4 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Colonial Times

More than half of American history took place before 1776, but after 1492. For Philadelphia, Colonial history lasted about a century.

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

To Germantown, a Short Appreciation

Seven miles from the heart of Philadelphia, Germantown was once a separate town, the cultural center of Germans in America. Revolutionary battles were fought here, it was briefly the capital of the United States, and it still has an outstanding collection of schools and colleges.

Germany Before Germantown

A breezy summary of European geopolitics, including many rough inaccuracies, will possibly irritate residents of that region who read it but may help Americans understand the history and composition of the Germantown area of Philadelphia.

The Western World was defined as a province of Rome, and all roads led there. A better unifying concept would be, the Alps are the center of Europe and all roads had to go around those mountains. At the northern end of the Italian boot are the Swiss Alps, forcing even Romans to go through what is now Provence in France to get around them. Rivers run off the tops of mountain ranges, of course, and then trickle away to some sea. An old jingle defines the river system of Switzerland as The Rhine, the Rhone, Danube and Po--arise in the Alps, and away they go!"

|

| Rhine River |

So northward-bound Romans, Julius Caesar and all, went West around the Alps up the valley of the south-flowing Rhone, eventually portaging over to the north-flowing Rhine River flowing to Rotterdam, which in turn is just across the English channel from mouth of the Thames leading to London, or Londinium as they called it. The crossover between the Rhone and the Rhine was at Strasbourg where the European Parliament now meets. For two thousand years, the main highway from Rome to London was via the Rhone-Rhine-Thames river complex.

Essentially, residents to the West of the Rhone-Rhine were Roman Catholic, and residents to the East were Protestant. At least, that was as true in the Sixteenth Century as reciprocal genocide might accomplish. The head of the Rhine River in Switzerland was Calvinist Protestant, and the mouth of the river in Holland was Reform Protestant. Along the main part of the river, Alsace, Lorraine, Palatine, Luxembourg,divided East and West but for centuries pieces of land shifted control back and forth. The reformation movement started by Martin Luther ended up as the Thirty Years War, from which the region took another hundred years to recover, and more hundreds of years to forget and forgive. You might call it a religious Mason-Dixon line, remembering of course that the American Civil War was mostly fought on the Potomac, not the Mason Dixon.

|

| George Fox |

Professional soldiers teach military students that there is no war more remorseless than a religious war. Lots of people, probably thousands, were burned at the stake during the religious wars along the Rhineland. Rape and pillage were common practice. And so, if you lived in a little farming village in this region, and some Englishman named William Penn came around with an offer to emigrate to his peaceful kingdom in America, it sounded wonderful. Religious toleration was an important part of the attractiveness, and nowhere to be found in Europe.

William Penn's mother was Dutch. It is likely he spoke the local languages. For a number of years in his youth he had traveled in the Low Countries and the Rhineland, preaching the ideas of George Fox The Quaker. And then, one day he arrived with a brand new idea. The King of England had given him a huge stretch of uninhabited land in the New World, no doubt influenced by the idea that Quakers were a nuisance and this was a good way to get rid of them. Whatever. Penn was selling land grants, and he could be trusted. Why not give it a try?

Wizards of the Wissahickon

|

| Peace Treaty of Westphalia |

The Holy Roman Empire comprised about 120 little kingdoms along the Rhine River, mostly Germanic, stretching from Amsterdam to Switzerland, and loosely associated with the Papal States extending onward to Sicily. Napoleon and Bismark unified much of this territory into what we might now recognize as a map of Western Europe. Before that, it had been roughly the battleline between Catholic and Protestant populations, provoked by the influence of Martin Luther spreading through what had for centuries been an entirely Catholic region. After the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, it became a rule of the Holy Roman Empire that the state religion of a country was whatever the local king said it was.

With this history and more, it is unsurprising that the region was filled with small stranded religious sects who were out of local secular favor. William Penn's mother was Dutch, so he could speak the local language and had lived in the region. When this immensely rich Englishman acquired the colony of Pennsylvania, it was natural for him to offer religious sanctuary to Germanic sects as well as to the dissident Quakers of England, in that free-religion colony he planned for his wilderness region, larger than the whole of England.

|

| Johannus Kelpius |

From this history it emerges that "Dominie Johann Jacob Zimmerman, a noted German mathematician, astronomer, and defrocked Lutheran minister", led a remarkably well-educated group of "Pietists, millennialists, Rosicrucians, and Separatists" to London and then to Rotterdam, picking up some Swiss, Transylvanians, Swedes and Finns. Among them was a young Transylvanian scholar originally named Kelp, which in scholarly tradition had changed to Johannus Kelpius. Responding to the astronomical calculations of Zimmerman, it was believed the millennium of peace and tranquility predicted by the Book of Revelations would begin more or less immediately. The group resolved to accept the offer of William Penn and go to Pennsylvania to enjoy that millennium. Unfortunately, Zimmerman died as the ship was departing and young Kelpius, who himself was later to die of tuberculosis at the age of 34, was appointed the new leader.

|

| Kelpius Cave |

Evidently, on arrival in Philadelphia in 1694, they encountered earlier inhabitants who had a tradition of a bonfire midway between the solstice and the equinox. Their fire was on top of "Fire Mount", and was taken as a sign that the millennium was now beginning. The group moved up to the top of the Wissahickon, next to where Rittenhousetown is now to be found, and just beyond it in Roxborough was a hollowed out formation resembling an amphitheater. It is now believed an astronomical observatory was created on the projecting rock next to the present foot of the Henry Avenue bridge; it was at that place that two celibate monasteries (for men and for women) lived together, slowly dying out as celibate communities necessarily do. Eventually, the death of Kelpius caused the final break-up of the little colony, but not before it had established itself as a center of music, poetry, and literature for the growing Germanic settlers of the surrounding states. One group of them went further west to the Cloister at Ephrata, and others scattered in different directions. It is notable that a great many names of settlers in the Kelpius colony are still to be found in Germantown, Philadelphia, and Harrisburg, although tracing the genealogy has been difficult. Some of the music has been found in scraps and reconstructed, and discovered to be quite sophisticated and beautiful, although precise authorship remains uncertain.

REFERENCES

| An Introduction to the Music of the Wissahickon Glen: Lucy E. Carroll, DMA, | Kelpius Society |

| The Hymn Writers of Early Pennsylvania: Lucy E. Carroll, ISBN: 978-1606475201 | Amazon |

The Wissahickon

Recently, Sarah West came to the Right Angle Club and told us about the history of the Wissahickon Creek. Sarah taught at Germantown Friends School for twenty-five years, and in the course of it became the acknowledged expert on the Wissahickon. The mouth of the creek empties into the Schuylkill in Fairmount Park, but the mouth of it is so covered over with a tangle of clover-leaf overpasses, most people zip past without noticing. After that, the drivers of cars up to Chestnut Hill are so busy negotiating the sharp curves, they don't see much of the rest of the creek, either. There's a stop light opposite Rittenhousetown, so perhaps the little village is noticed on the other side of the rivulet, but the entrance is off to the left on Wissahickon Avenue, approachable only from the other direction, so even this cute little village is seldom visited. Pity.

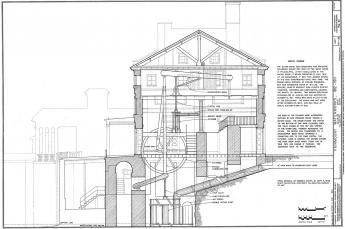

First, notice that the mouth of the creek is just opposite City Line Avenue, so it is an important geographical landmark. The creek is 23 miles long, going right past Roxborough and ending up well beyond Philadelphia's city limits. To a passing motorist, the creek seems to disappear at Rittenhousetown, and the commuter goes on his way through miles of the city before reaching Chestnut Hill. In fact, the creek curves abruptly north at Rittenhousetown and travel twenty miles through woods and wilderness, accompanied by fifty miles of hiking trails. This Wissahickon Park contains about 1200 acres of the 9600-acre Fairmount Park; at one time it was lined with mills seeking water power for one industrial activity or another. From Rittenhousetown to Chestnut Hill College the creek is accompanied by Forbidden Drive, forbidden (in 1922) to automobiles, that is. It crosses Germantown Avenue at that point and circles around Chestnut Hill College, only a branch disappears back into the woods surrounding the edges of the College and Morris Arboretum. On its right that branch of it, starting at Chestnut Hill College, passes (and supplied water for) Washington's encampment at Fort Washington. As a sidelight, Forbidden Drive parts company with the creek at Chestnut Hill College and the main branch of the creek goes on for miles past the Whitemarsh Country Club, then the Germantown Cricket Club, and the Wissahickon Valley Park, eventually reaching its origin in the water runoff from a parking lot off in the country near Ambler, well past Fort Washington, out in Montgomery County.

Only a short part of the Wissahickon is visible from the paved road, which veers to its right near the top of the steepest dropdown of the cliff on the west side of Germantown. That's one of two ridges. Roxborough is on one side of the valley, Germantown and Chestnut Hill on the east. The longest part of the creek veers to the left up to the wooded valley, along miles of Forbidden Drive before it re-emerges to the sight of motorists as it crosses Bethlehem Pike. This was one of several routes followed by sections of Washington's army in their attack on the Chew Mansion in the Revolutionary War. Washington lost, partly because of the stout stone walls of the Chew House, and partly because two sections of his troops got lost in the fog along the creek and started shooting at each other. Even today, the geography around here is so confusing it is really pretty hard to criticize Washington for getting mixed up.

The edge of the Wissahickon Creek was first settled by an early group of Germans led by Johannus Kelpius in the Seventeenth Century; the Kelpius Society feels that colony was located around the Henry Avenue Bridge footings standing athwart the gorge, comparatively near the mouth of the creek into the Schuylkill. Swift waters running downward provided water power for mills, originally paper mills. Paper plus education leads to printing, and at this point was located the heart of German culture, running north and south through all the thirteen colonies; eventually, this settlement of Baptists, Dunkards, and Church of the Brethren moved westward toward Ephrata and other more scattered locations. Sarah tells us that a good workman could produce about three hundred sheets of paper in a day, so it had to be of good quality. Many of the historical documents of the Revolutionary period were written or printed on this paper. Bear in mind, however, that nothing smells so bad as a paper mill.

It takes wood to make paper, so paper mills tend to denude the surrounding hills and start a process of washing away the topsoil. The creeks started to flood in the spring, and dry up in the summer. The final blow of this type was caused by Hurricane Floyd in 1985, which washed away many of the landmark buildings, leaving miles of the woods to the pleasure of hikers and joggers and environmentalists. Sarah West reports that you don't have to walk very far into the woods to find the remnants of mills and mansions, many of which had fruit cellars dug into the side of the basements. Some of these fruit cellars were then extended into tunnels, allowing the Underground Railroad to flourish here before the Civil War. And possibly earlier than that, because this area close to Philadelphia was a favorite place for spies to hide, attracting British raiding parties during the Revolution.

|

| Wissahickon Valley |

But water power was water power in Colonial days, and mills of all kinds flourished up and down the length of the creek until steam power ultimately posed too much competition. For a while, the dwindling water-powered mills supplemented their power with the steam generation, and tall smokestacks, but eventually, water power was driven away by steam power. Whether it was a flour mill or a nuts and bolts factory, grist mills or blanket factories, the product was usually shipped in white oak barrels, which hastened the destruction of the woods and made the flooding worse. Around each mill was usually found a cluster of houses for the workers, so the whole Wissahickon Valley eventually filled with settlements, usually with the owner's mansion dominating the scene, surrounded by little workers' houses. Eventually, the stream became polluted, and the pollution was unfairly blamed for Yellow Fever epidemics. The Schuylkill Water Works and the migration of the factories elsewhere did a whole lot of good for typhoid fever, which definitely is caused by water pollution. So pollution control is sometimes useful even if there is no pollution of the kind you had in mind. The area became Fairmount park, dotted with mansions which used to belong to rich Quaker families with names like Evans and Livezy. There were once five covered bridges scattered along the creek, but mostly they were replaced by bridges, or just got washed away.

So, over the course of two centuries, the pioneers settled the woods, the civilization created a factory town in the middle of a peaceful city, and then the environment took it all back. Now we have a forest in the middle of a city, and rather more unemployment than we want. It isn't fair to say the environmentalists won, it just seems to be cyclic. So enjoy it while you can.

Taming the Creeks of Olde Philadelphia

For the past ten years, the Morris Arboretum has sponsored a mini-bus tour of the sewers of Philadelphia conducted by Adam Levine. In spite of its name, it attracts a pretty high-brow audience, who have a perfectly wonderful experience. Adam has been a consultant to the Water Department for decades, and he gives a pretty polished tour, which anyone interested in the City really ought to join some year. He's planning to write a book about it, someday, and instead of giving away all the best stories, I bet it will swell attendance at the tours considerably. Some of us know that writing books can be pretty hard work, however, while giving tours seems like a lot of fun.

When William Penn picked out this area for his new city, there were herds of swans swimming in the Delaware River around the mouth of the Schuylkill, and there were wide mud flats thrown up around what we call the airport, by the slowed waters making a big turn there. Although Mr. Penn originally planned to settle at what we now call Chester, apparently he thought the protected river above the mud flats would be a safer harbor. In the area of Philadelphia County in Penn's time, there were about three hundred miles of creeks, now reduced to about one hundred by the Water Department and the Department of Streets. Dock Creek was the main seaport at first, and it eventually became Dock Street by putting the creek into a culvert. In a sense, that is what has been happening for three hundred years, all over town. At first, the creeks supplied drinking water, and then they became sewers, and then they became streets on top of sewers.

As a matter of fact, there were further steps in the process. The railroads were laid on the banks of creeks, to reduce the amount of excavation and fill-in required. And as factories were built along the creeks to take advantage of the transportation and water power, the run-off of sewage was mixed with ground-water runoff, in what is delicately spoken of as a "combined sewer". The water department spends most of its time and money nowadays, separating rainwater sewage from the real thing, and diverting the rainwater into ponds and other catchment hollows, where the relatively clean water percolates through the soil and cleans itself up. The real sewage is diverted into massive pipe systems leading to the sewage disposal plants. Where, would you believe it, it gets cleaned and chlorinated and returns as drinking water -- purer than the river water that flows past, by a good bit.

But that gets ahead of the story somewhat. As the factory areas become liveable, the sewers encased in the pipe are at the bottom, the rail lines are somewhat higher. Where there were no railways, the electrical and water pipes are high above it all and often get encased in concrete. However, we can expect combined sewers to last a long time, since it is estimated that the project of uncombining two-thirds of the sewer system will cost several billion dollars, and require twenty-five years to complete. The infrastructure money from the "Stimulus package" will be a forgotten episode of the past when this project is finished. Philadelphia likes straight streets aligned in grids, so you can almost be certain you are over a creek bed when the road gets crooked in Philadelphia.

Now, look at the grid of streets from the point of view of a Water Department engineer. Somebody gave the process the name of a waffle, and it is very apt. As the straight streets go as straight as they can, they cut through hills and fill up the gullies. The fill from the hills is used for the valleys, so the straight grid streets are generally somewhat higher than the residential areas, giving the waffle effect, but leaving half of the houses with a sharp embankment in their lawns going down to street level, and the other half of the houses with water in their basements. It's up to the house builder to fill up the depression between the streets, with the streets nevertheless somewhat higher than the depressions. Sometimes the streams cut through, and are encased in pipes as they go under the streets. Sometimes it's just too much to handle, and we get green parks scattered around the city, breaking up the monotony of row houses, for a generally pleasing effect not seen in flat areas, like New Jersey.

The city has two watersheds, one draining into the Delaware River, and the other draining into the Schuylkill. And the trail between the two watersheds, the continental divide if you please, is Germantown Avenue.

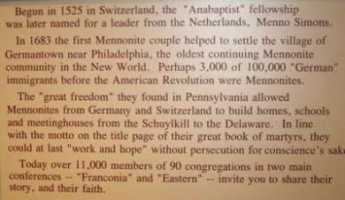

History of the Mennonites

Mennonites: The Pennsylvania Swiss

|

| On the Wall of the Mennonite Heritage Center |

Anabaptism, originally attributed to Ulrich Zwingli around 1525, centers around believing a baby is too young to understand baptism, so adults need to be re-baptized. The idea arose independently in Switzerland and Holland, and probably thousands of believers were unmercifully martyred for holding the belief. Because the worst persecutions took place during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-50), they are often attributed to the Roman Catholic Inquisition, but Magisterial Protestants, believing in the separation of church and state, were often also responsible. Many seemingly unrelated issues were introduced locally, and this period of unrest is known as the French and Indian War in America; its major battle took place in Louisburg, Nova Scotia, although George Washington's skirmish around Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) has acquired local fame as a major American manifestation.

The Swiss adherents moved to the Rhineland Palatinate, and from there were among the first to accept William Penn's offer of religious freedom. They were the settlers of Germantown, but have mainly moved a few miles west to southern Montgomery County, where the confusion about Pennsylvania Dutchmen is further confounded by the fact that they were Swiss. Menno the Dutchman gave his name to the order, but they themselves regard their true ethnic background as Swiss from the Zurich region. That, by the way, is not to be confused with Calvinism, which also comes from Switzerland, but by way of Geneva, not Zurich. The pacifism of the Mennonites made them mutually attractive with the English Quakers, who had made an appearance fifty or so years later in the region around Manchester, England; each group seems to have adopted some of the features of the other.

|

| Franconia Mennonite Meetinghouse |

Determined use of the German language has always held the Mennonites apart, however. From the start, it was really necessary to be somewhat bilingual in Montgomery County, using English for business conversation, and German at home and in the church. The idea of using a foreign language is based on the hope it would thus maintain a sense of distinctiveness or even remoteness from non-believers, without adopting the least hostility to them. It almost inevitably follows that the group has used its own schools, attached to their meeting houses. This sense of remoteness has persisted for almost four hundred years, surrounded by entirely different cultures. Starting only around 1960, this attitude has gradually softened, however, and it is widely assumed that in another few decades Mennonites will come to resemble the people in their environment a great deal more than they do at present. If you want to know where to find them, Harleysville is a good place to start. As the tinge of Pennsylvania Dutch accent gradually fades, and fewer of them wear the old costumes, a curious remaining hallmark of their presence can be noticed: an avoidance of foundation planting around their houses. The Mennonites themselves seem to be entirely oblivious to this unintended distinctiveness, which is however quite striking to non-Mennonite passers-by. Those who work in the fields all day have little interest in digging around their houses for decoration; those who have moved away from farming have seemingly adopted the bush-less style as a natural way of arranging things. There's no particular reason to change it, and so, there's no particular reason to notice it.

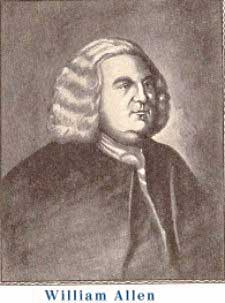

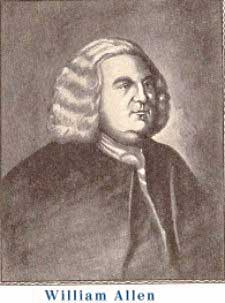

William Allen, Tory

|

| William Allen |

William Allen was once famous for his expensive carriage and a team of horses, at a time when there were only eighty carriages in the colony. He was born wealthy but personally made considerable sums in maritime trade, which in those days included a mild form of piracy called privateering. Taking his accumulated wealth, he invested heavily in colonial real estate. His urban ventures included the land under Independence Hall, and his lands in the hinterland included the present town of Easton. He was a tough businessman, providing "muscle" where needed in a colony dominated by pacifist Quakers. At one point, he imported a thousand muskets and ammunition for the use of settlers in the Lehigh Valley who had difficulties with the Indians and Connecticut invaders. Allentown is named after him.

|

| Philadelphia Lawyer |

It is difficult to apply present standards of judgment to Allen. William Penn had been given the colony on condition that he protect and maintain it. That was clearly a difficult challenge for a Quaker colony in the wilderness, surrounded by Indians, French and Spanish buccaneers, and neighboring colonies who were far from pacifist themselves. The system often amounted to giving land to subcontractors like Allen, on condition that they maintain law and order. Furthermore, Allen was quite obviously a person of parts. His credentials as Chief Justice were based on his attendance at the Inns of Court when almost all other lawyers were trained by local apprenticeships. His father in law was Andrew Hamilton, the famous "Philadelphia lawyer" who won the landmark case for Peter Zenger and later became the leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly and mentor to young Benjamin Franklin. His land-dispute services in the negotiations with Lord Baltimore were notable. In general, he was a continuing force for peace and stability, and no one held it against him that peace and stability suited his needs as a landlord and merchant. To him, the battle for independence was just another unsettling disturbance which prevented the colony from achieving its potential.

His daughter married John Penn, the grandson of William Penn, who was the local representative of the Proprietors and later the Governor. All in all, it is not surprising that he retreated to his home on Germantown Avenue, called Mt. Airy, when the revolution broke out. Unlike many other Tories who fled to Canada, he felt his past services would protect him if he remained quiet and secluded until the war was over. He didn't quite make it, dying in his mansion, in 1780.

Germantown Before 1730

|

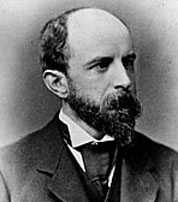

| Rev. Wilhelm Rittenhausen |

The flood of German immigrants into Philadelphia after 1730 soon made Germantown, into a German town, indeed. From 1683 to 1730, however, Germantown had been settled by Dutch and Swiss Mennonites, attracted by the many similarities between themselves and the Quakers of England. They spoke German dialects to preserve their separateness from the English-speaking majority but belonged to distinctive cultures which were in fact more than a little anti-German. This curiosity becomes easier to understand in the context of the mountainous Swiss burned at the stake by their Bavarian neighbors, Rhinelanders who sheltered them from various warring neighbors, and Dutchmen at the mouth of the Rhine, all adherents of Menno Simon the Dutch Anabaptist, but harboring many differences of viewpoint about the tribes which surrounded them.

Anabaptism is the doctrine that a child is too young to understand religion, and must be re-baptized later when his testimony will be more binding. In retrospect, it seems strange that such a view could provoke such antagonism. These earlier refugees were often townspeople of the artisan and business class, rapidly establishing Germantown as the intellectual capital of Germans throughout America. This eminence was promoted further through the establishment by the Rittenhouse family (Rittinghuysen, Rittenhausen) of the first paper mill in America. Rittenhousetown is a little collection of houses still readily seen on the north side of the Wissahickon Creek, with Wissahickon Avenue nestled behind it. The road which now runs along the Wissahickon is so narrow and windy, and the traffic goes at such dangerous pace, that many people who travel it daily have never paid adequate attention to the Rittenhousetown museum area. It's well worth a visit, although the entrance is hard to find (try going west on Wissahickon Avenue then turning around, a little beyond the entrance).

Even today, printing businesses usually locate near their source of paper to reduce transportation costs. North Carolina is the present pulp paper source, several decades ago it was Michigan. In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, paper came from Germantown, so the printing and publishing industry centered here, too. When Pastorius was describing the new German settlement to prospective immigrants, he said, "Es ist nur Wald" -- it's just a forest. A forest near a source of abundant water. Some of the surly remarks of Benjamin Franklin about German immigrants may have grown out of his competition with Christoper Sower (Saur), the largest printer in America, and located of course in Germantown.

Francis Daniel Pastorius was sort of a local European flack for William Penn. He assembled in the Rhineland town of Krefeld a group of Dutch Quaker investors called the Frankford Company. When the time came for the group to emigrate, however, Pastorius alone actually crossed the ocean; so he was obliged to return the 16,000 acres of Germantown, Roxborough and Chestnut Hill he had been ceded. Another group, half Dutch and half Swiss, came from Krisheim (Cresheim) to a 6000-acre land grant in the high ground between the Schuylkill and the Delaware. The time was 1683. The heavily Swiss origins of these original settlers give an additional flavor to the term "Pennsylvania Dutch".

Where the Wissahickon crosses Germantown Avenue, a group of Rosicrucian hermits created a settlement, one of considerable musical and literary attainment. The leader was John Kelpius, and upon his death the group broke up, many going further west to the cloister at Ephrata. From 1683 to 1730 Germantown was small wooden houses and muddy roads, but there was nevertheless to be found the center of Germanic intellectual and religious ferment. Several protestant denominations have their founding mother church on Germantown Avenue, Sower spread bibles and prayer books up and down the Appalachians, and even the hermits put a defining Germantown stamp on the sects which were to arrive after 1730. The hermits apparently invented the hex signs, which were carried westward by a later, more agrarian, German peasant immigration, passing through on the way to the deep topsoil of Lancaster County.

The Schools of School House Lane

|

| Union School founded in 1759 |

The region of Philadelphia defined as Germantown is recorded by the last census as having about 50,000 inhabitants today, 40,000 of whom are of the black race. Germantown has always had an unusual concentration of schools of the highest quality, and here on one street alone there are four. School House Lane runs off to the West of Germantown Avenue, and was originally right at the center of town, the center of the action during the Revolutionary War. The most historic of the schools, the Union School founded in 1759, changed its name to Germantown Academy, and more recently picked up and moved to new quarters in Fort Washington. George Washington sent his nephew there, and its building served as a hospital for the wounded in the Battle of Germantown. When Germantown Academy moved out of Germantown, the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf moved into the vacated quarters. This school had been originally founded in 1820, and is one of nearly a hundred special schools for the deaf in the United States, operating as a quasi-public institution for about 170 students. A remarkable thing about all schools for the deaf is the high IQ of their students. Perhaps deaf underachievers are somehow filtered out by the struggle to adapt before they apply for admission, or perhaps there is something about being deaf that makes you smart. In any event, the average SAT scores of students from PSD, like all schools for the deaf, are always in the very highest ranks among secondary schools.

|

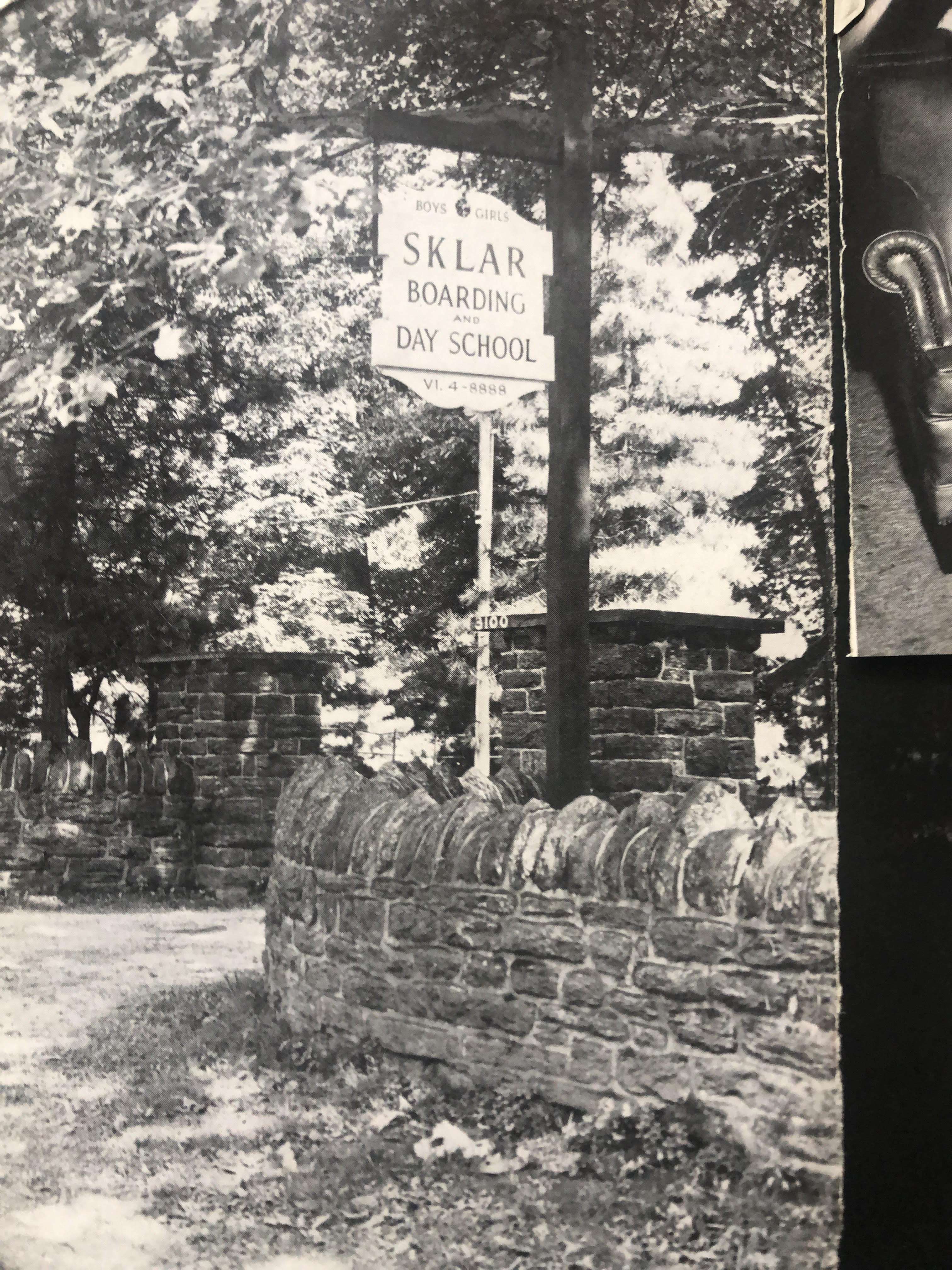

| Sklar School Entrance |

More or less next door to it, fronting on Coulter Street, is the Germantown Friends School(GFS), which enjoys and deserves the reputation of the most intellectually rigorous school in the Philadelphia region. There is little question about the Quakers of this school, founded in 1845, but relatively few of the students are now Quaker children. It's pretty expensive and quite uncompromising about its academic standards, but if you want to be accepted by a famous University, this is the place that can boast the most achievement of that variety. By no means all of its graduates become teachers, but alumni of this school do tend to gravitate to the top of academia. That could eventually put them on college admission committees, of course, and perhaps the admission process promotes itself. There can be little doubt that if most of a given college's admission committee happened to play the tuba, that university would soon fill up with tuba players.

|

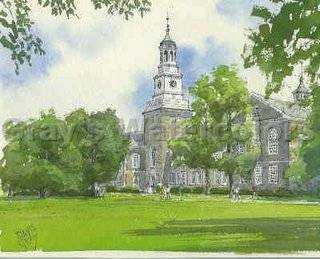

| William Penn Charter School |

Further West on School House Lane, is the William Penn Charter School. It's also Quaker, and while it doesn't work quite so hard at it as GFS does, it has plenty of social mission, a great deal more discipline, and plenty of competitive athletics. A minority of its students, also, are Quakers; but as a guess, most of its graduates are headed for disproportionate affluence anyway. The middle school is named for, and was donated by, the former chairman of Morgan Stanley back before Morgan Stanley sold itself to Dean Witter. This school was founded in 1689, and for a long time was located at 12th and Market Streets in Philadelphia, right where the famous PSFS building was built, the one that later converted to Lowe's Hotel .

Finally, near the crossing of Henry Avenue with Schoolhouse Lane, is the Philadelphia University. Since it was founded in 1999 it is the youngest of the schools on School House Lane, specializing in architecture and design, and seems headed for even broader curriculum. The University was formed by the merger of Ravenhill Academy for Girls, and the Philadelphia Textile School. The Textile School was itself formed during the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, when local industrialists became concerned with how backward America seemed in its quality and design of textiles, compared with other nations which exhibited at that World's Fair. Next door, was once the home of William Weightman, a chemical manufacturer who was reputed to be the richest man in Pennsylvania. After his death, the rather grand estate became the site of the Ravenhill School for Girls, which was the school which could boast Grace Kelly for an alumna. That was natural enough since she lived just around the corner on Henry Avenue and could walk to school. The contrast between the two ends of School House Lane, Henry Avenue on one end, and Germantown Avenue on the other, is just astounding.

So there you have School House Lane. A few short blocks with three distinguished preparatory schools and a university. Plus, the site of three other famous schools which have either moved or merged. You might think Germantown was the home of myriads of school teachers, but that isn't exactly so. It's hard to say just what this complex anomalous situation proves, except to voice the opinion that it is somehow at the heart of what Philadelphia really is.

Note, kind readers have also sent me the names of six more schools on Schoolhouse Lane. Some of them may only be name changes, but the list includes Parkway Day School, Sklar School, Philadelphia Textile and Science, Germantown Stevens Academy, Germantown Lutheran Academy, Greene Street Friends School. (See Comments.)

Slavery: If This be done well, What is done evil?

|

| Francis Daniel Pastorius |

The Declaration of the German Friends of Germantown, Against Slavery, in 1688.

These are the reasons why we are against the traffic of men's body, as followeth:

Is there any that would be done or handled in this manner? viz.: to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? How fearful and faint-hearted are many at sea, when they see a stranger vessel, being afraid it should be a Turk, and they should be taken, and sold for slaves in Turkey. Now, what is this better done, than Turks do? Yea, rather it is worse for them, which say they are Christians; for we hear that the most part of such negers is brought hither against their will and consent and that many of them are stolen. Now though they are black, we cannot conceive there is more liberty to have them, slaves, as [than] it is to have other white ones. There is a saying , that we shall do to all men like as we will be done [to] ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent, or color they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, which is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of the body, except evil-doers, which is another case. But to bring men hither, or to rob, [steal] and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe, there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed which are of black color. And we who know others, separating wives from their husbands, and giving them to others: and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! do consider well this thing, you who do it, if you would be done in this manner--and if it is done according to Christianity! You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe when they hear of [it,] that the Quakers do here handler men as they handle there the cattle. And for that reason, some have no mind or inclination to come hither. And who shall maintain this your cause, or plead for it? Truly, we cannot do so, except you shall inform us better hereof, viz,: That Christians have liberty to practice these things, Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse, towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating husbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at, [by]; therefore, we contradict [oppose], and are against this traffic of men's body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid purchasing such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing, if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of the hands of the robbers, and set free as in Europe. Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead, it hath now a bad one, for this sake, in other countries. Especially whereas the Europeans are desirous to know in what manner the Quakers do rule in their province; and most of them do look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil?

If once these slaves ( which they say are so wicked and stubborn men,) should join themselves--fight for their freedom, and handle their masters and mistresses, as they did handle them before; will these masters and mistresses take the sword at hand and war against these poor slaves, like, as we are able to believe, some will not refuse to do? Or, have these poor negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?

Now consider well this thing, if it is good or bad. And in case you find it to be good to handle these blacks in that manner, we desire and require you hereby lovingly, that may inform us herein, which at this time never was done, viz., that Christians have such a liberty to do so. To this end, we shall be satisfied on this point, and satisfy likewise our good friends and acquaintances in our native country, to whom it is a terror, or fearful thing, that men should be handled so in Pennsylvania.

This is from our meeting at Germantown, held ye 18th of the 2nd month, 1668, to be delivered to the monthly meeting at Richard Worrell's.

Garret Henderich

Derick op de Graeff

Francis Daniel Pastorius

Abram op de Graeff.***

At our Monthly meeting, at Dublin, ye 30th 2d mo., 1688, we have inspected ye matter, above mentioned, and considered of it, we find it so weighty that we think it not expedient for us to meddle with it here, but do rather commit it to ye consideration of ye quarterly meeting; ye tenor of it is related to ye truth.On behalf of ye monthly meeting,

Jo. Hart.

***

This above mentioned was read in our quarterly meeting, at Philadelphia, the 4th of ye 4th mo., '88, and was from thence recommended to the yearly meeting, and the above said Derick, and the other two mentioned therein, to present the same to ye above said meetings, it is a thing of too great a weight for this meeting to determine.Signed by order of ye meeting.

Anthony Morris

Germantown After 1730

|

| German Quaker Home |

The early settlers of Germantown were Dutch or German-speaking Quakers. They were proud of the craftsman class but, unfortunately, that made them rather poor subsistence farmers. With a whole continent stretching beyond them, professional farmers would not likely choose to settle on a stony hilltop, two hours away from Philadelphia. Germantown's future lay in religious congregation, in papermaking, textile manufacture, publishing, printing and newspapers. Plenty of stones were lying around, so stone houses soon replaced the early wooden ones. Since Philadelphia in 1776 had only twenty or so thousand inhabitants, and only thirty wheeled vehicles other than wagons, it was not too difficult for Germantown to imagine it might eventually eclipse that nearby seaport full of Englishmen. Two wars and two epidemics brought those Germantown dreams to an end, but in a sense, those calamities were stimulants to the town, as well.

In 1730 real German peasants began to arrive in large numbers from the Palatinate section of the Rhine Valley. They arrived as survivors of a horrendous ocean sailing experience, packed in such density that it was not unusual to find dead bodies in the hold, of passengers that had only been supposed to have wandered into a different part of the ship. Quite often, they paid for their passage by selling themselves into what amounted to limited-time slavery, and a customary pattern was for parents to sell an adolescent child into slavery for eight or ten years in order to pay for the voyage of the family. They were uneducated, even ignorant, and often were proponents of small new religious sects. All of that made them seem to be a primitive tribe in the eyes of the earlier settlers. But they were professional farmers, and good at it. They knew, and a quick tour of Lancaster County today confirms their belief, that if you had a reasonable amount of very good land, you could live a life that approached that of the craftsmen in comfort, and usually far exceeded them in personal assets. They have therefore taken a long time to rise from farm to sophistication, while the already sophisticated craftsmen in Germantown wasted no time in abandoning farming. The peasant newcomers arrived in Philadelphia, made their way to nearby Germantown, learned a little about the new country and the refinements of their Protestant culture -- and then pressed on to the great fertile valley to the West, where the way had been paved by those twenty-five German families who had landed on the Hudson River several decades earlier and come down the Susquehanna via Cooperstown. Only a minority of the after-1730 Germans stayed on permanently in that steadily growing little German metropolis on a hill, and none of the very earliest German pioneers further west had even landed in Philadelphia.

During this period, this Athens of German America also invented the Suburb. The pioneer of this concept was Benjamin Chew, the Chief Justice, who built a magnificent stone mansion on Germantown Avenue, which was to become the main fortress of the Battle of Germantown in the Revolutionary War. Present-day visitors are still impressed with the immensity and sturdy mass of this home. Grumblethorpe, Stenton and a score of other country homes were placed there. Germantown in 1750 still wasn't a very big town, but it was plenty comfortable, quiet, safe, intellectual and affluent. Its first disruption came from the French and Indian War.

Germantown and the French and Indian War

|

| The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army |

Allegheny Mountains from which to trade with, and possibly convert the Indians, the French had a rather elegant strategy for controlling the center of the continent. It involved urging their Indian allies to attack and harass the English-speaking settlements along the frontier, admittedly a nasty business. The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army at what is now Pittsburgh reported hearing screams for several days as the prisoners were burned at the stake. Rape, scalping and kidnapping children were standard practice, intended to intimidate the enemy. The combative Scotch-Irish settlers beyond the Susquehanna, which was then the frontier, were never terribly congenial with the pacifism of the Eastern Quaker-dominated legislature. The plain fact is, they rather liked to fight dirty, and gouging of eyes was almost their ultimate goal in any mortal dispute. They had an unattractive habit of inflicting what they called the "fishhook", involving thrusting fingers down an enemy's throat and tearing out his tonsils. As might be imagined, the English Quakers in Philadelphia and the German Quakers in Germantown were instinctively hesitant to take the side of every such white man in every dispute with any redone. For their part, the Scotch-Irish frontiersmen were infuriated at what they believed was an unwillingness of the sappy English Quaker-dominated legislature to come to their defense. Meanwhile, the French pushed Eastward across Pennsylvania, almost coming to the edge of Lancaster County before being repulsed and ultimately defeated by the British.

In December 1763, once the French and Iroquois were safely out of range, a group of settlers from Paxtang Township in Dauphin County attacked the peaceable local Conestoga Indian tribe and totally exterminated them. Fourteen Indian survivors took refuge in the Lancaster jail, but the Paxtang Boys searched them out and killed them, too. Then, they marched to Philadelphia to demand greater protection -- for the settlers. Benjamin Franklin was one of the leaders who came to meet them and promised that he would persuade the legislature to give frontiersmen greater representation, and would pay a bounty on Indian scalps.

Very little is usually mentioned about Franklin's personal role in provoking some of this warfare, especially the massacre of Braddock's troops. The Rosenbach Museum today contains an interesting record of his activities at the Conference of Albany. Isaac Norris wrote a daily diary on the unprinted side of his copy of Poor Richard's Almanac while accompanying Franklin and John Penn to the Albany meeting. He records that Franklin persuaded the Iroquois to sell all of western Pennsylvania to the Penn proprietors for a pittance. The Delaware tribe, who really owned the land, were infuriated and went on the warpath on the side of the French at Fort Duquesne. There may thus have been some justice in 1789 when the Penns were obliged to sell 21 million acres to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for a penny an acre.

Subsequently, Franklin became active in raising troops and serving as a soldier. He argued that thirteen divided colonies could not easily maintain a coordinated defense against the unified French strategy, and called upon the colonial meeting in Albany to propose a united confederation. The Albany Convention agreed with Franklin, but not a single suspicious colony ratified the plan, and Franklin was disgusted with them. Out of all this, Franklin emerged strongly anti-French, strongly pro-British, and not a little skeptical of colonial self-rule. Too little has been written about the agonizing self-doubt he must have experienced when all of these viewpoints had to be reversed in 1775, during the nine months between his public humiliation at Whitehall, and his sailing off to meet the Continental Congress. Furthermore, as leader of a political party in the Pennsylvania Legislature, he also became vexed by the tendency of the German Pennsylvanians to vote in harmony with the Philadelphia Quakers, and against the interest of the Scotch-Irish who were eventually the principal supporters of the Revolutionary War. It must here be noticed that Franklin's main competitor in the printing and publishing business was the Sower family in Germantown. Franklin persuaded a number of leading English non-Quakers that the Germans were a coarse and brutish lot, ignorant and illiterate. If they could be sent to English-speaking schools, perhaps they could gradually be won over to a different form of politics.

Since the Germans of Germantown was supremely proud of their intellectual attainments, they were infuriated by Franklin's school proposal. Their response was almost a classic episode of Quaker passive-aggressive warfare. They organized the Union School, just off Market Square. It was eventually to become Germantown Academy. Its instruction and curriculum were so outstanding as to justify the claim that it was the finest school in America at the time. Later on, George Washington would send his adopted son (Parke Custis) to school there. In 1958 the Academy moved to Fort Washington, but needless to say, the offensive idea of forcing the local "ignorant" Germans to go to a proper English school was rapidly shelved. This whole episode and the concept of "steely meekness" which it reflects might be mirrored in the Japanese response, two centuries later, to our nuclear attack. Without the slightest indication of reproach, the Japanese wordlessly achieved the reconstruction of Hiroshima as now the most beautiful city in the modern world.

The Battle of Germantown: Oct. 3, 1777

After its brief commotion from the unwelcome French and Indian War, Germantown settled down to a 22-year period of colonial inter-war prosperity and quite vigorous growth. Most of the surviving hundred historical houses of the area date from this period, and it might even be contended that the starting of the Union School had been a beneficial stimulus.

|

| Cliveden |

Two decades passed. What we now call the American Revolution started rumbling in far-off Lexington and Concord, soon moved to New York and New Jersey. General William Howe, the illegitimate uncle of King George III, then decided to occupy the largest city in the colonies, tried to get his brother's Navy up Delaware but hesitated to persist in a naval attack on the chain barrier blocking the river. He considered but abandoned trying to outflank the New Jersey fort at Red Bank, the land-based artillery at Fort Muffling, and heaven knows what else along the twisting shaggy Delaware river. Giving up on that approach, Howe sent the navy down to Norfolk and back up the Chesapeake, landing the troops at the head of the Elk River. Washington was outflanked at the Battle of the Brandywine Creek trying to head him off, although he suffered far fewer casualties than the British. A rainstorm, presumably a fall hurricane, disrupted his planned counterattack near Paoli. So Howe invested Philadelphia, organizing his main defensive position in the center of Germantown. His headquarters were in Stenton and Morris House, General James Agnew was at Grumblethorpe The Center of British defense was at set up at Market Square where Germantown Avenue crosses Schoolhouse Lane. With Washington retreating to Valley Forge, that should take care of that. Raggedy rebels were unlikely to attack a prepared hilltop position with a river on either side, defended by a large number of British regulars.

|

| George Washington |

Washington did not look at things that way, at all. Cut off from their fleet, the British situation would be precarious until Delaware could be re-opened. He had watched General Braddock conduct with bravado an arrogant suicide mission in the woods near Ft. Duquesne, and also knew the British always based as much strategy as possible on their navy. Washington's plan was to attack frontally down the Skippack Pike with the troops under his direct command, while Armstrong would come down Ridge Avenue and up from the side. General Greene would attack along Limekiln Road, while General Smallwood and Foreman would come down Old York Road. In the foggy morning of October 3, the main body of American troops reached Benjamin Chew's massive stone house, now occupied by determined British troops, and General Knox decided this was too strong a pocket to leave behind in his rear. Precious time was lost with an artillery bombardment, and unfortunately, the flanking troops down the lateral roads were late or did not arrive at all. The forward movement stopped, then the British counter-attacked. Washington was therefore forced to retreat, but he did so in good order. The battle was over, the British had won again.

But maybe not. Washington hadn't routed the British Army or forced them to leave Philadelphia. They did leave the following year, however, and there was meanwhile no great desertion from the Colonial cause. Washington's troops suffered terrible privation and discouragement at Valley Forge, but the crowned heads of Europe didn't know that. For reasons of their own, the French and German monarchs were pondering whether the American rebellion was worth supporting, or whether it would soon collapse in a round of public hangings. From their perspective, the Americans didn't have to win, in fact, it might be useful if they didn't. But if they were spirited and determined, led by a man who was courageous and resolute, their damage to the British interests might be worth what it would cost to support them. The Battle of Germantown can thus be reasonably argued to have been an advancement of colonial goals, even if it could not be called a victory. However, when the news of Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga soon reached them, the European enemies of England decided the colonists would be useful allies.

In Germantown itself, the process of turning a military defeat into a strategic victory soon began, with severe alienation of the German inhabitants against the destructive experiences of British military occupation. After a winter of near starvation, Germantown would never again see itself as the capital city of a large German hinterland. It was on its way to becoming part of the city of Philadelphia.

Fort Washington, PA

|

| British Campaigns |

The Revolutionary War lasted eight years, so there are a half dozen Fort Washingtons, in several states. Pennsylvania's Fort Washington gets free advertising from being a stop on the Pennsylvania Turnpike at the intersection of the East-West branch and the North-South branch, near some very large shopping malls. Nevertheless, the suburbs haven't reached it yet, and it is on a series of wooded mountain ridges discouraging housing development. Another way of describing its location is that it is several miles north of Chestnut Hill along the Bethlehem Pike, a road which begins in the center of Chestnut Hill at Germantown Avenue. The Pike is quite old, with many surviving colonial-era houses and inns to liven up the trip.

A third way to describe Fort Washington is that the headquarters were at the point where Bethlehem Pike crosses the Wissahickon Creek. How's that again? How does the western Wissahickon Creek then flow uphill to Chestnut Hill? Of course, it doesn't, but the appearance takes some explaining. The northwestern end of Philadelphia is reached by two ancient roads running on ridges quite close together like the split tail of a fish. Germantown Avenue runs up one ridge, and Ridge Avenue runs up the second ridge closer to the Schuylkill. The Wissahickon runs in the gully between these two ridges and tumbles down the hill at Wissahickon Avenue, or Rittenhousetown if that is more understandable. The ridge of Ridge Avenue is essentially cut off by the creek, but engineers have put Ridge Avenue on a high arching bridge as it crosses the creek far below, and by this magic Ridge Avenue and Germantown Avenue are at about the same height most of the way. The Wissahickon Creek is really running downhill the whole way, but sort of disappears from sight and reappears as it twists through the gorges, misleading the casual visitor (or commuter). As happened so often during the Revolutionary War, Washington showed his understanding here of geography in the service of guerrilla warfare.

Since the British were headquartered in Germantown, and the Americans have camped a few miles away on the same creek, it was inevitable there would be some sort of battle in the region. Washington launched a three-pronged attack on the British soon after arriving at Fort Washington, but his troops fired at each other in the fog, and apparently, two prongs more or less got lost in the gorges. The Americans retreated, and the British consolidated their conquest of Philadelphia. They did launch one surprise attack on the American encampment (the Battle of Whitemarsh), but that was mainly a reconnoiter, given up after a few days when it became clear Washington's troops held the high ground. It really is high ground (hawk-watching platforms and all) for reasons already stated. Chestnut Hill is a pinnacle sticking up on the west side of the Creek, with the Wissahickon snaking around its base.

This really was a perfect place for Washington to aim for after the Brandywine Battle, close enough to threaten the British, located in a bowl-like valley for camping, but terminating at the top of a mountain ridge in case the British counter-attacked. And with plenty of running water from the Wissahickon. However, it was a little too close for comfort, and he withdrew across the Schuylkill into Valley Forge as a more substantial natural fortress. Valley Forge is also on a hilltop, but one sitting in the middle of the Great Valley (Route 202 to Wilmington), as the center of an angel food cake tin. No doubt, the advantages of this new location became evident to him at the earlier skirmishes of the Battle of the Clouds, and the Paoli Massacre, which occurred nearby.

In retrospect, these maneuvers and skirmishes were of little military significance, except for the major Battle of Brandywine. The lost opportunity was the chance to catch the British Army without supplies or access to the Navy, aborted by what was probably a hurricane, the so-called Battle of the Clouds. Philadelphia was lost, and the opportunity to win the war early by smashing a third British army was gone for good. The defeat of the Hessians at Trenton, the loss of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga, and a victory on the outskirts of Philadelphia might together just have finished the War. But things didn't work out, the British similarly missed some opportunities, and the war was to last another five years. Once the French allied themselves, their wealth and naval strength tended to make French priorities dominate strategy.

Nevertheless, a perfectly splendid tourist trip awaits the history buff who travels from Elkton, Maryland, where the British landed, to the Battle of Brandywine battlefield, up the Great Valley to Immaculata University where the Battle of the Clouds took place, over to the Battlefield of the Paoli Massacre, crossing the Schuylkill and going to Whitemarsh, then to Fort Washington, and back up Bethlehem Pike to Germantown Avenue, and down to the Chew Mansion. The campaign for the conquest of Philadelphia ended with the fall of Ft. Mifflin when the British fleet was finally able to re-supply Howe's army. This direct auto tour is a little out of chronological sequence, but it can be done in one day if you don't dawdle. If you slow down and spend an extra day, you can include the Moland House where Washington waited to see where General Howe was going. At the right season, there's hawk watching on the ridge at Fort Washington Park, and maybe on to Trenton, or even up the New Jersey waist to Perth Amboy on lower New York Bay, where the Howe brothers began and ended their Philadelphia adventure. That would take you past Princeton and New Brunswick, or even include a trip to the Monmouth Battleground. With this extension, you have traveled much of the extent of the Revolutionary War in the Mid-Atlantic states.

Germantown Nurses the Yellow Fever, 1793

|

| Yellow Fever, Phila |

The French Revolution continued from 1789 to 1799 and created the opportunity for a second revolution in the New World which a second overstretched European country would lose. The slaves of Haiti just about exterminated the white settlers, except for the few who escaped, taking Yellow Fever and Dengue with them. Both diseases are mosquito-borne, so they flare up in the summer and die down in the winter, although the Philadelphians who welcomed the exiles didn't know that. Yellow Fever in Philadelphia was bad in 1793, came back annually for three more years, and flared up once again in 1798. It could be easily observed to be more frequent in the lowlands, absent in the hills. Seasonal, it reached a peak in October, disappeared after the first frost. In the early fall, people died a horrible yellow death, jaundiced and bilious.

|

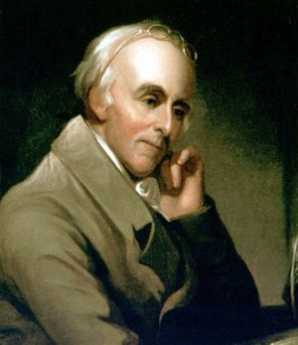

| Dr. Rush |

The Yellow Fever epidemic had a profound effect on many things. It was one of the major reasons the nation's capital did not remain in Philadelphia. It made the reputation of Dr. Benjamin Rush who announced a highly unfortunate treatment -- bleeding the victims -- thus provoking numerous anti-scientific medical doctrines based on the relative superiority of doing nothing at all. In Latin, Galen had capsulized the doctrine of Hippocrates in the "Epidemics" as premium non-nocere ("At least do no harm.") It took a full century for American scientific medicine to recover from this blow to its reputation. Whatever criticism Rush may deserve for his Yellow Fever blunder, it definitely is not true that he was a scientific lemon. Medical students are regularly surprised to learn that he is the physician who first identified and described the tropical disease of Dengue, or "break-bone fever", which was a somewhat less noticed feature among the Haiti exiles in Philadelphia. In still other scientific circles, Benjamin Rush is often referred to as the "Father of American Psychiatry". He was one of the founders of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the oldest medical society in North America. Medical colleagues who today scoff at the yellow fever episode seem to forget that Rush stayed behind to tend the sick during a devastating epidemic, while many of his more cautious colleagues fled for their lives. An unhesitating signer of the Declaration of Independence, whatever Rush did, he did courageously. Non-academic physicians have sarcastically referred to this episode ever since, as proving that "some people" think it is "better to publish than to perish".

One very good non-medical thing the Yellow Fever epidemic accomplished was to put an abrupt end to the torch-light parades of window-breaking rioters agitating, with Jefferson's approval, for an American version of the guillotine and the terror. Federalists like John Adams and William Bingham never forgave Jefferson or his admirers for this, so the class warfare movement might likely have got much worse if everyone had not suddenly dropped tools, and headed for the hilly safety of Germantown.

The President of the new republic, George Washington, was in Mt. Vernon in the summer of 1793, wondering what to do about the Yellow Fever epidemic, and particularly uncertain what the Constitution empowered him to do. He finally decided to rent rooms in Germantown and called a cabinet meeting there. His first rooms were rented from Frederick Herman, a pastor of the Reformed Church and teacher at the Union School, although he later moved to 5442 Germantown Ave, the home of Col. Franks. Jefferson chose to room at the King of Prussia Tavern.

During this time, Germantown was the seat of the nation's government. As was fervently hoped for, the cases of yellow fever stopped appearing in late October, and eventually, it seemed safe to convene Congress in Philadelphia as originally scheduled, on December 2.

Although Germantown was badly shaken by the experience, it was a heady experience to be the nation's capital. Meanwhile, a great many rich, powerful and important people had come to see what a nice place it was. Germantown then entered the second period of growth and flourishing. Walking around Germantown today is like wandering through the ruins of the Roman forum, silently tolerant of visitors who would have never dared approach it in its heyday.

REFERENCES

| Benjamin Rush: A Discourse delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Thomas A. Horrocks ASIN: B0006FCBXS | Amazon |

| Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague Of Yellow Fever In Philadelphia In 1793: J.H. Powell ISBN-13: 978-1436715881 | Amazon |

| Germantown and the Germans: An Exhibition from the Collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia: Edwin, II Wolf ISBN-13: 978-0914076728 | Amazon |

German Origins of the Philadelphia Orchestra

|

| academy of music |

The histories of the Academy of Music and the Philadelphia Orchestra are distinct but intertwined. At the moment, the Orchestra owns the Academy, but it was not always so. The Academy of Music of Philadelphia was built in 1857, but the Philadelphia Orchestra was not founded until 1900, just for instance.

It is undeniable however that Philadelphia orchestral music began its present direction with the German immigration wave of 1848, bringing with it the new musical concepts of Felix Mendelssohn. Except for the wedding march which has sent innumerable brides down the aisle, most people now have a little trouble naming a piece of music written by this composer, but in fact, he produced twenty to fifty pieces a year from 1820 to 1847. In terms of pure virtuosity, Mendelssohn was probably the most prolific and gifted composer after Mozart. His lack of really notable productions has sometimes been attributed to his wealthy childhood and too-easy success, but in his day he was nonetheless a musical revolutionary with an enormous following.

|

| Musicians |

One of the orchestras in the Mendelssohn tradition was the Germania Orchestra which moved to Philadelphia but had trouble getting accepted, and disbanded. The members of the orchestra scattered and eventually reformed a Philadelphia Germania Orchestra, which largely took over the place and some of the members of the disbanded Musical Fund Orchestra, struggled for a few years, became part of Henry G. Thunder's Orchestra, which in turn was almost entirely taken over by Fritz Scheel's Philadelphia Orchestra. Even with this thoroughly local name, the Orchestra struggled for a few years, and would quite likely have dissolved into still other formulations, until the local Women's Committee took matters in hand. Leadership was provided by Fanny Wister, sister of Owen Wister the novelist, and granddaughter of Fanny Kemble. From that time on, particularly from the day of the hiring of Leopold Stokowski as a conductor, the Philadelphia Orchestra has pressed forward, and never looked back.

Quaker Efficiency Expert: Frederick Winslow Taylor 1856-1915

|

| F.W. Taylor |

For at least seventy-five years after Fred Taylor turned it down, any rich smart Philadelphia Quaker attending Phillips Exeter would have been automatically admitted to Harvard. We don't know why he did it, but instead F.W. Taylor just walked a few blocks down the hill from his Germantown house and got a job at the Midvale Steel Company as an apprentice patternmaker. During the twelve years, while he rose to become chief engineer of the company, he took a correspondence course for a degree in mechanical engineering at Stevens Institute and invented a process for making tungsten steel, called high-speed steel. That made Midvale Steel rich, but Taylor was going to make Philadelphia rich, and after that, he was going to make America rich. When he died, he was widely hated.

Evidently his lawyer father greatly admired German efficiency, having sent little Freddy to a famous Prussian boarding school where he was in attendance at the time of the

|

| General von Moltke |

Battle of Sedan. General von Moltke had used Prussian efficiency and discipline to defeat those indolent lazy French, and Fred Taylor evidently absorbed and retained these stereotypes for the rest of his life. Whatever he was looking for at Midvale Steel, what shocked him most was to find workers "soldiering on the job". That's a Navy term, by the way, invented by sailors to describe the useless shipboard indolence of any Army they were transporting. Taylor later went to Bethlehem steel, reduced the number of yard workers from 500 to 180, and was promptly fired. It seems that most of the foremen at the plant were owners of local rental houses, which were emptied of tenants when Taylor reduced the workforce. Even management came to mistrust Taylor. When the railroads wanted a rate increase, Louis Brandeis defeated them with the argument that they wouldn't need higher rates if they adopted Taylor's system of efficiency. In his later years after he became enormously rich, he toured the country giving speeches without fees, promoting the doctrine of finding the one best way and then doing everything that way.

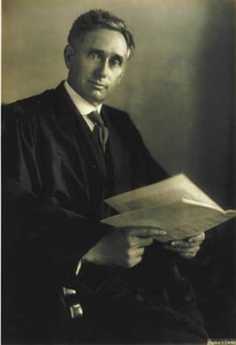

|

| Louis Brandeis |

Over time, Frederick Taylor had come to see that the industrial revolution had proceeded to the factory stage by merely bringing craftsmen indoors, each one treasuring his little trade secrets. Bringing the point of view of the company's owners onto the shop floor, Taylor could see how vastly more profitable the steel company would be if all those malingering tradesmen would stop soldiering on the job. No doubt the young Quaker soon learned that little was to be accomplished by remonstrating with workers, just as bellowing foremen had learned that bullying was also useless. Out of all this familiar scene emerged Taylorism, the idea of paying financial incentives to those who produced more, splitting the rewards of efficiency with the management. It sort of worked, but it didn't work enough to satisfy F.W. Taylor. When he walked around with a stopwatch, he collected the data showing how much more might be produced if the workers were perfectly efficient. Not only did that create the stereotype of the stop-watch efficiency expert, but it also provoked Congressional hearings and federal law against stopwatches which stayed on the books from 1912 to 1949. Although management responded by forming dozens of Taylor Societies to honor the approach, the unions invented the term "Taylorism" and bandied it about as the worst sort of epithet. Curiously, the Taylor approach proved to be enormously appealing both to Lenin and Stalin, who applied it as a central part of their five-year plans and general approach to industrialization. As we now all recognize, the Communist approach was a two-tier system instead of the three-tier system that was needed. It isn't enough to have a class of comrades called planners and another called workers; you need a layer of foremen, sergeants and chief petty officers in the middle. In addition to the elaborate time and motion studies leading to detailed written procedures, there needs to be an institutional memory for the required skills of the trade. In a funny sort of way, Fred Taylor the Quaker may have organized the downfall of the communist state before it was invented.

|

| Herbert Hoover |

Another peculiar outgrowth of Taylorism may be the partisan lines of our own political parties. If you trace the American ideological divide to the 1932 election of Franklin Roosevelt, you can see we are still fighting the battles of the depression. It happens that Herbert Hoover, another Quaker, was totally captivated by Taylorism. Not only that, he was adamant that to get rid of the depression all the country needed was to return to self-reliance, individual responsibility, and hard work. Those were qualities Hoover himself had in superabundance. One telling remark that he probably regretted saying but nonetheless firmly believed was, "If a man hasn't made a million dollars by the time he is forty, he can't amount to much." Franklin Roosevelt had the million all right, but his family had given it to him. The Cadburys and Clarks could have given it to Fred Taylor, too, but he chose to make it himself.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1296.htm

Harvard Progressives in Philadelphia

|

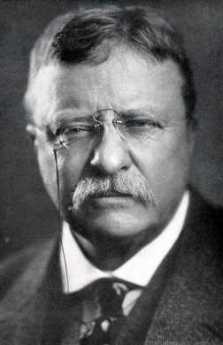

| Theodore Roosevelt |

The Progressive movement of the early 20th century is most concisely viewed as a futile social reaction to the vast changes in America caused by urbanization and industrialization after the Civil War. The transcontinental railroad threatened to destroy the wild, wild West, but the enduring environmental movement had overtones of even greater hostility toward industrialization, the cause of it all. In this sense, it joined forces with socialist and labor reform movements, in hating the newly rich, the spoilers, the Robber Barons. It briefly shared sympathies with anti-immigrant groups, while simultaneously expressing great sympathy with the decisions of the people, as opposed to corrupt politicians. There was a strong Calvinist streak in Progressivism, linked back to New England and Harvard its intellectual center. Regardless of any other contradiction, it reflected the viewpoint of Theodore Roosevelt. Teddy Roosevelt, "that damned cowboy" in the view of conservatives, did not invent the ideas of Progressivism, but he surely personified them, illustrated them in action. This confused turmoil of resentments was knocked off the front pages by a real threat to European civilization, the First World War. A terrifyingly well organized German war machine took the place of Robber Barons as a symbol of what was wrong with the world. The crash of 1929 and its ensuing long depression finally put an end to older controversies; it pushed the "reset" button.

|

| Henry Brooks Adams |

To understand the position of Philadelphia's upper crust during the Progressive era, four or five names need to be fleshed out. Owen Wister and J. William White would be important Philadelphia links to the Bostonians Henry Adams and Henry James. All of them were leading literary figures, and all of them were close friends of Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt, it might be recalled, was the author of thirty-four books. This little group of literary giants were members of the leading families of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia; what they said, mattered. Although today Owen Wister is mainly known as the author of The Virginian, the first of the cowboy stories of the Wild West, he was, in fact, an observer of the social climates of not only the West, but the deep South (Lady Baltimore ), and the East Coast ( Romney). Some idea of his political leanings can be gleaned from his presidency of the Immigrant Restriction Society, and the authorship of an article called Shall We Let the Cuckoos Crowd Us From Our Nest . Wister has been called "the best born and bred of all modern writers", referring to his descent

Contemporary Germantown

The Strittmatter Award is the most prestigious honor given by the Philadelphia County Medical Society and is named after a famous and revered physician who was President of the society in the 1920s. There is usually a dinner given before the award ceremony, where all of the prior recipients of the award show up to welcome to this year's new honoree.

|

| Bockus |

This is the reason that Henry Bockus and Jonathan Rhoads were sitting at the same table, some time around 1975. Bockus had written a famous multi-volume textbook of gastroenterology which had an unusually long run because it was published before World War II and had no competition during the War or for several years afterward; to a generation of physicians, his name was almost synonymous with gastroenterology. In addition, he was a gifted speaker, quite capable of keeping an audience on the edge of their chairs, even though after the speech it might be difficult to recall just what he had said. On this particular evening, the silver-haired oracle might have been just a wee bit tipsy.

Jonathan Rhoads had likewise written a textbook, about Surgery, and had similarly been president of dozens of national and international surgical societies. He devised a technique of feeding patients intravenously which has been the standard for many decades, and in his spare time had been a member of the Philadelphia School Board, a dominant trustee of Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, and the provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Not the medical school, the whole university, and is said to have been one of the best provosts of the University of Pennsylvania ever had. When he was President of the American Philosophical Society, he engineered its endowment from three million to ten times that amount. For all these accomplishments, he was a man of few words, unusual courtesy -- and a huge appetite in keeping with his rather huge farmboy physical stature. On the evening in question, he was busy shoveling food.

"Hey, Rhoads, wherrseriland?". Jonathan's eyes rose to the questioner, but he kept his head bowed over his plate.

"HeyRhoads, Westland?" The surgeon put down his fork and asked, "What are you talking about?"

"Well," said Bockus, "Every famous surgeon I know, has a house on an island, somewhere. Where's your island?

"Germantown," replied Rhoads, and returned attention to his dinner.

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |