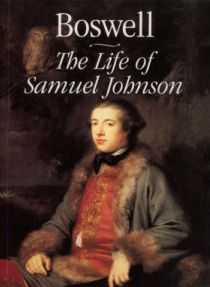

3 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Philadelphia Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began about the time America declared Independence. The young nation faced a clean slate and boundless opportunities.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Science

Science

Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic

|

| Anne Mc Donald |

Anne T. Macdonald developed the idea in 1948 that a large number of blinded war veterans would benefit from recorded textbooks. Starting at the New York Public Library and now with a national headquarters in Princeton, a string of 29 centers have appeared across the nation, with an average of 7000 volunteers contributing their time reading textbooks into recording devices. The Philadelphia effort started at 36th and Market and has since moved to King of Prussia, where 280 volunteers read in teams of two, one inside the recording booth, and the other outside following the performance and stopping it for errors or muffled recordings. Since the effort specializes in technical textbooks, there is a constant search for specialists in particular technical fields. It is particularly important to understand the technical nature of the material when pronunciation is difficult, and when complicated graphs or illustrations need to be described for a blind audience. Originally, the material was produced on reels of tape but tends nowadays to concentrate on CDs and other disc recording devices.

|

| Ralph Cohen |

Ralph Cohen, himself a volunteer reader, very kindly described the enterprise to an audience at the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia recently. It is particularly heartening to hear stories of blind persons receiving advanced technical degrees because of the availability of these recorded texts, even stories of those who rose from menial jobs to become engineers through this pathway.

|

| Ray Kurzweil |

For those who have a particular interest in the topic, a few facts are important to know. Volunteers in technical fields are particularly needed, with two-hour recording slots extending over a relatively long time until a text is completed. Contributed money is needed in order to buy equipment and house it in a soundproof environment. Because of concern about copyright infringement, it is necessary to insist that the recorded products are only available to members of the reader's group, each one certified to be in need of such material because of a physical handicap. There is a fee of $65 to enroll, with $35 annual dues.

An interesting sidelight on reading difficulties emerges from the fact that most people who need help can see perfectly well. The disorder of dyslexia is so widespread that probably a majority of the population has at least a trace of it. The underlying problem with dyslexia lies in the brain, not in the eyes. The most common variant is to invert the sequence of words or letters, making such people utterly unable to record or remember a telephone number in the correct sequence. Often, psychological difficulties follow, as impatient siblings and acquaintances describe the victims as "stupid", a slur they often come to believe, themselves. A learning difficulty leads to a lack of learning, and the deficit becomes a real one. To the degree that these Recordings for the Blind and Dyslexic allow some to conquer their handicaps gives hope to others. One can even hope to see the whole matter unwind into a revision of the educational process, leading to a better and more prosperous society.

By an interesting coincidence, 1948 was the year Ray Kurzweil was born in Brooklyn. Developing an early interest in computers, his name is now associated with synthetic speech and voice recognition technology, and he has even branched out into music synthesis. He's a visionary, all right, and a promoter. If voice transcription gets tweaked just a little more, it is going to replace dictaphones and secretaries by the hundreds of thousands. No doubt Kurzweil is destined to become very rich if indeed he is not already so. It's thus a little startling to encounter him as a professional entertainer on the lecture circuit, apparently driven relentlessly by a need to be appreciated. If that's what he needs, let's give it to him. The transformation of half of our society seems within his grasp. And in many ways his success is based on the flash of insight that dyslexic people are not stupid; in fact, maybe no one is. We all walk around with computers in our skull, and computers are always full of bugs. No doubt it should be said of brains, as it is of computer programs, that one has never been created that did not contain many "bugs". The important issue is not whether the computer is defective, but whether it somehow mobilizes the effort to overcome its defects.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1182.htm

Native Habitat

|

| Gifford Pinchot |

Teddy Roosevelt's friend Gifford Pinchot is credited with starting the nature preservation movement. He became a member of the Governor's cabinet in Pennsylvania, so Pennsylvania has long been a leader in the formation of volunteer organizations to help the cause. Sometimes the best approach is to protect the environment, letting natural forces encourage the growth of butterflies and bears in a situation favorable to them. Sometimes the approach preferred has been to pass laws protecting threatened species, like the eagle or the snail darter. Sometimes education is the tool; the more people hear of these things, the more they will be enticed to assist local efforts. The direction that Derek Stedman of Chadds Ford has taken is to help organize the Habitat Resource Network of Southeast Pennsylvania.

|

| butterfly |

The thought process here is indirect and gentle, but sophisticated; one might call it typically Quaker. Volunteers are urged to create a little natural habitat in their own backyards, planting and protecting plant life of the sort found in America before the European migration. If you wait, some insects which particularly favor the antique plants in your garden will make a re-appearance, and in time higher orders like birds that particularly favor those insects, will appear. The process of watching this evolution in your own backyard can be very gratifying. To stimulate such habitats, a process of conferring Natural Habitat certification has been created. In our region, there are over three thousand certified habitats.

Of course, you have to know what you are doing. Provoking people to learn more about natural processes is the whole idea. For example, milkweed. That lowly weed is the source of the only food Monarch butterflies will eat, so if you want butterflies, you want milkweed. For some reason, perhaps this one, the Monarch is repugnant to birds, so Monarchs tend to flourish once you get them started. After which, of course, they have their strange annual migration to a particular mountain in Mexico. Perhaps milkweed has something to do with that.

|

| Empress tree |

If you plant trees and shrubs along the bank of a stream, the shade will cool the water. That attracts certain insects, which attract certain fish. If you want to fish, plant trees. And then we veer off into defending against enemies. The banks of the Schuylkill from Grey's Ferry to the Airport are lined with oriental Empress trees, with quite pretty purple blossoms in the Spring. These trees seem to date from the early 19th Century trade in porcelain (dishes of "China" ) on sailing vessels. The dishes were packed in the discarded husks of the fruit of the Empress tree, and after unpacking, floated down the Schuylkill until some of them sprouted and took root. Empress trees are certainly an improvement over the auto junkyards hidden behind them. On the other hand, Kudzu is an oriental plant that somehow got transported here, and loved what it found in our swamplands. Everywhere you look, from Louisiana to Maine, the shoreline grasslands are a sea of towering Kudzu, green in the spring, yellow in the fall. It may have been an interesting visitor at one time, nowadays it's a noxious weed. So far at least, no animals have developed a taste for Kudzu, and no one has figured out a commercial use for it. When an invasive plant of this sort gets introduced, native habitat and its dependent animal life quickly disappear. So, in this situation, nature preservation takes the form of destroying the invader.

|

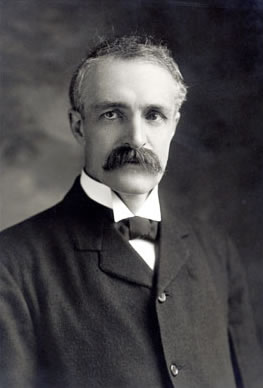

| Charles Darwin |

But where is Charles Darwin in all this? The survival of the fittest would suggest that successful aggressors are generally fitter, so evolution favors the victor. Perhaps swamps are somehow better for being dominated by Kudzu, pollination might be enhanced by killer bees. At first, it might seem so, but if the climate or the environment is destined to be in constantly cycling flux, diversity of species is the characteristic most highly desired. For decades, biologists have puzzled over the surprising speed of adaptation to environmental change. Mutations and minor changes in species seem to be occurring constantly, and most of them are unsuccessful changes. But when ocean currents change, or global warming occurs, or even man-made changes in the environment alter the rules, we hope somewhere a favorable modification of some species has already occurred standing ready to take advantage of the changing environment. Total eradication of species variants, even by other species which are temporarily better adapted, is undesirable. In this view, the preservation of previously successful but now struggling species is a highly worthy project. The meek, so to speak, will someday have their turn, will someday inherit the earth. For a while.

|

| St. Lawrence Seaway map |

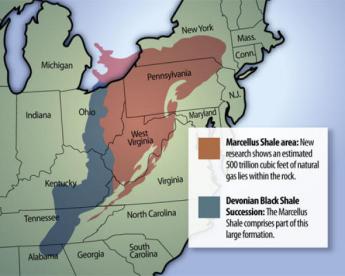

And finally, there are variants of the human species to consider. To be completely satisfying, a commitment to preserving "native" species in the face of aggressive new invaders must apply to our own species. Surely, a devotion to preserving little plants and insects against the relentless flux of the environment does not support a doctrine of driving out Mexican and Chinese immigrants at the first sign of their appearance, like those aggressive Asian eels plaguing the St. Lawrence Seaway?. Here, the answer is yes, and no. For the most part, invasive species are aggressive mainly because they find themselves in an environment which contains no natural enemies. If that is the case, fitting the newcomers into a peaceful equilibrium is a matter of restraining their initial invasion long enough for balance to be restored through the inevitable appearance of natural enemies. So, if we apply our little nature lessons to social and economic issues related to foreign immigration, the goal becomes one of restraining an initial influx to a number which can be comfortably integrated with native tribes and clans. In the meantime, we enjoy the hybrid vigor which flourishes from exposure to new ideas and customs.

In the medium time period, that is. For the long haul, if the immigrant tribes really do have -- not merely a numerical superiority -- a genetic superiority for this environment, perhaps we natives will just have to resign ourselves to retreating into caves.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1219.htm

Big Pharma Loses Momentum

|

| Chemical Heritage Building |

listened to the analysis by G. Steven Burrill, a noted venture capitalist who specializes in this area. The big firms, like Merck, Wyeth, Johnson and Johnson have recently reported disappointing earnings, and it seems they have been reducing their American research divisions, with more use of small niche research firms as subcontractors, both American and foreign. As they tend to reduce their emphasis on research and manufacturing, Steve Burrill feels they will concentrate mainly on marketing. That sounds like good news for Wyeth, with its traditional focus on marketing, and bad news for Merck, which has always been strong in new product development.

|

| G. Steven Burrill |

Burrill also has his eye on the statistic that only 8% of health care spending is devoted to pharmaceuticals, while 40% is spent on nostrums to promote wellness. The sly observation slipped out that if 40% of health spending goes for products of questionable value, just think how big the market would be for new products that really do promote some wellness. So that, in his opinion, is where investors will prosper.

Some of us in the back of the room were troubled by these thoughts. In the first place, the major drug houses have long operated with a financial business plan that takes profits from old established drugs and uses them to pay for research on the new drugs of the future. Small niche companies, that only work on one phase of this cycle, have had difficulty financing expansion and mostly accepted a subsidiary role. You might develop a wonder drug in your garage, but you had to license it to a big pharma concern in order to thrive. The thought pops up that the protracted wait for

|

| PA Drug Industry |

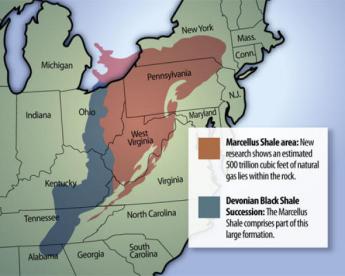

Food and Drug approval might be stretching the old-drug/new-drug interval to the point where patent expiration on the current revenue generators interrupts the internal recycling of profits into new drug research. That's been a threat ever since the passage of the Kefauver Amendment, but a new twist has appeared in the form of a tidal wave of cheap liquidity from the Far East, working its way into venture capital pools and assisting the niche firms with their historical shortages of capital. If that's a significant feature of the present environment, it could fizzle out when the Far East stops pumping liquidity into world markets. A new Premier of Japan might be all it would take, or else a drop in the price of oil. Japan's interest rates are now held below 1%, while a realistic price for oil is $45 a barrel, not $65.

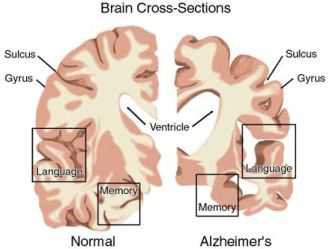

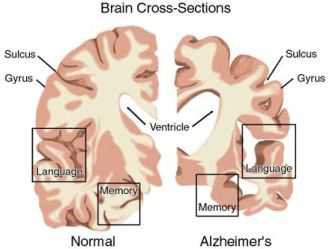

And as far as the promotion of wellness is concerned, that concept might just turn out to be a fad. Congress doesn't try to evaluate scientific trends, but it is very fond of insisting that "if it ain't broke, don't fix it". A major advance in the treatment of cancer and or Alzheimer's Disease might very well dampen Congressional enthusiasm for spending 15% of Gross Domestic Product on what's then left to treat, which would mostly be wellness.

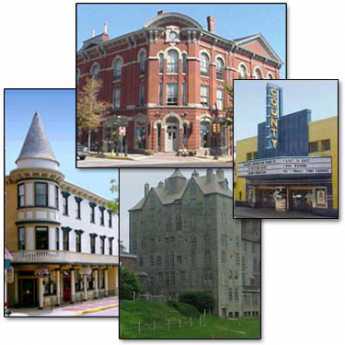

Venturi's Franklin Museum in Franklin Court

|

| Franklin Court Museum |

When Judge Edwin O. Lewis was seized with the idea of making a national monument out of Colonial Philadelphia, he wanted it big. Forty or so years later, it's big all right, but not big enough to encompass the whole of America's most historic square mile. Government ownership in the form of a cross now extends five blocks north from Washington Square to Franklin Square, and four blocks East from Sixth to Second Streets. Restoration and historic display have spread considerably beyond that cross, however, and the Park Service has created ingenious walkways within the working city in the neighborhood. If you thread your way through these walkways, you can stroll for miles within the world of William Penn and Benjamin Franklin. One such unexpected walkway is now called Franklin Court, which essentially cuts from Market to Chestnut Streets, within the block bounded by 3rd and 4th Streets. Hidden in the center is the reconstructed ghost of Franklin's quite large house, sitting in an interior courtyard bounded by a colonial post office, and a newspaper office once operated by Franklin's grandson. And, along the side of the walkway near Chestnut Street, is a fascinating museum of Franklin's personal life, built by no less than Frank Venturi, and operated by Park Rangers in the polished but low-key manner for which the U.S. Park Service is famous.

For some reason, this jewel of a museum has not received the high-powered publicity it deserves. It's off the main Park premises, as we mentioned, and some of the problem has to be attributed to Venturi. As you walk through, you don't expect a huge museum to be there, and it can look pretty inconspicuous as you walk past because it is mostly underground. Take my word for it, it's worth a visit. There are long descending ramps inside the doors, which can be pretty daunting if you are elderly and tired. But, also inconspicuous, there's an elevator if you look around for it. Venturi didn't seem to like windows very much, which is a problem for some people.

There's a movie theater inside there, playing a long list of fascinating documentaries. There's an ingenious automated display of statuettes which utilize spotlights and revolving stages to present Franklin in Parliament, resisting the Stamp Act, Franklin being his charming self before the French monarchs, and the frail dying Franklin getting the Constitutional Convention to approve the document. There are also a variety of ingenious inventions of Franklin's on display in the original, including bifocal glasses, the first storage battery, a simplified clock, several library devices, the Franklin stove, and so on. In some ways, the highlight is the Armonica.

The Armonica is the musical instrument invented by Franklin, for which both Beethoven and Mozart composed special music to exploit its haunting tone. If you ask the nice Park Ranger, she will be flattered to play you a tune on it.

Armonica, Momentarily Mesmerizing

|

| Ben Franklin's Glass Armonica |

Everyone knows Ben Franklin spent a lot of time holding a wine glass. Evidently, he noticed a musical note emerges if you run your finger around the open mouth of the drinking glass, and systematically studied how the tone can be varied by varying the level of liquid in the glass. The same variation in emitted tone relates to variations in the thickness of the glass. So, he set up a series of different sized glasses impaled on a horizontal broomstick, enough to cover three octaves, rotated the broomstick with a treadle like those used for spinning wheels -- and made music. The tone has a haunting penetration to it, which induced both Beethoven and Mozart to write special compositions for the harmonica, and the Eighteenth Century went wild with enthusiasm.

|

| Glass Armonica |

Unfortunately, a number of the young ladies who played the armonica went mad. We now recognize that since the finest crystal glass was used, with very high lead content, the mad ladies were suffering from lead poisoning after repeatedly wetting their fingers on their tongues. As a matter of fact, port wine at that time was stored in lead-lined casks, resulting in the same unfortunate consequences, which included stirring up attacks of gout. Franklin himself was a famous sufferer from gout, which was more likely related to the port wine than playing the harmonica, in his particular case.

Anyway, the reputation for inducing madness added to the spooky sort of sound the instrument made, attracting the attention of a montebank named Franz Anton Mesmer, who falsely claimed to be the father of hypnotism. Mesmer enhanced the society of his stage performances by hypnotizing subjects while an assistant played the harmonica, meanwhile relating all sorts of wild tales about animal magnetism. This was pretty sensational at the time until a young man in an audience suddenly died. It is now speculated that the victim probably had an epileptic seizure, but the news of this public fatal event pretty well finished Mesmer as an evangelist and the harmonica as a musical instrument.

|

| Franklin Court |

There's a replica of an armonica on display in the Franklin Court Museum around 3rd and Chestnut, which we are vigorously assured is not made with leaded crystal glass. The Park Rangers put on two daily performances by request, at noon, and 2:30 PM.

Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution

|

| Richard Arkwright |

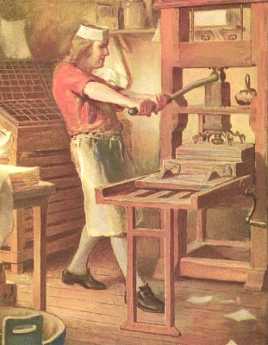

The Industrial Revolution had a lot to do with manufacturing cotton cloth by religious dissenters in the neighborhood of Manchester, England in the Eighteenth Century. What needs more emphasis is the remarkable fact that Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution both originated about the same time, in about the same place. True, the industrializing transformation can be seen in England as early as 1650 and as late as 1880. The Industrial Revolution thus extended before Quakerism was even founded, as well as long after most Quakers had migrated to America. No Quaker names are much mentioned except perhaps for Barclay and Lloyd in banking and insurance, and Cadbury in candy. As far as local history in England's industrial midlands is concerned, the name mentioned most is Richard Arkwright, whose behavior, demeanor and beliefs were anything but Quaker.

He seems to have invented nothing, stealing the patents and ideas of others freely, while disgustingly boasting about his rise from rags to riches. Some would say his skill was in the organization, others would say he imposed an industrial dictatorship on a reluctant agricultural community. He grew rich by coercing orphans, convicts and others he obviously disdained into long, unpleasant, boring and unwelcome labor that largely benefited him, not them. In the course of his strivings, he probably forced Communism to be invented. It is no accident that Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto while in Manchester visiting his friend Friedrich Engels, representing reasonably well the probable attitudes of Arkwright's employees. What Arkwright recognized and focused on was that enormous profits could flow from bringing piecework weaving into factories where machines could do most of the work. Until his time, clothing was mostly made by piecework at home, with middlemen bringing it all together. The trick was to make clothing cheaper by making a lot of it, and making a bigger profit from a lot of small profits. Since the main problem was that peasants intensely disliked indoor confinement around dangerous machines, the industrial revolution in the eyes of Arkwright and his ilk translated into devising ways to tame such semi-wild animals into submission. For their own good.

|

| Charles Babbage |

Distinctive among the numerous religious dissenters in the region, the Quakers taught that it was an enjoyable experience to sit indoors in quiet contemplation. Their children were taught to submit to it at an early age, and their elders frequently exclaimed that it was a blessing when everyone remained quiet, enjoying the silence. Out of the multitude of religious dissenters in the first half of the Seventeenth century, three main groups eventually emerged, the Quakers, the Presbyterians, and the Baptists. Only the Quakers taught that silence was productive and enjoyable; the Calvinist sects leaned toward the idea that sitting on hard English oak was good for the soul, training, and discipline was what kept 'em in line.

|

| babbagemaq.jpg |

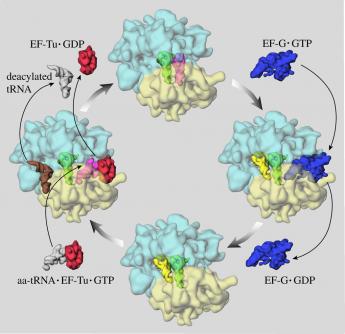

The Quaker idea of fun through daydreaming was peculiarly suitable for the other important feature of the Industrial Revolution that Arkwright and his type were too money-centered to perceive. If workers in a factory were accustomed to sit for hours, thinking about their situation, someone among them was bound to imagine some small improvement to make life more bearable. If such a person was encouraged by example to stand up and announce his insight, eventually the better insights would be adopted for the benefit of all. Two centuries later, the Japanese would call this process one of continuous quality improvement from within the Virtuous Circle. In other cultures, academics now win professional esteem by discovering "win-win behavior", which displaces the zero-sum or win/lose route to success. The novel insight here was that it has become demonstrably possible to prosper without diminishing the prosperity of others. In addition, it was particularly fortunate that many Quaker inhabitants of the Manchester region happened to be watchmakers, or artisans of similar trades that easily evolved into the central facilitators of the new revolution -- becoming inventors, machine makers and engineers.

The power of this whole process was relentless, far from limited to cotton weaving. When Charles Babbage sufficiently contemplated the punched-cards carrying the simple instructions of the knitting machines, he made an intellectual leap to the underlying concept of the tabulating machine. Using what was later called IBM cards, he had the forerunner of the stored-program computer. There were plenty of Arkwrights getting rich in the meantime, and plenty of Marxists stirring up rebellion with the slogan that behind every great fortune is a great crime. But the quiet folk were steadily pushing ahead, relentlessly refining the industrial process through a belief in welcoming the suggestions of everyone.

Baruch Blumberg, Renaissance Man

|

| College of Physicians |

Baruch Blumberg may be an octogenarian, but he radiates vigor and good health; his current intellectual interests are invariably on the cutting edge. He currently serves as the president of the American Philosophical Society, was for five years the Master of Balliol College at Oxford, was the Director of Astrobiology at NASA -- all of them after he had won the Nobel Prize in Medicine, and retired from his laboratory. He likes to run and bicycle, with a long history of disconcerting the populace of China, India, and Africa with early morning forays. His undergraduate major was physics, with graduate work in mathematics. He went to medical school at his father's suggestion.

|

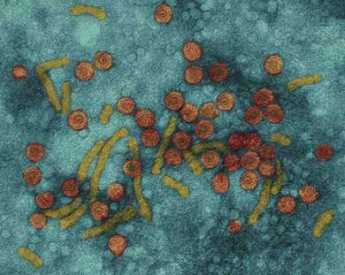

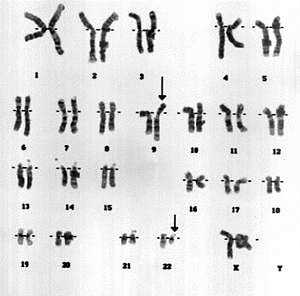

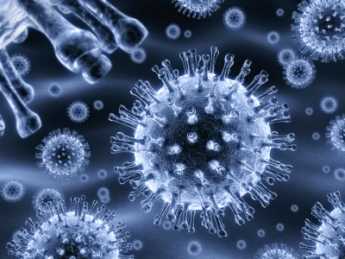

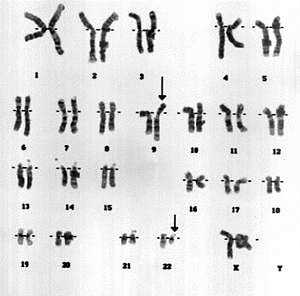

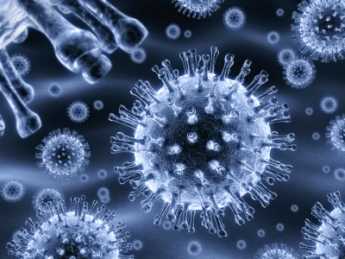

| Hepatitis B |

The Nobel Prize was awarded for the discovery of the Hepatitis B virus, for which he developed a highly successful vaccine. It has been estimated that there are 375 million people in the world infected with this virus, and it leads in time to liver cancer, the most common form of cancer in Asia. If you set about to stamp out disease and save lives, it's advantageous to do it with an extremely prevalent disease. And then there are some surprising side-benefits. For some reason, women who are infected with Hepatitis B produce a disproportionately large number of male offspring, so that vast immunization programs in Asia are now starting to result in a larger proportion of females in the population. The lack of female children in Asian families has long been attributed to selective abortion, so it's satisfying to see an abatement of that particular slander.

|

| Baruch Blumberg |

Blumberg has twice been invited to deliver a lecture to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The first was a description of the problems of space travel. The second was a discussion of current trends in medical genetics. It seems that gene mutations only occasionally cause disease directly. The much more important genetic factor in disease affects the ability of some people to resist particular diseases and makes others more likely to be a victim. Hepatitis B? Well, that's so yesterday.

Valentine Tours, Right Here in River City

|

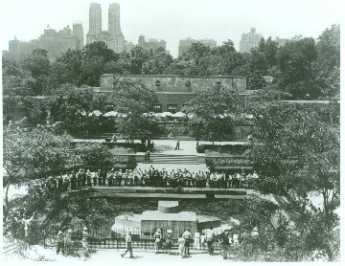

| Zoo Opening |

The Philadelphia Zoo claims to be the oldest zoo in America, although New York's Central Park Zoo is older. The explanation for this puzzle is that the Philadelphia Zoo was chartered by the legislature in 1859, but its opening was delayed by the Civil War until 1874. Meanwhile, the Central Park Zoo was opened in 1862. One hopes the true priorities are perfectly clear, although the Romans had zoos, and Montezuma had a spectacularly big one when Cortes arrived. Why all this wandering prologue before a discussion of a Valentine Tour? Well, since the internet is so plagued by a dispute about what is suitable for children to read, it is not clear that our Zoo's legitimate activities would escape hostile robot detection, banishment by Google, or the like if we talk about them on this website. So we will be indirect.

|

| Central Park NYC |

It is related that it was the women's committee of the zoo who first proposed an adult zoo camp which now goes by the name of Valentine Tours. For a modest fee of $75, it is possible to join this activity, involving discussions and demonstrations of the varieties and complexities of vertebrate reproduction. It is not only the Philadelphia public which needs education in these matters. One of the main sources of infertility among rhinos and gorillas derives from the surprising fact that they must be taught what to do. Apparently, when removed from the voyeur opportunities of their native environment, these monsters can't figure out what is expected of them.

John Bernard, a docent at the zoo for 18 years, has written a book about the varieties of romantic experiences and recently addressed the Right Angle Club on the matter. He tells of four-footers and hundred-pounders, and the like. Apparently, male elephants make their ladies wait in line for their turn, male gorillas have several girlfriends at all times, and male lions are so occupied with demands made on them that they scarcely do anything else. Bats cavort upside down, eagles lock claws and fall out of the sky, polar bears starve for months afterward. The fascination just goes on and on.

The inside details of some recent events are also revealed. Male African elephants go into a variant of heat that lasts three months and makes them dangerous to be around. That's really why the zoo recently decided to get rid of its elephant collection. Orangutans will rape a female zoo employee if given a chance. The Women's Committee of the Zoo is certainly to be thanked for alerting us. For more details, stump up the $75 and take a Valentine Tour.

Fernery

|

| Gardeners |

As explained by the curator of The Morris Arboretum, there are a few other ferneries in the world, but the Morris has the only Victorian fernery still in existence in North America. That doesn't count a few shops that sell ferns and call themselves ferneries; we're talking about the rich man's expensive hobby of collecting rare examples of the fern family in an elaborate structure. That's called a Victorian fernery. The one we have in our neighborhood is really pretty interesting; worth a trip to Chestnut Hill to see it.

Although our fernery was first built by the siblings John and Lydia Morris, it was rebuilt at truly substantial cost by the philanthropist Dorrance Hamilton. It is partly above ground as a sort of greenhouse, and partly below ground, with goldfish and bridges over its pond. Maintaining an even temperature is accomplished by a complicated arrangement of heating pipes. The temperature the gardener chooses affects both the heating bill and the species of fern that will thrive there. You could go for 90 degrees, but practical considerations led to the choice of 58 degrees. The prevailing humidity will affect whether the fern reproduction is sexual or asexual, a source of great excitement in 1840, but survivors of Haight-Asbury are often more complacent on the humidity point.

There are little ferns, big ferns, tree ferns, green ferns, and not-so-green ferns; the known extent of ferns runs to around five hundred species. Not all of them can be found in Chestnut Hill, what with humidity and all, but there are enough to make a very attractive and interesting display. For botanists, this is a must-see exhibit. For the rest of us, it's probably the only one of its kind we will ever see, a jewel in Philadelphia's crown, and shame on you if you pass it by.

Morris Arboretum

The former estate of John and Lydia Morris is run as a public arboretum, one of the finest in North America.

|

Morris is the commonest Philadelphia name in the Social Register, derived largely from two unrelated Colonial families. In addition to their city mansions, both families had country estates. The country estate once belonging to the Revolutionary banker Robert Morris was Lemon Hill, just next to the Art Museum, where Fairmount Park begins. But way up at the far end of the Park, beyond Chestnut Hill, was Compton, the summer house of John and his sister Lydia Morris. This Morris family had made a fortune in iron and steel manufacture and were firmly Quaker. Both John Morris and his sister were interested in botany and had evidently decided to leave Compton to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a public arboretum. John died first, leaving final decisions to Lydia. As the story is now related, Lydia had a heated discussion with Fiske Kimball, at the end of which the Art Museum deal was off. She turned to her neighbor Thomas Sovereign Gates for advice, and the arboretum is now spoken of as the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania. It is also the official arboretum of the State of Pennsylvania. To be precise, the Morris Arboretum is a free-standing trust administered by the University, with the effect that five trustees provide legal assurance that the property will be managed in a way the Morrises would have wished. In Quaker parlance, Lydia possessed "steely meekness."

A public arboretum is sort of an outdoor museum of trees, bushes, and flowers, with an indirect consequence that many museum visitors take home ideas for their own gardens. Local commercial nurseries tend to learn here what is popular and what grows well in the region, so there emerges an informal collective vision of what is fashionable, scalable, and growable, with the many gardeners in the region interacting in a huge botanical conversation. The Morris Arboretum and two or three others like it go a step further. There are two regions of the world, Anatolia and China-Korea-Japan, with much the same latitude and climate as the East Coast of America. Expeditions have gone back and forth between these regions for a century, transporting novel and particularly hardy or disease-resistant specimens. An especially useful feature is that Japan and parts of Korea were never covered with glaciers, hence have many species found nowhere else in the temperate zone. Hybrids are developed among similar species found on different continents, and variants are found which particularly attract or repel the insects characteristic of each region. The Morris Arboretum is thus at the center of a worldwide mixture of horticulture and stylish outdoor fashion, affecting millions of home gardeners who may never have heard of the place.

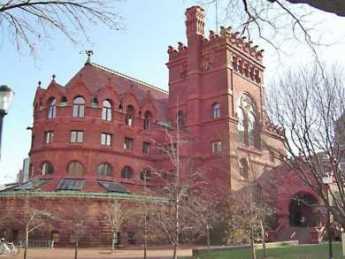

The University Museum: Frozen in Concrete

|

| King Tut |

Recently, a charming archeology scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, Leslie Ann Warden, entertained the Right Angle Club with the interesting history of King Tut. Interest in this subject is currently heightened by a traveling exhibit of the tomb relics currently on elegant display at the Franklin Institute. However, Philadelphia also has a permanent exhibition of Egyptian artefacts lodged in the University Museum. Since this museum is the second largest archaeology museum in the world, after the British Museum, that makes it the largest in America. An interesting sidelight is that Ms. Warden spoke in the grill room of the Racquet Club, which was the first effort by William Mercer to use "Mercer" tiles in a building. Mercer at that time was the curator of the University Museum. We learned from Ms. Warden that King Tutankhamen was unknown before his tomb was discovered, all records of this part of the Egyptian dynasty having been lost or deliberately obliterated by successors. Therefore, the discovery of these magnificent art objects started a massive expansion of scholarship about the entire Third Millenium.

|

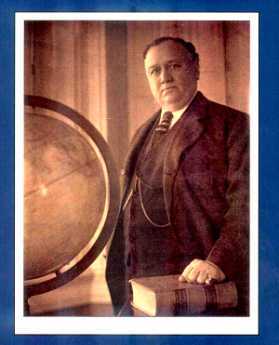

| William Pepper |

The establishment of the University Museum around 1890 was apparently mostly due to the enthusiasm of William Pepper, then Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. What seems to have got Pepper going was an expedition to Iraq, the place where civilization began, in Mesopotamia. The relics brought back from this celebrated effort needed a home, and Pepper decided it had to be here. One famous philanthropist after another, often in the role of Chairman of the Board of Trustees, carried on the tradition after Pepper's premature death. Some of them have their names on buildings, some declined. To a notable degree, the feeling of special possession was exemplified by Alexander Stirling Calder, who turned the statues in the garden to face inward rather than out toward the street. Asked whether a mistake had been made, he is said to have replied that due to the Museum's withdrawn character, it was more appropriate for the world to face the Museum. No more icily accurate comment has ever been made about the University's relation to its city neighbors.

The real knock about the Museum is that too much has been crowded into too little real estate, and the fault lies with the automobile. After the University outgrew its space at 9th and Market around 1870, moving then to West Philadelphia, the architects and the donors originally envisioned a grand boulevard of culture stretching from the South Street bridge many blocks westward. The Museum, Franklin Field, Irvine Auditorium, The University Hospital were to be the start of an imposing array of culture. Unfortunately, that was a horse-drawn conception, soon to be overwhelmed by the worst traffic jam in the city. The Schuylkill Expressway was the final blow, setting huge auto-oriented structures in place where their easy removal became difficult to imagine. The 1929 stock crash, followed by confiscatory income and estate tax rates, merely emphasized the plain fact that restoring the grand vision was beyond the ordinary aspirations of even massive private wealth. Transforming the imposing plazas of the University Museum into parking garages was probably a result of excessive despair, but if you have ever tried to find a place to park in that region you can somewhat sympathize with the small-mindedness which prompted it. Bringing back this region is going to require immense vision and resources, neither of which is exactly thrusting itself forward at present. So, unfortunately, one of the central cultural jewels of the City is buried in the midst of an impenetrable thicket of concrete and speeding automobiles, too big to move, too small to burst its bonds.

It's well worth a lot of anybody's time, and many visits. If you can find a way to get there.

Tree Huggers: Delaware Valley College

|

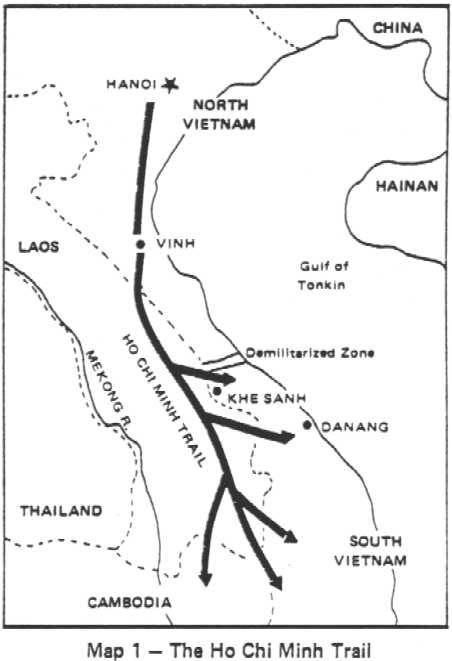

| Doylestown, PA |

At the time when Philadelphia and New York were both occupied by the British during the Revolutionary War, a backwoods highway connected the thirteen colonies. Doylestown is 35 miles due north of Philadelphia City Hall, at the point of intersection of this variant of the Ho Chi Minh Trail with the path which Philadelphia Tories took in their flight to Kingston, Ontario. No doubt there were some interesting conversations in Mr. Doyle's tavern at the crossroads.

Doylestown is also on the invisible border between the hegemonies of Philadelphia and New York, where descendants of German and Quaker farmers make a cautious contact with the distinctly non-Quaker artists and writers fleeing south from New York. James Michener and Pearl Buck once represented Philadelphia in the cultural stew with New Yorker ex-patriots, Somehow in this interface, a place is found for the Delaware Valley College, which started life in 1896 with Jewish founders of the National Farm School. The original board of trustees included such names as Gimbel, Lit, Snellenburg, and Erlanger, but the three-year curriculum was entirely agricultural. The founder himself was Joseph Krauskopf, who got the idea after an inspiring interview with Count Leo Tolstoy.

|

| Baruch Blumberg |

From a single building which served as classroom and dormitory, the college has grown into a four-year institution in numerous buildings scattered over a 570-acre plot with a second 120-acre farm in Montgomery County. The school is determinedly non-sectarian, and for forty years has been coeducational. It has had several changes of name, from the National Farm School, eventually to its present name. The curriculum has expanded as well, with masters degree programs in business and education. Baruch Blumberg, the Nobel Prize winner in Medicine, maintains an office there, and it is clear the college means to shift its emphasis toward the scientific basis of agriculture and the environment. It's also pretty clear that rising agricultural prices will soon re-establish agriculture as a dominant feature of our economy, although agriculture in the modern sense is quite a distance from farming in the old sense, and requires a different sort of educational preparation.

The Right Angle Club of Philadelphia recently heard from Joshua Feldstein the chairman of the board of trustees, and the brand-new president, just moving in from Columbia University. Sixty-eight years of driving ambition is personified in one, and the bright shining future in the other. We wish them well.

By the way, the tree hugger nickname comes from a campus tradition of this college, very much an active ceremony, of hugging the 400-year-old oak standing beside the president's house on the campus. The College, of course, is 250 years younger than the tree.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1295.htm

Exit, Pursued by a Bear

|

| John Kastor |

Everybody ends up getting fired in a recent book by John Kastor about recent events at the University of Pennsylvania just like everybody ending up dead in an Elizabethan play. The vital difference, of course, is that the dramatis personae at Penn can still relate to a bewildered audience their own versions of those grand events. To protect himself, the author peppers his book with more footnotes than a Ph.D. thesis. And thousands of stakeholders at the University can now realize that during those eventful times they were as clueless as Rosencranz and Guildenstern.

One basic fact about that institution is that the medical school spends three-quarters of the entire university budget. That leads to grudges in the little law school, the little engineering school, and the little president's office, as they knuckle under to the Golden Rule. The department chairman with the gold makes the rules. Since most of that gold comes from research grants, hence ultimately from the federal government, the medical students and the teaching faculty don't have the same power they had during the Vietnam War era, either. Although medical school tuition imposes a crushing burden on the students and their families, leading to debts close to a quarter of a million dollars apiece, the tuition money doesn't amount to much in the university scheme of things, either. In some schools, tuition amounts to two percent of the medical school budget. You could eliminate the students entirely and not see much difference in the "school".

Unfortunately, when you become dependent on government grants, you find they can suddenly be terminated, or awarded without funding, or held up for several months by Congressional bickering. Meanwhile, there are salaries to pay, contracts to fulfill. Even if you can furlough some of the staff, it's not easy to see what you do about a thirty-year mortgage on a research building when there is a lull in its research funding. If you try to save money, the granting agency will try to get it back; they aren't authorized to make grants to be squirreled away. If you shift money to unauthorized uses, you risk going to jail. And yet, if you don't do something along those lines, the whole enterprise can collapse.

Having said that much to be fair, it is still uncomfortable to see the financial transparency of our most valued nonprofit institutions vanish behind a Byzantine fog of secrecy, out of which arise the magnificent towers of new buildings, and in front of which an occasional limousine is to be observed. No wonder the research scientists feel the constant pressure to produce. A Nobel Prize every ten years, or so, would go a long way toward quieting envious remarks from the liberal arts faculty.

Housed in those ivy towers are three institutions, the teaching hospital, the medical school, and the university, with three boards of trustees, and at least three ruling potentates. At irregular intervals, congressional committees do things to the Budget Reconciliation Act which enrich one of the three components of the institution or suddenly impoverish another, or both. Integration of the three under one governance sounds plausible until you notice how radically different is the mission of each one. You can take a big building away from one component and rent it back to them, and things like that, but you can't do it without starting whispers about Enron. You can gather up surplus funds from one of them during the decade of the eighties, but you have trouble giving it back twenty years later. Officials at Blue Cross come snooping to see if health insurance premiums are passing through this shell game, ultimately paying salaries in the department of English Literature. Everybody distrusts everybody else, somebody sasses somebody, and everybody gets fired.

Nothing unusual about that. It happens at every medical school.

B. Franklin and Daylight Savings

|

| Daylight Saving Time |

Ben Franklin's father was a candle maker working out of his home. Little Benjamin was thus in a position to watch the rise and fall of candle sales with each passing season; it must have been a central fact of that household's economy. Many years later when he was Ambassador to France, the suggestion of Daylight Savings Time was likely less a demonstration of his ingenuity than a testimony to his powers of observation and reflection.

Now, over two centuries later than that, the point is being raised that what with Nintendo and television and all, daylight time may actually cause more consumption of electrical energy than it saves. It's a striking thought, even quite a revolutionary one. Until you remember that Franklin, more than any one person, also discovered electricity.

Philosophy Means Science in Philadelphia

|

| American Philosophical Society Seal |

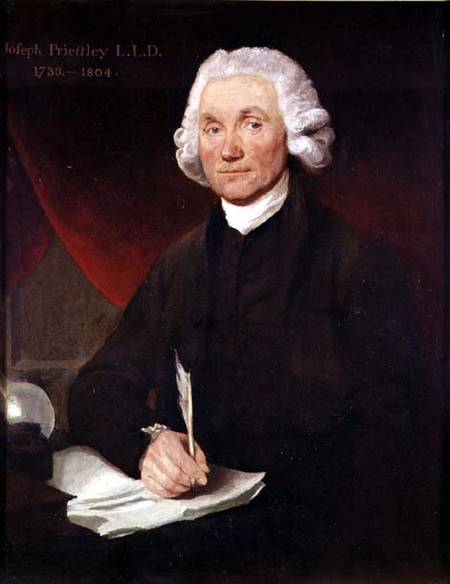

In the age of the Enlightenment, science was called natural philosophy; that accounts for the present custom of awarding PhD. degrees in chemistry and botany. The sort of thing which interested Ralph Waldo Emerson was called moral philosophy, and you will have to visit some other place than the A.P.S. if that is what interests you. Roy E. Goodman is presently the Curator of Printed Material (some would say he was chief librarian) at the American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin who was clearly the most eminent scientist of his day, having discovered and explained the nature of electricity.

|

| Roy E. Goodman |

Roy Goodman is descended from cowboys and rodeo stars, but in spite of that he gave an entertaining talk recently at the Right Angle Club about this society devoted to useful knowledge, this oldest publishing house and scholarly society in America, once the home of the U.S. Patent Office, and scientific library and museum. They have many rare items in their collection, but the unifying theme is not a rarity, but curiosity. You might say some of the items reflect the whimsy of Franklin, but it would be fairer to say it is an enduring monument to Franklin's universal curiosity about all things.

|

| Nobel Prize Medal |

There are about 900 members of APS, about 800 of them Americans, about 100 of them winners of a Nobel Prize. Let's just make a little list of a very few notables in the past and present membership. Start with the first four Presidents of the United States, add Alexander Hamilton and Lafayette, David Rittenhouse and Francis Hopkinson and you get the idea that Founding Fathers got in early. Robert Fulton, Lewis and Clark, Alexander Humboldt, John Marshall were early members, and more recent ones were Madame Curie,

Vanishing Honey Bees

|

| Professor May Berenbaum |

At the Wagner Free Institute, Professor May Berenbaum of the University of Illinois described a mystery disaster which suddenly cut the honey bee population in half during 2008. The nation's bee experts convened at emergency meetings and shared available information to try to figure out what happened. While the matter is not entirely clear, it appears that whole colonies of bees declined because the forager type of worker bee selectively disappeared. No bodies were found in the hives, and the other components of bee colonies were apparently unaffected. Foraging is a stage in the life history of worker bees which precedes their becoming honey and honeycomb workers within the hive, so a disaster for younger worker bees rapidly diminishes the older population of hive workers. Worker bees are sterile females; the fertile queens and drones are apparently unaffected. Speculation as to what has happened to American worker bees has centered on some new pesticides (neonicotinoids) and an Israeli parasite, both of which were new to the scene in the past couple of years.

|

| Honey Bee's |

Most people have little appreciation of the seriousness of this sudden problem. The price of honey can of course be expected to soar, but honey production is now only a small part of the modern bee industry. Three quarters of the revenue of beekeepers is derived from artificial pollination of flowering food plants, usually by trucking hundreds of hives from one region to another, as various food plants come into blossom. In turn, many crops are highly dependent on these bees to supplement wind pollination. The almond crop, the avacado crop, and sesame seeds are all highly dependent on honey bee pollination. The economic effects of a permanent decline in honey bees could have a serious economic effect.

Professor Berenbaum is a Philadelphia girl, having been born in Levittown and educated in the region. She's a charming lady, starting off the lecture by commenting on the old birds and bees tradition. In her view, American children already know more about human sexual behavior than they know about bees.

As a side note, the "Father of Modern Beekeeping" was theReverend Lorenzo Langstroth, also born in Philadelphia. While continuing his active ministry, Langstroth learned that bees would react with comb formation to crevices in the hive according to the width of the crevice. From this, he developed the now-standard rectangular hive with movable partitions, confining the queen bee to the bottom section by laying a screen above it with openings large enough to permit the worker bees to move through, but too small for the queen. Since the moveable partitions could be removed without shaking the whole hive and agitating the bees, beekeeping without hive destruction became practical. An additional feature was that the upper sections contained honey without bee larvae, and could be removed as filled, without reducing the population of bees in the hive. Langstroth's introduction of smoke blown into the hive had the effect of quieting the insects still further. Langstroth in 1848 published an instruction manual for beekeeping which is still in wide use because there was thereafter very little room for further beekeeping innovation. For many decades, honey became the main sweetener in American households. Unfortunately, the present mysterious loss of worker bees has pushed the price of a small jar to more than $40, steadily rising. One hopes the cause and cure of this malady will soon be found.

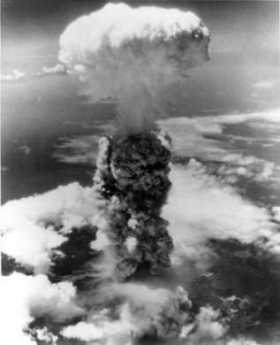

In the spirit of helpfulness, the following suggestions are offered: disappearance of bees without dead bodies could be explained by insecticide toxicity somewhat better than by disease, because many diseased bees could be expected to find their way back to the hive, while poisoned ones could be killed quickly at some distance from the hive and never make it back. And one further thought is that failure of the bees to be born would explain vanished bees without corpses just as well as distant insecticides would. And the decline of feral bee populations starting in 1945 brings up a possible association with atom bomb tests, just as was seen in the sudden change in the world-wide pattern of human thyroid cancers. Just a suggestion.

Franklin Institute: Hawks and Galileo

Galileo's own little telescope, along with many beautiful and historic instruments of the time are owned by the Medici family in Florence. Their collection of paintings are in the Uffizi, but you have to go to Italy to see them. However, the instrument museum is undergoing repairs, and the Franklin Institute jumped at the chance to put the materials on display while the Medici's weren't using them. The exhibit is large and splendid, including a great many astronomical and surveying instruments which were copied from the Arabs but with exquisite Florentine workmanship. You aren't allowed to look through Galileo's telescope, but a copy is provided, focused on the nine moons of Jupiter. Galileo was angling for a patronage job, so he named the first four moons after individual Medici nobles, a process not too different from what can now be noticed on K Street in Washington, any day. The museum arranged telephone number for cell phones so you can walk around with a guided tour in your hand; pretty neat. Those who have seen the recent play called Galileo will know that the old gent really didn't invent the telescope, and the Dutch are pretty sour about him because they did. But he improved it quite a bit, making his famous astronomical discoveries possible, getting him into trouble with the Jesuits, and forcing his pal the Pope to put him under house arrest even though the Pope surely knew Galileo was right. The earth goes around the sun, not the sun around the earth, but Galileo was pretty snotty about it and probably deserved some sort of rebuke.

The Franklin Institute doesn't make a point of it, but the scientific method was discovered around that time, and around that neighborhood. It's unclear whether Galileo invented the scientific method or not, but no one else claims the credit so it's a possibility. Anyone who has taken a course in Physics knows that Galileo went to the leaning tower of Pisa and proved that nickel would drop just as fast as an anvil, and made many other fundamental discoveries beyond any serious challenge. The scientific method would be a much more fundamental discovery that the sun/earth issue, which belongs to Copernicus in any event. But Galileo's habit of overclaiming in the telescope invention sort of clinches everybody's determination not to give him credit for Science, unless serious proof is forthcoming, and maybe not even then.

|

| Hawk |

While you are at the F. I. looking at this exhibit, it might be possible to look at the brace of red-tailed hawks who decided to build a nest on the window sill of the board room and bring up a family of real Philadelphia hawks. The young ones are bigger than you would guess, and fuzzy all over. The museum put up a monitor and displays the nest on the Internet. We patched it into this page, to save you the trouble. Hurry up, though. Galileo will be there for three months, but the hawk chicks will probably fly away in a few weeks.

Click here to see the Hawks Live

B. Franklin, Scientist

|

| Franklin Institute |

FROM time to time, the Franklin Institute has a display of its own and other museums' collections of the scientific instruments of Benjamin Franklin. It's well worth anybody's visit when it is available because the beauty and craftsmanship of these instruments alone make them remarkable works of art. Franklin was financially able to retire at the age of 42, and it tells you something of the 18th-century culture that Franklin took up scientific experiments in order to be like other independently wealthy gentlemen. Science, or natural philosophy, this seems to have been in a class with getting a coat of arms and having his portrait painted, all of which cheapens our view of Franklin as a scientist.

|

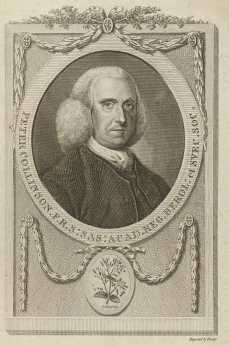

| Peter Collinson, F.R.S. |

In fact, Franklin was conducting an active correspondence with other scientists interested in electricity for many years, in particular, one Peter Collinson, F.R.S. in London. Collinson collected thirteen of Franklin's letters about his experiments, the earliest dated 1747, and printed them in 1751 as an 86-page book called Experiments and Observations about Electricity . By 1769, several more letters expanded the book to 150 pages, almost all of them describing reproducible experiments in great detail. The kite and key episode are described, but soberly and sparingly. Without making the point too graphically, an appendix was added describing how lightning had been used to kill some turkeys, so a somewhat increased power would probably be enough to kill a person. Franklin recognized that something was moving from here to there, that it had positive and negative charges, and that it was possible to store it up in a storage battery. He recognized the difference between substances that would conduct electricity and other substances that would act as insulators. Later on, he would discover that the torpedo fish stores and transmits electricity, suggesting that somehow animals made and used electricity as part of life. And of course, he put the discoveries to practical use as lightning rods, which he refused to patent.

|

| Madame Helvetius |

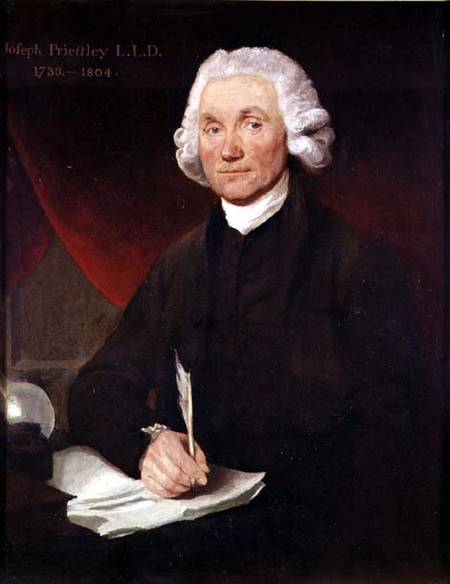

By the time he went to England and France as a negotiator, his wide acquaintanceship in the scientific world was happy to introduce him to other famous people, like kings, Voltaire, Mozart, and Madame Helvetius the wife of the Swiss philosopher, the only woman to whom he is known to have made a proposal of marriage. When someone mentioned standing before a king, he replied he had stood before five of them. King Louis XVI, for example, appointed Franklin to a four-man committee to investigate hypnotism, then being touted as "animal magnetism" by Franz Mesmer. The other three committee members were unfortunately also destined to become acquainted with the guillotine: Brother Joseph-Ignace Guillotin himself, and two future victims of the invention, Antoine Lavoisier the discoverer of oxygen, and Jean Sylvain Bailly who first calculated the course of Halley's Comet, not to mention Louis XVI himself. It is not easy to think of any other scientist who was able to mix his scientific fame with changing international history, acquiring in the process the sobriquet of the founder of the American diplomatic corps. But then, he was witty as well as smart, and his career is a warning to those who now hope to devote their whole lives to being admitted to a prestige college and then coasting on its reputation. Franklin, it should be remembered, dropped out of school after the second grade.

Barringer Crater in Winslow AZ

|

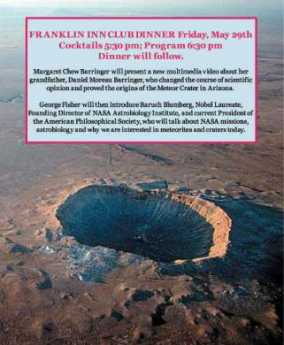

| Barringer Crater |

There are several big holes in the ground, clustered fairly close together in the high plains of northern Arizona. One of them is an extinct volcano, one is a sink-hole where the ground collapsed over an empty aquifer, one is the Grand Canyon. And one of them is the Barringer meteorite crater, about a mile wide and half a mile deep. In the summer, environmental temperatures above 105 degrees are fairly common, and as I have reason to know, the crater can be covered with two feet of snow in February. It's near the town of Winslow, and was called the Winslow crater in a popular song, Take it Easy by The Eagles of ten or more years ago, as well as being featured for the last fifteen minutes of a movie called Starman that is still reasonably exciting to watch.

|

| Daniel Moreau Barringer (1860-1929) |

As recently explained by Margot Barringer at a dinner at the Franklin Inn Club last week, the crater was explored, and purchased, by her grandfather, Daniel Moreau Barringer (1860-1929), who had made a fortune in mining discoveries and could afford to buy a big hole in the ground. Daniel Barringer was a Princeton classmate and friend of Woodrow Wilson and Cyrus McCormick, as well as a friend of Theodore Roosevelt. Barringer's young son owned a .22 rifle and amused himself shooting at mud puddles. One day, he exclaimed that the shapes of the bullet holes in the ground were exactly like the shape of the Arizona hole; they all had a circular opening no matter what direction the bullet came from. From that came the idea that the crater was not an extinct volcano as many local natives believed, but the crater of a meteor, since the mouth of the crater would remain roughly circular regardless of the direction of the impact. That shape helps explain the confusion with the mouth of a volcano. While generally accepted today, meteor craters were a comparatively recent idea at that time. Geologists like to argue a lot -- Barringer himself was particularly vocal-- and it took quite a few years before the meteor theory of this particular crater was generally accepted. Poor Barringer became obsessed with the idea that commercial deposits of iron ore could be found if you dug deeply in or around the crater, but it wasn't true, and he essentially lost his fortune trying to dig 28 deep holes there. Sadly, he died of a heart attack very shortly after the scientific world finally agreed with his Theory of the crater's formation. The decline in the family fortune may also have been related to the significant year -- 1929 -- of his death. Two other granddaughters have written an interesting book about this personal and geological struggle.

|

| Baruch Blumberg |

At the Franklin Inn dinner, Baruch Blumberg (who had won a Nobel Prize for the discovery of the hepatitis B virus and its vaccine) then offered a fascinating discussion of meteors and craters. He's President of theAmerican Philosophical Society, but his credentials for this topic come from his second career as Director of the Astrobiology Institute of NASA. He tells us it might be better to call it an asteroid crater since most meteors are circulating asteroids that lose their way and come crashing through our atmosphere. There are quite a few asteroids floating around reasonably close nearby, and more big ones can be expected to drop in on us about once every two thousand years in the future. NASA seems to have given a lot of thought to this topic, including a theory that the moon was once a piece of the earth which got knocked loose by a big asteroid hitting us at some distant time in the past. There's a big crater in Siberia, and it is thought that dinosaurs were exterminated by a huge asteroid hitting the Yucatan. When you look at the surface of the moon, you see that lots and lots of asteroids have been flying about, but most of the evidence has been eroded away.

If there is a serious danger of another big one hitting us, and smart people can calculate its future path, what can we do about it? Well, the people at NASA have given that some serious thought. Attaching an outboard motor to the asteroid doesn't sound very workable, but painting one side of it white might be because white will reflect light and heat and push the asteroid in some different direction. And shooting big bombs at it to change its course might be practical. Right now, all of the asteroids seem to be headed in harmless directions, but it pays to be prepared.

The idea that iron and nickel could be found in the crater comes from knowing, Lord knows how that the center of the earth is molten iron. That creates the theory that asteroids might be mostly made of iron, burying commercial amounts of it underground when they hit. Unfortunately, the size calculations are all wrong, and Barringer's son had it about right that a .22 bullet would kick up a much larger hole than itself. Anyway, some consolation lies in 250,000 paying visitors to the crater every year, and an occasional movie or NASA experiment paying for temporary use. The downside of economics is that Barringer had eight children, and lots of them had lots of children. Fecundity seems to be a characteristic of most Barringers; one member of the clan estimated at least a thousand living relatives at one remove or another, all of them presumably willing to share in the gate receipts if some learned counsel advises an aggressive approach.

So, since it more or less belongs to Philadelphia, more visits to this crater are recommended. Except, perhaps, in February. April, when the desert is in bloom, might be more enjoyable.

REFERENCES

| A Grand Obsession: Daniel Moreau Barringer and His Crater: Nancy Southgate: ASIN: B0006SAYHU | Amazon |

Geckos: Academy of Natural Sciences brings Mini Dinosaurs

|

| Gecko |

FRIENDS who spent time in Vietnam have a lasting memory of lizards stuck to the ceiling, catching flies with their tongues. Those animals are named geckos, one of the oldest and probably most varied families of reptiles, but confined to the Southern hemisphere. Fossils have been found containing geckos from fifty million years ago, so they were here before the big dinosaurs were wiped out, when the Yucatan was probably struck by an asteroid.

|

| Anthony Geneva |

There was a time when Africa, India, South America and Antarctica were united in one monstrously big continent, and the many varieties of gecko are scattered over the land masses which originally made that up. At least this is the way Anthony Geneva explains it to visitors to the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th and Ben Franklin Parkway. There are no geckos to be found naturally in Philadelphia. Philadelphians hardly need reminding that the first dinosaur bones, ever, were discovered in Haddonfield NJ, and were soon taken to the Academy for permanent display. Ever since that time, the Academy's collection of dinosaurs has expanded, and are the things with the most impact on school-age visitors. The Academy is getting ready to celebrate its 200th anniversary in a few years, however, and contains much more than dinosaur bones, including extensive research facilities with world-famous scientists at work in them. In any event, the dinosaur image is a clear metaphor for the present display of little reptiles that look like dinosaurs, whatever the DNA trail may be. The main exhibition area is currently filled with dozens of glass display cases containing live geckos, and the little rascals are so good at camouflage that you have to hunt carefully for them before they suddenly seem to emerge from the shadows. There are white ones, black ones, bright green and bright orange ones, speckled in all sorts of weird patterns. They make sounds resembling bird songs, and the term gecko is a native word referring to such sounds. The Academy displays these gecko-noises for visitors who are invited to push twenty or so buttons. Geckos move, but suddenly, and probably for some predatory purpose. If you are really into geckos, you focus on their feet.

|

| Gecko |

The variety of toe and foot shape is almost infinite and seems more so if you have a magnifying lens. The foot pads terminate in different kinds of extremely fine hairs, and that's their big secret. Those hairs are so fine the molecules of the foot and the molecules of the wall or ceiling attract each other magnetically. Since no energy is expended in the adherence, the gecko can remain attached to a wall or ceiling indefinitely, even after the gecko dies. But, by raising the angle of contact to thirty degrees, the foot detaches, and the little rascals can scoot along very rapidly, upside down. At present, there is a great deal of commercial and maybe military interest in clarifying the secrets of this adhesion. To be industrially useful, the footpad size would have to scale up to much larger dimensions, but just imagine gluing together the vessel ruptures and aneurysms inside the brain as we now do in a cumbersome manner with chicken-wire stents, just one example that quickly occurs to a visitor. If these little fellows figured out how to make these reversible adhesives fifty million years ago, our scientists ought to be able to imitate them.

Drop around to visit the Academy. It's filled with amazing things like this.

The University City

|

| University of Pennsylvania |

In 1920, the University of Pennsylvania graduated 34 students with B.A. degrees, and 134 with M.D. degrees. Today, the campus is a little self-contained city of 50,000 inhabitants. The transformation of the campus during that period is an outward expression of revolutionary expansion of the student body, involving demolitions, restorations, new construction. And the nearly constant shortage of parking space.

|

| David Hollenberg |

David Hollenberg, the University Architect, recently gave the Franklin Inn Club an interesting description of the University from the point of view of bricks and mortar. Since almost every building on the campus is undergoing or plans to undergo a major building project, he had a lot of material to cover. The disappearance of the railroad-based industrial area of West Philadelphia has been an economic problem for the city, but of course, this abundance of vacant land has created a major opportunity for the University of Pennsylvania. One reflection of this abundance is the opportunity to become the developer for much of the whole region around the campus, working with private developers who wish to be in the University area, and are therefore willing to coordinate their plans with those of the University. It's a remarkable opportunity. Since it comes at the time of a major economic downturn, one can only hope that the University does not impoverish itself taking advantage of this good luck.

|

| Jonathan E. Rhoads |

As the graduation statistics illustrate, not so long ago the University was largely a medical school, with appendages. There are rumors of considerable friction from time to time, between the President of the University and the Dean of the Medical School as to who was boss; it is easy to imagine the trustees swinging from one side to the other. The most notable Provost of the University in modern times was Jonathan Rhoads, who also happened to be Professor of Surgery. If you know Quakers, you know that disputes were seldom rancorous. And if you know Jonathan, you know he almost always won the disputes.

|

| Cira Center |

While today, the dominant change is caused by the Cira Center buildings and the acquisition of the former Post Office building, it is well to keep in mind that the new Cancer Center is a billion-dollar project. A great deal of the medical school expansion is centered on burgeoning research, particularly in molecular biology, largely financed by the National Institutes of Health. While the leaders of the NIH have long struggled with Congress to keep politics out of both the administration and the substance of research, it seems to old-timers that the politicians are slowly winning. Senator Specter's seniority on the Appropriations Committee may have had as much to do with the prosperity of West Philadelphia, as the quality of research, however eminent. We are about to find out, and if things go hard with us in favor of say Chicago, it could be a wrenching experience. Most of those research buildings cost more to heat, air-condition, insure and clean than the entire tuition base of the students; and they wouldn't be good for much if you tried to sell them.

The University is almost unique in being located on contiguous land, near existing public transportation, and occupying substantial old structures capable of renovation to new purposes. Mr. Hollenberg was asked whether it was cheaper to grow like this within a city, or whether it is cheaper to plant a totally new university in several open corn fields, as we often see happen. While this is a hard question to answer, and depends to some extent on the type of architect in charge, it is his view that big-city restoration is a considerably cheaper way to expand than building from scratch on open land, although if you are starting the institution itself from scratch, there isn't much choice but the cornfield.

And then, there is the ancient argument between academics and bricks and mortar. Development officers agree that it is easier to raise donations when you can name a building for the donor; grand visions for new frontiers of teaching are a much harder sell. So a question does hang over this expansion, however exciting, whether the endowment will keep up with the structures, once the excitement of physical expansion dies down. These are definitely things to worry about, but right now you seize the opportunities as they go past, leaving integration to your successors to figure out.

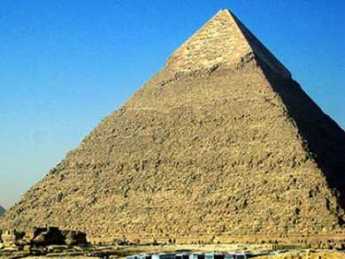

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Pyramid-Building, Greatly Simplified

|

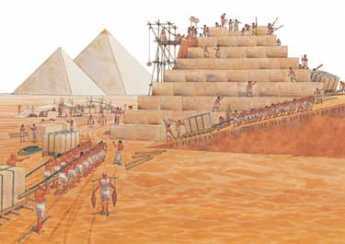

| Egyptian pyramids were supposed to be built |

Everyone who went to Sunday School knows the Egyptian pyramids were supposed to be built by huge numbers of slaves, quarrying stone blocks, transporting them with only crude rollers, and setting them precisely in place under the supervision of slave-drivers with whips. The number of stones has been estimated, a reasonable time estimate made for carving a block, and modern scholars have calculated that every single person in Eqypt must have been either a slave or a slave-driver. In fact, there is a theory among British scholars that such a mobilization of the entire nation could only have been motivated by religious fanaticism, since it's so hard to imagine keeping a nation at work involuntarily in the hot sun for twenty or more years, even with whips.

|

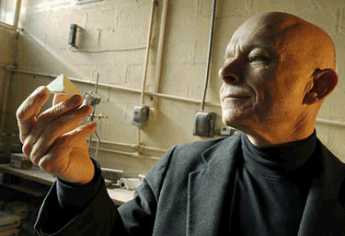

| Michael Barsoum |

As recently described to the Right Angle Club by Professor Michael Barsoum of the Ceramics Department of Drexel University, we probably have to revise our views. A "Eureka" moment seems to have first arrived for a French Professor named Joseph Davidovits several years ago, with the thought that perhaps the building blocks of the pyramids may have been cast in place rather than carved. Poured concrete, so to speak, rather than carved out of a quarry and pushed over the desert in some fashion and hauled up into place. Since the blocks seem precisely chiseled to fit together exactly, it has always been hard to imagine how this was done, when the Egyptians were thought to have no iron tools, only pure copper as a metal ingredient, not even bronze.

|

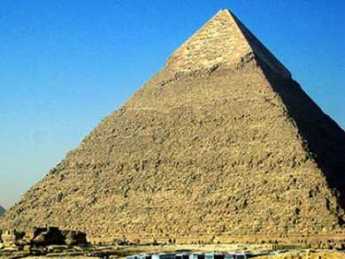

| Khufu Pyramid |

The insight was brilliant, although the evidence for it was weak, and it has been pretty easy to pick holes in the proposal. Poured concrete is much easier to reconcile with the remarkable leveling of the stone blocks, where the bottom level of the Khufu pyramid is the size of eight football fields but only varies from true level by one inch overall. Exploratory cuts into the sides of the pyramids reveal the component stones to vary enormously in size and shape in the interior, although the exterior surface is quite smooth. Similarly, the lateral sides of the pyramids vary from true north by only 1/15 of a degree, a remarkable achievement for stone cutting with primitive tools. Broad Street in Philadelphia supposedly runs North and South, for example, but it deviates from true north by six degrees. The pyramid builders, like the architects of ancient Beijing, must have used the Pole Star for orientation, rather than a magnetic compass.

|

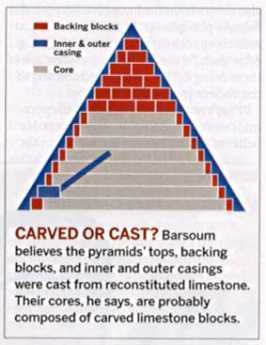

| Carved or Cast |

While Davidovits got this line of thinking started, Michael Barsoum has considerably advanced the proof of idea by addressing a large number of nitty-gritty questions about just how all this might have been accomplished. For example, the science of ceramics shifted the idea from the Portland Cement model to a recognition that the calcium in the cement came probably from diatomaceous earth, which is to say the crushed skeletons of diatoms on the ocean floor. Microscopic examination of the cement reveals large numbers of intact diatoms, with the cement layer surrounding the limestone aggregates. Furthermore, analysis of the stones shows that the outer shell of the pyramid was cast concrete, but the interior main mass was composed of stone rubble of various sizes and shapes. The apex of the pyramid was pure casting, probably because of the difficulty of fitting exterior and interior stones at the point. So, the Drexel team carried Davidiovits' idea from a general concept to a practical description of how the construction was probably accomplished. Carbon dating was attempted, but this technique stops being accurate for such remote time periods.

To nail down the idea that Philadelphia really explained how to build pyramids, funds are being collected for the construction of a 27-foot model pyramid in Logan Square. Let's hope the community gets behind this effort, which is both scholarly and entertaining, with an element of international competition mixed in. After all, Philadelphia is still smarting from the erection of the Eiffel Tower, six feet higher than Philadelphia City Hall, as the tallest structure in the world at that time. Let's be clear about it: the Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure in the world, while our City Hall remained the tallest building.

What's Different About Kosher ?

|

| Kosher Foods |

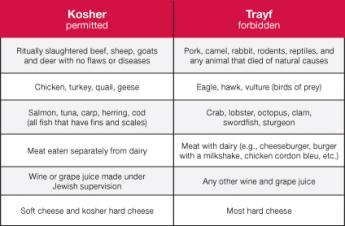

About half of the labeled food products in a typical supermarket are designated Kosher, displaying a "K". That seems remarkable when only about 1 million American Jews are observant or Orthodox, thus eating only Kosher food for religious reasons. So, the Chemical Heritage Foundation recently decided it would be interesting to examine the definition and details of the Kosher designation, which presumably has some chemical basis. The CHF was right about the interest in the topic; attendance at the auditorium was packed. The following is entirely derived from what was discussed there.

|

| Rabbi |