0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Pictures in the Library

On the walls of the Reading Room of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia are 38 portraits of the most famous scientists of 19th Century America. Here are three of them.

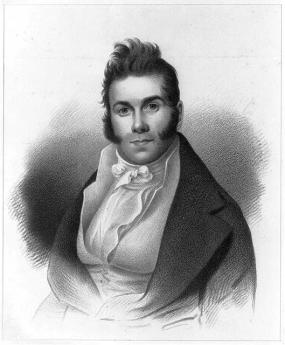

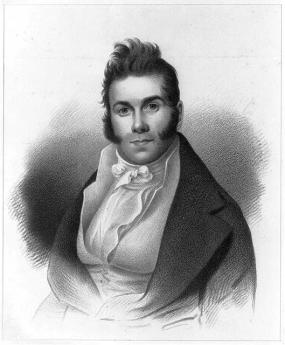

Thomas Say

|

| Thomas Say |

When writing to a good friend and fellow naturalist about his exploits in American Conchology, the Philadelphia Entomologist Thomas Say assured his friend that "INSECTS are the great objects of my attention. I hope to be able to renounce everything else and attend to them only." And so he did, writing one of the most important books on the study of North American insects. Say's American Entomology transformed the study of American Natural History from the pastime of science-oriented gentlemen, into a legitimate scientific field.

Thomas Say was born on June 27th, 1787 into a respectable Quaker family, the same summer when men from the newly independent states were meeting for the Constitutional Convention. His father, Benjamin Say, a "fighting Quaker" during the revolutionary war, was a well-established pharmacist and apothecary. His mother was a descendant of the famous naturalist, John Bartram of Bartram Gardens in Kingessing. Say seems to have inherited the naturalist gene, and collected butterflies for his great uncle, William Bartram, as a young boy. Into adulthood, he remained uninterested in all subjects save Natural History.

Say's father, skeptical about his son's obsessive interest in bugs, attempted to set him up in the pharmacy business as a partner with a family friend and fellow naturalist, John Speakman. Unfortunately, both men were more interested in Natural History than business; their partnership failed miserably, leaving Say completely broke but with plenty of time to devote to his passion, Natural History.

This passion contributed to the founding of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Meeting in the houses of local naturalists, and even in Say and Speakman's chemist shop, a small group of young men set out to create an institution where they could collect, share and legitimate the study of Natural History. With Say present at the founding meetings, the Academy of Natural Sciences was established to stop the exportation of scientific research to Europe and establish an American scientific community. Patriotic fervor was particularly notable during the year of the Academy's founding, 1812.

The Academy's progress took a brief hiatus that summer to put a stop to what the new Americans viewed as threats to the young country's independence. Say joined the army and survived its bullets. By the end of the war, and with American economic independence intact, the Naturalists now continued their mission of establishing American intellectual independence. Elected the Conservator of the Academy, Say devoted his life to the maintenance and study of its collections. He is said to have lived in the rooms of the Academy on bread and milk (with an occasional chop or egg) and to have slept under the skeleton of a horse. Notoriously frugal, spending only 6 cents on food every day, Say bemoaned the hassle and expense of dining. He would rather be studying the wings of mosquitoes than wasting time with fancy dining.

During these early days of the United States, Thomas Say was quickly cast as a key member of America's varied and extensive expeditions to discover its largely unknown country. His first was a trip with fellow Academy members to Florida in 1817, a journey cut short by the threat of unfriendly local indigenous tribes. The group did manage to capture a few important species; Thomas Say wrote to a friend that Florida while "not flowing with milk and honey," was "abounding in insects which are unknown."

In 1819, Say was appointed head zoologist for the expedition of Major Long to the Rocky Mountains, where Say discovered and named not only insects, but animals as well, including the Columba fasciata Say, or fan-tailed pigeon. Several years later, in 1823, Say accompanied Long once again, this time on an expedition to the head of the St. Peter's River.

Back in Philadelphia, Thomas Say worked tirelessly to deepen the Academy's intellectual work, publishing many articles for the Academy's Journal on both entomology and conchology. He was also involved with the American Philosophical Society and became professor of Natural Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. During this busy time, Say also managed to socialize among Philadelphia's upper crust, and is noted as having attended Caspar Wistar's weekly "soirees."

.jpg)

|

| Papilio Glacus from American Entymology |

His urban life did not last, however; Say found himself swept westward in a great tide of social idealism. Robert Owen, a Scottish social reformer, moved to the United States in hopes of establishing a community based on the principles of cooperation, brotherly love, and universal education through the absence of competition, and religious motives. Having purchased the property of the German "Harmonists" in Indiana, Owen persuaded nearly 1,000 people of varying background to help establish a Utopian society. Although Say had a strong democratic spirit, he was perhaps most interested in the move West for what it might offer him in the way of scientific discovery.

In 1826, with both MacClure and Owen, Thomas Say sailed down the Ohio River on what was called the "Boatload of Knowledge," a small ship carrying East Coast intellectuals to their Indiana paradise. Say was put in charge of the operation and named captain of the ship, perhaps due to his experience in the army more than a decade before. It was also on this boat ride to Indiana that Say met his future wife, Lucy Way Sistare, a prospective schoolteacher at New Harmony.

Despite this drastic move, Say remained much more concerned with his study of Natural History than any particular ideological movement, a fortunate enough attitude given the community's short life; after only two years the New Harmony project evaporated because of lack of organization and internal feuds between Owen and his various followers. Say was nevertheless able to use the move out West to his advantage and took part on an expedition to Mexico with William MacClure.

Although voices from the East Coast, and particularly the Academy, called him back, Say stayed in Indiana, publishing his two most famous works, American Entomology and American Conchology. He used illustrations composed over the years by young Titian Peale, son of Say's portraitist, Charles Wilson Peale, as well as Charles Alexandre Lesueur. Lucy Say, his wife, also helped to color the plates for their publication. These two works, and particularly American Entomology were praised abroad as real works of science and as proof the United States had "serious" scientists.

Say experienced relative peace and quiet during his final years in Indiana, a quiet spent in vigorous study of Natural History. However, after years of ill-health, of putting off food for study and his own well-being for that of others, Say died at the young age of 49 in 1834. He was buried at New Harmony, the grave marked with an epitaph capturing his unique passion for the Natural World:

Botany of nature, even from a child,

He saw her presence in the trackless wild;

To him the shell, the insect and the flower,

Were bright and cherished embers of her power.

In her, he saw a spirit life divine,

And worshiped like a Pilgrim at the shrine.

Elias Durand

|

| Elias Durand |

Philadelphia has a long and bumpy history with the French, more or less paralleling the British wars with them. But when the guillotine threatened aristocratic necks, Philadelphia offered a sanctuary of new world enthusiasm and sophistication. A few years after the terror, during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, Americans scorned his monomaniacal approach to government, returning to the British disdainful view of Frenchmen. In another era, Philadelphia would change its view, displaying a prominent collection of sculptures by the famous French artist, Rodin. And in today's political climate, of course, the French and their socialist leanings are akin to the devil incarnate. It can not be denied, however, the French had a major influence on Philadelphia society and culture. Elias Durand, a former member of the Academy of Natural Sciences whose portrait hangs in the Library Reading room, was a French refugee whose love of Botany greatly expanded American understanding and knowledge of plant life in North America. Somehow, that seems appropriate for an educated Frenchman. But his achievements in commerce were at least as important to his adopted city as his intellectual ones.

The youngest of fourteen children, Durand was born in Mayenne, France in 1794. A passionate chemistry student, he studied pharmaceuticals in school where he was also introduced to the subjects of natural history, mineralogy, geology, and entomology. His rich education in both Mayenne and Paris expanded his interest in chemistry to include the interplay between the hard sciences and the natural world. In 1812, after studying in Paris, Durand joined Napoleon's army, where he served as a medic and "Pharmacien," overseeing the opening of hospitals and the care of wounded soldiers. Even while serving in one of France's most historic wars, Durand remained passionate about the world of plants, by some accounts even collecting plants during the notoriously bloody Battle of Leipzig.

When Napoleon's luck turned bad, Durand focused his attention back to chemistry. In 1814 he left the army and moved to Nantes, where he worked briefly as an apothecary, as well as a lecturer on Medicinal plants in the regional Academy. Durand would remain a teacher throughout his life, instilling those around him with a fascination and passion for the Natural Sciences.

Always a patriotic Frenchman, however, Durand rejoined Napoleon's forces during the general's final hurrah, the "100 days." After Napoleon sustained his ultimate defeat at the battle of Waterloo, Durand retired from military duties and focused once again on the study of pharmaceuticals. His earlier connections to Napoleon, however, led to some uncomfortable clampdowns on the young man's freedom; Durand left the country in disgust in 1816 at being forced to report himself to the police every morning. He sailed to New York in pursuit of a life free from politics and dedicated to his passions of botany and chemistry.

Durand was quickly welcomed into the homes of other French ex-patriots living in Boston and soon met ambitious and science-oriented men who encouraged the young chemist to stay in the country. Hearing there might be work with Dr. Gerard Troost, the first president of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Durand traveled by foot to the mid-Atlantic region. This adventure brought him into contact with local Native Americans, whom he found friendly, as well as local native colonists, whom he found less so.

After a long and arduous journey down the East Coast, Durand finally arrived in Baltimore, only to learn that Troost was not in need of an employee. He was, however, desperate for a companion, and after spending several weeks in Troost's company, Durand left to find work in Baltimore with increased enthusiasm for Botany and in particular native species of North America.

In Baltimore, Durand found work with Mr. Ducatel as a pharmacist and apothecary. He quickly settled into the business, gaining experience in the field and eventually marrying Mr. Ducatel's daughter. But after five years in Baltimore, with both his wife and his father-in-law had passed away, Durand left Baltimore to search for new opportunities.

|

| Former Pharmacy at 6th and Chestnut |

He found them in Philadelphia. Perhaps because of the city's burgeoning field of Natural History or its emerging reputation as a medical town, Durand became committed to forging a career in Philadelphia. With the hope of opening a pharmacy in the finely decorated "European Style," Durand returned to France in 1825 to collect materials for this undertaking. Upon his arrival back to town, he set up a shop at 6th and Chestnut streets. His store quickly became world renown for its unique and finely produced medicinal pharmaceuticals, unique in its access to both old world and new world innovations.

Philadelphia proved to be a good move for the young Frenchman; in the next few years he married Marie Antoinette Berauld, a refugee from the St. Domingo Insurrection, and achieved election to the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.

After his wife died in 1851, Durand gave up business to pursue the study of Botany. He was elected to the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1852, and during his membership published numerous articles and books on the botanical findings of expeditions to the American West and the Arctic. Durand also contributed to the study of Botany through the publication of several biographies about the lives of botanists Thomas Nuttall and Andre Michaux, the famous arborist. Durand's deep and lifelong appreciation for the study of Botany helped bolster the Academy's resources during his membership.

As Durand grew older, his French roots called him back to the homeland; in 1860 he returned to France, and finding the collection of North American specimens lacking in the Jardin des Plantes de Paris, determined to expand the collection himself. He returned to Philadelphia and spent the remainder of his life developing his collection of North American specimens with the help of his son. Eight years later, in 1968, Durand shipped his collection of 10, 000 specie herbarium to Paris where it was arranged in a special gallery named after him, the Herbia Durand. Much of Durand's remaining collection, however, was left to the Academy after his death.

After this long, varied and successful career in the world of Natural Science, Elias Durand died in his home on 9th and Broad Streets (sic) in 1873 at the age of 80. He had contributed greatly to the fields of Botany and helped to establish Philadelphia's respected reputation in the world of medicine. Although a Frenchman at heart, Durand remains a feather in Philadelphia's cap and an important face at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Effingham Buckley Morris

|

| Effingham Buckley Morris |

The vibrant chatter of schoolchildren is familiar at the Academy of Natural Sciences; its museum is a standard stop for local school trips and family outings. Effingham Buckley Morris, the president of the Academy from 1928 until his death in 1937, is largely to thank for the museum's youthful spirit. A giant of the Philadelphia banking community, Morris used his success in business as well as his connections to other local institutions to advance the Academy's outreach. In 1936, after conducting a comprehensive survey of the Academy's work, Morris and his associates announced the Educational Development Program. One goal was to create a specific Education Department, dedicated to educating children from local private and public schools. As Morris put it on the day of the Program's public unveiling, "We want a museum where ideas are on display rather than things." The Academy has certainly succeeded over the years in fulfilling Morris' ambitions.

Morris had quite a knack for inspiring people and institutions to think big and move in new directions. He was often quoted as having a unique ability to "enlist the loyal co-operation of his colleagues," garnering followers and supporters wherever he went.

A member of the well-known Quaker "Morris" family of Philadelphia, Effingham Buckley came from a long tradition of civic engagement. Effingham was born in the old Morris mansion on Eighth Street, the son of Israel Wistar Morris and Annis Morris Buckley. During his boyhood, he attended the Classical Academy of Dr. John W. Faires and then enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania for undergrad. It was at Penn that he began his long and illustrious career as a "leader," founding the College Boat Club and becoming one of the first presidents of the University Athletic Association. His popularity and vibrant spirit only grew as he established himself as an adult in the Philadelphia community. Although Digby Baltzell was later to immortalize a tradition of disdain for the diffidence and lack of distinction of Quaker-dominated Philadelphia, he certainly seems to have overlooked Effy Morris.

|

| Old Morris Mansion |

After receiving his graduate degree in Law from Penn, Morris worked exclusively in that field for several years. During this period of American expansion and economic growth, Morris was heavily involved in the booming railroad business throughout Pennsylvania, helping to settle deals during its various organizational forms. Because of its many mergers and acquisitions, a successful railroad mainly embodies a successful lawyer. During the long period when railroads were at the heart of the Philadelphia economy, a majority of railroad presidents were lawyers.

Perhaps the crowning achievement of Morris' career, however, was his wildly successful Presidency at the Girard Trust Company. One of his first moves as President was to set the company's important presence in stone through the construction of the Pantheon-esque Girard Trust Company building on Chestnut and Broad streets. Attached to this building, and now home to the Ritz Carlton hotel is a tall, impressive skyscraper that is also part of Morris' legacy. This white skyscraper had many critics during the days of its construction in 1888, but it was to become the first "office" building of its kind. Although the Witherspoon building at 13th and Chestnut makes the same sort of claim, the two Girard structures across the street still dominate the heart of the city today.

|

| Girard Trust Building |

During his career, Morris managed to become involved with a host of financial institutions in Philadelphia; he was the director of the Philadelphia National Bank, the Fourth Street National Bank, the Commercial Trust Company and a manager of the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society. He also became the trustee of large estates, including those of Anthony J. Drexel, and William Bingham.

Aside from his financial involvement in Philadelphia society, Morris was also an active member in its cultural societies. The Colonial Society of American, the Historical Society, and the Union League are just a few clubs of which Effingham Morris was a member. Morris also became a dedicated patron of the sciences, joining the board of the Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology and in 1928, donating to the Institute 150 acres of historic Pennsylvania land in Bucks County for the study of biology.

|

| New Ritz Carleton Hotel |

Effingham became a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1896. He was later elected Chairman of the Finance Committee in 1905, then to the Board in 1925 where he was then elected president in 1928. Effingham approached his presidency with caution and modesty, aware of his limited knowledge in the scientific field and often enlisting the advice of his so-called "alter-ego," and the Academy's future president, Charles M. B. Cadwalader. Morris used his unique skills and local connections to help the Academy grow in new directions and expand its educational capacities.

Morris remained active until his death in 1937 and was, in no doubt, a dominant force in the development of Philadelphia and the improvement of its institutions. His portrait in the Academy's Library serves as a reminder of the Institution's deep and historical connections to the Philadelphia non-scientific community.

3 Blogs

Thomas Say

Thomas Say's portrait hangs in the Ewell Sale Stewart Library at the Academy of Natural Sciences in remembrance of his love of bugs and passion for the Academy.

Thomas Say's portrait hangs in the Ewell Sale Stewart Library at the Academy of Natural Sciences in remembrance of his love of bugs and passion for the Academy.

Elias Durand

After first fighting in the Napoleonic wars, a French ex-pat brought a European flare both to Pharmacy and the study of Botany in the United States.

After first fighting in the Napoleonic wars, a French ex-pat brought a European flare both to Pharmacy and the study of Botany in the United States.

Effingham Buckley Morris

Effingham Buckley Morris may not have thought of himself as a scientist but his love for Natural History brought the Academy of Natural Sciences much closer to the public and established the institution as an important component of Philadelphia. His banking career was a notable one.

Effingham Buckley Morris may not have thought of himself as a scientist but his love for Natural History brought the Academy of Natural Sciences much closer to the public and established the institution as an important component of Philadelphia. His banking career was a notable one.