Related Topics

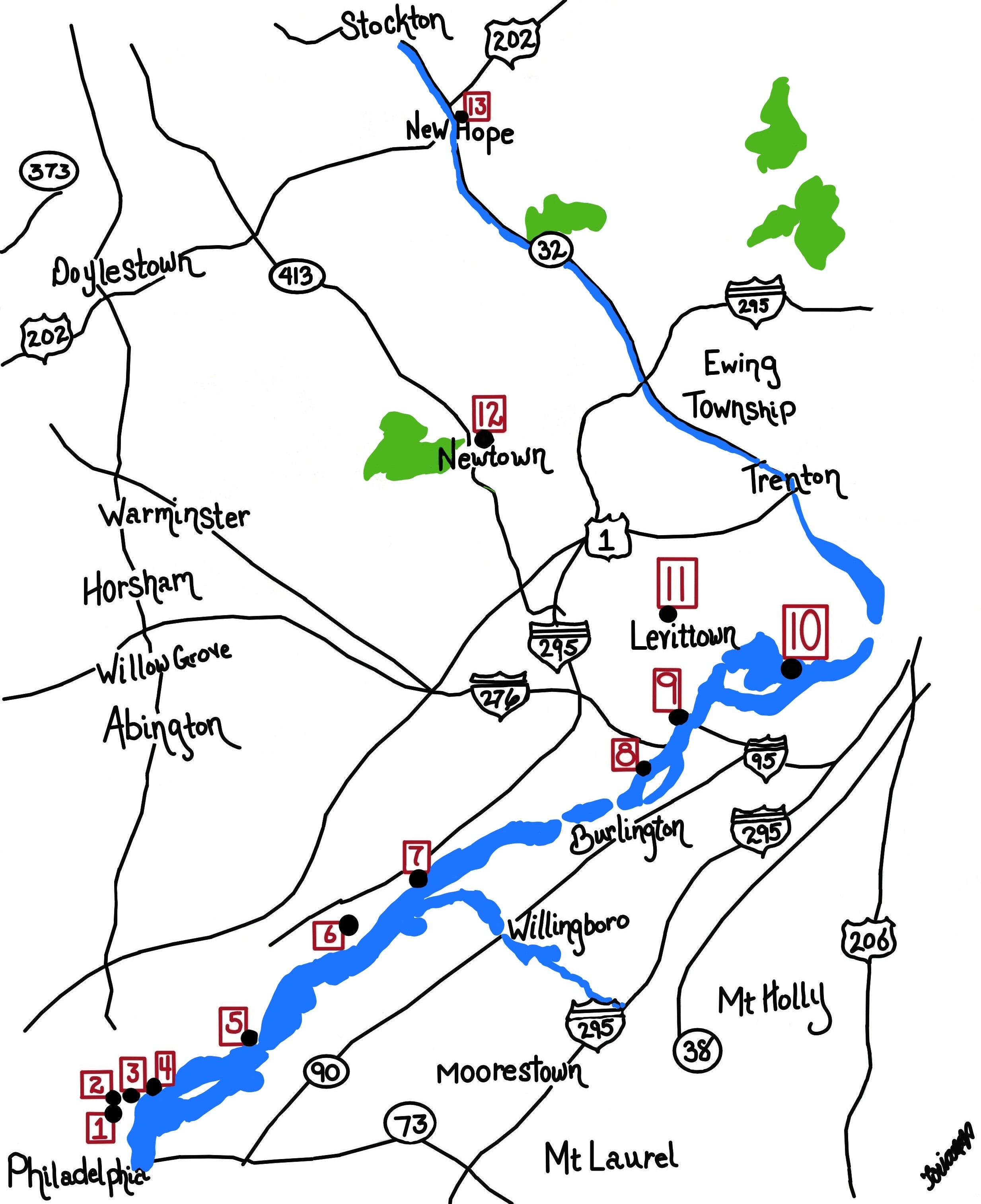

Philadelphia's River Region

A concentration of articles around the rivers and wetland in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

To Germantown, a Short Appreciation

Seven miles from the heart of Philadelphia, Germantown was once a separate town, the cultural center of Germans in America. Revolutionary battles were fought here, it was briefly the capital of the United States, and it still has an outstanding collection of schools and colleges.

Right Angle Club: 2013

Reflections about the 91st year of the Club's existence. Delivered for the annual President's dinner at The Philadelphia Club, January 17, 2014.

George Ross Fisher, scribe.

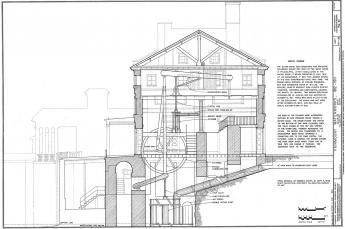

Taming the Creeks of Olde Philadelphia

For the past ten years, the Morris Arboretum has sponsored a mini-bus tour of the sewers of Philadelphia conducted by Adam Levine. In spite of its name, it attracts a pretty high-brow audience, who have a perfectly wonderful experience. Adam has been a consultant to the Water Department for decades, and he gives a pretty polished tour, which anyone interested in the City really ought to join some year. He's planning to write a book about it, someday, and instead of giving away all the best stories, I bet it will swell attendance at the tours considerably. Some of us know that writing books can be pretty hard work, however, while giving tours seems like a lot of fun.

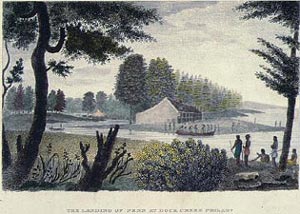

When William Penn picked out this area for his new city, there were herds of swans swimming in the Delaware River around the mouth of the Schuylkill, and there were wide mud flats thrown up around what we call the airport, by the slowed waters making a big turn there. Although Mr. Penn originally planned to settle at what we now call Chester, apparently he thought the protected river above the mud flats would be a safer harbor. In the area of Philadelphia County in Penn's time, there were about three hundred miles of creeks, now reduced to about one hundred by the Water Department and the Department of Streets. Dock Creek was the main seaport at first, and it eventually became Dock Street by putting the creek into a culvert. In a sense, that is what has been happening for three hundred years, all over town. At first, the creeks supplied drinking water, and then they became sewers, and then they became streets on top of sewers.

As a matter of fact, there were further steps in the process. The railroads were laid on the banks of creeks, to reduce the amount of excavation and fill-in required. And as factories were built along the creeks to take advantage of the transportation and water power, the run-off of sewage was mixed with ground-water runoff, in what is delicately spoken of as a "combined sewer". The water department spends most of its time and money nowadays, separating rainwater sewage from the real thing, and diverting the rainwater into ponds and other catchment hollows, where the relatively clean water percolates through the soil and cleans itself up. The real sewage is diverted into massive pipe systems leading to the sewage disposal plants. Where, would you believe it, it gets cleaned and chlorinated and returns as drinking water -- purer than the river water that flows past, by a good bit.

But that gets ahead of the story somewhat. As the factory areas become liveable, the sewers encased in the pipe are at the bottom, the rail lines are somewhat higher. Where there were no railways, the electrical and water pipes are high above it all and often get encased in concrete. However, we can expect combined sewers to last a long time, since it is estimated that the project of uncombining two-thirds of the sewer system will cost several billion dollars, and require twenty-five years to complete. The infrastructure money from the "Stimulus package" will be a forgotten episode of the past when this project is finished. Philadelphia likes straight streets aligned in grids, so you can almost be certain you are over a creek bed when the road gets crooked in Philadelphia.

Now, look at the grid of streets from the point of view of a Water Department engineer. Somebody gave the process the name of a waffle, and it is very apt. As the straight streets go as straight as they can, they cut through hills and fill up the gullies. The fill from the hills is used for the valleys, so the straight grid streets are generally somewhat higher than the residential areas, giving the waffle effect, but leaving half of the houses with a sharp embankment in their lawns going down to street level, and the other half of the houses with water in their basements. It's up to the house builder to fill up the depression between the streets, with the streets nevertheless somewhat higher than the depressions. Sometimes the streams cut through, and are encased in pipes as they go under the streets. Sometimes it's just too much to handle, and we get green parks scattered around the city, breaking up the monotony of row houses, for a generally pleasing effect not seen in flat areas, like New Jersey.

The city has two watersheds, one draining into the Delaware River, and the other draining into the Schuylkill. And the trail between the two watersheds, the continental divide if you please, is Germantown Avenue.

Originally published: Monday, September 30, 2013; most-recently modified: Friday, May 03, 2019