5 Volumes

Invaders of Pennsylvania

For a peaceful state, Pennsylvania has suffered many invasions. It's all been one-way; Pennsylvania has never invaded anyone else.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

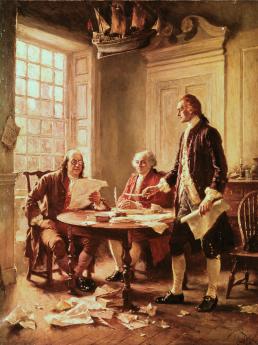

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

Causes of the American Revolution

Britain and its colonies had outgrown Eighteenth Century techniques of governance. Unfortunately, both England and America lacked the sophistication to make drastic changes smoothly.

On the timescale from 1492 to the present, 1776 lies about half way. Somewhere along that timescale, in the two decades after the French and Indian War, the British North American colonies woke up to their emerging destiny of eventually becoming larger and stronger than the home country. In itself, that was no reason to break apart, and the middle, or Quaker, colonies did largely adopt an "If it ain't broke don't fix it" attitude.

New England felt it had more serious maritime and manufacturing grievances however, and the Old Dominion of Virginia was agitated by land speculators who chafed to put stakes in Ohio land, on the far side of the Proclamation Line of 1763. It was probably only a matter of time before the Yankees and the Cavaliers had a collision with a rather obtuse and arrogant monarchy in London. Although they could scarcely be expected to recognize it fully, Britain/Pennsylvania relations after 1755 were a contest of possibilities.

The British government would surely become more enlightened about its colonies if the middle (Quaker) colonies just continued to remain placid. But very likely, immigration of non-Quakers and non-Englishmen might make the Quaker colonies less loyal and more combative, tempted to join with neighboring colonies in a unified rebellion. It was the task of the hotly beleaguered New Englanders to win over the Quakers quickly, while Burke and other Whigs in Parliament tried to win the ministry before a show-down was forced. Hotheads, however, won the race.

But the hotheads had some help from general historical circumstance. New England and Virginia had experienced comparatively little threat from the French, the Spanish or the Indians in the Eighteenth century; Pennsylvania got it worst, so it valued protection more. Add to that the pacifist Quaker influence, and the result was Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware were least ready to abandon British protection but were so economically important that revolt was impossible without them.

Enlisting the Quakers and the religious Germans into starting a war was a near-impossibility. The Scotch-Irish and others under the political leadership of Benjamin Franklin were more instinctively combative, but Franklin their leader was staunchly pro-British right up to a few months before the Declaration of Independence. It took the arrogance of a few swaggerers in the British government to humiliate Franklin in public, but that proved enough to do it. Everybody was telling Franklin he was the most wonderful genius alive; one can scarcely blame him for believing it a little. Forty minutes of vitriolic, witty, malicious public snottiness in front of Burke, Voltaire and the assembled aristocracy was just about too much for the fat old, gouty old -- most remarkable man then alive.

After that, it was going to be war.

FORCES AT WORK

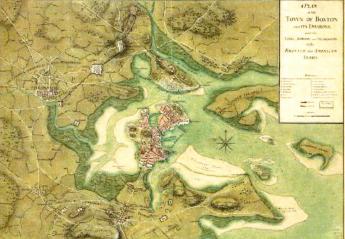

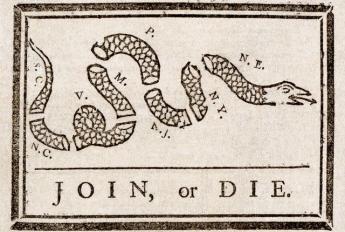

Three Different Ways of Looking at the American Revolution. If you are a resident of nearby Boston, the American Revolution began on April 19, 1775, at Lexington and Concord for reasons having to do with smuggling and tea. If you live near Philadelphia, the chances are fairly good you believe the Revolution began on July 4, 1776, because Admiral Howe attacked us. What's this all about? The colonies had fought the French and Indian War loyally together, with George Washington at Fort Necessity and Ben Franklin supplying wagons to General Braddock with his own money, against the hated French and their Indian allies, English colonists fighting off the enemy, side by side from 1754 to 1763, even back as far as traveling together to the Albany Conference in 1745. Ben Franklin drew the first newspaper cartoon, Join or Die, at that time, and first proposed an alliance of the thirteen English colonies with the homeland. The Quakers would probably still dominate Philadelphia, if they hadn't chosen religious consistency over the dictates of power. And yet a few years later the British were chasing gunpowder stores around the countryside. The British wanted the Americans to help pay the cost of their own defense, but we were all Englishmen, together, and everybody wants something for nothing. New Englanders wanted a negotiated arrangement like Ireland or union like the Scots; these were only technical details.The slogan aimed at representation, not independence. "No taxation without representation" for English-speaking colonists. Eventually, they hoped for parliamentary membership. They were mainly fighting against mercantilism using taxation as a weapon to fend off taxes while they remained English settlers. Franklin wanted a little more, moving the capitol to America because it was biggest, and he nursed this view until King insulted him in person,a few weeks or months before he grudgingly returned to America to help lead the Independence movement.

But this is the story of the forming of the Constitution, and in the fight to remain untaxed, English settlers got left behind and will be left to drift along. Got left behind by the Treaty of Westphalia. Everyone hates to be persuaded of something which hurts his self-interest, and Westphalia said the land became private property if the King had the exclusive right to adjust the borders, and by implication the local religion. That may have been useful in dealing with Indian lands, but in the sixteenth century, people took their religion pretty seriously. That was a serious matter, and it was made worse for Protestants as a consequence of Catholic activity in which Protestants played no role. Even worse, it was accepted by an English King who was German about whom Episcopal Englishmen had some reservations. And still worse was to see German Hessian soldiers about to do most of the fighting arriving in the troop transports, paid for by a German King, enforcing a law most of them didn't understand which had unexpected twists to it which sounded like the fight they ware already fighting about taxation without representation. Remember, Ben Franklin only had a second-grade education, and most of the colonists couldn't read and write. There were only a handful of lawyers in America, and most of them had a conflict of interest about this subject, which was cataclysmic in its sweeping implications. The logic of the new German law which only a few lawyers could follow sounded like a trap. The lawyers back in England at the Inns of Court might explain it, but the essence was that rebellion was punishable by hanging, while Independence was settled by treaty. The colonists might not understand how they got into this fix, but the new legal situation created a much worse punishment for rebellion than for Independence, and hence a strong incentive to prefer Independence. Admiral Howe was only 90 miles away with dozens of warships and hundreds of troop transports, and the Continental Congress was in Philadelphia with the power to make a choice. The Germans had just experienced a large wave of immigration, more German soldiers were sitting in the transports, anxious to obey the orders of a German King, which started as a law passed by other Germans without a vote by any of the colonists affected, starting fight a war about taxation without representation, which hardly anyone had the education to understand. It was, so to speak, a perfect storm. We came very close to losing that war, so after three centuries it is still true: Whether it was the League of Nations or the United Nations, or changing the Health System -- you have a hard time convincing the American public that it's a good idea to follow he decisions of non-American leaders. If the idea was foreign, and particularly if control is left in non-American hands it's going to be a hard job persuading Americans to vote for it. england

Whatever Was George III Thinking?

|

| George III |

Two troubling questions persist long after the American Revolution has mostly faded into the past: Why was New England so much more rebellious than the rest of the colonies? And, whatever was George III thinking when he blundered into losing an empire? No doubt, he would have answered in a different, unreflective tone in 1776, but the following is what he had to say about it after the war was lost. He seems to emerge as a far more literate and reflective person than the colonists believed of him.

"America is lost! Must we fall beneath the blow? Or have we resources that may repair the mischief? What are those resources? Should they be sought in distant Regions held by precarious Tenure, or shall we seek them at home in the exertions of a new policy?

"The situation of the Kingdom is novel, the policy that is to govern it must be novel likewise, or neither adapted to the real evils of the present moment or the dreaded ones of the future.

"For a Century past the Colonial Scheme has been the system that has guided the Administration of the British Government. It was thoroughly known that from every Country there always exists an active emigration of unsettled, discontented, or unfortunate People, who fail in their endeavors to live at home, hope to succeed better where there is more employment suitable to their poverty. The establishment of Colonies in America might probably increase the number of this class, but did not create it; in times anterior to that great speculation, Poland contained near 10,000 Scotch Pedlars; within the last thirty years not above 100, occasioned by America offering a more advantageous asylum for them.

"A people spread over an immense tract of fertile land, industrious because free, and rich because industrious, presently became a market for the Manufactures and Commerce of the Mother Country. Importance was soon generated, which from its origin to the late conflict was mischievous to Britain, because it created an expense of blood and treasure worth more at this instant if it could be at our command, than all we ever received from America. The wars of 1744, of 1756, and 1775, were all entered into from the encouragements given to the speculations of settling the wilds of North America.

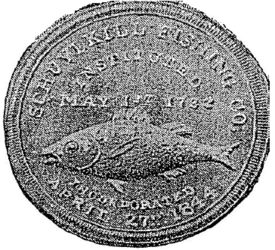

"It is to be hoped that by degrees it will be admitted that the Northern Colonies, that is those North of Tobacco, were, in reality, our very successful rivals in two Articles, the carrying freight trade, and the Newfoundland fishery. While the Sugar Colonies added above three million a year to the wealth of Britain, the Rice Colonies near a million, and the Tobacco ones almost as much; those more to the north, so far from adding anything to our wealth as Colonies, were trading, fishing, farming Countries, that rivaled us in many branches of our industry, and had actually deprived us of no inconsiderable share of the wealth we reaped by means of the others. This comparative view of our former territories in America is not stated with any idea of lessening the consequence of a future friendship and connection with them; on the contrary it is to be hoped we shall reap more advantages from their trade as friends than ever we could derive from them as Colonies; for there is reason to suppose we actually gained more by them while in actual rebellion, and the common open connection cut off, then when they were in obedience to the Crown; the Newfoundland fishery took into the Account, there is little doubt of it.

"The East and West Indies are conceived to be the great commercial supports of the Empire; as to the Newfoundland, fishery time must tell us what share we shall reserve of it. But there is one observation which is applicable to all three; they depend on very distant territorial possessions, which we have little or no hopes of retaining from their internal strength, we can keep them only by means of a superior Navy. If our marine force sinks, or if in consequence of wars, debts, and taxes, we should in future find ourselves so debilitated as to be involved in a new War, without the means of carrying it on with vigor, in these cases, all distant possessions must fall, let them be as valuable as their warmest panegyrists contend.

"It evidently appears from this slight review of our most important dependencies, that on them we are not to exert that new policy which alone can be the preservation of the British power and consequence. The more important they are already, the less are they fit instruments in that work. No man can be hardy enough to deny that they are insecure; to add therefore to their value by exertions of policy which shall have the effect of directing any stream of capital, industry, or population into those channels, would be to add to a disproportion already an evil. The more we are convinced of the vast importance of those territories, the more we must feel the insecurity of our power; our view, therefore, ought not to be to increase but preserve them."

In short, King George III of England sounds like a thoughtful, insightful man. Not a heedless, vindictive power freak as portrayed by frenzied revolutionaries, the King expressed a pretty reasonable assessment of his colonies. What he most lacked was a recognition that centralized if not one-man rule blocked growing expectations of greater self-rule; expectations propelled by an even bigger revolution, the Industrial Revolution. A Machiavelli or a Bismarck would have seen that Virginia mostly wanted access to Ohio land, while New England wanted maritime dominance; the Quaker colonies were quite satisfied with what they had. It would have been comparatively simple to play one region against another, giving each a little of what it wanted while encouraging cultural diversities which kept them jealous and separate. But His Majesty, yielding to the financial strains of the Seven Year War, and the urgings of his Teutonic mother, united thirteen of his colonies in common rebellion against taxes, military occupation, and high-handedness. The colonies did not want to unite; George III united them. Without unity, their rebellion had no chance.

Parliament Provokes a Revolution

In some medical circles, it is postulated that George III was psychotic, possibly suffering from an inherited rare condition called porphyria.

|

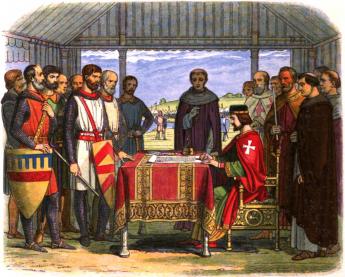

| Magna Carta |

That's pretty conjectural, but it is certainly true that his mother egged him on to be a real king, a real force reversing that steady decline in the Monarchy's personal power which began with the Magna Carta. By the time in question, however, so much power had already gravitated into the hands of Parliament that the King could not act in any major way without their consent. Even today, Cabinet Ministers are spoken of as King's ministers but are in fact appointed by leaders of the majority party in Parliament. Some in Parliament, like Edmund Burke, were almost persuasive in resisting the Ministry, urging colleagues to seek reconciliation with the colonies. George III did still retain the power to appoint his favorites to important positions and used this patronage extensively to control the country. Political party chieftains, on the other hand, retained and retain today the power to nominate the party candidate for Parliament in any particular district. The leadership thus selects the members of Parliament, who can, in turn, overturn the leadership only if they dare. Real decisions were largely in the hands of party chieftains, but perhaps to some extent, the Crown, depending on the Monarch's shrewdness in distributing patronage among the party chieftains.

Across thousands of miles of dangerous ocean, the English colonies had changed from the weedy wilderness in the Sixteenth century, into thriving and prosperous small civilizations in the early Eighteenth. Transatlantic communication did not substantially improve in that interval, but colonial population grew to over a million, many of them native-born in the colonies, with increasingly large numbers of immigrants from other nations. Loyalty to the Monarch inevitably declined. True, they spoke English, revered England, but many urgent local issues were difficult to administer at such a distance, encouraging a mentality of self-governance. France, by now at war with England on the Continent, operated on a grand plan of interior encirclement, from Quebec and and Great Lakes, down the Mississippi to New Orleans. The English coastal settlers needed peace with the Indians of the interior;

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

the French did not scruple to stir up massacres and Indian warfare. All wars are expensive, the French and Indian war particularly so. After defeating the French, the British were put to the protracted expense of building frontier defenses. Although the British were anxious to attract English-speaking colonists who would defend America for England, it was obvious some of the settlers were becoming very rich. Surely these people could not object to paying taxes for their own defense. In retrospect, it seems remarkably naive of the British to think it was that easy. Americans did not want to pay taxes because they did not want to pay taxes. They settled on the stance of "No taxation without representation" and like Franklin and the Penn family, many really believed in it. That slogan was particularly effective after it became apparent that Parliament wasn't about to give remote colonists reciprocal power in Parliament to interfere with affairs in the British Isles. With Parliament adamantly refusing to dilute its own power, "No taxation without representation" was a neat rhetorical box which meant, "No taxation." Contemporary English historians now throw up their hands in despair that so few members of George III's government had Burke's vision or even the normal wiles of diplomacy. But that understates the hidden political agenda. Parliament just pushed ahead with fairly nominal taxes, but they did so to curtail the independence of colonial legislatures.

The Stamp Act of 1764. It could be argued that Navigation Acts nothing new; earlier versions were first passed in 1651, intended to thwart Dutch trading. They prohibited foreign trade with the British home islands. After fifty years in 1703 similar restraints were extended to trade with the colonies, particularly molasses in the Caribbean area. No outcry was made as these restraints, aimed at retaining the Britishness of British colonies, were occasionally modified and extended over the next sixty years.

|

| Thomas Penn |

After a century in 1764, however, the Stamp Act was passed, producing modest revenue but imposing a crippling set of headaches by requiring special papers to transact private business. The uproar was enormous and legitimate, focused mostly on the tangle of red tape needlessly imposed. By shifting taxation from trade to paperwork transactions, suspicions were plausible that the Ministry was scheming something obscure. The Stamp Act was hastily repealed, even before Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Penn recognized its unpopularity and were still to some extent defending it in 1766. Franklin apparently saw the Stamp Act as an opportunity to appoint his friends as stamp agents. Local uproar in Pennsylvania was apparently orchestrated by William Bradford, who in addition to having been Franklin's former competitor in the printing business, was the owner of the London Coffee House at Front and Market. No other prominent colonial leader seems to have been involved in the agitation, and it is remotely conceivable that uproar originated with Bradford alone. More likely, Bradford was merely an opportunist in a genuinely popular uprising. With the familiar maneuvering characteristic of politicians, Franklin took popular credit for defeating the Stamp Act with some skillful criticism of it, while John Penn gained credit with the King for representing Pennsylvania's relative calm about it, compared with other colonies. In Pennsylvania at least, the uproar quickly subsided after the repeal of the Act.

The Townshend Navigation Acts of 1768.In 1766 the Grenville Ministry was replaced by that of Rockingham, then soon by Pitt, who were anxious to disavow the unpopular Stamp Act, but nevertheless needed colonial revenue, and needed a few unpleasant laws to prove that Parliament could not be intimidated by colonial squawking.

|

| Charles Townshend |

Charles Townshend, the brilliant, vindictive, Chancellor of the Exchequer then proposed taxes on glass, painter's lead, paper, painter's colors, and tea. The underlying political purpose of these taxes was to provide revenue for paying British colonial administrators directly, rather than depend on the Colonial legislatures to pay them. The Legislatures had long played a game of withholding payments, sometimes even the salaries of Judges and Royal Governors, when they disapproved of projects devised in London. The very predictable uproar provoked by the Townshend Acts propelled John Dickinson into prominence with a pamphlet called Letters From a Pennsylvania Farmer, which popularized the idea of "nonimportation", essentially a boycott of British products. Unintentional nonimportation was in fact the effect of the laws, clogging the ports with paralyzed trade goods. Rather than Dickinson's lofty principles, a little-noticed act of 1764, prohibiting the printing of paper money, paralyzed trade. There simply was not enough available coinage to pay these taxes, which finally pushed the primitive transaction system beyond its capabilities. From the viewpoint of modern economics, a heavy unbalance between imports and exports could not be rebalanced by flows of capital. The disastrous Townshend Acts were mostly repealed in 1770, but the British government was getting in deeper and deeper, discrediting itself at every turn. To retreat but still save face, they repealed all the taxes except the one on tea.

The Tea Act of 1772. To a certain degree, the uproar over the face-saving tax modifications on tea was a pretext for confused but radical colonists who were spoiling for a fight about difficulties they tended to personalize. The act actually lowered the effective taxes on tea, and at first Whig radicals were hard put to find a reason for outrage about lowering the price of tea. However, Bradford and his London Coffee House cronies (Mifflin, Thomson) were imaginative, and soon stampeded a mob scene in Philadelphia, where for a time the populace had seen nothing to get worked up over. Rush and Dickinson joined the chorus; the public feeling was stirred to a frenzy not easily reversed.

The really substantive issues involved were created by several years of Townshend Duties and other forms of import restriction. Laws to ensure the Britishness of British colonies created pleasant opportunities for colonial artisans and craftsmen, difficult hardships for importers. But these dislocations, whether welcome or unwelcome, firmly exposed the underlying truth that they caused all colonists to pay higher prices for goods. Adam Smith was not to publish his Wealth of Nations until 1776, so in this case the proof preceded the theory. The colonists were effectively asked to pay higher prices for everything, in order to increase Britishness and to billet soldiers they could not command. Once that cat was out of the bag, attitudes could never be the same. On the English side of the ocean, the question was framed as colonist unwillingness to contribute to the cost of their own defenses. The two slanted perceptions hardened to the point where arrogance confronted defiance, suggesting combat to both of them.

In the case of tea, taxes and import restrictions were intended to promote English tea over Dutch tea; in fact, they stimulated smuggling. Smuggling grew to a point that vast quantities of tea were stranded in the warehouses of the British East India Company, and trade balances of the British Empire were undermined. By reducing taxes, Parliament made East India tea cheaper than smuggled tea. Going perhaps one step too far, middle-men in the tea import business were cut out of the loop by appointing favored direct agents. In Philadelphia, those were Henry Drinker and Thomas Wharton. Bradford and his group immediately set about intimidating these merchants with threats to burn them out, and the sea captains who worked for them, with threats of tar and feathers. The age of Reason was leaving Reason behind.

Addressing The Proprietors' Dilemma

|

| William Penn |

DURING the century which elapsed after Charles II gave away Pennsylvania to William Penn, several hundred thousand people moved in and changed the place. Transformation of the wilderness explains why the terms of the grant seemed logical at one time, but proved almost impossible to manage at the time of the Revolution. The Penns with thirty million acres was the largest landholders in America but, in fact, by 1776 only five million acres had been sold in a century. The land they held was simply too much for one family to handle without an army, and although the original settlers were pacifists, the later ones were combative.

Charles II had written in the Charter that the Penns could have the land if they could maintain order there, retaining the legal right for the King to recover the land if they didn't. This fall-back provision certainly reflects some doubt about the ability of pacifists to shoot the necessary number of Indians, Frenchmen, and Spaniards. On the other hand, the motive for a King delegating away his authority in the first place became clearer when the Penns experienced severe financial strain defending the Northeast corner of the state against the Connecticut invaders. It furthermore helps us understand why Benjamin Franklin received such a cold reception when he was sent to London by the colonists to request the crown to reassert civil authority over the state. That did not necessarily imply stripping the Penns of their land; by this time, it was clear that the Penn Proprietors were mainly interested in selling it to someone. The charter of the King's grant included the offer to make William Penn a King; and although the offer was declined, the Penn Proprietors retained some degree of legal power to govern the territory. Franklin for all his persuasive power was, unfortunately, the one man Thomas Penn didn't want to see, because of the threat he had posed by raising a militia in King George's War, and later his expansiveness at the Albany Conference. And Thomas was a good friend of the King. The King didn't want these problems and particularly didn't want the expense. Ambiguities were, of course, shared all around. William Penn had quite shrewdly seen it was more sensible to treat the Indians decently than to fight with them, and cheaper too; the lesson was not lost on the British crown. But the French Kings posed a much larger world-wide threat to the British colony, finding for their part, it was rather economical to supply munitions to the Indians on the frontier and stir them up emotionally. The French and Indian War was a small component of the Seven Years War, which proved to be a costly adventure for both sides. Its local cost certainly overwhelmed the ability of one family to underwrite local governance in a large wartime colony, and it jeopardized the finances of the British Monarch to carry the rest. The resulting need to tax the colonies for their defense sent things downhill, eventually to the Stamp Act, the Townshend duties, and the Tea Tax. Everyone made lots of mistakes as the whole structure underwent revision, just as pacifists are certain will happen in any war. But when a pacifist utopian colony was prospering while successfully dealing with the Indians, it's all sort of a big pity.

|

| Thomas Penn |

With much to lose, the Penn family did pretty well with the resources at hand. By the time of the Revolution, three generations of Penns had divided up ownership shares of the Proprietorship. When French and Spanish ships were marauding the Delaware River, Benjamin Franklin the local printer took it on himself to organize a militia which persists today as the Pennsylvania National Guard, the Twenty-eighth Division. Franklin was suddenly a local hero to everyone, except to one man, Thomas Penn. Thomas was the dominant figure in the Penn family for many years and worried deeply about Franklin, a man who could stir up ten thousand armed volunteers with a poster proclamation. Such a man could mean trouble, as indeed events later proved to be the case.

John Penn was the Governor of the state, residing in his mansion on the Schuylkill called Lansdowne, doing his best to ingratiate the locals. He struggled to be diplomatic when arguing for the decisions actually made by his Uncle Thomas in London. Thomas Penn, on the other hand, was an important friend of the British Ministry, and a notable person in aristocratic England. As the Revolutionary War approached, the problem transformed into how to hold on to 25 million unsold acres, while remaining unsure who was going to win the impending war.

|

| John Penn |

The strategy the Penns adopted was to get out of the business of running a local government, as Franklin had proposed but in a different way. John Penn the Governor became a private citizen, just a local real estate agent. He took an oath of allegiance to the Revolutionary government, which in the chaos of the time was equivalent to becoming an American citizen. Meanwhile, other members of the family remained in England, ready to revise the arrangement if the British won the war. It was all fairly transparent straddling of the issues, which was only even remotely likely to be effective because of the enormous store of Penn goodwill built up over a century. In 1789 revolutionary France, for example, such sentimentality would not have delayed the tumbrels to the guillotine for five minutes.

Meanwhile, an unexpected difficulty was created. By withdrawing from control of the local government, the Penn family also withdrew from the defense of state borders against neighboring colonies. Under the circumstances, the Penns were afraid to appeal to the King, while the new government of Pennsylvania found the Articles of Confederation were merely a wartime tribal compact. The Articles stabilized boundaries mainly for the purpose of conducting a united war, and did not seriously contemplate a continuing judicial role for disputes between colonies. When the Revolution was finally over, the Penn Proprietors were not left with much of a bargaining position. The new State of Pennsylvania offered, and they accepted, about fifteen cents an acre to surrender their claims. In Delaware, they got essentially nothing for those three counties. Only in New Jersey did the Proprietors' claims remain durable after the new nation was established. The Proprietorship of East Jersey survived into the late 20th century, and the Proprietorship of West Jersey continues to return a small profit even today. The New Jersey curiosity is treated in a separate essay.

Monetary Causes of the American Revolutionary War

|

|

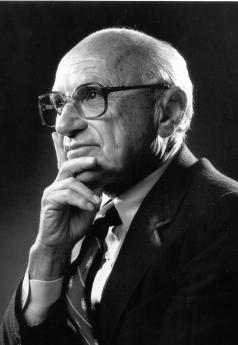

Milton Friedman The Father of Monetarism |

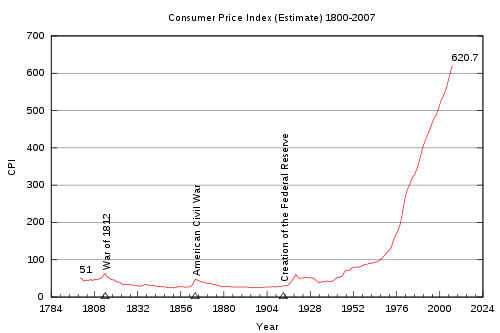

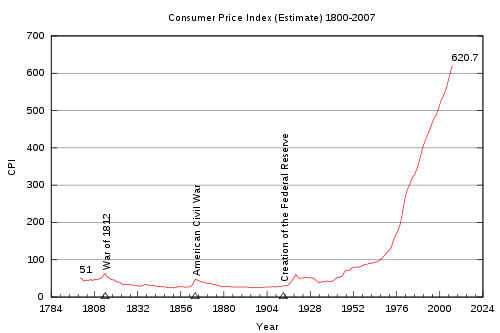

Milton Friedman won the 1976 Nobel Prize in Economics (more accurately, the Bank of Sweden Prize in Memory of Alfred Nobel), for generating controversial ideas made even more annoying to his professional adversaries by his matchless knack for attaching memorable slogans to them. A phrase in question is that "Inflation, always and everywhere, is a monetary phenomenon." Turned around, the converse emerges that the great deflation and depression of the 1930s was caused by a global monetary shortage. Then, to extend the same idea to the American Revolution, it could fairly be argued that inept British contraction of colonial coinage had a lot to do with provoking us to seek independence.

|

| French & Indian War |

Following the French and Indian War, the colonies experienced a major commodity depression which seems to have been caused by wartime shortages followed by post-war surpluses (associated with failure to adjust to the resulting financial confusion). In Milton Friedman's theory, it is the task of any government to maintain stable prices by balancing the amount of currency in circulation with the size of the gross national product. In 1770, the British Exchequer would thus have had to expand and contract the amount of currency in circulation pretty rapidly to maintain economic stability in the bumpy Colonial economy. Essentially, they had to ride a bucking broncho three thousand miles away. In the Eighteenth Century, there was no trace of understanding of the issues involved. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations was only published in the fateful year of 1776, for example. Even if the techniques for maintaining stable prices had been crystal clear, there was a thirty-day lag in communication across the Ocean, and comparable lags between the colonies, where different imports and exports were affected at varying times. So it is a little harsh to blame the British for the chaotic result, except to notice that strongly centralized, the trans-Atlantic government was by nature unsuitable for managing rapidly-changing problems, currency and otherwise. The British government had more than a century of experience that should have made that clear. That's what the colonists said, in effect, and their solution for it was Independence.

|

| George III |

If you believe Friedman, a shortage of coinage causes a fall in prices or deflation. To correct that, you need a central banker constantly fine-tuning the currency. But banking in the colonies was too rudimentary to consider such a thing. If you needed a mortgage, you went to a prosperous neighbor and borrowed directly from him. That was fine because prosperous colonists had limited opportunities to invest their money conveniently, except by loaning money to their neighbors. Indeed, local communities were knit together socially by the mutual assistance of successful farmers directly assisting their less fortunate neighbors. However, pioneer farming

|

| Depression-era Farm Family |

communities are far too unsophisticated to remain tranquil when problems arise out of abstractions. Suddenly and without apparent explanation, in 1770 there was no money for anybody to use, and the fellow with a mortgage on his farm couldn't make his payments even though he was otherwise entirely successful. His creditor himself than couldn't pay his own bills, and eventually, even the kindliest ones were driven to foreclose the mortgage. It was said to be common for a farm worth $5000 to be sold to satisfy a mortgage of $100. And in this way, many honest and once-prospering farmers were forced to walk past their old home, now owned and occupied by a formerly friendly neighbor. It all seemed bitterly unfair, no one understood what was happening, evil motives were readily suspected, and old religious and personal grievances were heightened. When the British finally imposed a total ban on paper money as well as a prohibition of the export of British coinage outside the United Kingdom, things became almost impossible to manage. Almost no one knew exactly what was going on, but everyone could see it was bad. The colonies rapidly deteriorated toward class warfare, which is what the division between Tories and Rebels was soon to become, with both sides quite rightly asserting they were not responsible, and quite wrongly asserting the other must be.

From a far distance, it can be readily perceived the primitive banking and transportation systems of that time were inadequate to respond to the rapidly changing financial problems of a global empire; and it can be readily surmised that many other non-financial issues of governance were similarly hampered by attempting to centralize control over vast distances. In that sense, the colonists were approximately correct in directing their indignation to the person of King George III, whose mother was constantly nagging him to "be a real King". He had the particular misfortune to be dealing with Englishmen, deeply aware of the hidden political agenda made possible in the 13th Century by the Magna Charta and made explicit in 1307, when Edward I agreed not to collect certain taxes without the consent of the realm. Essentially, Parliament placed taxation in the hands of the people, who consistently withheld consent until the king gave them just a little more liberty. This was the reason irksome micromanagement of the distant colonies was immediately countered with the cry of "No taxation without Representation" since membership in the House of Commons was a traditional and historically effective means to the end. But it was getting late for this solution. Maritime New England now wanted to go further than that in order to dominate Western Atlantic trade. Virginia and the rest of the South wanted to go all the way to Independence in order to exploit the vast empty interior wilderness of Ohio and beyond. But the Quaker colonies in the middle felt quite sympathetic with John Dickinson's advice to remain part of the Empire and make a stand for representation in Parliament. When the Lord Howe's British fleet appeared in lower New York harbor an immediate choice had to be made, and ultimately the Quaker colonies were swayed by Benjamin Franklin's embittered report of his mistreatment in Parliament, and his assessment that he could persuade the French to help us. However reluctant they were to resort to force, the Quaker colonies had to choose, and choose immediately: either flee as Tories to Canada, or stand and fight.

Mercantilism Dies Hard

|

| Mercantilism to Americans |

Whatever mercantilism was supposed to mean can be debated by captive college students; mercantilism to Americans is and was just a bad thing having to do with economics, mentioned only when the speaker is searching for an epithet. Our present understanding of the mercantilist term is that brutal government action, even war, was employed to benefit favored citizen merchants, while the economics of a whole nation of consumers was subverted toward enhancing state power. All of this rapacity was for the betterment of one nation at the expense of its neighbors, and at the expense of its colonies. The surprisingly vague but more modern term of fascism is often substituted, to denote evil uses of government to promote the interest of combined military and industrial elite, to the general disadvantage of everyone else. Because so many opponents of mercantilism were upset about specific forms of mercantilist activity, Adam Smith is associated with the idea that mercantilism was the opposite of international free trade, and the American founding father are associated with the idea that mercantilism embodied everything we disliked about colonialism. Some prominent 18th Century leaders constructed a body of theory to defend mercantilism and firmly established the idea that the whole approach was founded on long-discredited sophistry. In recent times, the only reputable economist to defend parts of mercantilism was John Maynard Keynes, who approved of the idea of emphasizing third-world exports in order to assist developing countries into a modern economy. Whatever is the underlying idea behind this mercantilist idea that has caused so much trouble, and includes so many disconnected features?

Allow an amateur theory. In my view the fundamental misconception underlying mercantilism was the idea that economic relations between individuals and nations are a zero-sum game; what I gain must be at the expense of someone else's loss. Almost every child believes that many or even most everyday transactions seem to confirm it, and vast multitudes of mankind believe it to the end of their days. But as part of the Industrial Revolution, the counter-intuitive realization began to spread that cooperative behavior, within limits, could sometimes result in all participants becoming better off, harming no one. Perhaps it was even a universal idea. Adam Smith popularized the idea that when two parties freely participate in the free trade of a marketplace, each one can come away from the trade feeling better off; one party would rather have the goods, the other party would rather have the money, and they trade. Multiplied millions of times, the expansion of free trade would enrich whole nations, even the whole world. George Washington may not have understood all that, but he did know that England was injuring him with rules about insisting British subjects must conduct all foreign trade in British sailing vessels, must not manufacture locally, must do this, must not do that.

Exporting was good, importing was bad, manufacturing was to be concentrated in the mother country, consuming was to be discouraged -- what was the unifying theory behind all this? It would seem to have been the gold standard. Gold was durable, and its supply was limited. It had certain undeniable advantages, but its overall effect was to restrain industrial progress. If the economy is constantly expanding, but the supply of gold is relatively limited, the price or value of everything will go steadily down over time. In George Washington's time that was particularly irksome with regard to the value of his plantation, and his vast land holdings of Ohio land. It was also true of everything else that was reasonably durable. If everything is measured in gold, and gold is limited, then the accumulation of gold is ultimately the only way to accumulate wealth. The English nobility who were profiting from the system might not perceive it, but the colonists could perceive it in their bones. Small wonder that modern banking, economics and innovative finance took root in the American colonies. If not first, at least most vigorously. Small wonder we had a revolution men would die for, while the British were merely annoyed and mystified.

Vast areas of Asia, Africa and the Middle East are still committed to the idea that the only way to get rich is to steal from others; since everyone wants to get rich, everyone steals. Someone has reduced this idea to a simple game theory called the Prisoner's Choice. If two prisoners tattle on each other, both will be severely punished. If both prisoners refuse to testify, both will go free. If one tattles and the other remains mum, the tattler will go free and the loyal comrade will get hanged. Reduced to its simplest level in a series of repeated games, the theory states that it's better for everybody to cooperate most of the time, but you must be willing to play tit for tat if the other party cheats. Be cooperative as much as you can, but never forget to wallop a cheater, and then forgive him later so he can have a chance to play nice. Lots of people will think you are a sucker if you play nice, so, unfortunately, it is necessary to retaliate -- swiftly and painfully -- when someone cheats. Centuries of American history are explainable with this simple game theory.

And not just with tribesmen and Nazis. When Winston Churchill finally realized that the Bretton Woods Conference was going to mean the end of the British Empire, he was almost tearfully plaintive with his friend Frank Roosevelt, but he said he understood.

And six years later, when Churchill's protege Anthony Eden invaded Egypt over the Suez Canal, Dwight Eisenhower the hero of the Normandy Invasion that saved England, suddenly turned nasty. England would immediately abandon that invasion, or Eisenhower would foreclose on British debts and ruin them.

That was the end of British colonialism, and in a sense, it was the final end of the Revolutionary War.

Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution

|

| Richard Arkwright |

The Industrial Revolution had a lot to do with manufacturing cotton cloth by religious dissenters in the neighborhood of Manchester, England in the Eighteenth Century. What needs more emphasis is the remarkable fact that Quakerism and the Industrial Revolution both originated about the same time, in about the same place. True, the industrializing transformation can be seen in England as early as 1650 and as late as 1880. The Industrial Revolution thus extended before Quakerism was even founded, as well as long after most Quakers had migrated to America. No Quaker names are much mentioned except perhaps for Barclay and Lloyd in banking and insurance, and Cadbury in candy. As far as local history in England's industrial midlands is concerned, the name mentioned most is Richard Arkwright, whose behavior, demeanor and beliefs were anything but Quaker.

He seems to have invented nothing, stealing the patents and ideas of others freely, while disgustingly boasting about his rise from rags to riches. Some would say his skill was in the organization, others would say he imposed an industrial dictatorship on a reluctant agricultural community. He grew rich by coercing orphans, convicts and others he obviously disdained into long, unpleasant, boring and unwelcome labor that largely benefited him, not them. In the course of his strivings, he probably forced Communism to be invented. It is no accident that Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto while in Manchester visiting his friend Friedrich Engels, representing reasonably well the probable attitudes of Arkwright's employees. What Arkwright recognized and focused on was that enormous profits could flow from bringing piecework weaving into factories where machines could do most of the work. Until his time, clothing was mostly made by piecework at home, with middlemen bringing it all together. The trick was to make clothing cheaper by making a lot of it, and making a bigger profit from a lot of small profits. Since the main problem was that peasants intensely disliked indoor confinement around dangerous machines, the industrial revolution in the eyes of Arkwright and his ilk translated into devising ways to tame such semi-wild animals into submission. For their own good.

|

| Charles Babbage |

Distinctive among the numerous religious dissenters in the region, the Quakers taught that it was an enjoyable experience to sit indoors in quiet contemplation. Their children were taught to submit to it at an early age, and their elders frequently exclaimed that it was a blessing when everyone remained quiet, enjoying the silence. Out of the multitude of religious dissenters in the first half of the Seventeenth century, three main groups eventually emerged, the Quakers, the Presbyterians, and the Baptists. Only the Quakers taught that silence was productive and enjoyable; the Calvinist sects leaned toward the idea that sitting on hard English oak was good for the soul, training, and discipline was what kept 'em in line.

|

| babbagemaq.jpg |

The Quaker idea of fun through daydreaming was peculiarly suitable for the other important feature of the Industrial Revolution that Arkwright and his type were too money-centered to perceive. If workers in a factory were accustomed to sit for hours, thinking about their situation, someone among them was bound to imagine some small improvement to make life more bearable. If such a person was encouraged by example to stand up and announce his insight, eventually the better insights would be adopted for the benefit of all. Two centuries later, the Japanese would call this process one of continuous quality improvement from within the Virtuous Circle. In other cultures, academics now win professional esteem by discovering "win-win behavior", which displaces the zero-sum or win/lose route to success. The novel insight here was that it has become demonstrably possible to prosper without diminishing the prosperity of others. In addition, it was particularly fortunate that many Quaker inhabitants of the Manchester region happened to be watchmakers, or artisans of similar trades that easily evolved into the central facilitators of the new revolution -- becoming inventors, machine makers and engineers.

The power of this whole process was relentless, far from limited to cotton weaving. When Charles Babbage sufficiently contemplated the punched-cards carrying the simple instructions of the knitting machines, he made an intellectual leap to the underlying concept of the tabulating machine. Using what was later called IBM cards, he had the forerunner of the stored-program computer. There were plenty of Arkwrights getting rich in the meantime, and plenty of Marxists stirring up rebellion with the slogan that behind every great fortune is a great crime. But the quiet folk were steadily pushing ahead, relentlessly refining the industrial process through a belief in welcoming the suggestions of everyone.

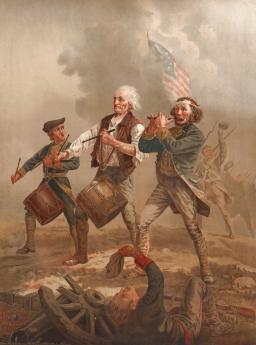

Pennsylvania: Browbeaten Into Joining a War

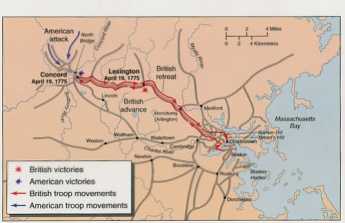

|

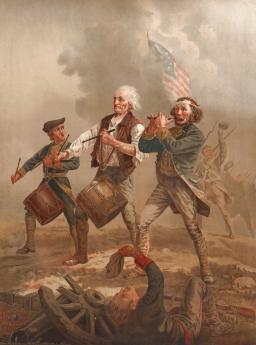

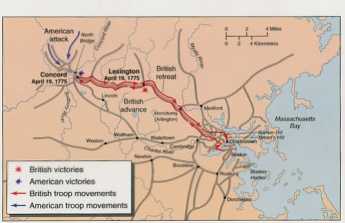

| Battle of Lexington |

In April 1775, the colonial militia were shooting it out with British soldiers at Bunker Hill and Lexington/Concord. If you include December 16, 1773, Boston Tea Party, Massachusetts had been fighting the British for almost three years before July 4, 1776. It had never been absolutely clear to Pennsylvanians just what they were fighting about in New England, beyond the fact that a considerable store of gunpowder was hidden in Lexington and Concord and British soldiers had been sent to confiscate it, along with those two trouble-makers, Samuel Adams and John Hancock. The militiamen behind the trees were just as British as the soldiers were, and their short slogan of fair treatment was to elect representatives to any Parliament which claimed a right to tax them. Snubbed by a high-handed King, they got his attention by shooting back when the King tried to enforce laws they had not had a chance to vote on. Seeing your neighbors shot soon clarifies your options. Other colonies, especially Pennsylvania, Delaware and South Carolina, were slower to anger about either taxation or representation, worrying more about the motives of unstable leaders in Massachusetts like Samuel Adams, and content to stall while British Whigs led by Edmund Burke and the Marquess of Rockingham tried to civilize the king's ministry. Besides, the British were not attacking Pennsylvania.

To be fair to the hot-headed New Englanders who were apparently stirring up so much unprovoked trouble, a better case could have been made against the heedless British ministry, and New England lawyers should have made it. Following the Boston Massacre, there was genuine alarm among lawyers like John Adams that King George was eroding historic legal rights achieved over several centuries, indeed, preferentially undermining them more for mere colonists than for U.K. citizens with a vote. The Navigation Acts of the British government, in particular, were offensive to American colonists; randomly chosen representatives on juries proceded to render them unenforceable with a wide-spread refusal to convict. They were employing William Penn's strategy of "Jury Nullification", and better acknowledgment of its legal history was sure to make a favorable impact on Philadelphia minds. Somehow, the Boston legal community felt this line of argument was too specialized to be effective, or else shared the alarm of their enemy the British Ministry that Jury Nullification in the hands of the public could be too hard to control. John Adams had made a particularly famous defense of John Hancock who was being punished with confiscation of his ship and a fine of triple the cargo's value. Adams was later singled out as the only named American rebel the British refused to exempt from hanging if they caught him. As everyone knows, Hancock was the first to step up and sign the Declaration of Independence, because by 1776 there was also widespread colonial outrage over the British strategy of transferring cases to the (non-jury) Admiralty Court. Many colonists who privately regarded Hancock as a smuggler were roused to rebellion by the British government thus denying a defendant his right to a jury trial, especially by a jury almost certain not to convict him. To taxation without representation was added the obscenity of enforcement without due process. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the newly created United States, ruled in 1794 that "The Jury has the right to determine the law as well as the facts." And Thomas Jefferson built a whole political party on the right of common people to overturn their government, somewhat softening it is true when he saw where the French Revolution was going. Jury Nullification then lay fairly dormant for fifty years. But since the founding of the Republic and the reputation of many of the most prominent founders was based on it, there may have seemed little need for emphasis of an argument any modern politician would seize with glee.

|

| Bunker Hill |

At that time, only a third of colonists were in favor of fighting about it, and a third was entirely opposed. Samuel Adams himself had written his supporters that it would be best to hold back until greater revolutionary support could be gathered. Unfortunately, in the minds of the British ministry, hostility had already escalated irrevocably when the Continental Congress in June 1775 created the Continental Army and dispatched George Washington to Boston to join the fight. This was probably the moment when war became inevitable in the collective mind of the British Parliament; a full year had passed since then. Regardless of Bunker Hill, the British were incensed by the creation of the Continental Army, and passed the Prohibitory Act, which declared that all thirteen colonies (belonging to the Congress) were renegades, their decision to raise armies placing them "outside the protection of the king". All American shipping was now subject to seizure, not just that of Massachusetts, as were foreign vessels engaged in American trade. News of this Parliamentary thunderbolt first came to Robert Morris through one of his ships, accompanied by news that 26,000 troops had been raised for an invasion of American ports. The British position was that all thirteen colonies had gratuitously formed a government and an army, and needed to be punished for such treason. Pennsylvania was no exception; the offending Continental Congress had met there, and Benjamin Franklin had represented both Massachusetts and Pennsylvania before Parliament. Confirmation of that particular British attitude toward them greeted Pennsylvanians when British warships promptly appeared in May 1776, to patrol the mouth of Delaware. Three cruisers exploring up the river were attacked by American galleys. In response, the cruisers sailed directly at Philadelphia until they were finally beaten back by citizen flotillas, supervised by Robert Morris and the Committee on Safety. Morris wrote to Silas Deane in Paris that war was probably inevitable. Far less tentatively, the British felt it had already been in progress for a year.

The British Ministry had probably been unreasonably hostile, but they were not unanimous and they were not fools. In response to colonial unrest up until these almost irretrievable events, the British were concentrating on depriving the colonists of arms and gunpowder, mostly avoiding direct violence; it seemed an effective strategy. During the Boston Tea Party, for example, British warships in Boston harbor merely stood by and watched the fun. Although gunpowder was a simple chemical, comparatively easy to make, it was less likely to blow up in your face if finely ground and milled in a major factory; for a real Colonial war it had to be imported. The British strategy had been: Take away their weapons, and they will capitulate. Unfortunately, that was not the response at all, since even loyal colonists felt they needed good gunpowder for hunting and self-protection. Gunpowder blockades and confiscations were going to be bitterly resented. Nevertheless, British patience with the colonists was probably only irretrievably exhausted in June 1775, when the Continental Congress formed its own army and Washington marched them to Boston. If Pennsylvania became convinced of that inevitability, the war was certainly on. After the naval battles right here on Delaware, what really became hard to believe was that -- only a week earlier -- Pennsylvania's moderate voters had soundly defeated the revolutionary radicals in an Assembly election.

Pennsylvania had indeed been far less eager to fight than Massachusetts and Virginia, but the more belligerent colonies felt they needed allies in order to prevail. In the Continental Congress Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against rebellion in the Spring of 1776; and in the May 1776 election where independence was the main issue, the Pennsylvania voters elected an Assembly 70% opposed to rebellion, including that eminent merchant Robert Morris. Some of the determined Massachusetts efforts to persuade the Mid-Atlantic colonies bordered on subversion, but Pennsylvania remained unmoved. Nevertheless, they could see a real danger of war and had approved Secret Committees to be prepared if it came. Robert Morris was ideal for covert activity and could be expected to keep the activity under control, along with Benjamin Franklin and several prominent merchants. Morris made no secret of his affection for England the country of his birth, or of his membership in the John Dickinson group which hoped economic pressures would suffice. When the Secret Committee chairman suddenly died of smallpox, Morris was then appointed a chairman. His personal integrity was widely respected; in several hotly contested elections, he was nominated by both the radicals and the conservatives.

It seems absolutely necessary to prepare a vigorous defense since every account we receive from England threatens nothing but destruction.

|

| Robert Morris: December 1775. |

The Secret Committee was charged with smuggling in some gunpowder, just in case. Several of the members agreed to ship arms and gunpowder in their own ships; there was no one else to do it. The decision to engage in treasonous gunrunning was greatly assisted by the unexpected appearance of two Frenchmen with aristocratic accents in a boat loaded with gunpowder, who proposed themselves as French counterparties in a major gunpowder and weapons smuggling network which did actually materialize. Just who sent them has never been made entirely clear, but later events make the playwright Beaumarchais a reasonable guess, acting as a secret agent of the French King. Beaumarchais the famous playwright had been caught in a police trap, and forced to act as a government spy; just whose agent he was is a little murky. The American merchants on the Secret Committee knew gun running was expensive for them; they all expected to be paid for dangerous work, so it was also profitable. And treasonous. If caught, there was every possibility of being hanged. Initially, the Americans all imagined the Frenchmen were simply in it for the money, and that is possible. Surprisingly, no one seems even to have speculated they were agents of the French government on a mission to stir up trouble against the English. Spies had surely informed the French King of approaching war, at least six months before the Americans knew of it. Since these two foreign shippers (giving their names as Pierre Penet and Emmanuel de Pliarne, and surely sent to spy) demanded to be paid in hard currency, Morris did send one ship with hard money to pay for munitions to be carried in its hold on the return voyage. But he soon devised safer payment approaches.

For my part I abhor the name & the idea of a rebel, I neither want or wish a change of King or Constitution & do not conceive myself to act against either when I join America in defense of Constitutional Liberty.

|

| Robert Morris: December 1775 |

Since he had agents and offices in most major foreign ports, Morris could arrange for the money to arrive independently of the cargo ships. Or better yet, send ordinary commodities on the outward journey and make a private profit on that, returning with munitions paid for by the "remittances" -- revenue from the other cargo. Money was also sent on other circuitous journeys and through other channels, particularly the discounted debt system he had earlier perfected when the paper currency had been prohibited. There was thus less incriminating evidence on the ship, and even if the ship burned or everyone got hanged, the money was at least out of the hands of the enemy. Secrecy was, of course, essential, this activity could be called treasonous, and it was most assuredly smuggling. When neutral countries were found supporting gunrunning, that assistance might well be called an act of war, so all nations prohibited it. In spite of his earlier reluctance about independence, Morris could easily see that gunrunning by the privateers of a recognized nation might be better protected by the conventions of war than exactly the same activity conducted by, say, brigands, profiteers or pirates.

Gunrunning was always seriously dangerous; Morris soon lost four ships, one by a mutiny of secretly loyalist sailors, and two were captured by unscrupulous American privateers. There would be some protection from hanging for gun runners as authorized combatants of a recognized nation. In retrospect, we can now surmise that Franklin was committed to independence, and was probably nudging his friend on the Secret Committee. John Adams could barely contain himself, openly and repeatedly. Washington was already outside Boston leading an army. The commitment had many levels.

In July 1776 Morris was called on to vote in Congress for the independence he always said he opposed. Caesar Rodney rode in from Delaware to deliver his state for Independence; now, Pennsylvania alone stood in the way. When the moment came, on the advice of Franklin, Robert Morris, and John Dickinson left the room to allow other Pennsylvania delegates to constitute a Pennsylvania majority, casting the state's vote for the war. Commitment to the war had many variants, even after the war began.

Reconsidering All Our Laws

|

| Common Law |

A KING who conquers a new country theoretically gains the chance to revise all its laws. However, thousands of years of experience demonstrate that those who are good at wielding the sword seldom have much interest in, or aptitude for, devising a legal code. Napoleon seems to have been an exception, and Alexander the Great was tutored by Aristotle, but most conquerers have been illiterate in the law. Therefore, earlier conquerors merely extended their native laws into additional territory or else left the whole business to a permanent priesthood of judges. In this way, an independent judiciary could survive unless, like Thomas a Becket or Thomas More, it grew stubborn about thwarting the wishes of the King. The concept of citizen rights more or less defined feasible limits to what the King was allowed to do. British law went still further, distinguishing between rights of the people and rights of the sovereign. It identified those few things even a King was not allowed to do, as well as those many things he alone must be able to do in order to govern. The latter were collectively called the King's Prerogative. Today, we would call it a job description.

|

| U.S. Codes |

Along those lines, the English Civil War had been fought, briefly transferring the power of Prerogative to Parliament, and incidentally clarifying some disadvantages of doing so. Americans, after fighting an eight-year Revolutionary War to be rid of a particular king, had developed a sentiment for eliminating all kings entirely. However, the memory of the English Civil War and subsequent abuses by the Cromwell Parliament restrained that impulse. The alternative idea grew of transferring sovereignty to the people, to be translated into action by their elected representatives in the Legislative branch. Although such sovereignty would be unlimited, the intermediate steps taken by the Legislature could be deliberately slowed down, and particularly worrisome actions might be tangled up in complicated steps of legal process by a vocal minority. Such a complicated system required an umpire, which Chief Justice John Marshall eventually positioned the Supreme Court to be. Conducting elections every two years was a simple way to allow the people to restrain its agents from the misbehavior of a more general sort. Since George Washington was confidently expected to be the first President, it was left to him to devise protections against presidential abuse, since he had notoriously and repeatedly expressed his intense dislike of kings. In modern times this system of checks and balances has only been severely tested once, in 1937. Immediately after winning a landslide re-election in 1936, Franklin Roosevelt nevertheless was slapped down hard by public outcry forcing Congress to thwart his Supreme Court-packing scheme.

|

| Sir Francis Bacon |

Such subtle, complicated ideas cannot be implemented by writing 6000 words on a piece of paper, and they certainly cannot withstand two hundred fifty years of subsequent nit-picking by dissenters, no matter how carefully crafted the 6000 words may have been. The complexity of the political system it describes would long ago have fallen apart without a million little accommodations and revisions, just as every other nation's constitution has done during that same period of time. And that fine-tuning process was made possible by starting with a more or less blank slate, with thousands of lawyers and legislators debating every particle of common law for more than a century. In 1787 it was decided to adopt English common law as a default position, and to invite a host of legislative bodies to debate and replace any part of it with a "statute". It was a laborious process. Measured by pages of law books, the volume of statutes only grew to equal the volume of common law by the time of the Civil War. The English common law was certainly a good place to start, having been created by Sir Francis Bacon two hundred years earlier as the legal equivalent of the Scientific Method; based on real, adversarial contested case decisions, a hypothesis was created, then tested, revised, and tested again. By actual count, one state legislature only enacted three statutes in the year before the Constitution was ratified; all its other activity was concerned with adjudicating disputes within the boundaries of the existing common law. But when the Constitution suddenly rearranged the balances of power in 1787, almost every sentence of common law had to be regarded as potentially requiring modification to reflect the new Constitutional rearrangements. During the first half century there existed great enthusiasm for almost all of the new Constitution except those parts which affected slavery, the fine-tuning was almost universally intended to strengthen it or repair some oversight. If it failed in some way, adversaries were quick to point out the flaws. In short, every lawyer in the nation was involved to some degree for a century in the process of re-writing the English common law for American purposes, in American circumstances, for the grander purpose of strengthening the American commonwealth.

|

| Federal Registry |

And everyone knows what happened next. The state legislatures who considered it normal to pass fewer than a dozen laws in a year started passing fifteen hundred in a year and kept it up for many years. Today, almost every state legislature considers more than a thousand bills and passes two or three hundred. Since the colonial legislatures passed few laws and spent most of its time adjudicating disputes about existing law, the character of the law changed as it gradually gave up adjudicating, stopped being like a court. The tendency of early law was to state principles to guide the judges. In recent times, our over-lawyered system specifies all imaginable conditions and exceptions in excruciating detail, so that our laws tend less and less to speak of "reasonable amounts" and more and more to define drunken driving, for example, in milligrams per deciliter of the defendant's blood. We have better measuring devices, so we measure. But who can deny that a legislature accustomed to making judgments itself, will more confidently rely upon the good judgment of courts, than a legislature which spends its time going to committee meetings to consider the testimony of experts, often never visiting a courtroom?

Our lawyers, who once enlisted the efforts of the entire profession for a century into refining the English common law into the American statutory law, are to be encouraged to extend equal effort into the process of turning off the faucet. Or possibly, having done such a good job at this assignment, seek another line of work?

The Origin of States Rights, a Rumination

ALMOST alone among the British colonies in America, Pennsylvania's western border was specified in the King's charter of the colony. It was "five degrees longitude west of the point where the eastern boundary crosses the Delaware" [River]; however, its actual location on the ground was not actually marked until 1784. It's a few miles west of the present city of Pittsburgh, located at the forks of the Ohio River, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers join. However, until 1784 it was not a certainty that this complex was within Pennsylvania instead of Virginia. The origin of Ohio is at the only major water gap in the North-South mountains, and the tributary rivers are fairly large. The three merging rivers thus form a nearly continuous water route along the base of the mountain range, from the Great Lakes south to Pittsburgh, or from the Chesapeake Bay north to Pittsburgh, and then to the Mississippi, going past the best topsoil farming land in the world. The forks of Ohio were the great prize of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, the place where young George Washington himself started the French and Indian War. To include these treasures, it seems vaguely possible that William Penn insisted on having the border of his state safely include the water gap at the beginning of Ohio. Perhaps not, of course, perhaps it was just a sense of tidiness on the part of the ministers of Charles II. The original document stated that the border was a hundred miles east of there, to match where Maryland ended. When the document was returned to Penn by the King's ministers, however, it had the new language.

The existence of this north-south termination of Pennsylvania began to take on a new significance when other states made claims for their land grant to extend to the Pacific Ocean, and the extensions collided with each other. Virginia then developed its territory to include modern Kentucky and West Virginia. That resulted in Virginia's land aspirations veering northward, to include the Ohio Territory west of Pennsylvania's fixed boundary. By the legal standards of the day, Virginia had a fairly good claim to all of the Indian territories, not merely to the west of Pennsylvania, but extending at least to the Great Lakes, perhaps farther. Maryland, Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts had conflicting claims from an infinite extension of their western boundaries. As a consequence, it was impossible to achieve ratification of the Articles of Confederation for five years. The various states involved were fearful of the creation of a combined political entity might result in a court which would be enabled to rule against their individual aspirations. The stakes were high; the land mass involved would be several times as large as England.

The person who finally broke this deadlock might well have been Robert Morris, who was disturbed that this inter-state dissension was injuring his ability to borrow foreign funds for the Revolutionary War. The internal negotiations took place under wartime conditions, and are poorly researched. No doubt some person deserves credit for bringing this wrangle to a close. Virginia had the strongest claim, New York the weakest. New York gave up its claim first, Maryland was the last, and Virginia the most disappointed. Pennsylvania, unable to make a claim, took the position that the land belonged to everyone, and eventually was mollified by getting a small notch of land extending to the Great Lakes at Erie. It must be noticed in passing that final resolution of the land claims came at the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolution. Benjamin Franklin, soon to become President of Pennsylvania, was the negotiator of the treaty which reflected Pennsylvania's position that the land belonged to all of us, right?

Even without these western land claims, Virginia was the largest and richest of the colonies, and rather easily adopted the attitude that Virginia would be the leader of the new United States. From their viewpoint, the preservation of states rights would enhance Virginia's leading the country. More or less immediately, the attitude of small states like Delaware hardened into resistance that this must not happen. Much otherwise inexplicable behavior also begins to make a sort of sense: the perverse behavior of the Lee family in the Continental Congress, the quarrels within George Washington's cabinet, the relocation of the capital and the dreams of the Potomac as the nation's main portal of transportation, the rise of Jefferson's political party, the obstructionist behavior of Patrick Henry, the Virginia domination of the Presidency for decades, and countless less famous episodes of history -- make more sense as residuals of Virginia's early land aspirations, than as defenses of slavery or philosophical convictions that states were somehow superior to nations. These suspicions are difficult to clarify and impossible to prove. The best way to see some substance to them is to imagine yourself in the Virginia House of Burgesses, politically connected and vigorous, able to imagine your descendants all inheriting a county or two of rich land as a remote consequence of a few glamorous deeds by their Cavalier ancestor.

The Personalities

John Head, His Book of Account, 1718-1753

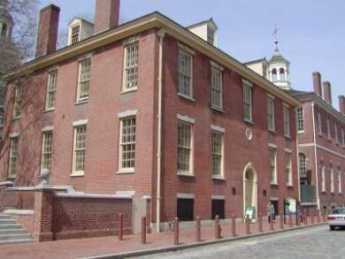

|

| American Philosophical Society |

Jay Robert Stiefel of of the Friends Advisory Board to the Library of the American Philosophical Society entertained the Right Angle Club at lunch recently, and among other things managed a brilliant demonstration of what real scholarship can accomplish. It's hard to imagine why the Vaux family, who lived on the grounds of what is now the Chestnut Hill Hospital and occasionally rode in Bentleys to the local train station, would keep a book of receipts of their cabinet maker ancestor for nearly three hundred years. But they did, and it's even harder to see why Jay Stiefel would devote long hours to puzzling over the receipts and payments for cabinets and clock cases of a 1720 joiner. Somehow he recognized that the shop activities of a wilderness village of 5000 residents encoded an important story of the Industrial Revolution, the economic difficulties of colonies, and the foundations of modern commerce. Just as the Rosetta stone told a story for thousands of years that no one troubled to read, John Head's account book told another one that sat unnoticed on that library shelf for six generations.

|

| Colonial Money |

The first story is an obvious one. Money in colonial days was mainly an entry in everybody's account book; today it is mainly an entry in computers. In the intervening three centuries, coins and currency made an appearance, flourished for a while as the tangible symbol of money, and then declined. Although Great Britain did not totally prohibit paper money in the colonies until 1775, in John Head's day, from 1718 to 1754, paper money was scarce and coins hard to come by. Because it was so easy to counterfeit paper money on the crude printing presses of the day, paper money was always questionable. Meanwhile, the balance of trade was so heavily in the direction of the colonies that the balance of payments was toward England. What few coins there were, quickly disappeared back to England, while local colonial commerce nearly strangled. The Quakers of Philadelphia all maintained careful books of account, and when it seemed a transaction was completed, the individual account books of buyer and seller were "squared". The credit default swap "crisis" of 2008 could be said to be a sharp reminder that we have returned to bookkeeping entries, but have badly neglected the Quaker process of squaring accounts. As the general public slowly acquires computer power of its own, it is slowly recognizing how far the banks, telephone companies, and department stores have wandered from routine mutual account reconciliation.

|

| John Head's Account Book |

From John Head's careful notations we learn it was routine for payment to be stretched out for months, but no interest was charged for late payment and no discounts were offered for ready money. It would be another century before it became routinely apparent that interest was the rent charged for money and the risk of intervening inflation, before final payment. In this way, artisans learned to be bankers.

And artisans learned to be merchants, too. In the little village of Philadelphia, chairs became part of the monetary system. In bartering cabinets for the money, John Head did not make chairs in his shop at 3rd and Mulberry (Arch Street) but would take them in partial payment for a cabinet, and then sell the chairs for the money. Many artisans made single components but nearly everyone was forced into bartering general furniture. Nobody was paid a salary. Indentured servants, apprenticeships trading labor for training, and even slavery benignly conducted, can be partially seen as efforts to construct an industrial society without payrolls. Everybody was in daily commerce with everybody else. Out of this constant trading came the efficiency step for which Quakers are famous: one price, no haggling.

One other thing jumps out at the modern reader from this book of account. No taxes. When taxes came, we had a revolution.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1517.htm

Tom Paine: Rabble-Rousing Quaker?

|

| Thomas Paine |