1 Volumes

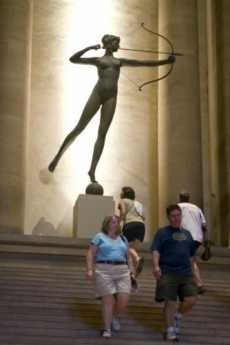

Rt. Angle by Years

The history of Philadelphia"s finest men's club.

Right Angle Club 2011

As long as there is anything to say about Philadelphia, the Right Angle Club will search it out, and say it.

My fellow Right Angle Club Members:

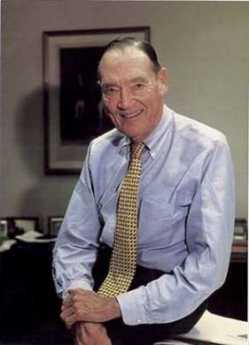

The 2011 Annual Report offers me the opportunity to thank my fellow Board of Control members and to report to the membership at large on the "State of the Club" in our Eighty Ninth (89th) Year.

The state of our Club is Excellent! The 2011 years saw an expansion of the modernization efforts begun in 2010 under our past President, Joseph A. Martinez, Jr. Beginning with the establishment of Affiliate Membership to stabilize and grow our membership and internet website development in 2010, our Club started with the 2011 President's Dinner to use web based event invitation and management program for Club Special Events. The web based system allowed members to register on-line without the need of mailing paper reservation to our Special Events Chairman, Mel Buckman.

Our Eighty Ninth year also marked the start of our "Friday Evening Buffet's at the Racquet Club of Philadelphia." The six evening buffets were designed to allow members to bring their wives, significant others or guests, to what is essentially the exact same social program as our members only Friday luncheons, also at the Racquet Club of Philadelphia. The Evening buffets were well received and attended. I suspect that our President-elect, John Fulton, will continue the program in 2012 but at a slightly reduced number.

There were some growing pains in 2011 that caused the cancellation of our traditional "Spring Fling." Due to uncertainty in our financial status, our long serving Treasurer, Rod Rothermel, advised the Board of Controls, that the Club was operating in a deficit [sounds familiar] and the Board voted to cancel the "Spring Fling." The Treasurer's report also resulted in several changes in the Club's traditional way of doing business.

First, a permanent Finance Committee was established to oversee the Club's financial activities. The Finance Committee is made up of the immediate past President as Chairman, [Joe Martinez 2011], member: 1st Vice President- Special Events Chairman, [Mel Buckman] and a member appointed by the President, [Jerry Leon 2011]. I want to point out and give a special thanks to the members of the Finance Committee for an excellent job and numerous hours of hard work given in service to the Club. Well done all!

Second, as it was discovered by the Finance Committee, the Board of Controls itself was unknowingly contributing to a chronic expenditure deficit due to the ten annual Tuesday Board of Control meeting held at the Racquet Club, despite an annual payment "to be Club" by all Board members. Starting in 2011, Board of Control meeting are now scheduled just before a regular scheduled Friday luncheon at a saving of several thousand dollars annually to the Club. Not surprisingly, the Board of Control meetings have now lost the traditional social and comradeship of the past. No small loss but a necessary one.

Third, the Finance Committee has implemented a 21st Century "Quicken" financial computer program to insure that uncertainty of the Club's financial status is no longer an issue in the future. The computer program will allow for a greater degree of fiscal control and budgeting. It is expected that on-line credit card payments for special events and ultimately Club dues will be offered in the near future. With acknowledgement to the extraordinary efforts of Special Events Chairman, Mel Buckman, the success of the Financial Committee was demonstrated by the our 2011 "Spring Fling" coming in under budget.

With our fiscal house in order, the Board of Control, under the leadership of our 1st Vice President, John Fulton, addressed the existential thread to the Club future, due to declining membership. In fact, in one month in 2010, the Club lost ten(10%) of it's membership due to deaths or resignations. I can report to the Club that the negative trend has been reversed but we are not out of the woods. The "Member/guest Social" has been a proven success in attracting new members particularly 'Affiliate Members' that now number approximately ten (10)members. The Board of Control has capped the number of 'Affiliate Members' at any one time at 12 to protect the social tradition and integrity of the Club. The good news is that the 'Affiliate' Membership program has worked as planned with two 'Affiliate Members,' Dan Sossaman, Jr. and Steve Bennett, after experiencing Club activities, up graded their membership to 'Regular Full Member' in 2011. The Right Angle Club's membership is insure in the future of the Club by recruiting new members.

In 2011 the Board of Control turned it's attention to the issue of membership retention through the use of the Club's first ever, Membership Survey. Special thanks are due to past Club President, Ted Burkett and Board member, Peter Alois, for design of the survey questions. The goal of the survey was very simple. The Board wanted to give all the Club membership the opportunity to give their opinion on the Club's programs and activities. A another surprise to this writer, almost eighty(80%) percent of the Club membership responded to the survey. The Results, which were forwarded to the membership, clearly show that the Club is headed in the "Right" direction. Membership satisfaction was extremely positive. No major changes in the Club's programs or activities are needed according to the 2011 Club survey.

No Right Angle Club job, and I mean job, is more difficult or nerve-racking[while waiting for the speaker to actually arrive]then 3rd Vice President-Speaker Chairman. A very special thank you and acknowledgment to our 2011 Club Speaker Chairman, Jerry Leon. Only a past Speaker Chairman can understand the hours of effort that go into securing some 35 to 40 speakers for the Club's weekly programs. Jerry had on advantage over most Speaker Chairman, he could stand up and just tell you the incredible events he experience in his life. Like flying jet aircraft in the Korean War with Hall of Fame great, Ted William and entertainer great, Ed McMann or being the infamous Lee Harvey Oswald's, Commanding Officer in Japan. Jerry's talks keep those lucky enough to attend on the edge of their seats. Great job Jerry! Simper Fidelis!

Our 2011 Club Special Events under the leadership of Mel Buckman, were the traditional activities of the Club with the "Fall Fling" at the Corinthian Yacht Club, the historic First Baptist Church of Philadelphia and the Christmas Party at La Viola West. Each event was an outstanding success as expected of the Right Angle Club. Well done Mel

The great ship, 'RAC Board of Control,' does not sail by itself. I would like to thank our other officers, 4th Vice President, Jack Foltz, our raffle master; Treasurer, Rod Rothermel, paymaster; Archivist David McComack, ship's stories; Corresponding Secretary, Neale Bringhurst, signal master; REcording Secretary, David Richard, ship's logbook; Peter Alois, able body rower; Bill Hill, able body rower; Dan Sosseman, Sr., so so rower,[just kidding]. Well done, one and all!

Special thanks are also the Order of the Day for Jack Nixon and Buck Scott of our 2011 Club Nomination Committee and Chic Kelly, our Club Captian. Well done!

In 2011 the Board of Control was pleased to announce they had secured Reciprocal Club privileges at the Racquet Club of Philadelphia [RCP] for all members that include: 1) lunch in RCP luchroom; 2)service at the Main[Players Lounge] Bar; 3)booking overnight room; 4) booking private parties; 5) Barbershop Privileges; 6)Happy Hours in Reading Room (May to September); 7) Wednesday nights buffers (September to May). Members merely have to identify themselves as Right Angle Club members and pay with a credit card. Right Angle Club members do not have charging privileges.

It is only fitting that I conclude this "State of the Club" report to our membership with some comments on 2012, the start of the Ninetieth (90th) year of the Right Angle Club. The 2012 President's Dinner at the Philadelphia Club will see the instillation of President, John Fulton. I can say without any doubt, that John will be oversee the continuing modernization efforts begun in 2010 under our past President, John A. Martinez, Jr. The Club will continue to develop internet based events management, a first rate 21st Century web site with a current membership directory accessible only to C;lub members and on-line payment for special events and dues. John will be helped by the Club's first professional Wedmaster, one of our own, Dan Sossaman, Jr. [or Younger...your call]. Why? To make life easier, a little less aggravating and allowing us, one and all, more time to "pursue happiness."

God speed, John J. White, past President.

Gum

|

| Gum Bubble |

The ancient Greeks and Romans are said to have enjoyed a sort of chewing gum. The ingredients are uncertain but unlikely to have been chicle, the sap of a variant rubber tree, which was taken up by the Mayans in the First century. The vision thus ensures that Mexican soldiers might well have been chomping when they set out to conquer Texas and devastate the Alamo. Conceivably Santa Ana himself was popping bubbles when Sam Houston found him crawling through the tall grass when he should have been dying like a man.

What is not so fanciful is that Santa Ana did go into exile in the United States, seeking refuge on Staten Island. Taking along a large supply of chicle, he was hoping to find a way to change it into rubber and thus restore his fortunes. His New York landlord, a photographer named Adams, struggled unsuccessfully for months to change the gum into rubber, but eventually switched over to chewing gum of chicle. This Mexican rubber variant is chewy only within a narrow temperature range, getting brittle when cold, and sticky when hot. The outcome of this bizarre episode was the Adams brand of chewing gum, a dominant feature of our culture until 1922 when William Wrigley, Jr. of Chicago added a mint flavor and made a great fortune selling the hope that minty taste would clean your teeth, sweeten your breath, and improve attractiveness to the opposite sex. Wrigley must have been a great businessman, since the Wrigley Building still dominates central Chicago, while everyone knows about Wrigley baseball field, and his descendants even run a private railroad through the Copper Canyon south of Tucson into Mexico. Wrigley's winter mansion sits on top of a small mountain outside of Phoenix, once affording a grand view of the surrounding desert for many miles. But subprime mortgages helped build up the desert, so at night there is now a sparkling view of the lights of Phoenix suburbs, longingly gazing up at Wrigley's mountain fastness filled with pictures of relatives who got themselves great notoriety, mostly related to unfortunate escapades with love.

Well, whatever. By 1960 a cheaper synthetic chemical came to replace chicle in Chiclets without distressing the customers and seemingly making it commercially practical to spread this central feature of American culture to Asia, Europe and beyond, with the notable exception of France which makes their cultural superiority a point of national pride. On further reflection, if they prefer vintage chicle to the present chemically improved synthetic, the French may have an important insight. Just look at our filthy sidewalks.

Other cities may be more diligent in scrubbing their sidewalks, but at least in Philadelphia, the new synthetic chewing gum is leaving its mark. The realization gradually creeps up on you that sidewalks near popular corners of the center city are spotted with round black spots, slightly larger than a silver dollar, but uniformly black. Just what the sidewalks around high schools look like, I tremble to consider. But those city corners where a sidewalk vendor parks his cart are particularly peppered, representing the disgusting habit of spitting the chew-gum on the sidewalk before eating the hot dog. The detritus is flattened out by someone's shoe, and the result is quite distinctive. As I was contemplating a particularly loathsome street corner, a passing Philadelphia Grand Dame shared her insight with me that the gum attracts dirt and gets black. I somehow doubt that because it is such a uniform blackness. It seems more likely that the trade secret chemical deteriorates in the sunlight, and being less sticky than the traditional goo, sticks to the sidewalk instead of the shoe which squashes it.

So think this over. Someone was recently chewing that stuff; would you kiss that person? If it's fresh enough, it might transmit the flu virus to your shoe; ye Gods, maybe the HIV virus, perish the thought. There's a great absence of evidence about the disease transmissibility of this unknown material. Maybe our congressmen should take a recess from blaming Wall Street for the decline of Greece and Portugal. And make chew-gum scoopers just as mandatory as pooper scoopers.

Footnote: A fellow member of the Right Angle Club recently revealed he had once worked for the Philadelphia Chewing Gum Company in Havertown, which was closed by new owners in 2003. While he didn't know anything about the ingredients of gum, he could report that this company used trainloads of old rubber tires for some purpose. On further checking, it is stated in the literature that at the present time, no chewing gum doesn't use rubber, so apparently Santa Ana's dream has finally come true in a round-about way.

Mennonites: The Pennsylvania Swiss

|

| On the Wall of the Mennonite Heritage Center |

Anabaptism, originally attributed to Ulrich Zwingli around 1525, centers around believing a baby is too young to understand baptism, so adults need to be re-baptized. The idea arose independently in Switzerland and Holland, and probably thousands of believers were unmercifully martyred for holding the belief. Because the worst persecutions took place during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-50), they are often attributed to the Roman Catholic Inquisition, but Magisterial Protestants, believing in the separation of church and state, were often also responsible. Many seemingly unrelated issues were introduced locally, and this period of unrest is known as the French and Indian War in America; its major battle took place in Louisburg, Nova Scotia, although George Washington's skirmish around Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) has acquired local fame as a major American manifestation.

The Swiss adherents moved to the Rhineland Palatinate, and from there were among the first to accept William Penn's offer of religious freedom. They were the settlers of Germantown, but have mainly moved a few miles west to southern Montgomery County, where the confusion about Pennsylvania Dutchmen is further confounded by the fact that they were Swiss. Menno the Dutchman gave his name to the order, but they themselves regard their true ethnic background as Swiss from the Zurich region. That, by the way, is not to be confused with Calvinism, which also comes from Switzerland, but by way of Geneva, not Zurich. The pacifism of the Mennonites made them mutually attractive with the English Quakers, who had made an appearance fifty or so years later in the region around Manchester, England; each group seems to have adopted some of the features of the other.

|

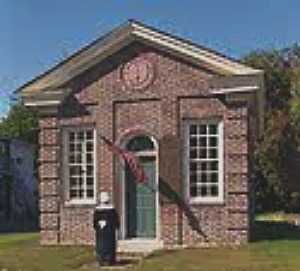

| Franconia Mennonite Meetinghouse |

Determined use of the German language has always held the Mennonites apart, however. From the start, it was really necessary to be somewhat bilingual in Montgomery County, using English for business conversation, and German at home and in the church. The idea of using a foreign language is based on the hope it would thus maintain a sense of distinctiveness or even remoteness from non-believers, without adopting the least hostility to them. It almost inevitably follows that the group has used its own schools, attached to their meeting houses. This sense of remoteness has persisted for almost four hundred years, surrounded by entirely different cultures. Starting only around 1960, this attitude has gradually softened, however, and it is widely assumed that in another few decades Mennonites will come to resemble the people in their environment a great deal more than they do at present. If you want to know where to find them, Harleysville is a good place to start. As the tinge of Pennsylvania Dutch accent gradually fades, and fewer of them wear the old costumes, a curious remaining hallmark of their presence can be noticed: an avoidance of foundation planting around their houses. The Mennonites themselves seem to be entirely oblivious to this unintended distinctiveness, which is however quite striking to non-Mennonite passers-by. Those who work in the fields all day have little interest in digging around their houses for decoration; those who have moved away from farming have seemingly adopted the bush-less style as a natural way of arranging things. There's no particular reason to change it, and so, there's no particular reason to notice it.

South Philadelphia: Ideal Intermodality Transportation Site

The Right Angle Club was recently visited by Troy Adams, representing the Greater Philadelphia affiliate of the regional Chamber of Commerce. Sustained by contributions from sixty local corporations, the Greater Philadelphia organization is a major storehouse of data useful for businesses, supported by a staff of analysts and computer experts. The purpose of this institution is to help businesses who are trying to decide whether or how to locate in the Philadelphia region. With such an organization behind him, Mr. Adams was able to show a number of slides displaying the demography, geography, and statistics about our region, and his appearance is greatly appreciated. This is definitely the place to go if you have questions of that sort. It would probably also be a good place to go for opinions and gossip about the politics and inside baseball of the town, but the Chamber has a strict rule about avoiding any involvement in business moving from one district to another within the region or hearsay that might lead to such internal friction.

One really important insight into the potential of our region concerns South Philadelphia. Historically, this was the place where the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers met, and was once a very big swamp (wetland, nature sanctuary or whatever). Over time, the swamp became a trash and garbage landfill, and over still more time it became a big flat uninhabited area right next to a big city. But then an Interstate Highway (I95) was built on its circumference, and several rail lines, and an international airport, not to mention extensive port and shipping terminals for ocean transport. While it is true that a certain number of houses would have to be purchased and demolished to accomplish it, the potential exists for the construction of an intermodal interconnection which would be almost unique in the world.

|

| South Philadelphia Ports |

There would be plenty of lands left over for industries related to freight forwarding and the like (the food distribution center is a good example of the general concept), and all of this would be within twenty minutes of the center of a major city. SEPTA already sends a passenger rail spur from the very heart of the city to the very center of the airport, and there is no reason it could not be extended to include ocean, bus, and distribution terminals. Whether this exactly fits with the extensive sports stadium complex in the area is unclear, but these entertainment features are doing no harm to the intermodal interchange idea in the meantime. Judging by the city government's willingness to tear these structures down every five or ten years, there should be no great resistance to moving them elsewhere if the need should arise.

Net Neutrality and Vertical Integration

|

| Late Hour Calls |

My fancy new cell phone has an annoying habit of ringing a bell every time an e-mail arrives, which is a little puzzling when it rings in the middle of the night. The email program displays time of arrival, so after a while, I took the trouble to see who was emailing me at 4 AM. It seems to be spam and other commercial programs, but it is also an occasional letter with a large attachment, which had been sent several hours earlier. At this, a light began to go on in my head.

I had been told the internet measures the size of files and puts big ones at the end of the queue. That seemed to explain the occasionally delayed transmission of ultra-large emails at times of heavy internet traffic. And it brings up the issue of net neutrality. If the traffic in large files grows enough, it might eventually clog the wires and bring things to a halt. The internet providers would have to spend money to build additional capacity, and it only seems fair to charge big users more for the costs they have created. That would seem a reasonable technological argument for allowing the networks to impose differential pricing, and for overturning the idea of net neutrality.

|

| Comcast and NBC |

Unfortunately, it might or might not be a sincere argument for resisting net neutrality, since there are major commercial issues at stake as well. For example, Comcast is trying to purchase NBC; its motives are clarified by remembering that a few years ago it tried to purchase Walt Disney. In both cases, a common carrier would be acquiring a "content provider", and thus acquiring a competitive advantage over competitive internet network providers who lack a captive source of content. A strong temptation would exist to slant the internet charges to the disadvantage of other competitors, thus providing a motive to get involved in insincere arguments about net neutrality. What we seem to have here is a familiar antitrust legal doctrine of "vertical integration". For years, vertical integration was prohibited, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed that prohibition a few years ago, in the case of State Oil v. Kahn. Lewis van Dusen and I had been in the audience of the State Oil arguments, because of our interest in the implications of vertical integration for the medical profession (doctors versus hospitals, for example).

|

| Curtis Publishing |

Although the example of Curtis Publishing was not introduced into the arguments of State Oil versus Kahn, it was much in my mind and might well have been used effectively to demonstrate the vulnerability of any corporation which attempts to become vertically integrated by purchasing its suppliers and/or distributors. Curtis Publishing, a few blocks from my office, had been a successful magazine publisher, so successful that it had enough profits to buy Canadian forests to use for paper pulp in its magazines. The outcome was the bankruptcy of the profitable magazine company when the paper pulp business fell on hard times. No antitrust action to prohibit vertical integration was necessary; the dismal fate of Curtis and similar integrators stood as an effective restraint on anyone else who was tempted to get into the vertical integration business. That may be a little hard to follow, and it took the Supreme Court many years to get to that point. But the fact remains that vertical integration is no longer illegal because it is effectively restrained by recognition of its dangers.

So, if we are getting into the insincere argument business, it is time for someone to put his arm around the shoulders of Comcast. Let's whisper that avoidance of the net neutrality dispute is kindly advice, offered solely for Comcast's own good.

|

| Comcast Center |

And, having gone this far in poking into other people's business, there might be some value in giving some advice to the antitrust lawyers. This sort of case can take years, even decades, to evolve through the legal system. And while its resolution will be phrased in legal terms, I'm not so sure that's sincere, either. It takes me back to the IBM case, where one of the junior lawyers was courting one of my daughters. This young fellow sat for months in front of a microphone at a deposition, doing nothing but read documents into the record. Although he was handsomely paid, the lawyer finally got so sick of the boring futility of dictating a mountain of transcript no one would ever read, into a microphone in an empty room, that he quit. And in the opinion of observers on the courthouse steps, the case was finally determined by the Judge's decision that the patent infringement business was trivial compared with the fact that IBM was mass-producing the greatest innovation of the century -- and the patent-infringement people were just getting in the road.

That may or may not have been the case, but it raises the question of whether antitrust law is wisely based when it considers, not the welfare of competitors, but the strength and vitality of competition itself. What might thus be considered paramount, and perhaps occasionally is so, is the economic welfare of the nation. At present, the newspapers regard this issue as a fight between Netflix and Comcast, and so are now free to devote news attention to other matters. I don't think so. I believe it directly challenges the operation of the Law, which contends that vertical integration eventually takes care of itself. To me, that is only true if circumstances give us enough time to wait it out. In the long run, as Maynard Keynes quipped, we are all dead.

Do Computers Thrive on Lead Poisoning?

|

| Get the Lead Out |

At a local outlet of a well-known chain of computer stores, the geek told me that small computer towers don't last as long as big-box desktops, perhaps only three years compared with the old five-year lifespan. And that's because they get hotter. Which is because they run faster than they used to, and also because a federal regulation prohibiting the use of lead in soldering joints makes the wiring wear out sooner. By the time he was done explaining things to me, I was ready to run out and join the local political Tea Party. Because I don't think it's very likely that toddler children will be eating my solder very soon, or even ever. And indeed, I have trouble imagining any children anywhere in the world ever nibbling on computer innards, even once. Maybe the concern is that the heat will vaporize the lead, and little children crawling on the floor will inhale the lead vapor, getting lead poisoning that way. While that may be somewhat more plausible than eating computer parts, or eating vegetables grown in the neighborhood of trash disposal, or breathing the air full of lead fumes -- it doesn't really seem very plausible at all.

It is generally reckoned that 835 million computers worldwide were manufactured in 2010. If they cost an average of $500 apiece and lasted 40% less long than if they used lead solder, the world would end up buying 300 million additional computers per year, conservatively spending $1.5 billion more dollars a year to do so. Are the dangers of lead poisoning so threatening that such a cost is justified on a hypothetical basis? The people who do the soldering are possibly at somewhat greater risk, but you could buy a lot of masks and air purifiers for the extra cost for computers alone. Can this possibly be true?

Is it possible that the geek in the computer store is just selling warranty insurance, or more expensive computers when he passes on this news? Is it possible that the makers of fumes ventilators are promoting their products in this way? How about the plaintiff trial lawyers. Are they calculating that frenzied citizens will wander into jury duty and be concerned to punish the evil makers of computers with gigantic penalties, of which the lawyers will get 40%? Or the makers of cool computer boxes are competing indirectly with the evil makers of hot computer boxes?

This article ends with a comment section. Those who can offer references to the facts, in this case, are urged to send them in. Something in this story doesn't stand the light of day, and perhaps a way can be found to shine a little light of day on the facts.

Future Directions for Book Authoring

|

| TSR-80/100 |

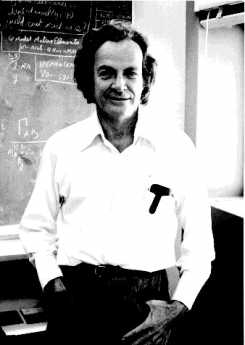

Here's some advice for new authors of books: You can't write the first chapter until you have written the last chapter. That is, you have to hit the reader between the eyes in the first chapter, draw him into the argument, making a pauseless transition from a general statement of the author's thesis into a relentless march of evidence toward the conclusion. This general design comes easier with practice and is therefore much harder for beginners to accomplish. But even experienced authors are usually unable to keep the overall design of their message constantly in mind, to be able to sit down and write the book straight through from beginning to end. It's true that Sir Walter Scott was said to turn over the last page of a book, and immediately begin writing the first page of the next one without getting up from his desk. But we aren't talking about pot-boilers, we're talking about serious books. That includes almost all non-fiction and the great majority of serious fiction.

As a matter of fact, the description includes the majority of short articles as well; newspaper editorials would be a good example. Although the style of an editorial is to start with a generality, marshal a description of some recent events, and end up with a short summary, that isn't in fact how it is usually composed. The editorial writer starts with a one-liner, or call to action, organizes some recent events and some historical arguments as a reason to issue such a call, and then ends up by summarizing things in the first paragraph. Having mentally designed the editorial into such a three-step pattern, with experience a professional editorialist can sit down and write the editorial from beginning to end and, after a few touch-ups, it's ready for the printer. He really has gone through the organizational process which a book author needs to go through, but the article is short enough so that reconstruction is performed in his head. In a book, it is generally necessary to write out the chapters in a jumbled way, and later re-organize them. A new author with his first manuscript generally doesn't adequately appreciate the truth of this and has to be muscled by the editor, at least just a little bit. One of my editors summarized his job as follows: you tell every new author to take the first four chapters of his book and throw them away,

That's cruel, of course, and is seldom accepted graciously. The brusqueness is justified by understanding that the fresh new author thinks he's all finished when he isn't. He's silently telling himself he means to tell that editor, "Don't you touch a single comma of it." In the old days, authors were rare and had to be coddled. Book publishers in the Eighteenth century purchased the manuscript in its entirety, either then losing money or making a huge fortune, but leaving the author with only his manuscript price. At that time, publishers called themselves booksellers. As things evolved, booksellers often had to support a starving author while the book was being written, offering an "advance" payment to be deducted from royalties paid after final sales to readers. Author royalties were about ten percent of sales. The royalty system persists today, but advance payments are uncommon and negotiated around the tax code effects. All of these payment evolutions reflect the underlying issue: good authors used to be rare, but now are frequent. Book publishers used to be wealthy, but now are rapidly going bankrupt and extinct. Authors of excellent books have a hard time finding someone to publish them. The advent of the personal computer around 1980 is what caused this.

In 1980 I published a book, writing it on my brand-new Radio Shack TRS-80, Mod I. The editor of the publishing house had never heard of such a notion, scoffed at it, and declared he would never touch such a thing as a computer. In 2010 there were more than 800 million personal computers manufactured and sold, and by this time almost no publisher will accept a manuscript without an accompanying magnetic disc to make revisions cheap and easy, and to shift the costs of key-entry from the publisher to the author. At first, manuscripts were shipped to India for key entry. Now, it is the diskette which is mailed or e-mailed to India, and the editor is often located in India. We are soon approaching a day when the keyboard and author remain at home, sending material to gigantic server computers in China, from which the editor anywhere in the world can retrieve the material and revise it, returning the material to the server computer where the author can comment on the revisions without moving from his desk. After that stage, looms the prospect of the reader paying a fee on his credit card to access the "book" directly from the server, and reading it at home. At that point maybe the book will have been completed, and maybe it will be revised some more. In a sense, a book will never be definitely finished and allowing the public to read it will only be an episode within an unending process of revision. Newspapers, magazines, and books are all struggling to find a way to cope with this unpredictable evolution. Like most revolutions, this one doesn't have a clear idea where it is going.

So let's reflect back on the central process of authoring. In addition to the old maxims of the trade, there is the Euclidian reality that you can't write the last chapter until you somehow write a first one. The original first chapter, the one the author struggled so hard to compose, is destined to be cast off and replaced by a new first one, one that succinctly announces what is about to be said. After that must come a new second chapter, which takes the reader from the initial disconcerting summary back to the origins of the problem now about to be clarified. Followed by a third chapter, probably one shifted forward from the assorted chapters of evidence back into prominence as the key piece of evidence which leads to other confirmatory pieces of evidence; after that marches the parade of confirmatory evidence, ending with one zinger of a conclusion.

Voltaire or some other cynic would probably comment that what has here been outlined is merely an elaborated process of what editorial writers do: start with the conclusion and find slanted facts to fit it. Some may indeed do that. But there is some hope that the inevitable impact of technology on authorship can bring us to a system where many authors will assemble the facts, and only then derive a conclusion from them. If politicians would only adopt that system, maybe we could hope for a perfect world.

Recalling the Names of Acquaintances

As age creeps up on us, just about everyone has a little trouble recalling the name of old acquaintances, particularly if they come upon us unexpectedly. Reactions to this affliction vary tremendously, with some folks concluding that Alzheimer's Disease is surely here already, so they run away and hide. Other seniors are more self-confident and unashamedly go ahead with little strategies to cope with this problem. When you sort things out, you tend to find that shy and retiring people withdraw from social contacts because of self-consciousness, whereas bluff, bold extroverts plunge ahead with strategies they have devised to cope with matters. Neither one of them can remember a lot of names. The extroverts are usually very happy to share their secrets; a whole social group can be transformed by one loud, happy, unashamed coper sharing his techniques.

The late Doctor Francis C. Wood, formerly Professor of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania after whom a number of professorships, institutes, and lectures are named, once made a little speech at a reception held at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. "When you see somebody at a party whose name you ought to recall but can't, just stride right up to him with your hand held out. Just say your name like a gentleman, like 'Fran Wood," and he will invariably grab your hand gratefully and tell you his name, like 'Jim Jones, Fran. How are you?' After that, you'll get along just fine."

This isn't a medical matter at all. It's a matter of self-confidence and learned techniques. Dick Maas, who is a resident of the Beaumont CCRC in Bryn Mawr PA, was recently proud to describe his own technique in the Beaumont News as follows:

"Let's start with the obvious conclusion that one can't remember something one didn't hear in the first place. Introductions often are given in a social situation, which usually means one is surrounded by loud noise. Furthermore, the person doing the introduction may have a soft voice or poor diction.

There's hope, however. One can employ a little trick that's socially correct and psychologically useful: Shake hands with your new acquaintance! Hang on until you hear the name clearly and correctly. If necessary, hang on and say, 'I didn't get your name. Would you please repeat it?' Even ask for a spelling if need be. Don't release the hand until you've heard it correctly and repeated it back."

|

| Handshake |

It isn't always necessary to use a name or shake hands. In Haddonfield where I live, the custom grew up years ago that everybody says, "Hello" or "Good Morning" (Good Morning preferred) to everybody one meets on the street -- before lunch. There's no hesitation about it, that other person is going to say "Good Morning," so you might as well get ready for it. Of course, it's true that some people don't know what to do with themselves, and retreat back into their shells, awkwardly trying to pass you by without acknowledging your greeting. You can either shrug your shoulders and assume that repetition will gradually bring that newcomer around in a few days or weeks, or else you can refuse to let them do that to you. Step in his way and say it louder. To get away with this you have to be prepared to say something about the weather or your dog or the morning news, which is a pleasant way of saying you weren't belligerent about it, just showing them the way things are done in Haddonfield. Pass yourself off as uncontrollably extroverted. And be sure to smile. This sort of custom is a matter of population density. Up in Alaska a trapper who passed within a mile of another trapper's cabin without saying, "Howdy" was inviting a knife fight about the insult. In New York's Times Square, by contrast, a pedestrian is within walking distance of two hundred thousand people; greeting everybody is an impossibility. Which leads me to a personal story.

At the Pennsylvania Hospital we had an orderly named Sam who was deeply religious and went around handing out religious tracts. He was pleasant and did a lot of work, so no one interfered. One day, I was walking in Times Square with my wife on one arm and my mother on the other. Looking ahead, I could see a crowd had formed around an orator on a soapbox, who was none other than Sam. I said nothing, but as we drew closer, my mother exclaimed about it and maneuvered the three of us up to the ringside to see the excitement. Sam stopped talking to the crowd, and shouted, "Hello, Doctor Fisher". So, of course, I replied, "Hello, Sam"; and the three of us kept walking down the street. After we had gone two blocks in puzzled silence, my mother abruptly stopped walking, stamped her foot, and said, "All right young man. Just who is this Sam?"

Passage to India

.JPG)

|

| Palace on Wheels |

Journalists tactfully intone that India has fallen behind in its infrastructure. Translation: it's often at real risk of your life to cross a street. The Indian road system is overwhelmed by avalanches of rickshaws, tick tocks (motorcycle rickshaws), little cars, big cars, buses, trucks, and motorcycles. All vehicles seem to be driven by teenaged maniacs, honking their horns and driving straight at you; the motor accident rate in India is among the worst in the world. It's not just a statistic. One tour bus we were riding bashed into a motorcyclist, and just kept on going even though the passengers yelled and banged on the windows. Conclusion: airplanes and trains are the only reasonably comfortable ways to travel in India today. In another twenty years, things will surely improve or India must strangle, but right now you better save your pennies to afford the Palace on Wheels. That's a tourist train making a big continuous loop through the main tourist attractions of central India, beginning and ending in New Delhi every Wednesday.

|

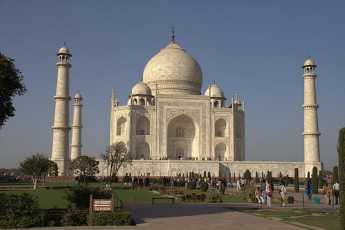

| Taj Mahal |

You would have to be pretty aloof to avoid acknowledging the other seven passengers who share a sleeping car with you: four bedrooms, two houseboys, and a living room. And you soon enough know the busload (thirty passengers) in your guide group. Ours was the Pink Group, definitely not named for its political leanings. With the passengers from four bedroom cars, you also share a bar car, arranged in a facing circle of overstuffed furniture, (just as you see extended families in Bollywood movies), a sitting in one of the dining cars, and one tour bus with a Pink sign in the window. Thus organized, the twenty-car train with three trailing buses carries a hundred tourists with well-practiced efficiency in the style which claims to treat each passenger as a maharajah. It is true these modern rajahs do not have three hundred concubines or twelve wives, as the real ones did. But the briefest reflection confirms that no sane man would want twelve wives or more than, say, twenty concubines. So the tourist's condition could in a way be held superior to that of any real maharajah. The central point at the moment, however, is that the arrangement of this brief collection of strangers lends itself to gossip and reckless self-description, sort of like a rolling girls' boarding school. There's really nothing much to talk about except each other, and only eight members in the conversation group.

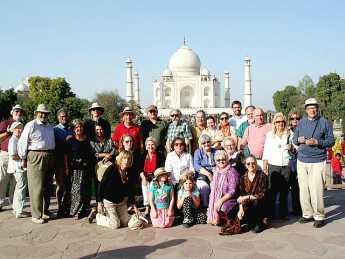

|

| The Pink Group |

While it was hard to overlook the mixed-ethnicity elderly couple in our midst, it was, of course, the ladies of the party who quickly assembled the essential bits of intelligence available. These two, an elderly Indian man with a broad smile and broader paunch, plus a thin wisp of a little white lady with the grace and social command of a duchess, had been friends in a Canadian nursing home where their children had placed them, had both lost their spouses, and then eloped to freedom. By escaping from the hateful nursing home they saved $9000 a month, so it really must have been a pretty upscale CCRC, or retirement village. In Canada, there is lots of snow, cozy like an igloo all winter, but unquestionably confining. A little bit of scientific background allowed me to estimate the life expectancy of these two to be about eight more years, or perhaps seven if you subtract the dismal last year that everyone should be glad to skip. These two had apparently counted up their resources, found they could afford better things than a nursing home and decided to make a dash for freedom to spend their last seven years in playland while they had the chance. The ladies in our group obviously thought this adventure was just about the most exciting thing ever and grinned approvingly at every new detail. Although our travel group overall seemed to have its fair share of boors, no one, absolutely no one was boorish enough to ask if there had been a wedding.

Like pimpled teenagers, the two would slip their hands together with the hope that if they didn't look at their hands, no one else would notice. So, from time to time, the gentleman would slide his hand onto her thigh. And she, with the practiced skill of a high school cheerleader, would wait thirty seconds and with a big smile aimed at no one in particular, brush his hand away. She was having a perfectly wonderful time because she knew very well that every other lady was watching every movement.

|

| Palace Train |

At about the same age, Ben Franklin once moved with the fast set in Paris in his eighties. In fact, Franklin probably moved with a fast set wherever he was at any age. He seldom discussed the topic directly except in that famous letter to his son which concluded, "And son, they are so grateful". In our present society which claims such infinite sophistication, Ben might now have expanded on the misdirected pressures of inheritance laws which thwart re-marriages. Or on new-found freedom, the age-related indifference to complicating children, which some couples miss more than others. In fact, Franklin's famous letter to his (illegitimate) son enumerates a list of other advantages of love affairs with older women which could just as easily have been listed by John Milton or Cotton Mather. At least one gentleman has given the opinion that Franklin was all mischievous talk and no action. But I dunno. That remark about how grateful they are surely carrying some implication of personal experience.

Competitive Institutions: Paying for Assisted Living

Around the turn of the 20th Century, it was the fashion to build specialty hospitals, devoted to a single disease like tuberculosis or polio, or one specialty like obstetrics or bones and joints. Eventually, it was realized that almost any disease is handled better if a full range of services is readily available to it. Around 1925, some inspired philanthropists made it possible to combine specialties within a medical center, and it is now generally agreed this is a better way when population density permits it. On the other hand, it is likely a source of price escalation. Time marches on, and the problems of excessive bigness are also beginning to predominate. The idea immediately occurs, to winnow out the routine cases which do not need so much technology, so that we can concentrate and devote high technology (and costs) to patients who will really benefit. And, immediately the perplexing outcry is heard that such rationalization is "cherry picking", which will soon bankrupt the finest institutions we can devise. The validity of such assertions needs to be examined impartially.At the same time, the horse and buggy era has been left behind, causing new separations along class lines, the flight to the suburbs, and the migration of philanthropy toward the exurban sprawl, as well as into urban centers. In all this commotion it was overlooked for a long time that medical care was not merely following the patients to new locations, it was becoming more of an outpatient occupation. Inpatient care was shrinking, and somehow expensive hospitals were swallowing their smaller (and less expensive) competitors. It wasn't a necessary development; Switzerland still favors small luxury "clinics" of ten or twenty beds, usually containing wealthy patients of a celebrity doctor. Local customs like this will change slowly. What America appears to need is more hospital competition and more ambulance competition; the two may actually be somewhat connected issues. For amusement, I once studied the patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on July 4, 1776, when historical notables were congregating three blocks away. The diseases were remarkably similar to what is seen in hospitals today; problems with the legs, mental incapacity, major injuries, and terminal care. People are treated in hospitals because they can't care for themselves at home.

A BLUE-RIBBON COMMITTEE NEEDS TO STUDY INSTITUTIONAL COMPETITION IN HEALTHCARE.

This is a complicated issue and may take several years, or even several studies to sort out. What is useful for urban settings may be inappropriate in exurban ones; local preferences must be separated from special pleading, and that is not always easy. However, the continuing care center seems to be a permanent direction which is growing in popularity, as is also true of rehabilitation centers and retirement communities. Many of these institutions might incorporate doctors offices for their surrounding community, using the same parking facilities and many of the same medical specialties for both the neighborhood and the core facility. There seems no reason to oppose either rentals or private condominium-style ownership nor any reason to resist group clinics. Exclusive arrangements, however, are more questionable. All of these arrangements should be studied, and unexpected problems flushed out. No doubt the preliminary studies would lead to pilot and demonstration programs. And some practices which initially seem harmless, should in fact be prohibited. We have a lot to learn before we start overturning the existing order. But nevertheless, some arrangements will prove to be superior to others, almost all of them are regulated in some fashion, and the regulations should be examined, too. It should accelerate needed changes to know in advance which ones are ready to be tested, and tested before they are demanded.

*******

.jpg)

|

| CCRCs |

Everyone knows Americans are living thirty years longer because of improvements in health care, and some grumpy people are waiting with glee to see if Obamacare will put a stop to that sort of thing. It must be left to actuaries to tell us whether the nation saves money or not by delaying the inevitable costs of a terminal illness. But one consequence has already made its appearance: people are entering retirement villages in their eighties rather than their seventies. Presumably, people in their seventies are feeling too well to consider a CCRC, although other explanations are possible.

Accordingly, a great many CCRCs are seen to be building new wings dedicated to "assisted living". A cynic might surmise there must be some hidden insurance reimbursement advantages to doing so, but the CCRCs are surely responding to some kind of increased demand when they make multi-million dollar capital expenditures. Assisted living is a polite term for people with strokes or Alzheimers Disease, or some other condition making it hard to walk, or, as the grisly saying goes, perform the activities of daily living. One really elegant place in Delaware has suites with servants quarters, but for most people, the only affordable option is to be in a room designed around the idea of assisting an invalid. It's generally smaller and more austere but fitted out with railings and bars and special knobs. Meals generally have to be supplied by room service.

Not everyone is destined to have a protracted period of decline, but it's fairly frequent and universally feared, so it's a comfort to know your present residence is attached to a wing which provides for it. The question is how to pay for it. There are two main approaches currently in use, adapted to the limited financial resources of the aged and the particularities of CCRC arrangements.

In the first arrangement, there is no increased charge for moving to assisted living, which helps overcome resistance to going there. However, the monthly maintenance charge for others who remain behind in "ambulatory living" is increased, usually about 20%, to provide funding for those who eventually need special assistance. That's a financial pooling arrangement, sort of an insurance plan, and like all insurance, it has a tendency to increase usage unnecessarily. It also increases the cost to those who enter the CCRC at an earlier age, because they make more monthly payments before they use them. Although the monthly premium probably goes up as the costs rise with inflation, there may be some savings hidden in applying an earlier payment stream at a lower rate. That's called "present value" accounting, but like just about all accounting, its unspoken advantages and disadvantages contain a gamble on unknown future inflation.

In the other common financial arrangement, you pay as you go, when and only if you actually use the assisted living quarters. Because of the likely limit to resources, there is usually an attached agreement to garnishee the initial entrance deposit if available funds prove insufficient. The one thing which won't happen is being thrown out in the snow for non-payment; there's a law prohibiting that. Bigger apartments with large initial returnable deposits are of course better off paying list prices. Those with smaller apartments may have smaller deposits, and favor payment by a percent withdrawal. Some places haven't thought this through and offer no choice. In that case, more attention should be paid to those list prices and the percentage markup from audited cost. Better still is to have a free choice of both options, with cost transparency.

The remaining choice is between two CCRCs with differing options, made at the time you enter. The Obamacare fuss has made a lot of people acquainted with "adverse risk selection", which is largely based on the idea that an individual has a better idea of his health future than an institution does since that includes family history as well as earlier health experiences. But in general, a young healthy person is going to live longer without needing assisted living than an old geezer who going to need it pretty soon. A hidden adverse incentive is created for younger healthier people to set the choice aside, and come back in ten years, providing they remain alert to the underlying reason the monthly fee is then somewhat higher than in some competitive CCRC. At the far end of the age spectrum, an incentive is created to go into assisted living quarters a little earlier in life, generally regarded as an undesirable choice.

All this financial balancing act can seem pretty overwhelming to an elderly person who isn't entirely comfortable with the CCRC idea in the first place. Rest assured that everything has to be paid for somehow, and after you die you won't care what choice has been made. If you trust the institution to have your best interests in mind, the only consideration of real importance is whether your money will last you out. The institution cares about that even more than you do, so while they aren't likely to offer unrealistically bargain choices, they may offer a few which are too costly.

America has had a ninety-year romance with insurance because it is so comforting to be secure and oblivious to finances. This is just another example of the struggle between the search for a security, and the struggle to devise ways to pay for it. While no one can be positive about it, we're all in this together.

Heavenly House

|

| Father Divine House |

While prosperous people, on deciding to enter a retirement community, are often heard to say they are tired of managing a big house, it can also be noticed that people who get the foreign travel bug usually drift around to see the palaces, castles, and estates of kings and emperors. The king's bathroom plumbing is a stop on most tours. Places like Buckingham Palace, the Vatican, the Temples of Karnak, Fortresses of Mogul Conquerors of India, or similar places in Cambodia, are all vast looming piles of stone dedicated to the memory of departed leaders who Had it All. That's probably all you need know, to understand that Americans who have it all tend to build huge show places, too. A great many do discover the castles to become just too much bother. Safe protection and privacy are somewhat separate issues, reasons given for putting up with a big place past the time the thrill has worn off. Perhaps such jaded feelings appear at the end of the wealth cycle. Nevertheless with enough affluence, if you had unlimited money and inclination, where around Philadelphia would you put a dream palace, one built for a modern Maharajah? Answer: close to Conshohocken.

|

| The Philadelphia Country Club |

The Schuylkill takes a sharp bend at Conshohocken because it flows around a big cliff on the west side of the river. It was there the White Steel Company built the first wire suspension bridge in the world, as distinguished from cable (twisted wire) suspension bridges invented by Roebling at Trenton. The bridge was swept away by a flood, the steel mill replaced by the Alan J. Wood Steel Company. Alan Wood prospered mightily, and built his mansion ("Woodmont") on 75 acres on the top of the big rock on the west side of the Schuylkill, in such a way he could watch the smoke rising from his factory down below at the foot of the cliff. The Philadelphia Country Club is across the road from Alan Wood's mansion, with fairways clinging to the cliffs, a Gun Club for trap shooters who want to aim away from houses and toward mountainsides, and a cliff-top road leading straight for Gladwyne between dozens of mansions with five-acre lots. Down the hill, however, rocky projections force the road to funnel into a winding crooked road which ends up near the filling stations of Conshohocken, passing ancient farm structures on the way. Railroads and expressways tend to fill the valley, the old White bridge is gone, and two distinct cultures are within a few hundred oblivious yards of each other. To the west stretches the Main Line, now filled with houses almost as large as the mansion, but air-conditioned and filled with other modern amenities. Seventy acres of a lawn is nice, but it's a lot of grass to cut.

The Alan Wood Steel Company had a hard time in 1929, recovered somewhat after World War II, and then declined to the point where Lukens and Phoenix Steel took over. And then Indians from India took over the lot, forming part of the largest steel complex in the world, now headquartered abroad. In 1952, one of Father Divine's religious followers named John Devoute gave Father the Wood mansion; which then became the new headquarters of his religious sect. He died in 1965 but Mother Divine still lives there in stately and tasteful semi-seclusion. The grounds of the estate are beautifully tended by various of the twenty-five attendants of Mother. Father's mausoleum is near the house.

|

| Father and Mother Divine |

The house itself is patterned after Biltmore in Asheville, NC, although perhaps only a quarter as large. Just inside its portecachier, the oak-paneled living room has a ceiling 45 feet high, and many oriental rugs. There is a music room, off to the side of which is Father's former office, bearing a strong resemblance to the Oval Office in the White House in Washington. As planned, the living room window looks down the valley to the site of the old steel mills, although when the trees are leafed out it may be difficult to see. The dining table probably seats forty people, although the paneled dining room was fitted with electronics and used to broadcast sermons to religious adherents across the country. In the living room are testimonies to the many who seemed to rise from the dead, or who had their blinded sight restored, or who were crippled but enabled to walk. The attendants take visitors on tours, but Mother Divine likes to meet them, coming down the sweeping staircase without noticeably showing her age. The greeting of "Peace" replaces the usual "hello" and "goodbye".

At one time, the Religion housed a large number of single women in several hotels, and the invested proceeds of their work as domestics still supports the Religion. The religion frowned on gambling, drinking, smoking, and sex. However, celibacy inevitably leads to a decline of numbers, particularly evident since the death of the founder.

Ageing Owners, Ageing Property

|

| Kiyohiko Nishimura |

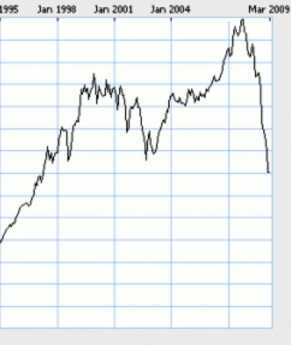

Kiyohiko Nishimura is currently the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), and as such is expected to have wise things to say about finances, as indeed he does. Japan has a far older culture than the United States, and a botanical uniqueness growing out of the glaciers avoiding it, many thousands of years ago. But its latitude is approximately the same as ours, and its modern culture is affected by the deliberate effort of the Emperor to westernize the nation, following its "opening up" by our own Commodore Matthew Perry in 1852. Perhaps a more important relationship between the two cultures for present purposes is that Japan has been suffering from the current deep recession for fourteen years longer than we have. We don't want to repeat that performance, but we can certainly learn from it.

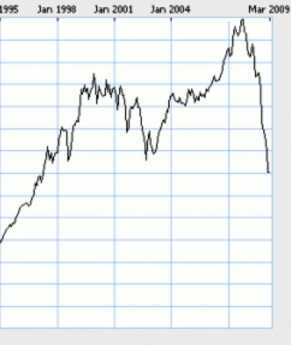

Mr. Nishimura lays great stress on the aging of the Japanese population because, in all nations, houses are mainly purchased by young newly-weds, and sold by that same generation years later as they prepare to retire. If a nation has an elderly population, it can expect a general lowering of house prices someday, reflecting too many sellers leaving the market at the same time. The buyers of those houses are competing with other young people, so the simultaneous bulges and dips of the population at later stages combine to have major effects on housing prices. At the moment, younger couples are having fewer children as a result of women postponing the first one. Nishimura goes on to reflect that something like the same is true of stocks and bonds, although at age levels five or ten years later. One implication is that retirement of our own World War II baby boom is about to depress American home prices, which will likely stay lower for 10-20 more years. Furthermore, our stock market will have a similar effect, stretching the depression out by as much as 5-15 years. The Japanese stock market has been a gloomy place to be during the past fifteen years, and by these lights might continue in the doldrums for another five or so. Meanwhile, our own situation predicts an additional generation of struggle while Japan is recovering. It's best not to apply these ideas too closely, of course, but surely somebody in our government ought to dig around in the data, at least telling us why we ain't goin' to repeat this pattern. Please.

Perhaps because they eat so much rice and fish, the Japanese already have a longer life expectancy than Americans do, but in terms of outliving your assets, that's not wholly advantageous, the way a love of golf might be. The best our nation might be able to do is to examine some of our premises about housing construction. In Kyoto, most houses were built with paper walls, for example.

|

| Commodore Matthew Perry and Japan |

The house walls of the town of Kyoto were in fact made of waxed paper, which seems to work remarkably well. While no one now advocates going quite that far, we might think a second time about building the big hulking masonry houses so favored in our affluent suburbs. Such cumbersome building materials almost dictate custom building and strongly discourage mass production. How likely are such fortresses to survive in the real estate markets of fifty years from now? Judging from my home town, not too well. Haddonfield boasts it has been around since 1701, and there are at most three or four of its houses which have survived that long. We favor great hulking Victorian frame houses, with a good many bedrooms unoccupied, and high drafty ceilings, very large window openings and little original insulation. The heating arrangements have gone from fireplaces to coal furnaces, to oil, and lately to natural gas. The meter reader who checks my consumption every month tells me that almost all the houses now have gas heat, so almost all the houses are using their second or third heating plant, along with their eighth or tenth roof, and thirty coats of paint. This kind of maintenance is not prohibitively expensive, but just wait until the plumbing starts to go, and leak, and freeze, with attendant plastering, carpentry, and painting. Our schools and transportation are excellent, so we have location, location, location. But when the plumbing, heating, and roofing start to require financial infusions all at once, you get tear-downs. A tear-down is a new house in which a specialist builder buys the old house, tears it down, and looks for a buyer to commission the new house on an old plot of land. Right now, there appear to be six or eight such Haddonfield houses, torn down and looking for a buyer to commission a new house on that location, location. If we repeat the Japanese experience, there will be some unhappy people, somewhere. And that will include the neighbors like me, who generally do not relish languishing vacant lots next door, but fear what the new one will be like.

|

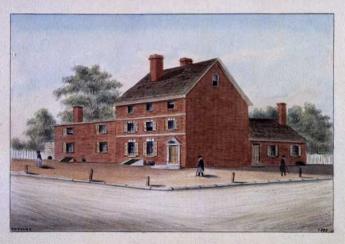

| Greenfield Hall |

The thought has to occur to somebody that building the whole town of less substantial materials in the first place would be worth investigation, replacing the houses every forty years when the major stuff wears out. At the present, when a town of several thousand houses has five or six tear-downs, the neighbors would not tolerate replacing tear-downs with insubstantial cardboard boxes. Seeing what has happened to inner-city school systems, the neighbors would be uneasy about "affordable housing" built in place of stately old Homes of Pride. In time, that might lead to a deterioration of one of the two pillars of location, location -- the schools -- and hence to a massive loss of asset value. And yet when those houses empty out the school children, leaving only retirees in place, the schools will not be worth much to the owners or in time to anybody else. There's an unfortunate tendency for local political control to migrate into the hands of local real estate brokers, so you had better be sure any bright new proposal is tightly buttressed with facts.

The only real hope for evolution in this obsolete system may lie in the schools of architecture, strengthened perhaps by some research grants. Countless World Fairs have displayed the proud products of their imaginative thinking, but mostly to no avail. Perhaps the ideas are not yet ripe, but since it would take more than a generation to create a useful demonstration project of whatever does become ripe for decision, let's start thinking about some innovative suburban designs, right now.

Labyrinth, Episcopalian Version

|

| Reverend Diana Carroll |

The Reverend Diana Carroll, Assistant Rector of Holy Trinity Church on Rittenhouse Square, recently addressed the Right Angle Club about the labyrinth to be found there. The fact is, it is there because she put it there, where it is open to the public on Saturday afternoon a month. There are half a dozen other labyrinths in Philadelphia Churches, mostly forgotten, so this is a revival of a custom rather than the invention of one. St. Asaph's on City Line Avenue, St. Stephen's at 10th and Market and a few others have them, most neglected and forgotten. Reverend Carroll admits to importing the tradition to Holy Trinity, persuading everybody in charge to nurture it, and setting aside one Saturday afternoon for the public to visit each month. Labyrinths differ in their design; this one copies the design within Chartres Cathedral in France. In England, labyrinths are much more popular and have other designs.

|

| Labyrinth |

Contrary to popular belief, a labyrinth only has one entrance, which is also its only exit. The visitor goes in, goes round and round and comes to a dead end, and then goes back out the same way. There's no great problem about getting lost; the confusing puzzles of ancient lore are not labyrinths, they are mazes. Whether with walls or simply lines on the floor, labyrinths are designed for meditation and symbolism. It's possible to bump into other people on the way out, it's possible to be struck by the symbolism of reaching the center of things, it's possible to imagine the human condition of getting into things and then getting yourself out. Diana Carroll says the labyrinth evokes the image of feminism to her, entering or leaving the uterus. That thought might not have occurred to everyone else, but an agreement isn't central to appreciating labyrinths.

The Nazca lines, best seen from an airplane over Chile, evoked the image of labyrinths to several Right Angle members. Those lines are a couple of thousand years old, in a decidedly non-Christian environment at the time. Forty-five centuries B.C. could safely be judged to precede Christianity, so it becomes clear that this concept is discontinuous, popping up in many minds in many circumstances. Some theologians might well contend this proves that meditation labyrinths are therefore not part of any fixed religious doctrine. But others, with equal justice, might say it proves that labyrinths are part of the essential nature of contemplative man. Or as in Reverend Carroll's case, woman.

Children's Scholarship Fund of Philadelphia (2)

Because the Right Angle Club makes donations to the Children's Scholarship Fund, representatives are asked to come discuss it with us from time to time. We recently had such a visit, resulting in a growing understanding of what the fund accomplishes. Briefly stated, their scholarship winners have a 95% record of graduating from high school and a 90% record of going to college. That compares very favorably with the average Philadelphia public school enrollee, who only achieves a 50% record of graduation.

That's got to be a good record, achieved by selecting the scholarship winners by random lottery; obviously, that's better still. It's not quite random, however, because the siblings from a winner's family are also awarded a scholarship. Let's repeat: the winners are not selected because of talent, IQ or achievement test. Nor are they followed, to see if they actually go to school or do their homework. Therefore, these children are definitely not selected because of either merit or diligence. They are just poor kids from Philadelphia, randomly selected by lottery. So what accounts for their markedly superior record of graduation and admission to college? It just about has to be related to either the parents or the school, and mostly it seems to be the quality of the school.

The parents have to be sufficiently motivated to contribute up to $500 yearly co-payment because that accounts for about 20% of the extra cost. A variety of other community sources account for 40%, and 40% is matched by the generous donor and originator of the idea. When the alternative for a poor family is free public school, a $500 cost really is an incentive to get something back for the money.

But most likely the main difference in outcome is due to the excellence and effort of the school. About two hundred private schools in Philadelphia are carefully selected as eligible participants, and of course, there is the invisible threat of withdrawing schools from the list if things don't work out. It's thus pretty hard to escape giving sole credit to the excellence of the teachers and schools when the contribution of the parents is mostly to demand that the students submit to it. So, like it or lump it, this scholarship fund is a social experiment in whether inner-city academic performance will improve if you improve the schools, and essentially do nothing else. And raising the performance from 50% failure to nearly 100% success certainly emerges almost totally as an achievement of a better school system. When the failing public school system compares so poorly while spending more money, the point is proven to most people. Note to politicians: fix the $#@&^# schools, and promptly.

With this point so definitively made, it is indeed possible that some of the ideas of the originator were a little off the mark. It is commonly argued by opponents of school vouchers that merit promotion of the students, or merit-based scholarships, or the creation of centers of excellence all have the potential for siphoning off the best students, thus worsening the remaining academic environment, the incentives for the teachers, and the discipline -- for everybody else. This experimental program dramatically proves that any such effects are overwhelmed by improving the schools in inexpensive ways. Most ambitious parents are already determined to move their children to better schools if they can find them, no matter what is done -- or not done -- to help substandard pupils; the day of bewildered immigrant rural peasants arriving on our shores is over.

Fixing the elementary schools is thus exposed as a purely political problem; kick out the politicians with the unions they are protecting, and the job is nearly done. After all, children below the fourth grade are mostly sweet little confections, ready to flower if you remove impediments. The inner-city schools from fourth to twelfth are a somewhat more difficult issue, mostly because of their hormone content. The home environment is probably more important at that age, and changing whole cultures is very difficult. But the Philadelphia School System was once a source of great pride, and the Philadelphia Catholic School System was once the best in America. Somehow, the suburban secondary school system is falling down on its job as an unchallenged exemplar, coasting on invidious comparisons with the inner city. It's high time the suburban schools stopped preening themselves and stopped coddling the outrageous behavior and low academic standards the situation promotes in both students and teachers. Let each one of these places adopt a sister school in the inner city and help it out. The college admissions committees could help this happen a little by shifting their preferences to suburban private schools, unless or until the suburban high schools pull up their socks.

From time to time, someone angry about education expresses the wish for a deep economic depression or a massive world war or both. Please. What's needed here is competition.

Adrift With The Living Constitution

.jpg)

|

| Senator Joe Sestak |

Former Congressman Joe Sestak visited the Franklin Inn Club recently, describing his experiences with the Tea Party movement. Since Senator Patrick Toomey, the man who defeated him in the 2010 election, is mostly a Libertarian, and Senator Arlen Specter who also lost has switched parties twice, all three candidates in the Pennsylvania senatorial election displayed major independence from party dominance, although in different ways. Ordinarily, gerrymandering and political machine politics result in a great many "safe" seats, where a representative or a Senator has more to fear from rivals in his own party than from his opposition in the other party; this year, things seem to be changing in our area. Pennsylvania is somehow in the vanguard of a major national shift in party politics, although it is unclear whether a third party is about to emerge, or whether the nature of the two party system is about to change in some other way.

For his part, Joe Sestak (formerly D. Representative from Delaware County) had won the Democratic senatorial nomination against the wishes of the party leaders, who had previously promised the nomination to incumbent Senator Specter in reward for Specter's switching from the Republican to Democratic party. For Vice-Admiral Sestak, USN (Ret.) it naturally stings a little that he won the nomination without leadership support, but still came reasonably close to winning the general election without much enthusiasm within his party. He clearly believes he would have beaten Toomey if the party leaders had supported him. It rather looks as though the Democratic party leadership would rather lose the election to the Republicans than lose control of nominations, which are their real source of power. Controlling nominations is largely a process of persuading unwelcome contenders to drop out of the contest. Sestak is, therefore, making a large number of thank-you visits after the election, and clearly has his ears open for signs of what the wandering electorate might think of his future candidacy.

America clearly prefers a two-party system to both the dictatorial tendencies of a one-party system, as well as to European multi-party arrangements, such as run-offs or coalitions. A two-party system blunts the edges of extreme partisanship, eventually moving toward moderate candidates in the middle, in order to win a winner-take-all election. Therefore, our winner-take-all rules are the enforcement mechanism for a two-party system. Our deals and bargains are made in advance of the election, where the public can express an opinion. In multi-party systems, the deals are made after the election where the public can't see what's going on, and such arrangements are historically unstable, sometimes resulting in a victory by a minority fringe with violently unpopular policies. In our system, a new third-party mainly serves as a mechanism for breaking up one of the major parties, to reformulate it as a two-party system with different composition. Proportional representation is defended by European politicians as something which promotes "fairness". Unfortunately, it's pretty hard to find anything in politics anywhere which is sincerely devoted to fairness.

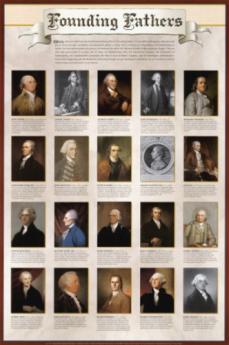

Going far back in history one of the great theorists of legislative politics was the Roman Senator Pliny the Younger, who wrote books in Latin about how to manipulate a voting system. For him, parties were only temporary working arrangements about individual issues, a situation where he recommended: "insincere voting" as a method for winning a vote even if you lacked a majority in favor of it. Over the centuries, other forms of party coalitions have emerged in nations attempting to make democracy workable. Indeed, a "republic" itself can be seen as a mechanism devised for retaining popular control in an electorate grown too large for the chaos and unworkability of pure town hall democracy. A republic is a democracy which has been somewhat modified to make it workable. Our founding fathers knew this from personal experience, and never really considered pure democracy even in the Eighteenth century.

|

| Senator Specter |