4 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Historical Motor Excursion North of Philadelphia

The narrow waist of New Jersey was the upper border of William Penn's vast land holdings, and the outer edge of Quaker influence. In 1776-77, Lord Howe made this strip the main highway of his attempt to subjugate the Colonies.

The present trip strikes a compromise between following a historical theme, and simply seeing what's appealing in your path between early breakfast and five o'clock cocktail; it's a little of both. We propose you start by driving for an hour to Princeton. In the course of wandering around what must be the world's most charming place to live, do notice the Revolutionary battlefield and the University. Then look reflectively northeast up Route 1 along the Raritan River to New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. On this trip there isn't time to go there, but nevertheless recall that is the valley the British swaggered down as far as Trenton on their way to Philadelphia, and back up which they retreated in a panic when Washington made things too hot for them at Trenton and Princeton. A charming and popular state park runs for sixty miles along the Delaware and Raritan Canal as a canoeing and wildlife corridor, with headquarters at Somerset and parking spaces at just about every road crossing; do plan to come back some day and try it. The region north of Princeton also offers the Monmouth battlefield, Doris Duke's show gardens, Morristown where Washington spent a cold winter near the British fleet at Perth Amboy, all of which are just a little too far from Philadelphia to include on a one-day trip. The Lindbergh mansion site of the famous kidnapping is also in the area, but visitors are currently not entirely welcome.

On this trip, leave Princeton and go down the road to Lawrenceville (Route 206, a piece of the Kings Highway) past one of the most sumptuous but prestigious boarding schools in the world. This is the road the British took on their second trip, while Washington was sneaking back behind them on a parallel back road. Just south of Princeton is Drumthwacket, the gorgeous mansion used by the Governor. A few hundred yards beyond the Lawrenceville school get on Interstate 195 North to Washingtons Crossing by exiting at Exit 1 and continuing along the Jersey side of the river. The crossing is from a charming village on the Pennsylvania side (over a very narrow bridge). It might be a good place to have a liesurely lunch.

Then, turn left going south along the old river road on the Pennsylvania side, taking care to notice the better parts of Trenton across the river. Keep going through Morrisville to Pennsbury, a restoration of William Penn's magnificent estate on the riverbank. It's best to call ahead to Pennsbury, because sometimes there are thousands of school children on tour. They usually don't stay very long. Pennsbury's bookstore is unusually well-stocked with Penn and related material. After Pennsbury turn south, close along the Delaware River, going to Bristol. There's a purpose to directing visitors to follow this route through what Philadelpians now mistakenly imagine is an industrial slum. In the late Nineteenth Century, the Pennsylvania Railroad (now Amtrak, of course) crossed the river at Trenton and roared down to Philadelphia on the Pennsylvania side. The charming villages along the river are thus cut off from the hinterland, paradoxically preserved, a pleasure to visit. Bristol, which once aspired to become the main city on the river, is now an isolated but splendid little town, just waiting to be ruined by gentrification.

Continue south from Bristol a couple miles on State Road to Street Road, and thence to Andalusia, the country estate of Nicholas Biddle. Nearby is Glen Foerd, the estate of the Foerderers, and a Drexel estate once belonging to a daughter of Anthony Drexel who became first a nun, then a saint. On a one-day trip, you might only have time to visit one of these showplaces, depending on how much time you spend at Pennsbury, which is the premier site along here. These mansions illustrate a way of life that flourished for a century along the upper river, surrounded by boating, fishing and duck hunting on the river side, and fox hunting on the land side. The gentlemen went to town on the steamboat, and the ladies presided while they were gone to their clubs.

That's it for one day. Turn up to Interstate 95 and on your way.

Jersey

|

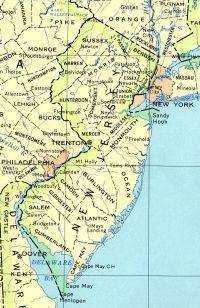

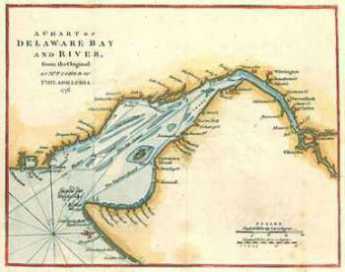

| Map of New Jersey |

Once you notice the oddity of salt water in the lower reaches of the Delaware and Hudson rivers, it gets easier to understand the current theory that southern New Jersey was once an island. Like Long Island, it was separated from the mainland by a sound, but in the Jersey case the sound silted up from Trenton to New Brunswick, creating a new peninsula of "West" Jersey by uniting the island with the mainland. The colony was named after the island of Jersey off the coast of England, a gesture for Sir George Carteret, who was given the American area out of gratitude for once sheltering the exiled royal brothers Charles II and James from Cromwell, in that other Jersey. Cape May was probably a second distinct island later joined to the larger one by the transformation of the silted ocean into the bogs of the Maurice River. Cape May started as a whaling community, populated by Quakers from New York and New England, who always maintained a social distance from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. The long Atlantic beaches of New Jersey now repeat the main geological process, with successive generations of barrier islands first heaved up by the ocean and then packed against the mainland, filling up the brackish bay. The cycle of forming and packing successive barrier islands takes about three hundred years before a new one starts. In a larger sense, the process consists of the former mountains of Pennsylvania crumbling into the ocean and then responding to wave action.

It's no mystery, therefore, why southern New Jersey is flat, broken up by turgid meandering streams which casually empty in either direction. The head of Timber Creek, which flows into Delaware, is only eight miles from the head of the Mullica River, flowing toward the ocean. During the Revolutionary War, the British found it too dangerous to sail up these winding creeks, since at any moment they might make a sharp turn and be facing a battery of cannon on the shore. An arrangement quickly grew up that buccaneers would build ships in the center of heavy oak forests and sail them out to Barnegat Bay, thence out one of the inlets of the barrier islands into the blue water. The financiers of Philadelphia, many of them with names now in the Social Register, would come from the rear, sailing up the Delaware River creeks, and walking the last mile or two to privateer headquarters on the Atlantic-flowing creeks. Auctions were conducted, in which the ships were examined, the captain interviewed, and the crew observed in target practice. If you bought a small share you would be rich when the ship returned; and if it never returned, well, you had to invest in a different one. New Jersey is indignant of the opinion that these privateers were mainly responsible for winning the Revolution, but given little credit for it. Many more British sailors were lost to the privateers than soldiers were lost to Washington's troops and the economic loss to Great Britain of the ships and cargoes eventually became serious. Since much of the profit from privateering was recycled into the American war effort by Robert Morris, the British found themselves facing an enemy much more formidable than just the ragged frozen troops at Valley Forge on the Schuylkill. Meanwhile, William Bingham was conducting a similar privateering operation in partnership with Morris but based on the island of Martinique, but that's another story.

In later centuries, the traditions and geography of the Jersey Pine Barrens suited themselves to smuggling and bootlegging during the era of alcohol Prohibition, and even after Repeal, high taxes on liquor kept bootlegging profitable. As late as the 1950s, there were divisions of FBI men prowling the woods of South Jersey, on the lookout for trucks carrying bags of cane sugar, or coils of copper tubing. After housing developments started to invade the forests, the hardball politics of South Jersey reflected a Mafia culture thought more characteristic of South Philadelphia. Near Vineland and Atlantic City, it isn't just a culture, it has the accent, because it also has some of the ancestry.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey, A Historical Account of Place names in the United States: Richard P. McCormick: ISBN-13: 978-0813506623 | Amazon |

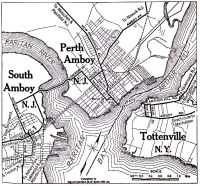

British Headquarters: Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in its 1776 Heyday (B 608)

Not many now think of the town of Perth Amboy as part of Philadelphia's history or culture, but it certainly was so in colonial times. Sadly, the town has since declined to a condition of a quiet middle-class suburb. There are quite a few Spanish-language signs around and some decaying factories. The little house of the Proprietors on the town square and the remains of the Governor's mansion overlooking the ocean are about all that remain of the early Quaker era.

|

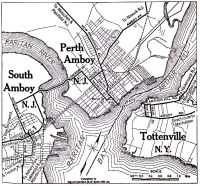

| NJ MAP |

To understand the strategic importance of Perth Amboy to Colonial America, remember that James, Duke of York (eventually to become King James the Second) thought of New Jersey as the land between them North (Hudson) River, and the South (Delaware) River. This region has a narrow pinched waist in the middle. It's easy to see why the land-speculating Seventeenth Century regarded the bridging strip across the New Jersey "narrows" as a likely future site of important political and commercial development. The two large and dissimilar land masses which adjoin this strip -- sandy South Jersey, and mountainous North Jersey -- was sparsely inhabited and largely ignored in colonial times. The British in 1776 developed the quite sensible plan that subduing this fertile New Jersey strip would simultaneously enable the conquest of both New York and Philadelphia at the two ends of it. It was a clever plan; it might have subjugated three colonies at once.

|

| PERTH AMBOY MAP |

Perth Amboy is a composite name, adding a local Indian word to a Scottish one because East Jersey had been intended for Scottish Quakers. Like Pittsburgh at the conjunction of three rivers, Perth Amboy's geographical importance was that it dominated the mouth of Raritan Bay (Raritan River, extended) as it emptied into New York Bay just inside Sandy Hook. Two of the three "rivers" of the three-way fork are really just channels around Staten Island. Viewed from the sea, Perth Amboy sits on a bluff, commanding that junction. Amboy became the original ocean port in the area, although it was soon overtaken by New Brunswick further inland when increasing commerce required safer harbors. Perth Amboy was the capital of East Jersey, and then the first capital of all New Jersey after East and West were joined in 1704 by Queen Anne. The Royal Governor's mansion stood here, as well as grand houses of Proprietors and Judges overlooking the banks of the bay. The main reason for the Nineteenth-century decline of the state capital region was the narrowness of the New Jersey waist at that point; its main geographical advantage became a curse. Canals, railroads and astounding highway growth simply crowded the Amboy promontory into an unsupportable state of isolation. The same thing can be said of Bristol, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware, but local civic pride has somehow not risen to the challenge to the same degree.

Perth Amboy to Trenton (2)

|

| Declaration of Independence |

The Revolutionary War had been raging for a year in New England before the Declaration of Independence, a point that never ceased to bother John Adams whenever Thomas Jefferson or his devotees took credit for "starting" the Revolution -- a year after the Battle of Lexington and Concord -- with a piece of paper nailed to a lamp post. To be fair, this interval of a year allowed for the organization of the Continental Army, and Washington's growing military maturity by the summer of '76. But it also explains the landing of Sir William Howe's army on Staten Island at the end of June 1776. A month or so later, his brother Admiral Howe landed some more troops. By September 1776, not all of the signers had yet put their names to the Declaration of Independence, but there were about 40,000 British troops parading around the essentially uninhabited Staten Island in New York harbor, in plain sight of the inhabitants of New Jersey's capital in Perth Amboy, scarcely a mile away.

The British were quite shrewd in selecting New York harbor as the center of their operation, since their Navy was able to move quickly from New Jersey to Rhode Island, up and down the Hudson as far as Albany, and around the considerable expanse of Long Island, not to mention Manhattan. Meanwhile, Washington was faced with crossing numerous rivers to defend hundreds of miles of shoreline, and moving foot soldiers to the necessary position. He tried to defend New York, it is true, but the battles on Brooklyn Heights, Harlem, Fort Washington, and Fort Lee were essentially unwinnable, and the best he could do with the situation was escape with an undestroyed army.

By the fall of 1776 Howe had consolidated his hold on New York, and Washington was reduced to scattering clusters of troops around the places Howe might next choose to invade at any time. In early December, he started landing in New Jersey and marched toward New Brunswick. Washington thought that meant he was going to head for Trenton, and then down Delaware to Philadelphia. There was not much to stop him except skirmishers and Minute Men, but it was not safe for Washington to move his troops from the New York region until the intentions of the British were really clear, by which time it would probably be too late to stop the advance.

Since the Raritan Strip along which Howe and Cornwallis were advancing, was prosperous and Tory, things went pretty well for the British. After two weeks march, they finally arrived in Trenton around December 20. In this triumph, they failed to appreciate the significance of several things, however. Washington was hurriedly summoning about six little colonial armies of five hundred to a thousand men each, to join him now that the intentions of the enemy were clear. Furthermore, the Whigs or rebels of New Jersey were aroused in the Pine Barrens of the South and the hills of the North; New Jersey was not as Tory as it seemed during the initial march down along the Raritan. And, finally, the British and Hessian mercenary soldiers had ravaged the countryside almost as much as the spinmeisters of the Whig patriot cause shouted out they had. The Quaker farmers were particularly upset by the activities of the camp followers, who pillaged curtains and other things not normally attractive to marauding soldiers. And the sharpshooters, loyalist, and rebel were close enough to their own homes to dispose of another booty. It was a cakewalk from New Brunswick down to Trenton, but it was not going to be the same coming back.

Washington got ready to defend the Capitol in Philadelphia, and the wide Delaware river was the best place to do it. When Howe and Cornwallis reached Trenton, they found no boats available for miles up and down the New Jersey side of the river, artillery was planted in strategic places on the Pennsylvania side, ice was beginning to form on the river, it was cold and the December days were short. To the British commanders, Washington posed no particular military problem with his naked ragamuffins. Howe had some lady friends in New York, while Cornwallis was planning to spend a month in London before the spring military season. So the British generals made an overconfident miscalculation, and posted their troops in winter quarters, strung out in outposts from Perth Amboy to Trenton and down to Bordentown. A thousand Hessians were quartered in Trenton. By December 20th, it looked like a peaceful but boring Winter.

REFERENCES

| The Pine Barrens: John McPhee: ISBN-13: 978-0374514426 | Amazon |

Disorderly Retreat: From Trenton Back to Perth Amboy

|

| George Washington on a Horse |

A week later, they got a bad jolt; Washington declined to play by their winter rules. At the Battle of Trenton, Washington was 44 years old, six feet four inches tall or more, a horseman and athlete of outstanding skill, and as the husband of the richest woman in Virginia, accustomed to housing, feeding, transporting and getting cooperation from two hundred slaves. All of those qualities may have been of some use in the battle. But after the Battle of Trenton, Washington also emerged as a remarkably bold and creative General. In the Battle of Trenton ca-----------------999999 seen the elements of audacity, timing and courage that were notable in Stonewall Jackson, George Patton -- Virginians, both -- the Normandy Invasion, and the Inchon Landing. He forged, if he did not create, the American military tradition of inspired risk-taking. And he did it with a collection of starving amateurs, up against the best Army in the world at the time. Probably without realizing it, his coming victory at Trenton also gave Benjamin Franklin in Paris a major enticement for the French King to support the American cause. Washington produced a significant achievement, but just to make sure, Franklin exaggerated it just as much as he could.

On December 21, Washington thought Howe was immediately going to sweep on through Trenton to Philadelphia. In a day or two, he saw that wasn't the plan, organized the famous re-crossing of Delaware in bad weather, and caught and captured a thousand Hessians with a three-pronged attack which cut off their retreat and made resistance useless. The main military feature of this attack was not Christmas drunkenness among the Hessians, but the fact that General Knox had somehow transported eighteen cannon to the occasion. Nowadays, the event is marked by a reenactment on Christmas Morning, although it took place on December 26, 1776. The timing did not have to do with religious observance, it had to do with hangovers. To the great disappointment of his troops, he made them abandon the great stores of booze in Trenton because a second detachment of Hessians was in nearby Bordentown, and meanwhile, he retreated back to the Pennsylvania side of the river. As might be imagined, Howe's Cornwallis promptly came charging down from New Brunswick to exact bitter vengeance. Instead of trying to rescue their comrades in Princeton, the Bordentown Hessians took off for New Brunswick. Defiantly, Washington taunted his enemies by again recrossing Delaware to the New Jersey side, put up fortifications, just waited for them to make something of it.

Well, that's the way it was meant to seem. On the night of January 2, the two armies were facing each other with about five thousand men on both sides, but with the British much better trained and equipped. The Americans had the advantage of not being exhausted by a fifty mile forced march, except for about a thousand who had been deployed forward to skirmish and delay the British advance with sniping from the bushes. The Americans made a great deal of noise and lit many bonfires behind their fortifications. But when they advanced the next morning, the British found out where the Americans really were -- by hearing distant cannon fire coming from Princeton, ten miles back toward the north.

Washington had slipped five thousand men wide around the enemy flank during the night and had taken a parallel country road to Princeton where he defeated a rear guard of British at the Battle of Princeton. An infuriated Cornwallis wheeled his army around in pursuit, and the race was on for the supplies left undefended in New Brunswick. Washington might have been able to get there first, except his men were too exhausted, and he was afraid to risk his long-run strategy, which was to avoid head-on collisions with the main British Army.

So Washington went into winter quarters in Morristown still further to the north, and thousands of British soldiers were thus bottled up in winter quarters in Perth Amboy and New Brunswick, where scurvy, lack of firewood and smallpox gave them a few months to consider their miscalculations. But the most important action of all was getting the news to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, to tell the French king of the victory. Franklin even dressed it up a little.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey in the American Revolution: Barbara J. Mitnick: ISBN-13: 978-0813540955 | Amazon |

Perth Amboy Revisited

|

| Perth Amboy |

It's now moderately complicated to find Perth Amboy, New Jersey, even after you locate it on a map. Like New Castle DE it flourished early because it was on a narrow strip of strategic land, and like New Castle, eventually found itself cut off by a dozen lanes of highways crowded together by geography. It's an easy drive in both cases only if you make the correct turns at a couple of crowded intersections. Both towns were important destinations in the Eighteenth century, but by the Twentieth century, both were pushed aside by traffic rushing to bigger destinations. Industrialization hit the region around Perth Amboy somewhat harder than New Castle, destroying more landmarks, and bringing to an end its brief flurry as a metropolitan beach resort. If you aspire to preserve your Eighteenth-century glory, it's easier if you don't have too much progress in the Nineteenth. In Perth Amboy's defense, it must be noted that Jamestown and Williamsburg, Virginia had just about totally disappeared when noticed by Charles Peterson and John Rockefeller, but neither of those towns was run over by Nineteenth century industrialization. So, while New Castle has treasures to preserve and display, Perth Amboy seems to have only the Governor's mansion like the one notable building to work with. William Franklin, the illegitimate son of Benjamin, was the royal governor installed in this palace shortly before 1776.

|

| Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy |

While it is true that some wealthy local inhabitants did a lot to restore and maintain New Castle (and Williamsburg), the Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy was bought and made the home of Mathias Bruen, who is 1820 was thought to be the richest man in America. If Bruen had only had the necessary imagination and generosity, this was probably the best moment for Perth Amboy to have had a historical restoration. Instead, he added some unfortunate features to the mansion; it later became a hotel, and later on, an office building. Public-spirited local citizens are now trying to set things right, but the costs are pretty daunting. Someone has to find an inspired Wall Street billionaire like Ned Johnson to make over an entire town. Occasionally, a state government will do it, as has been done with Pennsbury. Or a national organization might become inspired, as happened with Mt. Vernon and Arlington. Its present state of peeling paint and makeshift repairs suggests uninterest in Perth Amboy's Governor Mansion by the State, and the absence of whatever it is that occasionally inspires fierce and determined local leadership. Perth Amboy needs some help and needs to forget about its handicaps. Sure, it's hard to commute anywhere, it's even hard to drive across the highways to the countryside. The bluff on the promontory was once quite arresting, now a rusting steel mill occupies that spot. Other than that, it doesn't look ominous or dangerous at all. It's just forgotten.

|

| Pennsbury Mansion |

Aside from the Royal Governor's former mansion, it is hard to find a historical marker or monument in this scene of former prosperity and glory, but there is one. Down on the beach is a bronze plaque, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the founding of -- Argentina. So there's a clue, which is not difficult to associate with all of the Hispanic names on the stores, and the Hispanics in evidence on all sides. They all seemed to know that this was once the capital of New Jersey, seemed pleased with it, and could point out the famous building. They are pleasant and friendly enough. Perhaps even a little too comfortable. Because, as William Franklin's famous father once said, all progress begins with discontent.

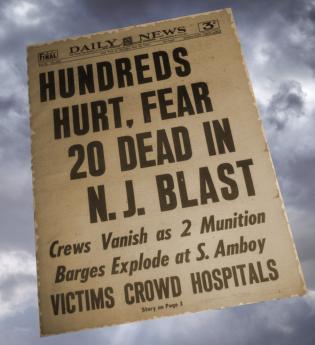

South Amboy Explodes

|

| Explosion |

South Amboy, New Jersey, is a waterfront industrial town on a remote promontory behind Staten Island, jutting into lower New York Bay. It's across the Raritan River from historically important Perth Amboy, but it's fair to say that few people ever heard of South Amboy until sunset on May 18, 1950, when they suddenly heard a lot. An entire freight train, five lighters, and a railroad pier suddenly exploded and disappeared. About twenty-five people were never seen again; the largest piece of metal from the explosion was only about a foot in length. A significant part of the town was leveled, steeples were knocked off churches, and windows were broken in five surrounding counties. Considering what caused it, it seems remarkable that so few people were killed. The explanation usually given is that the explosion blew straight up and straight down; the distant windows were smashed by pressure implosion.

When Pakistan split off from the rest of India, there were bloody migrations in which millions of people died. So Pakistan bought the rights to the design of certain land mines to protect its new borders and contracted with a firm in Newark, Ohio to manufacture the mines. Two trainloads of these explosives were shipped from Ohio to a railroad pier owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad in South Amboy, to be lightered out to a waiting cargo ship and sent to Pakistan. The first of these two shiploads sailed off uneventfully, and on May 1, 1950, the second shipment had already left Ohio and was underway, when the Coast Guard suddenly declared the South Amboy pier to be closed and forbidden. As the train chugged slowly eastward, frenzied negotiations took place with Admirals in Washington. There was plenty of time, because the train moved very, very slowly and it was detoured over six different railroads to Wilmington Delaware, where the Hercules Powder Company had packed two freight cars with dynamite, which were to be hooked onto the end of the train as it inched its convoluted way to South Amboy.

|

| South Amboy Explodes |

The method of packing the land mines was of some importance during the huge litigation which inevitably followed. Land mines were packed in cardboard boxes about six feet long, divided into six compartments. Our own Army regulations about such things state that never, never should fuse be packed in the same carton with the mines. However, this particular shipment had five mines to a carton, with the fuses in the sixth. It was later argued that this particular arrangement proved harmless in the first of the two Pakistan shipments, but there was the testimony that defective fuses were removed from those boxes and passed back up the line, where those deemed satisfactory were re-packed in the cartons which were in this, the second shipment. A fuse, by the way, does not quite describe these objects, which were screwed into a hole provided on the bomb part. They contained a spring and a steel ball in a tube; when the gadget was cocked it was held by a hare-trigger. The idea was that the pressure of stepping on the mine shot the steel ball into the ball of explosives, and boom.

The railroad ammunition pier, for some reason called The Artificial Island, consisted of two rail lines extending a quarter mile from land, but no structures. Stevedores transferred the boxes from the train to the lighters, and then five lighters took the partial shipments out to the anchorage where the ocean freighter was waiting. The deck of the lighters was lower than the train tracks, so a wooden ramp was laid from the freight car to the lighter, resting on several mattresses on deck. It all worked on the first shipment, didn't it?

Well, it didn't work this time, and we have no way of knowing who stumbled or dropped something; we only know it all went sky-high. For this, the ship-owners were delighted because it is a well-established principle of Admiralty law that unless the ship was in contact with the owners, their liability is limited to the value of the damaged vessel. Under conditions of total disintegration, that means the lighters had a liability of zero. But there were six railroads, the Pakistani government, the Coast Guard and the two manufacturers of the explosives available to sue. Everybody had insurance, so a dozen insurance companies were involved. All of the victims and hundreds of people with property damage, all had lawyers; everyone agrees that many lasting friendships were established among lawyers who were milling around. Finally, the judge declared this case just had to be settled, or else it would continue for the rest of everybody's lifetime. The total amount of the claims submitted came to $55 million. Obviously, the settlement would be for less than that, but settlements are kept secret and you are not supposed to know how it turned out.

So, the question that remained was this. If everybody was insured, why not let the insurance companies haggle about who owed what to whom. Why did all of those railroads have lawyers hanging around? Well, the answer is a lesson for all of us. You need a lawyer to watch your insurance company's lawyer, because once a claim action begins, you and your insurance company develop a conflict of interest.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1482.htm

Unintended Consequences for Advanced Placement

The Nov. 23, 2004 Wall Street Journal writes that "Elite High Schools Drop AP (Advanced Placement) Courses," thus taking me back to 1943, when I guess I started the idea now being dropped.

|

| Allan Heely |

The then Head Master of The Lawrenceville School, Allan V. Heely, came around to Yale to visit recent graduates in their college freshman year. For secondary school principals that would, in itself, be quite a novelty today. We certainly considered it a novelty to have him actually buy us a beer, since six months earlier we would have been instantly dismissed from school without hope of appeal, just for one provable beer. The alcohol issue to one side, I can see in retrospect that the Head Master made a serious effort to socialize with his senior students, inviting them to tea every afternoon, and coffee after Sunday chapel. What might sound like quaint Victorian ceremonies to an outsider were in fact conscious efforts to create a role model of the mythical Renaissance Man. He and the school chaplain played piano duets and sang witty songs of their own composition. He brought in famous guests from New York and Philadelphia and made them perform as conversationalists. Jacques Barzun and John Erskine were memorable examples. I can even see in retrospect he was displaying his elegant talented wife as an example of the sort of woman we were urged to marry. To visit his graduates in their early formative years in college was entirely in keeping with his concept of education as the basis for character development. There was even a quote from J. P. Morgan: "Brains don't make success, character does."

Well, for all his effort to be friendly, when the Head Master visits you at college it's a little hard to know what to talk about. So, to be helpful, I pointed out that the science courses were not smoothly integrated between secondary school and college. An example was the contrast between my roommate (Peter Max Schultheiss, now Professor Emeritus of Electrical Engineering at Yale) and me. Pete had scored 100 -- no mistakes on any quiz, all year -- in both Chemistry and Physics, whereas I had not taken either course at Lawrenceville at all. Yet, here were both of us in the same Freshman introductory courses at Yale, required before more advanced courses could be taken. Naturally, Pete had an easier time of it, but at the end of the year we were at the same point, and we both felt he had wasted his time taking the same courses twice. Why couldn't Lawrenceville make an arrangement with Yale to waive the requirement for some introductory courses, saving educational time for something else?

Mr. Heely did a lot better than that. At that time, ninety seniors from Lawrenceville went to Princeton every year, a hundred seniors from Andover went to Yale, and about the same number went from Exeter to Harvard. A pleasant dinner was arranged for the three headmasters and the three University presidents, at the conclusion of which the deal was done. Advanced placement was put into effect. As I understand it, the AP system gradually spread, and last year 14,900 secondary schools offered Advanced Placement courses. You could play around with those numbers and conjecture several million college person-years of education were put to better purposes over the last 62 years. It's a really nice feeling to believe that one twenty minute conversation by two eighteen-year-old boys could have such a useful effect.

So, now what's the problem with these elite high schools, that want to drop AP courses? It's hard to speak on their behalf, but I'm in a unique position to know the original idea has twisted out of shape a little. The original purpose was to eliminate mandatory repetition of introductory college courses, but nowadays competition for admission is so ferocious that repetition is considered a very smart thing, to beat the system. It works up and down the educational system, awarding a high score for coasting through a course the second time. Advance placement thus becomes a bribe not to do that, and the power of the bribe is prestige for admission to some higher level. With 15,000 high schools (like Garrison Keillor's Lake Wobegon) claiming to provide superiority, there has to be accreditation, and for that, there has to be a standardized test. Before long, the curriculum is dominated, not by what the teacher thinks is superior, but by what is likely to be on the accreditation test. In effect, we get a French-like system in which the bureaucracy dictates what is best for the Leaders of Tomorrow. That's quite different from the time when outstanding secondary schools produced an unusually good product, and colleges were asked to recognize it. It's hard to say who's been corrupted here; probably everybody, because it's mass-produced accreditation. If you want to evaluate whether to permit more or fewer waivers for a certain school, you need to evaluate earlier waivees when they reach Junior or Senior level in whatever college had previously done some waiving. Only at that longitudinal point in the process is it possible to conclude whether the waiving of repetitious introductory courses had been useful or harmful.

Underneath all of this is the self-fulfilling prophesy that graduation from a handful of elite colleges will assuredly lead to success in life. If what we need are leaders who are vicious competitors, practiced in circumventing hurdles on the way to getting to the top, credentialism is perhaps a regrettable necessity. But if, as Mr. Morgan said, it's character that matters, gaming the system is not a completely ideal way to promote it.

Advanced Placement Gains Attackers and Defenders

An abridged extract of what

|

| Naomi Riley |

Naomi Schaefer Riley writes in the October 6, 2006 Wall Street Journal, follows:

"... The rat race complaint is that AP courses put a strain on students-too many facts to memorize, too much reading. And teachers complain, too. They say that AP courses force them to teach to test.. .

"Conceived in the early 1950's by educators from three prep schools (Andover, Exeter, Lawrenceville) and three universities (Harvard, Princeton, Yale),

|

| SAT's |

the AP curricula demand that students acquire real knowledge. Unlike the SAT's which measure mental aptitude, the AP tests ask students hard questions on the history exam require students to place quotations and documents in their correct context and to identify events, dates, historical figures, and ideas....

"Why? Because college increasingly offers a crazed social experience at the expense of rigorous study. But high school does better: It is often the last time that students are forced to learn something...."

Ms. Riley goes on to imply that colleges have deteriorated into little more than binge drinking hide-outs. Since I am 62 years away from personal observation of the college scene, I can't comment or even know for certain whether things have changed much in this respect.

But on the topic of resistance to Advanced Placement, Ms. Riley explains enough to justify comment. The SAT revolution, which took place at the same time and much the same place, effectively converts the old college entrance based on genetic probabilities into the new college entrance based on mental aptitude. Since raw mental aptitude seems to be in oversupply, the final decisions are winnowed by extra-curricular success. It would appear to me that the extra-curricular success industry is threatened by proofs of academic achievement. And more importantly, since grade inflation has destroyed the value of high school transcripts, the AP courses serve as a surrogate for effective nerdiness and bookishness. In other words, the AP tests are a threat to the entitlements created by the SAT, one of which is grade inflation.

If grade inflation is under attack, that puts more pressure on high school teachers to teach, school districts to raise their salaries, and taxpayers to pay. Before that happens, there will be pressure to cut the cost of sports and other extracurricular expenses.

|

| Bill Gates |

And, come to think of it, if more nerds are admitted to prestige colleges, perhaps their social inadequacies will reduce college socializing that now appears to alarm, Ms. Riley. For proof of that trade-off, I enclose a photograph of some overachievers of 1978, two of whom dropped out of Harvard because it was unchallenging. Mr. Gates is lower left, Mr. Allen lower right.

Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping Trial

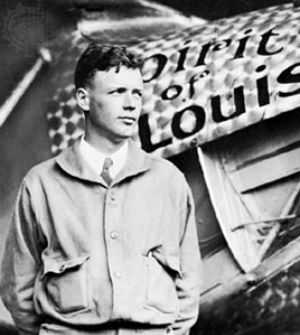

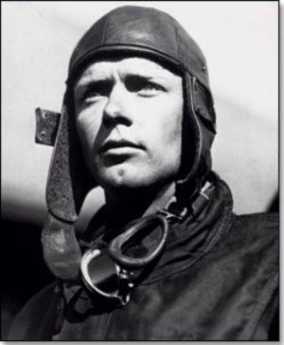

|

| Lindberg |

In 1935, Bruno Hauptmann was executed for kidnapping the baby of America's "Lone Eagle". Swarms of competing police and reporters made chaos of the scene, and Charles Lindbergh made it all worse by dealing directly with the crime underworld. Even today, some question the guilt of Hauptmann, and even whether the baby is really dead.

We are indebted to George Hawke, who went to prep school near the scene of the crime, for becoming an expert, perhaps the preeminent expert, on the Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping Trial. Charles Lindbergh, the son of a midwest pro-German congressman, flew an airplane alone across the Atlantic in 1927. He became instantly famous, wrote a best-seller called Alone, became Colonel Lindbergh, married Anne Morrow the daughter of Senator Morrow of New Jersey. That's how in short order they came to settle in Englewood, New Jersey, and also could afford an elaborate country place in Hopewell, Hunterdon County. That put them physically at the northern edge of the Philadelphia region at least on weekends, although psychologically they remained part of the New York scene, where many people attracted to publicity seem to gravitate. In 1932 they had a 19-month old son, John, who one evening disappeared from Hopewell, apparently kidnapped.

|

| Charles Lindberg Home |

What followed was a Keystone Kops Komedy in the midst of a publicity storm. The local, county, and state police, plus the FBI struggled with each other for the fame of solving the case. Newspaper reporters from all over the country swarmed down the little country road to set up shop. To illustrate the consequences, a home-made ladder was found sixty feet from the house, but no fingerprints were found by the first investigators. By the time the last investigators were done, the ladder had 150 sets of fingerprints on it. Police involvement on all levels can be summarized as a frenzy to be first to solve the case, followed in time by a frenzy to avoid being known for failing to solve it.

Although most of us eagerly following the case were unaware of it, the Colonel decided to take matters into his own hands. As a new celebrity, he was surrounded by many new best friends, and it was suggested to him that he should put out feelers into the Underground, the Mafia Mob. He would pay a ransom, and no questions would be asked. Somehow, a Bronx school principal, Dr. John Condon, was designated to respond to feelers, among them a particularly likely one, from a man who demanded to be met in a cemetery at night. As proof that the baby was still alive, the cemetery lurker sent Dr. Condon the baby's sleeping suit. Ransom was then paid in cash, unmarked, but entirely in gold certificates which had stopped being issued after President Roosevelt took us off the gold standard. The serial numbers carefully recorded. The extortionist then disappeared from sight, and the baby was never heard from again.

As time passed, two things happened. A partially decomposed baby's body was found buried a couple of miles from Hopewell, although it must be admitted it was only a quarter of a mile from an orphanage. The baby's pediatrician could not identify the body, although at the trial others claimed to make such identification. The baby's skull had been fractured, but several detectives had been seen turning it with sticks. The other development was that gold certificates bearing the recorded serial numbers began turning up in the Bronx.

|

| Bruno Richard Hauptmann |

Bruno Richard Hauptmann was apprehended at a filling station after passing a ten dollar bill of the ransom money, and when his house was searched, $14,000 more was found hidden. The police had their man. To say that the house had been searched thoroughly was quite an understatement, but a number of detectives said there was no visible disturbance in the attic. Later on, a rung of the homemade ladder found at Hopewell was found to have exactly the same grain pattern as a piece of attic floorboard, now found to be missing in the Bronx house. Although there was testimony that Hauptmann had been beaten with a hammer, he was deemed a highly suspicious character. He had a criminal record in Germany, and was in this country illegally after jumping ship.

|

| Lindberg Trial |

The Trial of Bruno Hauptmann in the Hunterdon County Courthouse at Flemington was a tumultuous circus. The state of New Jersey spent well over a million dollars on the prosecution, while Hauptmann spent $2900 on his defense, most of it provided by a newspaper, and most of it spent on a defense lawyer who appeared before a jury of farmers dressed in a cutaway, wearing a Carnation and Spats, and who told people in a bar that Hauptmann was anyway guilty. That lawyer seemed visibly inebriated much of the time, and often walked down the main street with a girl on both arms. Miles of new telephone wire were strung into the courthouse area for the reporters, and two switchboards were provided.

There were legal difficulties. At that time in New Jersey, kidnapping was only a misdemeanor, so accidental death in the course of kidnapping was not a capital offense. The Lindbergh Kidnapping Law was hastily enacted to make kidnapping a federal felony, but for the purposes of this trial, it was necessary to prosecute Hauptmann for the crime of Burglary of the sleep suit, with accidental death in the course of that burglary. Hauptmann steadfastly, and to some convincingly, denied everything. He was keeping the gold certificates for a friend.

The jury was understandably confused by all this, but it looked to them as though Hauptmann was surely guilty of something, perhaps extortion, and for all the jury knew Congress would now pass a special law about that, too. The defense did not make enough of the sleep suit, but all the jurors surely knew that such garments could be bought in any department store. There was even some question whether the Lindbergh Baby might not be dead at all, but the fact remained that Hauptmann was definitely guilty of something. He was electrocuted, and the newspapers made a great fuss about that, too.

New Jersey: A Keg Tapped at Both Ends (2)

The New Jersey legislature first fought for Independence, then about debts, then railroads and corporations, and now -- about debt, again.

|

The New Jersey legislature ratified the Declaration of Independence in the Indian King Tavern of Haddonfield, then moved to Princeton and ever since has been in Trenton. The Statehouse in Trenton is the second oldest in the nation, after the one in Annapolis, although it has grown like a snail with the original building nestled inside many additions. In one sense it is totally unique; it's the only state capitol in the nation where you can look out a window and see another state. It's right on the water's edge of Delaware, a hundred yards from those Hessian barracks that Washington surprised in 1777.

|

| Rivals, North and South |

In its early years the legislature concerned itself with raising troops during the Revolution. After that, it spent a great deal of time settling debts to pay for the Revolution. From that arose the traditional rivalry, even hostility, between the northern and southern halves of the state. To some degree, this reflects the two original provinces of East Jersey (Scottish Quakers) and West Jersey (English Quakers), but the Quaker character persisted much longer in West Jersey. The northern half, with many Dutch settlers spilling over from New York and Congregationalists from Connecticut, evolved into mainly a population of debtors; debtors enjoy inflation because it cheapens the cost of their repayments. The southern half of New Jersey, persistently Quaker in the settlement, was where creditors lived; creditors want to recover the value of the money they risked, so they hate inflation. The Mason Dixon line, extended, would cross southern New Jersey. However, it was the northern half of the state which favored the Confederacy during the Civil War, whereas the Quakers in the south were strongly opposed to slavery. Later on, irritation over permitting Atlantic City gambling was one of the various issues which eventually prompted South Jersey to try to secede from the northern spendthrifts; the secession proposition was actually on the ballot in the late Twentieth Century. Up until 1966 the Republicans always dominated the Senate, but that was because each of the 21 counties had one senator, and you can't gerrymander county lines. Then, it was deviously proposed that the state should be re-divided into 40 numerically equal Senatorial districts (i.e. instead of counties); the Senate has had a Democratic senatorial majority more or less ever since, in spite of numerous Republican majorities in state-wide elections. The legislative districts in the Assembly are reapportioned every ten years to respond to the new census; it is close to the facts that the subsequent gerrymandering of that decennial reapportionment effectively forecloses the politics (and predicts the agenda outcome) within the Assembly for each subsequent decade. In recent years, state Congressional delegations have all become increasingly polarized as a result of partisan gerrymandering. New Jersey leads the way in this unfortunate process: the Assembly and the Congressional delegation are polarized in what has become a national pattern, but in addition, its state Senate is permanently gerrymandered by substituting "districts" for "counties", and redrawing the boundaries in the state constitution.

|

| The Amboy and Camden Railroad |

Over time, the early legislature devoted most of its time to chartering corporations, because there were no universal corporation laws and each new corporation required a separate legislative charter. During the early Industrial Revolution, a great many new businesses sought the authority to limit investor liability. Each corporation had its own enabling act and hence its own deal, its own set of rules and conditions open to limiting amendments by competitors or favorable restatement at the urging of lobbyists. Along came the first railway in America, Stevens's conception of the Amboy and Camden Railroad. The New Jersey legislature, no doubt persuaded by private inducements, not only gave the Amboy and Camden permission to use eminent domain to acquire its right of way, but also conferred a perpetual tax exemption, and perpetual railroad monopoly. For the next fifty years, the legislature then concerned itself with hardly anything except railroad matters. As Willie Sutton said about banks, that was where the money was.

Perpetual is a pretty unambiguous adjective, of course, and it might be an interesting topic in judicial gymnastics to observe how the state would get itself out of the impossible economic straight-jacket of conferring a perpetual monopoly on only one railroad. It proved achievable, however, when the proprietors of a new Stanhope Railroad slipped exemptions and enabling legislation for itself into one of the thousands of corporation bills which flooded through the legislature, unread by anyone except the authors. After the Governor who also hadn't read the bill, signed this sleeper into law, the uproar was predictably loud and accusatory. In a sense, the wrangle about New Jersey railroads was not finally settled by the legislature at all but by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which crossed Delaware at Trenton, and went south to Philadelphia along the Pennsylvania side of the river. New Jersey had not only lost the advantage of railroad competition, but it had also essentially lost all of the main North-South railroad traffic made possible by improved bridge construction methods. Almost all rail traffic was East-West, and the Pennsylvania RR soon captured national dominance. Among other things, railroads thus avoided the expensive hidden costs of going before the New Jersey Legislature. New Jersey preferred to seek a new constitution with a new organization of matters, but one thing about New Jersey never seems to change. Between eleven and twelve thousand bills are still introduced every year. Overloading the attention of the legislators creates the main opportunity for corrupt politics in all legislatures, and is the central strategy for its concealment. It's even worse than New Jersey actually passes about 300 laws a year by sitting for a hundred hours in plenary session: the legislature sits for 30 or 40 three-hour sessions in the afternoon each year, usually Monday and Thursday, from November to May. We try to be a nation of laws and not of men, but it would be hard to praise the application of that truism in New Jersey, where quite obviously the Governor does most of the governing, and deciding, and dispensing. Recent Governors have evidently preferred to borrow money rather than pay any attention to balancing a budget, since New Jersey has gone during fifty years from having no income or sales tax to having the highest of them both, and the highest property taxes, plus $50 billion in debt. Let's repeat the central point: the thing which will matter for a decade is how the legislature gerrymanders the voting districts after the 2010 census. The second source of corruption is the severe limitation of individual political contributions, combined with a lack of limits of donations to the County political machine; the machine totally dominates all New Jersey nominations, and by gerrymandering can ignore the general elections. The public has discovered that this process leads to the second-highest state tax rate in the nation, and wealthy people are fleeing to other states in noticeable numbers. Since wealthy people pay a disproportionate share of taxes, the disappearance of this tax source throws a major tax burden onto those with lower incomes. As this process spirals out of control, something about it must change.

Roebling

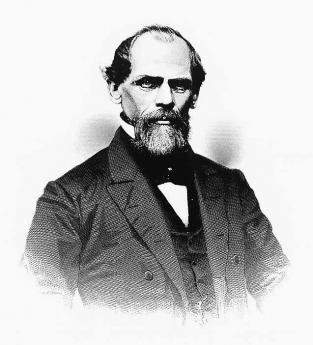

|

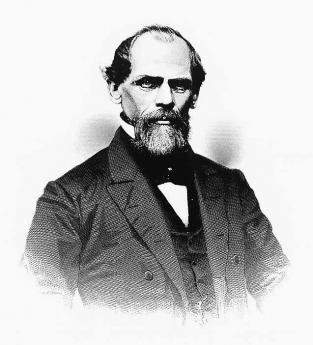

| John Roebling |

The common image of John A. Roebling comes across a little hazy about details, but seems to consist of going down with the Titanic at the age of 31, with being born in Prussia in 1837, with getting the "bends" while building the Brooklyn Bridge, and first sighting General Robert E. Lee's invading army from a balloon, then dragging a cannon up Little Round Top. The obvious inconsistencies in this image do not prove they are fictitious, they prove that Roebling was several people. Mostly this composite centers on Johann Augustus Roebling and his three sons, but spreads out to a large and highly talented family. Roebling achievements are not those of a bee, but of a beehive.

Johann was a younger child in a large Prussian family living a hundred miles south of Berlin. The region had been ruled under Napoleon for seven years, creating much of the centralized governance we now call "Prussian". Following centralized orders, its school had been designated to be an expert in science and engineering. Johann was particularly good at math and was singled out for intensive training in math and science, later sent to Berlin for advanced training in engineering. While there, he fell under the influence of the philosopher Hegel, who proclaimed that anyone could be anything he wanted to be, but opportunities were particularly good in America. Since Berlin went on to become the world center of electrical engineering, the world would probably have heard more of Johann Augustus Roebling even if he had remained at home; but he was going to do big things in the steel industry, so off he went to Pittsburgh. Things went rather well for him there, especially after he substituted wire rope for hemp rope in pulling canal boats over the Allegheny mountains. From that point on, John A. Roebling concentrated on perfecting and manufacturing wire cable, on which he held several key patents, and moved his business to the head of the Delaware Bay at Trenton, strategic in sales location between New York and Philadelphia.

|

| Wire Rope Factory |

Although his company would eventually build an open hearth steel mill, the Roebling enterprise always retained a central focus on steel cables made of steel wires bound together for flexibility and strength. The plant next door in Trenton, the Cooper, Hewitt Co., created the steel I-beam and thus was central in the construction of skyscrapers. Roebling supplied steel cable for elevators, without which skyscrapers would have been limited to six or eight stories. The wires within the cables start from what we can now visualize as the child's toy Slinkies (also a Roebling product, by the way). The trick to making such coils into cables was to find a way to straighten them out, which Roebling devised and patented, using a wheel arrangement to twist the wire as it unwound. Later, the wires were galvanized and compressed together. If the cables were used to carry electricity, it was necessary to cover the cable with rubber insulation as part of the manufacturing process. Eventually, over fifty different processes needed to be perfected and employed to create large quantities of non-brittle uniform cable product at low prices. Apparently, the central problem in manufacture was to smooth off burrs in the wire and meanwhile keep the assembly scrupulously clean. Roebling learned how to overcome all of the many problems in this deceptively simple-looking process, which eventually meant that the main problems remaining were in designing factories rather than designing cables. During the taming of the west, he produced barbed wire; during the rise of mass agriculture, he devised ways to use wire binders for sheaves of wheat. During the rise of electricity, he provided insulated wire and cable, first for the telegraph and then for the telephone. He even recognized the best business model; make huge profits during the first few years of a new product, then cut prices. By far the most famous product of the Roebling company was the suspension cable in suspension bridges.

Indeed, many people associate the Roebling name with bridge building, even though wire cable was and continued to be the central activity of the company. It was characteristic of the Roebling energy and engineering skill that he saw that if he wanted to sell cable, he had to show others how to use it, and he essentially took over the design and construction oversight of the twelve largest suspension bridges in the country. Unfortunately, his foot was crushed in a construction accident and when he died, the building of the Brooklyn Bridge had to be turned over to his son Washington Roebling. Washington, in turn, became badly crippled by caisson disease, the "bends", and hands-on oversight was conducted in large part by his wife, following meticulous instructions by her partially blinded husband.

|

| Brooklyn Bridge |

The work of building and designing factories for the company fell to Washington's brother Charles, and since the company was constantly changing focus in order to exploit new product lines, it was a prodigious task, always under time pressure. What's more, the main factories burned to the ground at least six different times, probably from arson in at least several cases. The Roeblings all worked like dogs for endless hours, well into old age. There was comparatively little ostentatious display of wealth, and when US Steel offered to buy them out, they declined an offer equivalent to one-fifth of the value of US Steel itself. That was during an economic downturn; Roebling was probably worth half of the value of US Steel. Andrew Carnegie might sell out, but not the Roeblings.

George Washington once reversed the Revolutionary War just up the street from the Roebling plant, and John Roebling's son was named after him. Roebling was a patriot and an active Republican. But there was enough Prussian in him to prefer German workmen and to hate unions. When the company grew large, he was forced to hire immigrants from what he called the Hapsburg Empire, although he never completely trusted them. Judging from his writing, he regarded unions as merely trying to take away control of the company without investing in it, certainly without earning it. Surviving numerous fires, recessions, and wartime demands for expansion without profit, it was plainly obvious that when times were tough and money had to be raised, there was no one except the owner to produce it. It is not difficult to imagine the hatred in the minds of union leaders, confronting a family that regarded lowered wages during the depression as normal and necessary. In the Roebling view, standing up to worker protests in such circumstances was simply a test of character, something an owner simply had to find the courage to do.

|

| Roebling Village 1930 |

When it became necessary to build a huge new plant at some distance downriver, the Roeblings had to contend with a shortage of labor in a region without houses. So they built a company town which they declined to name Roebling but the railroad named the stop Roebling anyway. Using engineering skill that had made Roebling the world leader, the homes were inexpensive but elegant for the time and even today. The company had to build stores, streets, schools, and everything else a town needed. The new headaches of this project took time and attention away from the central business of making steel cables, and Washington Roebling once wrote it was enough to drive you crazy.

So, guess what, the unions felt they had to take the lead in complaining and forcing the Roeblings to make changes. Guess what happened next; the Roeblings just sold it and walked away.

REFERENCES

| The Company Town: The Industrial Edens and Satanic Mills That Shaped the American Economy, Hardy Green ASIN: B003XKN7MW | Amazon |

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

William Penn: Visionary with Persuasiveness

|

| William Penn |

It was a signal and blessed providence which first induced so rare a genius, so excellent and qualified a man as Penn, to obtain and settle such a great tract as Pennsylvania, say 40,000 square miles, as his proper domains. It was a bold conception; and the courage was strong which led him to propose such a grant to himself, in lieu of payments due to his father. He besides manifested the energy and influence of his character in court negotiations, although so unlikely to be a successful courtier by his profession as a Friend, in that he succeeded to attain the grant even against the will and influence of the Duke of York himself who, as he owned New York, desired also to possess the region of Pennsylvania as the right and appendage of his province.

"This memorable event in history, this momentous concern to us, the founding of Pennsylvania, was confirmed to William Penn the Great Seal on the 5th of January, 1681."

-John F. Watson,

Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time

The Heirs of William Penn

|

| William Penn |

Freedom of religion includes the right to join some other religion than the one your father founded; William Penn's descendants had every right to become members of the Anglican church. It may even have been a wise move for them, in view of their need to maintain good relations with the British Monarch. But religious conversion cost the Penn family the automatic political allegiance of the Quakers dominating their colony. Not much has come down to us showing the Pennsylvania Quakers bitterly resenting their desertion, but it would be remarkable if at least some ardent Quakers did not feel that way. It certainly confuses history students, when they read that the Quakers of Pennsylvania were often rebellious about the rule of the Penn family.

|

| Delaware |

Such resentments probably accelerated but do not completely explain the growing restlessness between the tenants and the landlords. The terms of the Charter gave the Penns ownership of the land from the Delaware River to five degrees west of the river -- providing they could maintain order there. King Charles was happy to be freed of the expense of policing this wilderness, and to be paid for it, to be freed of obligation to Admiral Penn who greatly assisted his return to the throne, and to have a place to be rid of a large number of English Dissenters. The Penns were, in effect, vassal kings of a subkingdom larger than England itself. However, they behaved in what would now be considered an entirely businesslike arrangement. They bought their land, fair and square, purchased it a second or even third time from the local Indians, and refused to permit settlement until the Indians were satisfied. They skillfully negotiated border disputes with their neighbors without resorting to armed force, while employing great skill in the English Court on behalf of the settlers on their land. They provided benign oversight of the influx of huge numbers of settlers from various regions and nations, wisely and shrewdly managing a host of petty problems with the demonstration that peace led to prosperity, and that reasonableness could cope with ignorance and violence. When revolution changed the government and all the rules, they coped with the difficulties as well as anyone in history had done, and better than most. In retrospect, most of the violent criticism they engendered at the time, seems pretty unfair.

|

| John Penn |

They wanted to sell off their land as fast as they could at a fair price. They did not seek power, and in fact surrendered the right to govern the colony to the purchasers of the first five million acres, in return for being allowed to become private citizens selling off the remaining twenty-five million. Ultimately in 1789, they were forced to accept the sacrifice price of fifteen cents an acre. Aside from a few serious mistakes at the Council of Albany by a rather young John Penn, they treated the settlers honorably and did not deserve the treatment or the epithets they received in return. The main accusation made against them was that they were only interested in selling their land. Their main defense was they were only interested in selling their land.

As time has passed, their reputation has repaired itself, and they bask in the universal gratitude which is directed to their grandfather and father, William Penn. Statues and nameplates abound. Nobody who attacked them at the time appears to have been really serious about it, except one. Except for Benjamin Franklin, who turned from being their close friend to being their bitter enemy. Franklin tried to destroy the Penns, traveled to England to do it, and after twenty years seemed just as bitter as ever. Something really bad happened between them in 1754, and neither the Penns nor Franklin has been open about what it was.

Trenton's Tomato Pie Cult

|

| Trenton's Tomato Pie |

The ingredients of a pizza pie are so simple it comes as a shock to learn the Italian community of Trenton, New Jersey, is fanatic about putting the cheese on the dough first, and then tomatoes on top. That's the way an authentic Trenton pizza is supposed to be made, rather than the conventional method of tomatoes first, cheese on top. To emphasize the point, these pizzas are determinedly referred to as tomato pies. And to tell the truth, there is a minor difference in the taste of the product made that way. As this more or less trivial issue is dissected and debated in great detail, an important fact about ethnic food emerges.

Be patient while each ingredient is examined. The crust will rise more in the warm summer than the winter, so it's thicker after it's baked. There is a faint fermentation taste which is more pronounced with a thick crust, but everyone in Trenton agrees this is a minor point. Everyone is also in agreement that most brands of Mozzarella cheese taste about the same. Tomatoes with seeds or without, or homogenized or chunky, make a minor difference. What is ultimately the essence of a Trenton tomato pie is that the cheese is put on top of the dough first, the tomatoes next spread on top, and the pie is then baked in the oven? Not everyone would notice the difference in taste, but it's definite, and in Trenton it's important. However, the locally acknowledged historian states his opinion that the thing that makes Trenton pies distinctive is not the ingredients, but the customers.

The employees of the shop know and respect the regulars, who tend to come to the same shop at least once a week, and call out the bakers by name as they enter. When they order a tomato pie, they give the name meaningfully, almost threateningly. According to the local historian, when the sons and grandsons of the shop owners move out to the suburbs and start a pizza shop in the strip mall, it isn't long before the tomatoes go on first, cheese on top. That's the way teenagers in the burbs are used to pizzas, and that's the way they expect to get them. As John Wanamaker used to say, the customer is always right, so the social rule which emerges is that ethnic food is not shaped by ethnic cooks, but by ethnic customers. To carry the idea a step farther, ethnic food isn't food, it's the old school tie.

Washington's Circular Letters

ONCE Cornwallis surrendered to Washington at Yorktown in 1781, there emerged the usual reluctance of troops on both sides to get killed for a dispute that was already settled. The British monarchy had ample experience with wars and fully expected to exploit this trait of exhausted soldiers at the end of one. It was clear to the British the colonies could neither be reconciled nor forcibly subdued. What was not clear was how much national advantage might still be extracted from a peace conference. Bluffs and intransigence might still achieve what bayonets could not. Seasoned diplomats are accustomed to such manipulation, but the new American nation only had Benjamin Franklin grown equal to it, representing Pennsylvania and Massachusetts with the British Ministry for several years. Beyond that, however, a particularly American trait was emerging to quit the game before the last card is played. During the Nineteenth century, anticipating and resisting that irresolute temptation came to be called, Character.

The American Revolutionary Army was seldom well-fed, never well armed. Hardly anyone expected a war lasting eight years, or the British regulars to be so mean and effective. Major General Benedict Arnold had seemed like our perfect soldier but turned traitor while in charge of a major defense position at West Point, New York. Conditions for wives and children at home were bad. And the Congress in Philadelphia was willing to inflate the currency, hold back soldiers' pay, pinch pennies on supplies. Other colonies frequently promised to send more soldiers than they actually supplied. Not that they were proud of themselves; they skulked. Surely, some state legislatures and representatives were better than others, but they are almost impossible to identify, now. They all must have been somewhat complicit, or we would have heard more of them denouncing each other. It must have been supremely painful for Washington to receive promises of troops and supplies that he privately doubted, and then to be obliged to assure his troop's help was forthcoming. Inevitable disillusionment discredited him more than the Governors who put him in that position. The British troops surely shared their enemy's reluctance to get killed for a war that was over. They partied and roistered in New York, but who knows what general in London might suddenly order an attack on Washington at Newburgh, just to make overall British defeat seem less humiliating.

|

| Headquarters, Newburgh NY |

During sixteen months of this agony, Washington wrote many letters to state Governors, keeping them informed while asking for their help. The custodians of the Headquarters museum proudly show the various tables and chairs for his aides to translate French and Spanish, to make thirteen copies of just about everything, and careful files of all correspondence. Washington was an organized person, they say, or else his chief of staff was organized. Someone like Alexander Hamilton, perhaps. Out of all this headquarters communication system gradually emerged the system of Circulars. The General was in a position to see huge deficiencies in the government system for which he dedicated his life, and apparently grew haunted by the idea that all this suffering would be for nothing if the government which emerged was anything like what he was now seeing. His Circulars to the governors began to take on the style of outlining what kind of government the United States ought to have. It must, for example, acquire federal power; the states must turn over more of their own power to the decisions of a single executive. It must pay its debts; a mighty nation does not chisel its creditors. It must suppress the inclination to squabble and think the worst of one another. It must, in his phrase, be virtuous.

Two emphatic views of the new country emerged from Washington's time in Newburgh. The inability of the government to pay its soldiers, suffering or no suffering, was particularly agonizing. And the close call he had with threatened mutiny made it much worse. Robert Morris had run out of tricks and instructed him the central issue was for the Federal government to be able to levy taxes for servicing the debt, which would make it possible to borrow still more through leverage. Washington never forgot this episode, and at several points, during his later presidency, it guided him well. The other episode which made a lasting impression was to some degree his own fault. He was so impassioned in his hatred of monarchy that his closest friends, Hamilton and the two Morrises -- who had never seen much to criticize in a monarchy -- essentially gave up on trying to persuade him, and took the side of General Gates the hero of Saratoga in a planned mutiny. Washington put it down with nothing but the power of his personality and a little play-acting with his bifocals, but he almost lost the confrontation in an instant. Washington had many close calls with death on the battlefield, but these two near-defeats pretty much shaped the rest of his life as our first President. Indeed these two hatreds, of debt and monarchy, continue to characterize many Americans to a degree that others would describe as unreasonable.

And then he made a mistake. As a way of proving his lack of personal motive, he announced in advance he would be leaving public service forever. Today, every lame duck knows that's a bad idea, even when you mean it. And while he may have sincerely thought he meant it at the time, events show he really didn't. Although he probably didn't want to be indispensable, circumstances made him so. He discovered how little he knew of the technical details of government, and thus how much he needed James Madison's help. Washington lacked skill in managing finance; having depended on Robert Morris throughout the war, he needed Alexander Hamilton at least to handle a peaceful economy. But there was no running away from the central issue; he would be forced to recognize how much he overshadowed anyone else in demeanor, and so, how unlikely it was that anyone else could bully others into cooperating. He was a great-souled person, in Aristotle's phrase. Franklin alone perhaps understood and privately doubted that even Washington could pull it off. Washington's Circulars were driving him straight toward seeking the Presidency he widely proclaimed he did not want and would not accept. And thereby he threatened the one thing in life he prized more than any other: his word of honor to keep his promises.

Look Out For That Ship!

Tales of the Sea abound, even a hundred miles from the ocean.

|