4 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Worldwide Common Currency and Corporate Headquarters

The Death of Money

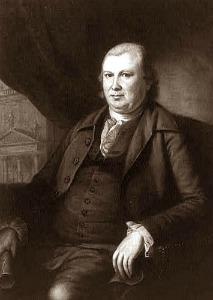

American Finance After Robert Morris

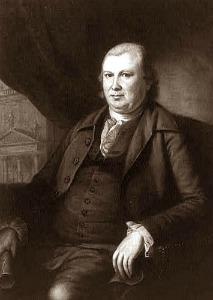

Robert Morris can be fairly said to have made the American Revolution possible.

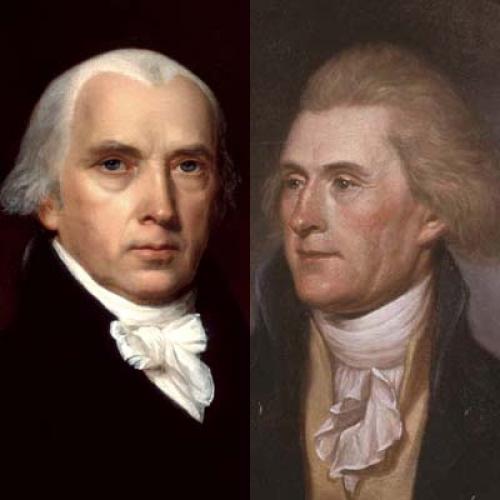

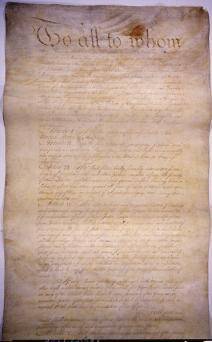

Unwritten Features of the Constitution

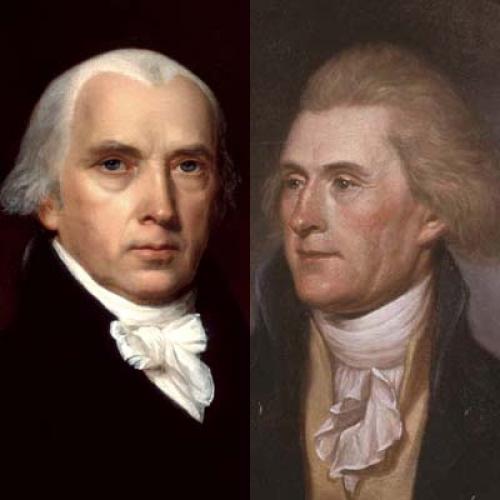

Considerable anger is sometimes directed toward Judges who find unintended provisions in the Constitution. On the other hand, James Madison and some other Founding Fathers were careful to design the Constitution to create outcomes that are far from explicit.

|

In their early writings, James Madison and the Federalists who participated in drafting the Constitution repeatedly emphasized their allegiance to republican ideals, republicanism, and a republican form of government. This sounds a little odd today, since obviously they were not alluding to the present Republican and Democratic parties, which had not been created. It seems natural to us to regard a republican form of government as a gradual extension of a democratic one, when the size of the electorate grows so large it cannot be readily managed by voice votes in a town meeting, when therefore it becomes necessary to select proxies, or representatives. That description greatly underestimates the subtlety of the Founding Fathers.

|

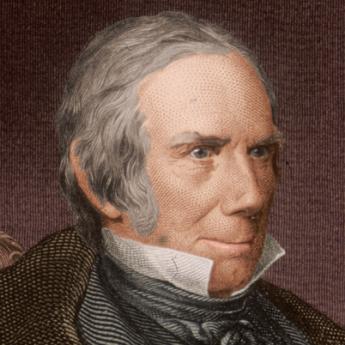

| Gouverneur Morris |

Two centrally important members of the Convention, James Madison and Gouverneur Morris, felt especially strongly about a feature that does not occur to many others. When the voters in a particular district pick a representative, they are generally trying to choose one who will not only reflect issues of local importance, but one who will be able to persuade representatives of other districts to vote favorably. In this way, representatives tend to be selected who are taller, handsomer, more intelligent, richer, and more famous than the average person in the district being represented. Not by much, perhaps, and sometimes not at all. But as a general thing, the election of representatives tends to create a House of Representatives who are superior in certain ways to the average person being represented. When candidates and political parties engage in public combat, an impression is given that "politicians" are low characters, but that is in fact not usually true. Many factors will discourage the best candidates from participating in disagreeable contests, and many stratagems are employed in an attempt to elect the worse of two candidates. But it is seldom the case that a successful candidate is less attractive or talented than the average person in his district. Republican governments almost always are composed of more distinguished persons than average, exposed to greater temptations perhaps and subject to more detailed scrutiny.

Madison was so taken with this idea that he proposed the Senate should be made up of people drawn from the House of Representatives in a second round of voting, thereby further purifying the result. For various reasons this approach was not adopted by the Convention, but it does have a logic to it, and it clearly illustrates that Madison was looking for results not always explicitly stated. Gouverneur Morris, on the other hand, was openly enthusiastic for this outcome, because he perceived that the government would be largely concerned with the rules of commerce and therefore the selection process would likely lead to a Congress that was richer and more able in those qualities of importance to commerce. On the one hand, America would gain national advantage in the Industrial Revolution then under way, and it would anyway be highly desirable to select richer people. In his later years, Morris was given to blunt and open preference for the smart set, and is often described as a covert aristocrat. At the time of the Convention however it seems likely he was making a perfectly valid point which had escaped many of his colleagues.

|

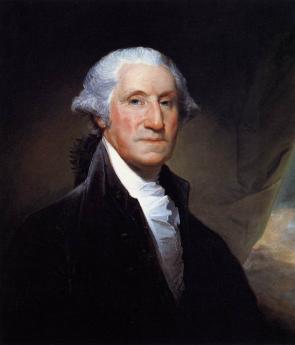

| James Madison |

Both Madison and Morris were seriously concerned about a flaw in the republican form of government. They thought it obvious there would always be more poor people than rich ones. Without some effort to rebalance things, the poor would inevitably destroy the common good by using their numerical strength to redistribute wealth from rich to poor. In doing so, everyone would be worse off, even the poor. The poor were more likely to be uneducated and thus more likely to put their own enrichment ahead of almost any other issue, using their own grievances as a justification. There was almost universal agreement among other members of the Convention, because it was well recognized that the main need for a new constitution had grown out of the egregious conduct of state legislatures under the Articles of Confederation, particularly in watering the currency with paper money, and profligate use of debt forgiveness. It would be impossible to have a prosperous country if it suffered from instability, destruction of merit incentives and respect for the property of others. If debts were capriciously forgiven, no one would lend. With paper currency printed indiscriminately, savings would be impossible.

|

| Political parties |

Accordingly, the Convention set about balancing these innate tendencies as well as it could. There was general agreement that election districts with larger population size tended to produce better candidates. Not only employing the reasoning that in a larger district it would be harder to elect an unknown, insignificant person, they felt they could also see examples justifying faith that a larger number of competing internal interests would hold each other in check within the person of their elected representative. An indirect way of accomplishing this was to limit the total number of districts while also providing they be of equal population. Political parties were soon to come forward as a way of raising campaign funds, but nevertheless a person of greater means would have an advantage in a larger district, and persons of greater means could be expected to have greater talents, or would in any event be more likely to resist the pressures for redistributing the wealth of the rich. Members of the Senate were selected by the state governments (at least, as long as state assent was necessary for ratification of the Constitution), but the 17th Amendment changed that to popular election, with a clear resulting decrease of state influence and power. On the other hand, a heavy majority of Senators in the 21st Century continue to be independently wealthy, thereby still accomplishing two original objectives of the founding fathers at one stroke.

|

| 5th Amendment |

The original working concept of the Federalists was that the skills and prestige of the rich and powerful would promote the owners of property into elective office, and their power would be joined to that of judges, presidents, cabinet officers, and military officers to form an effective counterbalance to the majority voting power of the poor or others who lacked property to protect. The Federalists differed with the anti-Federalists on the source of danger to be guarded against; one group feared impetuous and ignorant greed inciting the multitude, while the other group mainly feared corruption and power-hunger among the powerful few. But both political parties acknowledged that each potential danger was realistic to some degree, and hence there was reason to hope both sides could agree to a balance of power as a sensible check on each other. True, the Fifth Amendment's "takings" clause did specifically provide for just compensation for private property seized by government under Eminent Domain, and the Eleventh Amendment protected state governments against private lawsuits in Federal court, but these seem rather feeble additions to the protections against potential tyrannies of the unpropertied majority, as soon to be seen in the revolutionaries of France. Thus an initial assessment would have to be that protection of the minority with property against legislative assault by the unpropertied majority, was only strong in the short run. But it was likely to succumb in the long run to majoritarian tyranny, as the less educated gradually learned how to use their voting power. To strengthen the balance, therefore, resort was made to limiting the voting franchise to owners of property, and specifically to freehold property, without debt. There was shrewdness to this idea, since it hints at a perception that future class divisions might not lie between rich and poor, but between creditors and debtors. The voting exclusion of females, children and slaves was surely irrelevant to the main issue, based on the 18th Century assumption that any votes from those excluded would anyway be passive, dominated by the male head of household. In any event, the limitation of voting power to freehold property owners was apparently a step too far, and did not last long.

It is not certain how consciously another important feature was considered. State legislatures prior to the Constitution were held in such disdain, that stripping them of the power to corrupt truly important issues was almost a universal goal. Awkwardly, a peaceful transfer of state power over the military and the currency could not be accomplished without securing the agreement of the states who had to ratify the Constitution. This was accomplished by specifying the strictly limited powers of the new Federal government, and ceding control of everything not specifically mentioned, back to the states. One by one, the functions which were vitally important were debated and defended in detail; the list was short. Everything else remained under state control. To go about things in this way had one significant advantage over complete federal control, and Madison specifically anticipated it. If a state government abused its power, the victims of that abuse could escape by relocating to a neighboring state. The potential abuse easiest to understand was a burdensome tax rate. But all of the commercial rules of the new entities called corporations were even more to the point, since rich people could move whole factories and businesses if they perceived enough grievance at home. Powerful people had ways of getting the attention of state governments, their U.S. Congressmen and Senators, and the constituents who voted for them. In New Jersey at present, 4% of the taxpayers pay 76% of state taxes; it is easy to demonstrate that the 4% are moving to other states about as fast as they can. Whether by industry or individually, the residents of a state know very well what their alternatives are in other states, and corporations can negotiate them directly. Whether to bluffing or actually moving, state politicians respond to the threat and which has considerable indirect effect at a national level. The system of checks and balances extends far beyond the words of the Constitution, and well beyond the rules of the Federal government. Its unwritten power extends beyond the control of a handful of Supreme Court justices, spatting over original intent. Its potential weakness, of course, lies in the Court's relative inability to protect what is not stated to be any of its business.

|

| 1787 founders |

One final point about the unspoken cleverness of our Constitution. Some of its most important powers were either unrecognized or intentionally unmentioned by its originators, to whom we look for original intent. After two centuries, we can see as they could not, that it was not merely the first time thirteen sovereign states gave up their power voluntarily and more or less cooperatively. In two hundred or more years, it begins to look as though nobody else can even imitate it successfully. One therefore hesitates to suggest changes of any sort, for fear some unrecognized balance will become unbalanced. Madison believed that increasing size leads to better government and better candidates for office; few would dispute that our Federal government generally does a better and more professional job than the fifty states which make it up. But stop to consider the United Nations. Invested with as much enthusiasm and much more idealism than our 1787 founders, the U.N. flounders and fumbles, and after fifty years must still be assessed to be a failure. Madison would seemingly have predicted that a bigger organization would be even stronger, even electing an assembly of giants. It hasn't worked out that way, and it is impossible to define what it lacks that the American Constitution has in abundance. By itself, this is the strongest possible argument for what is called original intent, but is really just a fearful plea to -- leave it alone.

After the Convention:Hamilton and Madison

|

| Signers |

The Federalist Papers were written by three founding fathers after the Constitution had been completed and adopted by the Convention. Detecting hesitation in New York, the aim was for publication in New York newspapers to persuade that wavering State to ratify the proposal. It is natural that The Federalist was composed of arguments most persuasive to New York, putting less stress on matters of concern to other national regions. This narrow focus may explain the close cooperation of Hamilton and Madison, who must surely have suppressed some latent concerns in order to present a unified position. In view of how much emphasis the courts have placed on the original intent of almost every word in the Constitution, it seems a pity that no one has attempted to reconcile the words of the principal explanatory documents with the hostile disagreements of their two main authors, almost as soon as the Constitution came into action. Perhaps the psychological hangups would be more convincingly dissected by playwrights and poets, than historians.

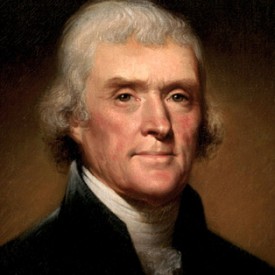

John Jay wrote five of the essays, mostly concerned with foreign relations; his presence here highlights the historical likelihood that Jay might have been the one who first voiced the idea of replacing the Articles of Confederation. At least, he seems to have been first to carry the idea of a general convention for that purpose to George Washington (in a March 1786 letter). The remaining essays of The Federalist were written under the pen name of Publius by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, both of whom had a strong enough hand in crafting the Constitution, but who quickly became absolutely dominant figures in the two central political factions after the Constitution was actually in operation. And their eagerness to be central is itself telling. They were passing from a stage of pleasing George Washington with his favorite project, into furthering a platform for launching their own emerging agendas. It is true that Madison's Federalist essays were mainly concerned with relations between the several states, while Hamilton concentrated on the powers of the various branches of government. As matters evolved, Hamilton soon displayed a sharper focus on building a powerful nation; Madison scarcely looked beyond the strategies of internal political power except to see clearly that Hamilton was going to get in the way. These two areas are not necessarily incompatible. But it is nevertheless striking that two such relentlessly driven men could work together to achieve the same set of rules for the game they were about to play so unflinchingly. Thomas Jefferson had been in France during the Constitutional Convention. It was he who was most dissatisfied with the resulting concentration of power in the Executive Branch, but Madison eagerly became the most active agent for forming the anti-Federalist party, with all its hints that Washington was too senile to know the difference between a President and a King. Washington abruptly cut him off and never spoke to Madison after the drift of his opinions became undeniable. Today, it is common to slur politicians for pandering to lobbyists and special interests, but that presents only weak competition with the personal forces shaping leadership opinion, chief among them being loyalty to, and perceived disloyalty from, close political associates.

As a curious thing, both Hamilton and Madison were short and elfin, and both relied for influence heavily on their ability to influence the mind of

|

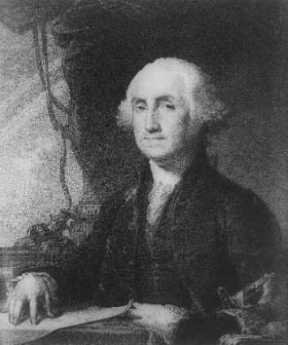

| George Washington |

George Washington, who projected the power and manner of a large formidable athlete. Washington had no strong inclination to run things and, once elected, no particular agenda except to preside in a way that would meet general approval. He had mainly wanted a new form of government so the country could defend itself, and pay its soldiers. Madison was a scholar of political history and a master manipulator of legislative bodies, while Hamilton's role was to supply practically unlimited administrative energy. Washington was good at positioning himself as the decider of everything important; somehow, everybody needed his approval. On the other hand, both Madison and Hamilton were immensely ambitious and needed Washington's approval. This system of puppy dogs bringing the Master a bone worked for a long while, and then it stopped working. Washington was very displeased.

The difference between these two short men immediately appeared in the way they chose a role to play. Madison the Virginian chose to dominate the legislative process as the leader of the largest state delegation within the

|

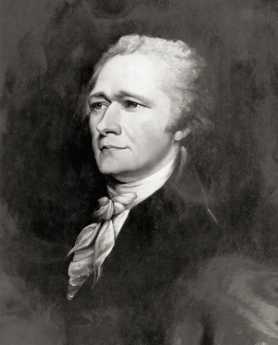

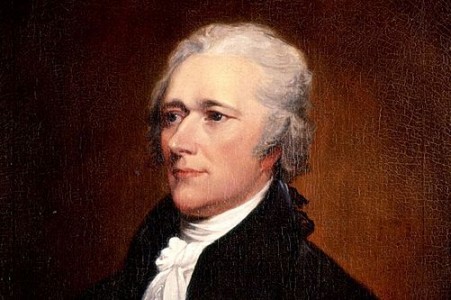

| Alexander Hamilton |

House of Representatives, in those days the dominant legislative chamber. Hamilton sought to be Secretary of the Treasury, in those days the largest and most powerful department of the executive branch. It's now a familiar pattern: one wanted to form policy through dominating the board of directors, while the manager wanted to run things his way, even if that led in a different direction. Both of them knew they were setting the pattern for the future, and each of them pushed his ideas as far as they would go. Essentially, this could go on until Washington roused himself.

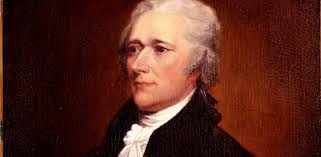

After a short time in office, Hamilton wrote four historic papers about two general goals: a modern financial system, and a modern economy. For the first goal, he wanted a dominant national currency with mint to produce it and a bank to control it. Second, he also wanted the country to switch from an agricultural base to a manufacturing one. You could even say he really wanted only one thing, a national switch to manufacturing, with the necessary financial apparatus to support it. Essentially, Hamilton was the first influential American to recognize the power of the Industrial Revolution which began in England at much the same time as the American Revolution. Hamilton was swept up in dreams of its potential for America, and while puzzled -- as we continue to be today -- about some of its sources, became convinced that the secrets lay in the economic theories of

|

| David Hume |

David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, and of Necker in France. Impetuous Hamilton saw that Time was the essence of opportunity; we quickly needed to gather the war debts of the various states into the national treasury, we quickly needed a bank to hold them, and a mint to make more money quickly as liquidity was needed. It seemed childishly obvious to an impatient Hamilton that manufacturing had a larger profit margin than agricultural products did; it was obvious, absolutely obvious, that this approach would inspire huge wealth for the new nation.

|

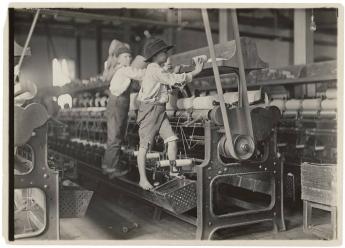

| Industrial Revolution |

Well, to someone like Madison who was incredulous that any gentleman would think manufacturing was a respectable way of life, what was truly obvious was that Hamilton must be grabbing control of the nation's money to put it all under his own control. He must want to be king; we had just got rid of kings. Furthermore, Hamilton was all over the place with schemes and deals; you can't trust such a person. In fact, it takes a schemer to know another schemer at sight, even when the nature of the scheme was unclear. Madison and Jefferson couldn't understand how anyone could look at the vast expanses of the open continent stretching to the Pacific without recognizing in this must lie the nation's true destiny. Why would you fiddle with pots and pans when with the same effort and daring you could rule a plantation and watch it bloom? If anyone had used modern business jargon like "Win, win strategy", the Virginian might well have snorted back, "When you say that to me, friend, smile."

Alexander Hamilton, Celebrity

He had the kind of taudry private life and flashy public behavior that Philadelphia will only tolerate in aristocrats, sometimes.

|

It comes as a surprise that most of the serious, important things Alexander Hamilton did for his country were done in Philadelphia, while he lived at 79 South 3rd Street. That surprises because much of his more colorful behavior took place elsewhere. He was born on a fly-speck Caribbean island, the "bastard brat of a Scots peddler" in John Adams' exaggerated view, was orphaned and had to support himself after age 13. The orphan then fought his way to Kings College (now Columbia University) in New York in spite of hoping to go to Princeton, and has been celebrated ever since by Columbia University as a son of New York. He did found the Bank of New York, and he did marry the daughter of a New York patroon, and he was the head of the New York political delegation. As you can see in the statuary collection at the Constitution Center, he was a funny-looking little elf with a long pointed nose, frequently calling attention to himself with hyperkinetic behavior. Even as the legitimate father of eight children, Hamilton had some overly close associations with other men's wives, probably including his wife's sister. Nevertheless, he earned the affection of the stiff and solemn General Washington, probably through a gift of gab and skill getting things done, while outwardly acting as court jester in a difficult and dangerous guerilla war. There is a famous story of his shaking loose from the headquarters staff and fighting in the line at Yorktown, where he insolently stood on the parapet before the British enemy troops, performing the manual of arms. Instead of using him for target practice, the British troops applauded his audacity. Harboring no such illusions, Aaron Burr later killed him in a duel as everyone knows; it was not his first such challenge.

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler told other stories of celeb behavior to reinforce Hamilton's New York flavor. But in the clutch, General Washington learned he could always trust Hamilton, who wrote many of his letters for him and acted as his reliable spymaster. When the first President faced signing or not signing the fateful bill to create the National Bank, a perplexed Washington had to choose between: the violent opposition of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, or the bewildering complexity of Alexander Hamilton's reasoning in arcane economics. On the one hand, there was the simple principle that owing money was seemingly always evil; on the other was the undeniable truth that for every debit created, you create a balancing credit somewhere. Washington ultimately chose to go with Hamilton, whose reasonings he likely didn't understand very well. If you doubt the difficulty, try reading Hamilton's Report on the Bank, written to persuade the nation and its first President of the soundness of his ideas. And then consider the violence of even present-day arguments about such "supply side" economics.

|

| Nicholas Murray Butler |

All of these momentous events happened in Philadelphia at places now easily visited in a morning's stroll. But Hamilton's image as a Philadelphian, doing great things in and for Philadelphia, was forever tarnished at one single dinner he hosted. Jefferson and Madison, his political opponents but his guests, were persuaded to provide Virginia's votes for the federal takeover of state Revolutionary War debts, in return for offering New York's votes for moving the nation's capital to the banks of the Potomac. True, Pennsylvania allowed itself to be pacified with having the capital remain here for ten years while the southern swamps were being drained. But it was Hamilton who cooked up this deal and sold it to the other vote swappers. Philadelphia felt it was entitled to the capital without needing to ask, felt that Hamilton was deliberately under-counting Pennsylvania's war debts, and this city has never appreciated the insolent idea that its entitlements were forever in the hands of wine-swilling hustlers. As the economic consequences of this backroom deal became evident during the 19th Century, it was increasingly unlikely that Philadelphia would lionize the memory of the man responsible for it. Let New York claim him, if it likes that sort of thing. When Albert Gallatin, who was more or less a Pennsylvania home town boy, attacked Hamilton as a person, as a banker, and as a Federalist -- he had a fairly easy time persuading Philadelphians that this needle-nosed philanderer was an embarrassment best forgotten.

REFERENCES

| Alexander Hamilton Ron Chernow ISBN:978-0-14-303475-9 | Amazon |

Funding the National Debt

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

Although Alexander Hamilton's arresting slogan that "A national debt is a national treasure" has diverted attention to the underlying idea toward him, Robert Morris had introduced and argued for the same insight in the preamble to his 1785 "Statement of Accounts". The key sentence was, "The payment of debts may indeed be expensive, but it is infinitely more expensive to withhold payment." This fatherly-sounding advice was surely a distillation of a long life as a merchant, and the gist of it may have been passed down to him as an apprentice. Failure to pay your debts promptly and cheerfully results in the world assigning a higher interest rate to your future credit; it is not long before compounded interest begins to drag you down. It doesn't exactly say that, but that's what it means.

|

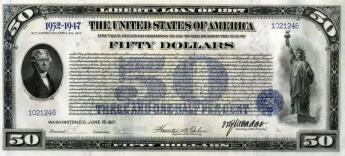

| Liberty Bond |

Another way of looking at this folk wisdom is that it leads to a simplified method of organizing the finances of an organization. Because higher rates of interest are demanded of long-term borrowing than short-term, it becomes efficient to segregate them. That is, to establish a cash account for every-day transactions, and a separate bond account for a long term, or capital, debt. As bills arrive, they need only be verified for accuracy and sent for payment from either a cash account or a capital account. The original responsibility for agreeing to such debts lies with top management, not the treasurer. The job of the treasurer's office is to pay legitimate bills as quickly and cheerfully as possible, ignoring any imprudence of earlier agreeing to them; rewards will come from lower interest charges and improved credit rating. An unexpected benefit of thus organizing institutions and governments is to make the accounting profession possible. Accountants perform the same function in every business, whether the business is selling battleships or parsnips. The accounting profession made itself computer-ready, two hundred years before the computer was invented.

|

| Robert Morris |

In the same document, the retiring national Financier was advising the wisdom of "funding" the war debts, which were largely owed to France, with whom relations were rapidly souring. Lump them all together into a fund, issue bonds and sell them as representations of the nation's capital at the time of issue. Disregard what the money was used for, by either the debtor or the creditor. In spite of appearances, money sequestered in a fund for later payment belongs to the creditor the moment it is promised, not the moment it is transferred. Morris and Hamilton discovered that the fund itself had the property of a bank, in creating money. As long as the creditor did not cash your bonds, he could use them as money, in effect doubling the amount of money you yourself can spend. It was this discovery which so exhilarated Alexander Hamilton, causing him to over-praise the methodology to an already suspicious Congress. Tending toward the teachings of Shakespeare's Polonius, Hamilton's excitable manner caused them to remember, neither a borrower nor a lender is. But Congress was eventually persuaded. The federal government lumped the states' debts together in an "assumption of debts" , consolidated all these various little debts into a single "funded debt", and made the deal work with changing the "residency" of the nation's capital from Philadelphia to the banks of the Potomac. It was called the Great Compromise of 1790.

Morris well understood that a funded system requires some final payor of last resort. Such a payor need set aside only a small portion of the debt for dire contingencies, but his name gets first attention on the list presented to prospective creditors. In 1778 Morris had offered his own personal wealth as that last resort, which the public at the time trusted far more than the Treasury of the United States. Over the next twenty years, he came to realize that the last resort of established nations, no matter what the paper said, was the aggregate underlying wealth of the whole nation. With a vast continent stretching to the West, and countless immigrants clamoring to join from the East, the wealth supporting the debt of the United States in 1790 seemed endless. After two hundred years we have finally begun to accumulate a national debt which equals our Gross Domestic Product, and have only begun to pull back as we observe what happens to other nations who got to that point sooner. Let's hope devising an automatic check and balance does not require a second Robert Morris. Men like him can be hard to find, so limit your debts -- or your nation's debts -- to sixty percent of your assets. Financial geniuses are invited to devise a better debt limit, if they can.

Morris at the Constitutional Convention

|

| Constitutional Convention 1787 |

TRUE, George Washington was the presiding officer of the Constitutional Convention. But Pennsylvania was the host delegation, so the role of presiding host should have fallen to Benjamin Franklin, the President of Pennsylvania. However, Franklin was getting elderly and turned the job over to Robert Morris, who among other things was rich enough to host some necessary parties. The rules of decorum at that time thus kept Washington and Morris out of the floor debates. The proceedings were, in any event, kept the secret, so occasional frowns or encouraging smiles are not recorded for history.

But Morris had been an active debater in the Assembly and other meetings, so he knew enough to line up a consensus in advance for the matters he thought were essential. Obviously, Morris was strongly in favor of giving the national government power to levy taxes for defense purposes, and Washington whose troops had suffered severely from the inability of the Continental Congress to pay them also regarded this taxing power as the central reason for changing the rules. By making it the central argument for holding the convention at all, Washington, Franklin, and Morris had made taxation power a foregone conclusion. And by giving them what they wanted from the outset, the rest of the convention was in a position to do almost anything else it wanted without open comment from the Titans. The sense of this trade-off was captured by Gouverneur Morris, the editor of the Constitution, in Article I, Section 8:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts, and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;This formulation had the effect of greatly empowering James Madison, the only participant who had studied the inside details intensively and cared about every comma. It also encourages the military to believe that federal taxation was mainly their entitlement, whereas those whose main goals are defined as "the general Welfare" tend to regard defense spending as an unnecessary deduction from their share.

|

| Pawn Broker Sign |

Most of the convention delegates had experience with state legislatures, and Franklin and Morris had spent decades struggling with the weaknesses of legislators. A wink or a quip in a tavern was as good as an hour's speech for reminding the delegates what they already knew about human nature. What was designed as a dual system of powers of taxation, with federal oversight of balanced state budgets combined with federal power to tax on its own in emergencies or unforeseen situations. Since the members of the first few congresses after 1789 were largely the same people as the members of the constitutional convention, many details of this balance were worked out over a few following years. State powers to tax and borrow were tightly constrained, only the federal government could tax and borrow without limit. Since government borrowing is merely the power to defer taxes until later, the borrower of last resort was the U.S. Congress, alone empowered to encumber the wealth of the whole nation in a federal pawn shop window called the funded National Debt. For almost two centuries, this pawn shop window seemed able to support any imaginable expense. Today, we monitor this as the ratio of national debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and we now have a clearer idea what level of that ratio flirts with hopeless inability to pay the federal government's debt. The experts say it's close to a 60% ratio, and unfortunately, almost every nation on earth now exceeds that limit. The system continues to lack an unchallenged definition of its limit, but the system is nevertheless still Morris's system, wrapped in a mountain of descriptive detail by Alexander Hamilton. If a nation borrows more than that and clearly will never repay it, that nation is to some degree a slave to its creditors, with war its only hope if creditors are unrelenting. Perhaps another way to refine the thought is to say that if the nation wishes to mortgage everything it owns down to the last shoe button, the creditors will only accept additional debt if it is proposed by someone with the power to pawn the last shoe button. To foreigners, the proof of who has what power is much more certain if written down. Morris's protege Alexander Hamilton went even further: "credit" is established when creditors can see that somebody is in the habit of getting the nation's bills paid, and "credit" is injured whenever anyone in charge, welches.

Our Federal Reserve : Biddle's Bank (2)

|

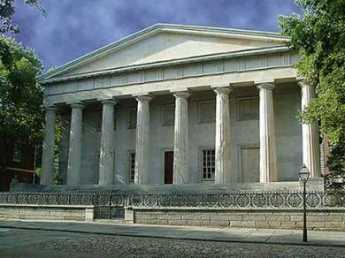

| Nicholas Biddle |

In 1823, the Biddles were prosperous, having made money in real estate (a Biddle ancestor had been a member of the Proprietors), and influential, having been Free Quakers who sided with the Revolution. So, Nicholas Biddle became the president of the Second Bank at 4th and Chestnut. Like all banks, he was given the ability to create money by taking deposits and loaning them out. Since in this process, two people (the depositor and the borrower) think they have the same money, there is effectively twice as much of it -- unless both actually demand it at the same time. If a bank has Federal revenues on deposit, as Biddle did, it is fairly easy for a politically active banker to predict whether that large depositor is likely to withdraw it. Political deposits seemingly make a bank stronger and safer, unless the banker has a fight with a politician. That's banking, but Biddle also became a central banker.

Biddle had ideas, derived in part from Alexander Hamilton. In those days, banks issued their own paper currency, or bank notes, representing the gold in their vaults or the real estate on which they held mortgages. There was a risk in one bank accepting bank notes from another bank that might go bust before you changed their notes into gold. The further away the issuing bank was, the riskier it was to rely on it. So, it was important to be a friendly sort of banker, who knew a lot of other bankers who would accept your money or who were known to be trustworthy.

Nicholas Biddle himself was well known to be pretty rich, and utterly trustworthy. He had a good instinct for how much to charge or discount the banknotes from other banks, or even other states. It was quite profitable to do this, but it became even more profitable when people began to use Biddle's own bank notes because they were safe. By setting a fair standard, he could control the exchange rate -- and hence the lending limits -- of banks that dealt with him. Sometimes a distant bank would get into cash shortages, and Biddle would help them out; if the other bank had a bad reputation, he might not.

|

| Bank of the United States |

In this way, the Second Bank was a reserve bank for other banks, with its banknote currency coming close to being the currency for the whole country. Soon, within a few blocks of Biddle's Bank, there were dozens of other banks, making up the financial capital of the country. Although it was a little obscure, and even Biddle may not have completely realized what he was doing, in effect his system automatically adjust the amount of currency in circulation to the size of the economy. If the correspondent banks prospered, they issued more currency, and if there was a recession, the country had deflation. The volatility of this system was related to the volatility of a pioneer economy, so Biddle made lots of enemies whenever he guessed about the direction of the economy. It wasn't a perfect system, but at least he kept politicians from inflating the currency to get re-elected, and hence annoyed politicians by constraining them. During the great western land rush of those days, all banks were under pressure to issue more loans than was wise, and politicians were under pressure to make them do so.

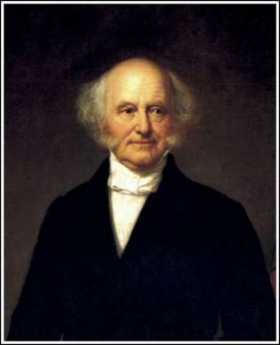

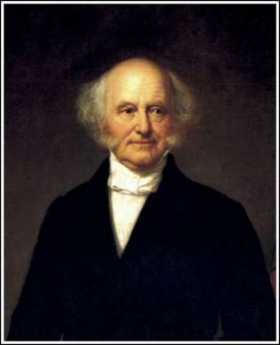

The worst enemy Biddle made was Martin Van Buren of New York. Van Buren was a consummate politician, one of whose many goals was to move the financial capital of the country from Chestnut Street--to Wall Street.

REFERENCES

| America's First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder after the Panic of 1837 Alasdarir Roberts ISBN-13: 978-0801450334 | Amazon |

Our Federal Reserve: Okayed (3)

|

| Martin van Buren |

The 8th President of the United States, Martin van Buren, was born in Kinderhook, New York along the Hudson. He was known as "Old Kinderhook", so in time he initialed his documents "OK", and that's how that slang term originated. It's also of note that his retirement home in Kinderhook was named Lindenwald, although any connection with the terminus of the PATCO high-speed line is unclear. His real claim to fame is that he sort of invented what we know as the a modern political system, particularly that unfortunate doctrine known as the "spoils system". The full allusion is "to the victor belongs the spoils". The two-party a system, the Democratic Party, spinning, log-rolling, and other clever manipulations were of his devising. He must have been pretty shrewd, having defeated De Witt Clinton for Governor of New York, when Clinton was known as one of the most ruthlessly ambitious politicians around. Recognizing he was unlikely to be elected President, van Buren took on Andrew Jackson the war hero and manipulated him into the presidency, with the clear understanding that when Jackson stepped down, van Buren would have the job, next. Van Buren was a cabinet officer during Jackson's first term and Vice President during the second term. During that time, he was the real power running things from the shadows. He ruined the careers of John Calhoun and Henry Clay, regularly taking both sides of a number of disputes over the extension of slavery into new Western territories. What people ultimately thought of all this may be judged from the fact that he ran unsuccessfully for re-election -- three times.

It is therefore not certain just whose ideas were in operation when Jackson blocked the re-chartering of Biddle's bank, but one main benefit, "cui bono?", went to New York. Wall Street had sold stocks under a Buttonwood tree for fifty years, but its real start in the the financial world can be traced from Jackson's action.

The Industrial Revolution and the expansions of the United States by the Louisiana Purchase, the annexation of Texas and the Mexican acquisition caused an an explosion of new wealth, and hence an urgent need to make some better financial alignment of three asset classes: land, precious metals, and currency. Everywhere and at all times it is arguably what the land is really worth; 19th Century America it was particularly speculative, because there was so much of it. Most of the many bank waves of panic during that century can be traced to excessive borrowing to speculate in raw land. When Jackson closed Biddle's reserve bank, the land the speculating public was ecstatic because of any constraints on the lending power of banks made it harder to sell real estate. But what had been done was to eliminate the only reasonably effective way of matching the a true wealth of the country with its circulating monetary assets, and after a brief boom, the almost certain consequence was going to be a national bank panic. It came in 1837, during the first year of Martin van Buren Presidency.

The only imaginable alternative to a market-based monetary system is a government-based one. Van Buren's political behavior was by almost by itself sufficient warning of the danger of allowing politics into this matter. For nearly a century, one warning was enough.

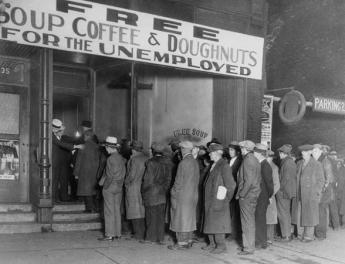

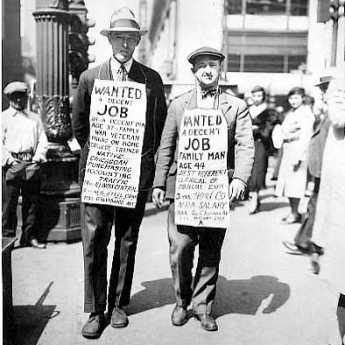

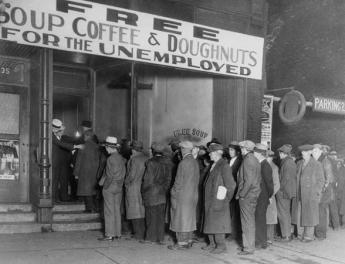

Premature Solutions to the Credit Crisis of 2007

One of the things being said in Academia in 2008 is that the 1929 crash was the result of many futile attempts to preserve the gold standard. That's the first time that particular formulation has surfaced in eighty years. It may not be correct at all, and even if correct it doesn't say what should have been done about it. Life is short and the Art is long, but somebody must do the best he can with the information available. Unemployment was over 30% in those days, and hundreds of Americans froze to death in the Depression because they could not afford to heat their rooms. Right or wrong, there are times when some action must be taken. But if you can possibly sit tight and figure out a sensible thing to do, it's certainly better.

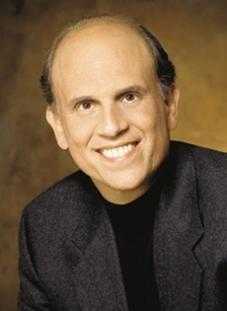

So, we hear proposals from Henry Kaufman to create a separate Federal Reserve for big institutions alone, while others say banking oversight is already too fragmented between the Fed, the Controller of the Currency, the Secretary of the Treasury, the FDIC, state banks and national banks, the SEC, the Bureau of Management and Budget, and on and on. This line of argument takes the formulation that we should regulate mortgages, no matter who is involved in them, rather than banks, on non-bank institutions. On one point everyone is in agreement, that we need more information more quickly, more transparency, less asymmetry of information. At the same time, everyone is aware that it probably will eventually be possible to describe this whole mess on one sheet of paper; the truth is totally hidden by information overload. Don't talk so much; say something.

At the GIC (Global Interdependence Center) recently, a brilliant professor of the Wharton School gave a magnificent summary of the situation, now nine months old, enumerating a number of insights which had not even occurred to an audience of bankers and businessmen. They applauded enthusiastically, and then someone asked how Credit Default Swaps fit into this picture since they had not been mentioned. It immediately became embarrassingly evident that the professor knew almost nothing about that topic beyond a couple of pat sentences. But Credit Default Swaps now total trillions and trillions of dollars, more than doubling in a year. Since they are private transactions unreported to regulators, no one has measured the matter or will divulge what has been measured. But since they represent a volume several time the size of the underlying debt market, and every swapper swaps with someone else, it seems inevitable that huge imbalances exist somewhere. It would be nice to have a general idea out of whose pockets the excesses come, and into whose pockets they go. Maybe all this is irrelevant to the present crisis, but it isn't irrelevant to the distrust and fear in the markets. If someone proposes a law about this situation, he had better have divine guidance.

An example of what causes markets to freeze up because people are afraid to buy, comes from an anonymous person in an elevator. Speeding between floors, he remarked earnestly to a friend, that when he worked for Goldman Sachs his department churned out dozens of innovative debt instruments. If one of them happened to get popular, then and only then did they set about devising ways to measure them, and adjust the prices. It's impossible to stop rumors of this type because they sound so plausible. In fact, they may even be true.

In fact, some of the most incisive comments come from people with no insider information at all. Such as a businessman who listened intently to the lecture and then called out, "Where were the accountants in all this? Aren't they paid to know what is going on?" The answer was that FASB rules should be tightened up. Maybe so, but it sounds a little thin.

The political risk is considerable. Only 6% of the population is old enough to remember 1929 and its aftermath, only 25% more can remember 1973, and 25% more can remember 1991. That means that nearly fifty percent of the public can never remember a severe recession at all. A politician running for office could tell them anything, and they would have no reason to challenge it. Or put it this way: the advisors who elected a young President could tell him anything, and it isn't certain he would fire them for it.

Macroeconomics of The 2007 Collapse

Sudden wealth creation, whether from the discovery of gold or oil, the conversion of poverty into useful cheap labor, or the sudden abundance of cheap credit, is of course a good thing. Sudden wealth creation can be compared with a stone thrown into a pond, causing a splash, and ripples, but leaving a somewhat higher water level after things calm down. The globalization of trade and finance in the past fifty years has caused 150 such disturbances, mostly confined to a primitive developing country and its neighbors. Only the 2007 disruption has been large enough to upset the biggest economies. It remains to be seen whether a disorder to the whole world will result in a revised world monetary arrangement. One hopes so, but national currencies, tightly controlled by local governments, have been successful in the past in confining the damage. This time, the challenge is to breach the dikes somewhat, without letting destructive tidal waves sweep past them. Many will resist this idea, claiming instead it would be better to have higher dikes.

It is the suddenness of new wealth creation in a particular region which upsets existing currency arrangements. Large economies "float" their currencies in response to the fluxes of trade, smaller economies can be permitted to "peg" their currencies to larger ones, with only infrequent readjustments. Even the floating nations "cheat" a little, in response to the political needs of the governing party, or, to stimulate and depress their economies as locally thought best. All politicians in all countries, therefore, fear a strictly honest floating system, and their negotiations about revising the present system will surely be guilty of finding loopholes for each other; the search for flexible floating will, therefore, claim to seek an arrangement which is "workable".

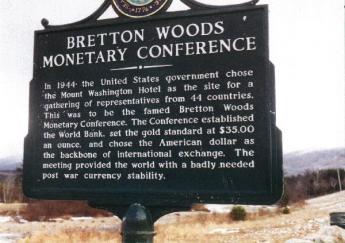

In thousands of years of governments, they have invariably sought ways to substitute inflated currency for unpopular taxes. The heart of any international payment system is to find ways to resist local inflation strategies. Aside from using gunboats, only two methods have proven successful. The most time-honored is to link currencies to gold or other precious substances, which has the main handicap of inflexibility in response to economic fluctuations. After breaking the link to gold in 1971, central banks regulated the supply of national currency in response to national inflation, so-called "inflation targeting". It worked far better than many feared, apparently allowing twenty years without a recession. It remains to be investigated whether the substitution of foreign currency defeated the system, and therefore whether the system can be repaired by improving the precision of universal floating, or tightening the obedience to targets, or both. These mildest of measures involve a certain surrender of national sovereignty; stronger methods would require even more draconian external force. The worse it gets, the more likely it could be enforced only by military threat. Even the Roman Empire required gold and precious metals to enforce a world currency. The use of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) implies attempts to dominate the politics of the IMF. So it comes to the same thing: this crisis will have to get a lot worse, maybe with some rioting and revolutions, before we can expect anything more satisfactory than a rickety negotiated international arrangement, riddled with embarrassing "earmarks". Economic recovery will be slow and gradual unless this arrangement is better, or social upheavals worse, that would presently appear likely.

Federal Reserve Rolls the Dice

|

| Lehman Brothers |

For the year preceding, it was general opinion that the financial crisis was caused by $100 billion or so of mortgage-backed securities, mostly California and Florida home mortgages. But around Labor Day 2008 Lehman Brothers collapsed, and the problem became twenty times as large. What that was about is unclear, but seemingly had to do with money market funds being treated as "funds in transit" in consequence of the international monetary agreement known as Basel I, and thus not requiring bank reserves to be maintained for them. It will take time to unravel the intricacies of, and assign the blame for, this mess. However, the markets responded by refusing to trade at now uncertain prices, thus "freezing up". The response of the Federal Reserve was to double the money supply through international markets, mostly using "Central Bank liquidity swaps". The participation of various countries in this action has not been made public.

The doubling of the money supply required borrowing between one and two trillion dollars. After five months, or just after the inauguration of the new Presidential Administration, the markets had seemingly started to function more normally, and the stock market had rallied somewhat. The obviously bewildered leadership of both political parties agreed to the proposal to purchase $1.75 trillion of the troublesome assets, taking them off the market and presumably hoping the markets would function as if they did not exist. By July 2009 this operation was only about half completed. Not only was there disagreement about what these securities were really worth, but the banks which held them were reluctant to allow prices of what they continued to hold to be driven down by comparison with these forced transactions.

|

| Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia |

In any event, the second stage of this huge government bailout of the banking system is projected as follows: The portfolio of assets would be worn down, either by allowing debts to mature, or by selling them at what is hoped will be advantageous prices. Who will buy them is to some extent dependent on the state of the economy, and to some extent on the perception of the fairness of the pricing. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has been assigned the task of designing a public formula for how much to buy or sell, depending on selected indicators of the economy. A public formula is felt to be necessary in order to reassure the markets that purchases and sales are not being made in response to secret information or unsuspected problems.

The reasoning would be that if these assets are sold to speculators at fire-sale prices, the money supply will shrink inappropriately, and the recession will be prolonged by the need to borrow replacement reserves for the monetary system. Unduly profitable sales would probably lead to inflation, since the present level of monetary reserves is twice as large as was thought appropriate, as recently as a year or two ago. But this maneuver by a central bank has never been tried before, and the results may well differ from present predictions. The Federal Reserve is prepared to take as long as ten years to accomplish the complete maneuver, but that plan presumes ten years of recession and five congressional elections. It also implies that the economy could swing between 7% annual inflation, and 7% annual deflation, in the two worst cases, and assuming nothing extraneous happens to the economy.

|

| President Barack Obama |

In the meantime, two other ominous notes. Although the nationalities of the lenders have not been made public, one can safely assume the Chinese are a major component. Since they are refusing to lend us money beyond two, and at the most five, years, we would be indefinitely in the position of borrowing short and lending long. In other situations, that imposes a risk of depositors starting a run on the bank. And secondly, it is hard to imagine that Mr. Obama's presently ambitious programs in healthcare, environmental protection, two wars and several election cycles, will be allowed to proceed without enormous public resistance to even further fiscal deficits.

After a Year of Crisis, Fannie and Freddy Finally Get the Spotlight

|

| Freddie Mac Corp. |

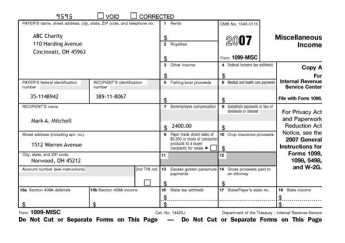

A year after potential financial collapse burst on the scene, the public (and Congress) are beginning to understand what collateralized debt obligations (CDO) are, and how Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac work. It begins to seem they are much the same thing in different clothes, that securitization of mortgages began with Fannie Mae if not Farm Credit in 1916, and that these bewildering new Wall Street CDO creations are just new variations of an old idea. The devil, as always, is in the details.

|

| Freddie Mac Corp. |

Originally, Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSE) began in 1916 with the Farm Credit System and entered the home mortgage secondary market in 1938 with the creation of FNMA (Fannie Mae). Populist in the first case and Depression-fighting in the other, the idea was that third-party reinsurance would make mortgages safer, and thus lower interest rates for a favored population segment (farmers and homeowners). Although no promises were made to bail out failing loans, GSEs eventually grew large enough to seem able to force the government to rescue them in the event of failure. They were claimed to be "too big to be allowed to fail". In addition to this implicit government backing, there was a twist created by making debt interchangeable with equity. "Securitization" was a process of bundling many mortgages into a package sold to the public as a stock issue. Since FNMA was a creditor, rising interest rates created profits for the shareholders, while falling interest rates depressed share prices. Steady predictable mortgage prices could be offered to homeowners, while the risk was transferred to the shareholders. To a certain but much lesser degree, some of the risks of falling real estate prices were transferred to the shareholders as well. Finally, the reduced risk in this arrangement led to lower prices for mortgages, regardless of the state of the economic cycle.

|

| Michael Milken |

To some unknowable degree, enthusiasm for mortgage-backed securities in the private sector was enhanced by fear or even loathing of government involvement in the financial system style of banana republics or the Weimar Republic in 1922. To compete with the lower interest rates of government-backed security, the efficiency of the private sector could be combined with innovations made possible by the computer. Mathematical models were devised to calculate mortgage interest rates by working backward from the default rate in a huge universe of mortgages. During the savings and loan crisis two decades earlier, Michael Milken had promoted the idea that prevailing interest rates on mortgages were higher than were justified by the prevailing rate of default in a large pool. If the uncertainty of risk for a single mortgage could be submerged within the fairly certain risk of a large pool, it should be possible to offer generally lower prices than even those of the government-backed GSE system. In spite of the recent panic, the reasoning behind both systems, government and private, seemed to suggest that securitization of debt continues to be a sound idea.

What appears to have been unanticipated was that house prices would rise in a bubble stimulated by a flood of money from the Far East and the Middle East. When that bubble inevitably burst, the resulting drastic decline in house prices would trap everyone who had borrowed a fixed amount as a mortgage at the top of the real estate market. Those who bought and held their houses before 1980 could ride out the gyrations of the real estate market, but everyone who bought an overpriced house after that was at risk that prices would eventually return to normal -- and bankrupts them with that high fixed debt. If these people outnumber the rest of the country, they can use their voting power to force the rest of the country to bail them out, but that's the way civil wars get started. It remains to be seen whether some political compromise can be arranged between those who bought houses at foolish prices, those who felt enriched by owning more valuable houses, and those few who watched with dismay.

Meanwhile, there is another important decision to be made, as to whether to permit either form of securitization to be used as an American scapegoat for a mess caused by Chinese prosperity. There is indeed much to be criticized in retrospect about the conduct of Main Street, Wall Street -- and K Street.

A Single International Currency?

|

| It's Only Paper |

The Economist, printed in London, refers to the United States in its October 17, 2011 edition as the "World's largest currency union", but goes on to state it only became a true currency union in the Presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. That's sort of the case, even though most people suppose Alexander Hamilton unified American monetary affairs with the Compromise of 1790 which among other things traded the nation's capital away from Philadelphia. No, Hamilton only unified the Revolutionary War debts, which to be sure, at that time were the main debts of the new nation. In time, the country and the economy grew in size until our currency was no longer unified because the individual states and banks were legally free to issue their own money. Nicholas Biddle of the Second National Bank had an irritating habit of buying up the circulating currency of a weak bank and presenting it as a bagful to the teller's window. If the bank was really overextended, it then went bankrupt, and other marginal currency-issuers could observe a bitter stress test about printing unreserved paper money. According to The Economist, the main stabilizer was not a migration of money, but the migration of workers. Unemployed people by the many thousand would move to a state or territory with a labor shortage, a solution made practical by the extremely low cost of real estate. In Europe, a far more practical adjustment remains the moving of funds from one state to another, although there is today enough migration across the Mediterranean to demonstrate how disruptive it is to mix extremes of unwelcome language, religion, and culture. In comparing the American and European experiences we thus have two quite different systems to compare, although distinctive conditions often bring out the main issues. The problem of maintaining a common currency union, for example, is hard enough, while the Europeans have the similar but not identical problem of devising a stable one from a large number of different ones.

After three hundred years of fumbling America has perhaps muddled through to a currency union that works. Resting on the fact that most Americans are either debtors or creditors and the rest mostly don't care, the quantity and value of American dollars since 1913 have been negotiated between banking and the U.S. Treasury with the Federal Reserve as umpire. During that last century we have endured two major depressions and a dozen recessions, abandoned the gold standard and fought a number of wars; but the American currency union has never given serious signs of weakness. It would appear that the main problems with currency unions appear at the beginning, in putting them together. After the transition, things appear to get easier. Bank profits are improved by higher interest rates, while all governments, perpetually in debt, want lower ones. Ultimately, of course, the real tension is between the creditors and debtors, but banks and Treasury seem adequate surrogates. Most creditors place trust in the incentives of banks to prevail, debtors trust government; both sides should have learned trickiness in endless negotiations is futile. What was once a battlefield, is now mostly peaceful; these people actually respect each other. Many people may occasionally dislike an outcome, but all acknowledge the tension produces legitimate compromise.

|

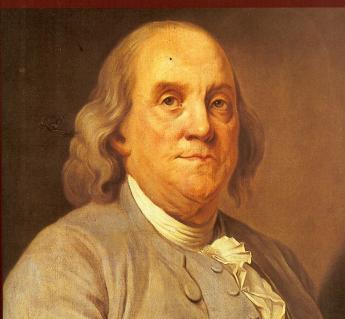

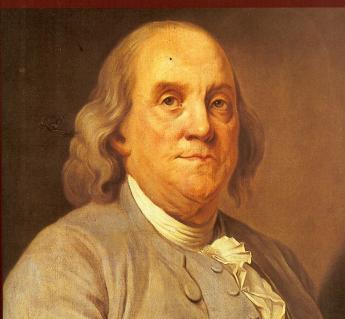

| Match Wits with Ben Franklin |

Aside from some "don't ask, don't tell" mystery that somehow compels assent by regions of the country who feel betrayed by agreements their representatives have made, negotiating postures are pretty simple and clear. It is safely assumed the government wants to inflate; all governments have done so for thousands of years. Therefore, the basic Federal Reserve policy of targeting interest rates to restrain inflation is probably a concession to banks. Banks would mostly want the highest rate that does not cause a recession. Debtors do not mind lower rates leading to just a little inflation, hoping to pay off their debts later with cheaper money. Government, acting as an agent for debtors, additionally knows that rampant inflation loses elections and occasionally, as in inter-war Germany and Austria, destroys the middle class. So, with everyone else resisting inflation, debtors must be satisfied with 2% annual inflation. That's arbitrary, reflecting its origin in the haggling process. Inflation-targeting plus two percent; that's the system.

If only there weren't all those other countries in the world. If they inflate or deflate, we could just float our currency exchange rate to maintain international trade; that isn't so bad, although frequent readjustment of prices is a costly nuisance. But if some country freezes its currency at an unrealistic price, speculators will move money around to take advantage. Enter Gresham's Law (commonly expressed as "Bad money drives out the Good".) Gresham's original phrasing is actually apter: "When two currencies of unequal value circulate together, the good currency quickly disappears." So, when truant governments cheat on currency values, well-behaved countries find their own currency getting hoarded. Potentially, that leads to currency shortages, as happened to Argentina when Brazil devalued in 1999. So, countries running an honest currency nevertheless feel pressure to print more; Brazil "exported its inflation" to Argentina. Plenty of wars have been started for less provocation. When something causes that extra money to come out of hiding, there will be spreading inflation, notwithstanding attempts to isolate foreign inflation by the central banks of more responsible nations. Furthermore, runaway inflation can unsettle governments, as it did in the Argentina example, going from one extreme to the opposite. There is thus wide-spread sympathy for currency unions, even though locally independent currencies can sometimes better adjust to local commotions, typically by devaluing the currency and then rejoining the currency union at a more realistic price. The Federal Reserve in our case would be forced to raise interest rates sky high, promptly triggering housing and stock market crashes. So the point returns; if our Federal Reserve system works so well, why can't everybody does the same thing on an international level. In fact, what's the matter with having one big world currency?

Maybe, some say, we could have a World Reserve Bank, issuing a common international currency. What we now have in place is U.S. money serving as a Reserve Currency for the world. The force behind this system is again Gresham's Law, that since we have the strongest currency in the world when it circulates in other countries in the company of weaker local currencies, it quickly "disappears". That is, it is hoarded out of sight until nothing but local money remains visible. Under these circumstances, only the United States with the world's Reserve currency is able to print money without creating inflation. Unfortunately, that implies that if it should ever weaken, it will quickly reappear and flood the host country with inflation, whereupon the host government will ship it all back to enjoy your own inflation, thank you. Thus, being the reserve currency for the whole world allows you to have some inflation and ship it abroad, but if it ever comes back home, there could be a painful disruption. The last time this happened was when the British Pound surrendered the reserve role to the American dollar. It was a bad time for the British economy.

The question periodically arises whether it might be better to use a "basket" of currencies as the reserve against temporary monetary shortages, with the United States trading away some of its free ride on inflation in return for reducing the risk of someday getting it all back at once.

Using a basket of everybody's money as a pool of international reserves might smooth out the tidal waves, but it probably would not create the same stability from tempests we enjoy with the Federal Reserve. If you regard a country's money supply as one big short-term bond, then a basket of currencies is a basket of bonds, issued by a world full of debtors. In that situation, pressure for worldwide inflation is inevitable. In a world with nationalized banks and/or subsidized banking systems, it is hard to imagine any international banking voice without a strong political component. Mandatory contributions of gold bullion might be considered, but it is hard to think of an adequate substitute for the flexibility of adversary tension between permanent creditors and permanent debtors. The situation is not permanently hopeless however, just remote. The enduring risk is that some nations always have more to lose from a collapse of trade than others. Continuing improvement in world economic conditions may one day make a unified world currency feasible. As St. Augustine famously said, "Make me chaste, but not yet."

REFERENCES

| Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution, David Waldstreicher ISBN-13: 978-0809083152 | Amazon |

European Common Currency

|

| Christian Noyer |

Philadelphia had the recent pleasure of a visit by Christian Noyer, the Governor of the Banque de France, offering to a Federal Reserve Bank audience a view from inside the Eurosystem's monetary policy. Mr. Noyer was a designer of the Euro, or common currency of Europe. A charming and polished man of education, he brought along a document which hangs in his office, dated June 5, 1779, signed by John Jay on behalf of the Continental Congress, sent to Benjamin Franklin to give to Caron de Beaumarchais. Since Independence Hall is visible from the upper windows of the building where he was speaking, it was a charming touch.

|

| European Central Bank |

The European financial system consists of one monetary policy, set by the European Central Bank, but twelve (soon to be twenty-five) fiscal policies, set by the various governments. This was once thought to represent a major difference from the American Federal Reserve, but in fact, it hardly matters. Our fifty component states are not permitted to run deficits, but our federal government runs deficits, plenty of them, and it turns out to make little practical difference if a Central Bank must float bonds to pay for a deficit arriving in one envelope or twelve. What matters is the size of the total. From that starting point, the central bank struggles to modify matters to restrain inflation, or combat unemployment. The main tool at the bank's disposal relates to the fact that governments no longer fear to print more money than they can redeem in gold. They print money, all right, but the spigot is now turned down when inflation begins to appear. In theory, at least, inflation is not possible if the central bank is able to maintain this policy. Of course, if money created in the past comes flooding in from abroad or out of mattresses, there might be a problem. Central bankers seem like terribly powerful people until you count up the people they can't control. The first is the politicians who create those deficits.

European politicians believe their constituents prize security above all else, a condition known as socialism. High taxes, high unemployment, and slow economic growth are considered more tolerable in Europe than sacrificing pensions, health care, and other features of the social safety net; out of this come government deficits, then maybe inflation. The central bank is told to make the best of it.

Then, there is the long-term bond market, which in the past responded to a flood of money by reducing the value of outstanding bonds, which results in higher interest rates.

|

| Euro |

Recently, however, long-term interest rates have failed to rise in response to rising deficits, and speculation abounds as to why that should be so. It creates uneasiness to hear that the finances of the world are simply a "conundrum". And finally, foreigners will flee from an inflated currency, eventually triggering a devaluation. A few years ago, Argentina refused to devalue, but the result was a devastating recession when their foreign trading partners refused to deal with an unrealistic currency.

A government which refuses to respond to these "signals" from the bond market and foreigners, will be forced to take some undesirable actions. In Europe, it is to oppose globalization of the economy, thereby hurting everybody but especially poor nations. And the internal European unemployment is shifted as much as possible onto the backs of immigrants, even migrants from within the European community. Take that far enough, and you get serious threats to world peace. Even within the European community, many of the policies which protect the welfare state will consciously injure their own economic growth. Reform is resisted.

Many needed reforms are obvious to policymakers in Europe, and the American example would often seem to be convincing. But it isn't, because Europeans terrified of losing their welfare state recognize that the American model includes a large amount of contempt for socialism, no matter how otherwise successful it is. The interesting thing has been that the Scandinavian countries have an equally extensive welfare safety net, but have nevertheless prospered by adopting free-market reforms. There are signs that this experience is beginning to convince Europeans it is possible to work their way out of the dilemmas.

After his talk, which avoided mention of many of these concerns in the mind of his audience, Governor Noyer was even more charming in cocktail-party mode, but one thing made his face turn beet red. When asked what the John Jay letter was all about, he had to admit he hadn't the foggiest. It was just something hanging on his wall that seemed appropriate for a trip to Philadelphia.

Euros and Dollars

|

| International Money |

The United States government issues lots of different currencies. We issue ones, and twos and fives and tens and twenties. If you need more one dollar bills, you can walk into any candy shop with a five and the shopkeeper will more or less cheerfully make the exchange without charge. But if you want to change the same five dollar bill for euros, yen or drachma, you need to find an agent in a kiosk and pay a fee of about 3%. The booth or shop of the international money changer will have some sort of electronic means to tell what the rate of exchange might be at any given moment. To extend this idea, if the people at the mint run short of ones, they just print some more, meanwhile removing a comparable number of surplus fives from circulation. No matter how extreme the imbalance, it does not affect the price of dollar bills. That's more or less the idea behind the common currency in Europe and a major success. All countries of Europe want to join, nobody wants to leave.

But some things are lost in this obvious simplification of financial transactions; it has enemies. For one thing, the Federal Reserve or other central bankers can change interest rates instantly, but the rest of the economy has a certain amount of inertia. For example, banks typically deal in 90 day Treasury bills, so it takes them a month or two to catch up with the Federal Reserve as the old bills mature; in the meantime, they lose money. Almost all businesses have even longer legs than that. So during the lag periods, the national economy experiences inflation or deflation, which may represent the national interest at the moment, but in time things catch up and rebalance about the way they were before the central bank acted. Except for taxes, that is, and this specific attrition is one of the main arguments for eliminating the capital gains tax, or extending special allowances for banks and others who have short-term gains on price changes without effect on underlying values. The matter gets mixed up in domestic politics. Incumbents long for short-term inflation, nonincumbent challengers denounce it. Everybody welcomes a "strong" currency, everyone recognizes that a weak currency sounds pretty bad. Few, however, could defend their opinion. The people who benefit are the ones who can move fast, because there's usually a brief flurry of inflation or deflation, and then things go backward. People who can move huge amounts of money quickly are apt to make big mistakes in their hurry.

And so it is in the eyes of foreigners. Right now, the American tourist to Paris confronts a taxi charge of $120 for a twenty-minute ride from the airport to the downtown. Everything else, from thirty dollars continental breakfast to two hundred dollar dinners, seems comparably overpriced. Tourists with sticker shock return home to tell their friends all about it, just before the November elections. No doubt it has an opposite effect on Parisian shopkeepers and their acquaintances. But the tourist trade is comparatively minor, compared with major industries. Airbus was once giving Boeing a seriously competitive race for airliners, but now Airbus is contemplating possible bankruptcy if currencies do not soon readjust, and Boeing is laughing all the way to the bank. Stop a minute and consider what happens when you buy and sell a whole company. Now it's the reverse, and a group of European investors is considering buying Anheuser Busch, the largest American brewery. The producer of Budweiser beer seems extremely cheap to Europeans, just as the beer itself is cheap for European beer drinkers. And then just consider a personal note: the wife of Senator McCain, running for President, owns a huge chunk of Budweiser distribution. The pillow talk in that family is likely to focus on the unfairness of hostile foreign take-overs.

So, all in all, tinkering with the currency as a direct or indirect consequence of a banking crisis caused by overbuilding houses in the sunbelt, has potentially fearsome consequences. They must be added to effects on commodity prices, and revolutions in the banking system. Those two issues are next to be considered.

As Computers Displace Money, Trust But Verify

|

| The honking of the Horn |

The Internet has made computing power ubiquitous. No longer need individuals to be at the mercy of institutions with whom they do business. However, new habits are hard to learn, so individuals still hesitate to challenge institutions. Sophisticated but inexpensive software from companies like Intuit nevertheless makes it nearly effortless for humble customers to have every bill and transaction cross-checked for them, and actually, in the resulting arguments. Its high time balance was restored because computers do send out lots of errors which have the effect of creating or destroying wealth. Indeed, much of the current credit muddle grows out of abbreviated records systems, organized for the convenience of only one party in a transaction. The transaction system would be streamlined, not hampered, by more adversary challenge and cross-verification at the level of individual items rather than merely cross-footing the totals. Indeed, add the filtering of information by third-party intermediaries, plus monitoring by regulators, and a need for some defined fault-tolerance emerges from the hopeless complexity. We must restructure relationships to ensure that small errors are trapped and isolated, not allowed to aggregate to a point where a mysterious failure of the books to balance can bring enormous systems to a halt. In this article, we mention the vulnerability of banks, financial derivatives, the Federal Reserve system, and the health insurance system. If everything worrisome went wrong at once, it could be quite a mess.