1 Volumes

Philadelphia: Decline and Fall (1900-2060)

The world's richest industrial city in 1900, was defeated and dejected by 1950. Why? Digby Baltzell blamed it on the Quakers. Others blame the Erie Canal, and Andrew Jackson, or maybe Martin van Buren. Some say the city-county consolidation of 1858. Others blame the unions. We rather favor the decline of family business and the rise of the modern corporation in its place.

Great Depression (1929-1939)

New topic 2012-08-29 11:32:11 description

Warnings of Impending Trouble for the PRR

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

The success of an excellent book, The Wreck of the Penn Central, has stamped the decline of the railroad industry with the problems of the merger of the New York Central and Pennsylvania railroads. There definitely was mismanagement of that merger, which quite possibly should never have occurred, and unions surely did contribute to excessive costs of running the merged lines. Government regulation was definitely slanted toward maintaining uneconomic railroad capacity for political reasons and tangled the struggling corporations in mountains of red tape which prevented timely responses to problems. And the tax-subsidized highways and airlines tilted the balance against the fair competition with a railroad industry which had long been unaccustomed to the competition. All of these difficulties prevented the railroads from meeting new challenges, and like wolves around a wounded caribou brought it to the ground.

|

| Smoke Signals |

But there is a larger picture explaining the toppling of the railroads, particularly when the causes of Philadelphia's industrial decline are the focus of examination. The whole fabric of Philadelphia's economy was interwoven with the national dominance of the Pennsylvania Rail Road, which was in turn intertwined with the national importance of coal and steel production, a creation in the 19th Century of J. Edgar Thomson. It was not one heavy industry which disappeared, it was three of them. It was not just Philadelphia which faded, it was the whole "Rust Belt" from Philadelphia to St. Louis. Baltimore and Cleveland declined even more than Philadelphia, for example. At the end of World War II, this was the only region of heavy industry still standing in the whole world; for a while, its uncompetitive profits were astounding. Unionized labor made amazing gains in wages and power, management grew fat and slack; the government made sure it was so, but competitive industries had an easy time lobbying for that outcome. As late as 1968, PRR shares which were to fall to $15 within ten years were selling for $80, and an old joke was current. A mythically representative Philadelphia father was said to advise his daughters, "Sell your body if you must, but never, never, sell your Pennsy stock." All of this public pressure combined to encourage unions and government to force management to take the easy way out huge deferred maintenance during ten years of depression and five more years of war had built up. And meanwhile, the biggest deferred problem of all was allowed to build up. Every congressman for decades had demanded unprofitable rail service for his district, insisting the trains make too many unprofitable stops along the way, and at night, and on weekends. Every business must adjust capacity to changing customer demands, that's just business, but an inability to adjust capacity to changing circumstances is what's fatal.

Brave New World

Let me put some emphasis on what I consider the most revolutionary change of a current lifetime. Nothing to do with Hitler, Stalin or Mao; or jet planes, television, and computers. Or even the rise of the impoverished underdeveloped world. To me, the most revolutionary change of the past century has been the extension of the average life span, by thirty or forty extra years, depending on where you happen to live. I'm proud to be a member of the profession at the center of it.

|

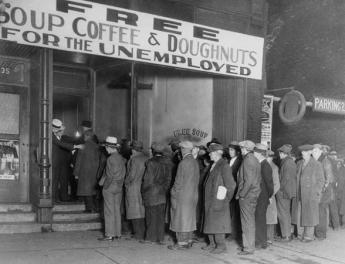

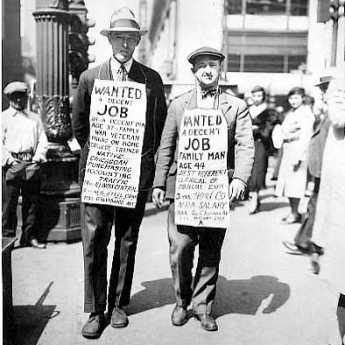

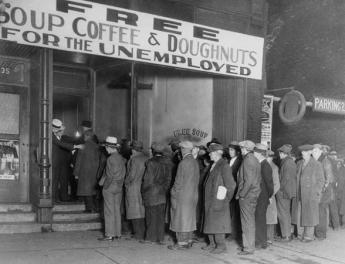

| The Great Depression |

Right in the middle of this revolution, the Great Depression of the Thirties convinced a great many people there were not enough jobs to go around. The Union movement, as we say, or the Socialist movement as they come right out and call it in Europe, adopted a general thesis that a limited number of jobs should be shared equally so everyone could have a chance at them. Child labor should be condemned, and those occupying "decent" jobs should retire early. A number of lesser agitations of the Thirties have the same sound to them: piecework was a bad thing because it encouraged women to work at home, depressing prevailing wages. Home offices are condemned by the IRS for similar reasons. Automation and efficiency generally were resisted. Since I persist in the notion that efficiency is almost always a very good thing, these anti-efficiency campaigns sound like more hidden agendas to spread the supposedly limited amount of available work. But all of this is a left-over idea from the great 19th Century migration from the farm to the industrial city, where job creation generally requires a manager, some risk capital, and an atmosphere of creative destruction -- all of which can seem threatening, except for the seemingly obvious evidence of their usefulness. If you have grown up hating managers and investors, it's painful to be told your only alternative is to spend a lifetime working as their subordinates.

While some people understandably oppose the forward march of efficiency, few want to live shorter lives. Even victims of self-inflicted conditions generally drawback when the consequences become fully visible. Mistaking a lifetime of paychecks for a lifetime of work, they wish to extend one without extending the other. That's called inflation, it seldom creates wealth, usually destroys it. It's vaguely possible that alcoholism, unsafe sex, and recreational drug consumption are efforts to end it all, but let's be charitable. More likely those confused souls are just that, confused.

And that's where matters seemed to rest until recently. People didn't specifically ask for this extra longevity, and while often willing to risk it, are seldom willing to lose it. My own elderly generation can start to see signs that a protracted retirement can eventually lead to running out of money, so there is plenty of need for an open mind, experimentation, and innovation about making retirement a more productive period of life.

|

| Great Depression of the Thirties |

I heard some college kids talking; kids do talk a lot. The proposition argued was essential as follows: Instead of adding a few years to your retirement, when you are feeble and useless, why not deliberately offer kids an extended period of loafing, when health is good, love-making is vigorous, and the ability to endure the debilitating effects of recreation is still strong? A grungy lifestyle is more tolerable for someone who is thirty than for the same person at seventy-seven so it could be an overall cheaper lifetime. An additional five years of pizza for breakfast; sounds heavenly.

Boys and girls react to this proposal in biologically different ways, of course. Boys don't have the same biological clock, telling them they better start their families while they still can. Raising little children is strenuous, particularly during time shared with continuing education, starting a career, or finding a husband. Getting a divorce is also a surprisingly debilitating distraction, seldom recommended by those who have experienced it. The males have an easier time loafing; so why not return to the customs of a century ago, when girls planned to get married during the same summer they graduated from college. Because a big part of that tradition was "Don't get married until your ship comes in," it tended to define an eligible male as someone thirty years old. Unfortunately, that interferes with another new trend, the buddy system.

Most girls now expect to go to college, and colleges have mostly become coeducational to accommodate the expanded market. Hand in hand kids stroll the lawns of academe, more like siblings than lovers. The faculty marvels at this phenomenon, which to them seems like an unfamiliar mixture of incest and promiscuity, but it does not quite follow the rules of either entertainment. Since the buddy system is probably connected to the increasing divorce rate, universally condemned as a bad thing, it may further evolve into something else. It's been suggested men should get over their traditional reluctance to raise someone else's children. Now that's an idea which is going to take some time getting used to.

So, all in all, let's swallow our generational pride and seriously consider whether we just ought to do what our grandparents did. Men should wait until thirty to get married, while women should marry at twenty; simple. It forces feminists to admit that in one sense they are inferior to men, so declare victory and ascribe it to an innate superiority of women. It also calls the pseudo-sibling pairings of school children into question, which is essentially the only thing new in this whole business. It's probably a lot of fun, but it exacts too high a social price.

Falstaff Without Prince Hal

|

| W. C. Fields |

William Claude Dukenfield was born in Philadelphia in 1880, the eldest of five children of Cockney immigrant parents. He spent four years in school, was roundly abused by his parents, and left home at the age of 11 after being hit on the head with a shovel. During a self-taught adolescence, W.C. Fields slept in jail many times but learned to be such an accomplished pool player and juggler that he became the toast of Vaudeville. When silent movies made their appearance, he was successful in a second career, and then again when talkies came along. He was one of the ten or twenty most famous actors of the golden age of motion pictures, and, following the legend of the Great Depression, lived in a Hollywood mansion in great style.

Although he was a great natural comic, and had a sharp piercing wit, the image he was destined to project was that of the great alcoholic reprobate, during the period of national Prohibition. It was wicked that he was so lovable with his unashamed praise of gin martinis. And, of course, his outrageous defiance was a very thinly disguised symbolism of the growing public feeling that perhaps the Volstead Act had been a mistake.

It has not been made clear whether his repeated insults aimed at Philadelphia were fundamentally bitter or fundamentally just rough expressions of affection for a home town that never welcomed him. He constantly insulted just about everything and everybody. If it was a bitter war, he probably won it. His jibes and caricatures of the hometown have endured, long after his death in 1946.

"I once spent a year in Philadelphia. I think it was on a Sunday."

" I can love almost anything, except children and small dogs."

Hangman: "Any last words?" W.C.: "Yes, I'd like to see Paris before I die. (Pause) Philadelphia will do."

His famous recommendation for an epitaph: " On the whole, I'd rather be in Philadelphia."

Show Biz Image: Hepburn, Rogers, Kelly

A fair lady's image depends, Bernard Shaw told us, not on how she acts, but on how she is treated. The case in point is a beautiful Main Line heiress in The Philadelphia Story, who can choose any man she wants. What she cannot do, is escape grief for a wrong choice.

When Broadway and Hollywood paint your image, not believing your own press releases takes strength. Toward the end of the Great Depression around 1938, show business turned full and nasty attention to Philadelphia high society. Earlier, while author Christopher Morley was at Haverford College, Katharine Hepburn at Bryn Mawr College, and Grace Kelly at school on Schoolhouse Lane, Hollywood had picked up just enough authentic detail to be dangerous. Kitty Foyle and The Philadelphia Story are two fairly accurate snapshots of a complex society, but one cannot be fully understood without the other. Indeed, the real-life trivialities of Howard Hughes, Katharine Hepburn, Grace Kelly, and Ginger Rogers sharpen the outlines of the graceful gentlefolk they attempted to portray.

In 1938, Hepburn was a smash hit on Broadway with Philip Barry's Philadelphia Story, which essentially tells of the agonized turmoil of a Main Line princess, facing a three-way choice between a charming but worthless blue-blood, a self-made dullard, and a poor but noble New York magazine writer. (Just guess who the author was rooting for.) In real life, of course, Ms. Hepburn chose to spend four years with movie producer Howard Hughes the dare-devil Texan with a hundred starlets in his bedroom. Most of her competitors wanted a movie contract and/or a diamond bracelet, but Katy wanted the movie rights for Philadelphia Story, which Howard readily bought for her. Although other actresses played the role, she made herself into the image of a Philadelphia heiress, thereby nudging that Main Line image toward her own. At the time the image did not include much mention of Howard Hughes or actor Spencer Tracy, another long-time companion.

|

| Ginger Rogers |

Meanwhile, Ginger Rogers, who was also engaged to Howard Hughes at one point, was making a great name for herself as the star of Christopher Morley's Kitty Foyle. Morley's Haverford experience taught him somewhat more respect for the Philadelphia Gentleman than Barry ever had, while his experience at the Curtis Publishing Company also made him appreciate the smart and plain-spoken Philadelphia girls from working-class districts. Highborn Philadelphia women are only sketchily imagined by Morley, except they somehow fail to appeal to his manly fictional cricket-player from the Main Line.

As matters turned out, Katy lost to Kitty. Although Hepburn was surely the more talented actress, eventually winning five Academy Awards, Ginger Rogers walked away with the 1940 Oscar for her interpretation of a working-class Philadelphia lady. Either way it turned out, of course, Howard Hughes was bound to be a happy fellow.

|

| Grace Kelly |

And yes, in 1956 Grace Kelly was the star of High Society, a renamed version of the Philadelphia Story for which, remember, Katherine Hepburn still controlled the rights. The film was a mediocre performance, just a little short of embarrassing. But however inexact all three of these portrayals may have been, there is little doubt that Philadelphia society moved a bit in their direction, involuntarily living up to an image created by three observers who seemed to their own observers to retain hostility traceable to their own undefined turmoils.

Philip Barry stacks the deck somewhat, portraying the leading lady as movie audiences during the Depression were likely to fantasize, indulging a luxury only a rich girl would supposedly be careless about. She rejects the colorless rich suitor out of hand. But while her remaining choice between a charming magazine writer and a charming playboy is made to seem a closer call, it really never makes our Philadelphia Cleopatra hesitate very long. In the single editorial comment, the play's author permits himself, is tucked the snarl, "She's a lifelong spinster, no matter how many times married." That's New York talking. Bitter, bitter.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890 | Amazon |

Rise and Fall of Life Insurance

|

| Hammurabi Code |

While it is possible to see traces of the origin of insurance all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia, insurance of a currently recognizable form began around 1500, with maritime insurance creating risk pools for ships at sea. Eventually, insuring the life of a ship and ensuring the life of a person did not seem greatly different in principle; sooner or later everyone dies, but in those days sooner or later most ships sank. From the records of such pooling efforts, we can see that a sailor in colonial times had a 40% chance of not returning from a typical voyage. Learning this, some of the plots of Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice becomes more understandable, and the enormous wealth of successful sea captains, privateers, whalers and ship owners seems more justified by the risks they were taking. In retrospect, it seems hard to understand why anyone at all went to sea, thus why it took so long to discover America. Selling maritime insurance was a way to gamble on these risks. You might not get wet, but you were still taking big risks with your money.

Life insurance was a comparatively late arrival on the insurance scene and grew out of the experience with maritime risk pooling. The first life insurance company was the Presbyterian Ministers Fund, a Philadelphia institution if there ever was one. In essence, the church had undertaken to support the widows of ministers. Insurance tailored to the life of each minister, when pooled together, approximated the church's collective widow-support risk. Only ministers were insured by this fund, however. The Insurance Company of North America (now Cigna) seems to have been the first company to sell life insurance to all comers. That's definitely an improvement; limiting the risks to a particular occupation amounts to "adverse risk de-selection", unintentionally excluding, for example, women and blacks. On the other hand, the concept was totally new; no insurance at all would have been attempted if it had been initially impossible to limit the risk.

Insurance has since spread to many other topics, but it remains true that life insurance has one central unique feature. It is absolutely certain the customer will die, the policy will be cashed in. The uncertainty is when it will happen. After a while, it became evident that premiums would be collected until the final date, and could be invested until it happens. When the pool of customers gets large enough, there is almost perfect predictability about the average age at death, so the bigger the company the safer it should be.

There is one great potential weakness in this system, lying in the fact that the person who buys the policy and receives the assurances will not be around to complain about failures of those assurances at the time the policy is cashed in. It takes many years before public trust in such promises overcomes skepticism. The growth of life insurance was therefore slow until the Civil War suddenly demonstrated there were unpredictable risks around. Unfortunately, abuses of the system by fly-by-night companies in the last half of the Nineteenth Century led to heavy government regulation of the industry. Philadelphia's reputation for integrity rapidly expanded its dominance of insurance, but could not prevent the heavy hand of regulation from holding it down, or local taxes from driving it into other jurisdictions. State Insurance commissioners were originally charged with guarding against an insurance company going bankrupt by using unrealistic low prices to attract business. The public interest was redefined to mean low premiums, by the obscure but effective method of legally shifting the debts of a bankrupt insurer onto its surviving competitors -- neither the public nor the Legislature had to worry about it any further. In the insurance capital of the country, stockholder returns and executive salaries gradually went from too fat to too thin. Insurance companies, one by one, moved to other states or at least to other counties. It is now possible to wander through the abandoned executive suites on the top floors of the former insurance palaces and feel as though you were at Luxor, wandering through the abandoned Egyptian temples of Karnak.

To be fair about it, it is also possible to have a real estate agent take you through the former estates of life insurance entrepreneurs whose business practices amply justified some regulatory over-reaction. Plenty of old retired lawyers will be glad to tell you of the times they wrote new insurance laws for their insurance client, who just forwarded them to Harrisburg for enactment -- before the Second World War. But the destruction of this industry does no one any good, and it is surely fair to argue that excessive profits were the lesser of the two evils.

Setting the regulatory risk to one side, the life expectancy of Americans has dramatically lengthened in the past century, nearly eight years in the past fifty years. Such unpredictable reduction of risk ought to lead to increased profitability for the insurer, but it also leads the public to shift to less profitable term insurance. The young buyer can see a period of several decades of dependent children, followed by a long period of life when the death of the breadwinner is less tragic. I needed, living too long becomes a modern new concern, the outliving of accumulated savings. When the investment manager of the insurance e company is faced with a choice of more investment safety or greater investment return, he must produce a combination of both, an impossible assignment. And so, insurance business drops off as clients wander away toward more glowing promises, or at least toward promises unconstrained by the growls of a consumer-driven insurance commissioner. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, only two life insurance companies went bankrupt, so at least the old way of running these companies produced safety. The 1930s now seem a long time ago.

Northwest Rittenhouse Square

|

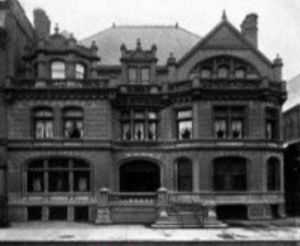

| {John Wanamaker's Mansion 2032 Walnut Street |

Market, Chestnut and Walnut Streets go right across the Schuylkill on bridges; that fact was once their glory, but now is the source of their problem. The first bridge to be built, at Market Street, was originally placed there in 1804. Placing your mansion on an important street makes you prominent, but if the street gets too busy, crowded and noisy you eventually wish you lived somewhere else. Air conditioning helps somewhat by allowing your windows to be closed all the time, but eventually, the increasing commercial value of the location gives you unwelcome neighbors. So right now the last few blocks of Chestnut and Walnut before you reach the river are pretty run down. Students from the Universities on the far side of the river make for street activity at night, but most of them head for the Eastern edge of Rittenhouse Square, where droves of them sit at sidewalk tables on a summer evening. Irreverent college kids refer to such a congregation as a meat market, but I'm only quoting them.

John Wanamaker had one of his many mansions just past the Square at 2032 Walnut, but it now is mostly an entrance to an apartment building towering above it. What now distinguishes this area most are the surviving churches.

|

| Unitarian Church |

The Unitarian Church at 22nd and Chestnut is one of Frank Furness' finest buildings and next to it is a renovated former Church of the New Jerusalem (Swedenborgian Church), now used for an advertising agency. Frank Furness won the Medal of Honor during the Civil War before he thought much about architecture. Swedenborg, for his part, founded what is known as a thinking man's religion, since Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) himself was a scientist of the first rank who might have won a Nobel Prize if there had been such a thing in his day. The Mother Church of this religion moved out to Bryn Athyn, abandoning the center city after what is reported to be a heated dispute. While the new cathedral is absolutely spectacular, the old one on Chestnut Street is still pretty fine, itself.

Across Chestnut Street is the Lutheran Church, which proves to be astonishingly large when you enter it, and it has great acoustical qualities related to the Moravian influences of the last century. Up at the NorthWest corner of Rittenhouse Square is Holy Trinity. Its minister, Phillips Brooks, wrote the words of the Christmas carol "O Little Town of Bethlehem", which are a poem of considerable merit and sophistication. Unfortunately, the need to adjust these words to music which children might single to the attachment of three different tunes of less than classic musical proportions, sometimes even less sonorous when sung simultaneously by adults who remember different tunes from their childhood. In view of the far from the peaceful scene of present-day Bethlehem, at least the message of the carol warrants recollection indeed. And, yes, the church is reddish brown in color, as most Episcopalian churches seem to be.

There once was a time when Anthony Drexel walked down Walnut Street to work every day. One can easily imagine him tipping his hat to passers-by, striding along in front of formerly elegant mansions which line the street but are now too big to maintain. This area was a place of show houses, of downtown places to hold parties during the social season, from thence fleeing to a second house in the suburbs, or in Maine, or in Europe, during the summer. The Great Depression of the 1930s forced most of these people to choose between their various residences, and because of the advent of the automobile, they mostly chose the other places, abandoning these. It was the end of the Gilded age.

For a tour of Rittenhouse Square, mentioned in this Reflection, visit Seven Tours Through Historic Philadelphia

Medical Club of Philadelphia, Appendix B, Membership

The Club grew robustly to the point where it attained a total of 1.393 members 1924 (In 1911 it had a thousand members compared to a total of forty thousand in the American Medical Association.) Exact figures are not available for all years. Some totals were taken from Annual Reports, but these figures are distorted by the fact that for many decades they continued to count persons who were two years delinquent in dues, as members. In some cases, they also counted applicants who had not paid any dues or admission fees. It was not until the 1970s that dues were collected before applicants were elected to membership.

For some years numbers were computed from records of dues & initiation fees paid. In other cases, where members were elected late in the year, their dues were credited both to the year paid and following year. Financial records are not available for some years, and in others, there simply are no records from which figures can be computed.

1893 570

1899 230

1900 313

1901 365

1902 460

1903 570

1904 644

1905 614

1906 640

1907 799

1908 846

1909 928

1910 931

1911 998

1912 1,010

1913 999

1914 1,042

1915

1916 1,107

1917 1,121

1918 1,067

1919 1,190

1920 1,211

1921 1,235

1922 1,205

1923

1924 1,393

1925 1,362

1926 1,359

1927 1,258

1928 1,329

1929 1,288

1930 1,348

1931 1,247

1932 1,159

1933 1,079

1934 982

1935 936

1936 910

1937 868

1938 821

1939 854

1940 860

1941 870

1942 767

1943 749

1944 748

1945 752

1946 765

1947 792

1948 990

1949 1,007

1950 965 (Dues increased

1951 942 from $5 to $10)

1952 958

1953 936

1954 924

1955 880

1956 876

1957 857

1958 800

1959 802

1960 799

1961 756

1962 724

1963 728

1964 703

1965 696

1966 684

1967 679

1968 671

1969 674

1970 654

1971 619

1972 629

1973 590

1974

1975 669

1976 555

1977 446 (Dues increased

1978 410 to $25)

1979 410

1980 412

1981 379

1982 387

1983 398

1984 329 (Dues increased

1985 409 to $35)

1986 390

1897 397

1988 387

1989 400

1990 398

1991 388

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |

Although Germantown Avenue has wandered northwestward from this uncertain beginning for over 300 years, up to the rising slope of the town toward Broad Street, it is now rather difficult to make out anything but industrial slum along its path which could be called historic. There is hardly any structure standing which has a colonial shape, and no Flemish bond brickwork is seen in the tumble-down buildings. When with the relief you finally approach Temple University Medical Center at Broad Street, the Fair Hill cemetery does show some effort at preservation, and a sign says that Lucretia Mott is buried there. But that's about all you could photograph without provoking suspicious stares. Here's the first of four segments of Germantown Ave., and it's a pretty sorry sight.

|

| Chew Mansion |

Crossing Broad Street, the busy intersection suggests 19th Century prosperity in its past, and on the west side of Broad, you can start to see signs of historic houses, either in colonial brickwork or grey fieldstone. The road gets steeper as you go west past Mt. Airy, where it almost brings tears to the eyes to see brave remnants of another time. George Washington lived here for a while, and the Wisters, Allens, and Chews; Grumblethorp and Wyck. The huge stone pile of the Chew Mansion glares at the imposing Upsala mansion, where British and Americans lobbed artillery at each other during the Battle of Germantown. Benjamin Chew the Chief Justice built this house as a summer retreat, to get away from Yellow Fever and such, and started the first migration to the leafy suburbs. His main house was on 3rd Street in Society Hill, next to the Powels and where George Washington stayed. At the peak of the hill in Chestnut Hill, a suburb within the city. Germantown Avenue rather abruptly goes from the relics of Germantown to the charming elegance of Chestnut Hill, but during a recession, it frays a little even there. At the very top is the mansion of the Stroud family, now in the hands of non-profits; across the road in Chestnut Hill Hospital, once the domain of the Vaux family. Then down the hill to Whitemarsh, where the British once tried to make a surprise raid on Washington's army. As you cross the county line into Montgomery County, it's conventional to start calling the Avenue, Germantown Pike. Germantown Pike was in fact created in 1687 by the Provincial government as a cart road from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. Farmers used to pay off their taxes by laboring on the dirt road, at 80 cents a day. Germantown Pike, Ridge Pike, Skippack Pike, Lancaster Pike, and others are a local reminder that Pennsylvania was always the center of turnpike popularity; that's how we thought roads should be paid for. The present governor (Rendell) hopes to sell off some better-paying turnpikes to the Arabs and Orientals, possibly imitating Rockefeller Center by buying them back and reselling them several times by outguessing the business cycle. Parenthetically, the Finance Director of another state at a cocktail party recently snarled that the purpose of privatizing state infrastructure was not to raise revenue, but to provide collateral for more state borrowing. He wasn't at a tea party, but he may soon find himself there.

From a modern perspective, the third segment of the Germantown road runs from Chestnut Hill to Plymouth Meeting, with lovely farmhouses getting swallowed up by intervening, possibly intrusive, exurbia. The township of Plymouth Meeting is a hundred years older than Montgomery County, having been built to be near a natural ford in the Schuylkill River. Norristown, a little downstream, is the first fordable point on the Schuylkill, with Pottstown making a third. Plymouth's colonial character survived a period of industrialization based on local iron and limestone, and has established several prominent schools for the surrounding area. But the construction of a substantial highway bridge attracted a large and busy shopping center. The shopping center looks as though it will eradicate the quaint historical atmosphere more effectively than industrialization ever could.

The fourth and final segment of Germantown Pike starts at the Schuylkill and goes over rolling countryside to its final destination at Perkiomenville, where it joins Ridge Pike at the edge of the Perkiomen Creek. That's an Indian name, originally Pahkehoma. Perkiomenville Tavern claims to be the oldest inn in America, although that honor is contested by another one along the Hudson River near Hyde Park. The WPA during the Great Depression constructed a large park along the Perkiomen Creek for several thousand acres of camping and fishing, so Perkiomenville has several large roadhouse restaurants and antique auctions for bored wives of the fishermen. In the V where Ridge Pike and Germantown Pike come together, a dozen or more colonial houses are tucked away in a town called Evansburg. This formerly Mennonite terminus of Germantown Pike obviously still has a lot of charm potential, and its local inhabitants are very proud of the place. But it's easy to zip past without noticing the area, which includes an 8-arch stone bridge, said shyly to be the oldest in the country. It's hard to know whether you wish more people would visit and appreciate; or whether you are happy that obscurity might permit it to survive another century or so.

|

| Chestnut Hill Hospital |

The name change of the Germantown road from Avenue to Pike is probably not precisely where the turnpike began, but it is now notable for some pretty imposing mansions, standing between the humble and even somewhat dangerous slums along Delaware, and the charmingly humble but well-preserved Mennonite villages, at the other end. It is arresting to consider the two ends, whose houses were built at the same time; only the Mennonites endure. Somewhere just beyond the Chestnut Hill mansions is an invisible line. West of that point, when you say you are going to town, you mean Pottstown. When you say you are going to the City, you mean Reading. And as for Philadelphia, well, you went there once or twice when you were young.

Bernanke's QE3: A New Titanic, or A New Bretton Woods?

|

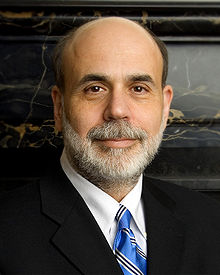

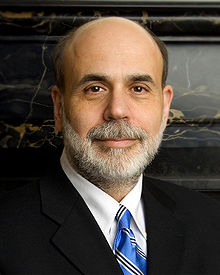

| Ben Bernanke |

Nobody likes to execute a guilty prisoner, but in finance, it is surely true that allowing bad debts to remain unresolved harms the whole economy. It makes little difference whether a bank fails to mark its debts to market, whether debts are "extended", or insolvent institutions are subsidized. Andrew Mellon once advised Herbert Hoover that he should "wring the rottenness out of the system", but that is such poor politics that even Hoover rejected it. In time, the process of "good bank, bad bank" was devised to isolate bad debts into a single institution so the rest of the economy could begin to recover. QE3 is a version of a good bank, bad bank. Unfortunately, the public is easily misled in these matters, so although all three Q's involve the Federal Reserve buying long bonds, QE1 unfroze a frozen financial marketplace (successfully), QE2 meant to stimulate the economy (unsuccessfully), but QE3 seems to have much grander ambitions. So it is unfortunate that three different activities share the same name, and still more unfortunate that name is made so mysterious. Let's forget about the first two, and concentrate on QE3.

The Federal Reserve is well along in a program of buying huge quantities of questionable long bonds and has announced it is going to keep buying huge quantities until either inflation exceeds 2.5% or unemployment falls below 6.5%. That's not exactly the same as buying every bad bond in existence, but it could come to that. Instead of letting the holders of those bonds go bankrupt, the Fed is buying the bonds out of circulation, which could rescue a great many investors. Small businesses do not ordinarily issue bonds, so there is some bias in favor of large businesses and banks, but surely not an intentional bias. The effect is to make the Federal Reserve both a good bank and a bad bank at the same time. The main difference between this and wringing the rottenness out is that bankrupt institutions cannot come back to haunt you, while in the more benign purchase of bonds, you have assumed an obligation to pay them back. When you sell them back you drive the price down and the money disappears. Furthermore, when the price of bonds declines, interest rates will rise and the national debt will increase more rapidly. If the economy cannot withstand higher interest rates, a recession will deepen. You have to get the timing right, and the world is in such a delicate state that it is impossible to get the timing entirely right for everybody. Because interest rates are now essentially zero, they cannot go lower, so investment advisors are increasingly advising clients to sell some bonds while they still can. If that gets out of hand, it could start a panic.

|

| United States Federal Reserve |

However, the United States Federal Reserve is not an investor, it controls the currency and can print unlimited amounts of it. There is nothing which can force it to sell its bond holdings, ever. Without going into the details of the Bretton Woods Treaty, the tie to gold was eliminated nearly fifty years ago. Meanwhile, its bonds are paying interest, which at the moment it is returning to the U.S. Treasury to reduce the national debt. It can reduce this outflow more or less at will, and it can increase it by raising interest rates (ie by selling bonds, as described). With a few extra steps, this enormous pot of debt could become the basis for an international currency reserve. At the least, it could bring a halt to an international currency war. If it chooses, it can decide to wait as long as fifteen or twenty years for economic demand to recover from a century of overleveraging, and then pay it back by letting the bonds reach maturity. But there is at least one big flaw in this dream.

At some point, the bond market may decide to take the bull by the horns and raise rates before the Federal Reserve wishes to. Political appointees come and go, and the bond market could easily decide that a misjudgment has been made by somebody. It could easily happen that public apprehension could grow that something doesn't smell right. In that climate, a few heavy sales could trigger a panic. And then everyone will try to get out the door at the same time.

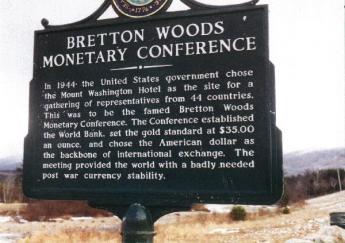

Bretton Woods

|

| The Bretton Woods conference in 1944 |

Stripped of its mystery and irrelevant details, the Bretton Woods conference agreed that all nations would make their currency convertible into U.S. dollars, and the U.S. would make its currency convertible into gold. Since World War II had left the United States with the only major working economy, it sold goods to the rest of the world and the rest of the world sent us their money to be converted into dollars; we had a "favorable balance of trade." Somewhere in the 1960s the rest of the world got on its feet, and we began to have an unfavorable balance of trade. After a while, foreigners started converting their dollars (the "reserve" currency) into gold. By 1971, the depletion of gold from Fort Knox became alarming, and the United States stopped converting its currency into gold. From that point onward, all currencies became effectively computer notations, whose value as a medium of exchange was what their government said it was.

Paradoxically, it is hard to see how this system would work without a government in charge of it, although private substitutes would probably soon appear if governments relaxed their monopoly on currency. Since a great many people dislike their governments for one reason or another, they chafe at a system which forces them to keep their governments in order to prevent commercial chaos. For those who do not adequately understand this, governments all stand ready to maintain themselves with force, and many other people dislike that feature even more. Since it took place at the same time, the Vietnam protest movement may have had some relation to this major change in the nation, misunderstood perhaps, but viscerally perceived. In view of President Nixon's central role in all of this, one is even tempted to speculate that his electoral promise of a secret means to end the Vietnam conflict, coupled with the subsequent peaceful surge of China and the financial recycling of Chinese money through Treasury bond purchases, may all have been subjects discussed during his historic trip to China.

However that may be, it is a fact that the Vietnam War ended, the Chinese economy flourished with American help, and the deposit of Chinese money in our economy helped fuel a massive economic bubble, and the weakest links in the chain -- mortgage-backed securities -- were the place the bubble burst. Not much of this could have occurred with a gold standard, and in many circles, this was regarded as proof that gold was a barbarous relic. In retrospect, few would deny we had been leveraging our economy to dangerous heights, for nearly fifty years. In 1996, Alan Greenspan denounced our "irrational exuberance", and yet the bubble did not burst for another twelve years. If we succeed in deleveraging our economy until it reaches 1996 levels, it will be regarded as a remarkable success. But the Chairman of the Federal Reserve at that time described it as a dangerous level. And looking back over the centuries, an indescribable number of kings were dethroned or beheaded because they evaded the rather irrational restraints of a scarce, hence precious, barbarous relic. Balanced against that, a billion Asiatics have been raised out of poverty, and the economy of the world overall would seem opulent to our grandfathers. Somehow, we must find the wit and the self-restraint to solve this problem.

REFERENCES

| The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order:z Benn Steil: ISBN-13: 978-0691149097 | Amazon |

Minimum Wage Fangdoodle

|

| Governor Chris Christie |

The November 2013 elections have been widely accepted to be a spectacular win for New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, suddenly making him a presidential front-runner for 2016. The only other significant election was a close win in the Virginia gubernatorial race for a fund-raising crony of Bill Clinton over the Attorney General who started the Supreme Court Case over Obamacare. In the view of the news media, there were only two elections in this off-year -- a landslide in New Jersey, and a dead heat in Virginia, for Governor.

Well, as a matter of fact, there was also an election in New Jersey for all of the members of the legislature, which means that I was running against the Democratic majority leader in the 6th Legislative District. I got 19,000 votes, but I needed more to win. At least in my family, it was a big event, particularly since no one else in New Jersey contributed a dime to my campaign, and while Governor Christie may have whispered a few encouraging words to me, there was no evidence of his assistance. But you can forget about that, too, because this election was really about the minimum wage.

The first inkling I got that something was up was receiving a sample ballot, three days before the election, where there was a referendum question about the minimum wage that no one had told me about, although it could scarcely have been a secret to get it on the ballot. And secondly, on election day there was scarcely any evidence of campaigning for Democrat candidates except for a few yard signs, but literally, dozens of campaign workers poured into the subway stations, handing out great volumes of campaign literature about the minimum wage. Even that went past me unnoticed, because who in the world would vote for a proposal which would increase unemployment during a severe recession? When I expressed the same sentiment to my Democratic friends, I was surprised to discover they all knew about it in advance. In retrospect, that was a fairly good indication that the Internet had selectively urged support of this proposition to the party faithful, but had not said one word in campaigning for it. It won endorsement by a heavy margin, as things soon turned out. What's worse, what had been endorsed by referendum had been to amend the constitution to this effect, automatically indexing it to the cost of living. It's going to be pretty hard to reverse that since all constitutions have been written to make it very hard to amend them.

p> In the week after the election, I notice that several other states have been considering raising the minimum wage. An article appeared on the editorial page of the New York Times arguing that research showed there was no evidence that raising the minimum wage caused unemployment, and a few days later, Paul Krugman had a learned column on the Times editorial page to the effect that smart people all knew there was no reason to expect unemployment from raising the minimum wage, and only the hopelessly ignorant rubes would imagine there was reason to think so. Having spent some time with editorial writers, it seemed pretty evident to me that there was a nationally coordinated effort to convert this into a truism, accepted so widely it would be futile to argue against it. When it is also possible to see the existence of a campaign to impose a maximum wage (and not merely in Switzerland, where it was defeated on a ballot), the trajectory of a rising minimum wage meeting a falling maximum wage easily led to conjectures that what was really afoot was a campaign to take wages out of the marketplace. Or was that really the goal?

|

| Ben Bernanke |

For months, the Federal Reserve Chairman has been emphasizing that the Fed must obey two mandates: to maintain price stability and to minimize unemployment. Meanwhile, the dirty little secret among economists has been that unemployment is the main obstacle to inflation in the face of a massive enlargement of the money supply. Unemployment is currently at 7.1% and falling, while the Fed has lifted the veil of "transparency" to reveal it made a promise in double-speak to start selling some of the bonds it issued to combat the recession when unemployment reaches 6.5%. As time has gone on, Mr. Bernanke has seemed to back away from that promise. He is not so sure that unemployment is a good measure of unemployment, other measures may be a better measure of what we are driving at. He never meant to start selling bonds when unemployment reached 6.5%, he only meant that he might reduce the number he planned to buy. He never meant to make a promise, he only was being transparent about the current thinking of the Board. And anyway, Janet Yellen will take over his job in a month, so you can't very well bind your successor to do anything at all. What's this tap-dancing all about?

Well, it simply won't do, to suggest that the Federal Reserve isn't as independent of politics as it pretends to be. But everyone noticed that the stock market had a bad fainting spell when he suggested a few months ago that the Board had been discussing the matter; just imagine what it would do if he actually made a promise to act, let alone actually taking an action. By itself, such an announcement would probably send interest rates on a rise toward normal levels. The stock market mostly anticipates the future, so it would jump ahead of whatever action was taken. Since the United States is now the largest debtor on earth, a rise of interest rates would immediately add huge amounts to the current deficit and the projected national debt. The stock market would almost surely drop, possibly severely, in response to such commotion in the debt markets. And the national economy would certainly feel the deflationary effect of such activity in the financial markets, sending markets even lower. Fear of such a reaction would surely persist longer than the real need for monetary easing, making the resultant inflation even worse than it had to be.

Is it possible the Obama Administration prefers a little extra unemployment, to risking a stock market crash before a coming election?

|

| Minimum Wage Uproar |

In an era of desperate experimentation with the simultaneous solutions of several problems at once, perhaps the best conservative response to this paper is to seek ways to relax its inflexibility. The political process, particularly the amendment of state constitutions, is a lengthy and cumbersome impediment to agile management of the economy. It is fairly unlikely that a secret springing of a referendum trap can be repeated. The greater risk is that we will know what should be done, but become unable to do it quickly.

Meanwhile, the politicians are designing things and politicians like things simple. The Republican solution is to pass a minimum wage, but keep its benefit slightly below the entry-level wage; they get credit for passing it, but it has almost no applicability. The Democrat approach is to make a big noise about passing a meaningless bill, promising they will make it up with off the balance sheet entitlements, like health care and college tuition. Either way, usually nothing much happens after the election is over.

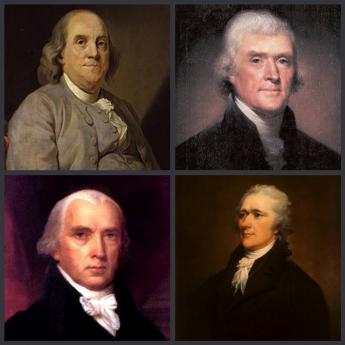

Enforcing the Constitution: Civil Monetary Penalties (CMP)

|

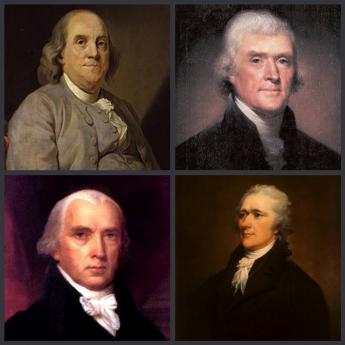

| Founding Fathers |

The 1787 Constitution created three branches of government along with their defined powers but described no remedy for a branch overstepping its boundaries. Gradually, a system evolved for declaring some laws unconstitutional, one by one, clarifying individual issues along the way. By contrast, the founding fathers viewed the President as an agent of Congress, expecting Congress to devise controls if needed. George Washington had an intense distaste for monarchs, and eight years as Commander in Chief had exposed no taste for conflict with the Continental Congress. Unfortunately, this has proven to be unusual for Presidents, especially as popular sovereignty appears to expand the Presidential mandate. Moreover, Washington himself developed more friction with Congress during his two terms as President.

In retrospect, the main factor behind Presidential restlessness is the experience of misinterpreting the meaning of a broader electoral mandate, which can more properly be traced to hasty repair of the defects of the 1800 election process. Experience has shown that while ignoring rules invites anarchy, the impeachment of a President usually seems too drastic a remedy for unwelcome innovation while impeaching the whole Legislative Branch for failure to supervise in a general way, is incomprehensible. The President needs some sort of supervision. While the original intent was to have Congress do the supervising, the Supreme Court is now probably better suited for judging the issue of unconstitutional behavior, except for the awkwardness that the President appoints the Supreme Court. These are the simple ingredients of a solution, preferably unwritten and revolving around conferring special "standing" in special circumstances.

|

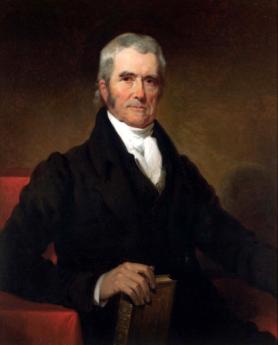

| Chief Justice, John Marshall |

At present, grievances tend to accumulate until someone acquires "standing" by being injured. At present it is generally true a grievance scarcely matters if no one is injured, but the exception is the lack of redress for injury to the Constitution, whereby everyone may be injured. Furthermore, actual experience with creeping boundary encroachment has mostly proved to be nuanced, rather than confrontational, gradual rather than abrupt. The descriptive example is that of a frog in a gradually heated pan of water, whereby the frog is cooked faster than he realizes he is in danger. Otherwise, the courts have evolved an unspecified balance which has proved remarkably serviceable.

It took thirty years for John MarshalI to formulate the general approach needed. In Marbury v. Madison , his first action after becoming Chief Justice, John Marshall suggested a writ of Mandamus (i.e. "We command...") from the Court might well be the first step in what he coyly described as only a hypothetical situation. Only lawyers were expected to recognize fully that If the President ignored the writ, then the grounds for impeachment might escalate, with the President forced into the role of flouting a decision of the Court. Regardless of how it stood on the original issue, the public would likely support a Court in performing its duty to make difficult decisions.

One way or another, the national issue would become one of whether the nation wished to continue with its Constitution; Marshall had only outlined the steps the process would probably take. At several points along the way, the Chief Justice would have a chance to back off. But Marshall's lifelong hatred of his cousin Thomas Jefferson was so well known there was little doubt he was serious. Knowing of his cousin's hatred for him, President Jefferson let the matter drop; subsequent Presidents followed his example. Generations of lawyers have studied this case and pondered its implications. The solution to the problem of extending it from unconstitutional laws to unconstitutional behavior, probably already exists in many minds.

"Sir"

In 1938 when I was 14 years old, I entered a new virtual country with its own virtual language. That is, I went to an all-male boarding school during the deepest part of the worst depression the country ever had.

|

| Boarding School |

identified While it should be noted I had a scholarship, there is little doubt I was anxious to learn and emulate the customs of the world I had entered. My life-long characteristic of rebellion was born here, but at first, it evoked a futile attempt to imitate. Not to challenge, but to adopt what I could afford to adopt. The afford part was a real one because the advance instructions for new boys announced a jacket and tie were required at all meals and classes, and a dark blue suit with a white shirt for Sunday chapel. That's exactly what I arrived with, and let me tell you my green suit and brown tie were pretty well worn out by the first Christmas when I came home on the train for ten days vacation, the first opportunity to demand new clothes. First-year students were identified by requiring a black cap outdoors, and never, ever, walking on the grass. The penalty for not obeying the "rhine" rules was to carry a brick around, and if discovered without a brick, to carry two bricks. But that's not what I am centered on, right now. The thing which really bothered me was unwritten, equally peer-pressured by my fellow students, the custom of addressing all my teachers as Sir. The other rules only applied until the first Christmas vacation, but the unwritten Sir rule proved to be life-long.

|

| Sir |

And it was complicated. It was Sir, as an introduction to a question, not SIR!, as a sign of disagreement. You were to use this as an introduction to a request for teaching, not as any sort of rebuke or resistance. Present-day students will be interested to know that every one of my teachers was a man; my recollection is, except for the Headmaster's secretary, the Nurse was the only other female employee. The average class size was seven. Seven boys and a master. Each session of classes was preceded by an hour of homework, the assignment for which was posted outside a classroom containing a large oval maple table. Needless to say, the masters all wore a jacket and tie, most of the finest style and workmanship. They always knew your name, and always called on every student for answers, every day. Masters relaxed a little bit during the two daily hours of required exercise, when they took off their ties and became the coaches, but were just as formal the following day in class. I had been at the head of the class of what Time Magazine called the finest public high school in America, but I nearly flunked out of the first semester in this boarding school. It was much tougher at this private school than I felt any school had a right to be, but they really meant it. Over and over, the Headmaster in the pulpit intoned, "Of those to whom much is given, much is expected."

I had some new-boy fumbles. Arriving a day early, I found myself with only a giant and a dwarf for a company at the dining table. I assumed the giant was a teacher, but he was a star on the varsity football team. And I assumed the dwarf was a student, but he was assistant housemaster. One was to become a buddy, the other a disciplinarian, but I had them reversed, calling the student "Sir", but the master by his first name. Bad mistake, which I have been reminded of, at numerous reunions since then.

|

| Yale |

When I later got to Yale, I began to see the rules behind the "Sir," rule. In the first place, all of the boarding school graduates used it, and none of the public school graduates, although many of the public school alumni began, falteringly, to imitate it. Without realizing it, a three-year habit had turned out to be a way of announcing a boarding school education. The effect on the professors was interesting; they rather liked it, so it was reinforced. It had another significance, that the graduates who said "Sir" acquired upper-class practices, the red-brick fellows seldom did. The only time I can remember it's being scorned was eight years later, by a Viennese medical professor with a thick accent, and he was obviously puzzled by the significance. Hereditary aristocracy, perhaps. Indeed, I remember clearly the first time I was addressed as Sir. I was an unpaid hospital intern, but the medical students of one of the hospital's two medical schools flattered me with the term. In retrospect, I can see it was a way of announcing that graduates of their medical school knew what it meant, while the other medical school was just red-brick. Although the latter had mostly graduated from red-brick colleges, their medical school aspired to be Ivy League.

If you traveled in Ivy League circles, the Sir convention was pretty universal until 1965, when going to school tieless reached almost all college faculties, thus extending permission to students to imitate them. Perhaps this had to do with co-education, since the sir tradition was never very strong in women's colleges, and denounced by the girls when the men's colleges went co-ed. Perhaps it had to do with the SAT test replacing school background as the major selection factor for admission. Perhaps it was the influx of central European students, children of European graduates for whom an anti-aristocratic posture was traditional, and until they came to America, largely futile. Perhaps it was economic. The American balance of trade had been positive for many decades before 1965; afterward, the balance of trade has been steadily negative.

In Shakespeare's day, "Sirrah" was a slur about persons of inferior status. In Boswell's eighteenth Century day, his Life of Johnson immortalized his characteristic put-down with a one-liner. It survives today as a virtually text-book description of how to dominate an argument at a boardroom dispute. "Why, Sir," was and remains a signal that you, you ninny, are about to be defeated with a quip. It's a curious revival of a new way of immortalizing small-group domination, and a very effective one at that, which even the soft-spoken Quakers use effectively. Whatever, whatever.

The 90-plus years of tradition of addressing your professor as "Sir," is gone, probably for good, except among those for whom it is a deeply ingrained habit. Along with the tradition of female high school teachers, followed I suppose by male college professors.

13 Blogs

Warnings of Impending Trouble for the PRR

In retrospect, railroads were in danger from overcapacity as early as 1880. Their sluggish recovery from the 1929 financial crash was another warning of underlying weakness. Wartime profits and postwar boom concealed huge deferred maintenance costs built up during the great depression and World War II.

In retrospect, railroads were in danger from overcapacity as early as 1880. Their sluggish recovery from the 1929 financial crash was another warning of underlying weakness. Wartime profits and postwar boom concealed huge deferred maintenance costs built up during the great depression and World War II.

Brave New World

A surprising secret of the younger generation.

A surprising secret of the younger generation.

Falstaff Without Prince Hal

The parents of W.C. Fields didn't treat him very well, but he always acted as though Philadelphia didn't treat him well. Philadelphia's main crime was probably that it disliked the Volstead Prohibition of Alcohol Act somewhat less than Fields disliked it.

The parents of W.C. Fields didn't treat him very well, but he always acted as though Philadelphia didn't treat him well. Philadelphia's main crime was probably that it disliked the Volstead Prohibition of Alcohol Act somewhat less than Fields disliked it.

Show Biz Image: Hepburn, Rogers, Kelly

Hollywood presented a cartoon of the upper class during the Depression. World War II was soon to sober us up.

Hollywood presented a cartoon of the upper class during the Depression. World War II was soon to sober us up.

Rise and Fall of Life Insurance

Like many things, insurance started here. It's now mostly all gone.

Like many things, insurance started here. It's now mostly all gone.

Northwest Rittenhouse Square

The fashionable district doesn't need so many mansions, and the Universities can't yet use the space, either. It's uncertain whether the area will become office buildings, or revert to townhouses.

The fashionable district doesn't need so many mansions, and the Universities can't yet use the space, either. It's uncertain whether the area will become office buildings, or revert to townhouses.

Medical Club of Philadelphia, Appendix B, Membership

..... Recruitment of membership was an instantaneous success during the Gilded Age and rose to a peak in the early years of the Great Depression of the 1930s. After that, interest in membership steadily declined. Excursions on private trains and dinners with the U.S. President were no longer within their means.

Recruitment of membership was an instantaneous success during the Gilded Age and rose to a peak in the early years of the Great Depression of the 1930s. After that, interest in membership steadily declined. Excursions on private trains and dinners with the U.S. President were no longer within their means.

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

Bernanke's QE3: A New Titanic, or A New Bretton Woods?

Ben Bernanke is crossing Niagara Falls on a tightrope.

Ben Bernanke is crossing Niagara Falls on a tightrope.

Bretton Woods

The Bretton Woods conference in 1944 was very simple. The U.S. dollar alone was convertible into gold, but all other currencies were convertible into U.S. dollars. To prevent Fort Knox from being completely depleted of gold, the convertibility of dollars into gold was also soon discontinued. Effectively, all money everywhere was thus just a computer notation, controlled by the U.S.government. Temporarily, the dollar became a reserve currency, supplementing gold. Effectively, we were testing whether we needed a metallic standard at all.

The Bretton Woods conference in 1944 was very simple. The U.S. dollar alone was convertible into gold, but all other currencies were convertible into U.S. dollars. To prevent Fort Knox from being completely depleted of gold, the convertibility of dollars into gold was also soon discontinued. Effectively, all money everywhere was thus just a computer notation, controlled by the U.S.government. Temporarily, the dollar became a reserve currency, supplementing gold. Effectively, we were testing whether we needed a metallic standard at all.

Minimum Wage Fangdoodle

While no one was looking, mandating a minimum wage turned into a contrivance to maintain low-interest rates.

While no one was looking, mandating a minimum wage turned into a contrivance to maintain low-interest rates.

Enforcing the Constitution: Civil Monetary Penalties (CMP)

The Constitution does not define penalties if one branch of government oversteps its grant of authority. But starting with writs of mandamus , the U.S. Supreme Court has left the other two branches with little alternative but compliance.

The Constitution does not define penalties if one branch of government oversteps its grant of authority. But starting with writs of mandamus , the U.S. Supreme Court has left the other two branches with little alternative but compliance.