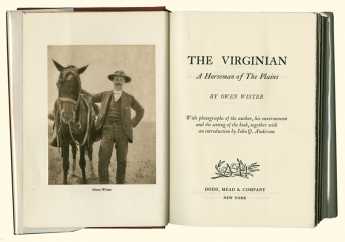

2 Volumes

Constitutional Era

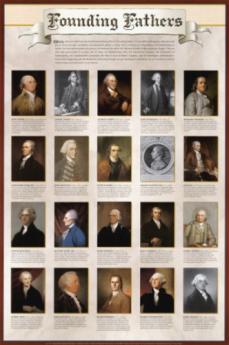

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

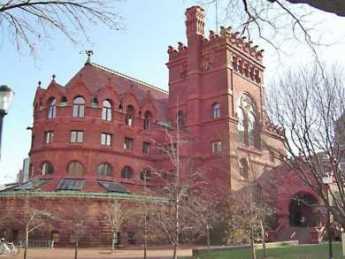

Franklin Inn Club

Hidden in a back alley near the theaters, this little club is the center of the City's literary circle. It enjoys outstanding food in surroundings which suggest Samuel Johnson's club in London.

The Franklin Inn

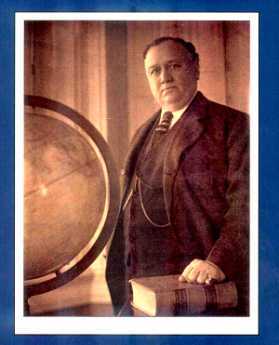

Founded by S. Weir Mitchell as a literary society, this little club hidden on Camac Street has been the center of Philadelphia's literary life.

|

Camac Street is a little alley running parallel to 12th and 13th Streets, and in their day the little houses there have had some pretty colorful occupants. The three blocks between Walnut and Pine Streets became known as the street of clubs, although during Prohibition they had related activities, and before that housed other adventuresome occupations. In a sense, this section of Camac Street is in the heart of the theater district, with the Forrest and Walnut Theaters around the corner on Walnut Street, and several other theaters plus the Academy of Music nearby on Broad Street. On the corner of Camac and Locust was once the Princeton Club, now an elegant French Restaurant, and just across Locust Street from it was once the Celebrity Club. The Celebrity club was once owned by the famous dancer Lillian Reis, about whom much has been written in a circumspect tone, because she once successfully sued the Saturday Evening Post for a million dollars for defaming her good name.

|

| The Franklin Inn |

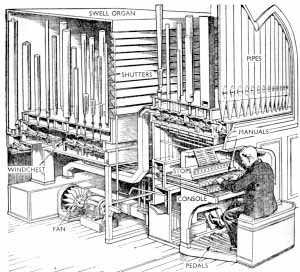

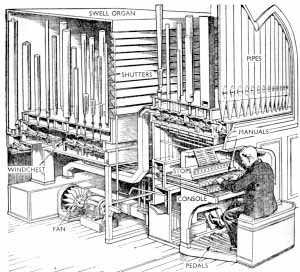

Camac between Locust and Walnut is paved with wooden blocks instead of cobblestones because horses' hooves make less noise that way. The unpleasant fact of this usage is that horses tend to wet down the street, and in hot weather you know they have been there. Along this section of narrow street, where you can hardly notice it until you are right in front, is the Franklin Inn. The famous architect William Washburn has inspected the basement and bearing walls, and reports that the present Inn building is really a collection of several -- no more than six -- buildings. Inside, it looks like an 18th Century coffee house; most members would be pleased to hear the remark that it looks like Dr. Samuel Johnson's famous conversational club in London. The walls are covered with pictures of famous former members, a great many of the cartoon caricatures by other members. There are also hundreds or even thousands of books in glass bookcases. This is a literary society, over a century old, and its membership committee used to require a prospective member to offer one of his books for inspection, and now merely urges donations of books by the author-members. Since almost any Philadelphia writer of any stature was a member of this club, its library represents a collection of just about everything Philadelphia produced during the 20th Century. Ross & Perry, Publishers has brought out a book containing the entire catalog produced by David Holmes, bound in Ben Franklin's personal colors, which happen to be gold and maroon, just like the club tie.

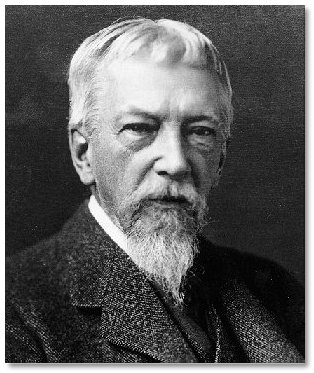

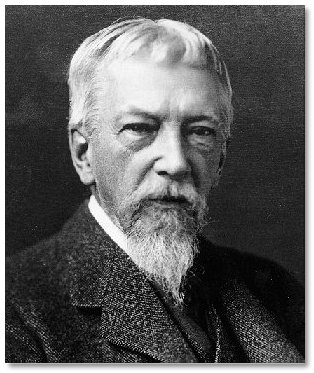

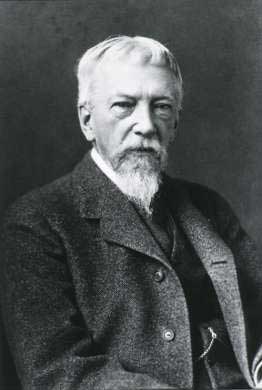

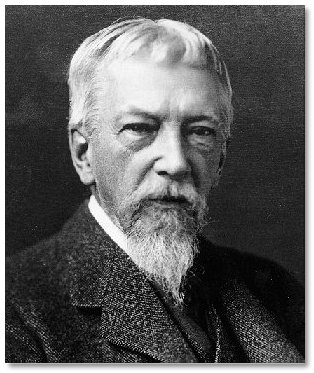

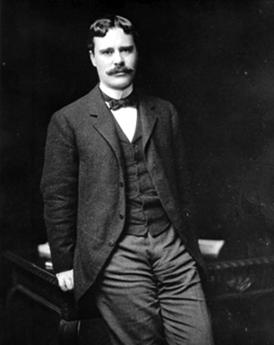

The club was founded by S. Weir Mitchell, who lived and practiced Medicine nearby. Mitchell had a famous feud with Jefferson Medical College two blocks away, and that probably accounts for his writing a rule that books on medical topics were not acceptable offerings from a prospective member of the club. So there.

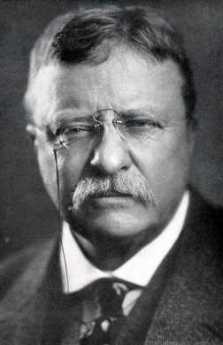

The club has daily lunch, with argument, at long tables, and weekly round table discussions with an invited speaker. Once a month there is an evening speaker at a club dinner, with the rule that the speaker must be a member of the club. Once a year, on Benjamin Franklin's birthday, the club holds an annual meeting and formal dinner. At that dinner, the custom has been for members to give toasts to three people, all doctors, including Dr. Franklin, Some sample toasts follow: Benjamin Franklin's formal education ended with the second grade, but he must now be acknowledged as one of the most erudite men of his age. He liked to be called Doctor Franklin, although he had no medical training. He was given an honorary degree of Master of Arts by Harvard and Yale, and honorary doctorates by St.Andrew and Oxford. It is unfortunate that in our day, an honorary degree has degraded to something colleges give to wealthy alumni, or visiting politicians, or some celebrity who will fill the seats at an otherwise boring commencement ceremony. In Franklin's day, an honorary degree was awarded for significant achievements. It was far more prestigious than an earned degree, which merely signified adequate preparation for potential later achievement. And then, there is another subtlety of academic jostling. Physicians generally want to be addressed as Doctor, as a way of emphasizing that theirs is the older of the two learned professions. A good many PhDs respond by rejecting the title, as a way of sniffing they have no need to be impostors. In England, moreover, surgeons deliberately renounce the title, for reasons they will have to explain themselves. Franklin turned this credential foolishness on its head. Having gone no further than the second grade, he invented bifocal glasses. He invented the rubber catheter. He founded the first hospital in the country, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and he donated the books for it to create the first medical library in the country. Until the Civil war, that particular library was the largest medical library in America. Franklin wrote extensively about gout, the causes of lead poisoning and the origins of the common cold. By inventing bar soap, it could be claimed he saved more lives from the infectious disease than antibiotics have. It would be hard to find anyone with either an M.D. degree or a Ph.D. degree, then or now, who displayed such impressive scientific medical credentials, without earning -- any credentials at all. Benjamin Franklin for whom we are named, was after all a club man. In his London years every Thursday he attended the Club of Honest Whigs, and every Monday a coffeehouse called the George and Vulture. His conviviality is part of my theme, but especially his congeniality with women. Scientist and statesman, of course. We nod to bifocals, lightning rod, storage batteries, daylight savings time, less smoky stoves, and a flexible urinary catheter (which he commissioned for his ailing brother from a Philadelphia silversmith). We bow to lending libraries, fire brigades, insurance associations, planned giving, philosophical society, and legislatures. Above all, he helped to design and invent the United States of America, and by example, to inspire the free and mobile society that inhabits our states. But tonight I celebrate his relationships with and his treatment of women. Let me dispose at once of an image of him as young playboy or old lecher. He was always responsible in his relationships. He acknowledged and raised his illegitimate son William (who as royal governor of New Jersey, loyal to the Crown, split with his father). He helped to raise and educate Temple Franklin, the bastard son of his bastard son, who stayed loyal to him as grandfather. His 44-year common law marriage with Deborah Read (an abandoned wife of another man) was a tender and practical bond. She bore two children and managed his print house and bookkeeping. She was half-literate and afraid of the ocean, and so may be thought to have been spared the high politics and intellectual life of England and France. In his duties overseas, Franklin was absent fifteen of the last seventeen years of her life. When she wrote him about rumors of other women, he answered, ".while I have my senses, and God vouchsafe me his protection, I shall do nothing unworthy the character of an honest man, and one that loves his family." His best biographers find nothing to stain his promise to Deborah. That is not to say that he lacked interesting friendships with other women. Four long and intense ones are worth special mention: one American, one English, and two French. Katie Ray was the first of his romantic "but probably never consummated flirtations." When they met, he was 48, she 28. Over the course of their lives, they exchanged more than 40 letters. He "made a few playful advances that [she] gently deflated." Claude-Anne Lopez describes the kind of bond he established, first with Katie, as "somewhat risque, somewhat avuncular, taking a bold step forward and an ironic step backward, implying that he is tempted as a man but respectful as a friend." She uses a French term for this --amitie amoureuse-- a little beyond the platonic, but short of the grand passion." Such a loving friendship he also had with Polly Stevenson. He was 51 when he met her; she, 18. Her intellectual quotient was high, like Katie, and he talked science with her. They exchanged 130 letters. She, as a widow, was at his deathbed 33 years later. Charles Wilson Peale came upon Franklin one day in London, and later sketched what he saw: sitting with a young lady on his knee. She is thought to be Polly. But we should not treat that as a tabloid photo. He was sincere in urging Polly to raise a family rather than pursue more learning. There is nothing as important "as being a good parent, a good child, a good husband, or wife." In Paris, as Ambassador to France, 1776-85, Franklin found two more mistresses of mind and soul. Mme. Anne-Louise Brillon was a famous harpsichordist and a supporter of the American Revolution. When they met, she was 33 and married; he 71 and a widower. In an eight-year relationship, he sent her 29 letters; she to him, 103. She finally turned aside his inquiries about a more corporeal relationship. But she wrote with affection that he demonstrated "a droll roguishness which shows that the wisest of men allows his wisdom to be perpetually broken against the rocks of femininity." Mme. Anne-Catherine Helvetius was a lively and beautiful widow near 60 when she met Franklin at age 73. He eventually went beyond the bounds of his usual dance between sincerity and self-deprecating playfulness. He ardently proposed marriage to her. She found this entreaty a bit wearying. But when in the winter of 1785 he finally departed France, she was there, visiting his home. So was Mme. Brillon; as well as Polly Stevenson and her three children; altogether a splendid "network of good will" with himself at the center. Jefferson, his friend, and successor in Paris noted on his last day before sailing that the ladies were smothering him with embraces. He told Franklin that as well as the duties transferred to him, he wished to have those privileges as well. But Franklin answered: "You are too young a man." Sisters and brothers of the Franklin Inn'let us toast Benjamin Franklin: his constancy with his wife, his well-contained passion, his well-expressed wit, his amitie amoureuse. May his example of loving friendship enfold and inspire the members of our club named for him. -- Theodore Friend At the Annual Dinner of the Franklin Inn Club Philadelphia, 18 January 2008 Based on: Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York, 2003) Edmund S. Morgan, Benjamin Franklin (New Haven, 2002) Claude-Anne Lopez, Mon Cher Papa: Franklin and the Ladies of Paris (2nd ed., New Haven, 1990; 1st ed., 1966) JWilliam White left a legacy to the Franklin Inn, the income from which was to pay for an annual dinner, with all the trimmings. Good as its word, the Inn holds the J. William White dinner every year on Benjamin Franklin's birthday, although inflation and fluctuations of the stock market require it to make a modest charge for attendance. White also created the J. William White Professorship in Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, a chair which was once occupied by Jonathan Rhoads. These trust-fund memorials do little to convey the wild and glamorous image of Bill White. White was a member of the First City Troop and fought the last known honest-to-goodness duel on Philadelphia's field of honor (in the accidental "wedge" of disputed land between Delaware and Pennsylvania). The right and wrong of the argument about wearing the City Troop uniform are in dispute, but the details boiled down to White at the critical moment raising his gun to the sky and firing at the stars. That it was not a meaningless gesture was then brought out by his opponent ( a fellow Trooper named Adams) taking slow and deadly aim -- but missing him. White was an academic in the sense that he was the first, unpaid, Professor of Physical Culture at the University of Pennsylvania. Active in the Mask and Wig Club, he was a chief surgeon at Philadelphia General Hospital, chief surgeon to the Philadelphia Police, and chief surgeon to the Pennsylvania Rail Road. He is the surgeon actually operating in Thomas Eakins' Agnew Clinic, while Agnew himself stands as the "rainmaker", to use a term from legal circles. He was Chairman of the Fairmount Park Commission, and numerous other positions where political contact was more important than surgical skill. When World War I came along, he was off to France with the University of Pennsylvania Hospital Unit, writing two books with Theodore Roosevelt. Although his friendship with Henry James suggests greater literary talent, he was supportive of Adams' transfer of citizenship in protest of America's staying out of World War I; but nonetheless, Roosevelt published more than thirty books. What emerges from the history of Bill White is flamboyance and lots and lots of unfettered energy. He might feel a little out of place at one of his endowed dinners today, but he was probably always a little out of place in any company -- and didn't care a whit. REFERENCES Silas Weir Mitchell lived to be an old man during the Nineteenth Century when it was unusual to get very old. He was an important part of both the Philadelphia medical scene and the literary one. He became known as the Father of American Neurology as a published studies of nerve injuries caused by the Civil War. He published about 150 scientific papers, including famous investigations of the neurological effects of rattlesnake venom. His most famous medical treatment was the "rest cure" for hysteria, while his most enduring scientific discovery was the phenomenon of causalgia. He despised Freud, and psychonanalysis. No doubt the feeling was mutual, but the passage of time has tended to favor Mitchell more than Freud. The central role of sex is the essence of Freud's viewpoint, while Mitchell is summarized in the remark that, "those who do not know sick women, do not know women."Struggling medical students can take heart from the well-documented fact that Mitchell applied to the Pennsylvania Hospital for an internship, and was rejected. Upset by the experience, he toured Europe for a year and applied again. He was again rejected. He later applied for the faculty at Jefferson and was rejected, but his reaction to that was one of rage and vengeance. Just what these two episodes out of Philadelphia medical politics really mean, remains to be clarified by Mitchell's biographers. Mitchell's second career was literary, publishing 12 novels and 5 books of poetry. He is honored as the founder of the Franklin Inn Club, for century home to every important literary figure in Philadelphia. It is striking that he selected Benjamin Franklin as the guiding star of the Inn since Franklin similarly was eminent in both science and culture, and an ornament to conversation and society. In a pacifist Quaker City, both men approved of combat, and his novel about Hugh Wynne stresses that his hero was a "Free Quaker, meaning one who fought in the Revolution. Because of his strong Republican views, he was never made a professor at the local medical school. Mitchell's patient Andrew Carnegie donated the funds to build a new building for the College of Physicians when Mitchell was its President. When Mitchell was president of the Franklin Inn, Carnegie wrote him, asking for suggestions about donating a small sum, say five or ten million, and asking where it should go. That was the Inn's big chance, all right, but somehow it failed the test. Mitchell suggested that the money be given to raise the salaries of college professors, thus perhaps suggesting that this veteran of many academic revolts did eventually soften his views. Who was Dr. J. William White, and why do we drink a toast to him every year at our Annual Meeting? I will answer my second question first: Dr. J. William White died on April 24, 1916, leaving a Will that he finally signed only on March 24 of that year. The Will, drafted by John G. Johnson, the most famous Philadelphia lawyer of that time, runs to 26 pages and disposes of an estate of $868,176.05,--which was real money in 1916. Item 17 of that Will reads as follows: "I give to the Franklin Inn Club of Philadelphia five of its bonds of $100 each to me belonging. IN ADDITION TO THIS, I give to said Club the sum of $5,000 to be invested by the Directors of the Club, with the approval of the majority of the membership, and the income to be expensed in such way as will best subserve the interests of the Club and conduce to its perpetuation. I will be glad if, in doing this, they can assure the occasional remembrance of my name. The Club has been of me the source of so much pleasure and happiness that I feel that I owe it something in return." Well, I have not examined the minutes of our Board to see if it really was discussed and voted upon by a majority of the members, but when I joined in 1968, I was told that Dr. White's bequest had been used for this annual dinner in his memory as long as there was money to pay for it, then only to buy the champagne for the toast to his memory, and then in my time even the champagne money was drunk up. We still talk about him. He was in every sense a "character", a special Philadelphia character. A lot of this information comes from a biography his friend Agnes Repplier published in 1991. J. William White's father James William White Senior was a doctor, the founder of Womens' Maternity Hospital, and President of the S.S. White Dental Supply Company, an extremely successful business which operated until recently from a big building just down there on 12th Street. The Money that flowed from this business enabled our Dr. J. William White to do pretty much what he wanted all of his life. He was a very smart boy, strong, and with a bad temper. He got into fights at school, but he also managed to earn both an MD and Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1871, at the age of 21. He maintained a passionate loyalty to Penn all of his life. Directly after graduation, he obtained a job on a U.S. Coastal Survey ship, theHassler on a survey of marine life and ocean bottoms conducted by Professor Louis Aggassiz of Harvard. He was hired as a "Hydrographic Draughtsman" but it turned out he was to be the expedition photographer and film developer because nobody else knew how to do that. Before they sailed, he also wangled a job as correspondent for The New York Herald. They sailed from Boston in December 1871, explored their way around South America and arrived in San Francisco in August of 1872. On his way home by train, young Dr. White stopped in Salt Lake City to hear Bringham Young preach. Bringham Young preached against doctors and lawyers, and told the women in his audience that they should not employ obstetricians, that they and their babies would be better off without them. When Dr. White returned to Philadelphia, he went to work, first as a resident at Philadelphia General Hospital, then a doctor for Eastern State Penitentiary, where he apparently lived for a while, where he took boxing lessons from a giant prisoner. By 1876 he was an Assistant Demonstrator of Practical Surgery at Penn, and a couple of years later he was working under the most prominent Philadelphia surgeon Dr. D. Hayes Agnew. In Thomas Eakins' famous painting "Dr. Agnew in his Clinic" we can see Dr. White doing the actual cutting, while Dr. Agnew is giving the lecture. This picture is also interesting because right there in the middle of the action is a stalwart female, the surgical nurse. By the time of this picture, both Drs White and Agnew were having trouble with the Board of Governors: female students were complaining that they were not allowed into these clinics. Drs Agnew and White replied that "the nature of the diseases and the conditions of the patients made the presence of females undesirable." The doctors offered to quit and the Governors apparently backed down. But what about that nurse? Another famous story: In 1877 Dr. White was elected to the First City Troop . For some reason, this didn't look right for a young doctor, because in these long years between wars, the Troop was known more for parties, banquets, and balls than for national defense. However, he joined, enjoyed the parties and the riding. Previous Troop surgeons had worn regular street clothes; Dr. White put on the fancy Troop uniform. Probably at a party, a Trooper named Adams objected, became loud. Dr. White floored him. Mr. Adams sent a formal challenge to a duel. Sensation! Nobody could remember a duel in Philadelphia, where it was against the law. The newspapers were in an uproar, the New York Herald, for which Dr. White once wrote letters from his voyage around South America, invented a story about a lady who was supposed to be the real cause of the fight. Mr. Adams and Dr. White, accompanied by seconds and a surgeon, crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, took single shots at each, shook hands and went home. Dr. White shot into the air. Years later, Adams confessed that he had aimed at Dr. White, but missed. Eventually, the storm blew over, but it is remembered as the last duel around here -- as far as I Know. As to the City Troop, Dr. White's Will left $5,000 in Trust for a "J. William White Fund, the income to keep remembrance of the facts that I served as Surgeon and was the first incumbent of that position to be directed by the Troop to wear the time-honored full dress uniform." I don't know if the Troop bought champagne to keep remembrance. Although Dr. White became one of the best surgeons here, and wrote several successful textbooks, he is mainly remembered for his passion for athletics. He was made the first Director of Athletics at Penn. He built the first Gymnasium, he built Franklin Field, he arranged for Army-Navy Games to be played here, he got his friend Theodore Roosevelt to attend, he spent every summer either climbing the Rockies or climbing the Alps together with his very sporting and strong wife, Letitia. Letitia was also a better shot than her husband. Perhaps Dr. White's most famous sport was called "Angling for Men". He learned this sport on vacation in Narragansett Bay. The players are in a rowboat, and the contestant jumps into the water, with a strong rope tied around his waist. The Men in the boat try to haul the Swimmer back into the boat, while he resists. When Dr. White was 46 years old it took three of his friends 38 minutes to get him back within 100 feet of the boat, but they never got him in! Dr. White moved in very exalted circles. Among his close friends were Henry James, whom he visited in Rye and who lived with the White's on his visits to Philadelphia: John Singer Sargent, whom Dr. White persuaded to paint his portrait although Sargent had given up portraits; and the famous English doctors Sir Frederick Treves and Sir Joseph Lister, and as I said, President Theodore Roosevelt. In later years, after retiring from regular surgery, Dr. and Mrs. White traveled all over the world, although some patients including John G. Johnson insisted that only Dr, White could do any procedures upon their own bodies! Well, of course, Dr. White had his own problems, and like all men, became a patient himself. In 1906, he developed a hard nodular mass in his left iliac fossa which, I gather, is not good. Probably cancer. He knew what to do. He took a train Rochester, Minn. To his friends the Mayo Brothers. When they decided to operate, three top surgeons from Penn went out to watch. Dr. William J. Mayo operated and successfully removed congenital diverticulitis which had caused a perforation of the bowel. Later: Dr. Mayo: "Well, you're all right." Dr. White "Well, you're a good liar. I've been there myself, and I know." Dr. Mayo: You don't know everything. It's like a bag full of black beans, and one white bean. You pull out the white one. Now get well!" By next summer he was well and traveling again. He received a degree from University of Aberdeen, he met Thomas Hardy, he went to Egypt, next year to China, when the First World War began he was passionately pro-Allies, visited friends in London, visited wounded soldiers at the American Ambulance Hospital in Paris, spent much time there but did not operate, flew over the battlefields in a French military plane, and visited Reims during a German bombardment. He visited the British front, returned to London, involved himself in the issue of Henry James becoming a British citizen because of America's Neutrality, then sailed home across an ocean full of U-Boats. Back in Philadelphia - actually on his estate in Delaware County he raised money for the American Hospital in Paris, and again involved himself in several disputes, about the War, about a Penn faculty member...but now he was dying, we're not clear from what, but it sounds like cancer, after all. He was in great pain and had to be hospitalized. He died in his beloved University Hospital, surrounded by colleagues and friends, on April 24, 1916. I close with a few more words about his Will. As I said, it is 26 legal-size pages, really the story of a life, packed with bequests to every person who was close to him, every organization he belonged to-- and most of them, like the one to us here at the Inn, ask that something be done to remember J. William White, which seems --to me -- little sad. Why were this popular, successful men so afraid of being forgotten? Was it because he and his wife had no children? I don't know, but here, tonight, we remember: I raise my glass-- champagne or not--to the memory of Dr. J. William White, a character if there ever was one! ------given at the Franklin Inn Club on January 14, 2005, by Arthur R. G. Solmssen An address by Arthur Hobson Quinn at the J. William White Dinner on January 17,1952, commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the founding of the Franklin Inn Club. The Founders: Edward W. Bok, Cyrus Townsend Brady, Edward Brooks, Charles Heber Clark, Henry T. Coates, John Hornor Coates, John Habberton, Alfred C. Lambdin, Craige Lippincott, J. Bertram Lippincott, John Luther Long, Lisle De Vaux Matthewman, John K. Mitchell, S. Weir Mitchell, Harrison S. Morris, Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Arthur Hobson Quinn, Joseph G. Rosengarten, Charles C. Shoemaker, Solomon Solis-Cohen, Frederick William Unger, Francis Chruchhill Willams, Francis Howard Williams It is a somewhat lonely eminence in which I find myself. That I am the only living founder of the Inn is due simply to the accolade of chronology -I have been able to survive the others! May I take this opportunity to thank the Inn for creating me the first honorary member? My association with it has been purely one of enjoyment; I have never held an Office, and except for membership on Entertainment Committee, I have done little to serve the Inn. It has not been because of any lack of affection. The founding of the Inn was due to some intangible and some concrete impulses. The turn of the century was responsible for many new movements and it is heartbreaking now, to those of us who were young at the time, to remember how we welcomed the dawn of what we were sure would be better days. Centering in Philadelphia, there were at that time an unusual number of men of distinction as creators of literature. Weir Mitchell had written in Hugh Wynnethe greatest novel of the Revolution, and in his Characteristics had created the novel of psychology. Horace Howard Furness, Senior, had won eminence with his Variorum Shakespeare. Henry Charles Lea was producing his histories of the institutions of the Middle Ages. John Bach McMaster had just published the fifth volume of his great History of the People of the United States. John Luther Long had just created the Character of Madame Butterfly, to become a world figure. Langdon Mitchell had won a triumph with his play of Becky Sharp. Owen Wister had scored a popular success with The Virginian, a romance with a theatrical flavor appropriate to the grandson of Fanny Kemble, and while Charles Heber Clark was trying to forget that as Max Adeler he had delighted thousands with his humor, Out of the Hurly-Burly was not forgotten . I can still remember the day when he remarked dryly, "I can not bring myself to read these books written by other people." It should be a matter of pride to us that it was in this creative atmosphere that the Inn was born. All the writers I have mentioned were members of the Inn, and although their participation in our activities varied, their fellowship was an inspiration. I owe to Karl Miller's great statistical ability and keen interest in the Inn some figures which show that of the fifty-one members who joined in 1902, forty-four were then of later listed in Who's Who in America. It was a noteworthy group. As long as I have been selected as the "authority" on the foundation, here is the result of my memories and my research, aided greatly by the labors of the Secretary, William Shepard. For the record, then, the concrete sources were follows: On February 19, 1902, ten men meet at the University Club, drew up a preliminary draft of a constitution and signed a Call for the formation of an "Authors' Club." In our printed booklet of 1950, the statement is made that Dr. Mitchell was present. I see no evidence that he was there, for he did not sign the Call. The account is in the handwriting of Francis Churchill Williams, the first secretary, and it is clear that Dr. Mitchell was elected President in his absence. It is interesting that of the ten signers of the call, J. Bertram Lippincott, John Luther Long, William J. Nicolls, Harrison Morris, and Craige Lippincott remained members of the Inn until their death; that Francis Howard Williams became Vice-President and Churchill Williams was the most active force in the actual organization of the Inn. While Weir Mitchell was not the actual founder, he became the inspiration, the creator of the spirit of the Inn. While he did not belong to any organized preliminary group, his home was the center of gatherings which met there on Saturday evenings after nine o'clock to listen to what he truly described as "the best talk in Philadelphia," and these gatherings were certainly one of the indirect sources of the Inn. Many of his guests joined the Inn, and while I was a guest only after the Inn was founded, I am sure there must have been discussion of such a club. Another concrete source was the Write about Club, a small group of men founded in 1897 and still in existence, who met weekly and read stories and verse for the criticism of their fellows. Among this group were Churchy Williams, who joined it with the idea of turning it into a club such as the Inn became, but found this impracticable; Charles C. Shoemaker, a publisher, for thirty-four years Treasurer of the Inn, needed the money ; Edward Robins, a short story writer; Edward W. Mumford, who became president of the Inn and did great service at the time of temporary low water; Rupert Holland, a director, and still a member of the Inn, and Lawrence Dudley, for many years the active chairman of the Entertainment Committee. The relations of these two clubs were mutual, Dudley and John Haney were first members of the Inn and later joined the Write about Club. Robins, Williams, Shoemaker, and I were first members of the Write about Club and were elected members of the Inn at its foundations. To return to actual meetings of the Inn. Dr. Mitchell did preside at the meeting held at the Art Club on March 4, 1902, when the scope and purpose of the Club were definitely settled. Thirty-two or Thirty-three men were present. The Name of the Club was the subject of heated discussion. Dr. Mitchell objected to the proposed name "Authors' Club." He remarked that the "Authors' Club." in New York was one of the dullest place he has ever visited, and some years later, I was able to confirm his opinion. Another heated discussion as to qualifications was crystallized by the decision that the Club should be founded upon "the book, its creator, its illustrators and its publisher," who made the book available. The undated minutes of the next meeting tells us that the name "Franklin Head" and three for "Authors' Club." I have among my own memorabilia a notice which reads, "A first meeting of the Franklin Inn Club will be held at the Club House, 1218 Chancellor St., at eight, Wednesday evening June 4, 1902." I also find in my scrapbook an invitation reading, "The President of the Franklin Inn Club desires to say that the dinner you have done him the honor to accept will be at the Club House at seven, punctually, on January 6, 1903." It will be noticed that although some of us have made it a point to say "Franklin Inn" without the "Club," the earliest notices were inclusive of that word. The names of the diners are recorded in a framed manuscript, hung on the wall in an inconspicuous place; it should have a more dignified position, for it was the first of these dinners, of which this is the fiftieth. Thirty-six names are immortalized there, signifying the Club's willingness to accept an invitation to good dinner. Dr. Mitchell's presiding was, of course, the feature of any dinner. When he died in 1914 it was impossible to replace him, the resulting election for president tore the Inn in two. I wish to take this opportunity to pay a tribute not only to the first president of the Inn but to the man himself and to the great novelist. He was always willing to help younger writers and great novelist. He was willing to help younger writers, and I owe to his friendship introductions to men like William Dean Howells and others which aided me greatly in my work in American Literature. He was a patrician, as George Meredith recognized when he, in commenting on Dr. Mitchell's Roland Blake, Which he had read three times said, "It has a kind of nobility about it." He imparted this quality to his characters from Hugh Wynne down to Francois, the thief of the French Revolution they too are patricians. They do not argue about caste like the people in the novels of Henry James, who saw his countrymen through a haze of social hopeless. From whatever time or place they come, they are natural gentlefolk, who have seen the best of other civilization, and remained content with their own inheritances of culture. Like all men of spirit, Weir Mitchell had a large capacity for scorn. In his fiction and poetry, this revealed itself in his artistic reticence, springing from the innate refinement of his soul. He knew death in its most horrible forms; he knew life in its most terrible aspects. He had read human minds in the grim emptiness of decay or the frantic activity of the possessed. With his great descriptive power, he could have painted marvelous portraits of the human race in its moments of disgrace. But with a restraint which puts to shame those who today in the name of realism are prostituting their art and exploiting the base or the banal in our national life, the first great neurologist knew the difference between pathology and literature. The scientist knew how bitter life would be for in Roland Blake he said, "if memory were perfect, life unendurable. " But the artist knew that the highest function of literature is to record those lofty moments which make endurable the rest of life. May I appeal with a message from the founders to keep our ideals clear; they would wish me, I know, to remind you that it is not just another club of gentlemen interested in literature. Our Constitution provides for a limited number of distinguished public citizens. But unless the Inn is built around the "Book," it has not kept the spirit and intention of the founders. I realized this is not always easy. Great writers and painters come in clusters. They have come three times to Philadelphia first in the late eighteenth century, when Franklin, Francis Hopkinson, Thomas Godfrey, and Benjamin West established in America the art of the essay, poetry, drama, and painting; second, in the middle of the nineteenth century, when Robert Montgomery Bird and George Henry Baker for the first time challenged the playwrights of England with The Gladiator and Francesca da Rimini, and when Poe spent his six greatest years in Philadelphia; Third, in other group of our founders. Another cluster will arise in Philadelphia and, when that day dawns, may the Franklin Inn keep the light burning to attract them to its fellowship. I believe that ed can be helped by celebrations of the pioneers. I have tried to pay a tribute to them in a bit of verse-. Those days are done. Around the hall

You see the portraits on the wall

Of those who played the founder's part

In this, our friendly home of art,

Whose triumphs we tonight recall. Time runs-He never stoops to crawl-

The veil of memory partly pall

The splendors which the years impart-

Those days are done! Yet when across this evening fall

Clear voices from the past call

The quick blood back along the heart,

We know, by every pulse's start,

That Never, Till the end of all,

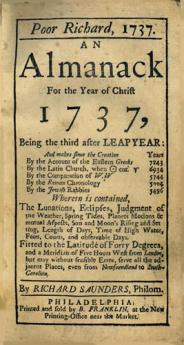

Those days are done! -- by: Arthur Hobson Quinn, January 17, 1952 In compliance with the requirements of an Act of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, entitled "An act to provide for the incorporation and regulation of certain corporations," approved the 29th day of April, A.D. 1874, and the supplements thereto, the undersigned, all of whom are citizens of Pennsylvania, having associated themselves together for the purpose hereinafter specified, and desiring that they may be incorporated according to law, do hereby certify: Witness our hands and seals this 17th day of April Anno Domini one thousand nine hundred and two. (signed) S. Weir Mitchell (seal) (signed) J. Bertram Lippincott (seal) (signed) Edward Brooks (seal) (signed) Francis Howard Williams (seal) (signed) William Jasper Nicolls (seal) Commonwealth of Pennsylvania City and County of Philadelphia} ss. Before me, the subscriber, Notary Public for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, residing in the City of Philadelphia personally appeared J. Bertram Lippincott, Francis Howard Williams and William Jasper Nicolls, thereof the subscribers to above and foregoing certificate of incorporation of The Franklin Inn Club, and in due form of law acknowledged the same to be their act and deed. Witness my hand and Notarial seal this 17th day of April Anno Domini one thousand nine hundred and two. (signed) Winfield J. Walker, Notary Public In the Court of Common Pleas No 5 of Philadelphia County of March Term, 1902. No. 2657. And now, this 12 day of May A.D. 1902, the above Charter and Certificate of Incorporation having been on file in the office of the Prothonotary of the said Court since the 18th day of April A.D.1902, the day on which publication of notice of intended application was first made, as appears from entry thereon, and due proof of said publication having been therewith presented to me, a law Judge of said County, I do hereby certify that I have perused and examined said instrument and find the same to be in proper form and within the purposes named in the first class of corporation specified in section 2 of the act of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, entitled "An act to provide for the incorporation and regulation of certain corporations," approved April 29th 1874, and the supplements thereto, and that the said purposes are lawful and not injurious to the community. It is, therefore, on motion of William Morris, Esq. on behalf of the petitioners, ordered and decreed that the said Charter be approved, and is hereby approved, and upon the recording of the said Charter and its endorsements and this order in the office of the Recorder of Deeds in and for said County, which is now hereby ordered, the subscribers thereto and their associates shall thenceforth be a corporation for the purpose and upon the terms and under the name therein stated. (signed) Robert Ralston, Judge Recorded in the office for the recording of deeds In and for the County of Philadelphia in Charter Book 27 page 209. Witness my hand and seal of office this 13th day of May Anno Domini One thousand nine hundred and two. (signed) Wm. S. Vare, Recorder January 17, 1706 Born in Boston, the thirteenth child of a candle maker; only went through 2nd Grade, Apprenticed to his brother as a printer, ran away to Philadelphia age 17 . 1725-26 First trip to England. Researched printing equipment, but probably lived a riotous life. 1726-1748 Returned to Philadelphia to found his own print shop and bookstore. Wrote and printed Poor Richard's Almanack organized local tradesmen into the Junto, formed partnerships with sixty printers throughout the colonies, obtained the print business of local governments, became postmaster. Able to retire at the age of 42 by selling his business for 18 annual payments, which offered him comfort and ease for considerably longer than his life expectancy.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1751 Helped found Pennsylvania Hospital. Entered the legislature. 1751-1757 Active in legislature, rising to leadership during the French and Indian War, Pontiac's Rebellion and the uprising of the Paxtang Boys.A Toast to Doctor Franklin

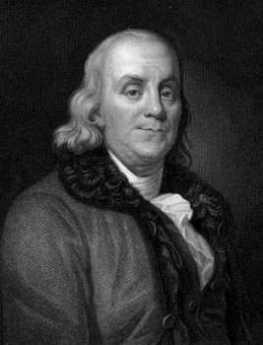

Benjamin Franklin

Toast To Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin,

Deborah Read

Claude-Anne Lopez

Anne-Catherine Helvetius

A Toast To J. William White, MD

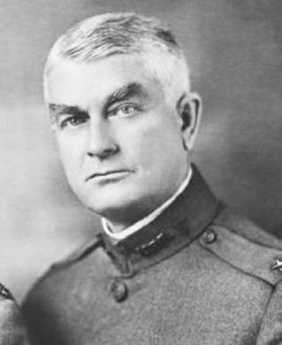

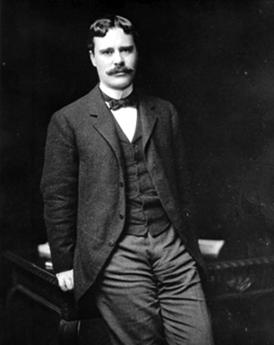

William J White MD

Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890

Amazon A Toast To Silas Weir Mitchell, MD

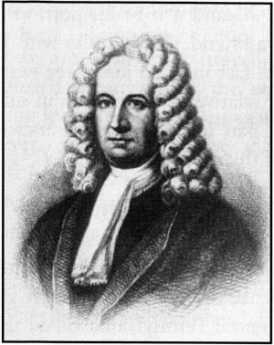

Silas Weir Mitchell

Franklin Inn

College of Physicians

Yet Another Toast to Dr. J. William White

Dr. J. William White

Dr. David Hayes Agnew

Professor Louis Agassiz

PGH

Agnew Clinic

First City Troops

Franklin Field

Army-Navy Games

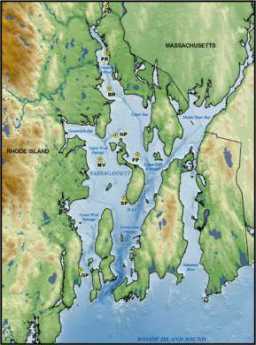

Narragansett Bay

William Mayo

Thomas Hardy

The Founding of The Franklin Inn Club

Charter of Incorporation of Franklin Inn Club (1902)

Benjamin Franklin: Chronology

Ben Franklin on the cover of Time magazine

1723 Arrived in Philadelphia penniless, readily found work as a printer.

1757-1762 Second time in England. Acted as representative of both Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. After his electoral defeat, he returned to England for a total of eighteen years, suggesting hidden British sympathies may have been present. .

1762-1764 Returned to Pennsylvania Legislature, where his unpopular agitation for replacing the Penn Proprietors with direct Royal government led to his electoral defeat and the end of his elective career. The defeated but determined Quaker party sent him to England to lobby against the Penn family and for the rule of Pennsylvania by the King.

1764-1775 Third British visit. Although unsuccessful in his lobbying, his fame as a scientist made him welcome among the famous members of the Enlightenment, like Hume, Adam Smith, Mozart. Meanwhile, the colonies became considerably more rebellious than he was. His blunder with the publication of some letters gave the British Ministry an opportunity to humiliate and disgrace him in public, probably as a warning to the mutinous New England leaders. It irreconcilably alienated Franklin, who sulked, then packed up and joined the Continental Congress the day he arrived back home.

March, 1775-October, 1776 Brief but fateful return to America. Decisions were made in London to put down the colonists by as much force as necessary. Meanwhile, Franklin persuaded the Continental Congress they must declare independence from England if they expected help from the French.

July 4, 1776, Independence is declared within days after the arrival of a massive British fleet in New York harbor. Franklin dispatched to France to secure the assistance he was confident he could get.

1777-1785 France. Franklin served admirably as American ambassador, his wit and charm persuading the French to overextend themselves with ships, supplies, and money, and very likely contributing to the French Revolution by popularizing the American one.

1785-1790 Returning as a national hero for his final five years of life, Franklin loaned his personal influence to the constitutional convention, became President of Pennsylvania, worked for the abolition of slavery.

April 17, 1790 Died, probably of complications associated with kidney stones.

Logan, Franklin, Library

|

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

Jim Greene is the librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia, and one of the leading authorities on James Logan, the Penn Proprietors' chief agent in the Colony. Since Logan and Ben Franklin were the main forces in starting the oldest library in America, knowing all about Logan almost comes with the job of Librarian. We are greatly indebted to a speech the other night, given by Greene at the Franklin Inn, a hundred yards away from the Library.

|

| James Logan |

Logan has been described as a crusty old codger, living in his mansion called Stenton and scarcely venturing forth in public. He was known as a fair dealer with the Indians, which was an essential part of William Penn's strategy for selling real estate in a land of peace and prosperity. Unfortunately, Logan was behind the infamous Walking Purchase, which damaged his otherwise considerable reputation. Logan must have been a lonesome person in the frontier days of Philadelphia because he owned the largest private library in North America and was passionate about reading and scholarly matters. When he acquired what was the first edition of Newton's Principia, he read it promptly and wrote a one-page summary. Comparatively few people could do this even today. It's pretty tough reading, and those who have read it would seldom claim to have "devoured" it.

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Except young Ben Franklin, who never went past second grade in school. The two became fast friends, often engaging in such games as constructing "Magic Squares" of numbers that added up to the same total in various ways. For example, Franklin doodled off a square with the numbers 52,61,4,13,20,29,36,45 (totaling 260) on the top horizontal row, and every vertical row beneath them totaling 260, as for example 52,14,53,11,55,9,50,16, while every horizontal row also totaled 260 as well. The four corner numbers, with the 4 middle numbers, also total 260. Logan constructed his share of similar games, which it is difficult to imagine anyone else in the colonies doing at the time.

Logan and Franklin together conceived the idea of a subscription library, which in time became the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1732. The subscription required of a library member was intended to be forfeited if the borrower failed to return a book. Later on, the public was allowed to borrow books, but only on deposit of enough money to replace the book if unreturned. We are not told whose idea was behind these arrangements, but they certainly sound like Franklin at work. More than a century later, the Philadelphia Free Library was organized under more trusting rules for borrowing which became possible as books became less expensive.

Logan died in 1751, the year Franklin at the age of 42 decided to retire from business -- and devote the remaining 42 years of his life to scholarly and public affairs. He first joined the Assembly at that time, so he and Logan were not forced into direct contention over politics, although they had their differences. How much influence Logan exerted over Franklin's plans and attitudes is not entirely clear; it must have been a great deal.

Madame Butterfly (2)

|

| John Luther Long |

There are two ways of looking at the love affair of Pinkerton, the dashing Philadelphia naval officer, and Madame Butterfly, the beautiful Japanese geisha. John Luther Long wrote about it one way, while Puccini somehow portrays it differently, even though Long collaborated on the Libretto of the opera. Puccini, of course, was himself a famous libertine, tending to follow the typical belief of such men that women somehow enjoy being victimized. Long in real life was a Philadelphia lawyer, trained to keep a straight face when people relate what messes they have got into. If you know the story, you can see Long in the person of Sharpless, the consul. Sharpless is definitely meant to be a Philadelphia name.

|

| Madame Butterfly |

Long was one of the early members of the Franklin Inn, and it is related he wrote much of his successful play at the tables of the club on Camac Street. David Belasco was the "play doctor" who knew how to make a good story fill theater seats. Even after Belasco's polishing, the play came through as a portrayal of the well-born gentleman who had been trained to regard foreign girls as just what you do when you are away from home. His real girlfriend, the beautiful Philadelphia aristocratic woman in a spotless white dress, was the sort you expected to marry. In just a few sentences of Long's play, this woman comes through as just about as distastefully aloof to foreign women as it is possible to be while remaining rigidly polite about it. Butterfly sees this at a glance, knows it for what it is, and knows it is her death. Her duty immediately is "To die honorably, when one can no longer live with honor".

It is Puccini's genius to take this story of how two nasty Americans destroy an honorable Japanese girl and using that same story with the same words, make it into a romantic woman being destroyed by a hopeless, helpless love affair. The power of the music overwhelms the story and sweeps you along to the ending. Even if you feel like Long/Sharpless, dismayed and disheartened by watching some close acquaintances doing things you know they shouldn't.

When Puccini's opera comes to Philadelphia every year or so, the Franklin Inn has a party for the cast, one of the great events of the Philadelphia intellectual scene. Somehow, the full intent of Luther Long's work never seems to come out.

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society was founded in 1827, and it organized the first Flower Show in 1829. For a century it was only an amateur display, very similar to the sort of local garden club display found in many towns and villages in England. The timing of such shows is dictated by the booming season of the flowers of the region, so the display depends on the dates of the local flowers, related in turn to soil and weather conditions. In the early part of the Twentieth Century, W. Atlee Burpee became the dominant force in the Philadelphia show. The show established a long tradition of domination by seed companies and nurseries, with elaborate displays which often took a week to set up, preceded by months or years of planning. The central difference in the nature of the Philadelphia show was that plants were forced into bloom, so much of its impact depended on displays which were seemingly entirely out of season. After World War II, Ernesta Ballard became the moving and controlling force, driving The Show into enormous popularity in the new larger quarters at Convention Hall. Considerable revenue was generated and used to beautify Philadelphia. The Show became the biggest, best, most popular and best funded flower show in America. Ernesta was a success.

|

| Mrs. Ballard |

Gradually, the most elaborate or dominant displays were put on by florists, using cut flowers. That was not necessarily Mrs. Ballard's original intention, although it might have been. It is the nature of plant nurseries to take away a ball of topsoil when they sell a plant, and that tends to dictate the location of the major nurseries in places where farmers are willing to ruin the land for farming, looking to speculate on suburban development. They thus are usually rural or exurban, because prime farmland is too expensive. Obviously, nurseries are pressed outward from the rim of the expanding city, and may even be forced to locate at a considerable distance away. These realities of the business tend to diminish the local loyalties of the nurseries and the city to each other. Mainly, cut flower arrangements resisted this trend by using greenhouses, but air freight has now made it possible for exhibitors of live plants to come from the Netherlands, Peru, and even Korea. The Flower Show is still held in Philadelphia, but it is much less a product of Philadelphians, especially amateur Philadelphians. When large single exhibits now can cost $100,000 apiece to organize, it is not surprising that the Philadelphians who do exhibit, are members of the upper crust.

And then there are those unions. While upper crust exhibitors can afford to pay full union wages for an electrician to plug in one electrical outlet, they are instantly offended by the whole featherbedding experience of being forced to do it. And since a great many blue collar union members are hostile to any suggestion that these gentleman farmers are in any way their social superiors, they can display what is known as an attitude. Philadelphia is famous for aggressive unions, and the Convention Center is additionally notorious for unions with political clout. Somehow, the politicians in charge of this unfortunate passive-aggressive scene get control of it and are seen to get control of it. After all, snooty exhibitors are occasionally in a position to move whole factories out to the suburbs, to the general injury of the city; moving a flower show wouldn't be too hard to do. The paradox is that 70% of these union members live in the suburbs themselves. The Flower Show cannot run without the enthusiastic help of 3500 volunteers, easily turned off by muscling them. The judging is done by 175 volunteer judges from all over America, coming to Philadelphia at their own expense, for example.

The Flower Show has had memorable moments. There was a time when the Shipley School consistently won most of the prizes. There was a famous episode when the Widener Estate of Linwood had a world-famous Acacia display. When it was broken up, there was an uproar when it was given to Washington DC, instead of staying right here where it belonged. Now, the gossip is about exhibitors from Ukraine, or from Japan, making little laughable mistakes about local geography with many streets named One Way.

The Show goes on and thrives. But just what its future is going to be is unclear. The Convention Center has doubled its space, but whether it can double its business is uncertain. And the management has recently changed from leadership which had a focus on the show and regarded city beautification as something to do with left-over profits, to leadership with a primary interest in the beautification of the city. No business will thrive if it neglects its revenue stream. So, please be careful with our nice Flower Show.

REFERENCES

| Standardized Plant Names: American Joint Committee on Horticultural, Frederick Law Olmsted | Google Books |

Durance Vile

|

| Castle of Ferdinand and Isabella |

Visitors to the royal castle of Ferdinand and Isabella are routinely shown the iron grating beneath the throne, below which is a small dark hole for a couple of prisoners. By contrast, most American cities have prisons containing thousands of prisoners. At the time of the discovery of America, dungeons were places to hold a few important prisoners waiting for execution or ransom. What happened to other criminals is left to the imagination, and ranged from public flogging to public execution, often preceded by torture. Torture was not primarily a method for extracting espionage from a spy, it was a form of punishment, quite explicitly designed to horrify and intimidate others who needed the warning to prevent crime. Imprisonment was too expensive to be justified in the case of ordinary crime; in the Eighteenth Century, it was common to hang people for stealing a loaf of bread. Hanging alone might not be sufficiently awesome; the hanged criminal was often torn apart and the pieces of meat dragged through the streets by horses. In extreme cases, hanging was dispensed with and it was sufficient to draw and quarter the miscreant.

|

| Victorian Era Prison |

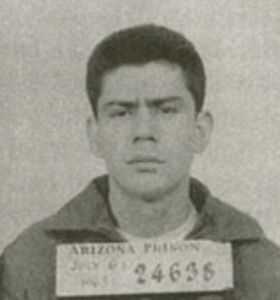

Without further unnecessary detail, the point must be made that imprisonment was originally devised as a humane improvement, an enlighted advance. It is nevertheless entirely true that prison conditions in every jurisdiction in every country -- are unspeakably bad. While it is probably true that public officials commonly take the view that if we must have these prisons, it is of some deterrent value to spread rumors that they are worse than they actually are. The central truth is that prisons are more expensive than most people want to spend on deterrence and punishment; so they are characteristically underfunded, and most evils grow out of the pinch-penny management which the taxpayers force on the wardens. Bleak, dank and dirty, usually a century or more old, with disgusting food, cramped quarters, and a pervasive atmosphere of suppressed violence, sometimes inadequately suppressed, these forgotten warehouses confine prisoners and jailers alike in a cloud of well-justified terror of each other. Add to this mess of the Victorian era, the more modern features of HIV, male rape and smuggled drugs, and everyone involved are ready for a new approach. If only someone could devise one.

|

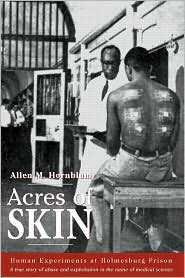

| Allen Hornblum |

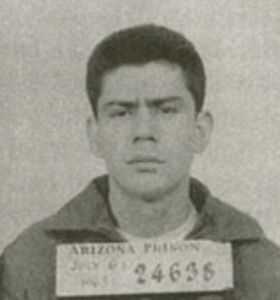

At the Franklin Inn recently, Allen Hornblum appalled the literary lights of the city with a description of one of the lesser but nevertheless unnecessary sins of the system, the recruitment of volunteer prisoners for medical experimentation. Forget that the prisoners are all convicted of serious crimes, often as a result of a psychopathic mindset; many of them are illiterate, bored to tears, and desperate for a little spare cash to spend on the prison luxuries of sex, cigarettes, drugs, protection from other prisoners, candy and prestige. The prisons themselves set the monetary exchange rate at $.25 a day for working in the laundry; pharmaceutical firms may be unnecessarily generous in paying a dollar a day for medical volunteers. As described in his two books, Acres of Skin and Sentenced to Science, this Temple professor felt skin experiments were particularly gruesome to behold. When the prisoners were often covered with many Band-aids over their patch tests and biopsies, it gave newcomers an immediate impression that they represented widespread fighting and violence, when of course they were mostly harmless. The language of the streets is magnified in prison, and it infects the speech of the clinical investigators no matter how hard they try to blend in while they do their work.

|

| Acres of Skin and Sentenced to Science |

Meanwhile, medical personnel in a prison are neither jailers nor prisoners, and commonly inject a worrisome outside observer status into the submerged civil war. Both prisoners and jailers court the nurses and doctors but occupy a dangerous ground. They can give out medical excuses, drugs, escape opportunities, and more or less impartial testimony if there is an outbreak of violence. Violence by the guards is observed without comment or intervention because the guards are the only hope of protection if the prisoner's riot. Guilty secrets are more or less kept inviolate, but both sides of the war distrust this ethical principle. Everybody, but especially a doctor or nurse, endures constant silent appraisal. Unattractive rumors abound.

Consequently, medical care in prison everywhere is unavoidably substandard. Although the jailhouse lawyers would love to sue somebody for something, it's hard to see what could be accomplished for more than a brief time. There seem to be a number of billionaires who would like to do something to help this situation, but what this problem needs is not more money, but a better idea. Should we really go back to flogging, branding irons and gouging out eyes? It would be cheaper, but if the reformers really want reform, they have to suggest something that would work. So we could all agree to do it.

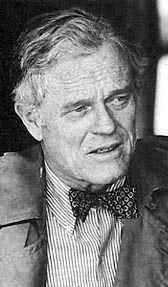

Franklin's Admirers on TV

|

| Brian Lamb |

There are now three channels of C-span, continuous cable television programs about the influence of history on current problems. Sessions of Congress and its committees, the speeches of the President, political campaigns, are shown as they happen. But interviews and book reviews are shown in parallel, with an opportunity to go into the archives and organize originally unrelated programs into seminars on a current topic. The editor, Brian Lamb, has a light hand and considerable impartiality. But he's there, all right, organizing blogs into topics just as Philadelphia Reflections tries to do.

|

| Friends Select School |

This similarity of design had been floating around for some time, but it suddenly came into focus when I recognized myself in the front row of an audience on C-span, listening to Edmond S. Morgan talking at the Friends Select School about his new book on Benjamin Franklin, a few months earlier. Thank goodness I bought a book and had it autographed because the filming had been so unobtrusive I hadn't noticed it at the time. I clearly need to have haircuts more frequently. Professor Morgan's parting words that evening had stayed with me, "Franklin doesn't tell you everything about himself, but what he tells you -- is straight." That's quite a compliment from the editor of 47 volumes of Franklin's work.

|

| Walter Isaacson |

Grouped with this tv portrayal of me as a groupie were interviews with Walter Isaacson and some other Franklin biographers, taken at other times and placing focus on other aspects. Here again, more insights emerged from quickly considered replies to audience questions than from the prepared speeches. Replies to questions from the audience are more in a class with blogs, anyway. Whenever you get all of the adjectives and qualifications polished, you sometimes don't say what you mean. Perhaps that last comment can be rearranged to say that answering audience questions occasionally leads to blurting out precisely what you mean.

And so, two unrelated audience answers need to be linked. A question about Franklin's love life caused Isaacson to refer to Franklin as a lifelong seducer. From the unknown mother of his illegitimate son William, to the simultaneous flirtations with two famous French ladies that took place when he was an octogenarian, and not overlooking several other affairs with Cathy Green and Polly Stevenson and allusions to others, Franklin was obviously an accomplished seducer in the full meaning of the term. It is thus legitimate to suspect the techniques of seduction at work in many of his public projects, from starting the Library Company to persuading the French to help the Revolution. He discovered late in life what many have discovered about the life of a diplomat, and quickly recognized that he was already pretty good at what that seemed to entail. Let's slide to a slightly different application of that idea.

|

| Benjamin Franklin and French Women |

By the accident of hostess seating arrangement, I found myself seated next to two historians from Harvard, and somehow it came out that one of them felt that Franklin loved the French. Simply loved them. Somehow that didn't sound quite right when compared with Franklin's early years of mobilizing Pennsylvania to fight the French, starting the first National Guard militia unit to defend Philadelphia against French raiders, supporting General Braddock's expedition with his own money, urging the British government to sweep the French from Canada, and working most of his life to assemble the colonies and Great Britain into one world-dominating entity. It's true that 18th Century France was at the peak of scientific achievement, and Franklin the inventor of electricity was quickly taken in by the European scientific community, but that's scarcely the same thing as loving France. Louis XVI was in fact quite annoyed by all the attention Franklin was receiving. And so the scholar on TV went on to say that correspondence had been discovered in which Franklin quite casually remarked that during the Continental Congress he had strongly argued that America should stand alone and have no European allies. Congress it seems overruled him, so he dutifully set sail for France to seduce them.

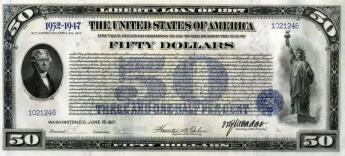

We come to another chance social encounter. On a recent trip to Paris, the GIC had taken along as a speaker, no less than a member of the Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, a Governor of a Federal Reserve District, to speak about the threat of inflation and currency crisis. In time, our French hosts invited us to look at some documents of interest, like the Louisiana Purchase. Lying on the table was the original treaty between America and France, signed by B. Franklin. The Federal Reserve governor, making small talk, observed that Franklin sweet-talked the French into loaning America too much money, eventually leading to their bankruptcy. As I recall, my rejoinder was, "Well, just print some more paper money, right?" It was intended to be a jocular remark, but it somehow didn't seem to be taken as such.

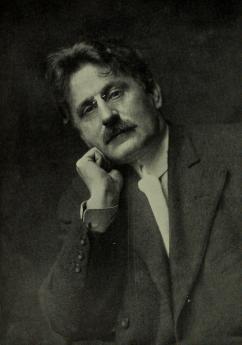

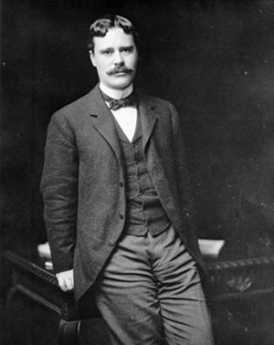

Frank Furness,(3) Rush's Lancer

|

| Frank Furness |

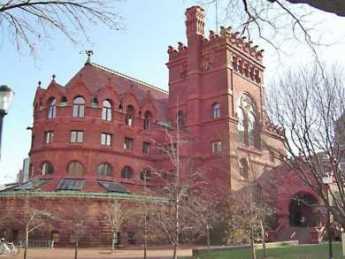

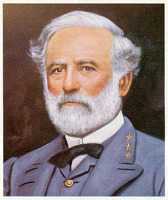

Lunch at the Franklin Inn Club was recently enlivened by David Wieck, who not only does the sort of thing you get an MBA degree for but is also a noted authority on the Civil War. His topic was the wartime exploits of Frank Furness, whose name is often mispronounced but whose thumbprints are all over the architecture of 19th Century Philadelphia. Take a look at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy, the Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania, and many other surviving structures of the 600 buildings his firm built in 40 years. One of them is the Unitarian Church at 22nd and Chestnut, where his grandfather had been the fire-brand abolitionist minister.

|

| PennsylvaniaAcademy of Fine Arts |

The Civil War seems to have transformed Frank Furness in a number of ways. He had been sort of in the shadow of his older brother Horace, a big man on the campus of Princeton, later the founder of the Shakspere Society, and the Variorum Shakespeare. Frank was quiet, and good at drawing. However, at age 22 he was socially eligible to join Rush's Lancers, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which contained among other socialites the great-grandson of Robert Morris, and a member of the Biddle Family who put up the money to equip the troop with 7-shot repeating rifles. Cavalry units like this were a vital weapon in the Civil War because they needed young well-equipped expert horsemen with a strong sense of group loyalty. Rifles were considered too expensive for infantry, who were equipped with muskets that took several minutes to reload, and were unwieldy because they were only accurate if they were very long. When bands of daredevils on horseback suddenly attacked with seven-shot repeating rifles, they could be devastating against massed infantry. A flavor of their bravado emerges from their rescue of General Custer's men from a tight spot, later known in the annals of the troop as "Custer's first last stand."

|

| The Undine Barge Club Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy |

There are two famous stories of the exploits of Frank Furness, first as a second Lieutenant and later as a Captain at Cold Harbor two years later. In the first episode, a wounded Confederate soldier lay on the no man's land of forces only a hundred yards apart. His screams were so heart-rending that Furness ran out to him and put a handkerchief tourniquet around his bleeding thigh. Because the fallen man was a Confederate soldier, the Confederates held their fire and later cheered the Union cavalryman for his kindness. The wounded man called out "

|

| The Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania |

In the second episode, the cavalry had spread out too much, leaving some isolated parties trapped and out of ammunition. Furness lifted a hundred-pound box of ammunition to his head and ran through the gunfire with it to the trapped men. For this, he later received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Somehow all of the public attention he received in the war transformed Furness from a younger brother who was good at drawing into a dynamo of energy, much in the model of what law firms call a "rainmaker". He traveled to the Yellowstone area of Wyoming at least six times, bringing back various trophies. He was known to get people's attention by using his service revolver to take pot shots at a stuffed moose head in his office.

|

| First Unitarian Church 22nd Chestnut Philadelphia |

His final publicity venture was to advertise, forty years later, in Southern newspapers for the whereabouts of the Confederate soldier whose life he had saved. Eventually, a man named Hodge who had later been a sheriff in Virginia, stepped forward to renew his blessings and thanks. Hodge was brought to Philadelphia for a celebrated 6th Cavalry reunion, and a picture of the two former enemies was spread in the newspapers. It was a little embarrassing that Furness and Hodge found they had very little to say to each other for a five-day visit, but Hodge eventually proved able to be one-up in the situation. He outlived Furness by five years.

Although the style of Furness confections seemed and seems a little strange to everyone except Victorian Philadelphians, he did leave a major stamp on American architecture. His most noted student was Louis B. Sullivan, who put an entirely different sort of stamp on Chicago. And Sullivan's best-known student was Frank Lloyd Wright who created a modernist image of architecture for the West. The buildings of these three don't look at all alike, but their rainmaker personalities are all essentially the same.

World Finance, Columbus Day 2008

|

| Prime Minister Gordon Brown |

WITH voters watching three weeks before the 2008 American presidential election day, finance ministers and their political masters met to decide a basic question: dare they risk disaster to save the existing system, or play it safe by sacrificing small banks to rescue big ones? That is, guess if the situation is so bad only strong rowers can be allowed in the lifeboat, or whether things are really manageable enough to try to save everybody but at the risk of worse consequences for failure. For example the credit default swap mystery; there are $60 trillion notional value insurance policies in existence to cover $20 trillion of bonds. Is that massive double-counting, or an actual disaster so severe it makes every other consideration trivial? Answer quick, please, the ship looks like it might sink. At first, it seemed strange a Labor government in England would propose saving only the strong until you realize that Prime Minister Brown is protected from his Left, while the Democrats in America want to use a fairness argument to win their election. A Republican lame-duck president must do the deciding, a man who has been shown to be both a tough politician and a fearless gambler; playing things safe is not his style. The Dow Jones average soared a thousand points in a day's trading on the prayer that things were finally under control. But take a look around.

Little Iceland and Switzerland are proud to house some enormous banks. But if those banks approach failure, their homeland treasuries are far too small to bail them out.

On the other hand, little Hungary has a negligible banking system, so Hungarians commonly borrow money from foreign banks. The national currency devalued by half in this crisis, so most Hungarian mortgages doubled in price. Reserve systems based on national governments suddenly look obsolete.

Try another approach. Little Ireland went ahead and guaranteed all deposits in its financial institutions. Money from England and the rest of Europe immediately poured in to enjoy that guarantee, forcing other grumpy nations to match the unwise Irish offer. There's a sense that nations are losing control of their affairs.

Europe consists of 27 nations, of which fifteen are in the Euro zone. There are common currency and a constrained central bank, but can this gaggle of geese possibly agree on concerted action in this crisis? America was once in this situation under the Articles of Confederation, but even after almost losing the Revolutionary War, George Washington was nearly unable to get the colonies to form a union. Even after this experience, the Southern Confederate States later adopted the same system of a central currency without a central government and really did lose their war.

Are we to infer from Prime Minister Brown's attitude toward banks that he might soon suggest ditching little nations in order to save bigger ones?

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1525.htm

For the Good of the Order

Although it has older origins, Roberts Rules of Order provide a place in every meeting for remarks "for the good of the order", suggesting there should always be an opportunity to deviate from strict germaneness to speak about something which is clearly worth talking about. Although meetings for business usually appoint a chairman, speaker or clerk to preserve order and germaneness, the truth is that most meetings which lose the opportunity to introduce something worthwhile which is a little off the subject, do so because of habit and tradition rather than devotion to focus. In recent years, remarks for the good of the Order have become so uncommon that speakers tend to rise on "a point of personal privilege", although provision for this had in mind birthday greetings and the like.

I suggest it might be a useful and entertaining thing to devote some meetings of the Franklin Inn to discussions of ways we could improve the club, and if the club has seemingly already reached perfection, to ways of improving Philadelphia and its Commonwealth.

|

| The Franklin Inn |

Such an effort will struggle at first, so it needs a core group to assure hesitating attendees that something worthwhile will be said. That core group may include officers and officials who are charged with running the club, the city or the state, but the opinions of the meeting should carry no enforcement powers other than their intrinsic validity. Admittedly, there is a natural restlessness of independent thinkers that their ideas should go somewhere, so the meetings should maintain minutes, perhaps on a website.

The attendees should pay for their lunches with meal tickets, but should also maintain a book of tickets for invited guests, and sell tickets to uninvited ones. If the present markup for tickets is maintained, an attendance of six regulars would sustain the invited speaker ticket book, and the attendance of six uninvited (no-club members) would make subsidy unnecessary. For the initial year, however, the club itself should subsidize speaker lunches. If there are conflicting meetings the Meetings for the Good of the Order should move to the second floor, and perhaps that is the best place for all of them.

These meetings should not fall into the trap of grieving that their innovative suggestions are not adopted, although they may be forgiven for celebrating the occasions where an idea does get implemented. The goal is to help an idea grow legs, and then watch it travel, ever mindful that much can be accomplished when we disregard who gets credit for it.

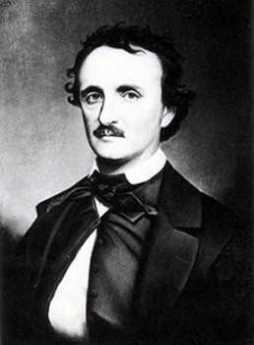

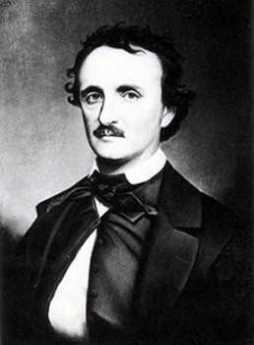

Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849

|

| Edger Allan Poe |

Between the Federalist period and the Civil War, Philadelphia quadrupled in population, mostly by Irish and black immigration responding to the urbanization induced by the Industrial Revolution. The social boundaries of this period were established by the U.S. Capital moving away to Washington, and at the other boundary, the constrained urban population was suddenly released to the suburbs by the City-County Consolidation of 1854. During that time, the Northern Liberties on the other side of Callowhillwere very close by, but nearly devoid of law and order. At least along the Delaware River, the scene was like Las Vegas as imagined by Charles Dickens. Within the increasingly congested boundaries of the city itself, tuberculosis, alcoholism, riots and religious revivalism are all mentioned prominently. While it was the time of Nicholas Biddle and the Bank, and the establishment of the Drexel empire, it was a gothic period quite adequately symbolized by Ethan Allan Poe, writing for Graham's Magazine. His father abandoned the family, his mother and later his wife died of tuberculosis, he was definitely an alcoholic and probably manic-depressive. He and Charles Brockton Brown invented the gothic novel, gothic poetry, the modern murder mystery. Poe only lived in Philadelphia for six years but lived in seven different locations, the most famous of which is now part of the National Park Service, even though it is located off Spring Garden Street. Yes, he was born in Boston but lived there only briefly, and yes, he died in Baltimore, by dropping dead in the street while traveling through. He was scarcely a prototypical Philadelphian, but he was certainly a symbol of his age.

|

| Grip the Raven |