Related Topics

Religious Philadelphia

William Penn wanted a colony with religious freedom. A considerable number, if not the majority, of American religious denominations were founded in this city. The main misconception about religious Philadelphia is that it is Quaker-dominated. But the broader misconception is that it is not Quaker-dominated.

Japan and Philadelphia

Philadelphia and Japan have had a special friendship for 150 years.

Quakers: The Society of Friends

According to an old Quaker joke, the Holy Trinity consists of the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Computers, Digital Cameras, and Cellphones

Much of the early development of the electronic computer took place in Philadelphia. We lost the lead, but it might return.

Philadelphia Economics

economics

Science

Science

Causes of the American Revolution

Britain and its colonies had outgrown Eighteenth Century techniques of governance. Unfortunately, both England and America lacked the sophistication to make drastic changes smoothly.

Philadelphia Changes the Nature of Money

Banking changed its fundamentals, on Third Street in Philadelphia, three different times.

Favorites - II

More favorites. Under construction.

Quaker Business

New topic 2016-12-04 04:11:17 description

Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution

|

| Richard Arkwright |

The Industrial Revolution had a lot to do with manufacturing cotton cloth by religious dissenters in the neighborhood of Manchester, England in the Eighteenth Century. What needs more emphasis is the remarkable fact that Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution both originated about the same time, in about the same place. True, the industrializing transformation can be seen in England as early as 1650 and as late as 1880. The Industrial Revolution thus extended before Quakerism was even founded, as well as long after most Quakers had migrated to America. No Quaker names are much mentioned except perhaps for Barclay and Lloyd in banking and insurance, and Cadbury in candy. As far as local history in England's industrial midlands is concerned, the name mentioned most is Richard Arkwright, whose behavior, demeanor and beliefs were anything but Quaker.

He seems to have invented nothing, stealing the patents and ideas of others freely, while disgustingly boasting about his rise from rags to riches. Some would say his skill was in the organization, others would say he imposed an industrial dictatorship on a reluctant agricultural community. He grew rich by coercing orphans, convicts and others he obviously disdained into long, unpleasant, boring and unwelcome labor that largely benefited him, not them. In the course of his strivings, he probably forced Communism to be invented. It is no accident that Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto while in Manchester visiting his friend Friedrich Engels, representing reasonably well the probable attitudes of Arkwright's employees. What Arkwright recognized and focused on was that enormous profits could flow from bringing piecework weaving into factories where machines could do most of the work. Until his time, clothing was mostly made by piecework at home, with middlemen bringing it all together. The trick was to make clothing cheaper by making a lot of it, and making a bigger profit from a lot of small profits. Since the main problem was that peasants intensely disliked indoor confinement around dangerous machines, the industrial revolution in the eyes of Arkwright and his ilk translated into devising ways to tame such semi-wild animals into submission. For their own good.

|

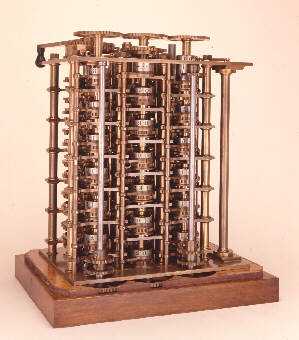

| Charles Babbage |

Distinctive among the numerous religious dissenters in the region, the Quakers taught that it was an enjoyable experience to sit indoors in quiet contemplation. Their children were taught to submit to it at an early age, and their elders frequently exclaimed that it was a blessing when everyone remained quiet, enjoying the silence. Out of the multitude of religious dissenters in the first half of the Seventeenth century, three main groups eventually emerged, the Quakers, the Presbyterians, and the Baptists. Only the Quakers taught that silence was productive and enjoyable; the Calvinist sects leaned toward the idea that sitting on hard English oak was good for the soul, training, and discipline was what kept 'em in line.

|

| babbagemaq.jpg |

The Quaker idea of fun through daydreaming was peculiarly suitable for the other important feature of the Industrial Revolution that Arkwright and his type were too money-centered to perceive. If workers in a factory were accustomed to sit for hours, thinking about their situation, someone among them was bound to imagine some small improvement to make life more bearable. If such a person was encouraged by example to stand up and announce his insight, eventually the better insights would be adopted for the benefit of all. Two centuries later, the Japanese would call this process one of continuous quality improvement from within the Virtuous Circle. In other cultures, academics now win professional esteem by discovering "win-win behavior", which displaces the zero-sum or win/lose route to success. The novel insight here was that it has become demonstrably possible to prosper without diminishing the prosperity of others. In addition, it was particularly fortunate that many Quaker inhabitants of the Manchester region happened to be watchmakers, or artisans of similar trades that easily evolved into the central facilitators of the new revolution -- becoming inventors, machine makers and engineers.

The power of this whole process was relentless, far from limited to cotton weaving. When Charles Babbage sufficiently contemplated the punched-cards carrying the simple instructions of the knitting machines, he made an intellectual leap to the underlying concept of the tabulating machine. Using what was later called IBM cards, he had the forerunner of the stored-program computer. There were plenty of Arkwrights getting rich in the meantime, and plenty of Marxists stirring up rebellion with the slogan that behind every great fortune is a great crime. But the quiet folk were steadily pushing ahead, relentlessly refining the industrial process through a belief in welcoming the suggestions of everyone.

Originally published: Tuesday, June 19, 2007; most-recently modified: Monday, June 03, 2019

| Posted by: How to get free followers | Feb 13, 2012 10:00 AM |

| Posted by: cheapostay discount | Feb 13, 2012 9:38 AM |

| Posted by: esalerugs promo code | Feb 13, 2012 9:16 AM |

| Posted by: Nelle | Jan 3, 2012 8:32 AM |

| Posted by: Steve_W | Dec 4, 2008 2:40 AM |