Related Topics

Benjamin Franklin

A collection of Benjamin Franklin tidbits that relate Philadelphia's revolutionary prelate to his moving around the city, the colonies, and the world.

Franklin Inn Club

Hidden in a back alley near the theaters, this little club is the center of the City's literary circle. It enjoys outstanding food in surroundings which suggest Samuel Johnson's club in London.

Cultural

Culture and Traditions (2)

Benjamin Franklin, Prophet

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Judged by his public and private writings, Franklin was a deist. That is, he believed God sort of wound up the Universe like a clock, then let it run by itself. Furthermore, the Constitution0 which he had a hand in writing, pretty clearly maintains a wide separation between church and state. Nevertheless, historians by the droves have identified a uniquely American culture, apparently based on some fiercely held convictions. We might just as well say America has a secular religion with prophets, and Benjamin Franklin was an early prophet. His enduring message for all time was: Honesty is the best policy.

By this he did not mean, as lawyers do, strict word precision, or as our military academies add, resolute avoidance of half-truths and double-talk. Ol' Ben never admitted who the mother of his illegitimate son was, and positively chortled at hoodwinking the Pennsylvania Assembly into matching private contributions for the nation's first hospital, which he secretly knew he already had in hand. Late in life, he set enduring standards for the American diplomatic service, which some have defined as a profession dedicated to lying for your Country. Not only was Franklin rather sly, he gleefully projected the image of slyness. In recent years, some historians have proposed his adventures with many women were just acting out a playful pose. Frankly, this suggestion is hard to accept.

|

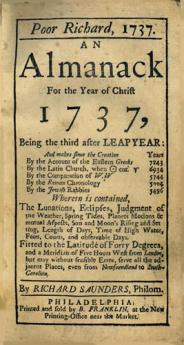

| Poor Richard Almanack |

The author of Poor Richard's Almanack, aged 26 at the first edition, was a young man totally consumed with advancing himself in the world; at that stage, he defined himself as a businessman. Like J. Pierpont Morgan, who could thunder "I will never do business with a man I don't trust", Franklin had one set of principles for business and another for love. Or, if you please, one set for men, and another for women, who were thought to play by their own set of rules. Historians have struggled with this paradox or hypocrisy, but it would have seemed strange even to comment on it in Franklin's era, and a conflict is not suggested in eighty volumes of his life writings. Lord Byron, another famous philanderer of the day, stated the matter delicately as "Man's love is to man's life a thing apart; 'this woman's whole existence." And that was just the way it was, in their view.

Franklin, who as an escaped apprentice might well have been punished like a felon in Boston, came to the big town to make his fortune, found himself ina culture of Quakers. Boston Puritans might well have punished him severely, or at least stood by approvingly while his brother beat the daylights out of him. The Dutch in New York were well known as rough customers; just to the south in Delaware, the inhabitants were to maintain a whipping post for two hundred more years. But in Philadelphia, non-violence was eventually carried to the extreme of confining miscreants to solitude until they spontaneously perceived it really was better to behave. Poor Richard's little motto about the best policy was in fact just the Golden Rule, applied to business. Even today, anyone starting a business soon finds a discouraging number of people ready to cheat the businessman; it was even truer in colonial America. Somehow, if you enter the business world, it is to be assumed you are ready to defend yourself. Competitors have little respect if you fail to conduct business warily; even less if you complain and wiper. Although many women have conducted successful businesses, it is so to speak a man's world. Little Benny Franklin, fresh off the boat from Boston, watched with amazement as Quaker merchants and vendors conducted trade on the assumption the counterparty was honest, refused to bargain an openly set price, and avoided violence when cheated. At the same time, Franklin could not fail to notice that Philadelphia was prospering much more rapidly than Boston. After a business trip to England, he could see that London worked at the same disadvantage as Boston. Honesty, it would appear, makes you rich; cheating may sometimes work, but fairness gets you ahead more steadily.

In later years, Franklin shared rooms with John Adams, who became positively livid at the suggestion a person should be honest for any other motive than to be taken into Heaven. It was degrading, even dishonest, to be honest in order to get rich. There is no evidence that Franklin's reaction to this sermon was anything but contempt for the other man's intelligence. Although probably not directly related to this exchange, Franklin's assessment of Adams was "always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes and in some things, absolutely out of his senses." Ben Franklin was born in Puritan Boston, fled from it as soon as he could, and thereafter seldom regarded Puritans as having two feet on the ground.

It thus emerges that Benjamin Franklin who was certainly no pacifist, greatly admired Quakers. On the one hand, in desperation he organized Pennsylvania's first militia when in 1730 the Quaker Pennsylvania government refused to act against French and Spanish marauders in Delaware Bay, and in 1752 took the lead again in assisting the British against Fort Deliquesce during the French and Indian War while Quakers resigned from government rather than defend the state. He even volunteered to go to London to lobby against the Penn family. None the less, Franklin was completely converted to Quaker principles of doing business, perceiving a deep underlying truth to them. Honesty, as suggested by the Golden Rule, or fair trade as they say in commerce, is the key to prosperity. Honesty is not just good advice for a young man, it is a principle which brings prosperity to a whole nation, while readily suggesting a clear simple explanation of why it should. Don't you want to be rich? Plenty of other people want to be rich.

Unfortunately, many kings, barons, confidence men, bullies, cheaters, and tough guys have also become rich. Generations of immigrants have come to our shores with the idea that life is a zero-sum game. The way to get money is to take it from someone else. The way to lose money is to give a sucker an even break. But gradually, one generation after another learns the truth, as enunciated by Poor Richard, that everybody is better off if almost everybody tries to be honest.

Surely it is not too much to say that American adventurism in the rest of the world reflects exasperation that the rest don't get the point. Certain parts of Europe, and all of the Mideast, really doubt it will work for them. The Far East does seem to grasp the rudiments, although with inscrutability and all it's hard to be certain. It isn't even true that all Americans get the point, but we have a containment policy for them, based on the fragile belief that here we outnumber the zero-summers. You must be firm, but you must also be fair. The crippled old Franklin hobbled out the door of Independence Hall after the Constitutional Convention. A woman calling to him asked what sort of government had been given us. "A republic," he answered. "If you can keep it."

Originally published: Wednesday, September 09, 2009; most-recently modified: Friday, September 20, 2019