4 Volumes

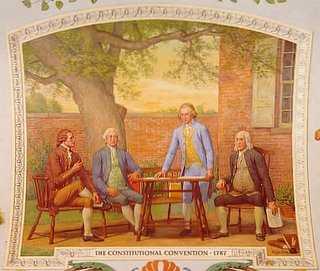

Constitutional Era

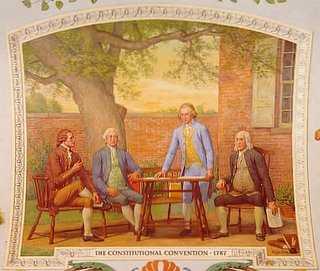

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Philadelphia Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began about the time America declared Independence. The young nation faced a clean slate and boundless opportunities.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

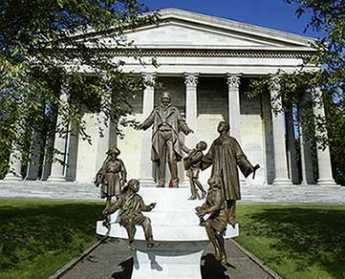

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

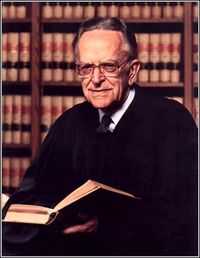

Philadelphia Legal Scene

The American legal profession grew up in this town, creating institutions and traditions that set the style for everyone else. Boston, New York and Washington have lots of influential lawyers, but Philadelphia shapes the legal profession.

William Penn Conducts a Witchcraft Trial

|

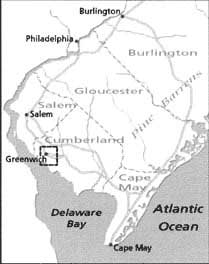

| Salem Witch Trials |

When trials for witchcraft are mentioned, most people think of Salem, Massachusetts, where 19 people were hanged as witches and hundreds were imprisoned, in 1692. The Salem trials were apparently provoked by a minister from Barbados, and it is thought the uproar about witches in America was in part related to encountering the spiritualism of the Indian tribes. Whatever its origins, the issue has been in the background for a long time, and occasionally even surfaces today in accusations of "Satanic rituals."

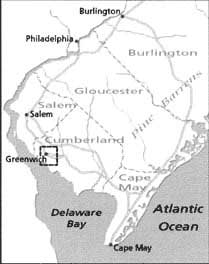

There were trials for witchcraft in New York in 1664, in West Chester in 1672, and in Princess Ann county of Virginia. But the trial of central interest to Pennsylvania occurred in 1683, when Governor Penn presided over it, himself. Pennsylvania had adopted British laws, including one from James I concerning the crime of witchcraft, so Penn probably had little choice but to hold the trial. His fellow judges were his Council; there is little doubt the outcome reflects his opinion.

The accused were two Swedish women, Margaret Mattson and Yeshro Hendrickson, who pleaded not guilty. Numerous witnesses told vague stories, and Mattson's daughter expressed her conviction of her mother being a witch. Governor Penn finally charged the jury, which brought in a memorable verdict. The defendants were found guilty of "having the common fame of a witch" but not guilty in the manner and form.

There are times, and this was one of them, when it is not useful to be overly precise in your meaning.

William Penn: Visionary with Persuasiveness

|

| William Penn |

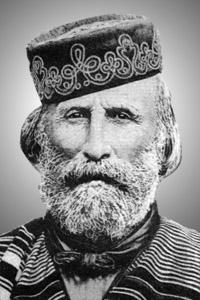

It was a signal and blessed providence which first induced so rare a genius, so excellent and qualified a man as Penn, to obtain and settle such a great tract as Pennsylvania, say 40,000 square miles, as his proper domains. It was a bold conception; and the courage was strong which led him to propose such a grant to himself, in lieu of payments due to his father. He besides manifested the energy and influence of his character in court negotiations, although so unlikely to be a successful courtier by his profession as a Friend, in that he succeeded to attain the grant even against the will and influence of the Duke of York himself who, as he owned New York, desired also to possess the region of Pennsylvania as the right and appendage of his province.

"This memorable event in history, this momentous concern to us, the founding of Pennsylvania, was confirmed to William Penn the Great Seal on the 5th of January, 1681."

-John F. Watson,

Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time

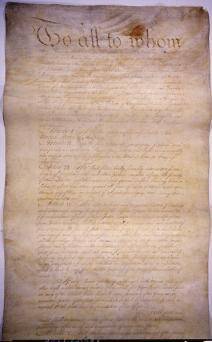

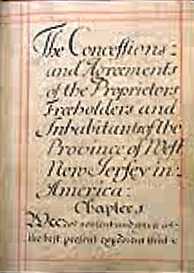

Concessions and Agreements

|

| Concessions and Agreements |

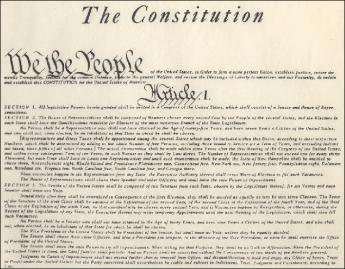

The United States Constitution is a unique achievement, but it had significant precursors, many of which James Madison had studied at Princeton. In the days of difficult ocean travel, almost all colonies were bound by an agreement to maintain loyalty to their European owners in spite of receiving latitude to govern themselves. Charters and documents defining these roles were generally written by the owners, and the colonists could pretty much take them or leave them. In the case of New Jersey in 1664, however, a very formidable lawyer and friend of the King named William Penn was drawing up agreements to his own conditions of sale, taking care that the grant of governing authority he received was favorable. Penn's relationship to the King was unusually good, to say the least. He had more reason to be wary of nit-pickers in the King's administration, trying to anticipate every conceivable disappointment for some successor King.

For his part, Penn wanted to make colonial land attractive to re-sell to religious groups who had experienced harsh government oppression; he wanted no obstacles to his announcing there would be no religious oppression in New Jersey. He was offered the role of sub-king although he hastily rejected any such title, and needed to repeat the formalities of the Charter to define his role and reassure his settlers about that matter. Furthermore, he was dealing with the heirs of Carteret and Berkeley, active participants in North and South Carolina. So Penn's method of achieving basic rights was influenced by prior thinking in the Carolinas, as the thinking of John Locke secondarily influenced matters in Delaware and Pennsylvania. These ideas were incorporated in a New Jersey document called "Concessions and Agreements." The concepts were not wholly the ideas of William Penn, but he did write it, and it does contain many ideas that were uniquely his. Understandings about limits were set down, argued about, and agreed to. The owner risked money, the colonist risked his life. Neither would agree unless a reasonable bargain was struck in advance of any dispute. Furthermore, the main value of a colony was beginning to shift from trading rights to real estate rights. Carteret and Berkeley had not only been principals in both the Carolinas and the Jerseys but had been involved in a number of such investments in Africa and the West Indies; New Jersey was just another business deal. It was conventional for documents of this type to define the method of selection of a governor, the establishment of an assembly of colonists, and some sort of council to attend to day to day affairs. In that era, few colonists would cross the ocean without a guarantee of religious freedom, at least for their own brand of religion. Standard clauses which may sound strange in today's real estate world, were then necessary because it was a transfer of not merely land, but also the terms of government. In the case of the Quaker colonies, many of these stipulations were included in the earlier charter from the King. It seems very likely that Penn hovered around and negotiated these points which he wished to have the King agree to; and then once the land was safely his, Penn repeated and expanded these stipulations with the colonists in his Concessions and Agreements . It wasn't exactly a Constitution, but it reads a lot like the one America adopted a century later.

|

| Proprietors House |

Quakers had suffered persecution and imprisonment, and knew exactly what they feared; on the other side, it seems likely Carteret and Berkeley were less interested. So this real estate transfer document conceded almost anything the colonists wanted and the King would stand for, couched in conciliatory phrases. For example, no settler was to be molested for his conscience, and liberty was to be for all time, and for all men and Christians. Elections, by the way, must be annual, and by secret ballot. While law and order must prevail, nevertheless no man is to be imprisoned or molested except by the agreement of twelve men of the neighborhood. On the matter of slavery, no man was to be brought to the colony in bondage, save by his own consent (that is, indentured servants were to be permitted). And in what proved to be a final irony for William Penn, there was to be no imprisonment for debt. Almost all of these innovative ideas survived into the U.S. Constitution a century later, but the most innovative idea of all was to set them all down in a freely-made agreement in writing. This was not merely how a government was organized, it defined the set of conditions under which both sides agreed it would operate.

It was, of course, more than that. It was a set of reassurances to settlers who had been in New Jersey before the English arrived that they, also, would be treated as equals. It was a real estate advertisement to the fearful religious dissenters back in England that it was safe to live here. And it was a reminder to future Kings and Parliaments that this is what they had promised.

The pity and a warning, is that the larger vision of a whole continent governed fairly by common consent may have been too grandiose for a little band of New Jersey Quakers, surrounded as they were by an uncomprehending world. All utopias are helpless when stronger neighbors reject the basic premise. However, it was the expansion of the pacifist concept to the much larger neighboring territory of Pennsylvania that proved to be just too much for such a small group of friends to manage by consensus, particularly when unbelieving immigrants began to outnumber them. But the essential parts of it certainly remained in the minds of delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. When the minutes of the Constitutional Convention speak of the "New Jersey Plan", the Concessions and Agreements was what they had in mind.

REFERENCES

| Concessions and Agreements of New Jersey 1676: William Penn | New Jersey State Library |

| Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City: Howard Gillette Jr.: ISBN-13: 978-0812219685 | Amazon |

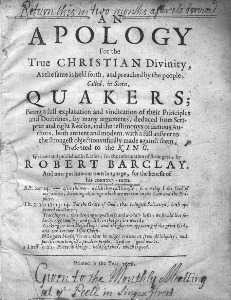

East Jersey's Decline and Fall

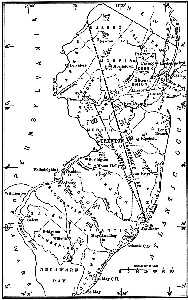

The colony of New Caesaria (Jersey) had two provinces, East and West Jersey, because the Stuart kings of England had given the colony to two of their friends, Sir George Carteret and John, Lord Berkeley, to split between them. Both provinces soon fell under the control of William Penn but it took a little longer to acquire the Berkeley part, so the Proprietorship of East Jersey was the oldest corporation in America until it dissolved in 1998.

|

| Apology for the True Christian Divinity |

It would appear that Penn intended West Jersey to be a refuge for English Quakers and East Jersey was to be the home of Scots Quakers. Twenty of the original twenty-four proprietors were Quakers, at least half of them Scottish. Early governorship of East Jersey was assumed by Robert Barclay, Laird of Urie, who was certainly Scottish enough for the purpose, and also a famous Quaker theologian. Even today, his Apology for the True Christian Divinity is regarded as the best statement of the original Quaker principles. However, Barclay remained in England, and his deputies proved to be somewhat more Scottish than Quaker. Eighteenth-century Scots were notoriously combative and soon engaged in serious disputes with the local Puritans who had earlier migrated into East Jersey from Connecticut with the encouragement of Carteret. This enclave of aggressive Puritans probably provided the path of migration for the Connecticut settlers who invaded Pennsylvania in the Pennamite Wars, so the hostility between Puritans and Quakers was soon established. The Dutch settlers in the region were also combative, so the eastern province of Penn's peaceful experiment in religious tolerance started off early with considerable unrest. Of these groups, the Scots became dominant, even referring to the region as New Scotland. To look ahead to the time of the Revolution, most of the East Jersey leadership was in the hands of Proprietors of Scottish derivation, with at least the advantage that these were likely to have been very vigilant in seeing Proprietor rights originally conferred by the British King, continue to be honored by the new American republic.

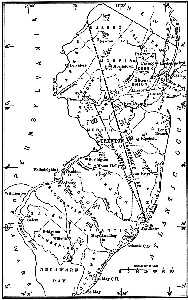

East Jersey was probably already the most diverse place in the colonies when loyalists and revolutionaries took opposite sides in the bitter eight-year war over English rule, with hatred further inflamed when the victors in the Revolution divvied up the properties of loyalists who had fled. The earlier conflict was created by management blunders of the Proprietary leadership itself. Instead of surveying and mapping, before they sold off defined property, like every other real estate development corporation, the East Jersey Proprietors adopted the bizarre practice of selling plots of land first and then telling the purchaser to select its location. In the early years, it is true that good farmland was abundant, but inevitably two or more purchasers would occasionally choose overlapping plots of land. The Proprietors were astonishingly indifferent to the resulting uproar, telling the purchasers that this was their problem. The outcome of all this friction was that settlers petitioned London for relief, and in 1703 Queen Anne took governing powers away from both the East and West proprietorships and unified the two provinces into a single crown colony. The Queen obviously nursed the hope that South Jersey would impose a civilizing influence on the North, but immigration patterns determined a somewhat opposite outcome. Both proprietorships, however, were allowed to continue full ownership rights to any remaining undeeded property.

In later years, the East Jersey Proprietors created more unnecessary problems by attempting to confiscate and re-sell pieces of land whose surveys were faulty, sometimes of a property occupied with houses for as much as fifty years. This East Jersey proprietorship, in short, did not enjoy either a low profile or the same level of benevolent acceptance prevailing in the West Jersey province. A climate of skepticism developed that easily turned any management misjudgment into a confrontation.

|

| New Jersey Line |

The East Jersey proprietorship operated by taking title to unclaimed land, and then reselling it. In what seemed like a minor difference, the West Jersey group never took title itself, but merely charged a fee for surveying and managing the sale of unclaimed land. The upshot of this distinction was that the East Jersey group got into many lawsuits over disputed ownership, which the West Jersey Proprietorship largely escaped. The nature of unclaimed land in New Jersey is for ocean currents to throw up new islands in the bays between the barrier islands and the mainland, or pile up new swampland along the banks of the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Such marshy and mosquito-infested land may have little value to a farmer but lately has become highly prized by environmentalists, who supply class-action lawyers with that nebulous legal concept of "standing". The posture of the West Jersey Proprietors is to be happy to survey and convey clear title to a particular property for a fee, but a buyer must come to them with that request. The East Jersey method put its proprietors in repeated conflict over possession and title, with idealists enjoying free legal encouragement from contingent-fee lawyers. By 1998, the Proprietors of East Jersey had endured all they could stand. Selling their remaining rights to the State for a nominal sum, they turned over their historic documents to the state archives. The plaintiff lawyers could sue the state for the swamps if they chose to, but the East Jersey Proprietors had just had enough.

The only clear thing about all of this is that the Proprietors of West Jersey now stand unchallenged as the oldest stockholder corporation in America. It's not certain just what this title is worth, but at least it is awfully hard to improve on it.

Jury Nullification

|

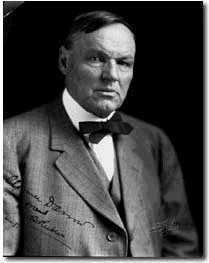

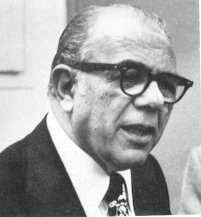

| Tom Monteverde |

We must be grateful to the late distinguished litigator, Tom Monteverde, for reminding us of the importance of the jury in American history. Juries seldom realize how much power they can have if they unite on a common purpose. In fact, juries have the implicit right to veto almost anything the rest of government does, by rendering it unenforceable. If the jury opinion is a majority view, nothing but a civil war can legally stop them. So it helped Washington to have jury nullification seem an invincible Quaker idea, while the South trusted a rich slave-owner who had renounced power.

|

| William Penn |

The right to a jury trial originated in the Magna Carta in 1215, but a jury's essentially unlimited power was established four centuries later by Quakers. The legal revolution grew out of the 1670 Hay-market case, where the defendant was William Penn, himself. Penn was accused of the awesome crime of preaching Quakerism to an unlawful assembly, and while he freely admitted his guilt he challenged the righteousness of such a law. The jury refused to convict him. The judge thus faced a defendant who said he was guilty and a jury who said he wasn't. So, the exasperated judge responded -- by putting the jury in jail without food.

The juror Edward Bushell appealed to the Court of Common Pleas, where the problem took on a new dimension. The Justices certainly didn't want juries flouting the law, but nevertheless couldn't condone a jury being punished for its verdict. Chief Justice Vaughn decided that intimidating a jury was worse than extending its powers, so the verdict of Not Guilty was upheld, and Penn was set free. Essentially, Vaughn agreed that any jury that wasn't allowed to acquit was not really a jury. In this way, the legal principle of Jury Nullification of a Law was created. A verdict of not guilty couldn't make William Penn innocent, because he pleaded guilty. A verdict of not guilty, under these circumstances, meant the law had been rejected. Jury nullification thus got to be part of English Common Law, hence ultimately part of the American judicial system.

|

| Andrew Hamilton |

This piece of common law was a pointed restatement of just who was entitled to make laws in a nation, whether or not nominally it was ruled by a king or a congress. Repeated British evasion of the principles of jury trial became an important reason the American colonists eventually went to war for independence, and probably a better one than some others. The 1735 trial of Peter Zenger was an instance where Andrew Hamilton, the original "Philadelphia Lawyer", convinced a jury that British law, blocking newspapers from criticizing public officials for improper conduct, was too outrageous to deserve enforcement in their court. In that case, jury defiance became even more likely when the judge instructed the annoyed jury that "the truth is no defense". Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette was here quick to come to the side of jury nullification, saying, "If it is not the law, it ought to be law, and will always be law wherever justice prevails." Franklin quickly became allied with Andrew Hamilton, who became Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly.

|

| John Hancock |

The Zenger case was often stated to be the origin of the Freedom of the Press in our Constitution fifty years later, but in fact the First Amendment merely provides that Congress shall pass no laws like that. Hamilton had persuaded the Zenger jury they already had the power to stop enforcement of such tyranny, and the First Amendment could be seen as trying to prevent enactment of laws that will foreseeably incite a jury to revolt.

The Navigation Acts of the British government, for example, were predictably offensive to the American colonists, whose randomly chosen representatives on juries were then rendered useless with their wide-spread refusal to convict. This, in turn, provoked the British ministry. John Adams made a particularly famous defense of John Hancock who was being punished with confiscation of his ship and a fine of triple the cargo's value. Adams was later singled out as the only named American rebel the British refused to exempt from hanging if they caught him. As everyone knows, Hancock was the first to step up and sign the Declaration of Independence, because by 1776 there was widespread colonial outrage over the British strategy of transferring cases to the (non-jury) Admiralty Court. Many colonists who privately regarded Hancock as a smuggler were roused to rebellion by the British government thus denying a defendant his right to a jury trial, especially by a jury almost certain not to convict him. To taxation without representation was added the obscenity of enforcement without due process. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the newly created United States, ruled in 1794 that "The Jury has the right to determine the law as well as the facts." And Thomas Jefferson built a whole political party on the right of common people to overturn their government, somewhat softening, it is true, when he grasped where the French Revolution was heading. Jury Nullification then lay fairly dormant for fifty years. But since the founding of the Republic and the reputation of many of the most prominent founders was based on it, there was scarcely need for any emphasis.

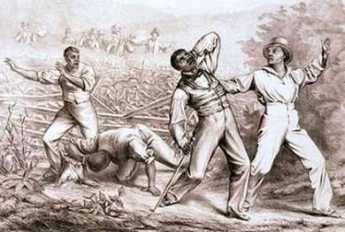

|

| Slave |

And then, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 began to sink in. It became evident that juries in the Northern states would routinely refuse to convict anyone under that law, or under the Dred Scott decision, or any other similar mandate of any branch of government. In effect, Northern juries threw down the gauntlet that if you wanted to preserve the right of trial by jury, you had better stop prosecuting those who flouted the Fugitive Slave law. In even broader terms, if you want to preserve a national government, you had better be cautious about strong-arming any impassioned local consensus. A rough translation of that in detail was that no filibuster, no log-rolling, no compromises, no oratory, no threats or other maneuvers in Congress were going to compel Northern juries to enforce slavery within their boundaries of control. All statutes lose some of their majesties when the congressional voting process is intensely examined, and public scrutiny of this law's passage had been particularly searching. Even if Southern congressmen would be successful in passing such laws, it wasn't going to have any effect around here. The leaders of Southern states quickly got a related message, and their own translation of it was, "We have got to declare our independence from this system of government that won't enforce its own laws". If juries can nullify, then states can nullify, and the national union was coming to an end. Both sides disagreed so strongly on this one issue they were willing, for the second time, to risk war for it.

Ku Klux Klan

The idea should be resisted that Jury Nullification is always a good thing. After the Civil War, many of the activities of the Ku Klux Klan were tolerated by sympathetic juries. Many lynch mobs of the Wild, Wild West were encouraged in the name of law and order. Prohibition of alcohol by the Volstead Act was imposed on one part of society by another, and Jury Nullification effectively endorsed rum-running, racketeering, and organized crime. The use of marijuana and abortion are two further examples where disagreement is so strong that compromise eludes us. What is at stake here is protecting the rights of a minority, within a society run by a majority. If minority belief is strong enough, jury nullification issues an unmistakable proclamation: "To proceed farther, means War."

|

| Oliver Wendell Holmes |

That's a somewhat strange outcome for a process started by pacifist Quakers, so the search goes on for a better idea. Distinguished jurists differ on whether to leave things as they are. In a famous exchange, Oliver Wendell Holmes once had dinner with Judge Learned Hand, who on parting extended a lawyer jocularity, "Do justice, Sir, do justice." To which, Holmes then made the somewhat surly response, "That is not my job. My job is to apply the law."

Thus lacking any better approach, it is hard to blame the US Supreme Court for deciding this was something best left unmentioned any more than absolutely necessary. The signal which Justice Harlan gave in the majority opinion on the 1895 Sparf case was the very narrow ruling that a case may not be appealed, solely on the basis that the trial jury was not informed of its right to nullify the law in question. Encouraged by this vague hint, what has evolved has been a growing requirement that incoming jurors take an oath "to uphold the law", officers of the court (ie lawyers)are discouraged from informing a jury of its true power to nullify laws, and Judges are required to inform the jury in their charge that they are to "take the law as the judge lays it down" (ie leave appeals to higher courts). If a jury feels so strongly that it then persists in spite of those restraints, well, you apparently can't stop them. Nobody thinks this is a perfect solution, and aggrieved defendants like the Vietnam War protesters are quite vocal in their belief that the U.S. Supreme Court finally emerged with a visibly asinine principle: a jury does indeed have the right to nullify, but only as long as that jury is unaware it has that right. That's almost an open invitation to perjury if accurate; but while it's not precisely accurate, it comes close to being substantially true.

That's where matters stand, and apparently will stand, until someone finds better arguments than those of Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Andrew Hamilton -- and William Penn.

The King's Last and Final Word

|

| King Charles II |

In 1662, King Charles II of England signed a charter, giving a strip of land in America to the inhabitants of Connecticut, and that land to stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. And then, eighteen years later, the same king signed a second charter, giving much the same land to William Penn. As lawyers say, these are the facts. In the many lawsuits, arguments, and wars which followed, no one ever seriously raised the point that King Charles was unaware that he was giving the same land twice, so it must be assumed he knew exactly what he was doing, and did it on purpose. In fact, he did this sort of thing many times, in other cases. The legal disputes which this double-dealing inspired, are therefore entirely concerned with whether the King had a right to do it, and if so, whether that right would normally be recognized (i.e. durable) when we threw off the King and became a republic. The matter was considered by many courts many times, and in every single case, the judgment was in favor of Pennsylvania.

|

| Oliver Wendel Holmes Jr. |

Consider Connecticut's probable attitude toward all this. The colony was settled by Calvinist dissenters, so-called Roundheads for their surprisingly contemporary haircuts, adherents of General Cromwell, executioners of King Charles I during English Civil War. They gave Old Testament first names to their own children, and had always known they couldn't trust that licentious King. Giving their land away after he had promised it to them was just about what they always expected. When, after seventy years of growing families of fifteen to seventeen children, they discovered that Connecticut soil was merely a pile of pebbles left by the glaciers and covered with a thin layer of topsoil, they became even more convinced they had been cheated in the first place, and the bargain was no bargain. The reverse side of this enduring religious hatred will reappear in a few paragraphs.

The Proprietors of Pennsylvania, by this time no longer pacifist Quakers, but while descendants of William Penn, converted Anglicans and great friends with the King, took the matter calmly. The Connecticut lawyers were saying that if you sell or give away some land, it is no longer yours, so you can't give or sell it a second time. That is the modern view perhaps, but the English-speaking world was changing from a feudal, semi-nomadic, culture into a settled agricultural country where fixed boundaries were only starting to be important. That's where the world was going, but at the time King Charles gave away the land, it was far more important for the King to be able to reward successful underlings, and punish rebellious tribes, as the situation warranted. Ownership of land then seemed a nebulous thing at best, and the King was the best judge of how things should be divvied up.

Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced his book on The Common Law, by warning "The life of the law has not been logic, it has been experience." For life to go on and prosperity to endure, some decision must be made and held to, right or wrong. Stare decisis. That's of course fine for judges to say, but it must be observed that when people divide up on this question, where they stand depends heavily on where their ancestors stood on the English Civil War, and where their ancestors happened to be living during the so-called Pennamite Wars. As matters turned out, courts kept deciding in favor of Pennsylvania, and Connecticut kept bringing it up, again.

William Allen, Tory

|

| William Allen |

William Allen was once famous for his expensive carriage and a team of horses, at a time when there were only eighty carriages in the colony. He was born wealthy but personally made considerable sums in maritime trade, which in those days included a mild form of piracy called privateering. Taking his accumulated wealth, he invested heavily in colonial real estate. His urban ventures included the land under Independence Hall, and his lands in the hinterland included the present town of Easton. He was a tough businessman, providing "muscle" where needed in a colony dominated by pacifist Quakers. At one point, he imported a thousand muskets and ammunition for the use of settlers in the Lehigh Valley who had difficulties with the Indians and Connecticut invaders. Allentown is named after him.

|

| Philadelphia Lawyer |

It is difficult to apply present standards of judgment to Allen. William Penn had been given the colony on condition that he protect and maintain it. That was clearly a difficult challenge for a Quaker colony in the wilderness, surrounded by Indians, French and Spanish buccaneers, and neighboring colonies who were far from pacifist themselves. The system often amounted to giving land to subcontractors like Allen, on condition that they maintain law and order. Furthermore, Allen was quite obviously a person of parts. His credentials as Chief Justice were based on his attendance at the Inns of Court when almost all other lawyers were trained by local apprenticeships. His father in law was Andrew Hamilton, the famous "Philadelphia lawyer" who won the landmark case for Peter Zenger and later became the leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly and mentor to young Benjamin Franklin. His land-dispute services in the negotiations with Lord Baltimore were notable. In general, he was a continuing force for peace and stability, and no one held it against him that peace and stability suited his needs as a landlord and merchant. To him, the battle for independence was just another unsettling disturbance which prevented the colony from achieving its potential.

His daughter married John Penn, the grandson of William Penn, who was the local representative of the Proprietors and later the Governor. All in all, it is not surprising that he retreated to his home on Germantown Avenue, called Mt. Airy, when the revolution broke out. Unlike many other Tories who fled to Canada, he felt his past services would protect him if he remained quiet and secluded until the war was over. He didn't quite make it, dying in his mansion, in 1780.

Articles of Confederation: Flaws

DURING the twenty-five years (1776-1801) government was in Philadelphia, Americans who had rebelled against tight royal rule uncovered many defects in its opposite -- a loose association of states. Loose associations only preserve fairness by operating with unanimous consent, which is, of course, unfair to a thwarted majority, unless a dissenting minority thwarts itself as a gesture of kindness. The Founding Fathers ultimately devised a formula of weakening power by dividing it into layers -- national, state, county, municipal -- and seeking to confine minority dissent to the weakest political unit. Persuasion and peer pressure were given time to work up the ladder of appeal to a wider, more powerful body of citizens. Bottom upward by choice; top-down only in desperation. Furthermore, persuasion first, force as last resort. An implicit third safety valve emerged: if a good idea is smothered by a local concentration of bigotry, appealing to a wider population includes being heard by more viewpoints. No one claims to have authored this whole prescription or foreseen its hidden benefits; it apparently evolved by trial and error. There was another latent discovery for America's sparse population in a hostile wilderness: maintaining harmony was more essential than efficiency. It would be hard to consolidate more Quakerly concepts of governance in one document. Not exactly assembled, it emerged and was admired. The local Quaker merchants were living proof that harmony made riches for anyone, while force only works against weaker people. George Washington the cavalier general came to Philadelphia and gave it a softly Virginian twist, over and over: Honesty is the best policy. It seems to have originated in one of Aesop's Fables.

It is not necessary that the [Constitution] should be perfect; it is sufficient that [the Articles of Confederation are] more imperfect.

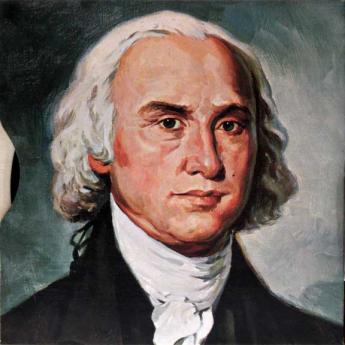

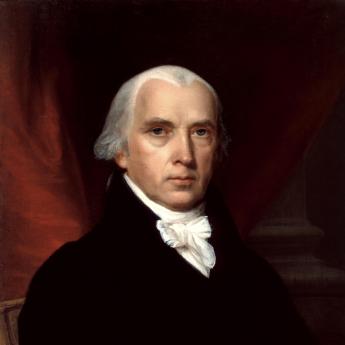

|

| James Madison |

Recently examined documentation reveals James Madison, the main theoretician of the closed-door Constitutional Convention, to have been severely contemptuous of state legislatures at this time in his life, and rather severely defeated by John Dickinson in a political quarrel in mid-convention about the powers of small states. From this fragile evidence emerges the idea that in balancing the powers of state and national governments in the "federal" system, it may have been someone else's idea that the greater freedom to move out of an offending state into a more favorable one, would appreciably restrain state legislative abuses. Even with this feature built into the system with the national government to enforce it, Madison is said to have been in a state of depression that the Convention refused to agree to his idea of giving Congress veto power over state laws. It took some time for improved transportation to strengthen this competition between states, but it may not be an accident that Delaware now leads the way in responding to the implicit opportunity.

Philosophy and history are different. The Framers gradually acknowledged a patched charter of tribal allegiance was insufficient and thus adjusted to the idea of a central government. They tweaked a decentralized model of governance to get the states out of the road, without antagonizing them so much they would not ratify it. Although it is commonplace to say the Articles of Confederation were a weak failure, the Articles did reflect American attitudes at the beginning of our formative period. The Constitution would not have been acceptable if the Articles of Confederation had not first been given a trial. By the end of the 1787 Philadelphia negotiation, the nature of the final proposal was to define a few absolutely minimum powers for a national government, identify a few other powers as destructive when in the hands of any other level of government, and leave a vast undefined area: where new and novel problems would be tried out in the states, then passed to a national level if necessary. Anticipating constant mid-course corrections was an important objective for even a minimalist Constitution, not the least of those challenges was to create ways to keep it minimalist. Simplicity itself keeps it hard to change. Starting at the bottom of the layers of government continues to this day to introduce new and unexpected problems to the "laboratory of the states" or even lower, working upward only as proven necessary, or spread nationally only after the solution is highly successful. It is a legacy of slavery, the Civil War, and direct election of Senators (Amendment XVII) that many Americans still fail to welcome the merits of this approach, or lack the patience to try it for their pet ideas. Considering the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution as two documents with continuous goals, we got it right, the second time.

And we got it right in the environment of Eighteenth-century Quaker Philadelphia, where a tolerant examination of new ideas was more venerated than in any other place in the civilized world. With a combination of wisdom and impasse, minor issues were left to the future. It is true this sometimes creates problems of neglect. But it makes it possible to define those few issues which must never change. An unexpected virtue of minimalism surfaced eighty years later: many men understood it well enough to die for it.

|

|

Edwin Corwin's "John Marshall and the Constitution" |

Much has been written about the separation and balance of powers between the three branches of the federal government. However, the real balance of power in the Constitution in 1787 was vertical, between the central government and the constituent states. Balancing power horizontally, within the central government's branches, is a way of preventing one side of this other argument from tilting the state/federal balance in its own favor, or slowing down the effect of any victories by one side. In other words, it preserved citizen liberty to choose. From this continuing two-dimensional struggle emerges the explanation for filibusters, the seniority system, the confirmation process for Supreme Court and Cabinet appointments. It also calls into question the Seventeenth Amendment, where the state legislatures lost the power to appoint U.S. Senators. In 1786 the states had all the power, in 2009 state power is much diminished; but it is not entirely gone by any means. It is true the cry for states rights, essentially an appeal to the Deity for Justice is futile. If states are to wrest power back from the federal government, it will be by the adroit exercise of powers buried within the balanced powers of the federal branches, but it can succeed if the public ever wants it to succeed. The Framers seem to have overlooked the possibility that federal power could someday outgrow its blood supply, simply growing too big to manage. It is also true the Framers neglected the possibility of a protracted period of disagreement between two halves of the electorate. At least in these particulars, there is room for the further evolution of the Constitutional principle.

While features of the present Constitution can sometimes be linked to the correction of flaws in the Articles, one by one amendment never seemed to be quite enough. Subsequent analysis of Original Intent has often had to contend with the unspoken intent of earlier negotiators to strengthen partisan advantage in later struggles. The political battles being fought at the beginning, which except for slavery are substantially the same today, were sometimes being promoted for reasons which now seem merely quaint. Fine, everyone can agree it was complex. Still, there was a recurring uneasiness: what was the underlying flaw in the Articles? What, as they say, is the take-home point?

One widely accepted summary, probably a correct one, of what was centrally wrong with the Articles of Confederation, lies in a concise observation, which follows, from Edward S. Corwin's book John Marshall and the Constitution:

"The vital defect of the system of government provided by the soon obsolete Articles of Confederation lay in the fact that it operated not upon the individual citizens of the United States but upon the States in their corporate capacities. As a consequence, the prescribed duties of any law passed by Congress in pursuance of powers derived from the Articles of Confederation could not be enforced."

And that's how many Revolutionary Americans, possibly most of them, had wanted to have it. They were in revolt against all strong government, not just the King of England. They surely would have applauded Lord Acton's declaration that "All power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Thirteen years of near-anarchy taught them they must at least give some limited powers to a central government, but it was to be no more than absolutely necessary. For some, the Ulster Scots, in particular, even the absolutely minimum amount was still just a bit too much. In effect, these objectors wanted a democracy, not a republic.

To deconstruct Professor Corwin's analysis somewhat, the equality-driven followers of Thomas Jefferson believed the insurmountable obstacle for uniting sovereign states is that they are sovereign, and won't give it up. The merit-driven followers of Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, and George Washington bitterly resisted; in business and in war you need the best leaders to rise to power. The function of common men is to select the best among themselves to be leaders. Only James Madison seems to have grasped that ideal government might tend more toward a republic for purposes of the enumerated federal powers plus enumerated powers specifically denied to the states. For lesser issues, perhaps a purer democracy would be just as workable. However, in operation, it took scarcely a year to discover that the common man would not automatically select the best man he knew to be his representative. In fact, there exists a considerable populist sentiment, that wealth and success outside government are actually disqualifications for office. To some extent, this reverse social Darwinism is grounded in an unwillingness of the upper class to serve in government, perhaps because service to the country interferes with the lifestyle of unrestrained power and wealth which other occupations allow, but is forbidden to public servants. In any event, we persist in the fruitless argument whether America is a democracy or a republic; it was designed to be a mixture of both. Within the time of the first presidency, the unattractive realities of mixing human nature with elective politics transformed the meanings of the Constitutional document to something that was never written there, and other nations have largely failed to grasp. It apparently also worked a major transformation in its main author. James Madison first quarreled with his ally, Alexander Hamilton, and joined forces with the Constitution-doubter Thomas Jefferson. His mentor and idol, George Washington, essentially never spoke to him again.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

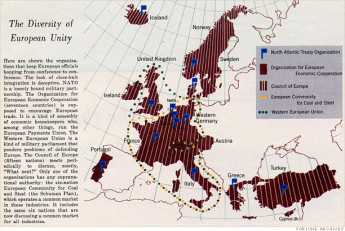

States rights no longer confronts America directly, because the Founding Fathers managed to get around it until the Civil War, and then the Fourteenth Amendment enabled the federal judiciary to attenuate state sovereignty somewhat further without eliminating the architecture of a federation of states. In other words, in two main steps we deprived the states of some sovereignty, but no more than absolutely necessary, and we took more than a century to do it. The European Union currently faces the same obstacle; this is how we solved it. If they can get the same result in some other peaceful way, good luck to them. Our framers used the language "Congress may...or Congress may not..." They only dared to strip state legislature of a few powers because they needed the legislatures to ratify the Constitution, a gun you can only fire once. Thus, they forbade states the right to issue paper money, the power to interfere in private contracts, and such, as enumerated in Article I, Section X, where the operative phrase is "The states are forbidden to..". The framers were willing to strip the unformed Congress of many more specific powers than the all-too-existing states; the Constitution can be read as a proclamation of the powers which any central government simply must possess. There might be other desirable powers, but here is the minimum. After eighty years, individual Southern states asserted their unlimited powers extended to nullification and secession, and because of a perceived need to preserve slavery would not back down. The Constitutional consequence of this national tragedy was the Due Process section of the Fourteenth Amendment, which has since been purported by the Supreme Court to mean that whatever the federal government may not do, the states may not do, either. However, Due Process traces back to the Magna Carta and has been so tormented by an interpretation that for the purpose stated, it is growing somewhat too elusive to remain useful. For historical reasons, we never gave a fair trial to the original proposal to address the federal/state dilemma. The Constitutional Convention was held in confidence, many delegates changed their minds along the way, and many ideas were more perceived than enunciated. It is plausible that the original strategy originated with Madison's teachers and emerged from many discussions, but there were several delegates in attendance with the sophistication to originate it. In a convention of egotists, there were even a few who would put their ideas in someone else's mouth.

The concept of how to curtail power in a non-violent way, can be called Regulatory Competition. Mitt Romney seemingly plans to promote the idea as a central feature of his political run for President of the United States, using a variant he has developed with Glenn Hubbard, the Dean of the Columbia University School of Business. The idea does still work reasonably well with state taxes and corporate regulation. If a state raises a tax, estate tax for example, in a burdensome way, people will flee to a state with more reasonable taxation. Corporations have learned how to shift legal headquarters to Delaware and other states which court them, and in really desperate cases will move factories or whole businesses. There is little doubt this discipline is effective, and little doubt that some cities and states have been punished severely for encouraging an anti-business environment. Whether the Fourteenth Amendment could be cleverly amended to expand this competitive effect without reintroducing segregation or the like, has not been seriously considered, but perhaps it should be. There are however not too many alternatives to consider.

As far as advising our European friends is concerned, it would be important to point out that the original version of Regulatory Competition completely depends for its effectiveness on the freedom to flee to some other state within the union. A common language is a big help to unity, but the ability to move residence is essential, so for practical purposes, both a common language and freedom of migration are required. Underlying such concessions is a sense of tolerance of cultural differences. That is unfortunately where most such proposed unions have either resorted to violence or failed to unite. And of course, the power which might otherwise be abused must then be shifted from the federal, back to a state level. What surfaces is a sort of one-way street? It remains far easier to devolve into little statelets than to unite for the benefits of scale. A working majority under the likes of Thomas Jefferson might have been assembled in the Nineteenth century but was held back by coping with the expanding frontier. During the Twentieth century, it would have been held back by the need to deal with world power. The Second Tea Party seems to have some inclination along these lines, but it remains to be seen whether some overwhelming need for world power will once more overcome the obvious national ambivalence about it.

The revised proposal for the regulatory competition takes the proposal to a different level, possibly a more workable one. Workers in the United States can freely move from one state to another but are restrained by national laws from equally free movement between nations. Removing that barrier makes the European Union attractive, although it inflames local nationalism. Since it seems more palatable to allow the currency to move, perhaps a little tinkering would be sufficient to permit uniform monetary rules to be the hammer which forces nations into permitting free trade on a global scale. The people themselves can remain at home in their national costumes, perhaps perfecting their religions in more churches and language skills in more schools. Meanwhile, the insight of Adam Smith would prevail for the long-term prosperity of everyone. Each party in a transaction feels enriched by it, the seller preferring to have the money, and the buyer preferring to own the goods. Multiplied a trillion-fold, these improvements in everyone's condition result in the steady enrichment of all.

Perpetual?

|

|

George Washington Was he the 11th President of the United States? |

We must be indebted to Stanley L. Klos for his recent book called President Who? in which he makes a persuasive case that George Washington was actually the eleventh President of the United States, there have been ten previous Presidents under the Articles of Confederation. The awkward fact that the Articles were not ratified until 1781, is a different sort of issue which possibly helps explain some of the confusion.

In general, the attitude had been that the ten previous Presidents had merely been the presiding officers of Congress, holding an office we might now call Speaker. Indeed, the President under the Constitution doesn't "preside" over anything definable, although the Vice-president clearly presides over the Senate, at least on the infrequent occasions when he is in the room. All of this would seem to be nit-picking wordplay by history hobbyists, except for one thing.

|

|

Lincoln raised the issue whether states who ratified the Articles of Confederation, among other documents, were bound in perpetuity to be members of the United States. |

Abraham Lincoln was having a hard time finding a reason to challenge South Carolina's right to secede, which was later depicted by the state as simply revoking its previous ratification of the Constitution in 1789. If they could join the Union, they could un-join the Union, so, Goodbye.

Not so, said Lincoln. When South Carolina ratified the Articles of Confederation in 1778, those Articles clearly stated the Union was to be perpetual, or at least the Articles uniting the colonies were to be so. Articles of Confederation: Article XIII. Every State shall abide by the determination of the United States in Congress assembled, on all questions which by this confederation are submitted to them. And the Articles of this Confederation shall be inviolably observed by every State, and the Union shall be perpetual; nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of them; unless such alteration be agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterward confirmed by the legislatures of every State. That sounds pretty perpetual to most readers, making the Constitution merely a clarification of details, or at most an amendment to the Articles of Confederation. There is a strong implication that the intent of Article XIII was to prevent individual states from making a separate peace with Great Britain, or Britain from claiming conquered territory was no longer American.There's no doubt the Articles do say perpetual and no doubt South Carolina signed them. However, it is equally certain that Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas did not sign the Articles. Six hundred thousand casualties later, this fine legal dispute was settled in Lincoln's favor, but not before the Gettysburg Address further muddled Constitutional Law by proposing in effect that the Declaration of Independence formed the basis for the Constitution. However, a speech at a ceremony hardly qualifies as a national ratification, and the Gettysburg Address did not achieve much acclaim for several more decades, suggesting later politicians were doing some special pleading, To include either the Declaration or the Gettysburg Address in a discussion of Constitutional intent is to ignore a lot of contemporary history. Many of the clauses and even some of the wording of the Constitution is taken directly from the Articles to the Constitution, whereas the claim tracing origin in the Declaration of Independence is based on the conflict between the two in the "All men are created equal" versus the later assignment in the Constitution of only 3/5 of a vote for slaves. The party of Thomas Jefferson can only make the claim that the Declaration made an assertion which was later overturned by the Constitution, only to be reversed again by the Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment. Only the Articles and the Constitution itself can claim to have been intended as a system of governance, with at least some attempt made to obtain general ratification, followed by long periods of conforming to them, to display even stronger ratification. It may be humanitarian, but it is not good history to assert that a Declaration is Law.

So now Philadelphia has two large, competing, institutions at either end of a long grassy Mall on Sixth Street, Chestnut to Vine. Each has a paid staff, busily organizing new points of view in competition for legal authority as well as visitors. One really must wish that Lincoln had found some other legal theory to justify military action. The Articles of Confederation, which were anyway not fully ratified until 1781, established a military alliance of thirteen otherwise fairly autonomous states. The Constitution, beginning with the words We, the People, created a nation of citizens, in 1788.

There's quite a difference, and the second was emphatically based on dissatisfaction with the first. It thus is a favorite theme for those who argue for a "living" Constitution, in which any change at all is legitimate if enough people clamor for it. My own view of this, if anyone cares, is that our Union is the only example in history where a number of viable sovereign states voluntarily and permanently surrendered their powers to become a "more perfect union". Many others have tried to do the same, starting with the French Revolution and continuing with the United Nations and the European Union. So far, every other attempt has been a failure. So I am very reluctant to see us tinker with the Constitution because the invisible balances are so subtle and largely unspoken. It may not be perfect, but so far it is unique in being the only one that seems to work. Such pious worship of a mystery seems to offend a lot of people, so let's get a little more pointed.

The greatest enemy of the Constitution at the time it was formed was Thomas Jefferson, the Ambassador to France at the time of the French Revolution, which he much admired. Jefferson was reluctant to confront George Washington, so his resistance to the Constitution was circumspect. However, he formed a political party with the main principle of opposing strong central government. One of the activities of his party was to start to celebrate July 4 as a National holiday and to downgrade the importance of Washington's birthday as one. There can be little doubt that Washington's birthday has been dropped from the national calendar and replaced by President's Day, while the celebration of July 4 continues to be an occasion for speeches and fireworks. John Adams engaged in a long correspondence with Jefferson after both had stepped down from the Presidency. While the two made their peace with each other on many subjects, Adams never forgave this celebration of the Declaration as a sacred text, when in fact he believed it had little to do with history and was outspoken in his scorn for its importance. One can only imagine the apoplectic speech Adams would give today if he could come alive and comment on the dilution of Washington's birthday with Lincoln's, diminishing the memory of both. And as for his scorn for dating the beginning of the Revolution to July 4, 1776, when in fact fighting had been going on at Lexington, Concord, Bunker Hill and other places for years, well. If it comes to a battle of documents, a respectable case can be made that the beginning of the Revolutionary War was in December, 1775 when the British Parliament passed the Prohibitory Act, effectively declaring war on the rebellious colonies, meanwhile dispatching a war fleet of several hundred ships to America to subdue us.

John Dickinson, Quaker Hamlet

|

| John Dickinson |

John Dickinson (1732-1808) would probably be better known if his abilities were less complex and numerous. It would have been particularly helpful if he had consistently remained on only one side of the important issues of his day. Born in a Quaker family and buried in a Quaker graveyard, he was for years a notable Episcopalian and soldier. He outwitted John Penn, the Pennsylvania Proprietor who was trying to keep Pennsylvania from sending representatives to the Continental Congress, by having the Pennsylvania representatives hold a meeting in the same small room of Carpenters Hall at the same time as the Congress. But he ultimately refused to sign the Declaration of Independence. Although he was the main author of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution which replaced it would not have been ratified without his idea of a bicameral Congress. Although he was Governor of Pennsylvania, he was also Governor of Delaware, has been the central figure in the separation of the two states. In fact, for fifteen years he was a member of the Legislature of both states. Dickinson seems in retrospect to have been on every side of every argument, but he was immensely respected in his time.

Two events seem to have been central in the organization of his life. The first was his education as a lawyer. At that time and for a century afterward, lawyers were trained by apprenticeship. Dickinson, however, studied in London at the Inns of Court for four years and was by far the most distinguished lawyer in North America for the rest of his life. Furthermore, he absorbed the principles of the Magna Carta and the approaches of Francis Bacon so thoroughly that he never quite got over his pride in his English heritage. Throughout his leadership of the colonial rebellion, he acted as a better Englishman than the English themselves. His demand was for American representation in the British Parliament, not independence from England. It would not be hard to imagine Dickinson standing before a firing squad, gritting the words of St. Paul, Civis Romani Sum.

His other pivotal experience was the Battle of Brandywine. Dickinson had been the organizer or chairman of the two main Pennsylvania military organizations, the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety and Defense, and the so-called Associators (today's 111th Infantry, the first battalion of troops in Philadelphia). Both of these particular names were a characteristic gesture to conciliating pacifist Quaker feelings. Nevertheless, when Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration, he did temporarily become so unpopular he resigned his military commands. A few months later, when General Howe landed at Elkton at the narrow neck of the Delmarva peninsula, Dickinson enlisted as a common soldier to defend the southern perimeter of the defense line Washington had hastily thrown up to defend Philadelphia. Shortly afterward, Dickinson's friend and neighbor Caesar Rodney made him a Brigadier General in charge of the garrison around Elizabeth New Jersey, but the Battle of Brandywine taught an important lesson. Little states like Delaware and Maryland could not possibly defend themselves witho

A Pennsylvania Farmer in Delaware

|

| John Dickinson |

It is difficult to have a coherent view of the mind of John Dickinson. Seriously offended by the Townshend Acts, he rightly perceived them to be the work of a few malignant personalities in British high places who would mostly soon be replaced. Later on, he refused to be troubled by the inconsequential Tea Act, which he appraised as a face-saving gesture of reconciliation, but more recent historical information demonstrates was more likely aimed at avoiding an unrelated vote of no-confidence in Parliament. Unfortunately, Dickinson was too remote from these events and additionally could not comprehend reckless hotheads among his own neighbors. Reckless hotheads in turn seldom comprehend the measured meekness of Quakers. In any event, although Dickinson played a major role in the Declaration of Independence, he refused to sign it when the time came, evidently sensing an opportunity to separate the three lower counties from Pennsylvania and its Proprietors. A few months later when the British actually invaded the new State of Delaware on the way to capturing Philadelphia by way of Chesapeake Bay, Dickinson enlisted as a common soldier and fought at the Battle of Brandywine. Obviously, he was seriously conflicted.

|

| John Dickinson's Farmhouse |

Dickinson had become internationally famous for twelve letters he had meant to publish anonymously. The Letters From a Pennsylvania Farmer were written about 1768 out of resistance to the Townshend Acts. Because the three counties which were to become the State of Delaware were then still part of Pennsylvania, many school children have become understandably confused about the actual location of the man who became governor of both states, simultaneously.

The causes of the separation of the two colonies are still a little vague. Delaware schoolchildren are taught the two states separated, but often report they didn't retain much information about why it happened. The Dutch and Swedes who originally settled southern Delaware were not sympathetic with Quaker rule, which could be seen as a reaction to their living here for generations as Dutchmen before William Penn arrived, but then saw the colony sold out from under them. As a further conjecture, there might have been friction with the Quakers over slavery, similar to the hostility of other Dutch settlers in northern New Jersey when William Penn purchased that area. This pro-slavery attitude resurfaced in both areas during the Civil War. One alternative theory which has considerable currency in Delaware is local dissension about Quaker pacifism during the Revolutionary War. On a recent visit to Dickinson's home outside Dover, a school teacher was overheard to instruct his flock that the Dutch Delawarians wanted to fight the British King, but the Quakers wouldn't give them guns. "We value peace above our own safety," was the unsatisfying response they received from the Pennsylvania Assembly. But that line of reasoning bumps up against Dickinson's role in local affairs, his ambiguity over the Declaration, and his vacillation in warfare. One would suppose the simultaneous Governor of both states would play a major role in the separation of the two.

|

| over Air Force Base |

Dickinson's plantation, quite elaborately restored and displayed, is tucked behind the Dover Air Force Base. Perhaps all that aircraft noise will discourage sub-development in the area of Dickinson's plantation and the rural atmosphere may persist for years. At the time of the Cuban missile crisis, your correspondent happened to be driving past, observing the sky filled with bombers, just circling and circling until the diplomats settled matters. Since eight-engine bombers are seldom seen around Dover, it has always been my presumption that they came from elsewhere to be refueled at Dover; but that's just a presumption. One of the pilots later told me he was carrying nuclear "eggs" and was completely prepared to take a long trip to deliver them.

To get back to Dickinson's wavering about the Declaration, maybe there was a good reason to waver. Joseph J. Ellis (in His Excellency, George Washington) relates that after the devastating British defeat at the Battle of Saratoga, Lord North made an offer to settle the war on American terms. In a proposal patterned after the concepts of the separatists in Ireland, America could have its own parliament as long as it maintained trade relationships with England. As an opening offer, that comes pretty close to what the colonists had been demanding. Governor Morris was active in disdaining this offer, although it is unclear whether he was acting alone or as the agent of others. The offer came too late to be accepted, but it might have shortened the war by six years, and we might now have a picture of the Queen on our postage stamps.

REFERENCES

| His Excellency: George Washington: Joseph J. Ellis: ISBN-13: 978-1400032532 | Amazon |

| Letters From A Farmer In Pennsylvania To The Inhabitants Of The British Colonies (1903): John Dickinson: ISBN-13: 978-1163969533 | Amazon |

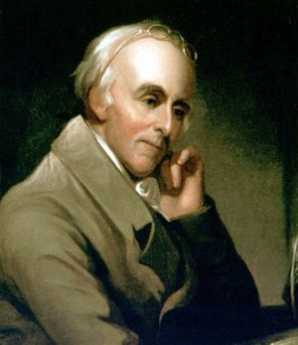

Pennsylvania Prison Society

|

| Duke of York |

William Penn, who spent considerable time in British prisons, established a penal code for his new colony which largely swept away the draconian punishments established by the code of the Duke of York. Until as late as 1780, jails were mainly confinement hotels for debtors, prisoners awaiting trial, and witnesses. For actual punishment, the methods were execution and flogging. Penn's Code for Pennsylvania restricted execution to the crime of murder, and flogging to sexual offenses; everything else was punished by fines and imprisonment. Hidden in this code, of course, was the need to invent and construct prisons to service the imprisonment. It would take over a century to address this need, and Philadelphia still has not completely caught up with the need for more prison cells. Without a prison system, the Penn code was impractical, and the colonial penal code retrogressed toward floggings, pillories, and hangings after Penn's death.

|

| Dr. Benjamin Rush |

In colonial Philadelphia, the main prison was on Walnut Street, with sixteen cells. A neighboring Quaker, Richard Wistar, started a soup kitchen in his own home, taking the soup over to prisoners. By 1773, he had established the Pennsylvania Society for Assisting Distressed Prisoners, which was unfortunately disbanded by the occupying British Army in 1777. In 1783, Dr. Benjamin Rush with the assistance of Benjamin Franklin, Bishop White, and the Vaux family, founded the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, which after a century changed its name to the Pennsylvania Prison Society. The Prison Society believes it is the oldest continuous non-profit society in America.

|

| Eastern State Penitentiary |

The Prison Society has had several major changes in direction. The original concept was to substitute public labor for imprisonment, a less costly arrangement than imprisonment while avoiding a return to floggings and dismemberment. However, the degrading sight of prisoners in chain gangs caused a public outcry, and the approach was abandoned. In the spirit of the French and American revolutions, loss of liberty was seen as the greatest punishment conceivable. Added to this was the Quaker concept of inspiring remorse through silent meditation, and the eventual outcome was the construction of the Eastern State Penitentiary on what was then called Cherry Hill. In 1823, it was ominous that Eastern State Penitentiary was the largest structure in America. Although the concept was widely admired and imitated, the prolix Charles Dickens took a violent dislike to the idea of never talking to anyone, and led a reversion away from penitentiaries back to simple prisons. In the days before Alzheimers and schizophrenia were well characterized, the spectacle of massive recidivism was added to the rumor that protracted solitude led to insanity.

|

| Catherine Wise |

From Catherine Wise the Communications Director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the Right Angle Club recently learned that the current evolution of the American penal system has led to a steady state, but a troubled one. There are 2.2 million inmates in American prisons today, more than any other nation including Russia and China. Of these, 75,000 are confined in Pennsylvania, 9,000 in Philadelphia. Recidivism is 67%, the cost is $31,000 per year per inmate, the majority of inmates have been involved with illicit drugs, a growing number are infected with HIV and Hepatitis C, mental illness runs around 20%. The cost of incarceration is growing faster than the cost of either education or healthcare for the community. Prison overcrowding is extremely serious, the programs for managing parole and integration back into society are weak and underfunded. Eighty percent of the inmates are non-white, most prisons are located in remote regions too far for easy visiting, medical care in prison would not seem at all acceptable in general society. The Prison Society has no difficulty finding projects which are urgently needed. Just for an example, take the peculiar prison statistics; it really seems improbable that only 9,000 of the 75,000 Pennsylvania prisoners are in Philadelphia. Then reflect, NIMBY, that no one wants a prison or its visitors near his home, except areas of rural poverty welcome the employment a prison brings. Reflect for a moment that "jails" are paid for by local county taxes and contain prisoners with less than two years to serve. "Prisons" are paid for with state taxes, and contain those sentenced to longer than two years. Finally, add the fact that nonvoting Philadelphia prisoners in rural prisons are counted by the census as residents of the rural area for the purpose of distributing legislative and congressional seats. The rural politicians love the system, the urban neighbors love to be rid of the prison environment, but the prisoner families can't visit the prisoner. Who cares? Who even notices?

During the first World War, Quaker interest in prison matters was greatly stimulated by the imprisonment of many Quaker conscientious objectors to the wartime draft; since that time prison conditions have again become a central interest of the religion. It's hard to prove but is confidently asserted, that violence and mistreatment of prisoners are appreciably less in Pennsylvania than the rest of the country, California for example. In any event, The Pennsylvania Prison Society is a particularly effective advocate for humane treatment because of credibility achieved over two centuries, with newspaper editors on its board, and sympathetic affiliations with the legislative judicial committees. It knows what it is talking about, as a result of over 5000 annual prison visitations, and it has served the prison administrative corps by performing volunteer work, accepting contracts for parole projects, arranging bus trips for prisoner families to remote prisons, and working for improved funding for prisons. At the moment, there are six highly imaginative bills before the Pennsylvania Legislature, devised and researched by this outside organization with credibility, and political clout. Although the Society takes an occasional contract for a project, it is itself entirely funded by outside contributions, and because of occasional adversarial situations, asks for no funds from the state. Even the contract funds have been questioned, and are only accepted when the working relationships fostered are more useful for the prisoner clients than any co-option which might result.

One final word about medical care in prison. It's not as good as medical care for non-prisoners, and unfortunately it probably never can be. The remote rural location of prisons makes it difficult to obtain physicians and nurses, regardless of wage levels. It's dangerous to be around prisoners, as any guard will tell you, and it's more dangerous to be in control of narcotics amidst a population of addicted convicts. Malingering is nearly universal, both to obtain desired drugs and to spend "easy time" in the infirmary. Many prison escapes are engineered around the necessarily weakened security of the medical system. The prison budgeting system has all the rigidity and weaknesses of any governmental medical system, and in this case, it's run far out of sight of the public. Even the bureaucrats in charge are victimized by other bureaucrats. The average duration of incarceration in Pennsylvania is longer than in most other states; the prisons have to keep mental patients because the mental hospitals have all been closed. Fifty years ago, when there was no place to put a non-criminal with tuberculosis, he was put in jail. The parole system is underfunded, there is not nearly enough community support to absorb ex-con. Behind all this is a shortage of prison facilities. The legislature has got itself into a position that if it moved more prisoners into the outside, more prisoners would just fill the vacancies, costs would go up, and things wouldn't look much better. Only after the backlogs have been absorbed, would there be much visible effect.

Parliamentary Procedure (1)

|

| John Adams |

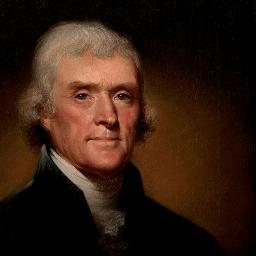

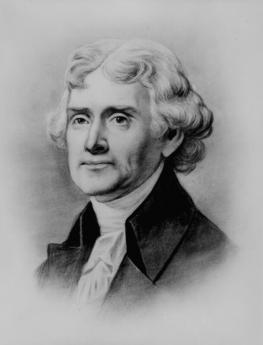

The Constitution provides that the Vice President of the United States shall be the presiding officer of the Senate. Accordingly, during the Presidency of John Adams, from 1797 to 1801, Thomas Jefferson was the presiding officer of the U.S. Senate, down at 6th and Chestnut Streets. According to recent books by Ellis, McCullough and others, it must have been an exciting experience to preside over that particular Senate.

Just what was running through Jefferson's mind during that formative time of Senate procedure is largely left to conjecture. We hear it said that Senate debate was rambling, raucous, and sometimes physical. Since Jefferson himself was the most controversial person in the room, his rulings from the chair may well have been resisted. In any event, Jefferson proceeded to publish the first American Manual of Parliamentary Practice,

|

| Thomas Jefferson |

patterned after the rules of procedure of the British parliament. An uncut copy of this book is still on the shelves of the Philadelphia Atheneum, a block away. Its contents can be summarized as sensible elaborations of two basic rules: the deliberative body only takes up one topic at a time (discussion of anything which wanders from that topic is ruled non-germane), and the rights of the minority are to be respected. Since America had just concluded an eight-year war with England, it is a little surprising that the behavior of the English Parliament would be considered something to imitate, and by Thomas Jefferson, of all people. It is vital for any deliberative body to have a set of rules, agreed in advance, about how to conduct debate and reach a conclusion. Controversy can get pretty heated at times, and it is then too late to be making rules which might favor one side or the other. Establishing rules in advance is if anything more important than what those rules say. Jefferson was thus quite right in publishing such rules, with the intention that the first act of any newly elected group would be to adopt the rules in the book as the agreed standard for whatever happens to come up later. The uncut version at the Atheneum is symbolic; you don't have to keep discussing procedure if the procedure is agreed.

|

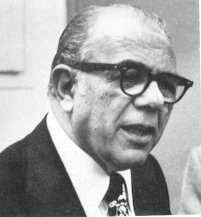

| General Henry M. Robert |

General Henry M. Robert wrote a revised version of Jefferson's rules in 1876, familiarly known as Robert's Rules of Order, which now govern the U.S. Congress. The main difference was to accommodate the creation of expert committees--on Ways and Means (taxes), Foreign Relations, health, etc, as the business of Congress grew more complex, and Congress met for longer and longer periods of time. Roberts Rules have thus become a special-purpose rule-book, and bodies like the American Medical Association or the American Bar Association, which meet for short periods yearly, find it more appropriate to substitute the use of "reference" committees. A reference committee is sort of a jury, intended to be a representative sample of the larger body, which is selected by the presiding officer to sort out a large amount of business and facilitate debate by the larger group as a whole. A reference committee system is better addressed by rules of order written by Mrs. Sturgis or Dr. Davis, than the more famous one by General Robert.

Underlying these seemingly dry technical issues is the struggle of an overburdened large group

|

| AMA |

to learn what its own collective opinion is, and to see that it is properly stated. As the agenda grows, it is necessary to designate smaller reference committees to hear testimony and present it fairly to the full convention when it assembles later. The referenced committee makes recommendations, but the full body reserves the decision to itself. In this way, the American Medical Association can make several hundred complex decisions in a week, almost universally recognized as representing the current opinion of the whole Association. Every few years, a decision is reversed, but remarkably seldom .

Eventually, a complex agenda grows to the size where a deliberative body must delegate a certain amount of power to experts, and the

|

| U.S. Congress |

U.S. Congress is well past that point already. It must consider an average of 25,000 bills per session. The typical state legislature considers an average of 10,000 bills; without a set of rules, nothing can be accomplished within such an overburdened agenda. No one surrenders power easily, and Congressmen are correct to insist that a republic elects the specific people it wants to see making the decisions, and lets them organize their own process. Therefore, General Robert describes the intentionally obscure rules which have evolved to govern the delegation by the elected members, of specific matters to specific committees of its own members. To put it bluntly, some handsome extrovert who happens to have got himself elected to Congress can be assigned to some unfamiliar topic and expected to learn what it is all about, with his power constrained until he does. Rule by seniority makes a lot of sense in such a situation, although obviously, some learn faster than others. Accordingly, the deliberative body must have rules which assist the process of weeding out chairmen who acquire seniority faster than they acquire expertise, while at the same time sympathizing with the difficulties all members regularly experience, publicly thrust into unfamiliar topics. Most smaller deliberative bodies do not need the rules which Robert's have evolved to manage seniority difficulties without opening the gates to ruthless power manipulators, unfortunately, but commonly an over-represented group in politics.

|

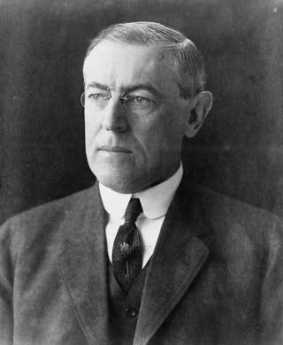

| Woodrow Wilson |