3 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

Tourist Trips Around Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker. He was the largest private landholder in American history. Using explicit directions, comprehensive touring of the Quaker Colonies takes seven full days. Local residents would need a couple dozen one-day trips to get up to speed.

A million college students and visitors annually take up residence in Philadelphia, tend to business, then go home. They hear scraps of history and semi-familiar names, strolling past curious buildings of whose history they know very little. This website is for them, recognizing how ex-residents retain enduring curiosity about these Quaker Colonies, even from great distance. Future visitors can use a weekend guide to the funny city where they find themselves; their affection for the town is likely more enduring than they realize. What's also gratifying is to sense possessive local patriotism by working class Philadelphians, the people who talk about "Philly" instead of "fa-Delf-ya" but are no less owners of the place. Because of their shyness, they seem to prefer history from a single voice, even though multi-voice encyclopedias might contain more precision.

We begin with a five-day tour of the highlights. Within it, there's a one-day walking tour of the center city district, which claims to be America's Most Historic Square Mile. And, one-day driving tours to the North of town where Washington and Howe did battle, and a second one to the Welsh Barony along the Main Line. And a two-day tour, down the Jersey side of Delaware Bay, across the Bay by ferry, home along the southerly, state of Delaware, side. If you never come back again, you've got the essence of it.

But by no means all of it. There's a Sunday excursion along the upper Delaware on the Riverline rail road. A trip up the King's Highway and back down the Jersey coastline of beaches. A ride on the Paoli Local, and the Chestnut Hill Local. House tours, garden tours, architectural tours, and some visits inside the big law firms, the big hospitals, and the many volunteer organizations.

We firmly believe in our Trinity: the Fatherhood of God, the Brotherhood of Man, and, the Neighborhood of Philadelphia. We hope you will, too.

Tours of Philadelphia Region

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Double-Click Your Choice)Five-Day Inclusive Tour:

Day 1: Center City Historical Walking Tour.

Day 2: Northern Loop Motor Tour, New Jersey and Bucks County.

Days 3-4: Land-Sea Tour Around Delaware Bay, New Jersey and Delaware.

Day 5: Motoring Around the Lower Schuylkill Region.

Briefer Local Excursions:

Pennsbury Manor

|

| Fairmount |

William Penn once had his pick of the best home sites in three states, because of course he more or less owned all three (states, that is). Aside from Philadelphia townhouses, he first picked Faire Mount, where the Philadelphia Art Museum now stands. For some reason, he gave up that idea and built Pennsbury, his country estate, across the river from what is now Trenton. It's in the crook of a sharp bend in the river but is rather puzzlingly surrounded by what most of us would call swamps. The estate has been elegantly restored and is visited by hosts of visitors, sometimes two thousand in a day. On other days it is deserted, so it's worth telephoning in advance to plan a trip.

|

| Gasified Garbage |

After World War II, a giant steel plant was placed nearby in Morrisville, thriving on shiploads of iron ore from Labrador, but now closed. Morrisville had a brief flurry of prosperity, now seemingly lost forever. However, as you drive through the area you can see huge recycling and waste disposal plants, and you can tell from the verdant soil heaps that the recycled waste is filling in the swamps. It doesn't take much imagination to foresee swamps turning into lakes surrounded by lawns, on top of which will be many exurban houses. How much of this will be planned communities and how much simply sold off to local developers, surely depends on the decisions of some remote corporate Board of Directors.

However, it's intriguing to imagine the dreams of best-case planners. Radiating from Pennsbury, there are two strips of charming waterfront extending for miles, north to Washingtons Crossing, and West to Bristol. If you arrange for a dozen lakes in the middle of this promontory, surround them with lawns nurtured by recycled waste, you could imagine a resort community, a new city, an upscale exurban paradise, or all three combined. It's sad to think that whether this happens here or on the comparable New Jersey side of the river depends on state taxes. Inevitably, that means that lobbying and corruption will rule the day and the pace of progress.

Meanwhile, take a trip from Washingtons Crossing to Bristol, by way of Pennsbury. It can be done in an hour, plus an extra hour or so to tour Penn's mansion if the school kids aren't there. Add a tour of Bristol to make it a morning, and some tours of the remaining riverbank mansions, to make a day of it.

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |

Although Germantown Avenue has wandered northwestward from this uncertain beginning for over 300 years, up to the rising slope of the town toward Broad Street, it is now rather difficult to make out anything but industrial slum along its path which could be called historic. There is hardly any structure standing which has a colonial shape, and no Flemish bond brickwork is seen in the tumble-down buildings. When with the relief you finally approach Temple University Medical Center at Broad Street, the Fair Hill cemetery does show some effort at preservation, and a sign says that Lucretia Mott is buried there. But that's about all you could photograph without provoking suspicious stares. Here's the first of four segments of Germantown Ave., and it's a pretty sorry sight.

|

| Chew Mansion |

Crossing Broad Street, the busy intersection suggests 19th Century prosperity in its past, and on the west side of Broad, you can start to see signs of historic houses, either in colonial brickwork or grey fieldstone. The road gets steeper as you go west past Mt. Airy, where it almost brings tears to the eyes to see brave remnants of another time. George Washington lived here for a while, and the Wisters, Allens, and Chews; Grumblethorp and Wyck. The huge stone pile of the Chew Mansion glares at the imposing Upsala mansion, where British and Americans lobbed artillery at each other during the Battle of Germantown. Benjamin Chew the Chief Justice built this house as a summer retreat, to get away from Yellow Fever and such, and started the first migration to the leafy suburbs. His main house was on 3rd Street in Society Hill, next to the Powels and where George Washington stayed. At the peak of the hill in Chestnut Hill, a suburb within the city. Germantown Avenue rather abruptly goes from the relics of Germantown to the charming elegance of Chestnut Hill, but during a recession, it frays a little even there. At the very top is the mansion of the Stroud family, now in the hands of non-profits; across the road in Chestnut Hill Hospital, once the domain of the Vaux family. Then down the hill to Whitemarsh, where the British once tried to make a surprise raid on Washington's army. As you cross the county line into Montgomery County, it's conventional to start calling the Avenue, Germantown Pike. Germantown Pike was in fact created in 1687 by the Provincial government as a cart road from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. Farmers used to pay off their taxes by laboring on the dirt road, at 80 cents a day. Germantown Pike, Ridge Pike, Skippack Pike, Lancaster Pike, and others are a local reminder that Pennsylvania was always the center of turnpike popularity; that's how we thought roads should be paid for. The present governor (Rendell) hopes to sell off some better-paying turnpikes to the Arabs and Orientals, possibly imitating Rockefeller Center by buying them back and reselling them several times by outguessing the business cycle. Parenthetically, the Finance Director of another state at a cocktail party recently snarled that the purpose of privatizing state infrastructure was not to raise revenue, but to provide collateral for more state borrowing. He wasn't at a tea party, but he may soon find himself there.

From a modern perspective, the third segment of the Germantown road runs from Chestnut Hill to Plymouth Meeting, with lovely farmhouses getting swallowed up by intervening, possibly intrusive, exurbia. The township of Plymouth Meeting is a hundred years older than Montgomery County, having been built to be near a natural ford in the Schuylkill River. Norristown, a little downstream, is the first fordable point on the Schuylkill, with Pottstown making a third. Plymouth's colonial character survived a period of industrialization based on local iron and limestone, and has established several prominent schools for the surrounding area. But the construction of a substantial highway bridge attracted a large and busy shopping center. The shopping center looks as though it will eradicate the quaint historical atmosphere more effectively than industrialization ever could.

The fourth and final segment of Germantown Pike starts at the Schuylkill and goes over rolling countryside to its final destination at Perkiomenville, where it joins Ridge Pike at the edge of the Perkiomen Creek. That's an Indian name, originally Pahkehoma. Perkiomenville Tavern claims to be the oldest inn in America, although that honor is contested by another one along the Hudson River near Hyde Park. The WPA during the Great Depression constructed a large park along the Perkiomen Creek for several thousand acres of camping and fishing, so Perkiomenville has several large roadhouse restaurants and antique auctions for bored wives of the fishermen. In the V where Ridge Pike and Germantown Pike come together, a dozen or more colonial houses are tucked away in a town called Evansburg. This formerly Mennonite terminus of Germantown Pike obviously still has a lot of charm potential, and its local inhabitants are very proud of the place. But it's easy to zip past without noticing the area, which includes an 8-arch stone bridge, said shyly to be the oldest in the country. It's hard to know whether you wish more people would visit and appreciate; or whether you are happy that obscurity might permit it to survive another century or so.

|

| Chestnut Hill Hospital |

The name change of the Germantown road from Avenue to Pike is probably not precisely where the turnpike began, but it is now notable for some pretty imposing mansions, standing between the humble and even somewhat dangerous slums along Delaware, and the charmingly humble but well-preserved Mennonite villages, at the other end. It is arresting to consider the two ends, whose houses were built at the same time; only the Mennonites endure. Somewhere just beyond the Chestnut Hill mansions is an invisible line. West of that point, when you say you are going to town, you mean Pottstown. When you say you are going to the City, you mean Reading. And as for Philadelphia, well, you went there once or twice when you were young.

Central Pennsylvania Settlers Before 1700

|

| German Rhineland |

Dates are unclear, but twenty-five families from the German Rhineland bought Pennsylvania land from William Penn prior to 1700, which is the earliest recognizable date on a gravestone in the Hummelstown Cemetery. Future research may narrow that time interval down, but it can confidently be said they got on a sailing ship bound for Philadelphia between 1682 and 1699. For reasons also unknown, tradition relates the Captain refused to stop in Philadelphia, putting them off in New York. They discovered they were unwelcome among the Dutch settlers in New York, who quite likely reflected the ancient hostility between the Dutch at the mouth of the Rhine River, and the Germans living upstream from there. Augmented by wars and invasions, the feeling persists to some degree even today. The twenty-five families sailed from New York, up to the Hudson River to Kingston the state capital, where they discovered they were even more unwelcome. The British under the command of the Duke of York took over New Amsterdam in 1664, but Dutch cultural control persisted long after the change of political control.

|

| Governor Keith of Pennsylvania |

Tradition continues that Governor Keith of Pennsylvania happened to be in Kingston at the time of the stranding of the migrants. He suggested they travel eighty miles overland to the Susquehanna River and then float down to land where topsoil was reputed to be several feet thick. Since Dutchmen everywhere concentrated on fur trading more than farming, it seems safe to guess reliable guides were easily found in Kingston. From there to what later became famous as Three-Mile Island below Harrisburg, the three-hundred-mile route of these pilgrims can be guessed by following valleys between towering ridges. Unfortunately for this surmise, there are two main canyons leading to Kingston from the Susquehanna, which improved Kingston as a choice for fur trading. The more northerly canyon is somewhat longer, but it might have been safer; perhaps the German pilgrims just flipped a coin. Taking either choice it's a hard trip however, even assuming the Indians were friendly and food sources abundant. It must have required at least a month to go the full distance to what is now Harrisburg, passing by a number of places which now support prosperous farms. That potential likely provoked demands of some travelers that they had gone far enough, as kids do today in the back of the station wagon. By luck or stubbornness, however, they kept right on into the wilderness, eventually making permanent settlements along the Swatara Creek in Dauphin County, which proves to have the richest farmland in America. Middletown and Hummelstown are thus the two oldest settlements in Central Pennsylvania. By the time the other German sects made their way up Germantown Avenue, out Germantown Pike, and then onward to the Great Valley beside Blue Mountain, the original settlers had ample time to discover the best land, the surest wells, and the best access to the creeks. Furthermore, they had several generations to notice which families produced the strongest lads, and which families were the best natural farmers. Since later incoming families were mostly penniless, they had to settle for less advantageous farmland and less endowed marriage partners. Dominance by the original farming families continued until the early Twentieth century when it became prestigious to enter one of the professions. Or even to move away from the Dutch Country and go to the city.

|

| Dutch Ships |

Getting back to their days in Kingston, it is not easy to tell what route they took, judging only from a highway map. We look for the largest towns and then the shortest highway route, but it seems likely Kingston was chosen as a trading center because it was the place where the fur traders brought their pelts to the Dutch ships on the Hudson. The roads chose the towns, not the other way. When you observe the valley beginning at Kingston, there remains little doubt the route to Harrisburg must have led that way. The local folks at the museums and stores of Kingston can't help; they never heard of any such migration, and most of them never had reason to travel in that direction. Kingston was burned to the ground (by the British) in 1777, the state capital moved to Albany, and the economic center went south to New York City. Kingston is just a nice little town on the Hudson, across the river from where rich folks put their mansions, and liberal-minded folks send their children to Bard College, a place where no two buildings follow the same architectural style.

So when you go West from that nice little town, it is only a mile or two before you are out in the woods, with farms here and there, and scattered cabins which look like fishing and hunting "lodges". There's a creek in the bottom of the valley, and if you look up, you see the road merely winds its way between parallel mountain ridges. Perhaps a glacier carved out this trail, perhaps a mighty river once ran there, perhaps volcanic action tented up and cracked. Anyway, you are not going to get lost if you follow the creek, going steadily uphill from Kingston for twenty or thirty miles. If this were a single mountain ridge, you would be approaching either a water gap or a wind gap. A wind gap is a water gap that has lost its river at the top.

|

| The Rhine River |

What's at the summit is not a notch, however, it's a bowl. Out of this bowl flow the three main rivers of the eastern seaboard, the Hudson, Delaware, and the Susquehanna. The effect resembles what is said of Switzerland: The Rhine, the Rhone, Danube, and Po; They rise in the Alps, and away they go. The highway from Kingston runs along a creek which flows into the Hudson. At the top of the bowl are some nice dairy farms scattered along ten miles which drain into Delaware. The East Branch and the West Branch of the Delaware River are scarcely more than creeks at this point. At Delhi and Andes there is a further rise in the mountains, and then along twisting decline as you follow a branch of the Susquehanna down to its junction at Oneonta. As you cross the top of the ten-mile mesa you have perceived the answer to a natural question: how did those German families get across the big wide Delaware River that runs between Kingston on the Hudson -- and Cooperstown, where the Susquehanna begins? The answer is pretty evident. Delaware, while a mile wide at Philadelphia, narrows down to two little creeks on this mountain plateau. The Susquehanna system on one side and Hudson on the other have swallowed up the Delaware watershed between them. This might well have seemed a nice place for the German settlers to set up a few dairy farms, but it probably was an even more ideal place for the Iroquois to set up headquarters. Their favorite style of warfare was to occupy the high ground and make lightning raids (or quick escapes) on canoes down the various rivers starting from their origins. If it's of any interest, Charles Evans Hughes began his law practice in Delhi, and a lot of the town boys were killed at the battle of Antietam, thus illustrating the unwisdom of recruiting whole towns into regiments.

Down the mountain we go, into the broad Susquehanna valley. It was probably troublesome to manage wagons down a mountainside. But from here on the German families could stop walking, and float.

Fort Washington, PA

|

| British Campaigns |

The Revolutionary War lasted eight years, so there are a half dozen Fort Washingtons, in several states. Pennsylvania's Fort Washington gets free advertising from being a stop on the Pennsylvania Turnpike at the intersection of the East-West branch and the North-South branch, near some very large shopping malls. Nevertheless, the suburbs haven't reached it yet, and it is on a series of wooded mountain ridges discouraging housing development. Another way of describing its location is that it is several miles north of Chestnut Hill along the Bethlehem Pike, a road which begins in the center of Chestnut Hill at Germantown Avenue. The Pike is quite old, with many surviving colonial-era houses and inns to liven up the trip.

A third way to describe Fort Washington is that the headquarters were at the point where Bethlehem Pike crosses the Wissahickon Creek. How's that again? How does the western Wissahickon Creek then flow uphill to Chestnut Hill? Of course, it doesn't, but the appearance takes some explaining. The northwestern end of Philadelphia is reached by two ancient roads running on ridges quite close together like the split tail of a fish. Germantown Avenue runs up one ridge, and Ridge Avenue runs up the second ridge closer to the Schuylkill. The Wissahickon runs in the gully between these two ridges and tumbles down the hill at Wissahickon Avenue, or Rittenhousetown if that is more understandable. The ridge of Ridge Avenue is essentially cut off by the creek, but engineers have put Ridge Avenue on a high arching bridge as it crosses the creek far below, and by this magic Ridge Avenue and Germantown Avenue are at about the same height most of the way. The Wissahickon Creek is really running downhill the whole way, but sort of disappears from sight and reappears as it twists through the gorges, misleading the casual visitor (or commuter). As happened so often during the Revolutionary War, Washington showed his understanding here of geography in the service of guerrilla warfare.

Since the British were headquartered in Germantown, and the Americans have camped a few miles away on the same creek, it was inevitable there would be some sort of battle in the region. Washington launched a three-pronged attack on the British soon after arriving at Fort Washington, but his troops fired at each other in the fog, and apparently, two prongs more or less got lost in the gorges. The Americans retreated, and the British consolidated their conquest of Philadelphia. They did launch one surprise attack on the American encampment (the Battle of Whitemarsh), but that was mainly a reconnoiter, given up after a few days when it became clear Washington's troops held the high ground. It really is high ground (hawk-watching platforms and all) for reasons already stated. Chestnut Hill is a pinnacle sticking up on the west side of the Creek, with the Wissahickon snaking around its base.

This really was a perfect place for Washington to aim for after the Brandywine Battle, close enough to threaten the British, located in a bowl-like valley for camping, but terminating at the top of a mountain ridge in case the British counter-attacked. And with plenty of running water from the Wissahickon. However, it was a little too close for comfort, and he withdrew across the Schuylkill into Valley Forge as a more substantial natural fortress. Valley Forge is also on a hilltop, but one sitting in the middle of the Great Valley (Route 202 to Wilmington), as the center of an angel food cake tin. No doubt, the advantages of this new location became evident to him at the earlier skirmishes of the Battle of the Clouds, and the Paoli Massacre, which occurred nearby.

In retrospect, these maneuvers and skirmishes were of little military significance, except for the major Battle of Brandywine. The lost opportunity was the chance to catch the British Army without supplies or access to the Navy, aborted by what was probably a hurricane, the so-called Battle of the Clouds. Philadelphia was lost, and the opportunity to win the war early by smashing a third British army was gone for good. The defeat of the Hessians at Trenton, the loss of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga, and a victory on the outskirts of Philadelphia might together just have finished the War. But things didn't work out, the British similarly missed some opportunities, and the war was to last another five years. Once the French allied themselves, their wealth and naval strength tended to make French priorities dominate strategy.

Nevertheless, a perfectly splendid tourist trip awaits the history buff who travels from Elkton, Maryland, where the British landed, to the Battle of Brandywine battlefield, up the Great Valley to Immaculata University where the Battle of the Clouds took place, over to the Battlefield of the Paoli Massacre, crossing the Schuylkill and going to Whitemarsh, then to Fort Washington, and back up Bethlehem Pike to Germantown Avenue, and down to the Chew Mansion. The campaign for the conquest of Philadelphia ended with the fall of Ft. Mifflin when the British fleet was finally able to re-supply Howe's army. This direct auto tour is a little out of chronological sequence, but it can be done in one day if you don't dawdle. If you slow down and spend an extra day, you can include the Moland House where Washington waited to see where General Howe was going. At the right season, there's hawk watching on the ridge at Fort Washington Park, and maybe on to Trenton, or even up the New Jersey waist to Perth Amboy on lower New York Bay, where the Howe brothers began and ended their Philadelphia adventure. That would take you past Princeton and New Brunswick, or even include a trip to the Monmouth Battleground. With this extension, you have traveled much of the extent of the Revolutionary War in the Mid-Atlantic states.

Conowingo

|

| Conowingo Dam |

IT was once a major hazard of travel between Philadelphia and Virginia, to cross the Susquehanna River along the way. The river is wide at the top of Chesapeake Bay, and the cliffs are high on both sides. Consequently, the cute little towns of Port Deposit and Havre de Grace grew up as places to stay in inns overnight, perhaps to throw a line into the water and catch your breakfast. Today, these little towns can be seen to have millions of dollars worth of cabin cruisers and sailboats at anchor, at least during certain seasons of the year. In 1928 the Conowingo Dam was built about ten miles north of the mouth of the river in order to harness the water power, and the Philadelphia Electric Company put a power station there as part of the dam, to generate electricity for Philadelphia. It doesn't seem so long ago, but it gave a mighty boost to the electrification of Philadelphia and its industries at the end of its industrial decline from 1900 to 1929. Unfortunately, competitive forms of power generation have now reduced the dam's output of electric power to periodic bursts during the day, and Philadelphia no longer enjoys a reliable cheap water-powered electricity advantage. Coal and nuclear came along, and now shale gas looks like the coming future.

|

| Bald Eagle Fishing |

Although water power could be claimed to be not merely cheap but environmentally friendly, the unvarnished fact is fish get caught in the turbines and rather chewed up by being sucked from the tranquil lake on the upside, emerging at the bottom as a diced fresh fish salad. That attracts seagulls and other fish lovers to the base of the dam. Some fish escape the meat grinder and merely are stunned by the experience, floating downstream to be attractive to eagles, turkey vultures, hawks, and owls. The consequence is that many thousands of gulls sit on the downside of the dam, while hundreds of turkey vultures and eagles sit on the higher levels of the power generation apparatus. And hundreds of bird-watching nature lovers stand on the southern shore below the dam, poised with many thousands of dollars worth of camera equipment and binoculars. If you don't have a pair of binoculars, your visit there will certainly be substandard. Lots of fishermen are there, too, but depending on the waves of spawning fish at different seasons of the year; shad is particularly favored. You can now begin to see the prosperity of Port Deposit and Havre de Grace has a wider variety of attractiveness than merely sailboating and crabbing. There is, however, a large and ominous yellow warning sign.

The sign says you are standing on a riverbank where the water can suddenly rise without warning; if the red lights start blinking and the warning siren starts honking, immediately gather up your tripods and head for higher land. It looks pretty peaceful, however, and the people with tripods are mostly chatting happily with their friends. It can be pointed out, however, that about two hundred bald eagles are perched on the superstructures roundabout. Cameras are mostly digital these days, attached to the rear of a telescopic lens three feet long, and when they shoot bursts of exposures they sound like a machine gun. So, the bird photographers follow a swooping eagle eagerly, shooting away and hoping to catch the bird in an attractive pose, throwing away the rest of the pictures. Good shots are called "keepers", which the photographer is happy to show onlookers on the rear view screen of the camera/machine gun. More sedate bird watchers carry binoculars made in Germany or Switzerland, which cost thousands of dollars and produce really spectacular images. It's unclear whether all this expenditure is worth it, but there is little doubt in the bird lovers' minds you are wasting significant parts of the trip without some kind of binocular.

Suddenly, ye gods, the lights start to flash and the siren starts to honk loudly. Not knowing exactly what to expect, first-time visitors head for the hills. The old-timers with a Gatling gun on a tripod are much more casual, picking up their apparatus and scuttling several feet up the river bank. The birds seem to know what the signals mean, scramble into the air, or start to arrive from far perches. The electric company seems to have received a notice that more electric power generation is needed, so the gates at the bottom of the dam are lifted and water gushes forth; the water does indeed rise rather rapidly. The birds divide themselves into two groups: the gulls' circle in a thick spiral at the base of the dam, while the eagles and vultures circle independently in a second spiral, several hundred yards below the dam. One group looks for fish salad, and the other group prefers stunned whole fish. Photographers however much prefer the eagles downstream, circling and then swooping to the water's surface to grab a wiggling fish and running off with it. Some of the bigger bullies prefer to let others do the fishing, simply swooping to steal the fish. Ratta-tap-ratty tap goes the digitals. After twenty minutes it is all over, and the birds seem to realize it before the water stops gushing into geysers. The river recedes, birds go back to their perches, and quiet again rules the land.

On the way home, you notice something you perhaps should have known. Interstate 95 takes people speeding down the turnpike, just out of sight of the dam. You get there quicker, but don't see the sights. Coming back from the bird watching parking area which the electric company provides, you are more or less compelled to recognize that U.S. highway Number One goes right across the top of the dam, up to the hill and over the charming rolling countryside. Back to Philadelphia.

Main Line: Overbrook to Paoli

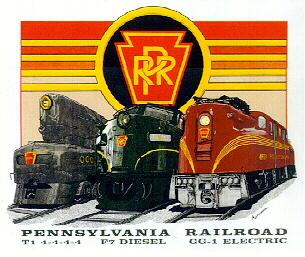

|

| Alexander Cassatt |

Greg Pritchard, who has made scholarship of the Main Line a central part of his life, recently addressed a meeting of the Right Angle Club. To Greg, the Main Line is the set of commuter rail stops from Overbrook to Paoli, representing what was once the heart of the Pennsylvania RR. It changed into a spur of the real main line, running from New York to Chicago, the central monument left by Alexander Cassatt, its president. Times really do change a lot. There is now only one dingy daily passenger train from New York to Harrisburg, which Amtrak would dearly like to eliminate entirely. The Pennsylvania Turnpike was just too much competition, and air travel has eliminated all railroad passenger interest in further points like Pittsburgh, Chicago, and points west. The real main line of long-distance rail on the East Coast now runs north-south, called the Northeast Corridor, essentially beginning in Boston and ending at Washington DC. Philadelphia is central to all of these versions of main lines, although a thirteen-year lawsuit was required to break combined Pennsylvania and New York Central railroads into SEPTA, Amtrak, and Conrail. At the moment, Conrail the freight line is making tons of money, Amtrak the passenger long-haul line would soon die without government subsidy, and all commuter railroads are subsidized by their local communities. There is a lot of talk about billion dollar investments in high-speed trains like they have in Japan and France, but anyone familiar with the economics of rail transportation just shudders at the thought. Railroads are profitable ways to haul long-range bulk cargo. Passenger lines, long and short, can only be justified if they cost less than expanding highway and airline transportation, which the public obviously prefers. Philadelphia is in the peculiar position that the real estate investment has already been made in passenger rail; is it cheaper to build on what already exists, or is that a doomed relic of the past?

But back to Greg's favorite topic, the revered and treasured 19th Century stations on The Main Line. They were mostly built from 1860 to 1890, along the path of what was then the main line to Chicago, but destined to become a spur leading to the real center of east-west traffic, which went from New York to Chicago further north from Philadelphia, intersecting with what became the Philadelphia spur at Paoli. In the days when Philadelphia was one of the richest cities in the world, the spur was a glamorous suburban real estate development. The stations were built, the mansions scattered along at some distance, and servants houses clustered around the stations. The towns were renamed with Welsh names like Bryn Mawr (instead of Humphryville). A culture was built up, probably unique in the world for being centered on railroad executives, and novels like Kitty Foyle and movies like The Philadelphia Story celebrated the glamor of it all. It's probably true that you can find more fifty-room mansions there than just about anywhere else, but the automobile and good public schools mainly drove the prosperity of the 20th Century, as the railroads dwindled away.

|

| Bryn Mawr College |

The stops on the Main Line begin with Overbrook and continue on through Merion, Narberth, Wynnewood, Ardmore, Haverford, Bryn Mawr, Rosemont, Villanova, Radnor, St. David's, Wayne, Strafford, Devon, Berwin, Daylesford, and Paoli. The main line starts where Philadelphia taxes end and gets progressively newer in harness with the gradual construction of fashionable homes as you get further from the city. At first, Paoli was a place where the out of service trains was stored, but gradually became a fashionable area, which is beginning to leapfrog over the King of Prussia shopping center into the farmlands to the north. The center of gravity of suburban aspirations moves steadily further into the surrounding countryside but is outgrowing the old commuter rail system, and there is something of a movement back to the city. That is to say, urban sprawl is running into the discovery that it's just too traffic-jammed to commute that far, except by train. Most folks are familiar with the jingle that "Old Maids Never Wed And Have Babies" which is supposed to help commuters remember what stop they are approaching. However, the topic mentioned by the jingle and the fact that it ends with Babies (Bryn Mawr) instead of Paoli, strongly implies it was written by a student at Bryn Mawr College for Women.

|

| Centennial Exhibition in Fairmount Park |

The old brick stations have been adopted by affectionate commuters, turned into historical preservation societies. They have a varied history, but quite often the station master lived upstairs, and the first floor housed a branch of the post office. When the railroad straightens out its right of way, the stations have to be moved, often at great expense. As they progressed further into the countryside, sometimes grand resort hotels were built for those who wanted to escape the summer heat in the city, or in 1876, to house attendees to the Centennial Exhibition in Fairmount Park. As these hotels lost popularity, they became excellent bargain real estate for a new college, to begin with, a lessened expense, and the upscale neighborhood which soon clustered about the area insisted, that these colleges move up-scale and get good ratings in U.S. News and World Report. Alexander Cassatt insisted that all transcontinental trains must make a stop in Paoli near his home, and there are even a few stations like Upton which were for the sole use of a single estate. So, at one time when ignorant non-Philadelphians on the transcontinental trains would sniff, "Why would the trains all stop out here in the country?", the Philadelphians in the know would just bury themselves in their newspapers.

Footnote: This interesting talk stimulated me to go read some of the history posted in the Main Line station houses, and in particular the one in Narberth. Narberth was a village long before the railroad came along, and it still holds itself a little aloof from the rest. These and similar places relate that Narberth used to be Libertyville, Bryn Mawr used to be Humphrysville, Cynwyd was once Academyville, Marionville became Merion, and Narberth was purchased from William Penn in 1682 by Edward Reese Price. It is also noted that William Thomas donated his property to the PRR in 1851, and the PRR purchased the struggling "Old Columbia" railroad, formerly the "MainLine of Railroads and Canals", from the state in 1857. Narberth quickly became the center of fashionable summer hotels.

Philadelphia to Savannah: A New View

Bob Reinecke and I recently took a trip by boat down the inland waterway to Savannah. There isn't time to recite all the details, but four or five real surprises popped up, and maybe there is time to talk about them.

The first discovery was an accident of my visiting my daughter in Northern Virginia, and discovering there is no direct train service to Williamsburg. It's only once a day, each way, but it is direct from 30th Street Station to the train station about a hundred yards from the hotel in Williamsburg. Actually, it starts in Boston and goes to the Portsmouth Naval Base, branching off at Richmond toward the banking centers of Charlotte, North Carolina. But Williamsburg is about the only tourist destination in Virginia if you haven't been paying attention, while 30th Street is about the only place to take a train, right? We had a lot to learn.

A travel brochure announced there was a cruise boat of about a hundred passengers, which leaves Richmond, goes down the James River, and then heads south on the Inland Waterway, making stops along the way until it ends up in Savannah, Georgia. On this particular trip, there was a busload taking tours of Revolutionary history, and a second one taking Civil War excursions at every stop, take your pick. Most people took the Civil War choices, but the lecturers were both excellent, and it pretty much turned into two tours on a single boat. We learned the hard way that the only train to Richmond gets there after the boat has already departed, so it was necessary to arrive a day early and stay in a hotel. We were certainly glad we did because Richmond is having a revival since the devastation of the Civil War. A dozen hotels and restaurants cluster around the train station, which is a few blocks from the renovated Capitol, sitting on top of a hill. The hill has been extensively undermined and turned into a pretty elaborate museum, well worth a two-hour visit if you get there at the right hours. Not far away is a perfectly spectacular art museum, apparently donated by Paul Mellon, and well worth a four-hour visit. Paul Mellon has also donated his huge collection of British Art to the Yale Museum, and of course, the Mellon Gallery in Washington was largely given by his father. The Mellons of Pittsburgh may well have been pretty tough bankers, but in the art world, they certainly knew their stuff. Even if the Virginia museum didn't contain a single painting, the building itself would be worth a trip to visit.

Richmond also has a secret treasure in the James River. A century ago, every major river on the East Coast would have a major run of spawning shad fish, about the middle of April. One by one, the rivers were dammed up at the "fall line" and industrial pollution put an end to the shad run. That was probably also getting to be true at Richmond until General Grant and his army put an end to industrialization. For whatever reason, Richmond is the only major city on a river that still has a spring shad run. Since the river runs through the center of town, the big problem for fishermen is to find a boat to rent, and this spring event is largely forgotten. Four or five big restaurants were pointed out as specializing in seafood, but although I called them all, none of them knew what a shad is.

When you go down to where the tourist boat docks, however, you soon find the local teen-aged boys know all about shad, and a hundred or more of them line the banks with their fishing gear. As you might expect, fishing is best toward dusk in the evening, and around dawn in the morning. Unfortunately, we were late. The boys were all pulling in strings of six or eight fish on a line, but they were uniformly small ones. The big fish spend all winter in the Bay of Fundy, and return to the river where they were born, to spawn again. So the big fellows, the fish that were supposed to have rescued George Washington at Valley Forge, had already gone upstream to spawn, and all that was available to the teenagers were young fry, trying to return down the river toward the Bay of Fundy. Incidentally, although the Hudson River has also pretty much lost its industrialization, there is no shad run on the Hudson. The explanation seems to be that the striped bass congregates along the abandoned piers on the New York waterfront, and devour the shad fingerlings on their way out to sea. In Philadelphia, it seems to be the refineries at Marcus Hook that give the shad their fatal problem.

So off we sail from Richmond, making the first stop at the mansions along the James River. Of particular interest is the splendid mansion of William Henry Harrison, of Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too. You know, the fellow who won election to the Presidency by advertising he had been born in a log cabin. Off down the James River, where two more surprises await the callow Philadelphia visitor. We knew about Williamsburg, but it was a surprise to find that both Jamestown and Yorktown have been restored within an inch of their lives, each one just as interesting as Williamsburg. The woods surrounding these three colonial villages are manicured and painted, filled with an incredible number of retired military. As you tour the area in buses, it becomes clear that almost the entire peninsula between the James and York Rivers is filled with military reservations of various sorts, Air Force, Naval, Marine, and at least two hush-hush CIA establishments. This is what Generals Grant and McClellan fought over as the "wilderness", attempting to take Richmond from the rear. If you add to this military complex the huge establishment of government contractors neighboring Washington, it is easy to see why the demographics and politics of the Old Dominion are rapidly changing.

One of the military retirement villages in the area is Fort Monroe, on an island in the mouth of the Chesapeake. Like Pea Patch Island in the Delaware, and Fort Sumpter to the south, this fort was constructed after the War of 1812 as one of a chain of defenses for the Atlantic Coast. It once housed President Jefferson Davis as a prisoner after the Civil War, and the house where Lincoln stayed is proudly on display. It looks like a really nice place for a retired Colonel to live if he enjoys sailing and fishing. Nearby, both the Merrimac and the Monitor are under reconstruction as museums, together with the museums which display how naval warfare was completely transformed by two iron boats in a single afternoon.

So off down the Inland Waterway on a ship that scraped bottom a couple of times on the previous journey. Because of our maritime unions, only a ship that has been constructed in America is allowed to sail between two American ports, and only American employees are allowed. That makes for scarcity, and although it is pleasant to be surrounded by a thoroughly American crew, it makes this sort of cruising expensive. But the sense of American history is heightened, as you go past towns that were burned by the British, and gardens that were planted by members of the Continental Congress. Particularly Beaufort, which General Sherman decided was too beautiful to burn. You can walk the side streets of Charleston, where "Porgy and Bess" was portrayed, and imagine you see the bombardment of Fort Sumpter. Savannah, the fictional home of Rhett Butler the blockade runner in "Gone with the Wind", the home port of Revolutionary blockade runners, the site of smugglers for prohibition days -- affects an atmosphere of decay and decadence which air conditioning has rendered obsolete, but still attracts tourists looking for a thrill.

And so we ended the trip as we began it, by telling the local guides a thing or two. It was thirty miles north of Savannah on the Savannah River, that our famous Philadelphia river expert, Ruth Patrick, advised the President of DuPont to place the manufacturing center for the hydrogen bomb. She lived to be one hundred five years old, and the building which bears her name can still make bombs as needed. And not one guide or employee of that ship, or resident of that town, had ever heard of her.

At Times, Charles Dickens Was a Little Immature

|

| Eastern State Penitentiary Aerial View |

Every once in a while, Philadelphia needs to be reminded of its Quaker origins, and the surprising number of people who will suddenly make an appearance to defend Quaker ideas. It would appear that Philadelphia needs to be reminded that Quakers see a value, even a joy, in silence. The present entrepreneurs in charge of Eastern State Penitentiary, presently a Hallowe'en showplace, are to be congratulated for rehabilitating a neighborhood formerly in decay. If you are looking for a collection of exotic restaurants after visiting the neighborhood art museums, this is the place to go. But I do wish somebody would put an end to the myth that silence and solitary confinement can drive you crazy because I don't believe they will.

Every Quaker family has to handle the problem that children don't naturally like to sit still. The first few times Quaker children are brought to meet, the kids have to be shushed, given books to read, and eventually be led out early to sit in the First-Day (Sunday school) classrooms, while their parents go back to the meeting room to sit in silence. Some kids get the message quicker than others, and the ones who keep misbehaving in meeting eventually have to face general disapproval as "spoiled" until they either quiet down or get sent to boarding school. So Quakers are familiar with the problem, learn how to deal with it, and tend to regard resistance to silence as a sign of immaturity.

|

| Charles Dickens |

Charles Dickens was once a newspaper reporter in Philadelphia and wrote many ecstatic articles about the city. However, he was paid by the word, and prospered mightily from some unnecessarily long articles directed to the folks back in England. One of them was a description of Eastern Penitentiary, built on the principle of the rehabilitation of criminal behavior by long periods of solitude, remote from distracting criminal influences in the community at large. The idea, which may well have originated with Dr. Benjamin Rush, later called the father of American Psychiatry, was widely imitated. There soon were over three hundred prisons throughout the world, dedicated to the idea and imitating the architecture. Whether he believed it or not, Dickens wrote a long, long, diatribe against the concept of solitude as rehabilitating, in which he imagined himself in the position of the poor prisoner, and declaring it would drive him crazy. Without much argument, Charles Dickens was responsible for the shift in public attitudes which eventually led the Board of Prisons to decide to tear it down. This was not exactly evidence-based psychiatric reasoning since a great many crazy people get sent to prison anyway. It isn't surprising that lots of crazy people were found in Eastern Penitentiary, but it isn't exactly proven that solitary confinement made them into lunatics. In fact, it isn't being based on evidence to claim that either the outcome of recidivism or the outcome of improved behavior is influenced by any form of incarceration, with or without corporal punishment, with or without capital punishment. It is definitely proven that incarceration is as expensive as psychiatric treatment, but that isn't saying a great deal. You can definitely cause temporary insanity with prolonged sleep deprivation, but you would suppose that solitary confinement would increase the amount of sleep, not reduce it.

When the time came to demolish Eastern Penitentiary, the Board of Prisons was advised it was so solidly constructed it was simply too expensive to tear it down. As the neighborhood gentrified, real estate values rose, but never enough to justify the demolition of what was essentially a fortress. Even the relentless forces of decay have continued to be slower than the rise of rising in the price of the land. It's like those medieval castles still standing in Europe, occasionally attracting some American billionaire, but mostly just hollow shells. The deterioration on the interior is apt to go faster than deterioration of those stone walls, so the cells formerly occupied by Willie Sutton and Al Capone will need restoration sooner than the towers and parapets. But driving people crazy? It's doubtful. Its function was mostly to segregate the criminal elements of each succeeding wave of immigrants, as a quick review of the surnames of inmates easily demonstrates.>/p>

Bring Your Own Hammer

Stonehenge in England is a ring of big stones standing on the edge, but only recently has it been discovered that they chime when you hit them with a hammer. The British didn't discover the phenomenon, however. Long ago the Quakers of Pennsylvania knew they had ringing rocks in a moraine dumped at the edge of a receded glacier in Bucks County. The County has made it a recreation park which is mostly deserted, except when a drove of cars appears, bearing dozens of Cub Scouts or other excursionists.

|

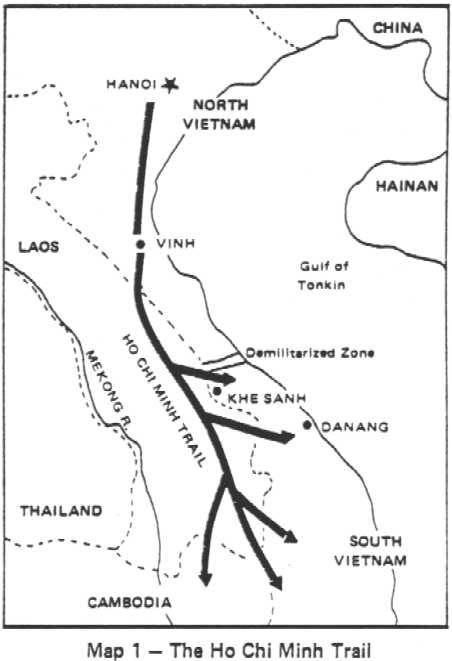

| Ho Chi Minh Trail |

Just what makes these boulders chime when you hit them with a hammer, isn't entirely clear. It's certainly a good topic for a geologist to use for a thesis, but right now none of the visitors to the park cares very much. It can easily be seen that the moraine marks the edge of the fertile plain surrounding Philadelphia, to the north of which the ground breaks up and has mining as its main industry. The farms suddenly become smaller and less prosperous on the moraine plateau, and fancy exurban restaurants yield place to auto dumps and parks of pickup trucks. In certain seasons, it is possible to imagine the gun racks above the front seats. Some of the areas suit itself for summer cottages in the hot weather, usually close to a stream or lake. This is the area where the Shenandoah Valley extended, narrowing down to the Delaware Water Gap. George Washington didn't just cross Delaware once near here, it was a sort of a Ho Chi Minh Trail out of reach of the British Fleet during the Revolutionary War. The main arsenal of the Revolution was in Reading. The valley meets what used to be an industrial area along Delaware, coming up from Philadelphia. Before that, the Seneca Indians had made it their headquarters, and after that, people like Stephen Girard discovered and exploited the minerals once exposed by the glaciers to the north. There's a "wind gap" (cleft in the mountain without water at the relatively high base), and the water gap. William Penn terminated his line separating East from West Jersey at Dingman's Ferry within this region, and later his sons' agents cheated the Indians with the Walking Purchase nearby. The politics of Bucks County are easily imagined by looking at prosperous Doylestown and comparing it with nearby rundown Easton. This is really just the center of Bucks County, half of which extends to the North, and all of which must have an interesting political history.

|

| Ringing Rocks County Park |

Abruptly, turning a corner amidst the summer cottages, is a neat little park, the Ringing Rocks County Park. At times it is deserted, at other times you can hardly find a place to park your car. Fields of boulders, three to ten feet in diameter, extend down the hill to the river. It's easy to go down, not so easy to get back up to your car. People pile out of their cars, carrying brand-new hammers, and you can see dozens of (probably disappointed) pockmarks on the rocks near the parking area. If you thought it was going to be easy, you are quickly disappointed.

|

| Japanese Beetle |

But the legions of cub scouts, happily swinging their hammers, swarm down on the rock piles, hitting every rock as they go. If there are enough of them, you hear plenty of clunks, but also an occasional ringing chime is heard, and the other cubs soon swarm around. At a rather daunting distance from the edge of the rock field, one cub scout after another discovers a rock that chimes like a cowbell. He attracts his friends, who have a whack at it. The chimes never quite outnumber the clunks, but the music rises as the scouts swarm over the property on agile little feet that soon defeat their elders' lumbering climb. A sudden thundershower made the rocks too slippery even for kids, and the place quickly emptied out. When we got back to the top of the hill, soaking wet, there were only a few cars still there.

Hidden River

.jpg)

|

| Schuylkill River |

In Dutch, Schuylkill means "hidden river", thus making it redundant to speak of the Schuylkill River. As soon as you become aware of this little factoid, you start to come across Philadelphians who do indeed speak of the Schuylkill in a way that acknowledges the origin of the term. To give it emphasis, it is common to speak of the "Skookle". The point comes up because cruises have started to leave from the dock at 24th and Walnut Streets, where it becomes quite noticeable that the Schuylkill really is rather hidden as it winds seven miles south to the airport, in contrast to the wide-open vista we all are accustomed to seeing from the Art Museum northwards.

The bluff at Gray's Ferry, where the University of Pennsylvania's new buildings now dominate the scene, was originally the beginning of dry land, or the end of the rather large swamp, through which the river winds its way essentially shaded by trees along the riverbank. Never mind the junkyards and auto parks you happen to know lurk behind the trees on the west side or the oil tanks which loom above the trees on the south bank. As evening closed in on the riverboat, the gaily lit towers of center city were looming in the stern, but some fishermen along the bank proudly held up a respectable string of six or seven rather large catfish. If you are there in the evening, the river has the same feeling of wilderness that the Dutch traders would have experienced three hundred years earlier. No swans, however. There were many reports in the Seventeenth Century of large flocks of swans sailing around the entrance of the Schuylkill into the Delaware River. A noted local ornithologist on the recent cruise remarked that forty or fifty species of birds are found there. Even a flock of owls still live within the city limits. You don't see owls, even if you are an ornithologist; their presence is made known by taking recordings of the sounds of the night.

|

| Fort Mifflin |

The geography of swampy South Philadelphia was created by the abrupt bend in the Delaware River at what is now thought of like the airport region. As the river flows at the bend, sediment is deposited in mud flats that once created Fort Mifflin of Revolutionary War fame, and later Hog Island of the Naval Yard, home of the hoagie. Swans are beautiful creatures, but they seem to like a lot of mud. The lower Schuylkill is tidal, and the industrial waste of the region is cleaned out of the land by cutting drainage ditches laterally from the river, flooding the lowlands as the tide rises, and draining it again as the tide falls. This cleansing seems to be working, as judged by the return of spawning fish. And maybe mosquitos, as well, but it would seem rude to inquire.

The Bartram family seems to have known how to make use of river bends and riverbanks, placing the stone barn and farmhouse higher up the bank, but below the bluff of Gray's Ferry forces a bend in the Schuylkill, below which of course flatlands were created. It's a peaceful place, now made available for tours and excursions by placing a landing dock on metal pilings so that it can ride up and down with the tides. The great advantage is that riverboat landings are no longer restricted to two a day, at high tide, with limited time to visit before the tide falls again. Bartram recognized how popular strange plants from the New World would be in England, and his exotic plants were quite a commercial success. Nowadays the big sellers are Franklinia Trees, available the first week in May. The last Franklin (named of course for his friend Benjamin) ever found growing in the wild, was the one John Bartram found and nurtured. Every Franklinia is thus a descendant of this one. They look rather like dogwood but bloom in the early fall. If it suits the fancy, a dogwood next to a Korean dogwood which blooms in June, next to a Franklinia, can make a continuous display of bloom from May to October. And best of all, no one will appreciate it, unless they are in the know.

Heron Rookery on the Delaware

|

| Great Blue Heron |

When the white man came to what is now Philadelphia, he found a swampy river region teeming with wildlife. That's very favorable for new settlers, of course, because hunting and fishing keep the settlers alive while they chop down trees, dig up stumps, and ultimately plow the land for crops. As everyone can plainly see, however, the development of cities eventually covers over the land with paving materials; it becomes difficult to imagine the place with wildlife. But the rivers and topography are still there. If you trouble to look around, there remain patches of the original wilderness, with quite a bit of wildlife ignoring the human invasion.

|

| Heron Nests |

Such a spot is just north of the Betsy Ross Bridge, where some ancient convulsion split the land on both sides of the Delaware River; the mouth of the Pennypack Creek on the Pennsylvania side faces the mouth of the Rancocas Cree on Jersey side. In New Jersey, that sort of stream is pronounced "crick" by old-timers, who are fast becoming submerged in a sea of newcomers who don't know how to pronounce things. The Rancocas was the natural transportation route for early settlers, but it now seems a little astounding that the far inland town of Mt. Holly was once a major ship-building center. The wide creek soon splits into a North Branch and a South Branch, both draining very large areas of flat southern New Jersey and making possible an extensive network of Quaker towns in the wilderness, most of whose residents could sail from their backyards and eventually get to Europe if they wanted to. In time, the banks of the Rancocas became extensive farmland, with large flocks of farm animals grazing and providing fertilizer for the fields. Today, the bacterial count of Delaware is largely governed by the runoff from fertilized farms into the Rancocas, rising even higher as warm weather approaches, and attracting large schools of fish. My barber tends to take a few weeks off every spring, bringing back tales of big fish around the place where the Pennypack and Rancocas Creeks join Delaware, but above the refineries at the mouth of the Schuylkill The spinning blades of the Salem Power Plant further downstream further thin them out appreciably.

Well, birds like to eat fish, too. For reasons having to do with insects, fish like to feed at dawn and dusk, so the bottom line is you have to get up early to be a bird-watcher. Marina operators have chosen the mouth of the Rancocas as a favorite place to moor boats, so lots and lots of recreational boaters park their cars at these marinas and go boating, pretty blissfully unaware of the Herons. Some of these boaters go fishing, but most of them just seem to sail around in circles.

|

| As Seen From Amico Island |

Blue herons are big, with seven-foot wingspreads as adults. Because they want to get their nests away from raccoons and other rodents, and more recently from teen-aged boys with 22-caliber guns, herons have learned to nest on the top of tall trees, but close to water full of fish. And so it comes about that there is a group of small islands in the estuary of the Rancocas, where the mixture of three streams causes the creek mud to be deposited in mud flats and mud islands. There is one little island, perhaps two or three acres in size, sheltered between the river bank and some larger mud islands, where several dozen families of Blue Herons have built their nests. One of the larger islands is called Amico, connected to the land by a causeway. If you look closely, you notice one group of adult herons constantly ferries nest building materials from one direction, while another group ferry food for the youngsters from some different source in another direction. At times, diving ducks (not all species of ducks dive for fish) go after the fish in the channel between islands, with the effect of driving the fish into shallow water. The long-legged herons stand in the shallow water and get 'em; visitors all ask the same futile question -- what's in this for the ducks? The heron island is far enough away from places to observe it, that in mid-March its bare trees look to be covered with black blobs. Some of those blobs turn out to be heroes, and some are heron nests, but you need binoculars to tell. When the silhouetted birds move around, you can see the nests are really only big enough to hold the eggs; most of the big blobs are the birds, themselves. There are four or five benches scattered on neighboring dry land in the best places to watch the birds, but you can expect to get ankle-deep in the water a few times, and need to scramble up some sharp hills covered with brambles, in order to get to the benches. In fact, you can wander around the woods for an hour or more if you don't know where to look for the heron rookery. Look for the benches, or better still, go to the posted map near the park entrance south of the end of Norman Avenue. There are a couple of kiosks at that point, otherwise known as portable privies. Strangers who meet on the benches share the information supplied by the naturalists that herons have a social hierarchy, with the most important herons taking the highest perches in the trees. That led to visitors naming the topmost herons "Obama birds", and the die-hard Republicans on the benches responding that the term must refer to dropping droppings on everybody else. That's irreverent Americans for you.

There is quite a good bakery and coffee shop just north on St. Mihiel Street (River Road), and the new diesel River Line railroad tootles past pretty frequently. That's the modern version of the old Amboy and Camden RR, the oldest railroad in the country. It now serves a large group of Philadelphia to New York commuters, zipping past an interesting sight they probably never realized is there because they are too busy playing Hearts (Contract Bridge requires four players, Hearts are more flexible). However, there's one big secret.

The birds are really only visible in the Spring until the trees leaf out and conceal them. Since spring floods make the mud islands impassible until about the time daylight savings time appears, there remains only about a two-week window of time to see the rookery, each year. But it is really, really worth the trouble, which includes getting up when it is still dark and lugging heavy cameras and optics. Dr. Samuel Johnson once remarked that while many things are worth seeing, very few are worth going to see. This is worth going to see.

And by the way, the promontory on the other side of the Rancocas is called Hawk Island. After a little research, that's very likely worth going to see, too.

Chester County, Pennsylvania

|

| Map of Chester County |

Chester County was one of the four original counties of Pennsylvania, as first laid out by its first white owner, William Penn. Although several parts of Chester County have been cut away, what's left is still quite large. Lancaster County was separated in 1729, and in 1785 Dauphin County was separated from that. In 1789, Delaware County was separated. If you stand in the horse country of Chester County, you still might find it hard to believe anything much has happened in three hundred years. But as a matter of fact, the present population residing within Penn's original boundaries of Chester County would make it the most populous county in the state and growing steadily. Since Philadelphia and Pittsburgh are meanwhile shrinking in population, projected future relationships would strike most residents of Chester County as quite remarkable. Horses, that's what Chester County wants to be all about. Even the mushroom growers of Kennett Square sort of count as part of the horse industry, because mushrooms are grown on horse manure, in the dark. Electronics and steel mills are not exactly traditional, but they reside here, too. As a small footnote, the Lukens Steel Company was recently purchased by an investor named Ross, who lumped it with several other steel mills and then sold the bundle to an owner in India. The consequence is that Chester has a footprint of the largest steel company in the world, or the largest steel company in India, whichever way you wish to style it. Nevertheless, the neighborhood still looks like horse country.

Furthermore, southern Chester County is socially part of the state of Delaware, while western Chester County is thoroughly Pennsylvania Dutch. Up north, the Philadelphia Main Line is building mansions as fast as mortgage originators will allow, and many of them end up paying Chester County taxes. All along Route 202, the central artery of the Great Valley, stretches a burgeoning electronics industry, within which is found Vanguard, the largest investment company in America, or possibly the second largest, depending on temporary quirks of mark-to-market pricing. Chester County presently has the highest average personal income of any county in America. It is far from true that everybody has a horse farm or a trust fund.

|

| David Rittenhouse's compass |

In a spiritual sense, Chester County horse culture contiguously spreads far beyond even historic outlines of Chester County. The boundaries of southeastern Pennsylvania were laid out with David Rittenhouse's compass, so the rolling hills suitable for horse farming extend into the states of Delaware and Maryland, and of course out into Lancaster and Dauphin counties, without much visible sign of individual state or county. In Europe, by contrast, almost all boundaries are set by rivers and mountain ranges, so the physical appearance of the countryside is apt to change sharply when crossing political borders. In fact, it is possible to say it in reverse: the State of Delaware is mostly Chester County extended, at least in its upper third. Below that lies urban and suburban Wilmington, and below that ("south of the canal") spreads loamy flat farm country, formerly slave country. Maryland divides similarly; an upper third of Maryland's rolling hillsides (sometimes known colloquially as Chester County extended), followed on the south by tidewater Maryland, in turn, followed by the suburbs of Washington, DC. The remnants of Baltimore are mixed in there somewhere, too. When you drive through miles of silent prosperous farms, regardless of highway signs, it is natural to think of yourself in the heart of America.

The one thing Chester County never much warmed to was Universities. It may shock residents of New York City to hear that Chester County never thought much of having its own art museums, classical music, theater performances or opera. However, Chester County doesn't share typical urban dislikes, either. Local speech patterns suggest Appalachian hillbillies and the Pennsylvania Dutch L'il Abners are just like us, just not so rich. Chester County sometimes thinks of itself as nobility, but it isn't Ivy League nobility, it's a country squire. We all like horses, dogs, and guns, we can't imagine why everyone else doesn't like them, too. Chester County has more history than almost anybody; it just doesn't talk much about it.

|

| Josiah Harlan |

So let's mention just the highlights: George Washington fought the battle of the Brandywine, the biggest battle of the American Revolution, in Chester County, the Paoli Massacre was long regarded as the second nastiest event of that campaign. A local farmer's son, Josiah Harlan (1799-1871), did what the Tsars and Dictators of Russia and the Kings and Queens of England couldn't do; he conquered Afghanistan. Moreover, he did it single-handedly, making himself King. Even the 350 American Rangers who conquered Afghanistan in 2002 can't match that exploit by this local Quaker boy. The first intern doctor of the first hospital in America (Jacob Ehrenzeller) spent his long life practicing in Chester County. The only President of the United States to come from Pennsylvania (James Buchanan) hailed from Lancaster, not terribly long after it split off from Chester County. In a wry sort of way, it can be said that Buchanan created the Republican Party by almost getting us to annex Cuba. Harrisburg, the present capital of the state, was once part of Chester County. Major portions of both British General Howe's and General Washington's armies left the Brandywine battlefield and swept up the Great Valley of Chester County to Philadelphia and Valley Forge, respectively. Conestoga Creek was once part of Chester County, and Conestoga wagons took many generations of settlers westward to build the new nation; wagons do go pretty naturally with horses. But drive through miles of Chester County today, usually alone through the silent stone barns and rolling grasslands: nothing much seems to have happened except real estate is more expensive.

But then, just drive up Route 202 from Wilmington to King of Prussia, at rush hour. This may be the Great Valley where Washington retreated to Valley Forge, but now it's where employees of the electronics industry ferry children to school, in order to get into the Ivy League, and maybe to shop at fancy stores in King of Prussia. With time out for a recession, it could be wall-to-wall McMansions around here in a generation. It seems almost certain the future will bear little resemblance to the past. It's sort of a pity, it is a great economic opportunity, and it seems inevitable.

Army War College in Carlisle

|

| U.S. Army War College |

Our program chairman, Carter Broach, once attended the Army War College, so he was in a position to invite Colonel Tom O'Steen to the Right Angle Club to tell us what the College was all about. Although there may have been times in the past when the Army welcomed secrecy surrounding its College, in recent years it has become concerned that the military may be isolating itself too much from the people it serves and defends. So Col. O'Steen was told he was welcome to talk to us. In fact, giving one speech to the public is a requirement for graduation. The history goes back to 1757, includes Ben Franklin, and also includes some interesting anecdotes which might not have been expected of a War College.

Like all land in Pennsylvania, this plot within what is now the town of Carlisle, PA, once belonged to William Penn. Nobody else owned it until 1757 when Ben Franklin was sent to negotiate its transfer from the Indians. William Penn had been careful to buy land from the Indians, even though he also formally owned it as part of a deed from Charles II of England. Other land proprietors had not been so scrupulous, often complaining of the Indian massacres which resulted, although seldom adopting Penn's rather inexpensive method of avoidance.

|

| Robert E. Lee |

During the Revolutionary War, Carlisle was a comfortable distance from the British Navy, and served as a backwoods artillery arsenal along the Appalachian Mountains, much as the Ho Chi Minh Trail served our enemy in the Vietnam conflict, along with an Asian mountain range. From 1790 to 1860, Carlisle served as a cavalry post, and then General Robert E. Lee invaded Pennsylvania up one side of a mountain ridge, with General Meade bringing up the Union forces from Washington DC on the other side of the ridge. The two valleys come together at Carlisle, so that spot had long been recognized as commanding both. Lee only got as far as Gettysburg before Meade caught up with him, but General Ewell's Corps took Carlisle as an advance guard. Confederate cavalry General JEB Stuart took Carlisle without sustaining a fight. Meanwhile, General Lee was fretting that Stuart was supposed to be his eyes and ears, keeping him informed of Union opposition, and it is possible that Stuart's Carlisle diversion thus had some influence on the outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg.

|

| Earl of Carlisle |

By 1879 there remained little purpose in a Carlisle military post, so it was turned into an Indian Industrial School, a couple of miles East of Dickinson College. After the Civil War, the nation lost its taste for exterminating Indians and turned to the idea of removing Indian boys from their families in order to assimilate them to white customs. Unfortunately, this did not work very well, and in fact, nothing worked very well. There are over 340 Indian languages from Eskimo to Aztec, but there is no record of any tribe allowing itself to be assimilated. The Spanish tried slavery, the French tried intermarriage, and the Americans tried persuasion and reasonableness. Eventually, we gave up and isolated them on reservations, but not before a wide-spread attempt was made to isolate Indian boys in boarding schools, hoping to remove them from tribal influences. That didn't work, either, but it was being attempted at Carlisle in the late 19th century. Interestingly, Carlisle is named after the family of the Earl of Carlisle, who was sent by Lord North after the disastrous British defeat at Saratoga, in order to see if the colonists might still be interested in Taxation with Representation. We weren't, so the Revolutionary War dragged on for another six years. Somehow, when war fever captures countries, small victories seems to close minds to what they had been originally fighting over. If the War College has time for another lesson, I suggest they add that one to their curriculum.

Before going back to the origins of the Army War College, we should salute the momentous football game of 1912, between the West Point cadets who included Dwight Eisenhower, and the Carlisle Indian School team which included Jim Thorpe. Thorpe was a member of an Oklahoma Indian tribe, but in many ways has been regarded as the best all-around American athlete in history. Eisenhower was pretty good, too, but Carlisle won the game.

To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years; To provide and maintain a Navy;

|

| Constitution, Article 1, section 8 |

Several members of the Right Angle audience expressed the view that the Armed Services have more to fear from know-it-all university professors who feel they monopolize the field of strategic thinking than from Congress, which tends to have a goodly number of combat veterans in its ranks. It's all very well to repeat the mantra that the armed forces must respect civilian control, and then it's also just as well to remember that most coups are military coups in other countries. But whatever the future brings, these young Lt. Colonels will be the ones we must count on when the going gets really tough.

The Eventual Economy of Excellence

|

| Samuel Y. Harris |

The Right Angle Club was recently visited by two sprightly young ladies who run a historical building reconstruction firm. Sam Harris once ran the firm and built it into the pre-eminent example of its type, with the quirk that he surrounded himself with women. So, after Sam's unfortunate early death, two of the ladies decided to carry on the business. It was a little hard to picture these two young ladies in blue jeans, climbing all over the rafters of old buildings, but they showed plenty of slides of their work, which in the background showed the ladies doing just that.