Related Topics

Philadelphia Legal Scene

The American legal profession grew up in this town, creating institutions and traditions that set the style for everyone else. Boston, New York and Washington have lots of influential lawyers, but Philadelphia shapes the legal profession.

Computers, Digital Cameras, and Cellphones

Much of the early development of the electronic computer took place in Philadelphia. We lost the lead, but it might return.

Computer Adjectives

|

| ENIAC museum |

We are indebted to Paul W. Schaffer, the curator of the ENIAC museum, for the novel concept that much of the complexity of modern computers can be reduced to a few adjectives. Before we get to that, let's explain how "computing" was done before the University of Pennsylvania revolutionized it.

We once (1940-55) used calculating machines, which are sort of overgrown calculators. As big as baby grand pianos, bearing no resemblance at all to hand calculators which sit on top of desks, calculating machines were noisy as all get-out. A typical "calculating shop" used to contain eight or ten machines, each with a specialized function. Key-punch machines, usually several of them, put holes in cards to be fed into the machines. A couple of sorting machines, to count the holes in the cards and shuffle them into pockets for specified holes, specified by temporary wiring boards on the back of the machine. A collator, which was capable of more complicated sorting and sequencing. And the calculator itself, which was able to count various combinations of holes in cards, and even print out the calculations on very large rolls of paper tape with perforated holes along the edges. Five or six trained operators would move the piles of cards around, feeding them into the appropriate machines in a prescribed order. Sitting off in a corner was the super-operator, whose job it was to design the sequences of manipulation minute and string wires around a wiring board at the back of the machines. His were the brains of the calculating system, and the wires were strung around in accordance with his design. My recollection is that IBM refused to sell these machines, and a typical cluster rented for $1100 a month in 1955. The Pennsylvania Hospital was considered very advanced for having this arrangement as its billing system, but its primitive quality can be seen in the system architecture. The whole system revolved around the concept of producing a bill for every patient in the hospital, every day. If the patient went home, he was given the latest bill. If he remained another day, the old bill was discarded and a new updated one made. It was simple, it was clever, and please don't tell Jefferson. (On the other hand, something appears very wrong about all this progress that fifty years later, the same hospital with hundreds of computers, today cannot produce a hospital bill within a month of patient discharge.)

Well, back to adjectives. John Mauchly the mathematician came to the fundamental recognition that just about everything in mathematics and calculating could be done by "iteration", and re-iteration. Don't be afraid of the words. They only mean you take a small piece of arithmetic, and perform it over and over, millions of times. You really don't need to redesign new machines for each new process, since anything you might want to do could be done by reducing it to the same sort of iteration. So there's the first adjective: Mauchly's iterative design concept amounted to a "general purpose" computer. Many different patterns, perhaps, but all performed on the same machine, just as many different pieces of music are performed on the same piano.

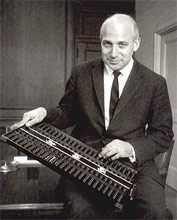

|

| John Presper Eckert, |

His graduate student, John Presper Eckert, eliminated the moving parts. Instead of metal hammers and prongs moving around, Eckert moved electrons. This step vastly increased the speed of the processing and even decreased effective maintenance. The early computers required a man to go around with a wheel-barrow, constantly replacing vacuum tubes as they burned out. But by moving electrons instead of mechanical parts, the iterative speed was so great that overall maintenance, per million calculations, was less. Eckert gave us the "electronic" computer. Together with Mauchly, the two ideas blended into the electronic, general purpose, computer.

|

| John von Neumann |

So then along came John von Neumann, observing this thing at work. Millions of punched cards were fed into the machine, but the holes in the cards represented data; the instructions were still wired in by physically connecting one contact to another, which had to be changed when the instructions changed. Von Neumann immediately saw how to get rid of half of this non-electronic effort. His contribution was to punch the instructions into program cards and feed them into the machine when the program instructions changed. So now, we had "stored instruction sets". As we still have today, the trio created the idea of a stored-instruction, general purpose, electronic computer, and actually made a working model of it. That's what promoted it ahead of the Mark I and other mechanical computers that had been developed in Europe. Vastly increased speed, vastly decreased costs -- and lots of big bucks for the manufacturer.

So, off to court, to sue for patent protection. Thousands of patents have been granted for various small innovations in the system, but who was entitled to claim ownership of the basic idea? Who invented the general purpose, electronic, stored-instruction calculator? Some puzzled judge finally worked his way out of that jig-saw puzzle by declaring that no one owned the right to have an overall patent. His reasoning was that since von Neumann had rushed to publish his work rather than rushing to the patent office first, it had become the property of the public and no longer belonged to the inventor. Compared with the contributions of a great many present computer billionaires, it really seems as though Mauchly, Eckert and von Neumann were conservatively entitled to a trillion dollars apiece. But life is not fair, and the law is an ass. Or is that so?

In later lawsuits, of which there were a great many, it came out that Mauchly and Eckert were employees of the University of Pennsylvania. They did what they were told to do and were paid for doing it. Maybe the University is entitled to trillions, thereby allowing them to pay their history professors better. But then, one final idea. The University accepted government money to do the job. Maybe all us citizens are entitled to trillions since we collectively commissioned and paid for this work. So, to recover, we seek out a class action lawyer. Standard procedure for class action lawyers is to take most of the money for themselves, sending each member of the class a share which is less than the postage required to send it.

The final outcome in this particular case was a suit between Honeywell (in Minneapolis) and Univac in Philadelphia. Univac essentially decided to go into the patent infringement business and Honeywell refused to pay royalties. Meanwhile, IBM engineers had been called as consultants for some rush job and reported to Mr. Watson that those people in Philadelphia had something really great. So, IBM paid several million to settle the patent infringement claim and started to mass-produce these things, with economic success everybody knows about. Meanwhile, the Honeywell/Univac case droned on and was eventually won by Honeywell when they produced a professor from Iowa who claimed he had the same ideas earlier. The computer concept was thus declared to be "prior art", preventing patent enforcement. By that time, IBM had such a long lead on the litigants, that the market was theirs, and IBM competitors just sort of dwindled away.

Originally published: Wednesday, June 21, 2006; most-recently modified: Monday, May 20, 2019

| Posted by: Greg Clites | Dec 13, 2009 6:37 PM |

| Posted by: Emily Larson | Nov 3, 2008 10:24 AM |

Greg Clites

Tecumseh, Michigan