2 Volumes

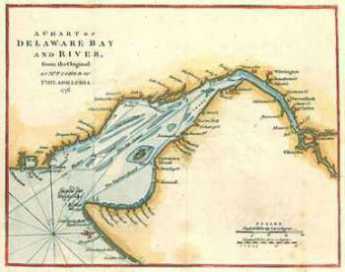

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Sights to See: The Outer Ring

There are many interesting places to visit in the exurban ring beyond Philadelphia, linked to the city by history rather than commerce.

Brandywine Museum

|

| Wyeth Ann's House |

Artistic talent must be inherited; some of us don't have any at all, while other families seem to have unusual talent in every member. Around Philadelphia, one notable example is the Peale family, and another is the Wyeth clan. Three generations of Wyeth's show their work as a group in a former Brandywine Creek grist mill which has been elaborately restored and enlarged for the purpose. Using large glass windows, part of the display is the Brandywine Creek itself, with the high banks that once made it seem like a perfect defense line for George Washington in the biggest battle of the Revolutionary War. Outside the museum entrance are several of those inevitable Delaware tip-offs, large millstones that may in this case have ground grist, but often were used to grind gunpowder.

|

| Andrew Wyeth |

Andrew Wyeth spent much of his early career doing watercolors and then turned to tempera as re-popularized by N.C. Wyeth, his father. That's a fairly drastic change, since a watercolor must be completed in one sitting before it dries. Oil base paint dries slowly and allows the painter to work on a piece for a number of days. Tempera, using the protein in milk and eggs to hold the pigment, dries hard and fairly quickly. But another layer of tempera can be painted on top of the hardened base layers, making a glowing effect possible, a peculiar luminosity if the artist chooses to bring it out. Andrew Wyeth migrated to what he called dry-brush, where the paint on the brush is mostly squeezed out, so extremely detailed fine lines can be painted. Thus, he spent his early years with fast blurred watercolors, and the rest of his life with meticulous slow painting, where detail is everything. He chose to use this technique to produce a haunting silent scene, even if it contained people. His son, Jamie, tends to emphasize dancers so you can see the typical family rebellions alternating between generations, at the same time that the Wyeth's (and Howard Pyle, the artistic forefather) preserve strong family unity. From what the neighbors say, there were plenty of family clashes, but that's artists for you.

Bristol, PA

|

| Burlington Bristol Bridge |

In 1681, Samuel Clift activated a local land conveyance, written to go into effect as soon as King Charles II signed the overall land grant to William Penn. In this way, Bristol claims to be the oldest settlement in English Pennsylvania; Clift got here before Penn did. He chose the narrowest spot in the river as an excellent place to run a ferry which was only replaced by the Burlington Bristol Bridge in 1930. A ferry landing is an excellent place for an Inn, which he also built there. The town he founded was called Buckingham, and the surrounding county became Buckinghamshire, Bucks for short. The name later changed to Bristol. The New Jersey town on the other end of the ferry ride was called Bridlington, later Burlington. North of this narrow spot in the river was a several-mile extent of marsh and swampy inlets, and then the river turns abruptly northwest at what used to be called the falls at Trenton.

William Penn had considered building his house sixty miles south of there at the Southern end of Philadelphia Bay, at Chester, then pondered building it on the Faire Mount where the Philadelphia Art Museum now overlooks the Schuylkill. In the end, he built a Philadelphia house near Dock Creek (subsequently covered over and renamed Dock Street) and a palatial manor house, Pennsbury, in the swampy marshes above Bristol, where a tourist visit is now a valuable experience.

|

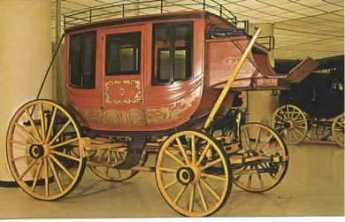

| Stagecoach |

No doubt being near the Proprietor's estate gave Bristol some class, but it was also half-way on a two-day stagecoach ride from Philadelphia to New York. A succession of inns and resorts grew up in Bristol, and it became a busy transshipment place, a good place to build schooners. A local Captain John Cleve Green is celebrated as first to carry the American flag to China, although it must be admitted his cargo included opium; Green is regarded as the financial founder of the nearby Lawrenceville School. The terminus of the Delaware canal brought coal from the anthracite region in 1827; more prosperity ensued as coal was loaded on ships in Delaware, or utilized instead of water power for the Bristol Mills which had been founded by Samuel Carpenter in 1701. John Fitch invented the first steamboat and tried it out here; more prosperity ensued, although not for poor Fitch, who committed suicide. Little Bristol gradually filled up with imposing waterfront mansions, the declining shells of which can still be admired.

|

| Bristol Railroad |

The advent of the railroad isolated Bristol when it cut off the corner of the bend in the Delaware River. Four-lane highways eventually consolidated the isolation of the little river town, but the turning point was around the time of the Civil War. For nearly a century, between the Revolution and the Civil War, Bristol was the booming little queen of northern Philadelphia Bay, and the Bay itself was an American Lake Como, lined with Federalist and Victorian mansions, their lawns sweeping down to the water's edge. Small wonder there was so much social interaction between the railroad-isolated Bristol, and planters of Chesapeake Bay. The strip of quiet charm begins at Pennsbury Manor and pretty continuously extends to Bristol, where you can go under the rail embankment and on to Philadelphia, or alternatively cross the Burlington Bristol Bridge to New Jersey. A couple of miles further south, the river edge is a little ragged but includes some yacht clubs and several famous mansions, notably Nicholas Biddle's Andalusia, the Foerderer family's Glen Ford, and the former mansion of Saint Katherine Drexel.

The Bristol area has had moments of fame. George Washington had originally planned to attack Trenton from both the north and the south simultaneously. He came over what is now called Washington's Crossing amid the ice floes on the north side of the Pennsbury delta, and General Cadwalader was to cross Delaware at Bristol, on the south side of the marshes. As it turned out, the ice was worse at Bristol and the river wider, so Cadwalader was late for Trenton but caught up with Washington to help with the battle at Princeton. President Tyler's daughter married a dashing gentleman from Bristol. Republican politicians from Bristol teamed up with some others in West Chester to decide that favorite-son Seward couldn't win, so they backed Abraham Lincoln for the presidential nomination, and Pennsylvania was therefore in time richly rewarded for its political acumen. Despite the arts and crafts group that moved in around New Hope PA, Bucks County has remained a Republican stronghold ever since. The region's influence was long symbolized by Joseph P. Grundy, the gentle Quaker manufacturer from Bristol whose name struck terror in Republican politicians as well as Democrat ones, but for opposite reasons.

The Burlington Bristol Bridge is now getting a little narrow and ancient, but is still serviceable. It long charged only a dime's toll because that was enough for painting and upkeep. Together with the Tacony Palmyra Bridge, which charged the same low toll, these locally owned bridges stuck a thumb in the eye of the tax-and-spend folks who owned the Philadelphia bridges and who wanted to charge three dollars toll, spending most of it on non-bridge activities. As Tacony Palmyra Bridge rests on both sides of the river, the local politics gradually shifted enough to permit a restoration of toll "equity".

British Headquarters: Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in its 1776 Heyday (B 608)

Not many now think of the town of Perth Amboy as part of Philadelphia's history or culture, but it certainly was so in colonial times. Sadly, the town has since declined to a condition of a quiet middle-class suburb. There are quite a few Spanish-language signs around and some decaying factories. The little house of the Proprietors on the town square and the remains of the Governor's mansion overlooking the ocean are about all that remain of the early Quaker era.

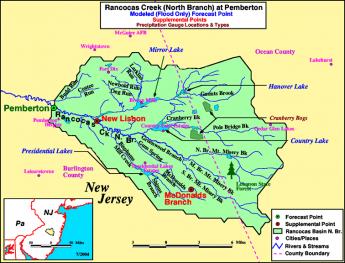

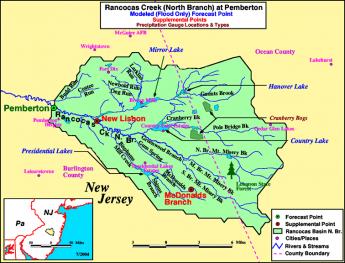

|

| NJ MAP |

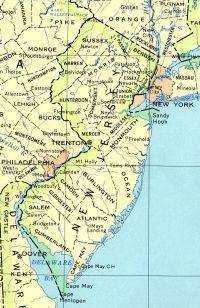

To understand the strategic importance of Perth Amboy to Colonial America, remember that James, Duke of York (eventually to become King James the Second) thought of New Jersey as the land between them North (Hudson) River, and the South (Delaware) River. This region has a narrow pinched waist in the middle. It's easy to see why the land-speculating Seventeenth Century regarded the bridging strip across the New Jersey "narrows" as a likely future site of important political and commercial development. The two large and dissimilar land masses which adjoin this strip -- sandy South Jersey, and mountainous North Jersey -- was sparsely inhabited and largely ignored in colonial times. The British in 1776 developed the quite sensible plan that subduing this fertile New Jersey strip would simultaneously enable the conquest of both New York and Philadelphia at the two ends of it. It was a clever plan; it might have subjugated three colonies at once.

|

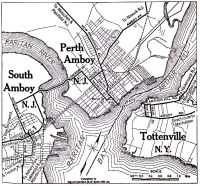

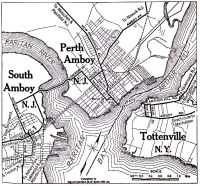

| PERTH AMBOY MAP |

Perth Amboy is a composite name, adding a local Indian word to a Scottish one because East Jersey had been intended for Scottish Quakers. Like Pittsburgh at the conjunction of three rivers, Perth Amboy's geographical importance was that it dominated the mouth of Raritan Bay (Raritan River, extended) as it emptied into New York Bay just inside Sandy Hook. Two of the three "rivers" of the three-way fork are really just channels around Staten Island. Viewed from the sea, Perth Amboy sits on a bluff, commanding that junction. Amboy became the original ocean port in the area, although it was soon overtaken by New Brunswick further inland when increasing commerce required safer harbors. Perth Amboy was the capital of East Jersey, and then the first capital of all New Jersey after East and West were joined in 1704 by Queen Anne. The Royal Governor's mansion stood here, as well as grand houses of Proprietors and Judges overlooking the banks of the bay. The main reason for the Nineteenth-century decline of the state capital region was the narrowness of the New Jersey waist at that point; its main geographical advantage became a curse. Canals, railroads and astounding highway growth simply crowded the Amboy promontory into an unsupportable state of isolation. The same thing can be said of Bristol, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware, but local civic pride has somehow not risen to the challenge to the same degree.

Pirate Lair

|

| Jolly Roger Flag |

Delaware takes a ninety-degree turn right at about the place where the Salem nuclear cooling towers are visible on the Jersey shore, and great quantities of silt have piled up in the river there, making marshes and swamps. There is a rumor that Captain Kidd tied up among these marshy islands, and much better evidence that Blackbeard the Pirate used the Delaware marshes as a hideout. Since a high-speed highway, with limited access, now rushes visitors to the slot machines of Dover and the beaches of Lewes, no one much notices that this area hasn't changed much from what it probably looked like three hundred years ago.

But if you take the old road, Delaware Route 9, you wander through the backcountry and are only likely to meet duck hunters. At one point, with a lake to one side and the river on the other, a watchtower has been erected for bird watchers and the like. It's very beautiful there, and quiet.

So one day I drove up, parked my car at the base of the tower, and climbed a hundred steps to the top. Blackbeard was not in evidence, but it was easy to see how he might feel pretty secluded in the coves and behind the trees. There were lots and lots of birds, interesting enough but mostly unidentifiable by me. Like most big-city lovers of the environment, I mostly classify birds as little brown jobs (LBJ) and big black buggers (BBB). And then a car drove up, with some chattering teenagers.

|

| Copperhead |

From a hundred feet up, it was hard to tell what they were saying, and it probably didn't matter much. Until suddenly one of the girls screeched out, "Oh look! There's a big snake under that man's car! "

One of the boys in the car shouted out, "That's a copperhead snake! I've never seen one so big!"

And so, they roared off into the distance, leaving the marshy paradise to me and the snake. What do I do now?

I waited, hoping the snake would go away. But it started to get dark, and now it was even more unattractive to chase around with snakes. So, creeping to the bottom of the stairs, I made a dash for the car door, jumped in, and slammed it tight.

As I drove away, I could not see any snake on the ground under the place where I had parked. To this day, I don't know if there really was a snake there or not.

Greenwich, Where?

|

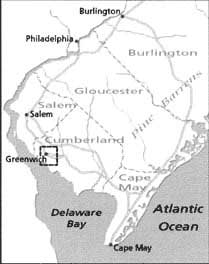

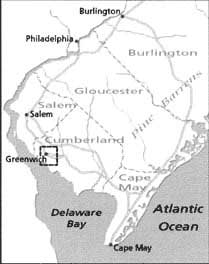

| Greenwich NJ |

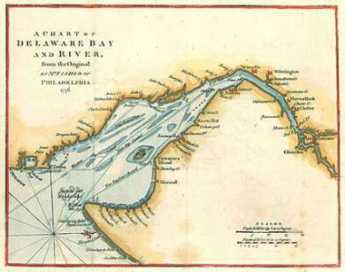

If you sail north up the Delaware Bay, you would go past Rehoboth, Lewes, Dover, New Castle, Wilmington -- on the left, or Delaware side. On the right, or New Jersey side, it's a long way from Cape May to Salem, the first town of any consequence. That is, the Jersey side of the riverbank is still comparatively uninhabited. When the first settlers came along, with vast areas to choose among, it might have seemed attractive to settle on the Delaware side, because the peninsular nature of what is now called Delmarva (Del-Mar-Va) would provide land access to two large navigable bays, the Delaware, and the Chesapeake. To go all the way up the Delaware to what is now Pennsylvania would give trading access to a whole continent, so that eventually proved to be where immigration was headed. But as a matter of fact, the marshy Jersey shore seemed more attractive for settlement by the earlier settlers.

A settler has to think about starving the first year or two, because trees have to be cut down, and stumps pulled up before the land can even be plowed. After that, comes planting and growing, then finally harvesting. Trees, behind which Indians can hide, are a bad thing all around in the eyes of a settler. The flat swampy meadows of the Jersey bank were just exactly what the Dutch knew how to manage. Dam up the creeks and drain the ground, and you will soon have lots of lands ready for the plow, without any confounded trees. By the end of the seventeenth century, the English who had made the mistake of settling in rocky Connecticut finally saw what the Dutch were able to do, and came down to take it away from them.

|

| Greenwich scenery |

That's why there is a Salem, New Jersey, and also a Greenwich, New Jersey. Greenwich ( around here they pronounce it green-witch) had 870 residents at the last census. It is one of the cutest little colonial villages you are likely to encounter. The local historians refer to it as an unreconstructed Williamsburg, drawing prideful attention to the fact that these houses were really built in the colonial period, and are in no way imitation reconstructions. The isolated charm of this place is in large part due to being surrounded by a maze of wandering creeks, so visitors by land travel don't get there in time for lunch unless they take great care to follow a local road map. If you arrive by water, it's no problem; just navigate up the crooked and twisting Cohansey River.

Although pioneer settlement was much earlier, the oldest house still standing in that rather damp area was built in 1730. Things are pretty much the way they were before the American Revolution because the Calvinists who settled here were not prepared for the Jersey mosquito, which obviously is abundant in such a marshy area. With the mosquito comes relapsing (Vivax, malaria, black water (Falciparum) malaria, and Dengue Fever (graphically known locally as break-bone fever). As a matter of fact, encephalitis is also mosquito-borne. When you don't understand the insect carrier situation, survival in such an environment depends on local fables and lore, like going to the mountains for the summer after the planting season, and only returning at harvest time. That sounds to a New Englander newcomer like a superstitious cloak for lazy living, especially since masses of fish come up the river in teeming waves, looking for mosquitoes to eat. So, Greenwich is charming, but it never was thriving.

Working hard to find something to say about the town, it would appear that Paul Revere himself came riding into Greenwich in December 1774, urging the town to join their Boston relatives in the destruction of tea belonging to the British East India Company. Greenwich accordingly had a public tea burning on December 22. Since the more notorious Boston tea party took place on December 16, 1773, and the British Tea Act was passed in May, 1773, it is not exactly accurate to say the rebellion spread like wildfire. One has to suppose that the inflammatory tale told to the local farmers by Paul Revere was likely a little enhanced, since a careful recounting of the events in Boston suggests a number of ways the uproar might have been avoided if Samuel Adams and his friends had been less provocative. Or if Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson had been less flighty. Or for that matter, if Benjamin Franklin had restrained himself when he got hold of Hutchinson's letters at a critical moment when he was in London. In retrospect, the best model for behavior was provided by the Royal Navy; the whole Boston Tea Party was surrounded by armed British naval vessels, who did not lift a finger throughout the demonstration.

Anyway, little Greenwich had its minute of fame with a tea burning. Otherwise, it has had a very quiet existence for three centuries.

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

Delaware's Court of Chancery

|

| Chancery |

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's the county seat so it has a courthouse on the town square, with little roads running off in several directions. The courthouse is surprisingly large and imposing, even more, surprising when you wander through cornfields for miles before you suddenly come upon it. The county seat of most counties has a few stores and amenities, but on one occasion I hunted for a barbershop and couldn't find one in Georgetown. This little town square is just about the last place you would expect to run into Sidney Pottier and all the top executives of Walt Disney. But they were there, all right, because this was where the Delaware Court of Chancery meets; the high and mighty of Hollywood's most exalted firm were having a public squabble.

Only a few states still have a court of Chancery, but little Delaware still has a lot of features resembling the original thirteen colonies in colonial times. The state abolished the whipping post only a few decades ago, but they still have a chancellor. The Chancellor is the state's highest legal officer, and four other judges now need to share his workload, which was almost completely within his sole discretion seventy-five years ago. In fact, the Chancellor usually heard arguments in his own chambers, later writing out his decisions in longhand. The Court of Chancery does not use juries.

Going back to Roman times, the Chancellor was the highest office under the Emperor, and in England, the Lord Chancellor is still the head of the bar in a meaningful way. Sir Francis Bacon was the most distinguished British Chancellor and gave the present shape to a great deal of the present legal system. A court of Chancery is concerned with the legal concept of equity, which is a sense of fairness concerning undeniable problems which do not exactly fit any particular law. The Chancellor is the "Keeper of the King's conscience" concerning obvious wrongs that have no readily obvious remedy. You better be pretty careful who gets appointed to a position like that, with no rules to follow, no supervisor, no jury, dealing with mysterious issues that have no acknowledged solution.

|

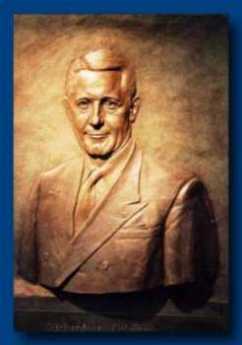

| George Read |

Delaware's Court of Chancery evolved in steps, with several changes of the state Constitution over a span of two hundred years. As you might guess, a few powerful chancellors shaped the evolution of the job. Going way back to 1792, Delaware changed its Supreme Court from the design of its Constitution, and George Read was the new Chief Justice. However, it was all a little embarrassing for William Killen, who had been the Chief Justice, getting a little old. Read refused to have Killen dumped, and in this he was joined by John Dickinson, who had been Killen's law clerk. So Killen was made Chancellor, and a court of Chancery was invented to keep him busy.

Under a new 1831 Constitution, the formation of corporations required individual enabling acts by the Legislature and limited their existence to twenty years. However, the 1897 Constitution relaxed those requirements and permitted entities to incorporate under a general corporation law and allowed them to be perpetual. By this time, other states were distributing equity cases to the county level, but Delaware was too small to justify more than a single state-wide Court. That court was attractive to corporations because it could become specialized in corporate matters, but retained a pleasing number of equity cases among common citizens, thus retaining a folksy point of view. In unique situations or those without a significant history of public debate, it was thought especially desirable to strive for unchallenged acceptance of the court's decision.

But other states thought they could see what Delaware was up to. In 1899 the American Law Review contained the view that states were having a race to the bottom, and Delaware was "a little community of truck farmers and clam-diggers . . . determined to get her little, tiny, sweet, round baby hand into the grab-bag of sweet things before it is too late." However, that may be, corporations stampeded to incorporate in the State of Delaware, and the equity of their affairs was decided by the Chancellor of that state. In one seventeen year period of time, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Chancellor only once.

Chancery's jurisdiction was complementary to that of the courts of common law. It sought to do justice in cases for which there was no adequate remedy at common law.  |

| A. H. Manchester Modern Legal History of England and Wales, 1750-1950 (1980) |

Some legal scholar will have to tell us if it is so, but the direction and moral tone of America's largest industries has apparently been shaped by a small fraternity or perhaps priesthood of tightly related legal families, grimly devoted to their lonely task in rural isolation. The great mover and shaker of the Chancery was Josiah O. Wolcott (1921-1938), the son and father of a three-generation family domination of the court. Most of the other members of the court have very familiar Delaware names, although that is admittedly a common situation in Delaware, especially south of the canal. The peninsula has always been fairly isolated; there are people still alive who can remember when the first highway was built, opening up the region to outsiders. Read the following Chancelleries quotation for a sense of the underlying attitude:

"The majority thus have the power in their hands to impose their will upon the minority in a matter of very vital concern to them. That the source of this power is found in a statute, supplies no reason for clothing it with a superior sanctity, or vesting it with the attributes of tyranny. When the power is sought to be used, therefore, it is competent for anyone who conceives himself aggrieved thereby to invoke the processes of a court of equity for protection against its oppressive exercise. When examined by such a court, if it should appear that the power is used in such a way that it violates any of those fundamental principles which it is the special province of equity to assert and protect, its restraining processes will unhesitatingly issue."

That is a very reassuring viewpoint only when it issues from a person of totally unquestioned integrity, a member of a family that has lived and died in the service of the highest principles of equity and fairness. But to recent graduates of business administration courses in far-off urban centers of greed and striving, it surely sounds quaint and sappy. And many of that sort have found themselves pleading in Georgetown. Just let one of them a bribe, muscle, or sneak into the Chancellor's chair someday, and the country is in peril.

Disorderly Retreat: From Trenton Back to Perth Amboy

|

| George Washington on a Horse |

A week later, they got a bad jolt; Washington declined to play by their winter rules. At the Battle of Trenton, Washington was 44 years old, six feet four inches tall or more, a horseman and athlete of outstanding skill, and as the husband of the richest woman in Virginia, accustomed to housing, feeding, transporting and getting cooperation from two hundred slaves. All of those qualities may have been of some use in the battle. But after the Battle of Trenton, Washington also emerged as a remarkably bold and creative General. In the Battle of Trenton ca-----------------999999 seen the elements of audacity, timing and courage that were notable in Stonewall Jackson, George Patton -- Virginians, both -- the Normandy Invasion, and the Inchon Landing. He forged, if he did not create, the American military tradition of inspired risk-taking. And he did it with a collection of starving amateurs, up against the best Army in the world at the time. Probably without realizing it, his coming victory at Trenton also gave Benjamin Franklin in Paris a major enticement for the French King to support the American cause. Washington produced a significant achievement, but just to make sure, Franklin exaggerated it just as much as he could.

On December 21, Washington thought Howe was immediately going to sweep on through Trenton to Philadelphia. In a day or two, he saw that wasn't the plan, organized the famous re-crossing of Delaware in bad weather, and caught and captured a thousand Hessians with a three-pronged attack which cut off their retreat and made resistance useless. The main military feature of this attack was not Christmas drunkenness among the Hessians, but the fact that General Knox had somehow transported eighteen cannon to the occasion. Nowadays, the event is marked by a reenactment on Christmas Morning, although it took place on December 26, 1776. The timing did not have to do with religious observance, it had to do with hangovers. To the great disappointment of his troops, he made them abandon the great stores of booze in Trenton because a second detachment of Hessians was in nearby Bordentown, and meanwhile, he retreated back to the Pennsylvania side of the river. As might be imagined, Howe's Cornwallis promptly came charging down from New Brunswick to exact bitter vengeance. Instead of trying to rescue their comrades in Princeton, the Bordentown Hessians took off for New Brunswick. Defiantly, Washington taunted his enemies by again recrossing Delaware to the New Jersey side, put up fortifications, just waited for them to make something of it.

Well, that's the way it was meant to seem. On the night of January 2, the two armies were facing each other with about five thousand men on both sides, but with the British much better trained and equipped. The Americans had the advantage of not being exhausted by a fifty mile forced march, except for about a thousand who had been deployed forward to skirmish and delay the British advance with sniping from the bushes. The Americans made a great deal of noise and lit many bonfires behind their fortifications. But when they advanced the next morning, the British found out where the Americans really were -- by hearing distant cannon fire coming from Princeton, ten miles back toward the north.

Washington had slipped five thousand men wide around the enemy flank during the night and had taken a parallel country road to Princeton where he defeated a rear guard of British at the Battle of Princeton. An infuriated Cornwallis wheeled his army around in pursuit, and the race was on for the supplies left undefended in New Brunswick. Washington might have been able to get there first, except his men were too exhausted, and he was afraid to risk his long-run strategy, which was to avoid head-on collisions with the main British Army.

So Washington went into winter quarters in Morristown still further to the north, and thousands of British soldiers were thus bottled up in winter quarters in Perth Amboy and New Brunswick, where scurvy, lack of firewood and smallpox gave them a few months to consider their miscalculations. But the most important action of all was getting the news to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, to tell the French king of the victory. Franklin even dressed it up a little.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey in the American Revolution: Barbara J. Mitnick: ISBN-13: 978-0813540955 | Amazon |

Potts

Rebecca Potts used to say there were three towns in Pennsylvania named after her family -- Pottstown, Pottsville,

|

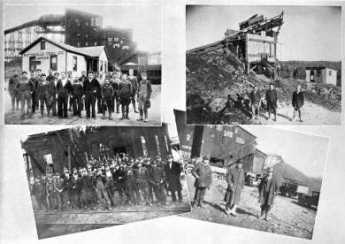

| Pottsville biennial |

and Chambersburg. Becky never designed to explain whether Chambersburg was just a joke or whether her very extensive family really had connections in Chambersburg. It's possible either way; there were certainly Potts inValley Forge where Washington's Headquarters, which everyone visits, had been home to Isaac Potts, the third generation of Dutchmen named Potts to live there. Isaac ran a grist mill, the others mostly were ironmasters. The family seat in Pottstown was named Pottsgrove, still open for visitors. Holland Dutch they may have been, but Pottsgrove architecture is definitely of the Welsh style.

|

| Pottsville Coal |

Pottsville, much further up in the anthracite region, became notable through the novels of John O'Hara, a native son. For a whole generation, just about everybody in Pottsville was uneasy that O'Hara would confirm just who certain characters in his moderately raunchy novels represented in real life. Pottsville's main business for a century was extracting coal for the Girard Estate, which had its coal-mining headquarters in the town, based on Stephen Girard's shrewd purchase of nearly all of Schuylkill County.

The broad sweeping view from the interstate highway going north from Valley Forge makes it easy to see how Pottstown was created by the upheaval of a mountain ridge, which split open to let the Schuylkill River wind through. Pottstown is a water gap. The huge cooling towers of The Limerick nuclear power plant dominate one side of the river cliff and can be seen for miles. The cliff on the other side of the river, behind which hides the town of Pottstown, used to shelter the Wright aircraft factory, much of which was underground. That gave it a railroad (The Reading RR) and ready access to the river, plus privacy from the land side. Down to the right a mile is the Pottstown Hospital, on the edge of town, quite near the campus of the famous Hill School, fierce competitors of the Lawrenceville School in sports. Just about everything in this area is on top of some kind of hill.

Just back of the hospital, seemingly on the grounds of it, rises a peculiar steel tower, which the local workmen report is a sending station for cellular telephones. However, one of the doctors of the hospital relates a somewhat different history. He says he was once called on a medical emergency, told to ring the elevator at the little house beside the steel antenna, and travel down, down, into secret depths. He found himself in the headquarters of the Northeastern Air Defense Command, which was certainly hidden in an ideal place if the story has any truth to it. Unfortunately, that story-teller was a famous cocktail-party raconteur whose wild tales were never to be taken completely seriously. For many years, the hospital on a cliff was surrounded by corn fields, and it is certainly true you could look out the windows at a sea of corn, never suspecting you were very close to a railroad and a river, quite possibly right over an underground aircraft factory. Someday it may be possible to find out the truth of these tales of the Dutch country.

During the American Revolution, the British blockaded the coast and landed troops on the main coastal highways. The Americans responded in a quite natural way by building an inland north-south forest trail, sort of on the order of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Pottstown was one natural stop on this trail, which tended to intersect with many roads coming up along the banks of the coastal rivers. In one very famous episode, wagon loads of Philadelphia Quakers were arrested and taken up the Schuylkill to Pottstown, then south to internment at Winchester, Virginia. They weren't exactly Tories, but they certainly were not sympathetic to revolutions. One of the most famous of these semi-prisoners was Israel Pemberton, one of the leaders of the Quaker colony. He later reported he was treated well, but onlookers in Pottstown described him as being thoroughly abused.

Pottstown had a century of prosperity during the industrial age, then declined and decayed. In recent years. The interstate highway has brought a migration of exurbanites whose taste in architecture tends toward McMansions. Let's hope they can acquire a dose of local history, starting a new historical revival of a town with great potential, considerable past glory, and a wonderful natural setting.

Harriton House

|

| Harriton House |

Three hundred years ago, in 1704, Roland Ellis acquired 700 acres of the Welsh Barony in what is commonly called Philadelphia Main Line and built a palatial house on it. He called his homestead Bryn Mawr, or great hill, after his ancestral home in Wales of the same name, thereby explaining why Bryn Mawr College and Bryn Mawr town have the name but are not notably situated on hills. The town of Bryn Mawr was once called Humphryville. But Bryn Mawr sounded nicer, even though there are plenty of Humphries still around to defend the older designation.

About fifty thousand acres were set aside by William Penn as the Welsh Barony, and there was the willingness to allow it to be self-governing, although that didn't much happens because the inhabitants saw no point in being self-governing. Nevertheless, the term isn't just an ethnic allusion, but has some historic meaning.

In any event, Ellis proved to be an unsuccessful manager of his estate, which rather soon passed into the hands of the Harrison family, who lived on it for about two hundred years until real estate development, and the taxes related thereunto, forced the creation of a complicated arrangement, with the township of Lower Merion owning the property and a non-profit group called the Harriton Association managing it. They have luckily obtained the services of a famous curator, Bruce Gill, who does research, writes papers, and organizes programs for visitors. The neighbors in the area, all living on land that formerly belonged to the Harrisons, are said to constitute the richest neighborhood in America. By building the original farmhouse rather far from the main road (Old Gulph) and remaining surrounded by neighbors who want to have privacy, Harriton House has fewer visitors than it deserves because it is so devilish hard to find.

There was a little local skirmishing during the Revolutionary War, but the main historical significance of the House was that Charles Thomson married a Harrison and lived there all throughout the period of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation (1774-1789) as the Secretary of the Continental Congress. His little writing desk is, therefore, the most notable piece of furniture at Harriton House since every piece of official paper involved in the whole Revolutionary episode passed through it or over it. Modern organizations would do well to notice that Thomson was not given a vote and was expected to be totally unbiased about Congressional affairs. Even in those days, there must have been cautionary experience with secretaries who tinkered with the minutes for their own preferences. It certainly was entirely fitting that this last steward of the Articles of Confederation was designated to carry the news to George Washington at Mount Vernon, that he had been elected President of the new form of government. No doubt, Washington was pleased but unsurprised to learn of it.

While Harriton House is imposing on the exterior, and was the likely prototype of many characteristic Main Line stone mansions, the inside of the house is quite primitive. In those days it was cheap to build a big house but expensive to heat it. In 1704 surrounded by a continent of a forest, firewood may not have seemed a problem, but it quickly posed a transportation problem, and later houses tended to shrink in size. In any event, the interior of the house seems strangely bleak and bare, quite in keeping with the early Quaker principle of building a structure "without paint, or other adornments". Bruce Gill spent quite a lot of time and effort to determine that the random-width flooring had never received any shellac, varnish or wax. Those are beautiful floors, but the "finish" is just three hundred years of oxidized dirt.

The original Bryn Mawr, now called Harriton House, is well worth a visit. If you can find it; GPS is the modern solution.

Gardens for Posterity

|

| J. B. Garden |

We must be indebted to "Several Anonymous Philadelphians" who wrote a book published in 1956 called Philadelphia Scrapple, now out of print but subtitled "Whimsical Bits Anent Eccentricities and the City's Oddities." The Athenaeum librarian has carefully penciled in the names of Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Mrs. Henry Cadwalader as the probable authors of this work, and it's likely that is the fact of it.

Chapter XIV of "Philadelphia Scrapple" discusses a class of notable public gardens not designed to be show gardens, but originally the hobbies or passions of the original owner for private enjoyment, and later were opened to the public. These abound in Philadelphia, sometimes somewhat decayed, often truncated as the land was sold off, but constantly increasing in interest as the boxwood, trees, and shrubs continue to grow in size and rarity. The Anonymous Philadelphians have classed these lovely and somewhat unknown places as "Gardens for Posterity". Quite often, the estate houses to which they belong are better known than their gardens, and the original owners just regarded their gardens as a normal part of the house.

While there are dozens of such places, the more notable ones are Grumblethorpe in Germantown, The Grange in Delaware County, Andalusia along the Delaware, and two famous gardens in decrepit neighborhoods along the lower Schuylkill, John Bartram's Gardens and William Hamilton's ("Woodlands"). There is a record that the Continental Congress once adjourned to visit Bartram's garden, and Hamilton's garden is mentioned by several famous Revolutionary figures since it was on what was then the main route from Philadelphia to the Southern Colonies. John Wister's 1744 garden at Grumblethorpe was 188 by 450 feet in size; some of the boxwood have had a long time to grow.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

To these should be added the hospital gardens at the Pennsylvania Hospital, at Friends Hospital along Roosevelt Boulevard, and the garden of Chester-Crozier Hospital, all of which are especially spectacular in early May when the Azaleas are in bloom. Just about every surviving mansion of colonial rich folks had such a garden at one time.

And tucked away behind many current mansions are lovely gardens that are considered to be just as private as their living rooms. While they are proudly displayed to friends, strangers knocking at the garden door would be considered the height of rudeness. It will take another generation or so for them to be thrown open to the public. By that time, who knows what state of repair they will be in.

For a unified access point for 30 gardens in the Philadelphia area, try www.greaterphiladelphiagardens.org

Georgetown Returns Day

|

| Georgetown |

Early in November, two days after each election, Georgetown Delaware puts on a festival called Returns Day. About two hundred years ago, there was a law that all ballots had to be cast in person at the courthouse in the county seat (Lewes, at that time), and it took two days to count the votes. Everyone, candidates included, would hang around at the courthouse to learn who had won. After a few elections, except in wartime when the ceremony was temporarily skipped, the popular tradition has continued even though of course the election results are known much earlier. Although the function of revealing election results has yielded to the news media, the ceremony has assumed importance for its own sake. Unless it rains pretty hard, the parade lasts three hours, with ten or twelve marching bands, and local amateurs struggling with bagpipes. The candidates, winner, and loser, ride gamely around the square in horse-drawn carriages. You can imagine what would happen to the political future of any candidate who declined to participate in what is now a mandatory public entertainment.

|

| U.S. Senator from Delaware |

Two features of this festival are especially notable. There is a hatchet-throwing contest, trying to get the flying hatchet to catch one corner in a post. It's not an easy thing to do. And then there is hatchet-burying, which is said to date back to the Nanticoke Indians. The traditional hatchet is brought from Lewes, as is the sand. This is all said to be the origin of the folk-saying about burying the hatchet, and it's really very heart-warming to believe the election is only an election, and the competition is over. It's probably not entirely true, of course, but it symbolizes what the public wants to believe is true. And what the public is telling politicians -- had soon better become true, again.

Sullivan's March

|

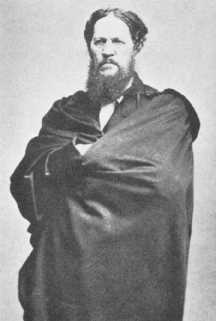

| Sullivan |

George Washington had plenty of other problems to contend with in 1778, but an Indian uprising led by Loyalists was too much. He singled out General John Sullivan, a celebrated Indian fighter from New Hampshire, gave him four thousand troops, and told him to eliminate this Indian threat to the Continental Army's rear, remove the safe haven for Loyalists, and assist the new Indian allies which LaFayette had befriended in the Albany area before the battle of Saratoga.

From long experience, Sullivan knew what to do, and did it without remorse. Ignoring skirmishes and ambushed sentries, he marched his troops from the scene of the massacre straight into the heart of Iroquois homeland, destroying every source of food or Indian settlement he could find. He was not interested in winning battles, he was determined to starve the Indians into extinction, once and for all. After these two slaughters, a white one in the Wyoming Valley (the Connecticut squatters in Wilkes-Barre), and now a red one in upstate New York, the entire frontier north of Pennsylvania has left a scene of devastation. Not much was heard of Indian fighting on this frontier for the rest of the Revolutionary War. Indeed, only the novels of James Fennimore Cooper make much subsequent mention of the Iroquois in American history.

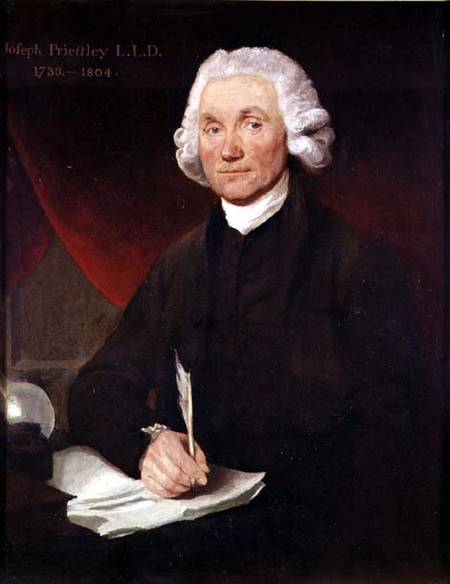

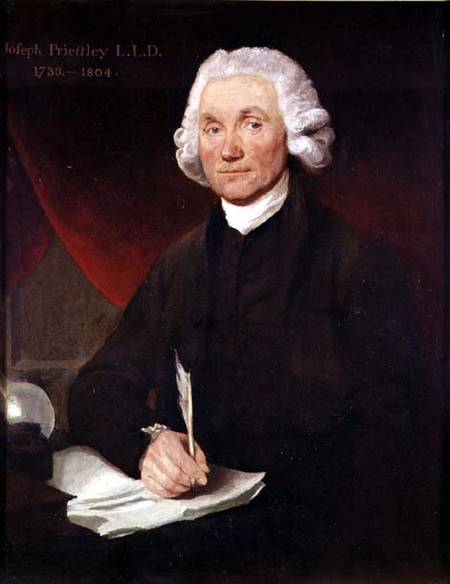

Joseph Priestley, Shaker and Mover

|

| Priestley |

Joseph Priestley, sometimes also spelled Priestly, is surely one of the more undeservedly neglected men of history. He has been called, with justice, the Father of the Science of Chemistry. He might also be called with equal justice, the father of the First Unitarian Church . The First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, at 21st and Walnut, is the first and oldest Unitarian church and was indeed started at the urging of Priestley, whose principal residence was in Northumberland PA, at the confluence of the West and North Branches of the Susquehanna. Priestly wrote a scholarly work on the teachings of Jesus, which so captivated Thomas Jefferson that Jefferson wrote him the outline of another book that needed writing. Apparently, Priestley didn't have time, so in 1803 Jefferson wrote it himself, in the four languages he was fluent in, English, French, Latin, and Greek. Although those were simpler times, there have been few if any others who have told a President of the United States that he was just too busy to respond to a presidential request, particularly when the President could then find he had time to do it himself.

Priestley's theological teachings were based on scientific reasoning. They were highly controversial views, to say the least. He rejected the concept of a Trinity (he was a Calvinist minister, mind you), the divinity of Christ, and the immortality of the soul. Essentially, he rejected the concept of an immortal soul on the reasoning that perceptions and thought were functions of material structures in the human brain (Edmund O. Wilson's idea of Consilience is largely similar), and therefore will not outlive the cerebral tissue which produced them. In 1791, mobs burned his house in Birmingham, England, his patronage was revoked, and he hastily emigrated to Philadelphia. It isn't hard to see why these ideas were particularly unpopular with the Anglican church, which is probably the main reason England made him into a non-person, and his scientific ideas were denigrated as the product of other people.

That's too bad because he really was a scientist of immense importance. As a young man, he encountered Benjamin Franklin in England and was certainly a man after Franklin's heart. He noticed funny things about gases that rose from swamps and over mercury salts, and Franklin encouraged him to systematize and analyze his observations into theory. Although he called it anti-phlogiston, he had discovered oxygen. And then hydrogen, and nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide, and hydrochloric acid. Priestley really was the first organized and coherent scientific chemist, the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, Lavoisier, and Priestley became scientific friends, and enthusiastically exchanged ideas and observations, eventually leading to Lavoisier's fundamental principle: Matter is neither created nor destroyed, it only changes its form. In the end, it made no difference; Priestly had offended some pretty large religions, and nothing he did in chemistry was going to get much attention. Perceiving the value of the land at the confluence of rivers, he made his home for the last ten years of his life in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, now three hours drive Northwest, somehow managing to maintain an active scientific, political and theological influence worldwide. Visiting this rather sumptuous estate in a little river town is well worth a tourist visit. He died in 1804, just after his friend and kindred-religionist Thomas Jefferson became President of the United States.

Priestley's life can be summarized in one of his own most quoted remarks. "In completing one discovery we never fail to get an imperfect knowledge of others of which we could have no idea before so that we cannot solve one doubt without creating several new ones."

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

Kenneth Gordon, MD, Hero of Valley Forge

|

| Valley Forge |

There's no statue of Ken Gordon at Valley Forge National Park, although it would be appropriate. No building is named after him; it's probable he isn't even eligible to be buried there. But there would be no park to visit at Valley Forge without his strenuous exertions.

One day, Ken's seventh-grade daughter came home from school with the news that the father of one of her classmates said that Valley Forge Park was going to be turned into a high-rise development. That's known as hearsay, and lots of things you hear in seventh grade are best ignored. But this happened to be substantially true. At that time, the Park was owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and Governor Shapp was finding the upkeep on the Park was an expense he needed to reduce. The historic area had two components, the headquarters area, and the encampment area. One part would become high-rise development and the other would become a Veteran's Administration cemetery. Although any form of rezoning has the familiar sound of politics to it, Dr. Gordon (a child psychiatrist) had the impression that Sharp was mostly interested in reducing state expenses, and had no particular objection to some better use of the historic area. At any rate, when Gordon went to see him, he said that he would agree to a historic park if Gordon could raise the money somehow. The Federal Government seemed a likely place to start.

Well, the sympathetic civil servants at the National Park Service told him how it was going to be. You get the consent of the local Congressman (Dick Schulze) and it will happen. If you don't get his consent, it won't happen. It seemed a simple thing to visit that Congressman, persuade him of the value of the idea, and it would be all done; who could refuse? After the manner of politicians, Schulze never did refuse, but somehow never got around to agreeing, either. It takes a little time to learn the political game, but after a reasonable time, the National Park employees told Gordon he was licked. Too bad, give up.

He didn't give up, he went to see his Senators, at that time Scott and Clark. They instantly thought it was a splendid idea, and instead of going pleasantly limp, they sent Citizen Gordon over to see Senator Johnson of Louisiana, the chairman of a relevant committee. Johnson also thought it was a great idea, and called out, "Get me a bill writer!" A bill writer is usually a government lawyer, tasked with listening to some citizen's idea and translating it into that strange language of laws -- section 8(34), sub-chapter X is hereby changed to, et cetera. Bill writers have to be pretty good at it, or otherwise, they will misunderstand the intent of the original idea, modified by the personal spin of the committee chairman, the comments of the authorizing committee, and later bargains struck in the House-Senate conference committee. Having negotiated all those hurdles, a bill has to be written in such a prescribed manner that it won't be found to have multiple loopholes when it later reaches the courts in a dispute. A good deal of the time of our courts is taken up with making sense of some careless wording by bill writers. That's what is known as the "Intent of Congress", an ingredient that may or may not survive the whole process.

|

| Dick Schulze |

Ken Gordon had to go through this process, including testimony at hearings, for three separate congressional committees. To get everybody's attention, he organized several hundred supporters to write letters and get petitions signed by several thousand voters. These supporters, in turn, influenced the media and started a lot of what is known as buzz. All of this is an awful lot of work, but there is one thing about this case that can make us all proud. Not once did a politician suggest a campaign contribution was essential in this matter.

In time, ownership of the Park did in fact migrate from the Commonwealth to the U.S. Department of the Interior, hence to the National Parks Service. Everyone agrees it has been well managed, and increasing droves of visitors come here every year. It is now clearly a national treasure. Unfortunately, the encampment area got away and has been commercially developed, although not nearly as high-rise as originally contemplated. Along the way, many discouraging words were spoken about the futility of fighting against such odds. The outcome, however, is the embodiment of two slogans, the first by Ronald Reagan. "It's amazing what can be accomplished, if you don't care who gets the credit for it." The other slogan is older, and Quaker. All you need, to accomplish anything, is leadership. And leadership -- is one person.

One day Ken Gordon, the very busy doctor, was asked how much of his time was taken by this effort. His answer was, ten hours a week, every week for five years.

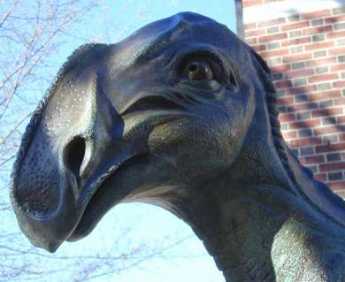

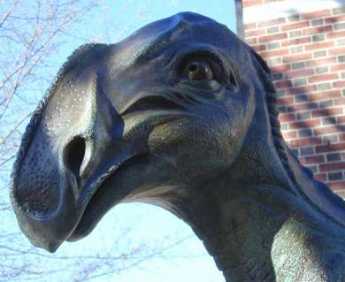

The Origins of Haddonfield

|

| Haddonfield's Dragon |

Haddonfield, New Jersey is named after Elizabeth Haddon, a teenaged Quaker girl who came alone to the proprietorship of West Jersey in 1701 to look after some land which her father had bought from William Penn. Geographically, the land was on what later came to be called the Cooper River, and it must have been a scary place among the woods and Indians for a single girl to set up housekeeping. It was related in the "Tales of a Wayside Inn" that Elizabeth proposed to another young Quaker named John Estaugh. Because no children resulted, she sent to her sister in Ireland to send one of her kids, a girl who proved unsatisfactory. So the kid was sent back, and Ebenezer Hopkins was sent in her place. Thus we have Hopkins pond, and lots of Hopkins in the neighborhood ever since. Eventually, the first dinosaur skeleton was discovered in the blue clay around Hopkins Pond, and now can be seen in the American Museum of Natural History, so you know for sure that Haddonfield is an old place. Eventually, the Kings Highway was built from Philadelphia to New York (actually Salem to Burlington at first) and it crosses the Cooper Creek near the old firehouse in Haddonfield, which claims to house the oldest volunteer fire company in America, but not without some argument about what was first, what is continuous, and therefore what is oldest. Haddonfield is, in short, where the Kings Highway crosses the Cooper, about seven miles east of City Hall in Philadelphia. The presence of the Delaware River in between makes a powerful difference since at exactly the same distance to the west of City Hall, is the crowded shopping and transportation hub at 69th and Market Street. Fifty years ago, Haddonfield was a little country town surrounded by pastures, and seventy years ago the streets were mostly unpaved. The isolation of Haddonfield was created by the river and was ended by the building of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in 1926. If you go way back to the Revolutionary War, the river created a military barrier, and many famous patriots like Marquis de Lafayette, Dolley Madison, Anthony Wayne and others met in comparative safety from the British in the Indian King Tavern. In a famous escapade, "Mad" Anthony Wayne drove some cattle from South Jersey around Haddonfield to the falls (rapids) at Trenton, and then over the back roads to Washington's encampment at Valley Forge. In retaliation, the British under Col John Simcoe rode into nearby Salem County and massacred the farmers at Hancock's Bridge who had provided the cattle. At another time, the Hessians were dispatched through Haddonfield to come upon the Delaware River fortifications at Red Bluff from the rear. Unfortunately for them, they encamped in Haddonfield overnight, and a runner took off through the woods to warn the rebels at Red Bank to turn their cannons around to ambush the attackers from the rear, who were therefore repulsed with great losses. These stories are told with great relish, but my mother in law found out some background truths. Seeking to join the Daughters of the Revolution in Haddonfield, she was privately told that the really preferable ladies' the club was the Colonial Dames. Quaker Haddonfield, you see, had been mostly Tory.

|

||

| Alfred Driscoll |

A local boy named Alfred Driscoll became Governor of New Jersey, but before he did that he was mayor of Haddonfield. He had gone to Princeton and wanted to know why Haddonfield couldn't look like Princeton. All it seemed to take was a few zoning ordinances, and today it might fairly be claimed that Haddonfield is at least as charming and beautiful as Princeton, maybe nicer. At the very least, it has less auto traffic. Al Driscoll went on to be CEO of a Fortune 500 pharmaceutical corporation, and everyone agrees he was the world's nicest guy. The other necessary component of beautiful colonial Haddonfield was a fierce old lady who was married to a lawyer. Any infraction of Al's zoning ordinances was met with an instant attack, legal, verbal, and physical. A street-side hot dog vendor set up his cart on Kings Highway at one time, and the lady came out and kicked it over. If you didn't think she meant business, there was always her lawyer husband to explain things to you. She probably carried things a little too far, and one resident was driven to the point of painting his whole house a brilliant lavender, just to demonstrate the concept of freedom. Now that she and her husband are gone, the town continues to be authentic and pretty, probably because dozens of other citizens stand quietly ready to employ some of her techniques if the need arises.

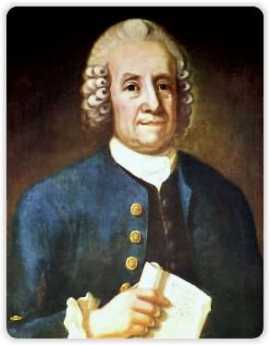

The Swedenborgian Church

|

| Emanuel Swedenborg |

Among the many churches centered in Philadelphia, the Swedenborgian is probably the least typical and most difficult to understand. The church does not actively seek out a new membership, but it welcomes everyone, in the spirit of Emanuel Swedenborg's observation that "All people who live good lives, no matter what their religion, have a place in Heaven." Without attempting to define the teachings of Swedenborg (1699-1772), who was quite able to speak for himself, it can be approximated that Heaven plays a central role in this belief system, and predestination does not. Although the ceremonial features of this religion are very similar to the Episcopal Church, its main emphasis is on good works as a way of attaining the reward of Heaven. In some ways, that is an unexpected position for a noted scientist like Swedenborg to take, since generally scientists lean toward Calvinism, with the mechanistic view that if God is all-powerful, then human free will must be impossible.

|

| cross |

There are at least four divisions of the Swedenborgian religion, but the Bryn Athyn branch is most notable in the Philadelphia region. A very wealthy adherent of Swedenborg named John Pitcairn bought a large tract at Bryn Athyn and gathered the local church to live around a perfectly magnificent cathedral and church school. It is hard to think of any church in the Philadelphia region which approaches the magnificence of the Bryn Athyn cathedral. It has a special character that it was conceived and built during the crafts movement of the early twentieth century, with imported European workmen deliberately organized like medieval craft guilds. The central features of this workmanship reflect and then project the belief in personal individuality within the whole religion. No two windows, or doorknobs, or carvings are the same in the cathedral, reflecting the wish for each workman to devise his own unique creation and show the way of personal responsibility to the faithful. This cathedral is one of the things in the Philadelphia region most worth visiting, but to appreciate its quality you have to know what you are looking at.

Everybody in this church is unexpectedly hard to characterize. The Pitcairn Foundation was such a successful investor that it formed a mutual fund for others to share in its good fortune. Its central philosophy is to invest only in corporations which have been dominated by a single family, preferably the founding family, for at least fifteen years. There are about six hundred eligible corporations, and recent management scandals in the newspapers illustrate the Pitcairn's exactly knew the dangers of handing your assets over to a hired manager. This family-centered investing approach consistently yields better than the S & P 500, which in turn beats ninety percent of investment managers. You sort of get the idea you know where this family is coming from when you meet a courtly, meek, retiring but friendly person, who can say, "My mother is the only person I ever met who looked perfectly at home seated under a sixty-foot ceiling."

|

| Helen Keller |

Two other famous Swedenborgians illustrate the unusual individualism of this religion. Helen Keller, the deaf-blind girl who overcame her handicap by going to Radcliffe and becoming a successful author and lecturer, for one. The other would be Johnny Appleseed (1774-1845), whose real name was John Chapman. Grammar school legends would have this bearded, barefoot vegetarian adopting a life of poverty like St. Francis, but in fact, he was an extremely shrewd businessman who died rich. He developed the business plan that American settlers would be going West into what was then the Northwest Territory, and having a tough time getting enough to eat the first year or two. So, he anticipated the paths of frontier settlement, and went ahead among the Indian tribes, planting apple trees. When the settlers arrived in the region, he sold them young apple trees and showed them what to do with them. Apples grown from seed are not the tasty morsels we know today but tend to be rather shriveled and bitter. So Johnny showed them how you make cider, and if you let it sit around a while, hard cider. The settlers would use the pulpy squeezing for compost, and he would be back to collect the seeds from them so he could continue his business plan in the next county. In short, he showed them how to drink the apples. He also let the Indians pick the apples, so they liked him and spared him the common troubles of the frontier.

If you are going to boil apples, you need a pot, and Johnny often carried his like a hat. He wasn't a nut, at all, he was a showman. In his backpack, he was also carrying a Bible. And in his head, he carried a motto, "All religion has to do with life, and the life of religion is to do good."

La Fayette, We Are Here

|

| Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette |

It will be recalled that La Fayette was 19 years old at Valley Forge, spoke no English, had no previous military experience. He nevertheless demanded, and got, a commission as Major General on the prudent condition that he have no troops under his command, at least for a while. Washington had been strongly reminded by various people that this young Frenchman was one of the richest men in France, a personal friend of the Queen, and thus critical to the project of enlisting French assistance in the war. Under the circumstances, it was shrewd to send him on the project of enlisting Indian allies among the Iroquois, since many tribes, particularly the Oneida, spoke French and held their former allies in the French and Indian War in great esteem. The chief of the Oneida Wolf clan (Honyere Tiwahenekarogwen) was visiting General Philip Schuyler in Albany at about the time LaFayette showed up on his mission to get some help for Valley Forge. General Horatio Gates was busy at the time rallying a colonist army to defend against the British under Burgoyne, coming down from Quebec, eventually to collide at the Battle of Saratoga.

Earlier in the war, Honyere's Oneida tribe had tangled with their fellow Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brandt (the Dartmouth graduate who was both biblical scholar and commander of several frontier massacres); the Oneida had many new scores to settle with the English-speaking Iroquois tribes. Honyere made the not unreasonable request that before his warriors went off to war, his new American allies would please build a fortification to protect his women and children from Brandt's Mohawks. LaFayette readily put up the money for this project, quickly becoming the Great French Father of the Oneidas. After some scouting and patrolling for Gates, Honyere and about fifty of his braves followed LaFayette to Valley Forge, where they soon made a nuisance of themselves to the Great White Father George Washington. Finally, word of the official French alliance with the colonists reached London, Howe was replaced by Clinton, and the British began to withdraw from their isolated position at Philadelphia.

It was thus that the jubilant rebels at Valley Forge learned that the fortunes of war had turned in their favor, and the French alliance was the source of it. With the British making preparation to abandon Philadelphia, it seemed a safe thing for Washington to give LaFayette command of two thousand troops, including the fifty Oneida Indians, and post them to Barren Hill (now LaFayette Hill), along Ridge Pike near Plymouth Meeting. Washington gave the strictest orders that they were to take no chances with anything, and particularly were to remain mobile, moving camp every day. This was not exactly what the richest man in France was anticipating, and wouldn't make a very saucy story to tell Marie Antoinette about. So, he promptly set about fortifying Barren Hill. Local Tory spies quickly spread this news to General Clinton, who promptly led eight thousand redcoats up the Ridge Pike to capture the bloody Frog. Clinton's plan was good; a detachment went around LaFayette in the woods and came back down Ridge Pike from the other direction, driving the Americans down the Pike into the open arms of the main body of British troops, coming up Ridge Pike. From this point onward, two entirely different stories have been told.

The more widely-held account has LaFayette climbing the steeple of the local church and noticing that there was an escape path, leading down the hill to the Schuylkill River at Matson's Ford. The Indian scouts were sent forward to hold off the British while the troops made their escape. Clinton sent a cavalry charge of Dragoons forward, yelling and waving their sabers, generally making a terrifying spectacle. The Indian scouts, as was their custom, were lying in the brush shoulder to shoulder, and at command by Honyere rose from the ground to let out a resounding chorus of war whoops. The Indians had never seen a cavalry charge, the Dragoons had never heard a war whoop, so both sides fled the battlefield without doing much damage. Meanwhile, LaFayette and his troops escaped to safety on the far side of the Schuylkill.

Other accounts of this episode relate that when Washington heard of it he remarked sourly that either they were pretty lucky, or else the enemy was pretty sluggish. In any event, a few soldiers were killed on both sides, the Americans crossing the River were described as "kegs bobbing on the pond", and it does seem the British army mostly just watched them do it. In the confusion, of course, everyone involved was fearful of being surrounded by unseen troops, and the British may well have worried the whole thing was a trap.

The saddest postscript to the Battle of Barren Hill is the fate of the Indians. After the war was over in 1783, the colonists busied themselves with taking over Indian land. Honyere pitifully petitioned the New York legislature for some consideration of his tribe's wartime service. They ignored him.

Lambertville and Lewis Island

|

| Atlantic Shore Railroad |

Recall that open Atlantic shoreline once stretched from Perth Amboy to New Castle, Delaware. Glaciers pulverized the nearby mountains and dumped a huge moraine of sand into the ocean, creating southern New Jersey as an offshore island in geological times. The bay silted up and eventually attached that island to New Jersey. The silting-up probably would have continued for another sixty miles, making Philadelphia a land-locked inland city, except that the true

|

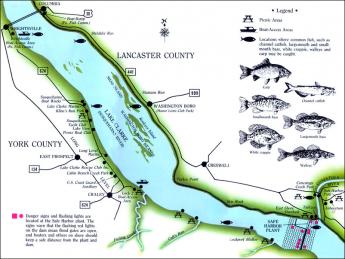

| Delaware River |

Delaware River came tumbling down from the mountains to Trenton, turning sharply right and then maintaining an open shallow channel to the sea. From Lambertville to Trenton, the river drops over a series of small falls or rapids, easily visible except when heavy rains "drown" them.

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

So, geography accounts for the scenery and early history of the upper end of Delaware Bay. It's still a beautiful hilly countryside with small antique villages, sparsely populated in spite of two nearby cities. Water power at the Fall Line, and then anthracite from the upstate mountains once encouraged early industry in an area that was rather poor farm country. But the Pennsylvania Railroad then rearranged commerce so that a blossoming New Jersey industrial area withered into quaintness. The early railroads mostly all ran East-West along the rivers, since investors in Atlantic port cities obtained both finance and protection from their state legislatures; railroads had almost reached the Mississippi before any were able to establish North-South connecting spurs. A seaboard trunk line was almost impossible to imagine. Finally, a consortium organized by

J.P. Morgan bullied through the main trunk line running through the bituminous coal areas of Pennsylvania and on to the West, with the major port cities connected by the great Northeast Corridor of the Pennsy. This corridor would run on the Pennsylvania side of Delaware. Industry on the bypassed New Jersey side would just wither and decline, and eventually so would the anthracite cities. Since the original colonies and states all ran from the ocean to the interior, each had a vital political interest in resisting this outcome. Only a strong and brutal corporation could bring it off.

When George Washington was circling around Trenton to attack it on Christmas, a narrow spot up-river with a dozen houses on either side was called Coryell's Crossing or Ferry. That's now Coryell Street in Lambertville, linked to the other side of the river at New Hope, after first crossing a narrow wooden bridge to Lewis Island, the center of shad fishing, or at least shad fishing culture.

The Lewis family still has a house on Lewis Island, and they know a lot about shad fishing, entertaining hundreds of visitors to the shad festival in the last week of April. The river is cleaning up its pollution, the shad are coming back, but they, unfortunately, took a vacation in 2006. At the promised hour, a boatload of men with large deltoids attached one end of a dragnet to the shore, rowed to the middle of the river, floated downstream and towed the other end of the net back to the shore. The original anchor end of the net was then lifted and carried downstream to make a loop around the tip of Lewis Island, and then both ends were pulled in to capture the fish. There were fifty or so fish in the net, but only two shad of adequate size; since it was Sunday, the fish were all thrown back.

But it was a nice day, and fun, and the nice Lewis lady who explained things knew a lot. Remember, the center of the river is a border separating two states. You would have to have a fishing license in both states to cross the center of the river with your net; game wardens can come upon you quickly with a power boat. But the nature of fishing with a dragnet from the shore anyway makes it more practical to stop in the middle, where shotguns from the other side are unlikely to reach you. An even more persuasive force for law and order is provided by the fish. Fish like to feed when the sky is overcast, so there is a tendency on a North-South river for the fish to be on the Pennsylvania (West) side of the river in the morning, and the New Jersey (East) side in the evening. During the 19th Century when shad were abundant, work schedules at the local mills and factories were arranged to give the New Jersey workers time off to fish in the afternoon, while Pennsylvania employers delayed the starting time at their factories until morning fishing was over.

Somehow, underneath this tradition one senses a local Quaker somewhere with a scheme to maintain the peace without using force. Right now, there aren't enough fish to justify either stratagem or force, but one can hope.

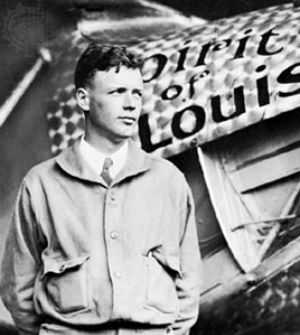

Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping Trial

|

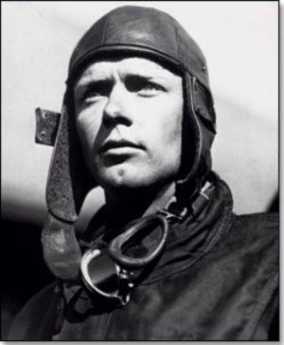

| Lindberg |

In 1935, Bruno Hauptmann was executed for kidnapping the baby of America's "Lone Eagle". Swarms of competing police and reporters made chaos of the scene, and Charles Lindbergh made it all worse by dealing directly with the crime underworld. Even today, some question the guilt of Hauptmann, and even whether the baby is really dead.

We are indebted to George Hawke, who went to prep school near the scene of the crime, for becoming an expert, perhaps the preeminent expert, on the Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping Trial. Charles Lindbergh, the son of a midwest pro-German congressman, flew an airplane alone across the Atlantic in 1927. He became instantly famous, wrote a best-seller called Alone, became Colonel Lindbergh, married Anne Morrow the daughter of Senator Morrow of New Jersey. That's how in short order they came to settle in Englewood, New Jersey, and also could afford an elaborate country place in Hopewell, Hunterdon County. That put them physically at the northern edge of the Philadelphia region at least on weekends, although psychologically they remained part of the New York scene, where many people attracted to publicity seem to gravitate. In 1932 they had a 19-month old son, John, who one evening disappeared from Hopewell, apparently kidnapped.

|

| Charles Lindberg Home |

What followed was a Keystone Kops Komedy in the midst of a publicity storm. The local, county, and state police, plus the FBI struggled with each other for the fame of solving the case. Newspaper reporters from all over the country swarmed down the little country road to set up shop. To illustrate the consequences, a home-made ladder was found sixty feet from the house, but no fingerprints were found by the first investigators. By the time the last investigators were done, the ladder had 150 sets of fingerprints on it. Police involvement on all levels can be summarized as a frenzy to be first to solve the case, followed in time by a frenzy to avoid being known for failing to solve it.