1 Volumes

Favorites - II

More favorites. Under construction.

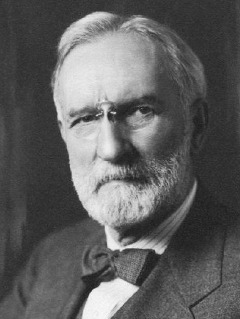

The Virginian: A Philadelphian Goes West

|

| Owen Wister |

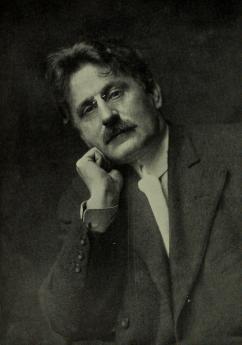

Where is the Philadelphia gentleman? According to Owen Wister, that wealthy Philadelphia novelist of the late 19th century, a true gentleman is found on the frontier. He rides horses, brands cattle. He is a cowboy. Wister is credited with creating this great American archetype, now so familiar from hundreds of movies, in his novel, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains. Published in 1902, the novel documents the experience of a sensitive young Philadelphian traveling through the still unformed West, where he meets the American nobleman. Wister originally intended this book to be the first of a series of four charactrizations of the types of Americans. A second, about Baltimore, was published, but after that, the fame of his brilliant first novel swept his career in other directions. He seems to have originally intended to describe Virginians more than cowboys, but it's hard to know where his original intention would have carried him.

|

| The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains |

Here is nevertheless a true classic. Using charmingly archaic language, Wister paints a landscape of sky and wild forests. His narrator speaks to the reader with the kind of verbal affection that only flourished in 19th-century literature. With an air of respect and modesty, the narrator introduces the reader to the novel's hero, the "Virginian." A transplant from the American south, this young man is a true Cowboy, a "daydream of glory made flesh" as Wallace Stegner once wrote. Early in the book, he stamps the hero with the line that made it all famous: "When you call me that, smile."

A host of colorful characters swirl around the Virginian as he aspires to social credibility and respect in the West. Western society, as understood through the Virginian's challenges and successes, is run by its own rules and social norms, norms that are heavily based on a largely male code of honor and decency. We learn about the code of the West as our Virginian learns it.

But the West is not only a myth of the American man; Molly Wood, another Easterner adrift in the wilderness, serves as a passionate, complicated love interest for the Virginian. Their relationship serves to contrast the social regulations of the East with the wilderness and abandon of the West. Wister's search for an American gentleman reminds us what it means to go West in search of something pure and new. What he found in the West has resonated throughout American culture for generations.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890 | Amazon |

How to Live Off an Investment Portfolio

Many studies have been done. The rule is this ...

If you have a well-diversified investment portfolio, and

- You want to live off the proceeds

- ... for a long time (20+ years)

You must withdraw no more than 4% per year.

- If your expenses are greater than 4% of your portfolio

- Reduce your expenses

and/or - Find outside sources of income

- Reduce your expenses

- If your investment portfolio is not well diversified it

will not last as long

(in other words, don't try to beat the market) - If your investment portfolio has high fees it will not last as long

| Sample Diversified Portfolio | |

| Asset Class | Symbol |

|---|---|

| US Total Market | VTI |

| Europe Developed | VGK |

| Asia Developed | VPL |

| Emerging Markets | VWO |

| US REITs | VNQ |

| Commodities | DJP |

| US Gov't Long | TLT |

| TIPS | TIP |

Plus a money market for cash

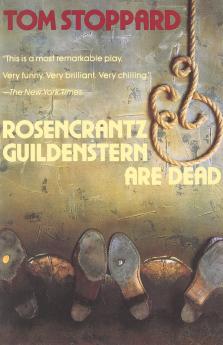

Rosencrantz and Gildenstern (4)

|

| Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead |

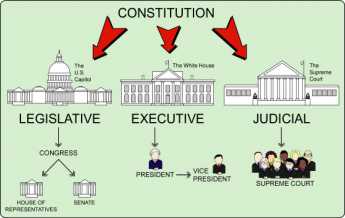

A few Broadway seasons ago, Tom Stoppard's play and movie Rosencrantz and Guildenstern have Dead described an experience, resonating with the early years of the Reagan presidential administration. If you are a small witness to palace politics, you mostly have no clue about what is actually happening. At that time, it was widely accepted among Washington gossips that the appointees who filled the Executive Office Building belonged to three hostile tribes in temporary alliance, and the Libertarian tribe was cast out. According to this recounting, the other two tribes were the Religious Right and the Win-at-any-cost California political professionals. A more mature view of it might be that all administrations of all parties contain hard-noses who make a profession of the ruthless winning of elections. An ideological president can't win without hard-ball lieutenants, so although their presence is inevitable, what matters is how well they are controlled.

|

| David Stockman |

Ignoring these unattractive fixtures of political machinery, David Stockman seemed to symbolize a libertarian economic ideology within the Reagan White House, and Caspar Weinberger a militaristic one. When Stockman was sacrificed to power realities in Congress, the Libertarians followed the lead of William Niskanen and bitterly retreated to the neighborhood think tanks. But a few years later, Weinberger was similarly sacrificed over the Star Wars and Iran-Contra matters. These functionaries working at EOB thought they ran the country, but that most affable of men, Ronald Reagan, ran things. He seriously meant to discredit New Deal economics and to win the Cold War. To do so, he willingly sacrificed small improvements in our economic system like the Medical Savings Account, and minor enhancements of military hardware like the Strategic Defense Initiative. He would like to see these things succeed, but they would have to do it on their own, without cost to his political capital.

And so, in time, John McClaughry went back to Vermont, founded a think tank called the Ethan Allen Institute, ran unsuccessfully for governor against Howard Dean, and became Majority Leader in the Vermont Senate. Meanwhile, I devoted my efforts to selling the Medical Savings Account concept to that most reserved of audiences, the American Medical Association.

Robert Barclay Justifies Quaker Meetings

|

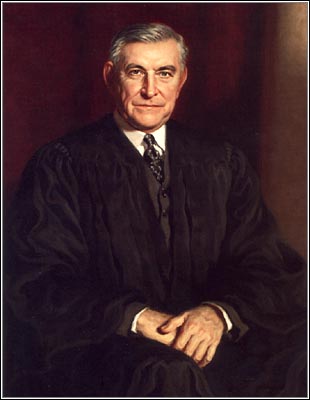

| Robert Barclay |

As part of the dissidence and Civil War of 17th Century England, Robert Barclay the Scotsman emerged with a point of view which was structured and reasoned in detail. What was almost unique was his reduction of it to a handful of pithy "Sound Bites". Coupled with membership in a prominent family, these abilities made him a particular friend of James, Duke of York, later King. Barclay became a Quaker at an early age.

The whole point of the Reformation was revulsion against the corrupt Catholic clergy, shielded behind some impossibly convoluted legalisms of doctrine. But for the governing establishment, any reform was going too far if it led to anarchy and chaos; combating disorder was then in many ways the central mission of the Catholic faith. The establishment did recognize that public revolt against universal micromanagement led to the scaffold for Kings who insisted on it. But in their view, the need for law and order still demanded some legitimacy, if not organized law. The Rangers, who paraded about stark naked and lived in ways resembling the hippies of the 1960s, were beyond the pale. Quakers, who professed no formal doctrine except silent meditation, might be possible just as threatening. After all, silent meditation could lead you anywhere including regicide. But the Quakers at least were quiet about it.

George Fox the founder of Quakerism had already provided one basis for containing fears of anarchy, by organizing local monthly meetings for worship within regional quarterly meetings; quarterly meetings, in turn, were within an overall framework of a yearly meeting. Occasional monthly meetings might develop a consensus for wild and antisocial behavior, indeed often did so, but would have to persuade the quarterly meetings whose members naturally outnumbered them. In extreme cases, the whole religion assembled in a yearly meeting. The innate conservatism of the meek would usually silence the extremism of the rebellious few. Very few kings would deny they could go no further toward despotism themselves, without the public behind them. The Quaker problem was to demonstrate what their consensus really was.

|

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

Essentially, the answer emerged that any religion which renounced a priesthood, which even renounced having a written doctrine, still needed some sort of institutional memory. If every Quaker began with a clean slate, to develop his own organized set of moral principles, then most of them would never get very far. Even if they did, they would have no time left for milking cows and weaving cloth. Single silent meditation was inefficient, particularly if you had faith that everyone was eventually going to arrive at the same convictions as the Sermon on the Mount. The founders of Quakerism took a chance, here. To assume the same outcome, you have to assume everyone starts with the same instincts and talents; even 21st Century America has private doubts about that one. Feudal England would have rejected it contemptuously. Carried to an extreme, it was a claim that everyone was as good a philosopher as Jesus of Nazareth, as good a person, as much a Son of God. That seemed like an arrogant claim. A more humble claim was that collectively, listening respectfully to one another in a gathered meeting, the whole world would over time reach the same truths as the Creator. If not, that still was as about as close as you were going to get to an oral memory, slowly building on the insights of the past.

Like all the early Quakers, Robert Barclay spent some time in jail. He did visit America in 1681, but it is doubtful if he spent any time here while he was Governor of East Jersey, from 1682 to 1688. The King insisted on his appointment, because he seemed the most reasonable man among the most reasonable sect of dissenters, and therefore the rebel he chose to deal with.

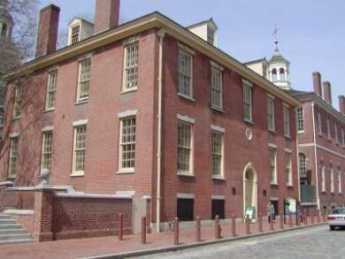

Rise and Fall of Books

| ||

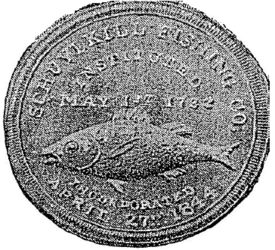

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

John C. Van Horne, the current director of the Library Company of Philadelphia recently told the Right Angle Club of the history of his institution. It was an interesting description of an important evolution from Ben Franklin's original idea to what it is today: a non-circulating research library, with a focus on 18th and 19th Century books, particularly those dealing with the founding of the nation, and, African American studies. Some of Mr. Van Horne's most interesting remarks were incidental to a rather offhand analysis of the rise and decline of books. One suspects he has been thinking about this topic so long it creeps into almost anything else he says.

|

| Join or Die snake |

Franklin devised the idea of having fifty of his friends subscribe a pool of money to purchase, originally, 375 books which they shared. The members were mainly artisans and the books were heavily concentrated in practical matters of use in their trades. In time, annual contributions were solicited for new acquisitions, and the public was invited to share the library. At present, a membership costs $200, and annual dues are $50. Somewhere along the line, someone took the famous cartoon of the snake cut into 13 pieces, and applied its motto to membership solicitations: "Join or die." For sixteen years, the Library Company was the Library of Congress, but it was also a museum of odd artifacts donated by the townsfolk, as well as the workplace where Franklin conducted his famous experiments on electricity. Moving between the second floor of Carpenters Hall to its own building on 5th Street, it next made an unfortunate move to South Broad Street after James and Phoebe Rush donated the Ridgeway Library. That building was particularly handsome, but bad guesses as to the future demographics of South Philadelphia left it stranded until modified operations finally moved to the present location on Locust Street west of 13th. More recently, it also acquired the old Cassatt mansion next door, using it to house visiting scholars in residence, and sharing some activities with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on its eastern side.

|

| Old Pictures of the Library Company of Philadelphia |

The notion of the Library Company as the oldest library in the country tends to generate reflections about the rise of libraries, of books, and publications in general. Prior to 1800, only a scattering of pamphlets and books were printed in America or in the world for that matter, compared with the huge flowering of books, libraries, and authorship which were to characterize the 19th Century. Education and literacy spread, encouraged by the Industrial Revolution applying its transformative power to the industry of publishing. All of this lasted about a hundred fifty years, and we now can see publishing in severe decline with an uncertain future. It's true that millions of books are still printed, and hundreds of thousands of authors are making some sort of living. But profitability is sharply declining, and competitive media are flourishing. Books will persist for quite a while, but it is obvious that unknowable upheavals are going to come. The future role of libraries is particularly questionable.

Rather than speculate about the internet and electronic media, it may be helpful to regard industries as having a normal life span which cannot be indefinitely extended by rescue efforts. No purpose would be served by hastening the decline of publishing, but things may work out better if we ask ourselves how we should best predict and accommodate its impending creative transformation.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1470.htm

Revolt of the Admirals: The Fight for Naval Aviation, 1945-1950

The National Security Act of 1947, intended to unify the separate armed forces services under a single Defense Secretary, failed to settle the deeper issue that divided them: the debate over roles and missions. One symptom of this conflict was a showdown between the Air Force and the Navy over the role of carrier aviation in the national security framework of the United States. From the early days of aviation, Army and Navy aviators had approached their roles very differently. Army air doctrine centered on strategic bombing, while Navy doctrine focused on carrier air power as an increasingly important element of the fleet's offensive striking power. In the postwar era of demobilization, these differences were exacerbated as each service fought for its share of a decreasing defense budget. Louis A. Johnson's appointment as Secretary of Defense in late March 1949 added to the Air Force-Navy friction. While Johnson allowed procurement of B-36s for the Air Force strategic bombing program to be greatly accelerated, he canceled development of the first flush-deck supercarrier, which would have enabled the Navy to operate long-range attack aircraft capable of carrying atomic weapons. This rejection fueled the Navy's fear that naval aviation was to have a diminishing role in the new atomic age and provided the final impetus for a clash between the Air Force and the Navy. The conflict came to a head when an anonymous document was delivered to members of Congress in May 1949, alleging improprieties in the Air Force procurement of the B-36 bomber. Although later found the be baseless, these charges inspired two sets of congressional hearings: the first on the B-36 bomber program itself, and the second on the issue on unification a strategy. During the latter hearings, high-ranking naval officers voiced their opinion that naval aviation was being denigrated by a Defense Secretary enamored with possibilities of strategic bombing and scornful of the Navy's contribution to such a mission. The press soon termed their vehement testimony in support of naval aviation the "revolt of the admirals."

About the Author

Jeffery G. Barlow has worked as a historian with the Contemporary History Branch of the Naval Historical center since 1987. He is writing an official two-volume history on the U.S. Navy and national security affairs. During 1969-1970, while on active duty with the U.S. Army, he served as a staff member of the newly established U.S. Army Military History Research Collection at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. A Navy junior, Dr, Barlow graduated with a B.A. in history from Westminster College (Pa.) in 1972. At the University of South Carolina, where he was an H.B. Earhart Fellow, he studied under Dr. Richard L. Walker and received a doctorate degree in international studies in 1981. Dr. Barlow's contributions to published works include a biographical chapter on Admiral Richard L. Conolly in Stephen Howarth's Men of War: Great Naval Leaders of World War Two (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993) and chapters on Allied and Axis naval strategies during the Second World War in Colin S. Gray and Roger W. Barnett's Seapower and Strategy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1989). His work has also appeared in International Security and Air University Review.

Purchase a copy here

Restoring the Gold Standard by Levering Judges' Salaries

|

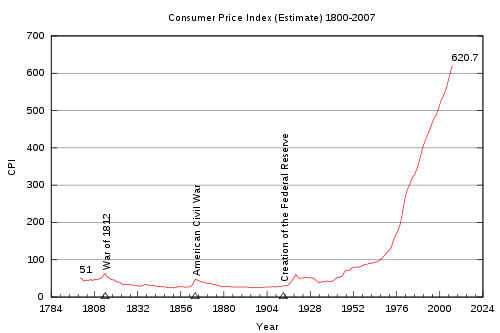

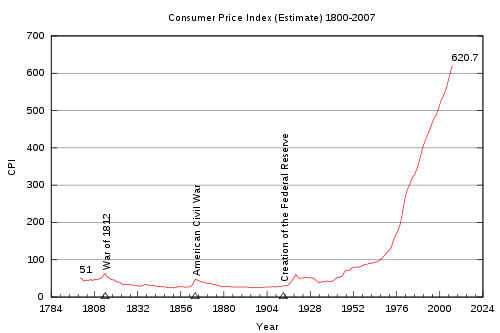

| Gold Inflation |

Generally speaking, creditors hate inflation and favor a gold standard because they fear debtors -- who outnumber them at the polls -- will dishonor their debts by inflating the currency. And debtors generally are rather serene about the risk of inflation, for the same reason in reverse. Since governments are almost invariably debtors, the combination of government and debtors on the side of promoting inflation represents a dishearteningly strong force for creditors to combat. It is plain for everyone to see that inflation has been steadily moving ahead. But it is something for everyone to ponder that leaving creditors with only one recourse is almost certain to translate that particular recourse into action. Creditors will raise interest rates in anticipation of inflation, and the economy will suffer for debtors as well as everyone else.

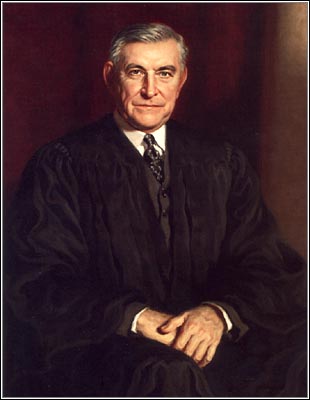

So, hard-money advocates like the Paul family of Texas have been rather nonplussed to discover that Federal Judges have handed them in 2010 a very effective weapon they had long overlooked. It should be no surprise that it came from that direction; judges are long accustomed to looking backward to the historical origins of the laws they are charged with interpreting. In this case, the defining statement is found in the Declaration of Independence.

Parenthetically, conservatives are reluctant to include the Declaration in an explanation of the Constitution, since it is plainly true the Constitution was written to correct the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was much more closely defined by the circumstances of the Declaration. The almost immediate response to any such logical jump over the Constitution, particularly those of Abraham Lincoln, is to thump the maxim that The Declaration of Independence is not Law. And it isn't; it's just in this case it makes a concise statement of a major reason we were offended by the King of England:

"He has made judges dependent on his will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries."

Note the operative phrase dependent on his will alone , which takes us back to the Magna Carta, where even the King must obey the Law. If judges are the umpires, it isn't in accord with deeply felt British culture that the King could force the umpires to favor his wishes in their official decisions, by threatening punishment on their persons. No, thousand times no. Anyone can see that.

Furthermore, the determination of underlying intent is so difficult to prove, and so easy to deny, that it is scarcely mentioned in the debate. If two motives seem possible, the other party will assert the high-sounding one and deny the ulterior one. The offended party will instinctively suspect the reverse and will brush aside any protestations to the contrary. Since that is bound to happen, please skip the preliminaries and get on with the evidence. So it is in this case; any reduction in the judge's salary is treated as an attempt to influence official decisions. The Administration maintains a reduction of Federal judge salaries is necessary for budgetary reasons. Please don't insult my intelligence that way. You aren't allowed to reduce the salaries of judges for any reason.

From this rather easy position to take, it is only a short step to say that refusing to raise judge salaries during inflation is a reduction of salary in real terms, after adjusting for inflation. Your paper money is phony; I want to preserve my purchasing power. Your refusal to adjust for inflation is even more clearly a salary reduction since the link to gold was severed during the Nixon and Johnson administrations. We are not on anything remotely resembling a gold standard; we are on a monetary standard which is by law adjusted to inflation, and just about nothing else. Hubert Humphrey may have thought he was creating a loophole by mandating concern with unemployment, but just try to convince the judges of the Supreme Court of that one.

And so, it seems predictable that Judge Beer of the Eastern District of Louisiana, and his fellow judges, will achieve an effective gold standard for Federal Judges if they have the fortitude to tough it out. After that, it gets harder, Congressman Paul. You have to push the concept that what is fair for Federal Judges is fair for everyone else. You should assume that judges will vote in their own favor, and therefore reasonably assume that the public will vote in its own favor, too. If that be treason, said Patrick Henry, make the most of it.

Reservoir on Reservoir Drive

William Penn planned to put his mansion on top of Faire Mount, where the Art Museum now stands. By 1880, long after Penn decided to build Pennsbury Mansion elsewhere, city growth outran the capacity of the new reservoir system which had then been placed on Fairmount. An additional set of storage reservoirs were placed on another hill across East River (Kelly) Drive, behind Robert Morris' showplace mansion now called Lemon Hill (Morris merely called it The Hill); the area was eventually named the East Park Reservoir. In time, trees grew up along the ridge and houses got built; the existence of these reservoirs right in the city was easily forgotten, even though the towers of center city are now plainly visible from them. These particular reservoirs were never used for water purification; that's done in four other locations around town, and the purified water is piped underground to Lemon Hill, for last-minute storage; gravity pushes it through the city pipes as needed.

Now, here's the first surprise. Water use in Philadelphia has markedly declined in the past century. That's because the major water use was by heavy industry, not individual residences, so one outward sign of the switch from a 19th Century industrial economy to a service economy is -- empty old reservoirs. Only one-quarter of the reservoir capacity is in active use, protected by a rubber covering and fed by underground pipes. The rest of the sections of the reservoir are filled by rain and snow, but gradually silting up from the bottom, marshy at the edges. Unplanted trees have grown up in a jungle of second-growth, attracting vast numbers of migratory birds traveling down the Atlantic flyway. Although there are only a hundred acres of water surface here, the dense vegetation closes in around the visitor, giving the impression of limitless wilderness, except for the center city towers peeping through gaps in the forest. It's fenced in and quiet except for the birds. For a few lucky visitors, it's easy to get a feeling for how it must have looked to William Penn, three hundred or more years ago, and Robert Morris, two hundred years ago. In another sense, it demarcates the peak of Philadelphia's industrial age, from 1880 to 1940, because that kind of industrialization uses a lot of water.

The place, in May, is alive with Baltimore Orioles. Or at least their songs fill the air and experienced bird watchers know they are there. Even a beginner can recognize the red-winged blackbirds, flickers, robins, and wrens (they like to nest in lamp posts). The hawks nesting on the windowsills of Logan Circle suddenly makes a lot more sense, because that isn't very far away. In January, flocks of ducks and geese swoop in on the water surface, which by spillways is kept eight feet deep for their favorite food. Just how the fish got there is unclear, perhaps birds of some sort carried them in. The neighborhoods nearby are teeming with little boys who would love to catch those fish, but it's fenced and guarded much more vigorously since 9-11. In fact, you have to sign a formal document in order to be admitted; it says "Witnesseth" in big letters. Lawyers are well known for being timid souls, imagining hobgoblins behind every tree. However, there are some little reminders that evil isn't too far away. Just about once a week, someone shoots a gun into the air in the nearby city. It goes up and then comes down at random, with approximately the same downward velocity when it lands as when it left the muzzle upward. That is, it puts a hole in the rubber canopy over the active reservoir, which then has to be repaired. No doubt, if it hit your head it would leave the same hole. So, sign the document, and bring an umbrella if the odds worry you.

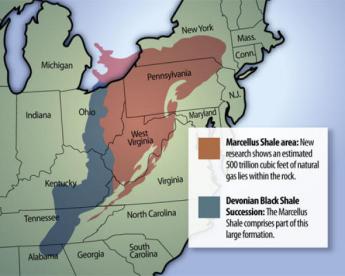

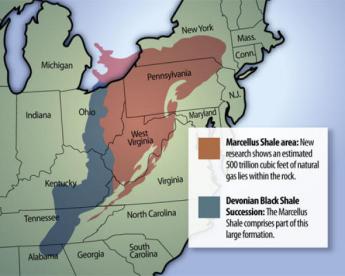

A treasure like this just isn't going to remain as it is, where it is. It's hard to know whether to be most fearful of bootleggers, apartment builders or city councilmen, but somebody is going to do something destructive to our unique treasure, possibly discovering oil shale beneath it for example, unless imaginative civil society takes charge. At present, the great white hope rests with a consortium of Outward Bound and Audubon Pennsylvania, who have an ingenious plan to put up education and administrative center right at the fence, where the city meets the wilderness. That should restrict public entrance to the nature preserve, but allow full views of its interior. Who knows, perhaps urban migration will bring about a rehabilitation of what was once a very elegant residential neighborhood. And push away some of those reckless shooters who now delight in potting at the overhead birds.

This whole topic of waterworks and reservoirs brings up what seems like a Wall Street mystery. Few people seem to grasp the idea, but Philadelphia is the very center of a very large industry of waterworks companies. The tale is told that the yellow fever epidemics around 1800 were the instigation for the first and finest municipal waterworks in the world. There's a very fine exhibit of this remarkable history in the old waterworks beside the Art Museum. But that's a municipal water service; why do we have private equity firms, water conglomerates, hedge funds for water industries, and other concentrations of distinctly private enterprise in the water? One hypothesis offered by a private equity partner was that the success of the municipal water works of Philadelphia stimulated many surrounding suburbs to do the same thing; it was surely better than digging your own well. This concentration of small and fairly inefficient waterworks around the suburban ring of this city might well have created an opportunity for conglomerates to amalgamate them at lower consumer cost. Anyway, it seems to be true that if you want to visit the headquarters of the largest waterworks company in the world, you go about seven miles from city hall and look around a nearby shopping center. If you are looking for the world's acknowledged expert in rivers, you go to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia on Logan Square and look around for a lady who is 104 years old. And if you have a light you are trying to hide under a barrel, come to Philadelphia.

Report Identity Theft to the Secret Service

The Internet provides new blessings, but new problems as well. Identity theft has now ballooned from a rarity to a fairly serious issue. After initial turf confusion, the issue has been assigned to the U.S. Secret Service. If it happens to you, that's where you make your anguished call. (1-877-ID-THEFT) or www.consumer.gov/idtheft

There's a certain logic to regarding identity theft as a modern form of counterfeiting, which has been with us since the days of William Penn. Shirley Vaias, representing the Philadelphia regional Secret Service, recently addressed The Right Angle Club of Philadelphia on the topic. It makes sense to learn the Service is headquartered on Independence Mall, across from the Mint. The crude forms of printing in the 18th Century made counterfeiting easy, and ever since the early days, there's been a race between improvements in technology and improvement in counterfeiting. We now have a paper with little red fibers in it, watermarks, serial numbers, color-shifting inks, microprinting of secret messages in the portraits, special magnetic strips, and probably lots of other clever things we aren't told about. The Bureau of Printing and Engraving is changing the currency, one bill at a time, and recently there was a new ten-dollar bill. A counterfeit version was in circulation within six hours.

ATM machines are equipped with counterfeit-recognition devices, and special gadgets are provided for banks and retail stores, but one detection device traditionally catches most fake bills. After handling huge amounts of currency, bank tellers catch a counterfeit just by the feel of the paper. Color photocopiers are getting better and cheaper, but of course, they can't change the serial numbers, so they aren't as smart as they seem. About one-hundredth of one percent of the currency in circulation appears to be fake, so you are pretty safe, but the possessor of a bad bill is deemed to be the one out of luck. The consequence is that many citizens suspect a bad bill, take it to a bank and have it instantly confiscated without recourse. That would seem to discourage reporting a counterfeit, encourage passing it off to an unsuspecting friend, and overall seems terribly unfair; but it results from the wisdom of the ages. Experience shows honest citizens are indeed tempted to try to pass the money on. While the banks don't enjoy being policemen, the effect is that counterfeits will circulate until they hit a bank, and thus confiscation is fairly comprehensive.

As the printing of money gets more complicated, the special presses needed to produce good money has become a monopoly of certain German companies, who sell the machines to other countries. Some of the American presses thus got into the hands of some Russians, who sold them to the North Koreans. So for a while at least, the North Korean government was printing American currency. It provoked vigorous countermeasures, the nature of which is confidential.

A bill of any denomination costs the government about half a cent to produce and lasts about four years in circulation. When tons of old bills are retired from circulation, the serial numbers are recycled; to an outsider, that sounds like an impossibly tedious job, but they say they do it. There's also the issue of seignorage, a term for the profit the government makes when the paper currency gets destroyed in one way or another, costing less than a cent to replace. Just how profitable the currency business is, cannot be accurately determined, because a lot of it is buried or hidden in mattresses and might someday resurface. But there is a substantial profit, which like any shrewd businessman, the government weighs against the cost of detection. Bail bonds and casinos are big sources of bad money, as could be readily imagined, and hence it is in their interest to get pretty sophisticated (and extremely unpleasant) about detection. On balance, however, it can be expected that legalized gambling in Philadelphia will promote more counterfeiting in the local economy, and hence is an offsetting cost of the tax revenue.

Over the centuries, governments have learned how to cope with counterfeiting, and there is actually much less of it than a century ago. You win some and you lose some; life just goes on. With internet identity theft, however, the criminals are developing techniques faster than governments have learned to combat them, and it is governments who struggle to catch up. Unfortunately, everybody takes a business-like approach to the matter, asking whether the precautions cost more or less than the losses. It would seem that if money continues its migration from paper currency to bookkeeping entries, it will eventually seem unsatisfactory for only one party in a transaction, a bank let us say, to keep the books while the public simply trusts them. Eventually, each individual will be forced to seek the protection of some sort of computerized system keeping the counter-parties honest, on behalf of the public, and to prevent a paralysis of commerce. Identity theft is getting expensive enough to warrant the effort.

Just how to do all that is not too clear. So, in the meantime, just let the Secret Service figure it out.

Rejecting Preventive Health Care for Good Reason

WHILE we debated in 2010 whether to disregard what could be afforded, and provide sickness care to all, the idea subtly changed to providing "health care" for all. That is, the proposal was not merely to expand sickness care to everyone, it included an indefinite expansion of what everyone would get, and who would provide it. Medical care is provided by physicians, sickness care is provided by doctors, nurses, and hospitals, and healthcare is provided by a much larger undefined group of "providers". No wonder it costs more, and therefore a surprising number of people are unsure they do want all of it. It's almost a certainty that most people do not want to lose control of this definition, at least if it is to apply to them, personally. The issue centers on "healthcare" versus sickness care". How's that, again?

Preventive Health Care poses unique issues for seniors.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

For example, the notion that preventing disease is superior to treating disease, goes back at least to Benjamin Franklin. Arguing that the Pennsylvania Legislature ought to help build the nation's first hospital, Franklin offered the truism that it saves money in the long run to treat people early and get them back to work. Franklin could hardly have foreseen that it isn't always true. Preventive medicine implies it is cheaper to spend small amounts, possibly every year, for many people, than to spend large amounts for a few. It's a matter of arithmetic, of course, and doesn't always have the same answer. When the math works against a preventive approach, it's usually argued the gain in health is worth it; but that's not invariably the case, either. Once a person ceases to be an infant, the equation rebalances. And as an individual approaches end of life, his renunciation of what it takes to prolong life gathers more respect. It's a conflicted opinion, of course. Older people are outraged by any suggestion their lives do not deserve to be prolonged, but still, outspokenly prefer to die rather than wear a colostomy bag, or a respirator, or be fed with a spoon. If they are Jehovah's Witnesses and refuse transfusions, that too, commands more respect when they are elderly. This is a familiar problem, not a new one. What's new is more subtle and pervasive.

The public probably does not fully appreciate the disappearance of what might be called capricious diseases, caused by the operation of chance, or God's will. These are fatal illnesses like heart attacks, strokes, epidemics, and other things not anyone's fault. Except for cancer and Alzheimer's Disease, most really common serious illnesses which remain, are to some extent self-inflicted. Smoking causes lung cancer, alcoholism causes accidents and homicides as well as cirrhosis of the liver, taking recreational drugs damages lives, unprotected sex causes HIV. Obesity causes hypertension and diabetes, neglecting your medicine undermines treatment. If this keeps up, we are going to see the day when every obituary will seem too shameful to print. Poor Jud is dead; it's his own fault.

It's maybe even worse than that.The 2000-page Obama care plan was too complicated for even the Congressional committees to understand. But the public was not hostile for technical reasons, the public was irked at the idea. All the President's celebration of saving money through mandatory preventive care provoked the public to tell him, Get off my back. Almost every smoker has tried at least once to quit, absolutely every obese person has repeatedly tried to lose weight unsuccessfully. It's hard, let's see you try it. And now it goes beyond nagging, we are going to take the position that every person with a self-inflicted disease is costing the nation money we can't afford. The country has a right to punish people who drive us to bankruptcy. Let's have some Wellness police, and fair but firm punishments. Is that really what Obama has in mind? Well, sir, you just get off my back.

Even so compliant and dutiful a person as my late wife declared that when she got to be seventy, she was going to try marijuana. The fact that she actually lived thirteen years longer without doing it, did not change her basic attitude. When you get to a certain age, many of the old rules don't apply to you, doggone it.

Recalling the Names of Acquaintances

As age creeps up on us, just about everyone has a little trouble recalling the name of old acquaintances, particularly if they come upon us unexpectedly. Reactions to this affliction vary tremendously, with some folks concluding that Alzheimer's Disease is surely here already, so they run away and hide. Other seniors are more self-confident and unashamedly go ahead with little strategies to cope with this problem. When you sort things out, you tend to find that shy and retiring people withdraw from social contacts because of self-consciousness, whereas bluff, bold extroverts plunge ahead with strategies they have devised to cope with matters. Neither one of them can remember a lot of names. The extroverts are usually very happy to share their secrets; a whole social group can be transformed by one loud, happy, unashamed coper sharing his techniques.

The late Doctor Francis C. Wood, formerly Professor of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania after whom a number of professorships, institutes, and lectures are named, once made a little speech at a reception held at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. "When you see somebody at a party whose name you ought to recall but can't, just stride right up to him with your hand held out. Just say your name like a gentleman, like 'Fran Wood," and he will invariably grab your hand gratefully and tell you his name, like 'Jim Jones, Fran. How are you?' After that, you'll get along just fine."

This isn't a medical matter at all. It's a matter of self-confidence and learned techniques. Dick Maas, who is a resident of the Beaumont CCRC in Bryn Mawr PA, was recently proud to describe his own technique in the Beaumont News as follows:

"Let's start with the obvious conclusion that one can't remember something one didn't hear in the first place. Introductions often are given in a social situation, which usually means one is surrounded by loud noise. Furthermore, the person doing the introduction may have a soft voice or poor diction.

There's hope, however. One can employ a little trick that's socially correct and psychologically useful: Shake hands with your new acquaintance! Hang on until you hear the name clearly and correctly. If necessary, hang on and say, 'I didn't get your name. Would you please repeat it?' Even ask for a spelling if need be. Don't release the hand until you've heard it correctly and repeated it back."

|

| Handshake |

It isn't always necessary to use a name or shake hands. In Haddonfield where I live, the custom grew up years ago that everybody says, "Hello" or "Good Morning" (Good Morning preferred) to everybody one meets on the street -- before lunch. There's no hesitation about it, that other person is going to say "Good Morning," so you might as well get ready for it. Of course, it's true that some people don't know what to do with themselves, and retreat back into their shells, awkwardly trying to pass you by without acknowledging your greeting. You can either shrug your shoulders and assume that repetition will gradually bring that newcomer around in a few days or weeks, or else you can refuse to let them do that to you. Step in his way and say it louder. To get away with this you have to be prepared to say something about the weather or your dog or the morning news, which is a pleasant way of saying you weren't belligerent about it, just showing them the way things are done in Haddonfield. Pass yourself off as uncontrollably extroverted. And be sure to smile. This sort of custom is a matter of population density. Up in Alaska a trapper who passed within a mile of another trapper's cabin without saying, "Howdy" was inviting a knife fight about the insult. In New York's Times Square, by contrast, a pedestrian is within walking distance of two hundred thousand people; greeting everybody is an impossibility. Which leads me to a personal story.

At the Pennsylvania Hospital we had an orderly named Sam who was deeply religious and went around handing out religious tracts. He was pleasant and did a lot of work, so no one interfered. One day, I was walking in Times Square with my wife on one arm and my mother on the other. Looking ahead, I could see a crowd had formed around an orator on a soapbox, who was none other than Sam. I said nothing, but as we drew closer, my mother exclaimed about it and maneuvered the three of us up to the ringside to see the excitement. Sam stopped talking to the crowd, and shouted, "Hello, Doctor Fisher". So, of course, I replied, "Hello, Sam"; and the three of us kept walking down the street. After we had gone two blocks in puzzled silence, my mother abruptly stopped walking, stamped her foot, and said, "All right young man. Just who is this Sam?"

Rare Causes of High Blood Pressure

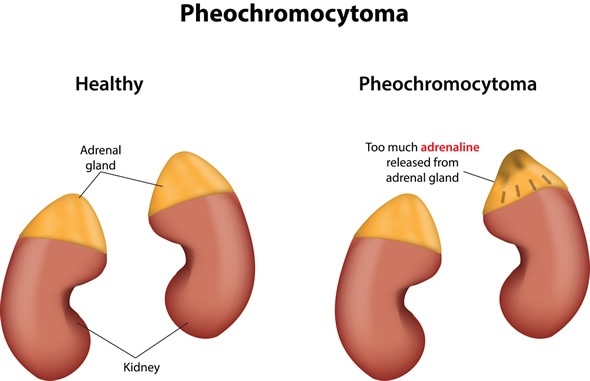

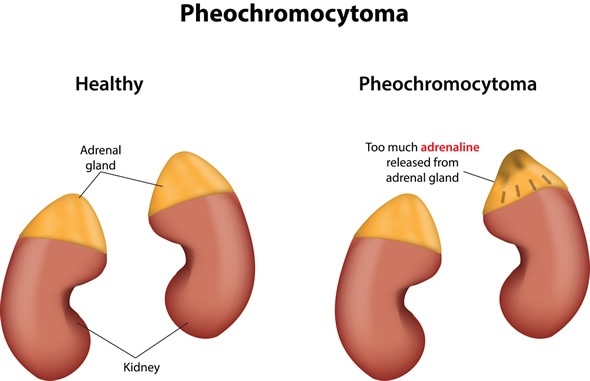

|

| Pheochromocytoma |

Back in the days when doctors couldn't do much to help hypertension, a great deal of time and effort was expended on looking for the rare types of high blood pressure that maybe we could do something about. One such was a condition known as pheochromocytoma ("Grey-colored tumor" of the adrenal gland.) The chances of finding such a case were remote, so the aphorism grew up that "If you make a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma -- you are probably wrong."

At a recent Grand Rounds session at Jefferson Medical College, the topic was treatment-resistant hypertension. In other words, the situation had now reversed. It was now so routine to be able to control hypertension with drugs, that we have had to invent a new term to describe those remarkably few cases which fail to respond to treatment -- Resistant Hypertension. I could see the young doctors had grown used to this paradox without noticing it was something to comment upon.

It is now my observation we have fallen into the habit of searching for these rare conditions only among cases which first sort themselves out as Resistant Hypertension. From once searching desperately for something to treat, we have grown to assume that something we can treat doesn't need further investigation. Implicit then is the unwarranted assumption that hypertension caused by unusual things like Pheochromocytoma always appears as an instance of Resistant Hypertension. Does anyone know of studies which show this is reliable?

No one answered, so I guess not.

Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution

|

| Richard Arkwright |

The Industrial Revolution had a lot to do with manufacturing cotton cloth by religious dissenters in the neighborhood of Manchester, England in the Eighteenth Century. What needs more emphasis is the remarkable fact that Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution both originated about the same time, in about the same place. True, the industrializing transformation can be seen in England as early as 1650 and as late as 1880. The Industrial Revolution thus extended before Quakerism was even founded, as well as long after most Quakers had migrated to America. No Quaker names are much mentioned except perhaps for Barclay and Lloyd in banking and insurance, and Cadbury in candy. As far as local history in England's industrial midlands is concerned, the name mentioned most is Richard Arkwright, whose behavior, demeanor and beliefs were anything but Quaker.

He seems to have invented nothing, stealing the patents and ideas of others freely, while disgustingly boasting about his rise from rags to riches. Some would say his skill was in the organization, others would say he imposed an industrial dictatorship on a reluctant agricultural community. He grew rich by coercing orphans, convicts and others he obviously disdained into long, unpleasant, boring and unwelcome labor that largely benefited him, not them. In the course of his strivings, he probably forced Communism to be invented. It is no accident that Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto while in Manchester visiting his friend Friedrich Engels, representing reasonably well the probable attitudes of Arkwright's employees. What Arkwright recognized and focused on was that enormous profits could flow from bringing piecework weaving into factories where machines could do most of the work. Until his time, clothing was mostly made by piecework at home, with middlemen bringing it all together. The trick was to make clothing cheaper by making a lot of it, and making a bigger profit from a lot of small profits. Since the main problem was that peasants intensely disliked indoor confinement around dangerous machines, the industrial revolution in the eyes of Arkwright and his ilk translated into devising ways to tame such semi-wild animals into submission. For their own good.

|

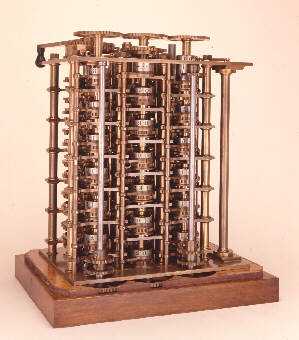

| Charles Babbage |

Distinctive among the numerous religious dissenters in the region, the Quakers taught that it was an enjoyable experience to sit indoors in quiet contemplation. Their children were taught to submit to it at an early age, and their elders frequently exclaimed that it was a blessing when everyone remained quiet, enjoying the silence. Out of the multitude of religious dissenters in the first half of the Seventeenth century, three main groups eventually emerged, the Quakers, the Presbyterians, and the Baptists. Only the Quakers taught that silence was productive and enjoyable; the Calvinist sects leaned toward the idea that sitting on hard English oak was good for the soul, training, and discipline was what kept 'em in line.

|

| babbagemaq.jpg |

The Quaker idea of fun through daydreaming was peculiarly suitable for the other important feature of the Industrial Revolution that Arkwright and his type were too money-centered to perceive. If workers in a factory were accustomed to sit for hours, thinking about their situation, someone among them was bound to imagine some small improvement to make life more bearable. If such a person was encouraged by example to stand up and announce his insight, eventually the better insights would be adopted for the benefit of all. Two centuries later, the Japanese would call this process one of continuous quality improvement from within the Virtuous Circle. In other cultures, academics now win professional esteem by discovering "win-win behavior", which displaces the zero-sum or win/lose route to success. The novel insight here was that it has become demonstrably possible to prosper without diminishing the prosperity of others. In addition, it was particularly fortunate that many Quaker inhabitants of the Manchester region happened to be watchmakers, or artisans of similar trades that easily evolved into the central facilitators of the new revolution -- becoming inventors, machine makers and engineers.

The power of this whole process was relentless, far from limited to cotton weaving. When Charles Babbage sufficiently contemplated the punched-cards carrying the simple instructions of the knitting machines, he made an intellectual leap to the underlying concept of the tabulating machine. Using what was later called IBM cards, he had the forerunner of the stored-program computer. There were plenty of Arkwrights getting rich in the meantime, and plenty of Marxists stirring up rebellion with the slogan that behind every great fortune is a great crime. But the quiet folk were steadily pushing ahead, relentlessly refining the industrial process through a belief in welcoming the suggestions of everyone.

Quaker Efficiency Expert: Frederick Winslow Taylor 1856-1915

|

| F.W. Taylor |

For at least seventy-five years after Fred Taylor turned it down, any rich smart Philadelphia Quaker attending Phillips Exeter would have been automatically admitted to Harvard. We don't know why he did it, but instead F.W. Taylor just walked a few blocks down the hill from his Germantown house and got a job at the Midvale Steel Company as an apprentice patternmaker. During the twelve years, while he rose to become chief engineer of the company, he took a correspondence course for a degree in mechanical engineering at Stevens Institute and invented a process for making tungsten steel, called high-speed steel. That made Midvale Steel rich, but Taylor was going to make Philadelphia rich, and after that, he was going to make America rich. When he died, he was widely hated.

Evidently his lawyer father greatly admired German efficiency, having sent little Freddy to a famous Prussian boarding school where he was in attendance at the time of the

|

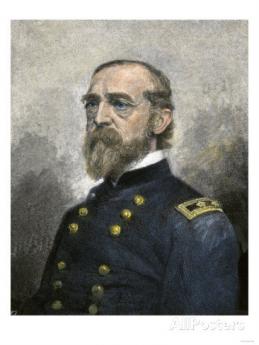

| General von Moltke |

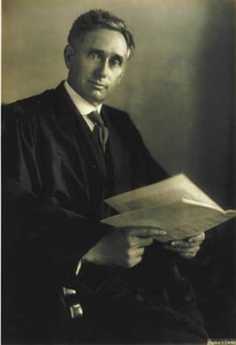

Battle of Sedan. General von Moltke had used Prussian efficiency and discipline to defeat those indolent lazy French, and Fred Taylor evidently absorbed and retained these stereotypes for the rest of his life. Whatever he was looking for at Midvale Steel, what shocked him most was to find workers "soldiering on the job". That's a Navy term, by the way, invented by sailors to describe the useless shipboard indolence of any Army they were transporting. Taylor later went to Bethlehem steel, reduced the number of yard workers from 500 to 180, and was promptly fired. It seems that most of the foremen at the plant were owners of local rental houses, which were emptied of tenants when Taylor reduced the workforce. Even management came to mistrust Taylor. When the railroads wanted a rate increase, Louis Brandeis defeated them with the argument that they wouldn't need higher rates if they adopted Taylor's system of efficiency. In his later years after he became enormously rich, he toured the country giving speeches without fees, promoting the doctrine of finding the one best way and then doing everything that way.

|

| Louis Brandeis |

Over time, Frederick Taylor had come to see that the industrial revolution had proceeded to the factory stage by merely bringing craftsmen indoors, each one treasuring his little trade secrets. Bringing the point of view of the company's owners onto the shop floor, Taylor could see how vastly more profitable the steel company would be if all those malingering tradesmen would stop soldiering on the job. No doubt the young Quaker soon learned that little was to be accomplished by remonstrating with workers, just as bellowing foremen had learned that bullying was also useless. Out of all this familiar scene emerged Taylorism, the idea of paying financial incentives to those who produced more, splitting the rewards of efficiency with the management. It sort of worked, but it didn't work enough to satisfy F.W. Taylor. When he walked around with a stopwatch, he collected the data showing how much more might be produced if the workers were perfectly efficient. Not only did that create the stereotype of the stop-watch efficiency expert, but it also provoked Congressional hearings and federal law against stopwatches which stayed on the books from 1912 to 1949. Although management responded by forming dozens of Taylor Societies to honor the approach, the unions invented the term "Taylorism" and bandied it about as the worst sort of epithet. Curiously, the Taylor approach proved to be enormously appealing both to Lenin and Stalin, who applied it as a central part of their five-year plans and general approach to industrialization. As we now all recognize, the Communist approach was a two-tier system instead of the three-tier system that was needed. It isn't enough to have a class of comrades called planners and another called workers; you need a layer of foremen, sergeants and chief petty officers in the middle. In addition to the elaborate time and motion studies leading to detailed written procedures, there needs to be an institutional memory for the required skills of the trade. In a funny sort of way, Fred Taylor the Quaker may have organized the downfall of the communist state before it was invented.

|

| Herbert Hoover |

Another peculiar outgrowth of Taylorism may be the partisan lines of our own political parties. If you trace the American ideological divide to the 1932 election of Franklin Roosevelt, you can see we are still fighting the battles of the depression. It happens that Herbert Hoover, another Quaker, was totally captivated by Taylorism. Not only that, he was adamant that to get rid of the depression all the country needed was to return to self-reliance, individual responsibility, and hard work. Those were qualities Hoover himself had in superabundance. One telling remark that he probably regretted saying but nonetheless firmly believed was, "If a man hasn't made a million dollars by the time he is forty, he can't amount to much." Franklin Roosevelt had the million all right, but his family had given it to him. The Cadburys and Clarks could have given it to Fred Taylor, too, but he chose to make it himself.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1296.htm

Powel House, Huzzah!

|

| Elizabeth Powel |

If George Washington were still alive he would no doubt be a Republican, but the term Republican Court actually has nothing to do with R's and D's. It was a scheme deliberately cooked up by Washington and Madison to enlist support by the new government's important ladies for a modified version of a European royal court, to make thirteen colonies into a cohesive nation. A most remarkable thing about it was its frank imitation of the royal courts, something only the Father of His Country could pull off in former colonies which had just fought an eight-year war to be rid of the monarchy. It is one more great testimony to the faith of Americans in George Washington; but it also testifies to the power of enthusiastic women, once they agree on a project. Chief among the leaders in this court was Elizabeth Powel, along with her niece living around the corner on Spruce Street, Anne Willing Bingham. Recently, the Peale Society of the Academy of Fine Arts held a candlelight dinner in Mrs. Powel's magnificent second-floor dining room, while scholars of the history of the Republican Court told assembled notables of Philadelphia what had once been what, during the first ten years of the Republic.

|

| Dining Room |

Members of the early Congress were largely the same men as the founding fathers of the Constitutional Convention, hand-picked by Washington and Madison to persuade the legislatures of their colonial states to give up state sovereignty, for a unified nation. There was the difference that now they brought their wives to live in Philadelphia during sessions of Congress. Those women wanted to know each other and wanted to have something exciting to do together in the largest city in the nation. Their husbands knew well how politically useful it was to be socially acquainted in this way, so everybody liked the idea of suddenly becoming nationally connected. The initial idea proved unworkable. Martha Washington was supposed to become Lady Washington, reigning over weekly receptions.

|

| In Our Cups |

But Martha, unfortunately, wasn't up to the task, and Anne Bingham whose rich husband had taken her on lengthy tours of European royal courts, moved right in and took charge of this project. Besides her cousin Elizabeth Powel, notable members of this social whirl were the two daughters of Chief Justice Benjamin Chew, Alexander Hamilton's wife, and various members of the Shippen and Willing families. Members of the family of Lord Sterling of New Jersey, Charles Carroll of Carrolton, Maryland, Cadwaladers of various sorts, and a number of other names famous from then until even today joined their affiliations with ladies from other states through parties and even some weddings. John Adams was particularly awestruck by the poise and beauty of Anne Bingham, although Abigail Adams may not have been quite so infatuated. It was a dizzy whirl, with dinner parties the central activity just as they are in Philadelphia even today. Country bumpkins had to learn how to dress, to talk and to eat with the right spoon and keep their elbows off the table; those who could tactfully show them what was what were friends for life. Centuries later, Emily Post made a fortune writing books about these rules.

|

| Republican Court |

In those days, they even had their war cry, which was to raise a glass and shout back "Huzzah" in response to the proposer of a toast, who had raised his glass starting the warcry. It wasn't "Skol" or "Cheers" or "Here, here" if you knew what was what; it was "Huzzah". Most fashionable dinners had at least twenty courses, but the ladies didn't eat them. It was a whispered instruction among the ladies that they should eat before the dinner, so they could gracefully decline to gobble up goodies, and spend their time in gay conversation or waiting to be asked to dance. Drinking and eating, especially drinking, was for the men at the party, although naturally the many courses of the banquet were put in front of the ladies to be airily ignored. When George Washington was present as he often was, or even La Rochfoucault himself, it was important to remember every spoken word.

And, you know, it worked. When these important people went back home, they took the customs of the Republican Court with them. The American diplomatic corps found the equivalent of minor-league training for their efforts on behalf of the country abroad. Politics was easier if you personally knew your adversaries as well as your allies. The persistence of the same family names in the Social Register, the lists of The Four Hundred and other compilations of high society show that Anne Bingham and Elizabeth Powel did indeed know what they were doing, and for that matter, so did George Washington. If anyone else had been at the top of this heap, Thomas Jefferson stood ready to attack with all his might.

|

| Amity Button |

But he and even Patrick Henry didn't dare attack Washington. The aristocrats of Old Europe probably did sneer at this amateur effort, and in some circles still, do. But the inability of absolutely any other group of nations, whether European, Asian or South American, to unite peacefully is a thumb in the eye of anyone who mocks George Washington's little Philadelphia creation. And to think it all began right here, right here in the Powel House, right here in the dining room on the second floor. For that, folks, one thunderous "Huzzah!"

REFERENCES

| A Portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powell: 1743-1830 David W. Maxey ISBN-13: 978-0871699640 | Amazon |

The Best Density for an Idea

|

| Gutenberg |

Books were copied by hand before the invention of the printing press; every word counted. Quite often, that made the writing hard to grasp, too concise for comprehension by a normal reader at a single reading. An example would be Aristotle's comment on the nature of cities:

The partnership finally composed of several villages in the city-state; it has at last attained the limit of virtually complete self-sufficiency, and thus, while it comes into existence for the sake of life, it exists for the good life.... it is clear that the city-state is a natural growth, and that man is by nature a political animal, and a man that is by nature and not merely by fortune citiless is either low in the scale of humanity or above it.

Aristotle, Politics, I, i, 8-9, Translated by H. Rackham, and quoted by Sir Peter Hall.

Many modern readers glancing at this little paragraph would pass on to other concerns, confirmed in the conclusion that Aristotle is unreadable. A few who struggle through will see it is a collection of six epigrams. In the modern spirit of one-liners, they would be:

- A city is a collection of villages that, together, make a self-sufficient unit.

- A city grows because people are drawn there for economic reasons.

- City-dwellers don't return home because the city seems a more pleasant place to remain.

- People may come and go, but a city is destined to grow in size, on net balance.

- People innately prefer to live in clusters (politis).

- Those few people who don't like to live in a convivial cluster, are either boobs or saints.

Taking the trouble to tease his paragraph apart, one must acknowledge, Aristotle really has a lot to say about cities. By contrast, the author who quotes him on the frontispiece, Sir Peter Hall, uses eight hundred pages to make roughly the same arguments in Cities in Civilization. Although Sir Peter is a master of almost lyrical prose which touches on over 3000 literary citations, the six ideas are stretched too far on such a framework. Sir Peter controls his material and does not wander. The reader wanders.

It seems so terribly cruel to sound negative about a nice old gentleman, who must be an enormously entertaining person to share dinner with. And who has written a masterful prose poem about cities we all love. His book is well worth the price to buy, well worth the time to read. But it is overly long to support a half-dozen controversial ideas, just as Aristotle's seventy-five words are too few. The average reader will readily accept about two of the six propositions without elaboration, and will probably reject about two others in spite of all efforts to persuade.

When it comes to this sort of thing, the Economist, also written in Great Britain, has the most effective formula. Most of its pieces are written by one person and re-written by a second. After reading about a thousand such articles, the formula gets a little tiresome. But the density is nevertheless right for the modern reader. Three paragraphs for what Aristotle would accomplish in an epigram; ten pages for one really new, and difficult, idea.

Plain Speech

|

| Goofy Cartoon |

Philadelphians don't dislike New York; to them it's like an occasional visit to Disneyland. One day, a Main Line lady dressed her seven-year-old daughter in a little hat, shiny Mary-Jane shoes, and white gloves and the two went off to Gotham. The little girl kept her nose glued to the window of the taxicab.

They passed a midtown street corner of Fifth Avenue, where a cluster of young women, all painted up and overdressed, were waving at passing cars with one hand while brandishing a cigarette with the other. The little girl said, "Mommy, what are those ladies doing?" To which her mother replied, "Why, dear, they are waiting for their husbands to come to take them home."

At this point the cabbie turned around in the front seat and snarled, "Lady, why don't you tell your daughter the truth? You know those are Ladies of the Evening."

After a little silence the little girl asked, "Mommy, do Ladies of the Evening have any babies?"

"Yes, of course, Dear " replied the mother. "Where do you suppose taxi drivers come from?"

Methods of Thought: Scientific, Logical, Future

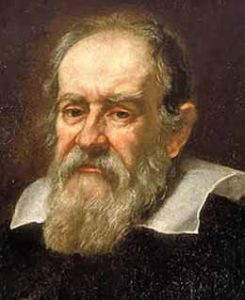

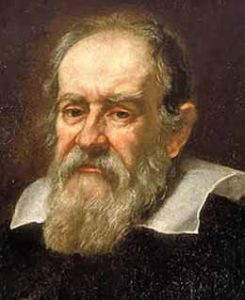

|

| Galileo |

Early in the Sixteenth century -- some say it was Galileo who started it -- the Scientific Method appeared. A hypothesis was generated, then subjected to experiment. Flaws were detected, the hypothesis re-modified, then tested again. The central characteristic of truth was established: reproducibility. The same test should always yield the same result in the Scientific Method.

A few decades later someone -- probably Sir Francis Bacon -- applied a modified Scientific Method to the common law. What seemed like a good remedy for a dispute was tested in the courts by entertaining appeals of similar cases, to test how the remedy seems to turn out. The reliance could not be on systematic experiments, so it had to rely on nature's experiments. Of the two disciplines, the scientific thesis-hypothesis-new thesis came to rest with firmer conclusions sooner than the common law did because scientists could devise systematic tests. A Judge, on the other hand, must wait for roughly the same circumstances to come up again before reproducibility can be determined, and that sometimes takes decades. Since a Judge can scarcely be expected to arrange his cases experimentally, non-comparable circumstances are always potentially present.

In both Experimental science and the Law, however, increased velocity --progress -- is an independent variable. It was celebrated enough during the Enlightenment to embolden public acceptance -- not merely of the validity of the Scientific Method, but -- of science itself and the Law itself. During those three hundred years after Galileo dropped bullets of differing sizes down the Tower of Pisa, rapid progress created a new respect for scientists and lawyers. Naturally, that led to lessened prestige for priests and kings, hence disruptions of existing power arrangements. History was the score-keeper of these turmoils, but History itself also became a variant of the scientific method. Unfortunately more than even the Law, History had to wait long periods for natural experiments to present themselves. Unfortunately, also, the effect of history on politics created an incentive for misrepresentation, now one of its main weaknesses.

Meanwhile untested Philosophy languished. The human uterus was not bicornuate, as anyone could see by examining one. Understanding only crept forward in a petty pace among logical philosophers; a century was brief in their vocabulary. For their part, Religions made a poor showing compared with the Common Law, particularly when advocating patterns of behavior. Religions were too rigid, too mysterious in their conclusions, provided too little guidance and too much grief. Too often the object seemed to be a skill in making the worse appear the better reason or acquiring detestable techniques of Oxford debating societies, where framing arguments in sly ways advances inappropriate victories. Logic acquired a bad name when its practitioners could easily be seen to prefer victory for the debater over advances for truth. And yet it does seem much too soon to discard logic and debate; indeed, they may be on the threshold of their finest hour.

A professor of mathematics of one of America's greatest scientific graduate schools, recently expressed his confusion about the nature of logic. Experiencing platoons of math graduate students marching past his blackboard, he commented on the extraordinary diligence of mostly foreign-born students, perfectly content to spend twenty daily hours studying to achieve distinction. "And yet," he said, "Every year there are two or three who never come to class, except to take the test. And they always get the highest possible grades." His inability to discuss the inner workings of such minds was related to the fact that he seldom met them in person. That such logical prodigies are not rare is also seen at chess tournaments, where players of no particular professional distinctiveness are to be observed moving among the chessboards of twenty opponents, occasionally even doing it blind-folded. The rest of us cannot hope to match such performances ourselves, so we are not entitled to scoff at the achievement, or belittle its potential for re-revolutionizing the science of thought.

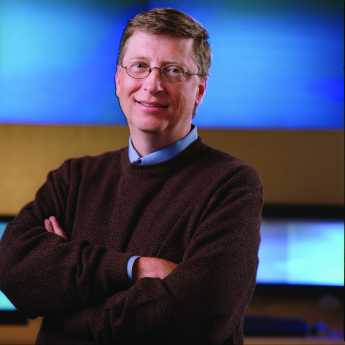

|

| Bill Gates |

Academia sometimes expresses and should express more often, its discomfort that Bill Gates and a number of other certifiable geniuses have found colleges disagreeable, and drop out. When one of them becomes the richest man in the world before he is forty, at least it becomes necessary to acknowledge that his talents are not a one-trick pony. These people seem to be differentially attracted to computer science, perhaps instinctively recognizing that machines seem capable of exceeding the largest human memory, and their integrated processors sit idly waiting for some genius to put them to work. Even today, with mere mortals writing the programs, we are informed that seventy percent of stock market transactions are conducted between two machines, operating unattended. Perfecting stock transactions may well be approaching its useful limits, but potentials for improving the world's daily activities are so vast that grammar school children could easily list a hundred possibilities. What children cannot do is devise something to motivate a man to remain productive, after he already has fifty billion personal dollars. And another thing children cannot do is describe an educational system appropriate for such extraordinary people when they presently find nothing in the classroom worth their attention. We are giving up the Space Program as not worth its cost. Well, here's a goal which is obviously worth its cost, if only to stay ahead of international competitors in an atomic age.

Philosophy Means Science in Philadelphia

|

| American Philosophical Society Seal |

In the age of the Enlightenment, science was called natural philosophy; that accounts for the present custom of awarding PhD. degrees in chemistry and botany. The sort of thing which interested Ralph Waldo Emerson was called moral philosophy, and you will have to visit some other place than the A.P.S. if that is what interests you. Roy E. Goodman is presently the Curator of Printed Material (some would say he was chief librarian) at the American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin who was clearly the most eminent scientist of his day, having discovered and explained the nature of electricity.

|

| Roy E. Goodman |

Roy Goodman is descended from cowboys and rodeo stars, but in spite of that he gave an entertaining talk recently at the Right Angle Club about this society devoted to useful knowledge, this oldest publishing house and scholarly society in America, once the home of the U.S. Patent Office, and scientific library and museum. They have many rare items in their collection, but the unifying theme is not a rarity, but curiosity. You might say some of the items reflect the whimsy of Franklin, but it would be fairer to say it is an enduring monument to Franklin's universal curiosity about all things.

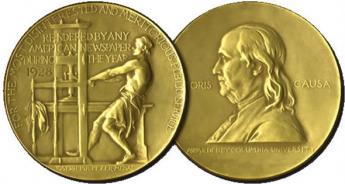

|

| Nobel Prize Medal |

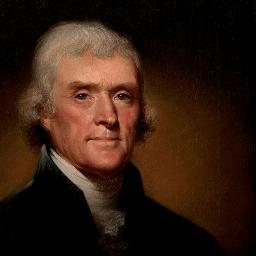

There are about 900 members of APS, about 800 of them Americans, about 100 of them winners of a Nobel Prize. Let's just make a little list of a very few notables in the past and present membership. Start with the first four Presidents of the United States, add Alexander Hamilton and Lafayette, David Rittenhouse and Francis Hopkinson and you get the idea that Founding Fathers got in early. Robert Fulton, Lewis and Clark, Alexander Humboldt, John Marshall were early members, and more recent ones were Madame Curie,

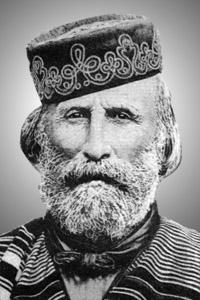

Philadelphia Mafia: The First Fifty Years

|

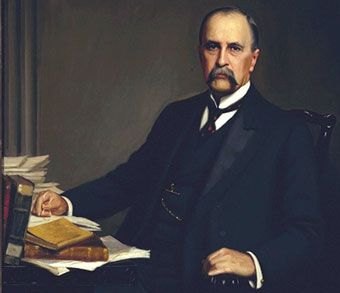

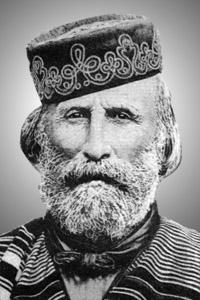

| General Giuseppe Garibaldi |

General Giuseppe Garibaldi unified Italy, but a great many Italians either didn't want to be unified, or emigrated to America after 1860 to escape the turmoil. The far western tip of Sicily was the most remote place in Europe, protected by mountains and volcanoes, speaking its own language, and loyal to no government except its own informal one. Over a period of centuries, secret traditions of feudalism and invisible governance had protected Sicily from invaders of various sorts. Although religion was a powerful force, theirs had traces of the Greek Orthodox Church; allegiance to the Vatican faded out as the local priesthood got closer to it. These people mostly wanted to be left alone, and dealt with outside authority in various devious ways, not stopping with murder if necessary. Informal taxes were collected as "paid protection" since a secret army costs money if only to support funerals and soldiers' widows. Rank within the underground army was identified by various degrees of "honor", which could sound vague but were in fact quite unambiguous. Central to the code of the Sicilian underground government, like all guerilla movements was a strict rule of silence, "omerta". As an intern in a hospital accident room, I have seen members of this organization actually go to their deaths, grimly repeating the mantra, "I don't know nuthin."

|

| Benito Mussolini |

Italy may have been unified by Garibaldi in the sense of being freed of French, Austrian and Papal domination, but unification was far from peaceful and contented, with losers often choosing emigration. A second wave of emigration was provoked by the harsh rule of the dictator Benito Mussolini, who determined to squelch underground resistance once and for all.

Western Sicilians originally chose New Orleans as their new home, which unfortunately for them already had its own secret society, the Ku Klux Klan. A prompt reaction to the "Italians" with ten or twelve lynchings soon convinced the Sicilians to resettle elsewhere. It seems possible that some of the later techniques of the Mafia were learned from the Klan. In any event, the Sicilians split into two main groups, one going to New York and the other to Philadelphia. Offshoots of the New York group moved to the mining areas of Luzerne County in central Pennsylvania (Hazelton), while another early group migrated to Norristown. There were, of course, links of intermarriage among these groups, but in the early years they drifted apart as separate colonies.

Italian immigrants were no exception to the common tendency of new immigrant groups to gravitate into crime. Records of the Pennsylvania police and jail systems for three centuries show successive waves of inmates with surnames identifying Scottish, then German, then Irish, and eventually Italians. At present, seventy percent of prison inmates are black. Almost without exception, the main victims of immigrant predation have been members of their own immigrant group. Immigrants are easily victimized, somewhat defenseless, and uncertain of the assistance of local law enforcement. Among the most famous of the lawless predator groups among the Italians was the Black Hand, whose specialty was extortion with notes signed with a black hand symbol, enforced by putting bombs under porches. Locals will show you a place on Ninth Street a couple of blocks from the Pennsylvania Hospital where the Black Hand blew things up. The Black Hand, however, was not the Mafia; it exemplified what the Mafia was formed to control.

The Italian community for fifty years was centered on Christian Street, mostly between Eighth and Ninth, gradually migrating westward toward Eleventh Street. Christian Street had been named by the Swedish Philadelphia colony after their monarchs, but the original Swedes tended to remain in Queen (Christina) Village, along Delaware, while the newer migrants drifted to newer areas. During the Civil War, northern railroads heading south ended in Camden. In time, the main Civil War traffic ferried across the Delaware River to wharves at the foot of Washington Avenue. South Street was the honky-tonk area, with a black community growing along with it. After the War, an immigration station was constructed in the Washington Avenue wharf, and the new Italians tended to settle nearby. As the streets were extended westward, the street names were also extended, but the region of Eighth and Christian was largely open fields when the Italians moved into the area, and never had been Swedish. Although there were forty or more murders in the block of Christian from Eighth to Ninth in ten years after the first World War ("Murderers Row"), in modern times the neighboring region is prized by Italian residents as an extremely safe place to live, because the Don likes it nice and quiet.

While it is probably true this safety net quality might not be so evident to blacks and Vietnamese, the safe streets for Italians feature are universally attributed to the Mafia. The Sicilian group quickly reestablished the secret army of "soldiers" and "dons" (usually one don overseeing ten soldiers), started collecting taxes in the form of protection money from the local residents, and putting one "capo" in overall command. You had to be a Sicilian, and a Western Sicilian at that, to be eligible for membership in this secret army. The hierarchy was secret but could be surmised by the elaborate "respect" paid by one to another.

My office partner, Dr. Robert Gill, tells a story illustrating the paying of respect. He was called in consultation to an Italian home by Dr. Baglivo, a highly respected general practitioner in the Italian community. The two of them walked down Eighth Street, and as they passed a barber shop, Dr. Baglivo suggested they both go in for a haircut. Evidently, the patient to be visited was a very important person, and as they went in the shop, Dr. Baglivo introduced Dr. Gill to the group of assembled loiterers as the big doctor from the Pennsylvania Hospital, come to visit you-know-who with the last name ending in a vowel. The group jumped to their feet, in respect, and the barber turned to the lathered-up, half-shaved man in the barber chair. "You!", he cried out, "Get out of that chair! Let the Doctor have a haircut.!" The man dutifully scrambled out of the chair with shaving cream dripping, and humbly sat in a waiting chair, while the big doctor got his haircut. As they left the shop, payment for the haircut was elaborately refused. The point, of course, is not so much one of respect for the medical profession, as respect for someone who had been chosen to attend a capo.