2 Volumes

Computers, Websites, and other Digital Gadgetry

What is novel today is old-hat tomorrow; but what is old-hat to someone today is still novel for someone else. These are our own thoughts about a variety of electronic novelties, for whoever finds them of interest.

The Age of the Philadelphia Computer

Computers have a long slow history. The computer industry, however, had an abrupt start and sudden decline, in Philadelphia.

Computers, Digital Cameras, and Cellphones

Much of the early development of the electronic computer took place in Philadelphia. We lost the lead, but it might return.

Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution

|

| Richard Arkwright |

The Industrial Revolution had a lot to do with manufacturing cotton cloth by religious dissenters in the neighborhood of Manchester, England in the Eighteenth Century. What needs more emphasis is the remarkable fact that Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution both originated about the same time, in about the same place. True, the industrializing transformation can be seen in England as early as 1650 and as late as 1880. The Industrial Revolution thus extended before Quakerism was even founded, as well as long after most Quakers had migrated to America. No Quaker names are much mentioned except perhaps for Barclay and Lloyd in banking and insurance, and Cadbury in candy. As far as local history in England's industrial midlands is concerned, the name mentioned most is Richard Arkwright, whose behavior, demeanor and beliefs were anything but Quaker.

He seems to have invented nothing, stealing the patents and ideas of others freely, while disgustingly boasting about his rise from rags to riches. Some would say his skill was in the organization, others would say he imposed an industrial dictatorship on a reluctant agricultural community. He grew rich by coercing orphans, convicts and others he obviously disdained into long, unpleasant, boring and unwelcome labor that largely benefited him, not them. In the course of his strivings, he probably forced Communism to be invented. It is no accident that Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto while in Manchester visiting his friend Friedrich Engels, representing reasonably well the probable attitudes of Arkwright's employees. What Arkwright recognized and focused on was that enormous profits could flow from bringing piecework weaving into factories where machines could do most of the work. Until his time, clothing was mostly made by piecework at home, with middlemen bringing it all together. The trick was to make clothing cheaper by making a lot of it, and making a bigger profit from a lot of small profits. Since the main problem was that peasants intensely disliked indoor confinement around dangerous machines, the industrial revolution in the eyes of Arkwright and his ilk translated into devising ways to tame such semi-wild animals into submission. For their own good.

|

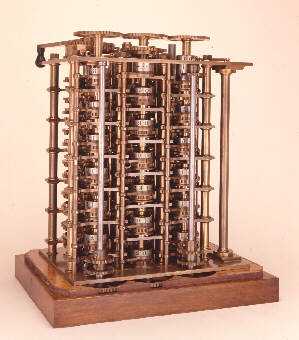

| Charles Babbage |

Distinctive among the numerous religious dissenters in the region, the Quakers taught that it was an enjoyable experience to sit indoors in quiet contemplation. Their children were taught to submit to it at an early age, and their elders frequently exclaimed that it was a blessing when everyone remained quiet, enjoying the silence. Out of the multitude of religious dissenters in the first half of the Seventeenth century, three main groups eventually emerged, the Quakers, the Presbyterians, and the Baptists. Only the Quakers taught that silence was productive and enjoyable; the Calvinist sects leaned toward the idea that sitting on hard English oak was good for the soul, training, and discipline was what kept 'em in line.

|

| babbagemaq.jpg |

The Quaker idea of fun through daydreaming was peculiarly suitable for the other important feature of the Industrial Revolution that Arkwright and his type were too money-centered to perceive. If workers in a factory were accustomed to sit for hours, thinking about their situation, someone among them was bound to imagine some small improvement to make life more bearable. If such a person was encouraged by example to stand up and announce his insight, eventually the better insights would be adopted for the benefit of all. Two centuries later, the Japanese would call this process one of continuous quality improvement from within the Virtuous Circle. In other cultures, academics now win professional esteem by discovering "win-win behavior", which displaces the zero-sum or win/lose route to success. The novel insight here was that it has become demonstrably possible to prosper without diminishing the prosperity of others. In addition, it was particularly fortunate that many Quaker inhabitants of the Manchester region happened to be watchmakers, or artisans of similar trades that easily evolved into the central facilitators of the new revolution -- becoming inventors, machine makers and engineers.

The power of this whole process was relentless, far from limited to cotton weaving. When Charles Babbage sufficiently contemplated the punched-cards carrying the simple instructions of the knitting machines, he made an intellectual leap to the underlying concept of the tabulating machine. Using what was later called IBM cards, he had the forerunner of the stored-program computer. There were plenty of Arkwrights getting rich in the meantime, and plenty of Marxists stirring up rebellion with the slogan that behind every great fortune is a great crime. But the quiet folk were steadily pushing ahead, relentlessly refining the industrial process through a belief in welcoming the suggestions of everyone.

Computer Adjectives

|

| ENIAC museum |

We are indebted to Paul W. Schaffer, the curator of the ENIAC museum, for the novel concept that much of the complexity of modern computers can be reduced to a few adjectives. Before we get to that, let's explain how "computing" was done before the University of Pennsylvania revolutionized it.

We once (1940-55) used calculating machines, which are sort of overgrown calculators. As big as baby grand pianos, bearing no resemblance at all to hand calculators which sit on top of desks, calculating machines were noisy as all get-out. A typical "calculating shop" used to contain eight or ten machines, each with a specialized function. Key-punch machines, usually several of them, put holes in cards to be fed into the machines. A couple of sorting machines, to count the holes in the cards and shuffle them into pockets for specified holes, specified by temporary wiring boards on the back of the machine. A collator, which was capable of more complicated sorting and sequencing. And the calculator itself, which was able to count various combinations of holes in cards, and even print out the calculations on very large rolls of paper tape with perforated holes along the edges. Five or six trained operators would move the piles of cards around, feeding them into the appropriate machines in a prescribed order. Sitting off in a corner was the super-operator, whose job it was to design the sequences of manipulation minute and string wires around a wiring board at the back of the machines. His were the brains of the calculating system, and the wires were strung around in accordance with his design. My recollection is that IBM refused to sell these machines, and a typical cluster rented for $1100 a month in 1955. The Pennsylvania Hospital was considered very advanced for having this arrangement as its billing system, but its primitive quality can be seen in the system architecture. The whole system revolved around the concept of producing a bill for every patient in the hospital, every day. If the patient went home, he was given the latest bill. If he remained another day, the old bill was discarded and a new updated one made. It was simple, it was clever, and please don't tell Jefferson. (On the other hand, something appears very wrong about all this progress that fifty years later, the same hospital with hundreds of computers, today cannot produce a hospital bill within a month of patient discharge.)

Well, back to adjectives. John Mauchly the mathematician came to the fundamental recognition that just about everything in mathematics and calculating could be done by "iteration", and re-iteration. Don't be afraid of the words. They only mean you take a small piece of arithmetic, and perform it over and over, millions of times. You really don't need to redesign new machines for each new process, since anything you might want to do could be done by reducing it to the same sort of iteration. So there's the first adjective: Mauchly's iterative design concept amounted to a "general purpose" computer. Many different patterns, perhaps, but all performed on the same machine, just as many different pieces of music are performed on the same piano.

|

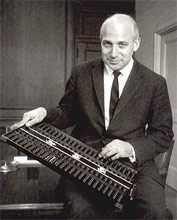

| John Presper Eckert, |

His graduate student, John Presper Eckert, eliminated the moving parts. Instead of metal hammers and prongs moving around, Eckert moved electrons. This step vastly increased the speed of the processing and even decreased effective maintenance. The early computers required a man to go around with a wheel-barrow, constantly replacing vacuum tubes as they burned out. But by moving electrons instead of mechanical parts, the iterative speed was so great that overall maintenance, per million calculations, was less. Eckert gave us the "electronic" computer. Together with Mauchly, the two ideas blended into the electronic, general purpose, computer.

|

| John von Neumann |

So then along came John von Neumann, observing this thing at work. Millions of punched cards were fed into the machine, but the holes in the cards represented data; the instructions were still wired in by physically connecting one contact to another, which had to be changed when the instructions changed. Von Neumann immediately saw how to get rid of half of this non-electronic effort. His contribution was to punch the instructions into program cards and feed them into the machine when the program instructions changed. So now, we had "stored instruction sets". As we still have today, the trio created the idea of a stored-instruction, general purpose, electronic computer, and actually made a working model of it. That's what promoted it ahead of the Mark I and other mechanical computers that had been developed in Europe. Vastly increased speed, vastly decreased costs -- and lots of big bucks for the manufacturer.

So, off to court, to sue for patent protection. Thousands of patents have been granted for various small innovations in the system, but who was entitled to claim ownership of the basic idea? Who invented the general purpose, electronic, stored-instruction calculator? Some puzzled judge finally worked his way out of that jig-saw puzzle by declaring that no one owned the right to have an overall patent. His reasoning was that since von Neumann had rushed to publish his work rather than rushing to the patent office first, it had become the property of the public and no longer belonged to the inventor. Compared with the contributions of a great many present computer billionaires, it really seems as though Mauchly, Eckert and von Neumann were conservatively entitled to a trillion dollars apiece. But life is not fair, and the law is an ass. Or is that so?

In later lawsuits, of which there were a great many, it came out that Mauchly and Eckert were employees of the University of Pennsylvania. They did what they were told to do and were paid for doing it. Maybe the University is entitled to trillions, thereby allowing them to pay their history professors better. But then, one final idea. The University accepted government money to do the job. Maybe all us citizens are entitled to trillions since we collectively commissioned and paid for this work. So, to recover, we seek out a class action lawyer. Standard procedure for class action lawyers is to take most of the money for themselves, sending each member of the class a share which is less than the postage required to send it.

The final outcome in this particular case was a suit between Honeywell (in Minneapolis) and Univac in Philadelphia. Univac essentially decided to go into the patent infringement business and Honeywell refused to pay royalties. Meanwhile, IBM engineers had been called as consultants for some rush job and reported to Mr. Watson that those people in Philadelphia had something really great. So, IBM paid several million to settle the patent infringement claim and started to mass-produce these things, with economic success everybody knows about. Meanwhile, the Honeywell/Univac case droned on and was eventually won by Honeywell when they produced a professor from Iowa who claimed he had the same ideas earlier. The computer concept was thus declared to be "prior art", preventing patent enforcement. By that time, IBM had such a long lead on the litigants, that the market was theirs, and IBM competitors just sort of dwindled away.

Computerizing Medical Care

Note: This article was written in 1999, long before Computerized Medical Insurance Exchanges were such a disaster:

|

| First Computer |

My first encounter with a computer was in 1958, and I have loved them ever since. As president of what called itself the Delaware Valley Hospital Computing Society, I remember giving a dinner speech concluding as follows: "If you want to be happy for a day, get drunk. If you want to be happy for a week, get married. But if you want to be happy for a lifetime, get a computer!" After fifty years, my affection continues. But to be candid, billions of dollars about to be spent on computers in medical care will mostly be wasted. Even worse, like malpractice suits computers will induce behavioral changes in the system costing far more than the directly visible costs.

That's unpopular news at present since the National Business Coalition for Health has launched a major lobbying campaign to persuade Congress to spend an initial billion dollars inducing physicians to maintain an electronic medical record. Various health insurance companies already provide financial incentives to doctors to file electronic claims forms, eventually threatening to reject any claim submitted on paper. The American College of Physicians has established a rather large department to develop programs for physicians to use in their practices; twenty years ago the University of Indiana started much the same thing. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia has spent close to a million dollars on such a project. It is reported that Microsoft Corp. has a massive project underway to supply electronic medical records. It sounds fairly easy to obtain large research grants from the government to devise something, anything, useful in this area. In my own case, training funds really weren't necessary, since I eagerly got into the field when everybody was a beginner. I was just as good a beginner as any other beginner. But let me repeat: the electronic medical record has been in the past and will be for decades, an expensive digression. In health care, creating more administrative work isn't the solution, it is the problem.

For fifty years the problem with an electronic medical record was that it took too much of the doctor's time to complete his part of the input, and then cost him too much to pay employees to do the rest. Presumably, automatic voice recognition and dictation will soon make it possible to record doctor's notes without handwriting or typing. Since, however, the elimination of current paper forms and check-off boxes will create a major problem in organizing the dictation verbiage, it could add five or ten additional years before programmers manage to rearrange dictation material and effectively integrate it into organized form, complete with laboratory results, dictated x-ray and EKG reports, even small images of the original material. Temperature, blood pressure, weight, photographs and the like can all be readily integrated into the stored electronic record, but to do so usefully is an expensive programming project. Doctors are quite right to be anxious they will lose control of the usefulness of their records in order to ease the task of programmers, speed up the sluggish pace of development, and reduce what will surely be an unexpected cost overrun. Storage and retrieval of such records is known to be an achievable but expensive task, which however also risks sacrificing the speed and ease requirements of the medical task it is supposed to serve -- in the name of cost-effectiveness.

Computers are no longer an unfamiliar tool; physicians have altogether too much experience with "vaporware", unrealized promises of convenience, and the damaging effect on the medical quality of the philosophy of Quick and Dirty. To respond to their resistance to design blunders with an accusation of undue conservatism is to provoke an icy stare and gritted teeth. Inevitably, the effective use of automation will require a redesign of workflow with major disintermediation of "gopher" staff; after all, that is how cost savings are to be achieved. That will provoke outcry that physician time is the most expensive component in the process, but unfortunately, physicians will discover Information Specialists with a business background will brush that argument aside. The most overpaid people on the face of the earth are investment bankers, but information consultants have persuaded business executives that inefficiency of the investment process is more expensive than even an investment banker's time. Having been through this themselves, insurance executives are unlikely to pay the slightest attention to physicians dancing to a familiar old tune.

For all that, data input is not the real problem; it's just the first problem. It's in a class with data storage and retrieval, which is expensive and cumbersome when you add a need for instant access and total privacy. But costs will come down steadily, and eventually, we can expect automated fingerprints or other biological identification, and cheap instant retrieval. Doctors will be able to make rounds in the hospital with a computer in their pocket, record telephone calls in their entirety, dial automatically and whatnot. There are problems with wireless transmission inside buildings with steel girders, and legal requirements for signatures on narcotic orders, but if we are determined, these problems can be overcome as easily as they were with electronic check writing and stock brokerage. Cost may top twenty billion dollars in twenty years, but it all can be done if we insist.

But then you encounter the real problem. Information will accumulate in these records in staggering amounts. Even if you resolutely resist demands to have the nurses record every groan, and the orderlies file every laundry slip, the legitimately important medical information will be exposed as the massive heap of transients that they really are. Plaintiff lawyers will insist no scrap of data may be deleted, hospital administrators will insist on compliance, when in fact most of a doctor's concentrated effort is devoted to brushing aside momentarily distracting data in order to see what's going on and react to it instantly. When a quick look doesn't solve the problem, the doctor goes back for additional data. If you disrupt these skills and traditions of coping with information overload, evolved over centuries, you will at best impose frustrating delays on a complex system under pressure, and ultimately inspire elaborate systems of short-cuts. The Armed Forces are famous for paperwork, but even they know better than to ask a pilot for his Social Security number as he starts a bombing run. The hospital nursing profession has already just about collapsed under paperwork pressure. If you see five nurses in a hospital, three of them will be sitting down writing something. The terrible truth is that no one reads it, no one checks it, and ultimately it sits in the record room waiting for a plaintiff lawyer with unlimited time to sieve out some misrecorded misconception or uninformed conclusion. My faith in the computer is such that I feel sure that methods can be devised to produce periodic summaries, automatic alarm signals, and mostly effective prioritization of data elements. Unfortunately, medical care is changing at such a rapid rate that ad hoc automation of physician thought processes cannot keep up with the current pace of change in medical progress. You would think some things would be unthinkable, but since I can remember the organized campaign to suppress the CAT scan as an unnecessary expense, I confidently predict that programmer inability to keep up with some advance in medical care will at times lead to organized outcry that we should slow down the pace of improving medical care, so that computer clerks can keep up with it. But that is only a small part of the issue, which at its center is that physician time will be dissipated and his attention distracted by presenting him with unwieldy amounts of neatly printed, spell-checked, encrypted and de-encrypted, biometrically secure, hierarchically prioritized -- avalanches of data which are irrelevant to the issues of the moment. The goal is not, after all, an electronic record. The local goal is to decrease the cost of medical care by increasing the productivity of the physician, and the overarching goal is high-quality patient care at a reasonable price. Behind all that, since the impetus comes from NBCOH -- the ones paying the insurance premiums -- suggests that the local goal is not so much the improvement of care as oversight reassurance that cares provided has been as good and as cheap as possible. The goal is legitimate, but this cybernation approach looks to be self-defeating by being overly specific.

If the reader has the patience for it, let me now cite a historical example of the third-party tail wagging the medical dog. In this case, third-party health insurance similarly overextended its reach by imposing internal health system changes, trying to facilitate the role of monitoring it externally. Specifically, the system of diagnostic code numbers was changed from one devised by the medical profession for its purposes, into a different coding system devised outside medial profession sponsorship, which seemed to suit the needs of payment agencies better even though it suited medical purposes less. After twenty-five years, it is now clear that third-party payers have shot themselves in the foot on this matter, and everyone is worse off. The topic, please pardon the obscurity, is the diagnostic coding system.

To go back to beginnings, the American Medical Association perceived a need for a diagnostic coding system in the 1920s. Organizing or even merely indexing vast amounts of information about a disease required more specificity than freestyle verbal nomenclature could provide. Quite a distinguished panel of specialists and consultants then produced the Standard Nomenclature of Diseases (SNODO) which in time became the Standard Nomenclature of Diseases and Operations. In order to reduce ambiguity, this system developed a branching-tree code design for anatomy, linked to a branching-tree for causes of disease, ultimately linkable to a branching tree of procedures. These three sets of three-digit codes linked the components together with hyphens (000-000-000). The first digit of each was the most general, as in Digestive, Musculo-skeletal, etc. and subsequent digits were progressively more specific and detailed, as in "Digestive, large intestine, sigmoid colon". The causes of disease would resemble "Infections, bacterial, streptococcal". An example of Procedures would be "Incision, incision, and drainage, drainage and insertion of the drain". In nine digits, it was thus possible to represent " incision, drainage, and insertion of a drain into a streptococcal infection of the sigmoid colon". After a while, the codes grew from three to five and six digits, again repeated three times, so an immensely detailed, unambiguous description might be coded in fifteen digits by a physician who knew the rules but didn't own a codebook. This code was ultimately taken over by the Academy of Pathology, expanded and is called SNAP. The pathologists absolutely refused to give it up.

The rest of the profession gradually yielded to the pressure of hospital administration, who was pressured by the Association of Medical Record Librarians, responding to the views of outside statistical interests, particularly insurance. A simpler, shorter coding system was needed, they felt, concentrating on the thousand most common diseases. The International Classification of Diseases was produced, reducing the millions of SNODO diagnoses to 999 by heavy use of several varieties of "Miscellaneous" or "Not Otherwise Classifiable (NOC)". Since the goal was to count the incidence of common diseases, the coding system was stripped of any logical tree-branching and became a short list of what was most common, starting with 1 and going to 999. In time, of course, the common-ness of conditions changed, and various complaints from various directions forced the ICD to go to 4 digits, then five. Unanticipated conditions or complications eventually required the patchwork of some alpha "modifiers", and the original short hodge-podge became a long and bewildering hodge-podge. Coding accuracy declined markedly, but ho-hum. The health insurance companies paid the bill, no matter what the code said. At another place, we will discuss the entertaining way that Ross Perot became a billionaire out of the computer chaos of Blue Cross and Medicare at this time, but right now the central theme to follow is DRG, Diagnosis Related Groups. Try to follow, please.

By 1980, Medicare was fifteen years old. It was clear that certain things just had to be changed because the excuse that the system was new and untried was beginning to wear thin. The early designers of the system based their payments on auditing a hospital's yearly costs, auditing the proportion of patients who were Medicare beneficiaries, and paying a proportionate share. That was easy and reasonably accurate, but it had a rather significant flaw that it took no account of whether the patients needed to be in the hospital in the first place. Or whether they needed to stay so long. The response they adopted (in the Budget Reconciliation Act of 1983) is a measure of just how desperate they must have felt. Knowing full well how inaccurate the ICD coding system was in practice, it was all there was. Consultants, particularly at Yale, ran computer simulations of various subsets of ICD codes to find a formula that would produce approximately the same hospital payments as the system of cost reimbursement. If memory serves, the original formula was to divide the thousand ICD codes into 27 diagnosis-related groups (DRG). Eventually, the process was tweaked to seventy or eighty groups. Walter McNerny, then Past President of the American Hospital Association told Congress hospitals could live with this system, and promptly we had a system for paying out hundreds of millions of dollars. It was touted as a highly sophisticated advance in the arcane science of hospital reimbursement, so it must have included a lot of deliberate overpayment. I can remember trying to remonstrate with McNerny, who felt he didn't have time for the discussion. Physicians had very little to do with the DRG portion of the 1983 Medicare Amendments because the AMA had long insisted that physicians and hospitals go their separate ways on reimbursement. Russell Roth, who was president of the AMA at the time, recounted many times the episode in the Oval Office, when it was announced to Lyndon Johnson that Dwight D. Eisenhower"was in the next room waiting for him. LBJ excused himself to leave, and on the way out said to Wilbur Cohen, "Give him anything he wants." Things were destined to change, but at least for a very long time, physician and hospital reimbursements were strictly independent.

The Wedding of Computers and Medicine: First Annual Fuller G. Sherman Lecture George Ross. Fisher, M.D.

The Wedding of Computers and Medicine:

First Annual Fuller G. Sherman Lecture

George Ross. Fisher, M.D.

October 1, 1987

Fuller G. Sherman, M.D. was born August 15, 1894, graduated with academic distinction from Jefferson Medical College in the class of 19** with his second doctorate degree, was certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine, practiced for many years in Woodbury New Jersey, and retired from practice in 19** to live in his native state of Maine.

The competitive strengths of Dr. Sherman’s character have actually been easier to see during the so-far thirty years of his retirement from medicine. Past the age of 90, he attended Bowdoin College, taking courses in Shakespeare and geology, plays par golf, holds a Masters’ certificate in tournament bridge, is a distinguished cabinet maker, and does creditable work in oil painting. Two notable achievements were once, on the day after his graduation, to have flattened an Associate Dean of this Medical School with a single punch; and secondly to have consistently outperformed the Dow Jones Industrial Average on the New York Stock Exchange. Because of the latter, of course, he was able to endow the lectureship we inaugurate today. In both of these adventures, he illustrated the truism that in life, everything is a matter of timing.

He has been my teacher, employer, referring physician, and friend. He is now my patient, allowing me to judge he has as good a chance as any of us to live another thirteen years. If he does, he will have the almost unheard-of opportunity to observe the practice of medicine in three different centuries. There can be little doubt he will study the next century harder than any of us, as his patronage of computer science demonstrates today.

My subject has three parts: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The exhilarating nature of the computer world lies in only a little yesterday, a little of today, and a great deal of tomorrow. For our purposes, yesterday began about thirty-five years ago when the Chairman of the International Business Machines Corporation, Thomas Watson, made the decision to gamble the whole future of his successful typewriter and tabular company on mass-producing computers. There were then only a few dozen of those machines in existence, mostly owned by the military. They cost millions and were expensive to operate. Typically, a bushel of worn-out vacuum tubes were replaced every day. You could walk around inside them without stooping over. By 1960, IBM was selling a thousand of these machines a month to large corporations for about $ 4 million apiece. Technology in 1960 had greatly reduced the maintenance cost, but the University of Pennsylvania still had to rent them for $300 an hour at the academic rate. Machines of equal power can today be purchased for a thousand dollars, and are the size of typewriters. I own five of them; there are about twelve million others in existence, up from nine million last year. One surgeon recently told me he bought one of the best, about a year ago, but had not yet had time to take it out of the box. The cost of these miraculous machines was thus trivialized in a single generation, and each year the Sunday supplements have promised us that within two years, five at most, such things as a medical diagnosis would be relegated to computers. It never happened, of course, because science fiction writers had not heard Dr. Sherman’s professor Thomas McCrea (Dr. Maddrey’s predecessor by seven) repeatedly intone that “most diagnoses are missed because the doctor didn’t look not because he didn’t knowâ€. The problem of diagnosis today, as then, is one of information gathering, not information manipulation.

A generalization can be offered. If you hear a prediction about computers, be fairly certain it will never happen, unless it already exists. So many brilliant minds are at work, with financial rewards providing unlimited resources, that the immediately achievable is achieved immediately. Mr. William Gates, a self-made billionaire at the age of 31, illustrates how among people who are successful in this field, there is no motivation for idle chatter.

The amazing drop in the cost of computers has made it possible to have a personal computer that is those dedicated to use by a single person. Personal, or stand-alone computers, can now do almost everything a large main-frame computer can do except cope with multitudes of users. But, having only a single master, they cater solely to his needs and undergo an unexpected transformation into tools not appropriate to big shared machines, becoming extensions of one user’s brain. Word-processors and spreadsheets transform the way we think and work; such generalized mind-expenders prove to be more powerful than programs which merely calculate acid-based balance or remind us of potential adverse drug interactions.

Word processing is a utility as revolutionary as Guttenberg’s invention of movable type; it can be expected to raise the standards of thought just as much as the standard of typing. A program costing less than $200 permits preliminary display on the cathode ray tube, where prose can be corrected and modified repeatedly before it is printed on paper. The machine will find all spelling errors and most grammatical errors, permit any character, paragraph or page to be replaced, repositioned or erased. It will index the material, automatically insert hyphens place footnotes and references in place, and allow unlimited experimentation with different margins, page size or paragraphing. When finally printed on paper, the right margin can be automatically justified, and the words become unified into important than these aesthetic advantages, word processing permits the author to revise repeatedly until what he writes finally says what he means.

A second innovative creation on a personal computer is a hybrid of two steps, the generalized data management system, and the spreadsheet. Many small stored globlets of information are aggregated on request, meaningful. If the unit of data is a single patient, with blue eyes can then be effortlessly linked with any other glob of information, such as antibodies to retroviruses. The spreadsheet concept then organizes such data cells into rows and columns which can be fed into formulas which operate serially on every row in a column, generating a new column of derivatives. The user need not, in fact commonly does not know statistical theory, but for example, can process anyway to command regression analysis on eye color and AIDS or any more plausible hypothesis in clinical research. These programs will then transform selected numbers into colored graphs on request (slide). The ability to use statistical tools without understanding them will, of course, create abuses of this system, which in the case of regression analysis would be to overemphasize the validity of 95% confidence limits. Ultimately, the value of the computer product will depend on the brainpower of the individual user. When convincingly packaged data can be processed in massive amounts by chimpanzees at the keyboard of $1000 machines, it is a little daunting to await the misinformation which will be generated by the 5% error content of mountains of data. By the rules of regression analysis, one conclusion in twenty will be reached by the operation of chance alone. Since editors are intrigued by papers which reach unexpected conclusions, thoroughly documented spreadsheets research which later turns into smoke will someday be their proper torment. The exciting future of computers is thus not to replace doctors in some profession-threatening way, but rather to extend the capabilities of their minds in powerful ways which continue to reflect the personality of the user. As has been said of corporations, the dedicated personal computer projects the lengthened shadows of the man.

Early steps in that direction would please Adam Smith, producing exalted results from trivial and mercenary motivations. Whether you like it or not, and whether cost-effective or not, the of medical practice with insurance and reimbursement is making it essential for every practicing physician to employ a computer; those who avoid it have done so out of fear of the disruptions, not because they deny the value of the office machine. Once the machine is installed, word processing is seen as a free bonus, and the financial affairs of the practice become raw materials for database program and spreadsheets. In this way, the practicing physician acquires a mind-expander when he merely sought to reduce his clerical expenses. He also, by way, merges into the mainstream of business computing, and like everyone else, will find that the new IBM model 50 has become the modern standard, just as the IBM Selectric typewriter became the business standard thirty years earlier.

To understand why this is so, notice that IBM continuously spends $5-6 billion annually on research but withholds most new products from the market. Then, about every seven years, a bundled package of innovations is released as a “new generation†which then makes existing machines obsolete and dominates the field for the next seven years. Throughout the seven-year gestational period, other companies also bring forward innovations but must recover their costs by releasing them immediately. IBM watches market reactions, preparing to submerge would-be pioneers in a tidal wave of releases. In effect, other companies test the market for IBM to exploit. Almost every component of the 1987 new generation is new and very little of it is unique to IBM (slide). However, an irresistible market standard is created when many innovations are released at once by the largest volume producer. The new 1987 machines seem mainly designed to permit for the first time several personal computer users to share one octopus machine, a mildly useful thing for the doctor and his secretaries. The main importance of using 32-bit technology lies in the fact that the doctor’s personal computer uses the same system and thus can talk the same language as the mainframes in hospitals, laboratories, insurance companies, and the Internal Revenue Service. The profession must not let itself get lost in the chatter of intercomputer communications; while he must adapt to the equipment that is available, the physician mostly needs many different mind-expanding applications on a single machine. The creation of a market standard will almost surely prove to be a dominant force even for physicians. The IBM model 50 will be what to buy until 1993, as will IBM stock, but physicians need to establish their own culture within the commercially available environment.

1993 will not, of course, be a far enough horizon for Dr. Sherman’s third century, so we might look across the valley over two intervening mountains. Fourteen years from now, the new 2001 models will also be composed of standardized refinements of whatever exciting advances may accumulate in the meantime. By that time, computers should be able to accept voice dictation since they can already understand a spoken vocabulary of about 1000 words. Computer scanners can now read pages of typing with 90% accuracy, so we can except much less typing for accession of much larger volumes of day-to-day information. I understand x-ray films require a resolution of 2000 by 1600 pixels; since advanced computer screens already achieve 1600 by 1200 pixels, the silver-coated films we use now should likely disappear.

In the shorter term, it would be a fair prediction that the exciting programs of the next seven years coming up will exploit the telecommunication power of 32-bit processing and the vast storage capacity of CD ROM’s. Large Multimillion dollar mainframe computers operate in units of 32, but personal computers now mostly use units of 16. Declining prices of transistor chips make 32-bit technology affordable for personal computers, so we can expect to see the doctor’s computer talking on equal terms with the big computer in the hospital, the drug store, and the Library of Medicine. It is exciting to predict role reversal, with once imperious mainframe owners outmaneuvered by users of agile PCs. Organizational whales like hospitals, department stores, banks, and the Internal Revenue Service have had their day of forcing everyone else to conform to their convenience; the little piranha fish will grow sharp teeth.

Since the profession of Medicine is after all in the knowledge business, it is breathtaking to contemplate the migration of medical journals and libraries from paper to electronic medium and the dissemination of libraries to the doctor’s consultation room. Compact disc technology is already the cheapest form of information storage, whose inevitable price decline has scarcely begun (slide). Grolier’s encyclopedia is now available on a plastic disc you could put in your shirt pocket; the entire encyclopedia only takes up 20% of the disc. This unerasable form of storage is sometimes called WORM (write once, read many). Inexpensive scanners can convert pages of print to a computer file in 20 seconds; rather accurate programs can convert foreign language to pidgin English. Between the two processes, whose only present limitation is price, whole libraries will surely soon be swallowed up on plastic disc, and medical journals may appear in that form as soon as someone figures out how to incorporate drug advertising. However, don’t run out and buy a CD-ROM just yet; there are twenty different types and they are incompatible with each other. The exasperating power of IBM is well illustrated by the fact that this titanic information storage revolution will not take a step forward until someone like IBM is able to impose a standard which will disciple the present Tower of Babel.

In closing, the point must be made that the main hindrances to adoption of computers by the medical profession will not be technical, they will be sociological. “Not in my back yard†is the Spirit with which most new things are greeted, even in the learned professions. A plain fact of human behavior is that how you stand is determined by where you sit. For years, banks have transferred patient payments to physician bank accounts without the creation of a single piece of paper. But electronic funds transfer has made very limited progress in 20 years, primarily because the payers and their banks do not wish to surrender the interest float which develops during the delay of transfer. Blue Shield of Pennsylvania has over a million floating dollars earn interest at all times while the obsolete paper check depositing process limps on. The videotape machines which are everywhere provide a warning example of how technical potential is easily frustrated. Instead of ten thousand college professors giving mediocre lectures on Hamlet, it is clear that some professor at Oxford could give the very best lecture on videotape which all students everywhere could watch at home without even paying tuition. Since it hasn’t happened, and it won’t happen, perhaps the point I am striving to make becomes clear.

Try to image the resistance which pharmacists would create to electronic drug ordering; indeed, the nursing profession is very resistant to physician orders which come in any way except handwriting on the floor chart. While I cannot identify the economic incentive which explains the delay, Jefferson Hospital has just installed a system in which laboratory results are instantaneously transmitted to the clinical floors. However, a similar system was installed at the old Philadelphia General Hospital in 1965. These and many other examples of apparently irrational delays most likely have their explanations in the motivation of people rather than the limitations of machines. Therefore, in predicting a revolution in medical information handling we must not, for example, underestimate the capability of printers and typesetters at the New England Journal of Medicine to hold up electronic publishing, or the librarians of the world to resist the destruction of their careers by plastic disks. IBM is in the business of setting bridal supplies and has repeatedly proved to be a shrewd judge of bride psychology. They obviously believe 1993 will be soon enough for the real wedding of medicine and computers; maybe it can wait for the year 2000. Meanwhile, it will not matter much that the bride’s father can easily afford the wedding, or the groom is anxious to perform. Medicine, the bride-to-be, hasn’t yet said “yesâ€.

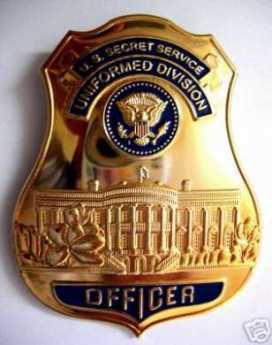

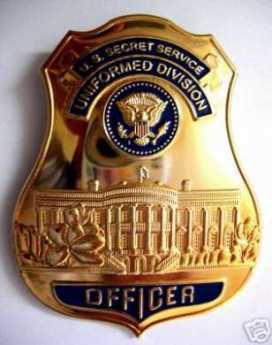

Report Identity Theft to the Secret Service

The Internet provides new blessings, but new problems as well. Identity theft has now ballooned from a rarity to a fairly serious issue. After initial turf confusion, the issue has been assigned to the U.S. Secret Service. If it happens to you, that's where you make your anguished call. (1-877-ID-THEFT) or www.consumer.gov/idtheft

There's a certain logic to regarding identity theft as a modern form of counterfeiting, which has been with us since the days of William Penn. Shirley Vaias, representing the Philadelphia regional Secret Service, recently addressed The Right Angle Club of Philadelphia on the topic. It makes sense to learn the Service is headquartered on Independence Mall, across from the Mint. The crude forms of printing in the 18th Century made counterfeiting easy, and ever since the early days, there's been a race between improvements in technology and improvement in counterfeiting. We now have a paper with little red fibers in it, watermarks, serial numbers, color-shifting inks, microprinting of secret messages in the portraits, special magnetic strips, and probably lots of other clever things we aren't told about. The Bureau of Printing and Engraving is changing the currency, one bill at a time, and recently there was a new ten-dollar bill. A counterfeit version was in circulation within six hours.

ATM machines are equipped with counterfeit-recognition devices, and special gadgets are provided for banks and retail stores, but one detection device traditionally catches most fake bills. After handling huge amounts of currency, bank tellers catch a counterfeit just by the feel of the paper. Color photocopiers are getting better and cheaper, but of course, they can't change the serial numbers, so they aren't as smart as they seem. About one-hundredth of one percent of the currency in circulation appears to be fake, so you are pretty safe, but the possessor of a bad bill is deemed to be the one out of luck. The consequence is that many citizens suspect a bad bill, take it to a bank and have it instantly confiscated without recourse. That would seem to discourage reporting a counterfeit, encourage passing it off to an unsuspecting friend, and overall seems terribly unfair; but it results from the wisdom of the ages. Experience shows honest citizens are indeed tempted to try to pass the money on. While the banks don't enjoy being policemen, the effect is that counterfeits will circulate until they hit a bank, and thus confiscation is fairly comprehensive.

As the printing of money gets more complicated, the special presses needed to produce good money has become a monopoly of certain German companies, who sell the machines to other countries. Some of the American presses thus got into the hands of some Russians, who sold them to the North Koreans. So for a while at least, the North Korean government was printing American currency. It provoked vigorous countermeasures, the nature of which is confidential.

A bill of any denomination costs the government about half a cent to produce and lasts about four years in circulation. When tons of old bills are retired from circulation, the serial numbers are recycled; to an outsider, that sounds like an impossibly tedious job, but they say they do it. There's also the issue of seignorage, a term for the profit the government makes when the paper currency gets destroyed in one way or another, costing less than a cent to replace. Just how profitable the currency business is, cannot be accurately determined, because a lot of it is buried or hidden in mattresses and might someday resurface. But there is a substantial profit, which like any shrewd businessman, the government weighs against the cost of detection. Bail bonds and casinos are big sources of bad money, as could be readily imagined, and hence it is in their interest to get pretty sophisticated (and extremely unpleasant) about detection. On balance, however, it can be expected that legalized gambling in Philadelphia will promote more counterfeiting in the local economy, and hence is an offsetting cost of the tax revenue.

Over the centuries, governments have learned how to cope with counterfeiting, and there is actually much less of it than a century ago. You win some and you lose some; life just goes on. With internet identity theft, however, the criminals are developing techniques faster than governments have learned to combat them, and it is governments who struggle to catch up. Unfortunately, everybody takes a business-like approach to the matter, asking whether the precautions cost more or less than the losses. It would seem that if money continues its migration from paper currency to bookkeeping entries, it will eventually seem unsatisfactory for only one party in a transaction, a bank let us say, to keep the books while the public simply trusts them. Eventually, each individual will be forced to seek the protection of some sort of computerized system keeping the counter-parties honest, on behalf of the public, and to prevent a paralysis of commerce. Identity theft is getting expensive enough to warrant the effort.

Just how to do all that is not too clear. So, in the meantime, just let the Secret Service figure it out.

The Beginnings of E-Mail

|

| J.P. Morgan |

Dan Rottenberg, who wrote an outstanding book about Anthony Drexel called The Man who Made Wall Street, had access to many private papers that had to be omitted from that book because of space limitations. He tells an interesting tale about telegrams between Drexel and his bulbous-nosed protege at the New York office, J.P. Morgan.

Around 1880, Morgan put AT & T together, but before the telephone came into being, most high-speed communication was by telegraph. Naturally, Drexel and Morgan could afford to have a private telegraph line going between them. It would have been a bit much for them to use Morse Code themselves, so the scraps of conversation were written down and some have been preserved.

Spam, of course. If you want to avoid hackers, intruders, and unwanted advertisements, then as now, you have to be a zillionaire. Since, however, Morgan's private library on Madison Avenue had lots and lots of pornography hidden away, it does almost boggle the mind to imagine what might have been accomplished with a telegraphic wire tap.

Philadelphia Calendars

|

| conductor |

As life becomes more cluttered, its time to keep track of what is important. Here is our approach.

We're trying something new; let's explain it. You can learn when you can hear this magnificent orchestra from our calendar.

Look down the left column of the home page of Philadelphia Reflections, and click on a box called "Philadelphia Calendars." (It's about the 12th one down). In time, the screen will display a list of group activities, like Music, or Sports, or Computer Discussion Groups, or whatever. Clicking one will display a list of activities. If there are enough activities, we may have to go to the third row of choices.

At the moment, we start with the Philadelphia Orchestra concerts. Click that choice, and you get a year's calendar, marked with what is presently known about the schedule. If you wish, you can drag the calendar to your desktop, dropping it there. In the URL box, there's usually a tiny icon to the left of the text. (It's meant for dragging purposes and called a Favorite-Icon, or FaviconThe Kimmel Center.

So, if you want to know what's at the Kimmel Center for some date, what time it starts, or who the soloist is, you can find it in this nook of Philadelphia Reflections. Frequent fliers in the music world can even have their own calendar on their own website, by dragging the Favicon. We hope to attract many such calendars, and it would be just fine to have local field hockey schedules, local poetry readings, etc. Just so it's located from Trenton to lower Delaware, the area once known as the Quaker colonies, now called the Philadelphia region. Why not just print it out? You can do this, but you lose any last-minute updates provided by the calendar creator, and that's one of the great features of Internet communication.).

To pull this off, several components must be assembled:

1. The calendar creator, the secretary, or executive office of the sponsoring organization, must either have iCal (free for Apple users), Outlook (about $100 for PC users and at a 60% discount at some online stores), or the Mozilla calendar available for both Macintosh and PCs. Users, however, only need normal Internet access. If you create one, you are responsible for the accuracy of the calendar.

2. The calendar server is a computer that holds the master copy of the calendar, and it really should be running night and day, every day. Both iCal and Outlook can make such an arrangement. The server can be anywhere in the world.

3. The calendar clearing house, Philadelphia Reflections, in this case, offers a defined selection from the millions of potential calendars in the world. Our selection merely claims to be local to Philadelphia, nothing more.

4. The end-user. Just what the user does with the information is rapidly evolving. The software is changing, getting more convenient every day. We'll comment from time to time, passing on suggestions as clever folks perfect them.

Oh, yes, one more thing. If you want to post a calendar with us, click the button on the front page, called "Contact us." It's a self-addressed e-mail. Rate this "Reflection" Printer-Friendly Format E-mail to a Friend

Money Bags

This little morality tale was told to me by two unrelated sources, one of whom was a staff aide to Wilbur Cohen, the author of the Medicare law. And the other was a high official of Pennsylvania Blue Shield, the appointed administrative agent for Medicare in Pennsylvania. Its relevance to the more recent SNAFU with Insurance Exchanges introducing the world to Obamacare should be fairly obvious.

After Lyndon Johnson rammed the Medicare amendment to the Social Security Act through Congress in 1965, he wasn't shy about drawing attention to it. The press was present in great numbers, with staff officials who had a role in crafting the document, members of Congress, and anyone else who was standing around. The legislation was laid before him and signed with twenty different pens to be presented as mementos to the in-group. Each pen was only used to inscribe about half of one letter of his name, so it was a slow but joyful process. As intended, it got lots and lots of publicity.

> >

|

| H. Ross Perot |

So, thousands of thankful old folks saw the ceremony on television, though they heard that the law was in effect immediately, and proceeded to dump their medical bills into a shoe box, sending them to Medicare to be paid. Unfortunately, Medicare didn't have an office, a staff, or even a telephone number. These things take time. As fast as they could, the Medicare staff constructed a system of carriers and intermediaries, carriers for part A, and intermediaries for part B. And almost without exception, appointed the local Blue Cross and Blue Shield organizations to be the carriers and intermediaries. Consequently, the organization of Medicare was patterned closely after the organization of the two administrative corporations. Meanwhile, the bills from old folks just kept pouring in through the postal service. It was about all the staff in Washington could do, just to direct the mail out to the local intermediaries and at least get it out of their hair.

Less than a year later, that's how the claims manage to Camp Hill, PA, a little suburban town near Harrisburg. In desperation, Blue Shield had rented a local vacant supermarket and piled the mailbags ten feet high. There were quite a few telephone calls of inquiry, and the old folks were politely told the matter was being looked into. It was beginning to look as though one supermarket wasn't big enough.

Computers were, of course, rented from IBM, who had a policy of renting, not selling, its valuable equipment. Keypunch operators, computer operators were hired, air conditioning was installed, and one team after another of computer programmers was hired -- and fired. Consultants were called, scratched their heads, sent big consultation bills, and turned sadly away. Sorry, but somehow it just doesn't work.

So that's how it happened that one Friday afternoon, a vice-president of Texas Blue Cross named H. Ross Perot came in, accompanied by a fellow with glasses so thick they looked like the bottom of Coca Cola bottles. So far as anyone can remember, the guy with coke-bottle glasses never said one word. The desperate, hopeless mess was explained to Perot, whose salary at that time was rumored to be twenty-five thousand dollars a year, about right for a Blue Cross executive. His background as a kindred Blue Cross person inspired confidence, and the conversation rambled on for an hour or so. Meanwhile, the guy with coke bottles went over to the Penn-Harris Hotel across the street and got to work. By the end of the weekend, he had come back a couple of times, but eventually, would you believe, it really, well it really worked. Contracts were quickly signed, the wheels began to turn, the mailbags in the supermarket began to march through the processing cycle. Blue Shield, the Medicare program, the finances of the nation's elderly, and Lyndon Johnson's reputation -- were all rescued.

As everyone now knows, the Medicare processing contracts made Ross Perot into a billionaire, living on Bermuda in the lap of luxury, eventually upsetting the re-election hopes of George Bush, senior by running for President himself on a third party ticket that had something or other to do with giant sucking sounds. A Congressional investigating committee looked into the outrageous profits Perot had extracted from his homeland's elderly, volleyed and thundered. Whether Perot actually thumbed his nose at them is doubtful, but he certainly was in a position to do so.

Meanwhile, whatever happened to that guy with the coke bottle glasses, no one seems to know.

Intelligensia, Philly Style

|

| Mac Bus |

On a hot summer evening, attendance at computer user-group meetings is light, so after a recent one got through discussing spammers and new software, we adjourned to the sidewalk tables of a nearby pizza joint, just off Broad Street. United only by a common interest in computer hardware, software, and techniques, this one comes from many corners of the Philadelphia social scene and goes back to those corners after the meeting. Whatever their background, computer geeks are uniformly good at math. But on this particular evening, the conversation turned to medical experiences.

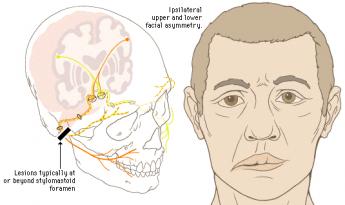

A middle-aged man with a ponytail related he had recently experienced Bell's Palsy, a paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face. The group was fascinated to hear how saliva dripped from a corner of his mouth, and his unclosable eye dried out and got sore. His doctor told him there was not much to do except wait, an opinion confirmed by a specialist. Immediately, this man who makes his living programming computers set out to find the best acupuncture person he could find. It was a familiar story, and I remained as quiet as I could while he essentially related that when the regular medical profession confesses failure, the patient feels released to take matters into his own hands. His instincts were to do something, anything, even if that something was plainly futile. He could not bear the idea of doing anything, and sure enough, in time he got better.

|

| Bell's Palsy |

I said nothing because it was a familiar reaction to conditions that either would or would not get better by themselves. The more serious studious members of our little club were quiet, too, because their instincts were to do what they were told, and in his place wouldn't have acted the same way, didn't completely approve. In a moment, a large muscular man took up the medical subject by telling that he had spent two years in a hospital after falling down an 18-story elevator shaft. Man, oh man, it seemed like it took two weeks as I was going down, and when I hit I wasn't knocked out. He had landed on one buttock and his leg was nearly wrenched off, but he remained awake, not bleeding much. Within minutes, he was headed for an operating room and reached out to grab the clipboard from the nurse. On it was written "amputation", which he circled, wrote "No amputation!!", dated and signed it. No way were they going to cut off his leg. His leg was in fact saved; he now scarcely walks with a limp. Then another computer nerd chimed in.

|

| Motorcycle Jump |

This man's story was that he spent fifteen months in a hospital after a motorcycle accident. He somersaulted seven times through the air before he landed on his chest, and twenty years later he could still remember every single twist of all seven turns. He, too, related many hospital disputes about morphine injections and contemplated surgeries. Both men related dubious experiences with young interns and medical students, and numerous proposed remedies that had been rejected. All three of these medical veterans expressed violent hatred of HMOs, for reasons unspecified. I was quiet; no argument from me. This motorcyclist eventually had his vehicle repaired and proceeded to ride it for six more months until he sold the machine. So there.

We all had different thoughts about this, I suppose. I was lost in thought about why they had survived and imagined that not being knocked unconscious meant that they had not hit their heads. Heavily muscled men like this were probably cushioned by their muscles; a skinny little bony nerd would have been much more smashed up. The negative side of that protection came out in hearing them both describe their heart problems, with by-pass surgery and whatnot later on in life. That's probably the negative side of their muscularity. Neither man smoked, but I bet they both did at one time.

As we strolled home from the pizza joint, it occurred to someone that the national political conventions were on television that evening. The women were fighting with the blacks. The studious nerds were silent; the wild men merely grunted. That didn't seem like something to fight about, or even to comment on.

As I walked into the darkness, I wondered if such a conversation would seem normal in any other city in the world.

Making Money (8): Virtual Money

When money was tangible you had to guard it, now that it's mostly virtual you have to verify it. Hardly anybody can, and that's a problem.

|

When money and wealth were wampums, precious metals, and paper currency, these physical objects required physical protection. It was all a big nuisance, with six-guns on the belt, bank vaults, and appraisers of one sort or another. But now that wealth is merely a bookkeeping entry on someone's computer, things may be even more nuisance because verification is almost beyond us. Counterfeiting of the computer variety must be left to institutions to detect or deflect, causing them to introduce firewalls of various sorts that also block legitimate inspection by customers. "Trust but verify" doesn't work so well in this environment. Let's use a personal example, slightly fictionalized to protect the innocent.

Several software products now exist to download transaction information automatically from various institutional sources to a customer's home computer; they are either free or cost a nominal amount, and are quite "user-friendly". In my case, however, the reports they generated were quite significantly at variance from the monthly reports which were issued directly by my counterparties. Dear Sirs, Please explain.

What I soon discovered was that everyone blamed someone else, and everyone blamed me for bothering them. Quite obviously, I had little understanding of these specialized accounting niceties, and quite obviously I had too much spare time on my hands. Telephone help desks, often located in India, will not give out telephone numbers for incoming calls and are programmed to check the size of your account before placing you in a call-back queue. The first call is usually taken by a trainee whose job it is to screen out the silliest sort of help request, and then to refer to a supervisor if things rise in complexity. Supervisors have supervisors. That's if you are lucky. More commonly, the tedious software business has been farmed out to a vendor, and the contracting agency has neither the necessary understanding of the issue nor any ability to fix it. From the sound of it, the vendor often gives the contracting agency the same sort of isolation treatment that they would give a customer if he could find their telephone number. And guess what. At the end of the day, one of those high-handed defensive linemen -- turns out to have been at fault.

Let's explain one problem. On the surface, we were talking about a $40,000 difference in account balances; one may have been correct, but a second one must have been wrong. That rises to lawsuit level, so the matter got intensive study. It turns out the stockbroker had misinterpreted instructions for a "sweep-account" system. When a stock in your portfolio pays a dividend, the amount of the dividend is subtracted from that stock's line item and added to the line item of your money-market fund. That's fine, but there is one exception. When the money market fund itself pays a dividend, subtracting that dividend cancels out the addition, and the dividend essentially disappears from your net worth. Was this intentional? Certainly not; no one could stay in business doing that. It's not even a highly stupid error, since you can easily see yourself making the same oversight of the one implicit exception to the rule of sweep accounting. Because of this "bug" in the program involved one institution making a mistake and transmitting it to a second institution, the systematic error did not unbalance any books, until it reached mine. But since I did not detect the error for five months, there must be dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands of customers who did not detect it. Ouch. Do the math yourself to judge whether this was a serious error.

This illustration, only one of several on my personal report, leads to at least two larger principles. The first is that the transformation of money from tangible to virtual has occurred so rapidly that bullet-proof safeguards have not had time to emerge. After a century of use, most people cannot balance their checkbooks, but enough people can balance them so that systematic errors are not likely to slip past. When enough people with home computers repeatedly test the internal complexities of their virtual money accounts, confidence will develop that the system is probably working. Confidence is an important matter; it is possible to imagine quite a bank panic if the public suddenly got the idea that virtual money is maybe a mere vapor. In fact, the securitized credit panic of 2007 is a little like that. With a few new regulations and a lot of computer programming it surely will be possible to know who owns how many bum mortgages. That innovative mortgage system got ahead of its tracking verification, and we now just have to hope nothing serious happens before that gets fixed.

The second important lesson is that our health insurance system has a similar problem of far greater size and complexity. We are here talking about at least ten percent of Gross Domestic Product, in which one daily unit of measurement is in truckloads of insurance claims forms. Stocks and bonds are admittedly complicated but compared with thousands of different diagnoses, drugs, procedures, and hospitals -- verifying financial transactions is trivial compared with measuring medical ones. With a twenty billion dollar budget and ten years of lead time, we might have a shot at it. Except for the fact that during the ten-year interval, medical care will have changed so much, you will have to start over on the project.

iPhone, Skype, Land Lines and International rates

|

| Skype on the iPhone |

Skype on the iPhone works exactly as you would expect.

The iPhone automatically detects all wireless hotspots in the vicinity (it does this with or without Skype installed and it uses the wireless connection for all internet traffic while connected.)

Start Skype and you can see who's online and have a conversation with them or call them off-net through Skype just as you do on your computer.

The only deficiency I can see is that you can't multi-task while Skyping; while using the cell phone you can switch to other applications but with Skype doing this disconnects the call.

The AT&T cell + data package seems to be less money than Verizon's and the iPhone beats the pants off a Blackberry.

I have broken free from the landline tether.

I had a land-line Verizon home phone number forever but I have canceled it.

That number had been call-forwarded to my cell phone

- About $60 a month.

So I now have a Skype-in number:

call that number and if I'm offline (most of the time) the call will forward to my cell phone @ $0.02/minute.

- Exactly $60 a year (for the number, plus charges for any calls which I expect will be very few.)

$720/year vs. $60/year. Duh.

Why have any number other than my cell phone at all? In my case, I need a local area code for the guard at the gate of my condo where the phone is blocked for all non-local calls. Skype also offers international Skype-in numbers so your mother in France can call you with a local number. Etc.

The iPhone is an option for international cell phone use but it can be expensive. Here are AT&T's recommendations to reduce this expense.

When using your service outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or U.S. Virgin Islands (for either voice or data), international roaming rates apply. Your iPhone provides access to email, Visual Voicemail, Web browsing and other applications that can use a significant amount of data, so remember-international data roaming can get expensive quickly.

How iPhone Users Can Minimize International Data Charges:

- Turn Data Roaming "OFF": Be sure to download and install the latest version of iPhone software from iTunes. By default, this setting for international data roaming will be in the "OFF" position.

To turn data roaming "ON/OFF" tap on Settings>General>Network>Data Roaming - Utilize Wi-Fi Instead of 3G/GPRS/EDGE: Wi-Fi is available in many international airports, hotels and restaurants to browse the web or check email.

- Turn to Fetch New Data "OFF": Check email and sync contacts and calendars manually instead of having the data pushed to your iPhone automatically. This way you can control the flow of data coming to your iPhone.

To turn off the Auto-Check functionality tap on Settings>Fetch New Data, change Push to "OFF" and Select to Fetch Manually - Consider Purchasing an International Data Package: Purchasing an international data package can significantly reduce the cost of using data abroad. AT&T now offers four discount international data packages. The 20 MB package is $24.99 per month, the 50 MB package is $59.99 per month, 100 MB package is $119.99 per month, and the 200 MB package is $199.99 per month. See att.com/worldpackages for details and international roaming rates.

- Reset the Usage Tracker to Zero: When you arrive overseas to access the usage tracker in the general settings menu & select reset statistics. This will enable you to track your estimated data usage.

To reset Usage Tracker to Zero tap on Settings>General>Usage>Reset

Internet, Websites, and related Programming

This concludes the general topic of computers, computing and digital devices. The more specific topic area of the Internet, websites and website programming can be reached by clicking on the title below. It's large, so wait a moment for it to come up:

» Click here for WEBSITE DEVELOPMENT «

Country Auction Modernized

Only a decade ago, the Quakertown exit of the Pennsylvania Turnpike made possible a quick trip from the city to the country, letting you off in the cornfields between Sumneytown and Lansdale. Today, the rush hour traffic is as bad as anywhere else, even on the four-lane express highway known as Forty Foot Road. A comfortable two-lane highway would be about forty feet wide, so presumably, the name denotes what was once a modern miracle of a two-lane highway, in this case until quite recently. It's all built up for miles, but almost all the commercial buildings are new. Exurban sprawl has positively lurched across the landscape, making prosperous people rich, and poor people prosperous. It won't be long before the housing subdivisions demand traffic signals to protect the school children, speed limits to reduce the collisions by teenagers, and other things destined to bring high-speed travel to a crawl, all day long. When that happens, it won't be called farm country anymore.

|

| Alderfer Auction Company |

On Fairground Road, where occasionally corn is still growing, a number of large new commercial enterprises have located, among them a moving and storage company with ten or so truck loading platforms in the back. Behind that is another large new building, also with a parking lot for fifty or so cars, the auction house. Different categories come up for auction on different days, so used furniture, for example, comes up every few weeks and has to be stored as things accumulate for the big day. With a moment's thought, you can easily see why the auction is affiliated with or owned by a moving and storage company. As you go through the entrance, you are invited to sign up and identify how you plan to pay, just in case you buy something; the product of this registration is a card with a number in big colored letters. That's your number, your payment arrangement, and soon you will find no one cares anything about you except that number. The auction I was interested in was for used books, one of three or four auctions conducted in different rooms.

|

| Auctioneer |

Nearly a hundred people had numbers for used books, maybe a similar number for antique furniture and paintings. Obviously, one other purpose of the registration process is to create a mailing list of customers interested in various objects, possibly linked to a program which sends out flyers and announcements. Country auctions have always been a source of local entertainment, so non-buying spectators are able to come and watch if they wish. There seemed to be few if any casual sight-seers; just about everybody is a buyer or a potential buyer. Players, as they say.

Most of the customers probably set their alarm clocks for 5 AM or earlier; the auction is centrally located, but most everybody comes from a considerable distance. At 9 AM, very promptly, the auction began, and from his manner, you could tell the auctioneer was anxious to get started. The object for sale had been on display for a day, but most people arrived around 7 AM to examine the goods, which are frequently sold in lots, meaning a box full of thirty or forty books more or less on the same topic. At the stroke of nine, the auctioneer chanting began, "Do I have ten dollars, yeh, ten, ten, ten, five, five, ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty, sold for fifteen. Your number, sir?" Two assistants took down the customer number, and the lot number, and the price; one of the two recorded the transaction in a computer, the other on a list by hand. One gathers the man without a computer was on the look-out for shills, people trying to bid up to the price without getting stuck for a purchase. The auctioneer repeatedly assured the audience that no one but a real bidder was allowed to bid, you owned it, and no excuses about being confused. When he reached he hundredth sale, he stopped for a drink of water, and proudly noted the first hundred sales took thirty-seven minutes. It required four other assistants to fish out the lots next in line, holding them up for confirmation only, since inspecting them at as the distance was out of the question. After each sale, the assistant dumped the prize in the new owner's lap.

|

| Auction Paddle |

And yet entitled to wonder a little. The ordinary run of books thirty or forty years old will sell for between ten and twenty dollars. Books about golf, just about any old book about golf, "go" for about forty dollars. Children's books are about sixty dollars. And, to my great surprise, boxes or albums of old photographs go for over a hundred dollars. A lady next to me excitedly brought an album of old photos back to her seat and thumbed through them. "Are you a dealer?" Yes. "Who buys this stuff?" I don't know, they come to my store and just buy it. Like the Auctioneer, she had a feeling for what the retail price would be, made a calculation, and knew what she could afford to pay wholesale. What the stuff actually represented, why people wanted it, what was a good one and what was a bad one--these people in the trade had very little idea. But they knew very precisely what a fair price, and gradually lowers it until it sells. Fun Lots of fun. When a familiar insider makes a mistake and pays too much, the others laugh heartily at him. Why this funny system works has long been a mystery, but everyone except a socialist readily acknowledges it does work. At least it works better than any known substitute.