4 Volumes

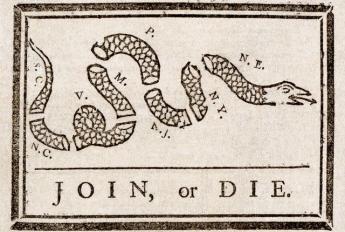

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Invaders of Pennsylvania

For a peaceful state, Pennsylvania has suffered many invasions. It's all been one-way; Pennsylvania has never invaded anyone else.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The British Attack Philadelphia

Fighting in the Revolutionary War lasted eight years; for two years (June 1776 to June 1778) Philadelphia was the main military objective of the British.

Although Carl von Clausewitz wrote his book On War in 1832, the British in 1776 anticipated his doctrine of winning wars by capturing the enemy's capital, a central step in disrupting his system of organization. George Washington, on the other hand, anticipated guerilla warfare by adapting the techniques of the Indians. You win by not losing, because the enemy eventually loses by not winning. In the later years of the war, the British came close to winning by relying more on economic strangulation, blockades and attrition. Ultimately, their opportunities seemed better in other parts of the world, so they just gave up on us to pursue easier ways to expand the British Empire.

Philadelphia in 1776 was a village of 30,000 inhabitants, surrounded in all directions by at least a hundred miles of wilderness. With vastly superior naval power, the British first unsuccessfully tried to attack Philadelphia from New York harbor down the narrow waist of New Jersey. Then they tried but abandoned getting their ships up the shallow Delaware River, filled with underwater obstructions. Finally, they circled down to Norfolk and back up the Chesapeake to attack from Elkton. But to do this the British army had to abandon their navy and supplies for eleven weeks while fighting a series of bloody battles to enter Philadelphia via Germantown. The British navy bearing their supplies circled to come back up the Delaware, but for a long time was held off at Fort Mifflin, and the stranded British army almost starved. Even after they did capture Philadelphia they soon had to abandon it, for fear the French Navy might trap them from behind in Delaware Bay.

At least in this case, capturing the enemy's capital was a strategy that wasn't effective. Economic strangulation of America almost did work. But in the end, what settled this conflict was guerrilla warfare, an Indian strategy modernized by George Washington and the Quaker, Nathaniel Greene.

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

|

| Spirit of 76' |

The American colonies were growing too big, too fast, and the British Empire had too many international distractions, to have smooth relationships across three thousand miles of ocean, using uncertain communications available in the late Eighteenth century. Friction and misunderstanding were inevitable without far more statesmanship than either side thought was necessary. So, when the Continental Congress dispatched George Washington to Boston with troops to defend rebellious Massachusetts at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it was hard for the British to believe the colonists were merely helping out one of their distressed neighbors. It seemed in London that the thirteen colonies had united, formed not only an army but a government, and gone to war. In December 1775 England passed the Prohibitory Act, essentially declaring war, and organized a huge invasion fleet to put down the rebellion. It now seems hard to understand the first notice the Americans had of this huge over-reaction was a private letter to Robert Morris from one of his agents in March 1776; no warnings, no negotiations, no attempt to investigate problems and correct them. The British just sent a fleet to settle this problem, whatever it was. It's all very well to say the Americans should have known they were playing with fire. They didn't see it that way; they were being self-reliant, responding to attack. In June 1776 British patrol frigates were skirmishing in the Delaware River; late in the month, British troops landed on Staten Island. The American reaction to all this was a muddle of confusion. A few were delighted, most of the rest were amazed or appalled.

Although the deeper strategic origins of the American Revolution are subtle, complex, and controversial, there is far less muddle about what happened on July 2, 1776, publicly proclaimed two days later. Adopting a resolution written by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, the Thirteen Colonies stated they had now clarified their goals in the controversy with the British monarchy. For a year before that, the Continental Congress had been corresponding with each other and meeting in Carpenters Hall with the goal of achieving representation in the British parliament -- "No taxation without representation". The model for most of them was based on the Whig agitation for Ireland -- for a local parliament within a larger commonwealth. But the passing of the British Navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then the actual appearance of seven hundred British warships in American waters showed that not only was Parliamentary representation out of the question, but King George III was going to play rough with upstarts. The new goal was no longer just representation, it was independence. If we were going to resist a military occupation at the risk of being hanged as traitors, we might as well do it for something substantial. The meeting had a number of Scotch-Irish Princeton graduates, whose basic loyalty to England had long been divided. Pacifist Pennsylvania, chief among the wavering hold-outs, was mostly won over by its own Benjamin Franklin, who was optimistic the French would help us. Even so, both Robert Morris and John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration; Franklin persuaded both to abstain by absence, which created a majority of the Pennsylvania delegation in favor. That's a pretty slim majority for a crucial decision. Franklin was soon dispatched back to Paris to make an alliance; Washington was dispatched to hold off that British army in the meantime. Jefferson was designated to write a proclamation, which even after editing is still pretty unreadable beyond the first couple of sentences. Meeting adjourned. This brief account may not qualify as a serious examination of the causes of the American Revolution, but it comes close to the way it seemed to the colonist in the street.

|

| Colonist's Complaint |

The rebels then spent eight years convincing the British they were serious and have been independent ever since. But, just a minute, here. Reflect on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers even waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had a big nerve implying the whole Revolution was his idea. What's more, there's a viewpoint that New England subsequently had to endure a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation because loud talk from New England still made the rest of the country nervous. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging others along with it. Rather, it was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine. When Independence was finally declared the goal, many of Philadelphia's leading citizens moved to Canada.

New England had started hostilities and was about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What New England and the Scotch-Irish needed were WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. Virginia was incensed about its powerlessness against British mercantilism, especially the tobacco trade. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing dependency on the British homeland, without a sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. It was perhaps unfortunate New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a military confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming. Without support, New England was likely to be torched, as Rome once subdued Carthage.

And the last hope for an alternative of flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, had stepped off the boat a year earlier. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, arrived with the news he had finally had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He was a man who quietly made things happen, carefully selecting his arguments from amongst many he had in mind. In retrospect, we can see that he held the idea of Anglo-Saxon world domination as far back as the Albany Conference of 1745, and could even look forward to America outgrowing England in the 19th Century. His behavior at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 strongly suggests he never completely gave up that long-term dream. Just as Edmund Burke never gave up the idea of Reconciliation with the Colonies, Benjamin Franklin never quite gave up the idea of Reconciliation with England. While John Dickinson and Robert Morris resisted the idea of Independence down to the last moment, Franklin took a much longer view. For the time being, it was necessary to defeat the British, and for that, we needed the help of the French. In 1750, America joined with the British to toss out the French. And then in 1776, we joined the French to toss out the British. Franklin didn't always get his way. But Franklin was always steering the ship.

British Headquarters: Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in its 1776 Heyday (B 608)

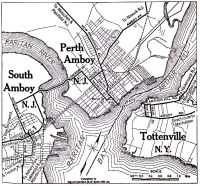

Not many now think of the town of Perth Amboy as part of Philadelphia's history or culture, but it certainly was so in colonial times. Sadly, the town has since declined to a condition of a quiet middle-class suburb. There are quite a few Spanish-language signs around and some decaying factories. The little house of the Proprietors on the town square and the remains of the Governor's mansion overlooking the ocean are about all that remain of the early Quaker era.

|

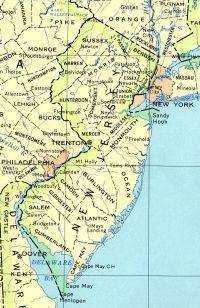

| NJ MAP |

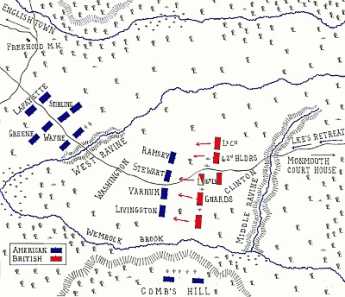

To understand the strategic importance of Perth Amboy to Colonial America, remember that James, Duke of York (eventually to become King James the Second) thought of New Jersey as the land between them North (Hudson) River, and the South (Delaware) River. This region has a narrow pinched waist in the middle. It's easy to see why the land-speculating Seventeenth Century regarded the bridging strip across the New Jersey "narrows" as a likely future site of important political and commercial development. The two large and dissimilar land masses which adjoin this strip -- sandy South Jersey, and mountainous North Jersey -- was sparsely inhabited and largely ignored in colonial times. The British in 1776 developed the quite sensible plan that subduing this fertile New Jersey strip would simultaneously enable the conquest of both New York and Philadelphia at the two ends of it. It was a clever plan; it might have subjugated three colonies at once.

|

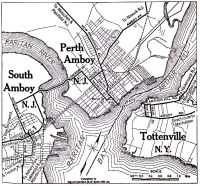

| PERTH AMBOY MAP |

Perth Amboy is a composite name, adding a local Indian word to a Scottish one because East Jersey had been intended for Scottish Quakers. Like Pittsburgh at the conjunction of three rivers, Perth Amboy's geographical importance was that it dominated the mouth of Raritan Bay (Raritan River, extended) as it emptied into New York Bay just inside Sandy Hook. Two of the three "rivers" of the three-way fork are really just channels around Staten Island. Viewed from the sea, Perth Amboy sits on a bluff, commanding that junction. Amboy became the original ocean port in the area, although it was soon overtaken by New Brunswick further inland when increasing commerce required safer harbors. Perth Amboy was the capital of East Jersey, and then the first capital of all New Jersey after East and West were joined in 1704 by Queen Anne. The Royal Governor's mansion stood here, as well as grand houses of Proprietors and Judges overlooking the banks of the bay. The main reason for the Nineteenth-century decline of the state capital region was the narrowness of the New Jersey waist at that point; its main geographical advantage became a curse. Canals, railroads and astounding highway growth simply crowded the Amboy promontory into an unsupportable state of isolation. The same thing can be said of Bristol, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware, but local civic pride has somehow not risen to the challenge to the same degree.

Perth Amboy Revisited

|

| Perth Amboy |

It's now moderately complicated to find Perth Amboy, New Jersey, even after you locate it on a map. Like New Castle DE it flourished early because it was on a narrow strip of strategic land, and like New Castle, eventually found itself cut off by a dozen lanes of highways crowded together by geography. It's an easy drive in both cases only if you make the correct turns at a couple of crowded intersections. Both towns were important destinations in the Eighteenth century, but by the Twentieth century, both were pushed aside by traffic rushing to bigger destinations. Industrialization hit the region around Perth Amboy somewhat harder than New Castle, destroying more landmarks, and bringing to an end its brief flurry as a metropolitan beach resort. If you aspire to preserve your Eighteenth-century glory, it's easier if you don't have too much progress in the Nineteenth. In Perth Amboy's defense, it must be noted that Jamestown and Williamsburg, Virginia had just about totally disappeared when noticed by Charles Peterson and John Rockefeller, but neither of those towns was run over by Nineteenth century industrialization. So, while New Castle has treasures to preserve and display, Perth Amboy seems to have only the Governor's mansion like the one notable building to work with. William Franklin, the illegitimate son of Benjamin, was the royal governor installed in this palace shortly before 1776.

|

| Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy |

While it is true that some wealthy local inhabitants did a lot to restore and maintain New Castle (and Williamsburg), the Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy was bought and made the home of Mathias Bruen, who is 1820 was thought to be the richest man in America. If Bruen had only had the necessary imagination and generosity, this was probably the best moment for Perth Amboy to have had a historical restoration. Instead, he added some unfortunate features to the mansion; it later became a hotel, and later on, an office building. Public-spirited local citizens are now trying to set things right, but the costs are pretty daunting. Someone has to find an inspired Wall Street billionaire like Ned Johnson to make over an entire town. Occasionally, a state government will do it, as has been done with Pennsbury. Or a national organization might become inspired, as happened with Mt. Vernon and Arlington. Its present state of peeling paint and makeshift repairs suggests uninterest in Perth Amboy's Governor Mansion by the State, and the absence of whatever it is that occasionally inspires fierce and determined local leadership. Perth Amboy needs some help and needs to forget about its handicaps. Sure, it's hard to commute anywhere, it's even hard to drive across the highways to the countryside. The bluff on the promontory was once quite arresting, now a rusting steel mill occupies that spot. Other than that, it doesn't look ominous or dangerous at all. It's just forgotten.

|

| Pennsbury Mansion |

Aside from the Royal Governor's former mansion, it is hard to find a historical marker or monument in this scene of former prosperity and glory, but there is one. Down on the beach is a bronze plaque, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the founding of -- Argentina. So there's a clue, which is not difficult to associate with all of the Hispanic names on the stores, and the Hispanics in evidence on all sides. They all seemed to know that this was once the capital of New Jersey, seemed pleased with it, and could point out the famous building. They are pleasant and friendly enough. Perhaps even a little too comfortable. Because, as William Franklin's famous father once said, all progress begins with discontent.

Philadelphia Vaguely Hears About Bunker Hill

The thirteen English colonies were far apart in the Eighteenth century, communicated very little, regarded their religions as more or less hostile to each other. July 4, 1776, was indeed a major turning point, but Thomas Jefferson's role was mainly to write a defensive tract to convince the colonial population and the rest of the world that the colonies had little choice but to fight. It was mainly Benjamin Franklin who recognized they could not win without foreign support, and could not expect foreign (French) support if they appeared to be willing to rejoin the British Empire. In a single action, more or less on one day, the American Revolution was transformed from New England demanding a separate parliament within a Commonwealth, into thirteen colonies fighting for Independence from Great Britain. Such a war could not be won without Virginia, the largest and richest colony, or without Pennsylvania, physically uniting the other two power centers. Virginia had serious difficulties with the British concerning its tobacco trade and its local land ambitions. Essentially, the main holdout was Pennsylvania, whose main problem now was that it was a contented prosperous state, suddenly forced to make unwelcome choices. Without Franklin's presence, it is hard to guess how things would have turned out.

|

| Bunker Hill |

To this day, Pennsylvania has trouble appreciating that things in Boston had gone too far for New England to turn back. The quarrels about English rule had gone on for decades, and the actual warfare had escalated over three years since the Tea Party, leading to thousands of casualties. Too many people had friends and relatives killed to suppress the urge for vengeance. The British king was now revealed as deeply involved in British politics and was not at all the benign father figure he had been portrayed. The British Army thought of itself as the mightiest war machine in the world and was not going to tolerate or soon forget a bloody defeat at Bunker Hill. The Prohibition Acts had been passed, the fleet had been assembled, the honor was at stake. The Quakers of Pennsylvania may have thought they had a choice, but they had little choice.

|

| Battle of Saratoga |

As a matter of fact, the British had little choice left, once the battle of Saratoga was over. With France convinced to join us (mainly by Franklin), the hope of suppressing the revolt by lack of colonist gunpowder and money was lost, and British public opinion grew progressively more opposed to warring against fellow Englishmen. Lord North seems to have realized this when he sent the Earl of Northumberland to Philadelphia to explore reconciliation, but the momentum of war forced him out of office. And the bloody revolution continued for five more years before the defeat at Yorktown forced an end to it.

The Battle of Bunker Hill probably had more effect than the questionable victory it supplied. The Americans had dragged the cannon from Ticonderoga up the mountain and they were placed on Boston's Dorchester Heights. The British saw them and rushed to get their fleet out of Boston, away from those cannon. But the Americans had no gunpowder, and Washington must have noticed you could beat the British by keeping your own nerve, even if they outnumbered you. And it wasn't the first time he saw the Brits run, he saw the same thing when he was with General Braddock.

Easy Ride: Perth Amboy to Trenton

The Revolutionary War had been raging for a year in New England before the Declaration of Independence, a point that never ceased to bother John Adams whenever Thomas Jefferson or his devotees took credit for starting the Revolution with a piece of paper nailed to a lamp post a year after Lexington and Concord. This interval nevertheless allowed for the organization of the Continental Army, and Washington's maturing military background by the summer of '76. It also allows the time for the surprisingly immediate landing of Sir William Howe's army on Staten Island at the end of June 1776. A month or so after that, his brother Admiral Howe landed more troops. By September 1776, not all of the signers had yet put their names to the Declaration of Independence, but there were about 40,000 British troops parading around the essentially uninhabited Staten Island in New York harbor, in plain sight of the inhabitants of New Jersey's capital in Perth Amboy, and scarcely a hundred miles from Philadelphia. Massachusetts and other New England Patriots have a point when they claim the Declaration of Independence marked the end of the first year of rebellion against British rule, while the other colonies prefer to say July 4, 1776, was the beginning of the war for independence. It was an irrevocable gesture of unified defiance, a copy of which was sent to the personal attention of George III.

The British shrewdly selected New York harbor as the center of their operation, since their Navy was thereby in position to shift quickly in the protected waters of Long Island Sound from New Jersey to Rhode Island, or up and down the Hudson as far as Albany, meanwhile dominating the considerable expanse of Long Island, not to mention Manhattan. It was only eighty miles travel across the narrow waist of New Jersey to the top of Delaware Bay at Trenton, potentially also leading to control of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, land-locked Washington was faced with crossing numerous rivers to defend hundreds of miles of shoreline, moving foot soldiers to defensive positions. He tried to defend New York, it is true, but the battles on Brooklyn Heights, Harlem, Fort Washington and Fort Lee were essentially unwinnable, and the best he could really do with the situation was escape with an undestroyed army. Being farther from the reach of the British Navy, Philadelphia was more defensible than New York, and besides, it was now the capital of the rebellion.

|

| Cornwallis |

By the fall of 1776 Howe had consolidated his hold on New York, and Washington was reduced to scattering small clusters of troops around the places Howe might likely invade. Those clusters were reassuring to their neighbors and easy to provision locally, but equally easy for the British to overwhelm. Washington was a better general than it seemed; these several bands of about 500 militia were expected to remain in readiness to be summoned as soon as the main British force committed itself to a major objective. In early December, the British started landing in New Jersey and marched toward New Brunswick. Washington thought that meant he was going to head for Trenton, and then down Delaware to Philadelphia. There was not much to stop him except skirmishers and Minute Men, but it was unsafe for Washington to move his troops from the New York region until the intentions of the swifter British were really clear. By that time it might be too late to stop an advance, but it couldn't be helped. Washington was inventing guerrilla warfare, patterned after his observations of the style of Indian fighting, and his observations during the French and Indian War, of the weaknesses of the British style.

Since the Raritan Strip along which Howe and Cornwallis eventually chose to advance, was prosperous and Tory, things went pretty well for the British. After two weeks march, they arrived in Trenton around December 20. In this triumph, the British failed to appreciate the significance of several things, however. Washington was hurriedly summoning six little colonial armies of five hundred to a thousand men each, to join him now that the intentions of the enemy were clear. Furthermore, the Whigs or rebels of New Jersey were aroused in the Pine Barrens of the South and the hills of the North; New Jersey was not nearly as Tory as it seemed during the initial march past the big houses along the Raritan. And, finally, the British and Hessian mercenary soldiers had indeed ravaged the countryside almost as much as the spinsters of the Whig patriot cause shouted out they had. Many neutrals were converted to rebels. The Quaker farmers were particularly upset by the activities of the camp followers, who pillaged curtains and other things not normally attractive to marauding soldiers. And the sharpshooters, both loyalist, and rebel were close enough to their own homes to dispose of another booty. It was a cakewalk down to Trenton, but it was not going to be the same coming back.

|

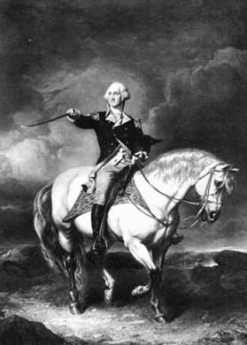

| Washington |

Washington was getting ready to defend the Capital in Philadelphia, and the wide Delaware river was the best place to do it. When Howe and Cornwallis reached Trenton, they found no boats available on the New Jersey side for miles up and down the river, artillery was planted in strategic places on the Pennsylvania side, ice was beginning to form on the river, it was cold, the December days were short. To them, Washington posed no particular military problem with his naked ragamuffins. Howe had some lady friends in New York, while Cornwallis was planning to spend a month in London before the spring military season. So the British generals made an overconfident miscalculation, and posted their troops in winter quarters, strung out in outposts from Perth Amboy to Trenton and down to Bordentown. A thousand Hessians were quartered in Trenton. By December 20th, it looked like a peaceful but boring Winter lay ahead.

REFERENCES

| Stories of New Jersey: Frank R. Stockton: ISBN-13: 978-0813503691 | Amazon |

Disorderly Retreat: From Trenton Back to Perth Amboy

|

| George Washington on a Horse |

A week later, they got a bad jolt; Washington declined to play by their winter rules. At the Battle of Trenton, Washington was 44 years old, six feet four inches tall or more, a horseman and athlete of outstanding skill, and as the husband of the richest woman in Virginia, accustomed to housing, feeding, transporting and getting cooperation from two hundred slaves. All of those qualities may have been of some use in the battle. But after the Battle of Trenton, Washington also emerged as a remarkably bold and creative General. In the Battle of Trenton ca-----------------999999 seen the elements of audacity, timing and courage that were notable in Stonewall Jackson, George Patton -- Virginians, both -- the Normandy Invasion, and the Inchon Landing. He forged, if he did not create, the American military tradition of inspired risk-taking. And he did it with a collection of starving amateurs, up against the best Army in the world at the time. Probably without realizing it, his coming victory at Trenton also gave Benjamin Franklin in Paris a major enticement for the French King to support the American cause. Washington produced a significant achievement, but just to make sure, Franklin exaggerated it just as much as he could.

On December 21, Washington thought Howe was immediately going to sweep on through Trenton to Philadelphia. In a day or two, he saw that wasn't the plan, organized the famous re-crossing of Delaware in bad weather, and caught and captured a thousand Hessians with a three-pronged attack which cut off their retreat and made resistance useless. The main military feature of this attack was not Christmas drunkenness among the Hessians, but the fact that General Knox had somehow transported eighteen cannon to the occasion. Nowadays, the event is marked by a reenactment on Christmas Morning, although it took place on December 26, 1776. The timing did not have to do with religious observance, it had to do with hangovers. To the great disappointment of his troops, he made them abandon the great stores of booze in Trenton because a second detachment of Hessians was in nearby Bordentown, and meanwhile, he retreated back to the Pennsylvania side of the river. As might be imagined, Howe's Cornwallis promptly came charging down from New Brunswick to exact bitter vengeance. Instead of trying to rescue their comrades in Princeton, the Bordentown Hessians took off for New Brunswick. Defiantly, Washington taunted his enemies by again recrossing Delaware to the New Jersey side, put up fortifications, just waited for them to make something of it.

Well, that's the way it was meant to seem. On the night of January 2, the two armies were facing each other with about five thousand men on both sides, but with the British much better trained and equipped. The Americans had the advantage of not being exhausted by a fifty mile forced march, except for about a thousand who had been deployed forward to skirmish and delay the British advance with sniping from the bushes. The Americans made a great deal of noise and lit many bonfires behind their fortifications. But when they advanced the next morning, the British found out where the Americans really were -- by hearing distant cannon fire coming from Princeton, ten miles back toward the north.

Washington had slipped five thousand men wide around the enemy flank during the night and had taken a parallel country road to Princeton where he defeated a rear guard of British at the Battle of Princeton. An infuriated Cornwallis wheeled his army around in pursuit, and the race was on for the supplies left undefended in New Brunswick. Washington might have been able to get there first, except his men were too exhausted, and he was afraid to risk his long-run strategy, which was to avoid head-on collisions with the main British Army.

So Washington went into winter quarters in Morristown still further to the north, and thousands of British soldiers were thus bottled up in winter quarters in Perth Amboy and New Brunswick, where scurvy, lack of firewood and smallpox gave them a few months to consider their miscalculations. But the most important action of all was getting the news to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, to tell the French king of the victory. Franklin even dressed it up a little.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey in the American Revolution: Barbara J. Mitnick: ISBN-13: 978-0813540955 | Amazon |

Howe's Choice: To Philadelphia, or Saratoga?

|

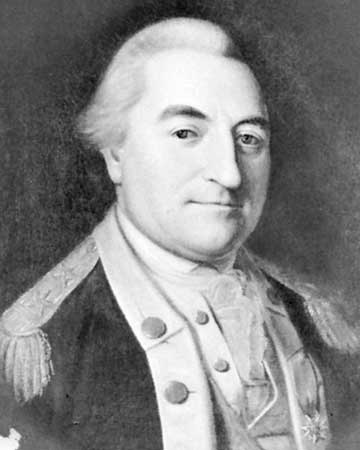

| General Howe |

Nations at war traditionally vilify the leader of the enemy, and so Sir William Howe has usually been portrayed as a lazy, illegitimate uncle of the King, a womanizer lacking in military savvy, and a former parliamentary member of the minority party supporting peace with the colonies. But to go on this way is quite unfair to Washington, who outfoxed and out-generaled a tough and very clever soldier who was by no means a pushover, and who fought hard to win.

|

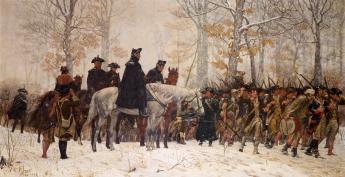

| Winter 1777 |

In retrospect, it can be seen that Howe's army was crammed into winter quarters on the Perth Amboy-New Brunswick bluff across the river from Staten Island in the winter of 1777, following the defeat at Trenton. Washington's troops were meanwhile in a fairly impregnable position around Morristown. If Howe went back along the Raritan toward Trenton and Philadelphia, he could expect to be butchered by snipers behind trees. If he embarked on his ships, he would be vulnerable during the two days of so required to break camp and load the ships. Washington's problem was actually just as bad. He had no way of knowing whether he had to defend against an encircling movement at Morristown, against a renewed invasion toward Trenton and Philadelphia, or against a quick movement at sea by the battleships. If Howe embarked, he might be going to Albany to rescue Burgoyne, or to Fort Lee to encircle Morristown, or to Philadelphia, or even to Charlestown. Anyone of these choices would mean that Washington would have to hurry overland to catch him.

It now seems clear that Howe had decided it was safe to abandon Burgoyne. He might have tried to capture Philadelphia and get back to Albany by September, but evidently, this seemed too ambitious and fraught with unexpected accidents, as events later proved to be true. Clear and unambiguous orders by Lord Germain in London were mislaid and never reached him. By implication, he was being told to use his best judgment. So he decided on a double option. He would send sorties out in all directions to keep Washington guessing and to entice him to come down from his mountain fastness into a pitched battle with British regulars. Failing that, he would get on his ships and take Philadelphia. Furthermore, Howe never told another soul what his plans were, except by sending a spy with misleading plans sewed into his coat, intending for him to be captured by the rebels. Washington, however, essentially refused to budge.

Finally, Howe ordered an embarkation onto his ships, and actually loaded a contingent of Hessians on board. Although Washington was mistrustful of a trick, his officers persuaded him to attack the "vulnerable" British while they were loading onto the transports. As soon as Howe heard of Washington's movement he immediately issued orders to turn the whole army around and trap Washington. He thought he now had his chance to catch and destroy the Continental army.

As things turned out, it didn't work and Washington escaped with most of his troops. Fearful of another such trap, he then held back perhaps too long and helplessly watched the ships load, weigh anchor, and sail out to sea. Where were they going? Not another person on the British (or Loyalist) side knew the answer, and the ships were far out to sea, invisible before they turned in whatever direction they were going. Was it North, or South?

A week later, word came to Washington that the fleet had been sighted off the mouth of Delaware. It was time to move South, in a big hurry, on foot. Howe was going to go to Norfolk, but it wasn't even certain whether he was coming back up the Chesapeake, or going still further South to Charleston. It remained conceivable that he would wait for Washington to move his troops South, then double back to New York and Albany to Join Burgoyne.

As we now know, Howe did turn up the Chesapeake to land in the rear of Philadelphia. And then Washington also guessed right and lined up his troops at Chadds Ford of the Brandywine Creek. Both of them were shrewd and very quick. Howe had won a major victory with superior resources. But as we shall see, Washington wasn't through with him.

REFERENCES

| The Uncertain Revolution: Washington and the Continental Army at Morristown: John T. Cunningham: ISBN-13: 978-1593220280 | Amazon |

Why Did Admiral Howe Choose the Chesapeake?

|

| Philadelphia Airport |

A passenger on a plane approaching a landing at Philadelphia Airport from the south can see long stretches of straight highway along the banks of the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. To drive on that highway (I-495) takes twenty or so minutes at sixty miles an hour. The thought occurs that this would have made an excellent place for Admiral Howe to land his brother's troops, well below the narrow mud flats which made Fort Mifflin so formidable, but considerably closer to his Philadelphia objective than Elkton, Maryland where he actually did land. Why would he sail all the way to Norfolk and back up the Chesapeake when a shorter Delaware trip would provide less time for Washington to prepare a defense? The long confinement of the British horses aboard ship proved to create great difficulties, which essentially undermined his plan to disembark the troops without waiting for baggage and supplies and ride into a surprised and undefended Philadelphia. And, although hurricanes were poorly understood at the time, the extra three weeks pushed the British timetable into a September landing, where they did encounter two huge storms which were probably fall hurricanes. Why did he do this when a shorter voyage seemed available?

|

| Perth Amboy NJ |

Admiral Howe was notoriously secretive about his plans. He embarked at Perth Amboy without telling a single subordinate (or superior, either) what his destination was, and did not issue orders to his helmsmen until the fleet was out of sight of land. He wanted to surprise Washington, and he trusted no one. History will, therefore, have to guess what his thinking was. The question was posed to William Dorsey, a retired river pilot, a former member of the Delaware Board of Pilot Commissioners, and historian of the port. The answer was readily given: navigation of Delaware Bay was too tricky.

Whether or not they harbored rebellious sentiments against the British, or were merely protecting the livelihoods of colonial river pilots, the Board of Port Wardens was tightly protective of the charts and lore of the Bay. One Joshua Fisher had prepared what were recognized to be the most reliable charts of the snags and shallows and was willing to sell them. The Board of Wardens would have none of this, and poor Fisher was ultimately forced to move from Lewes to Philadelphia, where he had a house in what is now Fairmount Park. Furthermore, the Board was very careful to keep Tory sympathizers from becoming Delaware River pilots.

It's never safe to guess other people's motives, and at this distance, they scarcely matter. The plain fact of things is that navigation of a fleet of seven hundred sailboats up a snaggy uncharted river, without any available experienced local pilots, was just too unsafe to attempt. An extra three weeks at sea was a far safer bet.

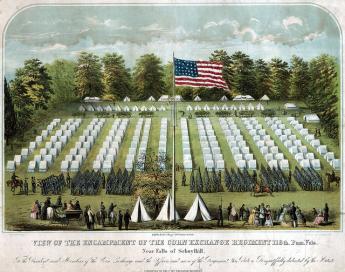

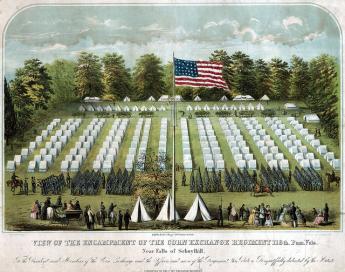

Encampment At East Falls

The urban intersection at Queen Lane and Fox Avenue in East Falls is a busy one, and except for a few stately residences, it easily escapes notice by commuters. However, the landscape forms a bowl atop a steep hill, fairly near the Schuylkill River. George Washington had evidently picked it out as a strong military position near the Capital at Philadelphia, either to defend the city or from which to attack it, as circumstances might dictate.

|

| Encampment at East Falls |

Washington's plans and thought processes are not precisely recorded, but when Lord Howe had sailed south from the Staten Island- New Brunswick area, he ordered his troops to head for an East Falls encampment at the southern edge of Germantown. Crossing the Delaware River at Coryell's Ferry (New Hope), the troops marched inland a few miles and then down the Old York Road to this encampment. Their stay at the beginning of August 1777 was quite brief because Washington changed his mind. When it took Howe's fleet longer than expected to appear in the Chesapeake, Washington became uneasy that Howe might be conducting a feint designed to draw the Continental troops south, and after cruising around the coast, might still return to attack down the undefended New Jersey corridor from Perth Amboy to Trenton. That proved wrong, but in Washington's defense, it must be said it was a plan that had actually been considered by the British. Anyway, Washington ordered his troops to pull out of the East Falls encampment and march back up Old York Road to Coryell's Crossing, which would be a more central place to keep his options open for the time when Howe's true intentions became clear. Washington and his headquarters staff went on ahead of the main body of troops, setting up headquarters at John Moland's House a little beyond Hatboro and a few miles west of Newtown, Buck's County. The Hatboro area was a pocket of Scotch-Irish settlement, without any local Tory sentiment, thus preferable to the rest of largely Quaker Buck's County.

To jump ahead chronologically, the East Falls encampment site must have seemed agreeable to the Continental Army, because a few weeks later it would be sought out as the main refuge and regrouping area, following the defeat at the Battle of Brandywine. The American troops were to withdraw from the Brandywine Creek when Washington realized he had been out-flanked, and head for Chester. Quickly recognizing that Chester was vulnerable, they headed for East Falls. Not only was Washington preparing to defend Philadelphia at that point, but was using the Schuylkill River as a defense barrier. As he had earlier done at the Battle of Trenton, he ordered all boats removed from the riverbanks, and artillery placed at any likely fording places, all the way up the Schuylkill to Norristown. Having accomplished that, this extraordinary guerrilla fighter then moved his troops from Germantown up the river to defend the fords. Meanwhile, Congress decided to move to the town of York on the Susquehanna, just in case.

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

Defeat and Disaster: Philadelphia Falls to the Enemy

|

| Howe |

Helen of Troy had launched a thousand ships. Lord Howe only launched four hundred and thirty, but they were bigger. It is estimated a thousand oak trees were cut down to build just one man o' war. To repeat what happened next, this flotilla was parked in lower New York harbor while forty thousand redcoats conquered Brooklyn Heights, Manhattan, Washington Heights, Perth Amboy, New Brunswick, Princeton, Trenton -- and then Washington promptly made fools of Howe and Cornwallis, at Trenton, Princeton, New Brunswick. Howe, and Cornwallis, in particular, were raging mad. The first year of the two-year siege of Philadelphia was over, and at half-time, the British team was popped up.

|

| Lord George Germaine |

The grand plan laid out in London by Lord Germaine was for Howe to capture New York, and maybe Philadelphia if it would be useful, while Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne took an army from Canada along that giant cleft in the earth which starts at the St. Lawrence River, down Lake Champlain, then down the Hudson from Albany to New York. The Hudson is very wide, and the British Navy would have no trouble sailing upriver to Albany, landing an army to meet Burgoyne coming south, with the effect of cutting New England off from the rest of the Colonies. Burgoyne got his orders in London shortly after Howe's January disaster in Trenton arrived in Quebec in May and started on his campaign June 20. Nothing dilatory about him. Howe, however, had six months to get to Albany before that, and several months more before Burgoyne would get to Saratoga, tromping through the woods and black flies. From Staten Island, it might have taken Howe ten days to sail to Albany in plenty of time.

|

| Chesapeake Bay |

Instead of that, Howe solitary and without advice, decided to take Philadelphia. Although the British never dwelt much on the fine points, the actual rebellion was only taking place in New England at the time the fleet set sail. It was the arrival of the fleet which triggered the Declaration of Independence, not the other way around. Lord Howe therefore probably felt some justification in revising the agreed plans and orders under which he set sail. As has been described already, the initial foray to Trenton ended embarrassingly. So, the capture of the enemy capital would now help people forget Princeton, and it would be sweet to whip Washington.

Unfortunately, they wasted a lot of time doing it. Finding Delaware too well fortified, and almost as snaggy as Henry Hudson had found it more than a century earlier, he sailed all the way to Norfolk, came up the Chesapeake and landed at the head of Elk, and marched for Philadelphia. The Brandywine Valley has deep sharp cliffs off to the right, so Cornwallis was sent off to the left as a flanker past Dilworthtown while Howe attacked Washington head on at Chadd's Ford. It was to be the largest battle of the whole Revolutionary War. When Washington found himself facing encirclement, he had to order a withdrawal. To skip a few events now memorable to the Main Line suburbs, Philadelphia was essentially then occupied without a further fight, with the British set up their defenses at Germantown, seven miles from the center of town. Three weeks later, Washington attacked Germantown in a three-pronged assault that mainly failed because two of his formations attacked each other in the fog. That was October 4, 1777. The news soon reached them that Burgoyne had surrendered the other British army --starving in the woods -- at Saratoga, New York on October 17. Howe had in effect abandoned Burgoyne in order to take Philadelphia, but it was probably as much a result of getting drawn into a tangle, as a single decision to disregard the grand plan.

In retrospect, it was quite a bad choice. All the world -- and the King of France in particular -- could see that Washington had beaten Howe at Trenton and then Gates and Benedict Arnold had soon beaten Burgoyne at Saratoga. General Gates, of course, was in charge at Saratoga, but Arnold was the flamboyant hero. Adding to his earlier exploits in Quebec and later providing the captured cannon of Ticonderoga for General Knox to drag over the mountains to Boston, thereby allowing Washington to drive the British fleet to safer distances, Arnold now essentially won two more battles at Saratoga. The first was to defeat Leger, who had been sent down Lake Ontario to come back up the Mohawk Valley to Albany. Then, turning his troops through the woods, Arnold joined Gates at Saratoga and defiantly led the charge that smashed the British line, when Gates would have been satisfied with containment. Arnold, like Alexander Hamilton, was a flamboyant man after Washington's heart.

Meanwhile, Howe settled down to enjoy winter at Philadelphia. His court jester and chief entertainer were Major Andre, who took wicked pleasure in using Ben Franklin's Market Street home as his own. There was additional satisfaction in knowing that Washington was freezing at Valley Forge.

Battle of the Clouds: September, Remember

|

| Dilworthtown |

Weather satellites, television and so on have taught us much about hurricanes that was unknown in 1777. Benjamin Franklin, it should be noted, was the first to observe that Atlantic Coast "Nor'easters" actually begin in the South and work North, even though the wind seems to be blowing in the opposite way; what's moving toward the northeast is a low-pressure zone. We now know that hurricanes begin in Africa, travel West and then veer North when they reach Florida. A great deal is still to be learned about hurricanes, but the most important thing about their timing is contained in a maritime jingle:

June, too soon.

July, stand by.

And then: September, remember.

October, all over.

Along the Atlantic east coast, the end of August to the middle of September, is hurricane season. That's when houses blow down in Florida, and heavy rains hit Pennsylvania. Admiral Howe might have had some clue to this, since Franklin made his observation around 1750, and storms are important to Admirals. But very likely his brother the General just thought it was one of those things when the British landing at Elkton, Maryland in late August 1777 was greeted with an unusually severe downpour of rain. Howe had planned to surprise Philadelphia from the rear by hitting the ground running on horseback. However, he underestimated the debilitating effect on the horses of three weeks at sea on sailboats; to unload and forage horses during a hurricane was almost too much for the plan. For that purpose, he had given orders for the troops to disembark without waiting to pitch camp, or unpacking their gear. But the drenching rain gave Washington several extra days to organize a defense, although he has been given too little credit for the strenuous accomplishment of moving an army from Bucks County to the banks of the Brandywine in that weather. Howe, whose trademark was surprise, deception, outflanking, had anticipated a sudden cavalry thrust into the backyards of unprepared Philadelphia. What he got was 2000 casualties in the biggest battle of the Revolutionary War, against Washington's well-prepared defense along the steep-sided Brandywine Creek.

Howe won this battle, in the sense that Washington was forced to withdraw, because Howe employed another British military trademark, of driving his own troops beyond humane limits in a huge outflanking movement. The countryside around Kennett Square is hilly and broken almost to West Chester, and the American Army felt reasonably prepared along a front of ten or twelve miles. But Howe drove the main force of his army seventeen miles to the north, to Dillworthtown, before turning the unprepared American right flank. And, in the now hot August weather in full uniform and battle pack, the drive continued for twenty-four consecutive hours until Washington saw he had to withdraw. This was what the British meant when they boasted of seasoned regular troops; you win by enduring more than your opponent can endure.

One has to have equal admiration for Washington. Although he was dislodged from his position, losing the opportunity to catch the British in a hostile region without a reliable source of supplies once the fleet weighed anchor, he preserved his army of marksmen and deer hunters intact during the retreat. The two armies started at roughly the same size, and Washington had only about 1300 casualties; his men had more certain supply sources, and they were fighting for their homes. The British, somewhat outnumbered, had the prospect of fighting their way without resupply through an enemy's home territory, capturing the enemy's capital, but still facing the possibility that the British fleet might not get past the Delaware River defenses. If that happened, they could celebrate their victory by starving to death. Just about the only weakness of the Continental Army was its discomfort with bayonet warfare. They could hit a squirrel at a hundred yards, but those long bayonets on the end of very long muskets were designed to protect foot soldiers from cavalry charges. It takes training to put the butt of the musket against a stone on the ground, hold your ground against an oncoming gallop of horsemen, and trust that at the last moment the horses will rear back and throw the riders. But it also takes naked bravado to wave a sword and ride full tilt into a forest of pointing bayonets, trusting that at the last moment the defenders will break and run.

But Washington knew what he was doing. He pulled the troops back to Chester, then over the Schuylkill to the Germantown encampment at Fox and Queen Lane, then up the Schuylkill to Norristown, the first ford in the river that Howe must use when the boats and bridges were destroyed. The river would hold the British while the Americans came at them from the rear; this was essentially the same river strategy he used at the battle of Trenton. Washington picked his battlefield in Chester County and got ready to fight the second installment of the Battle of Brandywine. The campus of Immaculata University now occupies the site.

And then it rained, again. Hard. The gunpowder on both sides was soaked, useless. In what has come to be known as the "Battle of the Clouds", the fighting was called off by mutual agreement. The second hurricane of the year had arrived, and Washington more or less helplessly had to watch Howe take over Philadelphia unopposed. He lost the capital, provoking dismay among the colonists, but his masterful strategy taught the British to respect him. When the British were later considering whether to hold or abandon Philadelphia, this growing respect for their adversary helped tilt their thinking toward prudence.

But that was not before Howe once more showed he too was not the lazy slacker that others had called him. General "Mad Anthony" Wayne was dispatched with fifteen hundred troops to hassle the rear of Howe's army. Wayne was confident he could hide his troops in the Radnor area where he had been brought up, but the region in fact had many Torys to report his movements. Howe ordered Major General Lord Charles Grey to take the flints from his troops' muskets, attack the American camp near Paoli's tavern in the night, and use only bayonets. Waynes' troops were scattered and slaughtered, in what came to be known as the Paoli massacre.

Fort Washington, PA

|

| British Campaigns |

The Revolutionary War lasted eight years, so there are a half dozen Fort Washingtons, in several states. Pennsylvania's Fort Washington gets free advertising from being a stop on the Pennsylvania Turnpike at the intersection of the East-West branch and the North-South branch, near some very large shopping malls. Nevertheless, the suburbs haven't reached it yet, and it is on a series of wooded mountain ridges discouraging housing development. Another way of describing its location is that it is several miles north of Chestnut Hill along the Bethlehem Pike, a road which begins in the center of Chestnut Hill at Germantown Avenue. The Pike is quite old, with many surviving colonial-era houses and inns to liven up the trip.

A third way to describe Fort Washington is that the headquarters were at the point where Bethlehem Pike crosses the Wissahickon Creek. How's that again? How does the western Wissahickon Creek then flow uphill to Chestnut Hill? Of course, it doesn't, but the appearance takes some explaining. The northwestern end of Philadelphia is reached by two ancient roads running on ridges quite close together like the split tail of a fish. Germantown Avenue runs up one ridge, and Ridge Avenue runs up the second ridge closer to the Schuylkill. The Wissahickon runs in the gully between these two ridges and tumbles down the hill at Wissahickon Avenue, or Rittenhousetown if that is more understandable. The ridge of Ridge Avenue is essentially cut off by the creek, but engineers have put Ridge Avenue on a high arching bridge as it crosses the creek far below, and by this magic Ridge Avenue and Germantown Avenue are at about the same height most of the way. The Wissahickon Creek is really running downhill the whole way, but sort of disappears from sight and reappears as it twists through the gorges, misleading the casual visitor (or commuter). As happened so often during the Revolutionary War, Washington showed his understanding here of geography in the service of guerrilla warfare.

Since the British were headquartered in Germantown, and the Americans have camped a few miles away on the same creek, it was inevitable there would be some sort of battle in the region. Washington launched a three-pronged attack on the British soon after arriving at Fort Washington, but his troops fired at each other in the fog, and apparently, two prongs more or less got lost in the gorges. The Americans retreated, and the British consolidated their conquest of Philadelphia. They did launch one surprise attack on the American encampment (the Battle of Whitemarsh), but that was mainly a reconnoiter, given up after a few days when it became clear Washington's troops held the high ground. It really is high ground (hawk-watching platforms and all) for reasons already stated. Chestnut Hill is a pinnacle sticking up on the west side of the Creek, with the Wissahickon snaking around its base.

This really was a perfect place for Washington to aim for after the Brandywine Battle, close enough to threaten the British, located in a bowl-like valley for camping, but terminating at the top of a mountain ridge in case the British counter-attacked. And with plenty of running water from the Wissahickon. However, it was a little too close for comfort, and he withdrew across the Schuylkill into Valley Forge as a more substantial natural fortress. Valley Forge is also on a hilltop, but one sitting in the middle of the Great Valley (Route 202 to Wilmington), as the center of an angel food cake tin. No doubt, the advantages of this new location became evident to him at the earlier skirmishes of the Battle of the Clouds, and the Paoli Massacre, which occurred nearby.

In retrospect, these maneuvers and skirmishes were of little military significance, except for the major Battle of Brandywine. The lost opportunity was the chance to catch the British Army without supplies or access to the Navy, aborted by what was probably a hurricane, the so-called Battle of the Clouds. Philadelphia was lost, and the opportunity to win the war early by smashing a third British army was gone for good. The defeat of the Hessians at Trenton, the loss of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga, and a victory on the outskirts of Philadelphia might together just have finished the War. But things didn't work out, the British similarly missed some opportunities, and the war was to last another five years. Once the French allied themselves, their wealth and naval strength tended to make French priorities dominate strategy.

Nevertheless, a perfectly splendid tourist trip awaits the history buff who travels from Elkton, Maryland, where the British landed, to the Battle of Brandywine battlefield, up the Great Valley to Immaculata University where the Battle of the Clouds took place, over to the Battlefield of the Paoli Massacre, crossing the Schuylkill and going to Whitemarsh, then to Fort Washington, and back up Bethlehem Pike to Germantown Avenue, and down to the Chew Mansion. The campaign for the conquest of Philadelphia ended with the fall of Ft. Mifflin when the British fleet was finally able to re-supply Howe's army. This direct auto tour is a little out of chronological sequence, but it can be done in one day if you don't dawdle. If you slow down and spend an extra day, you can include the Moland House where Washington waited to see where General Howe was going. At the right season, there's hawk watching on the ridge at Fort Washington Park, and maybe on to Trenton, or even up the New Jersey waist to Perth Amboy on lower New York Bay, where the Howe brothers began and ended their Philadelphia adventure. That would take you past Princeton and New Brunswick, or even include a trip to the Monmouth Battleground. With this extension, you have traveled much of the extent of the Revolutionary War in the Mid-Atlantic states.

The Battle of Germantown: Oct. 3, 1777

After its brief commotion from the unwelcome French and Indian War, Germantown settled down to a 22-year period of colonial inter-war prosperity and quite vigorous growth. Most of the surviving hundred historical houses of the area date from this period, and it might even be contended that the starting of the Union School had been a beneficial stimulus.

|

| Cliveden |

Two decades passed. What we now call the American Revolution started rumbling in far-off Lexington and Concord, soon moved to New York and New Jersey. General William Howe, the illegitimate uncle of King George III, then decided to occupy the largest city in the colonies, tried to get his brother's Navy up Delaware but hesitated to persist in a naval attack on the chain barrier blocking the river. He considered but abandoned trying to outflank the New Jersey fort at Red Bank, the land-based artillery at Fort Muffling, and heaven knows what else along the twisting shaggy Delaware river. Giving up on that approach, Howe sent the navy down to Norfolk and back up the Chesapeake, landing the troops at the head of the Elk River. Washington was outflanked at the Battle of the Brandywine Creek trying to head him off, although he suffered far fewer casualties than the British. A rainstorm, presumably a fall hurricane, disrupted his planned counterattack near Paoli. So Howe invested Philadelphia, organizing his main defensive position in the center of Germantown. His headquarters were in Stenton and Morris House, General James Agnew was at Grumblethorpe The Center of British defense was at set up at Market Square where Germantown Avenue crosses Schoolhouse Lane. With Washington retreating to Valley Forge, that should take care of that. Raggedy rebels were unlikely to attack a prepared hilltop position with a river on either side, defended by a large number of British regulars.

|

| George Washington |

Washington did not look at things that way, at all. Cut off from their fleet, the British situation would be precarious until Delaware could be re-opened. He had watched General Braddock conduct with bravado an arrogant suicide mission in the woods near Ft. Duquesne, and also knew the British always based as much strategy as possible on their navy. Washington's plan was to attack frontally down the Skippack Pike with the troops under his direct command, while Armstrong would come down Ridge Avenue and up from the side. General Greene would attack along Limekiln Road, while General Smallwood and Foreman would come down Old York Road. In the foggy morning of October 3, the main body of American troops reached Benjamin Chew's massive stone house, now occupied by determined British troops, and General Knox decided this was too strong a pocket to leave behind in his rear. Precious time was lost with an artillery bombardment, and unfortunately, the flanking troops down the lateral roads were late or did not arrive at all. The forward movement stopped, then the British counter-attacked. Washington was therefore forced to retreat, but he did so in good order. The battle was over, the British had won again.

But maybe not. Washington hadn't routed the British Army or forced them to leave Philadelphia. They did leave the following year, however, and there was meanwhile no great desertion from the Colonial cause. Washington's troops suffered terrible privation and discouragement at Valley Forge, but the crowned heads of Europe didn't know that. For reasons of their own, the French and German monarchs were pondering whether the American rebellion was worth supporting, or whether it would soon collapse in a round of public hangings. From their perspective, the Americans didn't have to win, in fact, it might be useful if they didn't. But if they were spirited and determined, led by a man who was courageous and resolute, their damage to the British interests might be worth what it would cost to support them. The Battle of Germantown can thus be reasonably argued to have been an advancement of colonial goals, even if it could not be called a victory. However, when the news of Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga soon reached them, the European enemies of England decided the colonists would be useful allies.

In Germantown itself, the process of turning a military defeat into a strategic victory soon began, with severe alienation of the German inhabitants against the destructive experiences of British military occupation. After a winter of near starvation, Germantown would never again see itself as the capital city of a large German hinterland. It was on its way to becoming part of the city of Philadelphia.

Espionage in the Revolution

|

| John Nagy |

Both sides fighting the Revolutionary War predominantly spoke English as a native language, so it seemed deceptively simple to pick up a little cash for a tidbit of information or two. John Nagy, who has written several books on spies in the Revolution, recently addressed the Right Angle Club about this interesting topic. According to him, Quakers were favorites as spies because they were widely split in their sympathies, and as pacifists were abundant in the civilian societies of the time. Others have commented that the main difference between Conservatives and Free Quakers was that the Free Quakers were mostly of the artisan class and sympathetic to the Revolution, while the Conservatives were mainly of the merchant class, and Tories. But there were many exceptions, and the plain dress Quakers were hard to tell apart and passed freely through the military lines. No doubt many readers will be incensed by such comments, for which we take absolutely no responsibility.

|

| Beaumarchais |

The one main exception to the English-language generalization were the French, who were still smarting from their defeat in the Seven-Years (French and Indian) War. The playwright Beaumarchais was quite active in the French movement to make trouble for the hated English and seems to have stirred up King Louis XVI to be interested in financing rebel trouble-makers, if not to become active combatants. In any event, a wary King thought it was best to send a spy to look over the situation. As detailed in a little pamphlet called The Spy in Carpenter's Hall the Americans were tipped off about the plot. Accordingly, the spy named Bonvoloir was hidden up on the second floor of Carpenter's Hall, while the colonists put on a belligerent falsified performance on the first floor. It is claimed their performance was a convincing one, having the desired effect of creating a report to the King that the colonists were belligerent, warlike, numerous and united. After the Battles of Trenton and Saratoga, the timing was good for using this sort of report to provoke the King into doing what he was mostly of a mind to do, anyway.

|

| Johann de Kalb |

The French were unusual in favoring aristocrats as spies and Johann de Kalb was anther who snooped around, returning later in the form of General de Kalb of military note. The names of British spies, aside from Major Andre, tended to have a Quaker sound to them, like Dunwoody, Cadwalader Jones and the like. It would take deep research to know whether these were Quaker stalwarts or merely black sheep of some family; there is little doubt that sympathies changed with the changing fortunes of battle. Another feature was the careless lying which took place for propaganda purposes. The famous story of Lydia Darragh, a Quaker who allegedly overheard the British officers plotting the surprise attack on Whitemarsh on December 5, 1777, and walked many miles in the snow to warn Washington -- is apparently a much dressed-up version of what happened. The whole Darragh family was engaged in regular spying, and the evidence is that Lydia's brother William was the one who was the messenger. He apparently carried messages under the cloth covering of the buttons on his coat.

.jpg)

|

| Joseph Galloway |

Two types of spying have a greater ring of authenticity. The British needed pilots to guide their ships up the Delaware past fortifications and obstacles. Maps were nice, but it seemed simpler to enlist the efforts of two ladies of easy virtue, Ms. O'Brien and Ms. McCoy, to hang out in taverns and entice local ship pilots to enlist to guide the British ships into Philadelphia. The British spymasters even had the ingenuity to entice a member of the Continental Congress, Joseph Galloway, to turn over the commentary records from which troop strength could be estimated from the food consumed. It is not recorded whether suitable adjustments were made for starving troops, stolen supplies, or fraudulent charges, however.

|

| Benedict Arnold |

Two prominent officials were accused of selling out the side, but an accusation of this sort is easily made, hard to prove. When the examples of Benedict Arnold and Peggy Chew can be verified, however, there is always doubt cast on everyone which some will believe. The system of double signatures was used, so there were two co-treasurers of the United States, Joseph Hellegas and George Clymer. Letters have been produced indicating that one or the other sold the commissary records. Hellegas' home is still today the residence outside Pottstown of a prominent Philadelphia surgeon, and his portrait appears on the ten-dollar bill. In so doing, he started a tradition of Secretaries of the Treasury on the ten-dollar bill, presently occupied by Alexander Hamilton. George Clymer, for his part, was a signer of the Constitution and a favorite of George Washington. Are these stories true? Who knows, but in an eight-year war, John Nagy has accumulated evidence that there were over five hundred documented spies. The essential question remains one of whether to believe the documents.

Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold: Fallen Idols

|

| General Burgoyne |

After defeating Washington's troops at the battle of Germantown, the British then occupied Philadelphia for the better part of a year. The town was a mess, with food shortages typical of the squalor of any occupying army equalling the existing population. Washington was forced to fall back to the natural fortress of Valley Forge. The city of Philadelphia was not exactly under siege, but it was as difficult a place for British troops to live as a besieged city. For his part, Washington was forced to shiver and starve in the nearby mountain valley, at least consoled by distant news of American achievements. General Burgoyne and his army were soon captured at Saratoga by General Gates under humiliating circumstances. Clearly, the dashing hero of this event had been Benedict Arnold on a white horse leading the charge, getting wounded in the leg in the process.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in Paris |

Benjamin Franklin in Paris trumpeted the news of this victory, reminding the French of Washington's earlier victory at Trenton, and maneuvering it all into a treaty of alliance. With the French fleet in the nearby Caribbean, Philadelphia was no longer a safe place for the British to stay a hundred miles upriver, and the idea of abandoning occupied Philadelphia began to grow. Having gambled on British victory in defiance of London's orders, the Howe brothers were not in a position to argue with new orders. The British soldiers inside the city were more comfortably housed than the American troops outside it, but nobody was exactly comfortable. The American Congress had, of course, fled to the hinterlands. All in all, it suddenly became uncertain who was going to win this war.

|

| Peggy Shippen |

The American population at this time has been described as a one-third rebel, one-third Tory, and one-third trying to hunker down to see who would win. Many of the seriously committed Tories had fled from Philadelphia when the rebels took charge, while pacifist Quakers were a little hard to classify. Generally speaking, the prosperous merchant class had never been persuaded King George was all that bad, while the less prosperous artisans were the fervent patriots. Under such conditions, many people who privately leaned in either direction found it was best to seem non-committal. The British were billeted in private homes; the Officers in the best houses of the merchant class, the common soldiers generally housed in the homes of the artisans. Although the soldiers and the artisans did not mix very well, circumstances permitted the aristocratic officers getting on pretty well with the merchants whose houses they occupied. The girls in the colonial families seemed immediately attractive to the British officers, who were far from home, while the officers also seemed pretty glamorous to the girls. So, it is not exactly surprising that the most beautiful colonial belles like Peggy Shippen and Peggy Chew found themselves frequently in company with dashing officers like Major John Andre. Andre would likely have been a heartthrob in any circumstance since he had risen to the rank of adjutant-general at a young age, wrote poetry and plays, reputedly was rich, and was regularly the life of any party. Nor is it surprising that generations of Peggy's descendants have treasured a lock of his hair.

|

| Margaret Oswald Chew Howard |

When the decision was finally made to abandon Philadelphia, six of the British officers personally contributed twenty-five thousand dollars to throwing Philadelphia's most famous, most splendiferous party, called The Machianza. It went on for days, had real jousting matches between officers dressed like knights in armor, banquets and all that sort of thing. It was Andre's idea, and he was enthusiastically in charge. Surviving records of the event do not show that Peggy Shippen was present, but in view of what happened later, much of her correspondence has been destroyed. It's pretty hard to imagine she wasn't there.

|

| Major General Benedict Arnold |

The British then marched away, and Washington's troops cautiously followed, assuming control of the city. Major General Benedict Arnold had been sent from Saratoga to Valley Forge to recover from his leg wound, and probably also to raise morale among the troops celebrating the now-famous hero. Washington more or less immediately decided to pursue the British across New Jersey, thus leading to the battle of Monmouth as the two armies raced for the Naval vessels in lower New York harbor. Since General Arnold had not fully recovered from his wounds, he was installed as the military governor of a somewhat bedraggled Philadelphia. Naturally, he was the center of the social scene, and soon was pursuing Peggy Shippen in every way he knew, which included some pretty gloppy letters in Romantic style. Peggy's father was uneasy about his intentions but was eventually mollified by Arnold's purchase of the house called Mount Pleasant, now a tourist attraction in Fairmount Park. With this evidence that his prospective son in law was at least likely to stay in Philadelphia, Edward Shippen finally repented of his opposition to the marriage of his daughter. But the new couple were soon off to West Point, where Arnold had kept up a persuasion campaign with George Washington, to get himself appointed the commandant of the main northern defense of the Hudson River. A point for Philadelphian tour guides to remember is that Peggy and Benedict never got a chance to live in Mount Pleasant.