Related Topics

American Finance After Robert Morris

Robert Morris can be fairly said to have made the American Revolution possible.

Old Age, Re-designed

A grumpy analysis of future trends from a member of the Grumpy Generation.

Right Angle Club 2011

As long as there is anything to say about Philadelphia, the Right Angle Club will search it out, and say it.

Great Depression (1929-1939)

New topic 2012-08-29 11:32:11 description

Brave New World

Let me put some emphasis on what I consider the most revolutionary change of a current lifetime. Nothing to do with Hitler, Stalin or Mao; or jet planes, television, and computers. Or even the rise of the impoverished underdeveloped world. To me, the most revolutionary change of the past century has been the extension of the average life span, by thirty or forty extra years, depending on where you happen to live. I'm proud to be a member of the profession at the center of it.

|

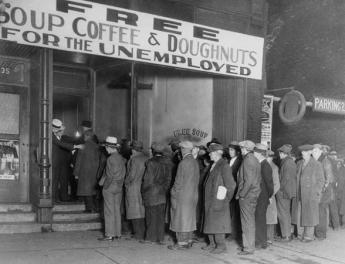

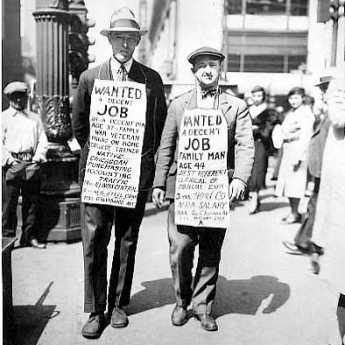

| The Great Depression |

Right in the middle of this revolution, the Great Depression of the Thirties convinced a great many people there were not enough jobs to go around. The Union movement, as we say, or the Socialist movement as they come right out and call it in Europe, adopted a general thesis that a limited number of jobs should be shared equally so everyone could have a chance at them. Child labor should be condemned, and those occupying "decent" jobs should retire early. A number of lesser agitations of the Thirties have the same sound to them: piecework was a bad thing because it encouraged women to work at home, depressing prevailing wages. Home offices are condemned by the IRS for similar reasons. Automation and efficiency generally were resisted. Since I persist in the notion that efficiency is almost always a very good thing, these anti-efficiency campaigns sound like more hidden agendas to spread the supposedly limited amount of available work. But all of this is a left-over idea from the great 19th Century migration from the farm to the industrial city, where job creation generally requires a manager, some risk capital, and an atmosphere of creative destruction -- all of which can seem threatening, except for the seemingly obvious evidence of their usefulness. If you have grown up hating managers and investors, it's painful to be told your only alternative is to spend a lifetime working as their subordinates.

While some people understandably oppose the forward march of efficiency, few want to live shorter lives. Even victims of self-inflicted conditions generally drawback when the consequences become fully visible. Mistaking a lifetime of paychecks for a lifetime of work, they wish to extend one without extending the other. That's called inflation, it seldom creates wealth, usually destroys it. It's vaguely possible that alcoholism, unsafe sex, and recreational drug consumption are efforts to end it all, but let's be charitable. More likely those confused souls are just that, confused.

And that's where matters seemed to rest until recently. People didn't specifically ask for this extra longevity, and while often willing to risk it, are seldom willing to lose it. My own elderly generation can start to see signs that a protracted retirement can eventually lead to running out of money, so there is plenty of need for an open mind, experimentation, and innovation about making retirement a more productive period of life.

|

| Great Depression of the Thirties |

I heard some college kids talking; kids do talk a lot. The proposition argued was essential as follows: Instead of adding a few years to your retirement, when you are feeble and useless, why not deliberately offer kids an extended period of loafing, when health is good, love-making is vigorous, and the ability to endure the debilitating effects of recreation is still strong? A grungy lifestyle is more tolerable for someone who is thirty than for the same person at seventy-seven so it could be an overall cheaper lifetime. An additional five years of pizza for breakfast; sounds heavenly.

Boys and girls react to this proposal in biologically different ways, of course. Boys don't have the same biological clock, telling them they better start their families while they still can. Raising little children is strenuous, particularly during time shared with continuing education, starting a career, or finding a husband. Getting a divorce is also a surprisingly debilitating distraction, seldom recommended by those who have experienced it. The males have an easier time loafing; so why not return to the customs of a century ago, when girls planned to get married during the same summer they graduated from college. Because a big part of that tradition was "Don't get married until your ship comes in," it tended to define an eligible male as someone thirty years old. Unfortunately, that interferes with another new trend, the buddy system.

Most girls now expect to go to college, and colleges have mostly become coeducational to accommodate the expanded market. Hand in hand kids stroll the lawns of academe, more like siblings than lovers. The faculty marvels at this phenomenon, which to them seems like an unfamiliar mixture of incest and promiscuity, but it does not quite follow the rules of either entertainment. Since the buddy system is probably connected to the increasing divorce rate, universally condemned as a bad thing, it may further evolve into something else. It's been suggested men should get over their traditional reluctance to raise someone else's children. Now that's an idea which is going to take some time getting used to.

So, all in all, let's swallow our generational pride and seriously consider whether we just ought to do what our grandparents did. Men should wait until thirty to get married, while women should marry at twenty; simple. It forces feminists to admit that in one sense they are inferior to men, so declare victory and ascribe it to an innate superiority of women. It also calls the pseudo-sibling pairings of school children into question, which is essentially the only thing new in this whole business. It's probably a lot of fun, but it exacts too high a social price.

Originally published: Monday, July 25, 2011; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 15, 2019