Related Topics

Favorites - II

More favorites. Under construction.

The Best Density for an Idea

|

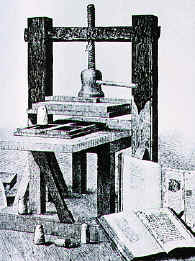

| Gutenberg |

Books were copied by hand before the invention of the printing press; every word counted. Quite often, that made the writing hard to grasp, too concise for comprehension by a normal reader at a single reading. An example would be Aristotle's comment on the nature of cities:

The partnership finally composed of several villages in the city-state; it has at last attained the limit of virtually complete self-sufficiency, and thus, while it comes into existence for the sake of life, it exists for the good life.... it is clear that the city-state is a natural growth, and that man is by nature a political animal, and a man that is by nature and not merely by fortune citiless is either low in the scale of humanity or above it.

Aristotle, Politics, I, i, 8-9, Translated by H. Rackham, and quoted by Sir Peter Hall.

Many modern readers glancing at this little paragraph would pass on to other concerns, confirmed in the conclusion that Aristotle is unreadable. A few who struggle through will see it is a collection of six epigrams. In the modern spirit of one-liners, they would be:

- A city is a collection of villages that, together, make a self-sufficient unit.

- A city grows because people are drawn there for economic reasons.

- City-dwellers don't return home because the city seems a more pleasant place to remain.

- People may come and go, but a city is destined to grow in size, on net balance.

- People innately prefer to live in clusters (politis).

- Those few people who don't like to live in a convivial cluster, are either boobs or saints.

Taking the trouble to tease his paragraph apart, one must acknowledge, Aristotle really has a lot to say about cities. By contrast, the author who quotes him on the frontispiece, Sir Peter Hall, uses eight hundred pages to make roughly the same arguments in Cities in Civilization. Although Sir Peter is a master of almost lyrical prose which touches on over 3000 literary citations, the six ideas are stretched too far on such a framework. Sir Peter controls his material and does not wander. The reader wanders.

It seems so terribly cruel to sound negative about a nice old gentleman, who must be an enormously entertaining person to share dinner with. And who has written a masterful prose poem about cities we all love. His book is well worth the price to buy, well worth the time to read. But it is overly long to support a half-dozen controversial ideas, just as Aristotle's seventy-five words are too few. The average reader will readily accept about two of the six propositions without elaboration, and will probably reject about two others in spite of all efforts to persuade.

When it comes to this sort of thing, the Economist, also written in Great Britain, has the most effective formula. Most of its pieces are written by one person and re-written by a second. After reading about a thousand such articles, the formula gets a little tiresome. But the density is nevertheless right for the modern reader. Three paragraphs for what Aristotle would accomplish in an epigram; ten pages for one really new, and difficult, idea.

Originally published: Tuesday, June 20, 2006; most-recently modified: Thursday, June 06, 2019