3 Volumes

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

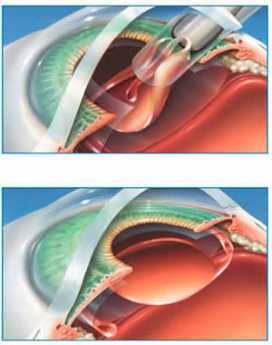

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

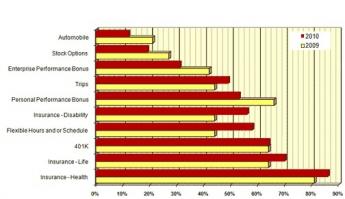

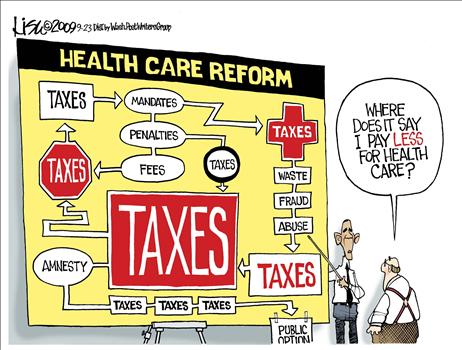

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Old Age, Re-designed

A grumpy analysis of future trends from a member of the Grumpy Generation.

1. Assisted Living Facilities .org 2. Home Health Care Agencies 3. AARP 4. Skilled Nursing Facilities 4. Home Health Agency Centers for Medicare 5. Administration on Aging 6. Adult Day Care

Redesigning Old Age

A friend of mine, treated as my contemporary but probably only sixty years old, was recently speaking of a club picnic he, unfortunately, wouldn't be able to attend. His mother was now living with him, and since she was 84, obviously neither of them could go to a picnic on a sailing vessel. The club committee, listening to this regret, chuckled that of course, we shouldn't expect him. My thoughts were somewhat different. Since I'm 94 myself, I was wondering if she was available for a date. And of course I am going to that picnic, why shouldn't I?

| You can't scare me very much about the future scientific costs of medical care. But Insurance and administrative costs are something else of course. If the problem of foolish borrowing puts Medicare out of business, it's hard to see how that could be the fault of my profession, unless perhaps something or other undermines our traditional system of ethics.

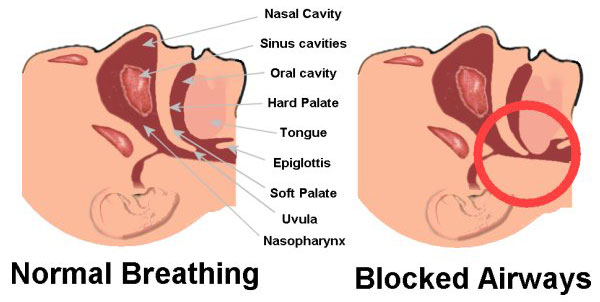

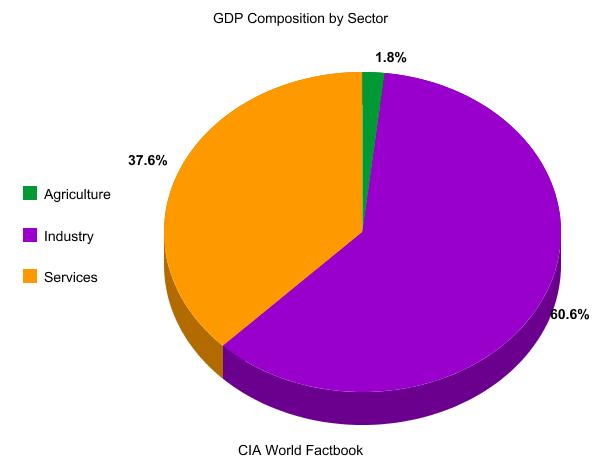

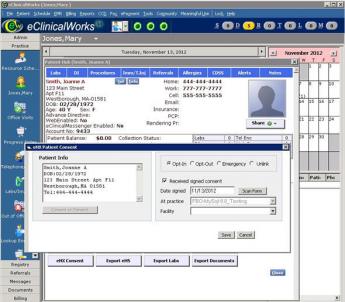

Where the ethics thing comes in is in the obvious conclusion that we are spending a lot of money treating diseases we crusty old docs once wouldn't have thought were worth our time. We are fast approaching the point when substantially all the medical catastrophic costs are concentrated in the first year of life and the last year of life. Increased life expectancy is a matter of widening the interval between those two signposts. Medical care between those years consists of treating the disease successfully, preventing disease and managing complaints we once would have dismissed as 'that's nothing'. Even the cost of doing this kind of medical care should decline: patents should expire equipment should simplify treatment should become standardized or even routine. But we notice people won't leave us alone: our government has just spent $27 billion forcing office computers on doctors who don't see the need to be bothered with them. People persist in using our time to inject botulism toxin into wrinkles and to listen to complaints about how lonesome they are. That is to say, the public is beginning to insist on substituting their own view of what they want, for what doctors have traditionally thought was worth treating. This is an expensive way to enjoy the freedom of choice and it is only a matter of time before bureaucrats figure out the least obtrusive way to curtail it. Only when forces come to equilibrium will it be feasible to extrapolate future health costs. What should appall us is the cost of paying for a progressively protracted retirement of so many unemployed people and the absolute impossibility of paying for it by continuing on our present funding path. Maybe that's what all this obesity means. Maybe people are trying to store up enough fat when they are forty, so they can go without eating from age sixty to ninety. A Time to Read Books

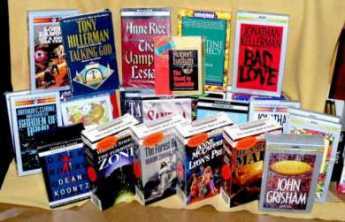

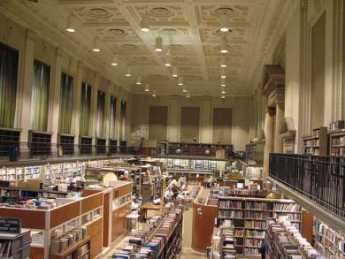

BEFORE we talk about retirees reading books in a retirement community, reflect for a moment about reading in your own home during the working years. Most suburban homes do not have many books in evidence. It's possible to stand in the center of most suburban living rooms unable to see a single book, while it's hard not to see a television set. Increasingly, a home computer is only a few steps from the front door, but the evolution from desktop to laptop to portable telephone to tablet is too rapid to make generalizations. Everyone says books are going to disappear soon, and newspapers maybe even sooner. But there are still said to be a million books constantly in transit on 18-wheeler trucks between print shops and wholesale depositories, night and day. Right now, the producers, publishers and merchandizers of printed material are in turmoil and decline, so they talk about it a lot. But ultimately it is the reading public which will decide what it wants and force the suppliers to give it to them.

It seems to me that what the reading public wants most is to find time to read. The suburban home has so few books because the sort of person who lives in the suburbs to be near the school system, just doesn't have time to read after the day's work and commuting. Helicopter parents spend a lot of time hauling the kids to mandatory kid entertainments, as can easily be seen by driving past a high school in the afternoon and observing the lines of cars with waiting mothers. They make the best of it as a social occasion for mothers with shiny cars, but they really do it to be sure the kids don't get mixed up with recreational drugs. Anyway, they do it, and it all eats up their discretionary time for reading. Meanwhile, their's no local bookstore to buy books, even unread books. They may think they will catch up on their reading after they retire, but that's becoming increasingly unlikely in my observation. They are getting out of the habit of reading. By the time they retire, they will find it's almost like going back to school. You must find other readers, readers groups, conversations about books over the bridge table, books lying about. The first economy a struggling news paper makes is to cut down the size and number of book reviews, because there are no bookstores to take out advertising, and advertising is what pays for newspapers. There's one good feature about that; what book chatter there is, is not so confined to recent books. Some people are bookish and other people are golf-ish, and a growing number of people are simply TV-ish. It's a struggle to find time for work and the family, and books on top of that. No matter what level of reading the working people may be doing, it's declining in favor of deferred reading when they finally retire.

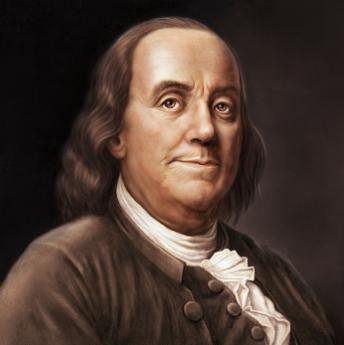

Having visited quite a number of retirement communities, I find the community's library is a good place to assess the institution and its typical inhabitant. When it's newly built, a library area is set aside, usually without many books. The first few waves of residents quickly fill up the space with books they brought from home. During the first ten years it is possible to guess what sort of person lives there by the books they brought and deposited, or died and left to the library. The space, more or less empty at first, gets full and something must be discarded. Enlarging the library is an economic issue, so the size at which it halts will to considerable degree reflect the willingness equilibrium to pay for new construction, both by the book lovers, and by the book enemies, the golfers and the administrators. Ultimately book congestion gets to the point where someone simply must cull out some old books to make room for the new. In another essay I have described the use of volunteers to exchange books of no lasting interest for more books of real interest to real residents, through a used-book exchange. But someone must organize the process, often recruited by an administrator who has learned to be horrified of construction which cannot be rented, but must be cleaned and cared for. If passive resistance is a new term to you, this is the place to learn about it. The residents have short memories, lack drive and follow-through. So inertia tends to win, and lack of reading feeds on itself because there is nothing to read. What's apparently needed here is an organization of bookish people that extends to all retirement communities, probably with a paid staff, an annual meeting, Internet connections. And therefore an immortality which can outlive and outlast the passive resistance. Good ideas then have a means to spread and help support other good ideas; somehow the costs must be supported until a few True Believers in Books can write a bequest in their wills to sustain it. And activate their intention, so to speak. One of the largely unrecognized reasons for the success of the American Revolution was that the Colonies had a higher level of literacy than the Mother Countries. Thomas Paine, for example, printed 150,000 copies of Common Sense on the rickety old printing presses of the 18th century, when there were fewer than three million white inhabitants of the thirteen colonies. And who was mainly responsible for that? It was Benjamin Franklin with his invention and popularization of the lending library. If Ben could find time to start libraries in 1742, and Andrew Carnegie was later found willing to pay for dozens of them, surely the time and energy can be marshaled in the 21st century to establish a first-class library system throughout the retirement communities of the nation. Retire LaterUnions teach their supporters: never retreat. Yell, shout, threaten, roll on the floor in simulated agony, denounce and declaim -- but never give back a single concession you have previously won. The hallmark of ratcheted positions about givebacks, is they are not negotiable.

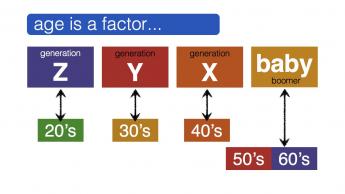

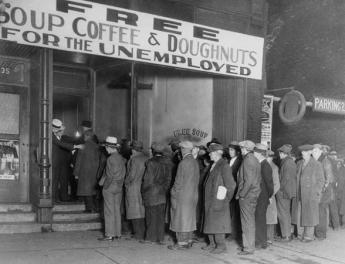

By having some personal contact with union officials, who are generally decent enough fellows when not in their negotiating stance, I have learned that, to them, advancing the retirement age is absolutely not negotiable. Some of this intransigence is fake, having to do with negotiating traditions, and some of it has to do with the equally traditional stance that work is some dreadful thing which has been inflicted on the working man by unfeeling employers, or management, or the rich aristocracy or somebody. Reflex belligerence is therefore triggered immediately by suggesting that people are going to have to work more than they expected to. Much as I hate to offend people in their deeply held religious beliefs, I bring the news that retiring later would immediately solve the problem of affording to retire and that no other proposal under the sun has greater chance of solving that problem. But it's like the Law of Gravity. When dealing with demographics, to declare that something is off the table, or unacceptable, or a giveback -- is just bombast. With the present data, we are going to have to re-set the retirement age to 70. If medical and demographic trends are unexpectedly extreme, we may have to go to 75. If you think someone has promised you can retire at 55, you had better be in an iron lung or drinking your meals through a straw.

It's easy to see that later retirement cuts lifetime costs in two ways: it increases the duration of earning and saving. And it shortens the years of retirement payout. The later you retire, the better it is. So the less you save, and the more lavish your lifestyle, the older you will be when you can afford to retire. A lot of things can be debated, and a lot of clever ideas can be worked with. But it is going to take an atomic attack or something similar to modify this particular prediction about the future. And even doomsday predictions just make the future look worse, not better. Because as the insurance salesman tells you, you can have it one way or the other. You can die too soon or you can live too long. Since you can't know in advance which it will be, you would be wise to work a little longer, just in case. Ageing Owners, Ageing Property

Kiyohiko Nishimura is currently the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), and as such is expected to have wise things to say about finances, as indeed he does. Japan has a far older culture than the United States, and a botanical uniqueness growing out of the glaciers avoiding it, many thousands of years ago. But its latitude is approximately the same as ours, and its modern culture is affected by the deliberate effort of the Emperor to westernize the nation, following its "opening up" by our own Commodore Matthew Perry in 1852. Perhaps a more important relationship between the two cultures for present purposes is that Japan has been suffering from the current deep recession for fourteen years longer than we have. We don't want to repeat that performance, but we can certainly learn from it. Mr. Nishimura lays great stress on the aging of the Japanese population because, in all nations, houses are mainly purchased by young newly-weds, and sold by that same generation years later as they prepare to retire. If a nation has an elderly population, it can expect a general lowering of house prices someday, reflecting too many sellers leaving the market at the same time. The buyers of those houses are competing with other young people, so the simultaneous bulges and dips of the population at later stages combine to have major effects on housing prices. At the moment, younger couples are having fewer children as a result of women postponing the first one. Nishimura goes on to reflect that something like the same is true of stocks and bonds, although at age levels five or ten years later. One implication is that retirement of our own World War II baby boom is about to depress American home prices, which will likely stay lower for 10-20 more years. Furthermore, our stock market will have a similar effect, stretching the depression out by as much as 5-15 years. The Japanese stock market has been a gloomy place to be during the past fifteen years, and by these lights might continue in the doldrums for another five or so. Meanwhile, our own situation predicts an additional generation of struggle while Japan is recovering. It's best not to apply these ideas too closely, of course, but surely somebody in our government ought to dig around in the data, at least telling us why we ain't goin' to repeat this pattern. Please. Perhaps because they eat so much rice and fish, the Japanese already have a longer life expectancy than Americans do, but in terms of outliving your assets, that's not wholly advantageous, the way a love of golf might be. The best our nation might be able to do is to examine some of our premises about housing construction. In Kyoto, most houses were built with paper walls, for example.

The house walls of the town of Kyoto were in fact made of waxed paper, which seems to work remarkably well. While no one now advocates going quite that far, we might think a second time about building the big hulking masonry houses so favored in our affluent suburbs. Such cumbersome building materials almost dictate custom building and strongly discourage mass production. How likely are such fortresses to survive in the real estate markets of fifty years from now? Judging from my home town, not too well. Haddonfield boasts it has been around since 1701, and there are at most three or four of its houses which have survived that long. We favor great hulking Victorian frame houses, with a good many bedrooms unoccupied, and high drafty ceilings, very large window openings and little original insulation. The heating arrangements have gone from fireplaces to coal furnaces, to oil, and lately to natural gas. The meter reader who checks my consumption every month tells me that almost all the houses now have gas heat, so almost all the houses are using their second or third heating plant, along with their eighth or tenth roof, and thirty coats of paint. This kind of maintenance is not prohibitively expensive, but just wait until the plumbing starts to go, and leak, and freeze, with attendant plastering, carpentry, and painting. Our schools and transportation are excellent, so we have location, location, location. But when the plumbing, heating, and roofing start to require financial infusions all at once, you get tear-downs. A tear-down is a new house in which a specialist builder buys the old house, tears it down, and looks for a buyer to commission the new house on an old plot of land. Right now, there appear to be six or eight such Haddonfield houses, torn down and looking for a buyer to commission a new house on that location, location. If we repeat the Japanese experience, there will be some unhappy people, somewhere. And that will include the neighbors like me, who generally do not relish languishing vacant lots next door, but fear what the new one will be like.

The thought has to occur to somebody that building the whole town of less substantial materials in the first place would be worth investigation, replacing the houses every forty years when the major stuff wears out. At the present, when a town of several thousand houses has five or six tear-downs, the neighbors would not tolerate replacing tear-downs with insubstantial cardboard boxes. Seeing what has happened to inner-city school systems, the neighbors would be uneasy about "affordable housing" built in place of stately old Homes of Pride. In time, that might lead to a deterioration of one of the two pillars of location, location -- the schools -- and hence to a massive loss of asset value. And yet when those houses empty out the school children, leaving only retirees in place, the schools will not be worth much to the owners or in time to anybody else. There's an unfortunate tendency for local political control to migrate into the hands of local real estate brokers, so you had better be sure any bright new proposal is tightly buttressed with facts. The only real hope for evolution in this obsolete system may lie in the schools of architecture, strengthened perhaps by some research grants. Countless World Fairs have displayed the proud products of their imaginative thinking, but mostly to no avail. Perhaps the ideas are not yet ripe, but since it would take more than a generation to create a useful demonstration project of whatever does become ripe for decision, let's start thinking about some innovative suburban designs, right now. Retirement CommunitiesPrior to the Second World War, old-age homes were almshouses, slightly modernized. Since few people lived very long after they retired, the old-age home took care of a few stranded old folks unable to care for themselves. The places were depressing and sparse, with a characteristic odor of urine and poorly-ventilated kitchens. But when time spent in retirement lengthened to twenty or more years, a new dynamic had to be considered. The dingy old single rooms changed into multi-room apartments, the dining room went upscale, and the infirmary changed into a skilled nursing facility. The idea was, you could graduate to more specialized medical care when you needed it, and be visited by your friends in the community who would someday be in the nursing facility themselves. They were paying to keep it up, and they would raise a ruckus if the infirmary service began to look uninviting. Whether the community was paying for it collectively or the younger generation was supporting it, the Retirement Village provided a more civilized way to grow old and die.

People chose these places for a variety of reasons, depending in large part on what they could afford. Widows are often overwhelmed by maintaining a house, widowers are often overwhelmed by cooking. And retired couples are often simply tired of both chores, or sufficiently crippled or befuddled enough to look for a way to give those tasks to younger people. One system grew up, of acquiring a second home in a vacation area and then replacing the main house with an apartment in a retirement community. If you stay in the vacation home for six months and one day each year, certain combinations can lead to appreciable tax savings. Sometimes a married couple is in perfect health and uses a retirement community as a comfortable suburban apartment complex, "just going on living the way we always did". The idea in their mind is the folk wisdom that you need to get used to a place and develop a circle of friends there; to do that, you ought to be less than eighty years old. When that's a general idea, it can be self-defeating to join a group of friends with pooled meal tickets. Thirty friends, or fifteen couples, can each host a party for thirty, once or twice a month. Unfortunately, they are quickly sequestered and disliked by everyone else as they make the regular rounds of nightly parties; but this sort of thing happens in upscale places, the kind of retirement community where some apartments have servants' quarters, and nobody much cares what anything costs. For people in this circle, the most detestable thing about a retirement community is the pressure to have dinner at 5 PM. Early dinner is ordinarily the surest sign the place is managed primarily for the convenience of the employees, but it can also mean there is nothing else to do except watch prime-time television.

For most people, however, even having ample funds for retirement is constrained by the uncertainty of how long the retirement will have to be, how much must be held in reserve, even at age 100. The gallows humor continues to repeat some version of trying to plan a way to spend your last dollar on the last day of your life. It isn't just how long you will live, it is how. If you or your spouse become blind, or bedfast, or in chronic pain, your level of living is going to change and your daily expenses may rise dramatically. Even if you never gave such gloomy things a moment's thought, the experience of eating in the same dining room with several hundred elderly acquaintances soon teaches all the lessons of unexpected illnesses and weekly funerals. Some people cannot bear the idea of living in such a community, for precisely the reason that it becomes impossible to kid yourself. And one thing no one can kid himself about is the reality that you have to have one awful lot of money before you can ignore the need to watch your pennies. And it isn't just your spending money; it's also the lack of a basement, attic, and garage in which to expand or from which to draw reserves, or just to enjoy old books and mementos buried in dust. Retirement communities seem to have developed independently in the Quaker suburbs of Philadelphia, and along the California coast. Except for the climate, there isn't much difference. More tennis in California, more trips to the theater on the East Coast. The early communities had a strong focus on finances, which assumed a lifetime retirement fund derived from selling the family home. The fancier the house, the more elaborate the apartment it would finance. As the duration of retirement grows progressively longer, roughly three years every decade, it is certain that the sale value of the average American family home will get progressively stretched to extend to the average age at death -- especially if you focus on the average age of the second of a couple to die, or become blind, or become bedfast.

So, the patterns of financing are changing, at least experimentally. Some retirement communities (the term is are purely rental, partly room and board, extra charge for the nursing facility, or a la carte for all services. People who enter any sort of community are often planning to move to a different one after a period of time, either to adjust to their reduced physical capacities or changes of location of their families. Some of them actually say they plan to live luxuriously and then move into their children's houses when the money runs out, although it is usually hard to know how seriously to take such comments. Obviously, what is needed is some sort of insurance mechanism to pool everybody's risks, but there is a fundamental problem. Insurance companies make a big profit on life insurance in two ways: either from clients who drop the policy before they cash it in or from premiums which underestimate the actual age of death compared with the average experience at the time the policy was taken out. But in the retirement case, essentially all policies mature at death and the duration for compounded investment is brief. So such insurance is either overpriced or unobtainable. The same underlying phenomenon affects Medicare and explains its impending insolvency. Those early retirement communities which based their charges on the assumption that Medicare would continue unchanged are repeatedly stranded when Congress cuts back on Medicare benefits. Someday, demographic trends will level off and insurance can be restored to practicality, but that time is certainly two or more decades away. Many states, including Pennsylvania, have passed laws that residents of retirement communities may not be evicted if they become impoverished, so the communities are forced to be strict about advance funding. Ultimately, the danger is that the community will be forced out of business, stranding the occupants. With so much time available to discuss such matters in a common dining hall, occupants of these facilities can become obsessed with the need to save for the future, and no one can be certain they are wrong about it. Retirement Communities (CCRC)Let's confess my meager authority to generalize about trends in retiree convalescence. When I graduated from medical school in 1948, average American longevity was twelve or fifteen years shorter than today, and most assumptions rested on it's remaining the same forever. Someone who reached eighty was really old, obviously facing a prompt decline. Today, essentially everybody lives to be eighty. We only half-expect such long life, which is modest of us, and only halfway plan for it, which is foolish.

In 1950 a general practitioner in Haddonfield, NJ called for help from the son of one of his patients. The son was a doctor on the staff of the Pennsylvania Hospital, where I was finishing my internship. The GP hadn't had a vacation for twenty years and wondered if one of the graduating internets might take his practice for a month. I volunteered and then learned about retirement in a prosperous suburb. My employer had many tasks, among them a schedule of ten or twenty monthly house calls. There may have been some male patients on those rounds, but all I remember were old ladies living on the third floors of big old houses. I wasn't expected to do very much when I visited, at least by Emergency Room standards in the hospital. The families with whom the grandmothers were living wanted to be reassured that nothing was neglected. They also wanted to form their own assessment whether the doctor really knew them, and would come immediately if needed.

My next insight came a few months later when another doctor on the staff of the hospital had a heart attack; the Chief of Medicine gave me the time off to take care of this practice while the doctor recovered. When I first arrived at the door of the brick Philadelphia row-house where the doctor had his office, I was met by his nurse already wearing a raincoat, handing me an umbrella. We visited ten or fifteen other row houses along the neighboring streets, where to my amazement I found patients with oxygen tents and intravenous infusions. If the patients needed blood tests or electrocardiograms, the nurse arranged for them to be performed at home. Drugs by injection were administered, hospital-like bedside charts were maintained. This was a working-class neighborhood substitute for hospital care, but I was astonished to see how adequate it was. By this time, we had many resident physicians at the hospital who had seen service in the war and returned for specialty training; they regaled us at the lunch table about treating major illnesses -- in a tent. This wasn't the Civil War we were talking about, it was 1950. Fifteen or twenty years later, my personal situation had improved; Medicare had arrived in 1965, but I was in practice as a center-city specialist and hardly noticed the new insurance system. But I did have three patients who insisted on being treated at home, which even by then had become an unusual arrangement. All three lived in condominium apartments in buildings with dining rooms on the main floor which would send up take-out dinners. All three patients had live-in nurses and hospital beds rented from an agency. One spinster lady absolutely refused to be treated in a hospital, because the Queen of England set up a little hospital in her palace when she needed it, and this lady said for practical purposes she had as much money as the Queen. Because she was dying of cancer, I resisted this idea, but if you had seen Katherine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story you got the helpless feeling this dame was going to have her way. We called in laboratory and x-ray services as needed, administered injections, maintained a hospital chart. In this case, when I made a house call, her chauffeur would pick me up and deliver me, helping to ensure my promptness. Her lawyer and I kept careful financial records of the experience, which was new to him, too. After she died, we totaled it up and discovered with astonishment that the whole thing had been cheaper, a lot cheaper, than going to the hospital. Since she left a sum to the hospital in her will, even the hospital was pleased. Well, nowadays there are more than fifty retirement communities scattered around the periphery of Philadelphia, many or most of them sponsored by Quakers. It's a national movement, and there are people in California who feel they had the idea first. There are now enough of these organizations to permit some classification of them into types, which mostly follows the sort of community model they resemble. There are some that look and are run like college dormitories, some that resemble convalescent homes, some are very like big-city apartment condos, and some behave like resort hotels. One of them, the Kearsley, sits in the middle of the Bala golf course, attempting to provide the first-class service to indigents by using existing government assistance programs, but has lately had to fall back on the Episcopal Church for financial help.

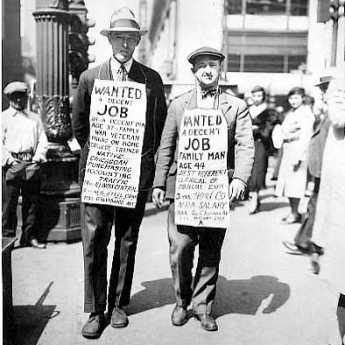

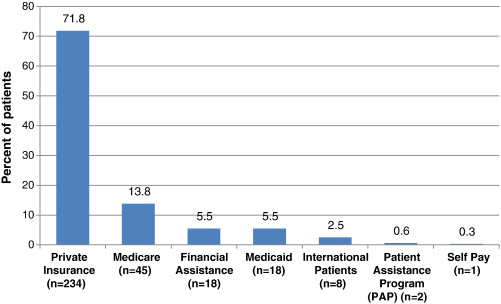

Since a financial shadow hangs over all of them, it should be mentioned first. Every person in a retirement village is eligible for Medicare and Social Security, and with the help of a social worker can fall back on less-known assistance programs. It's impossible to ignore the existence of these funds, but most unwise to depend on them. As the age and number of retirees constantly grow, state and federal governments are starting to draw back from initial generosity. Laws have passed that a CCRC resident may not be evicted for non-payment of debts, so the institutions have had to impose conditions which guarantee them payment from new entrants in the case of later inability to pay. The risk remains that clients who entered before the rules were imposed, can only be extricated by going before Congress and raising a piteous cry on bended knee. Such laws and embarrassments vary from state to state, and from year to year, but unstable finances destabilize any business. When the customers all depend on their savings, and average investment experience is a drop of 30-50% in the past couple of years, no one escapes anxiety. Although there must be college courses in how to administer a CCRC by now, current administrators are drawn from the environment the place mostly resembles, so the resemblance gets stronger. The former manager of a country club tends to neglect the infirmary; the former directress of a convalescent home doesn't notice institutional food. If the administrator treats customers as complaining nuisances, you get one kind of war; if the board of directors is accustomed to ruling corporations by dictate, you get another. Mainly, these institutions differ from models of other institutions by the degree to which they have active volunteers in charge. The inmates may run the asylum, but only if they become useful volunteers. A curious distinction evolves between those CCRCs which emerge from college alumni associations and those which are sponsored by churches. University faculties are not accustomed to, nor generally sympathetic with, teamwork. Every faculty member is on his own career path, which he hopes leads straight upward; teamwork to them is a code term used by business executives to imply blind obedience, Charge of the Light Brigade, or worse. Church groups, on the other hand, prize volunteerism. In a church environment, the proposal that Let's Have a Picnic is supposed to be met with a chorus of Great, I'll be Glad to Bake a Cake. Church-sponsored CCRCs, therefore, are generally more adaptive to innovation in a formless society. University groups have camaraderie and complaining, but little follow-through. By contrast, business people know what you are supposed to do, you are supposed to make something happen. Church volunteers want to know how they can help. Paradoxically for that reason, the more evidence of golf clubs around the place, the more likely it is to be innovative. Let's return to the point, succinctly. Life-threatening and potentially convalescence-requiring medical conditions are destined to segment increasingly into Medicare, to the point where what remains outside of Medicare is elective, preventive or outpatient. Obstetrics is an exception, remaining more naturally part of the hospital than the CCRC. The rest of medical care thus seems inclined to migrate toward the suburban ring of retirement communities. The more natural transportation flow is for younger people to travel to either a hospital-centered medical cluster or a CCRC-centered cluster, not for frail old folks to leave the convalescent environment except for major surgeries from which they soon return to their infirmary. It doesn't have to be that way, it just seems like the natural arrangement. Probably the main reason it doesn't work that way today resides in the Medicare law. The 1983 amendments restrained inpatient reimbursement much more than outpatient care or home nursing care, and consequently, inpatient costs have risen 18% in five years, compared with 47% for outpatient. Outpatient care is not migrating toward retirement communities because hospitals need revenue. Somehow, it seems easier to modify these reimbursement rules than to upend suburban CCRCs and relocate them next door to an urban hospital. If the payment rules become reasonable, the system will readjust its geography in a reasonable way, without coaxing. Surely, non-residents of the CCRCs are destined to wish to convalesce in the spare beds of CCRC infirmaries which should then treat younger people as a much-needed revenue source; any licensing requirements which block this seem unreasonable. Medical hardware,-- x-rays, MRIs and the like,-- is most naturally concentrated in the periphery of CCRCs, as are pharmacies, outpatient labs, doctors' offices. That's going to require a lot of parking space. It's a good thing this will take a couple of decades to happen; many mid-course adjustments will be imperative. But the basic fact is that the whole community's medical need is getting concentrated in CCRCs via Medicare, and so the community's facilities should move closer to that need. The younger community is well able to travel anywhere for elective medical services, especially when they move away. Makes a good chance to visit the grandparents while they are there, too. All of these proposals depend on getting the attention and cooperation of other self-centered institutions: Medicare, hospitals, medical societies, municipal governments. The CCRC community has scant experience with asserting itself; its future will depend on how skillfully it begins to do so. Nearly every retirement village has four or five retired physicians living in the place, as well as a dozen retired nurses, lab technicians, and others with medical experience. Every CCRC infirmary has four or five patients whose spouse is a resident of the community, visiting the infirmary regularly, and with sharpened insight. Some other people are natural leaders. If these people could be assembled into a permanent committee of medical oversight, charged with visiting other CCRCs in the region for ideas and perfecting the interface between the CCRC and nearby hospitals, medical facilities, transportation vendors, and politicians -- things would start to move. Spending twenty percent of our gross domestic product on health is, quite enough. Let's either stop spending so much or else make something good of it. Competitive Institutions: Paying for Assisted LivingAround the turn of the 20th Century, it was the fashion to build specialty hospitals, devoted to a single disease like tuberculosis or polio, or one specialty like obstetrics or bones and joints. Eventually, it was realized that almost any disease is handled better if a full range of services is readily available to it. Around 1925, some inspired philanthropists made it possible to combine specialties within a medical center, and it is now generally agreed this is a better way when population density permits it. On the other hand, it is likely a source of price escalation. Time marches on, and the problems of excessive bigness are also beginning to predominate. The idea immediately occurs, to winnow out the routine cases which do not need so much technology, so that we can concentrate and devote high technology (and costs) to patients who will really benefit. And, immediately the perplexing outcry is heard that such rationalization is "cherry picking", which will soon bankrupt the finest institutions we can devise. The validity of such assertions needs to be examined impartially.At the same time, the horse and buggy era has been left behind, causing new separations along class lines, the flight to the suburbs, and the migration of philanthropy toward the exurban sprawl, as well as into urban centers. In all this commotion it was overlooked for a long time that medical care was not merely following the patients to new locations, it was becoming more of an outpatient occupation. Inpatient care was shrinking, and somehow expensive hospitals were swallowing their smaller (and less expensive) competitors. It wasn't a necessary development; Switzerland still favors small luxury "clinics" of ten or twenty beds, usually containing wealthy patients of a celebrity doctor. Local customs like this will change slowly. What America appears to need is more hospital competition and more ambulance competition; the two may actually be somewhat connected issues. For amusement, I once studied the patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on July 4, 1776, when historical notables were congregating three blocks away. The diseases were remarkably similar to what is seen in hospitals today; problems with the legs, mental incapacity, major injuries, and terminal care. People are treated in hospitals because they can't care for themselves at home.

*******

Everyone knows Americans are living thirty years longer because of improvements in health care, and some grumpy people are waiting with glee to see if Obamacare will put a stop to that sort of thing. It must be left to actuaries to tell us whether the nation saves money or not by delaying the inevitable costs of a terminal illness. But one consequence has already made its appearance: people are entering retirement villages in their eighties rather than their seventies. Presumably, people in their seventies are feeling too well to consider a CCRC, although other explanations are possible. Accordingly, a great many CCRCs are seen to be building new wings dedicated to "assisted living". A cynic might surmise there must be some hidden insurance reimbursement advantages to doing so, but the CCRCs are surely responding to some kind of increased demand when they make multi-million dollar capital expenditures. Assisted living is a polite term for people with strokes or Alzheimers Disease, or some other condition making it hard to walk, or, as the grisly saying goes, perform the activities of daily living. One really elegant place in Delaware has suites with servants quarters, but for most people, the only affordable option is to be in a room designed around the idea of assisting an invalid. It's generally smaller and more austere but fitted out with railings and bars and special knobs. Meals generally have to be supplied by room service. Not everyone is destined to have a protracted period of decline, but it's fairly frequent and universally feared, so it's a comfort to know your present residence is attached to a wing which provides for it. The question is how to pay for it. There are two main approaches currently in use, adapted to the limited financial resources of the aged and the particularities of CCRC arrangements. In the first arrangement, there is no increased charge for moving to assisted living, which helps overcome resistance to going there. However, the monthly maintenance charge for others who remain behind in "ambulatory living" is increased, usually about 20%, to provide funding for those who eventually need special assistance. That's a financial pooling arrangement, sort of an insurance plan, and like all insurance, it has a tendency to increase usage unnecessarily. It also increases the cost to those who enter the CCRC at an earlier age, because they make more monthly payments before they use them. Although the monthly premium probably goes up as the costs rise with inflation, there may be some savings hidden in applying an earlier payment stream at a lower rate. That's called "present value" accounting, but like just about all accounting, its unspoken advantages and disadvantages contain a gamble on unknown future inflation. In the other common financial arrangement, you pay as you go, when and only if you actually use the assisted living quarters. Because of the likely limit to resources, there is usually an attached agreement to garnishee the initial entrance deposit if available funds prove insufficient. The one thing which won't happen is being thrown out in the snow for non-payment; there's a law prohibiting that. Bigger apartments with large initial returnable deposits are of course better off paying list prices. Those with smaller apartments may have smaller deposits, and favor payment by a percent withdrawal. Some places haven't thought this through and offer no choice. In that case, more attention should be paid to those list prices and the percentage markup from audited cost. Better still is to have a free choice of both options, with cost transparency. The remaining choice is between two CCRCs with differing options, made at the time you enter. The Obamacare fuss has made a lot of people acquainted with "adverse risk selection", which is largely based on the idea that an individual has a better idea of his health future than an institution does since that includes family history as well as earlier health experiences. But in general, a young healthy person is going to live longer without needing assisted living than an old geezer who going to need it pretty soon. A hidden adverse incentive is created for younger healthier people to set the choice aside, and come back in ten years, providing they remain alert to the underlying reason the monthly fee is then somewhat higher than in some competitive CCRC. At the far end of the age spectrum, an incentive is created to go into assisted living quarters a little earlier in life, generally regarded as an undesirable choice. All this financial balancing act can seem pretty overwhelming to an elderly person who isn't entirely comfortable with the CCRC idea in the first place. Rest assured that everything has to be paid for somehow, and after you die you won't care what choice has been made. If you trust the institution to have your best interests in mind, the only consideration of real importance is whether your money will last you out. The institution cares about that even more than you do, so while they aren't likely to offer unrealistically bargain choices, they may offer a few which are too costly. America has had a ninety-year romance with insurance because it is so comforting to be secure and oblivious to finances. This is just another example of the struggle between the search for a security, and the struggle to devise ways to pay for it. While no one can be positive about it, we're all in this together. Making the Whole Town into a CCRC

Probably because of cheaper land and construction costs, retirement villages are generally found in suburban or semi-rural regions. In Philadelphia for example, forty or so retirement communities dot the outermost edges of the city while the urban center contains only two or three of them. As was true during the migration of the national frontier Westward throughout American history, cheap land costs seem generally to overcome the attractiveness of urban habits and culture. Or at least that now seems a more universal theory of migration patterns than the attraction of suburban schools for the parents of teenagers. It has generally been argued in the past that the automobile made it possible for families to escape the turmoils of inner-city schools by fleeing to the suburbs. But now we see families without children continuing to flee from the center of town. Center-city continuing care retirement communities have certainly been built in the center of town, right next to libraries, museums, clubs, and department stores, but real estate salesmen know very well that it is a safer bet to locate one of them in cheap farmland, well beyond the ring of much-praised suburban school systems. When random inhabitants of such villages are asked what attracted them, most of them say it was the medical system, but that can't be precisely right since they all have Medicare. More likely, they want to locate near the suburban doctors, hospitals and pharmacies they grew accustomed to during their compulsory residence near the high school. And the circle of friends they made there; although the aging process makes that into a dwindling band. The point here is that automobile commuting and much-praised high schools probably created suburbs, but are no longer the strongly attractive issues which induce empty-nesters to settle nearby for the rest of their lives. The CCRC is like a ship at sea, pretty much entirely self-contained because of the progressive locomotion difficulties of the residents. At first, the residents can feel free to go on living as they "always had", but habit and convenience rather quickly narrow their horizons and circle of friends. They may have been community leaders a year or two earlier, but soon after making their monastic choice, they begin to withdraw into the more limited community of their new chosen monastery. Limiting perhaps, but not confining. That's unfortunate in one way since a theme of this book is that the young older group needs to find ways to continue productive lives. The country can't afford to have them remain unproductive, and they themselves need to have more useful things to do. An entirely recreational life simply cannot continue to get longer and longer as a sole justification for all the expensive health care we seem capable of providing for them. Therefore, one promising experiment which needs to be tried is to organize the whole suburb into a half-way house, amicably intertwined with neighboring houses full of teenagers. With people living in their own homes a few years longer than they originally planned after the kids are out of the house. The town where I live is now surrounded by miles of other suburbs, but I think of it as on the edge of farmland because that was the way I found it sixty years ago. The borough itself has seven thousand houses, probably somewhat too few to suit urban planners, but presenting no convincing argument for us to consolidate with neighboring suburbs except the nagging of those sociology professors. The town has plenty of doctors, most of whom practice somewhere else, and plenty of dentists. No hospitals, no nursing homes, no rehabilitation centers. But several drugstores, two ambulatory x-ray units, and two specimen-collecting laboratories for nearby hospitals. We have a busy volunteer ambulance corps, run out of the firehouse, and frequently seen racing and honking its siren around the town. The composition of these independent medical facilities has varied over the decades but is not greatly different from what can be found in a dozen near-by suburbs. The one thing we don't have is a CCRC, and there seems to be enough demand for one, even enough empty land to hold it. Just about every retiring family in the town has been heard to express a wish that a retirement village could be made available, so they wouldn't have to pull up their social roots in addition to all of the other disruptions of retiring. Having spent most of their adult lives envying people with larger, more luxurious houses, they are now at the point where they are sick and tired of fussing with the big house they do have. They want less number but smaller houses, especially apartments, just don't exist in the town. So they are forced to consider moving away. Especially after one of the two elderly marriage partners dies, there is the worry of living alone. Twice in my own experience, an elderly widow living alone in a big house has broken her hip bone with no one in the house to call the police. One of these ladies was lucky; she lay on the floor for two days without food or sanitary support, until the mailman came by and noticed the mail piling up. The other lady was not so lucky; she had bought a big dog which apparently ate her when she was helpless on the floor. Old folks living alone tend to think they can cope with anything. Until suddenly they can't. Very likely, the mobile cell phone has reduced the number of such tragedies, just as it has apparently reduced armed robberies almost by half. The mobile phone gets progressively more clever with the invention of 500,000 applications, or apps. We can probably expect to see visual surveillance systems and the like, very soon and very inexpensively. Handbags in the bathroom and other safety devices are regularly more ingenious; there are even companies which will outfit a whole house with such improvements and suggestions for use. It's a great pity that installing a home elevator is comparatively cheap when the house is being built, and almost prohibitively expensive after the builders go away; nobody over the age of 60 should really buy a house without an elevator, except for the fact that so few houses have them. They seem expensive until you realize that moving your home once or twice is going to cost $100,000, mostly because of universal tendency to buy the biggest house you can afford rather than the biggest one you need. But even so, my little town needs one more thing before it can be said to have coped with its retirement needs. What's missing in all this is management. Relatives who live close by will often suffice, depending on their other commitments. With a competent manager, what's needed is a part-time employment agency, to supply the nurses aides, physiotherapists, and babysitters of various skill -- and to cope with the mountain of redundant government paperwork. Regulatory paperwork can rather easily be coped with by someone who has a programmed home computer, so the right equipment and program must be located, or commissioned. Since the Obama administration was recently willing to spend $29 billion dollars to equip every doctor with a computer system, what's probably most needed is a loud angry lobbying group to get the necessary money, and to cope with the passive aggressive resistance which any competitive environment is filled with. We're talking here about reducing the number of people who need to enter a CCRC, so nursing homes and other CCRSs can be expected to express hurt feelings and discover a myriad of ways it is totally unsafe to provide a competitive alternative to their business model. Getting a sympathetic congressman will help about half the time; the other half of the time you should consider the advantages of replacing him. There are advantages to starting one of these retirement villages without walls in a rural area, with lots of experience with volunteers pitching in and helping out. The community officials are sympathetic in such areas, and costs are generally lower. In a suburban neighborhood, the environment is more sympathetic to the approach of applying for a government grant, or if there is no available program, asking for the creation of a demonstration program. That's an egg that will generally take five years to hatch, and prove to have higher costs. The rural environment needs enthusiasm, the urban one needs tenacity, and will generally find it is an advantage to have a congressman who is chairman of a committee. But everyone who wants to see a local retirement village without walls also needs a slogan, so here it is. "Anything a retirement village can do can be done at home. Only cheaper." Cost Shifting: Indigent Care Out, Outpatient Revenue, InThe CEO of Safeway Stores recently offered his company's preventive approaches as an example of what the nation can do to reduce health costs. He's undoubtedly sincere, but quite wrong; Safeway just shifted costs to Medicare. This is only one of several ways, major ways, cost-shifting is misleading us. Let's explain. Average life expectancy is increasing at more than two years per decade, but of course, people eventually die. Since health care costs are heaviest in the last year or two of life, extending life will soon push nearly all those heavy terminal costs from employer-based insurance -- into Medicare. To die at age 64 costs Blue Cross a lot; but to die at 65 gets Medicare to pay for it. Either way, the cost is exactly the same, it doesn't save Society as a whole any money at all. Let's put it another way: dying at age 64 costs the employer and the employees, but dying at 65 costs the taxpayers. This means Medicare costs will surely rise, but in this case, it's a reason to rejoice. Increasing longevity is constantly pushing more costs from employers to Medicare, and not just in Safeway; the prospect is that soon substantially all major sickness costs will shift into Medicare. (To explain the failure of most employer insurance premiums to fall comparably in response to this shift, one must look elsewhere). But just a minute. Medicare is 50% subsidized by the government, and the employer writes off half of the cost as a business expense. That ought to mean it doesn't make much difference to anyone involved, except for one thing. Some employers have two employees and some have two hundred thousand employees. The amount of tax write-off is multiplied by the number of employees, so some employers can only write off a little, while an occasional employer might even make a profit on using health insurance for calisthenics. Economists agree that fringe benefits eventually and proportionately come out of the pay packet, so ultimately the employed patient benefits from the reduced bill, his employer pays less, and the Medicare costs the taxpayers more. <But instead of going down that trail, let's look at the second form of cost-shifting. Government payers and a few other monopolists are able to pay hospitals less than actual costs and get away with it. The worst offenders are state governors administering Medicaid, where the underpayment is roughly 30%, in spite of federal reimbursement to the states for most of it, at full price. The resulting profit is used for various state purposes, mainly nursing home reimbursement. For the most part, such diverted funds are used for purposes not easily eliminated, so it is unlikely there will be much cost reduction for the government if the scam is acknowledged and merely shifted to a different line in the ledger. To avoid bankruptcy, hospitals raise the rates for other health insurance plans -- and the uninsured. Employers are paying for most of it, so they stand to gain from reform, only to face higher state taxes as matters readjust. We have yet to learn where these costs will shift if the federal government takes over the costs of the uninsured; the current Obamacare plan is to shift 15 million uninsured persons to Medicaid. To a major degree, the federal government and its taxpayers are already paying for a lot of this uninsured cost, through the Medicaid shift. So its present dilemma is whether to continue to pay for it twice. There's still a third cost-shift. In 1983, Medicare stopped reimbursing hospitals fee-for-service (itemized inpatient bills are still prepared but are meaningless fictions) and for thirty years has paid by the diagnosis, not the service, for inpatients. Consequently, per beneficiary inpatient costs have only risen 18% in five years, while outpatient costs have risen 47%. Costs are not the same as prices, which are even worse distorted. To a large extent, changes in costs are really changes in accounting practices, driving changes in actual practices. Skilled nursing and home care costs are rising even faster. When you hear fee-for-service payments attacked, it is this apparent overpayment of outpatient costs which is the source of the complaint. But to pay out-patient medical costs in any way other than fee-for-service would imply an almost unimaginable restructuring of the medical system, without any proof it would save money. It will be very interesting to learn what contorted proposal is about to emerge.

Not only do these shifts provoke inpatient nursing shortages, but they also start a war for patients between hospitals and office-based physicians. Hospitals are winning this war for business, but are losing money doing so. If the public ever demands a stop to loss-leaders, net insurance premiums will probably rise. The difference between a hospital which makes money and one which loses money is based on whether there is enough extra out-patient revenue to compensate for the hidden tax which the state effectively imposes on hospitals in order to pay for nursing homes. The obscurity of the present payment system is quite expensive, and the present beneficiaries of it are the Medicaid nursing homes. Obamacare essentially provides health insurance to 15 million uninsureds by the process of placing them on Medicaid, so the consequences are going to be an interesting juggling act to watch.

Just notice, for example, that neither Medicare nor private health insurance pays below costs if you look at total national balances. Private insurers are paying hospitals 32% more than actual inpatient costs, while Medicare is paying 6% more than national cost. And yet 58% of hospitals are losing money. The magic in this formula lies in the losses incurred by state Medicaid but shifted to other payers. It could fairly be said we are just looking at a maldistribution of the uninsured, as a cost, and a maldistribution of non-inpatient revenues, as a profit, among the nation's hospitals. To what extent such maldistribution reflects uneven patient quality, as the loser hospitals claim, or provider inefficiency, as the winner hospitals would say, -- merely starts a distraction of attention which could last twenty years while we examine it. And disruptions enough to take decades to fix. Whither Alzheimer?

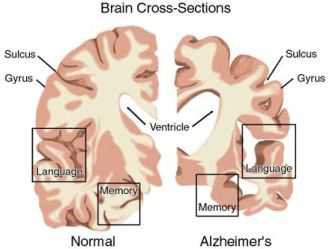

The Right Angle Club was recently treated to a sophisticated movie and a polished presentation by Dr. John Q. Trojanowski, Professor of Geriatric Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Among other posts, he holds the Truman G. Schnabel, Jr. Chair, which particularly endears him to me since Nipper Schnabel was an old friend. Dr. Trojanowski has kindly given permission to use his slides on Alzheimer's Disease.

When Dr. Alzheimer published his description of the disease which bears his name, in 1906, it was treated as a rather esoteric or even insignificant accomplishment. The average life expectancy at that time was age 47, so although some people did live to an advanced age, most people didn't. A newly-identified disease which crippled and shortened the lives of old folks was pretty well brushed aside. Doctors were too busy treating tuberculosis, rheumatic fever, syphilis and typhoid fever -- diseases which were part of ordinary practice. As things turn out, however, life expectancy nearly doubled in the ensuing century, so both the number of old folks has vastly increased, and they are dying even later, disproportionately increasing the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease, to the point where it is now the sixth most common cause of death. At present, nearly half of people who achieve the age of 65 will eventually develop Alzheimer's, and most of them will die of it. It's a protracted fatal disease, requiring a great deal of expensive care. One rough rule of thumb is that when patients reach the point of being unable to recognize the spouse or nearest relative, they will probably still live another two years. With conventional nursing care, utilizing home nursing aides, it will likely cost more than $50,000 to take care of any patient during a perfectly dreadful terminal experience. One of the more imaginative ideas for relieving this financial burden has been to store up credits for volunteer work as nursing assistants after retirement, but before infirmity, say between 65 and 85. Those credits could then be used later to pay for the care of that same volunteer when he or she becomes incapacitated. The tax authorities have been unsympathetic, however, fearing any system of barter undermines the income tax mechanism. Since there presently is a huge pool of unused labor in the early years after retirement, this idea should be revived, and at least given a trial as a pilot experiment. Experience with trying to treat this growing epidemic brings out features which somewhat seem to support the idea of "intellectual reserves". Educated and intellectually active people tend to develop the condition less frequently, or at least later in life; aboriginal cultures develop the condition much younger than advanced ones, head injuries and sports which promote them provably increase the prevalence. It looks as though persons with greater educational attainments have some kind of reserve capacity to be used up before the disease finally overtakes them. And strange things happen; the incidence on the island of Guam is now only a tiny fraction of what it was a century ago. Unfortunately, all of these anecdotal experiences contain the chance that it is actually the early onset of the disease which lessens social skills, rather than the other way around. Unfortunately, exercise does not seem to improve cognitive functioning, although it improves other functions.

Naturally, there is a great hope for scientific improvement in the treatment of this condition. After all, the percentage of persons over the age of 80 who are disabled from any condition is only half of what it was in 1982. However, the most discouraging feature of Alzheimer's dementia is that it is a degenerative disease. The estimate is made that when the first symptom of Parkinsonism appears, roughly 40% of the substantia nigra has already been destroyed. That sort of observation leads to the very discouraging possibility that a new treatment for the condition, even one that is completely effective, may never do any patient's symptoms any good. At least, research workers in the field may have to give up the approach of treating patients to see if they get better because the damage has already been done. Very likely, vast numbers of apparently normal persons may have to be treated for years, in order to see whether the disease is eventually delayed in its onset. That's quite different from defining the value of a drug for pneumonia, where all you have to do is treat a hundred patients to see if it works. Delaying the onset of this disease would be no small achievement, however, because of the average age of the patients. A delay of five years in the onset would reduce the overall quantity of impaired persons by 50%. So, an effective drug for Alzheimer's would be enormously valuable, but it would be far more expensive to determine potential delays in onset, the potential toxicity of years of preventive therapy would be greater, and the public disappointment on behalf of existing patients would be something to deal with. All of these discouragements tend to inhibit drug manufacturers from spending vast sums to develop a treatment, particularly in an era where cost concerns are prominent. But we all better get used to it: delaying the onset of degenerative diseases is likely to be more expensive, and much more difficult to prove, than the medical miracles of say infectious disease we have grown accustomed to looking for. Wheels

A young secretary who once worked for me asked to be excused early because she had to pick up her car in one of the more blighted districts of Camden. She was welcome to take the time off, but I was a little uneasy about what she was planning to do. "Oh," she said, " My husband taught me to take our old car to the Puerto Ricans. They can fix anything." As indeed they must; Puerto Rico and many other Latin American countries forbid the importation of new cars; they have to get good at fixing old clunkers. The service departments of our new-car dealers, on the other hand, have a noticeable tendency to tell you to replace something rather than repair it. Caveat emptor certainly comes into play at this point, but there's a balancing feature as well; some people should repair, others should replace, exactly the same defective appliance. The viewpoint of the serviceman is colored as much by knowing how the majority of his customers respond, as by knowing the profit margins which measure his own self-interest.

The issue came up for re-examination recently, when I felt peer pressure to buy an environmentally friendly car. My car is big and heavy, accelerates with authority, is over ten years old. It gets thirteen miles to a (now) expensive gallon of gas. Otherwise, there is nothing the matter with it to make me doubt it will last another ten years. On the other hand, the new trendy thing will get more than forty miles to a gallon, accelerate like a jack-rabbit, and bring me admiring glances from young ladies. But just a doggone minute. I currently fill the tank once a month, for thirty dollars. Am I supposed to spend forty thousand dollars for a new car, just to save fifteen dollars a month in gasoline cost? It would take me considerably longer than my present life expectancy to come out even on that transaction, while someone in Puerto Rico or Mexico continues to drive around in my traded-in used car, polluting up a storm. Whether I can afford it is not the issue. I just don't like to be urged to do stupid things. I already do enough stupid things, without having other people invent them for me. Since the matter has come up, maybe we should ask whether elderly people should own a personal car or not. Forget about telling me to take an eye exam or a repeat driver's examination administered by a state policeman; if I stop driving it will be my own decision, not that of the crooked legislature, or the ministers of Plato's Republic. But come to think of it, having my own driver could be very nice. Philadelphia's Mayor Dilworth was driven to work and around by a uniformed driver in what purported to be a Yellow Cab, but looked like a limo to me; his daughter has since confirmed my suspicions with a broad wink. So an idea does come up: there must be many semi-retired folks who own cars but would be happy to make other arrangements for minimal transportation needs. There are those little red cars spread around town for rental at $6 an hour, or even regular rental cars available for weekends and vacation. Come to think of it, there's a fellow who lives in one of Philadelphia's fancier apartment complexes who had a limo and driver of his own. People began to offer to rent his arrangement when he didn't need it, and eventually, he wound up with four limousines and drivers just for that big apartment. Anybody who could afford to live in that apartment, with or without a limousine, didn't need a new business venture. The episode, therefore, carries the discussion in a somewhat different direction.

Why didn't the owner of the apartment building install a livery service, without waiting for a retired resident to start it? A variety of answers to that question suggest themselves, chief among which would be that someone in the apartment business would buy a second apartment if he had spare capital, rather than get into a second business he knew nothing about. He would prefer two apartment buildings without limo service, rather than one apartment with a lot of unrelated businesses attached, some of which would probably lose money. We could stop this discussion along the way and reflect on union hostility, uncomprehending tax and license interference, unwillingness to set aside sufficient garage space, and many other man-made obstructions to the idea. But let's jump over all that to suppose what is needed is a multi-apartment corporation which supplies jitney bus service, charter bus service, car-shares, rental car service and livery to a large number of apartments and hotels -- and doesn't own any apartments. Why don't I start such a company myself? Because I'm retired, that's why. The logical place to begin such a venture in a retirement village or big condominium complex is with the concierge. The concierge is in a position to judge demand and build up a string of vendors, eventually forming a company with the successful vendors after the local market has been well explored. Let the business plan emerge from the market exploration. There's a general observation which applies to all cooperative apartment boards, condominium committees, club memberships, and the like. All such organizations, without fail, divide into two groups: One group describes the present arrangement as a "dump" and demands that everyone pitch in and spend some money fixing up the place. The other group has already stretched its discretionary funds to the limit and beyond, just achieving entry into the place. The latter will resist bitterly any improvements which cost money, even small amounts. Furthermore, they will organize to outnumber and squelch potential members of the other group, because the threat and its underlying motivation, remains permanent. Such political difficulties are best addressed by collecting dues for an improvement fund, which reassures everyone about the limits of what might someday be demanded. All of that talk about licenses and unions and unneeded expense always boils down to the condominium disease, so progress depends on a realistic appraisal of the chances. First, get a concierge. Phillycarshare

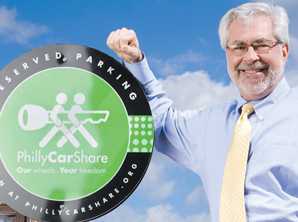

Jerry Furgione recently intrigued the Right Angle Club with what those small red cars are all about. A non-profit organization named PhillyCarShare has been able to grow a fleet of 400 autos to rent by the hour -- gas, insurance and washing included. Each car has a home base in some parking lot or garage or other accessible place, from which you take it, and back to which it goes when you are done with it. Reservations are handled by phone or internet, payment by credit card; a platoon of attendants come around at night to refill the gas and check on things.

Now that's not quite as convenient as having the car delivered, or picking it up at one place and dropping it off at another, but it's workable. One of the technical secrets is a wireless system working a lock which can be controlled remotely. For a $25 onetime membership fee the customer gets identified with a particular lock, and the car keys are inside the car. That's a little kludgey (as trendy people say) because if you forget to lock the car when it's parked it can be stolen. No doubt technology could soon be developed to handle the whole business electronically, emitting signals that the car is parked but unlocked, issuing automated scolding and just-this-once remote locking and unlocking, and perhaps a dozen other engineering features. But that requires more volume than 400 cars, and it's early days. Present reliance is made on repeated reminders to lock the car when you aren't using it, backed up with a $100 fine if you forget. It's probably the biggest source of friction. The rise in oil prices helped the car share business a lot, and enthusiasm among young early-adopters carries things quite a way, so the business is growing. It probably won't be possible to judge the future until competition appears and business levels off, at some stable point. If some of the rough spots can be fixed with gadgetry, this hourly rental system should have a permanent place in our environment. Since it's a non-profit, it will be of interest to see what variants the for-profit sector can provide.

At the moment, the business has the nuisance of an average 6-months delay to get each new parking spot approved by the various ownership and licensing agencies. But the developers of high-rise apartments are learning that having rental cars headquartered at the building entitles the builder to provide fewer off-street parking spaces, so revenue potential starts to appear. Companies, and in particular the City of Philadelphia have taken to using this system to reduce the size of their car fleets; universities are nibbling at the idea of shared memberships. Hard to know where this will lead. You learn some things the hard way. The cars once had a plastic card to use for filling up at a gas station, but too many cars were broken into to steal the cards, so this had to be curtailed. If you have an accident the company's insurance takes care of you, but then there are quarrels about renewals of insurance, both theirs and yours. People who are used to jumping into their own cars, and out of them whenever and where ever they please, tend to feel a little constrained by the need to make reservations and be prompt about them (because someone else might be waiting for the car). Which brings you to the ultimate trade-off in this system. People want to have lots of cars sitting around, so they can use spur-of-the-moment planning. The business, on the other hand, wants every car to be in constant motion, every slot in the schedule filled up. Right now the cars average eight users a day and have comparatively little waiting for reservations, only because the typical user at present does not want the car during 9-5, five days a week hours. As business increases, it should emerge just what the break-even points are between too many cars and too few. From the customers' point of view, that means, "How much are you willing to pay to have a car immediately and invariably available?" At the equilibrium point between maximum customer convenience and minimum price, we'll soon see what the public really wants and will pay for. Meanwhile, the experimentation goes on to explore the tastes and preference of the Philadelphia public, region by region. They have a few pickup trucks if you like, and even a few Lexus's. Although the original idea was developed in Europe, Philadelphia has here the largest hourly rental business in the world, and it's galloping along briskly. Books

Bookishness is not universal, but reading for pleasure is possible for many people whose physical condition limits more athletic activities. Even for those with visual impairment, books are available on tape for auditory reading. Some people seem to have been born with a disinclination to read, possibly because of dyslexia or some other limitation, but in general, you read more as you get older. Most people who enter a retirement community will arrive with a personal library, and eventually, be dismayed when the communal library tells them it doesn't want their books.

This seems like an unnecessary waste. Professional librarians, placed in charge of much larger libraries, have long ago met together and decided what to do. Here's what you do. The first step is to appoint a committee to decide on what the core subject material should be. After a number of aimless meetings, the group will ultimately decide that our library should focus on books about, say, airplanes. For gender balance, a second focus on French cooking would do quite nicely. Second, a committee is appointed to inventory the existing library, setting aside the more popular books, and identifying what is already present in the core topics, airplanes and French cooking.

Third step: as new entrants to the community lug in their boxes of books, the books which are outside the core focus are offered to an Internet used book exchange and sold for whatever they will bring. With the money realized from these sales, more books have purchased that fit into the core categories. It will take very little time before your library has a notable collection of books about airplanes and French cooking. People are invited to give lectures and book reviews about these topics, perhaps writing up some articles for the community newsletter. Once in a while, a really noted speaker from outside is invited to a special meeting of the community to listen to an authoritative presentation, and receive the coveted award for noted authorities on airplanes/French cooking. With suitable entries on websites, the local library becomes famous for its collection, and scholars begin to arrive at work on specialized projects and theses.

The idea can be embroidered as desired; you can organize a university if you want to. Field trips and exchanges with similar library clubs are more modest ambitions. To some extent, this idea grows out of an essay called What is a University? which Nicholas Murray Butler wrote and used for a commencement address innumerable times. Columbia Univerity's commencements are still mostly held in front of the steps to Low Library, and may or may not still end with Butler's punch line: A university is a collection of books. There is no reason why a retirement library should not continue to offer the local and national newspapers, or that huge favorite, the detective murder mystery. Books donated by incoming residents will almost certainly reflect the tastes and interest of the community. But if there is any care taken in the selection of the core collections, the community will develop some amateur scholars in the topics, who will be found working away in the library on some article they are writing. The library becomes a natural focus for the community computer center, or computer training center, or headquarters of the users' group. On days when it is raining, some of the golfers may wander in, as well. Gardening

The late Charles Burpee had a little speech he made everywhere he got a chance. "If you want to be happy for a day," he said, "Get drunk." If you want to be happy for a month, get married. But if you want to be happy for a lifetime -- get a garden." A lot of people who were born and bred in condos think Burpee must have been a little strange, but even they often tend house plants and window boxes.