6 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

Four Constitutions

Multi-national unions of republics are uncommon, usually brief and seldom voluntary. America has had three of them, but we only got it right the second time. Uncertain why we succeeded when many others failed, we remain skeptical of changing the rules. The Europeans, on the other hand, are uncertain whether they want to follow the Confederate States of America toward extinction, or the United States of America toward world domination. When deeply considered, it is a hard choice.

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

The American Constitution

Ours is the first written Constitution, and the only one which has lasted two hundred years.

European Common Market and the American Constitution Compared

It is an interesting question how similar the constitutions of the European Union and the United States are, while reaching dissimilar outcomes. A real question arises whether further small modification might trigger major changes, or whether Constitutions are just less important than our Founding Fathers believed. If we expect different outcomes, It can be an important question.

...Ratification, Bill of Rights and Other Amendments

The 1787 Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights. Few except Madison himself were opposed to adding one, but many other delegates would have failed election without promising it. Negotiations at the Convention had proved so excitingly innovative that time ran out before the Convention had to adjourn with only a promise of a Bill of Rights, first thing.

Except for the Bill of Rights, the American Constitution was the work-product of the 1787 Philadelphia Convention. It described how merging the sovereignty of thirteen independent states might work, without any King or aristocracy -- a Union of citizens with shared sovereignty, and separated powers, internally balanced. These were unfamiliar but exciting ideas, greeted with vast public enthusiasm after the Constitution was finally ratified, endorsed by national heroes. As had been promised, adding a Bill of Rights was the first order of business of the new Federal Congress.

Delegates who wrote the main document felt uneasy about the reaction of state legislatures, but public enthusiasm soon swept those fears away. Nevertheless, since implementation could only go ahead with the consent of ten legislatures, the document was reassuringly circumspect about the few enumerated powers transferred to the new national government. The power to levy taxes was definitely among them, but not direct taxes, a concept which remains a little mysterious even in modern times. All unmentioned powers could remain with the states, but the Revolutionary War had highlighted those few powers previously untransferred from the states by the Articles of Confederation, which must lodge within the Federal division of government, now permanently charged with the common defense. The Constitutional Convention remained uneasy about the reaction of state legislatures, but this was a point so essential it had to be confronted unblinkingly.

A completely revised three-level (Federal, state and local) concept of government was at first called the "federal union" although by repeated usage the term "federal government" soon referred only to the national level. Anything unspecified remained a reserve power of the people themselves, to confer or withhold from government later. Madison felt this arrangement, plus the latent ability to compose local Bills of Rights at the state level, was clear enough and ought to reassure the states about excessive power at the top. Nevertheless, Thomas Jefferson, Elbridge Gerry, Patrick Henry, and some other States Rights politicians, were able to stir up public insistence and were joined by others with different agendas -- especially slavery or its abolition -- which were cloaked as demands for a Bill of Rights. In fact, no one was actually opposed to a Bill of Rights, which had been the format adopted by the "Glorious" English Revolution of 1688, and was now co-opted by the Constitutional Convention. The intimation there was serious opposition to a Bill of Rights proved highly spurious at the state ratifying conventions, along with fears that the Constitution itself would be unpopular with the people. The Bill of Rights added little of substance except repetition, but future commentators like Associate Justice Joseph Story came to believe it was more important than it seemed. The design and forceful language had the effect of preventing Congress from even considering certain actions, as contrasted with enabling subsequent Congressional correction of what was underway. Since the main body of the Constitution concentrated such activity in the national Congress, Story felt the overall effect was dramatic.

The agitators for a new Constitution had themselves started out with only vague ideas of a few essential changes: Madison wanted the general format of the Roman Republic and some general notions of separating and balancing power, George Washington wanted a nation he could be proud of, one that at least paid its soldiers, and Robert Morris understood that the leaders of national defense must control enough revenue to pay necessary costs of defense. There were a few others with some private concerns: some were there to protect the system of slavery in the South, some were fearful of preserving minority rights within a system of majority rule, which surfaced as protecting the rights of small states. Only Benjamin Franklin seemed to understand how sustaining a successful system of fair honest dealing, occasionally requires a harmless amount of compromise, even guile, in its leadership. Franklin was always prepared to do the right thing for the wrong reason, even though he preferred not to.

Historians differ on whether Washington or Madison gets credit for the idea of a Constitutional Convention; it scarcely matters whether Madison proposed it to Washington, or whether Washington maneuvered Madison into proposing it. These two Virginia neighbors both wanted a new constitution and had argued for several years it was needed. A much more important issue was the one John Dickinson of Delaware interposed. With proportional representation, a union of several unequally sized states will always lead to the larger states dominating, and smaller ones soon refusing to be dominated. Among unequal voters, the principle of majority rule must be skillfully modified. This was not a new fear for the ten small states, but it may have gone blithely unnoticed by the three biggest ones, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. John Dickinson of Delaware had written the Articles of Confederation and was well aware the small states would make almost any sacrifice to prevent a national government from being controlled by the three big ones, Virginia in particular. So when Dickinson at the Convention took Madison aside for a little frank chat, Madison's eyes were probably suddenly opened to what other rhetoric had really meant. If he wanted his Constitution, he would have to compromise on the election of Senators: every state no matter how small or large must get as many senators as every other state. Flying the flag of equal votes for every state, power was then more evenly shared with states of unequal population. By the Convention's rules, the small states had nine of the twelve votes and would disband the Convention unless their problem was addressed. With this detail clarified, the Convention could get on with business. Up to that moment, Madison had probably never recognized that one of the most important freedoms being demanded, was freedom of weaker states from stronger ones. Dickinson's solution of a bicameral legislature was a brilliant improvement on the original design. The people chose their own Representatives to the House; the state legislatures chose their own Senators. The small states would always be somewhat over-represented in the Senate (and electoral college), the large states would dominate the House of Representatives. Only when population growth later constrained each Congressman to represent an unwieldy number of constituents, was this automatic rebalancing disturbed. By that time, the party system had appeared. Consequently, still later the XVII Amendment took the selection of Senators away from the Legislatures. At present, considerable rural disquiet is being expressed at the domination by urban machine "safe seats" in the House of Representatives, so the situation is again fluid.

Some difficult transition problems were simply set aside. Fear of a Civil War in eighty years would not have swayed very many Delegates to bring up issues which could disrupt ratification immediately. Responding to suspicious delegates' fears of the federal government's power over the states, firm limitations were placed on what the Union could later impose on its formerly sovereign components. In general, that was reassuringly little more than enough to conduct a war, foreign affairs and disputes between the states. Although there was sympathy with James Madison's plea for the federal Congress to be able to veto state laws, wiser heads counseled it would be too risky to ask for that, too soon. Madison was particularly upset by this defeat, which he felt would ultimately make the Constitution a failure. Madison's extensive study of other governments while seated at the foot of John Witherspoon at Princeton apparently enabled him to persuade his less learned colleagues that plausible internal arrangements would confer power without the need to bully states into outright resistance. However he may not have completely convinced himself and, as the Civil War approached, he may have been right. However, his colleagues elected to accept that risk. As delegates got into the spirit of the thing, it did seem adequate for the central government to conduct foreign affairs, police the coasts, issue a common currency, and restrain the tendency of states to take advantage of each other in interstate commerce. If that proved inadequate, they could "promote the common welfare."

In time, the conventioneers had grown to know each other better, and threw in a few harmless federal powers without objection, like patent and copyright protection. Delegates saw some value for uniform rules on even peripheral matters, so long as no one objected. A motion was made by Charles Pinckney of South Carolina, who certainly was not going to file for any patents. Looking over the list, no name suggests itself as a plausible real source of it except Benjamin Franklin, who was always careful to cover his tracks.

The ensuing public outcry for adding a Bill of Rights was apparently a surprise, and it quickly became apparent the Constitution could not be ratified without it. Madison was particularly concerned that re-opening the Constitutional Convention, possibly with new membership, could upset the whole arrangement permanently. Once Massachusetts attached some proposed Amendments, that procedure was repeatedly followed during other ratification conventions. It served as an informal reassurance that a Bill of Rights would indeed be soon added, and some states agreed to ratify with that condition pending. A few states even then refused to ratify until a Bill of Rights was actually enacted during the First Congress.

Madison was appointed chairman of the committee which received over two hundred proposals of new rights. He firmly cut them down to a dozen terse clauses and rammed it through. Subsequent experience with this brief addendum of a dozen or so phrases has consumed a considerable amount of the time of judges and courts so that the Bill of Rights now represents the real content of the Constitution to many citizens. That is a warning of what might have happened if a hundred such rights had been enumerated, and indeed what has happened to the French and other constitutions which did follow Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry's inclinations. Nevertheless, we owe a debt to the anti-federalists for the raw material out of which Madison forged the succinct and ringing Bill of Rights. It was a tricky thing to accomplish, for it soon became clear that this idea of government became the core of the French Revolution and its reign of terror while Jefferson was American Ambassador, soon to become our Secretary of State, Vice President, President, and founder of the two-party system. He and Madison nearly broke George Washington's heart over the anti-federalist viewpoint, which can be traced to Rousseau's idea that everyone is born as a naturally good person. Left to themselves, he thought the goodness of mankind would emerge, even without any government at all. Jefferson learned many lessons that anarchy serves us poorly during his years in later public life, but he never did stop talking about practical matters in iambic pentameter. For our Constitution to survive episodes of leadership with this viewpoint is certainly a testimony to its resilience. One can almost imagine Madison speaking directly to Jefferson in Federalist # 51:" If men were angels, no government would be necessary." Nevertheless, history seems to show it was Madison who mainly shifted position, not Jefferson, although both of them moved toward the center.

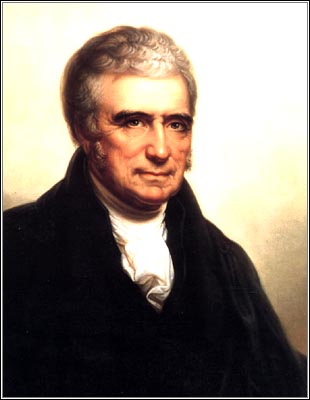

The perils of aimless wandering seem particularly vivid in view of the paucity of details about the Judicial Branch in the Constitution. Just as the duties and procedures of the Presidency were left to George Washington to devise, the court system was mostly left in the hands of the legal profession for several decades. In time, it migrated pretty much to one man, Chief Justice John Marshall, a highly skeptical cousin of Thomas Jefferson but a worshiper of George Washington. Senator Ellsworth of Connecticut cleared the way for himself as Chief Justice but died early. Associate Justice Joseph Story organized the brilliant insights of Marshall into a legal code. There emerged three stars in our legal sky, but Marshall was the shining light.

This near-total neglect by a Constitution to say anything much about two out of three branches of government may in part reflect inordinate concern of the Delegates about the Legislative branch, inordinate respect for George Washington as the assumed first President and dominance of the Legal Profession in its own complicated field. But there is a balanced moral and economic quality underlying the Constitution, which resists complete definition. Some of the gaps show the Bill of Rights was not the only matter pushed aside for later. Benjamin Franklin, the youngest son of his father's twenty children, was almost alone in urging that The Founding Fathers ought to exhibit a little faith in future generations.

REFERENCES

| A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution of the United States: Containing a Brief Commentary on Every Clause, Explaining the True Nature, Reasons, and ... Designed for the Use of School Libraries and General Readers; Joseph Story: ISBN-13: 978-1886363717 | Amazon |

| Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788: Pauline Maier: ISBN-13: 978-0684868554 | Amazon |

Almost immediately, political America was thrown into a year of state ratification conventions. Massachusetts initiated the concept of ratifying the Constitution, attached with eight or nine amendment proposals for the Bill of Rights. When the First Congress finally convened, it faced almost two hundred proposed amendments, and Madison made sure he was chairman of a committee to deal with them. Practically alone he pared them down to a succinct twelve which survived as the first order of business of the new Congress. Almost unnoticed, he made a deal with Oliver Ellsworth the leader of the Senate, to pass the Bill of Rights in exchange for passing the Senate's Judiciary Act in the House of Representatives. Out of this combined beginning, the power and scope of the Judiciary Branch was born. But while that is a subject for later chapters, Madison never achieved a more skillful moment in his political life, than this pivotal one.

C10.....Ratification

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

Although the Constitution could officially have been declared ratified when nine states had agreed to it, New York and Virginia were such important hold-outs that the new nation would almost certainly fail without them. Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, both of the authors of the Federalist Papers , threatened to have NewYork City succeed if the whole state would not ratify it. Such was their power and prestige, that New York ratification soon followed.

Reference: 8500/14

Concessions and Agreements

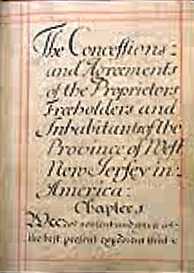

|

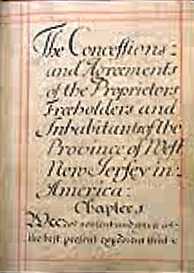

| Concessions and Agreements |

The United States Constitution is a unique achievement, but it had significant precursors, many of which James Madison had studied at Princeton. In the days of difficult ocean travel, almost all colonies were bound by an agreement to maintain loyalty to their European owners in spite of receiving latitude to govern themselves. Charters and documents defining these roles were generally written by the owners, and the colonists could pretty much take them or leave them. In the case of New Jersey in 1664, however, a very formidable lawyer and friend of the King named William Penn was drawing up agreements to his own conditions of sale, taking care that the grant of governing authority he received was favorable. Penn's relationship to the King was unusually good, to say the least. He had more reason to be wary of nit-pickers in the King's administration, trying to anticipate every conceivable disappointment for some successor King.

For his part, Penn wanted to make colonial land attractive to re-sell to religious groups who had experienced harsh government oppression; he wanted no obstacles to his announcing there would be no religious oppression in New Jersey. He was offered the role of sub-king although he hastily rejected any such title, and needed to repeat the formalities of the Charter to define his role and reassure his settlers about that matter. Furthermore, he was dealing with the heirs of Carteret and Berkeley, active participants in North and South Carolina. So Penn's method of achieving basic rights was influenced by prior thinking in the Carolinas, as the thinking of John Locke secondarily influenced matters in Delaware and Pennsylvania. These ideas were incorporated in a New Jersey document called "Concessions and Agreements." The concepts were not wholly the ideas of William Penn, but he did write it, and it does contain many ideas that were uniquely his. Understandings about limits were set down, argued about, and agreed to. The owner risked money, the colonist risked his life. Neither would agree unless a reasonable bargain was struck in advance of any dispute. Furthermore, the main value of a colony was beginning to shift from trading rights to real estate rights. Carteret and Berkeley had not only been principals in both the Carolinas and the Jerseys but had been involved in a number of such investments in Africa and the West Indies; New Jersey was just another business deal. It was conventional for documents of this type to define the method of selection of a governor, the establishment of an assembly of colonists, and some sort of council to attend to day to day affairs. In that era, few colonists would cross the ocean without a guarantee of religious freedom, at least for their own brand of religion. Standard clauses which may sound strange in today's real estate world, were then necessary because it was a transfer of not merely land, but also the terms of government. In the case of the Quaker colonies, many of these stipulations were included in the earlier charter from the King. It seems very likely that Penn hovered around and negotiated these points which he wished to have the King agree to; and then once the land was safely his, Penn repeated and expanded these stipulations with the colonists in his Concessions and Agreements . It wasn't exactly a Constitution, but it reads a lot like the one America adopted a century later.

|

| Proprietors House |

Quakers had suffered persecution and imprisonment, and knew exactly what they feared; on the other side, it seems likely Carteret and Berkeley were less interested. So this real estate transfer document conceded almost anything the colonists wanted and the King would stand for, couched in conciliatory phrases. For example, no settler was to be molested for his conscience, and liberty was to be for all time, and for all men and Christians. Elections, by the way, must be annual, and by secret ballot. While law and order must prevail, nevertheless no man is to be imprisoned or molested except by the agreement of twelve men of the neighborhood. On the matter of slavery, no man was to be brought to the colony in bondage, save by his own consent (that is, indentured servants were to be permitted). And in what proved to be a final irony for William Penn, there was to be no imprisonment for debt. Almost all of these innovative ideas survived into the U.S. Constitution a century later, but the most innovative idea of all was to set them all down in a freely-made agreement in writing. This was not merely how a government was organized, it defined the set of conditions under which both sides agreed it would operate.

It was, of course, more than that. It was a set of reassurances to settlers who had been in New Jersey before the English arrived that they, also, would be treated as equals. It was a real estate advertisement to the fearful religious dissenters back in England that it was safe to live here. And it was a reminder to future Kings and Parliaments that this is what they had promised.

The pity and a warning, is that the larger vision of a whole continent governed fairly by common consent may have been too grandiose for a little band of New Jersey Quakers, surrounded as they were by an uncomprehending world. All utopias are helpless when stronger neighbors reject the basic premise. However, it was the expansion of the pacifist concept to the much larger neighboring territory of Pennsylvania that proved to be just too much for such a small group of friends to manage by consensus, particularly when unbelieving immigrants began to outnumber them. But the essential parts of it certainly remained in the minds of delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. When the minutes of the Constitutional Convention speak of the "New Jersey Plan", the Concessions and Agreements was what they had in mind.

REFERENCES

| Concessions and Agreements of New Jersey 1676: William Penn | New Jersey State Library |

| Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City: Howard Gillette Jr.: ISBN-13: 978-0812219685 | Amazon |

Declaration of Rights of the Continental Congress, October 14, 1774

|

| John Sulllivan |

Whereas, since the close of the last war, the British Parliament, claiming a power of right to bind the people of America, by statute, all cases whatsoever, hath in some acts expressly imposed taxes on them and in others, under various pretenses, but in fact for the purpose raising a revenue, hath imposed rates and duties payable in these colonies established a board of commissioners, with unconstitutional powers, and extended the jurisdiction of courts of admiralty, not only for collecting the said duties but for the trial of causes merely arising within the body of a county.

And whereas, in consequence of other statutes, judges, who before held only estates at will in their offices, have been made dependent on the Crown alone for their salaries, and standing armies kept in time of peace:

And whereas it has lately been resolved in Parliament, that by force of a statute, made in the thirty-fifth year of the reign of Henry the Eighth, colonists may be transported to England, and tried there upon accusations for treasons, and misprisions, or concealments of treasons committed in the colonies, and by a late statute, such trials have been directed in cases therein mentioned.

And whereas, in the last session of Parliament, three statutes were made; one, entitled "An act to discontinue, in such manner and for such time as are therein mentioned, the landing and discharging, lading, or shipping of goods, wares, and merchandise, at the town, and within the harbor of Boston, in the province of Massachusetts Bay, in North America"; and another, entitled "An act for the better regulating the government of the province of the Massachusetts Bay in New England"; and another, entitled "An act for the impartial administration of justice, in the cases of persons questioned for any act done by them in the execution of the law, or for the suppression of riots and tumults in the province of the Massachusetts Bay, in New England." And another statute was then made, "for making more effectual provision for the government of the province of Quebec, etc." All which statutes are impolitic, unjust and cruel, as well as unconstitutional, and most dangerous and destructive of American rights.

And whereas, assemblies have been frequently dissolved, contrary to the rights of the people, when they attempted to deliberate on grievances; and their dutiful, humble, loyal, and reasonable petitions to the Crown for redress, have been repeatedly treated with contempt by His Majesty's ministers of state:

The good people of the several colonies of New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New Castle, Kent and Sussex on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, justly alarmed at these arbitrary proceedings of Parliament and administration, have severally elected, constituted, and appointed deputies to meet and sit in general congress, in the city of Philadelphia, in order to obtain such establishment, as that their religion, laws, and liberties may not be subverted.

Whereupon the deputies so appointed being now assembled, in a full and free representation of these colonies, taking into their most serious consideration, the best means of attaining the ends aforesaid, do, in the first place, as Englishmen, their ancestors in like cases have usually done, for asserting and vindicating their rights and liberties, declare, That the inhabitants of the English colonies in North America, by the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the English Constitution, and the several charters or compacts, have the following rights:

Resolved, N. C. D. [Nemine contradicente, no person disagreeing]1. That they are entitled to life, liberty, and property, and they have never ceded to any sovereign power whatever, a right to dispose of either without their consent

Resolved, N. C. D. 2. That our ancestors, who first settled these colonies, were at the time of their emigration from the mother country, entitled to all the rights, liberties, and immunities of free and natural-born subjects, within the realm of England.

Resolved, N. C. D. 3. That by such emigration they by no means forfeited, surrendered, or lost any of those rights, but that they were, and their descendants now are, entitled to the exercise and enjoyment of all such of them, as their local and other circumstances enable them, to exercise and enjoy.

Resolved, 4. That the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council: and as the English colonists are not represented, and from their local and other circumstances, can not properly be represented in the British Parliament, they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved, in all cases of taxation and internal polity, subject only to the negative of their sovereign, in such manner as has been heretofore used and accustomed. But, from the necessity of the case, and a regard to the mutual interest of both countries, we cheerfully consent to the operation of such acts of the British Parliament, as are bona fide, restrained to the regulation of our external commerce, for the purpose of securing the commercial advantages of the whole empire to the mother country, and the commercial benefits of its respective members; excluding every idea of taxation, internal or external, for raising a revenue on the subjects in America, without their consent.

Resolved, N. C. D. 5. That the respective colonies are entitled to the common law of England, and more especially to the great and inestimable privilege of being tried by their peers of the vicinage, according to the course of that law.

Resolved, N. C. D. 6. That they are entitled to the benefit of such of the English statutes as existed at the time of their colonization; and which they have, by experience, respectively found to be applicable to their several local and other circumstances.

Resolved, N. C. D. 7. That these, His Majesty's colonies, are likewise entitled to all the immunities and privileges granted and confirmed to them by royal charters, or secured by their several codes of provincial laws.

Resolved, N. C. D. 8. That they have a right peaceably to assemble, consider of their grievances, and petition the King; and that all prosecutions, prohibitory proclamations, and commitment for the same, are illegal.

Resolved, N. C. D. 9. That the keeping a standing army in these colonies, in times of peace, without the consent of the legislature of that colony, in which such army is kept, is against law.

Resolved, N. C. D. 10. It is indispensably necessary to good government, and rendered essential by the English constitution, that the constituent branches of the legislature be independent of each other; that, therefore, the exercise of legislative power in several colonies, by a council appointed, during pleasure by the Crown, is unconstitutional, dangerous, and destructive to the freedom of American legislation.

All and each of which the aforesaid deputies, in behalf of themselves and their constituents, do claim, demand, and insist on, as their indubitable rights and liberties; which cannot be legally taken from them, altered or abridged by any power whatever, without their own consent, by their representatives in their several provincial legislatures.

[Author: John Sulllivan, Delegate and later Governor, New Hampshire]

REFERENCES

| A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution of the United States: Containing a Brief Commentary on Every Clause, Explaining the True Nature, Reasons, and ... Designed for the Use of School Libraries and General Readers; Joseph Story: ISBN-13: 978-1886363717 | Amazon |

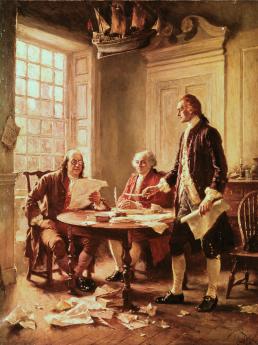

Sources of Revolutionary Populism

|

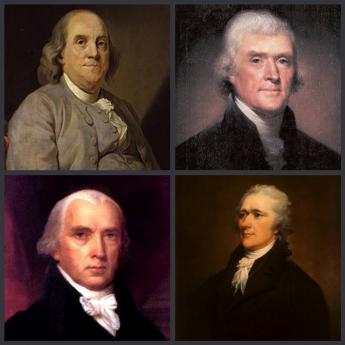

| Founding Fathers |

Those who now look back at the Founding Fathers often fail to account for the aging process during the eleven years between the Declaration of Independence in 1776 to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The two events took place in the same building, Independence Hall, and many participants of the Convention were fellow Revolutionary War veterans. But there was originally a great social difference between a colonial leader and a teen-aged soldier at the beginning of this period, which tended to seem blurred by the experiences of the war. Someone who fought and was wounded as a common soldier might later grow into the dignity of a former war hero, but underneath this veneer was a very different experience from an early leader of the colonial rebellion, or after the onset of serious hostilities, an older man who seemed eligible to be a Revolutionary officer. The original generation of rebels conspired to restore proper British rights for individual colonies, while the teenager who fought in the Continental Army under his idol George Washington saw himself as fighting for the freedoms of individuals, living in a new nation.

What emerged were two generations of Founding Fathers, one of which was generally an officer fighting for the right of his state to be fairly represented, the other a young common soldier, fighting for the individual right of free speech. One wanted to protect his colonial region's religion, the other wanted the freedom to choose his own religion. Both of them felt entitled to say how things were to be run, but young men eventually become older men. No better example of aging's transformation of attitudes could be found than the life of John Marshall. This teenaged wounded veteran of the Battle of Trenton evolved into Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the author of a multi-volume biography of George Washington, and almost the last man standing who could be called a Federalist. Other teenaged soldiers took different paths in life.

History belongs to the victor, so it is also important to recollect that almost a third of the colonists had been Tories. In general, the upper crust of society tended to be more loyalist. Thousands of Loyalists fled to Canada, and thousands more fought on the British side. When General Clinton abandoned the occupation of Philadelphia, three thousand Loyalists accompanied him. The loss of these more educated and wealthier citizens and the lowered public profiles of those who remained in America skimmed off a considerable portion of the natural leadership of the colonies. Those young men who were left behind were victors, often exhilarated to discover that if they did not lead, no one would lead.

The embodiment of these population shifts was to be found in state governments with unicameral legislatures, popular election of judges, and weak executives -- all of which have since been repudiated by experience, but all of which reflect a distrust of leaders. Partly this might be attributed to lack of experience, greater reliance on collective government by the herd instinct, the recklessness of youth, and fear that power will eventually return to the hands of those who are educated to handle it. The hostility of the lower classes to those who are better off has many causes, but in this situation, it was promoted by unexpected elevation to leadership, combined with a subsequent determination not to lose power again -- balanced against the rather strong possibility that they would. Add to this the continued influx of immigrants fleeing from foreign oppression, and it is not surprising that the result is an enduring strain of populism stirring up a latent tendency to class warfare. You, too, can be President; but you must fight if you expect to succeed. The former aristocratic attitude was that you are born to rule, as long as you don't do something stupid.

REFERENCES

| The Great Courses: History of the United States, 2nd Edition Course #8500: Lecture 14 Creating the Constitution: Aurthor: Allen C. Guelzo: ISBN: 156585763-1 | The Great Courses |

Appealing the Constitution to a Higher Authority

|

| Justice Robert H. Jackson |

According to Justice Robert H. Jackson, "We" (The Supreme Court) "are not final because we are infallible, we are infallible because we are final." Scoop Jackson was the last Justice who never went to college or graduated from Law School, so his viewpoint concentrated on the practical outcome of a situation. In fact, the father of our constitution, James Madison, was learned in the history of many constitutions, and was well aware of allusions to divinity in the construction of our governing document, particularly when the sources of strong beliefs couldn't be grounded in evidence. However,the Age of Enlightenment was highly religious, so they gave credit to divine guidance when they really were imitating the Legal profession.The lawyer's system of progressive appeal to a hgher court of appeals was a very clever adaptation of recognition that most problems are pretty simple andcan be handled without much training.The Constitution is an attempt to reconcile our culture to the needs of government and the revelations of controversy. Composed by Enlightenment rationalists within a highly religious environment, the Founding Fathers were careful to use the metaphors of Religion, even though many were personally skeptics about the substance. Indeed, the Penman of the Constitution who ultimately wrote most of the words was Gouverneur Morris, a flagrant libertine. It had been the tradition of Constitutions to describe their culture by allusion to epic poems, drawing inferences about Right and Wrong from what had subsequently happened to ancient heroes after similar situations unfolded. Some would put the plays of Shakspere in that role in 1787, but the evidence is stronger for Roman writers, like Cato and Cicero. In my own view, this leap of faith was only divine in the sense it was a one-way street. A citizen might try to emulate the ancients, but appealing back to them was not likely to work.

Although the Constitution can be viewed as bridging a gap between Culture and Common Law, or perhaps as placing a guardhouse between them, this relationship is not spelled out and therefore, in theory, might be changed. Other cultures, perhaps the native Indian, or the Catholic Church of Central Europe, might be substituted, or other legal structures resembling the Napoleonic Code might serve on the opposite side of the bridge. These substitutions were a legal possibility, but there is little doubt the American leadership intended for an Anglo-Saxon culture, linked with Francis Bacon's legal system, to prevail under a distinctively American flag. Because of our debt to France for then-recent assistance, there was once the possibility of French coloration to our culture, but the excesses of the French Revolution soon ruled that out. Some modern observers have capsulized the scene: First, we got the British to help throw out the French in 1754; and then in 1776, we got the French to help us throw the British out. Both our allies thought we played their game, but we were playing our own. The new Constitution specified no laws, but with little doubt the Framers intended the states to adopt British Common Law without the infelicity of saying so.

|

| Bill of Rights |

And then there is the Bill of Rights. Madison had great faith in the ability of structure (separation of powers, term limits, etc.) to command predictable outcomes, and initially resisted any need for a Bill of Rights. But the Ratification Conventions in the states showed him the need to yield. The First Congress soon enough confronted over a hundred proposed rights in petitions from the states, especially the four big ones. If anyone else had been in Madison's position, our Bill of Rights would resemble the European one today, fifty pages long and growing. That outcome would have greatly weakened the Legislative branch since after protests about Mother Nature subside, the legal fact emerges that Rights are merely laws which no majority can overturn. They might even be characterized as a contrivance for transient majorities to promote the permanence of their viewpoint.

|

| The Founding Fathers |

But they are not the only contrivance in politics. Enshrinement of the Founding Fathers elevated their political positions into near divinity, whereas debunking the Founders personally undermines their symbolism as statues and myths. There was too much of this during the romance period of the Nineteenth century, but also in von Ranke's later marginalization of History into mere scholarship and footnotes, which was a reaction to it. The Founding Fathers themselves now supplant Achilles and Cincinnatus in our lexicon, and we have little choice but to accord more weight to their original intent in the Constitution, than to contemporary reasonings. Indeed, we are forced to acknowledge more similarity between George Washington's fictitious cherry tree than to his relations with Peggy Fairfax, when we interpret his thundering "Honesty is the best policy" in the second inaugural address. It is admittedly a difficult choice, but Justices now need to consider what his audience widely believed was his original intent, more than what later archeological discoveries uncover. Justice Scalia is correct in placing more weight on the original intent of the Founding Fathers than contemporary reactions to the same words. But in occasional conflicts between myth and reality, it seems safer to consider what the audience then widely believed, than what modern audiences would guess at.

Repairing Constitutional Defects

|

| James Madison |

Out of several thousand proposed ones, there have only been 27 successful amendments to the Constitution in two centuries; it's been intentionally hard to get an amendment passed. The Federalists wanted no amendment process at all; the anti Federalists wanted repeat conventions in which the whole document would be thrown on the table for reconsideration. The original document probably turned out better because of this tension; if it's hard to change, you better do it right the first time. And amendments had better be short and clear.

There will, of course, have to be some mid-course adjustments, most notoriously the XII Amendment, correcting drafting amateurishness which promptly led to all sorts of confusion in the election of the President and Vice-President. It was almost a Gilbert and Sullivan comedy, with the appearance of a tie vote in the 1800 Electoral College between Jefferson and Burr. Since the election campaign had been conducted with the clear intention that Burr would be the vice president on a combined ticket, what was really overlooked was the possibility that ambition would so overwhelm a candidate that he would niggle and cavil about a technicality, essentially trying to steal an election from a running-mate. When Burr later killed Jefferson's enemy Hamilton in a duel, not only was Burr twice disgraced, but the whole episode terminated expectation that gentlemen in a high office could always be depended on to do the right thing. Although philosophical debate can continue whether mankind is inherently good or inherently evil, American law now proclaims a presumed innocence of the accused, while privately assuming universal frailty of everybody.

Sometimes the amendment process has been brushed aside. William Henry Harrison was the first president to die in office, making John Tyler the first vice-president to face certain ambiguities of the Constitution over exactly what had been intended. By that time, the tradition had grown that the vice-presidential candidate was usually a member of the second strongest faction within the winning party. Combining the two makes a stronger ticket but a secretly jealous one. When the contingency of presidential death in office actually happened, there were voices that the vice-president was intended to remain, vice-president, while assuming the extra powers and duties of the president. Rather than have a debate or a Supreme Court wrangle, Tyler settled any such question by simply making himself president, thus establishing an enduring tradition. This solution raised the nit-picker difficulty that still no official succession plan has been provided for a vacant vice-presidential post. Instead of fixing this flaw, it has been ignored. The courts rely on the precedent they have set, which can be defended as constitutionally enshrining common sense, or attacked as refusing to admit making an error.

Somewhat similar corrective themes continue through Amendments XXII (two term Presidential limit), XXV (Presidential succession), XXVII (Congressional compensation). At least when dealing with politicians, it is better to be too specific than too trusting.

The Fourteenth Amendment is clear enough in its many sentences, and noble in intent. But that intention to reverse the original Constitutional tolerance of slavery and the later injustices of Reconstruction is couched in broader language than necessary for that purpose alone. It thus weakens itself by hinting sanctimony, the inclusion of soaring principles. As the grievous wounds of the Civil War have gradually healed, Abolitionists as well as slavers now seem often to have acted with excess, and malice toward some. Others may honorably disagree with this view. Nevertheless, it is quite right to emphasize that just as undue deference should not be accorded to some, undue suspicion should not be inflicted on others.

By a series of amendments, the right to vote has been extended gradually over the centuries. Amendment XXIV (Abolition of poll taxes) probably had other motivations but has the effect of removing a restraint on the vote of poor people, Amendment XIX (Women's suffrage), XXIII (Presidential electors for the District of Columbia), and XXVI (Reducing the voting age to 18) can be characterized as removing discrimination, but also can be seen as a gradual extension of suffrage by those who already have it, to others they have mistrusted for reasons defensible and indefensible. The common goal is to achieve sufficient trust and education to make any restrictions seem unnecessary to everyone while recognizing that continuing immigration of other cultures creates restlessness at the margins. Furthermore, poor people will outnumber rich ones for a long time to come and hence could potentially mistreat the minority. As long as only a minority of the enfranchised population at any level troubles to exercise its right to vote, the level of discomfort with this issue is enough to stimulate progress toward universal suffrage, while satisfaction with gradualism allows time to adjust to it.

Even Universal Franchise can be viewed with suspicion in a polarized political climate. Currently, a vigorous campaign for mandatory voter identification has been met with an equally vigorous denunciation as an attempt to deny the franchise to the poor. Typically, such proposals require the presentation of some government document with an identification photograph, such as a driver's license, to be presented at the voting place. The uproar this proposal has created has itself created suspicion of motive. Those who have experience with ballot-stuffing in elections refer to their common suspicions as "doing it the old-fashioned way." Citizens who make a few dollars as the poll-watchers report that the traditional procedure is as follows:

At least a third of registered voters do not vote, even in a contested Presidential election, and in big-city off-year primary elections, sometimes a heavy majority do not. In the old-fashioned way, the poll watchers wait for dinner time in a sparsely-attended precinct, with no newspapers or poll-watchers of the opposite party present. The registration lists are produced, and everyone who has not voted is voted for the desired candidate. The ruse is enhanced by driving in busloads of party loyalists, claiming to be the absent registered voter; and after casting their ballots, they are bussed off to another polling place to repeat the performance as often as there is time. Matching identification with the voter registration upsets this "good old way", in a manner which has nothing to do with the inability to afford a driver's license, or similar lame excuses.

Amendment XVI (Income tax) may cause dissatisfaction because America has traditionally . But it really is just a mid-course adjustment in the legal system, since a court had declared income taxation to be unconstitutional, and the Constitution was simply amended to remedy that misapprehension. An implicit point, however, is that as the federal government preempts the sources of taxation for itself, the states are weakened by the need to appeal for revenue. The XVII Amendment (Direct election of Senators) rather severely curtailed the control of the states over the central government, but the XI Amendment strengthened the states by forcing the citizen of a different state to sue a state in its own court. The issue of state and federal control, so central to the original Constitution, nowadays seems to be fading in the public mind.

And finally, we are left to consider the first ten amendments, the so-called Bill of Rights. While Madison always inclined somewhat in that direction, and grew more defiantly libertarian as he got older, the situation he faced when the first Congress convened was daunting. Between final ratification and actual convening of much the same people into the first congress, the states submitted over two hundred petitions for rights to be included in the Constitution by amendment. Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry had been tireless in stirring up the demand for rights to protect the individual from the government. Much of this reflected the French Revolution which went on for ten years during this period and drew on affection for France for its assistance to the struggling colonies during their rebellion against Great Britain. Others, of course, only needed to look toward George Washington, who had once heard the screams of Braddock's soldiers as they were tortured to death by the French and their Indian allies at Fort Duquesne. Washington had earlier and personally started the French and Indian War. John Adams was not pleased by torch-lit mobs breaking windows in Philadelphia in sympathy with France. So, as the main leader in the new Congress, Madison had the task of satisfying everybody about the Bill of Rights he had promised. It must be acknowledged that he did a masterful job. Not everybody was convinced it was a natural right of mankind to give everyone everything it might seem desirable to have. Somewhere in this arose the accepted definition of a right as something everyone would give to others, in order to have for himself. Madison was forced to search for common denominators, the maximum -- and minimum -- a number of rights which everyone would agree to. It offended his constitutional craftsmanship to see Congress drowned in a rush to confer greater force than law by saying the same thing in an amendment. Indeed, when some advocates strove to make a dubious right into a constitutional right, almost by definition it was not something everyone would agree to in order to have for himself. Madison did things in his life that may be questioned, but his achievement of condensing this hotch-potch of proposals into ten simple declarations, and then getting a raucous inexperienced congress to pass it -- is a political achievement to be marveled at. Even two centuries later, anyone who proposed opening up the Bill of Rights and recasting it in conformity with more modern understanding, would be hooted out of the room. May that ever remains the case.

Amendments IX (Non-enumerated rights) and X (Rights reserved to the states) deserve a different emphasis. Here lay the promise that the federal government had been proposed to achieve only those things a central government could achieve better; the states could do everything else. For this to be workable, the enumerated rights had to be comprehensive enough to satisfy the Federalists, and not include anything the anti-Federalists thought was improper. The anti Federalists knew very well this included everything the Federalists could possibly get the states to agree to, so the border was inevitably contentious. They got it wrong with slavery, and some of the amendments made mid-course adjustments. Boundary warfare would continue indefinitely in Congress, and sometimes wars and depressions cause proponents to change positions. But the document, freely agreed to by formerly sovereign states, has endured as nothing even remotely comparable has endured.

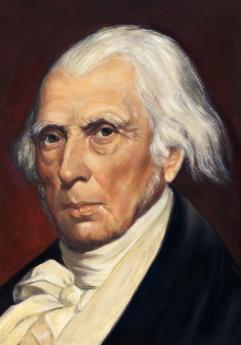

James Madison

|

| James Madison |

JAMES Madison was born (1751) a rich Virginia planter, was a major factor in the composition of the U.S. Constitution, became secretary of State and President of the United States for two terms (1812-20), and died (1836) impoverished at the age of 85. Because the Constitutional Convention was conducted in secrecy, we cannot be entirely certain which parts to attribute to him, or even what his personal position had been on many issues. He was Chairman of the Committee of the First Congress and the dominant figure writing the Bill of Rights, which he had declared were unnecessary. These early Amendments to the Constitution were therefore sparsely confined to those rights which met universal approval and excluded the many proposals of rights which were controversial. The surprising outcome is that the Bill of Rights survives as a bedrock summary of the nation's belief system. There is a tendency to review the actions of all Presidents after they leave office, searching for remarks or behavior which clarifies their official actions while President, and in Madison's case his positions on the dominant Constitutional issues of our Republic. However, that later period of his life was marked by many abrupt reversals of inexplicably contradictory positions that often lessen his stature, and embarrass his earlier achievements. Gouverneur Morris, for example, had the lowest possible opinion of Madison, summarizing him as merely a drunkard. Morris was so contemptuous of Madison that during the War of 1812 that aristocratic main editor of the Constitutional document denounced the whole effort in disgust, mainly devoting his own efforts to making money from the Erie Canal, and later going to France in the Bonaparte era. Other close observers refrained from comment about Madison's drinking habits, and we must presently remain uncertain whether the comment explains Madison's erratic behavior, or whether it was merely an emotional exaggeration by Morris who spent most of his own later life, acting entertainingly at social gatherings.

|

| William Penn |

On the one hand, and on the other; there is scarcely an episode in Madison's life which could not begin with the same words. Madison had tuberculosis and was sent North to go to college at Princeton, where he was much taken with Quaker beliefs in a state still controlled by William Penn's proprietors, but in a College whose campus thoughts were dominated by refugees from the Scottish Enlightenment. He was a good student and stayed an extra year to study Greek under the famous John Witherspoon. He was soon involved in politics, catching the eye of General Washington with his active promotion of the cause of the unpaid Revolutionary Army. Washington soon enlisted the efforts of this neighboring Virginia planter in organizing a new Constitutional Convention, primarily intended to strengthen central government against the intransigent state legislatures, with a particular effort to enable the central government to levy taxes to service war debts. Neither Washington nor Madison knew much about finance; the ideas about leveraging sovereign debt through a central bank evidently came from Robert Morris, who was a close friend of Washington's and in many ways the acting President of the United States during the Revolution. The young Alexander Hamilton bore the same sort of relationship to Morris as the young Madison bore to the General who was a generation older; in both cases, they supplied their own ideas, but mainly applied time, youth and energy to the concepts of their seniors. Hamilton and Madison became fast friends in a great cause, notably collaborating in the writing of the Federalist Papers to promote the new Constitution. Madison was the great scholar of the Roman Republic, a Washington favorite, and displayed a remarkable innate talent for politics in the finest sense, explaining complicated logic and persuading the unpersuaded. Washington nursed a passionate hatred for partisan politics and collaborated with the daily assistance of Madison in defining the traditions of the American presidency. Washington wanted to avoid the appearance of being a King, which was another Washington hatred but was badly in need of some models for an entirely new concept, the executive branch of a deliberately divided government. In one famous episode, Madison wrote Washington's speech, then wrote the reply to Washington by Congress, then wrote Washington's thank-you note back to Congress. Madison was devoted to his work; he only married Dolley Madison when he was 37 years old. Madison would seem to qualify for the category now called nerd.

|

| John Adams |

Hamilton, on the other hand, had many children, legitimate and otherwise, many girlfriends, at least two duels, and flamboyant behavior on the parapets of Yorktown during the final battle. Unlike the aristocratic Madison, he was described by John Adams as the "bastard brat of a Scottish peddler". Although both men seemed to be driven by their short stature, Hamilton never let it get the better of him. Even Martha Washington was amused by his rambunctious behavior, naming her tomcat after him. Both men seemed unduly influenced by their new friends, Hamilton by his rich New York wife's rich friends, and Madison by Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry, the big men on campus so to speak, of the Virginia scene. When Hamilton began to favor banks, bankers and obscure financial wizardry -- and particularly after Madison's hero George Washington took Hamilton's side in the establishment of a central bank-- Madison was ready to be courted by his childhood heroes in Tidewater Virginia, particularly Thomas Jefferson, who always wrote prose as if writing poetry. That's about all we really know about the episode, and there is probably more we don't know, but Madison in an instant became Hamilton's mortal enemy, Jefferson's fast friend, an enemy of the bank, and -- the founder of America's first political party. George Washington never spoke to him, again. It seems possible to suspect that Jefferson was jealous of Washington, although he always was very careful not to confront him directly. When Hamilton persuaded Congress to enact a whiskey tax, Albert Gallatin and other friends of Jefferson's party stirred up the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania, and Washington personally led fifteen hundred Federal troops across the mountains to put down the rebellion. General Alexander Hamilton was at his side. James Madison was somewhere else, probably reading a book. Madison was the sort of person who always knew when his enemies had the votes. He was often lost without the assistance of Gallatin, who somehow knew when the enemy had the better argument.

|

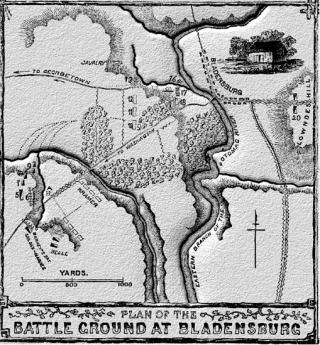

| Bladensburg races |

Eventually, America split between those who sympathized with the French and their land domination of Europe and those who began to seek a repair of the trade relationship with Brittania which ruled the waves. The Adams presidency was ruined by fallout from this international warfare, an embargo was imposed, and both France and England did their bit to make things worse. At one point, it was uncertain whether America would be going to war with France or with England. Eventually, it was with England in the War of 1812. Jefferson and Madison had become successive presidents dedicated to saving money by disarmament, but in spite of our having no navy and nothing but militia for an army, we blithely set about to conquer Canada, with the plan of trading it for trade concessions from the British Empire. Unfortunately, the War was a several-year series of overwhelming defeats for the Madison administration, culminating in the burning of Washington D.C. and the "Bladensburg races" (for the exits), but celebrated as Dolley Madison rescuing the portrait of George Washington, and Francis Scott Key writing the "Star Spangled Banner" about the bombardment of Baltimore. Indian massacres in Michigan and other western defeats complimented the litany of disaster, which was finally ended when Gallatin negotiated the Treaty of Ghent as status quo pro antebellum with the preoccupied British, and then celebrated Andrew Jackson's defeat of the British army at New Orleans, after the Treaty had been signed but before news of it reached home. As Madison's last acts at the end of his term, he promoted Adam Smith economics, the reconstitution of the Bank, a general rearmament campaign -- and then vetoed the bill when it passed. To say that Henry Clay in Congress was embarrassed is to stretch the limits of language. After he left office, Madison became a senior statesman, making all sorts of pronouncements about current events and the true meaning of some Constitutional point involved, quite regularly reversing his positions and encouraging secession by talking about it so much.

|

| Marbury v. Madison |

This sorry tale is too long to present fairly and accurately, while its point can be most simply made by reference to Madison's first involvement as Secretary of State, in the famous Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison . When the departing Adams administration made some last-minute inconsequential appointments, one of them was to Marbury. At the beginning of the Jefferson Presidency, John Marshall was the departing Secretary of State, James Madison the incoming one. The appointment to Marbury was duly made and ratified, its certificate lying on the desk of the Secretary of State. Marshall (outgoing) neglected to send the certificate to Marbury, and Madison (incoming) refused to do so, on the advice of Jefferson the President; none of them ends up looking, adult. Instead of recusing himself, Marshall as Chief Justice further entangled himself in a dispute where he was the referee, by devising the concept that the Supreme Court could declare acts of Congress unconstitutional, and trapping Jefferson into a position where he had to agree with it. All in all, it certainly would seem simpler for Madison to have sent over the certificate. The authors of the three most famous documents in the American icon were inaugurating what a recent biographer Kevin R.C. Gutzman, described as the Presidencies of Chicanery.

James Madison deserves the highest praise for his achievements in three documents: the Virginia Plan, which was the forerunner of the Articles portion of the Constitution, that is to say, the basic structural components of our present government. Secondly, the bulk of the Federalist Papers leading to the Ratification of the Constitution. And third, the Bill of Rights, which he saw no need for, and therefore personally rewrote to be miraculously sparing of language, limited to bedrock essentials, and celestial as a statement of American national purpose.

Madison lived a long life, but it is difficult to find anything in the last forty years which justifies his early promise. Or which could be called a disgrace to it, either, if he had only made a more ordinary beginning.

REFERENCES

| James Madison and the Making of America: Kevin R. C. Gutzman: ISBN-13: 978-0312625009 | Amazon |

First Amendment: Separation of Church and State

Amendment 1 Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

|

| The First Amendment |

Simplified histories of America often declare that other Western Hemisphere colonists mostly came to plunder and exploit; whereas English Protestant colonists came with families to settle, fleeing religious persecution. That's a considerable condensation of events covering three centuries, but it is true that before the Revolutionary War, eleven of the thirteen American colonies approximated the condition of having established religions. Massachusetts and Virginia, the earliest colonies, had by 1776 even reached the point of rebelliousness against their religious establishments. The three Quaker colonies (New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware) were late settlements, in existence less than a century before the Revolution, and still comfortable with the notion they were religious utopias. While differing in intensity all colonials respected the habits of thought and forms of speech, natural to utopians residing in a religious environment.

Once Martin Luther had let the Protestant genii out of its religious bottle, however, revisionist logic was pursued into its many corners. Ultimately, all Protestant questers found themselves confronting -- not religious dogmatism, but it's opposite -- the secularized eighteenth-century enlightenment. Comparatively few colonists were willing to acknowledge doubts openly about miracles and divinity. However, private doubts were sufficiently prevalent among colonial leaders to engender restlessness about the tyrannies and particularly the rigidities of the dominant religions. To this was added discomfort with self-serving political struggles observable among their preachers, and alarm about occasional wars and persecutions over arguably religious doctrines. Arriving quite late in this evolution of thought -- but not too late to experience a few bloody persecutions themselves -- the Quakers sought to purify their Utopia by eliminating preachers from their worship entirely. Thus, the most central and soon the most prosperous of the colonies made it respectable to criticize religious leaders in general for the many troubles it was believed they provoked.

|

| London Yearly Meeting |

|

| Congress Hall |

In all wars, diplomatic arts and religious restraints get set aside as insufficient, if not altogether failures for an episode of utter barbarism. In the Revolution, some Quakers split from pacifism and became Free Quakers, many more drifted into Episcopalianism, never to return to pacifism. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was eventually held in this persisting environment; the previous service in the War counted for something, and the great goal was to strengthen the central government -- for more effective regional defense. A great many leaders were Masons, holding that much can be accomplished by secular leadership, independent of religious reasonings. Neither Washington nor Madison revealed much of their religious positions, although Washington the church attender always declined communion; Franklin and probably Jefferson were at heart deists, believing that God might well exist, but had wound up the universe like a clock to let it run by itself. The New England Calvinist doctrines have since evolved as Unitarianism, which outsiders would say theologically is not greatly different from deism. Physically surrounding the Philadelphia convention was a predominantly Quaker attitude; entirely too often, preachers get you into trouble.

When the first Congress finally met under their new constitution, they immediately confronted over a hundred Constitutional amendments, mostly submitted from the frontier and fomented by Jefferson and Patrick Henry, demanding a bill of rights. The demand within these amendments was overwhelming that the newly-strengthened central government must not intrude into the rights of citizens. Recognizing the power of local community action, states rights must similarly be strengthened. Just where these rights came from was often couched in divine terms for lack of better proof that they were innate, or natural. From a modern perspective, these rights in fact often originated in what theologians call Enthusiasm; the belief that if enough people want something passionately enough, it must have a divine source. The newly minted politicians in the first Congress recognized something had to be done about this uproar. Congress formed a committee to consider matters and appointed as chairman -- James Madison. Obviously, the chief architect of the Constitution would not be thrilled to see his product twisted out of shape by a hundred amendments, but on the other hand, a man from Piedmont Virginia would be careful to placate the likes of Patrick Henry. The ultimate result was the Bill of Rights, and Madison packed considerably more than ten rights into the package, in order to preserve the cadence of the Ten Commandments. The First Amendment, for example, is really six rights, skillfully shaped together to sound more or less like one idea with illustrative examples. Overall freedom of thought comfortably might include freedom of speech (and the press), along with freedom of religion and assembly, and the right to petition for grievances. But what it actually says is that Congress shall not establish a national religion. Since eleven states really had approximated a single established religion, the clear intent was to prohibit a single national religion while tolerating unifications within the various states. Subsequent Supreme Courts have extended the Constitution to apply to the states as well, responding to a growing recognition that religious states had the potential to get so heated as to war with each other. No matter what their doctrines, it seemed wise to deprive organized religions of political power as a firm step toward giving the Constitution itself dominant power over the processes of political selection.

At first however it was pretty clear; one state's brand of religion was not to boss around the religion of another state. Eventually within one state, Virginia for example, the upstate Presbyterian ministers were not to push around the Episcopalian bishops of the Tidewater. Madison and Jefferson saw well enough where political uprisings tended to start in those days, in gathered church meetinghouses. In this way, an Amendment originally promoted to protect religions had evolved into a way to ease them out of political power. The idea of separation of church and state has grown increasingly stronger, to the point where most Americans would agree it defines a viable republic. No doubt, the spectacle of preachers exhorting the same nation in opposite directions during the Civil War, settled what was left of the argument.

For Quakers, the most wrenching, disheartening revelation came when they were themselves in unchallenged local control during the French and Indian War. The purest of motives and the most earnest desire to do the right thing provided no guidance for those in charge of the government when the French and Indians were scalping western settlers and burning their cabins. Yes, the Scotch-Irish settlers of the frontier had unwisely sold liquor and gunpowder to the Indians, and yes, the Quakers of the Eastern part of the state had sought to buffer their own safety from frontier violence by selling more westerly land to combative Celtic immigrant tribes. A similar strategy had worked well enough with the earlier German settlers, but reproachful history was not likely to pacify frontier Scots in the midst of a massacre. The Quaker government was expected to do what all governments are expected to do, protect their people right or wrong. To trace the social contract back to William Penn's friend John Locke was too bland for a religion which prided itself on plain speech. Non-violent pacifism just could not be reconciled with the duties of a government to protect its citizens. The even more comfortably remote Quakers of the London Yearly Meeting then indulged themselves in the luxury of consistent logic; a letter was dispatched to the bewildered Quaker Colonials. They must withdraw from participation in a government which levied war taxes. And they obeyed.

Although the frontier Scots were surely relieved to have non-Quakers assume control of their military duty, the western part of the state has still neither forgotten nor forgiven. In their eyes, Quakers were not fit to be in charge of anything. Quaker wealth, sophistication and education were irrelevant; only Presbyterians are fit to rule. A strong inclination toward pre-destination lurks in that idea. Once more, the attractiveness of clear separation of church and state is reinforced.

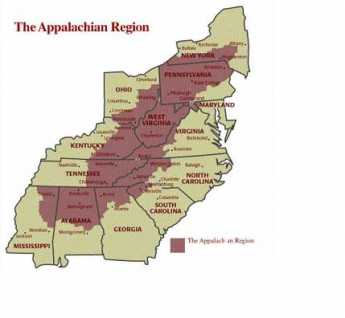

The French and Indian War in fact had turned out fairly well; most of its victories were located on the European side of the Ocean, anyway. But twenty years later the Revolutionary War turned into a reassertion of the British conquest of all of North America, not merely the part to the west of the Appalachian mountains. To Americans, this came in the form of a demand for taxes to help pay off the costs of a war which greatly benefitted them. The Quaker colonies did not fully sympathize with rebellion, but they had once given up control of a territory larger than England rather than pay war taxes, so they were resistant to both sides in the dispute. Many prosperous and educated Quakers solved their dilemma by fleeing to Canada, but the ardent Quaker proposal for dealing with a coercive British government was not at all impractical. John Dickinson, in particular, argued that since the British motives were economic, success was most likely to come from economic counter-pressure, adroitly leveraged by three thousand miles of intervening ocean. That was shrewd and potentially effective. But the Scots-Presbyterian position was simpler and more direct. If you want us to fight your war, you are going to have to fight to win. The Virginia Cavaliers were probably more likely to win a conventional war if put in charge, but the blunt and almost savage frontiersmen were ideally suited for what has come to be called guerrilla warfare. Washington was a leader, French money was welcome and Ben Franklin was a diplomat, but the clarion call to this particular battle was the voice of Patrick Henry. All in all, the issue of established religion was far more complicated than merely the affirmation of a right to free exercise of religious belief. What united all the colonies was a recognition that, using the church, an arm of the government was just as likely to cause trouble as conducting the state as an instrument of church interests. Eventually, considering how religious America was at the time, there was remarkably little resistance to the firm separation of Church and State in its Constitution.

Boston firearms license

This is the process my son went through in October-November 2012 to get a Boston firearms license.

- Call (617) 343-4425 to make an appointment; usually a month's wait.

- On the application appointment date, you go to 1199 Tremont St, Boston MA (Boston Police Headquarters)

Bring:- Birth Certificate

- MA Driver's license showing Boston address

- MA State Police Gun Safety training certificate

- $100 in cash (no credit cards!)

AMENDMENT II A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

|

| Constitution of the United States |

The process at Police Headquarters is straightforward: arrive 15 minutes early to fill in paperwork and be out an hour later after answering simple, obvious questions and getting photographed and fingerprinted.

My son was told that the default is a restriction to Target and Sport; a letter showing a business or personal need for an unrestricted license is required after the initial restricted license is received.

His appointment at the Moon Island outdoor range was set for a week later. (It's an island in the harbor off Quincy.)

The qualifying shoot at the Moon Island outdoor range was easy:

- He got a very helpful lecture from a Police Dept. instructor, covering both shooting and safety

- At the outdoor range:

- 12 rounds at 7 yards: two hands, double action (one hand optional)

- 18 rounds at 15 yards: two hands, single action (hammer to be pulled with the supporting-hand thumb)

He got a 296 out of 300 (two 9's, one 8). He did well because of the 3 private lessons he took at the Mass Firearms School range where he shot two boxes each time using their 0.38 revolver (the equipment provided at the Moon Island range was brand new, much easier to use and more accurate so he was very well prepared). All the other scores were lower than his, one person out of six failed.

He was told his license would take 12 weeks to process; he received his Class A Large Capacity License to Carry Firearms, restricted to target and hunting, 51 days (7 1/2 weeks) after his qualifying shoot.

Second Amendment: The 28th Infantry Division

SINCE the nation was only formed in 1776, and the only memorable war before that was the French and Indian War of 1754, the origin in 1747 of the Pennsylvania 28th Division of Infantry needs a little explaining. The 28th is a National Guard reserve unit, taking its present organizational form 138 years ago. Even counting from that moment makes it the oldest (and third largest) division in the Army, but another 123 years of history stretch back before that.

AMENDMENT II A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

|

| Second Amendment |

A few people remember that Ben Franklin made his first step into politics during King George's War (1744-48), when French and Spanish privateers were suddenly roaming Delaware Bay . The pacifist Quaker government hesitated in confusion, so Franklin stepped forward to call for a volunteer militia. It was paid for with a lottery because the Quaker legislature resisted; there seemingly was no end to Franklin's ingenuity. The unit remained a permanent one, and since then served with distinction in the various conflicts through the Civil War, when it was organized into the National Guard. The volunteer movement it inspired was part of the impetus for the Second Amendment to the Constitution which the National Rifle Association will be glad to explain to you, although historians commonly trace the civilian soldier tradition back to King James and the English Civil War. Franklin was unfailingly patriotic, and never hesitated about military measures when they seemed necessary. He lived long enough so his military sympathies were still a dominant force at the Constitutional Convention, more than forty years later.

Major General Wesley E. Craig Jr., former commander of the Division, was kind enough to address the Right Angle Club about the 28th Division recently. Since the citizen soldiers of the National Guard all have other careers, his daytime job was as an executive for Strawbridge and Clothier. A moment of reflection about the Scottish origin of his own name, connected with a strongly Quaker firm, evokes the two strongest social and ethnic tensions of early Pennsylvania history.