3 Volumes

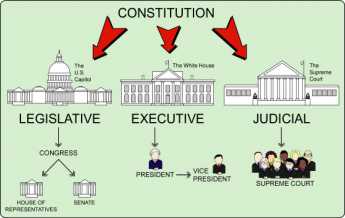

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

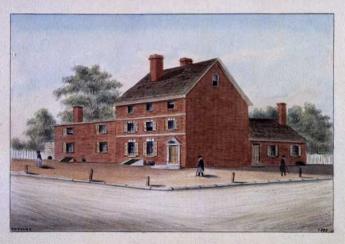

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Legal Philadelphia (1)

.

Robert Barclay Justifies Quaker Meetings

|

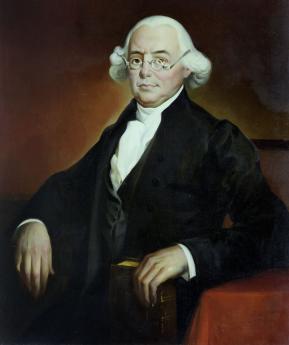

| Robert Barclay |

As part of the dissidence and Civil War of 17th Century England, Robert Barclay the Scotsman emerged with a point of view which was structured and reasoned in detail. What was almost unique was his reduction of it to a handful of pithy "Sound Bites". Coupled with membership in a prominent family, these abilities made him a particular friend of James, Duke of York, later King. Barclay became a Quaker at an early age.

The whole point of the Reformation was revulsion against the corrupt Catholic clergy, shielded behind some impossibly convoluted legalisms of doctrine. But for the governing establishment, any reform was going too far if it led to anarchy and chaos; combating disorder was then in many ways the central mission of the Catholic faith. The establishment did recognize that public revolt against universal micromanagement led to the scaffold for Kings who insisted on it. But in their view, the need for law and order still demanded some legitimacy, if not organized law. The Rangers, who paraded about stark naked and lived in ways resembling the hippies of the 1960s, were beyond the pale. Quakers, who professed no formal doctrine except silent meditation, might be possible just as threatening. After all, silent meditation could lead you anywhere including regicide. But the Quakers at least were quiet about it.

George Fox the founder of Quakerism had already provided one basis for containing fears of anarchy, by organizing local monthly meetings for worship within regional quarterly meetings; quarterly meetings, in turn, were within an overall framework of a yearly meeting. Occasional monthly meetings might develop a consensus for wild and antisocial behavior, indeed often did so, but would have to persuade the quarterly meetings whose members naturally outnumbered them. In extreme cases, the whole religion assembled in a yearly meeting. The innate conservatism of the meek would usually silence the extremism of the rebellious few. Very few kings would deny they could go no further toward despotism themselves, without the public behind them. The Quaker problem was to demonstrate what their consensus really was.

|

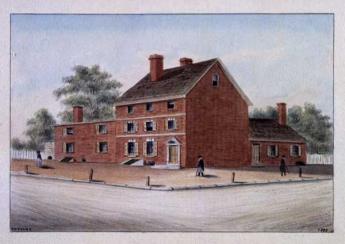

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

Essentially, the answer emerged that any religion which renounced a priesthood, which even renounced having a written doctrine, still needed some sort of institutional memory. If every Quaker began with a clean slate, to develop his own organized set of moral principles, then most of them would never get very far. Even if they did, they would have no time left for milking cows and weaving cloth. Single silent meditation was inefficient, particularly if you had faith that everyone was eventually going to arrive at the same convictions as the Sermon on the Mount. The founders of Quakerism took a chance, here. To assume the same outcome, you have to assume everyone starts with the same instincts and talents; even 21st Century America has private doubts about that one. Feudal England would have rejected it contemptuously. Carried to an extreme, it was a claim that everyone was as good a philosopher as Jesus of Nazareth, as good a person, as much a Son of God. That seemed like an arrogant claim. A more humble claim was that collectively, listening respectfully to one another in a gathered meeting, the whole world would over time reach the same truths as the Creator. If not, that still was as about as close as you were going to get to an oral memory, slowly building on the insights of the past.

Like all the early Quakers, Robert Barclay spent some time in jail. He did visit America in 1681, but it is doubtful if he spent any time here while he was Governor of East Jersey, from 1682 to 1688. The King insisted on his appointment, because he seemed the most reasonable man among the most reasonable sect of dissenters, and therefore the rebel he chose to deal with.

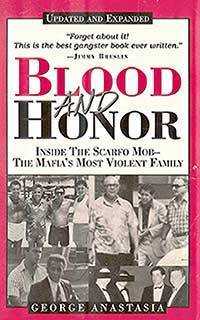

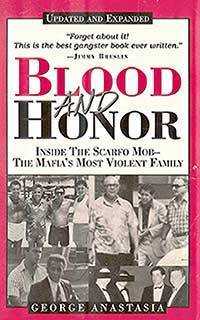

Blood and Honor: The Philadelphia Mafia, Lately

|

| Blood and Honor |

After two decades of seemingly endless dominance of Philadelphia headlines by the Mafia, the underworld has been absent from the news in the first decade of the 21st century. That's very welcome to everybody including the Mafia itself, and there are three main popular explanations. First, after 27 informal mob executions and four dozen convictions with lengthy prison terms, perhaps the mob has been eradicated. Or, possibly the immigrant population has been assimilated, now looking to quieter occupations for a source of income. And finally, maybe the mob has just decided to lie low while tax-hungry politicians enact enabling legislation for legal gambling casinos for the gullible public since the main argument against casinos is they attract crime. The histories of Atlantic City and Las Vegas certainly suggest organized crime has not yet abandoned casinos.

|

| George Anastasia |

George Anastasia's book Blood and Honor relates twenty years following the assassination of Angelo Bruno in 1980, averaging a murder or a prison sentence every three pages and leaving the reader with the impression of constant warfare in South Philadelphia. The book is pretty hair-raising, but after all, there is not much to talk about in a crime family except crime. To run through a brief overview of 27 assassinations and 36 major convictions is to leave a violent image of South Philadelphia. However, to say there were two to four assassinations per year plus three or four criminal trials softens that impact. The violence is appalling because it went on for so long. To note that Philadelphia like all major American cities its size, averages about three hundred murders a year puts mob violence in perspective. To be serious about eliminating homicide, you ought first eliminate "domestic violence". After that, you should go after street gangs and their focus on distributing recreational drugs.

Whether it was a struggle for control of Atlantic City casinos, a policy dispute over whether to get involved in illegal drugs, or simply a matter of disputed succession to control of the mob, is not now clear to the law-abiding community. What seems accepted interpretation is that matters heated up a lot after Angelo Bruno was assassinated. Somebody wanted his job, and that somebody wanted to run the organization differently. it's a situation quite familiar to CEOs of corporations, Kings and Emperors, and even editors of newspapers. What distinguishes organized crime families is the violence of their methods for dealing with succession issues. What emerges in this particular little world is that Nicodemo Scarfo established himself as the new Don of the Philadelphia Mafia by 1988, and the bitterness of this succession struggle induced six or ten insider members of the mob to become police informants to get revenge. The murders and convictions which make up this twenty-year period of time can be roughly divided into the initial struggle for control, the revenge of the losers, and the subsequent assassination of traitors. Even after inactivating nearly a hundred insiders, at least twice that number of "made" members and associates were unaffected directly. It's anyone's guess whether a defeat of this magnitude is enough to eliminate the organization, or whether it merely imposed a truce, during which the mob will heal its wounds and then make a comeback.

|

| Angelo Bruno |

An underground organization, whether in Philadelphia or Afghanistan, cannot hide effectively without the cooperation of honest citizens in the neighborhood. For many years, toleration was secured by keeping the streets safe from marauders belonging to other immigrant groups, and by collecting whatever debts the courts would not honor. The gray area involved such illegal activities as bootlegging in which the rest of the community participated without much sense of guilt. The Mafia was effectively a private police force for unsanctioned activity, operating within a neighborhood not fully in accord with prevailing attitudes. It seems to have been the genius of Angelo Bruno to realize that loan-sharking was the only permanently profitable component of this formula, and that loan sharking largely depended on gambling to create desperate debtors. Just about every other criminal activity attracted too much police attention to survive because the dominant society approved of suppression. Bruno's assassination seems to have been triggered by rebels who disagreed with his analysis. Perhaps they were right and the mob had been missing a big profit opportunity in the drug trade. Perhaps they were wrong and turned the legitimate community against them to the point where extermination was provoked.

Keep tuned. The outcome of this little debate could emerge suddenly and spectacularly. Or more decades of peace will pass silently, in which case Angelo will eventually be deemed correct.

REFERENCES

| Blood and Honor: Inside the Scarfo Mob, the Mafia's Most Violent Family George Anastasia ISBN-13: 978-0940159860 | Amazon |

| Before Bruno: The History of the Philadelphia Mafia Book 2 C. A. Morello ISBN: 978-0967733425 | Amazon |

| The Last Gangster George Anastasia ISBN-13: 978-0060544232 | Amazon |

| The Last Mouthpiece: The Man Who Dared to Defend the MobRobert F. Simone ISBN-13: 978-09401596932 | Amazon |

Lithuanian Law

The Right Angle Club was recently entertained by its rugby-playing, Kilimajaro-climbing member, John Wetzel, about his two-week stint teaching law students at the University of Vilnius. This ancient Lithuanian institution was founded in the 15th Century by Jesuits, and after a bumpy history of invasions and occupations has now re-established itself. It participates in Erasmus mobility, meaning it is one of 47 European universities which exchange credentials and permit students from any one of them to take courses in any other member of the association; evidently, similar mobility of faculty is also part of the concept. It sounds like a great idea, which American universities might well consider.

For reasons not entirely clear, 75% of the law students at Vilnius are female, and the whole local legal profession is similarly woman-dominated. John made several allusions to the general pulchritude of his students, which a class picture with him confirms. One striking feature of such a picture is how slim the ladies are; this is another European feature our own representatives might consider imitating. Since there are 2500 law students in a country of 3 million inhabitants, whose main industries are agricultural, balance is restored by only admitting 15% of the graduates to a passing grade on the bar examinations. It seems remarkable that studying law remains so popular under the circumstances, but it was explained that most of the graduates end up working for banks or government. Governments including our own frequently feel their laws don't apply to themselves.

|

| University of Vilnius |

If you think about it, a country which is attempting to convert from a Soviet colony to a member state of the European Community has a lot of loose ends to tie up. The title to a property is regularly clouded by the experience of confiscation by the government and then subsequently return to a free economy; if banks accept such collateral, there may well be a lot of legal work to be done to assure its security. Since the thirty-odd members of the European Community all have different legal systems in different languages, all banks and businesses which attempt to operate across borders require partners or consultants in law firms in many countries. While there is a continuous effort being made to establish some uniformity of laws in the various nations of the Community, it takes a fair amount of study just to know what the laws are and how they differ. Therefore, while a handful of lawyers are sufficient to appear in court in disputes and litigation, a great deal more legal background is required, just for businesses to know how they are expected to behave.

Since, as Justice Holmes remarked, the life of the law has not been logic, it has been experienced, it emerges that a great deal of effort must be expended to create the logic when there has been no preceding useful experience. The example is offered of American bankruptcy law, which did not exist until Robert Morris forced its creation. Morris had become an enormously wealthy man, and thus created an enormous tower of debts when his speculations failed, amounting to the then-staggering sum of $12 million of debt. They put him in debtors prison on Walnut Street, but that scarcely addressed the real problems of all those creditors tangled up in the mess. Lithuania is in a similar position, and although it has created a bankruptcy law for corporations, there is as yet no bankruptcy law covering individuals, and hence credit cards, etc. are difficult to establish.

There is a notable difference in attitudes between the eastern nations which were former members of the Soviet Union, and are intensely eager to learn more about the evolution of American law, and the more western parts of Europe, where disdain and hostility for American exceptionalism is presently dominant. A moment of reflection about this difference in a situation should make Americans more tolerant of western European problems. If the logic of law evolves out of the contemplation of experience, it may well be easier to begin without any usable experience, than to begin with centuries of experience which has to be re-examined. It must in fact be a wrenching experience, but one which has the potential to teach Americans a great many things we never had to cope with. The eventual outcome should be a healthy one, providing of course that we can keep our tempers, and acquire a little humility along the path.

Three Revolutions at Once, Maybe Four

The rise of the Tea Party movement in 2010 reopens a lifetime question in my mind. What was the American Revolutionary War all about; surely, a tax on tea isn't outrageous enough to go to war over, is it? It only aggravates curiosity to learn this particular law passed by the British Parliament, actually lowered the price of tea.

A somewhat different importance for the 21st Century is, of all the dozens or even hundreds of little civil wars that have popped up in the past two centuries, this American one seems to have had the biggest impact on the thoughts and behavior of the civilized world. The French Revolution comes close, but we meant to speak of persuasive influence on serious minds, not merely bloodiness and lasting grievance. Here are three suggestions, maybe four.

In retrospect, we can see the outlines of three major revolutions, coming together at the end of the 18th Century. The first is the Industrial Revolution, which had its beginnings in England around the city of Manchester. That was a region of major Quaker concentration, many of whom migrated to William Penn's social experiment in seeing what peace could do. The Industrial Revolution flourished in Great Britain far more readily than in France, and in a sense more than in America. But of the three major countries, America had the largest amount of unsettled land and the greatest natural resources of the three major countries. America was able to think bigger and broader, necessarily requiring broad support from an immigrant population. Diversity was often later to prove a mixed blessing, but in the Industrial Revolution it was vital.

|

| Dissent, French Style |

The second major revolution taking place at that time concerned the place of property in the life of every citizen. Up until that time, the King owned all the land and could redistribute it to suit his political needs. What critically mattered was not who formerly owned the land, but rather what was the latest King's latest word on who owned it right now. The American system gravitated to the notion that when the King or any other owner sold the land, it was no longer his; we now think that's quite self-evident. Each successive owner can sell it to his neighbor or bequeath it to his heirs, and at that moment it is no longer his, either. This idea of private property spread throughout the world, but in America, it was a clean sweep. Adopting the rather brutal rough justice of the frontier, the Indian prior ownership just didn't count. They had sided with the British in our revolution and were insistently resistant to assimilation. And anyway, Pope Nicholas in the 13th Century had established the notion of first discovery, which applied to Christians, only, and so Indians didn't count. Fair or unfair, this was going to be the way it was, from that point forward from 1787 when the Constitution was enacted. The longer the situation lasted, the more unlikely it became that it would ever change. America had so much land and so little coinage, that land itself became a sort of monetary standard. The particular American advantage was there was so much land that early settlers and landed gentry could not monopolize it; from meaning land at first, property soon meant any valuable possession. No King, particularly not George III, was going to take this away from the whole population on this side of the Atlantic. England could do as it pleased with its land and its King. If we needed Independence to preserve a general right to hold private property, plenty of men were willing to die to achieve it. And the whole Western world soon followed our example.

The third revolution was the one you read about, Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill and the Tea Act. That whole chain of events chronicles how America came to be Independent but somehow fails to explain why we wanted Independence. The Industrial and the Property revolutions explain it better, but such theorizing would certainly mystify the Revolutionaries themselves.

And finally, one begins to wonder if we aren't toying with a reversion to the ideas underlying monarchy when we examine some currently widespread views. There's a notion going about that everybody owns everything, which if carried to an extreme means no one owns anything. When you can notice people who live on the 70th floor of a Manhattan apartment building, proclaiming a right to tell Alaskans whether or not they can drill for oil, you behold this monarchy of the many. And when you see prosperous educated adults shouting at rallies, you can see Alaskans, for example, want to tell New Yorkers to mind their own business. This land, they seem to say, isn't everybody's at all, it is mine.

It never really was entirely the King's, either. The King was a single person, sometimes a rather brutal one who wasn't likely to tolerate advice from his subjects. At times of crisis, somebody has to make a decision, any decision, and act on it. But most of the time, kings seemed to be in the position of that Czar. The one who said, "I don't rule Russia. Ten thousand clerks rule Russia."

Pennsylvania Likes Private Property Private

|

| William Penn Holding his Charter |

William Penn was the largest private landowner in America, maybe the whole world. He owned all of Pennsylvania, with the states of Delaware and New Jersey sort of thrown in. Although he and his descendants tried actively to sell off his real estate from 1684 to 1783, they still held an unsold three-fifths of it at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, which they were forced to sell to the state for about fifteen cents per acre. This bit of history partly explains both the strong feeling this is private, not communal, land despite the existence of 2.3 million acres of the state forest system, which is affirmed right alongside the rather inconsistent feeling that raw land is somehow inexhaustible. Early settlers regarded the center of the state as poor farmland, particularly when compared with soil found in Lancaster and Dauphin Counties, or anticipated by settlers going to Ohio and Southern Illinois. A complimentary description is that glaciers descended to about the middle of Pennsylvania, denuding the northern half of topsoil which was then dumped on the southern part as the glaciers receded. Even today, farmers tend to avoid the northern region if they can, reciting the ancient advice from their fathers that "Only a Mennonite can make a go of it, around there."

So, lumbering had a century-long flurry in Central Pennsylvania, exhausting the trees and moving on. But that only related to the top layer of soil; beneath it lay anthracite in the East, and bituminous coal in Western Pennsylvania, supporting the steel industries of the two ends of the state with exuberant railroad development. Even today worldwide, hauling coal is the chief money-maker for railroads. The resulting availability of rail transport promotes the location of heavy industry near coal regions; the 20th Century decline of coal demand ultimately hurried the decline of heavy industry in the state by impairing the railroads.

Beneath all this lie the aquifers, porous caverns of fresh water. And beneath that, largely unsuspected for two centuries, lie the sedimentary deposits of a huge inland sea, compressed into petroleum which evaporates into natural gas. All of this is held by huge deposits of semi-porous shale rock, now mostly 8000 feet deep, stretching from Canada to Texas and called the Marcellus shale formation. If it can be economically recovered, there is more natural gas than in Arabia, and there is a similar formation along the near side of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, stretching up to the Athabasca tar sands in Canada. There is another similar formation in France underneath Paris. No doubt, we will find the whole world has similar huge deposits for which the main problem has always been: how do you get it out?

There's another question, of course, of who owns it. Those who clearly do not own it maintain that everyone owns it. In the western world, most particularly in America, it is our firm belief that if you live on top of it, you own it. Since it is expensive to extract, quarrels like this are usually settled by purchasing mineral rights from the surface owner, who generally could not possibly extract it by himself. Those who assert they have a conflicting right to it because it belongs to everyone can expect belligerent resistance. At the present time when America faces a critical fifteen year period of dwindling oil supply, ultimately relieved by perfecting alternative energy sources, there is too little time to achieve consensus for any other governance theory. The problem which could possibly gain enough traction to interfere is the issue of potential damage to others which might result from the extraction of this subsurface treasure. Because of the apparent urgency of a decision to extract or go elsewhere to extract, the best we can hope for is some fairly rough justice.

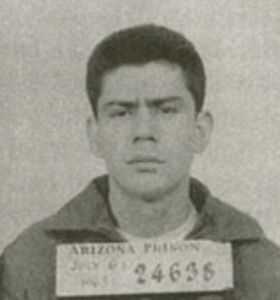

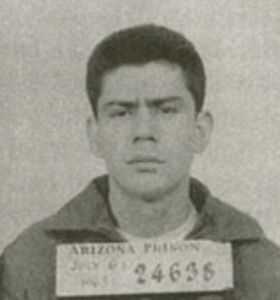

Original Intent and the Miranda Decision

|

| Ernesto Arturo Miranda |

At the lunch table of the Franklin Inn Club recently, the Monday Morning Quarterbacks listened to a debate about Guantanamo Bay, prisoner torture and police brutality; all of which centered on the Supreme Court decision known as Miranda v Arizona. Ernesto Arturo Miranda was convicted without being warned of his right to remain silent, sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison in 1966. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court, with Chief Justice Earl Warren writing a 5-4 decision, overturned the conviction, because Miranda had not been officially warned of his right to remain silent. The case was retried and Miranda was convicted and imprisoned on the basis of other evidence that included no confession.

An important fact about this case was that Congress soon wrote legislation making the reading of "Miranda Rights" unnecessary, but the Supreme Court then declared in the Dickerson case that Congress had no right to overturn a Constitutional right. Some of the subsequent fury about the Miranda case concerned the legal box it came in, with empowering the Supreme Court to create a new right that is not found in the written Constitution. Worse still, declaring it was not even subject to any other challenge by the other branches of government. In the view of some, this was a judicial power grab in a class with Marbury v Madison.

Several lawyers were at the lunch table on Camac Street, seemingly in agreement that Miranda was a good thing because the core of it was not to forbid unwarned interrogation, but rather a desirable refinement of court procedure to prohibit the introduction of such evidence into a trial. The lawyers pointed out the majority of criminal cases simply skirt this sort of evidence, use other sorts of evidence, and the criminals are routinely sent or not sent to jail without much influence from the Miranda issue. Indeed, Miranda himself was subsequently imprisoned on the basis of evidence which excluded his confession. What's all the fuss about?

And then, the agitated non-lawyers at the lunch table proceeded to display how deeper issues have overtaken this little rule of procedure. This Miranda principle prevents police brutality. Answer: It does not; it only prevents the use of testimony obtained by brutality from being introduced at trial. Secondly, Miranda contains an exception for issues of immediate public safety. Answer: What difference does that make, as long as the authorities refrain from using the confession in court? The chances are good that a person visibly endangering public safety is going to be punished without a confession. Further, the detailed procedures within Miranda encourage fugitives to discard evidence before they are officially arrested in a prescribed way. Answer: If the police officer sees guns or illicit drugs being thrown on the ground, do you think he needs a confession? Well, what about Guantanamo Bay? Answer: What about it? We understand the prisoners are there mainly to obtain information about the conspiracy abroad and to keep them from rejoining it. The alternative would likely be their execution, either by our capturing troops or by vengeful co-conspirators they had incriminated.

Somehow, this cross-fire seemed unsatisfying. The Miranda decision was made by a 5-4 majority, meaning a switch of a single vote would have reversed the outcome. The private discussions of the justices are secret, but it seems likely that some Justices were swayed by this edict viewed as a simple improvement in court procedure rather than a constitutional upheaval; Justices with that viewpoint feel they know the original intent and approve of it. Others are apprehensive the decision has already migrated from the original intent, in an alarming way. Everyone who watches much crime television and even many police officials feels that Miranda intends for all suspects to be tried on the basis of total isolation from interrogation from start to finish. More reasoned observers are alarmed that the process of discrediting all interrogation will lead to an ongoing disregard of the opinion of lawyers about court procedure, essentially the process of allowing public misunderstanding to overturn legal standards. Chief Justice William Renquist, no less, poured gasoline on this anxiety by declaring that Miranda has "become part of our culture".

What seems to be on display is the mechanism by which Constitutional interpretation drifts from the original intent. Not so much a matter of "Judicial Activism" which is "legislating from the bench", it is becoming a matter of non-lawyers confusing and stirring up the crowds until the Justices simply give up the argument. Drift is one thing; virtual bonfires and virtual torch-light parades are quite another.

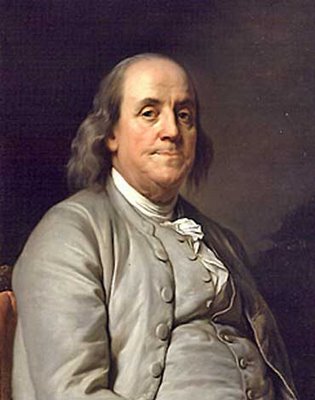

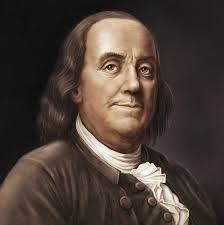

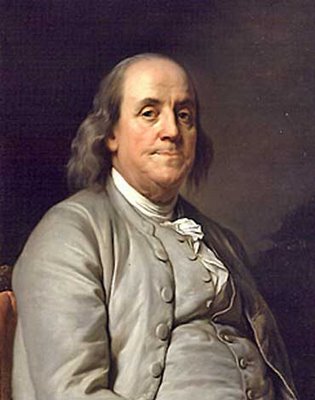

Last Will of Benjamin Franklin

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

The Last Will and Testament of Benjamin Franklin

I, Benjamin Franklin, of Philadelphia, printer, late Minister Plenipotentiary from the United States of America to the Court of France, now President of the State of Pennsylvania, do make and declare my last will and testament as follows:

|

| William Franklin |

To my son, William Franklin, late Governor of the Jerseys, I give and devise all the lands I hold or have a right to, in the province of Nova Scotia, to hold to him, his heirs, and assigns forever. I also give to him all my books and papers, which he has in his possession, and all debts standing against him on my account books, willing that no payment for, nor restitution of, the same be required of him, by my executors. The part he acted against me in the late war, which is of public notoriety, will account for my leaving him no more of an estate he endeavored to deprive me of.

Having since my return from France demolished the three houses in Market Street, between Third and Fourth Streets, fronting my dwelling-house, and erected two new and larger ones on the ground, and having also erected another house on the lot which formerly was the passage to my dwelling, and also a printing-office between my dwelling and the front houses; now I do give and devise my said dwelling-house, wherein I now live, my said three new houses, my printing- office and the lots of ground thereto belonging; also my small lot and house in Sixth Street, which I bought off the widow Henmarsh; also my pasture-ground which I have in Hickory Lane, with the buildings thereon; also my house and lot on the North side of Market Street, now occupied by Mary Jacobs, together with two houses and lots behind the same, and fronting on Pewter-Platter Alley; also my lot of ground in Arch Street, opposite the church-burying ground, with the buildings thereon erected; also all my silver plate, pictures, and household goods, of every kind, now in my said dwelling-place, to my daughter, Sarah Bache, and to her husband, Richard Bache, to hold to them for and during their natural lives, and the life of the longest liver of them, and from and after the decease of the survivor of them, I do give, devise, and bequeath to all children already born, or to be born of my said daughter, and to their heirs and assigns forever, as tenants in common, and not as joint tenants.

And, if any or either of them shall happen to die under age, and without issue, the part and share of him, her, or them, so dying, shall go to and be equally divided among the survivors or survivor of them. But my intention is, that, if any or either of them should happen to die under age, leaving issue, such issue shall inherit the part and share that would have passed to his, her, or their parent, had he, she, or they were living.

And, as some of my said devisees may, at the death of the survivor of their father or mother, be of age, and others of them underage, so as that all of them may not be of capacity to make division, I in that case request and authorize the judges of the Supreme Court of Judicature of Pennsylvania for the time being, or any three of them, not personally interested, to appoint by writing, under their hands and seals, three honest, intelligent, impartial men to make the said division, and to assign and allot to each of my devisees their respective share, which division, so made and committed to writing under the hands and seals of the said three men, or any two of them, and confirmed by the said judges, I do hereby declare shall be binding on, and conclusive between the said devisees.

All the lands near the Ohio, and the lots near the centre of Philadelphia, which I lately purchased of the State, I give to my son-in-law, Richard Bache, his heirs and assigns forever; I also give him the bond I have against him, of two thousand and one hundred and seventy-two pounds, five shillings, together with the interest that shall or may accrue thereon, and direct the same to be delivered up to him by my executors, canceled, requesting that, in consideration thereof, he would immediately after my decease manumit and set free his Negro man Bob. I leave to him, also, the money due to me from the State of Virginia for types. I also give to him the bond of William Goddard and his sister, and the counter bond of the late Robert Grace, and the bond and judgment of Francis Childs, if not recovered before my decease, or any other bonds, except the bond due from ----- Killian, of Delaware State, which I give to my grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache. I also discharge him, my said son-in-law, from all claim and rent of money due to me, on book account or otherwise. I also give him all my musical instruments.

|

| Sarah Bache |

The king of France's picture, set with four hundred and eight diamonds, I give to my daughter, Sarah Bache, requesting , however, that she would not form any of those diamonds into ornaments either for herself or daughters, and thereby introduce or countenance the expensive, vain, and useless fashion of wearing jewels in this country; and those immediately connected with the picture may be preserved with the same.

I give and devise to my dear sister, Jane Mecom, a house and lot I have in Unity Street, Boston, nor or late under the care of Mr. Jonathan Williams, to her and to her heirs and assigns forever. I also give her the yearly sum of fifty pounds sterling, during life, to commence at my death, and to be paid to her annually out of the interests or dividends arising on twelve shares which I have since my arrival at Philadelphia purchased in the Bank of North America, and, at her decease, I give the said twelve shares in the bank to my daughter, Sarah Bache, and her husband, Richard Bache. But it is my express will and desire that, after the payment of the above fifty pounds sterling annually to my said sister, my said daughter be allowed to apply the residue of the interest or dividends on those shares to her sole and separate use, during the life of my said sister, and afterwards the whole of the interest or dividends thereof as her private pocket money.

I give the right I have to take up to three thousand acres of land in the State of Georgia, granted to me by the government of that State, to my grandson, William Temple Franklin, his heirs and assigns forever. I also give to my grandson, William Temple Franklin, the bond and judgment I have against him of four thousand pounds sterling, my right to the same to cease upon the day of his marriage; and if he dies unmarried, my will is, that the same be recovered and divided among my other grandchildren, the children of my daughter, Sarah Bache, in such manner and form as I have herein before given to them the other parts of my estate.

The philosophical instruments I have in Philadelphia I give to my ingenious friend, Francis Hopkinson.

To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of my brother, Samuel Franklin, that may be living at the time of my decease, I give fifty pounds sterling, to be equally divided among them. To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of my sister, Anne Harris, that may be living at the time of my decease, I give fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided among them. To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of my brother James Franklin, that may be living at the time of my decease, I give fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided among them. To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of my sister, Sarah Davenport, that may be living at the time of my decease, I give fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided among them. To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of my sister, Lydia Scott, that may be living at the time of my decease, I give fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided among them. To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of my sister, Jane Mecom, that may be living at the time of my decease, I give fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided among them.

I give to my grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache, all the types and printing materials, which I now have in Philadelphia, with the complete letter foundry, which, in the whole, I suppose to be worth near one thousand pounds; but if he should die under age, then I do order the same to be sold by my executors, the survivors or survivor of them, and the money be equally divided among all the rest of my said daughter's children, or their representatives, each one on coming of age to take his or her share, and the children of such of them as may die under age to represent and to take the share and proportion of, the parent so dying, each one to receive his or her part of such share as they come of age.

With regard to my books, those I had in France and those I left in Philadelphia, is now assembled together here, and a catalog made of them, it is my intention to dispose of them as follows: My "History of the Academy of Sciences," in sixty or seventy volumes quarto, I give to the Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, of which I have the honor to be President. My collection in a folio of "Les Arts et les Metiers," I give to the American Philosophical Society, established in New England, of which I am a member. My quarto edition of the same, "Arts et Metiers," I give to the Library Company of Philadelphia. Such and so many of my books as I shall mark on my said catalog with the name of my grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache, I do hereby give to him; and such and so many of my books as I shall mark on the said catalog with the name of my grandson, William Bache, I do hereby give to him; and such as shall be marked with the name of Jonathan Williams, I hereby give to my cousin of that name. The residue and remainder of all my books, manuscripts, and papers, I do give to my grandson, William Temple Franklin. My share in the Library Company of Philadelphia, I give to my grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache, confiding that he will permit his brothers and sisters to share in the use of it.

I was born in Boston, New England, and owe my first instructions in literature to the free grammar schools established there. I, therefore, give one hundred pounds sterling to my executors, to be by them, the survivors or survivor of them, paid over to the managers or directors of the free schools in my native town of Boston, to be by them, or by those person or persons, who shall have the superintendence and management of the said schools, put out to interest, and so continued at interest forever, which interest annually shall be laid out in silver medals, and given as honorary rewards annually by the directors of the said free schools belonging to the said town, in such manner as to the discretion of the selectmen of the said town shall seem meet.

Out of the salary that may remain due to me as President of the State, I do give the sum of two thousand pounds sterling to my executors, to be by them, the survivors or survivor of them, paid over to such person or persons as the legislature of this State by an act of Assembly shall appoint to receive the same in trust, to be employed for making the river Schuylkill navigable.

And what money of mine shall, at the time of my decease, remain in the hands of my bankers, Messrs. Ferdinand Grand and Son, at Paris, or Messrs. Smith, Wright, and Gray, of London, I will that, after my debts are paid and deducted, with the money legacies of this my will, the same be divided into four equal parts, two of which I give to my dear daughter, Sarah Bache, one to her son Benjamin, and one to my grandson, William Temple Franklin.

During the number of years I was in business as a stationer, printer, and postmaster, a great many small sums became due for books, advertisements, postage of letters, and other matters, which were not collected when, in 1757, I was sent by the Assembly to England as their agent, and by subsequent appointments continued there till 1775, when on my return, I was immediately engaged in the affairs of Congress and sent to France in 1776, where I remained nine years, not returning till 1785, and the said debts, not being demanded in such a length of time, are become in a manner obsolete, yet are nevertheless justly due. These, as they are stated in my great folio ledger E, I bequeath to the contributors to the Pennsylvania Hospital, hoping that those debtors, and the descendants of such as are deceased, who now, as I find, make some difficulty of satisfying such antiquated demands as just debts, may, however, be induced to pay or give them as charity to that excellent institution. I am sensible that much must inevitably be lost, but I hope something considerable may be recovered. It is possible, too, that some of the parties charged may have existing old, unsettled accounts against me; in which case the managers of the said hospital will allow and deduct the amount, or pay the balance if they find it against me.

My debts and legacies being all satisfied and paid, the rest and residue of all my estate, real and personal, not herein expressly disposed of, I do give and bequeath to my son and daughter, Richard and Sarah Bache.

I request my friends, Henry Hill, Esquire, John Jay, Esquire, Francis Hopkinson, Esquire, and Mr. Edward Duffield, of Benfield, in Philadelphia County, to be the executors of this my last will and testament; and I hereby nominate and appoint them for that purpose.

I would have my body buried with as little expense or ceremony as may be. I revoke all former wills by me made, declaring this only to be my last.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and seal, this seventeenth day of July, in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-eight.

B. Franklin

Signed, sealed, published, and declared by the above named Benjamin Franklin, for and as his last will and testament, in the presence of us.

Abraham Shoemaker, John Jones, George Moore.

CODICIL

I, Benjamin Franklin, in the foregoing or annexed last will and testament named, having further considered the same, do think proper to make and publish the following codicil or addition thereto.

It has long been a fixed political opinion of mine, that in a democratical state there ought to be no offices of profit, for the reasons I had given in an article of my drawing in our constitution, it was my intention when I accepted the office of President, to devote the appointed salary to some public uses. Accordingly, I had already, before I made my will in July last, given large sums of it to colleges, schools, the building of churches, etc.; and in that will I bequeathed two thousand pounds more to the State for the purpose of making the Schuylkill navigable. But understanding since that such a work, and that the project is not likely to be undertaken for many years to come, and having entertained another idea, that I hope may be more extensively useful, I do hereby revoke and annul that bequest, and direct that the certificates I have for what remains due to me of that salary be sold, towards raising the sum of two thousand pounds sterling, to be disposed of as I am now about to order.

It has been an opinion, that he who receives an estate from his ancestors is under some kind of obligation to transmit the same to their posterity. This obligation does not lie on me, who never inherited a shilling from an ancestor or relation. I shall, however, if it is not diminished by some accident before my death, leave a considerable estate among my descendants and relations. The above observation is made as merely as some apology to my family for making bequests that do not appear to have any immediate relation to their advantage.

I was born in Boston, New England, and owe my first instructions in literature to the free grammar schools established there. I have, therefore, already considered these schools in my will. But I am also under obligations to the State of Massachusetts for having, unasked, appointed me formerly their agent in England, with a handsome salary, which continued some years; and although I accidentally lost in their service, by transmitting Governor Hutchinson's letters, much more than the amount of what they gave me, I do not think that ought in the least to diminish my gratitude.

I have considered that, among artisans, good apprentices are most likely to make good citizens, and, having myself been bred to a manual art, printing, in my native town, and afterward assisted to set up my business in Philadelphia by kind loans of money from two friends there, which was the foundation of my fortune, and all the utility in life that may be ascribed to me, I wish to be useful even after my death, if possible, in forming and advancing other young men, that may be serviceable to their country in both these towns. To this end, I devote two thousand pounds sterling, of which I give one thousand thereof to the inhabitants of the town of Boston, in Massachusetts, and the other thousand to the inhabitants of the city of Philadelphia, in trust, to and for the uses, intents, and purposes hereinafter mentioned and declared.

The said sum of one thousand pounds sterling, if accepted by the inhabitants of the town of Boston, shall be managed under the direction of the selectmen, united with the ministers of the oldest Episcopalians, Congregational, and Presbyterian churches in that town, who are to let out the sum upon interest, at five per cent, per annum, to such young married artificers, under the age of twenty-five years, as have served an apprenticeship in the said town, and faithfully fulfilled the duties required in their indentures, so as to obtain a good moral character from at least two respectable citizens, who are willing to become their sureties, in a bond with the applicants, for the repayment of the moneys so lent, with interest, according to the terms hereinafter prescribed; all which bonds are to be taken for Spanish milled dollars, or the value thereof in current gold coin; and the managers shall keep a bound book or books, wherein shall be entered the names of those who shall apply for and receive the benefits of this institution, and of their sureties, together with the sums lent, the dates, and other necessary and proper records respecting the business and concerns of this institution. And as these loans are intended to assist young married artificers in setting up their business, they are to be proportioned by the discretion of the managers, so as not to exceed sixty pounds sterling to one person, nor to be less than fifteen pounds; and if the number of appliers so entitled should be so large as that the sum will not suffice to afford to each as much as might otherwise not be improper, the proportion to each shall be diminished so as to afford to everyone some assistance. These aids may, therefore, be small at first, but, as the capital increases by the accumulated interest, they will be ampler. And in order to serve as many as possible in their turn, as well as to make the repayment of the principal borrowed easier, each borrower shall be obliged to pay, with the yearly interest, one-tenth part of the principal and interest, so paid in, shall be again let out to fresh borrowers.

And, as it is presumed that there will always be found in Boston virtuous and benevolent citizens, willing to bestow a part of their time in doing good to the rising generation, by superintending and managing this institution gratis, it is hoped that no part of the money will at any time be dead, or be diverted to other purposes, but be continually augmenting by the interest; in which case there may, in time, be more than the occasions in Boston shall require, and then some may be spared to the neighboring or other towns in the said State of Massachusetts, who may desire to have it; such towns engaging to pay punctually the interest and the portions of the principal, annually, to the inhabitants of the town of Boston.

If this plan is executed, and succeeds as projected without interruption for one hundred years, the sum will then be one hundred and thirty-one thousand pounds; of which I would have the managers of the donation to the town of Boston then layout, at their discretion, one hundred thousand pounds in public works, which may be judged of most general utility to the inhabitants, such as fortifications, bridges, aqueducts, public buildings, baths, pavements, or whatever may make living in the town more convenient to its people, and render it more agreeable to strangers resorting thither for health or a temporary residence. The remaining thirty-one thousand pounds I would have continued to be let out on interest, in the manner above directed, for another hundred years, as I hope it will have been found that the institution has had a good effect on the conduct of youth, and been of service to many worthy characters and useful citizens. At the end of this second term, if no unfortunate accident has prevented the operation, the sum will be four million and sixty-one thousand pounds sterling, of which I leave one million sixty-one thousand pounds to the disposition of the inhabitants of the town of Boston, and three million to the disposition of the government of the state, not presuming to carry my views farther.

All the directions herein given, respecting the disposition and management of the donation to the inhabitants of Boston, I would have observed respecting that to the inhabitants of Philadelphia, only, as Philadelphia is incorporated, I request the corporation of that city to undertake the management agreeably to the said directions; and I do hereby vest them with full and ample powers for that purpose. And, having considered that the covering a ground plot with buildings and pavements, which carry off most of the rain and prevent its soaking into the Earth and renewing and purifying the Springs, whence the water of wells must gradually grow worse, and in time be unfit for use, as I find has happened in all old cities, I recommend that at the end of the first hundred years, if not done before, the corporation of the city Employ a part of the hundred thousand pounds in bringing, by pipes, the water of Wissahickon Creek into the town, so as to supply the inhabitants, which I apprehend may be done without great difficulty, the level of the creek is much above that of the city, and may be made higher by a dam. I also recommend making the Schuylkill completely navigable. At the end of the second hundred years, I would have the disposition of the four million and sixty-one thousand pounds divided between the inhabitants of the city of Philadelphia and the government of Pennsylvania, in the same manner as herein directed with respect to that of the inhabitants of Boston and the government of Massachusetts.

It is my desire that this institution should take place and begin to operate within one year after my decease, for which purpose due notice should be publicly given previous to the expiration of that year, that those for whose benefit this establishment is intended may make their respective applications. And I hereby direct my executors, the survivors or survivor of them, within six months after my decease, to pay over the sum of two thousand pounds sterling to such persons as shall be duly appointed by the Selectmen of Boston and the corporation of Philadelphia, to receive and take charge of their respective sums, of one thousand pounds each, for the purposes aforesaid.

Considering the accidents to which all human affairs and projects are subject in such a length of time, I have, perhaps, too much flattered myself with a vain fancy that these dispositions, if carried into execution, will be continued without interruption and have the effects proposed. I hope, however, that is the inhabitants of the two cities should not think fit to undertake the execution, they will, at least, accept the offer of these donations as a mark of my good will, a token of my gratitude, and a testimony of my earnest desire to be useful to them after my departure.

I wish, indeed, that they may both undertake to endeavor the execution of the project, because I think that, though unforeseen difficulties may arise, expedients will be found to remove them, and the scheme be found practicable. If one of them accepts the money, with the conditions, and the other refuses, my will then is, that both Sums be given to the inhabitants of the city accepting the whole, to be applied to the same purposes, and under the same regulations directed for the separate parts; and, if both refuse, the money, of course, remains in the mass of my Estate, and is to be disposed of therewith according to my will made the Seventeenth day of July, 1788.

I wish to be buried by the side of my wife, if it may be, and that a marble stone, to be made by Chambers, six feet long, four feet wide, plain, with only a small molding around the upper edge, and this inscription:

Benjamin And Deborah Franklin 178-

to be placed over us both. My fine crab-tree walking stick, with a gold head, curiously wrought in the form of the cap of liberty, I give to my friend, and the friend of mankind, General Washington. If it were a Sceptre, he has merited it and would become it. It was a present to me from that excellent woman, Madame de Forbach, the Dowager Duchess of Deux-Ponts, connected with some verses which should go with it. I give my gold watch to my son-in-law Richard Bache, and also the gold watch chain of the Thirteen United States, which I have not yet worn. My timepiece, that stands in my library, I give to my grandson, William Temple Franklin. I give him also my Chinese gong. To my dear old friend, Mrs. Mary Hewson, I give one of my silver tankards marked for her use during her life, and after her decease, I give it to her daughter Eliza. I give to her son, William Hewson, who is my godson, my new quarto Bible, and also the botanic description of the plants in the Emperor's garden at Vienna, in folio, with colored cuts.

And to her son, Thomas Hewson, I give a set of "Spectators, Tattlers, and Guardians" handsomely bound.

There is an error in my will, where the bond of William Temple Franklin is mentioned as being four thousand pounds sterling, whereas it is but for three thousand five hundred pounds.

I give to my executors, to be divided equally among those that act, the sum of sixty pounds sterling, as some compensation for their trouble in the execution of my will; and I request my friend, Mr. Duffield, to accept moreover my French waywiser, a piece of clockwork in Brass, to be fixed to the wheel of any carriage; and that my friend, Mr. Hill, may also accept my silver cream pot, formerly given to me by the good Doctor Fothergill, with the motto, Keep bright the Chain. My reflecting telescope, made by Short, which was formerly Mr. Canton's, I give to my friend, Mr. David Rittenhouse, for the use of his observatory.

My picture, drawn by Martin, in 1767, I give to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, if they shall be pleased to do me the honor of accepting it and placing it in their chamber. Since my will was made I have bought some more city lots, near the center part of the estate of Joseph Dean. I would have them go with the other lots, disposed of in my will, and I do give the same to my Son-in-law, Richard Bache, to his heirs and assigns forever.

In addition to the annuity left to my sister in my will, of fifty pounds sterling during her life, I now add thereto ten pounds sterling more, in order to make the Sum sixty pounds. I give twenty guineas to my good friend and physician, Dr. John Jones.

With regard to the separate bequests made to my daughter Sarah in my will, my intention is, that the same shall be for her sole and separate use, notwithstanding her coverture, or whether she be covert or sole; and I do give my executors so much right and power therein as may be necessary to render my intention effectual in that respect only. This provision for my daughter is not made out of any disrespect I have for her husband.

And lastly, it is my desire that this, my present codicil, be annexed to, and considered as part of, my last will and testament to all intents and purposes.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and Seal this twenty-third day of June, Anno Domini one thousand Seven hundred and eighty-nine.

B. Franklin.

Signed, sealed, published, and declared by the above named Benjamin Franklin to be a codicil to his last will and testament, in the presence of us.

Francis Bailey, Thomas Lang, Abraham Shoemaker.

Regulation Precision: Not Entirely a Good Idea

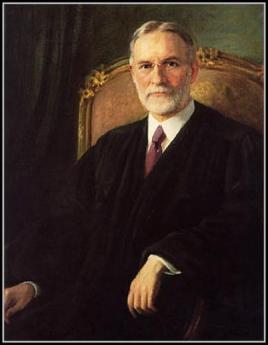

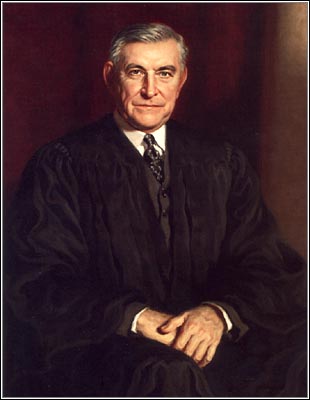

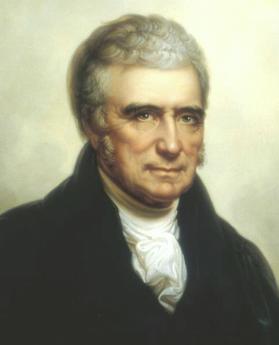

Owen Roberts: A Switch in Time

|

| Owen Roberts |

To this day, no one knows quite what to make of Owen J. Roberts, founder of one of Philadelphia's largest law firms. He was Prosecutor of the Teapot Dome scandal, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Republican appointee to the U.S. Supreme Court. But then, he abruptly became the source of one of the most radical revisions of our system of government since the Declaration of Independence. Nothing in his prior career and nothing afterward in his subsequent civic-minded retirement from the Court seemed to suggest any radical turn of character had taken place. He has been compared with a famous baseball pitcher who threw right-handed or left-handed at will, unexpectedly, capriciously, who knows why.

The issue went far beyond one clause in the Constitution, but the commerce clause was the focus point. Under the limited and enumerated powers allowed to Congress by the Constitution was :

The Congress shall have power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

That used to be called the interstate commerce clause until the Supreme Court announced its decision in the case of Wickard v. Filburn. When linked with the Tenth Amendment, granting to the States the power to regulate everything not specifically granted to the Federal government, this clause in the Constitution was universally taken to mean that the States had control of commerce within their borders, while Congress would control interstate commerce. Wickard v. Filburn took all that power from the states and gave it to Congress, which henceforth would regulate commerce. John Marshall had certainly triumphed over the hated state legislatures, but the Supreme Court suddenly lost its power to overrule Congress, too. One side had won the old argument, by silencing the umpire. No wonder Franklin Roosevelt started annual celebrations called Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners.

To describe the background: The 1929 stock market crash was quickly followed by the economic Depression of the 1930s. Nothing of this magnitude had been seen before, and there was a stampede to try new and untested solutions. Even government action which actually worsened economic conditions was felt justified if it conveyed to the frightened public the image that its leaders were taking firm action. Since Socialism and Communism were among the solutions grasped for, many unfortunate actions were felt justified as a way to control the Bolshevik threat. Many of these New Deal actions were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court since they involved sweeping revisions in the way all commerce, internal to the States as well as interstate, was conducted.

The Depression and financial panic continued through the 1936 Presidential election, which Roosevelt won in a landslide. Immediately after the start of the new term, he announced a plan to increase the number of Justices on the Supreme Court, appointing new ones more to his liking. He was at pains to point out that seven of the nine life incumbents had been appointed by Republican Presidents. This was, of course, the restraint intended by the Constitutional Convention, and the idea of packing the Court with new appointees was exactly what Jefferson and Jackson had tried to do.

|

| Franklin Roosevelt |

In the meantime, the case of Filburn, a dairy farmer, came up. One of the New Deal agencies had assigned him a quota of 200 bushels of wheat he could grow on the side, as part of an effort to raise wheat prices by reducing supply. Filburn had raised 400 bushels, but consumed the extra wheat for his own personal use, hardly a matter of interstate commerce. The Court had repeatedly declared laws like this to exceed the interstate commerce limitation and were thus unconstitutional for the Congress to enact.

Well, Owen Roberts changed his position, Filburn lost his case. Forever afterward, this change of position was referred to as the switch in time, that saved nine. Since that time, the Court has rarely had the courage to rule any action of Congress unconstitutional, even though it is true that Congress promptly and resoundingly rejected the court-packing proposal.

And furthermore, the power of the state legislatures has shriveled because all commerce (except insurance and real estate) is federally regulated, with a corresponding vast increase in the size of the Federal bureaucracy, as Congress relentlessly pushes to intervene in commerce among the several states, formerly known as the Interstate Commerce Clause. Franklin Roosevelt had a certain right to gloat at Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners.

A few weeks before he died, Owen Roberts had all his papers burned. Apparently, we will never know whether the present outcome was the result he had in mind. Since he was later the author of Alfred Barnes' will, which strenuously sought to prevent the transfer of the Barnes art collection to Philadelphia County, anything written by a lawyer can apparently be reversed by other lawyers. One would have supposed that either the Original Intent would govern, or else the opinion of the Supreme Court on what the Constitution means, would prevail. Franklin Roosevelt showed us there is a third possibility: the President can overrule the Court by intimidating it.

Franklin Endorses the Constitution

Monday Sepr. 17, 1787. In Convention (6th and Chestnut, Philadelphia).

The Engrossed Constitution being read, Doctor. Franklin rose with a Speech in his hand, which he had reduced to writing for his own convenience, and which Mr. Wilson read in the words following:

|

| Bust of Benjamin Franklin |

I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, then after I am to doubt my own judgment and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. Most men indeed as well as most sects in Religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them it is so far error. Steele, a Protestant in a Dedication tells the Pope, that the only difference between our Churches in their opinions of the certainty of their doctrines is, the Church of Rome is infallible and the Church of England is never in the wrong. But though many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility as of that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain French lady, who in a dispute with her sister, said, "I don't know how it happens, Sister, but I meet with nobody but myself, that's always in the right"- "Il n'y a que moi quia Toujours reason."

|

| The signing of the Constitution |

In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of Government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered, and believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in Despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic Government, being incapable of any other. I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an Assembly can a perfect production be expected? It, therefore, astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our councils are confounded like those of the Builders of Babel; and that our States are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one another's throats. Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its error, I sacrifice to the public good--I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad-- Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die--If every one of us in returning to our Constituents were to report the objections he has had to it, and endeavor to gain partisans in support of them, we might prevent it is being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary effects and great advantages resulting naturally in our favor among foreign Nations as well as among ourselves, from our real or apparent unanimity. Much of the strength and efficiency of any Government in procuring and securing happiness to the people, depends, on opinion, on the general opinion of the goodness of the Government, as well as of the wisdom and integrity of its Governors. I hope therefore that for our own sakes as a part of the people and for the sake of our posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution (if approved by Congress and confirmed by the Conventions) wherever our influence may extend, and turn our future thoughts and endeavors to the means of having it well administered.

On the whole, Sir, I cannot help expressing a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility--and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this instrument.

He then moved that the Constitution be signed.

When the last members were signing it, Doctor Franklin looking towards the President's Chair, at the back of which a rising sun happened to be painted, observed to a few members near him, that Painters had found it difficult to distinguish in their art a rising from a setting sun. I have, said he, often and often in the course of the Session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issues, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.

WILLIAM BLATHWAYT'S DRAFT OF THE CHARTER OF PENNSYLVANIA

Charles the Second, by the grace of [God] King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, Defend[er] of the Faith & Co. To all to whom these presents shall come, greeting.

Whereas our truste[d] and well beloved subject William Penn Esquire, sonne and heire of Sir William Penn, deceased, out of a comendable desire to enlarge our English Empire and promote such usefull comodities as may be of benefit to us and our dominions, as also to reduce the Savage Natives by Gentle and just manners to the Love of civill Society and Christian Religion, hath humbly besought leave of us to transport an ample Colony unto a certaine Country hereinafter described in the parte of America not yet cultivated and planted. And hath likewise humbly besought our Royall Ma[jes]tie to give, grant, and confirme all the said Country with certaine priviledges and Jurisdicions requisite for the good government and safety of the said Country and Colony, to him and his heires for ever. Know yee therefore that wee, favoring the petition and good purpose of the said William Penn, and haveing regard to the memory and merits of his late Father in diverse services and particularly to his conduct, courage, and dircctione {discretion} under our dearest Brother James, Duke of Yorke, in that signall Battle and Victorie fought and obtained against the Dutch Fleet comanded by [illegible word deleted] {The}2 Heer Van Obdam in the yeare 1653. In consideration thereof of our speciall grace, certaine knowledge, and meere motion have given and granted and by this our present Charter for us our heires and successors, doe give and grant unto the said William Penn his heires and Assignes

All that Tract or part of Land of {in}4 America with all the Islands therein contained as the same is bounded on the East by Delaware River from Twelve miles distance Northwards of Newcastle Towne unto the Three and Fortieth degree of Northerne Latitude, If the said River doth extend soe farr northwards. But if the said River shall not extend soe farr northward. then by the said River soe farr as it doth extend, and from the Head of the said River, the Eastern-bounds are to be determined by a Meridian Line to bee drawne from the head of the said River unto the said Three and Fortieth degree; The said Lands {to} extend westward Five degrees in longitude to be computed from the said Eastern bounds, and the said Lands to be bounded on the north by the begining of the Three and Fortieth degree of northerne Latitude and on the South by a Circle drawne of {at}5 12 miles distance from Newcastle northwards6 and westwards, unto the begining of the Fortieth degree of northerne Latitude, and then by a streight line westwards to the limit of Longitude above mentioned7

Wee doe alsoe give and grant unto the said William Penn his heires and Assignes The free and undisturbed use and continuance in and passage into and out of all and singular Ports, Harbours, Bayes, Waters, Rivers, Isles and Inletts belonging unto and {or} leading to and from the Country or Islands aforesaid And all the Soyle, Lands, Feilds, woods, underwoods, mountaines, hills, Fenns, Isles , Lakes, Rivers, Waters, Rivuletts, Bayes, and Inletts scituate or being within or belonging unto the Limitts and bounds aforesaid together with the fishing of all sorts of Fish, whales {sturgeons} and all Royall and other Fishes in the Sea, Bayes, Inletts, waters, or Rivers within the premisses and the Fish therein taken And alsoe all veines Mines and Quarries as well discovered, as not discovered, of gold, silver ,gemms and other {pretious} stones and all other whatsoever bee it of stones, mettalls, or of any other thing or matter whatsoever found or to be found within the Country Isles or limitts aforesaid

And him the said

In Witnesse whereof We have caused these Our Letters to be made Patents, Witness Ourselfe at Westm1 the 4th day of March, In the three and Thirtieth yeare of Our Reigne, 1680/180 Pigott81

Note: Footnotes, edits and insertions from Richard P. Dunn and Mary Maples Dunn, "The Papers of William Penn", U. of PA Press, 1982

Clarifying punctuation and emphasis by George Ross Fisher

Political Parties, Absent and Unmentionable

|

| King George III |

BECAUSE America had recently revolted to rid itself of King George III, the Constitutional framers of 1787 sought to construct a government forever free from one-man rule. Inefficiency could be accepted but central dictatorial power, never. It is unrealistic however to expect a wind-up toy to keep working forever, and our Constitution creates the same worry. After two centuries, some chinks have appeared.

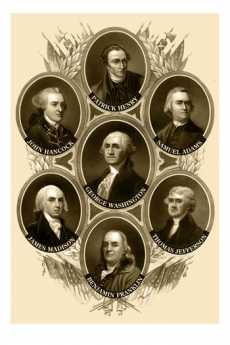

|

| Founding Fathers |

Political parties existed in 18th Century England and Europe, but the American founding fathers seem not to have worried about them much. Within ten years of Constitutional ratification, however, Thomas Jefferson had created a really partisan party which naturally provoked the creation of its partisan opposite. James Madison was slowly won over to the idea this was inevitable, but George Washington never budged. Although they were once firm friends, when Madison's partisan position became clear to him, Washington essentially never spoke to him again. Andrew Jackson, with the guidance of Martin van Buren, carried the partisan idea much further toward its modern characteristics, but it was the two Roosevelts who most fully tested the U.S. Supreme Court's tolerance for concentrating new powers in the Presidency, and Obama who recognized that the quickest way to strengthen the Presidency was to weaken the Legislative branch.

Dramatic episodes of this history are not central to present concerns, which focuses more on the largely unnoticed accumulations of small changes which bring us to our present position. Wars and economic crises induced several presidents, nearly as many Republicans as Democrats, to encourage migrations of power advantage which never quite returned to baseline after each crisis. Primary among these migrations was the erosion of the original assumption of perfect equality among individual members of Congress. A new member of Congress today may tell his constituents he will represent them ably, but when he arrives for work he is figuratively given an office in the basement and allowed to sit on empty packing cases. This is not accidental; the slights are intentional warnings from the true masters of power to bumptious new egotists, they will get nothing in their new environment unless they earn it. Not a bad idea? This schoolyard bullying is a very bad idea. If your elected representative is less powerful, you are less powerful.

|

| Houses of Congress |

Partisan politics begins with vote-swapping, evolves into a system of concentrating the votes of the members into the hands of party leaders, and ultimately creates the potential for declaring betrayal if the member votes his own mind in defiance of the leader. The rules of the "body" are adopted within moments of the first opening gavel, but they took centuries to evolve and will only significantly change direction on those few occasions when newcomers overpower the old-timers, and only then if some rebel among the old timers takes the considerable trouble to help organize them. In the vast majority of cases, after adoption, the opportunity to change the rules is then effectively lost for two years. Even the Senate, with six-year staggered terms, has argued that it is a "continuing body" and need not reconsider its rules except in the face of a serious uprising on some particular point. Both houses of Congress place great weight on seniority, for the very good purpose of training unfamiliar newcomers in obscure topics, and for the very bad purpose of concentrating power in "safe" districts where party leaders are able to exercise iron control of the nominating process. Those invisible bosses back home in the district, able to control nominations in safe districts, are the real powers in Congress. They indirectly control the offices and chairmanships which accumulate seniority in Congress; anyone who desires to control Congress must control the local political bosses, few of whom ever stand for election to any office if they can avoid it. In most states, the number of safe districts is a function of controlling the gerrymandering process, which takes place every ten years after a census. Therefore, in most states, it is possible to predict the politics of the whole state for a decade, by merely knowing the outcome of the redistricting. The rules for selecting members of the redistricting committee in the state legislatures are quite arcane and almost unbelievably subtle. An inquiring newsman who tries to compile a fifty-state table of the redistricting rules would spend several months doing it, and miss the essential points in a significant number of cases. The newspapers who attempt to pry out the facts of gerrymandering are easily gulled into the misleading belief that a good district is one which is round and compact, leading to a front-page picture showing all districts to be the same physical size. In fact, a good district is one where both parties have a reasonable chance to win, depending for a change, on the quality of their nominee.

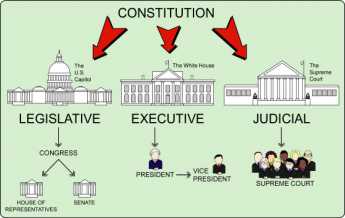

So that's how the "Will of Congress" is supposed to work, but the process recently has been far less commendable, and in fact, calls into dispute the whole idea of a balance of power between the three branches of government. We here concentrate on the Health Reform Bill ("Obamacare") and the Financial Reform Bill ("Dodd-Frank"), which send the same procedural message even though they differ widely in their central topic. At the moment, neither of these important pieces of legislation has been fully subject to judicial review, so the U.S. Supreme Court has not yet encumbered itself with stare decisis of its own creation.

|

| Three branches of government |

In both cases, bills of several thousand pages each were first written by persons who if not unknown, are largely unidentified. It is thus not yet possible to determine whether the authors were affiliated with the Executive Branch or the Legislative one; it is not even possible to be sure they were either elected or appointed to their positions. From all appearances, however, they met and organized their work fairly exclusively within the oversight of the Executive Branch. Some weighty members of the majority party in Congress must have had some involvement, but it seems a near certainty that no members of the minority party were included, and even comparatively few members of highly contested districts, the so-called "Blue Dogs" of the majority party. It seems safe to conjecture that a substantial number either represent special interest affiliates or else party faithful from safe districts with seniority. The construction of the massive legislation was conducted in such secrecy that even the sympathetic members of the press were excluded, and it would not be surprising to learn that no person alive had read the whole bill carefully before it was "sent" to Congress. It's fair to surmise that no member of Congress except a few limited members of the power elite of the majority party were allowed to read more than scattered fragments of the pending legislation in time to make meaningful changes.