Related Topics

...Ratification, Bill of Rights and Other Amendments

The 1787 Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights. Few except Madison himself were opposed to adding one, but many other delegates would have failed election without promising it. Negotiations at the Convention had proved so excitingly innovative that time ran out before the Convention had to adjourn with only a promise of a Bill of Rights, first thing.

Philadelphia Politics

Originally, politics had to do with the Proprietors, then the immigrants, then the King of England, then the establishment of the nation. Philadelphia first perfected the big-city political machine, which centers on bulk payments from utilities to the boss politician rather than small graft payments to individual office holders. More efficient that way.

Federalism Slowly Conquers the States

Thirteen sovereign colonies voluntarily combined their power for the common good. But for two hundred years, the new federal government kept taking more power for itself.

...Pending and Later Amendments

New topic 2012-08-01 19:06:55 description

Right Angle Club: 2013

Reflections about the 91st year of the Club's existence. Delivered for the annual President's dinner at The Philadelphia Club, January 17, 2014.

George Ross Fisher, scribe.

Sources of Revolutionary Populism

|

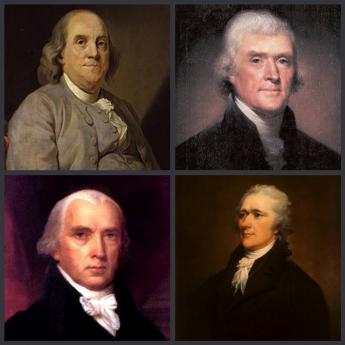

| Founding Fathers |

Those who now look back at the Founding Fathers often fail to account for the aging process during the eleven years between the Declaration of Independence in 1776 to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The two events took place in the same building, Independence Hall, and many participants of the Convention were fellow Revolutionary War veterans. But there was originally a great social difference between a colonial leader and a teen-aged soldier at the beginning of this period, which tended to seem blurred by the experiences of the war. Someone who fought and was wounded as a common soldier might later grow into the dignity of a former war hero, but underneath this veneer was a very different experience from an early leader of the colonial rebellion, or after the onset of serious hostilities, an older man who seemed eligible to be a Revolutionary officer. The original generation of rebels conspired to restore proper British rights for individual colonies, while the teenager who fought in the Continental Army under his idol George Washington saw himself as fighting for the freedoms of individuals, living in a new nation.

What emerged were two generations of Founding Fathers, one of which was generally an officer fighting for the right of his state to be fairly represented, the other a young common soldier, fighting for the individual right of free speech. One wanted to protect his colonial region's religion, the other wanted the freedom to choose his own religion. Both of them felt entitled to say how things were to be run, but young men eventually become older men. No better example of aging's transformation of attitudes could be found than the life of John Marshall. This teenaged wounded veteran of the Battle of Trenton evolved into Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the author of a multi-volume biography of George Washington, and almost the last man standing who could be called a Federalist. Other teenaged soldiers took different paths in life.

History belongs to the victor, so it is also important to recollect that almost a third of the colonists had been Tories. In general, the upper crust of society tended to be more loyalist. Thousands of Loyalists fled to Canada, and thousands more fought on the British side. When General Clinton abandoned the occupation of Philadelphia, three thousand Loyalists accompanied him. The loss of these more educated and wealthier citizens and the lowered public profiles of those who remained in America skimmed off a considerable portion of the natural leadership of the colonies. Those young men who were left behind were victors, often exhilarated to discover that if they did not lead, no one would lead.

The embodiment of these population shifts was to be found in state governments with unicameral legislatures, popular election of judges, and weak executives -- all of which have since been repudiated by experience, but all of which reflect a distrust of leaders. Partly this might be attributed to lack of experience, greater reliance on collective government by the herd instinct, the recklessness of youth, and fear that power will eventually return to the hands of those who are educated to handle it. The hostility of the lower classes to those who are better off has many causes, but in this situation, it was promoted by unexpected elevation to leadership, combined with a subsequent determination not to lose power again -- balanced against the rather strong possibility that they would. Add to this the continued influx of immigrants fleeing from foreign oppression, and it is not surprising that the result is an enduring strain of populism stirring up a latent tendency to class warfare. You, too, can be President; but you must fight if you expect to succeed. The former aristocratic attitude was that you are born to rule, as long as you don't do something stupid.

REFERENCES

| The Great Courses: History of the United States, 2nd Edition Course #8500: Lecture 14 Creating the Constitution: Aurthor: Allen C. Guelzo: ISBN: 156585763-1 | The Great Courses |

Originally published: Monday, February 04, 2013; most-recently modified: Wednesday, June 05, 2019