Related Topics

Whither, Federal Reserve? (2)After Our Crash

Whither, Federal Reserve? (2)

TARP Demands But Does Not Create a New Standard of Fair Value

|

| Grandfather & Grandson |

Grandfathers tell their wide-eyed offspring that a thing, anything, is only worth what you can sell it for. Not necessarily what you paid for it, or what it cost to make, or what it may be worth in the future. That thing whatever it is worth what you and someone else agree to exchange it for, right now. Our economy depends on the idea that one person would rather have the object, the other person would rather have the money, and when they agree on the exchange of the money for the object, both parties walk away feeling better off. Multiply these little improvements millions of times, and the economy constantly grows richer, just by exchanging.

|

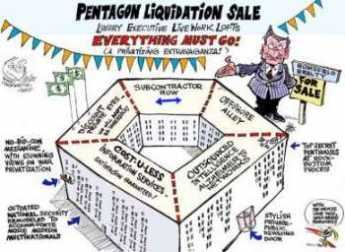

| Fire Sale |

Now, any seller has an option to refuse an offer, waiting for a higher price. This time option is essential to the wealth idea underlying trade; if you simply must have the money before a satisfactory offer appears, you will surely sacrifice some money on the trade. Maybe your counterparty makes a little more money but between you two, wealth is generally not created by fire sales. By definition, you sold before you got a fair offer, so wealth may even have been destroyed and at best the other person's gain just equals your loss. So, everyone is enjoined to conduct business and affairs in a way that makes it possible to wait to trade until a fair offer does appear, but even that maneuver is not as satisfactory as an immediate fair trade.

In the frozen markets of 2008, trade is coming to a halt because so many people are holding off on sales; wealth is definitely being destroyed in the process. Government intervention is proposed as a method to assign a fair price and make trades. The process is generally that the government will offer to buy these frozen securities, hoping to hit fair value precisely and hoping both sellers and buyers will accept that price. Since the government agents are spending other people's money, they will likely overpay and must lean against that tendency.

If the government pays too little, buys the securities and then resells them at a higher more nearly fair value, the government will make a profit, but the seller suffers. That's really not the intention at all. Skinning the seller is not desirable because wealth is destroyed in the process; keep it up and a recession will result. On the other hand, if the government pays too much, it will eventually lose money. The world economy will suffer from any outcome other than striking just the right price. Therefore, the government insists on receiving a warrant against the common stock of the seller who made an unearned profit, so the profit returns to the government. If there is no profit, the warrants are worthless, so they can be seen as a harmless disincentive against overpayment. In 1991, a similar credit bubble overtook Scandinavia after the fall of the Soviet Union and the unification of Germany. When it all shook out, the Swedish and Finnish governments lost 2-3% of their GDP on the interventional sales, Norway's made a profit of 0.2% of GDP. During the bubble preceding intervention, Scandinavian real estate, and the stock markets went up roughly 200% before they crashed; four years later, both real estate and stocks were up over a thousand percent.

It seems churlish to mention it, but this plan is only a stop-gap. It may get markets unfrozen, but when trading resumes they may thaw down to lower prices. In fact, prices are almost certain to fall if we face up to a realization that prices were too high, to begin with. House prices were just too high, oil prices were too high, and maybe a lot of other things were overpriced. As a nation, we borrowed too much, bought too much, forced prices too high. Leveraging, borrowing and prices all must, therefore, come down. But slowly and gradually, please. We will eventually grow our way out of this housing glut; floods, fires, and population growth will eventually use up the housing surplus.

|

| Credit Bubble |

Meanwhile, we have a short-term and long-term problem with determining fair value without ongoing transactions to verify them. In the short term, some government employee must judge the fair value of securities locked in frozen markets. When the crisis is over, that job is done. In the longer run, it will be necessary to maintain a continuing estimate of the value of the securities held by banks and corporations, so the proportion of debt can be calculated. Recent debts of investment banks were often 33 times the value of their stockholder equity. That seems to be too risky, and perhaps the regulators should insist on ratios of 10 to one, such as most commercial banks maintain. The best ratio is one problem, but a greater one is that no one can be sure what the underlying equity is worth unless an active market provides a precise comparison. There has been a tendency to turn to accountants to calculate an answer to this uncertainty.

In November 2007, FAS 157 was issued, declaring that fair value will be whatever the owner can sell a security for. In frozen markets, that sometimes proved to be nothing at all and obviously caused problems. This Financial Accounting Standard replaced Statement 125, which declared that fair value was whatever an informed buyer would be willing to pay. These two standards, in the absence of active real transactions, can differ so widely in a frozen market that statutory measurements of corporate riskiness are sometimes highly inappropriate. No amount of splitting the difference will satisfy the participants when serious issues are at stake since their resolution depends on the time available to find a willing counterparty, and during that interval whether alternative resources are available to satisfy creditors. Many traders have misperceived the signal when perfectly healthy securities had to be dumped in frozen markets. When the store of healthy securities runs out however, distressed debts must be liquidated at a loss. The qualifiers -- trading volumes, available reserves, illiquid reserves, historical volatility -- of a more accurate estimation of riskiness are evident, but it is not clear that a unified scoring could describe them.

Originally published: Sunday, September 28, 2008; most-recently modified: Sunday, July 21, 2019