Related Topics

Philadelphia's River Region

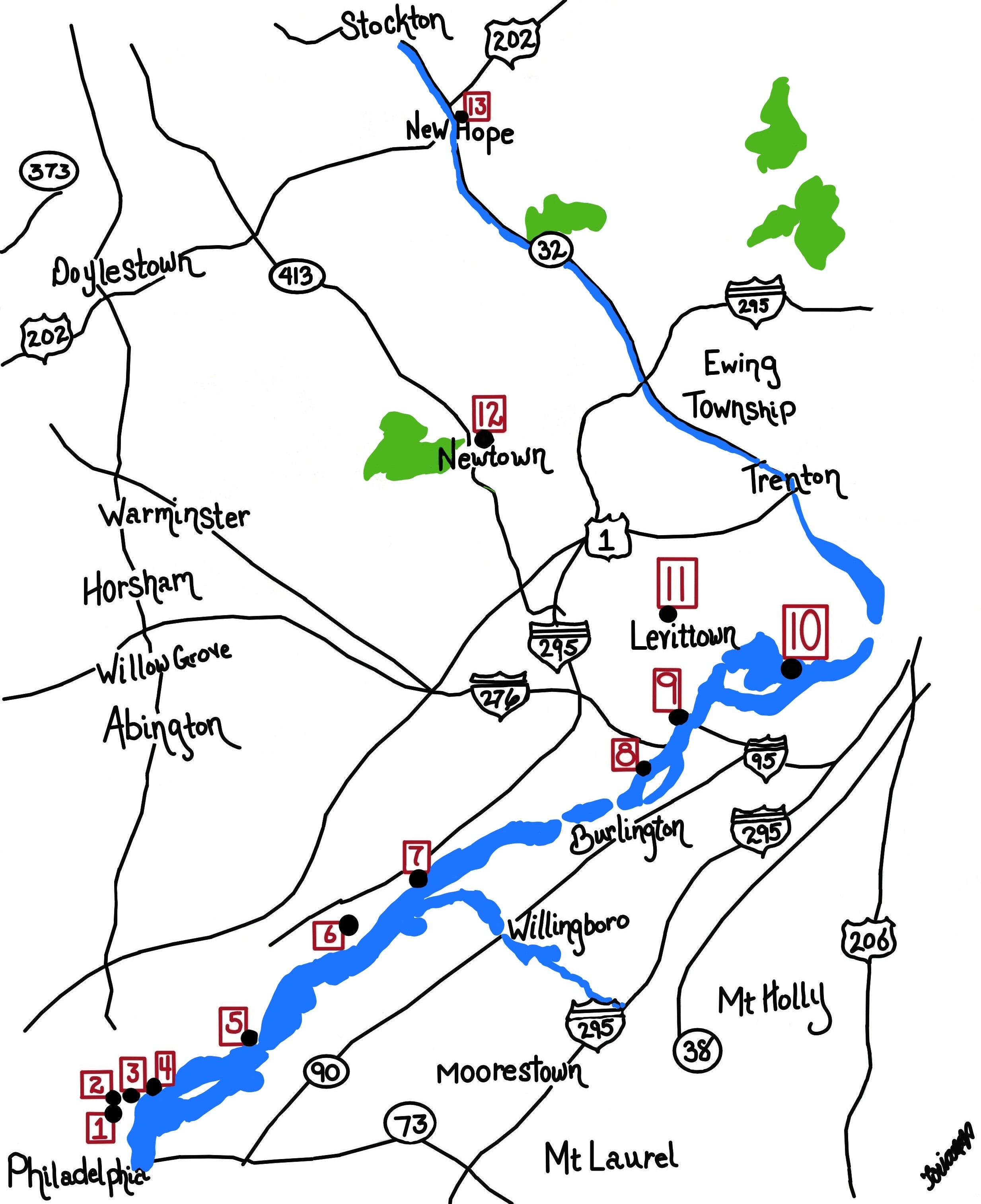

A concentration of articles around the rivers and wetland in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

To Germantown, a Short Appreciation

Seven miles from the heart of Philadelphia, Germantown was once a separate town, the cultural center of Germans in America. Revolutionary battles were fought here, it was briefly the capital of the United States, and it still has an outstanding collection of schools and colleges.

Nature Preservation

Nature preservation and nature destruction are different parts of an eternal process.

Pre-Revolutionary Philadelphia

.

Right Angle Club: 2013

Reflections about the 91st year of the Club's existence. Delivered for the annual President's dinner at The Philadelphia Club, January 17, 2014.

George Ross Fisher, scribe.

City Hall to Chestnut Hill

There are lots of ways to go from City Hall to Chestnut Hill, including the train from Suburban Station, or from 11th and Market. This tour imagines your driving your car out the Ben Franklin Parkway to Kelly Drive, and then up the Wissahickon.

The Wissahickon

Recently, Sarah West came to the Right Angle Club and told us about the history of the Wissahickon Creek. Sarah taught at Germantown Friends School for twenty-five years, and in the course of it became the acknowledged expert on the Wissahickon. The mouth of the creek empties into the Schuylkill in Fairmount Park, but the mouth of it is so covered over with a tangle of clover-leaf overpasses, most people zip past without noticing. After that, the drivers of cars up to Chestnut Hill are so busy negotiating the sharp curves, they don't see much of the rest of the creek, either. There's a stop light opposite Rittenhousetown, so perhaps the little village is noticed on the other side of the rivulet, but the entrance is off to the left on Wissahickon Avenue, approachable only from the other direction, so even this cute little village is seldom visited. Pity.

First, notice that the mouth of the creek is just opposite City Line Avenue, so it is an important geographical landmark. The creek is 23 miles long, going right past Roxborough and ending up well beyond Philadelphia's city limits. To a passing motorist, the creek seems to disappear at Rittenhousetown, and the commuter goes on his way through miles of the city before reaching Chestnut Hill. In fact, the creek curves abruptly north at Rittenhousetown and travel twenty miles through woods and wilderness, accompanied by fifty miles of hiking trails. This Wissahickon Park contains about 1200 acres of the 9600-acre Fairmount Park; at one time it was lined with mills seeking water power for one industrial activity or another. From Rittenhousetown to Chestnut Hill College the creek is accompanied by Forbidden Drive, forbidden (in 1922) to automobiles, that is. It crosses Germantown Avenue at that point and circles around Chestnut Hill College, only a branch disappears back into the woods surrounding the edges of the College and Morris Arboretum. On its right that branch of it, starting at Chestnut Hill College, passes (and supplied water for) Washington's encampment at Fort Washington. As a sidelight, Forbidden Drive parts company with the creek at Chestnut Hill College and the main branch of the creek goes on for miles past the Whitemarsh Country Club, then the Germantown Cricket Club, and the Wissahickon Valley Park, eventually reaching its origin in the water runoff from a parking lot off in the country near Ambler, well past Fort Washington, out in Montgomery County.

Only a short part of the Wissahickon is visible from the paved road, which veers to its right near the top of the steepest dropdown of the cliff on the west side of Germantown. That's one of two ridges. Roxborough is on one side of the valley, Germantown and Chestnut Hill on the east. The longest part of the creek veers to the left up to the wooded valley, along miles of Forbidden Drive before it re-emerges to the sight of motorists as it crosses Bethlehem Pike. This was one of several routes followed by sections of Washington's army in their attack on the Chew Mansion in the Revolutionary War. Washington lost, partly because of the stout stone walls of the Chew House, and partly because two sections of his troops got lost in the fog along the creek and started shooting at each other. Even today, the geography around here is so confusing it is really pretty hard to criticize Washington for getting mixed up.

The edge of the Wissahickon Creek was first settled by an early group of Germans led by Johannus Kelpius in the Seventeenth Century; the Kelpius Society feels that colony was located around the Henry Avenue Bridge footings standing athwart the gorge, comparatively near the mouth of the creek into the Schuylkill. Swift waters running downward provided water power for mills, originally paper mills. Paper plus education leads to printing, and at this point was located the heart of German culture, running north and south through all the thirteen colonies; eventually, this settlement of Baptists, Dunkards, and Church of the Brethren moved westward toward Ephrata and other more scattered locations. Sarah tells us that a good workman could produce about three hundred sheets of paper in a day, so it had to be of good quality. Many of the historical documents of the Revolutionary period were written or printed on this paper. Bear in mind, however, that nothing smells so bad as a paper mill.

It takes wood to make paper, so paper mills tend to denude the surrounding hills and start a process of washing away the topsoil. The creeks started to flood in the spring, and dry up in the summer. The final blow of this type was caused by Hurricane Floyd in 1985, which washed away many of the landmark buildings, leaving miles of the woods to the pleasure of hikers and joggers and environmentalists. Sarah West reports that you don't have to walk very far into the woods to find the remnants of mills and mansions, many of which had fruit cellars dug into the side of the basements. Some of these fruit cellars were then extended into tunnels, allowing the Underground Railroad to flourish here before the Civil War. And possibly earlier than that, because this area close to Philadelphia was a favorite place for spies to hide, attracting British raiding parties during the Revolution.

|

| Wissahickon Valley |

But water power was water power in Colonial days, and mills of all kinds flourished up and down the length of the creek until steam power ultimately posed too much competition. For a while, the dwindling water-powered mills supplemented their power with the steam generation, and tall smokestacks, but eventually, water power was driven away by steam power. Whether it was a flour mill or a nuts and bolts factory, grist mills or blanket factories, the product was usually shipped in white oak barrels, which hastened the destruction of the woods and made the flooding worse. Around each mill was usually found a cluster of houses for the workers, so the whole Wissahickon Valley eventually filled with settlements, usually with the owner's mansion dominating the scene, surrounded by little workers' houses. Eventually, the stream became polluted, and the pollution was unfairly blamed for Yellow Fever epidemics. The Schuylkill Water Works and the migration of the factories elsewhere did a whole lot of good for typhoid fever, which definitely is caused by water pollution. So pollution control is sometimes useful even if there is no pollution of the kind you had in mind. The area became Fairmount park, dotted with mansions which used to belong to rich Quaker families with names like Evans and Livezy. There were once five covered bridges scattered along the creek, but mostly they were replaced by bridges, or just got washed away.

So, over the course of two centuries, the pioneers settled the woods, the civilization created a factory town in the middle of a peaceful city, and then the environment took it all back. Now we have a forest in the middle of a city, and rather more unemployment than we want. It isn't fair to say the environmentalists won, it just seems to be cyclic. So enjoy it while you can.

Originally published: Tuesday, March 05, 2013; most-recently modified: Friday, May 03, 2019