6 Volumes

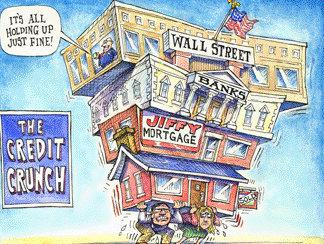

Recent Convulsions in World Finance

Few people choose to study economics; most people don't want to. But world economics have got in such a state that lots more of us had better give it some thought.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Philadelphia: Decline and Fall (1900-2060)

The world's richest industrial city in 1900, was defeated and dejected by 1950. Why? Digby Baltzell blamed it on the Quakers. Others blame the Erie Canal, and Andrew Jackson, or maybe Martin van Buren. Some say the city-county consolidation of 1858. Others blame the unions. We rather favor the decline of family business and the rise of the modern corporation in its place.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Worldwide Common Currency and Corporate Headquarters

The Death of Money

Whither, Federal Reserve? (2)After Our Crash

Whither, Federal Reserve? (2)

|

|

|

Foreground: Parliament Irks the Colonial Merchants

|

| Charles Townshend |

Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer under King George III in 1766-67, had a reputation for abrasively witty behavior, in addition to which he did carry a grudge against American colonial legislatures for circumventing his directives when earlier he had been in charge of Colonial Affairs. His most despised action against the Colonies, the Stamp Act, seems to have been only a small part of a political maneuver to frustrate an opposition vote of no confidence. The vote had taken the form of lowering the homeland land tax from four to three shillings (an action understood to be a vote of no confidence because it unbalanced the budget, which he then re-balanced by raising the money in the colonies.) The novelist Tobias Smollett subsequently produced a scathing depiction of Townshend's heedless arrogance in Humphry Clinker, but at least in the case of the Stamp Act, its sting was more in its heedlessness of the colonies than vengeance against them. One can easily imagine the loathing this rich dandy would inspire in sobersides like George Washington and John Adams. After Townshend was elevated in the British cabinet, almost anything became a possibility, but it was a fair guess he might continue to satisfy old scores with the colonies. When King George's mother began urging the young monarch to act like a real king, Townshend was available to help. On the other hand, the Whig party in Parliament had significant sympathy with the colonial position, as a spill-over from their main uproar about John Wilkes which need not concern us here. Vengefulness against the colonies was not widespread in the British government at the time, but colonists could easily believe any Ministry which appointed the likes of Townshend might well abuse power in other ways before such time as the King or a more civilized Ministry could arrive on the scene to set things right. It was vexing that a man so heedless as Townshend could also carry so many grudges. Things did ease when Townshend suddenly died of an "untended fever", in 1767.

Whatever the intent of those Townshend Acts, one clear message did stand out: paper money was forbidden in the colonies. Virginia Cavaliers might be more upset by the 1763 restraints on moving into the Ohio territories, and New England shippers might be most irritated by limits on manufactures in the colonies. But prohibiting paper money seriously damaged all colonial trade. Some merchants protested vigorously, some resorted to smuggling, and others, chiefly Robert Morris, devised clever workarounds for the problems which had been created. Paper currency might be vexingly easy to counterfeit, but it was safer to ship than gold coins. In dangerous ocean voyages, the underlying gold (which the paper money represents) remains in the vaults of the issuer even if the paper representing it is lost at sea. Theft becomes more complicated when money is transported by remittances or promissory notes, so a merchant like Morris would quickly recognize debt paper (essentially, remittance contracts acknowledging the existence of debt) as a way to circumvent such inconveniences. In a few months, we would be at war with England, where adversaries blocking each other's currency would be routine. By that time, Morris had perfected other systems of coping with the money problem. In simplified form, a shipload of flour would be sent abroad and sold, the proceeds of which were then used to buy gunpowder for a return voyage; as long as the two transactions were combined, actual paper money was not needed. Another feature is more sophisticated; by keeping this trade going, short-term loans for one leg of the trip could be transformed into long-term loans for many voyages. Long-term loans pay higher rates of interest than short-term loans; it would nowadays be referred to as "riding the yield curve." This system is currently in wide use for globalized trade, and Lehman Brothers were the main banker for it in 2008. And as a final strategy, having half the round-trip voyage transport innocent cargoes, the merchant could increase personal profits legitimately, while cloaking the existence of the underlying gun running on the opposite leg of the voyage. If the ship is sunk, it can then be difficult to say whether the loss of such a ship was military or commercial, insurable or uninsurable. In the case of a tobacco cargo, the value at the time of departure might well be different from the value later. Robert Morris became known as a genius in this sort of trade manipulation, and later his enemies were never able to prove it was illegal. Ultimately, a ship captain always has the option of moving his cargo to a different port.

Other colonists surely responded to a shortage of currency in similar resourceful ways, including barter and the Quaker system of maintaining individual account books on both sides of the transaction, and "squaring up" the balances later but eliminating many transaction steps. Wooden chairs were also a common substitute as a medium of exchange. But "Old Square-toes," Thomas Willing, experienced in currency difficulties, and his bold, reckless younger partner Morris displayed the greatest readiness to respond to opportunity. Credit and short-term paper were fundamental promises to repay at a certain time, commonly with a front-end discount taking the place of interest payment. The amount of discount varied with the risk, both of disruption by the authorities, and the risk of default by the debtor. This discount system was rough and approximate, but it served. Quite accustomed to borrowing through an intermediary, who would then be directed to repay some foreign creditor, Morris, and Willing added the innovation of issuing promissory notes and selling the contract itself to the public at a profit. Thus, written contracts would effectively serve as money. A cargo of flour or tobacco represented value, but that value need only be transformed into cash when it was safe and convenient to do so.

The Morris-Willing team had already displayed its inventiveness by starting a maritime insurance company, thereby adding to their reputation for meeting extensive obligations; they established an outstanding credit rating. Although primarily in the shipping trade, the firm was also involved in trade with the Indians. There, they invented the entirely novel idea of selling their notes to the public, essentially becoming underwriters for the risk of the notes, quite like the way insurance underwriters assumed the risk of a ship sinking. Their reputation for ingenuity in working around obstacles was growing, as well as their credibility for prompt and reliable repayment. In modern parlance, they established an enviable "track record." A creditor is only interested in whether he will be repaid; satisfied with that, he doesn't care how rich or how poor you are. The profits from complex trading were regularly plowed back into the business; one observer estimated Robert Morris's cash assets at the start of the Revolution were no greater than those of a prosperous blacksmith. It didn't matter; he had credit.

In the event, this prohibition of colonial paper money did not last very long, so profits from it were not immense. But ideas had been tested which seemed to work. Today, transactions devised at Willing and Morris are variously known as commercial credit, financial underwriting, and casualty insurance. In 1776, Robert Morris would be 42 years old.

The Revolution is Over, Every Man for Himself

|

| Charles Dickens |

A DOZEN episodes from American revolutionary times might be called pivotal, but a single debate in the Pennsylvania Legislature seems to have begun our political parties in their present form. Two debaters, their topic, and its consequences all rise to dramatic, even operatic, heights. In another place, we intend to explore the clashing philosophies of the Eighteenth century, with Hegel and Hume at the apex, but two quotations from Adam Smith are more intelligible. Charles Dickens nearly ran away with the topic in his novel A Tale of Two Cities, but Charles Brockton Brown and Hugh Henry Brackenridge were local authors, Pennsylvanians present at the scene. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson debated for decades about which of them was the main protagonist. But all of that is the background for one operatic scene at Independence Hall, where the real David and Goliath were William Findlay and Robert Morris.

|

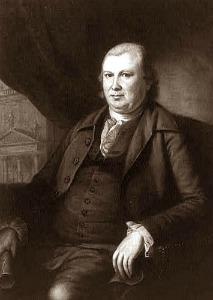

| Robert Morris |

Robert Morris, it must be remembered, was probably the richest man in America, a signer of the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution. He was one of three men, including Ben Franklin and George Washington, about whom it could be said: the Revolution could not have been won without them. Morris essentially invented American banking, founded the first bank, the Pennsylvania Bank, invented investment banking, corporate conglomerates, American maritime insurance, and dozens of financial innovations. His merchant house probably had 150 ships sunk by the enemy. George Washington lived in his house for years. Today, he is mostly remembered for going bankrupt at the end of a busy life.

|

| William Findlay |

William Findlay, on the other hand, was a Scotch-Irish frontiersman with a flamboyant white hat, elected by others like him from the Pittsburgh area to promote inflation through state-issued debt paper, so as to finance land speculation in the West. He had no education to speak of, no accomplishments to mention. He made no secret of his self-interest in land speculation, and therefore no secret of his opposition to rechartering the Bank of North America, which Morris had founded for the purpose of restraining inflation and speculation. Findlay wanted the bank to disappear, get out of his way, and he boldly denounced Morris for his self-interest in promoting a bank where he owned stock. He utterly denied that Morris had any motive other than the profit he would make for the bank, so in his opinion, they were equal in self-interest. Let's vote.

Prior to that time, Findlay had politically defeated Hugh Brackenridge, using the two strong arguments that Brackenridge had gone to Princeton, and written poetry; how could such a person possibly represent the hard-boiled self-interest of frontier constituents?

|

| Hugh Brackenridge |

Morris was positively apoplectic at this sneering at everything he stood for. As for the country's lack of trust in a man who had risked everything to save it, well, what has he done for us, lately? America had lately thrown off the King, but what it had really discarded was aristocracy. Every man was as good as every other man, and each had one vote. Under aristocratic ideals, a man was born, married and educated in a leadership class, expected to be utterly disinterested in his votes and actions, scrupulous to avoid any involvement in trade and commerce, where temptations of self-interest were abundant. Washington never accepted any salary for his years of service and even agonized for months when he was awarded stock in a canal company, wanting neither to seem ungrateful nor to make private profit. John Hancock, who came pretty close to having as much wealth as Morris, gave up his business when he was made Governor of Massachusetts. Benjamin Franklin was only accepted into public life when he retired from the printing business, to live the life of a gentleman. That's how it was, everywhere; every nation had a king and depended on rich aristocrats to supply the leadership for war and public life. But, now, America had become a republic where every man was equal. Morris and the Federalists he represented wanted to turn the clock back to an era that would never return.

Goaded too far, Morris impulsively resigned his business interests, to prove he had the nation's interest at heart in opposing inflation. It didn't help. Findlay won the vote, and the Bank of North America was closed. America was ashamed of how it behaved after the Revolution, but not ashamed enough to change.

REFERENCES

| Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution: Robert Morris: Charles Rappleye: ISBN-10: 1416570926 | Amazon |

Tammany: Philadelphia's Gift to New York

|

| Tammany Hall |

EDWARD Hicks painted a scene over and over, depicting William Penn signing a treaty of peace with the Lenape Indians at Shackamaxon ( a little Delaware waterfront park at Beach Street and E. Columbia Ave.). This scene was apparently a reference to a larger and more finished depiction by Benjamin West. The Indian chief in the painting is Tamarind, chief of the Delaware tribe. Long before Hicks got the idea for the picture from Benjamin West, Tamarind was locally famous for having the annual celebrations of the Sons of St. Tammany named after him. These outings centered on the joys of local firewater and thus may have had something to do with the evolutions of the Mummers Parade. George Washington presided over a lively Tammany party at Valley Forge, and local Tammany Hall clubs sprang up all over the country. The most famous offshoot had its headquarters on 14th Street in New York, as a club within the local Democrat party asserting Irish dominance over New York politics, allegedly using Catholic Church connections to control other immigrant groups. The identity of Tammerend seems to have got thoroughly mixed up along the way; the famous statue of "Tecumseh" at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, much revered by the cadets, is actually a depiction of Tammany.

|

| Penn's Treaty With the Indians By Benjamin West |

At earlier times, Tammany was the vehicle Aaron Burr used to assert control of the now-Democrat Party, particularly in the contested Presidential election of 1804. Shooting Alexander Hamilton in a duel, along with disgrace and impeachment as Vice President necessitated Burr's rapid conversion into a non-person, both in New York and in Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, the uproar led to the dispersion of Tammany influence, while in New York other bosses, particularly Boss Tweed, took over the organization and consolidated its role as a small club which dominated a larger political party, which in turn pretty well took over the government of New York City, which in turn dominated the governance of New York State, and even occasionally leveraged itself into national politics. Eventually, Tammany fragmented sufficiently that Mayor Fiorello La Guardia was able to dislodge it from control, which in time led to its dissolution. In a larger sense, however, the decline of New York's Tammany Hall began when in the late 19th Century it adopted the Philadelphia system of consolidating graft from local leaders into unified "donations" from local utilities. That greatly improved the efficiency of collections and disbursements but undermined the need for an effective local organization of ward leaders.

|

| Aaron Burr |

So, although Tammany was originally a Philadelphia creation perfected by New York, it continued to have connections to Aaron Burr in early days, and Philadelphia machine politics later on. But of course for seventy-five years, around here it seemed Republican.

Morris Defends Banks From the Bank-Haters

|

| Robert Morris |

IN 1783 the Revolution was over, in 1787 the Constitution was written, but the new nation would not launch its new system of government until 1790. It was a fragile time and a chaotic one. Earlier, just after the British abandoned their wartime occupation of Philadelphia in 1778, Robert Morris had been given emergency economic powers in the national government, whereas the state legislatures were struggling to create their own models of governance, often in overlapping areas. While the Pennsylvania Legislature was still occupying the Pennsylvania State House (now called Independence Hall) in 1778, it -- the state legislature -- issued the charter for America's first true bank the Bank of North America, and in 1784 the charter came up for its first post-war renewal. Morris was a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly both times. Although he was not a notable orator, it was said of him that he seldom lost an argument he seriously wanted to win. Keeping that up for several years in a small closed room will, unfortunately, make you many enemies.

|

| Tavern and Bank |

Morris was deeply invested in the bank, in many senses. He had watched with dismay as the Legislature squandered and mismanaged the meager funds of the rebellion, issuing promissory notes with abandon and no clear sense of how to repay them, or how to match revenues with expenditures. There was rioting in the streets of Philadelphia, very nearly extinguishing the lives of Morris and other leaders, just a block from City Tavern. Inflation immediately followed, resulting in high prices and shortages as the farmers refused to accept the flimsy currency under terms of price controls. Every possible rule of careful management was ignored and promptly matched with a vivid example of what results to expect next. Acting only on his gut instincts, Robert Morris stepped forward and offered to create a private currency, backed by his personal guarantee that the Morris notes would be paid. The crisis abated somewhat, giving Morris time to devise The Pennsylvania Bank, and then after some revision the first modern bank, the Bank of North America. The BNA sold stock to some wealthy backers of which Marris himself was the largest investor, to act as last-resort capital. It then started taking deposits, making loans, and acting as a modern bank. Without making much of a point of it at the time, the Bank interjected a vital change in the rules. Instead of Congress issuing the loans and setting the interest rates as it pleased, a commercial bank of this sort confines its loans to a fraction or multiple of its deposits, and its interest rates are then set by the public through the operation of supply and demand. The difference between what the Legislatures had been doing and what a commercial bank does, lies in who sets the interest rates and who limits the loans. The Legislature had been acting as if it had the divine right of Kings; the new system treated the government like any other borrower. As it turned out, the government didn't like the new system and has never liked it since then. Today, the present system has evolved a complicated apparatus at its top called the Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, most of whose members are politically appointed. Several members of the House Banking Committee are even now quite vocal in their C-span denunciations of the seven members of the Open Market Committee who in rotation are elected by the commercial banks of their regions. Close your eyes and the scene becomes the same; agents of the government feel they have a right to control the rules for government borrowing, while agents of the marketplace remain certain governments will always cheat if you don't stop them. This situation has not changed in two hundred years and essentially explains why some people hate banks.

|

| Seigniorage |

That's the real essence of Morris's new idea of a bank; other advantages appeared as it operated. The law of large numbers smooths out the volatility of deposits and permits long-term loans based on short term deposits. Long-term deposits command higher loan prices than short-term ones can; higher profits result for the bank. And a highly counter-intuitive fact emerges, that making a loan effectively creates money; both the depositor and the borrower consider they own it at the same time. And finally, there is what is called seigniorage. Paper money (gold and silver "certificates") deteriorates and gets lost; the gold or silver backing it remains safe in the bank's vault, where it can be used a second time, or even many times.

For four days, Morris stood as a witness, hammering these truisms on the witless Western Pennsylvania legislators. At the end of it, scarcely one of them changed his vote, and the bank's charter was lost. But at the next election, the Federalists were swept back into the majority, defeating the opponents of the bank. Although, as we learn the way democracy works, still leaving them unconvinced of what they do not want to believe.

Funding the National Debt

|

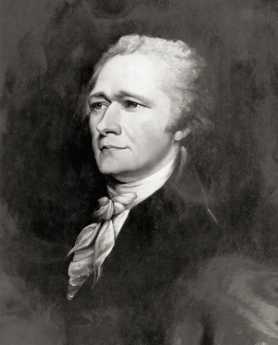

| Alexander Hamilton |

Although Alexander Hamilton's arresting slogan that "A national debt is a national treasure" has diverted attention to the underlying idea toward him, Robert Morris had introduced and argued for the same insight in the preamble to his 1785 "Statement of Accounts". The key sentence was, "The payment of debts may indeed be expensive, but it is infinitely more expensive to withhold payment." This fatherly-sounding advice was surely a distillation of a long life as a merchant, and the gist of it may have been passed down to him as an apprentice. Failure to pay your debts promptly and cheerfully results in the world assigning a higher interest rate to your future credit; it is not long before compounded interest begins to drag you down. It doesn't exactly say that, but that's what it means.

|

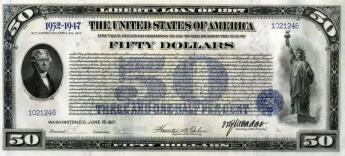

| Liberty Bond |

Another way of looking at this folk wisdom is that it leads to a simplified method of organizing the finances of an organization. Because higher rates of interest are demanded of long-term borrowing than short-term, it becomes efficient to segregate them. That is, to establish a cash account for every-day transactions, and a separate bond account for a long term, or capital, debt. As bills arrive, they need only be verified for accuracy and sent for payment from either a cash account or a capital account. The original responsibility for agreeing to such debts lies with top management, not the treasurer. The job of the treasurer's office is to pay legitimate bills as quickly and cheerfully as possible, ignoring any imprudence of earlier agreeing to them; rewards will come from lower interest charges and improved credit rating. An unexpected benefit of thus organizing institutions and governments is to make the accounting profession possible. Accountants perform the same function in every business, whether the business is selling battleships or parsnips. The accounting profession made itself computer-ready, two hundred years before the computer was invented.

|

| Robert Morris |

In the same document, the retiring national Financier was advising the wisdom of "funding" the war debts, which were largely owed to France, with whom relations were rapidly souring. Lump them all together into a fund, issue bonds and sell them as representations of the nation's capital at the time of issue. Disregard what the money was used for, by either the debtor or the creditor. In spite of appearances, money sequestered in a fund for later payment belongs to the creditor the moment it is promised, not the moment it is transferred. Morris and Hamilton discovered that the fund itself had the property of a bank, in creating money. As long as the creditor did not cash your bonds, he could use them as money, in effect doubling the amount of money you yourself can spend. It was this discovery which so exhilarated Alexander Hamilton, causing him to over-praise the methodology to an already suspicious Congress. Tending toward the teachings of Shakespeare's Polonius, Hamilton's excitable manner caused them to remember, neither a borrower nor a lender is. But Congress was eventually persuaded. The federal government lumped the states' debts together in an "assumption of debts" , consolidated all these various little debts into a single "funded debt", and made the deal work with changing the "residency" of the nation's capital from Philadelphia to the banks of the Potomac. It was called the Great Compromise of 1790.

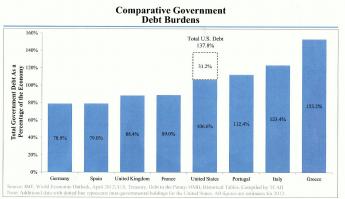

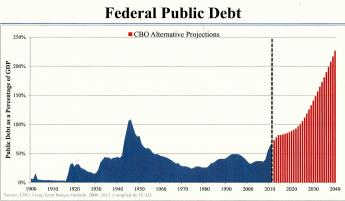

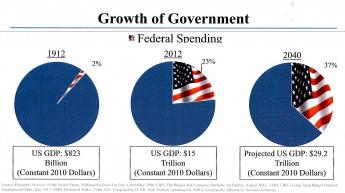

Morris well understood that a funded system requires some final payor of last resort. Such a payor need set aside only a small portion of the debt for dire contingencies, but his name gets first attention on the list presented to prospective creditors. In 1778 Morris had offered his own personal wealth as that last resort, which the public at the time trusted far more than the Treasury of the United States. Over the next twenty years, he came to realize that the last resort of established nations, no matter what the paper said, was the aggregate underlying wealth of the whole nation. With a vast continent stretching to the West, and countless immigrants clamoring to join from the East, the wealth supporting the debt of the United States in 1790 seemed endless. After two hundred years we have finally begun to accumulate a national debt which equals our Gross Domestic Product, and have only begun to pull back as we observe what happens to other nations who got to that point sooner. Let's hope devising an automatic check and balance does not require a second Robert Morris. Men like him can be hard to find, so limit your debts -- or your nation's debts -- to sixty percent of your assets. Financial geniuses are invited to devise a better debt limit, if they can.

Morris at the Constitutional Convention

|

| Constitutional Convention 1787 |

TRUE, George Washington was the presiding officer of the Constitutional Convention. But Pennsylvania was the host delegation, so the role of presiding host should have fallen to Benjamin Franklin, the President of Pennsylvania. However, Franklin was getting elderly and turned the job over to Robert Morris, who among other things was rich enough to host some necessary parties. The rules of decorum at that time thus kept Washington and Morris out of the floor debates. The proceedings were, in any event, kept the secret, so occasional frowns or encouraging smiles are not recorded for history.

But Morris had been an active debater in the Assembly and other meetings, so he knew enough to line up a consensus in advance for the matters he thought were essential. Obviously, Morris was strongly in favor of giving the national government power to levy taxes for defense purposes, and Washington whose troops had suffered severely from the inability of the Continental Congress to pay them also regarded this taxing power as the central reason for changing the rules. By making it the central argument for holding the convention at all, Washington, Franklin, and Morris had made taxation power a foregone conclusion. And by giving them what they wanted from the outset, the rest of the convention was in a position to do almost anything else it wanted without open comment from the Titans. The sense of this trade-off was captured by Gouverneur Morris, the editor of the Constitution, in Article I, Section 8:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts, and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;This formulation had the effect of greatly empowering James Madison, the only participant who had studied the inside details intensively and cared about every comma. It also encourages the military to believe that federal taxation was mainly their entitlement, whereas those whose main goals are defined as "the general Welfare" tend to regard defense spending as an unnecessary deduction from their share.

|

| Pawn Broker Sign |

Most of the convention delegates had experience with state legislatures, and Franklin and Morris had spent decades struggling with the weaknesses of legislators. A wink or a quip in a tavern was as good as an hour's speech for reminding the delegates what they already knew about human nature. What was designed as a dual system of powers of taxation, with federal oversight of balanced state budgets combined with federal power to tax on its own in emergencies or unforeseen situations. Since the members of the first few congresses after 1789 were largely the same people as the members of the constitutional convention, many details of this balance were worked out over a few following years. State powers to tax and borrow were tightly constrained, only the federal government could tax and borrow without limit. Since government borrowing is merely the power to defer taxes until later, the borrower of last resort was the U.S. Congress, alone empowered to encumber the wealth of the whole nation in a federal pawn shop window called the funded National Debt. For almost two centuries, this pawn shop window seemed able to support any imaginable expense. Today, we monitor this as the ratio of national debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and we now have a clearer idea what level of that ratio flirts with hopeless inability to pay the federal government's debt. The experts say it's close to a 60% ratio, and unfortunately, almost every nation on earth now exceeds that limit. The system continues to lack an unchallenged definition of its limit, but the system is nevertheless still Morris's system, wrapped in a mountain of descriptive detail by Alexander Hamilton. If a nation borrows more than that and clearly will never repay it, that nation is to some degree a slave to its creditors, with war its only hope if creditors are unrelenting. Perhaps another way to refine the thought is to say that if the nation wishes to mortgage everything it owns down to the last shoe button, the creditors will only accept additional debt if it is proposed by someone with the power to pawn the last shoe button. To foreigners, the proof of who has what power is much more certain if written down. Morris's protege Alexander Hamilton went even further: "credit" is established when creditors can see that somebody is in the habit of getting the nation's bills paid, and "credit" is injured whenever anyone in charge, welches.

What Is the Purpose of a National Constitution?

|

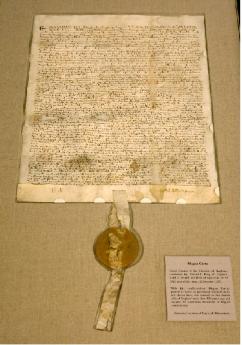

| 13th Century Magna Carta |

NATIONAL constitutions are mainly an outgrowth of the 18th Century Enlightenment, even though similar features are to be found among ancient legal codes. Those who trace the origins of the American constitution to the 13th Century Magna Carta will usually point to a central sentence of clause 39:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

|

| American Constitution |

That's a pretty good beginning, a good example of a needed legal principle, but unrecognizable as what we would today call a Constitution. It states what a government may not do, but does not define the nature of a government which does the job best. Nor do even the many Enlightenment philosophers of government take that final step of outlining where their notions should take us until the American Constitution had been written and defended in the Federalist papers. Nowhere among the writings of Montesquieu (The Spirit of the Laws, 1748), Catherine the Great (Nakaz, Instructions to the All-Russian Legislative Commission, 1767), Diderot (Observations About Nakaz, 1774), James Madison (1787), John Dickinson(1763) or Gouverneur Morris(1787) can there be found much tightly described definition of a constitution. Certainly, there is no definition within the writings of Adam Smith if we look for rule-making among Enlightenment thinkers whose ideas were influential on the 1787 Philadelphia document. The American constitution was the product of many minds, before and after 1787. The outlines of its final form converged, and emerged, from the Constitutional Convention of the summer of 1787, with Gouverneur Morris as the penman of record. To him, we certainly owe its succinctness, which is the main source of affection for the document. That probably understates matters; in his diary of the secret meetings, James Madison records that Gouverneur Morris rose to speak about 170 times, more than any other delegate. Lots of thought and debate; ultimately, few words.

The Elizabethan Sir Francis Bacon has the greatest claim on devising a theory of law and law-making in the Anglosphere tradition. But his elegant modification of Galileo's scientific method, the English Common Law, is more a methodology for creating good laws than an outline of a nation's legal principles. Anyway, tracing the American Constitution back to an underlying British one tends to stumble when the British Constitution fails to meet a definition which would include our own. The British Constitution is said to be "unwritten" to the degree it is a consensus of revered documents. It can be amended by Parliament at will, has a variable history of defining just who is covered by it, and in order to define constitutional principles seems to rely on sentences extracted from difficult context. If the two constitutions had been written and compared at the same time, one would say the British had sacrificed coherence out of respect for tradition. In fairness, some features of the American constitution are also perhaps unnecessary for every constitution, but by surviving as the oldest constitution of the modern form, have become its model. That would be:

A set of principles governing the legitimacy of a nation's laws, and firmly standing above them. It defines its own domain, geographically and by the membership of a defined citizenry. Except as otherwise defined, it supersedes all other governance within its domain. It defines and defends its own origins. It includes a description of how to amend it, which is intentionally infrequent and difficult. It goes on to outline the structure of the laws it regulates, with subtle modifications made to channel the type of power structure which will govern.

In the American case, history and culture generated several other instabilities so central they justified heightening the difficulty to amend them to a Constitutional level, thus conferring undisputed dominance over competing principles of governance. That would be:

A separation of government powers weakened all potentially offending branches of government, and thus enhanced citizen liberty. Separation of church from state, for like purpose. A right of citizens to bear arms, to strengthen citizens' defense against internal or external attack, and perhaps also warning that revolt must be possible, even endorsed, as some final extremity of protection for citizen sovereignty.

|

| Russia's Catherine the Great |

It enhances our comprehension to contrast the outcomes of competing 18th Century implementations of the Constitution idea. Russia's Catherine the Great proposed a constitution steeped in the traditions of the Enlightenment but ultimately designed to define and strengthen the role of the monarch. Denis Diderot her French protege recoiled at this viewpoint, substituting other views resembling those of Jean Jacob Rousseau. He opened Observations About Nakaz his commentary to the Queen, with the following declaration:

There is no true sovereign except the nation; there can be no true legislator except the people. Whether looking back to the English Civil War or forward to future disputes between the Executive and Legislative branches, it makes clear the Legislative branch was dominant, with the Executive branch acting as its agent.

|

| Denis Diderot |

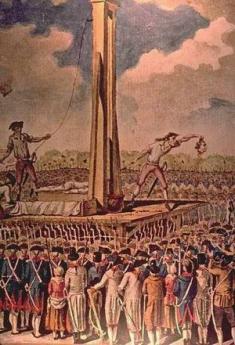

With this ringing warcry, the French model nevertheless ushered in the extremes of the Terror, the Guillotine, and the Napoleonic conquests. The consequences of the French constitution undermined world confidence in the benevolence of public opinion, at least deeply confounding those for whom the democratic rule was not totally discredited. Once more new life was breathed into allegiance for the monarchy, military rule, and dictatorship. Public opinion, it seemed, was not either invariably benign or comfortably far-seeing. The noble savage, mankind naked of tainted civilization, was not necessarily wise or worthy of trust. Edward Gibbons, the 1776 author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was pointing out where it all might lead if we completely believed in the collective goodness of the human condition. At the least, the failure of the French Revolution complimented the viewpoint of the Scottish philosopher, Adam Smith, who also in 1776 emphatically urged a switch in that reliance toward a sense of enlightened self-interest, as follows:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we can expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest.

|

| Terror, the Guillotine, |

It is not surprising that Diderot rejected the Leibniz view of things that "All is for the best, in this best of all possible worlds." And, in view of his dependence on Catherine, not surprising he did not publish his rejection of it until 1823. Thomas Jefferson was in France as ambassador during the time of the American Constitutional Convention, fearing to confront George Washington; and likewise keeping his conflicting views private for several years. Eventually, they surfaced in the creation of an anti-Federalist political party along with the conflicts which kept the new nation in a turmoil for the following forty years. It is surely a testimony to the strength of the Constitution's design that the country was able to shift between such extreme governing philosophies but still hold together without changing the governing statement of purpose. Indeed, it is plausible to contend that our two political parties still continuously debate the useful tension between these two differing opinions.

Constitutionality of the Monetary System

|

| The Constitution |

In noting that our Constitution has lasted for over two centuries, we assert that this simple short document has largely anticipated everything important to anticipate, including the Industrial Revolution, atomic warfare, and the Information Age, to name a few. When an occasional issue arises that is not only unmentioned in the Constitution but where no one is certain what to do, our system leaves us spiritually adrift. Such an issue is found in o0ur monetary system, where we have been wandering for two hundred years.

The founding fathers worried a great deal that popular majorities would abuse minorities, particularly in the case of the majority poor people voting themselves the property of minority rich ones, or that debtors in the majority might dishonor the rights of creditors. Although we have developed a welter of laws about debt and creditors, bankruptcy and taxation, they are if anything too specific. What is lacking is a few general words in the Constitution about the principles of credit and money. The problem now is the same as it was in 1787; we don't know what to say.

|

| Albert Gallatin |

For a very long time, some very well educated people were strongly opposed to the creation of a bank, later to mean a banking system. Alexander Hamilton's proposition that a "national debt is a national treasure" was greeted with horror by several Presidents, as well as by Albert Gallatin, one of the most sophisticated financial thinkers of the time. Underlying this perplexing reaction to the simple proposal to create a bank was surely the perception that making the Federal Government into a substantial debtor creates a powerful ally to all debtors in their eternal struggle with all creditors; the outcome of such an unequal struggle would inevitably be to the disadvantage of creditors. In common parlance, the word capitalist seems to imply a creditor. It took a very long time for it to become understandable that debtors, too, were essential beneficiaries of a capitalist system, but that idea still often meets with dissent. However, when millions of the world population belong to religions which prohibit the payment of interest, it should not be surprising to find many Americans who cannot get their heads around the idea that debtors and creditors need each other to an equal degree.

In the case of inflation, governments have always been somewhat favorable to debauching the currency. Naturally, a major debtor hopes to repay its debt with cheaper money. Since it has more or less always been necessary to use police powers to maintain a common currency, Kings and governments have long been in control of money, whether that means gold bars or beaded wampum. And for the same length of time, governments have been discovered bending the rules in favor of themselves. Bronze has been substituted for gold, the edges of coins have been shaved, the printing presses print paper money unrestrainedly, and the consumer price index has been manipulated to encourage inflation. Political parties have sought votes from debtors by promising to regulate banks, promote silver as a substitute for gold, disadvantage foreign competitors, inhibit or manipulate the value of the currency on foreign exchanges.

|

| Alan Greenspan |

For forty years we have operated without any fixed standard for money. Money for all that time has lacked any physical representation or discipline. Money has become a computer notation. At first, it was based on calculations of monetary aggregates, a bewildering concept promoted by Milton Friedman. More recently, it is entirely based on inflation targeting as promoted by Alan Greenspan. With a target of maintaining steady prices, an inflation rate of 2% is set as a specific target for the Federal Reserve. If inflation falls below that target, more money is created; if it rises above that level, less money is created. How much there is of it does not matter; it's beyond calculation. Although this simplified description fills almost any listener with doubts, it seemed vindicated by seventeen years without a notable recession. Even though events beginning in 2007 raise pretty serious doubts, it may still prove to be the best possible monetary system.

Even though this most fundamental of all commercial issues cry out for a simple principle to be stated in the Constitution so that neither populist congressmen not rapacious financiers can ruin us, it is not presently possible even to imagine what a new Constitutional amendment would, should or even could say. Meanwhile, some immense power rests in the hands of shadowy figures whom we blindly trust, for lack of a better idea about how we should select them or what we should instruct them to do.

Causes of the 2007 Crash: Political and Technological

Dealing with a topic as complicated as the causes of the 2007 financial crisis, it's quite possible for two viewpoints to be entirely in agreement, until abruptly coming to different conclusions. In this paper, we consider the relative merits of blaming government housing subsidies in various forms, relative to blaming the unanticipated effects of the computer revolution. The subsidy argument has just been succinctly and effectively argued by a lawyer, Peter J. Wallison. Agreeing with every word he writes, I nevertheless hold the perspective that the disruptive effects of the computer revolution were equally responsible, if not more so. Politics versus technology, choose your poison.

|

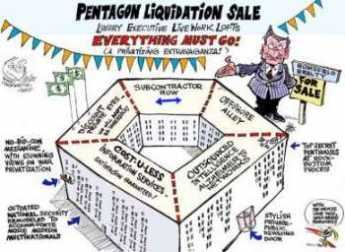

| Federal Reserve |

Mr. Wallison served as a lawyer in the financial loins of Washington, and thus has the perspective of a Reaganite who sees government as the main problem; with the significant distinction that his proposals for solution also lie in government corrective action, particularly "covered bonds" and step-wise privatization of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). While agreeing with both reform proposals, my concern here is about too little general recognition in the analysis of how vulnerable the banking system has become, to revolutions made possible by even primitive computers of the 1960s. Such revolutions soon grew many times magnified by the inexpensive high-speed internet. If that analysis is correct, it predicts mere legislative action for the housing industry will prove inadequate; banking has taken a radical new direction.

Mr. Wallison's argument in the January 3, 2011 edition of the Wall Street Journal is admirably succinct. He points out the New Deal Federal Reserve deliberately suppressed interest rates to the benefit of the housing industry, but made a significant exception for the Savings and Loans. (It was forced to abandon that approach by the innovation of money market funds, in turn, made feasible by the widespread adoption of the IBM 360 computer.) When the collapsed, that segment of the market was awarded to the GSEs (Fannie and Freddy Mac, insured by FHA). In 1992, Congress imposed the goal of promoting "affordable housing" on the GSEs, which is to say the subsidization of "subprime" (i.e. high risk) mortgages. By 2007, half of all mortgages were subprime, and by September 7, 2008, Fan and Fred were insolvent, effectively replaced by the Federal Reserve (i.e. the taxpayers) as the final guarantor against national insolvency. It will take a decade to restore the economy from its present setback, but Mr. Wallison's proposals do indeed have some chance of eventually leading to a viable economy. He proposes the threshold for "jumbo" mortgages be reduced by $50,000 every six months until mortgages are effectively privatized. And he also suggests we create a pool of mortgage assets as security for a bond issue, thus privatizing existing mortgages in the way Europeans describe as a "covered bond" system. Go ahead, do it; it might work, and nothing else is on offer.

|

| IBM 360 Computer |

Meanwhile take a look at banks; we seemingly can't get along without them. But other institutions are undermining them, with cheaper products made possible by computers. For two centuries, banks transformed short-term borrowing into long-term loans; no one else could do it. It's a simple idea, and it works, that a constant or even rising pool level can be maintained by a steady inflow of short-term deposits. But it is risky; the risk is that some event will precipitate a sudden rush of withdrawals, a run on the bank. Sooner or later, the law of averages catches up. The risk is real, it happens every few years. A price in the form of interest must be imposed to maintain reserves against occasional bank runs, and collectively the whole nation must maintain a central "bank", charging interest to maintain reserves against simultaneous runs on multiple banks. No device has ever been created for a nation to protect against a universal bank panic, which is as effective as placing the risk in the hands of private bankers who can expect to be stripped and shorn if things get out of control. Robert Morris demonstrated this point in 1779, and the nation seemingly must re-learn it every few decades. The IBM 360 computer made it possible to transform short-term into long-term in greater volume and lower cost by allowing banks to get bigger; but it could also perform the short-long transformation in cheaper ways than depository banks do, and from there the bank-competitive process we know as securitization has gone on to commercial credits, auto loans, credit cards, high-velocity stock trading, and mortgage-backed securities. These approaches are often cheaper and more convenient than the trusty old banking system and Credit Default Swaps show its power isn't exhausted; any legislation to prohibit CDS is sure to to be circumvented. Insurance is also on the edge of being threatened. An industrial revolution of this magnitude takes decades of tweaks to become stabilized, but it will suffice for now, if we can establish reasonable protections against the risk shifted into the securitization or investment banking arena. As risk shifts, remuneration for accepting risk must shift as well. This new system for generating capital must not be starved because depository bankers resist the loss of their share of profitability; politics will have much to answer for if that happens.

Most likely, the main obstacles to getting this system fixed will come from overseas. Fifty years of disillusionment with the United Nations will make nations, the United States chief among them, resist loss of sovereignty in something so vital as finance. But that's for the future. For nearly a century, the past has been disrupted by idle notions of the fairness of coerced redistribution, in ways Mr. Wallison has succinctly described. But meanwhile we almost willfully ignore technological upheavals which everyone welcomed but no one fully anticipated.

Black Swans (Financial Variety)

|

| Nicolas Baudin |

The mouth of the Delaware River once teemed with white swans, but black swans were unknown until the French explorer Nicolas Baudin brought home a few from Australia, where they are now celebrated as the state animal of Western Australia. Empress Josephine Bonaparte was delighted with them, made them known as her birds, and thus made the term "Black Swan" more or less synonymous with rare chance occurrences. The implied inference that every white swan contains a remote potential for breeding a black one is doubtful biology, however. More likely, black swans are a distinct species -- Cygnus atratus-- confined to Australia and New Zealand, and just about extinct in New Zealand. In that view of things, the rarity of black swans is equivalent to the prevalence of black ones, mixed within the population of generally white ones. Nevertheless, for this article, it is convenient to continue the unlikely conjecture that most, or perhaps every, white swan contain a small potential to hatch a black one.

|

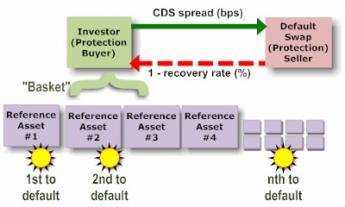

| Credit Default Swaps |

Many theories exist for the discovery that financial crises are commoner than chance alone would seem to predict; if they follow a Gaussian normal distribution curve, it must be somehow different from the distribution curve of smaller fluctuations. Observing this discordance is more or less how the phenomenon was discovered. The normal volatility of economic activity is calculated from the fluctuations observed in, say, twenty years. When that derived curve is extrapolated to include cataclysmic events which by a theory of the unmeasured "long tail" occur every hundred years, speculators have later discovered by actual measurement that, alas, such disasters actually occur much more frequently. Calculated risks derived from such extrapolations have upended many insurance companies and insurance-like vehicles like Credit Default Swaps, who set their premium charges to match the mathematics. Since CDS approached a hundred trillion dollars in the last crisis, it is important to understand the mechanics of this kind of Black Swan if we possibly can.

|

| Black Swan |

One way to do that is to question the conventional equivalence of risk and volatility ; that is, that the more markets bounce around, the riskier they become. Why should that be true, we might ask. And if it is somewhat true, why does that make it is converse true, those calm seas are safe ones? Those of us who sit and watch the ocean shore soon adopt the habit of speech that high waves at the shore mean a storm is approaching, not that it will ever arrive. After all, the center of the storm may be traveling parallel to the coastline, not directly toward it. And calm seas are particularly undependable predictors; no matter how calm it may be, the next storm might arrive in a few hours, or it may not come for months. Many other analogies spring up, once one puts aside the basic assumption that world economies can be depicted as a linear electrocardiogram. At the very least, they are two-dimensional, possibly three. Possibly four, if you regard time as a dimension.

|

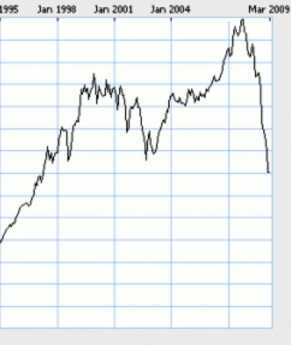

| Dow Jones |

It must be noticed that market volatility is universally viewed as linked to bad things, and many efforts have been made by central banks to reduce risk by constraining volatility. Alan Greenspan is famous for having controlled the economy for seventeen years without major depression. Is that necessarily a good thing? Is it equally possible that kinetic energy was constrained within the inflating balloon until the bursting of it was a far more damaging explosion than small planned deflations would have been?

Experimental testing of these ideas has itself been constrained by an inability to predict the explosion point of expanding financial balloons. Planned deflations have been particularly feared, because of lack of assured ways to get them to stop deflating. But practical warnings such as these are not the same as claiming that lack of volatility is always the ideal state.

Macroeconomics of The 2007 Collapse

Sudden wealth creation, whether from the discovery of gold or oil, the conversion of poverty into useful cheap labor, or the sudden abundance of cheap credit, is of course a good thing. Sudden wealth creation can be compared with a stone thrown into a pond, causing a splash, and ripples, but leaving a somewhat higher water level after things calm down. The globalization of trade and finance in the past fifty years has caused 150 such disturbances, mostly confined to a primitive developing country and its neighbors. Only the 2007 disruption has been large enough to upset the biggest economies. It remains to be seen whether a disorder to the whole world will result in a revised world monetary arrangement. One hopes so, but national currencies, tightly controlled by local governments, have been successful in the past in confining the damage. This time, the challenge is to breach the dikes somewhat, without letting destructive tidal waves sweep past them. Many will resist this idea, claiming instead it would be better to have higher dikes.

It is the suddenness of new wealth creation in a particular region which upsets existing currency arrangements. Large economies "float" their currencies in response to the fluxes of trade, smaller economies can be permitted to "peg" their currencies to larger ones, with only infrequent readjustments. Even the floating nations "cheat" a little, in response to the political needs of the governing party, or, to stimulate and depress their economies as locally thought best. All politicians in all countries, therefore, fear a strictly honest floating system, and their negotiations about revising the present system will surely be guilty of finding loopholes for each other; the search for flexible floating will, therefore, claim to seek an arrangement which is "workable".

In thousands of years of governments, they have invariably sought ways to substitute inflated currency for unpopular taxes. The heart of any international payment system is to find ways to resist local inflation strategies. Aside from using gunboats, only two methods have proven successful. The most time-honored is to link currencies to gold or other precious substances, which has the main handicap of inflexibility in response to economic fluctuations. After breaking the link to gold in 1971, central banks regulated the supply of national currency in response to national inflation, so-called "inflation targeting". It worked far better than many feared, apparently allowing twenty years without a recession. It remains to be investigated whether the substitution of foreign currency defeated the system, and therefore whether the system can be repaired by improving the precision of universal floating, or tightening the obedience to targets, or both. These mildest of measures involve a certain surrender of national sovereignty; stronger methods would require even more draconian external force. The worse it gets, the more likely it could be enforced only by military threat. Even the Roman Empire required gold and precious metals to enforce a world currency. The use of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) implies attempts to dominate the politics of the IMF. So it comes to the same thing: this crisis will have to get a lot worse, maybe with some rioting and revolutions, before we can expect anything more satisfactory than a rickety negotiated international arrangement, riddled with embarrassing "earmarks". Economic recovery will be slow and gradual unless this arrangement is better, or social upheavals worse, that would presently appear likely.

Securitization: Pass the Hot Potato

|

| Fannie Mae Corp. |

It would be pardonable to say that since securitization of home mortgages is a generally good thing, we might overlook any minor differences in approach between Fannie Mae (FNMA) and CDOs (Collateralized Debt Obligations), and let the customers decide which approach is preferred. Unfortunately, they both encompass a fatal flaw that has somehow escaped adequate notice. As mortgages pass from one holder to the next in sequence, both the buyer and seller seek to avoid the worst-risk mortgages and retain for themselves the best-risk ones. Get stuck with too many bad-risk properties, and you will go broke. When the credit markets suddenly woke up to this reality in August 2007, it was impossible to know who was holding good stuff and who was holding toxic mortgages. The markets "froze", which is to say most traders just walked away from participation until the situation clarified.

|

| Rising house prices |

Furthermore, with existing systems this seems to be something that will inevitably happen. A small-town bank tries to sell every mortgage it originates to an aggregator, but a few mortgages just aren't salable. The small town bank might well be able to sell mortgages to people who can't afford a house, but the aggregator is wise to the world, and won't buy the worst of them, so they silt up in the hands of the originating bank. Some originating banks may be deft enough to hold on to the very best risks and sell the rest, but a lot of banks will be turned away by dealers who are smarter than they are. At every step in the chain, there will be the same contest, so eventually, everybody comes under suspicion. Add to this trap the irony that an environment of rising house prices simply increases the size of the defaults when the pyramid finally topples, and it may temporarily blind everyone to the risks being run, thus making it all worse. Somehow or other, the average down payment on the mortgages you hold must be larger than the average drop of house prices in a slump, else you will be transferring the risk from the homeowner to yourself. A strong case can be made that the fault in the recent crash was not predatory lending; it was a failure to demand adequate down payments.

|

| Bear Stearns |

However you define an "adequate" down payment, it is clear that the recent rise of house prices particularly in the regions of greatest overbuilding, put a conventional 20% down payment completely out of reach of many first-home buyers. Since house prices have declined 20% and may decline 20% more, a determination of lenders not to lend more than 80% would have prevented a lot of overbuilding. If mortgage aggregators had refused to purchase mortgages that lacked an adequate down payment, the originating banks would soon have stopped issuing them. Consequently, the necessary fortitude should have been applied at the last step before securitization. It's possible to believe the people at Bear Stearns now wish they had done so.

If we then turn to the GSEs, the significant extra risk of Fannie Mae is political. Holding $5 trillion of debt more or less guaranteed by the U.S. Government, the Secretary of the Treasury repeatedly told congressional hearings that assuming its default would double the national debt. Double the national debt is what is meant by being "too big to be allowed to fail." Since this appalling situation willy-nilly relieves Fannie Mae of any worry about collapsing, the only way to force Fannie Mae to insist on adequate down payments is by Congress passing a law that they must. Congress seems to lack the political will to pass such rules in an election year, or probably any other year. The mandate for fifty years has been for Fannie Mae to make housing "affordable" and keep homeowners from losing their homes. It would be an unimaginable tragedy if Congress ran away from this dilemma, and accepted the hyper-inflation which would result from suddenly doubling the national debt. Unimaginable, but likely.

HowTo Create A Subprime Derivative

What's a Repo?

|

| Bear Stearns |

On St. Patrick's Day, 2008, Bear Stearns became insolvent and was given to J P Morgan. The Federal Reserve assumed all risks. Effectively, the fifth largest investment bank in America was nationalized for $2 a share, because no private bank would buy it at any price. A year earlier it was worth $170 a share, even one trading day earlier it sold for $26.

At the heart of this catastrophe were "repo's", or repurchase agreements. (They should not be confused with repossessions of cars and other hard goods bought on time, which are also called repo's.) Although most people had never heard of the high-finance version of repo's, the volume of these instruments had grown to $5 trillion by January 2005, presumably even several times larger than that when they caused the nationalization of Bear Stearns. Newsmedia accounts offered the guess that 16% of the resources of the whole financial sector were caught in open repo's when the music stopped. Repo's must be awfully good, or awfully bad.

|

| J.P. Morgan |

They were both of these things at once. Like so many innovations in the post-computer era, they offered a major cost saving to an inefficient transaction system but were so successful they overwhelmed the institutions which flocked to their reduced cost. The unanticipated difficulties might have been imagined, but they were not adequately guarded against. Essentially, these loans limited exposure to a few days, a feature that made them appear quite safe. Unfortunately, tons of these loans could expire simultaneously if a rumor got started and everyone held off using them for a week. With a run on a bank, at least people have to take action to withdraw their money; but with these things, simple inaction quickly led to massive cash shortages at the bank. Speeding up the loan process had made it cheaper, but made it vulnerable.

|

| Hedge Fund |

Consider the inefficient complexities of a bank loan. The bank wants collateral, perhaps 80% of the value of the loan. The ability of the borrower must be investigated, a clear title assured, and papers arranged for transfer in case of defaulted collateral. Lawyers must organize the agreements, and it all takes time, costs money. To go through all this for a one-week loan for anything less than huge transactions is simply not practical. So the idea was devised to sell the collateral to the lender at a discount, together with a repurchase agreement to buy it back at full price. For safety sake, the discount could be greater than the interest cost, and part of it returned if all went well. The collateral could be held by a third party, who essentially guaranteed the details while the collateral itself never moved. Bear Stearns had perfected these variations at such favorable prices they dominated the market for them with hedge funds; the margin for error narrowed when interest rates dropped, cash got scarce when investors got uncomfortable, the whole hedge fund industry was suddenly paralyzed, and everything connected to hedge funds was frozen secondarily. Much of this was handled automatically by computers, so huge volume made it impossible for anyone to know who might be insolvent. It seemed comparatively harmless to decline to play this game for a few days, but it was not harmless if most people decided to do so at the same time. The daily variations of interest rates and/or duration generate a ("Gaussian") normal distribution curve for the risk, predicting serious deviations will occur once every two centuries. But when events --even false rumors -- suddenly get everyone's attention at once, small daily fluctuations no longer bear much relationship to the frequency of violent fluctuations. Once-in-a-century events start to happen every few years. At those times, the public stops speaking with a million voices and shouts in unison. Quite often, there is no cataclysmic event to trigger it. Like the conversational babel of a dinner party, it can all stop at once for no particular reason.

|

| Black Swan |

The mathematics of this matter could be taught to a tenth-grade math class. It starts to get beyond everybody's anticipation however when two such Black Swan events happen at the same time. In this case, an unanticipated pause for a few days bumped into the rule that non-bank institutions must mark their portfolios to the market every day. But for days at a time in this crisis, there could be no trading in certain issues; there was no market to mark to. How then can you demonstrate your solvency -- what might your competitors be hiding during these unannounced market holidays? And, since banks are in the same pickle but aren't required to mark to market, how can you trust them to pay bills? When you see European banks, who must obey new rules called Basel II, go bankrupt and get nationalized, how can you be sure American banks, who needn't obey Basel II until 2009, are any safer bet?

Progress is progress, but how much of it can we cope with?

The 'repo' market from Marketplace on Vimeo.

Novation

|

| American Stock Market |

Novation is a term that perhaps nobody but a specialist expert can now define, but is nevertheless destined to be politicized in the coming election campaign to the point where almost everybody could be shouting it like a war cry. That is unless the hired political consultants decide some other feature of credit derivatives serves warcry purposes better. We're talking sixty trillion dollars here, about five times the size of the domestic American stock market.

Someone owned or thought he owned pieces of paper worth this staggering sum, which can be regarded as side bets on the bond market. Just as in a horse race, where you don't usually own the horse when you bet on the winner, you needn't own the bonds to bet on whether they will default. The side bet is often between two outsiders who acquired their bets through, well, novation. The process begins as a credit derivative, in which someone gets paid an annual sum in return for agreeing to pay off -- if the bond defaults. That could be regarded as a useful insurance policy, making more credit available by making it safer to buy bonds. The bondholder gives up a little interest in return for assurance the bond is now completely safe. Sucker.

|

| Sun Belt Mortgage |

Like the Sun Belt mortgage originator, the originators of these derivatives often wasted little time clipping off a fee and passing the carcass to someone else. And that process got repeated until the accumulating fees in the chain slowed the process to a point where the weakest or most reckless holder got into danger. The game might have slowed to the point where it became self-correcting, but what actually seems to have happened is that much of the long-term debt involved was financed by short-term borrowing, and the start of some rumors triggered a run on the bank. Not exactly, of course, but when institutions which had made one-week or one-month loans stopped lending, it only took a few days for the money to run out and Bear Stearns was quickly unable to pay its bills even though it started the week with $18 billion in reserves.

|

| Securities and Exchange Commission |

That short description is about the best that can be made out of an opaque situation, based on what the Securities and Exchange Commission is willing to tell reporters about its investigation. More will be forthcoming, and no doubt some villains and fools will emerge with a lot of blame. For example, the price of credit derivatives concerning Bear Stearns debt had been creeping up steadily during the month before the explosion; whether somebody knew something bad, or whether there really was something bad is presently unclear. It's disconcerting to learn that Goldman Sachs was dumping this paper, and JP Morgan Chase was mostly buying it, but it's early days for unfounded suspicions. More will come.

Now to return to novation. We legal novices learn that novation transfer is the same as assignment transfer, except all parties have to agree to novation before it can take place. That's going to make it harder for a lot of people to deny they knew what was happening. The astonishingly large sums involved are apparently not entirely real, because in some way the old debt is not extinguished, and the new debt is merely added to the sum total outstanding. That surely means the same debt is counted several times, and the apparent sum is to some unknowable extent much larger than the underlying reality. This also accounts for the amazing speed of growth. In January 2007 the total was said to be about $25 trillion, in January 2008 it was reported to be $42 trillion, and in May 2008 it was said to be $60 trillion. Things which move that fast can quickly spin out of control, especially when short term creditors need to do nothing much for a couple of weeks as their money emerges from the pool. Some people did sell short, of course, but whether that was panic or malicious must probably be left to politicians to declaim.

Surely the most terrifying part of this simple story is that so much money could be moved around without public awareness. When the $25 trillion figure emerged, a number of people asked what in the world was going on, and kept asking that question for eighteen months. Nobody knew nothing.

Steep Yield Curve: A Useful Subsidy?

The steepness of the federal interest rate curve -- ten-year treasury bonds pay more interest than three-month treasury bills, and the rate for intermediate time intervals slopes gradually from one to the other -- is a function of the Federal Reserve; the slope of this curve concisely describes current Fed policy. The Federal Reserve controls the money supply by raising or lowering short-term rates, which "affects the slope at the short end", and mainly in this way restrains or encourages inflation, or alters the exchange value of American currency. For the most part, long term rates are set by the public bond market. Once in a while, the Federal Reserve does buy or sell long-term treasury bonds to modify long-term rates in the economy. By affecting rates at either end, the result is some kind of change in the slope of the curve.

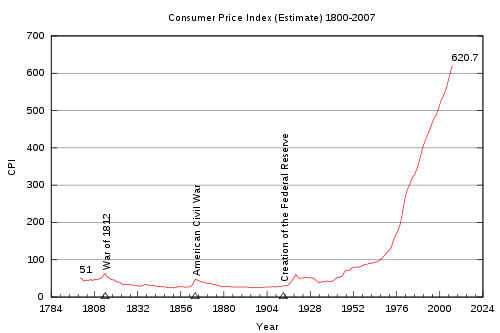

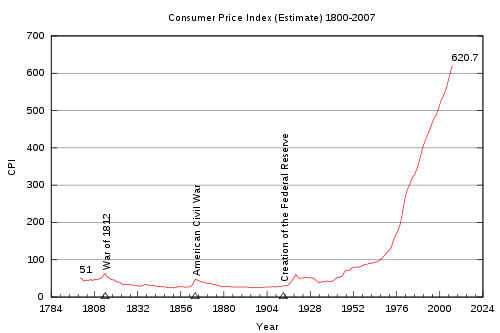

Because banks make interest payments to depositors near the short-term federal rate, while the same banks charge borrowers at near the public long-term rate, the current slope is the main determinant of bank profits. Banks borrow short and lend long. If Federal Reserve tinkering steepens the curve more than it would be without interference, then bank profits are subsidized. Of course, it works the other way as well; in a banking crisis, yield curves can be steepened to rescue banks from failure, thus potentially sacrificing ideal monetary levels temporarily. For the most part, what is good for the banks is good for the economy; but it remains that bank profits are subsidized much of the time. Artificially widened yield curves either punish savers by lowering interest rates on their savings accounts or else punish borrowers by increasing interest rates on mortgages and other credit. For political reasons, the pain is usually shared among voting blocs. It can be argued this invisible subsidy of banks by the public creates a compensating benefit of economic stability despite occasional bubbles and recessions like the present one. However, the Federal Reserve system has been in operation for almost a century, revealing a long-term bias in favor of inflation, which is a subsidy of debtors by creditors. Present policy deliberately targets a steady rate of 2-3% inflation; the gold market responded to a century of this by raising the price of gold from $17 to $900 an ounce. A 1913 penny has become a dollar (before taxes) you might say. You might also say it took the Federal Reserve less than a century to make the present dollar worth a penny.

If gradual inflation is a consequence, a fair question must arise whether the Federal Reserve is worth its cost. Compared with an inflexible, relentlessly deflationary Gold Standard, yes, it is. Even accepting the monetary crisis as partly created by central banking, the international dominance of the American economy and recent smoothing of banking instability testify to the durable use of the Fed. But another criticism must be faced: In subsidizing depository banks with an artificial yield curve, is the Fed backing the wrong horse for the future? To answer that question, examine two components: With computer technology rapidly advancing, can the Federal Reserve accommodate non-banking competitors to banks? And secondly, international central banking appropriately accommodate globalization? There are, after all, aspects within the 2007-20?? a crisis which suggests -- maybe it can't.

Steady inflation of 1000% per century may well be preferable to 19th Century volatility of 1000% every ten or so years. But a gradual rise of, say, 500% or less each century might be even better. Relentless political pressure on the Federal Reserve has typically been used to explain its slow retreat from truly stable prices, and this defense takes the form of mentioning its dual mission of minimizing unemployment while holding prices as steady as possible. In recent years, European political rhetoric goes further, aspiring to add the right to employment to their fifty-page Bill of Rights; similar utopianism has crept into our own news media. Governments for thousands of years have cheapened their currencies. But while the drift is clear, our own pace is set by the amount of subsidy required to maintain a steep yield curve. As retail banks have struggled to compete with the wholesale investment banks, their increasingly uncompetitive costs require a greater subsidy from the yield curve. It is always going to be more expensive to aggregate deposits for lending purposes than to raise large sums by floating a bond issue. Securitization is here to stay because retail banks have consolidated and savings banks have gone out of business by the thousands; the mortgage industry can no longer survive without substantial amounts of mortgage-backed securities. Nor should it; securitization is a sensible route for importing capital from nations with a trade surplus. Depository banks long ago lost the borrowing business of corporations large enough to float their own bonds; securitization provides a means for smaller borrowers to share the same efficiency. After it has tried everything else, Congress will eventually devise a reasonable regulatory system for derivatives. Except for smoothing the transition to whatever proportion of market share the investment banks can justify, perhaps all of it, the subsidized yield curve impairs efficiency. It would be a mistake to allow some foreign nation to exploit such an opening before we do. The technical problem for all central banks is to devise a suitable alternative method of controlling the currency, other than by targeting inflation with adjustments in interbank lending rates.

Observers led by Martin Wolfe the economist for the Financial Times feel the 2007-20?? financial crisis can be adequately explained by Chinese pegging their currency too low, and could be rectified by persuading the Chinese to float their currency. Regardless of this extreme view, globalization is clearly both a good thing and an inevitable one. Thus some form of discipline must be devised to prevent central banks from destabilizing it for their own advantage. Wolfe proposes the use of a strengthened International Monetary Fund, which is unfortunately apt to project international politics into a process which could be harmed by it. An alternative to be examined might be to pool sovereign wealth funds as a pooled currency reserve, although this system probably could not withstand present extremes between surplus and debtor nations, so getting world acceptance could be protracted. Ultimately, everyone realizes that the real backing for an international finance system is the net worth of the whole world. But the example of Lloyd's of London is a haunting one; no one relishes putting absolutely everything at risk, down to the last shoe button. In the event of a disaster, everyone wishes to hold back some nest egg to use for recovery. Because of the same line of thinking, almost no one would trust foreigners to control more than a limited share of their future.

The future of international monetary relations is thus quite murky, but current pressures would seem to be driving something fundamental to change. When it does, regulating artificially manipulated yield curves had better be kept in mind.

The Cause of the Subprime Crisis

How Should We Reform Real Estate Finance?(1)