Related Topics

Government Organization

Government Organization

Unwritten Constitutional Modification

It is so difficult to amend the Constitution, we mostly don't do it. Our system is to have the Supreme Court migrate slowly through several small adjustments, watching the country respond. Occasionally we have imported new principles, sometimes not entirely wise ones, adopted without the same seasoning.

..Constitution and Court

Forget all those lawyer jokes you hear. The American legal profession can rightly be proud of the Federal Court System, an achievement of the whole profession. America may be legalistic and overlawyered, but that reflects the rule of law dominated by lawyers. Curiously, the leader of this creation, John Marshall, was not so much a legal theoretician as a relentless Federalist lawyer, determined to reshape the legal profession to be worthy of power.

Right Angle Club: 2013

Reflections about the 91st year of the Club's existence. Delivered for the annual President's dinner at The Philadelphia Club, January 17, 2014.

George Ross Fisher, scribe.

John Marshall Decides Three Cases

|

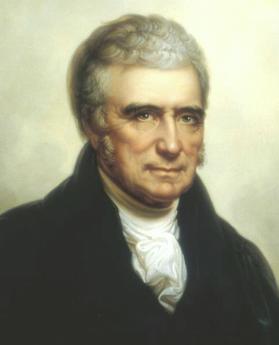

| Chief Justice John Marshall |

John Marshall, taking sixteen years to do it, transformed the Constitution internally into the cornerstone of the Rule of Law, making the legal profession its guardian. Nine respected justices now essentially hold lifetime appointments as bodyguards of the structure Marshall designed, with all lawyers acting as lesser officers. Nevertheless, four personal things are important to remember. Marshall had been a Revolutionary soldier, he wrote a five-volume biography of George Washington, he positively hated his first cousin Thomas Jefferson. And his thirty-five-year tenure as the third Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court coincided with some of the dirtiest national politics the nation has ever seen. Marshall's enthronement of Chief Justice control of the federal courts was tolerated because it promoted them both to national power. And when this tough politician had earned the loyalty of both the court system and the legal profession to himself, he transformed the image of the Constitution from a contract between the states into an American Bible for the Rule of Law. Incidentally, he could beat anyone at horseshoes, a game requiring a winner to be both strong and precise. Much of his achievement grows out of three pivotal Supreme Court cases, which today might just as well be regarded as amendments to the Constitution.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the Supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction

|

| Article 3, Section 2.3 |

Marbury v Madison (1803). The first of Marshall's three cornerstone cases involved the Chief Justice himself. After being defeated for reelection to the Presidency in 1800 by Thomas Jefferson, President John Adams hastened to fill up remaining judicial vacancies before Jefferson his successor could be inaugurated, in a maneuver described as "appointing midnight judges". In a sense, Marshall's appointment as Chief Justice had also been in anticipation of the coming eviction of Federalist office holders, so he was himself more or less a midnight judge, destined to become by many years the last Federalist to survive in office. In any event, he was Adams' Secretary of State, soon to be replaced by James Madison, who would then assume the duty to deliver judicial appointment papers to new judges. Marshall was an impassioned Federalist, bitter about the defeat of his party, nursing personal hatred for Jefferson after years of family differences. To say he had a conflict of interest is not only to brush hurriedly by the issue but also to dramatize what loose judicial standards prevailed at the beginning of his three-decade tenure as Chief Justice.

Appointment papers for the midnight judges were completed and lying on the desk of the Secretary of State when the Presidency changed hands from Adams to Jefferson. Had he known what was coming, Secretary of State Marshall would surely have hastened to deliver the papers, but he had not done so. His successor as Secretary of State, James Madison, on the orders from Jefferson, refused to do it, so Marbury sued for a writ of mandamus, or order from a court to deliver the documents. By this time, Marshall was in a new role of presiding over the Supreme Court, fearful to attack Jefferson head on, but nevertheless eager to command the most humiliating obedience from him. Using the technicality (actually, the plain language of the Constitution) that the request was made to the wrong court, mandamus was rejected by Marshall. However, he went on to say in a judicial aside (obiter dictum) that if the right request had come to the U.S. Supreme Court properly , the Court would have approved it. Thus, in one dazzling maneuver at the beginning of his term, Marshall simultaneously asserted the Court's right to review Presidential and Legislative actions, reproved Jefferson for his ignorant conduct, and boxed him into submission by seemingly letting him win a minor case, but one he could be sure would soon have been followed by major ones if the President somehow evaded this decision. Furthermore, he dazzled the legal profession with this tap-dance, guaranteeing their applause by greatly enhancing the status of judges within the Republic, especially compared with the President. And, it should be mentioned, he suppressed public outcry by performing this set of actions in full public view, cloaked within incomprehensible legal garments. The public could see he had done something important, which only lawyers would completely understand. Marshall plainly began his term by demonstrating the full meaning of the rule of law, and his own position astride that law. The main point was that when ordinary judges include offhand commentary in a decision, it might be ignored. But when the Chief Justice of the United States speaking for the majority of his court, makes a legal observation, it would be a brave lawyer indeed who would bring an action in conflict with it. And as for the President and Legislature, Marbury v Madison had also just brushed them aside. It was all done properly, using civil language but deadly logic.

Martin v Hunter's Lessee (1816). This case might be a little more understandable if retitled as "The Heirs of Lord Fairfax v Fairfax County, Virginia". A Virginia law permitting the seizure of Tory property, written decades before the Constitution, asserted its precedence to Federal Law, and therefore its precedence over Federal Law. (To this day, Virginia never quite forgets it was once the largest, richest state, founded nearly two centuries before the Constitution.) Like Marbury v Madison, the case is clouded by Marshall's personal involvement since the Chief Justice had signed a contract with Martin to buy the land himself. This impairment to the case's claim to legal cornerstone status is not entirely annulled by Marshall recusing himself, turning authorship of the opinion over to his faithful disciple Justice Story. Furthermore, the judicial establishment of the principle that an international Treaty (in this case, the Jay Treaty) takes precedence over an Act of Congress is one the nation may still someday come to regret, if movements for "International human rights" and "universal international law" continue to gain popular traction. Such movements are numerous, including international law for the conduct of wars, and the universal Law of the Sea.

The United Nations might now be more of a force if they had not stumbled over the franchise of hundreds of nations, each given an equal vote. To expect the major nations of the Security Council to obey the single-vote mandates of dozens of small African nations is to agree in advance that the UN must be disregarded. Nevertheless, Martin v Hunter's Lessee did eliminate an escape route from Supreme Court domestic domination which might have proved troublesome in Civil War nullification disputes, or in legal cases for which national uniformity is important. On appeal, the Supreme Court finally declared its absolute supremacy over State courts as a general matter, clarifying a number of legal loose threads which had been keeping the precedence issue alive.

McCullough v Maryland 1819) The facts of this case seem considerably simpler than Marshall's long and thundering opinion of them. Indeed, the opinion sounds more like an oration on the meaning of the Constitution, or an enraged obiter dictum , than a terse opinion that the State of Maryland's legislature had passed an unconstitutional law. His remarks are indeed an exposition on the general thrust of the Constitution, foreshadowing many disputes leading up to the Civil War. In effect, it began to make it clear to the slave states that their states-rights viewpoints might conceivably be upheld on a battlefield, but never in a Courtroom. It is thus an opinion which every law student should read several times, and every citizen would profit from reading at least once. At Gettysburg Abraham Lincoln was to restate the principles in concise, even poetic, language. But long before that, Marshall had stood upon a legal mountain, declaiming them in thundering detail.

The Congress shall have power---To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

|

| Article 1, Section 8, clause 18 |

The United States Congress had chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, which then established a Baltimore branch in 1818. There was a national financial panic in 1818, which probably hastened local bank lobbyists to the Maryland Legislature, looking for relief from the unwanted federal competition. Maryland passed a law imposing a fairly high state tax on the operations of the new federal bank. McCullough, the cashier of the federal branch bank, refused to pay the tax. On appeal, McCullough maintained the tax was unconstitutional, and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld him, ordering the opinions of the Maryland courts to be reversed. John Marshall wrote the opinion and took the occasion to set forth his views on constitutionality. Point by point, my point.

What it meant, the old Federalist in a sense intoned, was the states had lost power at the Constitutional Convention and were not going to get it back. The founding fathers and George Washington, in particular, had been uneasy about accusations they had gone beyond their mandate in even calling the Philadelphia Convention. The Articles of Confederation had declared its own provisions to be "perpetual", and the states had previously bound themselves to that. True, the Confederation Congress had authorized a study of how to improve the Articles, but it had never gone so far as to suggest the Philadelphia Convention toss them out.

When the Philadelphia Convention was finishing up its work, Gouverneur Morris had written a preamble beginning with "We the People" in order to assert that its authorization came from the people and not from the governments directly confederated under the Articles, which was true. The ratification process was carefully steered into the language which asked for ratification by the people, acting by states, and from which elected state officers were excluded. The state ratification conventions heard considerable concern about legitimacy voiced by those who probably really disapproved of one feature or another. But overall it was more importantly true that the people at the ratification conventions gradually grew intrigued by the mechanics of self-rule and appreciative of the depth of thought they could see the founders had displayed. By the time the necessary number of states had ratified, public enthusiasm was genuine, while the opposition was squelched into silence or else indirection of speech. Legitimate opposition was acknowledged by specifying that ratification was conditional upon the adoption of a Bill of Rights. Finally, after the new government was subsequently tested by wars and near-wars, pratfalls and triumphs interspersed, the opposition was not only widely judged to have had its say, but its own chance to stumble. After nearly three decades of this, Marshall seems to have decided it was time to lay down the law. All of that is behind us, he said in effect state governments have knuckled under, and the Constitution is indeed triumphant. It was time to snuff out the grumbling and the scheming, and to declare invalid any future attempts at evasion.

The constitutional compromise had confined federal power to a few defined activities and whatever else was proper and necessary within those powers. It did not limit Congress to "absolutely" necessary and "absolutely" proper actions which might heedlessly confine such limited powers to awkward and inefficient behavior. Rather, the Constitution identified areas of power where the two types of government were best suited, expecting them to do their best without hampering each other with turf battles. If Congress decided that banks, or chartered corporations, were desirable means of promoting commerce which had been left unspecified in the Constitution, states could not for that reason alone interfere with federal use of them. States could charter any corporations and banks they pleased, and the federal government could do the same, but only if necessary and proper. There were many other features left unspecified, proper enough for the states to do, but which the federal government might also do -- when necessary and proper to implement its enumerated powers. It was, in short, improper for states to interfere with what was desirable for the national government to do unless the Constitution prohibited it. And the U.S. Supreme Court would be there to decide close cases.

In particular, the states were not to undermine the federal government in the legitimate pursuit of its enumerated powers. Of the strategies available, taxation was particularly vexing, since the difference between a fair tax and a burdensome one can be a matter of opinion. Ultimately, the power to tax is the power to destroy, and it would be better not to have the states taxing the national government in its operations, like issuing currency. The exception might be made for traditional state activities like taxing the bank's real estate. But if the states can tax currency operations, they can set any price, taxing anything if they set about to undermine legitimate Federal activities; such hampering was not contemplated at the Philadelphia Convention, and it will not be tolerated by the courts. Legislatures whose sovereignty ends at their state borders have no right to tax the entire nation which extends beyond those borders. And since state courts must follow state interests and state constitutions, their rulings are subordinate to those of the federal courts, as well.

With the one possible exception of international treaties, all government entities which might challenge the Supreme Court had by now had their noses rubbed in subordination to it. John Marshall went a step further. He even invented a new way to fashion laws which no one at all could challenge: as long as he spoke for the majority, the asides and comments of the Chief Justice in his obiter dicta had become a sort of supreme law.

Originally published: Tuesday, February 19, 2013; most-recently modified: Sunday, July 21, 2019