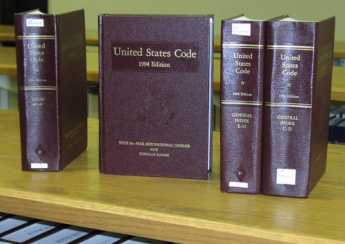

4 Volumes

Constitutional Era

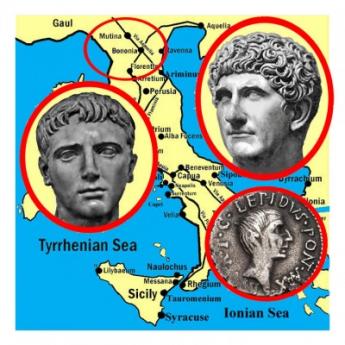

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

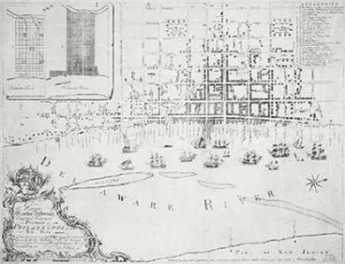

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Worldwide Common Currency and Corporate Headquarters

The Death of Money

Government Organization

Government Organization

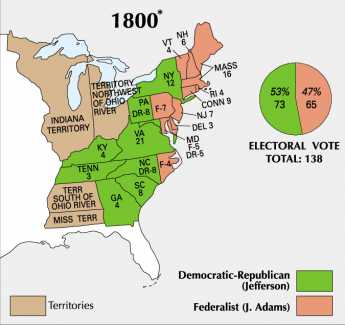

Democracy Turns Out To Be a Two-Party System

|

| American two-party system |

America's two-party system took fifty years to stumble into permanence. Regardless of the happenstances of their eventual emergence, political parties were clearly not designed into the original plan. Those few founding fathers who did think about political parties rejected them as "factionalism", something to be condemned. The true nature and advantages of a two-party system began to be truly venerated when other nations tried something quite different, which we now call Proportional Representation. PR is a fairly natural outgrowth of creating a large democracy from a collection of little tribes -- then creating surrogate political parties for them as part of the design. Guided by historical experience, it is now possible to ignore all minor differences between stable two-party democracy and multi-party democracy, except one. In a two-party system, the political dealing and vote-swapping takes place before the election, with all the players jockeying and sacrificing principle to answer a single candidate question, "Can he win?" By contrast, in a multi-party or proportionally-represented democracy, the election comes first, and only subsequently do vote-swapping and artful promises construct the ticket of candidates and the policy platform. The plain fact is the public doesn't know whom it is voting for and often is disagreeably surprised. Furthermore, important matters remain unsettled by a multi-party election. A cabinet member of a splinter party, potentially one with negligible public support, retains the threat of resigning if things don't go his way, and his resignation may trigger a whole new national election if it breaks up the political margin of the ruling coalition. At least, a two-party system settles things for a while and gives the public a relative rest from factional tensions.

The American system has evolved into a universal conviction, stronger than any Constitution, that two parties are quite enough. Third parties are of course tolerated because they aren't forbidden, but most offer a mechanism in case there is a serious wish to reconstitute one of the two major parties. The strength of third parties is to discipline the leadership of the major parties; the weakness is they threaten the unifying principle of compromise-in-order-to win. Nothing except religious fanaticism would likely induce any ambitious American politician to remain within a third party, fruitlessly frittering away his life's chances. Because of 18th Century history more than wisdom, an "established" religion is constitutionally prohibited in America; observation of the turmoils in other nations, and perhaps wisdom also, keep it that way.

If two parties are then quite enough, is it possible only one would be better? The quickest look abroad, the briefest exposure to history, shows a one-party system is synonymous with dictatorship. Communism and fascism had only this one feature in common; in fact, China seems to be morphing from one to the other, while resolutely retaining its single ruling-party system. The paradox of this situation is that it leads to the American realization that maintaining a two-party system means that neither party must ever achieve total victory. After each national election, the electorate settles back with relief that one side won, but neither side conquered. Even academics are muffled by the system; with much to criticize, there is nothing else worth substituting.

There is one thing left to mention about the two-party system, which is that the interests and affiliations which arouse the club-like loyalties of party members seldom perfectly match the party's current campaign policy issues, and depend in a high degree on habit and a formless sense of group comfort. Any schoolchild can notice, although the party candidates avoid mentioning, that policy issues move back and forth between the two parties. Whether it is tariffs, public schooling, the gold standard or a thousand other matters, the issues repeatedly shift to the other party when lack of progress or apparent betrayal offends them. The special interests seek to use the parties, and the parties regard each special interest as a bargaining chip; the gut feelings of the party membership adjust far more slowly. For maximum effectiveness, a two-party system needs the public to see itself as two warring affinity groups; for a while, polarization seemed to revolve around the rich and the poor. There would always be more poor people than rich ones, as the Founding Fathers feared and the anti-Federalists sought to exploit; but now Populism can only be sustained by continuous massive immigration. The times are growing stale for the Republicans to suggest that only they have an electoral incentive to eliminate poverty, while the Democrats would secretly like to increase it. Or for the Democrats to imply they have a monopoly of sympathy for the poor. Compared with the status of the rest of the world, permanent lifetime poverty in America is growing too infrequent to dominate elections, even supplemented by fear of poverty, a recollection of having once been poor, or guiltiness about never being poor. It is difficult to maintain the firmness of party members with such vague attitudes for abstruse legislative policies like banking reform or compulsory health insurance. Therefore, the search is on for large social affiliations which would more comfortably enlist loyalties for pressing specific legislative actions. At the present time, division of the working populace into the public and private sectors is being promoted as a bedrock political affiliation, but it is questionable whether that will be as successful as the public sector unions seem to hope for. Only twice in our history, during the administrations of George Washington and James Monroe, have Americans overwhelmingly agreed on core issues of religion, foreign policy, and prospects for the future. During both episodes, political parties virtually disappeared.

Term Limits, With Exceptions

|

Because of precision gerrymandering with computers, congressional incumbents now face very few serious re-election contests. Left with only a few seats in serious contention at each election, the public is dissatisfied by this reduced level of control but does not know how to strengthen it. Turning to the courts, for better rules, probably won't help. Once you fix the number of seats in Congress, give at least one seat to each state, and insist that geographically contiguous districts within a state should all contain the same number of inhabitants, there isn't much wiggle room. That's what then creates the rather strange connection between restraining gerrymandering, and imposing term limits.

Long-term incumbents in a legislative body maintain its institutional memory; their experience is a valuable thing, and recognized gifted veterans should be retained. Although a dozen states have even willingly sacrificed such advantages by imposing term limitations anyway, no one contends that all long-term incumbents are bad. We just have too many of them. The nominating process favors extremists, and they have crowded out the legislators from close districts who must be constantly mindful of current public opinion. Legislative bodies need to have a better balance between the two kinds.

So here's a proposal. Go ahead and impose a reasonable term limit, perhaps eight years. But then allow exceptions for districts which can demonstrate a plausible amount of bipartisanship. If the district in its last election had elected a governor or president of the opposite party from the incumbent congressman, or if one Senator in the state is of the opposite party, these might be reasonable grounds for permitting a district to keep re-electing its incumbent congressman. That might not be enough; perhaps a district should demonstrate two of those proofs of bipartisan spirit. But this would be a start. And a warning.

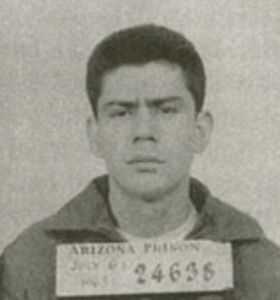

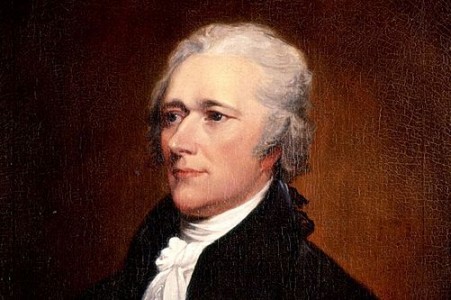

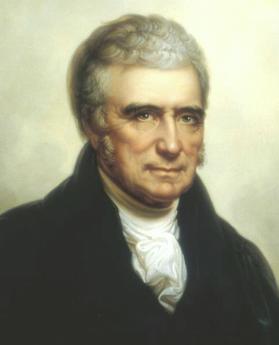

Mister Roberts

|

| Fidelity Building |

The Fidelity Building on Broad Street, now bearing the name of a successor bank, has its own ZIP code. It houses bank offices in one of its two towers and a general office building in the other. The top floor, the 29th, was originally the executive suite of the bank, with executive dining rooms, and lesser dining rooms where big deals were dealt. As an economy move, the executive floor eventually became a mid-day luncheon club, and right now it houses the law library of Montgomery, McCracken, and Rhoads. It carries the name of the law firm's most famous partner, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Owen Roberts. In the center of the hushed library, a single volume sits on a table, held in place by two very heavy bookends. It's the bound 1955 volume of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, with a small green tab attached where a hundred pages of testimonials to Roberts are found. The tabbed page itself begins an essay by Felix Frankfurter, written in prose so elegant it seems like poetry. His topic is the mind of Justice Roberts at the time he switched sides in the 1936 Roosevelt Supreme Court packing episode, the famous "switch in time, which saved Nine."

Frankfurter and Roberts sat on the Supreme Court together for years, but the events in question took place before Frankfurter was appointed. Like the rest of us he has to conjecture what was in Roberts' mind. Felix Frankfurter offers two pieces of special evidence, his long personal observation of Roberts' character, and a private memo. Roberts had written in the memo that he had been ready to switch for Roosevelt before the court-packing proposal was made, but held off taking the step for several months because Justice Harlan Stone was absent for medical reasons. Stone, later elevated by Roosevelt to Chief Justice, was known to favor Roosevelt's New Deal proposals, particularly the Minimum Wage, which were central to the Constitutional question: whether the federal government had a right to go beyond regulating interstate commerce, to regulating all commerce. Frankfurter concludes that Roberts did not make the switch in response to Roosevelt's threats, because he had already decided to act before the threat was made to enlarge the court until it contained a majority in favor. Not only had Roberts decided to switch before the Presidential threat was made, but he also proved to be a courageous and highly moral person throughout the later years when he and Frankfurter were closely associated.

|

| Frank Furter |

Unfortunately, Frankfurter's 1955 eulogy has not convinced historical opinion. After all, there were dozens of people on the inside of the Supreme Court and the Presidential Administration who knew Roberts better than Frankfurter did and probably talked about nothing else for weeks. Up until the fateful decision, almost all of Roberts' close friends had been on the other side of the issue and felt entitled to some sort of explanation if not an apology. Washington is simply crawling with reporters whose job it is to search out gossip and hearsay. When an opinion emerges from such a cauldron and survives for seventy years, it has substance. The prevailing view is that Roberts felt the Judicial Branch of government was in jeopardy, and that someone must sacrifice himself in the crisis. Roosevelt had just been re-elected in a landslide, the new Congress would surely do anything he asked, the nation was in the depths of a horrendous economic depression for which Roosevelt was proposing the only conceivable Keynsean solution of increasing national liquidity through government spending. Roberts knew he would become a political pariah, but his duty seemed clear to him. It is merely a matter of phrasing whether his position was described as knuckling under to Roosevelts's threats, or throwing his body over Roosevelt's hand grenade.

With seventy years of retrospect, it all seems so pitiful. Public opinion and congressional action was in fact outraged at

|

| Franklin Roosevelt |

Roosevelt, landslide or no landslide. Roberts and Stone had no need to do what Roosevelt asked. Any class in economics today can marshal a respectable argument against the wisdom of minimum wage laws, every class in law school is amazed and mostly appalled by their fresh reading of the Constitution's prohibition against Congress acting outside the limits of "commerce between the several states". On the level of governments rescuing their countries from depression by expanding liquidity, the experience has been that tax cuts usually succeed in that, while government spending usually does not. Paradoxically, the one principle to survive respectably from the 1936 political revolution was the movement toward national standards for internal trade and commerce, away from Balkanization. That's too big a step to take without public debate, perhaps, and highly disruptive if it's done in a single step. But the general idea is probably a sound one.

Poor Roberts probably never even considered that aspect. He was overwhelmed in his role as a Greek tragic hero, pursuing tragic inevitability.

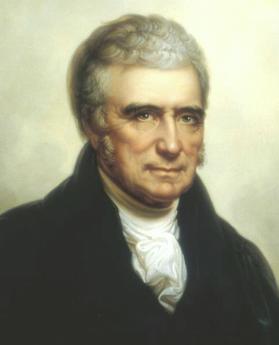

Rosencrantz and Gildenstern (4)

|

| Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead |

A few Broadway seasons ago, Tom Stoppard's play and movie Rosencrantz and Guildenstern have Dead described an experience, resonating with the early years of the Reagan presidential administration. If you are a small witness to palace politics, you mostly have no clue about what is actually happening. At that time, it was widely accepted among Washington gossips that the appointees who filled the Executive Office Building belonged to three hostile tribes in temporary alliance, and the Libertarian tribe was cast out. According to this recounting, the other two tribes were the Religious Right and the Win-at-any-cost California political professionals. A more mature view of it might be that all administrations of all parties contain hard-noses who make a profession of the ruthless winning of elections. An ideological president can't win without hard-ball lieutenants, so although their presence is inevitable, what matters is how well they are controlled.

|

| David Stockman |

Ignoring these unattractive fixtures of political machinery, David Stockman seemed to symbolize a libertarian economic ideology within the Reagan White House, and Caspar Weinberger a militaristic one. When Stockman was sacrificed to power realities in Congress, the Libertarians followed the lead of William Niskanen and bitterly retreated to the neighborhood think tanks. But a few years later, Weinberger was similarly sacrificed over the Star Wars and Iran-Contra matters. These functionaries working at EOB thought they ran the country, but that most affable of men, Ronald Reagan, ran things. He seriously meant to discredit New Deal economics and to win the Cold War. To do so, he willingly sacrificed small improvements in our economic system like the Medical Savings Account, and minor enhancements of military hardware like the Strategic Defense Initiative. He would like to see these things succeed, but they would have to do it on their own, without cost to his political capital.

And so, in time, John McClaughry went back to Vermont, founded a think tank called the Ethan Allen Institute, ran unsuccessfully for governor against Howard Dean, and became Majority Leader in the Vermont Senate. Meanwhile, I devoted my efforts to selling the Medical Savings Account concept to that most reserved of audiences, the American Medical Association.

Commercial Academic Think Tank

|

| Stephen P. Mullin |

Stephen P. Mullin recently addressed the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia about assorted economic subjects; he is certainly qualified. He was once the only Republican in Mayor Rendell's cabinet, acting first as Finance Director and then as Commerce Director. At first, he doesn't appear extroverted enough to be a politician but quickly demonstrated that he knew the first names of more of the members of the club than the president did, so maybe he does have the innate talents of a politician. Urban political machines don't usually respond cordially to graduates of Exeter and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. A number of University professors are consultants to the firm, which offers statistical economic advice to the many law firms in town, to philanthropic organizations considering public-interest projects in the region, to government agencies faced with regulating unfamiliar activities, and very likely to anyone else willing to pay for the service of academics, statisticians and analysts. It certainly sounds like a service that governments and philanthropies need, and which the region needs to avail itself of. In a way, it is probably something the University needs, as well. A friend of mine is now retired, but at one time I commuted on the train with an academic administrator of the Wharton School, who was quite obviously disturbed by handing diplomas to students who promptly took jobs which paid those graduates more than he was paid himself. Obviously, such a system cannot persist very long without creating a brain drain, so income supplementation by commercial consulting is a necessary and valuable support for academics. There are, of course, probably some negative features as well.

|

| The Wharton School |

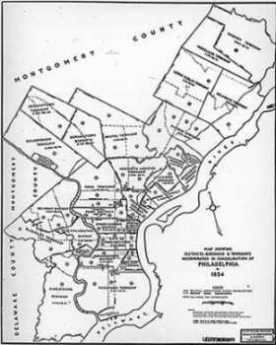

It is interesting to hear from Steve how Philadelphia can be variously described. We have, for example, significantly less foreign immigration than other cities. New York, by contrast, has net immigration of about 700,000 persons a year; such forces can quickly transform a city in a variety of ways. The bombing of West Philadelphia during the Goode Administration was news for a while, then vanished from the papers. But it had a shattering effect on Philadelphia commerce, leading to a period of 8 or 9 years when there was essentially no private investment in the city. Philadelphia indeed now needs to have its municipal bonds issued by the state bonding authority, because our own bond rating is so low the extra cost of municipal debt is a significant one. And there is the cost of invisible shifting of power to Harrisburg. An unexpected result is that sales and real estate transfer taxes escalated to make up for property taxes which they could not possibly be raised as much as inflation. Real estate was in big trouble; whether ingenious strategies like the 10-year tax abatement for a new property will be successful in rescuing the real estate industry, remains to be seen. New office towers have been built, but they drain off tenants from older office buildings. We're seeing a massive conversion of older office space into residential apartments, an apparently successful maneuver. But that drains the older residential areas, which leads to -- well, who knows what it will lead to, but it could be slums.

|

| Mayor Michael Nutter |

The traditional hostilities between Philadelphia and its neighbors can be defined in a new way, too. For a century, Philadelphia contributed more tax money to the rest of the state than it received in state services. But in the past 20 years, Philadelphia city has become a net importer of an annual billion dollars -- from the rest of the state. Two or three billion go to the schools, which the rest of the state regards as a deplorable waste in view of the quality of the product. And yet, the most hopeful feature of the situation is the vigor and ingenuity of the attempts being made to rescue the situation. In a certain sense, Mayor Nutter is the candidate of the Wharton School. He may well have some innovative ideas, and academic places like the Wharton School will surely suggest others. It remains to be seen whether Nutter can combine idealism with sufficient ruthlessness to make the city function. Cynical oldtimers will grumble that a mayor has to employ a moderate amount of deception and corruption in order to accomplish his mission. Maybe that overstates things, but it is very certain he must be tough. He's dealing with construction unions who will certainly be tough, and whose interest in sacrificing their own agendas in order to help the schools or street crime -- always fairly small -- is even further impaired by the econometrics that 70% of them live in the suburbs. We wish our new mayor all the best, since he seems smart enough to know what needs to be done, and is definitely smart enough not to drop any bombs on houses. He's smart enough to see that extra city revenue derived from gambling might permit the lowering of wage taxes, and hence an urban business recovery. But is he tenacious enough to stay in office long enough to achieve the balanced result; or will the forces of evil simply kick him out of office before wage taxes can be lowered and gambling discontinued? He won't break his promises, but will they break them for him? Beyond being competent, a city mayor needs to be tougher than the convivial but very mean friends he needs to associate with. He must, for example, decline to run for national office, the traditional way that city machines rid themselves of pointy-headed reformers.

Volunteerism Needs a Business Plan

|

| Alexis de Tocqueville |

The visiting Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville was struck most by the volunteerism he found everywhere in the young American nation; in his view, the first reaction of 19th Century Americans to a problem was to create a volunteer organization to fix it. Benjamin Franklin, who created dozens of such initiatives, was held up as its great exemplar. But de Tocqueville visited us at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and we are now well past that into the Information Revolution; volunteerism has noticeably declined. Not only have the great volunteer organizations like the Masons and the Red Cross suffered, but it is far more difficult to enlist the help of others to form a pick-up group to attack some issue or other. It is in that sense the general spirit of volunteerism has declined. The likely difficulty is not selfishness, but the helplessness of people to control their own time.

When volunteer groups to assemble, they are mostly composed of self-employed people like plumbers and dentists, free to be somewhere else during "normal business hours", which although shorter than they once were, seem extended by commuting time and by chores pushed aside during workplace confinement. To some extent longer commuting distances make it physically impossible to do personal chores in the vicinity of the workplace. But constrained personal time is also related to increased control behavior by management. A successful big business has to employ strategies to get employees with cell phones to stick strictly to business while the employer is paying for their time. Now that so many women are going out to work, the family unit needs to struggle to coordinate everyone's work time so there will be some remaining opportunity to conduct family life. When a working couple shares the home tasks and babysitting, the preempted time now extends to two working partners, and what is left is called "quality time". A probably temporary elaboration of this time competition is the need to chauffeur teenagers to their resume-enhancing activities. For the time being, you don't pick a college, the college picks you, and parents desperately labor to assist their children on a career path. Quite obviously, America needs to evolve better ways of trading work at home for more flexibility in the actual workplace, and we also need to build more first-rate colleges, but those issues are not the present topic. To summarize: It's awfully hard to assemble a group of volunteers simultaneously because employers have so successfully assembled their time. Failing to appreciate the tradeoffs inherent in commuting time is a secondary but still important factor, somehow related to the recent housing/schools mania.

Consequently, volunteer organizations increasingly tend to regard their chores as something you hire someone else to do if it proves impossible to dump them on someone who is retired or unemployed, or too timid to refuse. Even nominal volunteers are reluctant to step forward. This leads to recruitment lectures along the line that naturally you must sacrifice if you really truly believe in the goals of the dear old Whatsis Association, surely just a coercive speech pattern. That claptrap was never heard during the age of universal volunteers; volunteering was just one of those things everyone expected to do to get community activities accomplished. We're losing something important if we continue to endorse this attitude. Sometime during the first twenty-four hours in military service, for example, someone will surely advise the new recruit -- never volunteer.

For a penniless non-profit to adopt the solution of hiring staff when there is no revenue stream to pay them, is the first step toward the dissolution of the organization. Essentially, the non-volunteers are ordered to contribute money if they choose to be draft-evaders, and eventually, the officers and staff begin to look back at the organization members as cows to be milked. A class of people who are only making a living is substituted for those who understand and promote the goals, and it just goes downhill from there.

Instead, all volunteers really must each do some unpaid work, and the officers and directors must set an example of it. What an organization does next is crucial. Individual members, either anonymous or hoping to remain anonymous, must be approached with the suggestion they accept responsibility for a task. The wild-eyed response to this approach is quite familiar, like the lame excuse that there is no time. A counter response that I'm busier than you are, does not improve the conversation because it suggests the refuser is merely a selfish shirker. Instead, initial requests must take the following form: They should be for a simple, limited task without any obligations stretching to infinity. Almost everyone will be glad to bake a cake for a party, but almost no one will agree to be chairman of the cake-baking department unless the boundaries of that commitment are more reliably limited than they usually are.

In modern times, any major undefined volunteer responsibility is seen as potentially leading to an unthinkable conflict with gainful employment or else its ill-considered outgrowths like commuting. Since that's the basic problem, all-volunteer invitations must respect the true issue and devise workable ways to circumvent it. Role models certainly help if you have any.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1448.htm

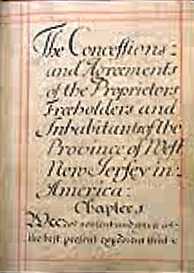

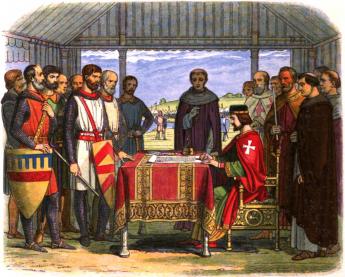

Concessions and Agreements

|

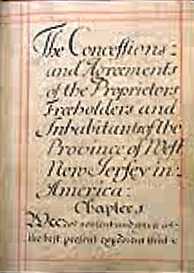

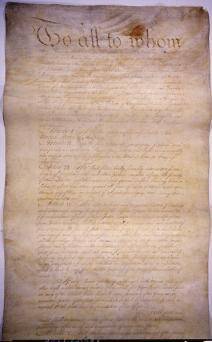

| Concessions and Agreements |

The United States Constitution is a unique achievement, but it had significant precursors, many of which James Madison had studied at Princeton. In the days of difficult ocean travel, almost all colonies were bound by an agreement to maintain loyalty to their European owners in spite of receiving latitude to govern themselves. Charters and documents defining these roles were generally written by the owners, and the colonists could pretty much take them or leave them. In the case of New Jersey in 1664, however, a very formidable lawyer and friend of the King named William Penn was drawing up agreements to his own conditions of sale, taking care that the grant of governing authority he received was favorable. Penn's relationship to the King was unusually good, to say the least. He had more reason to be wary of nit-pickers in the King's administration, trying to anticipate every conceivable disappointment for some successor King.

For his part, Penn wanted to make colonial land attractive to re-sell to religious groups who had experienced harsh government oppression; he wanted no obstacles to his announcing there would be no religious oppression in New Jersey. He was offered the role of sub-king although he hastily rejected any such title, and needed to repeat the formalities of the Charter to define his role and reassure his settlers about that matter. Furthermore, he was dealing with the heirs of Carteret and Berkeley, active participants in North and South Carolina. So Penn's method of achieving basic rights was influenced by prior thinking in the Carolinas, as the thinking of John Locke secondarily influenced matters in Delaware and Pennsylvania. These ideas were incorporated in a New Jersey document called "Concessions and Agreements." The concepts were not wholly the ideas of William Penn, but he did write it, and it does contain many ideas that were uniquely his. Understandings about limits were set down, argued about, and agreed to. The owner risked money, the colonist risked his life. Neither would agree unless a reasonable bargain was struck in advance of any dispute. Furthermore, the main value of a colony was beginning to shift from trading rights to real estate rights. Carteret and Berkeley had not only been principals in both the Carolinas and the Jerseys but had been involved in a number of such investments in Africa and the West Indies; New Jersey was just another business deal. It was conventional for documents of this type to define the method of selection of a governor, the establishment of an assembly of colonists, and some sort of council to attend to day to day affairs. In that era, few colonists would cross the ocean without a guarantee of religious freedom, at least for their own brand of religion. Standard clauses which may sound strange in today's real estate world, were then necessary because it was a transfer of not merely land, but also the terms of government. In the case of the Quaker colonies, many of these stipulations were included in the earlier charter from the King. It seems very likely that Penn hovered around and negotiated these points which he wished to have the King agree to; and then once the land was safely his, Penn repeated and expanded these stipulations with the colonists in his Concessions and Agreements . It wasn't exactly a Constitution, but it reads a lot like the one America adopted a century later.

|

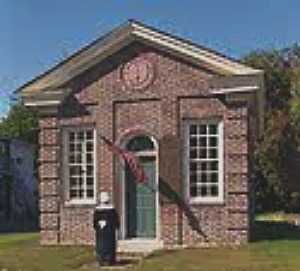

| Proprietors House |

Quakers had suffered persecution and imprisonment, and knew exactly what they feared; on the other side, it seems likely Carteret and Berkeley were less interested. So this real estate transfer document conceded almost anything the colonists wanted and the King would stand for, couched in conciliatory phrases. For example, no settler was to be molested for his conscience, and liberty was to be for all time, and for all men and Christians. Elections, by the way, must be annual, and by secret ballot. While law and order must prevail, nevertheless no man is to be imprisoned or molested except by the agreement of twelve men of the neighborhood. On the matter of slavery, no man was to be brought to the colony in bondage, save by his own consent (that is, indentured servants were to be permitted). And in what proved to be a final irony for William Penn, there was to be no imprisonment for debt. Almost all of these innovative ideas survived into the U.S. Constitution a century later, but the most innovative idea of all was to set them all down in a freely-made agreement in writing. This was not merely how a government was organized, it defined the set of conditions under which both sides agreed it would operate.

It was, of course, more than that. It was a set of reassurances to settlers who had been in New Jersey before the English arrived that they, also, would be treated as equals. It was a real estate advertisement to the fearful religious dissenters back in England that it was safe to live here. And it was a reminder to future Kings and Parliaments that this is what they had promised.

The pity and a warning, is that the larger vision of a whole continent governed fairly by common consent may have been too grandiose for a little band of New Jersey Quakers, surrounded as they were by an uncomprehending world. All utopias are helpless when stronger neighbors reject the basic premise. However, it was the expansion of the pacifist concept to the much larger neighboring territory of Pennsylvania that proved to be just too much for such a small group of friends to manage by consensus, particularly when unbelieving immigrants began to outnumber them. But the essential parts of it certainly remained in the minds of delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. When the minutes of the Constitutional Convention speak of the "New Jersey Plan", the Concessions and Agreements was what they had in mind.

REFERENCES

| Concessions and Agreements of New Jersey 1676: William Penn | New Jersey State Library |

| Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City: Howard Gillette Jr.: ISBN-13: 978-0812219685 | Amazon |

Vote Counting, Past and Future

|

| Greg Harvey |

The Right Angle Club was recently fascinated to hear Greg Harvey, a Montgomery McCracken expert on election laws, discuss the snarled Florida situation in the 2000 Presidential race, and the prospects for similar problems in upcoming elections. With the aid of retrospect, candidate Al Gore deserves much of the blame for his own loss, and the U.S. Supreme Court does seem to have terminated the uproar without affecting the final result.

A consortium of major newspapers funded an extensive investigation of the Florida election and were forced to agree that George W. Bush would probably have won that election no matter what. The central issue in these contests is the 35-day time limit to contesting elections. It is true that right or wrong, the country needs to settle its elections promptly and get on with its business. Furthermore, if a national election is so close that it takes months to decide the winner, there can't be a great deal of difference between the candidates, so who cares.

|

| Al Gore |

Looking back at the 2000 election with the leisure of time and appreciable resources, it is possible to see that Al Gore might have won that election if he had made several lucky choices in contesting its result. But it seems highly unlikely that anyone in his position would have been able to identify the winning combination of choices -- within the 35 day time allowed for pursuing them. He had to guess that ballots with two candidates marked ("over balloting") would pick up more Gore votes than ballots without an indicated choice ("under balloting"); he guessed wrong. He had to decide whether challenging late ballots from absentee military was worth the unpopularity of pursuing such a technicality to the disadvantage of soldiers serving overseas. His ticket-mate Joe Lieberman urged him to avoid that touchy issue which did prove to cost him some votes he needed. The decision was one to be proud of but is the main reason why his party faithfuls later turned rather viciously against Lieberman. A second wrong guess was to fail to go after the software mixup on invalidating the ballots of convicted felons. He might have picked up a couple of thousand votes, but only if willing to have the world learn that convicted felons are overwhelmingly pro-Democratic voters. The one decision he made that makes him look rather sappy to professional pols was to challenge ballots in the districts where he was already very popular.

|

| Vote |

Vote counters and poll watchers tend to be strong political partisans, usually drawn from the local district. When votes are ambiguous, these people lean in the direction of their party. Therefore, most party insiders would know immediately; if you challenge districts, challenge the districts which favor your opponent. Choices like this do have to be made. The thirty-five-day rule makes a challenger run out of enough time to look elsewhere if early guesses prove wrong. So, although it is possible in retrospect to construct for Gore a winning strategy for selective challenges, the newspaper consortium and the Supreme Court which pondered the choices before him rightly concluded he was destined to lose.

|

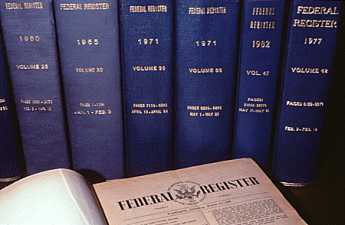

| HAVA |

Some of these lessons are enduring ones, but future elections face unexplored difficulties. A new election law (the Help America Vote Act, or "HAVA") sought to reform the election system by prohibiting the use of punch card ballots, requiring states to use auditable vote records and provisional ballots in doubtful cases, stricter voter identification methods, and statewide voter registration databases. In response to these record requirements, many states opted for complicated data in code, sequence-scrambled to prevent individual identification. In the event of a challenge, however, deciphering these records will be time-consuming, and the potential is created for the candidate who is initially ahead to stretch out the process until the challenge effort collapses at the 35-day time limit.

Several states, including Ohio, are thought to have the potential for very close 2008 results. In that particular state there are some complicated rules about voting in the "wrong" district, that is, to be registered in one district, but attempting to vote in another. It would not seem difficult to do a little of this on purpose, either as a voter, or an election registrar. It seems unlikely that very much challenge among the three possible culprits could be accomplished within thirty-five days of a contested election. So the challenger in Ohio would be faced with the same sort of impossible snap decisions that faced poor old Al Gore, surrounded by excited partisans shouting at the top of their voices.

So perhaps Greg Harvey's law school classmate Appellate Judge Richard Posner has a sustainable position on this. It was his judgment that the 2000 election was essentially a tie. Letting the Supreme Court decide it wasn't the worst possible choice.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1515.htm

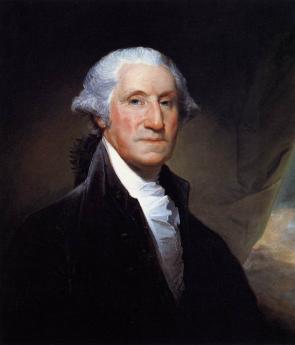

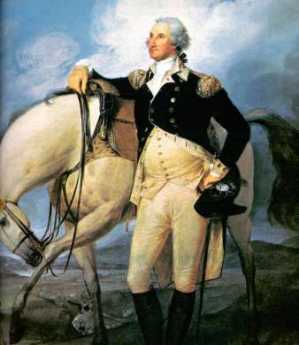

George Washington Demands a Better Constitution

GEORGE Washington was a far more complex person than most people suppose, and he wanted it that way. He was born to be a tall imposing athlete, eventually a bold and dashing soldier. On top of that framework, he carefully constructed a public image of himself as aloof, selfless, inflexibly committed to keeping his word. Parson Weems the biographer may have overdone the image a little, but Washington gave Weems plenty to work with and undoubtedly would have enjoyed overhearing the stories of the cherry tree and tossing the coin across an impossibly wide Potomac. Washington had a bad temper and could remember a grievance for life. He married up, to the richest woman in Virginia.

|

| Potomac River |

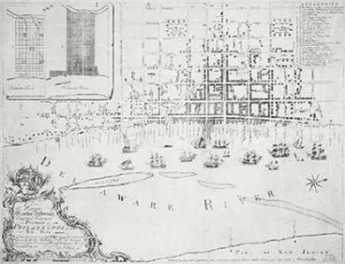

Growing up along the wide Potomac River, Washington early conceived a life-long ambition to convert the Potomac into America's main highway to the Mississippi. He did indeed live to watch the nation's new capital start to move into the Potomac swamps across from his Mount Vernon mansion, in a city named for him. For now, retiring from military command with great fanfare and farewells after the Revolution, he returned to private life on this Virginia farm. He made an important political mistake along this path, by vowing in public never to return to public life. During the years after the Revolution but before the new Constitution, his attention quickly returned to building canals along the Potomac River, deepening it for transportation, and connecting its headwaters over a portage in Pennsylvania to the headwaters of the Monongahela River -- hence to the Ohio, then the Mississippi, or up the Allegheny River to the Great Lakes. He personally owned 40,000 acres along this river path to the center of North America. The occasion for a national constitutional convention grew out of a meeting with Maryland to reach an agreement about this Potomac vision, which was being blocked by commercial interests in Baltimore. Ultimately, Baltimore won the commercial race; so it was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad which captured the early commerce to the west. Washington also made deals, ultimately to Baltimore's benefit, with the James River interests, to give them a share of the development of the Chesapeake Bay trade. As a young man, George Washington had acted as a surveyor for most of this region, and as a young soldier had explored the Indian trade to Pittsburgh, actually starting the French and Indian War during this trip. He was to march it again later with Braddock's army. All the while, Washington dreamed of the day. There were competitors; Philadelphia and New York had similar aspirations for their rivers. Take a look at a globe or Google Earth. Comparatively few of the earth's rivers drain too far western beaches. Even today, long-term victory in worldwide water transportation will likely go to one of many eastern rivers linking up with one of the few western ones. The ultimate world-wide goal has yet to be fulfilled for what continues to be the cheapest of all bulk transportation methods.

Washington at age 54 was already richer than most people need to be; a lot of this Potomac dream was a residual of boyhood ambitions enduring into middle age. In a sense, he had the ambition to make his boyhood home the future center of the universe. Although much of his stock in these real estate enterprises resulted in very little extra wealth, he demonstrated his mixture of public spirit combined with ambition by donating the stock in one of the companies to a future national university, to be located across the river near Georgetown. Since that didn't work out, he later placed the nation's capital there. He had consistently been a far bolder dreamer than Cincinnatus, humble Roman citizen-soldier returning to his farm from the wars.

Washington more or less gave up this Potomac ambition for a loftier one. During the Revolution, he had suffered the most infuriating abuse of himself and his soldiers from the state legislatures. Their urgent demands for victories were seldom matched with resources. The Continental Congress representing those state governments in a weak confederation that could not feed and pay its own troops seemed little better. He could be a mean man to cross, but perhaps with General Cromwell in mind, Washington possessed the firmest and most sincere belief in the proper subservience of military to civilian control. These conflicting feelings resulted in earnest obedience to a group of politicians he surely distrusted. This could not be described as hypocrisy; he respected their rank even though he suffered from their behavior. When Congress paid the troops in worthless currency which they promised to redeem after the war, it became clear that either lack of moral fiber or their system of governance led the states and the Congress in the direction of dishonoring their debt to the soldiers. This was a dreadful system, which led to death and suffering among the loyal troops, forcing the General into the humiliating position of assuring the troops Congress would stand by them, while he privately doubted any chance of it. Washington did not easily forgive or forget. Here was a paltry outcome for eight years of war and suffering; this system of organized dishonor must be improved.

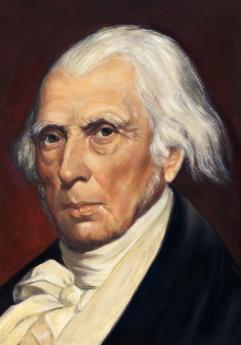

He went about achieving his goal in a way that would not occur to most people. He chose a young ambitious agent, James Madison, who had caught his attention in the Virginia legislature, in the Continental Congress, and in the negotiations with Maryland over the development of the Potomac. Washington schemed with the young man for weeks on end about ways and means, opportunities, dangers, and potential enemies. Perhaps he failed to notice some ways where he and Madison fundamentally differed. Madison himself might not have recognized that his years at Princeton in the Quaker state of New Jersey had exposed him to novel ideas like separation of church and state, which were instantly appealing to the two Virginia Episcopalian religious doubters. Many people he admired, Patrick Henry, in particular, wanted the government to be as weak and ineffective as possible. Unfortunately, when Madison's turn later came for assuming the Presidency, he went along with reliance on diplomacy and persuasion until it almost cost America the War of 1812. Acting as Washington's agent in 1788, Madison was assigned to win over the Virginia legislature, make alliances with other states in Congress, identify friends and enemies, make deals. He performed as brilliantly as he would at the Constitutional Convention, so the basic conflict between the soldier President and his politician assistant was glossed over. As long as the original relationship held together, Washington felt it was useful to remain above and aloof, publicly wavering whether this was all a good idea, but fiercely determined to have a nation he could be proud of. There was to be a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, but while Washington was invited, he let it be known he was uncertain whether he should accept the invitation. What he really meant was he would preserve his political credibility for a different approach if this one failed. Considered from Madison's viewpoint however, this clearly meant Washington would dump him if things went badly. Meanwhile, the unknown young Madison on several occasions came to Mount Vernon for three days at a time to talk strategy and give the famous General all the scoop. Today, we would describe Madison as a nerd. The aristocratic Gouverneur Morris never thought much of him. Washington needed him, but there is no evidence he thought of him other than as a glorified butler. Little Madison was awkward among the ladies, a problem inconceivable to either Washington or Morris. But that little mind was surely working, all the time.

Madison was in fact a brilliant politician, a dissembler in a different way, but a severe contrast with his mentor. To begin with, he was a scholar. Both as an undergraduate at Princeton and a graduate student working directly with the great Witherspoon himself, Madison was deeply learned in the history of classical republics. He spent an extra year at Princeton, just to be able to study ancient Hebrew with Witherspoon. But he was innately skilled in the darker arts of politics. When votes were needed, he had a way of persuading three or four other members to vote for a measure, while Madison himself would then vote against it to preserve influence with opponents for later skirmishes. In fact, as matters later turned out, it becomes a little uncertain just how convinced Madison was that Washington's strong central government was a totally good idea. Before and after 1787 Madison expressed a conviction that real sovereignty originated in the states, just as the Articles declared. That was a little too fancy for practical men of affairs, who were uncomfortable to discover how literal Madison was after his break with the Federalists. Twenty years younger than the General. he prospered in the image of being personally close to the titan, and he certainly enjoyed the game of politics. The new Constitution was going to be an improvement over the Articles of Confederation, but Madison did not burn for long with indignation about injustice to the troops, or disdain for nasty little politicians in the state legislatures. These were problems to be solved, not offenses to be punished. The new Constitution was a project where he could advance his career, skillfully demonstrating his prowess at negotiation and manipulation. This is not to say he did not believe in his project, but rather to suspect that he was a blank slate on which he allowed Washington to write, and later allowed others to over-write. He was eventually to modify his opinions as a result of new associations and partners, and since he succeeded Jefferson as President, it was personally useful to adjust his viewpoints to his timing. What would never change was that he was an artful politician, while Washington hated, absolutely hated, partisan politics.

This is not just an emotional division between two particular Virginia plantation owners, but an enduring thread running through all elective politics. Washington set the style for generations of citizen leaders in America. In his mind, a person of honor distinguishes himself in some way before he enters public office, so on the basis of that honorable image, presents himself to voters for public office, and naturally is elected to represent their interests. He is expected to compromise where compromise is honorable and publicly acknowledged, in order to achieve one desirable outcome in concert with other outcomes, in some ways inconsistent but still honorable in combination. He reliably will not vote for either issues or candidates in return for some personal consideration other than the worth of the issue or the candidate, with the possible exception of yielding to the clear preferences of his local district. Such a person is not a member of a political organization very long before he encounters another group of colleagues -- who regularly swap votes for personal advantage, join a group who agree to vote as a unit no matter what the merits, and recognize the frequent necessity to talk one way while secretly voting another. The first sort of politician is usually an amateur, the second type is typically a professional politician. Although it seems a violation of ethics and common public welfare, the fact is the professional vote-swapper almost always beats the sappy amateur. The response during the Eighteenth Century was for idealists to condemn and attempt to abolish partisanship and political parties. The American Constitution does not make provision for political parties and other forms of vote-swapping or even anticipate their emergence. Although Madison ignited the process in the United States, Jefferson really organized it; every recent politician except Adlai Stevenson has openly participated in a version of it. That the Constitution has still not been amended to provide for parties seems to reflect a persisting nostalgic hope that somehow we can return to Washington's stance.

Washington's conception of open representative politics was not entirely perfect, either. In order to maintain an image of impartiality, Washington and his imitators isolated themselves in a cloak, holding back their true opinions in a sphinx-like way that hampered negotiation. Unwillingness to be seen swapping votes can lead to an unwillingness to compromise, and in the final analysis, the difference is one of degree. However, the over-riding issue is that each representative or Senator is equal to every other one. When vote-swapping gets started, it leads to placing power over supposed equals in the hands of the more powerful manipulators, masquerading as political leaders. Ultimately, it leads to the adoption of house rules on the very first day of a session which force lesser members to surrender their votes to a speaker or minority leader or committee chairman, when the theory is that there is no such thing as a lesser member. The claim of a party-line politician is that he obeys the will of the party caucus; the reality is usually that he obeys the will of some tough, self-advancing party leader. The final reality is that most legislatures must now deal with thousands of bills per session, leading to the necessity of appointing someone to set priorities, which in turn leads to the power of party leaders over their grudging servants. These various subversions of the equal rights of elected representatives can lead to such discrediting of the system that honorable people may refuse to stand for office, leaving foxes in charge of the hen house. Benjamin Franklin, who was to play an invisibly controlling role in the impending Constitutional Convention, had his own way of coping with the political environment. "Never ask, never refuse, never resign."

American Succession

It may seem a startling focus for a famous war hero, but one of the most important precedents George Washington wanted to establish as America's first president, was that he was determined not to die while in office. His original intention was to serve only one four-year term as president, only accepting a second term with considerable concern that it would increase his chances of dying in office. His reasons are perhaps not totally clear since he repeatedly stated his concern that he had promised the American public that he would retire from public office when he resigned his commission as General and was determined to seem a man of his word. While this sounds a little off-key to modern ears, it must be remembered his resignation as General had caused an international stir, even prompting King George III to exclaim that this must be the greatest man who ever lived. Washington may have sincerely thought he was following the pattern of Cincinnatus, the Roman citizen soldier who declined further public life in order to return to his farm. But in retrospect we can see that for a thousand years before Washington's military resignation it was essentially unheard of for a leader with major power to be removed by any means except death. Regardless of where he might have got the idea, Washington was consciously trying to establish a tradition of public service by those who were natural leaders, dutifully responding to the need of the nation, and stepping down when the service was completed. It was an important day for him and for the nation, when he stood before John Adams in 1796, honorably and humbly turning over supreme power to a successor who had been chosen, by others, in a lawful way. Peaceful succession is part of the original intent of the founder of the Constitution, if anything is.

Some have written that Washington was not our first president, but our eleventh if one counts those elected the presiding officers of the Continental Congress, under the Articles of Confederation. But none of them could be said to be the head of state, and absolutely none of them could be confident the public would re-elect them indefinitely. Washington was not so much aiming for a two-term limit as he was setting a pattern for returning the choice to the people after a stated term, and deploring anyone who sought unlimited power for its own sake. The office should seek the man, not the man seek the office, and even if the public got carried away by adulation, the man should in good time step aside. For over a century the two-term tradition was later unchallenged, until Franklin Roosevelt succumbed to exactly the temptations that Washington foresaw. We have seldom amended the Constitution, but after Roosevelt, it was soon amended to emphasize what so many had previously considered it unnecessary to state.

The idea of a fixed term of office has had an unexpected calming effect on partisanship in America. In parliamentary systems like the British, a prime minister answers weekly questions from his opposition, with a full realization that he can be dismissed from office at any moment he angers a majority into a vote of no-confidence. Under the American Constitution, a recent election mandate eats into the stated time in office, making it progressively less rewarding to evict the officer for the residual time before another election does it automatically. America does indeed have an impeachment process, but in fact, it has been rarely employed. In America, if someone is elected for a specific term, it is almost certain he will serve out the full term. There are times when partisanship seems unlimited, but in fact, we probably have less of it than if we encouraged partisan outcry to go on to evicting an incumbent from office.

Washington was not so successful in promoting another component of his ideal statesman. In his view, a district would naturally select the most prominent citizen available to represent the district, since that person would do it more ably than anyone else and give up the office when duty was completed; that was behind the stated ideal of republican government. Madison was for a time persuaded that such choices should be filtered a second time, with the House of Representatives electing Senators from its midst, but that failed to win approval. In the Eighteenth century, the concept of professional bureaucrats and professional politicians had not yet taken hold. In its place was the fear of "ambitious" leaders, who would be held in check by a tradition of underpaying elected representatives, or even of gentlemen of means who would refuse to accept any pay for doing their duty. It proved unanswerable when ambitious men assailed this republican concept by protesting the establishment of aristocracies, oligarchies, and failure of the upper class to understand the needs and anxieties of the common man. This viewpoint eventually replaced the "natural" local leaders with those who had experienced life in a log cabin or endured the purifying experiences of other hardships. The original idea of the founders was to elect leaders who could not be bought; ambitious men could be bought. When political parties made their appearance, a new thought appeared; perhaps ambitious men could be controlled.

As the practical realities of politics in action began to surface, members of elected bodies with varying degrees of ambition and altruism sought refuge from pressures being applied to them. After all, one of the undeniable implications of the Constitution was that every single member of an elected body had just as much power and rights as every other one. Out of this tension emerged the seniority system, another unwritten rule with the power of reality forging it into an implicit rule. In time, everyone would achieve seniority at the same point in his career, and hence the procedural powers necessary to running the place could be assigned with lessened fear of improper pressure. Newcomers regularly complain about the seniority system but eventually yield to it as the least bad accommodation to necessity. But even minor imperfections will be exploited if a system endures long enough. In this case, political parties in the home states are persuaded that the fruits of seniority might be disproportionately available to them if they elect young candidates and keep them in office indefinitely. Eventually, such stalwarts can rise to positions that allow them to reward the home district. This has the interesting consequence of creating political families, whose senior representative acquires the power to select his son or grandson to take his place in the rising chain of command. That's not as bad as an inherited aristocracy, perhaps, but it has several similarities.

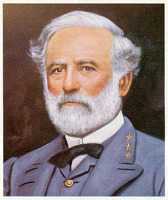

Designing the Convention

|

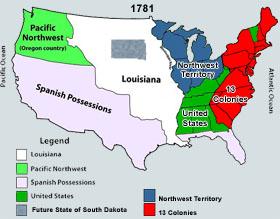

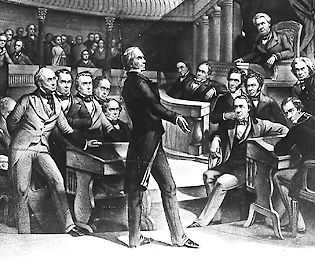

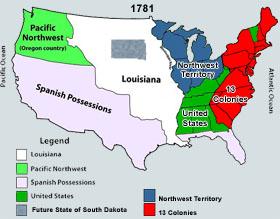

| The Convention and the Continent |

THE prevailing notion of the Constitutional Convention once depicted James Madison as seized with the idea of a merger of former colonies into a nation, subsequently selling that concept to George Washington. The General, by this account, was known to be humiliated by the way the Continental Congress mistreated his troops with worthless pay. But recent scholarship emphasizes that Washington noticed Madison in Congress becoming impassioned for raising taxes to pay the troops, was pleased, and reached out to the younger man as his agent. Madison seemed a skillful legislator; many other patriots had been disappointed with the government they had sacrificed to create, but Madison actually led protests within Congress itself. A full generation younger than the General and not at all charismatic, Madison's political effectiveness particularly attracted Washington's attention to him as a skillful manager of committees and legislatures. Washington was upset by Shay's Rebellion in western Massachusetts, which threatened to topple the Massachusetts government, but Shay's frontier disorder was only one example of general restlessness. There was a long background of repeated Indian rebellions in the southern region between Tennessee and Florida, coupled with uneasiness about what France and England were still planning to do to each other in North America. It looked to Washington as though the Articles of Confederation had left the new nation unable to maintain order along thousands of miles of the western frontier. The British clearly seemed reluctant to give up their frontier forts as agreed by the Treaty of Paris, and very likely they were arming and agitating their former Indian allies. Innately rebellious Scotch-Irish, the dominant new settlers of the frontier, were threatening to set up their own government if the American one was too feeble to defend them from the Indians. The Indians for their part were coming to recognize that the former colonies were too weak to keep their promises. With the American Army scattered and nursing its grievances, the sacrifices of eight years of war looked to be in peril.

The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured ... by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was "to form a more perfect Union.

|

| A.Lincoln, First Inaugural |

Even Washington's loyal friends were getting out of hand; Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris had cooked up the Newburgh cabal, hoping to provoke a military coup -- and a monarchy. Because they surely wanted Washington to be the new King, he could not exactly hate them for it. But it was not at all what he had in mind, and they were too prominent to be ignored. So he had to turn away from his closest advisers toward someone of ability but less stature and thus more likely to be obedient. It alarmed Washington that republican government might be discredited, leaving only a choice between a King and anarchy. Particularly when he reviewed shabby behavior becoming characteristic of state legislatures, something had to be done about a system which proclaimed states to be the ultimate source of sovereignty. Washington decided to get matters started, using Madison as his agent. If things went badly he could save his own prestige for other proposals, and Madison could scarcely defy him as Hamilton surely would. Washington could not afford to lose the support of the two Morrises, and still, expect to accomplish anything major. Madison had been to college and could fill in some of the details; Washington merely knew he wanted a stable government and he did not, he definitely did not, want a king. Many have since asked why he renounced being King so violently; it seems likely he was projecting a public rejection of the Hamilton/Morris concept in a way that did not attack them for proposing it. It was a somewhat awkward maneuver, and to some degree, it backfired and trapped him. But Madison proved a good choice for the role, and things worked out reasonably well for the first few years.

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the Federal Government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State Governments are numerous and indefinite.

|

| J.Madison, Federalist#45 |

Madison was young, vigorous and effective; he held the widespread perception of the Articles of Confederation as the source of the difficulty, and he was a reasonably close neighbor. He was active in Virginia politics at a time when Virginia held defensible claims to what would eventually become nine states. Negotiations for the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 would be going on while the Constitutional Convention was in session, and Virginia was central to both discussions. After conversations at Mount Vernon, a plan was devised and put into action. Washington wanted a central government, strong enough to energize the new nation, but stopping short of a monarchy or military dictatorship. There were other things to expect from a good central government, but it was not initially useful to provoke quarrels. Madison had read many books, knew about details. Between them, these two friendly schemers narrowly convinced the country to go along. As things turned out, issues set aside for later eventually destroyed the friendship between Washington and Madison. Worse still, after seventy years the poorly resolved conflict between national unity and local independence provoked a civil war. Even for a century after that, periodic re-argument of which powers needed to revert to the states, which ones needed to migrate further toward central control, continued to roil a deliberately divided governance.

|

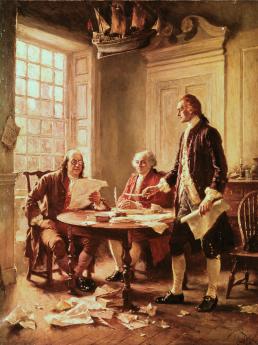

| Constitutional Convention |

For immediate purposes, the central problem for the Virginia collaborators was to persuade thirteen state legislatures to give up power for the common good. The Articles of Confederation required unanimous consent of the states for amendment. To pay lip-service to this obstacle, it would be useful to convene a small Constitutional Convention of newly-selected but eminent delegates, rather than face dozens of amendments tip-toeing through the Articles of Confederation, avoiding innumerable traps set by the more numerous Legislatures. In writing the Articles of Confederation, John Dickinson had been a loyal, skillful lawyer acting for his clients. They said Make it Perpetual, and he nearly succeeded. The chosen approach to modification was first to empower eminent leaders without political ambitions and thus, more willing to consent to the loss of power at a local level. Eventual ratification of the final result by the legislatures was definitely unavoidable, but to seek that consent at the end of a process was far preferable because the conciliations could be offered alongside the bitter pills. Divided and quarrelsome states would be at a disadvantage in resisting a finished document which had already anticipated and defused legitimate objections and was the handiwork of a blue-ribbon convention of prominent citizens and heroes. By this strategy, Washington and Madison took advantage of the sad fact that legislatures revert toward mediocrity, as eminent citizens experience its monotonous routine and decline to participate further in it, but will make the required effort for briefly glamorous adventures. Eminently successful citizens are somewhat over-qualified for the job, whose difficulties lesser time-servers are therefore motivated to exaggerate. To use modern parlance, framing the debate sometimes requires changing the debaters. In fact, although he had mainly initiated the movement, Washington refused to participate or endorse it publicly until he was confident the convention would be composed of the most prominent men of the nation. This venture had to be successful, or else he would save his prestige for something with more promise. Making it all work was a task for Madison and Hamilton, who would be replaced if it failed.

|

| John Dickinson |

While details were better left hazy, the broad outline of a new proposal had to appeal to almost everyone. Since the new Constitution was intended to shift power from the states to the national government, it was vital for voting power in the national legislature to reflect districts of equal population size, selected directly by popular elections. That was what the Articles of Confederation prescribed. But no appointments by state legislatures, please. In the convention, it became evident that small states would fear being controlled by large ones through almost any arrangement at all. On the other hand, small states were particularly anxious to be defended by a strong national army and navy, which requires a large population size. England, France, and Spain were stated to be the main fear, but small states feared big neighboring states, too. Since the Constitutional convention voted as states, small states were already in the strongest voting position they could ever expect, particularly since the Federalists at the convention needed their votes. Eventually, the agreement was found for the bicameral compromise suggested by John Dickinson of Delaware, which consisted of a Senate selected and presumably voting as states, and a House of Representatives elected in proportion to population; with all bills requiring the concurrence of both houses. From the perspective of two centuries later, we can see that allowing state legislatures to redraw congressional districts gives them the power to "Gerrymander" their election outcomes and hence restores to the populous states some of the internal Congressional power Washington and Madison were trying to take away from them. In the 21st Century, New Jersey is an example among a number of states where it can fairly be said that the decennial redistricting of congressional borders accurately predicts the congressional elections for the following ten years. The congressional seniority system then solidifies the power of local political machines over the core of Congressional politics. However, the irony emerges that Gerrymandering is impossible in the Senate, and hence legislature control over their U.S. Senators has been weak ever since the 17th Amendment established senatorial election by popular vote. That's eventually the opposite of the result originally conceded by the Constitutional Convention, but possibly in accord with the wishes of the Federalists who dominated it.

|

| Electoral College Method for Election of the President |

This evolving arrangement of the national legislative bodies seemed in 1787 an improvement over the system for state legislatures because the Federalists believed larger legislatures would contain less corruption because they had more competing for special interests to complain about it. There were skeptics then as now, who wished to weaken the tyranny of the majority so evident in the large states and in the British parliament. To satisfy them, power was redistributed to the executive and judicial branches, which were intentionally selected differently. Here arises the source of the Electoral College for the election of the President. It gives greater weight to small states (and provokes a ruckus among large states whenever the national popular vote is close). Further balance in the bargaining was sought by lifetime appointments to the Judiciary, following selection by the President with the concurrence of the Senate. Without any anticipation in this early bargaining, an unexpectedly large executive bureaucracy promptly flourished under the control of the chief executive, lacking the republicanism so fervently sought by the founders everywhere else. This may be in harmony with the Federalist goal of removing patronage from legislature control, but Appropriations Committee chairmen have since found unofficial ways to assert pressure on the bureaucracy. It's quite an unbalanced expedient. Only in the case of the Defense Department is the balancing will of the Constitutional Convention made clear: the President is commander in chief, only Congress can declare war. Although this difficult process was meant to discourage wars, it mainly discouraged the declaration of wars; other evasions emerged. From placing the command under an elected President, emerges a stronger implicit emphasis on civilian control of the military, loosely linked to the fairly meaningless legislative approval of initiating warfare. There have been more armed conflicts than "declarations" of war, but no one can say how many there might otherwise have been. And there have been no examples of a Congress rejecting a President's urging for war.

And that's about it for what we might call the first phase of the Constitution or the Articles. In 1787 there arose a prevalent feeling that national laws should pre-empt state laws. In view of the need to get state legislatures to ratify the document however, this was withdrawn. The Constitution was designed to take as much power away from the states as could be taken without provoking them into refusing to ratify it. Since ratification did barely squeak through after huge exertions by the Federalists, the Constitution closely approaches the tolerable limit, and cannot be criticized for going any further. Since no other voluntary federation has gone even this far in the subsequent two hundred years, the margin between what is workable and what is achievable must be very narrow. Notice, however, the considerable difference between Congress having the power to overrule any state law, and declaring that any state law which conflicts with Federal law is invalid.

The details of this government structure were spelled out in detail in Sections I through IV. However, just to be sure, Section VI sums it all up in trenchant prose:

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding. The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.

Except for some housekeeping details, the structural Constitution ends here and can still be admired as sparse and concise. That final phrase about religious tests for office sounds like a strange afterthought, but in fact, its position and lack of any possible ambiguity serve to remind the nation of grim experience that only religion has caused more problems than factionalism. Madison was particularly strong on this point, having in mind the undue influence the Anglican Church exerted as the established religion of Virginia. There are no qualifications; religion is not to have any part of government power or policy. By tradition, symbolism has not been prohibited. But government as an extension of religion is emphatically excluded, as is religion as an agency of government. Many failures of governments, past and present, can be traced to an irresolution to summon up this degree of emphasis about a principle too absolute to tolerate wordiness.

A Gleam in Washington's Eye

|

| George Washington Taking Oath |

On the eve of the Constitutional Convention, the nation was unhappy, confused, and dissatisfied; this wasn't what a victory was supposed to feel like. George Washington wanted a country to be proud of, big enough to discourage enemies, otherwise free of policing, regulation, or monarchy. Eight years of war had taught him it wasn't easy to have both liberty and discipline at the same time. Perhaps America was more unusually blessed, however, defended from invasion by oceans and wilderness, and from greed by a continent of natural resources. If order and justice could be organized, perhaps this by itself would enlist the loyalty of that mixture of classes and nationalities then flocking to our shores. Several important writers were having a strong influence on the era we now call the Enlightenment; David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, Edward Gibbon in England, Voltaire and Diderot in France, even Catherine the Great of Russia, with a thousand others including Benjamin Franklin and Robert Morris. Although Washington probably hadn't read them, Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations showed unvarnished new ways of looking at commerce and politics, while Gibbon's The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire showed what could happen if idealism gets neglected. Both books were published in the portentous year of 1776, describing many difficulties, but always suggesting problems could somehow be solved. There were plenty of ideas in circulation, but there was no plan.

It must have become obvious to Washington well before the Battle of Yorktown, that the Revolutionary War would not leave us with our problems solved. There was one brief moment as the British Army was withdrawing from Philadelphia in 1778 which seemingly justified boasts our troops had licked 'em. Just after the surrender of a whole British Army at the Battle of Saratoga, the British were also retreating from Philadelphia, and the Lord North offered generous peace terms through the Earl of Carlisle. No doubt the British public was restless after the Burgoyne defeat and the French alliance with America. Because the Carlisle episode is much more familiar in England than in America, perhaps it was a feint or a maneuver to embarrass the Earl of Carlisle or possibly just an exploration of the true state of affairs which were rumored about across a wide ocean. At any event, Gouverneur Morris was the visible American actor in this puzzling episode, but he must have been acting in concert with others. Lord North offered to give us our own elected parliament within a commonwealth; taxation with representation, no less. Morris seems to have dismissed this offer with contempt. But six more years of devastation ensued, surely convincing Washington that bitter defeat was still possible. That reality was concealed behind the graciousness of the French in allowing us to claim American troops had defeated the British at Yorktown. In fact, the preponderance of troop casualties, naval vessels and strategy had been French. The money had been mostly French as well. If that debt nearly bankrupted France, what might it have done to America?