2 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Nature Preservation

Nature preservation and nature destruction are different parts of an eternal process.

John Bartram's Garden

|

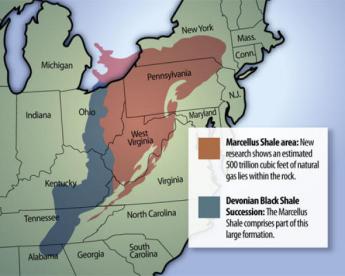

| Bartram Gardens |

It's worth a visit to Bartram's Gardens, if only for the astonishment of finding a very large farm and stone Quaker farmhouse within a few blocks of our largest medical center, a stone's throw from the biggest oil refinery on the upper East Coast. And located on the edge of a neighborhood that is, well, past its prime. The trees on the farm are centuries old, so walking around the grounds imparts the feeling of being hundreds of miles from civilization when in fact you are only a hundred yards away from streets that are very urban, indeed. When you turn in certain directions, an occasional skyscraper peeps over treetops, and down the meadows, at the farm's dock on the leafy-banked Schuylkill, you can see oil storage tanks across the river, just a long shot with a 2-iron away. Look upward, to see the upper half of shining towers of Center City.

The farm property as it now stands dates back to 1728, but the site marks the earliest beginnings of the city, nearly a hundred years earlier. The river curves around this hill then snake on down to Delaware through flatlands which were originally swamps ("wetlands", as they say). The hill is as far downriver into malaria territory as the Indians were willing to go, so the Dutch traders had to sail upriver and dock there in order to take thirty or forty thousand fur pelts back to Holland each year. One thing or another has been dumped on the swamps for three hundred years, and the oil companies found it a cheap place to buy enough land for their refineries, close to four or five railroads near Bartram's place, and with access to the high seas. Right now, most of the oil comes from Nigeria, emptying two or so supertankers a week. There has to be enough storage capacity to take care of delays caused by bad weather on the Atlantic, and there has to be access to railroads and highways to carry the finished product away. The rest of a refinery is just thousands of miles of metal pipes, gleaming in the sun.

Sun Oil is trying to be a good neighbor, turning more and more of the area over to nature preserve, as chemical engineers have learned how to work in a smaller space with fewer employees. The banks of the lower Schuylkill are now mostly grown to shrubs and trees, concealing from boat travelers the rather extensive dumps of old auto tires and similar refuse. It's a placid winding trip, increasingly coming to resemble what the Dutch traders once encountered. Especially in May, when the Palomino or Empress trees are in purple bloom. It seems the Chinese packed their porcelains in dried Palomino seed pods, and the discards have grown up to quite a nice display. Logan Square is filled with such trees, quite artfully pruned and maintained; just imagine several miles of the river lined with them, and you can see why the Tourist Bureau is excited about the potential. If you have been to San Antonio you know the potential of an urban river ride, which in this case might go all the way up to the Art Museum. Given enough public response, you can envision two or three-day barge rides from New Castle, Delaware to Pennsbury, with side trips up past Bartram's to the Waterworks. Right now, trips are comparatively limited by the tides, with a few trips a year down from Bartram's to the refineries, and a few more up to the river to the Art Museum. They use floating docks, and permanent docks will need to be built.

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

Originally, the crude oil came from upstate Pennsylvania, near Bradford, and was the main source of the dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Baltimore and New York were also the beginnings of transcontinental railroads, but their freight cars came back empty. The upstate Pennsylvania oil gave the PRR a dominant edge by supplying cargo for two-way revenue.

When George Washington had to retreat from the Battle of Brandywine, the armies had to cross the wetlands, and the river, to get to Philadelphia. Washington got there first and burned the boats after his army got across. He knew, but the British probably did not fully realize, that the first place to ford the Schuylkill was at Norristown. When the British finally got that far, Washington was waiting for them, but a fall hurricane came along and soaked everybody's gunpowder before there could be much of a battle. Unfortunately, Mad Anthony Wayne was unprepared for a nighttime bayonet charge, and there was still quite a slaughter.

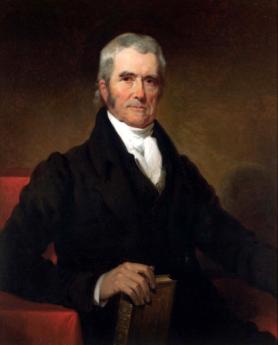

You can't wander around John Bartram's house and gardens without getting the impression of considerable wealth. Bartram was interested in botany, becoming the most eminent authority on plants of the Western hemisphere, a very close friend of Benjamin Franklin, and probably the main force behind the creation of the American Philosophical Society. But although Bartram was a hobbyist, he was a shrewd businessman, selling curiosity plants to Europeans, and commercially improved fruits and vegetables to local farmers. There are still some Bartrams around Philadelphia, with a strong Quaker air about them. Around 1850 the place was sold to a zillionaire railroad magnate named Eastwick, who fixed up the place in the high style he learned building the railroads of Russia for the Tsar. The mansion has been torn down, but the stone farmhouse, stone barn, stone sheds, stone outbuildings, stone everything -- endures, like many of the curiosity trees and bushes. Well worth a visit.

Morris Arboretum

The former estate of John and Lydia Morris is run as a public arboretum, one of the finest in North America.

|

Morris is the commonest Philadelphia name in the Social Register, derived largely from two unrelated Colonial families. In addition to their city mansions, both families had country estates. The country estate once belonging to the Revolutionary banker Robert Morris was Lemon Hill, just next to the Art Museum, where Fairmount Park begins. But way up at the far end of the Park, beyond Chestnut Hill, was Compton, the summer house of John and his sister Lydia Morris. This Morris family had made a fortune in iron and steel manufacture and were firmly Quaker. Both John Morris and his sister were interested in botany and had evidently decided to leave Compton to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a public arboretum. John died first, leaving final decisions to Lydia. As the story is now related, Lydia had a heated discussion with Fiske Kimball, at the end of which the Art Museum deal was off. She turned to her neighbor Thomas Sovereign Gates for advice, and the arboretum is now spoken of as the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania. It is also the official arboretum of the State of Pennsylvania. To be precise, the Morris Arboretum is a free-standing trust administered by the University, with the effect that five trustees provide legal assurance that the property will be managed in a way the Morrises would have wished. In Quaker parlance, Lydia possessed "steely meekness."

A public arboretum is sort of an outdoor museum of trees, bushes, and flowers, with an indirect consequence that many museum visitors take home ideas for their own gardens. Local commercial nurseries tend to learn here what is popular and what grows well in the region, so there emerges an informal collective vision of what is fashionable, scalable, and growable, with the many gardeners in the region interacting in a huge botanical conversation. The Morris Arboretum and two or three others like it go a step further. There are two regions of the world, Anatolia and China-Korea-Japan, with much the same latitude and climate as the East Coast of America. Expeditions have gone back and forth between these regions for a century, transporting novel and particularly hardy or disease-resistant specimens. An especially useful feature is that Japan and parts of Korea were never covered with glaciers, hence have many species found nowhere else in the temperate zone. Hybrids are developed among similar species found on different continents, and variants are found which particularly attract or repel the insects characteristic of each region. The Morris Arboretum is thus at the center of a worldwide mixture of horticulture and stylish outdoor fashion, affecting millions of home gardeners who may never have heard of the place.

Geckos: Academy of Natural Sciences brings Mini Dinosaurs

|

| Gecko |

FRIENDS who spent time in Vietnam have a lasting memory of lizards stuck to the ceiling, catching flies with their tongues. Those animals are named geckos, one of the oldest and probably most varied families of reptiles, but confined to the Southern hemisphere. Fossils have been found containing geckos from fifty million years ago, so they were here before the big dinosaurs were wiped out, when the Yucatan was probably struck by an asteroid.

|

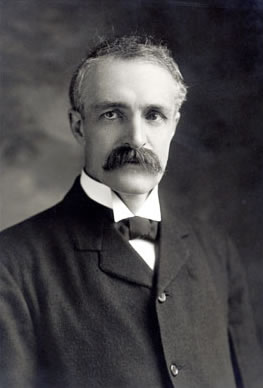

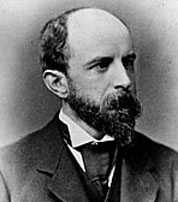

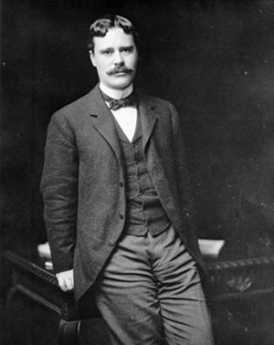

| Anthony Geneva |

There was a time when Africa, India, South America and Antarctica were united in one monstrously big continent, and the many varieties of gecko are scattered over the land masses which originally made that up. At least this is the way Anthony Geneva explains it to visitors to the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th and Ben Franklin Parkway. There are no geckos to be found naturally in Philadelphia. Philadelphians hardly need reminding that the first dinosaur bones, ever, were discovered in Haddonfield NJ, and were soon taken to the Academy for permanent display. Ever since that time, the Academy's collection of dinosaurs has expanded, and are the things with the most impact on school-age visitors. The Academy is getting ready to celebrate its 200th anniversary in a few years, however, and contains much more than dinosaur bones, including extensive research facilities with world-famous scientists at work in them. In any event, the dinosaur image is a clear metaphor for the present display of little reptiles that look like dinosaurs, whatever the DNA trail may be. The main exhibition area is currently filled with dozens of glass display cases containing live geckos, and the little rascals are so good at camouflage that you have to hunt carefully for them before they suddenly seem to emerge from the shadows. There are white ones, black ones, bright green and bright orange ones, speckled in all sorts of weird patterns. They make sounds resembling bird songs, and the term gecko is a native word referring to such sounds. The Academy displays these gecko-noises for visitors who are invited to push twenty or so buttons. Geckos move, but suddenly, and probably for some predatory purpose. If you are really into geckos, you focus on their feet.

|

| Gecko |

The variety of toe and foot shape is almost infinite and seems more so if you have a magnifying lens. The foot pads terminate in different kinds of extremely fine hairs, and that's their big secret. Those hairs are so fine the molecules of the foot and the molecules of the wall or ceiling attract each other magnetically. Since no energy is expended in the adherence, the gecko can remain attached to a wall or ceiling indefinitely, even after the gecko dies. But, by raising the angle of contact to thirty degrees, the foot detaches, and the little rascals can scoot along very rapidly, upside down. At present, there is a great deal of commercial and maybe military interest in clarifying the secrets of this adhesion. To be industrially useful, the footpad size would have to scale up to much larger dimensions, but just imagine gluing together the vessel ruptures and aneurysms inside the brain as we now do in a cumbersome manner with chicken-wire stents, just one example that quickly occurs to a visitor. If these little fellows figured out how to make these reversible adhesives fifty million years ago, our scientists ought to be able to imitate them.

Drop around to visit the Academy. It's filled with amazing things like this.

Delaware Bay Before the White Man Came

Captain John Smith of Virginia, sometime friend of Pocahontas, wrote a letter to Captain Henry Hudson that he understood there was a big gap in the continent to the North of the Virginia Capes, and maybe this was the Northwest Passage to China. Hudson set out to look for it.

|

| Hudson |

Smith's misjudgment now seems like a credible story if you take the ferry from Lewes, Delaware to Cape May, New Jersey. You are out of sight of land for half an hour on that trip, and it's a hundred miles of blue salt water to Philadelphia if you decided to go in that direction. In fact, the bay widens out to double the width or more, just inside the capes, and you can see how an explorer in a little sailboat might believe there was clear sailing to the Indies if you went that way. But as a matter of fact, Hudson encountered so much "shoal" that he ran aground repeatedly trying to sail into the bay, and soon gave up. He encountered a swamp, not an ocean passage. The Hudson River, and later Hudson's Bay, seemed like better bets.

What Hudson had encountered was one of the largest gaps in the chain of Atlantic barrier islands, formed by the crumbling of the Allegheny Mountains into the sea, and then washed up as beach islands by the ocean currents. At various points, the low flat sandy islands became re-attached to the mainland as the intervening bay silted up, and that's why the islands of New Jersey and Delaware seem like part of the mainland. And that's what would have happened to the whole Delaware Bay if it hadn't been ditched and dredged, and wave action diverted with jetties. The swamp was a great place to breed insects, so fish were abundant, and that brought birds in vast numbers. Two stories illustrate.

|

| Horseshoe Crabs |

Once a year, a zillion ugly Horseshoe Crabs crawl out of the sea onto the Lewes beaches, and lay a million zillion eggs in the sand. Almost to the moment, a swarm of South American birds swoops out of the skies to eat the eggs. Those birds started flying months earlier from thousands of miles away, but their timing with regard to Delaware crab eggs is perfect, so this evolutionary semi-miracle must have been going on for many centuries.

|

| Cape May |

Now, coming from the other direction, every hour each fall it is possible to see a hawk or two flies south to Cape May, then sort of disappearing in the woods. And then, at some unknown signal, tens of thousands of hawks rise from the bushes and travel together on the thirty-mile passage over the bay and then go on South. Cape May has lots of migratory birds and bird watchers, and it also has Cape May "diamonds", which are funny little stones washed up at the tip of Cape May Point.

In the spring, vast schools of successive species of fish migrate up the Delaware Bay to spawn in the reeds along the shoreline, but as each school encounters the point where the salt water turns fresh, they stop dead. They mill around at this point for several weeks adjusting to the change of water and then go on about their business. While they are there, it is possible for amateurs to catch amazing amounts of fish, if you know the best time, and if you know where the salinity changes. Since heavy or light rainfall can shift the salinity barrier fifty miles, you have to own your own boat if you want to enjoy this phenomenon, since the rental boats are all spoken for months in advance. Fishermen don't like to tell you about such things; patients of mine who literally owed me their lives have refused to say where I might find the fish this year.

Over on the New Jersey side of the bay, oysters like to grow, although something has just about wiped them out in recent decades. There is a town called Bivalve, which is worth a visit just to see the towering piles of oyster shells left over from last century. For miles around, the roads are actually paved with ground-up oyster shells. Up north around Salem, the shad used to run by the millions until the warm water emerging from the Salem (nuclear) power plant attracted them into the intake pipes and action was taken to abate the nuisance. The Salem Country Cub is one of the few places where planked shad can be obtained in season. The system is to split the fish open and nail it to a board, which is then placed in the big open fireplace to cook, and sizzle, and smell just wonderful good. On the other hand, if you want to buy shad in season (March-May) and cook it at home, the place to get it is in Bridgeton.

At the far northern end, at Trenton, the real Delaware River flows into the bay. The area has long since been dredged, but at one time the "falls" at Trenton were notable. Even today, if you travel upriver almost to Lambertville, you will see the river drop over several small ledges. Actually, rapids would probably be a better descriptive term, since Delaware picks up quite a strong current coming down from the Lehigh Valley. In seasons of heavy rainfall, the falls can be completely "drowned".

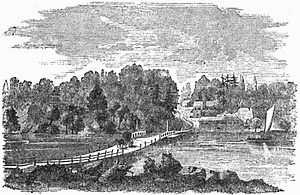

And down at Philadelphia where we live, the Schuylkill joined Delaware, forming the largest swamp of all at the river junction, a place once famous for its enormous swarms of swans. The Dutch discovered a high point of land at what is now called Gray's Ferry and made it into a trading place for beaver skins from the local Indians. There seems no reason to doubt the report that they took away thirty thousand beaver skins a year from this trading post, now the University of Pennsylvania.

An English sailing vessel was once blown to the East side of Delaware at what would now be Walnut Street in Philadelphia, and it was recorded in the ship's log that it was scraped by overhanging tree limbs. The high ground at that point seemed like a favorable place to situate a city because the water was deep enough for ocean vessels. They had stumbled on one of the relatively few places in the whole bay that was both defensible and navigable, where the game was abundant, and fishing was good. The rest is history.

River City

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

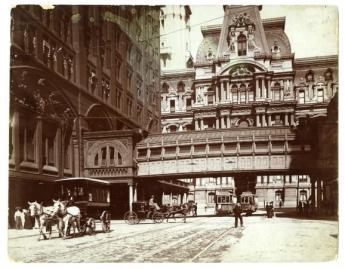

Dock Street

The Corinthos Disaster

Fire, huge fire. The Corinthos disaster of January 30, 1975, was the biggest fire in Philadelphia history, and one hopes the biggest forevermore. Its immensity has possibly lessened attention for some associated issues which are nevertheless quite important, too. Like the issue of punitive damages in a lawsuit, or the need to balance environmental damage with a national need for energy independence. And the changing ways that law firms charge their clients. We hope the relatives of the victims will not be offended if the tragedy is used to illustrate these other important issues. On that cold winter day, two big tanker ships were tied up alongside the opposite banks of the Delaware River at Marcus Hook. The Corinthos was a 754-foot tanker with a capacity of 400,000 barrels of crude oil, tied up on the Pennsylvania side at the British Petroleum dock with perhaps 300,000 barrels still in its tanks at the time of the disaster. At the same time, the 660-foot tanker Edgar M. Queen

with roughly 250,000 barrels of specialty chemicals in its hold, let go its moorings to the Monsanto Chemical dock directly across the river in New Jersey, intending to turn around and head upstream to discharge the rest of its cargo at the Mantua Creek Terminal near Paulsboro. Curiously, a tanker is more likely to explode when it is half empty because there is more opportunity for mixing oxygen with the combustible liquid sloshing around. A tug stood by to assist the turn, but the master of the Queeny felt there was ample room to make the turn under her own power. With no one paying particular attention to this routine maneuver, the Queeny seemed (to only casual observers) to head directly across the river, ramming straight into the side of the Corinthos. Actually, the Queeny had engaged in a number of backing and filling maneuvers, and the sailors aboard were appalled that it seemed to lack enough backing power to stop its headlong lunge at the Corinthos. There was an almost immediate explosion on the Corinthos, and luckily the Queeny broke free with only its bow badly damaged. Otherwise, the fire might have been twice as large as it proved to be with only the Corinthos burning. The explosion and fire killed twenty-five sailors and dockworkers, burned for days, devastated the neighborhood and occupied the efforts of three dozen fire companies. A graphic account of the fire and fire fighting was written by none other than Curt Weldon who was later to become Congressman from the district, but was then a volunteer fireman active in the Corinthos tragedy. There were surprising water shortages in this fire on the river because the falling tides would take the water's edge too far away from the suction devices for the fire hoses on the shore. The tide would also rise above a gash in the side of the burning ship, floating water in and then oil up to the point where it would flow out of the ship onto the surface of the river. Oil floated two miles upstream from the burning ship and ignited a U.S. Navy destroyer which was tied up at that point. Observers in airplanes estimated the oil spill was eventually fifty miles long. All of these factors played a role in the decision whether to try to put the fire out at the dock or let it burn out; experts continue to argue which would have been better. There were always dangers the burning ship would break loose and float in unexpected directions, that the oil slick would ignite for its full length, and that storage tanks on shore would be ignited. The initial explosion had blown huge pieces of iron half a mile away, and the ground near the ship was littered with charred, dismembered pieces of flesh from the victims. , Of course, there was a big lawsuit. When a ship is tied up at a dock it certainly feels aggrieved when another ship crosses a river and rams it. The time-honored principle of admiralty law holds that the owner of an offending ship is not liable for damages greater than the salvage value of its own hulk, which in this case might have been about $3 million. The underlying assumption is that the owner has no way of knowing what is going on thousands of miles away, no control over it, no power to respond in a useful way. Enter Richard Palmer, counsel for the Corinthos. Palmer was aware that the National Transportation Safety Board collects information about ship maintenance inspections in order to share useful information for the benefit of everyone. His inquiry revealed that the inspections of the Queeny for four years before the crash had repeatedly demonstrated that the stern engine had a damaged turbine, and was only able to drive the ship at 50% of its rated power. Why this turbine had not been repaired was now irrelevant; the owners of the ship did have relevant information and had failed to act in a timely safe fashion. The limitation of liability to the salvage value of the hulk now no longer applied if the negligence was judged relevant. The defendants, the owners of the Queeny, decided to settle. While the size of the settlement is a secret of the court, it is fair to guess that it approached the full value of the suit, which was $11 million. Mr. Palmer, by using his experience to surmise that maintenance records might be available at the Transportation Agency, and recognizing that the awareness of the owner might switch the basis for the compensation award from hulk value (of the defendant's ship) to the extent of the damage (to the plaintiff's ship), probably tripled the damage settlement. Reflections on the extraordinary benefit to the client from a comparatively short period of work by the lawyer leads to a discussion about the proper basis for lawyers fees. Senior lawyers feel that the computer has revolutionized lawyer billing practices, and not for the better. Because it is now possible to produce itemized billing which summarizes conversations of less than a minute in duration, services for the settlement of estates can be many pages long, mostly for rather routine business. Matrimonial lawyers are entitled to charge for hours of listening to inconsequential recriminations; lawyers can bill for hours of time spent reading documents into a recording machine, or sitting wordlessly at depositions. Since the time expended can now be flawlessly measured and recorded on computers, there is little room for a client to remonstrate about their fairness. Discomfort about this system underlies much sympathy for billing for contingent fees, where the lawyer is gambling all of his expenses and effort against a generous proportion of the award if he wins the case, nothing at all if he loses. This latter system, customary in slip and fall cases and justified as permitting the poor client to have proper representation, undoubtedly promotes questionable class action suits and often leads to accepting personal liability suits which should be rejected for lack of merit. The thinking underlying personal injury firms is widely said to be: most insurance companies will settle for modest awards in cases without merit because the defense costs would be no less than that amount, and occasionally a personal liability case gets lucky and extracts a huge award. Listen to one old-time lawyer describe how legal billing used to be. After the case was over, the lawyer and the client sat down to a discussion of what was involved in the legal work, and what it accomplished for the client. A winning case has more evident value than a losing one, provided the lawyer can effectively describe the professional skills that helped bring it about. The whole discussion is aimed at having both parties leave the discussion satisfied. To the extent that both parties actually are satisfied with the value of the services, the esteem and reputation of the legal profession are enhanced. And the lawyer is a happy and contented member of a grateful community. If he can occasionally claim a staggering fee for a brief but brilliant performance, as in the case of the explosive fire on the Corinthos -- well, more power to him. It does not take much familiarity with oil refineries to make you realize that cargoes of crude oil are a very dangerous business. We are accustomed to hearing jeers at those who protest, "Not in my backyard", and we deplore those who would jeopardize our national security to protect a few fish and trees in the neighborhood of potential oil spills. Since we do have to import oil and we do therefore have to jeopardize a few selected neighborhoods to accomplish this vital service, the opponents are sadly destined to lose their protests. But that doesn't mean their concerns are trivial. The shipping and refining of oil are dangerous. We just have to live with it and be ready to pay for its associated costs. Windmill Electricity

The Right Angle Club was recently edified at lunch about wind-power generated electricity, by Craig Poff of Iberdrola Renewables, the largest producer of renewable-source electricity in the world. Iberdrola is a Spanish firm, headquartered in Bilboa where they have Basques, near where the Spanish Armada once started its ill-fated journey to battle Sir Francis Drake. Furthermore, it's near where there are caves with wall paintings several thousand years old. Craig is pure American, however, with a background in real estate sales. That isn't as remote a connection as it may sound, because it takes several years and a lot of salesmanships to assemble the leases necessary to create a windmill farm. We've all seen photographs of these silvery towers, with what looks like aluminum propellers glinting in the sun. They are actually made out of fiberglass in much the same way boats are made, and quite often both are made in the Trenton region. So to speak, two hollow clamshells are held together with masking tape to form a propeller blade. Eventually, it revolves slowly, slowly in the wind, starting around 15 miles per hour, and getting turned off when the wind gets so fast it's dangerous. The blades modify their pitch at different speeds, and the entire contraption rotates to meet the wind. Sometimes one windmill will "steal" the wind from its neighbor, so the middle ones get turned down or turned off. There are local "met masts" to measure the wind and its direction and respond with appropriate directions via computers. There are also regional computer centers, and finally, electric power distribution is controlled by computers in Bilbao. Electricity can't be stored very well, so sometimes a perfectly good wind must be ignored when electricity isn't needed. Scientists are working on big batteries, and also on storing energy by pumping water uphill into storage reservoirs or compressing air into caves. Storing wasted electricity is a major issue, and high hopes are held out for innovation in batteries.

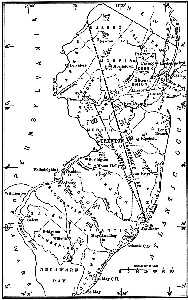

A typical tower is about 123 meters high, with a wingspan of about 300 feet; the towers are separated by roughly 1500 feet, but by much more when they are downwind. It's easy to see how negotiations with local farmers can be difficult, requiring months of public relations in a new community. Sometimes they encounter someone like Senator Ted Kennedy, who just plain dislikes how windmills look. Negotiations have to be conducted to obtain access roads to the wind farm, and access to the power transmission grid. Negotiations have to be conducted both before and after construction to satisfy game commissions who worry about the birds and the bats. As it works out, a farmer gets about $7000 a year to lease out his land, but windier areas are more prized, so jealous bargaining abounds. It's probably no wonder only 2% of electric power is presently generated this way, even though Pennsylvania law requires the power companies to reach 18% by 2020. Requires? What's the reasoning behind that? At present, the windmill nearest to Philadelphia is in Pottsville. It's nice this electricity gets generated by a source so clean, which also can't be shut off by the Iranians. But awkwardly it's expensive to make electricity this way, particularly if you include the subsidies it enjoys. Yes, yes, it's true that lots of things are receiving dubious subsidies, and some of them are competitors to wind power. But the unwillingness of wind power advocates to acknowledge the relative costs of their product suggests to any skeptic that relative costs must be extremely high, indeed. Yes, it's clean, but it's expensive and needs a subsidy. Industries that consume large amounts of power have been offered power purchase agreements that constitute a hedge against future cost volatility for many years in the future. That's both a hedge against rising costs and a promise of reliability; some businesses will pay for that. The competitive economics are that the initial cost of wind power is quite high, but future maintenance costs are quite low. More typically, most household consumers feel they have a right to know more precisely what the competitive prices really are, absent loss leaders, subsidies and hype. When we know that for sure, we consumers will decide whether a somewhat cleaner environment is worth the price. The investors in this technology must gamble they can persuade us that it is, and one can be fairly certain competitive energy producers will seek to persuade us that it isn't. What the farmers who lease their land think, also matters. But the farmers will mostly matter in the legislature voting on clean air mandates, where city dwellers tend to lose their influence. You can sort of see how the legislators think: the farmers know how much they have been offered for the land leases, but the city dwellers can only guess at how clean the environment will get, and how much the electric costs will rise. New Jersey Ponders a Rising Sea Level

A certain gentleman in a professional position to dominate conversations about rising sea levels, is afraid of being sued and requests his name be withheld from the following. Let's just call it hearsay, suitable only for conversational banter. If the icecap now sitting atop Greenland should melt, it can rather easily be calculated that sea level would rise to the point where the Delaware River would be 83 feet deep. The Army Corps of Engineers would then probably have more urgent matters to attend to, but at least they would no longer have to cope with deepening the channel to 40 feet. If the Antarctic ice cap should then melt on top of it, the sea level would rise an additional 220 feet, resulting in a Delaware River 300 feet deep. There might be some dry real estate on top of Blue Mountain, but not much else on the Atlantic seaboard would be dry, so there would likely be the additional problem of keeping other people from climbing up to sit in your perch. Perhaps the Hawks would bring you something to eat. A more immediate issue relates to the barrier islands. It is thought the crumbling of mountains into the sea accounts for the sandy beaches of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts; the more recent mountains along the West coast have not progressed to the point of piling up enough sand to start the process. The cycle of barrier islands is as follows. Barrier islands, if left undisturbed, will gradually migrate toward the land mass behind them, filling up the intervening bay, and eventually adding to the mainland. But that's not the end of the cycle, because the continuous wave and tidal action will generate a new barrier island further out to sea. When the new island reaches a critical equilibrium with the waves and storms, it begins the cycle of deterioration all over again. Presumably, the sandy lowlands of southern New Jersey, the Delmarva Peninsula, and most of Florida are the result of many cycles of barrier islands adding themselves to the mainland. Presumably, the process will run out of sand someday, but not soon enough to worry about. When affluent people build showplaces on the barrier islands, a great deal of concrete is laid on the island surface for roadways and parking lots, as well as jetties and other desperate efforts to prevent erosion from destroying the beaches, beachfront property, and real estate values. This process is much more active and rapid than most sunbathers seem to imagine. There are channel markers and monuments of the 18th century that are a mile or more out to sea in the 21st century. Almost a mile of beachfront has disappeared at Cape May and Cape Henlopen in Delaware. Lots of other real estate has been swallowed, but records of historical markers at the mouth of the bay have been more diligently maintained. The residents demand that sand be dredged and dumped on their beaches to keep even with the destructive forces at work. All of this ultimately useless resistance to Nature costs a great deal of money. Those who observe the contest between the protests of King Canute and the resistance of other New Jersey taxpayers to rising taxes estimate that around 2040 the cost of interrupting the barrier island cycle will become so burdensome that taxpayers will successfully put a stop to resisting natural beach erosion. The political uproar will surely be horrendous, so there is a good reason for oceanographers to avoid going public with these inconvenient truths. And all of this doomsday talk, by the way, ignores the issue of global warming, which will surely make it all the worse. Pirate Lair

Delaware takes a ninety-degree turn right at about the place where the Salem nuclear cooling towers are visible on the Jersey shore, and great quantities of silt have piled up in the river there, making marshes and swamps. There is a rumor that Captain Kidd tied up among these marshy islands, and much better evidence that Blackbeard the Pirate used the Delaware marshes as a hideout. Since a high-speed highway, with limited access, now rushes visitors to the slot machines of Dover and the beaches of Lewes, no one much notices that this area hasn't changed much from what it probably looked like three hundred years ago. But if you take the old road, Delaware Route 9, you wander through the backcountry and are only likely to meet duck hunters. At one point, with a lake to one side and the river on the other, a watchtower has been erected for bird watchers and the like. It's very beautiful there, and quiet. So one day I drove up, parked my car at the base of the tower, and climbed a hundred steps to the top. Blackbeard was not in evidence, but it was easy to see how he might feel pretty secluded in the coves and behind the trees. There were lots and lots of birds, interesting enough but mostly unidentifiable by me. Like most big-city lovers of the environment, I mostly classify birds as little brown jobs (LBJ) and big black buggers (BBB). And then a car drove up, with some chattering teenagers.

From a hundred feet up, it was hard to tell what they were saying, and it probably didn't matter much. Until suddenly one of the girls screeched out, "Oh look! There's a big snake under that man's car! " One of the boys in the car shouted out, "That's a copperhead snake! I've never seen one so big!" And so, they roared off into the distance, leaving the marshy paradise to me and the snake. What do I do now? I waited, hoping the snake would go away. But it started to get dark, and now it was even more unattractive to chase around with snakes. So, creeping to the bottom of the stairs, I made a dash for the car door, jumped in, and slammed it tight. As I drove away, I could not see any snake on the ground under the place where I had parked. To this day, I don't know if there really was a snake there or not. Nature Preservation

Although Philadelphia is proud of its history and its historical buildings, it would be my observation that Philadelphia is not as intense about the preservation of Nature as some other parts of the country appear to be. Philadelphians like nature all right, but it tends toward azaleas a little, and only infrequently do you meet someone in our town who could fairly be sneered at as a tree-hugger. In fact, I believe I sense it being implied that non-Philadelphians are so impassioned about minnows and spotted owls because they have no old houses to be worked up about. But perhaps I only read that into their unguarded remarks. It must be admitted that some efforts to preserve nature have had unintended consequences. In the Serengeti region of Africa, a grassland between Kenya and Tanzania, about two million animals migrate in great herds, following the equatorial rainfall. The zebra and gnu are the main herds, with lions and leopards lurking around the edge, and vultures in the trees and hyenas and baboons further out, waiting for something edible to stumble. Several dozen jeeps and land rovers carry the tourists around to see the fun. It's a Disneyworld for American tourists. It's a little disquieting to learn that the local government sends helicopters around to machine-gun the poachers, and thus it's a little disturbing to think that starving people are being shot for the benefit of the tourist trade, if not for the tourists personally. Perhaps it doesn't matter, because most of the locals will be dead from AIDS in ten years, but most of the tourists who hear these arguments rehearsed fall strangely silent.

And then, back in old Philadelphia again, a lady at an Athenaeum reception was telling her circle of friends about an eagle's nest that appeared on her country place, but don't tell anyone. The nest last year was as big as a Volkswagen, this year it's as big as a Subaru, but don't tell anybody about it. Well, why not? Her husband quickly intervened to relate that the laws protecting the bald eagle and its nests are so severe that people for several miles around such a nest are bound by terribly onerous restrictions and subject to strict penalties. So? Well, the people who have been annoyed by these unwelcome laws will sneak in and shoot the eagle, just to get rid of the whole nuisance. So, the laws intended to protect our symbolic national birds actually have the effect of provoking their slaughter. It's my view that these stories with an unspoken moral reflect discomfort with having people in one region of the country promote laws which mainly affect people in some other part of the country. We don't want people in Oregon to introduce legislation regulating the restoration of Society Hill buildings. So, we are not quick to support legislation regulating the drilling for oil in that remote mosquito-infested swamp called the Arctic Wildlife Preserve, when we hear that the local Alaskans are cool to the idea. It begins to sound like R versus D, so let's dance away from the topic. If there's some way to let Alaskans decide what's good for Alaska, maybe it's better. The Delaware valley had been settled by Europeans for sixty years before William Penn arrived. Roughly, fifteen years of the Dutch, followed by fifteen years of Swedes, fifteen years of Dutch again, fifteen years under the English Duke of York. There were over a thousand people living here who spoke Swedish. With a focus on what the environment was like and how the early settlers treated it, listen to a passage from The Making of Pennsylvania by Sidney George Fisher. The woods at that time were quite free from the underbrush and afforded a short nutritious form of grass. It was easy to ride on horseback anywhere among the trees. But the second growth, which came after cutting or burning the primeval forest, brought on the underbrush and destroyed the woodland pasturage. The Swedes never attempted to clear the land of trees. They took the country as they found it; occupied the meadows and open lands along the river, liked them, cut the grass, plowed and sowed, and made no attempt to penetrate the interior. But as soon as the Englishman came he attacked the forests with his ax, and that simple instrument with a rifle is the natural coat-of-arms in America for all of English blood. In nothing is the difference in nationality so distinctly shown. The Dutchman builds trading posts and lies in his ship offshore to collect the furs. The gentle Swede settles in the soft, rich meadowlands, and his cattle wax fat and his barns are full of hay. The Frenchman enters the forest, sympathizes with its inhabitants, and turns half savage to please them. All alike bow before the wilderness and accept it as a fact. But the Englishman destroys it. There is even something significant in the way his old charters gave the land straight across America from sea to sea. He grasped at the continent from the beginning, and but for him, the oak and the pine would have triumphed and the prairies still are in possession of the Indian and the buffalo. Nevertheless, the Swede seems to have lived a very happy and prosperous life on his meadows and marshes. He was surrounded by an abundance of game and fish and the products of his own thrifty agriculture, of which we can now scarcely conceive. The old accounts of game and birds along Delaware read like fairy tales. The first settlers saw the meadows covered with huge flocks of white cranes which rose in clouds when a boat approached the shore. The finest varieties of fish could be almost taken with the hand. Ducks and wild geese covered the water, and outrageous stories were told of the number that could be killed at a single shot. The wild swans, now driven far to the south and soon likely to become extinct, were abundant, floating on the water like drifted snow. Onshore the Indians brought in fat bucks every day, which they sold for a few pipes of tobacco or a measure or two of powder. Turkeys, grouse, and varieties of songbirds which will never be seen again were in the fields and woods. Wild pigeons often filled the air like bees, and there was a famous roosting-place for them in the southern part of Philadelphia, which is said to have given the Indian name, Moyamensing, to that part of the city. Native Habitat

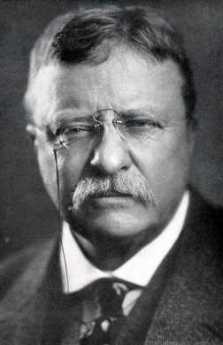

Teddy Roosevelt's friend Gifford Pinchot is credited with starting the nature preservation movement. He became a member of the Governor's cabinet in Pennsylvania, so Pennsylvania has long been a leader in the formation of volunteer organizations to help the cause. Sometimes the best approach is to protect the environment, letting natural forces encourage the growth of butterflies and bears in a situation favorable to them. Sometimes the approach preferred has been to pass laws protecting threatened species, like the eagle or the snail darter. Sometimes education is the tool; the more people hear of these things, the more they will be enticed to assist local efforts. The direction that Derek Stedman of Chadds Ford has taken is to help organize the Habitat Resource Network of Southeast Pennsylvania.

The thought process here is indirect and gentle, but sophisticated; one might call it typically Quaker. Volunteers are urged to create a little natural habitat in their own backyards, planting and protecting plant life of the sort found in America before the European migration. If you wait, some insects which particularly favor the antique plants in your garden will make a re-appearance, and in time higher orders like birds that particularly favor those insects, will appear. The process of watching this evolution in your own backyard can be very gratifying. To stimulate such habitats, a process of conferring Natural Habitat certification has been created. In our region, there are over three thousand certified habitats. Of course, you have to know what you are doing. Provoking people to learn more about natural processes is the whole idea. For example, milkweed. That lowly weed is the source of the only food Monarch butterflies will eat, so if you want butterflies, you want milkweed. For some reason, perhaps this one, the Monarch is repugnant to birds, so Monarchs tend to flourish once you get them started. After which, of course, they have their strange annual migration to a particular mountain in Mexico. Perhaps milkweed has something to do with that.

If you plant trees and shrubs along the bank of a stream, the shade will cool the water. That attracts certain insects, which attract certain fish. If you want to fish, plant trees. And then we veer off into defending against enemies. The banks of the Schuylkill from Grey's Ferry to the Airport are lined with oriental Empress trees, with quite pretty purple blossoms in the Spring. These trees seem to date from the early 19th Century trade in porcelain (dishes of "China" ) on sailing vessels. The dishes were packed in the discarded husks of the fruit of the Empress tree, and after unpacking, floated down the Schuylkill until some of them sprouted and took root. Empress trees are certainly an improvement over the auto junkyards hidden behind them. On the other hand, Kudzu is an oriental plant that somehow got transported here, and loved what it found in our swamplands. Everywhere you look, from Louisiana to Maine, the shoreline grasslands are a sea of towering Kudzu, green in the spring, yellow in the fall. It may have been an interesting visitor at one time, nowadays it's a noxious weed. So far at least, no animals have developed a taste for Kudzu, and no one has figured out a commercial use for it. When an invasive plant of this sort gets introduced, native habitat and its dependent animal life quickly disappear. So, in this situation, nature preservation takes the form of destroying the invader.

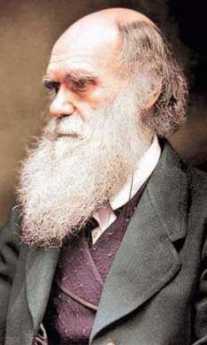

But where is Charles Darwin in all this? The survival of the fittest would suggest that successful aggressors are generally fitter, so evolution favors the victor. Perhaps swamps are somehow better for being dominated by Kudzu, pollination might be enhanced by killer bees. At first, it might seem so, but if the climate or the environment is destined to be in constantly cycling flux, diversity of species is the characteristic most highly desired. For decades, biologists have puzzled over the surprising speed of adaptation to environmental change. Mutations and minor changes in species seem to be occurring constantly, and most of them are unsuccessful changes. But when ocean currents change, or global warming occurs, or even man-made changes in the environment alter the rules, we hope somewhere a favorable modification of some species has already occurred standing ready to take advantage of the changing environment. Total eradication of species variants, even by other species which are temporarily better adapted, is undesirable. In this view, the preservation of previously successful but now struggling species is a highly worthy project. The meek, so to speak, will someday have their turn, will someday inherit the earth. For a while.

And finally, there are variants of the human species to consider. To be completely satisfying, a commitment to preserving "native" species in the face of aggressive new invaders must apply to our own species. Surely, a devotion to preserving little plants and insects against the relentless flux of the environment does not support a doctrine of driving out Mexican and Chinese immigrants at the first sign of their appearance, like those aggressive Asian eels plaguing the St. Lawrence Seaway?. Here, the answer is yes, and no. For the most part, invasive species are aggressive mainly because they find themselves in an environment which contains no natural enemies. If that is the case, fitting the newcomers into a peaceful equilibrium is a matter of restraining their initial invasion long enough for balance to be restored through the inevitable appearance of natural enemies. So, if we apply our little nature lessons to social and economic issues related to foreign immigration, the goal becomes one of restraining an initial influx to a number which can be comfortably integrated with native tribes and clans. In the meantime, we enjoy the hybrid vigor which flourishes from exposure to new ideas and customs. In the medium time period, that is. For the long haul, if the immigrant tribes really do have -- not merely a numerical superiority -- a genetic superiority for this environment, perhaps we natives will just have to resign ourselves to retreating into caves. WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1219.htm Furniture for the Horse Country

Low-end furniture for America is now mostly made in China, and seldom made of wood. Truly American cabinet making tends to be high-end, and high priced. That tendency goes to some sort of extreme around Unionville in Chester County, where a 25-year old company named Kinloch Woodworking holds pride of place. The owner, D. Douglas Mooberry, picked the name Kinloch at random from a map of Scotland, but his selection of southern Chester County was not an accident. The influence of nearby Winterthur has infused that whole region with an interest in fine furniture craftsmanship, and museums like the Chester County Museum and others throughout the nearby Pennsylvania Dutch country provide an ample source of authentic pieces to serve as examples. There's one other factor at work. As Doug Mooberry quickly noticed, people with money usually have lots of it. There really is a market for $28,000 tall case clocks, $18,000 highboys, and $12,000 tables -- if you can convince people in Chester County you are really good. Although this 12-person company repairs antique pieces, it does not make exact reproductions. It produces new pieces in the old style of the region, based on careful analysis and evaluation of museum pieces from earlier times. Kinloch once aspired to equal the quality of the early artisans, but now aspires to surpass them in quality of materials and workmanship. The more conventional stance of fine artists is to attempt to excel in today's current style, whatever that may be, probably "post-modern". Kinloch artists, however, choose to excel in the style of a long-past era, taking care not to claim the product is antique. Artisans grow up in cooperative clusters; there's a world-famous veneer company nearby and a pretty good hardware company, although the best craftsmen of furniture hardware are still found in England.

The characteristic style of Chester County furniture in the Eighteenth Century was a mixture of two neighboring cultures, Queen Anne, Chippendale, ball and claw Georgian style of Philadelphia; and the "line and berry" inlay style of the Pennsylvania Germans. If carefully executed, this hybrid style can be very pleasing, and you had better believe it requires painstaking craftsmanship. Others will have to explain the significance or symbolism of intersecting hemi-circles in the lines, and the inlaid wood hemispheres, the berries, at the end of the lines. But the technical difficulty of laying strips of 1/16 inch wood in curved grooves only a thousandth of an inch wider, or the matching of 3/8th-inch wood hemispheres into hemispheric holes gouged out of the main piece -- making the surfaces of the inlays perfectly smooth -- is immediately obvious to anyone who ever tried to whittle. Ultimately, however, true artistry lies in combining two unrelated styles without producing an aesthetic clash. By the way, you would be wise to wax such furniture once a year. The factory is on Buck and Doe Run Road, and here's another culture clash. At one time, Lammot du Pont cobbled a 9000-acre estate out of several little country villages. In 1945 it was sold to the Kleberg family of Texas, the owners of the King Ranch. Robert Kleberg was an admiring friend of Sam Rayburn but treated the oafish Lyndon Johnson as his personal political gofer. From 1945 to 1984 Buck and Doe was used as one of several remote feedlots for Texas Longhorns bred to Guernseys, the so-called Santa Gertrudis breed. Originally, Texas cattle were seasonally driven to Montana for fattening, then on to railheads for the stockyards. As farmers began to build fences interfering with the long drive over the prairies, it became cheaper to fatten cattle closer to the markets. So satellite feedlots like Buck and Doe Run were developed. You can pack more cattle in a rail car when they are younger and smaller, and advantage can be taken of price swings by suppliers who are close to the market. In this case, the markets were in Baltimore. Since the King Ranch is larger than the state of Rhode Island, such 9000-acre farms were pretty small operations in the view of the Texas Klebergs, an opinion they did not trouble to conceal from the irritated local gentry. The point was even driven home in high society circles by holding large parties at Buck and Doe Run, allowing guests to wander around the roads, unable to find the house of their host even though they had been on his property for most of an hour. In 1984 the Buck and Doe was sold to Art DeLeo, who is busily converting it into a nature conservancy. Burlington County, NJ

Burlington County used to be called Bridlington. It contains Burlington City, formerly the capital of West Jersey, which is how they styled the southern half of the colony, the part controlled by William Penn. In colonial times, the developed part of New Jersey was a strip along the Raritan River extending from Perth Amboy, the capital of East Jersey, to Burlington. To the north of the fertile Raritan strip, extended the hills and wilderness mountains; to the south extended the Pine Barrens loamy wilderness. The Raritan strip was predominantly Tory in sentiment, while the remaining 90% of the colony consisted of backwoods Dutch farmers to the north, and hard-scrabble "Pineys" to the south, except for the developments farmed by Quakers. The Quakers had ambiguous sentiments during the Revolution, leaving conflicts between pacifism and self-defense to individual discretion. The real fighting mostly went on between the Episcopalian Tories and the Scottish-Presbyterian rebels, both of which were sort of newcomer nuisances in the minds of the Quakers. The warfare was bitter, with the Tories determined to hang the rebels, and the rebels determined to evict or inflict genocide on the loyalists. Standing aside from such blood-letting of course inevitably led to a loss of Quaker political leadership. When East and West Jersey were consolidated by Queen Anne into New Jersey in 1702, the main reason was ungovernability, with animosities which endure to the present time in the submerged form. Benjamin Franklin's son William was appointed Governor through his father's nepotism, but when he turned into a rebel-hanging Tory, his father extended his bitterness about it into a hatred of all Tories. The later effect of this was felt at the Treaty of Paris, where Ben Franklin would not hear of leniency for loyalists, striking out any hint of reparations for their property losses. In a peculiar way, the factionalism resurfaced at the time of the Civil War, where the slave-owning Dutch in the North came into conflict with the slave-hating Quakers in the South. The problem would have been much worse if the Jersey slaveholders had been contiguous with the Confederacy, but it was still bad enough to perpetuate local sectionalism. A few decades ago, it was actually on the ballot that Southern Jersey wanted permission to secede. Under the circumstances, when James K. Wujcik wanted to work for progress in his native area, he avoided any ambition to enter State politics and concentrated his efforts on Burlington County. He is now a member of the Board of Chosen Freeholders of Burlington County, along with four other vigorous local citizens. Most notable among them is William Haines, the largest landholder by far in the area, whose family still controls the shares of the Quaker Proprietorship. Membership on the Burlington County Board of Freeholders is a part-time job, so Mr. Wujcik is also president of the Sovereign Bank. We are indebted to him for a fine talk to the Right Angle Club avoiding, with evident discomfort, many mentions of state politics or sociology.

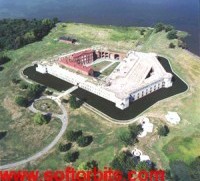

Burlington is the only New Jersey county which stretches from the Delaware River to the Atlantic Ocean, including the Pine Barrens occupying 80% of the land mass in the center; fishing and resorts dominate near the ocean and former industrial areas along the river. Much of the area has been converted to agriculture for the Garden State, but about 10% is included in a National Preserve. The population has doubled in the past fifty years, so urbanization is replacing agriculture, which had earlier displaced wilderness. The county includes Fort Dix and Maguire Air Force Base, strenuously promoted for decades by now-retired Congressman James Saxton. Somewhere in the past few decades, Burlington became quite activist. Although many tend to think of real estate planning as urban planning, this largely rural county went in for planning in a big way, deciding what it was and what it wanted to be. Generally speaking, its decision was to replace urban sprawl with cluster promotion. The farmers didn't like an invasion by McMansions or industries, while the towns lost their vigor through tax avoidance behavior of the commuter residents. Overall, the decision was to push urban development along the river in clusters surrounding the declining river towns, while pushing exurban development closer to logical commuting centers, leaving the open spaces to farmers. Incentives were preferred to compulsion, with a determination never to use eminent domain except for matters of public safety. To implement these goals, two referenda were passed with 70% majorities to create special taxes for a development fund, which bought the development rights from the farmers and -- with political magic -- re-clustered them around the river towns. The farmers loved it, the environmentalists loved it, and the towns began to revive. The success of this effort rested on the realization that exurbanites and farmers didn't really want to live near each other, and only did so because developers were looking for cheap land. Many other rural counties near cities -- Chester and Bucks Counties in Pennsylvania, for example -- need to learn this lesson about how to stop local political warfare. Corporation executives don't want to live next to pig farms, but pig farmers are quite right that they were living there, first. When this friction seeps into the local school system, class warfare can get pretty ugly.

In Burlington County, they thought big. The central project was to push through the legislature a billion-dollar project to restore the Riverline light rail to the river towns, along the tracks of the once pre-eminent Camden and Amboy Rail Road. It was an unexpected success. During the first six months of operation, ridership achieved a level twice as large as was projected as a ten-year goal. Along this strip of the Route 206 corridor, the old Roebling Steel Works are becoming the Roebling Superfund Site, now trying to attract industrial developers. The Haines Industrial Site originally envisioned as a food distribution center was sold to private developers who have created 5000 jobs in the area. Commerce Park beside the Burlington Bristol Bridge is coming along, as are the Shoppes of Riverton and Old York Village in Chesterfield Township. As Waste Management cleans up the site of the old Morrisville Steel plant across the Delaware River, a moderate-sized development project is becoming an interstate regional one. No doubt there will be bumps in these roads; the decline of real estate prices nationally is a threat on the horizon, because it provokes a flight of mortgage credit. It works the other way, too, as banks decide to deleverage by reducing outstanding loans; this is the way downward spirals reinforce themselves. And anyone who knows anything about all state legislatures will be skeptical about political cooperation in a state as tumultuous as New Jersey. The Pennsylvania Railroad destroyed the promise of this state once; some other local interest could do it again. Nevertheless, right now Burlington County looks like a real winner, primarily because of effective leadership. Galapagos As an Environmental Laboratory

The Galapagos islands are on the equator, so the sun comes up at 6 AM and sets at 6PM, every day of the year. There are storms and changes in the currents, but this place comes as close as anywhere to being a constant-weather environment, useful for observing more complex places by comparison. That's part of the scientific method -- limit the variability under study. Jack Nixon just took an extended vacation there, and told the Right Angle Club about it, with slides.

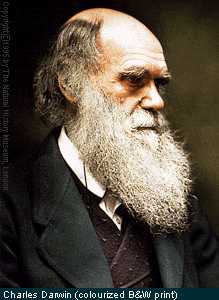

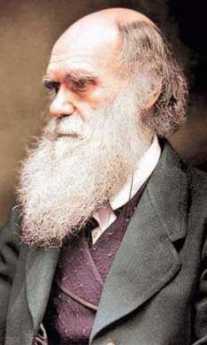

Charles Darwin, the guides relate, didn't spend much time there, and investigated very little, possibly because he suffered from incapacitating migraine all his life. He took home a collection of 13 dead finches, which after the study were from different species with subtle differences, and led Darwin to develop his theory and write his book about the origin of species. Although some people will never forgive him for upsetting the conventional view of things, it may help to know that he was a disciple of the Scottish philosopher Hume. Hume was an important factor in the American Revolution, with particular influence on Princeton and hence Scotch Irish settlers in America. Hume taught that philosophy and religion are best advanced by demanding proof that anything in nature has a purpose, because most things don't. There's a difference between having a purpose and having a utility. To Darwin, the small differences between species must have some utility to endure, and those with most utility survived better than others. The Galapagos are volcanic peaks sticking up out of the Pacific Ocean about six hundred miles from Ecuador, to whom they now belong. They have experienced a number of small eruptions, even in the past twenty years. When the bare rock cools, birds rest on it, deposit what is delicately called guano, start vegetation, allow migrant fish and animals to survive. The islands, geologically speaking, are comparatively young, started fresh and new, and have the world's most constant climate. Many of the animal species are unique to the place, and traces of how they got to be what they now are like, still persist.

Along came two waves of predatory human beings. The pirates and whalers in the first wave dumped the big tortoises into the hold of their ships as fresh meat, more or less preserved. The great big dodo birds had no wings, so they were easy to catch, delicious to fry; and like the tortoises, were comparatively easy to carry along as shipboard supplies. The dodo is extinct, the tortoises almost so. However, most tourists quickly observe that tortoises spend most of their waking hours making love, so perhaps their survival can be traced to that. The second wave of human predators were the local South American fishermen, who brought along goats and rats to devastate the fragile environment. Ecuador prizes its tourist revenue, so it has made a nearly-successful effort to eradicate goats and rats. Furthermore, immigrants are strongly discouraged; prove you have to be here or get out. Even Bill Gates had trouble getting permission to dock his yacht. This is a place to see lots of funny birds. Blue-footed boobies, frigate birds, flamingos, cormorants, pilot whales, tropical penguins, porpoises, and albatross. The albatross keeps flying all the time, and only lands in order to mate. There's some sort of recurring theme, here. www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1419.htm Vanishing Honey Bees

At the Wagner Free Institute, Professor May Berenbaum of the University of Illinois described a mystery disaster which suddenly cut the honey bee population in half during 2008. The nation's bee experts convened at emergency meetings and shared available information to try to figure out what happened. While the matter is not entirely clear, it appears that whole colonies of bees declined because the forager type of worker bee selectively disappeared. No bodies were found in the hives, and the other components of bee colonies were apparently unaffected. Foraging is a stage in the life history of worker bees which precedes their becoming honey and honeycomb workers within the hive, so a disaster for younger worker bees rapidly diminishes the older population of hive workers. Worker bees are sterile females; the fertile queens and drones are apparently unaffected. Speculation as to what has happened to American worker bees has centered on some new pesticides (neonicotinoids) and an Israeli parasite, both of which were new to the scene in the past couple of years.

Most people have little appreciation of the seriousness of this sudden problem. The price of honey can of course be expected to soar, but honey production is now only a small part of the modern bee industry. Three quarters of the revenue of beekeepers is derived from artificial pollination of flowering food plants, usually by trucking hundreds of hives from one region to another, as various food plants come into blossom. In turn, many crops are highly dependent on these bees to supplement wind pollination. The almond crop, the avacado crop, and sesame seeds are all highly dependent on honey bee pollination. The economic effects of a permanent decline in honey bees could have a serious economic effect. Professor Berenbaum is a Philadelphia girl, having been born in Levittown and educated in the region. She's a charming lady, starting off the lecture by commenting on the old birds and bees tradition. In her view, American children already know more about human sexual behavior than they know about bees. As a side note, the "Father of Modern Beekeeping" was theReverend Lorenzo Langstroth, also born in Philadelphia. While continuing his active ministry, Langstroth learned that bees would react with comb formation to crevices in the hive according to the width of the crevice. From this, he developed the now-standard rectangular hive with movable partitions, confining the queen bee to the bottom section by laying a screen above it with openings large enough to permit the worker bees to move through, but too small for the queen. Since the moveable partitions could be removed without shaking the whole hive and agitating the bees, beekeeping without hive destruction became practical. An additional feature was that the upper sections contained honey without bee larvae, and could be removed as filled, without reducing the population of bees in the hive. Langstroth's introduction of smoke blown into the hive had the effect of quieting the insects still further. Langstroth in 1848 published an instruction manual for beekeeping which is still in wide use because there was thereafter very little room for further beekeeping innovation. For many decades, honey became the main sweetener in American households. Unfortunately, the present mysterious loss of worker bees has pushed the price of a small jar to more than $40, steadily rising. One hopes the cause and cure of this malady will soon be found. In the spirit of helpfulness, the following suggestions are offered: disappearance of bees without dead bodies could be explained by insecticide toxicity somewhat better than by disease, because many diseased bees could be expected to find their way back to the hive, while poisoned ones could be killed quickly at some distance from the hive and never make it back. And one further thought is that failure of the bees to be born would explain vanished bees without corpses just as well as distant insecticides would. And the decline of feral bee populations starting in 1945 brings up a possible association with atom bomb tests, just as was seen in the sudden change in the world-wide pattern of human thyroid cancers. Just a suggestion. Sanctuaria MariposaWhen they leave us, all the shad go to the Bay of Fundy. When Monarch butterflies leave us, they head for a thousand-acre spot in the mountains of Mexico, every single one. The butterfly performance is more remarkable since a butterfly can't make it from Philadelphia to Mexico City in one lifetime. The caterpillar that hatches in Pennsylvania knows where to go and somehow tells his grandchildren how to get there. Coming back North is somewhat easier; successive generations of butterflies follow the scent of milkweed plants, which is all they will eat. This remarkable information was provided to us by the lifetime efforts of Professor Fred Urquhart of Toronto, with the volunteer help of the Girl Scouts. They tagged the insects, and other Girl Scouts reported back to headquarters whenever they found a tag or a tagged butterfly computer did the rest, and you better remember to thank them when they next offer to sell you some cookies.

Your reporter found this information irresistible, and while on a trip to Mexico hired a car and driver to go look for the Sanctuary of the Butterflies. The first tip was that drivers were remarkably reluctant to go. Although every single Monarch butterfly in Eastern North America heads for an inactive volcano that is only forty miles West of Mexico City the second largest city in the world, the trip was said to be too far to go. The roads, they are bad, the car is old, the way it is not well marked, and several other things as well. Mexico being what it is, this implausible resistance was first viewed as a way to extract a higher fee for going there, but in fact, there was a genuine worry about banditos. What is more, the roads they were in fact bad, and the car was definitely old. Admittedly, that did not match up with driving one-handed at break-neck speed.

When we reached a place where even Roberto could not drive the car further, we transferred to the back of a cattle truck, driven by Pedro, who also waved a cigarette with his free hand while we lurched and rattled up the mountain. At least he had one hand on the steering wheel, while we in the back of the truck had to clutch the wooden railing. Roberto had climbed into the back of the truck; he had decided he wanted to see these butterflies, too. It was hot when we started, so we wore T-shirts. But by the time the truck lurched to its final stop next to the souvenir shop, it was plenty cold. Butterflies seem to like it cold. What now? Now, you walk. At fifteen (?) thousand feet, your feet feel glued to the rocks you are climbing, but the trees of the sanctuary are within sight. And it is well worth the climb to come to the six hundred acres on top of a mountain, where every Monarch butterfly on the continent is either present or trying to get there. Butterflies from Texas, butterflies from Winnipeg, and somewhere in that mass were butterflies from Philadelphia. The butterflies were three feet deep on the ground, and hanging in huge balls from the limbs of trees. They don't make much noise, possibly being too busy looking for the ideal mate from the personals columns. The local guide said the really remarkable sight is on a certain day in the spring, when they all take off at once, heading for home. The sad news, unfortunately, is that the local Mexicans are cutting down the trees in the Sanctuary for the wood. We may soon see whether the butterflies go to some other hilltop, or whether we have seen the last of them. Draining Suburbia

Philadelphia's triangle of land between two large rivers once was laced with streams, brooks, and creeks. These were great places to catch fish, especially trout, and they had what poets call mossy banks. Nowadays, these streams are enclosed in culverts or their exposed banks are sharp cliffs of clay. Few people have heard of Indian Brook, which was once the brook that ran through town but is now the brook underneath Overbrook. The Conservancy has given thoughtful consideration to the consequences of building hard surfaces on top of what was once spongy soil. The streets, the roofs, the driveways of progress, of development, cause immediate runoff of water after a rainstorm instead of allowing seepage into the soil and gravel of the wilderness. The rain of a storm quickly surges into the storm sewers, and surges into the neighboring creeks, scouring the banks in a flood surge. The grass slopes cannot withstand such a housing, leading to sharp clay banks, which become undermined by later storms, toppling trees. The clay material from the banks makes the streams muddy, and the deposits of clay suffocate the insect larvae and fish eggs on the stream bottom. It's perhaps true that there are fewer mosquitoes, but there are no fish. The matter is compounded by the heating of the water as it drains over large sunlit surfaces like shopping mall parking lots, and the different water temperature in the streams changes the insect and fish content, too. It's almost hopeless to do anything useful in the downtown city areas, where the former streams are not only enclosed in pipes but run underneath skyscrapers. There may even be too much disruption involved to contemplate doing anything useful in towns which allowed storm sewage and sanitary sewage to flow in the same pipes. But it would be a comparatively simple thing to divert rainwater into gravel driveways or out over lawn areas since the goal is to slow its flow into the streams rather than dispose of it. Local ordinances could require such forethought for new construction, and perhaps make construction permits conditional on it. Many suburban homeowners would probably follow suit voluntarily, and gradually the situation might come under control with education and minor pain. There are other approaches that would get results quicker. In present China, "infrastructure" is upgraded much more directly. One recent visitor was discussing the problem of construction in an area where there was a Chinese town. He was told not to worry about it. The next time he visited the area, that town would be gone. ShadNowadays, we have fresh fruit and vegetables all year Shadround. When produce isn't in season locally, we get it from Florida and California. When even those places are out of season, we bring it in from Chile. But the supermarket and its attendant supply chains are recent phenomena. Before the two World Wars, our food was pretty drab and monotonous during the winter. The first sign of the culinary joys of spring was shad.