1 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

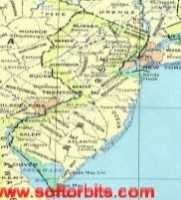

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

City Hall to Chestnut Hill

There are lots of ways to go from City Hall to Chestnut Hill, including the train from Suburban Station, or from 11th and Market. This tour imagines your driving your car out the Ben Franklin Parkway to Kelly Drive, and then up the Wissahickon.

Convention Center

|

| Convention Center |

A substantial grant from the Pew Foundation initially funded The Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation but expected other more permanent funding sources to materialize by the end of three years. The funding source turned out to be a 1% tax on hotel rooms since hotels were rather easily convinced that an increase of tourism to Philadelphia would benefit them. There is every reason to think the whole idea was a good one, effectively implemented. However, it probably was not completely appreciated that this hotel tax would provide a measurement, a public thermometer, of the ebb and flow of tourists to the city. Thus, the devastating effect of labor troubles at the Convention Center upon the hospitality industry became quite undeniable, hence became potent political medicine in the municipal political campaigns. Tax revenues from this specified source were down, and the causes became hard to deny. Philadelphia has long been a strong union town, but it will be decades before the public forgets the behavior of the carpenter's union or the economic havoc it inflicted on the second largest industry in the region. Even the most committed liberal ideologue would have to admit that the members of the carpenters union would achieve greater personal income by moderating their wage demands and restraining their work rules, working more hours at somewhat lower hourly wages. The argument has long smoldered whether Philadelphia is the most American of American cities, or whether it is the most European of American cities. A case can be made, either way. This labor dispute may not settle the basic question, but it will certainly shift the city's image toward one direction or the other because this matter is not one of architecture, cuisine or speech patterns. It's a matter of the city's belief system.

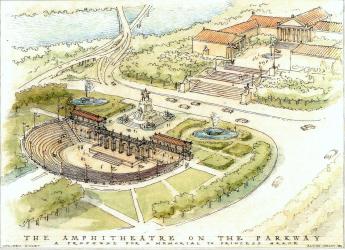

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (1)

|

| B. Franklin Parkway |

Philadelphia has straight streets and square blocks in all directions, by the hundreds. Just a few streets slant off at an oblique angle, and most of those, like Germantown Avenue, is following old Indian Trails. The one, cold-blooded, deliberate slant street is the Benjamin Franklin Parkway which essentially runs from City Hall to the acropolis holding the Art Museum aloft. Just whose idea it was is unclear, although the architect Horace Trumbauer gets most credit. The actual design was given to a Frenchman, Jacques Greber, presumably because it imitates the effect of the Champs d' Elysee in Paris -- a broad sweeping boulevard with lanes of trees along the side and in the medians. As things turned out, a simple idea was pretty hard to put into practice. First of all, plenty of people in Philadelphia don't like anything if it's French, and an even larger number don't like the idea of messing around with our nice traditional system of squares at taxpayer expense. The people who lived in the area were naturally upset to see the ends of blocks chopped off, destroying the corner property entirely and exposing the backyards of the neighbors to public view. At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, the Pennsylvania Railroad's Chinese Wall cut off the center of town from "North of Market" , and the Parkway thus created a triangle of desolation that could only recover when the Swan Fountain appeared, named

|

| Swan fountain |

after the President of the Philadelphia Fountain Society. The sculpturing was done by Alexander Stirling Calder, the son of the sculptor (Alexander Milne Calder) of William Penn atop City Hall. The original design made the mistake of planting all the trees as red oaks, and so most of them died of the same disease at the same time, requiring replacement with mixed varieties of trees that would not be so susceptible to epidemics. People were reluctant to live in the isolated triangle of land to the South of the Parkway, and also in the strip of land North of the Parkway up the steep hill to Eastern State Penitentiary on Fairmount Avenue. Accordingly, the land was filled with public buildings, including the semi-prison for adolescents, the Central Detective Bureau, and so on. The deep cut for the railroad spur connecting the Baltimore and Ohio (along the Schuylkill) with the Reading Railroad running out of 12th and Market, didn't help encourage people to raise their children in the area, either. And that wasn't all. The Swan Fountain was designed in such a way that you couldn't get underneath it to change a light bulb, so a set of tunnels had to be dug underneath the fountain plaza as an afterthought. Planting the plaza with Paulownia trees was a stroke of genius. Although the blue blossoms are only spectacular for one week out of fifty-two, the massive limbs are always striking, even in the dead of winter.The Rodin Museum

came along, and although it is a little isolated, is a grand display in the same spirit as the boulevard itself, including the modernist sculpture of Alexander Calder. There is talk of creating a museum on the Parkway for the three generations of Calder's, and even agitation to bring the Barnes Museum in from Merion. With the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Franklin Institute and the Art Museum itself, the boulevard is still growing and evolving.

When traffic is heavy, people just want to get home as fast as possible, but most of the time the Parkway uplifts the soul, just as it was intended to. It's an outdoor thing, not an interior one, and there is something symbolic about the famous movie run of Rocky, pounding up the stairs to turn, holding up his victorious arms, to a breathtaking view of the city. But remember, although now closely associated with the Art Museum, he never went inside.

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (2)

|

| Art Museum |

There are a number of residential relics along the Parkway, but in general the idea seems to have been to put governmental buildings there, in a sort of French-like celebration of governmental glory. There is the Youth Study Center, the Department of Education administration building, the Boy Scouts of America, the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, and of course the tower of City Hall at one end and the Parthenon-like Art Museum at the other. But this is Philadelphia, and certain small touches of the town are tucked among the European grandee design.

For example, WFLN (now WWFM) the original FM classical music station, had its studio tucked in a little building just behind the Cathedral. Ralph Collier would interview authors and city visitors there during the lunch hour, in a studio that was little more than a closet, while someone else changed records in a room downstairs. Somebody from New York once said that Ralph didn't seem to know how good he really was, which is a way New Yorkers like to talk. Ralph was, the just about the only interviewer who had actually read your book before the interview. In 1997, WFLN was sold for forty million dollars, which ought to impress even a New Yorker.

Logan Circle is bigger than it looks, primarily because the windows are set 100 feet high. This came about after the anti-catholic riots of the Civil War era, which made it advisable to put stained glass higher than most people can throw rocks. There is usually a cardinal in residence at this cathedral, and Cardinal Bevilacqua the much-respected lawyer-cardinal is now just retiring in favor of an incoming occupant from St. Louis. Cardinal Krol was famous in the past for his opposition to Pope John's Vatican Constitution, which he refused to allow to be translated into English. Before that, was Cardinal Dougherty, who is remembered for being considerably overweight. Cardinals are addressed as Your Eminence, and Cardinal Dougherty was (very privately) referred to as You're Immense. He was perhaps most famous for the Legion of Decency , an effort to make motion pictures more socially acceptable. The story is told of a 12-year-old girl who stood up and told the Cardinal that she didn't agree with him, she liked movies. The next day, her father, the most powerful Catholic banker in Philadelphia, had to go to the Cardinal and humble himself to make amends.

|

| Amelia Earhart |

Franklin Institute was originally on 7th Street, where the Atwater Kent Museum of Philadelphia History is now located. Much of the money to build it came from a $5000 bequest from Franklin himself, which was intended to demonstrate the power of compound interest over a period of time. It is part science museum, part memorial to Philadelphia's most famous citizen. It has a Planetarium, locomotive, a passenger airplane, Amelia Earhart's plane, a huge replica of a human heart, and thousands of working demonstrations of electrical phenomena. Ben Franklin's huge statue sits in a grand marble rotunda, where socialites occasionally hold receptions and weddings. But between the two extremes is the most interesting combination of museum and memorial -- a series of demonstrations of Franklin's most important scientific discoveries, utilizing the same instruments he used. Just a little effort at understanding these exhibits will convince any educated adult that Franklin was truly a genius.

Almost next door to the Franklin Institute is its more venerable neighbor, the Academy of Natural Sciences. The Academy is an offshoot of the American Philosophical Society, itself (originally founded by Franklin) and has a distinguished history of discovery and research of its own making, not merely a display of the work of others. Most school children will recognize the famous display of dinosaurs, including the First Dinosaur ever unearthed intact (in Haddonfield).

|

| Art Museum |

The Art Museum was intended to inspire awe, and it does. The builders ran out of money before the decorative friezes could be completed, but that even enhances its resemblance to the Parthenon, where the friezes were blown off in various wars. It's a little hard to know how to respond to the criticism that the building overwhelms its contents. Perhaps it is true that the creaking floorboards in Madrid's Prado Museum show off the treasures on its walls, but there is also little doubt that Spain (or Boston) would replace the floors if it could afford to. Although the City of Philadelphia has a little trouble finding the money to maintain and guard the Museum, the masonry is ultra-solid, it's very big, and will endure for ages to come. The collections slowly grow, benefaction by benefaction. The traveling exhibits are clearly the center of Philadelphia culture. And there, at the top of the stairs without any clothes on, is Diana of fame and fable. Her perfectly straight back is the true essence of the famously beautiful Philadelphia woman, like Fannie Kemble, Rebecca Gratz, Evelyn Nesbitt,Cornelia Otis Skinner, Grace Kelly, and Katherine Hepburn.

The Barnes Foundation: Comments on the Economics of Art (2)

In 1951, Albert C. Barnes' legacy included Jerome's Epistle to Paulinus from the Gutenberg Bible education centered on a notable collection of illustrative artworks, housed in a museum of his own general design for the purpose. He left a multi-million dollar endowment to support his rather detailed and, in the opinion of many, somewhat eccentric intentions. It was his money, however, so his word was final. The institution was fairly mature, having previously been in operation under his direct control for twenty-five years.

Since the Foundation trustees are now before the Orphans Court pleading for permission to modify Dr. Barnes' instructions in order to avoid financial collapse, skepticism is inevitable. Obviously, the successor trustees must explain their expenses. But quite a plausible case can be made that the true cause of this disaster is inherent in the huge windfall growth in value of the paintings. In short, growth in value of the fine art may have outstripped the growth of the resources set aside for maintenance.

|

| Johann Gutenberg, creator of mass produced books, died in poverty |

Let's make a benchmark of the Gutenberg Bible, where incomplete copies are currently selling for $100,000 a page and complete copies are estimated to be worth $100 million apiece. Dealers maintain the Gutenberg is increasing in value at 20% a year, but growth seems closer to 9% a year if you go back to 1951. What's really relevant here is the growth in cost to ensure, protect, dehumidify, display and make it available to scholars, if not the public. It seems safe to guess these maintenance costs have grown more rapidly than the investment growth of the endowment, which is surely closer to 4% than 20%. The imbalance is even greater if you remember that some investment income is spent every year, while the worth of the fine art just grows and grows. Regardless of the true numbers, if the cost of maintaining the art does grow even slightly faster than the endowment, the dilemma the Barnes is now facing will eventually face any museum. New sources of revenue, either from the government or from public admissions, eventually becomes necessary if the priceless art remains on display. It is displaying these things that cost money; burying them under an Aztec mound or a German salt mine shelters them from the problem. In the case of Alfred Barnes, it is not completely certain that he wanted them displayed.

There is also the issue of quirky fluctuations in the market for fine art. The 22 known perfect copies of Gutenberg, Bibles have been around for almost five hundred years, and it is safe to say their value is enduring. The 180 paintings by Renoir now owned by the Barnes may prove to be Gutenberg Bibles or they may prove to be a passing fad, but it is pretty hard to believe that one of them will always be worth two Gutenbergs. Since there is a pretty fair chance that we are currently seeing a value bubble in French Impressionist painting, it is questionably prudent to shipwreck the whole Barnes Foundation, the School, or Albert C. Barnes basic intent, by resisting the sale of even one of the more overpriced examples in the collection at the top of the market.

That's one side of it. Another consideration is that Barnes himself did considerable merger negotiation with other museums, and may have been unexpectedly killed in an auto accident before he turned over all his cards in that particular poker game. It's asking a lot of the poor judge to overturn the clear and largely unmistakable language of Barnes will in favor of theories about what Barnes was really really thinking when he wrote it. If the judge is feeling adventurous, it's probably more satisfying to all parties if he sets forth a new legal doctrine, reflecting the inevitable disparity between the cost of displaying fine art to the public, and providing a perpetual endowment to do so.

Geckos: Academy of Natural Sciences brings Mini Dinosaurs

|

| Gecko |

FRIENDS who spent time in Vietnam have a lasting memory of lizards stuck to the ceiling, catching flies with their tongues. Those animals are named geckos, one of the oldest and probably most varied families of reptiles, but confined to the Southern hemisphere. Fossils have been found containing geckos from fifty million years ago, so they were here before the big dinosaurs were wiped out, when the Yucatan was probably struck by an asteroid.

|

| Anthony Geneva |

There was a time when Africa, India, South America and Antarctica were united in one monstrously big continent, and the many varieties of gecko are scattered over the land masses which originally made that up. At least this is the way Anthony Geneva explains it to visitors to the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th and Ben Franklin Parkway. There are no geckos to be found naturally in Philadelphia. Philadelphians hardly need reminding that the first dinosaur bones, ever, were discovered in Haddonfield NJ, and were soon taken to the Academy for permanent display. Ever since that time, the Academy's collection of dinosaurs has expanded, and are the things with the most impact on school-age visitors. The Academy is getting ready to celebrate its 200th anniversary in a few years, however, and contains much more than dinosaur bones, including extensive research facilities with world-famous scientists at work in them. In any event, the dinosaur image is a clear metaphor for the present display of little reptiles that look like dinosaurs, whatever the DNA trail may be. The main exhibition area is currently filled with dozens of glass display cases containing live geckos, and the little rascals are so good at camouflage that you have to hunt carefully for them before they suddenly seem to emerge from the shadows. There are white ones, black ones, bright green and bright orange ones, speckled in all sorts of weird patterns. They make sounds resembling bird songs, and the term gecko is a native word referring to such sounds. The Academy displays these gecko-noises for visitors who are invited to push twenty or so buttons. Geckos move, but suddenly, and probably for some predatory purpose. If you are really into geckos, you focus on their feet.

|

| Gecko |

The variety of toe and foot shape is almost infinite and seems more so if you have a magnifying lens. The foot pads terminate in different kinds of extremely fine hairs, and that's their big secret. Those hairs are so fine the molecules of the foot and the molecules of the wall or ceiling attract each other magnetically. Since no energy is expended in the adherence, the gecko can remain attached to a wall or ceiling indefinitely, even after the gecko dies. But, by raising the angle of contact to thirty degrees, the foot detaches, and the little rascals can scoot along very rapidly, upside down. At present, there is a great deal of commercial and maybe military interest in clarifying the secrets of this adhesion. To be industrially useful, the footpad size would have to scale up to much larger dimensions, but just imagine gluing together the vessel ruptures and aneurysms inside the brain as we now do in a cumbersome manner with chicken-wire stents, just one example that quickly occurs to a visitor. If these little fellows figured out how to make these reversible adhesives fifty million years ago, our scientists ought to be able to imitate them.

Drop around to visit the Academy. It's filled with amazing things like this.

Fair Mount

|

| THE FAIRE MOUNT |

Although the Art Museum now dominates the end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the earlier focus of the acropolis once called Fair Mount is just down the hill behind it, in the old Grecian complex of the Philadelphia waterworks. When the Schuylkill was dammed at that point, the effect was to calm the rapids, drown the falls at Midvale Avenue upstream, and turn this portion of the river into a placid fresh-water lake. Fairmont Park was then created upstream in an effort (originally stimulated by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia) to reduce pollution of Philadelphia's water supply going into the pumps at the Waterworks, by replacing, with parkland, the wards, and industrial slums at the terminus of the canal bringing anthracite from upstate. The result was the creation of an ideal place for public boating and skating.

The transformation of this area can be seen in retrospect as an impressive civic response to economic upheaval. The War of 1812 (by cutting off ocean access to bituminous via the Chesapeake) had first forced Philadelphia to use anthracite hard coal, and the discovery of anthracite's superiority in making steel caused a continuing reliance on it and the canals

|

| Philadelphia's Water Works |

that brought it here. By 1850, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad made the canals obsolete and created this splendid opportunity for urban renewal. The waterfalls had created a natural boundary between industry oriented to upstate coal and other industry oriented to oil and commerce coming up Delaware. It is a great pity that the lower section of the Schuylkill, once so famously beautiful, has never stimulated the same vision and imagination in response to the eventual decline of the industrialization which defaced it.

To return to Boathouse Row, a large azalea garden starts the Park, and then the East River Driver winds along the attractively landscaped riverbank. Just beyond the azalea garden, the first of ten Victorian-style boathouses starts the home of the Schuylkill Navy, an association of rowing clubs which are now a century and a half in residence there. When the Schuylkill auto expressway was created on the other side of the river, someone had the bright idea of decorating the rowing houses with lights along their edges in the manner used for Christmas decorations in South Philadelphia, especially on Smedley and Colorado Streets. Ever since the entrance to Philadelphia from the West has become one of its most arresting beauties.

|

| BOATHOUSE ROW |

Add a few cherry blossom trees in the spring, and you have quite a memorable centerpiece. Rowing sometimes called crewing, or sculling, is a central focus of Philadelphia society, and is curiously not something in which the city can claim to be first or the oldest. As you might expect, "regatta" is a word invented in Venice five hundred years ago, there are records of rowing races as far back as 400 BC, and New York -- ye Gods! -- had the first American boating club. The Philadelphia Schuylkill Navy was formed as an association of rowing clubs in 1858, and the oldest member, the Bachelor's Barge, was only formed in 1856. The development was largely spontaneous and is said to have been briskly stimulated by a beer garden nearby, run by a former Philadelphia sheriff. About the same time, the British became crazy about the sport, having the Henley Races as the most famous regatta in the world, and both the Australians and the Bostonians occasionally have the largest, most expensive, most widely advertised regattas. Foo. Philadelphia has the Schuylkill Navy, and it is central to our existence.

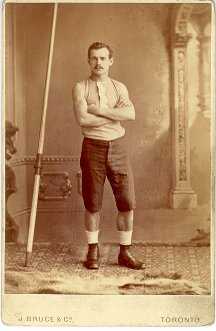

There are a couple of things which are unique about rowing. In the first place, it is hard to think of a way to cheat. You can hire engineers to redesign the shape and size of your boat, but engineering really doesn't make a lot of difference once the basic development of oarlocks and movable seats was perfected. A good boat can cost as much as $30,000, but that is large because all boats approach the limit of speed. If you have heavier or stronger oarsmen, it doesn't make that much difference. What matters is coordination, and in the longer boats, teamwork. Pull up with your shoulders, push with your legs, don't start with your buttocks, the art of rowing involves your whole body. The greatest champion of all time, Edward "Ned" Hanlan,

|

| EDWARD HANLAN |

only weighed 155 pounds. Not only was he world champion from 1876 to 1884, he was undefeated in any race during the last four years. True, he was born in Toronto, and eventually he was thrown out of polite Philadelphia racing for deliberately ramming another boat, but those are private Philadelphia comments, not something you want to talk too much about. The whole secret of rowing is to manage the fact that the boat travels farther between strokes than while the oars are in the water; if you row too fast, you actually slow the boat. There are two other Philadelphia names associated with the Schuylkill Navy. One is Thomas Eakins, the great American painter, one of whose most famous pictures is that of Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (on the Schuylkill). The other name is Kelly.

John B. Kelly of Philadelphia won two Olympic gold medals in 1920 and did it within one hour. He won a Third Olympic gold medal in 1924. But when he tried to race in the Henley Regatta, he was declared ineligible to row, because he had worked with his hands (summer work as a bricklayer), and thus could not really be called a gentleman. Anyone who has ever heard Irishmen talk about Englishmen can imagine the reaction this caused in the Kelly family. The resentment took the form of pushing his son, Jack, into racing, and in 1947 John B. Kelly, Jr. won the Diamond Sculls at Henley. Meanwhile, the father vindicated himself in other ways. The firm of Kelly for Brickwork was an enormous financial success, right up there next to Matthew H. McCloskey and John McShain, the political builders of the Pentagon and numerous other government buildings. John B. Kelly unsuccessfully ran for Mayor of Philadelphia in 1935 during the 75-year period when Philadelphia Mayors were always Republicans, but for decades was in the much more powerful position of head of the local Democratic party. The Republicans at that time would meet for lunch at the Union League, and so John Kelly reserved a lunch table at the Bellevue Hotel, next door, where he could be seen holding court every day.

|

| John B Kelly |

The result was not entirely favorable for the Bellevue; more than one wedding reception was rescheduled to some other hotel in order to avoid the Democrat taint. But you always knew where you could find Kelly at lunch, and it was fun to watch the various minions come forward to the table, almost as if they were in chains, to pay homage which involved provoking loud laughter from the great man with a salacious joke. The rowing clubs are mostly big barns with old boats high up on the walls, and silver cups and wooden memorial plaques lower down. They have lockers and showers, but no dining rooms, except at catered in the evening for parties. For a century, no women came there, but now almost half of the rowers are female. Membership is not difficult to obtain, although you have to be good to get on the club teams, and the dues are not expensive. If you show promise, you are expected to spend most of your waking hours working at it. Jack Kelly was famous for rowing three hours every morning, going to lunch, and then coming back for a couple of hours of more rowing. That doesn't leave much time in your life for anything else, so the friendships developed among active club members are very strong, just like the horsemen over at the City Troop. They sort of life in the past a little, with many anecdotes about a skull that broke apart and sank in the midst of a race, or a race that was lost because of too much recreation the night before. The lingo has to do with the fine points. A race can be between "eights" or "fours", or doubles, or singles. It can have a coxswain, or not, and be coxed or unboxed. When a pair of rowers have two oars apiece, it is the normal arrangement. A much more difficult boat to control has two rowers, with one oar apiece. Like Hercules or Achilles, stories are told of Hanlan, great Hanlan, who sometimes would win a one-mile race by eleven lengths. Or who would get so far ahead of his competitors that he would lie down in the boat and wait for another boat to catch up -- and then race ahead to beat him. This sort of person can be a little hard to take, and it is privately muttered that Hanlan was sent off to Australia, where people do that sort of thing more commonly.

One Big Brewerytown

|

| Rich Wagner |

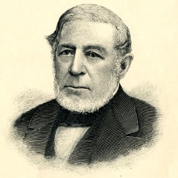

RICH Wagner, the author of Philadelphia Beer, recently visited the Right Angle Club. It's hard to imagine that Philadelphia was once the American center of beer production, with hundreds of breweries and their associated bottlers, beer gardens, brewing equipment, and horse-drawn beer delivery systems, dominating the city scene. Equally hard to imagine that the last Philadelphia brewery closed in 1987, and the biggest American brewer, Budweiser, was sold to the Belgians in the past year. What's this all about?

|

| Francis Perot |

In the early wilderness days, water supplies were tainted and unsafe, so most prosperous Quakers had their own little brewery just to avoid typhoid fever. The first American brewery was started by Anthony Morris (the second Philadelphia Mayor) in 1687, in a little brewery on Dock Creek, which became the early Brewerytown of the city, with several dozen brewpubs for sailors and the like. In 1797 there were over a hundred breweries in Philadelphia, and in 1840 there were over three hundred of them. Perot's brewery was prominent for a long time since an early Perot married a daughter of Anthony Morris. Since Philadelphia developed the first and famous city water supply in 1800, beer drinking lost its position as a safe beverage in an unsafe city, and gradually water-drinking became the dominant beverage for the strict and upright. At one time in the early Eighteenth century, gin was cheaper than beer, so even the intemperate multitudes deserted beer for a while, although the effect of the higher alcohol content of gin was apparently fairly dramatic.

|

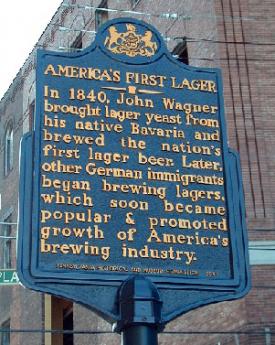

| John Wagner Marker |

In 1840 John Wagner imported the yeast for lager beer from Bavaria, at considerable personal risk if he had been caught at it. Prior to 1840, Philadelphia beer was either stout or Porter, a very dark and bitter dose, or else ale, which had the advantage of storing fairly well and thus was popular for sailing vessels and among sailors. The yeast for ale floats to the top and ferments, whereas lager yeast sinks to the bottom of the barrel and requires some refrigeration to slow it down. In all forms of beer, the suds are created by later adding some unfermented beer to the barrel for the purpose of generating carbon dioxide. That's what is going on when you see the bartender in a British pub pulling on a lever to pump it up from the basement. Lager tastes much less beery than other beer and is by far the dominant form of beer in consumption -- a considerable improvement, in the view of most people. But it has to be cooled, and Philadelphia had a system. Brewerytown moved to Kensington, dominating the local scene. It was produced in barrels which were trucked to the east bank of the Schuylkill where ice formed on the surface of the river, stilled by impoundment above the Fairmount Dam. Caves were dug in the banks of the Schuylkill where the barrels full of fermenting beer were hauled to be cooled by the ice for the rest of the process. From there, it was trucked again to bottlers in a general ratio of one brewer for thirty bottlers. More directly, it was trucked to the beer gardens of Spring Garden to Girard Avenue, which gave that area a different sort of reputation as a brewery town. By this time, most of the breweries had moved to the region between 30th and 33rd Streets, near Girard, and most of them still survive, made into condominiums by rehabilitation money. One by one, many sections of downtown Philadelphia acquired a beer environment. A dramatic moment in this process was the advent of the 1876 exposition, which caused many of the Schuylkill fermenting vaults to be acquired by eminent domain. A second momentous change was introduced by the invention of refrigeration, apparently invented in Germany near Berlin, but imported and refined by York and Carrier. Philadelphia was particularly suitable for the importation of coal to fuel the heating of the brew, and the chilling of the fermentation. All of this required large numbers of brewers, bottlers, makers of bottles and inventors of brewing equipment. It took many horses to haul all this material around town, and many teamsters to drive the horses. This was a beer town, until Prohibition.

During the long period of beer ascendency, the advantages of big breweries over small ones were gradually making this a major industry, rather than a local craft. Prohibition completed the destruction of the small craft brewers and brew-pubs. Only 17 of the major brewers survived Prohibition, and then even the big ones went out of business, ending with Schmidt's in 1987, almost exactly three hundred years after the first little one started by that famously convivial Anthony Morris on Dock Street. Evidently, the same competitive disadvantages continue as even Budweiser moves to Brussels, where you would ordinarily expect the wine to be the popular drink. Changing tastes have been cited as the reason for this shift, but differential taxes seem more probable as an explanation. In most industries, you are apt to find that most of the competition takes place in Washington and Harrisburg, rather than the saloons of Main Street or the salons of Madison Avenue. But perhaps not. We hear that little Belgium is about to have a civil war because the Flemish can't get along with the Walloons. And somebody in Portland, Oregon got the idea that beer was trendy, and started up the growing phenomenon of craft brewers, usually flourishing in brewpubs. We are apparently going back where we started in 1687.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in the Cradle of Liberty: Rich A. Wagner: ISBN: 978-1609494544 | Amazon |

The Houses in the Park

|

| Strawberry Mansion |

Fairmount Park is said to be the largest park (7000+ acres) within the limits of an American city, and in fact, maybe just a little bigger than the city can afford to maintain. It was established in the middle of the 19th Century through the efforts of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to reverse the Industrial Revolution's relentless pollution of Philadelphia's Schuylkill River and the water works. The waterworks were built in 1801 in the mistaken belief that Yellow Fever was caused by pollution; Fairmount Park more accurately responded to the idea that Typhoid Fever was waterborne from upstream pollution. Lemon Hill, the nearby mount containing Robert Morris' Mansion, was purchased to expand the reservoir capacity of the waterworks and thereby made the Art Museum possible where the reservoirs were originally located.

The Park has long constituted a symbolic interval between center city and the suburbs. Since the construction of the river drives and later the expressway, the commute along the river amidst trees and parkland has made an entrance to town a pleasant experience. If the town planners had been able to foresee automobile commuting, they might have anticipated that the sun would be in the driver's eyes coming East during morning rush hour, and in his eyes as he went home toward the West in the evening. Driving safety might perhaps have been impaired by the tendency of this glare to direct attention to the park rather than straight ahead, but nevertheless redoubles the effect of the park views as a daily aesthetic experience. Even the pollution idea had its ambiguous side since animals increase the bacterial runoff from their grazing areas, and the original houses in the park had many pastures. Strip mining, however, allows mineral contaminants to be washed by rain into the watershed. The city waterworks today extract nearly 800 tons of sludge from the water supply, daily. Whatever the effect downstream, the high ground had less malaria and less typhoid than swampy lowlands, so many of the original houses were useful summer retreats for city dwellers during the early years of the city.

The park is governed by the Park Commission, and at one time had its own police force, the fourth largest police force in the state. Started in 1868, the Park Guards changed their name to the Park Police and then became part of the Philadelphia Police in 1972. The original 28 officers had grown to 525, had their own police academy and a proud tradition. It seems very likely that some deep and dirty politics were played in this shift of authority, and it might be a fair guess that some bitterness still survives in the circles who know and care about these things. In 2008 a scarcely-noticed rule change gave the Park to the City Department of Recreation, thus placing it just a little closer to ambitious real estate development. Our present concern, however, is with the houses in the park.

There are seven of them, kept up and maintained by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Guided tours are provided intermittently by the museum, but since funds are limited only three of the houses are open year round. The others are equally worth a visit but unfortunately, are closed during the height of the spring flowering season. Two of the year-round houses represent the two extremes of Philadelphia culture, since Mount Pleasant was owned by a buccaneer ("privateer") named McPherson who lived at the height of 18th Century elegance, while Cedar Grove was originally a Quaker farmhouse of the greatest simplicity consistent with honest comfort, a style which persisted relatively unchanged until late in the 19th Century. Benedict Arnold and Peggy Shippen looked at Mount Pleasant with an eye to purchase but never lived there because they were called away by national events. With the addition of modern plumbing and air conditioning, Mount Pleasant would be an elegant place to live, even today. McPherson had to sell the place to pay his debts, whereas the Wister and Morris descendants of Cedar Grove still populate the Social Register in large numbers. The two houses completely typify the underlying philosophies of the two leading Philadelphia classes of leadership. One group measures itself by how much it spends, the other group measures success by how much it has left.

REFERENCES

| Treacherous Beauty: Peggy Shippen, the Woman behind Benedict Arnold's Plot to Betray America: Mark Jacob:978-0762773886 | Amazon |

Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold: Fallen Idols

|

| General Burgoyne |

After defeating Washington's troops at the battle of Germantown, the British then occupied Philadelphia for the better part of a year. The town was a mess, with food shortages typical of the squalor of any occupying army equalling the existing population. Washington was forced to fall back to the natural fortress of Valley Forge. The city of Philadelphia was not exactly under siege, but it was as difficult a place for British troops to live as a besieged city. For his part, Washington was forced to shiver and starve in the nearby mountain valley, at least consoled by distant news of American achievements. General Burgoyne and his army were soon captured at Saratoga by General Gates under humiliating circumstances. Clearly, the dashing hero of this event had been Benedict Arnold on a white horse leading the charge, getting wounded in the leg in the process.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in Paris |

Benjamin Franklin in Paris trumpeted the news of this victory, reminding the French of Washington's earlier victory at Trenton, and maneuvering it all into a treaty of alliance. With the French fleet in the nearby Caribbean, Philadelphia was no longer a safe place for the British to stay a hundred miles upriver, and the idea of abandoning occupied Philadelphia began to grow. Having gambled on British victory in defiance of London's orders, the Howe brothers were not in a position to argue with new orders. The British soldiers inside the city were more comfortably housed than the American troops outside it, but nobody was exactly comfortable. The American Congress had, of course, fled to the hinterlands. All in all, it suddenly became uncertain who was going to win this war.

|

| Peggy Shippen |

The American population at this time has been described as a one-third rebel, one-third Tory, and one-third trying to hunker down to see who would win. Many of the seriously committed Tories had fled from Philadelphia when the rebels took charge, while pacifist Quakers were a little hard to classify. Generally speaking, the prosperous merchant class had never been persuaded King George was all that bad, while the less prosperous artisans were the fervent patriots. Under such conditions, many people who privately leaned in either direction found it was best to seem non-committal. The British were billeted in private homes; the Officers in the best houses of the merchant class, the common soldiers generally housed in the homes of the artisans. Although the soldiers and the artisans did not mix very well, circumstances permitted the aristocratic officers getting on pretty well with the merchants whose houses they occupied. The girls in the colonial families seemed immediately attractive to the British officers, who were far from home, while the officers also seemed pretty glamorous to the girls. So, it is not exactly surprising that the most beautiful colonial belles like Peggy Shippen and Peggy Chew found themselves frequently in company with dashing officers like Major John Andre. Andre would likely have been a heartthrob in any circumstance since he had risen to the rank of adjutant-general at a young age, wrote poetry and plays, reputedly was rich, and was regularly the life of any party. Nor is it surprising that generations of Peggy's descendants have treasured a lock of his hair.

|

| Margaret Oswald Chew Howard |

When the decision was finally made to abandon Philadelphia, six of the British officers personally contributed twenty-five thousand dollars to throwing Philadelphia's most famous, most splendiferous party, called The Machianza. It went on for days, had real jousting matches between officers dressed like knights in armor, banquets and all that sort of thing. It was Andre's idea, and he was enthusiastically in charge. Surviving records of the event do not show that Peggy Shippen was present, but in view of what happened later, much of her correspondence has been destroyed. It's pretty hard to imagine she wasn't there.

|

| Major General Benedict Arnold |

The British then marched away, and Washington's troops cautiously followed, assuming control of the city. Major General Benedict Arnold had been sent from Saratoga to Valley Forge to recover from his leg wound, and probably also to raise morale among the troops celebrating the now-famous hero. Washington more or less immediately decided to pursue the British across New Jersey, thus leading to the battle of Monmouth as the two armies raced for the Naval vessels in lower New York harbor. Since General Arnold had not fully recovered from his wounds, he was installed as the military governor of a somewhat bedraggled Philadelphia. Naturally, he was the center of the social scene, and soon was pursuing Peggy Shippen in every way he knew, which included some pretty gloppy letters in Romantic style. Peggy's father was uneasy about his intentions but was eventually mollified by Arnold's purchase of the house called Mount Pleasant, now a tourist attraction in Fairmount Park. With this evidence that his prospective son in law was at least likely to stay in Philadelphia, Edward Shippen finally repented of his opposition to the marriage of his daughter. But the new couple were soon off to West Point, where Arnold had kept up a persuasion campaign with George Washington, to get himself appointed the commandant of the main northern defense of the Hudson River. A point for Philadelphian tour guides to remember is that Peggy and Benedict never got a chance to live in Mount Pleasant.

Arnold originally lived in New Haven, Connecticut, where he had established quite a sea-faring reputation as a merchant, some would say privateer, others would say buccaneer. There is no doubt he was aggressive, and combative, and considered himself a little bit above the law. These qualities made him outstanding at Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga, and are always more highly valued in young men in a war. Unfortunately, he made a bitter enemy of Joseph Read who was briefly his neighbor, and later was President of the Continental Congress. Read accused Arnold of smuggling and trading with the enemy, and was so determined about it that Arnold was scheduled for court-martial, but postponed. Arnold was loudly defensive about the whole matter, and public sympathy was on his side. In view of what soon happened, he might well have been cleared by the court, but likely there was some truth to the accusations. Using Peggy as a go-between, he entered into a correspondence with Andre (then the adjutant-general in New York) offering to deliver the surrender of West Point, three thousand prisoners, and possibly George Washington himself in return for what might today be half a million dollars. As a note of realism, he was willing to accept half that in the event of failure. The British were particularly anxious to acquire American prisoners to exchange for their own troops captured at Saratoga. Unless Arnold was a total sociopath, he must have thought he had quite a grievance.

|

| Lord Cornwallis |

Things went along surprisingly well at first, with negotiations for price back and forth, plans for attacking West Point moving along with the Navy, and Andre disguising himself for a visit to Arnold in his house to the south of the Fort on West Point. Much of the success was due to the movie-star reputation of Benedict Arnold; few could imagine such a hero doing such an unheard-of thing. However, the plot was discovered while Washington was away visiting the Fort, and Arnold hastily abandoned his family and fled to a waiting British warship. Andre decided to make his way south to the ship through rebel territory, but local soldiers and farmers were much more suspicious than others had been, and after penetrating his disguise, found incriminating papers concealed in his boots. Since he was out of uniform behind enemy lines, Andre was by definition a spy, which required hanging. He made a plea to be shot like a gentleman, but Washington with tears allegedly in his eyes refused. With much bravado, Andre jumped atop his own casket and placed the noose around his own neck, a behavior much admired by his compatriots when they heard of it

Meanwhile, Peggy had put on a crazy-woman act which apparently convinced Washington to be lenient, and allow her to rejoin her husband. The couple stayed in New York for a few months, toying with commands of loyalist troops in the south, but eventually taking ship for England. Lord Cornwallis was on the same ship and they became pals as shipmates, pleasing Arnold quite a lot. Unfortunately, British society was only stiffly polite to them, and many did not trouble to conceal their disdain for traitors to any cause, and thus life in England was not smooth. By that time, it is possible that many had begun to suspect the whole idea of treason was Peggy's idea from the start, as is today the conventional view of it. As an American aristocrat, she was uncomfortable with the rebels in Philadelphia, and as the impetuous wife of an accused smuggler, it was difficult to fit in with either the Quakers or the merchants with loyalist leanings. No doubt she heard some catty whisperings among her friends and relatives about her other romantic associations. The British paid them their promised pensions, but a career in the British Army was out of the question for her husband. But the real shock would come, from discovering the British as a whole didn't much care for their behavior, either.

The Man Behind the Mann

|

| William Leonard |

William Leonard, a distinguished lawyer retired from the distinguished firm of Schnader, Harrison Segal and Lewis addressed the Right Angle Club recently about his adventures running the new and improved Mann Center in Fairmount Park. A member of the board, he was suddenly asked to act as interim CEO when Peter Lane went on to another career. His task was to hold the organization together, while a permanent replacement was recruited. It turned out that directing an organization and actually running it are two entirely different things. It was necessary to learn about show business programming, the problems of rock groups, the whims of donors, the headaches associated with food vendors, and lease renewals with city governments, not to mention the rigidities of state and federal rules. Leonard obviously enjoyed the challenge, although most of us wouldn't.

The Philadelphia Orchestra had been playing summer concerts in the park since 1930, eventually adopting the name of Robin Hood Dell, East. Although the city contributed a couple hundred thousand dollars of support, and several hundred thousand other dollars came from non-ticket sales, classical music was always a long way from breaking even. The big revenue came from Rock Concerts, which may have been humiliating for the classical musicians of international fame, but was nevertheless what it took to survive, take it or leave it. Fred Mann in 1976 took the lead in raising funds for a roofed outdoor performance center, and the enormous energy of Peter Lane was brought from the New York Pops to get things going. In ten years, the Mann Center increased its outside support to $2.8 million of the $8 million annual budget and was putting on forty performances a season, with attendance increasing by 20% from 2006 to 2007. All this was accomplished in spite of the city government dropping its contribution to zero, and dropping music courses in the school system.

In a sense, the city stringencies may have been a blessing for the Mann. A second capital campaign raised $15 million for expanded facilities and parking, as well as an education center, to meet the new community need. A complimentary ticket program distributes 50,000 free tickets yearly, and seats on the lawn cost $10. If you want to get under the roof, it costs more. The free program familiarized parents with the program, and the educational center is now thriving.

Mr. Leonard brought along the new CEO, Cathy Cahill, and it looks as though he made a good choice. She's only been here for 19 days, but she went to Temple and Drexel before taking jobs out of town. She's a cellist herself, which should ease labor relations somewhat, although the pep and enthusiasm are surely innate. We hear that SEPTA is planning to re-open the R-5 station, and jitney bus service for the whole Park complex will be shared with the Please Touch Museum and other new activities in the 1876 exhibition area. There are plans for a Shakespeare repertory group to have a home here. This drive and enthusiasm are going to be necessary because Rock Groups are now competing in the Wachovia Center, and the Tweeter Center in Camden. Apparently, the secret of classical music finances leaked out.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1479.htm

Hidden River

.jpg)

|

| Schuylkill River |

In Dutch, Schuylkill means "hidden river", thus making it redundant to speak of the Schuylkill River. As soon as you become aware of this little factoid, you start to come across Philadelphians who do indeed speak of the Schuylkill in a way that acknowledges the origin of the term. To give it emphasis, it is common to speak of the "Skookle". The point comes up because cruises have started to leave from the dock at 24th and Walnut Streets, where it becomes quite noticeable that the Schuylkill really is rather hidden as it winds seven miles south to the airport, in contrast to the wide-open vista we all are accustomed to seeing from the Art Museum northwards.

The bluff at Gray's Ferry, where the University of Pennsylvania's new buildings now dominate the scene, was originally the beginning of dry land, or the end of the rather large swamp, through which the river winds its way essentially shaded by trees along the riverbank. Never mind the junkyards and auto parks you happen to know lurk behind the trees on the west side or the oil tanks which loom above the trees on the south bank. As evening closed in on the riverboat, the gaily lit towers of center city were looming in the stern, but some fishermen along the bank proudly held up a respectable string of six or seven rather large catfish. If you are there in the evening, the river has the same feeling of wilderness that the Dutch traders would have experienced three hundred years earlier. No swans, however. There were many reports in the Seventeenth Century of large flocks of swans sailing around the entrance of the Schuylkill into the Delaware River. A noted local ornithologist on the recent cruise remarked that forty or fifty species of birds are found there. Even a flock of owls still live within the city limits. You don't see owls, even if you are an ornithologist; their presence is made known by taking recordings of the sounds of the night.

|

| Fort Mifflin |

The geography of swampy South Philadelphia was created by the abrupt bend in the Delaware River at what is now thought of like the airport region. As the river flows at the bend, sediment is deposited in mud flats that once created Fort Mifflin of Revolutionary War fame, and later Hog Island of the Naval Yard, home of the hoagie. Swans are beautiful creatures, but they seem to like a lot of mud. The lower Schuylkill is tidal, and the industrial waste of the region is cleaned out of the land by cutting drainage ditches laterally from the river, flooding the lowlands as the tide rises, and draining it again as the tide falls. This cleansing seems to be working, as judged by the return of spawning fish. And maybe mosquitos, as well, but it would seem rude to inquire.

The Bartram family seems to have known how to make use of river bends and riverbanks, placing the stone barn and farmhouse higher up the bank, but below the bluff of Gray's Ferry forces a bend in the Schuylkill, below which of course flatlands were created. It's a peaceful place, now made available for tours and excursions by placing a landing dock on metal pilings so that it can ride up and down with the tides. The great advantage is that riverboat landings are no longer restricted to two a day, at high tide, with limited time to visit before the tide falls again. Bartram recognized how popular strange plants from the New World would be in England, and his exotic plants were quite a commercial success. Nowadays the big sellers are Franklinia Trees, available the first week in May. The last Franklin (named of course for his friend Benjamin) ever found growing in the wild, was the one John Bartram found and nurtured. Every Franklinia is thus a descendant of this one. They look rather like dogwood but bloom in the early fall. If it suits the fancy, a dogwood next to a Korean dogwood which blooms in June, next to a Franklinia, can make a continuous display of bloom from May to October. And best of all, no one will appreciate it, unless they are in the know.

Waterworks

|

| Justina Barrett |

Even to those folks who've been to the Water Works in Philadelphia, it may come as a surprise to hear that, in the late 1800s, this neo-classical gem sitting on the Schuylkill River behind the Philadelphia Museum of Art was the second most-visited attraction to out-of-towners in the whole U.S., second only to Niagara Falls. Justina Barrett of the education department of the art museum was an endless source of historical information for the Right Angle Club luncheon attendees yesterday in her engaging talk of the history of one of my favorite places in town.

Back at the end of the 1700s Philadelphia's source of water was primarily the Schuylkill River which was then a pristine stream whose water was clear and refreshing. In spite of this an epidemic of yellow fever swept through the city in 1799 and wiped out a quarter of the city. It wasn't the river itself that was at fault. At the time the water supply facility was located where City Hall presently sits. Water was pumped to a reservoir nearby and this was the source of pollution. Not only was the reservoir unclean, but it was also tiny, having a reserve of just 25 minutes at the rate of use. This wake-up call was answered with plans for an entirely new facility right on the Schuylkill using all the latest technology of the time (did they have "technology" back then?). Besides being convenient to the source of water, a new reservoir alongside was remote from the sources of pollution of the city, which extended only to about the area of present-day 13th street.

|

| Frederick Graff |

The new facility, designed by Frederick Graff and John David, was begun in 1819 and consisted of just the building that now houses the restaurant. Originally steam engines were used to pump the water into the three million gallon reservoir but these were eventually replaced using the water of the river itself for power. A 1204' dam was built across the river to direct the flow to three water wheels which ran the pumps. Along with this improvement further construction was needed which resulted in all the buildings we have today. The dam also opened up the river to recreation and industry - seems that we always must take the good with the bad.

Since the post-dam river was such a great source of power, transportation, and water for industry, several firms began operation not far upstream from the Water Works. The concomitant pollution was a source of worry and the city founded Fairmount Park to prevent the industry from operating in the area and thereby keep the river clean. So, because of Philadelphia's forward-thinking leaders of the early 1800s we now we have a lovely Greek Revival series of buildings on the river, a matching Greek Revival art museum that ranks with the best of the best, and the largest park in the world wholly contained within a city. Not only that, the Water Works has spawned many other developments such as jewelry and China-ware with reproductions of this wonderful sight. Back in the olden days, both the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers froze solid during the winter and with the ease of access and slower flowing water because of the dam across the Schuylkill the business of harvesting ice also became quite profitable. This, in turn, led to something that many Phillies and Eagles fans of today can relate to. Beer. Lager style brewing needs cool temperatures. With ice being easily available German immigrants began making lagers locally which led to the robust and diverse brewing industry we have in the area today. All this because of the need for a better water supply.

Reservoir on Reservoir Drive

William Penn planned to put his mansion on top of Faire Mount, where the Art Museum now stands. By 1880, long after Penn decided to build Pennsbury Mansion elsewhere, city growth outran the capacity of the new reservoir system which had then been placed on Fairmount. An additional set of storage reservoirs were placed on another hill across East River (Kelly) Drive, behind Robert Morris' showplace mansion now called Lemon Hill (Morris merely called it The Hill); the area was eventually named the East Park Reservoir. In time, trees grew up along the ridge and houses got built; the existence of these reservoirs right in the city was easily forgotten, even though the towers of center city are now plainly visible from them. These particular reservoirs were never used for water purification; that's done in four other locations around town, and the purified water is piped underground to Lemon Hill, for last-minute storage; gravity pushes it through the city pipes as needed.

Now, here's the first surprise. Water use in Philadelphia has markedly declined in the past century. That's because the major water use was by heavy industry, not individual residences, so one outward sign of the switch from a 19th Century industrial economy to a service economy is -- empty old reservoirs. Only one-quarter of the reservoir capacity is in active use, protected by a rubber covering and fed by underground pipes. The rest of the sections of the reservoir are filled by rain and snow, but gradually silting up from the bottom, marshy at the edges. Unplanted trees have grown up in a jungle of second-growth, attracting vast numbers of migratory birds traveling down the Atlantic flyway. Although there are only a hundred acres of water surface here, the dense vegetation closes in around the visitor, giving the impression of limitless wilderness, except for the center city towers peeping through gaps in the forest. It's fenced in and quiet except for the birds. For a few lucky visitors, it's easy to get a feeling for how it must have looked to William Penn, three hundred or more years ago, and Robert Morris, two hundred years ago. In another sense, it demarcates the peak of Philadelphia's industrial age, from 1880 to 1940, because that kind of industrialization uses a lot of water.

The place, in May, is alive with Baltimore Orioles. Or at least their songs fill the air and experienced bird watchers know they are there. Even a beginner can recognize the red-winged blackbirds, flickers, robins, and wrens (they like to nest in lamp posts). The hawks nesting on the windowsills of Logan Circle suddenly makes a lot more sense, because that isn't very far away. In January, flocks of ducks and geese swoop in on the water surface, which by spillways is kept eight feet deep for their favorite food. Just how the fish got there is unclear, perhaps birds of some sort carried them in. The neighborhoods nearby are teeming with little boys who would love to catch those fish, but it's fenced and guarded much more vigorously since 9-11. In fact, you have to sign a formal document in order to be admitted; it says "Witnesseth" in big letters. Lawyers are well known for being timid souls, imagining hobgoblins behind every tree. However, there are some little reminders that evil isn't too far away. Just about once a week, someone shoots a gun into the air in the nearby city. It goes up and then comes down at random, with approximately the same downward velocity when it lands as when it left the muzzle upward. That is, it puts a hole in the rubber canopy over the active reservoir, which then has to be repaired. No doubt, if it hit your head it would leave the same hole. So, sign the document, and bring an umbrella if the odds worry you.

A treasure like this just isn't going to remain as it is, where it is. It's hard to know whether to be most fearful of bootleggers, apartment builders or city councilmen, but somebody is going to do something destructive to our unique treasure, possibly discovering oil shale beneath it for example, unless imaginative civil society takes charge. At present, the great white hope rests with a consortium of Outward Bound and Audubon Pennsylvania, who have an ingenious plan to put up education and administrative center right at the fence, where the city meets the wilderness. That should restrict public entrance to the nature preserve, but allow full views of its interior. Who knows, perhaps urban migration will bring about a rehabilitation of what was once a very elegant residential neighborhood. And push away some of those reckless shooters who now delight in potting at the overhead birds.

This whole topic of waterworks and reservoirs brings up what seems like a Wall Street mystery. Few people seem to grasp the idea, but Philadelphia is the very center of a very large industry of waterworks companies. The tale is told that the yellow fever epidemics around 1800 were the instigation for the first and finest municipal waterworks in the world. There's a very fine exhibit of this remarkable history in the old waterworks beside the Art Museum. But that's a municipal water service; why do we have private equity firms, water conglomerates, hedge funds for water industries, and other concentrations of distinctly private enterprise in the water? One hypothesis offered by a private equity partner was that the success of the municipal water works of Philadelphia stimulated many surrounding suburbs to do the same thing; it was surely better than digging your own well. This concentration of small and fairly inefficient waterworks around the suburban ring of this city might well have created an opportunity for conglomerates to amalgamate them at lower consumer cost. Anyway, it seems to be true that if you want to visit the headquarters of the largest waterworks company in the world, you go about seven miles from city hall and look around a nearby shopping center. If you are looking for the world's acknowledged expert in rivers, you go to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia on Logan Square and look around for a lady who is 104 years old. And if you have a light you are trying to hide under a barrel, come to Philadelphia.

Laurel Hill

|

| Laurel Hill Cemeteries |

There are two Laurel Hill Cemeteries in Philadelphia, sort of. Although both are described as garden cemeteries, the older part in East Fairmount Park is more of a statuary cemetery or even a mausoleum cemetery. When its 74 acres filled up, the owners bought expansion land in Bala Cynwyd, which could come closer to present ideas of a memorial garden. Particularly so, when the older cemetery area started to fill in every available corner and patch and began to look overcrowded. The name was used by the Sims family for their estate on the original area. Since June-blooming mountain laurel is the Pennsylvania state flower and a vigorous grower, it seems likely the bluff overlooking the Schuylkill was once covered with it. Somehow the May-blooming azalea has become more popular throughout the region, particularly in the gardens at the foot of the Art Museum. If extended a little, merged with laurel on the bluff, and possibly with July-blooming wild rhododendron, there might someday arise quite a notable display of acid-loving flowering bushes from the Art Museum to the Wissahickon, continuously for two or three months each spring.

There are interesting transformations in the evolving history of cemeteries, best illustrated in our city by the traditions of the early Quakers when they dominated Philadelphia.

|

| Thomas Grey |

Objecting to the ornate monuments which Popes and Emperors erected for their military glory, and probably to the aristocratic custom of burying important people inside churches where they could be worshiped along with the stained-glass saints, early Quakers were reluctant to mark their own graves with headstones, or even to have their names engraved on such "markers". By contrast with the splendor accorded aristocrats, the common people in Europe were largely dumped and forgotten, providing an unfortunate contrast. During the early part of what we call the romantic period, Thomas Gray popularized these attitudes in Elegy in a Country Churchyard. To be fair about it, the early Christian Church had a strong tradition of collecting the dead of all classes into catacombs. The Romans were quite reasonably upset by the potential for spreading epidemics through people living within such arrangements, although feeding the Christians to the lions seems like an overreaction.

At any rate, and to whatever degree the French Revolution was what shattered previous traditions, the Victorian or romantic period produced a new vision: garden cemeteries in Paris.

|

| George Mead |

The concept soon spread to Laurel Hill, and thence to the rest of America. Acting with what probably had some commercial motivation, cemeteries then moved away from churches to suburban parks, promoted as places of great beauty in which to stroll and hold picnics, perhaps to meditate. The private expense was not spared in statues and mausoleums, which often became display competitions between dry goods merchants and locomotive builders. Revolutionary heroes were dug up from their original graves and transported here to be more properly honored, as were some private persons whose descendants wished for more suitable recognition than conservative church rectors had offered. The Civil War created the staggering number of 632,000 war dead; based on the proportion of the population, that would be equivalent to six million in today's terms. Since they were almost all male, there must have been at least a half-million surplus women as a consequence. The nation and this almost unbelievably large cohort of single women had an impact on society for thirty or forty years after The War. Eventually, this would lead to colleges for women, suffrage and other forms of feminism, but the initial manifestations of what we now call Victorianism took the form of formalized grief, particularly the 75 National Cemeteries of crosses row on row. But private initiatives also took a variety of forms, including Laurel Hill's statuary to honor the valor of the fallen, ranked by the number of generals buried there and visits by sitting Presidents of the United States. Laurel Hill, East, holds 42 Civil War Generals. It will be recalled that Lincoln's Gettysburg Address was delivered at a much larger final resting place for fallen soldiers, but Laurel Hill had the generals, including George Gordon Meade, himself. It is probably significant that Laurel Hill West, three times as large, was opened in 1867. At the headstone of each Civil War veteran is found a metal flag-holder, put there by the Grand Army of the Republic and marked with GAR surrounding the number 1. This is the home of Post Number One, the Meade Post, the original home of this organization responsible for many patriotic movements like the Pledge of Allegiance and commemorative reunion encampments and reenactments. The main purpose of the war was to preserve the unification of a continental nation, and the GAR sought to raise patriotic consciousness to a point where fragmentation would never again be conceivable.

|

| John Notman |

Two names stand out in the history of these cemeteries, Notman and Bringhurst. John Notman was one of the early architects who fashioned the look and feel of Philadelphia. His identifying feature is brownstone, as seen cladding the Athenaeum building on Washington Square, and St. Marks Episcopal Church at 15th and Locust. At Laurel Hill, the main entrance confronts a brownstone sculpture by Notman of "Old Melancholy", depicting a typical Victorian romantic vision; just about all other monuments in the cemetery are either of acid rain-eroded marble or indelible granite. Brownstone from Hummelstown PA provided the characteristic look of New York residential architecture during this era. Philadelphia brownstone probably came from the same place. The other name is Bringhurst, dating back to 17th Century Germantown, long associated with the underlying sanitary purposes of the cemetery. The family finally and gladly sold the undertaking business a few decades ago.

Somehow, the image of cemeteries has now transformed from public places of meditation and reverence to places that are "spooky". Their greatest surge of visitors, these days, occurs at Halloween.

East Falls

|

| Kelly drive |

The views along the charming, curving, leafy East River Drive from the Art Museum to the (former) Falls of the Schuylkill are dominated by rowing and the rowing clubs, so it isn't surprising that Philadelphia's most famous oarsman, John B. Kelly, used to live in East Falls, the residential area just at the end of the rowing area. I was once sent to see him by a mutual acquaintance when we were considering buying a house in his neighborhood. "East Falls," he said, will remain a nice place as long as I am alive but not longer than that." He might have added the names of Connie Mack(Cornelius McGillicuddy) the fifty-year owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics who lived on Schoolhouse Lane, and Harry Robinhold, who lived on Warden Drive and was the only real estate agent who ever seemed to have properties available in the area. But the friendly warning that Kelly was intoning seemed quite plausible, and we didn't buy the house.

|

| Roosevelt Blvd. |

There seems to be no question that Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner were married in Philadelphia in November 1951 and that Jimmy Duffy did the catering. It's only hearsay, strongly asserted, that the wedding took place in a big white house at the corner of School House Lane and Henry Avenue. That would, I believe, be the house where Connie Mack the baseball team owner and manager, lived. Just what connection these movie stars had with Connie, or with Grace Kelly who lived a block away, is undocumented but strongly suggested.

|

| Arlen Specter |

Decades later, however, East Falls continues to be a curious little cluster of three thousand houses, very close to the center of town but leafy and suburban, surrounded by other neighborhoods which underwent serious urban decay long ago. The Wissahickon Valley on one side,Roosevelt Expressway on a second, and the Schuylkill River on a third give it physical isolation, and the brow of the hill is held apart from West Germantown by a couple of large schools and college campuses. Even the strip of small commercial businesses along East River Drive serves to discourage random wanderers. But that's just as true further East along the comparable strip near the Delaware, where it doesn't have the same result.

More likely, the fact that so many judges and politicians live there (the list includes Mayor Governor Rendell and Senator Specter) guarantees police protection of a high order, and probably also makes inconvenient government construction, or regulation, highly unlikely. The local school is good, the local private schools are even better. If you are ever seeking to improve local residential amenities (and real estate values), you ought to study what it is that enhances East Falls, and quietly act on your discoveries.

Germantown Nurses the Yellow Fever, 1793

|

| Yellow Fever, Phila |

The French Revolution continued from 1789 to 1799 and created the opportunity for a second revolution in the New World which a second overstretched European country would lose. The slaves of Haiti just about exterminated the white settlers, except for the few who escaped, taking Yellow Fever and Dengue with them. Both diseases are mosquito-borne, so they flare up in the summer and die down in the winter, although the Philadelphians who welcomed the exiles didn't know that. Yellow Fever in Philadelphia was bad in 1793, came back annually for three more years, and flared up once again in 1798. It could be easily observed to be more frequent in the lowlands, absent in the hills. Seasonal, it reached a peak in October, disappeared after the first frost. In the early fall, people died a horrible yellow death, jaundiced and bilious.

|

| Dr. Rush |

The Yellow Fever epidemic had a profound effect on many things. It was one of the major reasons the nation's capital did not remain in Philadelphia. It made the reputation of Dr. Benjamin Rush who announced a highly unfortunate treatment -- bleeding the victims -- thus provoking numerous anti-scientific medical doctrines based on the relative superiority of doing nothing at all. In Latin, Galen had capsulized the doctrine of Hippocrates in the "Epidemics" as premium non-nocere ("At least do no harm.") It took a full century for American scientific medicine to recover from this blow to its reputation. Whatever criticism Rush may deserve for his Yellow Fever blunder, it definitely is not true that he was a scientific lemon. Medical students are regularly surprised to learn that he is the physician who first identified and described the tropical disease of Dengue, or "break-bone fever", which was a somewhat less noticed feature among the Haiti exiles in Philadelphia. In still other scientific circles, Benjamin Rush is often referred to as the "Father of American Psychiatry". He was one of the founders of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the oldest medical society in North America. Medical colleagues who today scoff at the yellow fever episode seem to forget that Rush stayed behind to tend the sick during a devastating epidemic, while many of his more cautious colleagues fled for their lives. An unhesitating signer of the Declaration of Independence, whatever Rush did, he did courageously. Non-academic physicians have sarcastically referred to this episode ever since, as proving that "some people" think it is "better to publish than to perish".

One very good non-medical thing the Yellow Fever epidemic accomplished was to put an abrupt end to the torch-light parades of window-breaking rioters agitating, with Jefferson's approval, for an American version of the guillotine and the terror. Federalists like John Adams and William Bingham never forgave Jefferson or his admirers for this, so the class warfare movement might likely have got much worse if everyone had not suddenly dropped tools, and headed for the hilly safety of Germantown.

The President of the new republic, George Washington, was in Mt. Vernon in the summer of 1793, wondering what to do about the Yellow Fever epidemic, and particularly uncertain what the Constitution empowered him to do. He finally decided to rent rooms in Germantown and called a cabinet meeting there. His first rooms were rented from Frederick Herman, a pastor of the Reformed Church and teacher at the Union School, although he later moved to 5442 Germantown Ave, the home of Col. Franks. Jefferson chose to room at the King of Prussia Tavern.

During this time, Germantown was the seat of the nation's government. As was fervently hoped for, the cases of yellow fever stopped appearing in late October, and eventually, it seemed safe to convene Congress in Philadelphia as originally scheduled, on December 2.

Although Germantown was badly shaken by the experience, it was a heady experience to be the nation's capital. Meanwhile, a great many rich, powerful and important people had come to see what a nice place it was. Germantown then entered the second period of growth and flourishing. Walking around Germantown today is like wandering through the ruins of the Roman forum, silently tolerant of visitors who would have never dared approach it in its heyday.

REFERENCES

| Benjamin Rush: A Discourse delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Thomas A. Horrocks ASIN: B0006FCBXS | Amazon |

| Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague Of Yellow Fever In Philadelphia In 1793: J.H. Powell ISBN-13: 978-1436715881 | Amazon |

| Germantown and the Germans: An Exhibition from the Collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia: Edwin, II Wolf ISBN-13: 978-0914076728 | Amazon |

The Wissahickon