2 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Rt. Angle by Years

The history of Philadelphia"s finest men's club.

Right Angle Club: 2013

Reflections about the 91st year of the Club's existence. Delivered for the annual President's dinner at The Philadelphia Club, January 17, 2014. George Ross Fisher, scribe.

To My Fellow Right Anglers

Greetings, Right Anglers, and be of good cheer

We have just completed our 91st year

But there is no cause to fear

President's Letter for 2013

|

| Daniel Sossaman |

Dear Right Anglers,

Another successful Right Angle year is ending, our 91st year, and the start of our 92nd year. Forty-two successful luncheon meetings full of good camaraderie, good cheer, good food, good jokes (thanks to Tom Howes), good speakers (thanks to Carter Broach) and a good time was had by all. The issue of where we would meet in the Racquet Club was resolved. We still meet in the good old Rathskeller every Friday at 12:33.Thanks to Jack Foltz, First Vice President. for his advice and counsel throughout the year. Jack is foregoing the President's position for 2014 to take care of personal issues. He would have made a great president, perhaps, next year.

Our Second Vice President Dave Richards, events chair, ran three excellent events. The Spring Fling at Harriton House took place on a rainy day just perfect for an English garden party. The pig was great. And we all had the opportunity to tour Harriton House. Our Fall Fling was on the USS Olympia. We enjoyed good weather, good food and drink on the fantail. A tour of the Olympia topped the day. Those of us of a limber nature crawled through the submarine USS Becuna, what a treat. Our Christmas party at the "cozy" Italian restaurant ended the events year in fine fashion. Once again, fine food, good drinks, and our own good company. What more could we have asked for, "Crackers!" We got them with a bang. Thanks, David!

,p> Third Vice President, Carter Broach, our speaker chair, did not run out of friends, fellows, and acquaintances to treat us to forty-two Fridays of outstanding speakers. We were well entertained and enlightened on a myriad of topics. Our speakers continued to receive our coveted Right Angle plate along with some appropriate comments.Our Fourth Vice President, Dan Sossaman II, ran an honest raffle. At least two of us were happy every Friday. The rest of us looked forward to the next Friday to see what fate would bring us. Our charity received a nice check from our raffle receipts. Neale Bringhurst, our corresponding secretary, kept us informed and up to date on our next month's speakers on a timely basis. He also kept us advised of new members elected.

Mel Buckman, our Recording Secretary, kept timely and accurate minutes of our board meetings. No issues with Mel's minutes. Our Treasurer, Rod Rothermel, kept us informed and up to date on our financial matters and Treasury Department. His cogent comments concerning receipts, expenses, and planned expenditures keep our finances in line. Rod is stepping down as Treasurer after many years of true and faithful service. Rod always kept us informed, enlightened and entertained as to our financial condition. He will be missed.

Our board members, David McCormick Archivist, Bill Hill, Tom Williams, Wayne Strausbaugh, and Ted Laws were vital members of the board. Their wise counsel and advice was evident at all board meetings.

The Racquet Club continues to provide an outstanding mid-day repast. Even though retired, Rosie faithfully served our needs at all our Friday luncheons and meetings.

We continued to have at least one evening meeting and one new member cocktail party. It is hoped the evening meetings and new member events will continue.

A number of new members joined this year and our membership continues strong (though we will always need a few more good men). Past president, John White, continued to run our constant contact service for all our events. This continues to make signing up for the flings a quick and easy process. John should be thanked by all.

Finally, Leanne Lindsey should be remembered for all she does in supporting our "back room" operations. This year's nominating committee was chaired by Past President, John Fulton ably assisted by Ed Ermilio and Dick Pascal. They have recommended a fine slate of new officers and Board members for next year. With David Richards taking over as President, we should have an outstanding 92nd year.

Your Most Obedient Servant,

Daniel Maguire Sossaman, SR

Sergeant Major USA (Ret)

91st President

Ruminations About the Children's Education Fund (3)

The Right Angle Club runs a weekly lottery, giving the profits to the Children's Educational Fund. The CEF awards scholarships by lottery to poor kids in the City schools. That's quite counter-intuitive because ordinarily most scholarships are given to the best students among the financially needy. Or to the neediest among the top applicants. Either way, the best students are selected; this one does it by lottery among poor kids. The director of the project visits the Right Angle Club every year or so, to tell us how things are working out. This is what we learned, this year.

The usual system of giving scholarships to the best students has been criticized as social Darwinism, skimming off the cream of the crop and forcing the teachers of the rest to confront a selected group of problem children. According to this theory, good schools get better results because they start with brighter kids. Carried to the extreme, this view of things leads to maintaining that the kids who can get into Harvard, are exactly the ones who don't need Harvard in the first place. Indeed, several recent teen-age billionaires in the computer software industry, who voluntarily dropped out of Harvard seem to illustrate this contention. Since Benjamin Franklin never went past the second grade in school perhaps he, too, somehow illustrates the uselessness of education for gifted children. Bright kids don't need good schools or some such conclusion. Since dumb ones can't make any use of good schools, perhaps we just need cheaper ones. Or some such convoluted reasoning, leading to preposterous conclusions. Giving scholarships by lottery, therefore, ought to contribute something to educational discussions and this, our favorite lottery, has been around long enough for tentative conclusions.

|

Just what improving schools means in practical terms, does not yet emerge from the experience. Some could say we ought to fire the worst teachers, others could say we ought to raise salary levels to attract better ones. Most people would agree there is some level of mixture between good students and bad ones. At that point, the culture mix becomes harmful rather than overall helpful; whether just one obstreperous bully is enough to disrupt a whole class or something like 25% of well-disciplined ones would be enough to restore order in the classroom, has not been quantitatively tested. What seems indisputable is that the kids and their parents do accurately recognize something desirable to be present in certain schools but not others; their choice is wiser than the non-choice imposed by assigning students to neighborhood schools. Maybe it's better teachers, but that has not been proved.

|

It seems a pity not to learn everything we can from a large, random experiment such as this. No doubt every charity has a struggle just with its main mission, without adding new tasks not originally contemplated. However, it would seem inevitable for the data to show differences in success among types of schools, and among types of students. Combining these two varieties in large enough quantity, ought to show that certain types of schools bring out superior results in certain types of students. Providing the families of students with specific information then ought to result in still greater improvement in the selection of schools by the students. No doubt the student gossip channels already take some informal advantage of such observations. Providing school administrations with such information also ought to provoke conscious improvements in the schools, leading to a virtuous circle. Done clumsily, revised standards for teachers could lead to strikes by the teacher unions. Significant progress cannot be made without the cooperation of the schools, and encouragement of public opinion. After all, one thing we really learned is that offering a wider choice of schools to student applicants leads to better outcomes. What we have yet to learn, is how far you can go with this idea. But for heaven's sake, let's hurry and find out.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Delaware Valley

|

It seems unlikely a peanut farmer from Georgia would have much interest in Philadelphia, let alone the activities of its local Army Corps of Engineers. But it seems there is some sort of story, there. An acquaintance chairing a local meeting of Americans for Democratic Action at the time remembers an episode dating from the 1976 presidential nominating campaign. Morris Udall was the main opponent of Jimmy Carter for the Democrat nomination. You might suppose an out of town politician would have instincts tell him to be nice to the local mayor of his own party, but Jimmy Carter went out of his way to attack Frank Rizzo. Udall took the path of conventional wisdom and refrained from joining Carter in the attack. Since Pennsylvania votes were considered pivotal in that particular race, it was watched with considerable interest. But to the surprise of the insiders, Carter won the Pennsylvania votes, suggesting that hidden animosity to Rizzo was extensive. Furthermore, from that event, it would be possible to suppose either of two conclusions. Either Carter would be grateful to Pennsylvania for putting his nomination over the top, or else he had some sort of grievance against Rizzo.

Subsequent events suggest he had a grievance, but it would be very hard to imagine where the two would even have met each other in the past. More likely, he made some slighting remark to an aide, who took it on himself to curry favor when in fact Carter had forgotten all about it.

|

| U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

In any event, the local division of the Army Corps of Engineers went into some sort of decline, dating from about that time, which might well have been over-reacting to the so-called Love Canal episode. The chief of the division was to have no higher rank than Lt. Colonel. The activities of the division had been centered on building dams and flood control projects but began to be mostly environmental protection, particularly repair of hurricane-damaged ocean beaches. The headquarters was moved from the Custom House to the Wanamaker Building because the personnel and budget had declined. There was the talk of merging the district with another district. The Delaware Division is the smallest district in the country, almost difficult to find on a map whereas some other districts enclose eight states. When you get more states you get more Senators, so you get more budget, and so on. It was sad that the Navy and Marines were founded here, the Revolution and the War of 1812 caused many fortifications to be centered here, the capital of the country. From that point to the present, there has been a long decline. It was particularly painful that West Point is primarily an engineering college, with a tradition that the top five percent of every class is offered a place in the Corps of Engineers. In Army politics, it is clear that a heavy proportion of the generals were West Point graduates, just as it is almost exclusively true that all admirals have Annapolis in their background. Jimmy Carter went to Annapolis, but so what?

|

| Love Canal |

Rather than follow a line of thought which leaves many uncomfortable, perhaps it is more relevant to notice that all of our rivers seem to be drying up. Colorado and the Rio Grande are mere trickles, the Mississippi now has wide banks of mud. Delaware has long been recognized as having a wide mouth and a short length, reflecting its origin as a small river emptying (at Trenton) into a wide bay which is really the back bay of the huge barrier peninsula of Southern New Jersey. What might have been its extensive watershed runs instead into the Susquehanna, about a hundred miles north of Philadelphia, probably because of volcanic shifts? But what was once a thriving port has dwindled as a result of labor troubles and some unfortunate legislation. That's where the number of Senators in your district makes a difference.

|

| Panama Canal |

Wilmington, Delaware has the largest port for bananas in the nation; Delaware points southward, toward all of Latin America. The Chinese are financing, and probably engineering, a widening of the Panama Canal to accommodate giant container ships that now can't get through. The first port on the Atlantic seaboard to deepen its harbor accordingly, will probably get first-mover advantage and hold it because it is expensive to play catch up. Philadelphia is about half-finished in the deepening of the channel to forty-five feet. But New York's deepening of the Hudson is almost complete. New Jersey politics involves both channels on its north and south borders, but New Jersey has long since thrown in its lot with New York. Now that it probably won't matter, the Pennsylvania dredging will probably be permitted to finish. If that happens, the only hope for Philadelphia in the race to be a big container port will depend on a recession in China slowing down their import traffic until we catch up. After all, Philadelphia is blessed with an almost world-unique combination of rail, highway, airport, and ocean shipping interchanges at a single point, on relatively undeveloped land close to a major city. Without wishing any evil on China, we do have to wish they would encounter some reason to slow down for us. Slow down, that is until our natural advantages can overcome the foibles of our politicians.

Wistar Institute, Spelled With an "A"

|

| Dr. Russel Kaufman |

The Right Angle Club was recently honored by hosting a speech by Dr. Russel Kaufman, the CEO of the Wistar Institute. Dr. Russel is a charming person, accustomed to talking on Public Broadcasting. But Russel with one "L"? How come? Well, sez Dr. Kaufman, that was my idea. "When I was a child, I asked my parents whether the word was pronounced any differently with one or two "Ls", and the answer was, No. So if I lived to a ripe old age, just think how much time and effort would be wasted by using that second "L". In eighty years, I might spend a whole week putting useless "Ls" on the end of Russel. I pestered my parents about it to the point where they just gave up and let me change my name". That's the kind of guy he is.

|

| The Wistar Institute |

The Wistar Institute is surrounded by the University of Pennsylvania, but officially has nothing to do with it. It owns its own land and buildings, has its own trustees and endowment, and goes its own academic way. That isn't the way you hear it from numerous Penn people, but since it was so stated publicly by its CEO, that has to be taken as the last word. It's going to be an important fact pretty soon since the Wistar Institute is soon going to embark on a major fund-raising campaign, designed to increase the number of laboratories from thirty to fifty. The Wistar performs basic research in the scientific underpinnings of medical advances, often making discoveries which lead to medical advances, but usually not engaging in direct clinical research itself. This is a very appealing approach for the many drug manufacturers in the Philadelphia region, since there can be many squabbles and changes about patents and copyrights when the commercial applications make an appearance. All of that can be minimized when fundamental research and applied research are undertaken sequentially. Philadelphia ought to remember better than it does, that it once lost the whole computer industry when the computer inventors and the institutions which supported them got into a hopeless tangle over who had the rights to what. The results in that historic case visibly annoyed the judge about the way the patent infringement industry seemingly interfered with the manufacture of the greatest invention of the Twentieth century.

Patents are a tricky issue, particularly since the medical profession has traditionally been violently opposed to allowing physicians to patent their discoveries, and for that matter, Dr. Benjamin Franklin never patented any of his many famous inventions. But the University of Wisconsin set things in a new direction with the patenting of Vitamin D, leading to a major funding stream for additional University of Wisconsin research. Ways can indeed be devised to serve the various ethical issues involved since "grub-staking" is an ancient and honorable American tradition, one which has rescued other far rougher industries from debilitating quarrels over intellectual property. You can easily see why the Wistar Institute badly needs a charming leader like Russel, to mediate the forward progress of our most important local activity. From these efforts in the past have emerged the Rabies and Measles vaccines, and the fundamental progress which made the polio vaccine possible.

It was a great relief to have it explained that there is essentially no difference at all between Wisters with an "E" and Wistars with an "A". There were two brothers who got tired of the constant confusion between them, see and agreed to spell their names differently. When the Wistar Institute gathered a couple of hundred members of the family for a dinner, the grand dame of the family declared in a menacing way that there is no difference in how they are pronounced, either. It's Wister, folks, no matter how it is spelled. Since not a soul at the dinner dared to challenge her, that's the way it's always going to be.

Musical Theatre at the 11th Hour

|

| Michael O'Brien |

Philadelphia is having a theatrical revival, very likely leading the cities of America in that regard. One of the central movers and shakers of that movement visited the Right Angle Club recently. Touting his own company, without a doubt, but nevertheless illuminating a movement which seems pretty central to Philadelphia's future. Michael O'Brien is the Producer and Artistic Director of the 11th Hour Theatre Company, which had its origin eight years ago in the Studio of the Walnut Street Theatre, and has since spread out to many venues within Philadelphia. Since Mike O'Brien got his start in theater at the Walnut, it is only fair to say the Walnut Street Theatre was a parent of the 11th Hour. The 11th Hour is a 501(c) (3) nonprofit corporation, so it sort of sounds as though the William Penn Foundation was somewhere in the background, at least at one time.

The 11th Hour Theatre Company is one of 1200 theater companies now active in Philadelphia but is the only company dedicated exclusively to musicals. More finely tuned than that, it specializes in small productions with five or six members of the orchestra, and about the same number of actor/singers on stage. It happens there aren't very many such productions to chose among, so someone must stimulate more composers to pay attention, or the 11th Hour could run out of musicals to produce. Some of this is economic. The kind of big-time musical comedy which makes a gazillion dollars with a huge cast, huge orchestra, huge scenery is very expensive to produce, and probably soon runs out of audience members who are willing to pay huge ticket prices for anything except a huge production success, produced at huge financial risk. For the most part, the national market will only profitably support one or two of those a year, with the consequence that lots of people lose a lot of money on the ones which fail, and most of the successes are rescued by movie and television revenue, which involve further financial risk-taking. Apparently, the successful composers either try to claw their way to the big brass ring or else look for other lines of work. Someone may eventually figure out a way to start with a small musical and then scale it up to the big-time, but what has happened seems to be that actors and musicians who shrug off the big time, cluster together and try to produce a career which prefers a normal sort of home life, to the neurotic struggling which seems inherent in those who consider themselves big-time theatrical material. Somehow, the dictionary definition of the 11th Hour -- the time when most creativity appears -- has instant appeal to the sort of person who prefers to live a normal life within a close circle of like-minded friends and finds that to be a possibility in Philadelphia. We'd like to remind him you can't fill the seats of a theater without an enthusiastic audience, but it's nice to hear our town is a congenial place to live and be an actor.

|

| 11th Hour Theater |

Michael O'Brien regards the theatrical revival of Philadelphia to be part of the restaurant revival of the 1980s. Just as the nightlife of Philadelphia was once centered around coming to town to go to the movies, Mr. O'Brien regards the theater as the centerpiece of an evening in town for a couple who want to come for exotic food, plus some entertainment. We have night clubs and celebrity concerts for the dating set, but a quiet dinner followed by the theater appeals to a different, somewhat older set. Once this movement gets started, performers arrive from out of town and discover they like the sort of life entertainers enjoy here, so they stay. And many graduates of local colleges and universities grow up close enough to the scene that they decide they never want to leave. Naturally, a producer and artistic director has the perspective of the performing community and tends to emphasize the attractiveness of Philadelphia to performers. In addition to that, of course, enough dumb old plain citizens have to be attracted to the theatrical product, in order to provide audiences for 1200 theatrical companies; and novelty alone is not enough to sustain that. Some such mutual need was once provided by the sudden Elizabethan flowering of the theater of London, and five hundred years later no one has completely explained it. But for comparison, in Shakspere's day, there were fifty-nine London theaters at the height of the Elizabethan boom, but only two in Paris.

Wizards of the Wissahickon

|

| Peace Treaty of Westphalia |

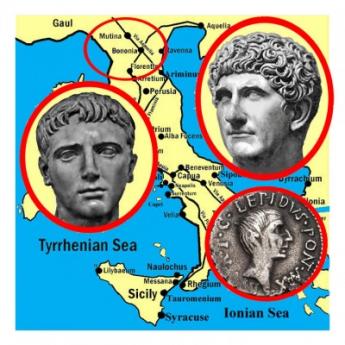

The Holy Roman Empire comprised about 120 little kingdoms along the Rhine River, mostly Germanic, stretching from Amsterdam to Switzerland, and loosely associated with the Papal States extending onward to Sicily. Napoleon and Bismark unified much of this territory into what we might now recognize as a map of Western Europe. Before that, it had been roughly the battleline between Catholic and Protestant populations, provoked by the influence of Martin Luther spreading through what had for centuries been an entirely Catholic region. After the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, it became a rule of the Holy Roman Empire that the state religion of a country was whatever the local king said it was.

With this history and more, it is unsurprising that the region was filled with small stranded religious sects who were out of local secular favor. William Penn's mother was Dutch, so he could speak the local language and had lived in the region. When this immensely rich Englishman acquired the colony of Pennsylvania, it was natural for him to offer religious sanctuary to Germanic sects as well as to the dissident Quakers of England, in that free-religion colony he planned for his wilderness region, larger than the whole of England.

|

| Johannus Kelpius |

From this history it emerges that "Dominie Johann Jacob Zimmerman, a noted German mathematician, astronomer, and defrocked Lutheran minister", led a remarkably well-educated group of "Pietists, millennialists, Rosicrucians, and Separatists" to London and then to Rotterdam, picking up some Swiss, Transylvanians, Swedes and Finns. Among them was a young Transylvanian scholar originally named Kelp, which in scholarly tradition had changed to Johannus Kelpius. Responding to the astronomical calculations of Zimmerman, it was believed the millennium of peace and tranquility predicted by the Book of Revelations would begin more or less immediately. The group resolved to accept the offer of William Penn and go to Pennsylvania to enjoy that millennium. Unfortunately, Zimmerman died as the ship was departing and young Kelpius, who himself was later to die of tuberculosis at the age of 34, was appointed the new leader.

|

| Kelpius Cave |

Evidently, on arrival in Philadelphia in 1694, they encountered earlier inhabitants who had a tradition of a bonfire midway between the solstice and the equinox. Their fire was on top of "Fire Mount", and was taken as a sign that the millennium was now beginning. The group moved up to the top of the Wissahickon, next to where Rittenhousetown is now to be found, and just beyond it in Roxborough was a hollowed out formation resembling an amphitheater. It is now believed an astronomical observatory was created on the projecting rock next to the present foot of the Henry Avenue bridge; it was at that place that two celibate monasteries (for men and for women) lived together, slowly dying out as celibate communities necessarily do. Eventually, the death of Kelpius caused the final break-up of the little colony, but not before it had established itself as a center of music, poetry, and literature for the growing Germanic settlers of the surrounding states. One group of them went further west to the Cloister at Ephrata, and others scattered in different directions. It is notable that a great many names of settlers in the Kelpius colony are still to be found in Germantown, Philadelphia, and Harrisburg, although tracing the genealogy has been difficult. Some of the music has been found in scraps and reconstructed, and discovered to be quite sophisticated and beautiful, although precise authorship remains uncertain.

REFERENCES

| An Introduction to the Music of the Wissahickon Glen: Lucy E. Carroll, DMA, | Kelpius Society |

| The Hymn Writers of Early Pennsylvania: Lucy E. Carroll, ISBN: 978-1606475201 | Amazon |

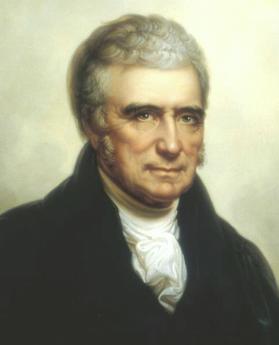

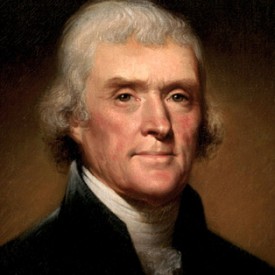

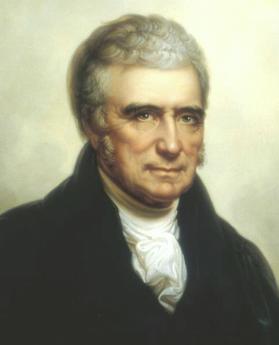

John Marshall Decides Three Cases

|

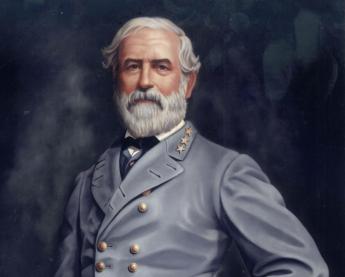

| Chief Justice John Marshall |

John Marshall, taking sixteen years to do it, transformed the Constitution internally into the cornerstone of the Rule of Law, making the legal profession its guardian. Nine respected justices now essentially hold lifetime appointments as bodyguards of the structure Marshall designed, with all lawyers acting as lesser officers. Nevertheless, four personal things are important to remember. Marshall had been a Revolutionary soldier, he wrote a five-volume biography of George Washington, he positively hated his first cousin Thomas Jefferson. And his thirty-five-year tenure as the third Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court coincided with some of the dirtiest national politics the nation has ever seen. Marshall's enthronement of Chief Justice control of the federal courts was tolerated because it promoted them both to national power. And when this tough politician had earned the loyalty of both the court system and the legal profession to himself, he transformed the image of the Constitution from a contract between the states into an American Bible for the Rule of Law. Incidentally, he could beat anyone at horseshoes, a game requiring a winner to be both strong and precise. Much of his achievement grows out of three pivotal Supreme Court cases, which today might just as well be regarded as amendments to the Constitution.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the Supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction

|

| Article 3, Section 2.3 |

Marbury v Madison (1803). The first of Marshall's three cornerstone cases involved the Chief Justice himself. After being defeated for reelection to the Presidency in 1800 by Thomas Jefferson, President John Adams hastened to fill up remaining judicial vacancies before Jefferson his successor could be inaugurated, in a maneuver described as "appointing midnight judges". In a sense, Marshall's appointment as Chief Justice had also been in anticipation of the coming eviction of Federalist office holders, so he was himself more or less a midnight judge, destined to become by many years the last Federalist to survive in office. In any event, he was Adams' Secretary of State, soon to be replaced by James Madison, who would then assume the duty to deliver judicial appointment papers to new judges. Marshall was an impassioned Federalist, bitter about the defeat of his party, nursing personal hatred for Jefferson after years of family differences. To say he had a conflict of interest is not only to brush hurriedly by the issue but also to dramatize what loose judicial standards prevailed at the beginning of his three-decade tenure as Chief Justice.

Appointment papers for the midnight judges were completed and lying on the desk of the Secretary of State when the Presidency changed hands from Adams to Jefferson. Had he known what was coming, Secretary of State Marshall would surely have hastened to deliver the papers, but he had not done so. His successor as Secretary of State, James Madison, on the orders from Jefferson, refused to do it, so Marbury sued for a writ of mandamus, or order from a court to deliver the documents. By this time, Marshall was in a new role of presiding over the Supreme Court, fearful to attack Jefferson head on, but nevertheless eager to command the most humiliating obedience from him. Using the technicality (actually, the plain language of the Constitution) that the request was made to the wrong court, mandamus was rejected by Marshall. However, he went on to say in a judicial aside (obiter dictum) that if the right request had come to the U.S. Supreme Court properly , the Court would have approved it. Thus, in one dazzling maneuver at the beginning of his term, Marshall simultaneously asserted the Court's right to review Presidential and Legislative actions, reproved Jefferson for his ignorant conduct, and boxed him into submission by seemingly letting him win a minor case, but one he could be sure would soon have been followed by major ones if the President somehow evaded this decision. Furthermore, he dazzled the legal profession with this tap-dance, guaranteeing their applause by greatly enhancing the status of judges within the Republic, especially compared with the President. And, it should be mentioned, he suppressed public outcry by performing this set of actions in full public view, cloaked within incomprehensible legal garments. The public could see he had done something important, which only lawyers would completely understand. Marshall plainly began his term by demonstrating the full meaning of the rule of law, and his own position astride that law. The main point was that when ordinary judges include offhand commentary in a decision, it might be ignored. But when the Chief Justice of the United States speaking for the majority of his court, makes a legal observation, it would be a brave lawyer indeed who would bring an action in conflict with it. And as for the President and Legislature, Marbury v Madison had also just brushed them aside. It was all done properly, using civil language but deadly logic.

Martin v Hunter's Lessee (1816). This case might be a little more understandable if retitled as "The Heirs of Lord Fairfax v Fairfax County, Virginia". A Virginia law permitting the seizure of Tory property, written decades before the Constitution, asserted its precedence to Federal Law, and therefore its precedence over Federal Law. (To this day, Virginia never quite forgets it was once the largest, richest state, founded nearly two centuries before the Constitution.) Like Marbury v Madison, the case is clouded by Marshall's personal involvement since the Chief Justice had signed a contract with Martin to buy the land himself. This impairment to the case's claim to legal cornerstone status is not entirely annulled by Marshall recusing himself, turning authorship of the opinion over to his faithful disciple Justice Story. Furthermore, the judicial establishment of the principle that an international Treaty (in this case, the Jay Treaty) takes precedence over an Act of Congress is one the nation may still someday come to regret, if movements for "International human rights" and "universal international law" continue to gain popular traction. Such movements are numerous, including international law for the conduct of wars, and the universal Law of the Sea.

The United Nations might now be more of a force if they had not stumbled over the franchise of hundreds of nations, each given an equal vote. To expect the major nations of the Security Council to obey the single-vote mandates of dozens of small African nations is to agree in advance that the UN must be disregarded. Nevertheless, Martin v Hunter's Lessee did eliminate an escape route from Supreme Court domestic domination which might have proved troublesome in Civil War nullification disputes, or in legal cases for which national uniformity is important. On appeal, the Supreme Court finally declared its absolute supremacy over State courts as a general matter, clarifying a number of legal loose threads which had been keeping the precedence issue alive.

McCullough v Maryland 1819) The facts of this case seem considerably simpler than Marshall's long and thundering opinion of them. Indeed, the opinion sounds more like an oration on the meaning of the Constitution, or an enraged obiter dictum , than a terse opinion that the State of Maryland's legislature had passed an unconstitutional law. His remarks are indeed an exposition on the general thrust of the Constitution, foreshadowing many disputes leading up to the Civil War. In effect, it began to make it clear to the slave states that their states-rights viewpoints might conceivably be upheld on a battlefield, but never in a Courtroom. It is thus an opinion which every law student should read several times, and every citizen would profit from reading at least once. At Gettysburg Abraham Lincoln was to restate the principles in concise, even poetic, language. But long before that, Marshall had stood upon a legal mountain, declaiming them in thundering detail.

The Congress shall have power---To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

|

| Article 1, Section 8, clause 18 |

The United States Congress had chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, which then established a Baltimore branch in 1818. There was a national financial panic in 1818, which probably hastened local bank lobbyists to the Maryland Legislature, looking for relief from the unwanted federal competition. Maryland passed a law imposing a fairly high state tax on the operations of the new federal bank. McCullough, the cashier of the federal branch bank, refused to pay the tax. On appeal, McCullough maintained the tax was unconstitutional, and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld him, ordering the opinions of the Maryland courts to be reversed. John Marshall wrote the opinion and took the occasion to set forth his views on constitutionality. Point by point, my point.

What it meant, the old Federalist in a sense intoned, was the states had lost power at the Constitutional Convention and were not going to get it back. The founding fathers and George Washington, in particular, had been uneasy about accusations they had gone beyond their mandate in even calling the Philadelphia Convention. The Articles of Confederation had declared its own provisions to be "perpetual", and the states had previously bound themselves to that. True, the Confederation Congress had authorized a study of how to improve the Articles, but it had never gone so far as to suggest the Philadelphia Convention toss them out.

When the Philadelphia Convention was finishing up its work, Gouverneur Morris had written a preamble beginning with "We the People" in order to assert that its authorization came from the people and not from the governments directly confederated under the Articles, which was true. The ratification process was carefully steered into the language which asked for ratification by the people, acting by states, and from which elected state officers were excluded. The state ratification conventions heard considerable concern about legitimacy voiced by those who probably really disapproved of one feature or another. But overall it was more importantly true that the people at the ratification conventions gradually grew intrigued by the mechanics of self-rule and appreciative of the depth of thought they could see the founders had displayed. By the time the necessary number of states had ratified, public enthusiasm was genuine, while the opposition was squelched into silence or else indirection of speech. Legitimate opposition was acknowledged by specifying that ratification was conditional upon the adoption of a Bill of Rights. Finally, after the new government was subsequently tested by wars and near-wars, pratfalls and triumphs interspersed, the opposition was not only widely judged to have had its say, but its own chance to stumble. After nearly three decades of this, Marshall seems to have decided it was time to lay down the law. All of that is behind us, he said in effect state governments have knuckled under, and the Constitution is indeed triumphant. It was time to snuff out the grumbling and the scheming, and to declare invalid any future attempts at evasion.

The constitutional compromise had confined federal power to a few defined activities and whatever else was proper and necessary within those powers. It did not limit Congress to "absolutely" necessary and "absolutely" proper actions which might heedlessly confine such limited powers to awkward and inefficient behavior. Rather, the Constitution identified areas of power where the two types of government were best suited, expecting them to do their best without hampering each other with turf battles. If Congress decided that banks, or chartered corporations, were desirable means of promoting commerce which had been left unspecified in the Constitution, states could not for that reason alone interfere with federal use of them. States could charter any corporations and banks they pleased, and the federal government could do the same, but only if necessary and proper. There were many other features left unspecified, proper enough for the states to do, but which the federal government might also do -- when necessary and proper to implement its enumerated powers. It was, in short, improper for states to interfere with what was desirable for the national government to do unless the Constitution prohibited it. And the U.S. Supreme Court would be there to decide close cases.

In particular, the states were not to undermine the federal government in the legitimate pursuit of its enumerated powers. Of the strategies available, taxation was particularly vexing, since the difference between a fair tax and a burdensome one can be a matter of opinion. Ultimately, the power to tax is the power to destroy, and it would be better not to have the states taxing the national government in its operations, like issuing currency. The exception might be made for traditional state activities like taxing the bank's real estate. But if the states can tax currency operations, they can set any price, taxing anything if they set about to undermine legitimate Federal activities; such hampering was not contemplated at the Philadelphia Convention, and it will not be tolerated by the courts. Legislatures whose sovereignty ends at their state borders have no right to tax the entire nation which extends beyond those borders. And since state courts must follow state interests and state constitutions, their rulings are subordinate to those of the federal courts, as well.

With the one possible exception of international treaties, all government entities which might challenge the Supreme Court had by now had their noses rubbed in subordination to it. John Marshall went a step further. He even invented a new way to fashion laws which no one at all could challenge: as long as he spoke for the majority, the asides and comments of the Chief Justice in his obiter dicta had become a sort of supreme law.

"They Don't Make That, Anymore"

They Don't Make That, Anymore These words from the nice young lady in the drug store, left me astonished, baffled, bewildered, and angry.

Although I am retired from the practice of medicine, my limited license permits me to prescribe ethical drugs for myself. I had not realized, until that very moment, that to some extent it also isolated me from the experiences of my fellow patients. Let me explain.

The drug involved was tetracycline, which I had surely prescribed a thousand times, and to which I had a sort of loyalty growing out of the fact that I took it myself. In the days when I was a college student, I came down with a form of pneumonia that involved a lot of coughing, like whooping cough. It was then called virus pneumonia because it was somewhat different from ordinary pneumonia, even though it was called Primary Atypical Pneumonia in polite academic circles. Eventually, we learned that its cause was neither a virus nor a bacterium, but rather something in between in size, called Mycoplasma. All of this is important to know, because it tends to appear as a question on a certification examination, but the fact of the matter is, it was a disease for which there was no effective treatment. We could cheer up a little to know that of four hundred recruits at an Alabama training center who came down with it, only one died. On the other hand, Legionnaire's Disease is also caused by a Clamydia and lots of them died, probably because most of them were older. But no matter, in 1944 there was no treatment, and I can tell you it is very unpleasant for a very long time, no matter how young you are.

|

| CAT Scan |

In 1950 I got it again, but this time I was a doctor and knew there was a good treatment. It sounds strange to say so, but I was sort of happy to be able to try out the new medicine, which was then called Aureomycin because the powder was golden yellow. Aureomycin was a trading name, with a patent, and when the patent expired the generic form was called Tetracycline. It worked just fine, and in three or four days I was out of the hospital, perhaps a little weak and shaken, but cured. Incidentally, I discovered an interesting feature of the disease which I believe has not been previously reported. It had long been observed that the chest x-ray showed pneumonia while the stethoscope perceived very little abnormality, a feature which disconcerted those of us who were concerned with the cost of medical care, particularly members of a generation who felt sniffy about the dependence younger physicians displayed for x-rays, and nowadays for CAT scans and MRIs. Unfortunately, in this particular instance, x-rays are clearly superior to stethoscopes.

My third time around for "viral" pneumonia was a few years later; I was sitting on a park bench near the hospital when I recognized the old symptoms were coming back again, so I went straight to the x-ray department and had a chest x-ray less than an hour after the symptoms appeared. I planned to have an x-ray to prove it, go get some tetracycline and be all better over the weekend, with a rollicking anecdote to tell doctor friends about. Unfortunately, the x-ray was normal, so I was admitted into the hospital to see what was wrong. The next morning the x-ray showed a densely consolidated lung, so it had been viral pneumonia all along. And so my old prejudices were vindicated; it was possible to be too quick to order x-rays after all. Unfortunately, the extra twelve hours without treatment allowed me to get a lot sicker than I had to be. I think I know this because, doggone it, I developed the same disease several decades later, took no shortcuts to the drug store, and was fine in a couple of days after I immediately started taking tetracycline. You could say this strange recurrence of Mycoplasma pneumonia over one-lifetime sort of illustrates how medical care of the disease has become progressively cheaper. Instead of a month in the hospital with no treatment, it was now a matter of skipping the stethoscope, skipping the x-ray, skipping the hospital, and just swallowing some cheap tetracycline capsules. You have to have the nerve to do it, of course, and ethically you probably only have a right to do it to yourself, knowing the risks and being willing to accept them. There is, however, one flaw in this story.

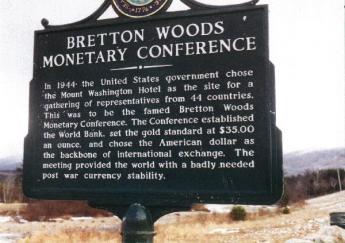

When Aureomycin first emerged from the clutches of the FDA (and well before that accursed Kefauver Amendment), it seemed astonishingly expensive. Because I knew what it weighed (250 milligrams per capsule), and I knew what gold cost ($35 an ounce), it was easy for an idle mind to calculate that Aureomycin cost more than gold. Gold now sells for $1700 per troy ounce, so you could take this story in the direction of inflation. I rather prefer to take it in the direction of nominal dollar amounts, because Aureomycin retailed for $5 a capsule the third time I had the disease, and $1 per capsule when it lost its patent and became tetracycline. The fourth time I had the disease, I bought a container of fifty capsules for 76 cents. But as you have already heard, by the fifth time I couldn't buy it for any price, because everybody had stopped making it. Since my view of the economics of useful commodities is that low prices will only cause shortages if there is artificial market interference, the usual cause of shortages is rationing. Somebody who understands the 2500 pages of Obamacare better than I do will have to tease out the way rationing has caused shortages of tetracycline. And when they are done confusing the public, let them explain why you also can't buy KMnO4 crystals (potassium permanganate), which has cured more cases of athlete's foot for twenty cents, than all those cans of stuff in spray canisters.

Mexican Immigration and NAFTA

|

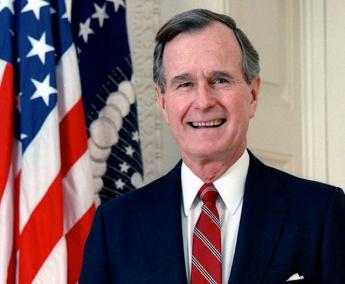

| George H.W. Bush |

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed on December 17, 1992, by President George H. W. Bush for the United States, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney for Canada, and President Carlos Salinas for Mexico. It was intended to eliminate tariffs from the North American continent, with long-run benefits for the three nations who made the agreement. Essentially, it was President Bush's idea, growing out of the long period of public service in which he prepared himself for the Presidency in most of the major components of the American government. After his election, he immediately started to implement the many ideas he had formulated, characteristically worked out in considerable detail, and assigned to government officials he had worked with and knew he could trust. The twin results were that he advanced sophisticated ideas much more quickly than is customary, but then experienced backlash from a public which was accustomed to understanding programs before they assented to them. NAFTA was a prime example of both the advantages and disadvantages of an expedited approach.

Tariffs are a tangled ancient political dispute between nations; George Bush got his two neighbors to sweep them away in a remarkably short time for diplomacy. However, plenty of people benefit from the pork barrel, the unfairness and the economic drag of tariffs, so Bush even got ahead of that opposition, essentially presenting it with a done deal. However, he failed to be re-elected because his fellow Texan Ross Perot campaigned as a third party candidate, thundering about a "giant sucking sound" which was predicted as American businesses would flood into Mexico. Whatever Bill Clinton may think, he won the election as a result of the third-party divisiveness of Ross Perot. And Clinton furthermore got to take credit for NAFTA largely because he claimed the credit. Poppy Bush followed Reagan's strategy of winning by letting others take the credit.

|

| NAFTA |

NAFTA had a lot of minor provisions, but the main feature was to help Mexico with manufactures, compensating for America hurting Mexican agriculture with cheaper United States agricultural imports. The usual suspects howled about the unfairness of such a dastardly deed, but they lost. Helping Mexican manufactures took the tangible form of the "maquiladoras", which were assembly plants from the United States re-located just south of the border, assembling parts made abroad into machinery and other final products, for sale in the United States. The general idea behind this was that Mexican immigration was mostly driven by a hunger for better jobs; give them jobs in Mexico, and they would stay home. That's a whole lot better than an endless border war. Even today, it would be hard to find anyone who would contend that fences, searchlights and police dogs were a superior way to control the borders.

For a while, the maquiladoras were a huge success. But then, China got into the act, paying wages so low that even Mexicans could not live on them. No doubt Ross Perot rejoices that the maquiladoras promptly collapsed, leaving abandoned hulks of factories just across the dried-up Rio Grande. And eventually, we even have tunnels bored under the border and more illegal Mexicans in America than we have people in prison who might take the same jobs. Not the least of the consequences came from the other parts of the same country. Mexico traded an injured agricultural economy for the promise of high-paid manufacturing jobs in maquiladoras. So, masses of impoverished Mexican farmers were made available for illegal immigration, up North.

It is now anybody's guess whether Chinese wages will rise enough, soon enough, to reverse the economics of their destruction of the Mexican economy. The election of a union-dominated Clinton/Obama presidency in the meantime does not bode well for actions which would reverse that result, which now would threaten American-Chinese relations of an entirely different sort. It is true that Chinese wages are relentlessly rising, and that transportation costs now favor assembly-factories closer to the American consumer. But maybe the moment for this approach is passing, or possibly has passed.

REFERENCES

| George H. W. Bush: The American Presidents Series: The 41st President, 1989-1993: Timothy Naftali, ISBN-10: 0805069666 | Amazon |

More, or Fewer, Raisins in the Pudding

|

| manuscripts |

Some book publishers do indeed regard history as handfuls of paper in a manuscript package, mostly requiring rearrangement in order to be called a book. Librarians are more likely to see historical literature dividing into three layers of fact mingled with varying degrees of interpretation: starting with primary sources, which are documents allegedly describing pure facts. Scholars come into the library to pore over such documents and comment on them, usually to write scholarly books with commentary, called secondary sources . Unfortunately, many publishers reject anything which cannot be copyrighted or is otherwise unlikely to sell very well, however important historians say it may be. Authors of history who make a living on it tend to focus on the general reading public, generating tertiary sources, sometimes textbooks, sometimes "popularized" history in rising levels of distinction. Sometimes these authors go back to original sources, but much of their product is based on secondary sources, which are now much more reliable because of the influence of a German professor named Leopold von Ranke. Taken together, you have what it is traditional to say are the three levels of historical writings.

|

| Leopold von Ranke |

Leopold von Ranke formalized the system of documented (and footnoted) history about 1870, vastly improving the quality of history in circulation by insisting that nothing could be accepted as true unless based on primary documents. Von Ranke did in fact transform Nineteenth-century history from opinionated propaganda in which it had largely declined, into a renewed science. At its best, it aspired to return to Thucydides, with footnotes. That is, clear powerful writing, ultimately based on the observations of those who were actually present at the time. Unfortunately, Ranke also encased historians in a priesthood, worshipping piles of documents largely inaccessible to the public, often discouraging anyone without a PhD. from hazarding an opinion. The extra cost of printing twenty or thirty pages of bibliography per book is now a cost which modern publishing can ill afford, making modern scholarship a heavier task for the average graduate student because the depth of scholarship tends to be measured by the number of citations, but incidentally "turning off" the public about history. All that seems quite unnecessary since primary source links could be provided independently (and to everyone) on the Internet at negligible cost. And supplied not merely to the scholar, but to any interested reader, no need to labor through citations to get at documents in a locked archive.

|

| E-Books |

The general history reader remains content with tertiary overviews, and a few brilliant secondary ones because document fragility bars public access to primary papers, but many might enjoy reading primary sources if they were physically more available. The general reader also needs impartial lists of "suggested reading", instead of the "garlands of bids", as one wit describes the bibliographies employed by scholars. If you glance through the annual reports of the Right Angle Club, you will see I have increasingly included separate internet links to both secondary as well as primary sources, because the bibliographies within the secondaries lead back to the primaries. Unfortunately, you must fire up a computer to access these treasures. The day soon approaches when scholars can carry a portable computer with two screens, one displaying the historian's commentary while the second screen displays related source documents. It seems likely history on paper will persist while that remains cheaper, but also because e-books make it hard to jump around. Newspapers and magazines particularly encounter this obstacle, because publication deadlines give them less time for artful re-arrangement. E-books are sweeping the field in books of fiction because fiction is linear. Non-fiction wanders around, even though this subtlety is often unappreciated by computer designers.

Museum of the American Revolution

The Right Angle Club of Philadelphia was recently pleased to be visited by Michael C. Quinn, the President, and CEO of the forthcoming Museum of the American Revolution, which will be built at Third and Chestnut Streets, on the site of the former Visitors Center. Mr. Quinn comes to us from the Mt. Vernon and James Madison Museums in Virginia and expects to spend another three years getting the new Museum built and established. It's also expected to cost about $150 million, so look for something really special. The great majority of the required money is expected to come from Philadelphia and surrounding territory, led by a challenge grant from Gerry Lendfest of $40 million.

The collection of Valley Forge and related Revolutionary artifacts was begun by Herbert Burk, an Episcopal rector in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and the son of another Episcopal rector of Clarksboro, New Jersey, and who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania toward the end of the Nineteenth century. The Valley Forge area was pretty well deserted at that time, and the local bishop expressed doubt that it could support both an Episcopal and a Baptist church, particularly since an earlier rector named Guthrie had attempted it and finally disappeared. Reverend Burk, however, was fired with the vision of Washington kneeling in the snow, and highly scornful of doubters who insisted on seeing his footprints in the snow before they would accept it. These were the days just after the German historian Leopold von Ranke had started a movement of great enthusiasm among historians for documents to prove almost anything calling itself history, so there was more than the usual amount of harumphing among academics about authenticity, which Burk dismissed with scorn. Since his second wife was a Stroud, there may have been social issues as well. About all, we really know of George Washington's religious beliefs was that he regularly went to Christ Church and sat in Martha Washington's pew; but he resolutely refused to take Communion. It sounds to some of us as though he was more of a politician than a theologian. But the Museum now has picked up successor enthusiasts, determined to make the Museum a success; so let's let that religion matter drop.

|

| Museum of the American Revolution |

The old visitors center was given a bell by Queen Elizabeth II, who brought it over on the royal yacht and gave a memorable speech at its installation. The deed to the property does not include the bell, and its future is presently uncertain. However, the building will be torn down and replaced by a much larger structure, intended to house many rooms and a tour lasting hours, to show off Washington's military tent and similar artifacts of the low point of the Revolution, when it rested with the personal character of a few founding fathers, to preserve the drive and idealism of the freezing, starving troops. It's a tall challenge for Mike Quinn to carry it off with the right mixture of showmanship and concern for accuracy. After all, no good story is improved by exaggeration.

Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold: Fallen Idols

|

| General Burgoyne |

After defeating Washington's troops at the battle of Germantown, the British then occupied Philadelphia for the better part of a year. The town was a mess, with food shortages typical of the squalor of any occupying army equalling the existing population. Washington was forced to fall back to the natural fortress of Valley Forge. The city of Philadelphia was not exactly under siege, but it was as difficult a place for British troops to live as a besieged city. For his part, Washington was forced to shiver and starve in the nearby mountain valley, at least consoled by distant news of American achievements. General Burgoyne and his army were soon captured at Saratoga by General Gates under humiliating circumstances. Clearly, the dashing hero of this event had been Benedict Arnold on a white horse leading the charge, getting wounded in the leg in the process.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in Paris |

Benjamin Franklin in Paris trumpeted the news of this victory, reminding the French of Washington's earlier victory at Trenton, and maneuvering it all into a treaty of alliance. With the French fleet in the nearby Caribbean, Philadelphia was no longer a safe place for the British to stay a hundred miles upriver, and the idea of abandoning occupied Philadelphia began to grow. Having gambled on British victory in defiance of London's orders, the Howe brothers were not in a position to argue with new orders. The British soldiers inside the city were more comfortably housed than the American troops outside it, but nobody was exactly comfortable. The American Congress had, of course, fled to the hinterlands. All in all, it suddenly became uncertain who was going to win this war.

|

| Peggy Shippen |

The American population at this time has been described as a one-third rebel, one-third Tory, and one-third trying to hunker down to see who would win. Many of the seriously committed Tories had fled from Philadelphia when the rebels took charge, while pacifist Quakers were a little hard to classify. Generally speaking, the prosperous merchant class had never been persuaded King George was all that bad, while the less prosperous artisans were the fervent patriots. Under such conditions, many people who privately leaned in either direction found it was best to seem non-committal. The British were billeted in private homes; the Officers in the best houses of the merchant class, the common soldiers generally housed in the homes of the artisans. Although the soldiers and the artisans did not mix very well, circumstances permitted the aristocratic officers getting on pretty well with the merchants whose houses they occupied. The girls in the colonial families seemed immediately attractive to the British officers, who were far from home, while the officers also seemed pretty glamorous to the girls. So, it is not exactly surprising that the most beautiful colonial belles like Peggy Shippen and Peggy Chew found themselves frequently in company with dashing officers like Major John Andre. Andre would likely have been a heartthrob in any circumstance since he had risen to the rank of adjutant-general at a young age, wrote poetry and plays, reputedly was rich, and was regularly the life of any party. Nor is it surprising that generations of Peggy's descendants have treasured a lock of his hair.

|

| Margaret Oswald Chew Howard |

When the decision was finally made to abandon Philadelphia, six of the British officers personally contributed twenty-five thousand dollars to throwing Philadelphia's most famous, most splendiferous party, called The Machianza. It went on for days, had real jousting matches between officers dressed like knights in armor, banquets and all that sort of thing. It was Andre's idea, and he was enthusiastically in charge. Surviving records of the event do not show that Peggy Shippen was present, but in view of what happened later, much of her correspondence has been destroyed. It's pretty hard to imagine she wasn't there.

|

| Major General Benedict Arnold |

The British then marched away, and Washington's troops cautiously followed, assuming control of the city. Major General Benedict Arnold had been sent from Saratoga to Valley Forge to recover from his leg wound, and probably also to raise morale among the troops celebrating the now-famous hero. Washington more or less immediately decided to pursue the British across New Jersey, thus leading to the battle of Monmouth as the two armies raced for the Naval vessels in lower New York harbor. Since General Arnold had not fully recovered from his wounds, he was installed as the military governor of a somewhat bedraggled Philadelphia. Naturally, he was the center of the social scene, and soon was pursuing Peggy Shippen in every way he knew, which included some pretty gloppy letters in Romantic style. Peggy's father was uneasy about his intentions but was eventually mollified by Arnold's purchase of the house called Mount Pleasant, now a tourist attraction in Fairmount Park. With this evidence that his prospective son in law was at least likely to stay in Philadelphia, Edward Shippen finally repented of his opposition to the marriage of his daughter. But the new couple were soon off to West Point, where Arnold had kept up a persuasion campaign with George Washington, to get himself appointed the commandant of the main northern defense of the Hudson River. A point for Philadelphian tour guides to remember is that Peggy and Benedict never got a chance to live in Mount Pleasant.

Arnold originally lived in New Haven, Connecticut, where he had established quite a sea-faring reputation as a merchant, some would say privateer, others would say buccaneer. There is no doubt he was aggressive, and combative, and considered himself a little bit above the law. These qualities made him outstanding at Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga, and are always more highly valued in young men in a war. Unfortunately, he made a bitter enemy of Joseph Read who was briefly his neighbor, and later was President of the Continental Congress. Read accused Arnold of smuggling and trading with the enemy, and was so determined about it that Arnold was scheduled for court-martial, but postponed. Arnold was loudly defensive about the whole matter, and public sympathy was on his side. In view of what soon happened, he might well have been cleared by the court, but likely there was some truth to the accusations. Using Peggy as a go-between, he entered into a correspondence with Andre (then the adjutant-general in New York) offering to deliver the surrender of West Point, three thousand prisoners, and possibly George Washington himself in return for what might today be half a million dollars. As a note of realism, he was willing to accept half that in the event of failure. The British were particularly anxious to acquire American prisoners to exchange for their own troops captured at Saratoga. Unless Arnold was a total sociopath, he must have thought he had quite a grievance.

|

| Lord Cornwallis |

Things went along surprisingly well at first, with negotiations for price back and forth, plans for attacking West Point moving along with the Navy, and Andre disguising himself for a visit to Arnold in his house to the south of the Fort on West Point. Much of the success was due to the movie-star reputation of Benedict Arnold; few could imagine such a hero doing such an unheard-of thing. However, the plot was discovered while Washington was away visiting the Fort, and Arnold hastily abandoned his family and fled to a waiting British warship. Andre decided to make his way south to the ship through rebel territory, but local soldiers and farmers were much more suspicious than others had been, and after penetrating his disguise, found incriminating papers concealed in his boots. Since he was out of uniform behind enemy lines, Andre was by definition a spy, which required hanging. He made a plea to be shot like a gentleman, but Washington with tears allegedly in his eyes refused. With much bravado, Andre jumped atop his own casket and placed the noose around his own neck, a behavior much admired by his compatriots when they heard of it

Meanwhile, Peggy had put on a crazy-woman act which apparently convinced Washington to be lenient, and allow her to rejoin her husband. The couple stayed in New York for a few months, toying with commands of loyalist troops in the south, but eventually taking ship for England. Lord Cornwallis was on the same ship and they became pals as shipmates, pleasing Arnold quite a lot. Unfortunately, British society was only stiffly polite to them, and many did not trouble to conceal their disdain for traitors to any cause, and thus life in England was not smooth. By that time, it is possible that many had begun to suspect the whole idea of treason was Peggy's idea from the start, as is today the conventional view of it. As an American aristocrat, she was uncomfortable with the rebels in Philadelphia, and as the impetuous wife of an accused smuggler, it was difficult to fit in with either the Quakers or the merchants with loyalist leanings. No doubt she heard some catty whisperings among her friends and relatives about her other romantic associations. The British paid them their promised pensions, but a career in the British Army was out of the question for her husband. But the real shock would come, from discovering the British as a whole didn't much care for their behavior, either.

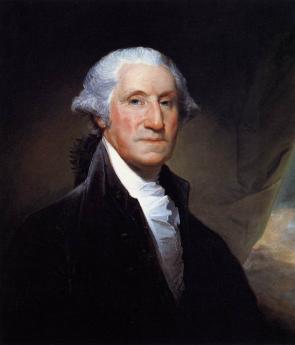

Implicit Powers of the Federal Government

<The two highest achievements of James Madison, had been and still remain, the writing of the Bill of Rights, and acting as a close collaborator with George Washington in fleshing out the role of the President in the new government. The Ninth and Tenth Amendments made it clear that the federal government was to be constrained to a limited and enumerated set of powers, while all other activities belonged to the states. This was already clear enough in the main text of the Constitution, which Madison also dominated after close consultation with Washington before the Constitutional Convention. So he had battled and successfully negotiated one matter twice, before the most powerful and distinguished assemblies in the nation. As to the second matter, circumstances had promoted a shy young bookworm into the role of preceptor to the most famous man in America. In the earliest days of the new republic, certainly during the first year of it, Washington and Madison worked closely together in defining the role of the Presidency.

|

| George Washington |

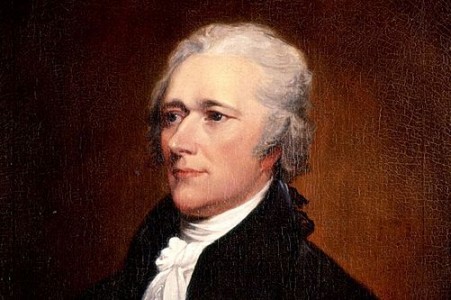

During the first weeks of that exploratory period, Washington induced Congress to create a cabinet and the first four cabinet positions, even though the Constitution did not mention cabinets. It all was explained as an "implicit power", inherently necessary for the functioning of the Executive branch. Soon afterward, Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury proposed the creation of a national bank. Madison and his lifelong friend Thomas Jefferson were bitterly opposed, using the argument that creating banks was not one of the enumerated powers granted by the Constitution. Hamilton's reply was that creating a bank was an "implicit power" since it was necessary for running the federal government. Of course, Hamilton and Jefferson both had other unspoken motives for their position: for and against promoting urban vs. rural power, for and against the industrialization of the national economy, and dominating the states in matters of currency and financial leadership. It empowered a national rather than a confederated economy.

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

For Madison, the legalism probably carried considerably more weight than it did for Jefferson and Hamilton because it demonstrated the enduring consequences of being vague about the boundaries of any constitutional restriction. If this loophole got firmly established, it might reduce the whole federal system to a laughingstock. In order to promote the "general welfare", anything at all could be called an implicit power, and both separation of powers and enumerating federal powers would soon become quaint flourishes. The whole Constitution might fall apart in endless debates. On a personal level, Madison's highest achievements would have to be supplanted by something more practical. Besides which, Madison was a Virginian, a rich slave-holding farmer, and a young politician, seemingly on the verge of a promising career which might easily lead to the presidency for himself. Hamilton his most visible opponent, was already proposing a tax on whiskey which would almost surely antagonize farmers to the west, and assuming the Revolutionary debts of the states was equally divisive.

|

| Mt. Vernon |

As matters eventually worked out, the main disputants made ostensible constitutional arguments, while the real political dispute would be settled by a political deal struck at a dinner. It traded relocation of the national capital to Virginia, for the assumption of the debts of all states (when Virginia had already paid off its debt.) Location of the capitol opposite George Washington's home at Mt. Vernon also took care of difficulties coming from that direction. By the time the uproar about this arrangement subsided, the precedent for settling the inherent conflict between enforcing Constitutional limitations versus enlarging their boundaries had been set. The most opportune time for stricter interpretation was fading while the most likely advocates of it were restrained by their own example. The negotiation was a little unseemly, and probably encouraged similar decisions to migrate to a less conflicted body, which eventually John Marshall would define as the U.S. Supreme Court.

National Debt, Presidential Hat Tricks, Shale Gas and Argentina

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

This-here speaker at the Right Angle Club began a discussion of the "Fiscal Cliff" razzle-dazzle of 2012, by changing his mind about the causes of the financial crash of 2007. Originally, it seemed as though globalizing 500 million Chinese out of poverty had destabilized the exuberant American mortgage market by flooding it with cheap credit. Supplanting that idea, or perhaps only supplementing it, must now be added the overextension of national debt itself to a point of bringing national borrowing to a halt.

Early in the Eighteenth century the Dutch and English had monetized national assets through a system of national borrowing formalized by Necker in Europe, and Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton in America. Aside from a handful, no one could understand what they were talking about. Try reading that sentence a second time.

It amounted to guaranteeing all the private credit in the banking, investment, and commerce systems, with a national debt (in the form of Treasury bonds) which monetized all the assets of the whole nation. That action more or less doubled their value, just as any bank loan is seemingly owned by two people at the same time. Carried to an extreme, it might imply that America could turn Guam and Hawaii over to China if we defaulted on our debt. That was never actually intended to happen, and it never has, because all nations now fear the deflation which could result from triggering a massive exchange of national assets. The nebulous issue of "National Sovereignty" interferes with territorial transfers by any means other than war. If one nation defaults against a second nation which is afraid to go to war, it is just the stronger nation's hard luck about the debts it has chosen to support unless a transfer of assets actually happens. The Treaty of Versailles did transfer assets to the victors, and set off World War II, although it is considered bad manners to mention it. That's a simplified view of our international financial system, which admittedly skirts uncertainty about how much national debt is too much.

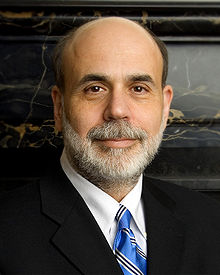

In fact, no one knows how much is too much until everyone runs for the exits. Now that politicians have control of computers and "big data", a modern description places the blame on Alan Greenspan the former Chairman of the Federal Reserve. For eighteen years Greenspan produced delicious world prosperity by steadily increasing American national debt faster than the American economy was growing. Sooner or later this approach was going to uncover how much was currently too much Federal debt. With silver and gold removed from the equation, one could see that default would certainly loom whenever the size of the debt became so large it could never be serviced by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and possibly sooner than that, if enough people could guess what was coming. This reality might be obscured temporarily by reducing interest rates, modifying international trade balances, and inflation. When the stars were in alignment however, the system just had to collapse and start over. Because it happened gradually, perhaps it would unwind gradually. In 2007 what happened was that everybody tried to get out the door at the same time. Essentially, our two political parties made opposite assessments: the party of Hamilton -- Republicans -- announced this system was doomed, while Democrats --the party of Andrew Jackson -- announced they could stave off disaster by making the rich Republicans pay for it. Both parties were partly right but essentially wrong, and the Democrats hired a better magician.

|

| Henry Clay |

It will take months or even years to be certain just what strategy was pursued. It would appear the Democrats chose to repeat the performance of the Obamacare legislation, eliminating national debate by eliminating the Congressional committee system of examining details in advance of a vote. Given one day to digest two thousand pages prepared by the Executive branch, no time was allowed for public opinion to form about Obamacare. In the case of the fiscal cliff episode, Congress was given less than one day to consider 150 pages allegedly prepared the day prior to the vote. Some will admire the skill of the executive branch in orchestrating this secret maneuver, but eventually, it must become apparent that policy decisions have been transferred from the legislative to the executive branch of government. Perhaps the Congressional Republicans are as stupid as the Democrats portray them to be, but it is also possible that a decision has been made to tempt the Democratic leaders into repeating this performance several times until eventually, the public is ready to consider impeachment for it. No matter what the strategy, we are now threatened with imagining some moment when gun barrels come level and live rounds slide home. We may pass up the opportunity to criticize Henry Clay for concentrating undue power in the Speaker of the House, or to uncover the way Harry Reid was persuaded to surrender Senate power to the Executive; both miscalculations are fast becoming irrelevant in the flurry of events. We came close to borrowing too much, exceeding our means to pay it back, that's all. A New York Times editorial economist feels we can "grow" our way out of this flirtation with danger, and we all certainly hope so.

Seemingly, there are only two ways to cope with over-borrowing, once we step over the invisible line. A nation may cheat its citizens with inflation, or it may cheat foreign citizens by defaulting on their currency. We are indebted to Rogoff and Reinhart for pointing out there is no difference between inflation and default except the identity of the cheated creditor; so most politicians prefer to cheat foreigners. Either way, cheating makes deadly enemies. Two centuries ago, Alexander Hamilton suggested a third way out of the problem, which we would today call "growth". But here, cheating is pretty easy: If the limit is some ratio of debt to GDP, find a way to increase nominal GDP.

|

| Shale Gas and Argentina |