Related Topics

Science

Science

Natural Science

foo

Pictures in the Library

On the walls of the Reading Room of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia are 38 portraits of the most famous scientists of 19th Century America. Here are three of them.

Wister-Wistar

Wistar-Wister

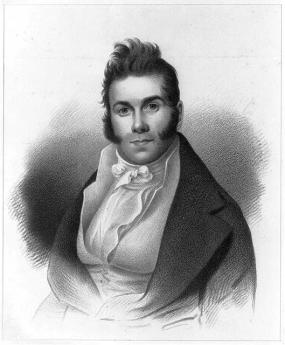

Thomas Say

|

| Thomas Say |

When writing to a good friend and fellow naturalist about his exploits in American Conchology, the Philadelphia Entomologist Thomas Say assured his friend that "INSECTS are the great objects of my attention. I hope to be able to renounce everything else and attend to them only." And so he did, writing one of the most important books on the study of North American insects. Say's American Entomology transformed the study of American Natural History from the pastime of science-oriented gentlemen, into a legitimate scientific field.

Thomas Say was born on June 27th, 1787 into a respectable Quaker family, the same summer when men from the newly independent states were meeting for the Constitutional Convention. His father, Benjamin Say, a "fighting Quaker" during the revolutionary war, was a well-established pharmacist and apothecary. His mother was a descendant of the famous naturalist, John Bartram of Bartram Gardens in Kingessing. Say seems to have inherited the naturalist gene, and collected butterflies for his great uncle, William Bartram, as a young boy. Into adulthood, he remained uninterested in all subjects save Natural History.

Say's father, skeptical about his son's obsessive interest in bugs, attempted to set him up in the pharmacy business as a partner with a family friend and fellow naturalist, John Speakman. Unfortunately, both men were more interested in Natural History than business; their partnership failed miserably, leaving Say completely broke but with plenty of time to devote to his passion, Natural History.

This passion contributed to the founding of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Meeting in the houses of local naturalists, and even in Say and Speakman's chemist shop, a small group of young men set out to create an institution where they could collect, share and legitimate the study of Natural History. With Say present at the founding meetings, the Academy of Natural Sciences was established to stop the exportation of scientific research to Europe and establish an American scientific community. Patriotic fervor was particularly notable during the year of the Academy's founding, 1812.

The Academy's progress took a brief hiatus that summer to put a stop to what the new Americans viewed as threats to the young country's independence. Say joined the army and survived its bullets. By the end of the war, and with American economic independence intact, the Naturalists now continued their mission of establishing American intellectual independence. Elected the Conservator of the Academy, Say devoted his life to the maintenance and study of its collections. He is said to have lived in the rooms of the Academy on bread and milk (with an occasional chop or egg) and to have slept under the skeleton of a horse. Notoriously frugal, spending only 6 cents on food every day, Say bemoaned the hassle and expense of dining. He would rather be studying the wings of mosquitoes than wasting time with fancy dining.

During these early days of the United States, Thomas Say was quickly cast as a key member of America's varied and extensive expeditions to discover its largely unknown country. His first was a trip with fellow Academy members to Florida in 1817, a journey cut short by the threat of unfriendly local indigenous tribes. The group did manage to capture a few important species; Thomas Say wrote to a friend that Florida while "not flowing with milk and honey," was "abounding in insects which are unknown."

In 1819, Say was appointed head zoologist for the expedition of Major Long to the Rocky Mountains, where Say discovered and named not only insects, but animals as well, including the Columba fasciata Say, or fan-tailed pigeon. Several years later, in 1823, Say accompanied Long once again, this time on an expedition to the head of the St. Peter's River.

Back in Philadelphia, Thomas Say worked tirelessly to deepen the Academy's intellectual work, publishing many articles for the Academy's Journal on both entomology and conchology. He was also involved with the American Philosophical Society and became professor of Natural Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. During this busy time, Say also managed to socialize among Philadelphia's upper crust, and is noted as having attended Caspar Wistar's weekly "soirees."

.jpg)

|

| Papilio Glacus from American Entymology |

His urban life did not last, however; Say found himself swept westward in a great tide of social idealism. Robert Owen, a Scottish social reformer, moved to the United States in hopes of establishing a community based on the principles of cooperation, brotherly love, and universal education through the absence of competition, and religious motives. Having purchased the property of the German "Harmonists" in Indiana, Owen persuaded nearly 1,000 people of varying background to help establish a Utopian society. Although Say had a strong democratic spirit, he was perhaps most interested in the move West for what it might offer him in the way of scientific discovery.

In 1826, with both MacClure and Owen, Thomas Say sailed down the Ohio River on what was called the "Boatload of Knowledge," a small ship carrying East Coast intellectuals to their Indiana paradise. Say was put in charge of the operation and named captain of the ship, perhaps due to his experience in the army more than a decade before. It was also on this boat ride to Indiana that Say met his future wife, Lucy Way Sistare, a prospective schoolteacher at New Harmony.

Despite this drastic move, Say remained much more concerned with his study of Natural History than any particular ideological movement, a fortunate enough attitude given the community's short life; after only two years the New Harmony project evaporated because of lack of organization and internal feuds between Owen and his various followers. Say was nevertheless able to use the move out West to his advantage and took part on an expedition to Mexico with William MacClure.

Although voices from the East Coast, and particularly the Academy, called him back, Say stayed in Indiana, publishing his two most famous works, American Entomology and American Conchology. He used illustrations composed over the years by young Titian Peale, son of Say's portraitist, Charles Wilson Peale, as well as Charles Alexandre Lesueur. Lucy Say, his wife, also helped to color the plates for their publication. These two works, and particularly American Entomology were praised abroad as real works of science and as proof the United States had "serious" scientists.

Say experienced relative peace and quiet during his final years in Indiana, a quiet spent in vigorous study of Natural History. However, after years of ill-health, of putting off food for study and his own well-being for that of others, Say died at the young age of 49 in 1834. He was buried at New Harmony, the grave marked with an epitaph capturing his unique passion for the Natural World:

Botany of nature, even from a child,

He saw her presence in the trackless wild;

To him the shell, the insect and the flower,

Were bright and cherished embers of her power.

In her, he saw a spirit life divine,

And worshiped like a Pilgrim at the shrine.

Originally published: Wednesday, November 24, 2010; most-recently modified: Friday, May 31, 2019

| Posted by: charlie thomas | Aug 27, 2018 6:13 PM |