4 Volumes

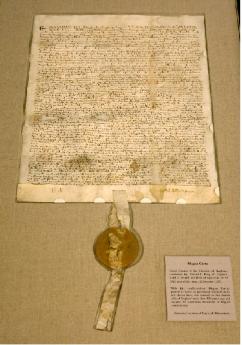

Constitutional Era

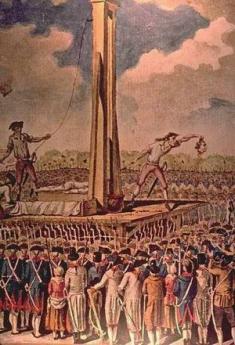

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Great 1929 Depression and World War Two

The Treaty of Versailles probably caused World War II, making WW II just a continuation of WW I.

Revisionist Themes

In taking a comprehensive view of a city, an author sometimes makes observations which differ from the common view. Usually with special pride, sometimes a little sullen.

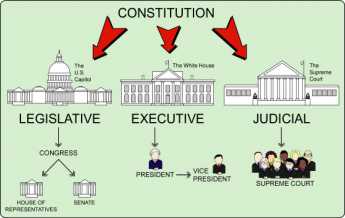

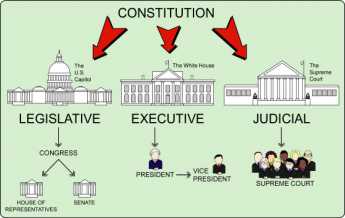

Constitution-tampering is Unwise

.

What Do Unions Want?

.

Looking Beyond Cheap Oil

It can't hurt if we stop global warming, and probably, in the long run, it will matter more than whether the Jews defeat the Arabs, or vice-versa. However, we won't think so if one or the other blows us up. Timing the sequence means it may be important to settle the terrorist issue, sooner.

Rising (China and) Developing Nations

.

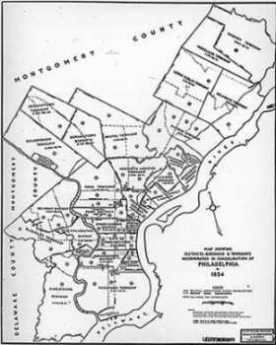

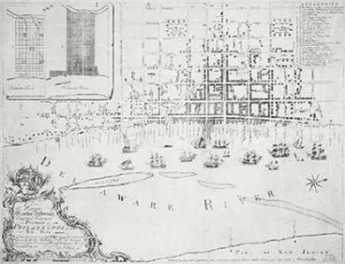

Philadelphia City-County Consolidation of 1854

|

| Consolidation Map 1854 |

Philadelphia is still referred to as a city of neighborhoods. Prior to 1854, most of those neighborhoods were towns, boroughs, and townships, until the Act of City-County Consolidation merged them all into a countywide city. It was a time of tumultuous growth, with the city population growing from 120,000 to over 500,000 between the 1850 and 1860 census. There can be little doubt that disorderly growth was disruptive for both local loyalties and the ability of the small jurisdictions to cope with their problems, making consolidation politically much more achievable. A century later, there were still two hundred farms left in the county which was otherwise completely urbanized and industrialized. For seventy-five years, Philadelphia had the only major urban Republican political machine. By 1900 (and by using some carefully chosen definitions) it was possible to claim that Philadelphia was the richest city in the world, although this dizzy growth came to an abrupt end with the 1929 stock market crash, and the population of Philadelphia now shrinks every year. In answering the question of whether consolidation with the suburbs was a good thing or a bad thing, it was clearly a good thing. But since Philadelphia is suffering from decline, it becomes legitimate to ask whether its political boundaries might now be too large.

|

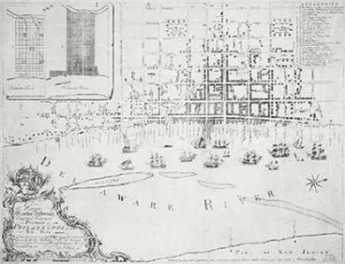

| Philadelphia Map 1762 |

The possible legitimacy of this suggestion is easily demonstrated by a train trip from New York to Washington. The borders of the city on both the north and the south are quickly noticed out the train window, as the place where prosperity ends and slums abruptly begin. In 1854 it was just the other way around, just as is still the case in many European cities like Paris and Madrid. But as the train gets closer to the station in the center of the city, it can also be noticed that the slums of the decaying city do not spread out from a rotten core. Center City reappears as a shining city on a hill, surrounded by a wide band of decay. The dynamic thrusting city once grew out to its political border, and then when population shrank, left a wide ring of abandonment. It had outgrown its blood supply. Prohibitively high gasoline taxes in Europe inhibit the American phenomenon of commuter suburbs. The economic advantage of cheap land overcomes the cost of building high-rise apartments upward, but there is some level of gasoline taxation which overcomes that advantage. Without meaning to impute duplicitous motives to anyone, it really is another legitimate question whether some current "green" environmental concerns might have some urban-suburban real estate competition mixed with concern about global warming. Let's skip hurriedly past that inflammatory observation, however, because the thought before us is not whether to manipulate gas taxes, but whether it might be useful to help post-industrial cities by contracting their political borders.

Before reaching that conclusion, however, it seems worthwhile to clarify the post-industrial concept. America certainly does have a rust belt of dying cities once centered on "heavy" industry which has now largely migrated abroad to underdeveloped nations. But while it is true that our national balance of trade shows weakness trying to export as much as we import, it is not true at all that we manufacture less than we once did. Rather, manufacturing productivity has increased so substantially that we actually manufacture more goods, but we do it with less manpower and less pollution, too. The productivity revolution is even more advanced in agriculture, which once was the main activity of everyone, but now employs less than 2% of the working population. This is not a quibble or a digression; it is mentioned in order to forestall any idea that cities would resume outward physical growth if only we could manipulate tariffs or monetary exchange rates or elect more protectionist politicians to Congress. Projecting demographics and economics into the far future, the physical diameters of most American cities are unlikely to widen, more likely to shrink. If other cities repeat the Philadelphia pattern, the vacant land for easy exploitation lies in the ruined band of property within the present political boundaries of cities, or if you please, between the prosperous urban center and the prosperous suburban ring.

Many American cities with populations of about 500,000 do need more room to grow, so let them do it just as Philadelphia did a century ago, by annexing suburbs. But there are other cities which have lost at least 500,000 population and thus have available low-cost low-tax land which would mostly enhance the neighborhood if existing structures were leveled to the ground. Curiously, both the shrunken urban core and the bumptious thriving suburbs could compete better for redeveloping this urban desert if the obstacles, mostly political and emotional, of the political boundary, could be more easily modified. But that's also just a political problem, and not necessarily an unsolvable one.

Second Mortgages Want to Be First

|

| Chrysler Logo |

In a bankruptcy proceeding, there has long been a traditional conflict between the holders of first mortgages and the holders of second mortgages. It goes like this: since the holder of a first mortgage gets paid first, his incentive is to hurry up the process and get the money. The holder of a second mortgage, however, only gets paid what is left, so this party will normally wish to stall proceedings in the hope the market will improve and give the second mortgage a better payout. Normally, this sort of predictable dispute is covered by contracts, and in any event, most banks hold both kinds of mortgages and are neutral about what is just and fair. In the current banking crisis, however, the major banks have developed an incentive to favor the second mortgage, so they have a new view of what is just and fair. Four of the largest banks hold a total of $440 billion of second mortgages but have very few first mortgages because they were sold off in the securitization process. The banks mostly retained the function of servicing first mortgages, however, so they now have quite a conflict of interest.

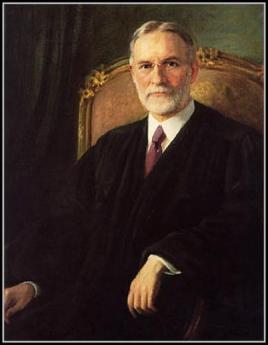

Something like this seems to be going on with the resolution of the Detroit auto makers, with the difference that politicians tend to favor the interest of the auto workers in the bankruptcies because there are more voters to be influenced. And in the case of the auto companies, there are stockholders who will be wiped out by a bankruptcy unless the liquidation of the company assets produces enough cash to satisfy the creditors, secured and unsecured. After all, stockholders aren't creditors at all; they are owners of the company. No matter how things turn out, however, the secured creditors would normally have the first call on whatever is salvaged. So, it's one class of secured creditor against another, or else it is the secured creditors against the "stakeholders", employees or any other unsecured creditor. If the government intervenes, there is the additional issue of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution, which prohibits the government from the "taking" of private property without just compensation. Representative Conyers of Michigan, whose political allegiance is not in doubt, has introduced legislation to prohibit lawsuits in these matters. So now, the prospect grows of a constitutional clash between Congress and the Supreme Court, over the Constitutionality of such a law which denies due process. So that gets us into the fourteenth amendment, too. If we look beyond the technicalities, the looming clash is between President Obama and Chief Justice Roberts. One of them wants to take money from secured creditors and make it available to someone with more political clout; and the other surely wants to preserve the sanctity of contracts, the rights of property holders, due process, and the right of the Supreme Court to declare contrary laws to be unconstitutional.

Unless someone backs off, the situation would seem to be as monumental as Franklin Roosevelt's Supreme Court-packing proposal. Because -- there is every reason to anticipate a 5-4 vote by the Supreme Court, a 5-3 vote if Justice Souter is not replaced by that time, and strenuous efforts to alter the balance.

Special Education, Special Problems

|

| School Bus |

President John Kennedy's sister was mentally retarded; he is given credit for immense transformation of American attitudes about the topic. Until his presidency, mental retardation was viewed as a shame to be hidden, kept in the closet. Institutions to house them were underfunded and located in far remote corners of a state. Out of mind. And while it goes too far to say there is no shame and no underfunding today, we have gone a long way, with new laws forcing states to treat these citizens with more official respect, and new social attitudes to treat them with more actual respect. We may not have reached perfection, but we have gone as fast as any nation could be reasonably expected to go.

However, any social revolution has unintended consequences; this one has big ones, surfacing unexpectedly in the public school system. For example, the king-hating founding fathers were very resistant to top-down government, so federal powers were strongly limited. So, although John Kennedy can be admired for leadership, the federal government which he controlled only contributes about 6% of the cost of what it has ordered the schools to do, and the rest of the cost is divided roughly equally between state and municipal governments. As the cost steadily grows, special education has become a poster child for "unfunded mandates", increasingly annoying to the governments who did not participate in the original decision. We seem to be waking up to this dilemma just at a time when the federal government is encountering strong resistance to further spending of any sort. The states and municipal governments have always been forced to live within their annual budgets, unable to print money, hence unable to borrow without limit. As Robert Rubin said to Bill Clinton when he proposed some massive spending, "The bond market won't let you."

The cost of bringing mentally handicapped individuals back into the community is steadily growing, in the face of a dawning recognition that we are talking about 8% of the population. Take a random twelve school children, and one of them will be mentally handicapped to the point where future employability is in question; that's what 8% means. Since they are handicapped, they consume 13% of the average school budget and growing. The degree of impairment varies, with the worst cases really representing medical problems rather than educational ones. Small wonder there is friction between the Departments of Education and the Medicaid Programs, multiplying by two the frictions between federal, state and municipal governments into six little civil wars, times fifty. An occasional case is so severe that its extreme costs are able to upset a small school budget entirely by itself, tending to convert the poor subject into a political hot potato, regularly described by everybody as someone else's responsibility. There are 9 million of these individuals in public schools, 90,000 in private schools. They consume as much as 20% of some public school district budgets.

All taxes, especially new ones, are bitterly resisted in a recession. Unfortunately, the school budgets are put under pressure everywhere by a growing recognition that our economic survival in a globalized economy depends on getting nearly everybody into college. Nearly everybody wants more education money to be devoted to the college-bound children at a time when there is less of it; devoting 13% of that strained budget to children with limited prospects of even supporting themselves, comes as a shock. Recognizing these facts, the parents of such handicapped children redouble their frenzy to do for them what they can, while the parents are still alive to do it. It's a tough situation because a simultaneous focus on specialized treatment for both the gifted and the handicapped is irreconcilably in conflict with the goal of integrating the two into a diverse and harmonious school community, with equal justice to all.

As school budgets thus get increasingly close scrutiny by anxious taxpayers, handicapped children come under pressure from a different direction. It seems to be a national fact that slightly more than half of the employees of almost any school system are non-teaching staff. Without any further detail, most parents anxious about college preparation are tempted to conclude that teaching is the only thing schools are meant to do. And a few parents who are trained in management will voice the adage that "when you cut, the first place to cut is ADMIN." Since educating mentally handicapped children requires more staff who are not exactly academic teachers, this is one place the two competing parent aspirations come to the surface.

Unfortunately, the larger problem is worse than that. When the valedictorian graduates, the hometown municipal government is rid of his costs. But when a handicapped person gets as far in the school system as abilities will permit, there is still a potential of state dependence for the rest of a very long life. The child inevitably outlives the parents, the full costs finally emerge. We have dismantled the state homes for the handicapped, integrating the handicapped into the community. But when the parents are gone, we see how little help the community is really prepared or able, to give.

Taking Risks Demands Its Price

|

| downturn |

Someday, books will be written about who discovered what, and sold what, to make S & P futures suddenly go up and down 300 points in ten minutes on August 17, 2007, soon followed by violent volatility in many other markets. Confusion reigned for a few days, but within a week there was general agreement about the difficulty: the "spread" of interest rates between risky loans and very safe ones had been too narrow for months, and was reverting back to normal. Risk had been mispriced; a risky loan was just as risky as it ever was, as everyone should have realized. If the risky borrower was unwilling to pay higher interest rates, why would any lender bother with him? Since this had been obvious all along, why had lenders temporarily believed otherwise, charging rates scarcely higher for dodgy loans than for well-secured ones?

|

| Alan Greenspan |

Alan Greenspan (in 1996) had called this question a conundrum, but it's getting easier to understand. The emergence of prosperity in one decade among 200 million impoverished Chinese had resulted in wealth which found its way into international markets, much like a gold rush or the discovery of oil. Sudden huge wealth often cannot be easily assimilated, hence was available to loan at cheaper rates. The globalization of world finance has vastly improved the speed of markets to absorb money gluts, but in this case, had the unfortunate effect of spreading it out into less sophisticated corners of the world economy. It particularly affected residential mortgages, which proved to be the weakest link in the chain of lending and borrowing. Ten years of low-interest rates pushed up the prices of existing homes, tempting builders to overcharge for new construction, and inexperienced buyers to pay those inflated prices with cheap mortgages. Between them, Congress and the banks had devised ways to exploit this situation, making the collapse worse when it came. The interest on home mortgages was preferentially tax deductible, so it became the favorite way to borrow. Banks made it easier to refinance at a lower rate as the spread gradually narrowed. To make it even easier, reverse mortgages converted home ownership into an ATM machine with tax deductibility. Because home prices were steadily rising, banks were willing to reduce down payments, on the assumption that home equity would soon rise to represent the amount formerly required as a down payment. As it would have, perhaps, if homeowners had not promptly drained it out the back door of reverse mortgages. Second homes became a cheaper way to have a vacation; steadily rising prices encouraged outright speculation, called flipping. Congress reinsured mortgages, eventually most of them, through FNMA, and then pressured Fannie Mae to insist on spreading the joys of home ownership to people who could not afford the no-down-payment houses they were romanced into buying. Investment banks offered to buy the mortgages from the local originating banks in order to package them into securitized bundles, which thus deprived the originating banks of any incentive to reject eager buyers, no matter how dubious their credit standing. What is more, this process provided a conduit for spreading bad credit risk into the equity markets, including the equity of the banking system itself, and creating the temptation for hedge funds to start runs on the banks in novel forms. There once was a time when customers lined up at the back door to make withdrawals in a bank run. Since investment banks obtain their deposits by borrowing wholesale, they simplified the process of starting a bank run when the speculative process reversed. Which it did on August 17, 2007, possibly not spontaneously, but certainly inevitably.

Home mortgages were once loans for thirty years; even now, they extend for many years. Homeowners stay in one house for an average of seven years. For legal reasons going back two hundred years, they are non-recourse loans, meaning the house alone is at risk to the mortgage lender, who may normally not pursue the homeowner for assets other than the foreclosure, even if the other assets are considerable. In a housing bubble, this creates a special hazard for lenders during the inevitable decline of house prices back to normal. As house prices fall, as they should and will, many homeowners will find it is cheaper to walk away from a foreclosure than to pay off the mortgage. It has been calculated that potentially as many as 50% of mortgages might eventually find themselves in this squeeze. The situation differs from a car loan, for example. Every new car is worth 20% less than the sale price, immediately after the sale. But this does not tempt car buyers to walk away from their loan, because the car loan is a recourse loan. The uncomfortable prospect is that financial reverses alone might not be the reason homeowners submit to foreclosure. If this particular antisocial behavior loses its stigma, a very large proportion of mortgages could be foreclosed on owners who are perfectly able to pay them off.

|

| Barney Frank and Chris Dodd |

For all these reasons, house prices are the main bubble in an economy overstimulated by cheap money, and mortgage financing is at the root of a banking crisis. The banking system itself is precarious because it too responded to the temptation of abundant credit at abnormally low-interest rates. The process took the form of over-leveraging in order to magnify profits in a competitive market. Greed was not the only motivation; corporate raiders in the form of Private Equity could swoop down on any company unwise enough to accumulate internal cash. The new owner would then substitute debt for cash, and the prudent company (under new management, of course) was no better off than if it had itself over-leveraged. The Federal Reserve limits commercial banks to loaning thirteen times their stockholder equity, but investment banks had the foolhardiness to borrow thirty times equity. A decline of only three percent in the value of their loans wipes them out. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, by the way, is leveraged at over a hundred times its equity. The Fed can print money to pay its debts, of course, but the result is a falling value of the dollar in international exchange and ultimately, world inflation. No one predicts the half-way point in this decline to be sooner than two years, which means a recession lasting at least four years. The first two efforts of public officials to halt the decline, the purchase of toxic debt and direct lending to banks, have been abandoned as failures, and the Barney Frank/ Chris Dodd offer for Congress to repurchase mortgages was simply pathetic, with only two hundred responses when over two million were anticipated. If the public loses faith in the ability of the government to do anything about the matter, prices can be expected to overshoot on the downside, not just return to normal. House prices do need to decline, but slowly enough to avoid a panic. And American banks and businesses need to reduce the extent of their borrowing, but without measures which impair the ability of new businesses to make loans, or the ability of shaky businesses like the Detroit auto industry, to survive.

In closing, a word is needed to explain why the foreclosure of $100 billion of California and Florida bungalows should threaten a collapse in the trillions. Economists have fallen into the habit of equating interest rates with risk; the more risk, the higher the interest rates become. That's true, but the risk is not the only factor affecting interest rates. Since they are essentially the rent paid for the use of someone else's money, interest rates respond to the supply of money interest rates, just as supply and demand of rental housing affect rents. The flood of liquidity from developing countries into the world economy pushed interest rates down, but somehow that was taken to imply that risk had decreased. When interest rates go up again, for whatever reason, the money will effectively evaporate. The best example of this relationship is in the bond market. When interest rates go up, the principal value of existing bonds declines. With interest rates of 5% as an example, bond prices go up and down twenty times as much as the interest rate, but in the opposite direction. To repeat: when general interest rates rise, money in the economy disappears about twenty times as fast. That's a succinct description of what started to happen, when the prevailing risk premium returned to its normal higher level, on August 17, 2007.

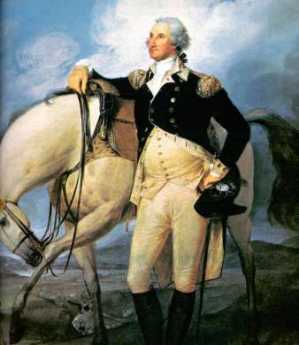

George Washington Demands a Better Constitution

GEORGE Washington was a far more complex person than most people suppose, and he wanted it that way. He was born to be a tall imposing athlete, eventually a bold and dashing soldier. On top of that framework, he carefully constructed a public image of himself as aloof, selfless, inflexibly committed to keeping his word. Parson Weems the biographer may have overdone the image a little, but Washington gave Weems plenty to work with and undoubtedly would have enjoyed overhearing the stories of the cherry tree and tossing the coin across an impossibly wide Potomac. Washington had a bad temper and could remember a grievance for life. He married up, to the richest woman in Virginia.

|

| Potomac River |

Growing up along the wide Potomac River, Washington early conceived a life-long ambition to convert the Potomac into America's main highway to the Mississippi. He did indeed live to watch the nation's new capital start to move into the Potomac swamps across from his Mount Vernon mansion, in a city named for him. For now, retiring from military command with great fanfare and farewells after the Revolution, he returned to private life on this Virginia farm. He made an important political mistake along this path, by vowing in public never to return to public life. During the years after the Revolution but before the new Constitution, his attention quickly returned to building canals along the Potomac River, deepening it for transportation, and connecting its headwaters over a portage in Pennsylvania to the headwaters of the Monongahela River -- hence to the Ohio, then the Mississippi, or up the Allegheny River to the Great Lakes. He personally owned 40,000 acres along this river path to the center of North America. The occasion for a national constitutional convention grew out of a meeting with Maryland to reach an agreement about this Potomac vision, which was being blocked by commercial interests in Baltimore. Ultimately, Baltimore won the commercial race; so it was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad which captured the early commerce to the west. Washington also made deals, ultimately to Baltimore's benefit, with the James River interests, to give them a share of the development of the Chesapeake Bay trade. As a young man, George Washington had acted as a surveyor for most of this region, and as a young soldier had explored the Indian trade to Pittsburgh, actually starting the French and Indian War during this trip. He was to march it again later with Braddock's army. All the while, Washington dreamed of the day. There were competitors; Philadelphia and New York had similar aspirations for their rivers. Take a look at a globe or Google Earth. Comparatively few of the earth's rivers drain too far western beaches. Even today, long-term victory in worldwide water transportation will likely go to one of many eastern rivers linking up with one of the few western ones. The ultimate world-wide goal has yet to be fulfilled for what continues to be the cheapest of all bulk transportation methods.

Washington at age 54 was already richer than most people need to be; a lot of this Potomac dream was a residual of boyhood ambitions enduring into middle age. In a sense, he had the ambition to make his boyhood home the future center of the universe. Although much of his stock in these real estate enterprises resulted in very little extra wealth, he demonstrated his mixture of public spirit combined with ambition by donating the stock in one of the companies to a future national university, to be located across the river near Georgetown. Since that didn't work out, he later placed the nation's capital there. He had consistently been a far bolder dreamer than Cincinnatus, humble Roman citizen-soldier returning to his farm from the wars.

Washington more or less gave up this Potomac ambition for a loftier one. During the Revolution, he had suffered the most infuriating abuse of himself and his soldiers from the state legislatures. Their urgent demands for victories were seldom matched with resources. The Continental Congress representing those state governments in a weak confederation that could not feed and pay its own troops seemed little better. He could be a mean man to cross, but perhaps with General Cromwell in mind, Washington possessed the firmest and most sincere belief in the proper subservience of military to civilian control. These conflicting feelings resulted in earnest obedience to a group of politicians he surely distrusted. This could not be described as hypocrisy; he respected their rank even though he suffered from their behavior. When Congress paid the troops in worthless currency which they promised to redeem after the war, it became clear that either lack of moral fiber or their system of governance led the states and the Congress in the direction of dishonoring their debt to the soldiers. This was a dreadful system, which led to death and suffering among the loyal troops, forcing the General into the humiliating position of assuring the troops Congress would stand by them, while he privately doubted any chance of it. Washington did not easily forgive or forget. Here was a paltry outcome for eight years of war and suffering; this system of organized dishonor must be improved.

He went about achieving his goal in a way that would not occur to most people. He chose a young ambitious agent, James Madison, who had caught his attention in the Virginia legislature, in the Continental Congress, and in the negotiations with Maryland over the development of the Potomac. Washington schemed with the young man for weeks on end about ways and means, opportunities, dangers, and potential enemies. Perhaps he failed to notice some ways where he and Madison fundamentally differed. Madison himself might not have recognized that his years at Princeton in the Quaker state of New Jersey had exposed him to novel ideas like separation of church and state, which were instantly appealing to the two Virginia Episcopalian religious doubters. Many people he admired, Patrick Henry, in particular, wanted the government to be as weak and ineffective as possible. Unfortunately, when Madison's turn later came for assuming the Presidency, he went along with reliance on diplomacy and persuasion until it almost cost America the War of 1812. Acting as Washington's agent in 1788, Madison was assigned to win over the Virginia legislature, make alliances with other states in Congress, identify friends and enemies, make deals. He performed as brilliantly as he would at the Constitutional Convention, so the basic conflict between the soldier President and his politician assistant was glossed over. As long as the original relationship held together, Washington felt it was useful to remain above and aloof, publicly wavering whether this was all a good idea, but fiercely determined to have a nation he could be proud of. There was to be a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, but while Washington was invited, he let it be known he was uncertain whether he should accept the invitation. What he really meant was he would preserve his political credibility for a different approach if this one failed. Considered from Madison's viewpoint however, this clearly meant Washington would dump him if things went badly. Meanwhile, the unknown young Madison on several occasions came to Mount Vernon for three days at a time to talk strategy and give the famous General all the scoop. Today, we would describe Madison as a nerd. The aristocratic Gouverneur Morris never thought much of him. Washington needed him, but there is no evidence he thought of him other than as a glorified butler. Little Madison was awkward among the ladies, a problem inconceivable to either Washington or Morris. But that little mind was surely working, all the time.

Madison was in fact a brilliant politician, a dissembler in a different way, but a severe contrast with his mentor. To begin with, he was a scholar. Both as an undergraduate at Princeton and a graduate student working directly with the great Witherspoon himself, Madison was deeply learned in the history of classical republics. He spent an extra year at Princeton, just to be able to study ancient Hebrew with Witherspoon. But he was innately skilled in the darker arts of politics. When votes were needed, he had a way of persuading three or four other members to vote for a measure, while Madison himself would then vote against it to preserve influence with opponents for later skirmishes. In fact, as matters later turned out, it becomes a little uncertain just how convinced Madison was that Washington's strong central government was a totally good idea. Before and after 1787 Madison expressed a conviction that real sovereignty originated in the states, just as the Articles declared. That was a little too fancy for practical men of affairs, who were uncomfortable to discover how literal Madison was after his break with the Federalists. Twenty years younger than the General. he prospered in the image of being personally close to the titan, and he certainly enjoyed the game of politics. The new Constitution was going to be an improvement over the Articles of Confederation, but Madison did not burn for long with indignation about injustice to the troops, or disdain for nasty little politicians in the state legislatures. These were problems to be solved, not offenses to be punished. The new Constitution was a project where he could advance his career, skillfully demonstrating his prowess at negotiation and manipulation. This is not to say he did not believe in his project, but rather to suspect that he was a blank slate on which he allowed Washington to write, and later allowed others to over-write. He was eventually to modify his opinions as a result of new associations and partners, and since he succeeded Jefferson as President, it was personally useful to adjust his viewpoints to his timing. What would never change was that he was an artful politician, while Washington hated, absolutely hated, partisan politics.

This is not just an emotional division between two particular Virginia plantation owners, but an enduring thread running through all elective politics. Washington set the style for generations of citizen leaders in America. In his mind, a person of honor distinguishes himself in some way before he enters public office, so on the basis of that honorable image, presents himself to voters for public office, and naturally is elected to represent their interests. He is expected to compromise where compromise is honorable and publicly acknowledged, in order to achieve one desirable outcome in concert with other outcomes, in some ways inconsistent but still honorable in combination. He reliably will not vote for either issues or candidates in return for some personal consideration other than the worth of the issue or the candidate, with the possible exception of yielding to the clear preferences of his local district. Such a person is not a member of a political organization very long before he encounters another group of colleagues -- who regularly swap votes for personal advantage, join a group who agree to vote as a unit no matter what the merits, and recognize the frequent necessity to talk one way while secretly voting another. The first sort of politician is usually an amateur, the second type is typically a professional politician. Although it seems a violation of ethics and common public welfare, the fact is the professional vote-swapper almost always beats the sappy amateur. The response during the Eighteenth Century was for idealists to condemn and attempt to abolish partisanship and political parties. The American Constitution does not make provision for political parties and other forms of vote-swapping or even anticipate their emergence. Although Madison ignited the process in the United States, Jefferson really organized it; every recent politician except Adlai Stevenson has openly participated in a version of it. That the Constitution has still not been amended to provide for parties seems to reflect a persisting nostalgic hope that somehow we can return to Washington's stance.

Washington's conception of open representative politics was not entirely perfect, either. In order to maintain an image of impartiality, Washington and his imitators isolated themselves in a cloak, holding back their true opinions in a sphinx-like way that hampered negotiation. Unwillingness to be seen swapping votes can lead to an unwillingness to compromise, and in the final analysis, the difference is one of degree. However, the over-riding issue is that each representative or Senator is equal to every other one. When vote-swapping gets started, it leads to placing power over supposed equals in the hands of the more powerful manipulators, masquerading as political leaders. Ultimately, it leads to the adoption of house rules on the very first day of a session which force lesser members to surrender their votes to a speaker or minority leader or committee chairman, when the theory is that there is no such thing as a lesser member. The claim of a party-line politician is that he obeys the will of the party caucus; the reality is usually that he obeys the will of some tough, self-advancing party leader. The final reality is that most legislatures must now deal with thousands of bills per session, leading to the necessity of appointing someone to set priorities, which in turn leads to the power of party leaders over their grudging servants. These various subversions of the equal rights of elected representatives can lead to such discrediting of the system that honorable people may refuse to stand for office, leaving foxes in charge of the hen house. Benjamin Franklin, who was to play an invisibly controlling role in the impending Constitutional Convention, had his own way of coping with the political environment. "Never ask, never refuse, never resign."

Obamacare Follies, Executive Summary

OBAMACARE FOLLIES

1. Mandates: Individual vs. employer. Neither one covers the "illegals". a. Individual mandate lays cost on young healthy, subsidizes older, people. b. Employer mandate costs small business, subsidizes large. c. Neither mandate addresses the tax issue which caused the problem. d. The illegals concentrate in five states bordering Mexico -- start there, don't leave it as a left-over. 2. Cost control: the CBO sank this legislation in one sentence. 3. Cost control: the Town Meetings angered people with good health insurance, who don't want to see it injured. That's 85% of voters. 4. Cost control: Taxing providers and suppliers only raise health cost. 5. Cost Control: Home care may no longer be cheaper than hospital care except as a reimbursement quirk. 5. Increasing access is incompatible with cutting costs. Choose, don't dissemble. 6. Health care is a problem but does not create priority over two wars and the worst depression in eighty years -- none of which is now going well. Push the reset button.

THE PECULIARITIES OF OBAMACARE POLITICS

1. Required Reading: "The Road to Nowhere" by Jacob Hacker a. "Budget" Reconciliation. b. Cloture: terminating debate. c. Bob Dole: Public Option is a sacrificial feint. 2. Role of Gerrymandering a. Seniority puts extremists in control of Congress b. Gerrymandering puts moderates at greatest political risk. c. 2010 is a redistricting year, especially in New Jersey and Florida. d. Some political party will someday assert national party control over nominations to safe seats. 3. The hidden role of the Governors' Medicaid scam. 4. Small states need regional health insurance regulation; big states hate it. 5. The unconstitutionality (X Amendment) of mandates and the impeachability of presidential macing of political support.

WHAT OBAMACARE OUGHT TO SAY

1. Eliminate or modify the tax preference for employer-purchased insurance. 2. Repeal or modify the McCarran Fergusson Act to permit interstate insurance. 3.Restrict patents to those drugs which convince FDA of their unique value. 4. Mandate price/cost ratio to be displayed next to medical prices. 5. Pay hospital claims only after proof of transfer of responsibility after discharge. 6. Similarly, pay for lab charges for last day in hospital only after proof of reporting. 7. Override Maricopa Case of 1982 legislatively. 8. Restore the PSRO system. 9. Federally pre-empt anti-HSA state laws and regulations. 10. Subject Medicare debt to creditor disciplines: a. Suspend COLA and add-ons until proof of solvency. b. Merge Medicare and Medicaid, thus ending the cross subsidy.

The King's Last and Final Word

|

| King Charles II |

In 1662, King Charles II of England signed a charter, giving a strip of land in America to the inhabitants of Connecticut, and that land to stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. And then, eighteen years later, the same king signed a second charter, giving much the same land to William Penn. As lawyers say, these are the facts. In the many lawsuits, arguments, and wars which followed, no one ever seriously raised the point that King Charles was unaware that he was giving the same land twice, so it must be assumed he knew exactly what he was doing, and did it on purpose. In fact, he did this sort of thing many times, in other cases. The legal disputes which this double-dealing inspired, are therefore entirely concerned with whether the King had a right to do it, and if so, whether that right would normally be recognized (i.e. durable) when we threw off the King and became a republic. The matter was considered by many courts many times, and in every single case, the judgment was in favor of Pennsylvania.

|

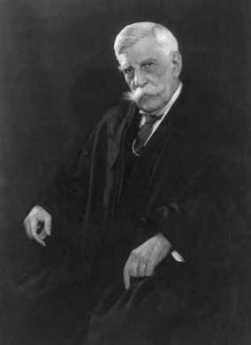

| Oliver Wendel Holmes Jr. |

Consider Connecticut's probable attitude toward all this. The colony was settled by Calvinist dissenters, so-called Roundheads for their surprisingly contemporary haircuts, adherents of General Cromwell, executioners of King Charles I during English Civil War. They gave Old Testament first names to their own children, and had always known they couldn't trust that licentious King. Giving their land away after he had promised it to them was just about what they always expected. When, after seventy years of growing families of fifteen to seventeen children, they discovered that Connecticut soil was merely a pile of pebbles left by the glaciers and covered with a thin layer of topsoil, they became even more convinced they had been cheated in the first place, and the bargain was no bargain. The reverse side of this enduring religious hatred will reappear in a few paragraphs.

The Proprietors of Pennsylvania, by this time no longer pacifist Quakers, but while descendants of William Penn, converted Anglicans and great friends with the King, took the matter calmly. The Connecticut lawyers were saying that if you sell or give away some land, it is no longer yours, so you can't give or sell it a second time. That is the modern view perhaps, but the English-speaking world was changing from a feudal, semi-nomadic, culture into a settled agricultural country where fixed boundaries were only starting to be important. That's where the world was going, but at the time King Charles gave away the land, it was far more important for the King to be able to reward successful underlings, and punish rebellious tribes, as the situation warranted. Ownership of land then seemed a nebulous thing at best, and the King was the best judge of how things should be divvied up.

Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced his book on The Common Law, by warning "The life of the law has not been logic, it has been experience." For life to go on and prosperity to endure, some decision must be made and held to, right or wrong. Stare decisis. That's of course fine for judges to say, but it must be observed that when people divide up on this question, where they stand depends heavily on where their ancestors stood on the English Civil War, and where their ancestors happened to be living during the so-called Pennamite Wars. As matters turned out, courts kept deciding in favor of Pennsylvania, and Connecticut kept bringing it up, again.

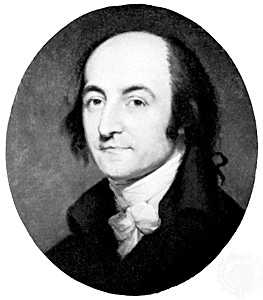

Albert Gallatin: Enigma Furioso

|

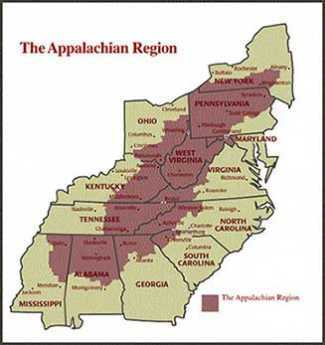

| Appalachia |

Abraham Alphonse Albert Gallatin was born to a rich, famous and noble family in the French part of Switzerland in 1761, but soon became a rich orphan fleeing to America in the 1780s to escape overbearing and grasping relatives. He started out in America teaching French at Harvard but soon purchased Friendship Hill, a 600-acre estate south of Pittsburgh along what was to become the National Road. At first, he ran a busy general store but soon branched out into successfully buying and selling real estate. Although Uniontown now seems a lonesome hermitage in Appalachia, it was then part of the area disputed between Pennsylvania and Virginia, coveted by both states because it seemed like the main route to Ohio when Ohio was the Golden Frontier. Friendship Hill is now a National Park, near Fort Necessity, also near General Braddock's grave, and the birthplace of George Catlett Marshall. So it had its attractions, but Gallatin led such a frenzied life it is hard to believe he spent much time there. There is a reason to believe he was one of the main instigators of the Whiskey Rebellion. Hamilton, and probably Washington, certainly thought so.

|

| Albert Gallatin |

Almost immediately after arrival in America, Gallatin threw in his lot with Thomas Jefferson in resistance to the centralizing, Federalist, qualities of the new Constitution. Both of them were looking for more liberty than the Constitution offered. The movement they led became the anti-Federalist party and would have been the anti-constitution party except for reluctance to oppose the towering figure of George Washington. Gallatin's French loyalties seem to have overcome his aristocratic family background in supporting what enemies of the French Revolution had called Jacobin (or "Republican") notions. His Swiss background additionally gave him great credibility in high finance in backwoods America. In spite of being rather out of place among Virginia Cavaliers, his personal qualities seem to have made him a natural politician. He hated Hamilton's idea of the National Bank, arguing against it effectively in the unsophisticated company. The issue was not so much opposition to banking, but to government dominance in central banking. He was certainly right that mixing the two created a constant risk of inflation from yielding to political demands, an empirical observation almost without any exception for 800 years. However, it was too early in the history of central banking to perceive that it was debtor pressure which promotes inflation. Governments are almost invariably debtors themselves, whereas the elites he was attacking, in general, become creditors, resisting inflation. Inflation is merely a variant of defaulting on debts, which debtor governments happen to have at their disposal because they control the currency.

At this early stage of central banking, America was largely using its vast amounts of land as a substitute for money, but quickly adapted to Hamilton's new monetary system which was far more flexible. Gallatin later played a role in the chartering of both the Second and the Third Banks, although his motives here were somewhat different. (Government caps on interest rates induced the Banks to lend to only the best risks, which amounted to favoring Philadelphia over the frontier, Gallatin's main constituency.) He was appointed U.S. Senator for Pennsylvania at the age of 32 but was evicted on a straight party vote on the ground that he had not been an American citizen for the required nine years. It seems likely that accusation was correct. He was soon elected a Congressman, becoming Chairman of Finance (later called Ways and Means), the majority leader after five years. In retrospect, while it seems perplexing that a sophisticated financier would oppose a central bank, his opposition may have been mainly against having politicians operate one, a rather unavoidable consequence of government control. Hamilton's idea that deliberately going into debt was a way to establish "creditworthiness" was denounced as particularly offensive by those who disdained indebtedness as the most dangerous sin of commercial life. The anti-Federalists were clearly wrong on this point, but it is possible to sympathize with their suspicions. Even today, the unwillingness of banks to lend money to someone who has no history of the previous borrowing is one of those things which seem so natural to bankers, and so irritating to apostles of thrift.

It remains unclear to history whether Gallatin had really never believed what he was saying, or had gradually changed his mind as he gained experience. He did confess or perhaps suddenly realize his error as the War of 1812 approached and he was Secretary of the Treasury. In this awkward event, he found himself charged with organizing the finance of a war with no way to do it. What was worse, Jefferson relentlessly pursued the closure of the National Bank for ideological, even fanatical, reasons; and Jefferson was the boss. The resolution of this conflict was to enrich Stephen Girard even further, while forcing Gallatin to a humiliating public reversal of stance. Nevertheless, America simply had to have a bank to fight a war. It is greatly to Gallatin's credit that his frenzied and obviously sincere entreaties to the bewildered Jefferson and Madison then saved the Nation from a disaster of foolish consistency. In a larger sense, the dramatic reversal of stance also played a role in shifting American sympathies from France to England. American sympathies were then wavering. On one side, there was gratitude to the French for bankrupting themselves with unwisely large loans to our struggling revolution, and for allying themselves with that revolution, soon imitating it with a revolution of their own against the common slogan, oppressive monarchy. True, there was more than a little hankering for the annexation of large chunks of Canada. That was one side of it, which Lafayette, Girard, Gallatin, and Jefferson labored to enhance, probably with their eye on French Quebec. On the other hand, there was that appalling genocide of the Jacobin guillotine, which Napoleon soon threatened to extend to all European monarchies within his reach. The Seven Years War, which we called the War of the French and the Indians, had left memories in America that French ambition could extend from Quebec to Louisiana and include Haiti. The French once even occupied Pittsburgh, and their Indian allies had scalped settlers in Lancaster. That was not so long ago. Furthermore, the English invention of the Industrial Revolution was immensely attractive to artisan Americans. Ultimately, we made our choice for steady prosperous commerce of the British sort, rather than glittering glorious conquest, of the French style. By 1813, Gallatin had served longer as Secretary of Treasury than anyone before or since, and earlier had a more distinguished career as both Congressman and Senator than all but a few have ever achieved. When he was offered the position as a commissioner to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812, it was natural to expect that it would be the final act of his long political career. It was, however, only the beginning of a ten-year diplomatic career as Ambassador, first to France and then to England. Following that with still another new career, he took up academic work, returning to America to found New York University, personally establishing the academic discipline of study in Indian Affairs and language, and founding the American Ethnological Society. Gallatin wrote two books about Indian language patterns and first suggested that the similarities between the languages of North and South American Indians probably meant they were related tribes. In another sphere, Gallatin is credited with originating the American doctrine of manifest destiny.

While skipping from one distinguished career to several others, Gallatin never forgot he was a banker. He wrote the charter for the Second National Bank ("Biddle's Bank"), plus the Third Bank of Pennsylvania, and founded the National Bank of New York, which was named Gallatin's Bank for a while, before gradually evolving into what is now called J.P. Morgan Chase Bank. As a diplomat, he negotiated many boundary disputes, including Oregon, Maine, and Texas. He bitterly opposed the annexation of Texas.

When it comes to writing about Gallatin, there is so much to say it is hard to say anything coherent. He was such a virtuoso of public life that he defeats his biographers in their central task, of telling the world what he was like. There haven't been many if indeed there were any, enough like him to offer a comparison. And yet history has not been kind to him. He can comfortably claim the title of the most famous American, that no one since has ever heard of.

Cost of K-12 Education

|

| Kids In the Classroom |

The April 11, 2010 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer contained the thirteenth annual "Report Card" on schools of the eight-county Philadelphia metropolitan area. The report is eighteen newspaper pages long, mostly statistics, a real contribution to the area's understanding of itself in an important area of concern. Perhaps some future edition will take the data for a thirteen-year period and measure how things are changing over time, for better or worse. Trend analysis is often more illuminating than a snapshot of one moment in time but requires uniform data definitions. Achieving uniform year-to-year definitions can itself cause some other problems. For example, the Pennsylvania figures for teachers' salaries makes a measurement cut at $80,000 per year, while the New Jersey data samples salaries over $75,000. It's therefore hard to compare salaries between the two states, but if you want to compare a district with itself over time, you have to continue to report it the way you did last year. It somewhat depends on whether you want to study the two state governments or the individual school districts. Therefore, compromises of data collection made years ago, continue to be made for the sake of consistency. This sort of rough adjustment is just part of data management and usually proves to have had an innocent beginning. Inflation and population migration similarly make it difficult to collect data year after year which will illustrate a meaningful trend in future decades. Sometimes you measure things at the state level because small but important trends just don't show up meaningfully in the smaller school districts. That's not a criticism, that's just the way it is.

Buried within the long columns, a few numbers do fairly scream for attention. Philadelphia's 163,647 school children are 87% non-white, a "minority" group that badly needs educational help if they are to become productive members of a globalized, service (non-industrial, non-farm), economy. Unfortunately, the City is stretched to spend $11,426 per student, the lowest average of any district in the 8-county area. The lowest, remember, of several hundred neighboring districts. At the same time, the City is fast approaching bankruptcy because its present tax level drives away business. The resulting unemployment raises welfare costs, and fosters higher expenditures on crime and punishment, drawing resources away from education. The credit of the City is shaky, so closing the gap by borrowing gets harder all the time; this is a terrible moment to experience an economic recession. If you dig into this data just a little, you get an important illumination. Philadelphia teachers' salaries are lower than 80% of the neighboring region, but compared with property values, they are in the middle of the range. We are in the middle of a recession, but worse still we are in the middle of a real estate recession, where most school taxes are based. Think that over; that has to mean property values are depressed in the City and will go even lower if real estate taxes are raised. Alternatively, rising property values would result in rising tax revenue, and then the City could afford to pay teachers enough to attract them back into the City school system. Paying the lowest salaries for miles around almost certainly affects the quality of the teachers attracted to work here. At the moment, however, the City doesn't dare raise taxes. But it also doesn't dare let the school system fall apart. The city has passed the tipping point where this will correct itself, and must somehow do something dramatic to get to the other side of that tipping point. Vehement union demands make it seem that all this problem needs is more money. That's far from enough; since it's hard to see where the money would come from, it's anyway vital to be thinking of nonfinancial solutions as at least as important as financial ones.

The school system doesn't show up very well in the statistics. More than half of the city high schools send less than half of their students to some kind of college. Leaving college quality to one side, only one of the hundreds of eight-county school districts also sends fewer than half its class to college; most of them send 80-90%. And the one non-Philadelphia school district in the region which sends only 38% to college is the City of Chester, which has problems similar to those of Philadelphia. Outside the city limits, this metropolitan region is doing fairly well in the struggle to educate its next generation for a globalized economy. But unless something pretty dramatic is done, the inner city will not be able to cope with low-cost foreign labor, nor will it be suitable for the better-paying jobs, while employers could actually be starving for educated labor, but totally unable to make use of uneducated job applicants, once the recession is over.

For centuries, Philadelphia subsidized the farm regions of Pennsylvania, in the sense that it contributed more state tax revenue than it received back in benefits. Ever since World War II, however, the rest of the state has been subsidizing Philadelphia and hates this situation with a lethal political passion. During the last half of the 19th Century and particularly with the automobile in the early 20th Century, the agricultural workers of Central Pennsylvania have migrated to the city to take industrial jobs. There is no going back; agriculture now only employs 2% of the nation's population, industrial employment is going in the same direction. The former agricultural/industrial workers must somehow get themselves educated enough to face new challenges. We have twelve million illegal immigrants in America; the appalling thing is to hear we may need their labor because somehow twelve million legal immigrants aren't up to the task. Once they get mixed up with recreational drugs and the criminal justice system, what little chance they had for advancement rapidly fades. The Chinese tackled this same problem by forbidding reproduction. Industrial Europe tackled this problem with famine and wars. Because Americans can't even discuss such approaches, it looks as though there is nothing to do, but that isn't so. We've just exhausted our traditional approaches.

During the 19th Century, for example, the Catholic school system of Philadelphia was one of the wonders of America. That's what Cardinal John Henry Newman was all about, and he richly deserved to be sainted. For reasons remote from this discussion, the Catholic Church school system lost considerable vigor in America. That sad process seems to be continuing a downward spiral, so it's doubtful it will revive soon. Perhaps the charter school approach can fill the void, perhaps a voucher system of school choice has something to offer. Meanwhile, Catholic schools are feeling a drop in enrollment, some are closing; the most common complaint is that the current recession in the economy has made the tuition to Catholic schools a serious handicap to competing with charter schools in their neighborhood, where the education is said to be at least as good, and free. A shorthand description of the politics here is the public school teachers union fear vouchers for school choice, and the Catholic schools fear tuition-free charter schools. What might be helpful would be a realignment of incentives within a voucher system which would benefit all three school choices instead of victimizing the public schools; standardized testing at least opens the way to devising a reward system to inform the flow of public subsidies. No one is interested in a system like that in France, where every student in every school is looking at the same page of the same textbook every day. The goal is to reward objective educational improvement, under any or all management structures; and the main problem is to be objective about the measurement of it.

Maybe we should legalize recreational drugs, but then maybe we should legalize recreational crime; bad ideas will always come forward in a crisis, and someone must have the fortitude to reject them. And someone has to have the fortitude to face down the Teachers' Unions; it was better if that someone is black. Someone must face down organized crime, quite regardless of the crime product popular at the moment; it was better if that someone could be of Italian extraction. Right now, it looks as though the state government of New Jersey came close to being dominated by an informal network of gamblers, criminals and public service unions. We are close enough to watch with awe as a former prosecutor takes a meat ax to what he learned when he was an investigator. One hopes for his success while watching uneasily to see if he can himself remain within legal norms. Philadelphia remains of the mindset of buying its way out of the education problem; that's not going to work.

For one thing, it seems to have been unsuccessful in neighboring Camden. Once more referring to the Inquirer's educational report card, Camden produces some documented warnings. Camden spends $16,131 per pupil, about half again as much as Philadelphia. Camden teachers are paid in the top quintile for the state, class size is nearly the smallest in the state. About 88% of the money is contributed by the state government, which temporarily at least solves that particular issue. In spite of this spending, Camden has the highest crime rate in America, its school population remains 99% nonwhite, only 38% of those who struggle to high school go on to college, and their SAT scores are the lowest or nearly the lowest in the state. Perhaps in time, the education will improve; there is little sign the economics of the city has improved. Lots of abandoned building have been torn down, nothing new has been constructed except with public tax money. Money may be necessary for urban revival, but it certainly is not the central solution. Until the politics improve, there is little likelihood that civil society, non-government organizations, can produce the leadership so strikingly missing. The corrupt government must at least get out of the way.

Because more money without civic engagement probably cannot solve the problem, gimmicks to beg or borrow money may be a distracting blind alley. Philadelphia consolidated the city with the surrounding suburbs 150 years ago. That seemed for a while to bring prosperity, but its instability in the face of declining resources is one of the main reasons the 1929 depression was so particularly destructive to overextended Philadelphia. The city was no longer right-sized for its population. When the urban population fled to the far suburbs, not only was further political consolidation impossible, the intervening deserted areas of West Philadelphia, Germantown, and North Philadelphia became slums, so large in area as to be beyond all hope that population growth could soon fill them. As you travel on Amtrak either north or south, the border between Philadelphia slum and suburban greenery is sharply visible at the artificial political borders. The slums grew outward to the border and stopped, the suburbs grew inward to the border and stopped. If the borders moved closer to City Hall, the suburbs would follow; just look at Conshohocken. There's little likelihood of that happening soon, and most of the reason is the present centrifugal mindset of the populace. In their view, the further out you go, the richer you will get. When reality sets in on that particular delusion, perhaps the matter can be reopened. The point right now is that we tried to make the suburbs support the urban core, once, and that opportunity is all worn out. It would be much more useful, not necessarily easier, to introduce some civility into state government.

Pea Patch Island

|

| Fort Delaware |

There's a tradition that a boatload of peas ran aground on the mudflats of Delaware Bay near Salem in the Sixteenth Century, turning the flats into a patch of peas. In any event, the island is known to have been growing in size for centuries, and now is home to about 12,000 families of Herons. The number of mosquito families has not been accurately counted as yet, but they are even more numerous. The island doubled in size when the Army Corps of Engineers built the present Fort Delaware on it in 1847-59.

The War of 1812, which included the burning of Washington DC and bombardment of Baltimore, propelled America into a frenzy of coastal defense, and the first fortification of Pea Patch Island took place in 1813. A plan was adopted by Congress in 1816 to build 200 coastal forts, and about forty of them were actually completed by the time of the Civil War. These forts all had a similar appearance; the most notable example of the style was at Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina, which was nearly complete by the time of its famous bombardment. In fact, it was first hastily occupied by Northern defenders arriving just in time to be evicted. In essence, these forts were huge walls of bricks with a concrete outer shell, holding a couple dozen very large cannons and a parade ground.

The new river defenses of Philadelphia were to be provided by three forts, Fort DuPont at the mouth of the old Delaware-Chesapeake canal, Fort Delaware on the island, and Fort Mott on the New Jersey side. You can now take a ferry ride to all three, between April and September; it's a pleasant afternoon excursion. Not so many years ago, you had to go into an ominous little taproom in Delaware City and ask in a loud voice if someone wanted to take you to Pea Patch in a fishing boat. The scene was reminiscent of old movies about derelicts hanging out in Key West, complete with George Raft and Ernest Hemingway, but now the National Park Service has given it the characteristic NPS spruce-up, with pamphlets and restrooms.

The place never had any serious military activity except when it was used to house Confederate prisoners after the Battle of Gettysburg. Over 12,000 prisoners were brought there, and there were about 3000 deaths among them. Historians have compared the treatment of Confederate prisoners with the treatment of Union prisoners at Andersonville, Georgia, and it would be hard to say which place was worse. There are certain diseases of poor sanitation, like typhoid, cholera, amoebic and bacillary dysentery, and hepatitis, which decimate all concentration camps at all times. And adding to them the mosquito-borne diseases of both Delaware and Georgia at the time, you don't really need to assert prisoner mistreatment to account for the morbidity and mortality. Undoubtedly there was some of that.

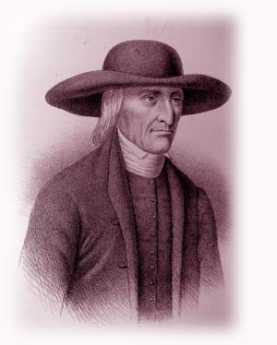

The No-Doctrine Doctrine

|

| quaker |

Although Quakers have long been famous for good relations with the Indians, both groups strongly prizing simplicity and keeping your word, few Indians converted to Quakerism. Indians would attend the silent meetings and listen respectfully, but in the end, Christian converts were far more likely to convert to the Moravian Church. To resist defining your common beliefs creates automatically a problem for explaining what you believe. It becomes acceptable to believe a wide range of things, but it is also acceptable to believe very little. Not surprisingly, the two great religious schisms of the Quakers have broken their unity on just this point.

|

| A History |

The first great Quaker schism was created by one George Keith (1638-1716), who was born a Presbyterian and died an ordained Episcopalian. For several decades, however, Keith was one of the foremost leaders of the Pennsylvania Quakers, partly as a result of being just about the best-educated man of the Colony. His leadership, however, led him to crave a more defined set of Quaker doctrines, and when he carried this idea too vigorously, he eventually encountered implacable opposition which in time caused him and his considerable number of followers to be expelled from the Society of Friends. (George Keith should not be confused with Sir William Keith, whom Hannah Penn appointed as governor of Pennsylvania in 1717.)

|

| Elias Hicks |

The first great schism was thus about whether there might be too little defined doctrine in Quakerism. The second great schism, by contrast, grew out of the feeling there was too much doctrine. Led by Elias Hicks in 1830, the Hick sites split off from mainstream Quakerism in a quest for more simplicity, less religiosity, more silent contemplation of the Inner Light. In a sense, the outward show of protest in the black hats, plain dress, the plain speech had provoked a reaction that these things were no longer simple, they were ostentatious. Too many people were being "eldered", too many people were being "read out of the meeting" for violating doctrinal rules.

Curiously, both rebels were cast out, but over each following century the church as a whole gradually adopted what was largely their view of things. After Keith, Quakerism became more rigid and formalized. After Hicks, it became more mystical and free-thinking.

By insisting that in spite of turmoil it caused no doctrine was to be defined, Quakers have edged into the negative position of defining what they are not. Unlike the early sects of Christianity, Quakers have discarded the hope of miraculous divine intervention as a reason to behave in a Friendly Christian way. No one is apparently going to revive your bones from the tomb, feed your multitudes with forty loaves, or descend from Heaven and drive your enemies into the sea. Neither a later reward in Heaven nor a forthcoming everlasting punishment in Hell can be regarded as either very likely or much of an incentive to good behavior. Other religions may believe these things and might even turn out to be right, but Quakers feel the unembellished Golden Rule is a sufficiently understandable motive for conduct.

And gentle indirection is often a better way to persuade others than thundering oratory. The story is told of a visitor who found himself in a Quaker gathering and made polite conversation by asking what the Quaker position was on the Trinity. A sweet old gentleman is said to have smiled and said, "We believe in the following Trinity: The brotherhood of man, the fatherhood of God -- and the neighborhood of Philadelphia."

Children's Scholarship Fund (1)

|

| Children's Scholarship Fund of Philadelphia |

Ida Lipman recently visited the Right Angle Club, to acquaint members with the nature of the club's new charity, the Children's Scholarship Fund of Philadelphia. This fund could be seen as a response to the rising realization that the nation's leading social problem is fast becoming one of upgrading the educational strength of the current generation of poor people, who face hopeless odds competing for unskilled jobs against a vastly larger population of foreign poor people in a globalized economy. Our poor people can never hope to rise out of poverty by taking jobs that foreign competitors are willing to perform at even lower wages. And while everyone hopes our poor people can take on better-paying jobs, it requires better education to do it. Ultimately, the question for America is whether to place the emphasis on better teaching or better learning, and the two are not quite the same thing.

The educational problem of motivating children to higher attainments than their parents is a difficult social task in both urban and rural districts, but self-defeating peer pressures to hold down their classmates somehow seems a stronger force in the urban settings. In both environments, of course, the educational attainments of both the parents and the teachers have been aimed at a lower level than the task requires. It somehow proves unrealistic to shift expectations as rapidly as we need to, and part of the present problem is that the education industry has become demoralized by repeated defeats. Consequently, we are certainly lucky that philanthropic donors have been willing to support some radical experiments in the whole educational experience, including students, teachers and parents.

Thus, the Children's Scholarship Fund has been willing to dispense several thousand scholarships to private schools in the Philadelphia region, purely by lottery, without regard to the traditional guidepost of student merit. This policy would probably be disruptive if scholarships were universally available, undermining the spirit of meritocracy which is so central to our educational system. But since we are only partially addressing the failures of a system of universal free public education, a stronger argument can be made that changing the culture occasionally requires that we set aside the traditional incentive of rewarding the behavior we seek. The hope is that a demonstration project with such a radical change will set other motives into motion. Resources are limited; it is recognized that among the ninety percent of students who fail to receive the scholarship by lottery, there will be many who are more talented than the few who are lucky enough to get an award. The point is easily overlooked however that scholarship students must apply for this lottery, and be supported by partial financial assistance from their parents. These parents must sincerely want to raise the educational goals of their children, and convey that motivation to the kids in whatever way they are able to convey it. The pressure of less lucky playmates and neighbors to hold them back, it is hoped, will be lessened by the simple recognition that a lottery gives everyone an equal chance, provided only that they step forward and pledge themselves to try to succeed.

|

| John Walton of the Wal-Mart family |

It's a bold and imaginative approach, a highly counter-intuitive one. John Walton of the Wal-Mart family matches the contributions of other donors at fifty cents on the dollar through his family foundations, which was jointly founded with Ted Forstmann of the Wall Street firm. Many longitudinal studies will eventually show how much this bold and charitable venture really helps the students and the community; since it is private money in use, criticism should be held back until the results begin to be apparent. To whatever degree and in whatever way the scholarship fund is a success, the public must be willing to praise both its spirit of generosity, and its willingness to take a chance. Let's all mark this down in our notebooks, to see how it all turns out in ten or so years.

Tour of Duty in 'Nam

|

| Vietnam War |

Col. Dan McCall talked to the Right Angle Club about wartime experiences in Vietnam recently. He really didn't want to, though he was being asked to talk about retirement planning, or asset allocation, or something else he knew something about. But the Program Chairman this year is also a Colonel, and wasn't about to be talked out of it; he wanted Vietnam, sir, and nothing else. So, for the first time in forty years, he did. He hadn't talked about it with his family or, during a career rising from Lieutenant to Colonel, with his associates in the National Guard.

Perhaps a little slow and fumbling at first, we heard of going to a place where it's 120 degrees in the shade, every day. Where he fainted from a heat stroke on the first day off the plane in Saigon, and soon found that it happened to everyone. Within thirty days, every single person had dysentery. The plane that lands troops in Saigon doesn't turn off the engines, and takes off as soon as the last man deplanes. As well it might because it attracts sniper fire as it takes off. Once there, the only form of transportation for anyone going anywhere is by helicopter; plenty of peasants with chickens in their laps are taken along, too.

|

| Ho Chin Minh Trail |

His unit, the 82nd Airborne, was deployed to the west of Hue, the ancient capital. The country is near the border with North Vietnam, and the land is a fairly narrow strip between the ocean and the Laotian border. The Ho Chi Minh trail, where the enemy comes from, is just over the border inside Laos. Our troops never go there, but B-52 bombers go there plenty, leaving impressive craters in the ground. The unit was mortared every night, and rockets made an impressive noise as they went overhead toward Hue. The American forces almost never went out at night. Deployments in the jungle lasted 45 days, without baths or toilets; mostly, you walked into the enemy by accident on the trail. One of the prizes was a Chinese officer, carrying much better maps of the region than the American Army had. One night, sniper fire seemed to be coming from a small island in the river, and the response was to send thousands of shells back, filled with 3-inch steel darts. The next morning, every tree on the island was normal enough on the Laotian side, but nearly covered with steel darts on the Vietnam side. Although the command from headquarters was to report a body count, there were no bodies to count. At the end of one 45-day deployment, there had been no food or water for three days. When the "ships" came to take them out, there was a celebration with rice wine. You make rice wine by soaking stalks of rice in water, letting it ferment. The water is pretty murky, to begin with, and gets worse as it ferments; you have a good time, anyway, with the villagers bringing in a pig to roast.

|

| 82nd Airbourne Patch |

The CIA had its own private army, Rangers and Special Forces. There were local mercenaries, mostly from Thailand. The 82nd Airborne - The All American Division - had a tradition of parachute jumping in every military engagement since World War II, but in the jungle there was no place for, or point in, jumping. But at the end of their deployment, they jumped once, anyway. When you got home, the movies were kind of a joke, but Apocalypse Now came close to giving the right feeling. Although of course people asked what it was like, you didn't talk about it. No one did.

One member of the Right Angle Club who had spent a year there, muttered an answer. "And people didn't really want to hear about it, either."

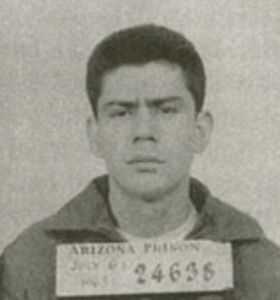

Original Intent and the Miranda Decision

|

| Ernesto Arturo Miranda |