1 Volumes

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

Military Philadelphia

.

City Troop

|

| First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry (FTPCC) |

On 23rd Street, just South of Market, stands a gloomy Victorian castle with big doors opening to the street. It's the armory, housing the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry (FTPCC). The organization is a real fighting unit of the Pennsylvania National Guard, participating with distinction in every war America has fought. Originally a horse cavalry, the unit now drives tanks, except for recreation and on ceremonial occasions. It lays claim to being the oldest military unit in America, although there have been several minor name changes since the days when the City Troop accompanied General Washington to take command of the troops in Boston. Their dress uniforms are pretty splashy, especially on horseback, and they have to pay for them, themselves.

Furthermore, they are required to donate all of their military pay toward the upkeep of the unit and its activities. Although the first step in membership is to become a real member of the National Guard, election to the Troop itself is truly an election, carefully screened after prospective members have been observed and evaluated at invited Troop functions. These soldiers are wealthy, athletic, mostly pretty handsome, and almost invariably well-connected socially. You could almost make up the rest from these essential ingredients. This is the innermost core of Philadelphia society, and it is intensely and sincerely patriotic.

Others have noticed that National Guard duty itself takes up many weekends and much of summer vacation. Add to that the many Troop dinners, the horsemanship activities, the debutante balls, the Chesapeake sailing cruises, the national and local ceremonies, the weddings and funerals for members -- and actually fighting wars overseas. The members of the Troop spend so much of their time on Troop-related activities, that they become both intensely loyal to each other, and necessarily somewhat withdrawn from other people. They gravitate to polo, the Racquet Club, the Savoy, the Orpheus, and the financial world.

There may be an important insight into the generation turmoils to be derived from this. There was once a time when most professions likewise absorbed the lives of their members, with professional clubs and entertainments confining the social life of the member by leaving little time for anything else. But in recent years most occupational and professional societies are experiencing a loss of membership and enthusiasm, leading to the bewildering question of "Where are the younger members, any more?" The pre-fabricated answer is that younger people now want to devote their quality time to their families, but if you believe that, you will believe anything. Let's face it; when one activity absorbs all of your time, it confines you. There have to be some important benefits to being so confined, and even so, it chafes a little. Those of us who are not baby boomers can see that being a slave to intra-generational consensus is only to be a slave in a different way. The remarkable thing is that the baby boomers fail to see it, themselves.

Mrs. Meade's House

|

|

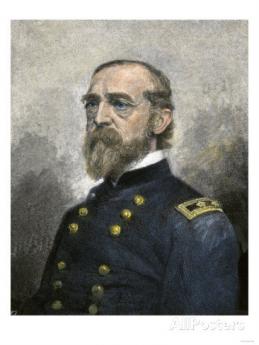

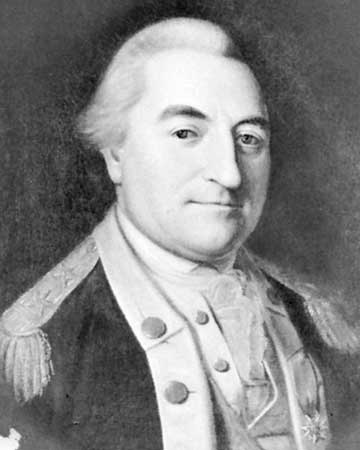

Union General George Gordon Meade |

General George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg, lived in quite an elegant house during the six years (1866-72) he was a Commissioner of Fairmount Park. The house (at 19th and Delancey) has "MEADE" carved over the stately entrance facing 19th Street, and while the neighborhood has run down somewhat, it was obviously once an imposing mansion. The house belonged to Mrs. Meade. From that, you might suppose that the General had married a rich woman, but that would be wrong.

When General Lee was advancing on Gettysburg, it was widely supposed that his goal was to conquer Philadelphia, the Arsenal of the North. The town was in a panic, built some forts on the Schuylkill to defend itself, and later lionized the hometown hero who had saved them. Mrs. Meade was living at the time in a modest little place, and the town fathers took up a collection to buy General Meade a proper house.

A delegation of officials traveled down to Virginia to present him with their gift of gratitude, but Meade would have none of it. He was only doing his duty, and could not consider for a moment accepting major gifts for his soldiering. No, he was very sorry, he had to decline.

So the delegation came home, all a fluster. Someone then had the idea of offering the house to Mrs. Meade. And when they visited her, she promptly said "Sure."

Tales of the Troop

|

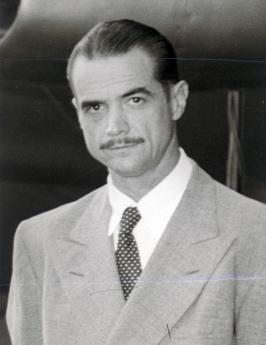

| Dennis Boylan |

Dennis Boylan, the former commander of the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, has been poking around in the archives up at the Armory, and was invited to tell the Right Angle Club about it. In all its history, there have only been 2500 members of the troop, but they have been a colorful lot, leaving lots of history in bits and pieces. The troop boasts that it has seen active duty in every armed conflict of America, and means to continue to fight as a unit of the Pennsylvania National Guard. However, we have lately had so many actions, the troop has had to split off units to be able to go to the Sinai Peninsula, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan and whatever is going to come next. An eighteen month tour of active duty takes a lot out of a citizen soldier's life, but no one is complaining, and there is no fall-off in volunteers.

Although most troopers are polite and taciturn, it is probably hard to remain unaffected by association with people like A.J. Drexel Biddle, a pioneer of the bayonet and hand-to-hand fighting, much sought after for training other units of the military. Or George C.Thomas, who was a golf course architect, but also a seaplane expert, responsible for the seaplane ramps next to the Corinthian Yacht Club along Delaware. Or Rodman Wannamaker, responsible for aeronautic development, also down in the marshes where the Schuylkill joins Delaware. Robert Glendinning, who was notable for other adventures, was also an early pioneer in airplanes. As a matter of fact, Henry Watt had himself flown from Society Hill to Wall Street in a seaplane, when he was President of the New York Stock Exchange.

It's hard to believe, but a former trooper named Eadweard Muybridge distinguished himself in the art world, as a result of a bet with Leland Stopford, that a horse at a gallop reaches a point where all four feet are simultaneously off the ground. The consequence was a famous set of rapid-sequence photographs which are quite famous at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. There are elephants, horses, people in various states of undress which remain as interesting artworks as well as scientific evidence that horses feet do indeed leave the ground. But in case anyone believes that Muybridge was some sort of sissy from the art world, there is the story that he caught his wife in an affair and shot the other man dead. As one might expect, the jury found him not guilty, on the grounds of justifiable homicide. With a name like Eadwaerd, it's probably necessary to demonstrate your manliness.

Robert Glendinning, class of 1888 at Penn, became Governor of the New York Stock Exchange, founded Chestnut Hill Hospital and the Philadelphia School for the Deaf. And Thomas Leiper makes a pretty good claim for starting the first railroad in America. It was only 2 miles long, in Swarthmore, and built because he was not permitted to extend his canal for the purpose of transporting stone from upstate quarries. The railroad developed into the Pennsylvania Railroad; Leiper's house, "Strathaven" is still an important Delaware County landmark.

|

| Tank in Philadelphia |

And then, there's the story of the salute to the QE2. When the liner made a tour up the Delaware, a search was made for cannons to provide a proper salute, and the call came to the Troop. Well, they had a tank, and they could fit a simulator on the tank's gun. So, the tank rumbled down Broad street to do its duty. South Philadelphia responded in character, too. Instead of stopping to admire the novelty of a moving tank, the drivers just honked their horns and drove around it.

The Quaker Who Would Be King

|

| Jerry Leon |

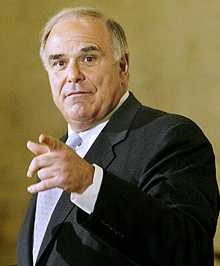

Once every year or two, a speaker at the Right Angle Club fails to show up. That happened recently, and as usually happens, one of the members stood right up to the microphone and gave an impromptu speech. The volunteer was Jerry Leon, who surprised us all by announcing he spent thirteen years in the Marines as a fighter pilot on aircraft carriers. You would never guess that from his behavior as a successful businessman, and to some extent that was his whole point.

In the first place, he volunteered as a Marine during the Korean War, and worked his way through boot camp and all that, until one day an officer brought them all to attention, asking for volunteers to fly airplanes. After flight training school, he might have flown air freight or eight-engine bombers, but he volunteered to fly fighter planes off the deck of an aircraft carrier. In those days, the carrier plane was fired by a steam driven catapult off the flight deck like a projectile. You go from zero speed to two hundred miles an hour in two or three seconds; the experience is arresting. After he recovers his wits, the pilot is expected to take sole control of the plane, fly around the carrier a few times, and then land the plane on the postage stamp flight deck. Fighter planes come in at a lower altitude than commercial aircraft, and steeper, and faster. The tailhook catches one of the three wires across the deck, and then the plane jolts to a stop. Or not, in which case the pilot must retake immediate control, take off at full speed, circle the carrier, and try it again. That's hard enough on a calm sea, but the Navy never stops for rough weather, so at night in rough seas, you have to do it in the dark with the ship rising, falling, pitching and yawing, right or left in three dimensions. That's somewhat harder. There are usually four planes in the air at any one time, all doing the same thing every ninety seconds, and if the plane runs off the end of the landing strip the pilot must remember to eject before he goes down with the plane. This whole process must be repeated six times in one day with only one aborted landing, in order to qualify for carrier duty. Saying nothing of the sudden bumps and jolts, the process of qualifying is pretty hard on the sphincters, it's pure terror no matter who you are. Like stage fright for an actor, crash landing does seem easier with practice but having done it seven hundred times, Jerry still wasn't able to do it calmly.

|

| P40 War Hawk |

Unusually good eye/hand coordination is something you are born with, and baseball seems to require the same ability. Ted Williams, the famous .400 hitter for the Boston Red Sox, was an outstanding fighter pilot, and many less famous professional baseball players have also gravitated to the role. To be called a fighter ace a pilot must have shot down five enemy planes, and one pilot became a fighter ace at the Battle of Midway on his first mission. Because of his lack of experience, this pilot was only detailed to hunt for the battleship Yamamoto, but he found it, radioed its location, and on the return flight ran into 30 enemy planes. Tearing into them alone, he shot down five, becoming an ace before he returned to the carrier deck from his first mission. Now there's the killer instinct with eye/hand coordination, the combination which seems to make you an ace. He wasn't alone in these qualities, although 30% of the pilots do seem to account for 90% of the victories. In those days "between W-2 and Korea" the American pilots were flying propeller planes, while the Chinese pilots were flying jets, and even the Germans were flying some jet-powered Messerschmidts. That's five hundred miles an hour versus seven hundred, and the enemy planes would often swoop past in a whoosh. So, the Americans developed a technique. When the jet came up on your tail, you pulled back as hard as you could with all flaps down. The enemy jet pilot had to pull up his nose, flew over the top of the propeller-driven American, and then was blasted out of the air by the prop plane now waiting for him from behind. They say it worked every time, but of course, it only worked for the pilots who came back to talk about it. A former pilot with Chenault once told the story of letting go with fifty-caliber machine guns into the tail of a Zero, causing the Zero and its pilot to vanish into a puff of smoke and debris. Of course, the prop plane then just flew through the cloud.

|

| Pilot's Hat |

The fly-boys were of course chased by hordes of women, particularly in the bars around the training school in Pensacola. They drank hard, at reckless heedless parties; it was reported that Australian pilots even had two or three drinks before taking off, but our Navy strictly policed going that far. Nobody saved any money, nobody cared one whit about being promoted or demoted. Getting to be an Admiral was something that attracted what were disdainfully referred to as "politicians". And nobody bragged about his exploits, even to friends and family. What mattered was that word of mouth had carried your exploits to your buddies. The senior George Bush flew a bomber not a fighter plane, but he played baseball like an angel, and you never heard him boast of his adventures; that's a fair approximation of the personality type, although George Bush was unusually tall for a pilot, and clearly better bred. If you can't guess what he thought of Bill Clinton and Ross Perot, it isn't necessary to relate it here.

Somehow, feminist women intruded themselves into this fraternity, and some who seemed well-qualified got hustled along through token promotions. But few women have the real killer instinct, and just getting equal opportunity won't get you through those six gut-wrenching flights in a carrier qualification. Thirteen women pilots were killed in qualification flights before the Secretary of the Navy intervened and put a stop to it. To new entrants from a previously shunned group, achieving the same status as men is a form of promotion, and lusting for promotion is despised by natural-born fighter pilots. It's sort of a Catch-22 situation. What killers want, is to excel at things that are viciously dangerous, getting the esteem of others who tried to do as much and maybe failed; like tournament golf, in this game, you are really playing against yourself. And so this Greek tragedy finally came to a confused pause with the famous Tailgate party incident. To preserve appearances and rescue The Service from the press corps, the Navy brass was shocked, shocked, to discover what was going on. Women weren't being respected if you can believe such a thing of fly-boys.

"Hey, fellas, c'mon. Do you want to win this war or don't you? Professional killers have been behaving like this for centuries. And because you come along, we've got to change and do things your way?"

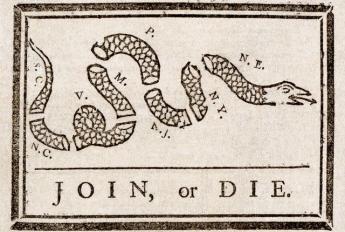

Battle of the Clouds: September, Remember

|

| Dilworthtown |

Weather satellites, television and so on have taught us much about hurricanes that was unknown in 1777. Benjamin Franklin, it should be noted, was the first to observe that Atlantic Coast "Nor'easters" actually begin in the South and work North, even though the wind seems to be blowing in the opposite way; what's moving toward the northeast is a low-pressure zone. We now know that hurricanes begin in Africa, travel West and then veer North when they reach Florida. A great deal is still to be learned about hurricanes, but the most important thing about their timing is contained in a maritime jingle:

June, too soon.

July, stand by.

And then: September, remember.

October, all over.

Along the Atlantic east coast, the end of August to the middle of September, is hurricane season. That's when houses blow down in Florida, and heavy rains hit Pennsylvania. Admiral Howe might have had some clue to this, since Franklin made his observation around 1750, and storms are important to Admirals. But very likely his brother the General just thought it was one of those things when the British landing at Elkton, Maryland in late August 1777 was greeted with an unusually severe downpour of rain. Howe had planned to surprise Philadelphia from the rear by hitting the ground running on horseback. However, he underestimated the debilitating effect on the horses of three weeks at sea on sailboats; to unload and forage horses during a hurricane was almost too much for the plan. For that purpose, he had given orders for the troops to disembark without waiting to pitch camp, or unpacking their gear. But the drenching rain gave Washington several extra days to organize a defense, although he has been given too little credit for the strenuous accomplishment of moving an army from Bucks County to the banks of the Brandywine in that weather. Howe, whose trademark was surprise, deception, outflanking, had anticipated a sudden cavalry thrust into the backyards of unprepared Philadelphia. What he got was 2000 casualties in the biggest battle of the Revolutionary War, against Washington's well-prepared defense along the steep-sided Brandywine Creek.

Howe won this battle, in the sense that Washington was forced to withdraw, because Howe employed another British military trademark, of driving his own troops beyond humane limits in a huge outflanking movement. The countryside around Kennett Square is hilly and broken almost to West Chester, and the American Army felt reasonably prepared along a front of ten or twelve miles. But Howe drove the main force of his army seventeen miles to the north, to Dillworthtown, before turning the unprepared American right flank. And, in the now hot August weather in full uniform and battle pack, the drive continued for twenty-four consecutive hours until Washington saw he had to withdraw. This was what the British meant when they boasted of seasoned regular troops; you win by enduring more than your opponent can endure.

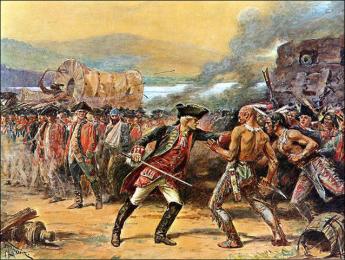

One has to have equal admiration for Washington. Although he was dislodged from his position, losing the opportunity to catch the British in a hostile region without a reliable source of supplies once the fleet weighed anchor, he preserved his army of marksmen and deer hunters intact during the retreat. The two armies started at roughly the same size, and Washington had only about 1300 casualties; his men had more certain supply sources, and they were fighting for their homes. The British, somewhat outnumbered, had the prospect of fighting their way without resupply through an enemy's home territory, capturing the enemy's capital, but still facing the possibility that the British fleet might not get past the Delaware River defenses. If that happened, they could celebrate their victory by starving to death. Just about the only weakness of the Continental Army was its discomfort with bayonet warfare. They could hit a squirrel at a hundred yards, but those long bayonets on the end of very long muskets were designed to protect foot soldiers from cavalry charges. It takes training to put the butt of the musket against a stone on the ground, hold your ground against an oncoming gallop of horsemen, and trust that at the last moment the horses will rear back and throw the riders. But it also takes naked bravado to wave a sword and ride full tilt into a forest of pointing bayonets, trusting that at the last moment the defenders will break and run.

But Washington knew what he was doing. He pulled the troops back to Chester, then over the Schuylkill to the Germantown encampment at Fox and Queen Lane, then up the Schuylkill to Norristown, the first ford in the river that Howe must use when the boats and bridges were destroyed. The river would hold the British while the Americans came at them from the rear; this was essentially the same river strategy he used at the battle of Trenton. Washington picked his battlefield in Chester County and got ready to fight the second installment of the Battle of Brandywine. The campus of Immaculata University now occupies the site.

And then it rained, again. Hard. The gunpowder on both sides was soaked, useless. In what has come to be known as the "Battle of the Clouds", the fighting was called off by mutual agreement. The second hurricane of the year had arrived, and Washington more or less helplessly had to watch Howe take over Philadelphia unopposed. He lost the capital, provoking dismay among the colonists, but his masterful strategy taught the British to respect him. When the British were later considering whether to hold or abandon Philadelphia, this growing respect for their adversary helped tilt their thinking toward prudence.

But that was not before Howe once more showed he too was not the lazy slacker that others had called him. General "Mad Anthony" Wayne was dispatched with fifteen hundred troops to hassle the rear of Howe's army. Wayne was confident he could hide his troops in the Radnor area where he had been brought up, but the region in fact had many Torys to report his movements. Howe ordered Major General Lord Charles Grey to take the flints from his troops' muskets, attack the American camp near Paoli's tavern in the night, and use only bayonets. Waynes' troops were scattered and slaughtered, in what came to be known as the Paoli massacre.

Battleship New Jersey: Home is the Sailor

|

Home is the sailor, wrote A. E. Housman, Home from the sea. In this case, the sailor is the Battleship New Jersey. The U.S.S. New Jersey rides at permanent anchor in the Delaware River, tied to the Camden side. You can visit the ship almost any afternoon, and with reservations can even throw a nice cocktail party on the fantail. It's an entertaining thing to do under almost any circumstances, but the trip is more enjoyable if you spend a little time learning about the ship's history. The volunteer guides, many of them still grizzled veterans of the ship's voyages, will be happy to fill in the details.

In the first place, the ship's final bloody battle was whether to moor the ship in the Philadelphia harbor, or New York harbor, when the U.S. Navy had got through using it. You can accomplish that and remain in the state of New Jersey either way, but there's a big social difference between North Jersey and South Jersey, so the negotiations did get a little ugly. Because of the way politics go in Jersey, it wouldn't be surprising if a few bridges and dams had to be built north of Trenton to reconcile the grievance, or possibly a couple of dozen patronage jobs with big salaries but no work requirement. The struggle surely isn't over. Battleships are expensive to maintain, even at parade rest; if you don't paint them, they rust. Current revenues from tourists and souvenirs do not cover the costs, so the matter keeps coming up in corridors of the capitol in Trenton.

Home is the sailor, home from sea:

Home is the hunter from the hill:

'Tis evening on the moorland free,

|

|

A. E. Housman

R.L.S. |

Battleship design gradually specialized into a transport vehicle for big cannon, ones that can shoot accurately for twenty miles while the platform bounces around on the ocean surface. Situated in turrets in the center of the vessel, they can shoot to both sides. That's also true of armored tanks in the cavalry, of course, with the history in the tank's case of the big guns migrating from the artillery to the cavalry, causing no end of a jurisdictional squabble between officers trained to be aggressive for their teams. Originally, the sort of battleship which John Paul Jones sailed was expected to attack and capture other vessels, shoot rifles down from the rigging, send boarders into the enemy ships with cutlasses in their teeth, and perform numerous other tasks. In time, the battleship got bigger and bigger so in order to blow up other battleships had to sacrifice everything else to sailing speed and size of cannon. Protection of the vessel was important, of course, but in the long run, if something had to be sacrificed for speed and gunpowder, it was self-protection. There's a strange principle at work, here. The longer the ship, the faster it can go. Almost all ocean speed records have been held by the gigantic ocean liners for that reason. If you apply the same idea to a battleship, the heavy armored protection gets necessarily bigger, and heavier as the ship gets longer, and ultimately slows the ship down. As a matter of fact, bigger and bigger engines also make the ship faster, until their weight begins to slow them down. Bigger engines require more fuel and carrying too much of that slows you down, too. Out of all this comes a need for a world empire, to provide fueling stations. Since the Germans didn't have an empire, they had to sacrifice armor for more fuel space and more speed, to compensate for which they had to build bigger guns but fewer of them. Although the British had more ships sunk, they won the battle of Jutland because more German ships were incapacitated. When you are a sailor on one of these ships, it's easy to see how you get interested in design issues which may affect your own future. An underlying principle was that you had to be faster than anything more powerful, and more powerful than anything faster.

The point here is that the New Jersey, as a member of the Iowa class of battleship, was arguably the absolutely best battleship in world history. At 33 knots, it wasn't quite the fastest, its guns weren't quite the biggest, its armor wasn't quite the thickest, but by multiplying the weight of the ship by the length of its guns and dividing by something else you get an index number for the biggest worst ship ever. The Yamamoto and the Bismarck were perhaps a little bigger, but the New Jersey was at least the fastest meanest un-sunk battleship. Air power and nuclear submarines put the battleship out of business so the New Jersey will hold the world battleship title for all time. Strange, when you see it from the Ben Franklin Bridge, it looks comparatively small, even though it could blow up Valley Forge without moving from anchor.

One story is told by Chuck Okamoto, a member of the Green Berets who was sent with a group of eight comrades into a Vietnamese army compound to "extract" an enemy officer for interrogation. When enemy flares lit up the area, it was clear they were facing thousands of agitated enemy soldiers, and Okamoto called for air support. He was told it would take thirty minutes; he replied he only had three minutes, and to his relief was told something could be arranged. Almost immediately the whole area just blew up, turned into a desert in sixty seconds. The guns of the New Jersey, twenty miles away, had picked off the target. The story got more than average attention because Okamoto's father was Lyndon Johnson's personal photographer, and Lyndon called up to congratulate.

A number of similar stories led to the idea that naval gunfire might have destroyed some bridges in Vietnam which cost the Air Force many lost planes vainly trying to bomb, but, as the stories go, the Air Force just wouldn't permit a naval infringement of its turf. This sort of second-guessing is sometimes put down to inter-service rivalry, but it seems more likely to be just another technology story of air power gradually supplanting naval artillery. Plenty of battleships were sunk by bombs and torpedo planes before the battleship just went away. If you sail the biggest, worst battleship in world history, naturally you regret its passing.

Tourists will forever be intrigued by the "all or nothing" construction of the New Jersey. Not only are the big guns surrounded by steel armor three feet thick, but the whole turret for five stories down into the hold is also similarly encased in a steel fortress. This design traces back to the battle of Jutland, where a number of battlecruisers were blown up because the ammunition was stored in areas of the hold not nearly so protected as the gun itself. Putting it all within a steel cocoon lessened that risk, and had the side benefit that when ammunition accidentally exploded, the damage was confined within the cocoon. It must have been pretty noisy inside the turret when it was hit, sort of like being inside the Liberty Bell when it clangs. But not so; stories have been told of turrets hit by 500-pound bombs which the occupants didn't even notice. The term "all or nothing" refers to the fact that the gun turrets are sort of passengers inside relatively unprotected steering and transportation balloon. In order to save weight, most of the armor protection is for the gun. That's a 16/50, by the way. Sixteen inches in diameter, and fifty times as long. With the weight distributed in this odd manner, the Iowa class of dreadnought was more likely to capsize than to sink. Accordingly, the interior of the hull is broken up into watertight compartments, serviced by an elaborate pumping system. Water could be pumped around to re-balance a flooded hull perforation, certainly a tricky problem under battle conditions.

Bergdoll the Rich Draft Dodger

|

| Grover Cleveland Bergdoll |

Grover Cleveland Bergdoll was one of the great playboys during the era between the Spanish American War and World War I. Although the money came from his beer-baron father, he was in the newspapers as one of the early owners of an airplane, one of the dare-devils racing about in open cars, and of course successful with girls.

His father Louis (1825-94) had emigrated from Germany, bringing with him the new technique of making lager beer by brewing it in the cold, and quickly exploiting its popularity into thousands of barrels of beer a day. Although it is always hard to say just who invented a technique like that, there seems little doubt that Bergdoll & Schemm was responsible for transforming the area north of Spring Garden Street into a booming area of breweries, consuming huge amounts of ice and ice water, wood staves for beer barrels, horses to drag beer to the beer gardens, and energizing railroads to import raw materials and carry away the barrels of beer. The refrigeration industry flourished and spread out into air conditioning. Bergdoll was a mighty force in Philadelphia industry.

|

| Bergdoll Mansion |

The Bergdoll house was located on 21st Street, not far from the Eastern State Penitentiary, in the very upscale neighborhood called Fairmount. The neighborhood was isolated by the "Chinese Wall" of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and more importantly by the slashing through of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Eventually, the advent of Prohibition destroyed Philadelphia's brewery industry and its associated beer gardens. The Fairmount region declined into a slum, particularly after the 1929 Stock Market Crash, and upper crust Philadelphia fled blocks and blocks of huge mansions, too big to heat and clean, and also too big and substantial to tear down. So the Bergdoll mansion has been there all along, but there was just no one around to look at it. With the gentrification of the Fairmount region at the turn of the 21st Century, there it sits. a brownstone Pyramid, or Parthenon. A lot of wild stories circulate in the neighborhood, but very few of the new neighbors know very much about it.

It's just possible that the brownstone Widener mansion on North Broad Street is bigger, and certainly the Elkins, Stotesbury and Montgomery mansions in the far suburbs are a lot bigger. But this brownstone edifice in the center of town is impressively large enough to count for something, filling roughly half a square block if you include what look like stables of the same architectural style, and the double houses which suggest some members of the family lived next door. Even these smaller outbuildings are a great deal larger than the average city mansion.

|

| Bergdoll Mansion |

The size of the place makes it easier to understand how Grover Cleveland Bergdoll could be hidden there as a draft dodger for years. In fact, local rumor often has it that he stayed there for thirty years, but it was really only about three. A book by Roberta E. Dell, called The United States Against Bergdoll supplies considerably more detail. One has to suppose that this strongly German family was opposed to American participation in World War I, and the government's violent reaction to his draft objection reflected concern that the very large German-American population might rise up and interfere with Woodrow Wilson's decision to enter the War on the Allied side. In any event, Grover's mother hid him away in the extensive mansion complex until that war seemed safe over, but he was immediately apprehended and put on trial when he emerged. Somehow or other, he managed to convince the authorities that he should be released under guard in order to go dig up an enormous fortune in gold that he had buried. The agents guarding him were put up as guests in the big mansion, apparently unable to resist the big treat. But it was a ruse, a getaway was waiting and off he sped, ending up in exile in a little town a few miles from Heidelberg, Germany. It was there that he married a local German girl and spent an apparently comfortable exile until after the Second World War. There were rumors and stories, however. A couple of kidnappers broke in on him in an apparent effort to take him over the French border, but Bergdoll killed one of them. Even after World War II, all was not forgiven; he came home, was immediately apprehended and tried, and spent a brief time in jail. He died in 1966.

Those who are sufficiently fascinated by his story, can even live in his house. It's been renovated, and rents out as Bergdoll Mansion Apartments.

Brandywine Museum

|

| Wyeth Ann's House |

Artistic talent must be inherited; some of us don't have any at all, while other families seem to have unusual talent in every member. Around Philadelphia, one notable example is the Peale family, and another is the Wyeth clan. Three generations of Wyeth's show their work as a group in a former Brandywine Creek grist mill which has been elaborately restored and enlarged for the purpose. Using large glass windows, part of the display is the Brandywine Creek itself, with the high banks that once made it seem like a perfect defense line for George Washington in the biggest battle of the Revolutionary War. Outside the museum entrance are several of those inevitable Delaware tip-offs, large millstones that may in this case have ground grist, but often were used to grind gunpowder.

|

| Andrew Wyeth |

Andrew Wyeth spent much of his early career doing watercolors and then turned to tempera as re-popularized by N.C. Wyeth, his father. That's a fairly drastic change, since a watercolor must be completed in one sitting before it dries. Oil base paint dries slowly and allows the painter to work on a piece for a number of days. Tempera, using the protein in milk and eggs to hold the pigment, dries hard and fairly quickly. But another layer of tempera can be painted on top of the hardened base layers, making a glowing effect possible, a peculiar luminosity if the artist chooses to bring it out. Andrew Wyeth migrated to what he called dry-brush, where the paint on the brush is mostly squeezed out, so extremely detailed fine lines can be painted. Thus, he spent his early years with fast blurred watercolors, and the rest of his life with meticulous slow painting, where detail is everything. He chose to use this technique to produce a haunting silent scene, even if it contained people. His son, Jamie, tends to emphasize dancers so you can see the typical family rebellions alternating between generations, at the same time that the Wyeth's (and Howard Pyle, the artistic forefather) preserve strong family unity. From what the neighbors say, there were plenty of family clashes, but that's artists for you.

Canaris and Lahousen

|

| Harry Carl Schaub |

Our member, Harry Carl Schaub, J.D. is the Austrian Consul-General in Philadelphia, was once a member of the American Intelligence Service and is now Of Counsel to the Montgomery, McCracken law firm. In recent years, he has taken an interest in the German Intelligence Service during World War II, and with sufficient prodding intends to write a book about the astonishing betrayal of the Nazi effort by the Chief of their Intelligence Service, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. Canaris enlisted the top fifty officers of the Abwehr, the Intelligence Service, in his conspiracy to defeat and overthrow the Nazi leadership. All fifty -- except for one, Colonel Erwin Lahousen, Edler von Vermont -- were caught by the Nazis and executed in gruesome ways, after the plot was exposed by the failure of a bomb in Hitler's headquarters to eliminate the top Nazis. Lahousen was the first witness called by the Nuremberg Trials.

|

| Admiral Wilhelm Canaris |

Admiral Canaris, called the "most knowledgeable man in Germany" , reached his position of Intelligence Chief of the Third Reich as a result of distinguished naval service in World War I, much solidified internationally by his secret negotiations to persuade General Franco to bring the Spanish Moroccan Army to start and win the Spanish Civil War in Spain itself. (Several prominent Philadelphians were involved in these maneuvers, notably William Bullitt.) Canaris was an aristocrat and saw to it that at least the top fifty officers of the Abwehr were also aristocrats hostile to the Nazi regime, using professionalism as an excuse for the exclusion of any officer with Nazi sympathies in the service under his command. Canaris was slowly filling in the blanks in his plans, for years.

|

| Adolf Hitler |

The military aristocracy was convinced that by 1940, Germany had already won the war in Europe, with only Great Britain left standing unconquered, and an alliance with the Russians protected the Eastern Front. Canaris was close enough to Hitler to believe he was stark raving mad, and as a result of recklessness and blind ambition was about to embark on the two things which professional soldiers had been trained to fear most: a betrayal of the Russian allies and counter-invasion by them, and a land-sea invasion of England. Hitler, for no purpose they could imagine, was about to discard a complete victory in continental Europe and enter into a two-front war. Later on, Hitler committed another gross stupidity in their eyes, of declaring war on America after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. This entirely unnecessary action by Hitler allowed America to follow an established principle of warfare, which is to attack the strongest of your enemies first. Added to what they saw as appalling blunders of getting into a two-front war while stirring up civilian disloyalty with their Jewish, Gypsy and homosexual extermination campaigns, the man they could personally see was mentally unstable was about to convert total German victory into total German defeat. Some of these things might prove to be successful, but sooner or later this madman was going to lead Germany into a catastrophic defeat, so he must be removed before that could happen. While it still remains almost unbelievable that such high-placed officers could risk their lives to betray their own leader, their analysis was absolutely accurate, and correctly predicted the decades of devastation Germany would endure if Hitler could not be overthrown.

|

| Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg |

And they were probably quite accurate in predicting their own punishments if they failed. Lahousen escaped because he had been assigned to a combat division and was lying severely wounded in a hospital before von Stauffenberg's bomb failed to go off properly in Hitler's staff room. The Gestapo rounded up every other member of the fifty conspirators and tortured them to death, mostly by impaling them on meat hooks. No doubt, they also exterminated a great many innocents, just to be sure they did not miss any conspirators. Canaris himself was strangled to death four times, by the process of reviving him just before he died, and then strangling him again.

|

| Erwin von Lahousen |

And, indeed, Lahousen was apparently even mistreated as a prisoner by the British. During the war, one of Lahousen's projects was to stir up the Irish Republican Army in Great Britain, and indeed the guerrilla warfare between the IRA and the Protestant section of Northern Ireland lasted more than twenty years after the end of the war. The Brits were not amused.

Field Marshal William Joseph Slim, 1st Viscount, Order of the Garter

|

| Field Marshall William Joseph Slim |

It's impossible to be accurate about such rankings, but it must mean something when Field Marshall William Slim is the only officer of World War II to be ranked among the ten greatest generals of all time. The historian Ray Callahan recently described Slim's career to the Right Angle Club, with particular emphasis on how unlikely it was for a man of his humble beginnings even to be a Lieutenant in the British Army before World War I, how he endured pretty insufferable snubs along the way up the ladder of command, and how at the end of his career to be Chief of Staff he finally revealed that he had noticed those snubs, all right. Americans would be astonished at such class distinctions in their own army, and even raise the question how the British Army could possibly conquer the world for two hundred years with so little emphasis on merit selection of its generals.

First, the military story of Bill Slim. Before World War I, officer candidates were expected to pay for their own training, and he managed to get through a local college Officer Training course without enrolling in the college. Even that much training suddenly was in very short supply as Britain mobilized for the War, and he was commissioned with the limitation of "hostilities only" to emphasize that he was not in the "regular" Army. Working through the Mesopotamian campaign, he rose through the Indian Army, which Winston Churchill regarded as definitely second tier, with his permanent rank always lagging several levels below his "temporary", acting, rank. At one point, he received an official rebuke for advocating air power for ground support, since that was the turf of the Air Force, and on another occasion for irritating the Navy by using boats. When World War II suddenly sent Japanese forces plunging through Malaysia and Indo-China, Slim distinguished himself by keeping the defeated Indian Army intact through a 900 mile retreat into Burma, justifying his later memoir of turning Defeat Into Victory. During that demoralizing time, he had ample opportunity to observe the repeated Japanese tactic of launching lightning attacks without an established supply line, intending to live on the abandoned supplies of enemies as they were outflanked or surrounded by rapid advances. Slim developed the idea that if he's surrounded troops could be resupplied by air and hold out, the attacking Japanese would essentially starve to death in the jungle. One attacking Japanese army unit of 87,000 men was reduced to 13,000 survivors by the application of this strategy, and as long as the Japanese kept using their technique, Slim kept using his. One reverse variant of this use of air supply was employed by Slim in the recapture of Rangoon by himself attacking from the rear without the usual overland supply line, but resupplying by air as an approaching monsoon cut off the expected resupply by sea. After the war was over, Winston Churchill's history of the war's events contained only the briefest mention of these victories. When Slim finally met Churchill, a close election was taking place, and Churchill said he hoped the overseas ballots were cast for him. "Well, Prime Minister, I must say that no officer in my command voted for you," was the reply he got. When Churchill's successor Clement Attlee was told by Bernie Montgomery that the Chief of Staff position was promised to someone else, the terse order was, "Well, unpromise him." And Slim got the job.

|

| Sir Francis Drake kneeling to Queen Elizabeth |

So, Ray Callahan the historian was asked the typically American question of however could the British Empire conquer Napoleon or plant the British flag over most of the world, using a system that would deliberately hold back an officer of Slim's talents, snubbing and intentionally humiliating most of the nation whenever one of the lesser orders was cheeky enough to aspire to military leadership. With great patience, Callahan replied that this system of placing aristocrats in charge of the military was designed to maintain civilian control against the military uprising. There might have been a time when King Arthur or King Henry V was personally in charge of the Army, but King Macbeth and General Cromwell both illustrate the disadvantages of a fully feudal system. Even before the Industrial Revolution, military skill did not translate well into the skills needed to run an industrialized country but nevertheless provided an easy route for a power-hungry military to seize the crown. It is true that America tends to elect prominent generals to be president after each of our major wars (Washington, Jackson, Harrison, Grant, and Eisenhower) and indeed most other presidents have had some military experience. But ever since George Washington made the principle clear, there has been a prevailing imperative about maintaining civilian control of the serving military, which even the American military seem to agree with. So it is not surprising that other nations with some more bitter experiences to recall insist on more than social pressure to maintain civilian control. Inherited wealth not only provides genetic advantages and a de-glamorized experience with power, but it tends to create its own local environment which regards power as scarcely worth striving for, power is what you have, not what you strive for, there's not a great deal to gain from overturning things. While not inordinately brilliant, hereditary aristocrats are not inordinately stupid, either; they produce their share of Wellingtons, Patton and Macarthurs.

In the first World War, however, the British discovered a serious flaw in the aristocratic system. Most defenders of that system will stress the high morale developed within the comradeship of a 1000-man regiment, carefully selected to choose individuals who "fit in". The British Army has been described as a "loose federation of regiments", collecting the history and traditions of the British Army in a way best understood in America by noting the special fervor of the U.S. Marine Corps. There is an undeniable disadvantage, however. In a mass mobilization, following a selective mass slaughter of volunteers (90% of British Regular Army officers were casualties in World War I), there simply may not be sufficient numbers in the historic regiments to run an effective mass army. That is the implied recognition behind the creation of officers for the duration of hostilities, only; get rid of that sort when the war is over because they can become a threat to cohesiveness. Some of that concern surely runs through the steady drumbeat to take guns away from the public, Second Amendment notwithstanding, repeal that damned thing if you have to. And the converse runs through the thinking of the Second Amendment supporters; you never know when some power freak might seize control of the military. The southern half of the country leans more strongly in that direction. They remember the experience of Reconstruction when official reins of power were in hostile hands. The Old South really likes the idea of its sons running all branches of the military at all levels. Makes a fellow more comfortable with having a strong government.

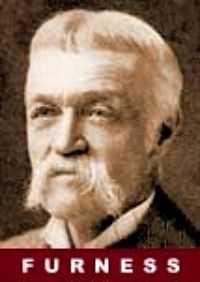

Frank Furness,(3) Rush's Lancer

|

| Frank Furness |

Lunch at the Franklin Inn Club was recently enlivened by David Wieck, who not only does the sort of thing you get an MBA degree for but is also a noted authority on the Civil War. His topic was the wartime exploits of Frank Furness, whose name is often mispronounced but whose thumbprints are all over the architecture of 19th Century Philadelphia. Take a look at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy, the Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania, and many other surviving structures of the 600 buildings his firm built in 40 years. One of them is the Unitarian Church at 22nd and Chestnut, where his grandfather had been the fire-brand abolitionist minister.

|

| PennsylvaniaAcademy of Fine Arts |

The Civil War seems to have transformed Frank Furness in a number of ways. He had been sort of in the shadow of his older brother Horace, a big man on the campus of Princeton, later the founder of the Shakspere Society, and the Variorum Shakespeare. Frank was quiet, and good at drawing. However, at age 22 he was socially eligible to join Rush's Lancers, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which contained among other socialites the great-grandson of Robert Morris, and a member of the Biddle Family who put up the money to equip the troop with 7-shot repeating rifles. Cavalry units like this were a vital weapon in the Civil War because they needed young well-equipped expert horsemen with a strong sense of group loyalty. Rifles were considered too expensive for infantry, who were equipped with muskets that took several minutes to reload, and were unwieldy because they were only accurate if they were very long. When bands of daredevils on horseback suddenly attacked with seven-shot repeating rifles, they could be devastating against massed infantry. A flavor of their bravado emerges from their rescue of General Custer's men from a tight spot, later known in the annals of the troop as "Custer's first last stand."

|

| The Undine Barge Club Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy |

There are two famous stories of the exploits of Frank Furness, first as a second Lieutenant and later as a Captain at Cold Harbor two years later. In the first episode, a wounded Confederate soldier lay on the no man's land of forces only a hundred yards apart. His screams were so heart-rending that Furness ran out to him and put a handkerchief tourniquet around his bleeding thigh. Because the fallen man was a Confederate soldier, the Confederates held their fire and later cheered the Union cavalryman for his kindness. The wounded man called out "

|

| The Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania |

In the second episode, the cavalry had spread out too much, leaving some isolated parties trapped and out of ammunition. Furness lifted a hundred-pound box of ammunition to his head and ran through the gunfire with it to the trapped men. For this, he later received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Somehow all of the public attention he received in the war transformed Furness from a younger brother who was good at drawing into a dynamo of energy, much in the model of what law firms call a "rainmaker". He traveled to the Yellowstone area of Wyoming at least six times, bringing back various trophies. He was known to get people's attention by using his service revolver to take pot shots at a stuffed moose head in his office.

|

| First Unitarian Church 22nd Chestnut Philadelphia |

His final publicity venture was to advertise, forty years later, in Southern newspapers for the whereabouts of the Confederate soldier whose life he had saved. Eventually, a man named Hodge who had later been a sheriff in Virginia, stepped forward to renew his blessings and thanks. Hodge was brought to Philadelphia for a celebrated 6th Cavalry reunion, and a picture of the two former enemies was spread in the newspapers. It was a little embarrassing that Furness and Hodge found they had very little to say to each other for a five-day visit, but Hodge eventually proved able to be one-up in the situation. He outlived Furness by five years.

Although the style of Furness confections seemed and seems a little strange to everyone except Victorian Philadelphians, he did leave a major stamp on American architecture. His most noted student was Louis B. Sullivan, who put an entirely different sort of stamp on Chicago. And Sullivan's best-known student was Frank Lloyd Wright who created a modernist image of architecture for the West. The buildings of these three don't look at all alike, but their rainmaker personalities are all essentially the same.

Franklin Bets His Wad on General Braddock

|

| General Edward Braddock |

The defeat of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) in 1755 was not a turning point of the French and Indian War, because although the French won the battle, they lost that War, they also lost Canada in the Seven Years War that followed, and eventually had to sell what remained of their American dream in 1804 as the Louisiana Purchase. The French dream was an empire stretching in an arc from the St. Lawrence River to New Orleans, leaving the British only the thirteen Eastern seaboard colonies.

Nevertheless, the disastrous defeat of the Redcoats was a real turning point in the attitudes of two direct participants, Lieutenant Colonel George Washington of Virginia, and Pennsylvania's political leader, Benjamin Franklin. Both men greeted the arrival of Braddock's troops in America with great relief because it was increasingly evident to them that the Colonies themselves were too indecisive to survive. Both of them were in a unique personal position to see that the French and their Indian Allies were serious about conquering the backcountry, even likely to do so. These two staunch British patriots, therefore, threw themselves into the crisis, with Washington eventually having two horses shot from under him, taking charge of the retreat after Braddock's death. And Franklin pledged his considerable personal fortune on Braddock's behalf, almost losing it and spending the rest of his life in debtor's prison as Robert Morris would later actually do. These two men knowingly laid their lives on the line for the British Empire and came very close to losing everything else for their King and country.

Franklin had retired seven years earlier, a rich man at the age of 42. We now know that he lived like a gentleman for another 42 eventful years. Puttering with science and public works, he joined the Assembly in 1750. It was not long before he was the political leader of the Colony, in a peculiar struggle with the dominant Quaker party who not only opposed war for their own self-defense but were enraged that the Penn family had turned away from Quakerism and refused to be taxed for the defense of its colony. The Governor was appointed by the Penns, with an express contract not to agree to any taxation of the Penn holdings. Since it began to look to Franklin as though everybody was trying to commit suicide rather than spend a farthing, he greeted the arrival of General Edward Braddock's redcoats with great relief. But then Braddock himself turned out to be a brave but exasperating ninny.

Braddock's plan was to take the old Indian trail from the Potomac River to the Monongahela (now Route 40), fording the Monongahela just below its junction with Ohio at Fort Duquesne, then blowing up the French fort with artillery. He had brought plenty of troops and cannons on his ocean transports, but he needed horses and wagons from the colonies. When he was warned of the dangers of Indian ambush in the wilderness, he made a much-quoted response, "These savages may be a formidable enemy to your raw American militia, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops, sir, it is impossible they would make an impression." The other thing he said was if he didn't get wagons and horses pretty damned quick, he was going back home to England.

Within two weeks, Franklin and his son William collected 259 horses and 150 wagons for him. But to do so, they had to overcome the Pennsylvania farmer suspicion that the swaggering English General wouldn't pay for the goods. To persuade them, Franklin made a public pledge to stand behind the debts with his own money, and his word was known to be good.

The other thing wrong with Braddock's plan was that the trail wasn't wide enough for the wagons and gun carriages, so he had so sent a body of axeman ahead of the troops to widen the road. Progress was at times as slow as two miles a day, plenty of time for word to be taken to Fort Duquesne that the British were coming with cannon. Since it was clear that the Fort could not withstand a siege army, the French commander ordered his troops to attack Braddock as he was crossing the Monongahela. It was meant to be an ambush, but the two armies blundered into each other on the trail, and the Indians simply fought the way they knew best, from behind trees. Two-thirds of the British were killed and most of those captured were burned at the stake. The death toll would have been even higher, and probably would have included Washington, except the Indians, ignored French orders and delayed pursuit to collect scalps. And by the way, all of Franklin's wagons were burned.

Franklin spent an anxious two months since his later reflection was that the loss of 20,000 pounds sterling would surely have ruined him. However, he was lucky that Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, an old friend of his, was appointed at Braddock's successor, and Shirley ordered the debt to be repaid out of Army funds.

The American Revolution would not come for another twenty years, but you can be sure the Braddock episode had an important impact on the minds of both Franklin and Washington. The British Army was not invincible. It was not even very smart.

Franklin: Upstart Hero of King George's War (1747)

In 1747, Benjamin Franklin had a life-transforming experience, acting quite unlike his character before, or later. At that time, Old Europe was engaged in some distant tribal skirmishing which has come to be known as King George's War. King George II, that is, under whose rule Franklin in 1751 inscribed on the cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital that Pennsylvania was flourishing, "for he sought the happiness of his people."

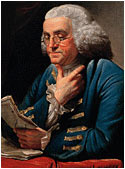

|

|

The cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital inscribed by Franklin. |

Those distant commotions suddenly developed a harsh reality for the little pacifist sanctuaries on the Delaware River, when French and Spanish privateers suddenly raided and destroyed settlements on Delaware Bay. The Quaker Assemblies and their absentee Proprietor merely dithered and huddled in the face of what impended as a totally unexpected threat of annihilation of the pacifist colonies. It probably only seemed natural for the owner of the largest newspaper in the colony to publish a pamphlet called "Plain Truth," urging the inhabitants to rally to their own defense, and pressure their government to lead them. The Quaker leaders were in fact unable to readjust a lifetime of pacifist belief in a few days of an emergency, and the English Proprietor, then Thomas Penn, was far too remote to take active charge of matters. So, Franklin gave speeches, also an unfamiliar role for him, and finally brought out a detailed proposal for the creation of a Pennsylvania Militia. Ten thousand volunteers promptly signed up, elected Franklin as their Colonel; but he declined, and served as a common soldier.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in 1767. |

Against naval attack, the Militia needed cannon, which did not exist in the colony. So Franklin organized a lottery, raised three thousand pounds, and tried to buy cannon from Governor Clinton of New York. New York declined to sell, and so Franklin led a delegation to New York to negotiate. The negotiations largely consisted of getting Governor Clinton drunk and convivial, but they were successful, the artillery was shipped off to Philadelphia. Although they were undoubtedly grateful to Franklin for saving the day, this entirely extra-legal recruitment of an army badly rattled the Quakers and their Proprietor, since it demonstrated the ineffectiveness of their governance at a time of obvious crisis, and might ultimately have led to their overthrow. Franklin's heroic behavior seemed so threatening to Thomas Penn that he described him as "a dangerous man," acting like "the Tribune of the People."

When the underlying commotion in Old Europe subsided, the threat to the colonies disappeared, so the Militia disbanded in a year. Franklin seemed to be just as uncomfortable with his unaccustomed role as the governing leaders were, and he hardly ever mentioned it again. However, this is the sort of reflex leadership which makes political careers, and it surely influenced his decision to retire from business in 1748, run for election to the Assembly, and live like a gentleman. Seven years later, during the French and Indian War, he had become the chosen leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly, had much longer to think through what he was doing, and had learned how to organize a war. By that time, as the saying goes, he knew who he was. He was a man whose silent memories could flashback to that time when a bald fat printer stepped out of the crowd, saying "Follow me," and ten thousand men with muskets did so.

George Washington's View of the British Army

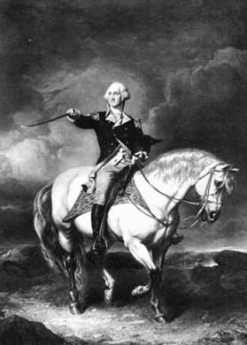

|

| George Washington |

TWO things about George Washington continue to puzzle us. Why would the rich, aristocratic Virginia gentleman become a revolutionary? And, how could he or his backwoodsmen soldiers even imagine they could defeat the British, the greatest military force in the world? The following letter, written to his mother after the defeat of Braddock's army, shows his viewpoint at the age of 23, putting the British regular army in a very bad light, indeed.

"HONORED MADAM: As I doubt not but you have heard of our defeat, and, perhaps, had it represented in a worse light, if possible, than it deserves, I have taken this earliest opportunity to give you some account of the engagement as it happened, within ten miles of the French fort, on Wednesday the 9th instant.

"We marched to that place, without any considerable loss, having only now and then a straggler picked up by the French and scouting Indians. When we came there, we were attacked by a party of French and Indians, whose number, I am persuaded, did not exceed three hundred men; while ours consisted of about one thousand three hundred well-armed troops, chiefly regular soldiers, who were struck with such a panic that they behaved with more cowardice than it is possible to conceive. The officers behaved gallantly, in order to encourage their men, for which they suffered greatly, there being near sixty killed and wounded; a large proportion of the number we had.

"The Virginia troops showed a good deal of bravery and were nearly all killed; for I believe, out of three companies that were there, scarcely thirty men are left alive. Captain Peyrouny and all his officers down to a corporal were killed. Captain Polson had nearly as hard a fate, for only one of his was left. In short, the dastardly behavior of those they call regulars exposed all others, that were inclined to do their duty, to almost certain death; and, at last, in spite of all the efforts of the officers to the contrary, they ran, as sheep pursued by dogs, and it was impossible to rally them.

"The General was wounded, of which he died three days after. Sir Peter Halket was killed in the field, where died many other brave officers. I luckily escaped without a wound, though I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me. Captains Orme and Morris, two of the aids-de-camp, were wounded early in the engagement, which rendered the duty harder upon me, as I was the only person then left to distribute the General's orders, which I was scarcely able to do, as I was not half recovered from a violent illness, that had confined me to my bed and a wagon for above ten days. I am still in a weak and feeble condition, which induces me to halt here two or three days in the hope of recovering a little strength, to enable me to proceed homewards; from whence, I fear, I shall not be able to stir till toward September; so that I shall not have the pleasure of seeing you till then, unless it be in Fairfax... I am, honored Madam, your most dutiful son."

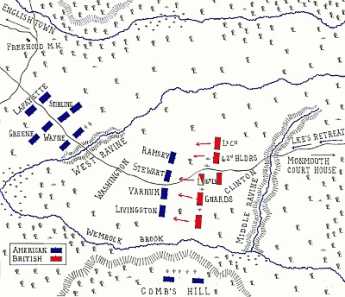

Gettysburg

|

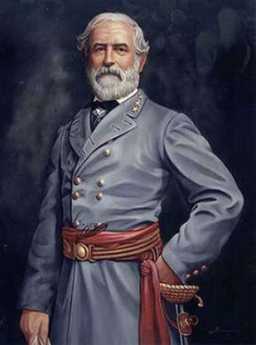

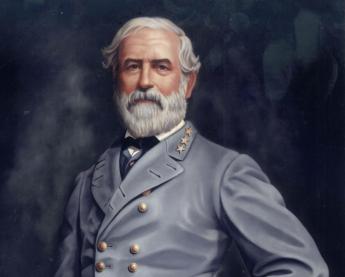

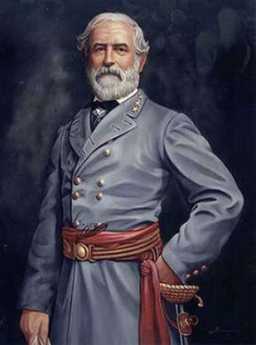

| General Robert E. Lee |

It's quite a long drive from Philadelphia to Gettysburg, but General Lee was attempting to disrupt supplies to the "Arsenal of the North" by capturing the railroad center at Harrisburg. Furthermore, Philadelphia reacted as if Lee's advance was aimed straight at us, creating hysterical preparations for an invasion which had to be stopped before it got here. And finally, George Gordon Meade, the Union commander, was a Philadelphia home town boy. So, regard the Battle of Gettysburg as part of Philadelphia history, please.

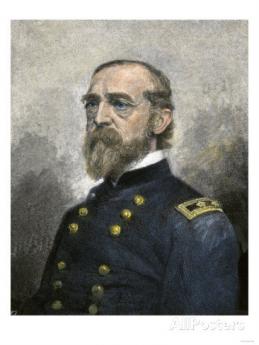

|

| General George Gordon Meade |

Major (ret.) Lawrence Swesey is a West Point graduate and currently Administrator of the 1st City Troop; because of his enthusiasm for the subject, he runs a tour agency which specializes in battlefields, especially Gettysburg. From him, the Right Angle Club recently learned much that made the whole episode comprehensible. Such as Lee's purpose in going there, which appears to have been based on the growing recognition that the South was likely to lose the war, and desperately needed some major victory in Northern territory, both to take the pressure off the Southern homeland and to improve whatever terms might be extracted at a peace negotiation. To fight successive battles against a larger enemy, with larger economic resources, was to doom the South eventually as resources and men were depleted with no hope of replacing them. Sooner or later, some Union General like Grant would settle down to a grinding unrelenting assault, with the willingness to trade one death for another, until only the larger side was left standing. That's quite different from guerilla warfare of the type Washington fought, where the way to win was simply to avoid losing until the stronger side lost its civilian support. Lee could feel the South beginning to lose its nerve to fight on indefinitely, without any visible route to victory. Although Grant eventually did defeat him by attrition, Grant's own opinion appears to have been more personalized. In every war, he was later to say, there comes a time when both sides want to quit. The side that wins is the one with a general who keeps fighting for no particular reason until the other side finally quits and he wins the war.

Major Swesey emphasizes that rifles were available, but they cost four times as much as smooth-bore muskets which were only effective for twenty or thirty yards. Rifles were reserved for sharpshooters, and the enemy at a distance was bombarded by artillery as the two sides approached. So, in Pickett's famous charge, most of the casualties took place in the last fifty yards. Pickett's men had to contend with trudging stoically through an exploding field of cannon fire, unable to fire effectively at the Union men behind a stone wall, who were also supposed to lie passively on the ground while the Confederate artillery pounded at a stationary target. Somehow, most of the Southern artillery fire went over the Union heads and landed beyond the crouching line; in many ways, this was the main factor in the Union victory.

As the waves of attackers got within musket shot of the wall, they formed into three ranks. Since it took about a minute to reload the musket, a more or less continuous fire could be maintained by rotating three successive volleys rank by rank, at more or less point blank range. Then, fix bayonets, and the real slaughter became a hand to hand, in the blazing heat of summer.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1436.htm

Home of the U.S. Naval Academy

Gray's Ferry, the first non-swamp ground as you come up the Schuylkill, is the oldest part of Philadelphia, and one of the saddest. This was the place where Washington and the other Southern delegates came to the Continental Congress along the main North-South route of the Colonies. John Bartram's gardens are nearby, and Andrew Hamilton's mansion. But things are in a sorry state nowadays, and neighborhood residents believe it is unsafe even to drive through there. Of all the areas in the city, this one cries out most for rehabilitation.

Well, Toll Brothers, the mass builders, are doing something there. Almost any construction, or any demolition, would seem like an improvement. But you have to hold your breath when you see bulldozers in the old Naval Home, a large and stately building along the river, hidden behind a long wall. Some pretty old and historic buildings are in danger of being torn down.

This was, for example, the original home for six years, of the United States Naval Academy. You know, the one that is now at Annapolis. Doesn't anyone care?

John Dickinson, Quaker Hamlet

|

| John Dickinson |

John Dickinson (1732-1808) would probably be better known if his abilities were less complex and numerous. It would have been particularly helpful if he had consistently remained on only one side of the important issues of his day. Born in a Quaker family and buried in a Quaker graveyard, he was for years a notable Episcopalian and soldier. He outwitted John Penn, the Pennsylvania Proprietor who was trying to keep Pennsylvania from sending representatives to the Continental Congress, by having the Pennsylvania representatives hold a meeting in the same small room of Carpenters Hall at the same time as the Congress. But he ultimately refused to sign the Declaration of Independence. Although he was the main author of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution which replaced it would not have been ratified without his idea of a bicameral Congress. Although he was Governor of Pennsylvania, he was also Governor of Delaware, has been the central figure in the separation of the two states. In fact, for fifteen years he was a member of the Legislature of both states. Dickinson seems in retrospect to have been on every side of every argument, but he was immensely respected in his time.

Two events seem to have been central in the organization of his life. The first was his education as a lawyer. At that time and for a century afterward, lawyers were trained by apprenticeship. Dickinson, however, studied in London at the Inns of Court for four years and was by far the most distinguished lawyer in North America for the rest of his life. Furthermore, he absorbed the principles of the Magna Carta and the approaches of Francis Bacon so thoroughly that he never quite got over his pride in his English heritage. Throughout his leadership of the colonial rebellion, he acted as a better Englishman than the English themselves. His demand was for American representation in the British Parliament, not independence from England. It would not be hard to imagine Dickinson standing before a firing squad, gritting the words of St. Paul, Civis Romani Sum.

His other pivotal experience was the Battle of Brandywine. Dickinson had been the organizer or chairman of the two main Pennsylvania military organizations, the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety and Defense, and the so-called Associators (today's 111th Infantry, the first battalion of troops in Philadelphia). Both of these particular names were a characteristic gesture to conciliating pacifist Quaker feelings. Nevertheless, when Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration, he did temporarily become so unpopular he resigned his military commands. A few months later, when General Howe landed at Elkton at the narrow neck of the Delmarva peninsula, Dickinson enlisted as a common soldier to defend the southern perimeter of the defense line Washington had hastily thrown up to defend Philadelphia. Shortly afterward, Dickinson's friend and neighbor Caesar Rodney made him a Brigadier General in charge of the garrison around Elizabeth New Jersey, but the Battle of Brandywine taught an important lesson. Little states like Delaware and Maryland could not possibly defend themselves witho

Laurel Hill

|

| Laurel Hill Cemeteries |

There are two Laurel Hill Cemeteries in Philadelphia, sort of. Although both are described as garden cemeteries, the older part in East Fairmount Park is more of a statuary cemetery or even a mausoleum cemetery. When its 74 acres filled up, the owners bought expansion land in Bala Cynwyd, which could come closer to present ideas of a memorial garden. Particularly so, when the older cemetery area started to fill in every available corner and patch and began to look overcrowded. The name was used by the Sims family for their estate on the original area. Since June-blooming mountain laurel is the Pennsylvania state flower and a vigorous grower, it seems likely the bluff overlooking the Schuylkill was once covered with it. Somehow the May-blooming azalea has become more popular throughout the region, particularly in the gardens at the foot of the Art Museum. If extended a little, merged with laurel on the bluff, and possibly with July-blooming wild rhododendron, there might someday arise quite a notable display of acid-loving flowering bushes from the Art Museum to the Wissahickon, continuously for two or three months each spring.

There are interesting transformations in the evolving history of cemeteries, best illustrated in our city by the traditions of the early Quakers when they dominated Philadelphia.

|

| Thomas Grey |

Objecting to the ornate monuments which Popes and Emperors erected for their military glory, and probably to the aristocratic custom of burying important people inside churches where they could be worshiped along with the stained-glass saints, early Quakers were reluctant to mark their own graves with headstones, or even to have their names engraved on such "markers". By contrast with the splendor accorded aristocrats, the common people in Europe were largely dumped and forgotten, providing an unfortunate contrast. During the early part of what we call the romantic period, Thomas Gray popularized these attitudes in Elegy in a Country Churchyard. To be fair about it, the early Christian Church had a strong tradition of collecting the dead of all classes into catacombs. The Romans were quite reasonably upset by the potential for spreading epidemics through people living within such arrangements, although feeding the Christians to the lions seems like an overreaction.

At any rate, and to whatever degree the French Revolution was what shattered previous traditions, the Victorian or romantic period produced a new vision: garden cemeteries in Paris.

|

| George Mead |

The concept soon spread to Laurel Hill, and thence to the rest of America. Acting with what probably had some commercial motivation, cemeteries then moved away from churches to suburban parks, promoted as places of great beauty in which to stroll and hold picnics, perhaps to meditate. The private expense was not spared in statues and mausoleums, which often became display competitions between dry goods merchants and locomotive builders. Revolutionary heroes were dug up from their original graves and transported here to be more properly honored, as were some private persons whose descendants wished for more suitable recognition than conservative church rectors had offered. The Civil War created the staggering number of 632,000 war dead; based on the proportion of the population, that would be equivalent to six million in today's terms. Since they were almost all male, there must have been at least a half-million surplus women as a consequence. The nation and this almost unbelievably large cohort of single women had an impact on society for thirty or forty years after The War. Eventually, this would lead to colleges for women, suffrage and other forms of feminism, but the initial manifestations of what we now call Victorianism took the form of formalized grief, particularly the 75 National Cemeteries of crosses row on row. But private initiatives also took a variety of forms, including Laurel Hill's statuary to honor the valor of the fallen, ranked by the number of generals buried there and visits by sitting Presidents of the United States. Laurel Hill, East, holds 42 Civil War Generals. It will be recalled that Lincoln's Gettysburg Address was delivered at a much larger final resting place for fallen soldiers, but Laurel Hill had the generals, including George Gordon Meade, himself. It is probably significant that Laurel Hill West, three times as large, was opened in 1867. At the headstone of each Civil War veteran is found a metal flag-holder, put there by the Grand Army of the Republic and marked with GAR surrounding the number 1. This is the home of Post Number One, the Meade Post, the original home of this organization responsible for many patriotic movements like the Pledge of Allegiance and commemorative reunion encampments and reenactments. The main purpose of the war was to preserve the unification of a continental nation, and the GAR sought to raise patriotic consciousness to a point where fragmentation would never again be conceivable.

|

| John Notman |

Two names stand out in the history of these cemeteries, Notman and Bringhurst. John Notman was one of the early architects who fashioned the look and feel of Philadelphia. His identifying feature is brownstone, as seen cladding the Athenaeum building on Washington Square, and St. Marks Episcopal Church at 15th and Locust. At Laurel Hill, the main entrance confronts a brownstone sculpture by Notman of "Old Melancholy", depicting a typical Victorian romantic vision; just about all other monuments in the cemetery are either of acid rain-eroded marble or indelible granite. Brownstone from Hummelstown PA provided the characteristic look of New York residential architecture during this era. Philadelphia brownstone probably came from the same place. The other name is Bringhurst, dating back to 17th Century Germantown, long associated with the underlying sanitary purposes of the cemetery. The family finally and gladly sold the undertaking business a few decades ago.

Somehow, the image of cemeteries has now transformed from public places of meditation and reverence to places that are "spooky". Their greatest surge of visitors, these days, occurs at Halloween.

Lewis Harlow van Dusen, Jr. (1910-2004)

|

| Croix de Guerre |