Related Topics

Franklin Inn Club

Hidden in a back alley near the theaters, this little club is the center of the City's literary circle. It enjoys outstanding food in surroundings which suggest Samuel Johnson's club in London.

Philadelphia Physicians

Philadelphia dominated the medical profession so long that it's hard to distinguish between local traditions and national ones. The distinctive feature is that in Philadelphia you must be a real doctor before you become a mere specialist.

Quakers: The Society of Friends

According to an old Quaker joke, the Holy Trinity consists of the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Academia in the Philadelphia Region

Higher education is a source of pride, progress, and aggravation.

Science

Science

Philadelphia Medicine (2)

Philadelphia is where medicine began in America

Benjamin Franklin Parkway

Benjamin Franklin Parkway

Education in Philadelphia

Taxes are too high, but the tax base is too small, so public education is underfunded. Drug use and lack of classroom discipline are also problems. Business and employed persons have fled the city, must be induced to return. Deteriorating education, rising taxes and crime are the immediate problems, but the underlying issue is lack of vigor and engagement by the urban population itself.

Lumpers In Constant Combat With Splitters

|

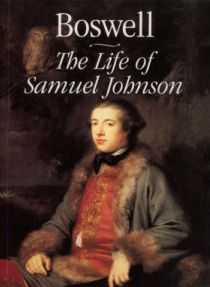

| James Boswell's Book |

Some colleges produce managers by teaching management theory, but in certain Ivy League colleges it is thought to be more useful to teach how to dominate a committee, eventually perhaps a board of directors, or a board of trustees. The handbook of instruction is James Boswell's Life of Johnson which is a rather large book of verbatim notes that Boswell took of his many lunches at a London club in the 18th Century. Boswell was a quiet mouse privileged to sit in the company of the great Dr. Samuel Johnson, surrounded by the most eminent intellects of the Enlightenment. Boswell carefully manages the background of each episode, describing the issue and the various arguments, and then -- Sam Johnson's booming voice settles the matter. After he speaks, the meeting is over.

|

| Dr. Samuel Johnson |

"Why, sir", says Johnson, and then look out for the one-liner to follow. We get the impression that Dr. Johnson used that "Sir" signal to indicate he had enough of these dumb arguments, and soon would come the growled epigram that scatters any token resistance. Boswell may have neglected to record instances where the great Johnson was defeated in debate, who knows. We are left with the distinct impression that if you engaged in lunch table conversation with Sam, you were almost certain to lose. So that's what Ivy League students are being taught: how to win a debate at a committee meeting, in the expectation they would spend much of their lives in committees, boards, and even cabinets. That's how the English-speaking world gets its work done and its decisions made. That's what lunches at the Franklin Inn Club, or the club tables of the Union League, are trying to do for the education of neophytes.

As the goggle-eyed student of the great Chauncey Tinker, who gave young Pottle his start in life, it was an awesome performance for me to watch. But the rules of this game never became entirely clear to me, I'm afraid, until the other evening when I listened to Peter Nowell describe in a half-dozen brief paragraphs how he had revolutionized prevailing theories of the cause of cancer. The Franklin Institute then followed the award ceremony by putting on an all-day symposium of notables who run elaborate enterprises in cancer research, essentially funded by the National Institutes of Health, your tax dollars at work again. Last year, the NIH dispensed thirty billion -- you heard me -- dollars in research grants to internationally known research entrepreneurs, and if you can stay awake during their talks, there must be something the matter with you. So far as I could see, they were painstakingly describing every grain of sand on the beach, whereas Peter Nowell made the whole beach electric and clear in ten minutes. Essentially, he was saying that each patient's cancer is caused by a long chain of events, starting with a single mutation within a single cell. All the other cancer cells of a patient are descendants of that first one, which triggered the cascade of chemical events now repeated by the descendants. To stop the process, you probably only have to find a way to break the chain at one vulnerable point. Then you have a cure, without necessarily understanding every other link in the chain.

Peter Nowell described himself as a "lumper", admitting that most scientists are "splitters". A splitter quite reasonably attacks a complex problem by isolating one small piece of it at a time; that's really a pretty good way to address overwhelming complexity when you encounter it. But you can be sure that people of that mindset should not be found in a President's cabinet, deciding how to save the world from impending disaster. Whether by their own genetic predisposition or as a result of peer pressure in their profession, they are habitual splitters. And it suddenly occurred to me why Sam Johnson's one-liners always won the argument; he was a lumper. Usually right, sometimes wrong, never in doubt. Witty as a Frenchman, but as quick as a rattlesnake. Cordial, perhaps, unless you disagreed with him.

We need more lumpers. If they get that way from the likes of Chauncey Tinker, we need to print more copies of The Life of Johnson. If they are born that way, maybe we need a breeding farm for lumpers, which is what the Assembly Ball amounts to. But don't get me wrong, we need more splitters, too. They just have to learn their place at the table.

Originally published: Monday, May 03, 2010; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 23, 2019