Related Topics

...Ratification, Bill of Rights and Other Amendments

The 1787 Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights. Few except Madison himself were opposed to adding one, but many other delegates would have failed election without promising it. Negotiations at the Convention had proved so excitingly innovative that time ran out before the Convention had to adjourn with only a promise of a Bill of Rights, first thing.

...Authorship of the Constitution

There were seventy invited delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Fifty-five attended the sessions, and thirty-nine signed it. We believe the main contributions were made by seven or eight men. But you can never tell, for certain.

James Madison

|

| James Madison |

JAMES Madison was born (1751) a rich Virginia planter, was a major factor in the composition of the U.S. Constitution, became secretary of State and President of the United States for two terms (1812-20), and died (1836) impoverished at the age of 85. Because the Constitutional Convention was conducted in secrecy, we cannot be entirely certain which parts to attribute to him, or even what his personal position had been on many issues. He was Chairman of the Committee of the First Congress and the dominant figure writing the Bill of Rights, which he had declared were unnecessary. These early Amendments to the Constitution were therefore sparsely confined to those rights which met universal approval and excluded the many proposals of rights which were controversial. The surprising outcome is that the Bill of Rights survives as a bedrock summary of the nation's belief system. There is a tendency to review the actions of all Presidents after they leave office, searching for remarks or behavior which clarifies their official actions while President, and in Madison's case his positions on the dominant Constitutional issues of our Republic. However, that later period of his life was marked by many abrupt reversals of inexplicably contradictory positions that often lessen his stature, and embarrass his earlier achievements. Gouverneur Morris, for example, had the lowest possible opinion of Madison, summarizing him as merely a drunkard. Morris was so contemptuous of Madison that during the War of 1812 that aristocratic main editor of the Constitutional document denounced the whole effort in disgust, mainly devoting his own efforts to making money from the Erie Canal, and later going to France in the Bonaparte era. Other close observers refrained from comment about Madison's drinking habits, and we must presently remain uncertain whether the comment explains Madison's erratic behavior, or whether it was merely an emotional exaggeration by Morris who spent most of his own later life, acting entertainingly at social gatherings.

|

| William Penn |

On the one hand, and on the other; there is scarcely an episode in Madison's life which could not begin with the same words. Madison had tuberculosis and was sent North to go to college at Princeton, where he was much taken with Quaker beliefs in a state still controlled by William Penn's proprietors, but in a College whose campus thoughts were dominated by refugees from the Scottish Enlightenment. He was a good student and stayed an extra year to study Greek under the famous John Witherspoon. He was soon involved in politics, catching the eye of General Washington with his active promotion of the cause of the unpaid Revolutionary Army. Washington soon enlisted the efforts of this neighboring Virginia planter in organizing a new Constitutional Convention, primarily intended to strengthen central government against the intransigent state legislatures, with a particular effort to enable the central government to levy taxes to service war debts. Neither Washington nor Madison knew much about finance; the ideas about leveraging sovereign debt through a central bank evidently came from Robert Morris, who was a close friend of Washington's and in many ways the acting President of the United States during the Revolution. The young Alexander Hamilton bore the same sort of relationship to Morris as the young Madison bore to the General who was a generation older; in both cases, they supplied their own ideas, but mainly applied time, youth and energy to the concepts of their seniors. Hamilton and Madison became fast friends in a great cause, notably collaborating in the writing of the Federalist Papers to promote the new Constitution. Madison was the great scholar of the Roman Republic, a Washington favorite, and displayed a remarkable innate talent for politics in the finest sense, explaining complicated logic and persuading the unpersuaded. Washington nursed a passionate hatred for partisan politics and collaborated with the daily assistance of Madison in defining the traditions of the American presidency. Washington wanted to avoid the appearance of being a King, which was another Washington hatred but was badly in need of some models for an entirely new concept, the executive branch of a deliberately divided government. In one famous episode, Madison wrote Washington's speech, then wrote the reply to Washington by Congress, then wrote Washington's thank-you note back to Congress. Madison was devoted to his work; he only married Dolley Madison when he was 37 years old. Madison would seem to qualify for the category now called nerd.

|

| John Adams |

Hamilton, on the other hand, had many children, legitimate and otherwise, many girlfriends, at least two duels, and flamboyant behavior on the parapets of Yorktown during the final battle. Unlike the aristocratic Madison, he was described by John Adams as the "bastard brat of a Scottish peddler". Although both men seemed to be driven by their short stature, Hamilton never let it get the better of him. Even Martha Washington was amused by his rambunctious behavior, naming her tomcat after him. Both men seemed unduly influenced by their new friends, Hamilton by his rich New York wife's rich friends, and Madison by Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry, the big men on campus so to speak, of the Virginia scene. When Hamilton began to favor banks, bankers and obscure financial wizardry -- and particularly after Madison's hero George Washington took Hamilton's side in the establishment of a central bank-- Madison was ready to be courted by his childhood heroes in Tidewater Virginia, particularly Thomas Jefferson, who always wrote prose as if writing poetry. That's about all we really know about the episode, and there is probably more we don't know, but Madison in an instant became Hamilton's mortal enemy, Jefferson's fast friend, an enemy of the bank, and -- the founder of America's first political party. George Washington never spoke to him, again. It seems possible to suspect that Jefferson was jealous of Washington, although he always was very careful not to confront him directly. When Hamilton persuaded Congress to enact a whiskey tax, Albert Gallatin and other friends of Jefferson's party stirred up the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania, and Washington personally led fifteen hundred Federal troops across the mountains to put down the rebellion. General Alexander Hamilton was at his side. James Madison was somewhere else, probably reading a book. Madison was the sort of person who always knew when his enemies had the votes. He was often lost without the assistance of Gallatin, who somehow knew when the enemy had the better argument.

|

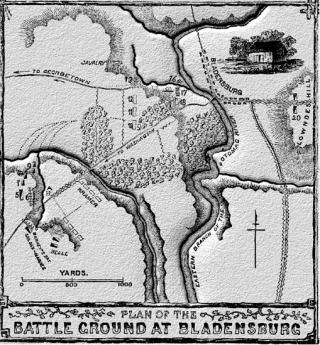

| Bladensburg races |

Eventually, America split between those who sympathized with the French and their land domination of Europe and those who began to seek a repair of the trade relationship with Brittania which ruled the waves. The Adams presidency was ruined by fallout from this international warfare, an embargo was imposed, and both France and England did their bit to make things worse. At one point, it was uncertain whether America would be going to war with France or with England. Eventually, it was with England in the War of 1812. Jefferson and Madison had become successive presidents dedicated to saving money by disarmament, but in spite of our having no navy and nothing but militia for an army, we blithely set about to conquer Canada, with the plan of trading it for trade concessions from the British Empire. Unfortunately, the War was a several-year series of overwhelming defeats for the Madison administration, culminating in the burning of Washington D.C. and the "Bladensburg races" (for the exits), but celebrated as Dolley Madison rescuing the portrait of George Washington, and Francis Scott Key writing the "Star Spangled Banner" about the bombardment of Baltimore. Indian massacres in Michigan and other western defeats complimented the litany of disaster, which was finally ended when Gallatin negotiated the Treaty of Ghent as status quo pro antebellum with the preoccupied British, and then celebrated Andrew Jackson's defeat of the British army at New Orleans, after the Treaty had been signed but before news of it reached home. As Madison's last acts at the end of his term, he promoted Adam Smith economics, the reconstitution of the Bank, a general rearmament campaign -- and then vetoed the bill when it passed. To say that Henry Clay in Congress was embarrassed is to stretch the limits of language. After he left office, Madison became a senior statesman, making all sorts of pronouncements about current events and the true meaning of some Constitutional point involved, quite regularly reversing his positions and encouraging secession by talking about it so much.

|

| Marbury v. Madison |

This sorry tale is too long to present fairly and accurately, while its point can be most simply made by reference to Madison's first involvement as Secretary of State, in the famous Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison . When the departing Adams administration made some last-minute inconsequential appointments, one of them was to Marbury. At the beginning of the Jefferson Presidency, John Marshall was the departing Secretary of State, James Madison the incoming one. The appointment to Marbury was duly made and ratified, its certificate lying on the desk of the Secretary of State. Marshall (outgoing) neglected to send the certificate to Marbury, and Madison (incoming) refused to do so, on the advice of Jefferson the President; none of them ends up looking, adult. Instead of recusing himself, Marshall as Chief Justice further entangled himself in a dispute where he was the referee, by devising the concept that the Supreme Court could declare acts of Congress unconstitutional, and trapping Jefferson into a position where he had to agree with it. All in all, it certainly would seem simpler for Madison to have sent over the certificate. The authors of the three most famous documents in the American icon were inaugurating what a recent biographer Kevin R.C. Gutzman, described as the Presidencies of Chicanery.

James Madison deserves the highest praise for his achievements in three documents: the Virginia Plan, which was the forerunner of the Articles portion of the Constitution, that is to say, the basic structural components of our present government. Secondly, the bulk of the Federalist Papers leading to the Ratification of the Constitution. And third, the Bill of Rights, which he saw no need for, and therefore personally rewrote to be miraculously sparing of language, limited to bedrock essentials, and celestial as a statement of American national purpose.

Madison lived a long life, but it is difficult to find anything in the last forty years which justifies his early promise. Or which could be called a disgrace to it, either, if he had only made a more ordinary beginning.

REFERENCES

| James Madison and the Making of America: Kevin R. C. Gutzman: ISBN-13: 978-0312625009 | Amazon |

Originally published: Tuesday, July 03, 2012; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 22, 2019