7 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

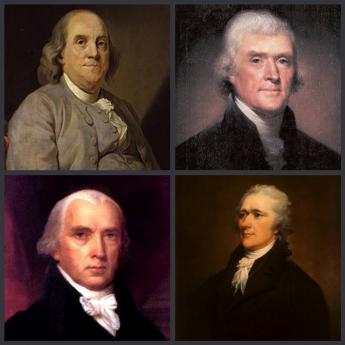

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Worldwide Common Currency and Corporate Headquarters

The Death of Money

Federalism Slowly Conquers the States

Thirteen sovereign colonies voluntarily combined their power for the common good. But for two hundred years, the new federal government kept taking more power for itself.

IF ALL MEN WERE ANGELS, NO CONSTITUTION WOULD BE NECESSARY

|

| James Madison |

JAMES Madison, Washington's floor manager at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, stated the main necessity for holding the Convention at all arose from selfish and untrustworthy human nature. The assembly probably understood exactly who he had in mind, although that is a little unfair to residents of Virginia. He really meant everybody. In the theology of the time, mankind was stained with original sin. Particularly in France, many 18th century romanticists responded to the Enlightenment by defiantly declaring human nature is born pure in heart. In their view, current evils grow from the pollution of civilization, without which it might be possible to have no government at all. At its root, such romanticism was an outcry against progress and civilization, blaming the world's troubles on the Industrial Revolution, so to speak. From Madison's skeptical viewpoint, the most awkward feature of the Romantic Period was its adoption by his Francophile friend and neighbor, Thomas Jefferson, the current American ambassador to France. Madison recognized that Jefferson and Patrick Henry were prepared to assail any attempt to add the slightest power to a central government, particularly if it weakened the power of Virginia. As indeed they promptly came forward to do and nearly succeeded.

|

| Treaty of Paris |

After fighting an eight-year war for freedom, American belief was wide-spread that it was time to draw back from such anarchy. But there was widespread suspicion in every other direction, too. England seemed to concede, not defeat but only current military overstretch, possibly displaying reluctance to see its former colonies with full sovereignty. George III might wait for America to weaken itself and then try to take them back. Britain almost couldn't do anything right; it was also possibly up to no good when the Treaty of Paris astonishingly conceded land to the Mississippi instead of stopping at the Appalachians. Even our ally France nursed regrets for its somewhat older concessions after the French and Indian War. If even the two mightiest nations of Europe could not maintain order in the vast North American wilderness, perhaps they felt the inexperienced colonies would soon collapse from the effort. Further intra-European wars seemed likely, and could soon spread from Europe to the Western hemisphere. The guillotine was bad enough, Bonaparte would be worse. Our governance as a league of states was in fact, only a league of armies. The Articles of Confederation would not quell inter-state rivalries in peacetime, as only four years (1783-87) experience after the Treaty of Paris were clearly foreshadowing. It was time we listened to Benjamin Franklin, who had been arguing since the Albany Conference of 1745 for unification of the colonies, and to Robert Morris who had been arguing for a written constitution since 1776, a bicameral legislature since 1781, government by professional departments instead of congressional committees, and the ability to levy national taxes -- since at least 1778. Professor Witherspoon of Princeton had provided some ideas about how to make these proposals self-enforcing, Washington was firmly behind a Republican system and opposed to a monarchy. On the other hand, everyone knew that under the Articles of Confederation the thirteen States had often refused to pay their share, abused their ability to deal independently with foreigners, dealt unfairly with their neighbors, and capriciously mistreated their own citizens. It was time to act boldly. With a blue-ribbon convention of national heroes behind these simple ideas, surely it would be possible to convince the sovereign state legislatures to dethrone themselves.

|

| John Marshall |

Two men quietly applied even deeper thinking than that; Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, and John Marshall of Virginia. Both of them had served in state legislatures, both were dismayed by the experience. Franklin also had a long period of close-up observation of the British Parliament, suffering personal abuse there, and had reason to reflect on the earlier abuses by that Parliament under Cromwell during the English Civil War. Certain bad tendencies seemed universal in legislative bodies. Although John Marshall was not a member of the Virginia Constitutional delegation in 1787, he was active in the politics of the group it represented back home. Both Marshall and Franklin had reason to be uneasy about misbehavior in representative bodies, whether called legislatures, congresses, or parliaments. When people said states misbehaved under the Confederation arrangement, they really meant legislatures misbehaved. Franklin did what he could within the Convention to curb this observed behavior by enumerating limited powers and endorsing power balanced against power. When he had nudged it as far as he could, he wearily agreed to give the product a try. Franklin did not trust Utopias, but he had lived among Quakers for years, observing one Utopian society which seemed to endure without resorting to tyranny.

The Constitutional provisions in Article I, Section X became the heart of what the 1787 Convention wanted to change about the relationship of the national and state governments.

States are forbidden to ...

"emit bills of credit, make anything but gold or silver a legal tender in payment of debts, pass any bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law impairing the obligation of contracts."

|

| 1787 Convention |

This brief clause is almost a presentment of what state legislatures were doing, which serious patriots regarded as wholly unacceptable. Failure of states to abide by the terms of international treaties must be included in such a summary, although the new Constitution went beyond the powers of states by locating treaties beyond the power of even Congress to change, once ratified. Some observers in fact feel that within the First Article clause, protecting the sanctity of contracts was really the nut of the matter. In one way or another, most states seemed to resort to paying their debts with inflation, somehow failing to recognize that borrowing never pays debts, it only postpones them. The great bulk of this new nation's business was to be conducted as voluntary agreements between two contracting parties. The State -- and the states -- were to stay out of the private sector, except as referee, to see that both sides kept their agreements. As a footnote, the matter of government intervention in private affairs was to rise again in the behavior of the Executive branch in the 1937 Court Packing uproar, and in the 2009 health insurance legislation. Some critics, therefore, have discomfort that the heaviest Constitutional weight was placed by the Founding Fathers on protecting private property. Are not other issues more important, they ask, like life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? The Founders, of course, we're here not ranking benevolences by value; they were stating principal urgencies for convening the meeting. In a strange unintended way, they here stumbled on the right to property as the foundation for all other rights. But John Marshall understood it was true and was to spend thirty years hammering it into place. People broke individual promises by defaulting on debts; they simply did the same as governments, using inflation.

Articles of Confederation: Flaws

DURING the twenty-five years (1776-1801) government was in Philadelphia, Americans who had rebelled against tight royal rule uncovered many defects in its opposite -- a loose association of states. Loose associations only preserve fairness by operating with unanimous consent, which is, of course, unfair to a thwarted majority, unless a dissenting minority thwarts itself as a gesture of kindness. The Founding Fathers ultimately devised a formula of weakening power by dividing it into layers -- national, state, county, municipal -- and seeking to confine minority dissent to the weakest political unit. Persuasion and peer pressure were given time to work up the ladder of appeal to a wider, more powerful body of citizens. Bottom upward by choice; top-down only in desperation. Furthermore, persuasion first, force as last resort. An implicit third safety valve emerged: if a good idea is smothered by a local concentration of bigotry, appealing to a wider population includes being heard by more viewpoints. No one claims to have authored this whole prescription or foreseen its hidden benefits; it apparently evolved by trial and error. There was another latent discovery for America's sparse population in a hostile wilderness: maintaining harmony was more essential than efficiency. It would be hard to consolidate more Quakerly concepts of governance in one document. Not exactly assembled, it emerged and was admired. The local Quaker merchants were living proof that harmony made riches for anyone, while force only works against weaker people. George Washington the cavalier general came to Philadelphia and gave it a softly Virginian twist, over and over: Honesty is the best policy. It seems to have originated in one of Aesop's Fables.

It is not necessary that the [Constitution] should be perfect; it is sufficient that [the Articles of Confederation are] more imperfect.

|

| James Madison |

Recently examined documentation reveals James Madison, the main theoretician of the closed-door Constitutional Convention, to have been severely contemptuous of state legislatures at this time in his life, and rather severely defeated by John Dickinson in a political quarrel in mid-convention about the powers of small states. From this fragile evidence emerges the idea that in balancing the powers of state and national governments in the "federal" system, it may have been someone else's idea that the greater freedom to move out of an offending state into a more favorable one, would appreciably restrain state legislative abuses. Even with this feature built into the system with the national government to enforce it, Madison is said to have been in a state of depression that the Convention refused to agree to his idea of giving Congress veto power over state laws. It took some time for improved transportation to strengthen this competition between states, but it may not be an accident that Delaware now leads the way in responding to the implicit opportunity.

Philosophy and history are different. The Framers gradually acknowledged a patched charter of tribal allegiance was insufficient and thus adjusted to the idea of a central government. They tweaked a decentralized model of governance to get the states out of the road, without antagonizing them so much they would not ratify it. Although it is commonplace to say the Articles of Confederation were a weak failure, the Articles did reflect American attitudes at the beginning of our formative period. The Constitution would not have been acceptable if the Articles of Confederation had not first been given a trial. By the end of the 1787 Philadelphia negotiation, the nature of the final proposal was to define a few absolutely minimum powers for a national government, identify a few other powers as destructive when in the hands of any other level of government, and leave a vast undefined area: where new and novel problems would be tried out in the states, then passed to a national level if necessary. Anticipating constant mid-course corrections was an important objective for even a minimalist Constitution, not the least of those challenges was to create ways to keep it minimalist. Simplicity itself keeps it hard to change. Starting at the bottom of the layers of government continues to this day to introduce new and unexpected problems to the "laboratory of the states" or even lower, working upward only as proven necessary, or spread nationally only after the solution is highly successful. It is a legacy of slavery, the Civil War, and direct election of Senators (Amendment XVII) that many Americans still fail to welcome the merits of this approach, or lack the patience to try it for their pet ideas. Considering the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution as two documents with continuous goals, we got it right, the second time.

And we got it right in the environment of Eighteenth-century Quaker Philadelphia, where a tolerant examination of new ideas was more venerated than in any other place in the civilized world. With a combination of wisdom and impasse, minor issues were left to the future. It is true this sometimes creates problems of neglect. But it makes it possible to define those few issues which must never change. An unexpected virtue of minimalism surfaced eighty years later: many men understood it well enough to die for it.

|

|

Edwin Corwin's "John Marshall and the Constitution" |

Much has been written about the separation and balance of powers between the three branches of the federal government. However, the real balance of power in the Constitution in 1787 was vertical, between the central government and the constituent states. Balancing power horizontally, within the central government's branches, is a way of preventing one side of this other argument from tilting the state/federal balance in its own favor, or slowing down the effect of any victories by one side. In other words, it preserved citizen liberty to choose. From this continuing two-dimensional struggle emerges the explanation for filibusters, the seniority system, the confirmation process for Supreme Court and Cabinet appointments. It also calls into question the Seventeenth Amendment, where the state legislatures lost the power to appoint U.S. Senators. In 1786 the states had all the power, in 2009 state power is much diminished; but it is not entirely gone by any means. It is true the cry for states rights, essentially an appeal to the Deity for Justice is futile. If states are to wrest power back from the federal government, it will be by the adroit exercise of powers buried within the balanced powers of the federal branches, but it can succeed if the public ever wants it to succeed. The Framers seem to have overlooked the possibility that federal power could someday outgrow its blood supply, simply growing too big to manage. It is also true the Framers neglected the possibility of a protracted period of disagreement between two halves of the electorate. At least in these particulars, there is room for the further evolution of the Constitutional principle.

While features of the present Constitution can sometimes be linked to the correction of flaws in the Articles, one by one amendment never seemed to be quite enough. Subsequent analysis of Original Intent has often had to contend with the unspoken intent of earlier negotiators to strengthen partisan advantage in later struggles. The political battles being fought at the beginning, which except for slavery are substantially the same today, were sometimes being promoted for reasons which now seem merely quaint. Fine, everyone can agree it was complex. Still, there was a recurring uneasiness: what was the underlying flaw in the Articles? What, as they say, is the take-home point?

One widely accepted summary, probably a correct one, of what was centrally wrong with the Articles of Confederation, lies in a concise observation, which follows, from Edward S. Corwin's book John Marshall and the Constitution:

"The vital defect of the system of government provided by the soon obsolete Articles of Confederation lay in the fact that it operated not upon the individual citizens of the United States but upon the States in their corporate capacities. As a consequence, the prescribed duties of any law passed by Congress in pursuance of powers derived from the Articles of Confederation could not be enforced."

And that's how many Revolutionary Americans, possibly most of them, had wanted to have it. They were in revolt against all strong government, not just the King of England. They surely would have applauded Lord Acton's declaration that "All power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Thirteen years of near-anarchy taught them they must at least give some limited powers to a central government, but it was to be no more than absolutely necessary. For some, the Ulster Scots, in particular, even the absolutely minimum amount was still just a bit too much. In effect, these objectors wanted a democracy, not a republic.

To deconstruct Professor Corwin's analysis somewhat, the equality-driven followers of Thomas Jefferson believed the insurmountable obstacle for uniting sovereign states is that they are sovereign, and won't give it up. The merit-driven followers of Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, and George Washington bitterly resisted; in business and in war you need the best leaders to rise to power. The function of common men is to select the best among themselves to be leaders. Only James Madison seems to have grasped that ideal government might tend more toward a republic for purposes of the enumerated federal powers plus enumerated powers specifically denied to the states. For lesser issues, perhaps a purer democracy would be just as workable. However, in operation, it took scarcely a year to discover that the common man would not automatically select the best man he knew to be his representative. In fact, there exists a considerable populist sentiment, that wealth and success outside government are actually disqualifications for office. To some extent, this reverse social Darwinism is grounded in an unwillingness of the upper class to serve in government, perhaps because service to the country interferes with the lifestyle of unrestrained power and wealth which other occupations allow, but is forbidden to public servants. In any event, we persist in the fruitless argument whether America is a democracy or a republic; it was designed to be a mixture of both. Within the time of the first presidency, the unattractive realities of mixing human nature with elective politics transformed the meanings of the Constitutional document to something that was never written there, and other nations have largely failed to grasp. It apparently also worked a major transformation in its main author. James Madison first quarreled with his ally, Alexander Hamilton, and joined forces with the Constitution-doubter Thomas Jefferson. His mentor and idol, George Washington, essentially never spoke to him again.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

States rights no longer confronts America directly, because the Founding Fathers managed to get around it until the Civil War, and then the Fourteenth Amendment enabled the federal judiciary to attenuate state sovereignty somewhat further without eliminating the architecture of a federation of states. In other words, in two main steps we deprived the states of some sovereignty, but no more than absolutely necessary, and we took more than a century to do it. The European Union currently faces the same obstacle; this is how we solved it. If they can get the same result in some other peaceful way, good luck to them. Our framers used the language "Congress may...or Congress may not..." They only dared to strip state legislature of a few powers because they needed the legislatures to ratify the Constitution, a gun you can only fire once. Thus, they forbade states the right to issue paper money, the power to interfere in private contracts, and such, as enumerated in Article I, Section X, where the operative phrase is "The states are forbidden to..". The framers were willing to strip the unformed Congress of many more specific powers than the all-too-existing states; the Constitution can be read as a proclamation of the powers which any central government simply must possess. There might be other desirable powers, but here is the minimum. After eighty years, individual Southern states asserted their unlimited powers extended to nullification and secession, and because of a perceived need to preserve slavery would not back down. The Constitutional consequence of this national tragedy was the Due Process section of the Fourteenth Amendment, which has since been purported by the Supreme Court to mean that whatever the federal government may not do, the states may not do, either. However, Due Process traces back to the Magna Carta and has been so tormented by an interpretation that for the purpose stated, it is growing somewhat too elusive to remain useful. For historical reasons, we never gave a fair trial to the original proposal to address the federal/state dilemma. The Constitutional Convention was held in confidence, many delegates changed their minds along the way, and many ideas were more perceived than enunciated. It is plausible that the original strategy originated with Madison's teachers and emerged from many discussions, but there were several delegates in attendance with the sophistication to originate it. In a convention of egotists, there were even a few who would put their ideas in someone else's mouth.

The concept of how to curtail power in a non-violent way, can be called Regulatory Competition. Mitt Romney seemingly plans to promote the idea as a central feature of his political run for President of the United States, using a variant he has developed with Glenn Hubbard, the Dean of the Columbia University School of Business. The idea does still work reasonably well with state taxes and corporate regulation. If a state raises a tax, estate tax for example, in a burdensome way, people will flee to a state with more reasonable taxation. Corporations have learned how to shift legal headquarters to Delaware and other states which court them, and in really desperate cases will move factories or whole businesses. There is little doubt this discipline is effective, and little doubt that some cities and states have been punished severely for encouraging an anti-business environment. Whether the Fourteenth Amendment could be cleverly amended to expand this competitive effect without reintroducing segregation or the like, has not been seriously considered, but perhaps it should be. There are however not too many alternatives to consider.

As far as advising our European friends is concerned, it would be important to point out that the original version of Regulatory Competition completely depends for its effectiveness on the freedom to flee to some other state within the union. A common language is a big help to unity, but the ability to move residence is essential, so for practical purposes, both a common language and freedom of migration are required. Underlying such concessions is a sense of tolerance of cultural differences. That is unfortunately where most such proposed unions have either resorted to violence or failed to unite. And of course, the power which might otherwise be abused must then be shifted from the federal, back to a state level. What surfaces is a sort of one-way street? It remains far easier to devolve into little statelets than to unite for the benefits of scale. A working majority under the likes of Thomas Jefferson might have been assembled in the Nineteenth century but was held back by coping with the expanding frontier. During the Twentieth century, it would have been held back by the need to deal with world power. The Second Tea Party seems to have some inclination along these lines, but it remains to be seen whether some overwhelming need for world power will once more overcome the obvious national ambivalence about it.

The revised proposal for the regulatory competition takes the proposal to a different level, possibly a more workable one. Workers in the United States can freely move from one state to another but are restrained by national laws from equally free movement between nations. Removing that barrier makes the European Union attractive, although it inflames local nationalism. Since it seems more palatable to allow the currency to move, perhaps a little tinkering would be sufficient to permit uniform monetary rules to be the hammer which forces nations into permitting free trade on a global scale. The people themselves can remain at home in their national costumes, perhaps perfecting their religions in more churches and language skills in more schools. Meanwhile, the insight of Adam Smith would prevail for the long-term prosperity of everyone. Each party in a transaction feels enriched by it, the seller preferring to have the money, and the buyer preferring to own the goods. Multiplied a trillion-fold, these improvements in everyone's condition result in the steady enrichment of all.

Tenth Amendment: Nothing Up Our Sleeve

The Tenth and Eleventh Amendments are the high-water mark of state power in the American Republic. The main 1787 Constitution lists what the Federal organization might do and might not do, but it only lists a few other things the states may not do. By implication, the states could do everything else. But a great many promises had been made during the ratification campaign, some of them weakened by the atmosphere of salesmanship. The members of the First Congress convened the new government with a long list of hostile, suspicious proposals for amending what many of their constituents regarded as merely honeyed promises. In effect, the anti-federalists were demanding to "have it in writing". Under the circumstances, the most effective promise was one that was simple and short:

Amendment X The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people

|

| The Tenth Amendment |

Eleventh Amendment

There are certainly a lot of Ingersolls in Philadelphia. A lot of Jared Ingersolls, a lot of Charles Ingersolls, and even a lot of Charles Jared Ingersolls. At a dinner party, a lady whose maiden name is Ingersoll was asked about Charles Ingersoll, and was forced to say, "Just how old would you say he is?"

|

| Jared Ingersoll, Jr., |

The one we are talking about here is Jared Ingersoll, Jr., the son of a Tory who had once been tarred and feathered by Revolutionaries in New Haven. Young Jared was in England at the Inns of Court when the Declaration was signed, became a fervent Revolutionary, and represented Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention. It was thus difficult to predict where his sympathies would lie in the settling of debts and grievances associated with the Revolutionary War; in fact, he might be as impartial as any lawyer to be found at the time. At their best, all lawyers reach for the peaceful settlement of grievances, serving their clients best by finding a solution that puts an end to reprisals. Furthermore, he had excellent legal training, something which could not be said of most apprentice-trained lawyers of that time, and had faithfully attended every single session of the Continental Congress, while commenting very little about his own views. The first ten amendments are the Bill of Rights which had been promised during the ratification process, so the Eleventh became the first real amendment, in the sense that it specifically reverses some feature of the original design. To present observers it may not be easy to surmise just what the purpose might have been to outlaw the method which had been established for an injured citizen to sue a state. To be blunt about this point, the colonists wanted to welch on paying debts to Loyalists and Englishmen, those hated enemies, without admitting this was their motive. The spin they put on this shabby attitude was that states were now sovereign entities without a king, and since historically a British king could not be sued without his consent, therefore neither could the states. Probably the best that can be said for this cloud of words is the point that suing the government should not be made too easy, for fear of overwhelming the court system with endless clamor. The historical episode surrounding the Eleventh Amendment is an important one in our national struggle to balance the accusations of hypocrisy and chiseling, with the opposite tendency of slavish adherence to procedure, or "due process".

|

| Alexander Chisholm |

Ingersoll had attended the Constitutional Convention as part of the most influential state delegation of insiders and was set up to practice law in the capital city of Philadelphia just a few blocks from the heart of government. A case came up. The estate of Captain Robert Farquhar, an Englishman, was owed $169,613.33 for "goods" sold in 1777 to agents of the embattled State of Georgia during the Revolution. The executor of Farquhar's estate, a resident of South Carolina named Alexander Chisholm, then sued the state of Georgia after the war was over for that state's extinguishing the debt by a statute passed after the contract. This had been the rather common treatment of Loyalist debts by other colonies and thus enlisted their sympathies to Georgia in this case. Furthermore, it was the sort of uncivil behavior that had enraged John Jay and George Washington, leading them to press for the Constitutional Convention. On the other hand, the new state governments were hard-pressed for cash and had to contend with highly combative citizens who resented even the suggestion that they play fair with people who had so recently been trying to kill them. Furthermore, it was entirely realistic for them to fear a flood of lawsuits from people they mercilessly pursued under what "everyone" considered the rebellion's accepted rules of engagement. It was thus clever for Georgia to seek the help of Ingersoll in appealing to the Supreme Court, and the previous tarring and feathering of his Loyalist father was not entirely irrelevant. Ingersoll, unfortunately, lost his case of Chisholm v Georgia when the Supreme Court (John Jay, CJ) declared that Chisholm was indeed entitled to sue the State of Georgia. It is hard to see how Ingersoll (and his colleague Alexander Dallas) could have won this case when the Constitution which he helped write plainly provided the rules for citizens of one state suing another state; it seems remotely possible that the officials of Georgia were attempting to shift the blame of an inevitable loss of the suit:

Article III - Section 2 -The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

John Jay ultimately revealed the depth of his dismay at dishonoring debts when he negotiated Jay's Treaty during the Adams administration, providing for adjustment of such debts. Adams, in turn, was to reveal where his own sympathies lay by refusing to announce -- for three years -- the reversal of this position by the Eleventh Amendment, stirred up in his own state. Adams' rather flagrant abuse of a technicality might well have led to another constitutional amendment, except for the Supreme Court later ruling that official enactment of amendments did not require Presidential announcement, but took effect upon ratification by the required number of states.

Adams, in turn, had ample political problems in his home state of Massachusetts. John Hancock, then Governor, called a special session of the Massachusetts legislature to propose an amendment to reverse the Constitutional language on which the Supreme Court's decision had relied: It soon became clear, or perhaps Ingersoll was determined to make it seem clear, that Georgia had been smart to employ this political insider. Congress soon enacted, and the necessary states soon ratified the Eleventh Amendment. It stated that a citizen of another state may not sue a State government in Federal Court:

Amendment XI. The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.

Later decisions included citizens of the same state, so in effect, this amendment stated that no one may sue a State Government unless the state agrees to be sued. That's essentially what is true of the federal government; the states were given the same sovereignty with all of its features, as the federal government and that was an intentional slap in the Federalist faces.

It sounds as though Jared Ingersoll might have been a states-righter, although nothing in his past or future behavior suggests that he was anything but an ardent Federalist. He was even proposed as vice presidential candidate for the Federalist Party. No one called him wishy-washy, or a traitor or a covert anti-federalist, and he never acted like one. He was just a lawyer with a client.

Revising, Amending, and Skirting The Constitution

|

| Tiananmen Square |

In some foreign countries, people who dislike the government about some issue wait for a clear day and go in the streets to riot. Some of our own younger people who spent a little too much time abroad have likewise occasionally called their friends on a cell phone and agreed to pour out into our town squares to protest. When you try that in Tienanmen Square (1989) or similar places, machine guns can suddenly end the meeting (2,500 dead). We had the Boston Massacre of 1770 (5 people killed) and Kent State of 1970 (4 people killed), where newsmedia somewhat over-dramatized the risk involved. In general, most Americans feel public demonstrations are neither very dangerous nor very useful.

|

| Chief Justice, John Marshall, |

One measure of Constitutional effectiveness can be found in just this public attitude. The citizenry has been told and generally believe that methods for addressing grievances have been provided in the legislative, judicial and executive branches, ultimately leading to the Constitution itself as the last point of appeal. The 1787 framers in Philadelphia probably had this design in mind, but it was not until the third Chief Justice, John Marshall, made it his life's work that the elegance of the system became widely appreciated. The Constitution is the capstone of our system; every citizen's grievance can be appealed within it. If things are sufficiently dire, even the Constitution can be changed.

|

| second Constitutional Convention |

A second Constitutional Convention could be called, but most lawyers shudder at what chaos might emerge from making multiple changes without waiting to see how a few worked out. For practical purposes, therefore, amending the Constitution is the last recourse when the government goes astray. Amendments don't easily succeed; hundreds were proposed in two hundred years but only two dozen were adopted. In totalitarian countries, millions of amendments might be envisioned, but either nothing significant would be adopted, or nothing significant would be enforced. In our country, it is sufficiently difficult to succeed that frivolous or ill-advised proposals are discarded or modified into less extreme forms by "due process". But enough amendments do succeed to keep the populace out of street protests. Amendments can succeed, if you and the proposal are really serious. So far the only real appeal beyond an amendment has been another amendment.

|

| Judge Benjamin Cardozo |

The step provided before an amendment is to appeal to the Supreme Court. That happens about a hundred times a year, with the generally satisfying outcome. Perhaps the only serious criticism of the Supreme Court is the difficulty of "gaining cert.", which is the process of petitioning the Court to take the case, by granting a writ of certiorari. Only about 2% of petitions are allowed to present their arguments, and the Court has protected itself from overwhelming volume by limiting its caseload to instances of conflicts between circuits, and cases involving sovereignty of some sort. For such a selective process to remain acceptable, implicitly the rulings of the various Circuit Courts of Appeal would also have to enjoy general approval. That such is the case is evidenced by the fame and distinction reached by certain Judges of Appeals Courts, like Benjamin Cardozo, Learned Hand, and Richard Posner. In Cardozo's case, he was finally appointed to the Supreme Court, but at such an advanced age and short tenure that his Supreme Court reputation is rather modest; he achieved his reputation as an Appellate Judge. The failure of Robert Bork and several others to achieve Senate ratification illustrates a somewhat different version of the same issue: that the higher courts, not just the Supreme Court, are generally held to do as good a job as human systems allow; supremely gifted judges are not exclusively in the Supreme Court. As you go lower in the court system, more dissatisfaction can be heard, ultimately reaching slander accompanied by knowing grins, such as "You show me a hundred thousand dollars, and I'll show you a Philadelphia judge." Whenever criminals meet justice, such mutterings can be expected. But the point to emphasize is that there are no muttered challenges to the contention that the higher you go in the Judiciary, the more distinguished the judge is likely to be.

That's the federal judiciary, of course. State judiciaries are held in less esteem, although they have the power to put people in jail forever, award multimillion-dollar verdicts and modify the climate of business. Somehow, the prestige of these judicial systems has eroded to the point where a joke can be heard that being a state supreme court justice is a pretty good way to start a law practice. It's hard to know whether prestige has disappeared because of performance, or the reverse. Whether the steady erosion of state legislative power by Congress has resulted in a parallel loss of status in the judiciary is a serious question. In that case, of course, there is very little the judiciary itself can do about it.

|

| Dred Scott |

The Congress shall have power to .........Regulate Commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian Tribes

just exactly as it did when for 150 years everyone referred to it as the Interstate Commerce Clause. What has changed is the declaration that Congress may regulate all commerce of any sort, without fear of challenge in the court system. Whatever chances Roosevelt might have had to amend the Interstate Commerce Clause before this uproar, it is clear he could never have achieved its amendment afterward.

The second instance of circumvention is related to the same episode. The insurance industry was highly displeased to find itself regulated by federal agencies, and within six weeks successfully lobbied the McCarran Ferguson Act into law. Congress could not overturn or make an exception to a Supreme Court ruling, but it accomplished the same result by prohibiting federal agencies from taking action in the business of insurance. To maintain regulation for insurance, all of the various states then passed laws establishing insurance regulatory mechanisms, and insurance regulation migrated back to the states. It is now difficult to know whether the same exception could have been created by then re-amending the Constitution. But since the advent of wide-spread current dissatisfaction with health insurance, it pretty clear that an amendment imitating McCarran Ferguson would never pass, today.

|

| John Jay the Chief Justice |

Finally, the Eleventh Amendment may not have been such a good idea, either. The dispute in 1793 (although it avoided saying so) was about compelling Americans to pay just debts regardless of the person they owed them to. And that included paying debts to former Loyalists. John Jay the Chief Justice was sent to England to negotiate a treaty to settle this matter, but after both nations ratified the treaty, state laws were passed to supersede it. From this evolved the issue of whether a treaty takes precedence over American laws, and the ensuing battle firmly established the preemption of Congress by treaties. Two hundred years later, when the British are our allies and Revolutionary debts fade in significance, many people are uneasy about such clear-cut deference to treaties. Our unwillingness to join the League of Nations, and sign the Kyoto Agreement, or enter into many other international cooperative ventures are related to uneasiness about the unintended expansive power inherent in the Constitutional location of a foreign treaty, enacted at a time of limited communication. We are doomed by demography to perpetual minority status in world forums but forced by economic success to exert leadership or become a target. There is no immediate emergency, but the prescribed generalities of enacting or enforcing treaties need sober reflection in the era of instant communication.

Unconstitutionality of Otherwise Desirable Laws

Note: James Madison, the central figure in the design and meaning of the Constitution, the only person allowed to keep a journal of the deliberations, and the main author of the Federalist Papers which explain and defend the final product, was eventually elected President of the United States. As such, he was acutely aware of the intention of the Constitution's limitation of federal powers, which particularly extended to prohibit the Federal Government from doing otherwise desirable things. On November 3, 2010, the Wall Street Journal republished part of Madison's veto message of March 17, 1817, in which he reminds the Congress and the nation that it was unconstitutional for the Congress to do prohibited things, thereby assuming unenumerated powers.

|

| President James Madison |

"The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers, or that it falls by any just interpretation within the power to make laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution those or other powers vested by the Constitution in Government of the United States."

"The power to regulate commerce among the several States" cannot include a power to construct roads and canals, and to improve the navigation of water courses in order to facilitate, promote, and secure such a commerce, without a latitude of construction departing from the ordinary import of terms strengthened by the known inconveniences which doubtless led to the grant of this remedial power to Congress."

To refer the power in question to be "to provide for the common defense and general welfare" would be contrary to the established and consistent rules of interpretation...It would have the effect of subjecting both the Constitution and laws of the several States in all cases not specifically exempted to be superseded by the law of Congress... Such a view of the Constitution, finally, would have the effect of excluding the United States from its participation in guarding the boundary between the legislative powers of the General and the State Governments..."

I am not unaware of the great importance of roads and canals and the improved navigation of water courses, and that a power in the National Legislature to provide for them might be exercised with signal advantage to the general prosperity. But seeing that such a power is not expressly given by the Constitution, and believing that it can not be deduced from any part of it without an inadmissible latitude of construction and reliance on insufficient precedents; believing also that the permanent success of the Constitution depends on a definite partition of powers between the General and the State Governments, and that no adequate landmarks would be left by the constructive extension of the power of Congress as proposed in the bill, I have no option but to withhold my signature from it.."

Postscript: This veto was the last act of Madison's term in office, and probably does not adequately describe the problem or even Madison's view of it. The Louisiana Purchase had dramatized some awkward features of strict construction of the Constitution in areas never before considered or discussed. Albert Gallatin had earlier arranged the workaround of treating the limitation as applying only to the financing of interstate transportation arrangements and was starting the process of what we now call the "Living Constitution" by progressive circumvention. While following Madison's reasoning, he made the unfortunate choice of circumvention in preference to confronting issues directly through the Amendment process. The Tea Party movement of 2010 could be evidence that this choice is regarded by many as unfortunate. The Constitution has probably not adequately appraised the tendency of legislation to achieve final passage quite near the congested end of an electoral term, leaving little time to respond to Congressional action with the intentionally cumbersome Constitutional Amendment process. If there is a turn-over of party control at that time (which is usually the holiday season), a successful outcome appears still more unlikely in the time available. Fixing such an inadvertent technical problem would not appear to be difficult, and a Blue Ribbon study committee is suggested.Seventeenth Amendment

|

| Seventeenth Amendment |

The Seventeenth Amendment of the Constitution provides for the direct election of U.S. Senators; prior to that, the states could decide for themselves how to select their Senators. The Amendment was proposed in 1912 and ratified in 1913. Today, most people have no opinion whether the Amendment was good or bad, necessary or unnecessary. The Progressives of 1912 professed to be shocked, shocked, that wheeling and dealing went on in the state legislatures every time there was a vacancy in the Senate. Indeed, few contestants on TV quiz shows would be able to tell you what the Amendment was about. It would be hard to find a person who would, without further study, be opposed to a reaffirmation of "The Senate of the United States" shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and such Senators shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures."

If you search for reasons -- why in the world would there be a fuss about this topic, 125 years after the "Constitutional Convention -- several plausible reasons are stated, all of them amounting to legislature incompetence. Such as deadlocks resulting in vacancies remaining unfilled, influence by corrupt political organizations and special interests through the purchase of legislature seats, and neglect of duties by legislators because of politics. Even though news of these matters has failed to persist in the national recollection, they seem plausible enough; it sounds like local politics, all right. But the plausibility was there in 1787, too, and surely the founding fathers expected something like that when they let the States select their Senators as they pleased. The whole idea surely was to give the states additional reassurance that they could block any further transfer of state power to the federal government; direct election of senators clearly reduced the power of state governments in the federal/state struggle. Mostly, of course, by the State Legislators selecting one of their own members to go to Washington.

|

| John Marshall |

We have here a tilting of our governance from a Republic toward a Democracy, following the philosophy of John Marshall, of all people, that the behavior of all State legislatures everywhere will inevitably lead to mischief. Just a minute, please, let's give this a little thought. Surely the vast amounts of campaign money required to run for a Senate seat compare with the amount a special interest would have to spend to buy a majority in the Legislature of a State. As a practical matter, most special interests have lost interest in State politics and spend their money in Washington -- except for those few special interests that are exclusively State regulated. This comes down to the insurance and real estate industries, with insurance only there because of the McCarran Ferguson Act. This isn't only because of the Seventeenth Amendment, it also has to do with Franklin Roosevelt's Court-packing attempt, which is discussed elsewhere.

|

| " Plato" using Leonardo da Vinci as model. |

The idea of a Republic, originally set down by the Greek philosopher Plato, was that a small group of elite philosophers (you will have to forgive his professional biases) who meet together occasionally, would be better able to pick a member of their group for higher responsibilities, than would the populace. The inner circle would know who was an alcoholic, a phony, a pervert, a coward or a loafer, whereas these qualities can be concealed from mass audiences long enough to get elected. Such an in-group in a legislature may pick a bad person, or deliberately reject a good one, but they do it on purpose, not because they are fooled. The issue of direct election of Senators comes down to whether you think it is more likely that a legislature will be corrupt, or the voting population will be ignorant. Hard choice.

Meanwhile, election to the State legislature has been reduced to an inconsequential backwater, almost guaranteed to have an adverse effect on the members. There was a time when people who wanted to be U.S. Senator knew they must first run for the Legislature, where their skills could be tested and perfected. National affairs became State affairs, with legislators well aware that they could unseat a Senator whose national behavior displeased them. There are many States, Pennsylvania among them, who collectively pay far more federal taxes than they receive in federal benefits. Call it pork barrel if you like, the present degree of interstate wealth redistribution could not possibly continue at present levels if we repealed the XVII Amendment.

Owen Roberts: A Switch in Time

|

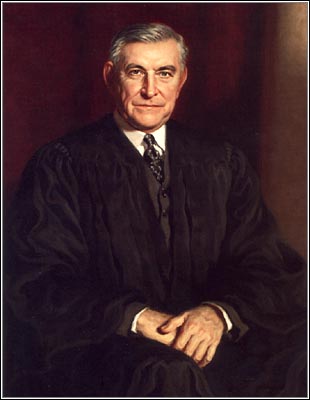

| Owen Roberts |

To this day, no one knows quite what to make of Owen J. Roberts, founder of one of Philadelphia's largest law firms. He was Prosecutor of the Teapot Dome scandal, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Republican appointee to the U.S. Supreme Court. But then, he abruptly became the source of one of the most radical revisions of our system of government since the Declaration of Independence. Nothing in his prior career and nothing afterward in his subsequent civic-minded retirement from the Court seemed to suggest any radical turn of character had taken place. He has been compared with a famous baseball pitcher who threw right-handed or left-handed at will, unexpectedly, capriciously, who knows why.

The issue went far beyond one clause in the Constitution, but the commerce clause was the focus point. Under the limited and enumerated powers allowed to Congress by the Constitution was :

The Congress shall have power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

That used to be called the interstate commerce clause until the Supreme Court announced its decision in the case of Wickard v. Filburn. When linked with the Tenth Amendment, granting to the States the power to regulate everything not specifically granted to the Federal government, this clause in the Constitution was universally taken to mean that the States had control of commerce within their borders, while Congress would control interstate commerce. Wickard v. Filburn took all that power from the states and gave it to Congress, which henceforth would regulate commerce. John Marshall had certainly triumphed over the hated state legislatures, but the Supreme Court suddenly lost its power to overrule Congress, too. One side had won the old argument, by silencing the umpire. No wonder Franklin Roosevelt started annual celebrations called Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners.

To describe the background: The 1929 stock market crash was quickly followed by the economic Depression of the 1930s. Nothing of this magnitude had been seen before, and there was a stampede to try new and untested solutions. Even government action which actually worsened economic conditions was felt justified if it conveyed to the frightened public the image that its leaders were taking firm action. Since Socialism and Communism were among the solutions grasped for, many unfortunate actions were felt justified as a way to control the Bolshevik threat. Many of these New Deal actions were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court since they involved sweeping revisions in the way all commerce, internal to the States as well as interstate, was conducted.

The Depression and financial panic continued through the 1936 Presidential election, which Roosevelt won in a landslide. Immediately after the start of the new term, he announced a plan to increase the number of Justices on the Supreme Court, appointing new ones more to his liking. He was at pains to point out that seven of the nine life incumbents had been appointed by Republican Presidents. This was, of course, the restraint intended by the Constitutional Convention, and the idea of packing the Court with new appointees was exactly what Jefferson and Jackson had tried to do.

|

| Franklin Roosevelt |

In the meantime, the case of Filburn, a dairy farmer, came up. One of the New Deal agencies had assigned him a quota of 200 bushels of wheat he could grow on the side, as part of an effort to raise wheat prices by reducing supply. Filburn had raised 400 bushels, but consumed the extra wheat for his own personal use, hardly a matter of interstate commerce. The Court had repeatedly declared laws like this to exceed the interstate commerce limitation and were thus unconstitutional for the Congress to enact.

Well, Owen Roberts changed his position, Filburn lost his case. Forever afterward, this change of position was referred to as the switch in time, that saved nine. Since that time, the Court has rarely had the courage to rule any action of Congress unconstitutional, even though it is true that Congress promptly and resoundingly rejected the court-packing proposal.

And furthermore, the power of the state legislatures has shriveled because all commerce (except insurance and real estate) is federally regulated, with a corresponding vast increase in the size of the Federal bureaucracy, as Congress relentlessly pushes to intervene in commerce among the several states, formerly known as the Interstate Commerce Clause. Franklin Roosevelt had a certain right to gloat at Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners.

A few weeks before he died, Owen Roberts had all his papers burned. Apparently, we will never know whether the present outcome was the result he had in mind. Since he was later the author of Alfred Barnes' will, which strenuously sought to prevent the transfer of the Barnes art collection to Philadelphia County, anything written by a lawyer can apparently be reversed by other lawyers. One would have supposed that either the Original Intent would govern, or else the opinion of the Supreme Court on what the Constitution means, would prevail. Franklin Roosevelt showed us there is a third possibility: the President can overrule the Court by intimidating it.

Delaware's Court of Chancery

|

| Chancery |

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's the county seat so it has a courthouse on the town square, with little roads running off in several directions. The courthouse is surprisingly large and imposing, even more, surprising when you wander through cornfields for miles before you suddenly come upon it. The county seat of most counties has a few stores and amenities, but on one occasion I hunted for a barbershop and couldn't find one in Georgetown. This little town square is just about the last place you would expect to run into Sidney Pottier and all the top executives of Walt Disney. But they were there, all right, because this was where the Delaware Court of Chancery meets; the high and mighty of Hollywood's most exalted firm were having a public squabble.

Only a few states still have a court of Chancery, but little Delaware still has a lot of features resembling the original thirteen colonies in colonial times. The state abolished the whipping post only a few decades ago, but they still have a chancellor. The Chancellor is the state's highest legal officer, and four other judges now need to share his workload, which was almost completely within his sole discretion seventy-five years ago. In fact, the Chancellor usually heard arguments in his own chambers, later writing out his decisions in longhand. The Court of Chancery does not use juries.

Going back to Roman times, the Chancellor was the highest office under the Emperor, and in England, the Lord Chancellor is still the head of the bar in a meaningful way. Sir Francis Bacon was the most distinguished British Chancellor and gave the present shape to a great deal of the present legal system. A court of Chancery is concerned with the legal concept of equity, which is a sense of fairness concerning undeniable problems which do not exactly fit any particular law. The Chancellor is the "Keeper of the King's conscience" concerning obvious wrongs that have no readily obvious remedy. You better be pretty careful who gets appointed to a position like that, with no rules to follow, no supervisor, no jury, dealing with mysterious issues that have no acknowledged solution.

|

| George Read |

Delaware's Court of Chancery evolved in steps, with several changes of the state Constitution over a span of two hundred years. As you might guess, a few powerful chancellors shaped the evolution of the job. Going way back to 1792, Delaware changed its Supreme Court from the design of its Constitution, and George Read was the new Chief Justice. However, it was all a little embarrassing for William Killen, who had been the Chief Justice, getting a little old. Read refused to have Killen dumped, and in this he was joined by John Dickinson, who had been Killen's law clerk. So Killen was made Chancellor, and a court of Chancery was invented to keep him busy.

Under a new 1831 Constitution, the formation of corporations required individual enabling acts by the Legislature and limited their existence to twenty years. However, the 1897 Constitution relaxed those requirements and permitted entities to incorporate under a general corporation law and allowed them to be perpetual. By this time, other states were distributing equity cases to the county level, but Delaware was too small to justify more than a single state-wide Court. That court was attractive to corporations because it could become specialized in corporate matters, but retained a pleasing number of equity cases among common citizens, thus retaining a folksy point of view. In unique situations or those without a significant history of public debate, it was thought especially desirable to strive for unchallenged acceptance of the court's decision.

But other states thought they could see what Delaware was up to. In 1899 the American Law Review contained the view that states were having a race to the bottom, and Delaware was "a little community of truck farmers and clam-diggers . . . determined to get her little, tiny, sweet, round baby hand into the grab-bag of sweet things before it is too late." However, that may be, corporations stampeded to incorporate in the State of Delaware, and the equity of their affairs was decided by the Chancellor of that state. In one seventeen year period of time, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Chancellor only once.

Chancery's jurisdiction was complementary to that of the courts of common law. It sought to do justice in cases for which there was no adequate remedy at common law.  |

| A. H. Manchester Modern Legal History of England and Wales, 1750-1950 (1980) |

Some legal scholar will have to tell us if it is so, but the direction and moral tone of America's largest industries has apparently been shaped by a small fraternity or perhaps priesthood of tightly related legal families, grimly devoted to their lonely task in rural isolation. The great mover and shaker of the Chancery was Josiah O. Wolcott (1921-1938), the son and father of a three-generation family domination of the court. Most of the other members of the court have very familiar Delaware names, although that is admittedly a common situation in Delaware, especially south of the canal. The peninsula has always been fairly isolated; there are people still alive who can remember when the first highway was built, opening up the region to outsiders. Read the following Chancelleries quotation for a sense of the underlying attitude:

"The majority thus have the power in their hands to impose their will upon the minority in a matter of very vital concern to them. That the source of this power is found in a statute, supplies no reason for clothing it with a superior sanctity, or vesting it with the attributes of tyranny. When the power is sought to be used, therefore, it is competent for anyone who conceives himself aggrieved thereby to invoke the processes of a court of equity for protection against its oppressive exercise. When examined by such a court, if it should appear that the power is used in such a way that it violates any of those fundamental principles which it is the special province of equity to assert and protect, its restraining processes will unhesitatingly issue."

That is a very reassuring viewpoint only when it issues from a person of totally unquestioned integrity, a member of a family that has lived and died in the service of the highest principles of equity and fairness. But to recent graduates of business administration courses in far-off urban centers of greed and striving, it surely sounds quaint and sappy. And many of that sort have found themselves pleading in Georgetown. Just let one of them a bribe, muscle, or sneak into the Chancellor's chair someday, and the country is in peril.

Hedge Funds in Delaware

|

| Trimming the Hedge |

Some day a shrewd observer of the passing scene will notice the peculiar quality which attracts some businesses to the state of Delaware and coin a catchy phrase like Delaware Attractiveness to describe it in a nutshell. It surely underlies the way major national corporations predominantly incorporate under the laws of Delaware; other states don't like that. It probably accounts for the unusual accumulation of national credit card companies in that little state. Right now, it must be surmised to account for 24% of American hedge funds locating in Delaware. Just what is Delaware Attractiveness?

James Madison, the main author of our national Constitution, disliked taxes and debt and celebrated the ability of taxpayers to move to a different state if their home state raised taxes too high. The right to migrate away acts a discipline on state governments tempted to abuse power. A good example now exists in New Jersey, where one percent of the population pays 42% of the taxes, and that one percent is moving out of New Jersey as fast as it can. Eventually, that same 42% of taxes will be redistributed to those who remain, and something will be done about New Jersey state expenditures.

So conversely, little Delaware once had few corporations and little to lose by lowering corporate taxes. Soon, these low taxes attracted corporations from other states to incorporate in Delaware. When credit cards were invented, they were attracted to Delaware by low taxes, gentle regulation, and fair-minded courts. They were non-polluting businesses who employed a lot of rural labor made available by enhancements in agricultural productivity. One member of the Delaware Chamber of Commerce once mused, if it would attract the right sort of business, any hampering state legislation could be changed over a weekend.

|

| Adlai Stevenson |

This spirit of the American Liechtenstein attracted 24% of hedge funds to Delaware before most people knew what a hedge fund is. Without delving into the full complexity of the subject, a hedge fund addresses the instability of investing for the long term with short term money. Promising higher returns than mutual funds which can generally be liquidated overnight, a hedge fund locks the investor's money up for several years and hence needs to tell its competitors (and unfortunately also the investor) comparatively little about what it is doing with his money. One hedge fund operator stoutly defended the need to keep others from knowing his positions, illustrating how competitors who knew his positions would destroy him by "front-running", typically by flooding his positions with sell orders about ten minutes before or after the closing bell on the stock market. And, indeed that was a realistic concern since 70% of current stock trading is performed by unattended computers, who can transact huge sales in seconds when they detect unusual patterns of activity. So, when the stock market crashed in 2007-2009, Congressmen were pressured to find scapegoats. Some blamed computerized trading, and some blamed hedge funds. Quite possibly, it was neither one, since hedge funds were comparatively unaffected by the crash, and "programmed" traders made a great deal of money. However, Delaware is discovering that anyone who visibly escapes a nation-wide panic is under suspicion of causing it, and must fight off hostile legislation at least until the full facts emerge. The ability to front-run, and the ability to avoid having it happen to you, constitute a business advantage, an "edge". There may be more to it than that, but other features are cloaked in the secrecy which hedge funds enjoy, so secrecy is the business plan of hedge funds, apparently more tolerantly treated in Delaware than elsewhere. The price which hedge funds pay for their right to secrecy is the limitation imposed on them by the regulators as to who may be their customers. Therefore, an acceptable hedge-fund customer gets defined as a rich sophisticated person, who knows what risks are involved, and can afford to lose his money. Being in a small, closely-knit community where word of mouth is trusted, adds some degree of safety too. Adlai Stevenson once made an observation about trusting such protections:

In the past it was said, a fool and his money are soon parted. But nowadays -- it could happen to anyone.

As Others See Us

Americans are rightly proud of their Constitution, an achievement no one seems able to match. It's rude to point it out, but some Americans are just a little condescending about Europe's protracted examination of a federal union, and the World's plain inability to design a United Nations Charter that everyone can warm to.

|

| Charles de Gaulle |

But just a minute, look at the centuries of history we have compiled. After eighty years, the American union broke apart in the bloodiest war in our history, proportional to the population at the time. After another century it was safe to suppose we were past that episode, at least mostly.

And if you were an elected representative of one of the European states, charged with assuring a fair result for your constituents, you would have to warn them of something America seems to demonstrate. The new federal government at first had to be deferential to the various states, in order to persuade them to ratify the document. It wasn't an easy sell, and a promise had to be made and reiterated that every single power being surrendered was absolutely necessary for the common welfare of all. And it was necessary to repeat the promise in the Tenth Amendment, that nothing more was being given, nothing up our sleeve. The Eleventh Amendment which followed soon afterward could even be described as a test of sincerity. The states demanded something they really should have been ashamed to ask for, but it was given to them as a demonstration who was still boss. The Federalist party soon broke apart, and had to become craven, only persisting in the assertion of powers it was absolutely clear states needed to give up.

But soon after that, the federal government has never ceased to nibble away at the cheese. Step by step, gradually but relentlessly, power has shifted from state capitals to the District of Columbia. It is now possible to say without serious contradiction that state legislatures really don't have much to do of any importance. Is that the lesson European officials are learning from our history?

Maybe not, but Charles de Gaulle once made a wisecrack suggesting another answer. He wanted to go to Heaven, he said. He really did. But he was definitely in no hurry to get there.

Unwritten Lessons For the European Union

|

| Peace Treaty of Westphalia 1648 |

Europeans, long accustomed to providing Americans with cultural models, sometimes have a little trouble acknowledging the emerging European Union is based on the American design of 1787 Philadelphia. So perhaps it is tactless to emphasize they might encounter some of the same problems. The success of our design is a good reason to imitate it, and may, in fact, be a chief reason to boast about it. But look at it another way. Since we are uncertain why many provisions work so well, we are reluctant to change them; but the proud Europeans cannot be expected to adopt them for a vague reason like that. The main point is to maintain the right degree of vigilance and flexibility, a difficult measurement to make or to transfer to different circumstances. Our Constitution is more right than wrong, so it was intentionally made hard to change. Technically the Constitution has been amended twenty-seven times. Omitting the Bill of Rights, minor technical changes leave us with only five substantial amendments in two centuries, mostly enlargements of the voting franchise. But notice on top of a small base, we have built a legal structure of 100,000 pages of Federal statutes, almost a million pages of regulations, and at least double that number of state laws. Our legal system has many flaws, but smaller ones are easier to change. The great danger for Europeans lies in taking a similarly huge body of multi-nation statutes, then attempting to cram them into a constitution which by definition has been made hard to change. James Madison was not in a position to see this point. Looking for it in The Federalist Papers is futile because they were written to persuade New York to ratify the Constitution, and contain a moderate amount of slant. Add to all that a recognition that the U.S. Supreme Court makes a hundred little amendments every year. It follows it would be bold indeed to list a handful of examples of what the Europeans should avoid at all costs, or omit at their peril. One point seems undeniable, consolidating a number of former colonies is easier than consolidating sovereign nations. Nations start with more sovereignty, so they individually have more power to lose in a consolidation.

The success of our design is a good reason to imitate it, and may in fact be the chief reason to boast of it.

|

The people in power in the individual nations of Europe, and the political factions which elected them don't really want to give up power to a central government in Strasbourg and Brussels. They wouldn't be human if they did. Much the same reluctance inspired our thirteen colonies in the Eighteenth Century, and we circumvented it by excluding state officials from the ratifying conventions. Imagine telling that to the Prime Minister of Great Britain. Having multiple sovereignties breeds jealousies, particularly when the issue is governance. Our ratifying process was rancorous, and echoes of it still reverberate. If transitions are too rapid, even from a bad system to a good one, changes can prove disruptive. For ousted incumbents, all transitions are too rapid. The Europeans additionally have a big problem we didn't have, of multiple languages, so harmony will be slower to arrive -- try to imagine a common market in the Tower of Babel. By lacking multiple languages to rally around, we stumbled into a two-party system, which is actually a big improvement over more-or-less proportional representation by multiple parties. Without having any foresight on the issue, we established a system in which "deals" are made internally and voluntarily, between the extremists within each of the two major parties before the November elections, because by then the central issue has become whether the party might not win with a particular candidate standing on a particular platform. The policy positions of the nominees of both major parties draw closer together, and we don't get a revolution when one of them does win, even by a single hanging chad or questionable mortgage. Unfortunately, the candidates are usually so close to the haphazard process of pre-election compromise that they often consider it less binding than the public does. But by major contrast, in an overtly multi-party system a coalition is formed after the election is over, so the "deals" between splinter parties must also be made after the election is over; voters are completely cut out of the most important decision-making. Splinter parties are an easy recourse for nations with many minorities and are to be avoided at all costs. If a unified nation really cannot be constructed without such recourse, perhaps they would be better off with a King. Since political parties were not mentioned in the American Constitution, this advantage of a two-party system has never been widely debated.

Our experience teaches one more important principle, unwritten in the Constitution. The outstanding message of the American experience from 1787 to 1850, especially the twenty year period after Washington's presidency (and quite unforeseen by the Founding Fathers), is that no party in power can see any merit to the rights of the minority until it has itself spent some time out of power. Nor can any party of complainers and reformers see any merit in prudent caution until it has itself spend some time wielding power. Let's suggest a rule to the Europeans: every political faction is untrustworthy until it has spent two terms in office, and then two terms out of office. It would appear it takes even longer for political parties to mature than it does for governments. We achieved this hat trick by starting out with an Electoral College that didn't work very well, most particularly in the tied election of 1800. Once the Electoral College served its purpose of effecting compromise at the Constitutional Convention, we have largely ignored it as a result of the 1800 fiasco. Perhaps another approach is to change it in stages, considering the Articles of Confederation as a preliminary step to enacting a Constitution, as it were. Unfortunately, most European nations can point to several constitutions in their past, without significant progress toward continental unity. It even seems likely the main problem is not in the Constitution at all, but in wider differences between components at the outset. And a long history of struggles in the past, which we forgot when we crossed the ocean because so few wanted to repeat the stormy voyage.

Maybe even that assessment is too generous to our own history; after all, in 1860 we had our Civil War. You'd certainly hate to think it was essential to have one of those until you reflect that Europe really has had four or five major wars during the past two hundred years. Could it actually be true that a peaceful union leads to further peace? George Washington denounced standing armies, while Dwight Eisenhower warned of the military-industrial complex. Perhaps both of them were warning that war-like behavior leads more quickly to war, by eliminating preliminary steps.

REFERENCES

| The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 | Farrand's Records |

| Chart of the Thirteen Original Colonies | American History |

| U.S. Constitution | Legal Encyclopedia |

George Washington on the Federal Union

|

| President George Washington |