7 Volumes

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Colonial Times

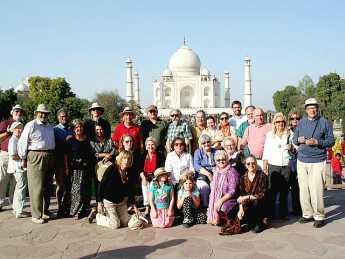

More than half of American history took place before 1776, but after 1492. For Philadelphia, Colonial history lasted about a century.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

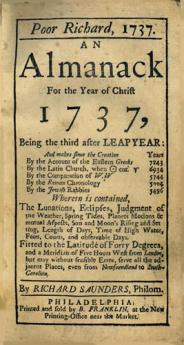

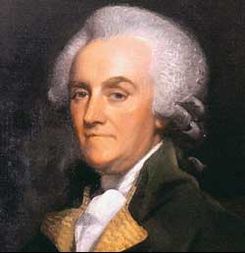

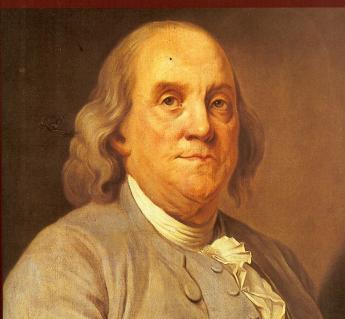

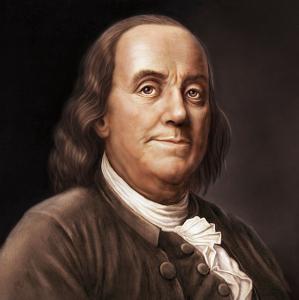

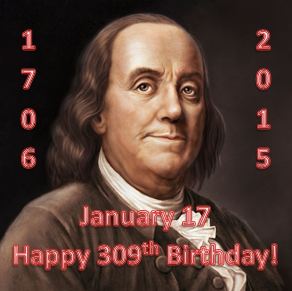

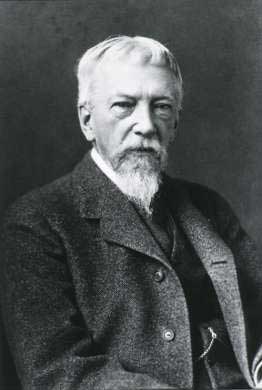

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

Benjamin Franklin

A collection of Benjamin Franklin tidbits that relate Philadelphia's revolutionary prelate to his moving around the city, the colonies, and the world.

REFERENCES

| Benjamin Franklin: An American Life Walter Isaacson ISBN-10: 0684807610 | Amazon |

| Benjamin Franklin: Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital Professor I. Bernard Cohen Library Number:54-11251 | Amazon |

| Benjamin Franklin Carl Van Doren ISBN-13: 978-0140152609 | Amazon |

| Benjamin Franklin Edmund S. Morgan ISBN-13: 978-0300095326 | Amazon |

| Benjamin Franklin Numbers: An Unsung Mathematical Odyssey Paul C. Pasles ISBN-13: 978-0691129563 | Amazon |

Benjamin Franklin ("Poor Richard") was one of the most remarkable men who ever lived.

Benjamin Franklin: Chronology

|

| Ben Franklin on the cover of Time magazine |

January 17, 1706 Born in Boston, the thirteenth child of a candle maker; only went through 2nd Grade, Apprenticed to his brother as a printer, ran away to Philadelphia age 17 .

1723 Arrived in Philadelphia penniless, readily found work as a printer.

1725-26 First trip to England. Researched printing equipment, but probably lived a riotous life.

1726-1748 Returned to Philadelphia to found his own print shop and bookstore. Wrote and printed Poor Richard's Almanack organized local tradesmen into the Junto, formed partnerships with sixty printers throughout the colonies, obtained the print business of local governments, became postmaster. Able to retire at the age of 42 by selling his business for 18 annual payments, which offered him comfort and ease for considerably longer than his life expectancy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1751 Helped found Pennsylvania Hospital. Entered the legislature.

1751-1757 Active in legislature, rising to leadership during the French and Indian War, Pontiac's Rebellion and the uprising of the Paxtang Boys.

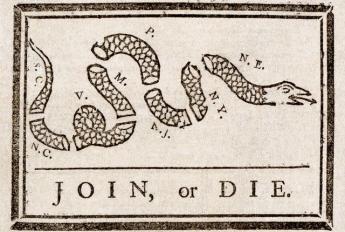

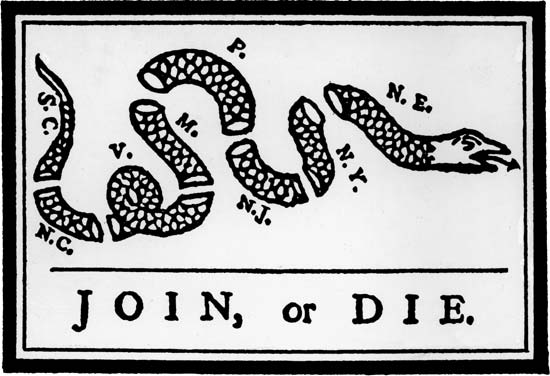

1754Took a noteworthy carriage trip to the Albany Conference, accompanied by fellow delegates Proprietor Penn and Isaac Norris at which he proposed unification of the thirteen colonies to fight against the French. Composed the first political cartoon "Join or Die" for that purpose. Notes for the trip on the blank pages of "Poor Richard's Almanac", now at Rosenbach Museum. The other delegates rejected the plan.

1757-1762 Second time in England. Acted as representative of both Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. After his electoral defeat, he returned to England for a total of eighteen years, suggesting hidden British sympathies may have been present. .

1762-1764 Returned to Pennsylvania Legislature, where his unpopular agitation for replacing the Penn Proprietors with direct Royal government led to his electoral defeat and the end of his elective career. The defeated but determined Quaker party sent him to England to lobby against the Penn family and for the rule of Pennsylvania by the King.

1764-1775 Third British visit. Although unsuccessful in his lobbying, his fame as a scientist made him welcome among the famous members of the Enlightenment, like Hume, Adam Smith, Mozart. Meanwhile, the colonies became considerably more rebellious than he was. His blunder with the publication of some letters gave the British Ministry an opportunity to humiliate and disgrace him in public, probably as a warning to the mutinous New England leaders. It irreconcilably alienated Franklin, who sulked, then packed up and joined the Continental Congress the day he arrived back home.

March, 1775-October, 1776 Brief but fateful return to America. Decisions were made in London to put down the colonists by as much force as necessary. Meanwhile, Franklin persuaded the Continental Congress they must declare independence from England if they expected help from the French.

July 4, 1776, Independence is declared within days after the arrival of a massive British fleet in New York harbor. Franklin dispatched to France to secure the assistance he was confident he could get.

1777-1785 France. Franklin served admirably as American ambassador, his wit and charm persuading the French to overextend themselves with ships, supplies, and money, and very likely contributing to the French Revolution by popularizing the American one.

1785-1790 Returning as a national hero for his final five years of life, Franklin loaned his personal influence to the constitutional convention, became President of Pennsylvania, worked for the abolition of slavery.

April 17, 1790 Died, probably of complications associated with kidney stones.

Franklin Crown Soap

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

It's easy to make soap, but hard to make good soap. You just boil animal fat with wood ashes, and you get soft soap. Softsoap was sold by the barrel in the Colonies. Hard soap is made by adding salt to the mix, allowing it to be sold by the bar. The trick to all this is to know how long to boil it, how much ash of what kind, and how much salt. If you get it wrong it will be too soft or too hard, and if you have too much lye from the ashes, it will burn your skin when you wash with it. Most people made their own soap in the colonies, so they often got it wrong, because they didn't exactly know what they were doing. What they were doing was called Saponification, after the old Roman hill of Sapo. The legend is that burnt animal sacrifices in the Temple at the top of the hill would wash down and help the washerwomen in the river below get their clothes clean. The point of all this is that Josiah Franklin, the father of Benjamin and sixteen other children, was a candle maker and a soap boiler. Somehow he got the recipe right, particularly the part about adding salt, and made famously fine bars of soap with a crown stamped on them -- Crown soap. The formula was a strict family secret, the source of family discord when one sister let it out.

The point which needs reflection is that nobody in Franklin's family ever heard of potassium hydroxide, saponification, triglycerides or fatty acids. The process of achieving fame throughout the colonies -- for making a product everyone could make haphazardly -- must have involved a careful series of experiments with different fats, tallows and lards, with different amounts of ashes of various trees, and different amounts of salt. When you got it right it worked consistently, but it would have been necessary to make many experiments to get it right. To avoid repeating the same mistakes, it would be necessary to keep careful records. In other words, little Benjamin must have observed a great many examples of experimental chemistry which made him a chemist fit to talk with Lavoisier and Priestly on equal terms, even though he quit school after the second grade. His childhood was one long demonstration of a motto of Claude Bernard: "Experiment first, a theory later."

Logan, Franklin, Library

|

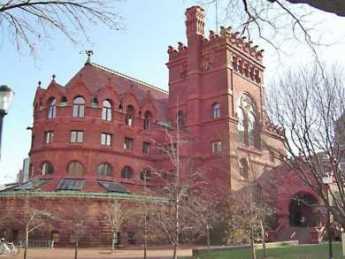

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

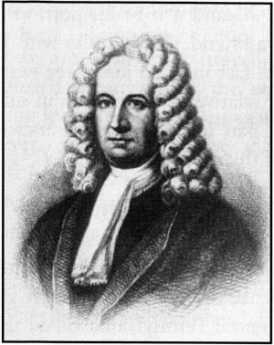

Jim Greene is the librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia, and one of the leading authorities on James Logan, the Penn Proprietors' chief agent in the Colony. Since Logan and Ben Franklin were the main forces in starting the oldest library in America, knowing all about Logan almost comes with the job of Librarian. We are greatly indebted to a speech the other night, given by Greene at the Franklin Inn, a hundred yards away from the Library.

|

| James Logan |

Logan has been described as a crusty old codger, living in his mansion called Stenton and scarcely venturing forth in public. He was known as a fair dealer with the Indians, which was an essential part of William Penn's strategy for selling real estate in a land of peace and prosperity. Unfortunately, Logan was behind the infamous Walking Purchase, which damaged his otherwise considerable reputation. Logan must have been a lonesome person in the frontier days of Philadelphia because he owned the largest private library in North America and was passionate about reading and scholarly matters. When he acquired what was the first edition of Newton's Principia, he read it promptly and wrote a one-page summary. Comparatively few people could do this even today. It's pretty tough reading, and those who have read it would seldom claim to have "devoured" it.

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Except young Ben Franklin, who never went past second grade in school. The two became fast friends, often engaging in such games as constructing "Magic Squares" of numbers that added up to the same total in various ways. For example, Franklin doodled off a square with the numbers 52,61,4,13,20,29,36,45 (totaling 260) on the top horizontal row, and every vertical row beneath them totaling 260, as for example 52,14,53,11,55,9,50,16, while every horizontal row also totaled 260 as well. The four corner numbers, with the 4 middle numbers, also total 260. Logan constructed his share of similar games, which it is difficult to imagine anyone else in the colonies doing at the time.

Logan and Franklin together conceived the idea of a subscription library, which in time became the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1732. The subscription required of a library member was intended to be forfeited if the borrower failed to return a book. Later on, the public was allowed to borrow books, but only on deposit of enough money to replace the book if unreturned. We are not told whose idea was behind these arrangements, but they certainly sound like Franklin at work. More than a century later, the Philadelphia Free Library was organized under more trusting rules for borrowing which became possible as books became less expensive.

Logan died in 1751, the year Franklin at the age of 42 decided to retire from business -- and devote the remaining 42 years of his life to scholarly and public affairs. He first joined the Assembly at that time, so he and Logan were not forced into direct contention over politics, although they had their differences. How much influence Logan exerted over Franklin's plans and attitudes is not entirely clear; it must have been a great deal.

Franklin: Upstart Hero of King George's War (1747)

In 1747, Benjamin Franklin had a life-transforming experience, acting quite unlike his character before, or later. At that time, Old Europe was engaged in some distant tribal skirmishing which has come to be known as King George's War. King George II, that is, under whose rule Franklin in 1751 inscribed on the cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital that Pennsylvania was flourishing, "for he sought the happiness of his people."

|

|

The cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital inscribed by Franklin. |

Those distant commotions suddenly developed a harsh reality for the little pacifist sanctuaries on the Delaware River, when French and Spanish privateers suddenly raided and destroyed settlements on Delaware Bay. The Quaker Assemblies and their absentee Proprietor merely dithered and huddled in the face of what impended as a totally unexpected threat of annihilation of the pacifist colonies. It probably only seemed natural for the owner of the largest newspaper in the colony to publish a pamphlet called "Plain Truth," urging the inhabitants to rally to their own defense, and pressure their government to lead them. The Quaker leaders were in fact unable to readjust a lifetime of pacifist belief in a few days of an emergency, and the English Proprietor, then Thomas Penn, was far too remote to take active charge of matters. So, Franklin gave speeches, also an unfamiliar role for him, and finally brought out a detailed proposal for the creation of a Pennsylvania Militia. Ten thousand volunteers promptly signed up, elected Franklin as their Colonel; but he declined, and served as a common soldier.

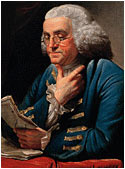

|

| Benjamin Franklin in 1767. |

Against naval attack, the Militia needed cannon, which did not exist in the colony. So Franklin organized a lottery, raised three thousand pounds, and tried to buy cannon from Governor Clinton of New York. New York declined to sell, and so Franklin led a delegation to New York to negotiate. The negotiations largely consisted of getting Governor Clinton drunk and convivial, but they were successful, the artillery was shipped off to Philadelphia. Although they were undoubtedly grateful to Franklin for saving the day, this entirely extra-legal recruitment of an army badly rattled the Quakers and their Proprietor, since it demonstrated the ineffectiveness of their governance at a time of obvious crisis, and might ultimately have led to their overthrow. Franklin's heroic behavior seemed so threatening to Thomas Penn that he described him as "a dangerous man," acting like "the Tribune of the People."

When the underlying commotion in Old Europe subsided, the threat to the colonies disappeared, so the Militia disbanded in a year. Franklin seemed to be just as uncomfortable with his unaccustomed role as the governing leaders were, and he hardly ever mentioned it again. However, this is the sort of reflex leadership which makes political careers, and it surely influenced his decision to retire from business in 1748, run for election to the Assembly, and live like a gentleman. Seven years later, during the French and Indian War, he had become the chosen leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly, had much longer to think through what he was doing, and had learned how to organize a war. By that time, as the saying goes, he knew who he was. He was a man whose silent memories could flashback to that time when a bald fat printer stepped out of the crowd, saying "Follow me," and ten thousand men with muskets did so.

Addressing The Proprietors' Dilemma

|

| William Penn |

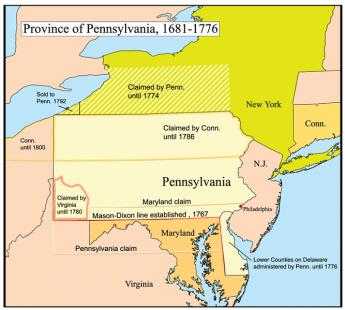

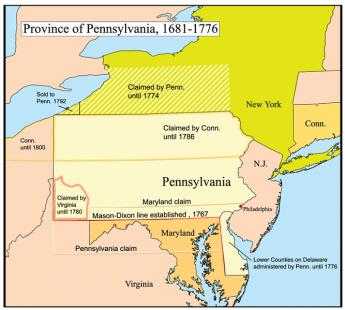

DURING the century which elapsed after Charles II gave away Pennsylvania to William Penn, several hundred thousand people moved in and changed the place. Transformation of the wilderness explains why the terms of the grant seemed logical at one time, but proved almost impossible to manage at the time of the Revolution. The Penns with thirty million acres was the largest landholders in America but, in fact, by 1776 only five million acres had been sold in a century. The land they held was simply too much for one family to handle without an army, and although the original settlers were pacifists, the later ones were combative.

Charles II had written in the Charter that the Penns could have the land if they could maintain order there, retaining the legal right for the King to recover the land if they didn't. This fall-back provision certainly reflects some doubt about the ability of pacifists to shoot the necessary number of Indians, Frenchmen, and Spaniards. On the other hand, the motive for a King delegating away his authority in the first place became clearer when the Penns experienced severe financial strain defending the Northeast corner of the state against the Connecticut invaders. It furthermore helps us understand why Benjamin Franklin received such a cold reception when he was sent to London by the colonists to request the crown to reassert civil authority over the state. That did not necessarily imply stripping the Penns of their land; by this time, it was clear that the Penn Proprietors were mainly interested in selling it to someone. The charter of the King's grant included the offer to make William Penn a King; and although the offer was declined, the Penn Proprietors retained some degree of legal power to govern the territory. Franklin for all his persuasive power was, unfortunately, the one man Thomas Penn didn't want to see, because of the threat he had posed by raising a militia in King George's War, and later his expansiveness at the Albany Conference. And Thomas was a good friend of the King. The King didn't want these problems and particularly didn't want the expense. Ambiguities were, of course, shared all around. William Penn had quite shrewdly seen it was more sensible to treat the Indians decently than to fight with them, and cheaper too; the lesson was not lost on the British crown. But the French Kings posed a much larger world-wide threat to the British colony, finding for their part, it was rather economical to supply munitions to the Indians on the frontier and stir them up emotionally. The French and Indian War was a small component of the Seven Years War, which proved to be a costly adventure for both sides. Its local cost certainly overwhelmed the ability of one family to underwrite local governance in a large wartime colony, and it jeopardized the finances of the British Monarch to carry the rest. The resulting need to tax the colonies for their defense sent things downhill, eventually to the Stamp Act, the Townshend duties, and the Tea Tax. Everyone made lots of mistakes as the whole structure underwent revision, just as pacifists are certain will happen in any war. But when a pacifist utopian colony was prospering while successfully dealing with the Indians, it's all sort of a big pity.

|

| Thomas Penn |

With much to lose, the Penn family did pretty well with the resources at hand. By the time of the Revolution, three generations of Penns had divided up ownership shares of the Proprietorship. When French and Spanish ships were marauding the Delaware River, Benjamin Franklin the local printer took it on himself to organize a militia which persists today as the Pennsylvania National Guard, the Twenty-eighth Division. Franklin was suddenly a local hero to everyone, except to one man, Thomas Penn. Thomas was the dominant figure in the Penn family for many years and worried deeply about Franklin, a man who could stir up ten thousand armed volunteers with a poster proclamation. Such a man could mean trouble, as indeed events later proved to be the case.

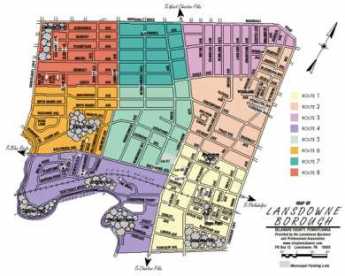

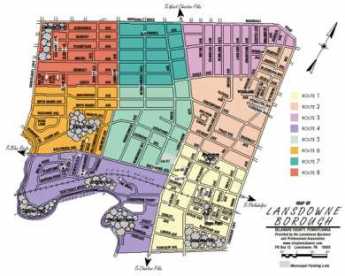

John Penn was the Governor of the state, residing in his mansion on the Schuylkill called Lansdowne, doing his best to ingratiate the locals. He struggled to be diplomatic when arguing for the decisions actually made by his Uncle Thomas in London. Thomas Penn, on the other hand, was an important friend of the British Ministry, and a notable person in aristocratic England. As the Revolutionary War approached, the problem transformed into how to hold on to 25 million unsold acres, while remaining unsure who was going to win the impending war.

|

| John Penn |

The strategy the Penns adopted was to get out of the business of running a local government, as Franklin had proposed but in a different way. John Penn the Governor became a private citizen, just a local real estate agent. He took an oath of allegiance to the Revolutionary government, which in the chaos of the time was equivalent to becoming an American citizen. Meanwhile, other members of the family remained in England, ready to revise the arrangement if the British won the war. It was all fairly transparent straddling of the issues, which was only even remotely likely to be effective because of the enormous store of Penn goodwill built up over a century. In 1789 revolutionary France, for example, such sentimentality would not have delayed the tumbrels to the guillotine for five minutes.

Meanwhile, an unexpected difficulty was created. By withdrawing from control of the local government, the Penn family also withdrew from the defense of state borders against neighboring colonies. Under the circumstances, the Penns were afraid to appeal to the King, while the new government of Pennsylvania found the Articles of Confederation were merely a wartime tribal compact. The Articles stabilized boundaries mainly for the purpose of conducting a united war, and did not seriously contemplate a continuing judicial role for disputes between colonies. When the Revolution was finally over, the Penn Proprietors were not left with much of a bargaining position. The new State of Pennsylvania offered, and they accepted, about fifteen cents an acre to surrender their claims. In Delaware, they got essentially nothing for those three counties. Only in New Jersey did the Proprietors' claims remain durable after the new nation was established. The Proprietorship of East Jersey survived into the late 20th century, and the Proprietorship of West Jersey continues to return a small profit even today. The New Jersey curiosity is treated in a separate essay.

B. Franklin and Daylight Savings

|

| Daylight Saving Time |

Ben Franklin's father was a candle maker working out of his home. Little Benjamin was thus in a position to watch the rise and fall of candle sales with each passing season; it must have been a central fact of that household's economy. Many years later when he was Ambassador to France, the suggestion of Daylight Savings Time was likely less a demonstration of his ingenuity than a testimony to his powers of observation and reflection.

Now, over two centuries later than that, the point is being raised that what with Nintendo and television and all, daylight time may actually cause more consumption of electrical energy than it saves. It's a striking thought, even quite a revolutionary one. Until you remember that Franklin, more than any one person, also discovered electricity.

Rise and Fall of Books

| ||

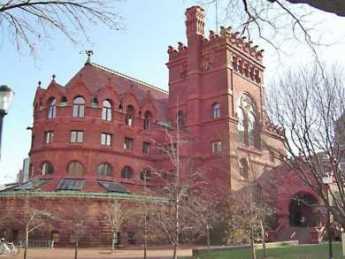

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

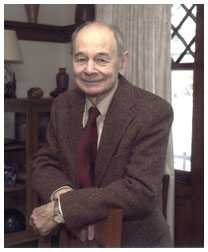

John C. Van Horne, the current director of the Library Company of Philadelphia recently told the Right Angle Club of the history of his institution. It was an interesting description of an important evolution from Ben Franklin's original idea to what it is today: a non-circulating research library, with a focus on 18th and 19th Century books, particularly those dealing with the founding of the nation, and, African American studies. Some of Mr. Van Horne's most interesting remarks were incidental to a rather offhand analysis of the rise and decline of books. One suspects he has been thinking about this topic so long it creeps into almost anything else he says.

|

| Join or Die snake |

Franklin devised the idea of having fifty of his friends subscribe a pool of money to purchase, originally, 375 books which they shared. The members were mainly artisans and the books were heavily concentrated in practical matters of use in their trades. In time, annual contributions were solicited for new acquisitions, and the public was invited to share the library. At present, a membership costs $200, and annual dues are $50. Somewhere along the line, someone took the famous cartoon of the snake cut into 13 pieces, and applied its motto to membership solicitations: "Join or die." For sixteen years, the Library Company was the Library of Congress, but it was also a museum of odd artifacts donated by the townsfolk, as well as the workplace where Franklin conducted his famous experiments on electricity. Moving between the second floor of Carpenters Hall to its own building on 5th Street, it next made an unfortunate move to South Broad Street after James and Phoebe Rush donated the Ridgeway Library. That building was particularly handsome, but bad guesses as to the future demographics of South Philadelphia left it stranded until modified operations finally moved to the present location on Locust Street west of 13th. More recently, it also acquired the old Cassatt mansion next door, using it to house visiting scholars in residence, and sharing some activities with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on its eastern side.

|

| Old Pictures of the Library Company of Philadelphia |

The notion of the Library Company as the oldest library in the country tends to generate reflections about the rise of libraries, of books, and publications in general. Prior to 1800, only a scattering of pamphlets and books were printed in America or in the world for that matter, compared with the huge flowering of books, libraries, and authorship which were to characterize the 19th Century. Education and literacy spread, encouraged by the Industrial Revolution applying its transformative power to the industry of publishing. All of this lasted about a hundred fifty years, and we now can see publishing in severe decline with an uncertain future. It's true that millions of books are still printed, and hundreds of thousands of authors are making some sort of living. But profitability is sharply declining, and competitive media are flourishing. Books will persist for quite a while, but it is obvious that unknowable upheavals are going to come. The future role of libraries is particularly questionable.

Rather than speculate about the internet and electronic media, it may be helpful to regard industries as having a normal life span which cannot be indefinitely extended by rescue efforts. No purpose would be served by hastening the decline of publishing, but things may work out better if we ask ourselves how we should best predict and accommodate its impending creative transformation.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1470.htm

Philosophy Means Science in Philadelphia

|

| American Philosophical Society Seal |

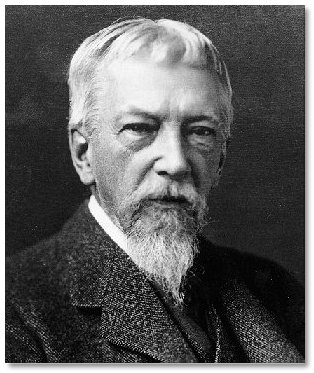

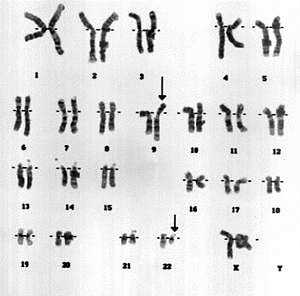

In the age of the Enlightenment, science was called natural philosophy; that accounts for the present custom of awarding PhD. degrees in chemistry and botany. The sort of thing which interested Ralph Waldo Emerson was called moral philosophy, and you will have to visit some other place than the A.P.S. if that is what interests you. Roy E. Goodman is presently the Curator of Printed Material (some would say he was chief librarian) at the American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin who was clearly the most eminent scientist of his day, having discovered and explained the nature of electricity.

|

| Roy E. Goodman |

Roy Goodman is descended from cowboys and rodeo stars, but in spite of that he gave an entertaining talk recently at the Right Angle Club about this society devoted to useful knowledge, this oldest publishing house and scholarly society in America, once the home of the U.S. Patent Office, and scientific library and museum. They have many rare items in their collection, but the unifying theme is not a rarity, but curiosity. You might say some of the items reflect the whimsy of Franklin, but it would be fairer to say it is an enduring monument to Franklin's universal curiosity about all things.

|

| Nobel Prize Medal |

There are about 900 members of APS, about 800 of them Americans, about 100 of them winners of a Nobel Prize. Let's just make a little list of a very few notables in the past and present membership. Start with the first four Presidents of the United States, add Alexander Hamilton and Lafayette, David Rittenhouse and Francis Hopkinson and you get the idea that Founding Fathers got in early. Robert Fulton, Lewis and Clark, Alexander Humboldt, John Marshall were early members, and more recent ones were Madame Curie,

B. Franklin, Scientist

|

| Franklin Institute |

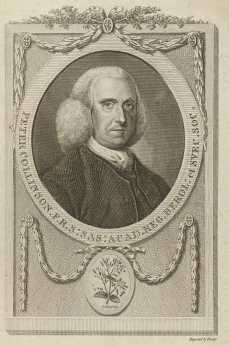

FROM time to time, the Franklin Institute has a display of its own and other museums' collections of the scientific instruments of Benjamin Franklin. It's well worth anybody's visit when it is available because the beauty and craftsmanship of these instruments alone make them remarkable works of art. Franklin was financially able to retire at the age of 42, and it tells you something of the 18th-century culture that Franklin took up scientific experiments in order to be like other independently wealthy gentlemen. Science, or natural philosophy, this seems to have been in a class with getting a coat of arms and having his portrait painted, all of which cheapens our view of Franklin as a scientist.

|

| Peter Collinson, F.R.S. |

In fact, Franklin was conducting an active correspondence with other scientists interested in electricity for many years, in particular, one Peter Collinson, F.R.S. in London. Collinson collected thirteen of Franklin's letters about his experiments, the earliest dated 1747, and printed them in 1751 as an 86-page book called Experiments and Observations about Electricity . By 1769, several more letters expanded the book to 150 pages, almost all of them describing reproducible experiments in great detail. The kite and key episode are described, but soberly and sparingly. Without making the point too graphically, an appendix was added describing how lightning had been used to kill some turkeys, so a somewhat increased power would probably be enough to kill a person. Franklin recognized that something was moving from here to there, that it had positive and negative charges, and that it was possible to store it up in a storage battery. He recognized the difference between substances that would conduct electricity and other substances that would act as insulators. Later on, he would discover that the torpedo fish stores and transmits electricity, suggesting that somehow animals made and used electricity as part of life. And of course, he put the discoveries to practical use as lightning rods, which he refused to patent.

|

| Madame Helvetius |

By the time he went to England and France as a negotiator, his wide acquaintanceship in the scientific world was happy to introduce him to other famous people, like kings, Voltaire, Mozart, and Madame Helvetius the wife of the Swiss philosopher, the only woman to whom he is known to have made a proposal of marriage. When someone mentioned standing before a king, he replied he had stood before five of them. King Louis XVI, for example, appointed Franklin to a four-man committee to investigate hypnotism, then being touted as "animal magnetism" by Franz Mesmer. The other three committee members were unfortunately also destined to become acquainted with the guillotine: Brother Joseph-Ignace Guillotin himself, and two future victims of the invention, Antoine Lavoisier the discoverer of oxygen, and Jean Sylvain Bailly who first calculated the course of Halley's Comet, not to mention Louis XVI himself. It is not easy to think of any other scientist who was able to mix his scientific fame with changing international history, acquiring in the process the sobriquet of the founder of the American diplomatic corps. But then, he was witty as well as smart, and his career is a warning to those who now hope to devote their whole lives to being admitted to a prestige college and then coasting on its reputation. Franklin, it should be remembered, dropped out of school after the second grade.

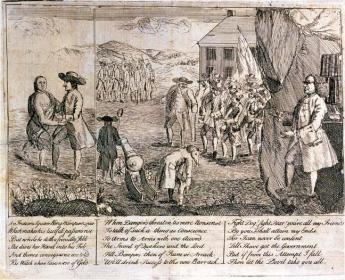

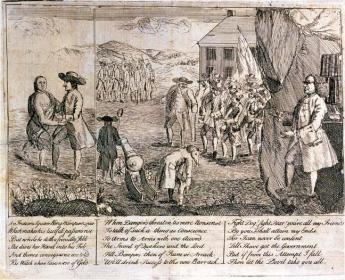

Pembertons

|

| Israel Pemberton, Ben Franklin satire l |

Ralph Pemberton was an English Quaker well before 1650; he may have been a Quaker before William Penn was one. As an old man, he accompanied his son Phineas to Pennsylvania in 1682. They established a farm on the banks of Delaware in Bucks County called Grove Place, and Phineas soon became one of the chief men in the colony. In the next generation, Israel Pemberton became one of the best educated, richest merchants in the colony. But it was Israel's son also called Israel, who earned the title of King of the Quakers. He was one of the founding Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital along with Benjamin Franklin and one of his brothers, James Pemberton, and was a generous philanthropist and leader of a number of other civic organizations. Just exactly what provoked his famous political disputes with Franklin is not clear, but he was a leading friend of the Indians, whom Franklin never much liked. Israel Pemberton strongly and effectively argued William Penn's policy of friendship with the Indians, particularly insisting that sales of land to colonists should be prevented until there was a clear agreement with the Indians about the ownership. Unfortunately, pressures built up as Europeans immigrated faster than this policy could accommodate smoothly, and Franklin mostly sided with the impatient immigrants -- and squatters. This disagreement came to a head in 1756 when Pemberton negotiated a treaty of peace with the Indians at a conference at Easton. Although this treaty seemed to settle matters, it came against a background of the descendants of William Penn abandoning Quakerism. They, however, remained the proprietary owners of the Province with a more narrow focus on speeding up land sales to maximize their investment. Much of the internal dynamics of these quarrels before the Revolutionary War remain unclear and possibly somewhat misrepresented.

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

When the Revolution came, Pemberton viewed it with disfavor, mostly for pacifist rather than purely Tory reasons. Feelings ran high since the Pembertons were influential citizens with the potential to dissuade wavering neighbors, which made it difficult to tolerate them as invisible bystanders. However that may be, the three Pemberton brothers and twenty other wealthy and influential Quakers were arrested and, without hearing or trial, thrown in the back of an oxcart and sent into exile in Virginia for eight months. Their journey was a curious one, along a trail up the Schuylkill to the ford at Pottstown, and then down the Shenandoah Valley, an area in which they were well known and highly respected, greeted with great sympathy as they traveled. Isaac's brother John, who had spent several years as a missionary, died during this exile.

|

| John Clifford Pemberton |

In some ways, the most curiously notable Pemberton was John Clifford Pemberton, who applied to West Point on his own initiative and was appointed by Andrew Jackson who had been a friend of his father. In itself, it is curious that so combative a person and so vigorous an enemy of the Indians -- as Jackson certainly was -- would have Quaker friendships. But he did not misjudge John Clifford, who became a diligent professional warrior for his country in a number of military incidents with the Indians, the Mexicans, and the Canadians, rising to the rank of captain in the regular Army at the opening of the Civil War. In spite of personal efforts by General Winfield Scott to dissuade him, he resigned his commission and volunteered in the Confederate army. He was quickly promoted to major, then a brigadier general and eventually to Lieutenant General. As such, he was the commanding Confederate officer at the fifty-day siege of Vicksburg where he was finally forced to surrender to Grant's army. In a prisoner exchange, he was returned to the Confederate side, which they had no openings for Lieutenant Generals. He resigned and re-enlisted as a common soldier, but was quickly promoted to the rank of Colonel, in charge of the artillery at the final siege of Richmond. After the war, he became a farmer in Warrenton, Virginia, but was visiting at the family home in Penllyn when he died in 1881. John Clifford Pemberton, the highest-ranking general on the grounds, lies buried in Laurel Hill cemetery right next to Israel Pemberton. In some sort of triumph of the South, he here out-ranks George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Just how his pacifist family reconciled itself to his heroism can only be imagined.

Franklin Bets His Wad on General Braddock

|

| General Edward Braddock |

The defeat of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) in 1755 was not a turning point of the French and Indian War, because although the French won the battle, they lost that War, they also lost Canada in the Seven Years War that followed, and eventually had to sell what remained of their American dream in 1804 as the Louisiana Purchase. The French dream was an empire stretching in an arc from the St. Lawrence River to New Orleans, leaving the British only the thirteen Eastern seaboard colonies.

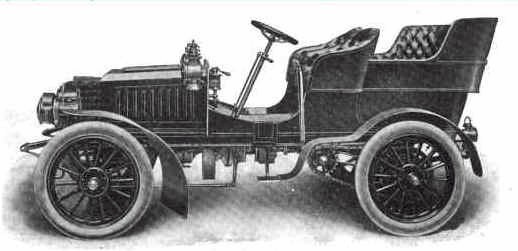

Nevertheless, the disastrous defeat of the Redcoats was a real turning point in the attitudes of two direct participants, Lieutenant Colonel George Washington of Virginia, and Pennsylvania's political leader, Benjamin Franklin. Both men greeted the arrival of Braddock's troops in America with great relief because it was increasingly evident to them that the Colonies themselves were too indecisive to survive. Both of them were in a unique personal position to see that the French and their Indian Allies were serious about conquering the backcountry, even likely to do so. These two staunch British patriots, therefore, threw themselves into the crisis, with Washington eventually having two horses shot from under him, taking charge of the retreat after Braddock's death. And Franklin pledged his considerable personal fortune on Braddock's behalf, almost losing it and spending the rest of his life in debtor's prison as Robert Morris would later actually do. These two men knowingly laid their lives on the line for the British Empire and came very close to losing everything else for their King and country.

Franklin had retired seven years earlier, a rich man at the age of 42. We now know that he lived like a gentleman for another 42 eventful years. Puttering with science and public works, he joined the Assembly in 1750. It was not long before he was the political leader of the Colony, in a peculiar struggle with the dominant Quaker party who not only opposed war for their own self-defense but were enraged that the Penn family had turned away from Quakerism and refused to be taxed for the defense of its colony. The Governor was appointed by the Penns, with an express contract not to agree to any taxation of the Penn holdings. Since it began to look to Franklin as though everybody was trying to commit suicide rather than spend a farthing, he greeted the arrival of General Edward Braddock's redcoats with great relief. But then Braddock himself turned out to be a brave but exasperating ninny.

Braddock's plan was to take the old Indian trail from the Potomac River to the Monongahela (now Route 40), fording the Monongahela just below its junction with Ohio at Fort Duquesne, then blowing up the French fort with artillery. He had brought plenty of troops and cannons on his ocean transports, but he needed horses and wagons from the colonies. When he was warned of the dangers of Indian ambush in the wilderness, he made a much-quoted response, "These savages may be a formidable enemy to your raw American militia, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops, sir, it is impossible they would make an impression." The other thing he said was if he didn't get wagons and horses pretty damned quick, he was going back home to England.

Within two weeks, Franklin and his son William collected 259 horses and 150 wagons for him. But to do so, they had to overcome the Pennsylvania farmer suspicion that the swaggering English General wouldn't pay for the goods. To persuade them, Franklin made a public pledge to stand behind the debts with his own money, and his word was known to be good.

The other thing wrong with Braddock's plan was that the trail wasn't wide enough for the wagons and gun carriages, so he had so sent a body of axeman ahead of the troops to widen the road. Progress was at times as slow as two miles a day, plenty of time for word to be taken to Fort Duquesne that the British were coming with cannon. Since it was clear that the Fort could not withstand a siege army, the French commander ordered his troops to attack Braddock as he was crossing the Monongahela. It was meant to be an ambush, but the two armies blundered into each other on the trail, and the Indians simply fought the way they knew best, from behind trees. Two-thirds of the British were killed and most of those captured were burned at the stake. The death toll would have been even higher, and probably would have included Washington, except the Indians, ignored French orders and delayed pursuit to collect scalps. And by the way, all of Franklin's wagons were burned.

Franklin spent an anxious two months since his later reflection was that the loss of 20,000 pounds sterling would surely have ruined him. However, he was lucky that Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, an old friend of his, was appointed at Braddock's successor, and Shirley ordered the debt to be repaid out of Army funds.

The American Revolution would not come for another twenty years, but you can be sure the Braddock episode had an important impact on the minds of both Franklin and Washington. The British Army was not invincible. It was not even very smart.

Franklin's Public Pledge to Braddock

Ihappened to say I thought it was a pity they had not been landed rather in Pennsylvania, as in that country almost every farmer had his wagon. The general eagerly laid hold of my words, and said, "Then you, sir, who is a man of interest there, can probably procure them for us; and I beg you will undertake it." I asked what terms were to be offered the owners of the wagons, and I was desired to put on paper the terms that appeared to be necessary. This I did, and they were agreed to, and a commission and instructions accordingly prepared immediately. What those terms were will appear in the advertisement I published as soon as I arrived at Lancaster, which being, from the great and sudden effect it produc'd, a piece of some curiosity, I shall insert it at length, as follows:

"ADVERTISEMENT. "LANCASTER, April 26, 1755.

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

"Whereas, one hundred and fifty wagons, with four horses to each wagon, and fifteen hundred saddle or pack horses, are wanted for the service of his majesty's forces now about to rendezvous at Will's Creek, and his excellency General Braddock having been pleased to empower me to contract for the hire of the same, I hereby give notice that I shall attend for that purpose at Lancaster from this day to next Wednesday evening, and at York from next Thursday morning till Friday evening, where I shall be ready to agree for wagons and teams, or single horses, on the following terms, viz.: I. That there shall be paid for each wagon, with four good horses and a driver, fifteen shillings per diem; and for each able horse with a pack-saddle, or other saddle and furniture, two shillings per diem; and for each able horse without a saddle, eighteen pence per diem. 2. That the pay commences from the time of their joining the forces at Will's Creek, which must be on or before the 20th of May ensuing, and that a reasonable allowance is paid over and above for the time necessary for their traveling to Will's Creek and home again after their discharge. 3. Each wagon and team, and every saddle or pack horse is to be valued by indifferent persons chosen between me and the owner; and in case of the loss of any wagon, team, or other horse in the service, the price according to such valuation is to be allowed and paid. 4. Seven days' pay is to be advanced and paid in hand by me to the owner of each wagon and team, or horse, at the time of contracting, if required, and the remainder to be paid by General Braddock, or by the paymaster of the army, at the time of their discharge, or from time to time, as it shall be demanded. 5. No drivers of wagons, or persons taking care of the hired horses, are on any account to be called upon to do the duty of soldiers or be otherwise employed than in conducting or taking care of their carriages or horses. 6. All oats, Indian corn, or other forage that wagons or horses bring to the camp, more than is necessary for the subsistence of the horses, is to be taken for the use of the army, and a reasonable price paid for the same.

"Note.--My son, William Franklin, is empowered to enter into like contracts with any person in Cumberland county. "B. FRANKLIN."

-------------------------------------------

To the inhabitants of the Counties of Lancaster, York and Cumberland.

"Friends and Countrymen,

|

| General Braddock |

"Being occasionally at the camp at Frederic a few days since, I found the general and officers extremely exasperated on account of their not being supplied with horses and carriages, which had been expected from this province, as most able to furnish them; but, through the dissensions between our governor and Assembly, money had not been provided, nor any steps taken for that purpose.

"It was proposed to send an armed force immediately into these counties, to seize as many of the best carriages and horses as should be wanted, and compel as many persons into the service as would be necessary to drive and take care of them.

"I apprehended that the progress of British soldiers through these counties on such an occasion, especially considering the temper they are in, and their resentment against us, would be attended with many and great inconveniences to the inhabitants, and therefore more willingly took the trouble of trying first what might be done by fair and equitable means. The people of these back counties have lately complained to the Assembly that a sufficient currency was wanting; you have an opportunity of receiving and dividing among you a very considerable sum; for, if the service of this expedition should continue, as it is more than probable it will, for one hundred and twenty days, the hire of these wagons and horses will amount to upward of thirty thousand pounds, which will be paid you in silver and gold of the king's money.

"The service will be light and easy, for the army will scarcely march above twelve miles per day, and the waggons and baggage-horses, as they carry those things that are absolutely necessary to the welfare of the army, must march with the army, and no faster; and are, for the army's sake, always placed where they can be most secure, whether in a march or in a camp.

"If you are really, as I believe you are, good and loyal subjects to his majesty, you may now do a most acceptable service, and make it easy to yourselves; for three or four of such as can not separately spare from the business of their plantations a waggon and four horses and a driver, may do it together, one furnishing the wagon, another one or two horses, and another the driver, and divide the pay proportionately between you; but if you do not this service to your king and country voluntarily, when such good pay and reasonable terms are offered to you, your loyalty will be strongly suspected. The king's business must be done; so many brave troops, come so far for your defense, must not stand idle through your backwardness to do what may be reasonably expected from you; wagons and horses must be had; violent measures will probably be used, and you will be left to seek for a recompense where you can find it, and your case, perhaps, be little pitied or regarded.

"I have no particular interest in this affair, as, except the satisfaction of endeavoring to do good, I shall have only my labor for my pains. If this method of obtaining the wagons and horses is not likely to succeed, I am obliged to send word to the general in fourteen days; and I suppose Sir John St. Clair, the hussar, with a body of soldiers, will immediately enter the province for the purpose, which I shall be sorry to hear, because I am very sincerely and truly your friend and well-wisher, B. FRANKLIN."

-------------------------------------

Ireceived of the General about eight hundred pounds, to be disbursed in advance-money to the wagon owners, etc.; but, that sum being insufficient, I advanced upward of two hundred pounds more, and in two weeks the one hundred and fifty wagons, with two hundred and fifty-nine carrying horses, were on their march for the camp. The advertisement promised payment according to the valuation, in case any wagon or horse should be lost. The owners, however, alleging they did not know General Braddock, or what dependence might be had on his promise, insisted on my bond for the performance, which I accordingly gave them.

--Chapter XVI, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Armonica, Momentarily Mesmerizing

|

| Ben Franklin's Glass Armonica |

Everyone knows Ben Franklin spent a lot of time holding a wine glass. Evidently, he noticed a musical note emerges if you run your finger around the open mouth of the drinking glass, and systematically studied how the tone can be varied by varying the level of liquid in the glass. The same variation in emitted tone relates to variations in the thickness of the glass. So, he set up a series of different sized glasses impaled on a horizontal broomstick, enough to cover three octaves, rotated the broomstick with a treadle like those used for spinning wheels -- and made music. The tone has a haunting penetration to it, which induced both Beethoven and Mozart to write special compositions for the harmonica, and the Eighteenth Century went wild with enthusiasm.

|

| Glass Armonica |

Unfortunately, a number of the young ladies who played the armonica went mad. We now recognize that since the finest crystal glass was used, with very high lead content, the mad ladies were suffering from lead poisoning after repeatedly wetting their fingers on their tongues. As a matter of fact, port wine at that time was stored in lead-lined casks, resulting in the same unfortunate consequences, which included stirring up attacks of gout. Franklin himself was a famous sufferer from gout, which was more likely related to the port wine than playing the harmonica, in his particular case.

Anyway, the reputation for inducing madness added to the spooky sort of sound the instrument made, attracting the attention of a montebank named Franz Anton Mesmer, who falsely claimed to be the father of hypnotism. Mesmer enhanced the society of his stage performances by hypnotizing subjects while an assistant played the harmonica, meanwhile relating all sorts of wild tales about animal magnetism. This was pretty sensational at the time until a young man in an audience suddenly died. It is now speculated that the victim probably had an epileptic seizure, but the news of this public fatal event pretty well finished Mesmer as an evangelist and the harmonica as a musical instrument.

|

| Franklin Court |

There's a replica of an armonica on display in the Franklin Court Museum around 3rd and Chestnut, which we are vigorously assured is not made with leaded crystal glass. The Park Rangers put on two daily performances by request, at noon, and 2:30 PM.

Perth Amboy Revisited

|

| Perth Amboy |

It's now moderately complicated to find Perth Amboy, New Jersey, even after you locate it on a map. Like New Castle DE it flourished early because it was on a narrow strip of strategic land, and like New Castle, eventually found itself cut off by a dozen lanes of highways crowded together by geography. It's an easy drive in both cases only if you make the correct turns at a couple of crowded intersections. Both towns were important destinations in the Eighteenth century, but by the Twentieth century, both were pushed aside by traffic rushing to bigger destinations. Industrialization hit the region around Perth Amboy somewhat harder than New Castle, destroying more landmarks, and bringing to an end its brief flurry as a metropolitan beach resort. If you aspire to preserve your Eighteenth-century glory, it's easier if you don't have too much progress in the Nineteenth. In Perth Amboy's defense, it must be noted that Jamestown and Williamsburg, Virginia had just about totally disappeared when noticed by Charles Peterson and John Rockefeller, but neither of those towns was run over by Nineteenth century industrialization. So, while New Castle has treasures to preserve and display, Perth Amboy seems to have only the Governor's mansion like the one notable building to work with. William Franklin, the illegitimate son of Benjamin, was the royal governor installed in this palace shortly before 1776.

|

| Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy |

While it is true that some wealthy local inhabitants did a lot to restore and maintain New Castle (and Williamsburg), the Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy was bought and made the home of Mathias Bruen, who is 1820 was thought to be the richest man in America. If Bruen had only had the necessary imagination and generosity, this was probably the best moment for Perth Amboy to have had a historical restoration. Instead, he added some unfortunate features to the mansion; it later became a hotel, and later on, an office building. Public-spirited local citizens are now trying to set things right, but the costs are pretty daunting. Someone has to find an inspired Wall Street billionaire like Ned Johnson to make over an entire town. Occasionally, a state government will do it, as has been done with Pennsbury. Or a national organization might become inspired, as happened with Mt. Vernon and Arlington. Its present state of peeling paint and makeshift repairs suggests uninterest in Perth Amboy's Governor Mansion by the State, and the absence of whatever it is that occasionally inspires fierce and determined local leadership. Perth Amboy needs some help and needs to forget about its handicaps. Sure, it's hard to commute anywhere, it's even hard to drive across the highways to the countryside. The bluff on the promontory was once quite arresting, now a rusting steel mill occupies that spot. Other than that, it doesn't look ominous or dangerous at all. It's just forgotten.

|

| Pennsbury Mansion |

Aside from the Royal Governor's former mansion, it is hard to find a historical marker or monument in this scene of former prosperity and glory, but there is one. Down on the beach is a bronze plaque, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the founding of -- Argentina. So there's a clue, which is not difficult to associate with all of the Hispanic names on the stores, and the Hispanics in evidence on all sides. They all seemed to know that this was once the capital of New Jersey, seemed pleased with it, and could point out the famous building. They are pleasant and friendly enough. Perhaps even a little too comfortable. Because, as William Franklin's famous father once said, all progress begins with discontent.

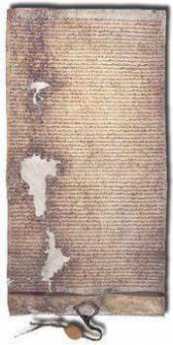

Parliament Provokes a Revolution

In some medical circles, it is postulated that George III was psychotic, possibly suffering from an inherited rare condition called porphyria.

|

| Magna Carta |

That's pretty conjectural, but it is certainly true that his mother egged him on to be a real king, a real force reversing that steady decline in the Monarchy's personal power which began with the Magna Carta. By the time in question, however, so much power had already gravitated into the hands of Parliament that the King could not act in any major way without their consent. Even today, Cabinet Ministers are spoken of as King's ministers but are in fact appointed by leaders of the majority party in Parliament. Some in Parliament, like Edmund Burke, were almost persuasive in resisting the Ministry, urging colleagues to seek reconciliation with the colonies. George III did still retain the power to appoint his favorites to important positions and used this patronage extensively to control the country. Political party chieftains, on the other hand, retained and retain today the power to nominate the party candidate for Parliament in any particular district. The leadership thus selects the members of Parliament, who can, in turn, overturn the leadership only if they dare. Real decisions were largely in the hands of party chieftains, but perhaps to some extent, the Crown, depending on the Monarch's shrewdness in distributing patronage among the party chieftains.

Across thousands of miles of dangerous ocean, the English colonies had changed from the weedy wilderness in the Sixteenth century, into thriving and prosperous small civilizations in the early Eighteenth. Transatlantic communication did not substantially improve in that interval, but colonial population grew to over a million, many of them native-born in the colonies, with increasingly large numbers of immigrants from other nations. Loyalty to the Monarch inevitably declined. True, they spoke English, revered England, but many urgent local issues were difficult to administer at such a distance, encouraging a mentality of self-governance. France, by now at war with England on the Continent, operated on a grand plan of interior encirclement, from Quebec and and Great Lakes, down the Mississippi to New Orleans. The English coastal settlers needed peace with the Indians of the interior;

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

the French did not scruple to stir up massacres and Indian warfare. All wars are expensive, the French and Indian war particularly so. After defeating the French, the British were put to the protracted expense of building frontier defenses. Although the British were anxious to attract English-speaking colonists who would defend America for England, it was obvious some of the settlers were becoming very rich. Surely these people could not object to paying taxes for their own defense. In retrospect, it seems remarkably naive of the British to think it was that easy. Americans did not want to pay taxes because they did not want to pay taxes. They settled on the stance of "No taxation without representation" and like Franklin and the Penn family, many really believed in it. That slogan was particularly effective after it became apparent that Parliament wasn't about to give remote colonists reciprocal power in Parliament to interfere with affairs in the British Isles. With Parliament adamantly refusing to dilute its own power, "No taxation without representation" was a neat rhetorical box which meant, "No taxation." Contemporary English historians now throw up their hands in despair that so few members of George III's government had Burke's vision or even the normal wiles of diplomacy. But that understates the hidden political agenda. Parliament just pushed ahead with fairly nominal taxes, but they did so to curtail the independence of colonial legislatures.

The Stamp Act of 1764. It could be argued that Navigation Acts nothing new; earlier versions were first passed in 1651, intended to thwart Dutch trading. They prohibited foreign trade with the British home islands. After fifty years in 1703 similar restraints were extended to trade with the colonies, particularly molasses in the Caribbean area. No outcry was made as these restraints, aimed at retaining the Britishness of British colonies, were occasionally modified and extended over the next sixty years.

|

| Thomas Penn |

After a century in 1764, however, the Stamp Act was passed, producing modest revenue but imposing a crippling set of headaches by requiring special papers to transact private business. The uproar was enormous and legitimate, focused mostly on the tangle of red tape needlessly imposed. By shifting taxation from trade to paperwork transactions, suspicions were plausible that the Ministry was scheming something obscure. The Stamp Act was hastily repealed, even before Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Penn recognized its unpopularity and were still to some extent defending it in 1766. Franklin apparently saw the Stamp Act as an opportunity to appoint his friends as stamp agents. Local uproar in Pennsylvania was apparently orchestrated by William Bradford, who in addition to having been Franklin's former competitor in the printing business, was the owner of the London Coffee House at Front and Market. No other prominent colonial leader seems to have been involved in the agitation, and it is remotely conceivable that uproar originated with Bradford alone. More likely, Bradford was merely an opportunist in a genuinely popular uprising. With the familiar maneuvering characteristic of politicians, Franklin took popular credit for defeating the Stamp Act with some skillful criticism of it, while John Penn gained credit with the King for representing Pennsylvania's relative calm about it, compared with other colonies. In Pennsylvania at least, the uproar quickly subsided after the repeal of the Act.

The Townshend Navigation Acts of 1768.In 1766 the Grenville Ministry was replaced by that of Rockingham, then soon by Pitt, who were anxious to disavow the unpopular Stamp Act, but nevertheless needed colonial revenue, and needed a few unpleasant laws to prove that Parliament could not be intimidated by colonial squawking.

|

| Charles Townshend |

Charles Townshend, the brilliant, vindictive, Chancellor of the Exchequer then proposed taxes on glass, painter's lead, paper, painter's colors, and tea. The underlying political purpose of these taxes was to provide revenue for paying British colonial administrators directly, rather than depend on the Colonial legislatures to pay them. The Legislatures had long played a game of withholding payments, sometimes even the salaries of Judges and Royal Governors, when they disapproved of projects devised in London. The very predictable uproar provoked by the Townshend Acts propelled John Dickinson into prominence with a pamphlet called Letters From a Pennsylvania Farmer, which popularized the idea of "nonimportation", essentially a boycott of British products. Unintentional nonimportation was in fact the effect of the laws, clogging the ports with paralyzed trade goods. Rather than Dickinson's lofty principles, a little-noticed act of 1764, prohibiting the printing of paper money, paralyzed trade. There simply was not enough available coinage to pay these taxes, which finally pushed the primitive transaction system beyond its capabilities. From the viewpoint of modern economics, a heavy unbalance between imports and exports could not be rebalanced by flows of capital. The disastrous Townshend Acts were mostly repealed in 1770, but the British government was getting in deeper and deeper, discrediting itself at every turn. To retreat but still save face, they repealed all the taxes except the one on tea.

The Tea Act of 1772. To a certain degree, the uproar over the face-saving tax modifications on tea was a pretext for confused but radical colonists who were spoiling for a fight about difficulties they tended to personalize. The act actually lowered the effective taxes on tea, and at first Whig radicals were hard put to find a reason for outrage about lowering the price of tea. However, Bradford and his London Coffee House cronies (Mifflin, Thomson) were imaginative, and soon stampeded a mob scene in Philadelphia, where for a time the populace had seen nothing to get worked up over. Rush and Dickinson joined the chorus; the public feeling was stirred to a frenzy not easily reversed.

The really substantive issues involved were created by several years of Townshend Duties and other forms of import restriction. Laws to ensure the Britishness of British colonies created pleasant opportunities for colonial artisans and craftsmen, difficult hardships for importers. But these dislocations, whether welcome or unwelcome, firmly exposed the underlying truth that they caused all colonists to pay higher prices for goods. Adam Smith was not to publish his Wealth of Nations until 1776, so in this case the proof preceded the theory. The colonists were effectively asked to pay higher prices for everything, in order to increase Britishness and to billet soldiers they could not command. Once that cat was out of the bag, attitudes could never be the same. On the English side of the ocean, the question was framed as colonist unwillingness to contribute to the cost of their own defenses. The two slanted perceptions hardened to the point where arrogance confronted defiance, suggesting combat to both of them.

In the case of tea, taxes and import restrictions were intended to promote English tea over Dutch tea; in fact, they stimulated smuggling. Smuggling grew to a point that vast quantities of tea were stranded in the warehouses of the British East India Company, and trade balances of the British Empire were undermined. By reducing taxes, Parliament made East India tea cheaper than smuggled tea. Going perhaps one step too far, middle-men in the tea import business were cut out of the loop by appointing favored direct agents. In Philadelphia, those were Henry Drinker and Thomas Wharton. Bradford and his group immediately set about intimidating these merchants with threats to burn them out, and the sea captains who worked for them, with threats of tar and feathers. The age of Reason was leaving Reason behind.

Poor Richard Plays Hardball

Several distinguished biographies of Benjamin Franklin have recently skirted his January 1774 confrontation with the British government in the "Cockpit" of Whitehall. Presumably, the exquisite details are too fancy and complicated for easy description, or possibly the cardinal significance of this intellectual duel is underestimated. It seems possible the American Revolution was declared by one man's making up his mind. A mind made up in one particular hour in one particular room, irrevocably, in front of the whole British Establishment.

The Archbishop of Canterbury was there, and so were Edmund Burke and Joseph Priestley. So were all the Privy Council, and most of British high society, giggling and hissing at his discomfort. Poor Richard stood there silent and impassive. The Enlightenment thought they were deciding his fate, but he was deciding theirs.

|

| Lord Alexander Wedderburn |

Franklin had published some letters he had promised not to publish, but they showed the British government in a very bad light. Alexander Wedderburn the Solicitor-General had deliberately orchestrated the meeting to shift the emphasis to Franklin's broken promise and away from British provocation of it. The room had been packed with highbrows promised a delicious treat, and Wedderburn's speech was meticulously planned as an entertainment for the intelligentsia. The man who discovered electricity was mocked as "conducting" the letters. And a famous man of letters was reminded that the ancient Athenians would brand three letters on the back of the hand of a thief: FUR, the name for a thief, an elaborate 18th Century pun making reference to fur hats and collars, which were the traditional symbol of printers. Wedderburn roused himself to the climactic announcement that the famous Roman, Plautus, had invented the famous derivative epithet, "Homo, triumph literarum," portentously meaning a three-letter man. The galleries of Whitehall tittered and applauded this thrilling attack. Franklin continued to stand, his face perfectly inscrutable to the end.

|

| Deplessis Portrait of Benjamin Franklin |

In his report back to the Massachusetts Legislature, Franklin used dismissive understatement to show he had not been asleep while he was impassive. He had been, he said, "the butt of his invective ribaldry for nearly an hour." After that, Poor Richard seemed to disappear from British society for nine months, seeing only close friends in his house, and then he sailed home to America, becoming a member of the Continental Congress the day he stepped off the boat. Meanwhile, he had arranged to have his portrait painted by Duplessis, the most distinguished painter in France, eventually to have it hang next to a painting by the same artist, of the King of France. To the original sketch for the portrait had been added a fur collar, the traditional emblem of the painter's guild. At the bottom, where a motto ordinarily would be found, was the single, three-letter Latin word, "VIR," or man, which would today be equivalent to he-man. And just so everyone would get the point, Franklin sent an otherwise anonymous letter to the newspapers, signed "Homo Triumph Literarum" in which he taunted that the friends of Mr. Franklin would have to agree he was a thief, as in the famous line of poetry that "He stole the lightning from the skies." But old Ben wasn't just bragging. Anticipating the baseball player Dizzy Dean by two hundred years, he was in effect saying "It ain't braggin' if you really have done it."

On Feb. 6, 1778 he and Silas Deane went over to the French palace to sign the Treaty of Alliance with the King of France. Instead of his usual brown suit, Franklin was wearing a faded blue one, and Deane questioned why he wore old clothes to such an important ceremony. "To give it a little revenge," was the answer. "I wore this suit on the day Wedderburn abused me at Whitehall." The true depth of Franklin's feelings would never have been known if Deane had not asked.

As a reminder, the Treaty they were signing said, "The essential and direct end of the present defensive alliance is to maintain effectually the liberty, sovereignty, and independence of the said United States. . . ." All in all, not a bad academic performance for a man who never went past the second grade in school.

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

Franklin Declares Independence a Year Early

Joseph Priestly became a close friend of Benjamin Franklin almost as soon as they met. Priestly was an Anglican clergyman who broke loose and formed the Unitarian Church, and meanwhile, his scientific discoveries also entitle him to be called the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, of course, was the discoverer of electricity; it would be hard to be sure which of the two was more brilliant. In July, 1775, Franklin wrote the following letter to Priestly, which makes a trenchant case that the American colonies should, and would, break away from England. Since some legal authorities, following Lincoln's lead, maintain that Jefferson's manifesto "informs" the United States Constitution, it might be well to begin referring to this letter as an even clearer statement of the mindset of America's founding leaders.

|

| General Thomas Gage |

" Dear Friend (wrote Franklin),

"The Congress met at a time when all minds were so exasperated by the perfidy of General Gage, and his attack on the country people (i.e. Of Lexington and Concord), that propositions of attempting an accommodation were not much relished; and it has been with difficulty that we have carried another humble petition to the crown, to give Britain one more chance, one opportunity more of recovering the friendship of the colonies; which however I think she has not sense enough to embrace, and so I conclude she has lost them forever.

"She has begun to burn our seaport towns; secure, I suppose, that we shall never be able to return the outrage in kind. She may doubtless destroy them all; but if she wishes to recover our commerce, are these the probable means? She must certainly be distracted; for no tradesman out of Bedlam ever thought of increasing the number of his customers by knocking them on the head; or of enabling them to pay their debts by burning their houses.

"If she wishes to have us subjects and that we should submit to her as our compound sovereign, she is now giving us such miserable specimens of her government, that we shall ever detest and avoid it, as a complication of robbery, murder, famine, fire, and pestilence.

"You will have heard before this reaches you, of the treacherous conduct to the remaining people in Boston, in detaining their goods, after stipulating to let them go out with their effects; on pretence that merchants goods were not effects; -- the defeat of a great body of his troops by the country people at Lexington; some other small advantages gained in skirmishes with their troops; and the action at Bunker's-hill, in which they were twice repulsed, and the third time gained a dear victory. Enough has happened, one would think, to convince your ministers that the Americans will fight and that this is a harder nut to crack than they imagined.

"We have not yet applied to any foreign power for assistance; nor offered our commerce for their friendship. Perhaps we never may: Yet it is natural to think of it if we are pressed.

"We have now an army on our establishment which still holds yours besieged.

"My time was never more fully employed. In the morning at 6, I am at the committee of safety, appointed by the assembly to put the province in a state of defense; which committee holds till near 9, when I am at the Congress, and that sits till after 4 in the afternoon. Both these bodies proceed with the greatest unanimity, and their meetings are well attended. It will scarce be credited in Britain that men can be as diligent with us from zeal for the public good, as with you for thousands per annum. -- Such is the difference between uncorrupted new states and corrupted old ones.

"Great frugality and great industry now become fashionable here: Gentlemen who used to entertain with two or three courses, pride themselves now in treating with simple beef and pudding. By these means, and the stoppage of our consumptive trade with Britain, we shall be better able to pay our voluntary taxes for the support of our troops. Our savings in the article of trade amount to near five million sterling per annum.

"I shall communicate your letter to Mr. Winthrop, but the camp is at Cambridge, and he has as little leisure for philosophy as myself. * * * Believe me ever, with sincere esteem, my dear friend, Yours most affectionately."

[Philadelphia, 7th July, 1775.]

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

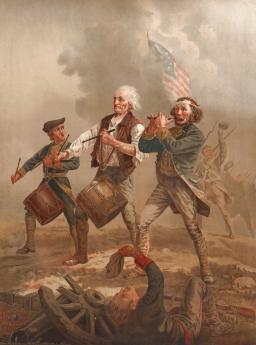

Philadelphia in '76

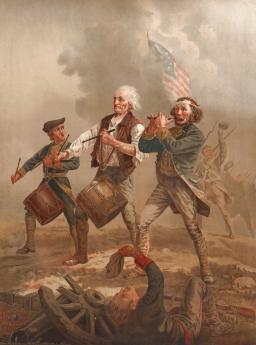

|

| Spirit of '76 |

Although the origins of the American Revolution are subtle and complex, even historically controversial, we have more or less united in the idea that we "declared" our independence from Britain on July 4, 1776. We then spent eight years convincing the British we were serious and have been independent ever since. Reflect, however, on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add to that the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had quite a nerve implying the whole thing was his idea. What's more, New England subsequently had to live with a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging the others along with it. It was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine.

New England was in the position of having started hostilities, and about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What the New Englanders wanted was WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing the dependency on the British homeland, without any sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. Perhaps it was unfortunate that New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming, and without support, New England was likely to be subdued like Carthage.

And then, the last hope for flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, stepped off the boat. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He finally was saying what others had been thinking. It was now, or never.

Tom Paine: Rabble-Rousing Quaker?

|

| Thomas Paine |

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was born of Quaker parents, which makes him a "birthright" Quaker. Children born into Quaker families are accustomed to the subtleties of speech and behavior of that religious sect, ultimately growing up to be the main nucleus of tradition. Knowing what they are getting into, however, they are more likely to rebel against it than others who, coming to the religion by choice rather than by birthright, are commonly described as "Convinced Friends."

These stereotypes may or may not explain some of Tom Paine's paradoxes. He certainly was not a pacifist, a quietest, or a plain person. He was an important historical figure; Walter A. McDougall, the famous University of Pennsylvania historian, feels the American colonists might have sputtered and complained about Royal rule for decades, except for Paine. The American Revolution happened when it happened because Tom Paine stirred up a storm.

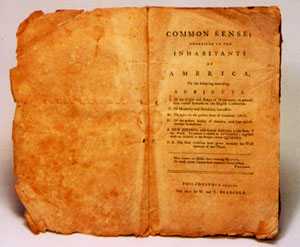

|

| Common Sense |

According to the traditional way of telling his story, Tom Paine was a ne'er do well failure in London. He ran into Benjamin Franklin, who advised him to emigrate to America in 1775, and within a year his pamphlet called ""Common Sense"" had sold 150,000 copies (some even claim 500,000), galvanizing the public and the Continental Congress into action on July 4, 1776. George Washington read Paine's writings to his troops on the eve of the Battle of Trenton. After that, Paine got mixed up with the French Revolution, and apparently became a severe alcoholic, proclaiming atheism all the way. Although Thomas Jefferson remained friendly to the end, Benjamin Franklin essentially told him to go leave him alone, and Washington would cross the street to avoid him. According to the usual line, Tom Paine was a big-mouthed rabble-rouser and a drunk, who traveled the world looking to stir up revolutions.