Related Topics

Government Organization

Government Organization

Shaping the Constitution in Philadelphia

After Independence, the weakness of the Federal government dismayed a band of ardent patriots, so under Washington's leadership a stronger Constitution was written. Almost immediately, comrades discovered they had wanted the same thing for different reasons, so during the formative period they struggled to reshape future directions . Moving the Capitol from Philadelphia to the Potomac proved curiously central to all this.

Philadelphia Legal

Legal Philadelphia is full of crooks, but some lawyers are saints.

Right Angle Club 2011

As long as there is anything to say about Philadelphia, the Right Angle Club will search it out, and say it.

Unwritten Constitutional Modification

It is so difficult to amend the Constitution, we mostly don't do it. Our system is to have the Supreme Court migrate slowly through several small adjustments, watching the country respond. Occasionally we have imported new principles, sometimes not entirely wise ones, adopted without the same seasoning.

Corporations: Property, but also Immortal Persons

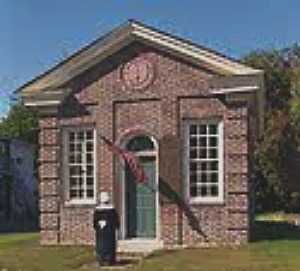

|

| Proprietor House |

The Proprietorship of West Jersey is the oldest stockholder corporation in America. Devised by William Penn it has been doing business in Burlington, New Jersey since 1676. The Proprietorship of East Jersey may possibly have been created slightly earlier by William Penn, but recently dissolved itself, thus leaving a clear path for West Jersey to claim to be the oldest. For a hundred years before 1776, corporations were devised by the King through royal charters, and for a century after 1776, most state legislatures passed individual laws to create each corporation, one by one. Consequently, there were a great many variations in the powers and scope of older corporations, with a heavy emphasis on the purpose to which the business was limited. Eventually, so many corporations were created that a body of law called the Uniform Law of Corporations simplified the task of incorporation for the legislatures. The Proprietorships of East and West Jersey would now probably be described as real estate investment trusts (REIT), but the Uniform laws now tend to diminish the emphasis on corporate purpose. It is now common to have a corporation proclaim the ability "to do whatever it is legal to do."

Many voices have been raised in opposition to corporations, largely claiming unfairness for a large and established corporation to compete with newcomers, especially small newcomers striving for the same line of business. Because of its immortality, a stockholder corporation can achieve dominance no individual could hope for, while because of its multi-stockholder ownership, it can generally raise larger amounts of capital. Moreover, because of its size and durability, a corporation can become more efficient and offer the public lower prices and higher quality. As much as anything else, a corporation can generally hire more employees and pay them higher wages; as even the unions admit, corporations create jobs, jobs, jobs. No doubt, state legislatures are attracted by the tax revenue derived from major corporations, but the quickest way to stimulate the economy has repeatedly been found to grow out of lowering corporate taxes. Since there is scarcely any purpose of creating a for-profit corporation unless it eventually pays its stockholders some kind of dividend, all corporation taxes have the handicap of double-taxation for a fixed amount of business. The Republic of Ireland recently lowered its corporate tax rate severely and triggered so much new corporate activity that it inflated and destabilized its whole economy. The result was a dangerous economic crisis, but politicians privately and world-wide silently derived only one real conclusion: lower your corporate taxes if you are looking to stimulate jobs, jobs, jobs.

The corporate model of business thus looks pretty safe, in spite of envious criticism, and is what most people mean when they speak of capitalism. The Constitution had the intention of extracting Interstate Commerce for the Federal Government and leaving the regulation of every other business to state legislatures. The Roosevelt Supreme Court-Packing dispute of 1936 twisted the meaning of Interstate Commerce to mean almost all commerce, but Congress wasted no time specifically exempting the "Business of Insurance" from federal regulation and returning it to the state legislatures in the 1945 McCarran-Fergusson Act. Although the matter remains one of some dispute, it is roughly correct to say that all commerce is federally regulated, except insurance. The corporation is nevertheless usually a creation of some legislature, and legislators have wide latitude in regulating them. To illustrate, in the early days of a banking corporation, the Bank of Hartford was delayed in receiving incorporation by the strong legislative suggestion that a closed stockholder list would result in refusal to incorporate them, whereas opening up the list to new stockholders might result in rapid approval. The implication was strong: the legislators wanted some cheap or free stock as a condition of incorporation. The following year, 250 banks were incorporated, and the year after that, over 400 more. Making of incorporation applicants by politicians was sharpened to a fine point in Pennsylvania in the late 19th Century, when legislatures accorded monopoly status to public utility corporations, withholding it from competitors. It is now a textbook statement that the funding of substantially all municipal political machines is derived from voluntary contributions by utilities with politically granted monopolies, who are consequently indifferent to the retail prices of their products.

So there is still room for public concern and vigilance, and both the courts and the Constitution protect but restrain corporations. In the early 19th Century when public opinion was becoming firmer about incorporation, it was contended they should be treated as persons, possibly resembling real persons more closely by imposing a finite life span on their charters. Although corporation entities are still to some degree treated like individuals, the legal doctrine prevailed that they are in fact contracts between the state and the stockholders. The paradox is thus defended that although legislatures can create corporations, they cannot dissolve them! After all, a contract is an agreement between two parties, and it requires both parties to agree to dissolve the agreement. And then, the final uncertainty was removed by John Marshall. The U.S. Supreme Court in the Dartmouth College case applied Article I, section 10 of the Constitution. That section provides that state governments may not pass any law impairing the obligation of contracts. The Supreme Court decision written by Marshall made it clear that this provision of Constitution eliminated any distinctiveness between a contract involving a state and a contract involving two citizens. There had been a growing feeling that private property was not to be disturbed by state power, and this linkage to Article 1 affirmed that point and finally settled matters. Shares of company stock were property, protected from state legislatures as belonging to the owner and not to the state in any sense. All the while that this quality of the property was established, certain features of the corporation as a person endured. Most of the attention to this point arose after the Civil War when the mixture of concepts ( a slave was a person who was also private property) more or less applied to the institution of slavery as well. More recently, potential muddles have been created by limiting campaign contributions of corporations, thus impairing their right to free speech in the role of a person. It even appears to be true that some of the 1886 precedents were created by an error of a court reporter. The dominant precedent in operation here would appear to a layman as, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." Additional centuries including a Civil War thus encrusted conditions and traditions onto the hybrid idea of a corporation which now allows it to stand on its own feet, more or less free at last.

The legal profession can certainly be congratulated for constructing two institutions which include the majority of working Americans -- the corporation and the civil service -- without the slightest mention of either one in the Constitution. Although everything seems to be reasonably comfortable, and no one is actively proposing substitutes, it is uncomfortable to hear so much dissension about the original intent of the Framers, when so much of American Law traces its history to events and institutions which the Framers never imagined. Constitutional Law, both within and without original intent, will soon be dwarfed in effect by non-constitutional accretions to it. Sooner or later, the advocates of some undefined cause could find it in their interest to challenge the Judicial system for what has been allowed to happen. Expediency has triumphed. We started with nothing but the common law (defined as law created by judicial decision), and we are slowly returning to that condition under a different name, misleadingly called statutes.

Originally published: Wednesday, August 31, 2011; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 15, 2019