots grew up at Lewes, Delaware. Since radio communication is a comparatively recent development in this ancient trade, they had to devise ways for an incoming ship to select a pilot, and establish rules to be enforced by the Port Wardens about how to go about it.

|

In the mid-Eighteenth Century, the system was to hang a black ball from the Cape Henlopen lighthouse whenever a ship was sighted. Little companies of ten or fifteen pilots would then jump into very fast schooners designed for the purpose, and race to be first out to the ladder hanging from the incoming ship's side. The rule was, the first to arrive and present his certificate got the job. Tony Junker, an actively practicing Philadelphia architect has immersed himself in tales and adventures among the pilots, and Tunnell's Boys is an exciting new novel about this dangerous, wet and uncomfortable, profession.

Pennsbury Manor

|

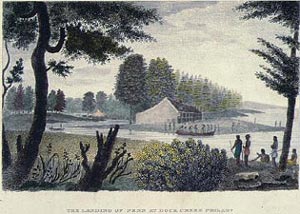

| Fairmount |

William Penn once had his pick of the best home sites in three states, because of course he more or less owned all three (states, that is). Aside from Philadelphia townhouses, he first picked Faire Mount, where the Philadelphia Art Museum now stands. For some reason, he gave up that idea and built Pennsbury, his country estate, across the river from what is now Trenton. It's in the crook of a sharp bend in the river but is rather puzzlingly surrounded by what most of us would call swamps. The estate has been elegantly restored and is visited by hosts of visitors, sometimes two thousand in a day. On other days it is deserted, so it's worth telephoning in advance to plan a trip.

|

| Gasified Garbage |

After World War II, a giant steel plant was placed nearby in Morrisville, thriving on shiploads of iron ore from Labrador, but now closed. Morrisville had a brief flurry of prosperity, now seemingly lost forever. However, as you drive through the area you can see huge recycling and waste disposal plants, and you can tell from the verdant soil heaps that the recycled waste is filling in the swamps. It doesn't take much imagination to foresee swamps turning into lakes surrounded by lawns, on top of which will be many exurban houses. How much of this will be planned communities and how much simply sold off to local developers, surely depends on the decisions of some remote corporate Board of Directors.

However, it's intriguing to imagine the dreams of best-case planners. Radiating from Pennsbury, there are two strips of charming waterfront extending for miles, north to Washingtons Crossing, and West to Bristol. If you arrange for a dozen lakes in the middle of this promontory, surround them with lawns nurtured by recycled waste, you could imagine a resort community, a new city, an upscale exurban paradise, or all three combined. It's sad to think that whether this happens here or on the comparable New Jersey side of the river depends on state taxes. Inevitably, that means that lobbying and corruption will rule the day and the pace of progress.

Meanwhile, take a trip from Washingtons Crossing to Bristol, by way of Pennsbury. It can be done in an hour, plus an extra hour or so to tour Penn's mansion if the school kids aren't there. Add a tour of Bristol to make it a morning, and some tours of the remaining riverbank mansions, to make a day of it.

Port of Philadelphia

|

| Ports of Philadelphia |

When federal appropriations are doled out, it is a great advantage for the Port of Philadelphia to appeal to six U.S. Senators. However, the overlapping control of port operations can come close to paralysis. In short, we may have less chance of agreement on what we want -- but a greater chance of getting it. Right now, the ports of the world are struggling to adjust to revolutions of containerized cargo and gigantic oil tankers, plus political pressure from concern about the environment.

Some of the main arenas of our gladiator fights are as follows:

DRPA: The Delaware River Port Authority operates several large bridges, the PATCO high-speed subway line, and the cruise terminal, all leading to control of potentially large sources of revenue. The 1992 Congress expanded its charter to include the economic development of the port region.

SJPC: The South Jersey Port Corporation owns two marine terminals in Camden, and is planning a third in Paulsboro.

DSPC: The Delaware State Port Corporation operates the Port of Wilmington, DE.

PRPA: The Philadelphia Regional Port Authority has little to do with city politics, but is an arm of the state government of Pennsylvania, operating 7 marine cargo facilities, and planning more.

In addition, every county, city, and town along the riverbank has some degree of authority. Every business and union involved in regional or international trade is desperate to protect its interest in the politics of port regulation. Lately, the Homeland Security Agency has taken a large role. Scientists, engineers, fishermen, oil refinery operators, economists, and others abound. The news media convey their own opinions and the opinions of others. Opinions abound because most issues about ports are important.

In addition to the traditional cargoes of coal, petroleum, iron ore and forest products, which are mostly declining in importance, the rising cargoes include meat, cocoa beans, and South American fruit. General, or casual, cargo tends to be more valuable than bulk cargo, but greatly complicates the Homeland Security risks. The ratio of imports to exports is important because it is expensive to have a ship return empty. Shippers will, therefore, favor a port where there are expectations of return cargo. Oil tankers are particularly likely to return empty since their ballast is mostly river water; but, who knows, perhaps global warming will make dirty river water seem valuable to some tropical oil producer. A quirky problem is that most of the crude oil entering East Coast ports are currently coming from Nigeria, a notoriously corrupt nation. This has led to a thriving business of car-jacking in the Philadelphia suburbs, with the stolen cars promptly packed in empty containers returning to Africa.

Of the 360 major American ports, the Delaware River ranks second in total tonnage shipped, and eighth in the dollar value of the cargo. Every year, 2600 ships call into our port, which claims to employ 75,000 people. According to Bill McLaughlin of the PRPA, the future of the port will depend on the settlement of three major disputes:

1. Deepening the Channel. The historical natural level of the river is 17 feet, artificially deepened to 40 feet up to the level of the Walt Whitman Bridge. It sludges up by two or three feet every few years, so dredging is a continuous issue. The enlargement of tankers and container ships has led to a need to deepen the channel to 45 feet. It is true that the Wissahickon schist pokes up at Marcus Hook and will have to be blasted out, but mainly the issue is dredging up the gunk on the river bottom, and hauling it away somewhere. In Delaware Bay below Pea Patch Island, the bottom is sandy and hence valuable. The State of Delaware has plans for riverfront development, and would actually like to have the 8 million tons of sand, so no problem. The 7 million tons of clay and silt which must be dredged out of the upper Delaware River channel for a 45-foot depth is more of a problem, but users can be found for most of it. Or so the Pennsylvania representatives maintain; the New Jersey representatives led by Congressman Rob Andrews say it would be an environmental disaster to dump a thimbleful on New Jersey. Feelings get pretty hot in these things. The Haddonfield representative is portrayed as selling out his district in order to further his own state-wide aspirations, acting on the orders of North Jersey politicians who dominate New Jersey politics, who want to lessen competition with the Port of New York, which also shares a border with New Jersey. Feelings are not soothed to see the Port of New York deepening its channel to fifty feet while resisting forty-five in the Delaware port.

The document currently at the center of this interstate dispute is called PCA, the Project Cooperation Agreement. New Jersey won't agree to sign the proposal, which contains clauses to remove the DRPA from authority and replace it with PRPA(essentially transferring control and revenues from Philadelphia to the State of Pennsylvania) as the "non-federal sponsor". PRPA would then enter into a contract with the Army Corps of Engineers to get the work done.The price, probably low-balled, is $219 million, to be compared with the Port of New York's dredging price (probably high-balled) of $50 billion. There are, of course, a great many features of this political negotiation which are unlikely to appear in print.

2. Southport. The grand plan for the Philadelphia Port is to center on an intermodal complex of piers, railroads, and highways which would extend as a continuous terminal from the Walt Whitman Bridge to the old Naval Yard. No doubt this idea is linked to the round-the-world concept of Philadelphia as a way station from India to Vancouver, overcoming the empty return cargo problem by never looking back. Good luck.

3. Monetizing the Port. Like the turnpikes, ports could be sold to private investors. Of course, that could extend to selling the property to foreign investors, triggering the nationalist reaction readily observed when port management was once offered to Abu Dahbi. It could well give a new meaning to the expression, being sold down the river, but who knows maybe it's a good idea. When you criticize motives it never bothers real political pros, because it's simple to say you don't have such motives, and who knows. But the people seriously involved in government finances say they most fear that the do-gooders will be allowed to sell or lease publicly-owned facilities to improve the financial balance sheet. And then the pros will just take the money and use it to pay interest on more borrowing.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1337.htm

New Jersey Ponders a Rising Sea Level

|

| Future House Styles? |

A certain gentleman in a professional position to dominate conversations about rising sea levels, is afraid of being sued and requests his name be withheld from the following. Let's just call it hearsay, suitable only for conversational banter.

If the icecap now sitting atop Greenland should melt, it can rather easily be calculated that sea level would rise to the point where the Delaware River would be 83 feet deep. The Army Corps of Engineers would then probably have more urgent matters to attend to, but at least they would no longer have to cope with deepening the channel to 40 feet. If the Antarctic ice cap should then melt on top of it, the sea level would rise an additional 220 feet, resulting in a Delaware River 300 feet deep. There might be some dry real estate on top of Blue Mountain, but not much else on the Atlantic seaboard would be dry, so there would likely be the additional problem of keeping other people from climbing up to sit in your perch. Perhaps the Hawks would bring you something to eat.

A more immediate issue relates to the barrier islands. It is thought the crumbling of mountains into the sea accounts for the sandy beaches of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts; the more recent mountains along the West coast have not progressed to the point of piling up enough sand to start the process. The cycle of barrier islands is as follows.

Barrier islands, if left undisturbed, will gradually migrate toward the land mass behind them, filling up the intervening bay, and eventually adding to the mainland. But that's not the end of the cycle, because the continuous wave and tidal action will generate a new barrier island further out to sea. When the new island reaches a critical equilibrium with the waves and storms, it begins the cycle of deterioration all over again. Presumably, the sandy lowlands of southern New Jersey, the Delmarva Peninsula, and most of Florida are the result of many cycles of barrier islands adding themselves to the mainland. Presumably, the process will run out of sand someday, but not soon enough to worry about.

When affluent people build showplaces on the barrier islands, a great deal of concrete is laid on the island surface for roadways and parking lots, as well as jetties and other desperate efforts to prevent erosion from destroying the beaches, beachfront property, and real estate values. This process is much more active and rapid than most sunbathers seem to imagine. There are channel markers and monuments of the 18th century that are a mile or more out to sea in the 21st century. Almost a mile of beachfront has disappeared at Cape May and Cape Henlopen in Delaware. Lots of other real estate has been swallowed, but records of historical markers at the mouth of the bay have been more diligently maintained. The residents demand that sand be dredged and dumped on their beaches to keep even with the destructive forces at work. All of this ultimately useless resistance to Nature costs a great deal of money. Those who observe the contest between the protests of King Canute and the resistance of other New Jersey taxpayers to rising taxes estimate that around 2040 the cost of interrupting the barrier island cycle will become so burdensome that taxpayers will successfully put a stop to resisting natural beach erosion. The political uproar will surely be horrendous, so there is a good reason for oceanographers to avoid going public with these inconvenient truths. And all of this doomsday talk, by the way, ignores the issue of global warming, which will surely make it all the worse.

Hidden River

.jpg)

|

| Schuylkill River |

In Dutch, Schuylkill means "hidden river", thus making it redundant to speak of the Schuylkill River. As soon as you become aware of this little factoid, you start to come across Philadelphians who do indeed speak of the Schuylkill in a way that acknowledges the origin of the term. To give it emphasis, it is common to speak of the "Skookle". The point comes up because cruises have started to leave from the dock at 24th and Walnut Streets, where it becomes quite noticeable that the Schuylkill really is rather hidden as it winds seven miles south to the airport, in contrast to the wide-open vista we all are accustomed to seeing from the Art Museum northwards.

The bluff at Gray's Ferry, where the University of Pennsylvania's new buildings now dominate the scene, was originally the beginning of dry land, or the end of the rather large swamp, through which the river winds its way essentially shaded by trees along the riverbank. Never mind the junkyards and auto parks you happen to know lurk behind the trees on the west side or the oil tanks which loom above the trees on the south bank. As evening closed in on the riverboat, the gaily lit towers of center city were looming in the stern, but some fishermen along the bank proudly held up a respectable string of six or seven rather large catfish. If you are there in the evening, the river has the same feeling of wilderness that the Dutch traders would have experienced three hundred years earlier. No swans, however. There were many reports in the Seventeenth Century of large flocks of swans sailing around the entrance of the Schuylkill into the Delaware River. A noted local ornithologist on the recent cruise remarked that forty or fifty species of birds are found there. Even a flock of owls still live within the city limits. You don't see owls, even if you are an ornithologist; their presence is made known by taking recordings of the sounds of the night.

|

| Fort Mifflin |

The geography of swampy South Philadelphia was created by the abrupt bend in the Delaware River at what is now thought of like the airport region. As the river flows at the bend, sediment is deposited in mud flats that once created Fort Mifflin of Revolutionary War fame, and later Hog Island of the Naval Yard, home of the hoagie. Swans are beautiful creatures, but they seem to like a lot of mud. The lower Schuylkill is tidal, and the industrial waste of the region is cleaned out of the land by cutting drainage ditches laterally from the river, flooding the lowlands as the tide rises, and draining it again as the tide falls. This cleansing seems to be working, as judged by the return of spawning fish. And maybe mosquitos, as well, but it would seem rude to inquire.

The Bartram family seems to have known how to make use of river bends and riverbanks, placing the stone barn and farmhouse higher up the bank, but below the bluff of Gray's Ferry forces a bend in the Schuylkill, below which of course flatlands were created. It's a peaceful place, now made available for tours and excursions by placing a landing dock on metal pilings so that it can ride up and down with the tides. The great advantage is that riverboat landings are no longer restricted to two a day, at high tide, with limited time to visit before the tide falls again. Bartram recognized how popular strange plants from the New World would be in England, and his exotic plants were quite a commercial success. Nowadays the big sellers are Franklinia Trees, available the first week in May. The last Franklin (named of course for his friend Benjamin) ever found growing in the wild, was the one John Bartram found and nurtured. Every Franklinia is thus a descendant of this one. They look rather like dogwood but bloom in the early fall. If it suits the fancy, a dogwood next to a Korean dogwood which blooms in June, next to a Franklinia, can make a continuous display of bloom from May to October. And best of all, no one will appreciate it, unless they are in the know.

Wildlife in Haddonfield

A local clinical psychologist once kept a very large pig in his basement which eventually grew to such a size that getting it out of the basement was an engineering problem. The animal was given to his daughter when it was a cute little piglet; it eventually became a family crisis when the little girl had a fit over the suggestion it should be evicted. From this family, we learn that Haddonfield still has laws on its books prohibiting pigs and roosters, for obvious reasons if anybody wanted to keep them. There are no known horses or cows, but an occasional deer wanders by to eat the shrubbery. Dogs and cats don't exactly count.

But there are plenty of red foxes, quite large and bold, who seem to make the golf course their home and sneak around town by way of the stream beds and creeks. As do opossums and raccoons, who also have the storm sewers at their disposal. Possums like to climb on the outside of screen doors and windows, so they frequently startle the householders. Raccoons are unbelievably cute, especially when a set of little coons follow their mother single file, usually at night. They have a habit of eating through the roof and nesting in the chimney, causing quite a ruckus the first time in the fall when a fireplace is lit. Raccoons will kill a dog, by lying on their backs and clawing out the dog's underbelly, so not everybody is fond of them. As far as mammals are concerned, grey squirrels simply overrun Haddonfield, and spend a lot of time scolding the cats and dogs.

|

| Japanese Beetles feasting |

Some years ago, Japanese beetles were introduced to America first in nearby Moorestown, and now devastate the rose bushes. Their grubs burrow under the lawns, quickly followed by moles who like to snack on them, and either way the lawns suffer. The cure is to spread around the spores of milky spore disease, their natural enemy, and eventually, the roses and lawns recover. It isn't enough to spread milky spore on your own property, because the beetles will fly in from neighboring properties. I must confess to sending my ten-year-old son out at night with a can of milky spore, dusting it for half a mile in every direction. It seems to have worked, but that ten-year-old is now in his fifties, so it doesn't work quickly. There may be snakes and alligators, but no one has demonstrated one lately. Snapping turtles abound in the creeks ten miles from Haddonfield, so it wouldn't be surprising if some of them became venturesome. The local creeks are stocked with trout every spring, but you had better get there quickly before they are all gone. Catfish persist, however.

Birds love Haddonfield, and many species migrate back and forth, landing here. Robins like the earthworms in lawns, cardinals, and crows make a lot of noise, swallows, sparrows and unidentified little black jobs are abundant. Blue Jays hate cats and vice versa. But the best part is the owls. You can live your whole life in Haddonfield without seeing an owl, but they are watching you from the treetops. Ornithologists say you can't estimate the owl population unless you put out tape recorders at night, and then you hear an amazing number of them. I've finally found a mating pair in the top of one of my trees, hiding among the branches. They are a lot bigger than most people expect. My personal pair are about three feet long. This past summer a park ranger in Jackson Hole, Wyoming made the disconcerting observation that the nests of eagles usually contain a couple dogs' collars. Since owls are at least as high up the food chain as eagles and lots more plentiful, it's something to worry about if you let your dogs and cats run loose in Haddonfield. The neighbors are pretty fierce about unleashed pets, too.

|

| Beaver |

And this morning, March 31, I looked out the window and some passing workmen were chasing a beaver, trying to take its picture. That's right, a beaver, about three feet long, with a big flat tail. I meant to ask him where he came from, but he disappeared in the neighbor's bushes. In regions where there are a lot of beavers, people generally hate them. A pair of beavers can take down a big tree in half an hour, and a colony of beavers can turn a forest into a desert in a couple of seasons. But unless this fellow comes back, I'm not going to worry about it.

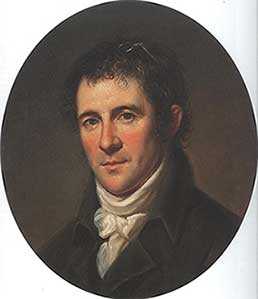

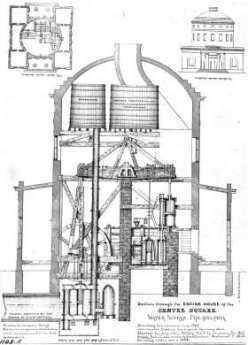

Water Works, Emblem of the Past

|

| Benjamin Henry Latrobe |

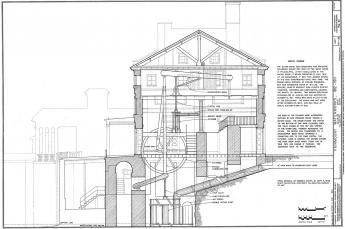

Philadelphia didn't really want the national capital to move to Washington DC, but the yellow fever epidemics, brought from Haiti by refugees, made it politically impossible to reverse the decision to move. We now know that Yellow Fever is transmitted by mosquitoes, but there were enough trash and pollution lying about the that it was plausible that polluted water was the cause. With no time to waste, water was piped in, through wooden pipes, from the comparatively pristine Schuylkill to a pumping station in Center Square, where City Hall now stands. Even today, no one wants a water tower in the neighborhood, so Benjamin Henry Latrobe made it look like a Roman Temple, thereby introducing classical architecture to Philadelphia, and starting quite a trend. The new system worked well enough from 1801 to 1815, when the new city outgrew it. Therefore, a new pumping system was built at the base of Faire Mount, where William Penn once planned to have a mansion, and was attached to Latrobe's wooden pipe system. In a unique and ingenious way,

|

| Latrobe Water Works |

Frederic Graff pumped Schuylkill water up to a series of reservoirs on top of Faire Mount, utilizing a water stack to maintain constant pressure. The classical architecture was continued, parks and decorative gardens were placed around it, and admirers came from around the world to marvel. Meanwhile, Latrobe's original building could now be torn down, providing room for City Hall, which was planned to be the tallest building in the world, although the French sort of cheated and put up Eiffel Tower, which in a sense really isn't a building. Meanwhile, Philadelphia and the rest of America kept growing and growing, leading to industrial plants along the Schuylkill all the way up to Pottsville, where the anthracite came from. The pure sparkling municipal water of which Philadelphia was so proud soon became a stinking sewer, and the Civil War encampments accelerated the process.

|

| Frederic Graff |

Following the lead of the Philadelphia College of Physicians, the concept of Fairmount Park emerged from clearing the banks of the river, and the Wissahickon Creek, of industry. The Philadelphia Water Works thus became the southern anchor of the largest city park in the world, including the building of Laurel Hill Cemetery, which had sanitary overtones which were embarrassing to discuss. Philadelphia led the world in adapting to this particular feature of the Industrial Revolution, and the insights of Louis Pasteur. By 1890, however, the system was again outmoded, and Philadelphia water became the butt of every joke. Between 1815 and 1840 the wooden pipes were replaced by iron ones. Robert Morris's old estate of Lemon Hill was acquired by Fairmount Park and used to construct a second reservoir on the neighboring hill. More about that second reservoir, in another blog.

Eventually, there would be more reservoirs at Belmont and Green Lane. But the city's new reputation for foul water was deserved. Deaths from typhoid fever rose to 80 per 100,000 residents before a water filtration system was installed; deaths from typhoid promptly fell to 2 per 100,000. Statistics on hepatitis were not available, but virus diseases must have been a serious hazard under primitive conditions of filtration, aeration and chlorination -- as they still are in many third-world countries, and in most southern European nations before 1950. As late as 1950 in Philadelphia, it was considered witty for a dowager to accept a drink from her hostess, saying "I'll drink absolutely anything, except Philadelphia water -- and 'Coke' ". The implication was that alcohol sterilizes water, which of course it doesn't, and also that absolutely everybody knows that Philadelphia has terrible water, whatever that means.

A reputation like that is bad for the city, making it harder to persuade workers and business to locate here, but the traditions underlying this response are quite ancient. Back in the days when water came from your own well, whole neighborhoods would move to new unspoiled areas to seek cleaner water and regions where the local privies were not yet mature. It takes quite a lot to persuade people to abandon the investment in a home or mansion as in Society Hill, and build a new one in a nearby undeveloped region. Particularly when the germ theory was not yet available to explain the issues with precision, pulling up stakes for a new neighborhood was an accepted reaction to almost any threat.

|

| Water Works Today |

However, strenuous exertions for half a century have made Philadelphia water safer, tastier, and far cheaper than bottled water. The recent trend of young people to walk about sucking a three dollar bottle of water drives the Philadelphia Water Department up to a wall. For example, 25% of bottled water comes straight from the tap. The inspection standards for public water are much stricter than for commercially bottled water, whose safety is in large part secondary to the safety of the tap water from which it is derived. True, public water is chlorinated, but then it is also fluoridated, putting legions of dentists out of business. In Philadelphia, that's the main difference justifying the rather appalling price difference, and the accumulation of plastic bottles in various trash heaps.

The recent advances in Philadelphia's water can in part be traced to Ruth Patrick, now over a hundred years old but the world's foremost expert on streams and water, and to the persistent professionalism of the Philadelphia Water Department. Perhaps, though, it may take a century of slander about water to persuade the politicians to keep their hands off the Water Department. It does take a lot of tax money to implement the third step in the process of cleaning up the water supply, which is the purification of wastewater. For centuries, the guiding principle was to obtain and maintain pure water at the source; wastewater was flushed down the sewer to go back out to the ocean. However, seven times as much water is removed from Delaware, as it flows past the city. That is, the water now recirculates through the sewage system seven times before it is turned over to residents of lower Delaware Bay. The expensive and elaborate -- but scarcely visible -- system of treating sewage in various sewage treatment centers has now resulted in returning water to Delaware in better condition of purity than it had when it came down past Bucks County.

But it costs lots of bucks, and nobody seems to notice the water. People only notice the bucks.

Heron Rookery on the Delaware

|

| Great Blue Heron |

When the white man came to what is now Philadelphia, he found a swampy river region teeming with wildlife. That's very favorable for new settlers, of course, because hunting and fishing keep the settlers alive while they chop down trees, dig up stumps, and ultimately plow the land for crops. As everyone can plainly see, however, the development of cities eventually covers over the land with paving materials; it becomes difficult to imagine the place with wildlife. But the rivers and topography are still there. If you trouble to look around, there remain patches of the original wilderness, with quite a bit of wildlife ignoring the human invasion.

|

| Heron Nests |

Such a spot is just north of the Betsy Ross Bridge, where some ancient convulsion split the land on both sides of the Delaware River; the mouth of the Pennypack Creek on the Pennsylvania side faces the mouth of the Rancocas Cree on Jersey side. In New Jersey, that sort of stream is pronounced "crick" by old-timers, who are fast becoming submerged in a sea of newcomers who don't know how to pronounce things. The Rancocas was the natural transportation route for early settlers, but it now seems a little astounding that the far inland town of Mt. Holly was once a major ship-building center. The wide creek soon splits into a North Branch and a South Branch, both draining very large areas of flat southern New Jersey and making possible an extensive network of Quaker towns in the wilderness, most of whose residents could sail from their backyards and eventually get to Europe if they wanted to. In time, the banks of the Rancocas became extensive farmland, with large flocks of farm animals grazing and providing fertilizer for the fields. Today, the bacterial count of Delaware is largely governed by the runoff from fertilized farms into the Rancocas, rising even higher as warm weather approaches, and attracting large schools of fish. My barber tends to take a few weeks off every spring, bringing back tales of big fish around the place where the Pennypack and Rancocas Creeks join Delaware, but above the refineries at the mouth of the Schuylkill The spinning blades of the Salem Power Plant further downstream further thin them out appreciably.

Well, birds like to eat fish, too. For reasons having to do with insects, fish like to feed at dawn and dusk, so the bottom line is you have to get up early to be a bird-watcher. Marina operators have chosen the mouth of the Rancocas as a favorite place to moor boats, so lots and lots of recreational boaters park their cars at these marinas and go boating, pretty blissfully unaware of the Herons. Some of these boaters go fishing, but most of them just seem to sail around in circles.

|

| As Seen From Amico Island |

Blue herons are big, with seven-foot wingspreads as adults. Because they want to get their nests away from raccoons and other rodents, and more recently from teen-aged boys with 22-caliber guns, herons have learned to nest on the top of tall trees, but close to water full of fish. And so it comes about that there is a group of small islands in the estuary of the Rancocas, where the mixture of three streams causes the creek mud to be deposited in mud flats and mud islands. There is one little island, perhaps two or three acres in size, sheltered between the river bank and some larger mud islands, where several dozen families of Blue Herons have built their nests. One of the larger islands is called Amico, connected to the land by a causeway. If you look closely, you notice one group of adult herons constantly ferries nest building materials from one direction, while another group ferry food for the youngsters from some different source in another direction. At times, diving ducks (not all species of ducks dive for fish) go after the fish in the channel between islands, with the effect of driving the fish into shallow water. The long-legged herons stand in the shallow water and get 'em; visitors all ask the same futile question -- what's in this for the ducks? The heron island is far enough away from places to observe it, that in mid-March its bare trees look to be covered with black blobs. Some of those blobs turn out to be heroes, and some are heron nests, but you need binoculars to tell. When the silhouetted birds move around, you can see the nests are really only big enough to hold the eggs; most of the big blobs are the birds, themselves. There are four or five benches scattered on neighboring dry land in the best places to watch the birds, but you can expect to get ankle-deep in the water a few times, and need to scramble up some sharp hills covered with brambles, in order to get to the benches. In fact, you can wander around the woods for an hour or more if you don't know where to look for the heron rookery. Look for the benches, or better still, go to the posted map near the park entrance south of the end of Norman Avenue. There are a couple of kiosks at that point, otherwise known as portable privies. Strangers who meet on the benches share the information supplied by the naturalists that herons have a social hierarchy, with the most important herons taking the highest perches in the trees. That led to visitors naming the topmost herons "Obama birds", and the die-hard Republicans on the benches responding that the term must refer to dropping droppings on everybody else. That's irreverent Americans for you.

There is quite a good bakery and coffee shop just north on St. Mihiel Street (River Road), and the new diesel River Line railroad tootles past pretty frequently. That's the modern version of the old Amboy and Camden RR, the oldest railroad in the country. It now serves a large group of Philadelphia to New York commuters, zipping past an interesting sight they probably never realized is there because they are too busy playing Hearts (Contract Bridge requires four players, Hearts are more flexible). However, there's one big secret.

The birds are really only visible in the Spring until the trees leaf out and conceal them. Since spring floods make the mud islands impassible until about the time daylight savings time appears, there remains only about a two-week window of time to see the rookery, each year. But it is really, really worth the trouble, which includes getting up when it is still dark and lugging heavy cameras and optics. Dr. Samuel Johnson once remarked that while many things are worth seeing, very few are worth going to see. This is worth going to see.

And by the way, the promontory on the other side of the Rancocas is called Hawk Island. After a little research, that's very likely worth going to see, too.

Reservoir on Reservoir Drive

William Penn planned to put his mansion on top of Faire Mount, where the Art Museum now stands. By 1880, long after Penn decided to build Pennsbury Mansion elsewhere, city growth outran the capacity of the new reservoir system which had then been placed on Fairmount. An additional set of storage reservoirs were placed on another hill across East River (Kelly) Drive, behind Robert Morris' showplace mansion now called Lemon Hill (Morris merely called it The Hill); the area was eventually named the East Park Reservoir. In time, trees grew up along the ridge and houses got built; the existence of these reservoirs right in the city was easily forgotten, even though the towers of center city are now plainly visible from them. These particular reservoirs were never used for water purification; that's done in four other locations around town, and the purified water is piped underground to Lemon Hill, for last-minute storage; gravity pushes it through the city pipes as needed.

Now, here's the first surprise. Water use in Philadelphia has markedly declined in the past century. That's because the major water use was by heavy industry, not individual residences, so one outward sign of the switch from a 19th Century industrial economy to a service economy is -- empty old reservoirs. Only one-quarter of the reservoir capacity is in active use, protected by a rubber covering and fed by underground pipes. The rest of the sections of the reservoir are filled by rain and snow, but gradually silting up from the bottom, marshy at the edges. Unplanted trees have grown up in a jungle of second-growth, attracting vast numbers of migratory birds traveling down the Atlantic flyway. Although there are only a hundred acres of water surface here, the dense vegetation closes in around the visitor, giving the impression of limitless wilderness, except for the center city towers peeping through gaps in the forest. It's fenced in and quiet except for the birds. For a few lucky visitors, it's easy to get a feeling for how it must have looked to William Penn, three hundred or more years ago, and Robert Morris, two hundred years ago. In another sense, it demarcates the peak of Philadelphia's industrial age, from 1880 to 1940, because that kind of industrialization uses a lot of water.

The place, in May, is alive with Baltimore Orioles. Or at least their songs fill the air and experienced bird watchers know they are there. Even a beginner can recognize the red-winged blackbirds, flickers, robins, and wrens (they like to nest in lamp posts). The hawks nesting on the windowsills of Logan Circle suddenly makes a lot more sense, because that isn't very far away. In January, flocks of ducks and geese swoop in on the water surface, which by spillways is kept eight feet deep for their favorite food. Just how the fish got there is unclear, perhaps birds of some sort carried them in. The neighborhoods nearby are teeming with little boys who would love to catch those fish, but it's fenced and guarded much more vigorously since 9-11. In fact, you have to sign a formal document in order to be admitted; it says "Witnesseth" in big letters. Lawyers are well known for being timid souls, imagining hobgoblins behind every tree. However, there are some little reminders that evil isn't too far away. Just about once a week, someone shoots a gun into the air in the nearby city. It goes up and then comes down at random, with approximately the same downward velocity when it lands as when it left the muzzle upward. That is, it puts a hole in the rubber canopy over the active reservoir, which then has to be repaired. No doubt, if it hit your head it would leave the same hole. So, sign the document, and bring an umbrella if the odds worry you.

A treasure like this just isn't going to remain as it is, where it is. It's hard to know whether to be most fearful of bootleggers, apartment builders or city councilmen, but somebody is going to do something destructive to our unique treasure, possibly discovering oil shale beneath it for example, unless imaginative civil society takes charge. At present, the great white hope rests with a consortium of Outward Bound and Audubon Pennsylvania, who have an ingenious plan to put up education and administrative center right at the fence, where the city meets the wilderness. That should restrict public entrance to the nature preserve, but allow full views of its interior. Who knows, perhaps urban migration will bring about a rehabilitation of what was once a very elegant residential neighborhood. And push away some of those reckless shooters who now delight in potting at the overhead birds.

This whole topic of waterworks and reservoirs brings up what seems like a Wall Street mystery. Few people seem to grasp the idea, but Philadelphia is the very center of a very large industry of waterworks companies. The tale is told that the yellow fever epidemics around 1800 were the instigation for the first and finest municipal waterworks in the world. There's a very fine exhibit of this remarkable history in the old waterworks beside the Art Museum. But that's a municipal water service; why do we have private equity firms, water conglomerates, hedge funds for water industries, and other concentrations of distinctly private enterprise in the water? One hypothesis offered by a private equity partner was that the success of the municipal water works of Philadelphia stimulated many surrounding suburbs to do the same thing; it was surely better than digging your own well. This concentration of small and fairly inefficient waterworks around the suburban ring of this city might well have created an opportunity for conglomerates to amalgamate them at lower consumer cost. Anyway, it seems to be true that if you want to visit the headquarters of the largest waterworks company in the world, you go about seven miles from city hall and look around a nearby shopping center. If you are looking for the world's acknowledged expert in rivers, you go to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia on Logan Square and look around for a lady who is 104 years old. And if you have a light you are trying to hide under a barrel, come to Philadelphia.

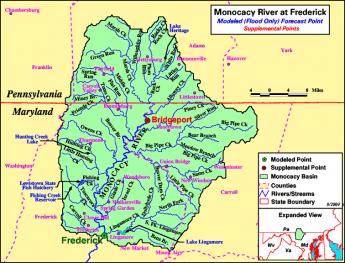

Monocacy Creek and Monocacy River

|

| Monocacy River |

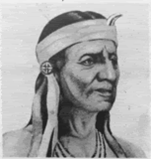

Monocacy sounds like a Greek word for some form of government, but is in fact a Shawnee Indian term, meaning "crooked river". It might well be spelled as the Indians pronounced it, Monnockkesey. Confusion for history lovers is made worse by the existence of a Monocacy Creek about twenty miles long, flowing into the Lehigh River at Bethlehem. But there is a second stream, the Monocacy River, flowing about sixty miles south from Gettysburg, through the town of Frederick, Maryland, eventually merging with the Potomac River a few miles south of Harper's Ferry. Both forms of Monocacy do flow-- but do not connect-- along the base of the first mountain range of the Alleghenies, on its Eastern side. Pennsylvanians refer to this ridge as the Blue Mountain because looking westward it can be hazily seen across the plain from a great distance. In Maryland, it is called the South Mountain. In the early part of the Civil War, General Lee attempted to attack Washington DC from the rear by striking through several gaps (particularly "Fox's Gap") in that mountain. The Philadelphian General George McClellan uncharacteristically surprised him by getting masses of Federal troops through the mountain gaps before Lee could reach and fortify them from West Virginia. Although McClellan did intercept some of Lee's orders, it is now questioned whether this affected the outcome. The culminating result was what the Union side continues to call the Battle of Antietam Creek, but the former Confederates persist in naming the Battle of Sharpsburg. Antietam Creek is one of those many creeks which flow along either side of the long mountain range, fed by runoff rainwater from the ridge, and therefore has steep embankments. Regardless of the nomenclature quarrel, the main point is that both of these placenames refer to the west side of the mountain gap, putting Lee at a disadvantage for an attacker. He got there first, but he did not get there first with enough force to dominate the passes.

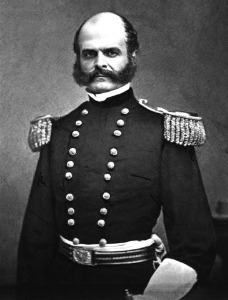

|

| General Ambrose Everett Burnside |

A horrendous slaughter of Federal troops took place when General Burnside was ordered by McClellan to get his troops across Antietam Creek immediately, and Burnside chose frontal attacks over a narrow stone bridge crossing the Antietam as the way to get there. Because of the creek's flow along the base of the mountain, once the bridge was crossed under constant sniper fire, the troops faced a sheer embankment which had to be climbed into the face of 500 Confederate sharpshooters shooting down from the top. Burnside and the Federal troops finally did accomplish this suicide mission after four hours of trying, mostly because the Confederate sharpshooters ran out of ammunition. At the end of that day, 23,000 troops on both sides were casualties. Toward the end of the war, similar casualties would be sustained fifty miles north at Gettysburg PA, along a branch of the Monocacy on the east side of the ridge. The two Monocacy streams, Creek and River, are entirely distinct but a natural source of confusion.

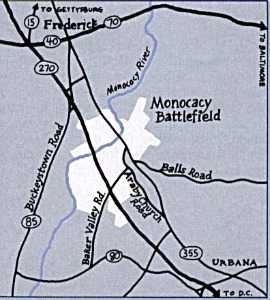

|

| Monocacy River Map |

It would seem a pity, however, to succumb to a fit of tidiness and change the name of either stream. The Shawnees were once the most important Indian tribe in this region, and at various times have achieved dominance over regions from the Delaware River to Oklahoma. As a major component of the Algonquin federation of tribes, they fought a losing battle with the Iroquois over a period now named the Sixty Years War, eventually retreating from the Eastern Alleghenies to Ohio. Meanwhile, the Iroquois were destroyed by the consequences of the Revolutionary War, while eventually, the Shawnees retreated to reservation areas in Oklahoma. The Monocacy streams, both of them, represent a high-water mark of Shawnee influence. It would be sad to see the last few vestiges of their pre-eminence, even if only names on a map, destroyed by inadvertence or indifference.

Central Pennsylvania Settlers Before 1700

|

| German Rhineland |

Dates are unclear, but twenty-five families from the German Rhineland bought Pennsylvania land from William Penn prior to 1700, which is the earliest recognizable date on a gravestone in the Hummelstown Cemetery. Future research may narrow that time interval down, but it can confidently be said they got on a sailing ship bound for Philadelphia between 1682 and 1699. For reasons also unknown, tradition relates the Captain refused to stop in Philadelphia, putting them off in New York. They discovered they were unwelcome among the Dutch settlers in New York, who quite likely reflected the ancient hostility between the Dutch at the mouth of the Rhine River, and the Germans living upstream from there. Augmented by wars and invasions, the feeling persists to some degree even today. The twenty-five families sailed from New York, up to the Hudson River to Kingston the state capital, where they discovered they were even more unwelcome. The British under the command of the Duke of York took over New Amsterdam in 1664, but Dutch cultural control persisted long after the change of political control.

|

| Governor Keith of Pennsylvania |

Tradition continues that Governor Keith of Pennsylvania happened to be in Kingston at the time of the stranding of the migrants. He suggested they travel eighty miles overland to the Susquehanna River and then float down to land where topsoil was reputed to be several feet thick. Since Dutchmen everywhere concentrated on fur trading more than farming, it seems safe to guess reliable guides were easily found in Kingston. From there to what later became famous as Three-Mile Island below Harrisburg, the three-hundred-mile route of these pilgrims can be guessed by following valleys between towering ridges. Unfortunately for this surmise, there are two main canyons leading to Kingston from the Susquehanna, which improved Kingston as a choice for fur trading. The more northerly canyon is somewhat longer, but it might have been safer; perhaps the German pilgrims just flipped a coin. Taking either choice it's a hard trip however, even assuming the Indians were friendly and food sources abundant. It must have required at least a month to go the full distance to what is now Harrisburg, passing by a number of places which now support prosperous farms. That potential likely provoked demands of some travelers that they had gone far enough, as kids do today in the back of the station wagon. By luck or stubbornness, however, they kept right on into the wilderness, eventually making permanent settlements along the Swatara Creek in Dauphin County, which proves to have the richest farmland in America. Middletown and Hummelstown are thus the two oldest settlements in Central Pennsylvania. By the time the other German sects made their way up Germantown Avenue, out Germantown Pike, and then onward to the Great Valley beside Blue Mountain, the original settlers had ample time to discover the best land, the surest wells, and the best access to the creeks. Furthermore, they had several generations to notice which families produced the strongest lads, and which families were the best natural farmers. Since later incoming families were mostly penniless, they had to settle for less advantageous farmland and less endowed marriage partners. Dominance by the original farming families continued until the early Twentieth century when it became prestigious to enter one of the professions. Or even to move away from the Dutch Country and go to the city.

|

| Dutch Ships |

Getting back to their days in Kingston, it is not easy to tell what route they took, judging only from a highway map. We look for the largest towns and then the shortest highway route, but it seems likely Kingston was chosen as a trading center because it was the place where the fur traders brought their pelts to the Dutch ships on the Hudson. The roads chose the towns, not the other way. When you observe the valley beginning at Kingston, there remains little doubt the route to Harrisburg must have led that way. The local folks at the museums and stores of Kingston can't help; they never heard of any such migration, and most of them never had reason to travel in that direction. Kingston was burned to the ground (by the British) in 1777, the state capital moved to Albany, and the economic center went south to New York City. Kingston is just a nice little town on the Hudson, across the river from where rich folks put their mansions, and liberal-minded folks send their children to Bard College, a place where no two buildings follow the same architectural style.

So when you go West from that nice little town, it is only a mile or two before you are out in the woods, with farms here and there, and scattered cabins which look like fishing and hunting "lodges". There's a creek in the bottom of the valley, and if you look up, you see the road merely winds its way between parallel mountain ridges. Perhaps a glacier carved out this trail, perhaps a mighty river once ran there, perhaps volcanic action tented up and cracked. Anyway, you are not going to get lost if you follow the creek, going steadily uphill from Kingston for twenty or thirty miles. If this were a single mountain ridge, you would be approaching either a water gap or a wind gap. A wind gap is a water gap that has lost its river at the top.

|

| The Rhine River |

What's at the summit is not a notch, however, it's a bowl. Out of this bowl flow the three main rivers of the eastern seaboard, the Hudson, Delaware, and the Susquehanna. The effect resembles what is said of Switzerland: The Rhine, the Rhone, Danube, and Po; They rise in the Alps, and away they go. The highway from Kingston runs along a creek which flows into the Hudson. At the top of the bowl are some nice dairy farms scattered along ten miles which drain into Delaware. The East Branch and the West Branch of the Delaware River are scarcely more than creeks at this point. At Delhi and Andes there is a further rise in the mountains, and then along twisting decline as you follow a branch of the Susquehanna down to its junction at Oneonta. As you cross the top of the ten-mile mesa you have perceived the answer to a natural question: how did those German families get across the big wide Delaware River that runs between Kingston on the Hudson -- and Cooperstown, where the Susquehanna begins? The answer is pretty evident. Delaware, while a mile wide at Philadelphia, narrows down to two little creeks on this mountain plateau. The Susquehanna system on one side and Hudson on the other have swallowed up the Delaware watershed between them. This might well have seemed a nice place for the German settlers to set up a few dairy farms, but it probably was an even more ideal place for the Iroquois to set up headquarters. Their favorite style of warfare was to occupy the high ground and make lightning raids (or quick escapes) on canoes down the various rivers starting from their origins. If it's of any interest, Charles Evans Hughes began his law practice in Delhi, and a lot of the town boys were killed at the battle of Antietam, thus illustrating the unwisdom of recruiting whole towns into regiments.

Down the mountain we go, into the broad Susquehanna valley. It was probably troublesome to manage wagons down a mountainside. But from here on the German families could stop walking, and float.

Dingman's Ferry, Below Port Jervis

|

| Dingman Ferry Bridge |

Because the area was once covered with a glacier, the northeast corner of Pennsylvania is fairly deserted. That's always been good for hunting and fishing, and more recently is good for skiing. Although the topsoil is poor, it's a beautiful area, practically guaranteed to provoke confrontation between the environmentalist movement and the Marcellus shale-gas extraction industry. The history of anthracite coal demonstrates locally that the mineral extraction industry always wins these arguments in the short run, but ultimately the land seems to heal itself without much help from people living in city apartments. The followers of Gifford Pinchot and Teddy Roosevelt are slowly learning to concentrate on minimizing the damage and forcing the extraction industries to pay for clean-up afterward. Right now, this semi-wilderness area is a remarkably beautiful but deserted forest within two hours drive of Philadelphia and New York City. It contains the headwaters of the three main rivers of Northeastern United States.

Crossing those three rivers was the main geographical problem for the Connecticut invaders of Pennsylvania. Today, the landscape is not a great deal different except for the absence of Indians, and crossing the three rivers is the main event. There's a Hudson River bridge at Newburgh, and crossing the Susquehanna at Wilkes-Barre is a placid bridge within a town park. From the point of view of the Interstate highway, crossing Delaware occurs very near the highest point in New Jersey, over a deep rocky gorge with boaters deep below. Since the traveler is at a peak point within a long wide mountain valley, the view is spectacular in several directions.

However, for centuries the builders of roads had to operate on a modest budget, and the only reasonable place to cross Delaware in that region is a few miles south of Port Jervis, at Dingman's Ferry. The Dingman family prospered at their trade for many generations before they modernized and constructed a toll bridge, which is now one of the few remaining toll bridges in private hands, and possibly the oldest one. You don't have to ask the two jolly old toll collectors whether they are part of the Dingman family because they certainly act like it, adding to the wad of dollar bills in their left hand as they greet the fellas, josh the girls, and wave directions with a free hand. A quarter-mile to the south of the bridge on the Pennsylvania side is the entrance to a trail leading to a National Park Service station. The Park Guards are a friendly sort, most of them freely admitting they are members of the Dingman clan, available to help tourists interested in a trail walk, including a visit to the local waterfall. In spite of all this family connection, and Park Service training, nobody at the station had ever heard of the march of the Connecticut invaders. Or of the Proprietorships of West and East Jersey, or of the line between them which allegedly ends at Dingman's Ferry. The best they could do was the point to the local cemetery, which has a big rock at the entrance that somehow has some particular significance, or other.

As it turns out, the cemetery is quite large, with surely a thousand or more gravestones, a great many of which fly American Legion flags for veterans of one war or another, and many more are decorated with fresh flowers. Only a corner of this graveyard touches the curving road to The Bridge, and just inside the entrance is a very large, unmarked stone. Trees have been planted nearby, and their roots have half-covered the rock. But the roads and the cemetery, in general, seem designed around it. There's no marker to explain it, any more than there is a plaque at Stonehenge. As the Park Ranger said, it has clear significance, but no one now seems to know what it is significant of.

Well, if no one is likely to contradict, let's make the timid suggestion that this may be the terminus of the line dividing East from West Jersey. Yes, it's in Pennsylvania. But there is nothing more likely on the New Jersey side of the crossing, and the current Surveyor-General of West Jersey, William Taylor, is firm in the belief the line terminated at Dingman's Ferry. William Penn had hoped to control land on both sides of the river, and when he acquired Pennsylvania in addition to New Jersey, the issue became moot. The style of the survey had been to start at Beach Haven ("Ye inlet of ye beach of Egg Harbor") and follow the compass until it hit something large and heavy. That rock was marked, and another survey went the next step. About fifty of these markers have been discovered by later explorers, and officially represent the underlying fixed line which serves as a survey basis for every property in the state of New Jersey. Since I own some property in New Jersey myself, it seems important to be sure I know where it is, or else some trial lawyer may try to take it away.

South Philadelphia: Ideal Intermodality Transportation Site

The Right Angle Club was recently visited by Troy Adams, representing the Greater Philadelphia affiliate of the regional Chamber of Commerce. Sustained by contributions from sixty local corporations, the Greater Philadelphia organization is a major storehouse of data useful for businesses, supported by a staff of analysts and computer experts. The purpose of this institution is to help businesses who are trying to decide whether or how to locate in the Philadelphia region. With such an organization behind him, Mr. Adams was able to show a number of slides displaying the demography, geography, and statistics about our region, and his appearance is greatly appreciated. This is definitely the place to go if you have questions of that sort. It would probably also be a good place to go for opinions and gossip about the politics and inside baseball of the town, but the Chamber has a strict rule about avoiding any involvement in business moving from one district to another within the region or hearsay that might lead to such internal friction.

One really important insight into the potential of our region concerns South Philadelphia. Historically, this was the place where the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers met, and was once a very big swamp (wetland, nature sanctuary or whatever). Over time, the swamp became a trash and garbage landfill, and over still more time it became a big flat uninhabited area right next to a big city. But then an Interstate Highway (I95) was built on its circumference, and several rail lines, and an international airport, not to mention extensive port and shipping terminals for ocean transport. While it is true that a certain number of houses would have to be purchased and demolished to accomplish it, the potential exists for the construction of an intermodal interconnection which would be almost unique in the world.

|

| South Philadelphia Ports |

There would be plenty of lands left over for industries related to freight forwarding and the like (the food distribution center is a good example of the general concept), and all of this would be within twenty minutes of the center of a major city. SEPTA already sends a passenger rail spur from the very heart of the city to the very center of the airport, and there is no reason it could not be extended to include ocean, bus, and distribution terminals. Whether this exactly fits with the extensive sports stadium complex in the area is unclear, but these entertainment features are doing no harm to the intermodal interchange idea in the meantime. Judging by the city government's willingness to tear these structures down every five or ten years, there should be no great resistance to moving them elsewhere if the need should arise.

Reviving Schuylkill: Eight Miles From the Dam to Ft. Mifflin

|

| Joshua Nims |

Joshua Nims of the Schuylkill River Development Corporation recently addressed the Right Angle Club about current activities of that organization. It's a non-profit corporation, but in a sense is a quasi-City agency, spending State and Federal funds, plus remediation funds. Just what remediation funds are was not clearly explained, but seem to be fines or assessments on companies who are thought to have fouled up the environment. Whether those assessments are fair or unfair, too small or too large, are political issues largely avoided in Mr. Nims' presentation, and hence are avoided here.

|

| Gray's Ferry Bridge |

The Gray's Ferry area is certainly an urban tragedy of epic proportion, but since its deterioration began in 1856, the events of the Civil War probably had a lot to do with it. Up until the Civil War, the western banks of the Schuylkill, especially around Gray's Ferry, were famously upscale and beautiful. The South Street Bridge, for example, was originally envisioned as leading into a boulevard of the Arts, with the University Museum, Irvine Auditorium, the University Hospital and the mansions on the top of the hill setting off what promised to become a striking cultural statement. Anthony Drexel himself lived up there, walking it to work at Third and Chestnut. And that's just one famous example. It's hard to know what started the blight, but Harrison Brothers White Lead, Color and Chemical Works might be a good candidate and the fact that the area soon developed the tracks often (10) smoke-belching railroads was certainly another major issue. The western bank of the Schuylkill rose to a high rocky promontory at Gray's Ferry, crowding wartime industrialization into a narrow place. Before that, Gray's Ferry Bridge had been the main artery to the South, traveled by George Washington many times, often stopping at Woodlands, that palatial home of Andrew Hamilton the original Philadelphia lawyer. A century before that, the Dutch fur traders had found it to be the first firm land after they sailed inland through the swamp, while the Indians knew it was the last forest area before you reached the (South Philadelphia) area of malaria, yellow fever and other mysterious vapors that must be avoided. In the sense of land travel, Gray's Ferry was, therefore, the most prominent part of the Philadelphia landscape for two centuries. The ferry itself was a floating bridge, pulled back and forth by ropes on each shore of the river. Given a choice of pretty much all of the North American continent, John Bartram placed his farm just south of this promontory. Where it still stands today but surrounded by slums and urban decay.

It's a little hard to judge whether the Civil War pushed railroad construction into the only rocky crevice suitable, and then industrial pollution followed with vile and noxious effluents, or whether the Harrison Lead, Color, and Chemical factory simply started it across the river in the river bend. That's where the DuPont paint factory relocated in 1916, and in fact, the Duponts get local blame as polluters when in fact they made considerable effort to clean things up after they acquired it. The area had a major slaughterhouse abattoir, and an asphalt plant and several other major inducements to the populace to abandon their elegant mansions and run for their lives. The place now has old rusting bridges, tumble-down concrete pilings, lots of weeds, and not a single living fish for a century in that water. To diffuse the blame somewhat, it should be remembered that after the War of 1812, the Schuylkill was the main transportation artery for coal coming down from Pottsville and the rest of Schuylkill County. The river didn't have a sandy bottom, it was pulverized anthracite which releases acids and toxins when washed.