Related Topics

American Finance After Robert Morris

Robert Morris can be fairly said to have made the American Revolution possible.

Dislocations: Financial and Fundamental

The crash of 2007 was more than a bank panic. Thirty years of excessive borrowing had reached a point where something was certain to topple it. Alan Greenspan deplored "irrational exuberance" in 1996, but only in 2007 did everybody try to get out the door at the same time. The crash announced the switch to deleveraging, it did not cause it.

As Computers Displace Money, Trust But Verify

|

| The honking of the Horn |

The Internet has made computing power ubiquitous. No longer need individuals to be at the mercy of institutions with whom they do business. However, new habits are hard to learn, so individuals still hesitate to challenge institutions. Sophisticated but inexpensive software from companies like Intuit nevertheless makes it nearly effortless for humble customers to have every bill and transaction cross-checked for them, and actually, in the resulting arguments. Its high time balance was restored because computers do send out lots of errors which have the effect of creating or destroying wealth. Indeed, much of the current credit muddle grows out of abbreviated records systems, organized for the convenience of only one party in a transaction. The transaction system would be streamlined, not hampered, by more adversary challenge and cross-verification at the level of individual items rather than merely cross-footing the totals. Indeed, add the filtering of information by third-party intermediaries, plus monitoring by regulators, and a need for some defined fault-tolerance emerges from the hopeless complexity. We must restructure relationships to ensure that small errors are trapped and isolated, not allowed to aggregate to a point where a mysterious failure of the books to balance can bring enormous systems to a halt. In this article, we mention the vulnerability of banks, financial derivatives, the Federal Reserve system, and the health insurance system. If everything worrisome went wrong at once, it could be quite a mess.

For the opening example, this article was written two days after the author discovered a sizable error in his stock brokerage reporting. It was in my favor, else I might sound less relaxed. Even so, the condescending stone-walling encountered was a powerful warning, since at the end of the day it proved to be entirely the fault of a software vendor for several brokerage houses. A few decades ago, a housewife would have been in a stronger position with her department store billing department because it was effective to refuse to pay the bill. Just try that today: the current practice of employing vendors to handle merchant billing soon separates the dispute from the circumstances of it. That's an underlying difficulty with all third-party arrangements; expedients selected to avoid a problem often make matters even more frustrating for the defenseless counterparty, who eventually longs for government intervention.

To a certain extent, customers have been forced to agree to this situation voluntarily, because of the mind-boggling complexity or greater cost of not agreeing. Until about fifteen years ago, it was conventional to place engraved stock certificates in a safe deposit box. Dividends were received as paper checks, endorsed and deposited in a bank. The bank microfilmed the checks, the customer could photocopy them.

|

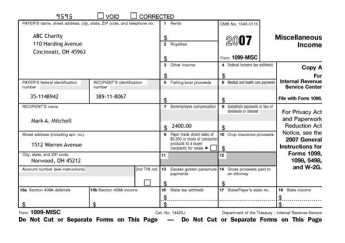

| Form 1099 |

Power was then reasonably symmetrical, arms-length and simple in concept even if overall it was an expensive, inefficient transaction. A mountain of receipts, a quarterly blizzard of mail. At tax time, an error-prone chore to manage the papers. So, in response to the gentle suggestions of tax accountants, it seemed heaven-sent to take certificates out of bank vaults and place them in "street name" with a broker. Tax time condensed to attaching a single piece of paper, the Form 1099, to the tax form. Instead of calling a broker and asking, "How's the market?" people now go to his website and review how a whole portfolio is performing, hour by hour. The efficiency gain is enormous; the transaction cost reduces at least 90%. But then -- you discover seven-figure errors can be created by an invisible computer programmer, initially denied as impossible and then defended with a blizzard of words. Worse still, the error did not come from an employee of the broker, it came from an employee of his software vendor in another city. The error did not surface in the brokerage house records, but in what was transmitted to a second software company a continent away, whose phone is answered in India. Two questions arise: what would have been the predicament if the error had been against me instead of in my favor? And secondly, what might have happened next if the misinformation about my imaginary windfall had been sent, not to a software house, but to the Internal Revenue Service as a Form 1099?

Now think of another order of magnitude. Instead of a housewife coping with the department store bill, replace her with a million brokers, a million investment bankers, a million electronic exchanges, and regulators, and tax collectors. Just one quantitative trader is known to handle ten thousand transactions an hour. Since transactions are global, a zillion foreign counterparties get orders for a zillion transactions. Underneath all this, a magnified error can emerge from one software vendor placing unwarranted faith in one programmer trainee, in a hurry to get home for dinner.

Originally published: Wednesday, December 26, 2007; most-recently modified: Monday, May 13, 2019