2 Volumes

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Wistar Family

New volume 2017-05-11 14:57:17 description

Wister-Wistar

Wistar-Wister

Same family, two brothers with the same name. One brother changed his spelling.

Wistar Institute, Spelled With an "A"

|

| Dr. Russel Kaufman |

The Right Angle Club was recently honored by hosting a speech by Dr. Russel Kaufman, the CEO of the Wistar Institute. Dr. Russel is a charming person, accustomed to talking on Public Broadcasting. But Russel with one "L"? How come? Well, sez Dr. Kaufman, that was my idea. "When I was a child, I asked my parents whether the word was pronounced any differently with one or two "Ls", and the answer was, No. So if I lived to a ripe old age, just think how much time and effort would be wasted by using that second "L". In eighty years, I might spend a whole week putting useless "Ls" on the end of Russel. I pestered my parents about it to the point where they just gave up and let me change my name". That's the kind of guy he is.

|

| The Wistar Institute |

The Wistar Institute is surrounded by the University of Pennsylvania, but officially has nothing to do with it. It owns its own land and buildings, has its own trustees and endowment, and goes its own academic way. That isn't the way you hear it from numerous Penn people, but since it was so stated publicly by its CEO, that has to be taken as the last word. It's going to be an important fact pretty soon since the Wistar Institute is soon going to embark on a major fund-raising campaign, designed to increase the number of laboratories from thirty to fifty. The Wistar performs basic research in the scientific underpinnings of medical advances, often making discoveries which lead to medical advances, but usually not engaging in direct clinical research itself. This is a very appealing approach for the many drug manufacturers in the Philadelphia region, since there can be many squabbles and changes about patents and copyrights when the commercial applications make an appearance. All of that can be minimized when fundamental research and applied research are undertaken sequentially. Philadelphia ought to remember better than it does, that it once lost the whole computer industry when the computer inventors and the institutions which supported them got into a hopeless tangle over who had the rights to what. The results in that historic case visibly annoyed the judge about the way the patent infringement industry seemingly interfered with the manufacture of the greatest invention of the Twentieth century.

Patents are a tricky issue, particularly since the medical profession has traditionally been violently opposed to allowing physicians to patent their discoveries, and for that matter, Dr. Benjamin Franklin never patented any of his many famous inventions. But the University of Wisconsin set things in a new direction with the patenting of Vitamin D, leading to a major funding stream for additional University of Wisconsin research. Ways can indeed be devised to serve the various ethical issues involved since "grub-staking" is an ancient and honorable American tradition, one which has rescued other far rougher industries from debilitating quarrels over intellectual property. You can easily see why the Wistar Institute badly needs a charming leader like Russel, to mediate the forward progress of our most important local activity. From these efforts in the past have emerged the Rabies and Measles vaccines, and the fundamental progress which made the polio vaccine possible.

It was a great relief to have it explained that there is essentially no difference at all between Wisters with an "E" and Wistars with an "A". There were two brothers who got tired of the constant confusion between them, see and agreed to spell their names differently. When the Wistar Institute gathered a couple of hundred members of the family for a dinner, the grand dame of the family declared in a menacing way that there is no difference in how they are pronounced, either. It's Wister, folks, no matter how it is spelled. Since not a soul at the dinner dared to challenge her, that's the way it's always going to be.

The Wistars Think Big, But Talk Softly

|

| The Wistar Institute |

The Wistar Institute sits on the Penn campus, surrounded by Penn buildings. But it is entirely independent of Penn, dedicated to doing cutting-edge research which leads to practical applications later. They have fourteen new laboratories dedicated to fields most people know nothing about, and lots of old laboratories dedicated to the same. It's certainly something to have a scientific institute in our midst, especially one which refrains from blowing its own horn, and yet privately regards anything short of a Nobel Prize, as a failure.

|

| James Hayden |

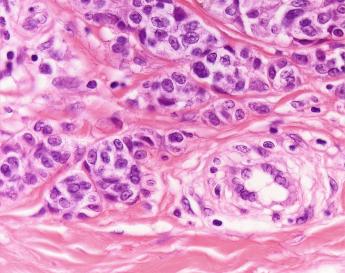

A recent speaker at the Right Angle Club was James Hayden, the Managing Director of Wistar's Imaging Facility. His specialty seems to be taking pictures through a microscope, which conform to the general principle that the closer the image is to the microscope, the shorter the focal distance must become. The consequence is that microscopic pictures are unable to see all the way through the entire slice at any one focal length wider than the cell itself. The advent of digital photography requires a full thickness slice, but only a portion of its depth is visible at any one time and must be stained. Gradually the impression emerges that full-depth digital photography requires a three-dimensional scale. If time is a fourth dimension, there are two more dimensions to round out the six dimensions which are photographed by a million-dollar microscope. And the resulting image, of which he showed many, stops resembling a pea in a pod with smooth edges and increasingly looks like a network of bushy strands with a nucleus buried deep within its depths.

|

| Melanoma Cell |

He described one extreme of this process as coming from boring a hole in the top of a mouse's skull, replacing the hole with a small window of glass, and showing a single melanoma cell metastasizing through the mouse's brain like a sheaf of wheat invading a cornfield. The heat it requires to keep the cell alive is often enough to damage the region, and all sorts of technical problems emerge from staining the cell part with pretty, but toxic, dyes. Having looked at a great many tissue slices after they were "fixed" (ie killed) by soaking in chemicals, I can tell you the old style looks nothing like the new one. It's going to take a long time and a lot of money to use this higher resolution, but you can tell at a glance that our thought processes about what cells are doing, will undergo some radical changes in the near future. And it will require a lot more expensive research to determine whether these new insights will be worth the money. Let's hope they are.

|

| Galileo's telescope |

Mr. Hayden promised to look into whether it might be possible to send an Internet link to a multi-dimensional picture of a cell in action, in which case members of the Right Angle club may be able to see this wonder in the original. Otherwise, it's sort of like Galileo's telescope, forcing the skeptic to take the inventor's word for it, as the only alternative to burning at the stake. In that particular historical case, the Pope was unable to decide which to do, so as I remember it he banished the guy.

Thomas Say

|

| Thomas Say |

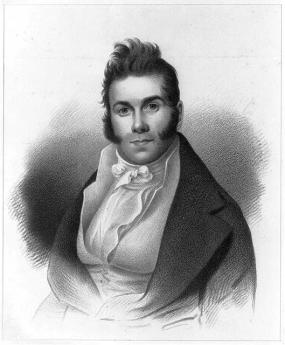

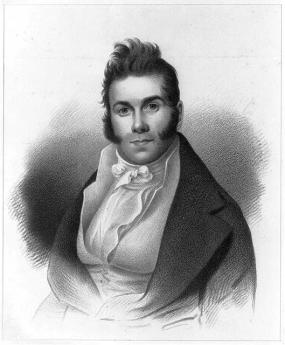

When writing to a good friend and fellow naturalist about his exploits in American Conchology, the Philadelphia Entomologist Thomas Say assured his friend that "INSECTS are the great objects of my attention. I hope to be able to renounce everything else and attend to them only." And so he did, writing one of the most important books on the study of North American insects. Say's American Entomology transformed the study of American Natural History from the pastime of science-oriented gentlemen, into a legitimate scientific field.

Thomas Say was born on June 27th, 1787 into a respectable Quaker family, the same summer when men from the newly independent states were meeting for the Constitutional Convention. His father, Benjamin Say, a "fighting Quaker" during the revolutionary war, was a well-established pharmacist and apothecary. His mother was a descendant of the famous naturalist, John Bartram of Bartram Gardens in Kingessing. Say seems to have inherited the naturalist gene, and collected butterflies for his great uncle, William Bartram, as a young boy. Into adulthood, he remained uninterested in all subjects save Natural History.

Say's father, skeptical about his son's obsessive interest in bugs, attempted to set him up in the pharmacy business as a partner with a family friend and fellow naturalist, John Speakman. Unfortunately, both men were more interested in Natural History than business; their partnership failed miserably, leaving Say completely broke but with plenty of time to devote to his passion, Natural History.

This passion contributed to the founding of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Meeting in the houses of local naturalists, and even in Say and Speakman's chemist shop, a small group of young men set out to create an institution where they could collect, share and legitimate the study of Natural History. With Say present at the founding meetings, the Academy of Natural Sciences was established to stop the exportation of scientific research to Europe and establish an American scientific community. Patriotic fervor was particularly notable during the year of the Academy's founding, 1812.

The Academy's progress took a brief hiatus that summer to put a stop to what the new Americans viewed as threats to the young country's independence. Say joined the army and survived its bullets. By the end of the war, and with American economic independence intact, the Naturalists now continued their mission of establishing American intellectual independence. Elected the Conservator of the Academy, Say devoted his life to the maintenance and study of its collections. He is said to have lived in the rooms of the Academy on bread and milk (with an occasional chop or egg) and to have slept under the skeleton of a horse. Notoriously frugal, spending only 6 cents on food every day, Say bemoaned the hassle and expense of dining. He would rather be studying the wings of mosquitoes than wasting time with fancy dining.

During these early days of the United States, Thomas Say was quickly cast as a key member of America's varied and extensive expeditions to discover its largely unknown country. His first was a trip with fellow Academy members to Florida in 1817, a journey cut short by the threat of unfriendly local indigenous tribes. The group did manage to capture a few important species; Thomas Say wrote to a friend that Florida while "not flowing with milk and honey," was "abounding in insects which are unknown."

In 1819, Say was appointed head zoologist for the expedition of Major Long to the Rocky Mountains, where Say discovered and named not only insects, but animals as well, including the Columba fasciata Say, or fan-tailed pigeon. Several years later, in 1823, Say accompanied Long once again, this time on an expedition to the head of the St. Peter's River.

Back in Philadelphia, Thomas Say worked tirelessly to deepen the Academy's intellectual work, publishing many articles for the Academy's Journal on both entomology and conchology. He was also involved with the American Philosophical Society and became professor of Natural Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. During this busy time, Say also managed to socialize among Philadelphia's upper crust, and is noted as having attended Caspar Wistar's weekly "soirees."

.jpg)

|

| Papilio Glacus from American Entymology |

His urban life did not last, however; Say found himself swept westward in a great tide of social idealism. Robert Owen, a Scottish social reformer, moved to the United States in hopes of establishing a community based on the principles of cooperation, brotherly love, and universal education through the absence of competition, and religious motives. Having purchased the property of the German "Harmonists" in Indiana, Owen persuaded nearly 1,000 people of varying background to help establish a Utopian society. Although Say had a strong democratic spirit, he was perhaps most interested in the move West for what it might offer him in the way of scientific discovery.

In 1826, with both MacClure and Owen, Thomas Say sailed down the Ohio River on what was called the "Boatload of Knowledge," a small ship carrying East Coast intellectuals to their Indiana paradise. Say was put in charge of the operation and named captain of the ship, perhaps due to his experience in the army more than a decade before. It was also on this boat ride to Indiana that Say met his future wife, Lucy Way Sistare, a prospective schoolteacher at New Harmony.

Despite this drastic move, Say remained much more concerned with his study of Natural History than any particular ideological movement, a fortunate enough attitude given the community's short life; after only two years the New Harmony project evaporated because of lack of organization and internal feuds between Owen and his various followers. Say was nevertheless able to use the move out West to his advantage and took part on an expedition to Mexico with William MacClure.

Although voices from the East Coast, and particularly the Academy, called him back, Say stayed in Indiana, publishing his two most famous works, American Entomology and American Conchology. He used illustrations composed over the years by young Titian Peale, son of Say's portraitist, Charles Wilson Peale, as well as Charles Alexandre Lesueur. Lucy Say, his wife, also helped to color the plates for their publication. These two works, and particularly American Entomology were praised abroad as real works of science and as proof the United States had "serious" scientists.

Say experienced relative peace and quiet during his final years in Indiana, a quiet spent in vigorous study of Natural History. However, after years of ill-health, of putting off food for study and his own well-being for that of others, Say died at the young age of 49 in 1834. He was buried at New Harmony, the grave marked with an epitaph capturing his unique passion for the Natural World:

Botany of nature, even from a child,

He saw her presence in the trackless wild;

To him the shell, the insect and the flower,

Were bright and cherished embers of her power.

In her, he saw a spirit life divine,

And worshiped like a Pilgrim at the shrine.

Pennsylvania Prison Society

|

| Duke of York |

William Penn, who spent considerable time in British prisons, established a penal code for his new colony which largely swept away the draconian punishments established by the code of the Duke of York. Until as late as 1780, jails were mainly confinement hotels for debtors, prisoners awaiting trial, and witnesses. For actual punishment, the methods were execution and flogging. Penn's Code for Pennsylvania restricted execution to the crime of murder, and flogging to sexual offenses; everything else was punished by fines and imprisonment. Hidden in this code, of course, was the need to invent and construct prisons to service the imprisonment. It would take over a century to address this need, and Philadelphia still has not completely caught up with the need for more prison cells. Without a prison system, the Penn code was impractical, and the colonial penal code retrogressed toward floggings, pillories, and hangings after Penn's death.

|

| Dr. Benjamin Rush |

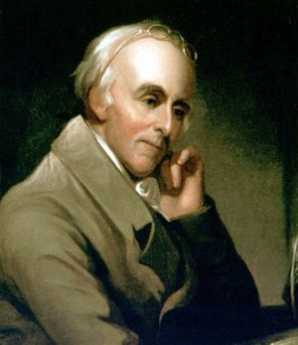

In colonial Philadelphia, the main prison was on Walnut Street, with sixteen cells. A neighboring Quaker, Richard Wistar, started a soup kitchen in his own home, taking the soup over to prisoners. By 1773, he had established the Pennsylvania Society for Assisting Distressed Prisoners, which was unfortunately disbanded by the occupying British Army in 1777. In 1783, Dr. Benjamin Rush with the assistance of Benjamin Franklin, Bishop White, and the Vaux family, founded the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, which after a century changed its name to the Pennsylvania Prison Society. The Prison Society believes it is the oldest continuous non-profit society in America.

|

| Eastern State Penitentiary |

The Prison Society has had several major changes in direction. The original concept was to substitute public labor for imprisonment, a less costly arrangement than imprisonment while avoiding a return to floggings and dismemberment. However, the degrading sight of prisoners in chain gangs caused a public outcry, and the approach was abandoned. In the spirit of the French and American revolutions, loss of liberty was seen as the greatest punishment conceivable. Added to this was the Quaker concept of inspiring remorse through silent meditation, and the eventual outcome was the construction of the Eastern State Penitentiary on what was then called Cherry Hill. In 1823, it was ominous that Eastern State Penitentiary was the largest structure in America. Although the concept was widely admired and imitated, the prolix Charles Dickens took a violent dislike to the idea of never talking to anyone, and led a reversion away from penitentiaries back to simple prisons. In the days before Alzheimers and schizophrenia were well characterized, the spectacle of massive recidivism was added to the rumor that protracted solitude led to insanity.

|

| Catherine Wise |

From Catherine Wise the Communications Director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the Right Angle Club recently learned that the current evolution of the American penal system has led to a steady state, but a troubled one. There are 2.2 million inmates in American prisons today, more than any other nation including Russia and China. Of these, 75,000 are confined in Pennsylvania, 9,000 in Philadelphia. Recidivism is 67%, the cost is $31,000 per year per inmate, the majority of inmates have been involved with illicit drugs, a growing number are infected with HIV and Hepatitis C, mental illness runs around 20%. The cost of incarceration is growing faster than the cost of either education or healthcare for the community. Prison overcrowding is extremely serious, the programs for managing parole and integration back into society are weak and underfunded. Eighty percent of the inmates are non-white, most prisons are located in remote regions too far for easy visiting, medical care in prison would not seem at all acceptable in general society. The Prison Society has no difficulty finding projects which are urgently needed. Just for an example, take the peculiar prison statistics; it really seems improbable that only 9,000 of the 75,000 Pennsylvania prisoners are in Philadelphia. Then reflect, NIMBY, that no one wants a prison or its visitors near his home, except areas of rural poverty welcome the employment a prison brings. Reflect for a moment that "jails" are paid for by local county taxes and contain prisoners with less than two years to serve. "Prisons" are paid for with state taxes, and contain those sentenced to longer than two years. Finally, add the fact that nonvoting Philadelphia prisoners in rural prisons are counted by the census as residents of the rural area for the purpose of distributing legislative and congressional seats. The rural politicians love the system, the urban neighbors love to be rid of the prison environment, but the prisoner families can't visit the prisoner. Who cares? Who even notices?

During the first World War, Quaker interest in prison matters was greatly stimulated by the imprisonment of many Quaker conscientious objectors to the wartime draft; since that time prison conditions have again become a central interest of the religion. It's hard to prove but is confidently asserted, that violence and mistreatment of prisoners are appreciably less in Pennsylvania than the rest of the country, California for example. In any event, The Pennsylvania Prison Society is a particularly effective advocate for humane treatment because of credibility achieved over two centuries, with newspaper editors on its board, and sympathetic affiliations with the legislative judicial committees. It knows what it is talking about, as a result of over 5000 annual prison visitations, and it has served the prison administrative corps by performing volunteer work, accepting contracts for parole projects, arranging bus trips for prisoner families to remote prisons, and working for improved funding for prisons. At the moment, there are six highly imaginative bills before the Pennsylvania Legislature, devised and researched by this outside organization with credibility, and political clout. Although the Society takes an occasional contract for a project, it is itself entirely funded by outside contributions, and because of occasional adversarial situations, asks for no funds from the state. Even the contract funds have been questioned, and are only accepted when the working relationships fostered are more useful for the prisoner clients than any co-option which might result.

One final word about medical care in prison. It's not as good as medical care for non-prisoners, and unfortunately it probably never can be. The remote rural location of prisons makes it difficult to obtain physicians and nurses, regardless of wage levels. It's dangerous to be around prisoners, as any guard will tell you, and it's more dangerous to be in control of narcotics amidst a population of addicted convicts. Malingering is nearly universal, both to obtain desired drugs and to spend "easy time" in the infirmary. Many prison escapes are engineered around the necessarily weakened security of the medical system. The prison budgeting system has all the rigidity and weaknesses of any governmental medical system, and in this case, it's run far out of sight of the public. Even the bureaucrats in charge are victimized by other bureaucrats. The average duration of incarceration in Pennsylvania is longer than in most other states; the prisons have to keep mental patients because the mental hospitals have all been closed. Fifty years ago, when there was no place to put a non-criminal with tuberculosis, he was put in jail. The parole system is underfunded, there is not nearly enough community support to absorb ex-con. Behind all this is a shortage of prison facilities. The legislature has got itself into a position that if it moved more prisoners into the outside, more prisoners would just fill the vacancies, costs would go up, and things wouldn't look much better. Only after the backlogs have been absorbed, would there be much visible effect.

Fanny Kemble

|

| Fanny Kemble (Sully) |

Frances Anne Kemble, universally known as Fanny, was just about the most magnificent Philadelphia woman of the Nineteenth Century. She spent much of her time abroad and others claimed her, but she was ours. Coming from a famous English theater family, the niece of Mrs. Siddons and the daughter of the founder of Covent Gardens, she quickly rescued the failing family fortunes by becoming the most striking Shakespearean ingenue of the time. It took very little time for her to know Lord Byron, Thackeray, and various other luminaries of the literary and artistic world of Europe, along with Queen Victoria. One might as well say she knew everybody unless one made the point that everyone knew her.

|

| Pierce Butler |

On a theatrical grand tour of America she met and married the Philadelphian Pierce Butler, one of the richest bachelors in the nation, heir to huge estates in Georgia. She had plenty of other choices, including the most dashing and romantic devil of the century, Trelawny. That glamorous friend of Byron's had been the one to drag Percy Shelley's body from the ocean, and was surely the greatest heartthrob of the century. Toward the end of her life, Fanny demonstrated the range of her appeal by totally subjugating the intellectual novelist Henry James, who was 34 years younger than she was. Her portraits by Sully now hang in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and in the Rosenbach Museum. Although Sully was said to have glamorized her a bit, her movie star qualities are evident. But appearance alone could not have mesmerized Henry James, known in literary circles as The Master. She was evidently one of those powerfully self-assured personalities encountered from time to time, who dominates every conversation, fills every room she enters, inspiring admiration rather than jealousy. As a youth, she was enchanting, as a mature woman, magnificent. Henry James described her as having "an incomparable abundance of being."

But this was not just another Cleopatra. Fanny Kemble had two personal achievements of enduring note. Because of health limitations, she went beyond being a Shakespearean actress to inventing a style of a public reading of Shakespeare, taking all the parts herself. She and Dr. Samuel Johnson were the two successive forces transforming Shakespeare's reputation from the quaint playwright of the past into the permanent towering figure of the English language.

Her other achievement destroyed her private life. As the wife of the owner of a thousand slaves, she led the attack on slavery before the Civil War. During the War, her passionate defense of emancipation was the main factor in persuading the British Government to refuse badly needed loans to the Confederacy. However, the publication of her journals was the last straw in a tumultuous marriage, and Pierce Butler divorced her, taking custody of their daughters, exiling her to England. Southern plantation owners were always short of cash, and realistically one has to acknowledge the strain of demanding to emancipate a thousand slaves, each one worth a thousand dollars. In one of the supreme ironies of a tragic situation, the forced sale of the slaves compelled the Butlers to liquidate an asset just before it was going to be destroyed by wartime events. Butler died in 1863, but she had done him a financial favor.

Fanny's daughter married Dr. Caspar Wistar, of Grumblethorpe and the grounds of present LaSalle College. Her grandson was Owen Wister, the college roommate of Teddy Roosevelt, later the author of The Virginian. Famous for the phrase "If you say that to me, smile", Owen Wister and his roommate created the fable of the romantic cowboy which still dominates movies and fiction, and, from time to time, the Presidency of the United States.

5 Blogs

Wistar Institute, Spelled With an "A"

The Wistar Institute is properly pronounced "Wister", but in fact it's all the same family. Its fame in biomedical research makes that quite irrelevant.

The Wistar Institute is properly pronounced "Wister", but in fact it's all the same family. Its fame in biomedical research makes that quite irrelevant.

The Wistars Think Big, But Talk Softly

The closer the object is to the microscope, the shorter the focal length will be.

The closer the object is to the microscope, the shorter the focal length will be.

Thomas Say

Thomas Say's portrait hangs in the Ewell Sale Stewart Library at the Academy of Natural Sciences in remembrance of his love of bugs and passion for the Academy.

Thomas Say's portrait hangs in the Ewell Sale Stewart Library at the Academy of Natural Sciences in remembrance of his love of bugs and passion for the Academy.

Pennsylvania Prison Society

When the British monarchy put William Penn in jail, they set in motion a social movement which has changed prison management more than it changed Penn.

When the British monarchy put William Penn in jail, they set in motion a social movement which has changed prison management more than it changed Penn.

Fanny Kemble

Frances Anne Kemble had it all: fame, beauty, wealth, personal friendship with real royalty and literary royalty. Beyond that, she caused a major new understanding of Shakespeare and was a major force in the abolition of slavery. Philadelphia wasn't big enough to hold her; perhaps no town was.

Frances Anne Kemble had it all: fame, beauty, wealth, personal friendship with real royalty and literary royalty. Beyond that, she caused a major new understanding of Shakespeare and was a major force in the abolition of slavery. Philadelphia wasn't big enough to hold her; perhaps no town was.