3 Volumes

BANKS REDEFINED

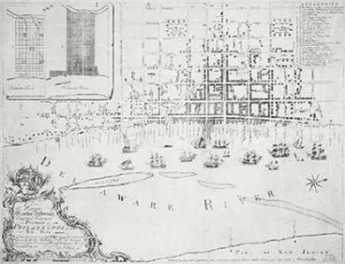

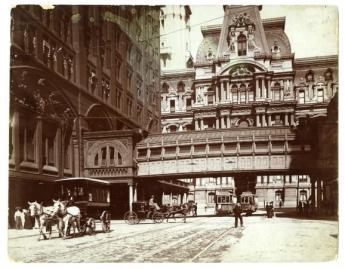

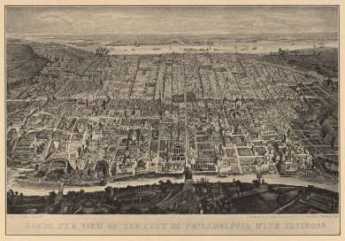

American banking was invented in Philadelphia. The banking center of America has moved away and changed in extraordinary ways but the foundations remain.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Philadelphia Economics

economics

Cultural Imperialism

|

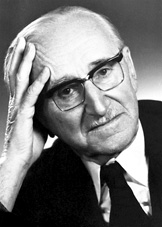

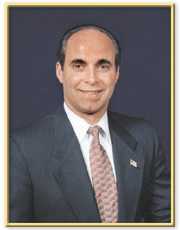

| Herb Kelleher |

Southwest Airlines announced it would begin flight service at Philadelphia International Airport in May 2004. Philadelphians sort of know the airport is in Southwest Philadelphia, many of us even remember getting a driver's license at the Division of Motor Vehicles, when it was located in the Southwest. But those Texas cowboys who run Southwest Airlines mean to give a whole new meaning to Southwest Philadelphia, planting the red-hot Texas branding iron there. For more than a century, the cultural flow has been the other way, from Philadelphia toward Texas. Sam Houston came from a family that still owns much of Chestnut Hill, and Dallas is named after a place near Scranton. We have strong historical links with what is apparently now pronounced "Takes-us", but somehow that's been lost in the Hollywood tradition of the cowboy, which, come to think of it, was invented by socialite Owen Wister of 7th and Spruce Street, and spread farther and wider by Zane Grey, the Philadelphia dentist.

Herb Kelleher the founder of Southwest Airlines, presents almost a caricature of the Texas cowboy. He looks like Gary Cooper, he drawls and brags, boasting cheerfully about just about everything his company does. He is planning to bring hordes of out-of-town visitors because of his tremendously cheap fares, and publicly told the Director of the Visitor's Information Center that he had a better plan on doubling his staff, right away, because crowds of tourists are coming. His airline is fairly new, but it ranks first in service, and highest in quality, number one in baggage handling. Stupendous is a word frequently used. And then flashes of the shrewd CEO underneath it all creep out. They've had 31 years of profitability, and are the only American airline with an investment-grade bond rating. At 26%, they have the highest return on investor dollar of any member of the S & P 500. They have customer satisfaction, and the best' employee satisfaction in the world'. Maybe he laughs at his own jokes a little too much, maybe he boasts too much, but there's an answer to that, too. He quotes Dizzy Dean -- "It ain't bragging -- if you really done it."

|

| texas |

It's impossible not to like this guy, and the admiration grows when you hear his business plan. His airline initially confined itself to Texas because the state is large enough to be able to fly many flights entirely within the state boundaries. That way he escaped interstate regulations and demonstrated enormous cost savings from not having to comply with all the federal red tape. Eventually, many hampering rules had to be repealed after competitors started to complain and lobby. Another feature of past success was the ability to respond to insider gossip in the oil industry since airlines burn hundreds of millions of gallons of gasoline. Much of the profitability of an airline depends on accurately predicting the direction of oil prices, and hedging against them. By confining himself to short trips, Kelleher could concentrate on flying only one model of airplane, thus reducing training and maintenance costs. There are advantages to being a Texas airline.

But there is a notorious boisterousness to it all. The employees are encouraged to behave like members of a college fraternity party, described as "dropping the mask and behaving naturally", although the parents of teenagers would have other descriptions. Employees are expected to have fun while they work. No frills, but lot's of fun, and cheap. Really cheap. Philadelphia is in for a big dose of success, and lots of fun flying everywhere they never flew before, welcoming the whole country to visit, and y' all come back, hear? The city is told to expect soon to be acting and talking like l'll Texas on Delaware. Maybe we must prepare for a rise in the incidence of lung cancer, too, if young people go too far in imitating his flouting of political correctness. At one point in this in-your-face talk, he came down into the audience and bummed a pack of cigarettes. Haw, haw, haw.

It's, therefore, some surprise to learn this man is a lawyer, honors graduate of New York University Law School. And even more of a surprise to learn he was brought up in Audubon, New Jersey, graduating in the class of 1949 from Haddon Heights High School. He must once have absorbed an inward dose of Philadelphia culture, and even a fair dose of New York City, but it didn't change the outward Texan a whit. What seem to be some dominant genes, conceived on Philadelphia's Spruce Street perhaps but nurtured on the hot prairies, are now coming back home. Uniquenesses in many generations of immigrants have been dissolved by Philadelphia's cultural waters, but this may be the first time we have contended with the earnest bravado of Texas. Come to think of it, maybe it's a wake-up call we need to hear. Corrupt and contented, pay to play, borrow to spend -- all of these jingles have perhaps been whistled a little too often around here.

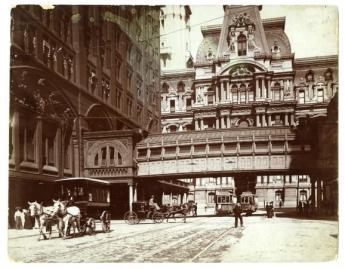

Convention Center

|

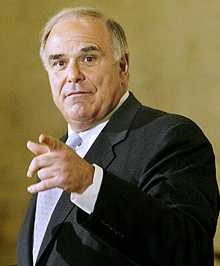

| Convention Center |

A substantial grant from the Pew Foundation initially funded The Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation but expected other more permanent funding sources to materialize by the end of three years. The funding source turned out to be a 1% tax on hotel rooms since hotels were rather easily convinced that an increase of tourism to Philadelphia would benefit them. There is every reason to think the whole idea was a good one, effectively implemented. However, it probably was not completely appreciated that this hotel tax would provide a measurement, a public thermometer, of the ebb and flow of tourists to the city. Thus, the devastating effect of labor troubles at the Convention Center upon the hospitality industry became quite undeniable, hence became potent political medicine in the municipal political campaigns. Tax revenues from this specified source were down, and the causes became hard to deny. Philadelphia has long been a strong union town, but it will be decades before the public forgets the behavior of the carpenter's union or the economic havoc it inflicted on the second largest industry in the region. Even the most committed liberal ideologue would have to admit that the members of the carpenters union would achieve greater personal income by moderating their wage demands and restraining their work rules, working more hours at somewhat lower hourly wages. The argument has long smoldered whether Philadelphia is the most American of American cities, or whether it is the most European of American cities. A case can be made, either way. This labor dispute may not settle the basic question, but it will certainly shift the city's image toward one direction or the other because this matter is not one of architecture, cuisine or speech patterns. It's a matter of the city's belief system.

The Birthplace of Radio

|

| WCOJ Radio |

We should all be grateful to Lloyd B. Roach, the President of WCOJ radio station inWest Chester PA, for researching and popularizing the history of American radio broadcasting. From him, we learn that public radio had its origin in Philadelphia, during the early 1920s. While it is true that KDKA in Pittsburgh can claim to be the oldest radio station around, there are those who say that radio as we now know it had its origins on the rooftops of four department stores clustered at Eighth and Market Streets, busily announcing what was on sale today, and helping draw teeming crowds to that center of dry goods merchandising that many of us are still alive to remember. Strawbridge and Clothier, Lits, and Gimbels were on three corners of the intersection, Snellenbergs was a block up Market, and John Wanamaker's big store was a couple of block still further West. In those early days, names like David Sarnoff and Arthur Atwater Kent were the equivalents of Bill Gates and Andy Grove today. Eighty years before the dot-com revolution, the public radio revolution made zillionaires of kids who had been working in cigar stores a year or two earlier, and not merely communication but world culture was forever changed. And in both cases, a sudden drop in the stock market wiped out a lot of them, although a few survived.

|

| Rush Limbaugh |

It seems you ought to know about "Absorption" which is some kind of electrical phenomenon whereby a lot of microwave and computer traffic wipes out the AM (as opposed to FM) signals in big cities. Because everyone knows that the political right wing likes the red expanses of the map, while the left or liberal way of thinking is concentrated in cities, hence blue parts of the map, the overall effect is that AM radio is more a phenomenon of the exurbs, rural districts, and highways. And a further consequence is that call-in radio is heavily right wing in its audience, hence programs, Rush Limbaugh and all that. Because of the innate remorselessness of paid political consultants, it doesn't take long for politicians to recognize that getting rid of absorption would make radio call-in shows more likely to reach urban liberals. We can't have that, or we must have that, depending on the bias of the observer, and hence a sort of radio signal called XM is something we predict will be made forbidden or made mandatory, because it makes urban liberal talk radio possible again. The beauty of this cutthroat battle is that it is so obscure that the public won't notice its significance until it happens, and when it does there will be few fingerprints on it. Commentators will rattle on about shifting tides of opinion when in fact some manipulation of the Federal Communications Act or the local broadcast licensing regulations by people who know very well what they are doing is what has gone on. Heh, heh.

To get back to Philadelphia, the dreary hulks which now stand where the department stores once stood are a reminder that shopping centers, or collections of strip malls, have killed the department store. Two phenomena are at work here. The brand name which gave credibility and comfort to the department stores' reputation is being replaced by national brand names with local franchises., and national advertising rather than regional. That might have been bearable if the department stores had not placed so much unwise reliance on the concept of the "full-service operation". If you try to sell everything in one-stop shopping, as for example selling pianos as well as perfume, some of the things you include are going to be losers. Consequently, the perfumes on which you made your profits will have to become more expensive to pay for the losses on pianos, and eventually, the perfume specialty stores will destroy your profit center, ruining the whole full-service business. This phenomenon, by the way, is beginning to eat away at the economics of hospitals as well.

Priceless Art as Mass Entertainment

The Philadelphia Museum of Art recently had a special exhibition of paintings by Edouard Manet, with a heavy dose of Claude Monet plus a few others. A moment's reflection demonstrates the enormous undertaking it must be to assemble a hundred valuable paintings from 60 different museums and owners, arrange for permissions, negotiate insurance and shipping costs, debate the best display, lighting and arrangement, instruct the guides, print the brochures, hype the announcement hype, and probably a thousand other details of making this all come out right. Although a lot cheaper to assemble this show and move it around to various cities, than it would be to have thousands of Americans travel to Europe to see the paintings there, nevertheless it looks expensive. Half a dozen major foundations donated money for this effort, and the ticket price is not insignificant. When you are all done, however, you have seen a display that no one could possibly see privately, all in one afternoon, with an elegant lunch on the premises in air-conditioned splendor, accompanied by a small orchestral group in the background. The show is resident for three months, less two weeks for setup and travel, so four cities can collaborate on four traveling exhibits each year. Somewhere, there must be a very large staff devoting full time to keeping these exhibits in constant movement; probably several cycles are going at once. This is big business, and filling that big museum every day for three months implies that many of the visitors are from outside Philadelphia. After you go, at least you can tell Manet from Monet, you've had a taste of the huge Museum that makes you want to come back some day, and you have seen Philadelphia's best view, right where Rocky ran up the steps.

Our guide was well trained and entertaining, and knew all about horizons, prompting some deep, deep thought about horizons. The Dutch school of painters usually put the horizon down near the bottom of the painting, showing off the billowing grey clouds so characteristic of the European coast near the North Sea. By contrast, the French impressionists went down to the sunny Mediterranean coast, where the bright sunlight forces you to look down at the ground. So the horizon of painting, the line where the sky meets the ground, is low in northern paintings, but high in scenes of the Riviera, representing in both cases the typical viewer?s image of the scene. No doubt, some painters deliberately reversed the normal location of the horizon, in order to create the unconscious effect on the viewer that something was somehow wrong.

This little lesson has practical utility for those of us who take amateur snapshots. The rule for photographers is to throw the horizon into either the top third or the bottom third of the viewfinder. Avoid putting the dumb horizon right in the center of the photo. Since most cameras nowadays have an automatic exposure meter, if you get it wrong the meter will concentrate on the sky, underexpose the subject below the sky, and give you a puzzling black silhouette instead of a picture of your girlfriend.

Returning to the reality of the Art Museum, it sits on top of a little mountain --Fairer Mount-- that William Penn once considered as a place to put his home. It was later the site of a reservoir, with the famous pumping station and water works down the hill on the edge of the Schuylkill. Now, this Parthenon is an easy place to reach and to park, while the world's art is placed before you. The Russian Tsar in his Hermitage, and the Archduke in his Viennese palace never had it as easy as this.

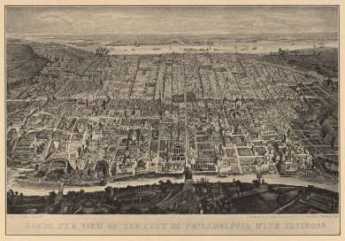

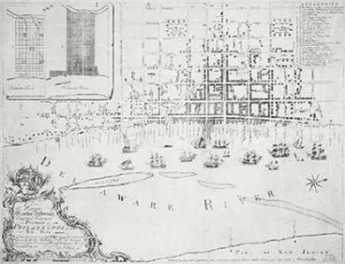

Whigs, Slaves, and Tariffs

At the time of the Revolution, Philadelphia had 25-30,000 residents. Although then it was the largest city in North America, today it would compare with a small suburb. By the time of the 1800 census, Philadelphia had 67,000 residents. The Capitol was moving to Washington; Philadelphia's fifteen minutes of fame were over. Still, the city had only achieved the size of what we would now call a one-industry town. The fifty state capitals today are about that size; look there if you want to observe the mentality and social structure of one-industry towns.

|

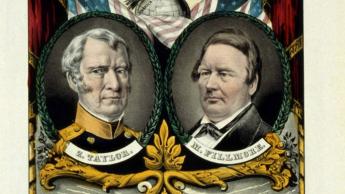

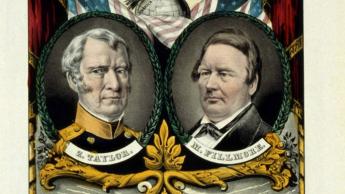

| Zachary Taylor, His vice president, Millard Fillmore |

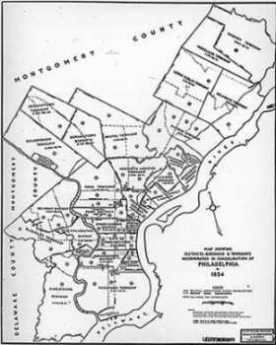

But by the 1850 census, Philadelphia's population was 408,000, 30% foreign-born. That's an entirely different environment. By the time of the Civil War, Philadelphia was a real city, with real growing pains. The rest of the country had similar problems, with different details. The voting franchise was extended beyond land-owning taxpayers in 1838, mostly affecting backwoodsmen who had immigrated a century earlier. In Philadelphia and other seaboard cities, however, the franchise was extended to factory workers from foreign cultures, and the result was natives. Street riots calmed down into politics but transformed into politics. "Know Nothings." a Nativity political party was named for its pledge to say "I know nothing" when the police arrived. (Philadelphia's 1854 city-county consolidation can be traced in part to a need to get local police forces to follow orders.) The extension of the franchise could be traced back to the 1828 election of Andrew Jackson, and it could be traced forward to the creation of modern political parties. The founding fathers supposed that leaders would be elected on the basis of deference, with a town like Philadelphia run by the Biddle's, Ingersoll's and Wharton's. And in fact, that was mostly how it was until 1828. After that, it was just a matter of time before the only thing that counted was the only thing that was being counted - votes. Since that time, business and social elites have from time to time rebelled with what they called "reform movements." But as Adlai Stevenson wryly remarked, it takes a majority to win. Election of elites is always and everywhere a rarity.

The critical moment for Philadelphia and the Republican Party came in a smoke-filled room in the 1850s when the anti-slavery movement was united with the Nativity Know-Nothing Party. Both of these parties held their national presidential convention in Philadelphia in 1856.In the background was dissolution of the Whig Party, and on the table was the protectionist tariff. The Whigs were an idealistic group, and Lincoln had been a fervent Whig. Their theme was building canals, roads, railroads and other features designed to promote prosperity by enhancing the economic infrastructure. The weakness of the Whigs lay in the way their approach usually raised taxes. The Know Nothings were far from idealistic; their weakness lay in the general fear they were promoting class warfare.

Someone proposed that the common ground between the two splinter parties lay in advocating the protective tariff. Of course, that's another bad idea, but as a vote-getter it was wonderful. It united the workers with the business owners, potentially enriching both of them. More importantly, it reassured the idealistic Whigs and abolitionists that class warfare could be avoided. Freeing the slaves, conversely, would appeal to businesses and workers who compete with slaves.

A hundred years earlier, Adam Smith had demonstrated that artificially raising prices impoverishes consumers, and the Wealth of Nations is thus always injured by tariffs. But anyway, on to the Wigwam, and on to Fort Sumpter.

Alexander Hamilton, Celebrity

He had the kind of taudry private life and flashy public behavior that Philadelphia will only tolerate in aristocrats, sometimes.

|

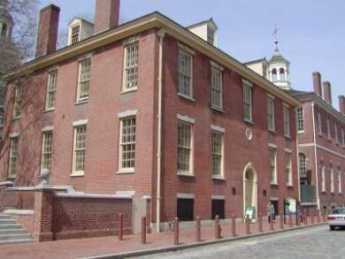

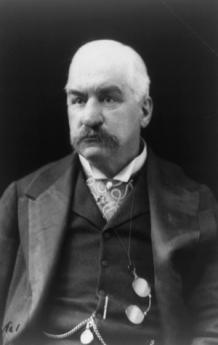

It comes as a surprise that most of the serious, important things Alexander Hamilton did for his country were done in Philadelphia, while he lived at 79 South 3rd Street. That surprises because much of his more colorful behavior took place elsewhere. He was born on a fly-speck Caribbean island, the "bastard brat of a Scots peddler" in John Adams' exaggerated view, was orphaned and had to support himself after age 13. The orphan then fought his way to Kings College (now Columbia University) in New York in spite of hoping to go to Princeton, and has been celebrated ever since by Columbia University as a son of New York. He did found the Bank of New York, and he did marry the daughter of a New York patroon, and he was the head of the New York political delegation. As you can see in the statuary collection at the Constitution Center, he was a funny-looking little elf with a long pointed nose, frequently calling attention to himself with hyperkinetic behavior. Even as the legitimate father of eight children, Hamilton had some overly close associations with other men's wives, probably including his wife's sister. Nevertheless, he earned the affection of the stiff and solemn General Washington, probably through a gift of gab and skill getting things done, while outwardly acting as court jester in a difficult and dangerous guerilla war. There is a famous story of his shaking loose from the headquarters staff and fighting in the line at Yorktown, where he insolently stood on the parapet before the British enemy troops, performing the manual of arms. Instead of using him for target practice, the British troops applauded his audacity. Harboring no such illusions, Aaron Burr later killed him in a duel as everyone knows; it was not his first such challenge.

|

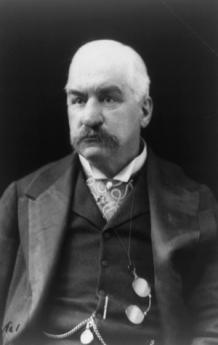

| Alexander Hamilton |

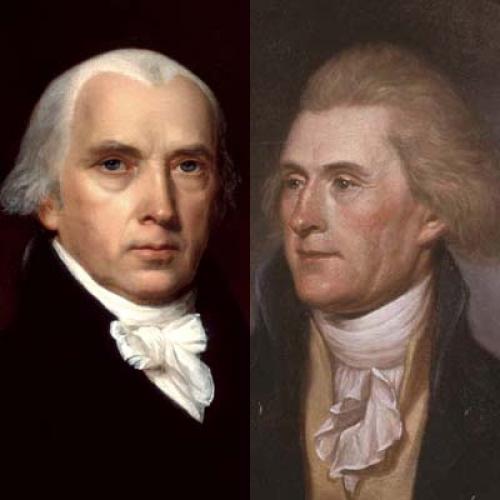

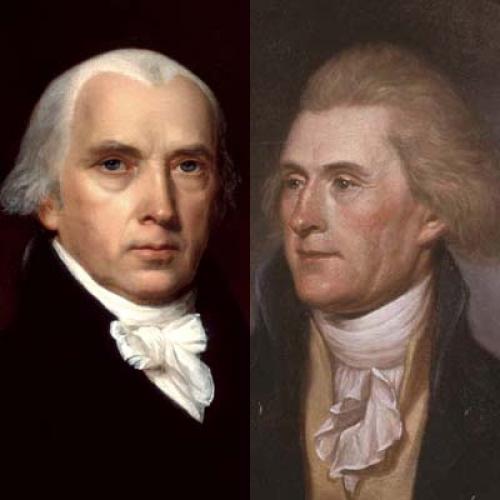

Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler told other stories of celeb behavior to reinforce Hamilton's New York flavor. But in the clutch, General Washington learned he could always trust Hamilton, who wrote many of his letters for him and acted as his reliable spymaster. When the first President faced signing or not signing the fateful bill to create the National Bank, a perplexed Washington had to choose between: the violent opposition of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, or the bewildering complexity of Alexander Hamilton's reasoning in arcane economics. On the one hand, there was the simple principle that owing money was seemingly always evil; on the other was the undeniable truth that for every debit created, you create a balancing credit somewhere. Washington ultimately chose to go with Hamilton, whose reasonings he likely didn't understand very well. If you doubt the difficulty, try reading Hamilton's Report on the Bank, written to persuade the nation and its first President of the soundness of his ideas. And then consider the violence of even present-day arguments about such "supply side" economics.

|

| Nicholas Murray Butler |

All of these momentous events happened in Philadelphia at places now easily visited in a morning's stroll. But Hamilton's image as a Philadelphian, doing great things in and for Philadelphia, was forever tarnished at one single dinner he hosted. Jefferson and Madison, his political opponents but his guests, were persuaded to provide Virginia's votes for the federal takeover of state Revolutionary War debts, in return for offering New York's votes for moving the nation's capital to the banks of the Potomac. True, Pennsylvania allowed itself to be pacified with having the capital remain here for ten years while the southern swamps were being drained. But it was Hamilton who cooked up this deal and sold it to the other vote swappers. Philadelphia felt it was entitled to the capital without needing to ask, felt that Hamilton was deliberately under-counting Pennsylvania's war debts, and this city has never appreciated the insolent idea that its entitlements were forever in the hands of wine-swilling hustlers. As the economic consequences of this backroom deal became evident during the 19th Century, it was increasingly unlikely that Philadelphia would lionize the memory of the man responsible for it. Let New York claim him, if it likes that sort of thing. When Albert Gallatin, who was more or less a Pennsylvania home town boy, attacked Hamilton as a person, as a banker, and as a Federalist -- he had a fairly easy time persuading Philadelphians that this needle-nosed philanderer was an embarrassment best forgotten.

REFERENCES

| Alexander Hamilton Ron Chernow ISBN:978-0-14-303475-9 | Amazon |

After the Convention:Hamilton and Madison

|

| Signers |

The Federalist Papers were written by three founding fathers after the Constitution had been completed and adopted by the Convention. Detecting hesitation in New York, the aim was for publication in New York newspapers to persuade that wavering State to ratify the proposal. It is natural that The Federalist was composed of arguments most persuasive to New York, putting less stress on matters of concern to other national regions. This narrow focus may explain the close cooperation of Hamilton and Madison, who must surely have suppressed some latent concerns in order to present a unified position. In view of how much emphasis the courts have placed on the original intent of almost every word in the Constitution, it seems a pity that no one has attempted to reconcile the words of the principal explanatory documents with the hostile disagreements of their two main authors, almost as soon as the Constitution came into action. Perhaps the psychological hangups would be more convincingly dissected by playwrights and poets, than historians.

John Jay wrote five of the essays, mostly concerned with foreign relations; his presence here highlights the historical likelihood that Jay might have been the one who first voiced the idea of replacing the Articles of Confederation. At least, he seems to have been first to carry the idea of a general convention for that purpose to George Washington (in a March 1786 letter). The remaining essays of The Federalist were written under the pen name of Publius by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, both of whom had a strong enough hand in crafting the Constitution, but who quickly became absolutely dominant figures in the two central political factions after the Constitution was actually in operation. And their eagerness to be central is itself telling. They were passing from a stage of pleasing George Washington with his favorite project, into furthering a platform for launching their own emerging agendas. It is true that Madison's Federalist essays were mainly concerned with relations between the several states, while Hamilton concentrated on the powers of the various branches of government. As matters evolved, Hamilton soon displayed a sharper focus on building a powerful nation; Madison scarcely looked beyond the strategies of internal political power except to see clearly that Hamilton was going to get in the way. These two areas are not necessarily incompatible. But it is nevertheless striking that two such relentlessly driven men could work together to achieve the same set of rules for the game they were about to play so unflinchingly. Thomas Jefferson had been in France during the Constitutional Convention. It was he who was most dissatisfied with the resulting concentration of power in the Executive Branch, but Madison eagerly became the most active agent for forming the anti-Federalist party, with all its hints that Washington was too senile to know the difference between a President and a King. Washington abruptly cut him off and never spoke to Madison after the drift of his opinions became undeniable. Today, it is common to slur politicians for pandering to lobbyists and special interests, but that presents only weak competition with the personal forces shaping leadership opinion, chief among them being loyalty to, and perceived disloyalty from, close political associates.

As a curious thing, both Hamilton and Madison were short and elfin, and both relied for influence heavily on their ability to influence the mind of

|

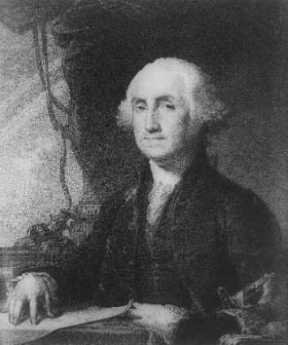

| George Washington |

George Washington, who projected the power and manner of a large formidable athlete. Washington had no strong inclination to run things and, once elected, no particular agenda except to preside in a way that would meet general approval. He had mainly wanted a new form of government so the country could defend itself, and pay its soldiers. Madison was a scholar of political history and a master manipulator of legislative bodies, while Hamilton's role was to supply practically unlimited administrative energy. Washington was good at positioning himself as the decider of everything important; somehow, everybody needed his approval. On the other hand, both Madison and Hamilton were immensely ambitious and needed Washington's approval. This system of puppy dogs bringing the Master a bone worked for a long while, and then it stopped working. Washington was very displeased.

The difference between these two short men immediately appeared in the way they chose a role to play. Madison the Virginian chose to dominate the legislative process as the leader of the largest state delegation within the

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

House of Representatives, in those days the dominant legislative chamber. Hamilton sought to be Secretary of the Treasury, in those days the largest and most powerful department of the executive branch. It's now a familiar pattern: one wanted to form policy through dominating the board of directors, while the manager wanted to run things his way, even if that led in a different direction. Both of them knew they were setting the pattern for the future, and each of them pushed his ideas as far as they would go. Essentially, this could go on until Washington roused himself.

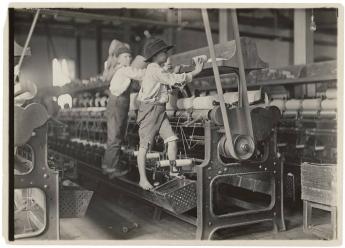

After a short time in office, Hamilton wrote four historic papers about two general goals: a modern financial system, and a modern economy. For the first goal, he wanted a dominant national currency with mint to produce it and a bank to control it. Second, he also wanted the country to switch from an agricultural base to a manufacturing one. You could even say he really wanted only one thing, a national switch to manufacturing, with the necessary financial apparatus to support it. Essentially, Hamilton was the first influential American to recognize the power of the Industrial Revolution which began in England at much the same time as the American Revolution. Hamilton was swept up in dreams of its potential for America, and while puzzled -- as we continue to be today -- about some of its sources, became convinced that the secrets lay in the economic theories of

|

| David Hume |

David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, and of Necker in France. Impetuous Hamilton saw that Time was the essence of opportunity; we quickly needed to gather the war debts of the various states into the national treasury, we quickly needed a bank to hold them, and a mint to make more money quickly as liquidity was needed. It seemed childishly obvious to an impatient Hamilton that manufacturing had a larger profit margin than agricultural products did; it was obvious, absolutely obvious, that this approach would inspire huge wealth for the new nation.

|

| Industrial Revolution |

Well, to someone like Madison who was incredulous that any gentleman would think manufacturing was a respectable way of life, what was truly obvious was that Hamilton must be grabbing control of the nation's money to put it all under his own control. He must want to be king; we had just got rid of kings. Furthermore, Hamilton was all over the place with schemes and deals; you can't trust such a person. In fact, it takes a schemer to know another schemer at sight, even when the nature of the scheme was unclear. Madison and Jefferson couldn't understand how anyone could look at the vast expanses of the open continent stretching to the Pacific without recognizing in this must lie the nation's true destiny. Why would you fiddle with pots and pans when with the same effort and daring you could rule a plantation and watch it bloom? If anyone had used modern business jargon like "Win, win strategy", the Virginian might well have snorted back, "When you say that to me, friend, smile."

Parliament Provokes a Revolution

In some medical circles, it is postulated that George III was psychotic, possibly suffering from an inherited rare condition called porphyria.

|

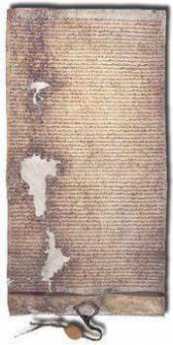

| Magna Carta |

That's pretty conjectural, but it is certainly true that his mother egged him on to be a real king, a real force reversing that steady decline in the Monarchy's personal power which began with the Magna Carta. By the time in question, however, so much power had already gravitated into the hands of Parliament that the King could not act in any major way without their consent. Even today, Cabinet Ministers are spoken of as King's ministers but are in fact appointed by leaders of the majority party in Parliament. Some in Parliament, like Edmund Burke, were almost persuasive in resisting the Ministry, urging colleagues to seek reconciliation with the colonies. George III did still retain the power to appoint his favorites to important positions and used this patronage extensively to control the country. Political party chieftains, on the other hand, retained and retain today the power to nominate the party candidate for Parliament in any particular district. The leadership thus selects the members of Parliament, who can, in turn, overturn the leadership only if they dare. Real decisions were largely in the hands of party chieftains, but perhaps to some extent, the Crown, depending on the Monarch's shrewdness in distributing patronage among the party chieftains.

Across thousands of miles of dangerous ocean, the English colonies had changed from the weedy wilderness in the Sixteenth century, into thriving and prosperous small civilizations in the early Eighteenth. Transatlantic communication did not substantially improve in that interval, but colonial population grew to over a million, many of them native-born in the colonies, with increasingly large numbers of immigrants from other nations. Loyalty to the Monarch inevitably declined. True, they spoke English, revered England, but many urgent local issues were difficult to administer at such a distance, encouraging a mentality of self-governance. France, by now at war with England on the Continent, operated on a grand plan of interior encirclement, from Quebec and and Great Lakes, down the Mississippi to New Orleans. The English coastal settlers needed peace with the Indians of the interior;

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

the French did not scruple to stir up massacres and Indian warfare. All wars are expensive, the French and Indian war particularly so. After defeating the French, the British were put to the protracted expense of building frontier defenses. Although the British were anxious to attract English-speaking colonists who would defend America for England, it was obvious some of the settlers were becoming very rich. Surely these people could not object to paying taxes for their own defense. In retrospect, it seems remarkably naive of the British to think it was that easy. Americans did not want to pay taxes because they did not want to pay taxes. They settled on the stance of "No taxation without representation" and like Franklin and the Penn family, many really believed in it. That slogan was particularly effective after it became apparent that Parliament wasn't about to give remote colonists reciprocal power in Parliament to interfere with affairs in the British Isles. With Parliament adamantly refusing to dilute its own power, "No taxation without representation" was a neat rhetorical box which meant, "No taxation." Contemporary English historians now throw up their hands in despair that so few members of George III's government had Burke's vision or even the normal wiles of diplomacy. But that understates the hidden political agenda. Parliament just pushed ahead with fairly nominal taxes, but they did so to curtail the independence of colonial legislatures.

The Stamp Act of 1764. It could be argued that Navigation Acts nothing new; earlier versions were first passed in 1651, intended to thwart Dutch trading. They prohibited foreign trade with the British home islands. After fifty years in 1703 similar restraints were extended to trade with the colonies, particularly molasses in the Caribbean area. No outcry was made as these restraints, aimed at retaining the Britishness of British colonies, were occasionally modified and extended over the next sixty years.

|

| Thomas Penn |

After a century in 1764, however, the Stamp Act was passed, producing modest revenue but imposing a crippling set of headaches by requiring special papers to transact private business. The uproar was enormous and legitimate, focused mostly on the tangle of red tape needlessly imposed. By shifting taxation from trade to paperwork transactions, suspicions were plausible that the Ministry was scheming something obscure. The Stamp Act was hastily repealed, even before Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Penn recognized its unpopularity and were still to some extent defending it in 1766. Franklin apparently saw the Stamp Act as an opportunity to appoint his friends as stamp agents. Local uproar in Pennsylvania was apparently orchestrated by William Bradford, who in addition to having been Franklin's former competitor in the printing business, was the owner of the London Coffee House at Front and Market. No other prominent colonial leader seems to have been involved in the agitation, and it is remotely conceivable that uproar originated with Bradford alone. More likely, Bradford was merely an opportunist in a genuinely popular uprising. With the familiar maneuvering characteristic of politicians, Franklin took popular credit for defeating the Stamp Act with some skillful criticism of it, while John Penn gained credit with the King for representing Pennsylvania's relative calm about it, compared with other colonies. In Pennsylvania at least, the uproar quickly subsided after the repeal of the Act.

The Townshend Navigation Acts of 1768.In 1766 the Grenville Ministry was replaced by that of Rockingham, then soon by Pitt, who were anxious to disavow the unpopular Stamp Act, but nevertheless needed colonial revenue, and needed a few unpleasant laws to prove that Parliament could not be intimidated by colonial squawking.

|

| Charles Townshend |

Charles Townshend, the brilliant, vindictive, Chancellor of the Exchequer then proposed taxes on glass, painter's lead, paper, painter's colors, and tea. The underlying political purpose of these taxes was to provide revenue for paying British colonial administrators directly, rather than depend on the Colonial legislatures to pay them. The Legislatures had long played a game of withholding payments, sometimes even the salaries of Judges and Royal Governors, when they disapproved of projects devised in London. The very predictable uproar provoked by the Townshend Acts propelled John Dickinson into prominence with a pamphlet called Letters From a Pennsylvania Farmer, which popularized the idea of "nonimportation", essentially a boycott of British products. Unintentional nonimportation was in fact the effect of the laws, clogging the ports with paralyzed trade goods. Rather than Dickinson's lofty principles, a little-noticed act of 1764, prohibiting the printing of paper money, paralyzed trade. There simply was not enough available coinage to pay these taxes, which finally pushed the primitive transaction system beyond its capabilities. From the viewpoint of modern economics, a heavy unbalance between imports and exports could not be rebalanced by flows of capital. The disastrous Townshend Acts were mostly repealed in 1770, but the British government was getting in deeper and deeper, discrediting itself at every turn. To retreat but still save face, they repealed all the taxes except the one on tea.

The Tea Act of 1772. To a certain degree, the uproar over the face-saving tax modifications on tea was a pretext for confused but radical colonists who were spoiling for a fight about difficulties they tended to personalize. The act actually lowered the effective taxes on tea, and at first Whig radicals were hard put to find a reason for outrage about lowering the price of tea. However, Bradford and his London Coffee House cronies (Mifflin, Thomson) were imaginative, and soon stampeded a mob scene in Philadelphia, where for a time the populace had seen nothing to get worked up over. Rush and Dickinson joined the chorus; the public feeling was stirred to a frenzy not easily reversed.

The really substantive issues involved were created by several years of Townshend Duties and other forms of import restriction. Laws to ensure the Britishness of British colonies created pleasant opportunities for colonial artisans and craftsmen, difficult hardships for importers. But these dislocations, whether welcome or unwelcome, firmly exposed the underlying truth that they caused all colonists to pay higher prices for goods. Adam Smith was not to publish his Wealth of Nations until 1776, so in this case the proof preceded the theory. The colonists were effectively asked to pay higher prices for everything, in order to increase Britishness and to billet soldiers they could not command. Once that cat was out of the bag, attitudes could never be the same. On the English side of the ocean, the question was framed as colonist unwillingness to contribute to the cost of their own defenses. The two slanted perceptions hardened to the point where arrogance confronted defiance, suggesting combat to both of them.

In the case of tea, taxes and import restrictions were intended to promote English tea over Dutch tea; in fact, they stimulated smuggling. Smuggling grew to a point that vast quantities of tea were stranded in the warehouses of the British East India Company, and trade balances of the British Empire were undermined. By reducing taxes, Parliament made East India tea cheaper than smuggled tea. Going perhaps one step too far, middle-men in the tea import business were cut out of the loop by appointing favored direct agents. In Philadelphia, those were Henry Drinker and Thomas Wharton. Bradford and his group immediately set about intimidating these merchants with threats to burn them out, and the sea captains who worked for them, with threats of tar and feathers. The age of Reason was leaving Reason behind.

Reflections on Swensen

A. Techniques of rebalancing. Three directions to take this, occur to me.

1. Purchase 60/40 mutual funds and let them do the rebalancing. This would offhand seem the easiest way to do it, but what are the results? Do you think it would be practical to construct a 60/40 mutual fund by combining and rebalancing a world-wide index fund with a bond fund? Since bond funds are dubious, how about a mutual fund that contained the equity index fund and did its own bond juggling? How about a family of funds, mixing 50/50, 55/45, 60/40, 65/35, 70/30, 75/25. 80/20, as the investor chooses? Since this would probably amount to a pool that sold virtual shares, almost any combination seems feasible. But is it legal? At one time the fund of funds was illegal for whatever reason; possibly Vanguard has a right to object to such secondary use of its funds. By getting a fund together, there should be enough volume to consider real-time rebalancing. When you consider doing it for yourself, the fund approach seems increasingly attractive.

2. Establish two brokerage accounts at Vanguard, one for equities and one for bonds, each of which is linked to its own separate money market sweep fund. Monthly rebalancing should be possible from the monthly statement, with the money market of one account purchasing shares of the other asset class as needed for rebalancing. A refinement of this might be to purchase shares of the "wrong" account and hold them until the capital-gains period has expired, then transfer to the "correct" account. I presume that transfers between two money-market accounts would be fairly simple, avoiding the perplexities of buying shares with one account but depositing them in another. Adjusting the order to reinvest dividends or not reinvest seems like a nice refinement, lessening the need to sell things.

3. Doing the whole business in Quicken. If you are thinking of doing this for clients, you might want to avoid the hazards of actually doing the transactions, simply sending the client a set of suggested monthly instructions to give to his broker or transact electronically. This might seem attractive to people running trust funds, who already carry the fiduciary hazard.

B. Selecting or deselecting, those companies who regularly rebalance their own debt/equity ratios. One of the important insights I get from Swensen is that company treasurers are often rebalancing in the opposite direction from the investors. That is, issuing more stock as their price/earnings ratio gets ridiculously high, buying back their stock when the price gets cheap. Not all companies do this, and those who do probably reduce their volatility considerably. If this is a really major reason for investors to rebalance in the other direction, then there may be a considerably reduced value in rebalancing companies that are doing it for you, and enhanced value in rebalancing the rest.

1. Since you don't know the intentions of a company, and anyway they may change treasurers without your knowledge, there is a need to find some surrogate for this activity. That's particularly true of companies that may only do it in one direction, and thereby alter the balance between raising equity capital and borrowing. Does the p/e ratio seem adequate to you as a surrogate? If not, is there a practical alternative?

2. I've been told that small companies borrow from banks, large companies issue bonds. Is this of any practical value to an investor? Are they a distinct asset class? After all, you can change your debt/equity ratio by adjusting either component, or you can reduce your total external capital requirement by using internally generated funds. Does this issue get you anywhere in selecting asset classes?

3. Companies or asset classes with a lot of volatility apparently give Swensen an opportunity to rebalance profitably. Aside from that, it is better for a company to have low volatility or high? If all companies got religion and did their own rebalancing, would there be any value in investors continuing to do it? To put it another way, just where is the value added by rebalancing? What signs would you look for, to decide that rebalancing is no longer cost effective?

C. Life insurance to reduce taxation. The October 18, 2006, Wall Street Journal observes that the IRS has issued clarifying instructions about using life insurance to reduce taxation; it also goes on to say that lawyers will charge you $10-20,000 to read them to you. But, apparently, it's ok to do this if you follow the rules. Essentially, life insurance investments compound internally without taxation and also escape estate taxes if you donate ownership of the policy to your heirs.

1. In the case of a spousal trust, the estate taxes are already waived, so one complexity is reduced or eliminated. There is no need to transfer ownership of the policy.

2. So the issue reduces itself to avoiding dividend and capital gains taxation, short and long. I gather they have not thought of the requirement to distribute all income from a spousal trust, so there is a chance some agent would balk at the technicality.

3. So, except for this risk, it's a simple trade-off between the fees for insurance versus the taxes saved, and I strongly suspect the fees are worse, so the issue isn't worth considering at all. But of course I don't know what the fees are, so I don't know the threshold level where tax avoidance becomes an important asset. Even the health issue is semi-answered since you could escape a physical exam by selecting an annuity life insurance; more fees to overcome, of course.

D The same Wall Street Journal includes a quotation from unknown research that calculating the dollar value weighting of mutual funds versus fund results demonstrates that all reasons for not buying-and-holding combined show a 1.5% penalty for all strategies other than buy/hold.

1. Therefore, the 0.5% advantage of rebalancing over buy/hold is actually a 2.0% advantage over the penalty for deviating. That's a more substantial argument that has so far been made for rebalancing, but needs to be re-examined to be sure the penalty is not actually hidden in the 0.5% claim, since if so that would convert it into a 1% loser strategy.

2. For no visible reason, broker-handled funds average 0.5% lower return than direct-buy funds. May I suggest some hidden kick-back has surfaced?

3. Low-volatility stocks seem to produce an 0.8% advantage over high-volatility stocks and a shocking 2.8% difference on a dollar-weighted basis, suggesting volatility makes investors lose their nerve in addition to the innately inferior performance. Is it reasonable to give them a neutral weighting in a portfolio?

The Jews in Colonial Philadelphia

|

| Haym Salomon |

The word Sephardi is derived from the Hebrew word for Spain, where Jews were a prominent part of the Arab community for several hundred years. The Christian monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, regarding the Sephardim as pro-Arab, drove them out of Spain and Portugal in 1492. They scattered widely, and only a small portion eventually got to the Western hemisphere. It is also helpful to know that Askenazic is the Hebrew word for German since this other main branch of the religion did not emigrate to America until later in the Nineteenth century in response to the suppression following the 1848 Revolutions. There are some important differences in liturgy, and occasional episodes of bad feeling between the two Jewish groups, some of it kept alive by issues arising in Israel. Historically, the Sephardim have had a greater tendency to assimilate in local cultures, both generally and particularly in Philadelphia. However, the most prominent Jew in the American Revolutionary War was Haym Salomon, who was born in Poland.

On leaving Spain, many Sephardim had gone to Amsterdam, and from there to the Dutch colonies hat accounts for their presence in the Delaware Bay as part of the Dutch settlements which preceded William Penn's arrival. The British conquest of the Dutch accounts for their subsequent local disappearance. However, it paradoxically also accounts for an influx from Curacao and other Caribbean Dutch colonies conquered by the British, usually favoring New York as a place to settle. Presumably, Sephardic feelings about the English were cautious at best. When the British occupied New York in the early days of the American Revolution, many Sephardim fled to Philadelphia, but largely returned to New York after the end of the Revolution. There was thus a double process of filtering out those who were unsympathetic with the British, and those who were attracted by seeing what Philadelphia represented.

Records were poorly kept in those days, and in civil wars, there are often reasons to be vague about your sympathies and activities. We know that Haym Salomon came to Philadelphia in 1774, grew very rich in association with Robert Morris, but died in poverty after a few years, now lying in an unmarked grave. It is a little unclear how he became rich, although all merchants involved in shipping did a little privateering, often described as piracy by the victims. It is also unclear how he became suddenly poor, although speculators in currency and land often make serious misjudgments. Robert Morris is himself a prime example.

The matter becomes of greater interest when Haym Salomon is sometimes referred to as one of the main financiers of the Revolution. Partly because of the ease of counterfeiting with the primitive printing technology of the time, the British had forbidden the use of paper money in the colonies as part of the Townshend Acts. While understandable, it caused great pain to unbalanced trade partners, and metal coins quickly migrated back to England, almost paralyzing colonial economies for lack of cash to transact local business. It probably caused a different sort of a pain to Benjamin Franklin, who derived much of his income from printing the currency of New Jersey. In particular, it kept cargoes trapped in port for lack of payment, which the annoyed British merchants mistook as an implementation of John Dickinson's proposal for deliberate "non-importation". In any event, Jewish merchants and bankers were well situated to find ways around currency blockages, sometimes using precious gems as substitutes for specie, and utilizing informal family networks scattered around the world. In civil wars, guns have to be bought and paid for, legalities get swept aside. There is said to be evidence that our ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, utilized Salomon to translate the French loans he had negotiated into the munitions which colonials needed. There is incidentally reason to believe that the Rothschild family established its great wealth by similar commodity dealings at the time of the Battle of Waterloo.

Just what it was that went so drastically wrong for Haym Salomon at the conclusion of our war for independence has not yet been made clear, perhaps never will be. He may have been caught in the uproar over the worthless Continental currency, his ships may have been captured, or he may have been trapped by the land speculation which ruined Robert Morris. But those were rough, tough times. We have the word of those who should know, that Salomon's service was essential to our achievement of Independence.

BEA Monitors the Economy

|

| Global Interdependence Center |

The Global Interdependence Center meets at the Philadelphia Federal Reserve, organizing frequent seminars of outstanding quality about finance. This week, the speaker was Andrew Hodge, head of Profits Research, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Someone there once had the brilliant idea that aggregate national income was almost identical to Gross Domestic Product, so national income could be easily derived from tax information at the I.R.S. Originally probably seen as a way of verifying GDP statistics derived in other ways, aggregated income and profits look in some ways to be superior to the data coming from Wall Street earnings reports. As a leading indicator, it appears to be outstandingly effective in predicting an impending upswing in the business cycle, just about at the time everyone is getting discouraged about downswings. It's not so good at predicting market peaks.

Seems to be superior to Wall Street earnings reports in four ways. 1) Wall Street is not particularly useful in distinguishing domestic from foreign activity within multinational firms. 2) Wall Street reports generally attempt to avoid seasonality noise by comparing this month with this-month-last- year. If the market direction has changed during the past year, downswings may cancel upswings and such comparisons can be misleading. 3) at market inflection points, volatility gets exaggerated by firms going out of business at the bottom or businesses formed or expanded at the top. 4) Wall Street is only 40% of the economy. The other 60% has private ownership, particularly in S-corporations.

Out of studying the differences between the two types of statistics about the economy, it emerges that the tax-derived BEA statistics are quite good leading indicators, particularly when the economy is in a trough. They are sort of leading indicators of coming market peaks as well, but they lead by longer intervals. A lead of as long as a year isn't very useful as an indicator.

As the jargon goes, that's the take-home message. BEA data is pretty good at predicting market bottoms. But some interesting sidelights appear, as well.

Our economy is becoming less volatile, with milder cycles and less frequent ones. But national income is just as volatile as ever, particularly in stock prices. This would appear to be due to the steadily increasing proportion which is in the financial sector (or decreasing proportion in the manufacturing sector). The financial sector is characterized, worldwide and for a long time in the past, as having "sticky" wages and costs. With the cost side comparatively inert, profits become much more volatile. In the final analysis, the stock market becomes more volatile than the underlying economy.

A final conclusion is my own. If the best personal investment vehicle is a broad index fund representing the whole economy, then you had better be watching national statistics like the BEA, rather than sector statistics. At the moment, the problem is deciphering what's available on BEA.gov in tabular rather than graphics format.

Corrupt and Contented

In 1904, first in McClure's Magazine and then in the book Shame of the Cities, Lincoln Steffens described the root cause of Philadelphia's bad local politics as failure of the people to turn out to vote.

The Philadelphia machine isn't the best. It isn't sound, and I doubt if it would stand in New York or Chicago. The enduring strength of the typical American political machines is that it is a natural growth -- a sucker, but deep-rooted in the people. The New Yorkers vote for Tammany Hall. The Philadelphians do not vote; they are disfranchised, and their disfranchisement is one anchor of the foundation of the Philadelphia organization."

Just exactly a century later, a Republican member of the Legislature coined a phrase:

"You show me a hundred thousand dollars, and I'll show you a Pennsylvania judge."

Asked to comment, two Democratic politicians on the inside (although one is dead and the other is in Federal prison for embezzlement) replied:

"That isn't precisely so. The precise way of stating it is that, to be elected a judge has two basic requirements. The first is the approval of a local ward leader. The second is the expenditure of between seventy and hundred-thirty-thousand dollars. With these two requirements fulfilled, just about anyone can be elected judge, regardless of legal qualification."

Is it a mystery why we have a malpractice crisis? Other explanations are offered, but this one, the system of "elected" judges, should be examined first. It's a slightly worse system than appointing them. Someday, someone will discover why state courts are much more corrupt than federal ones. Is the court system getting worse from the bottom up? Or getting better from the top down?

Economics of La Cosa Nostra

|

| Angelo Bruno |

During all of the reign of Angelo Bruno, it was a common street opinion that The Organization tried to stay away from drugs, prostitution and shooting anybody except other mobsters. Some of that attitude is found in the scene of the movie The Godfather where a neophyte going to his first killing is instructed to "Watch out for those goddam innocent bystanders". It was okay to bribe the police, not okay to annoy them. Counterfeiting and kidnapping were big no-no's, even though counterfeiting was a core activity for the ancestral Mafia in Western Sicily during the Nineteenth century.

|

| Al Capone |

According to Robert Simone's book, the Philadelphia mob was mainly enriched by loan sharking. There are a lot of people who suddenly need cash desperately and can't get it quickly from banks. Simone himself was a compulsive gambler and frequently was in urgent need of money, either to throw it away or pay it back. Other people get caught in some illegal activity and suddenly need bail money to stay out of prison or up-front money for a lawyer. Or whatever. The Philadelphia mob had a reputation for being able to loan amounts of fifty or a hundred thousand dollars in response to a phone call, with home delivery of the money in fifteen minutes. For this, they would charge interest in the range of three percent a week, well above the usury limit, but probably not greatly out of proportion to the risk of loss. The police have little interest in transactions between willing parties, at least until the borrower fails to pay it back. Even at that point, it becomes a question of whether kneecaps will actually get broken, or baseball bats actually come in contact with skulls. Probably not very often, because the threat seems a credible one.

To run such a business requires large amounts of cash, hidden in safes or bricked up in walls. From this comes theft or attempted theft, with violent defense measures that often don't concern the police, much, unless those aforementioned bystanders get injured. Sometimes couriers get tempted to make unscheduled detours, but the police are fairly tolerant of informal restitution efforts. All in all, it's a nice clean illegal business.

An interesting sidelight is income tax evasion. It's entirely possible that The Organization would be willing to pay taxes if it could be done without filling out all those forms. Restaurants, bars, and market stalls can be run as a way to launder money and yet pay tax on it. But boys will be boys, and no doubt the IRS has, or had, some legitimate concerns. For years I felt the government was over-reaching when it jailed Al Capone for income tax evasion, after being unable, however, convinced it may have been, to convict him of overtly illegal activities. That's one side of it. But if you envision these organizations with millions of dollars in cash hidden away, it's easy to imagine them extending invisible credit to their associates for services rendered but not yet paid out and, of course, untaxed. Calling for such money on demand is not much different from having it in a bank. If appreciable amounts of that circumvention go on, the Internal Revenue Service really might have a grievance. Its image would be improved by demonstrating it is pursuing a named crime rather than a pretext to jail someone it doesn't like. Legislation could surely be devised which more carefully specified such illegalities. It might then be possible to bring an end to the appearance of putting people in jail for merely enjoying an ornate lifestyle. People who, almost by definition, cannot be proven to have committed a crime.

Insuring the Uninsured is Not Entirely a Health Issue

|

| James Madison |

shrewdly observed that people could and would restrain state taxation by moving to a neighboring state. The founding fathers never contemplated health insurance or Medicaid, of course, but the same principle applies there in reverse. If one state gets too generous with health and welfare benefits, people in neighboring states will nowadays hear of it and get on a bus to relocate advantageously. A flood of new low-income citizens may or may not be what a particular state wants, depending on local economic conditions.

For example during the great depression of the 1930s,

|

| The Great Depression |

Unemployment was so widespread that no state dared attract still more of it with generous welfare benefits. On the other hand, during the recovery period that followed World War II, the industrial northern states definitely did attract cheap labor from the southern states, using better health care, freely available, along with better unemployment benefits. In each case, employers alternate between wanting cheap labor or low taxes, while labor representatives relax or toughen their resistance to the cheap competition. Politicians are always looking for the argument that carries the most votes. If you want to understand the persistence of employer-based health insurance alongside unobtainable health insurance for others, look into this trio of motivations.

While it's true state legislatures must tend to the infrastructure, crime conditions and education, they can in the main be regarded as debating societies between employers and labor. There is some, but not much, the difference between Republicans and Democrats on the Medicaid issue. A Democratic Governor will welcome an influx of low-income voters who will normally vote for his party, but labor unions will soon remind him that enough is enough. A Republican Governor will gladly supply cheap labor for the state's employers until rising taxes bring an end to his support. Since the financial stability of the local hospital can be badly jarred by the instability of Medicaid payments, doctors soon get annoyed with the misalignment between state motives and the welfare of their patients. It is not much of an exaggeration, that state coffers might be overflowing with the surplus, but the budget of Medicaid will not rise a penny if it would attract poverty migrants from neighboring states during a period of high unemployment.

The obvious solution is a federal one, imposing uniform standards. But think that over a little before you jump at it. If the federal government pays all of Medicaid costs, it is going to want to administer the program. All states resist that idea, more so if local and federal political domination is in conflict. Small states will universally be fearful of being overwhelmed by large neighbors, particularly when they have achieved advantageous niches. The disastrous condition of the auto industry might persuade Michigan to agree, but Tennessee and other states with Japanese car plants might disagree. As you get close to the border of large states, hospitals near the border can often attract many patients from the other state; strange political bedfellows can link arms in Congress when you might not expect it.

None of this, absolutely none of it, has to do directly with medical care. But the quality of health care is strongly affected, and doctors are sick of hearing about poor sick folks when the real issue is labor availability. The voice is Jacob's voice, but the hand -- is the hand of Esau.

Friends of Boyd

|

| Boyd Theatre |

Howard B. Haas a lawyer, and Shawn Evans an architect, are captains of a team trying to "save" the old Boyd Theatre at 1908 Chestnut Street. Since Clear Channel, the present owner has invested $13million in the property, and the preservationists agree that renovation of the movie palace to all its former glory would cost between $20million and $30million more, it's easy to understand why every other movie palace in central Philadelphia has been demolished. Furthermore, that area of town is having a resurgence of high-rise construction, so one use of the property must be balanced against others.

|

| Sam Eric |

The Boyd was built in 1928, just before the stock market crash, and closed in 2002. In fact, it changed its name to SamEric in its dying days, but the public remembers it as the Boyd, one of ten movie palaces in center city. The definition of a "palace" is arbitrary but is generally taken to be a theater with more than a thousand seats, normally with hyperbolic architecture to fit its hyperbolic advertising. Scholars of the matter say the earliest movie houses were constructed in Egyptian style, soon evolving into French Art Deco. Ornate, whatever it's called.

The palace concept developed in the era of silent films, with subtitles. Anyone who has experimented with home movies knows that the silent film sort of lacks something, particularly between reels and at times of breakdown in the projection. That's why brass bands played on the sidewalk outside, pipe organs played during intermissions, and all manner of vaudeville appeared on stage. Sound movies, or talkies, were immediately much more popular when they appeared in 1927, and had less need of the window dressing from other distractions which had grown into a moviehouse tradition which was slow to die.

The movie studios owned the films and soon built theaters to display them. The movie business was quite profitable from the start, so studios had the necessary finance to spread a network of very large theaters across the country quickly. The ability to concentrate hyped-up advertising with immediate display of the product in large captive theaters tended to drive the model of the "palace", which was able to sustain higher ticket prices than trickling a larger number of film copies to myriads of small "mom and pop" local theaters. In very short order, going downtown to see movies became at one time the largest reason for suburbanites to go to the center of town on public transportation, fitting in nicely with the concentration of huge department stores, also located there. Restaurants, bars, bowling alleys, and shops grew up to address the crowds. Furthermore, the economic depression of the 1930s slowed down what was to become a relentless automobile-flight to the suburbs. After the spread of free television at home in 1950, the downtown movie palaces were doomed. The legal profession helped, too. Small suburban theater operators eventually won an antitrust suit against what they described as monopoly power of studio-owned center city palaces, so a host of small sharks in the suburbs started to eat the whales downtown. Furthermore, the sound quality was easier to achieve in a smaller auditorium. To tell the truth, fire hazard was also lessened without the arc-lamps needed to project images across a long distance.

So, a new technology interacting with an old theatrical tradition quickly created the movie industry in its downtown movie palace form; more advancing technology quickly destroyed it, with a little help from economics and politics. Good luck to the friends of this historical epoch, who have a monumental task ahead to work up the public nostalgia and political strength required to overcome a huge economic obstacle of the "highest, best use of the land". In many ways, the most valuable contribution of this movie palace restoration movement is to dramatize in the public mind just how urban centers function. Department stores are gone, going in town to the movies is over. How else are you now going to get the couch potatoes to go downtown voluntarily, and often? Just imagine ten palaces simultaneously filling up with several thousand suburbanites apiece, seven nights a week. Without those additional drawbacks on ample display in Atlantic City and Las Vegas, please.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1190.htm

Central Bankers Refine the Art of Diplomacy

Nancy Wentzler, Deputy Controller of the U.S. Currency, recently dramatized the arcane world of international currency exchange for the Global Interdependence Center's 25th annual Monetary and Trade Conference, held this year at Drexel University. For the most part, controlling currency operates flawlessly as far as the rest of us can tell. But every few years a sudden banking crisis pops up somewhere, pressuring a lot of bureaucrats in many countries to act quickly without a fire drill. Displaying panic could spread into world financial collapse, but so could acting too slowly. There's often a need for that most conflicting of all predicaments, the clear need to act outside of established channels. Hedge funds and private equity funds greatly increase the pace of banking panics, and if panic-stricken, can now send multi-billions from one place to another in fractions of a moment. In that same moment, everybody involved is in a meeting, or else frantically calling somebody. Even if the right person is identified, located, and takes the call, there is natural hesitation to take risky advice from a stranger without an identifiable track record. Protocol-driven supervisory bureaucracies may be suddenly forced to contend with professional traders whose whole life consists of calls roughly like this: "Hi, Joe, this is Bill. Buy me a gazillion shares of XYC at the market." To which Joe's answer commonly would be, "You got it. Thanks for the order, Bill. 'Bye. "

|

|

Benjamin Franklin at the French Court |

The potential for sudden fires calls out for fire drills. It also calls for the prior establishment of social networking among those who may have to depend on each other in a crunch. Whether by repeatedly dealing with each other or by social gatherings, or even just by immersing in trade gossip, it must somehow become possible for them to make a quick assessment of the person on the other end of the phone. Is the sound or flighty, can he be depended on to keep his word, or will he take for the hills.

Well, it sounds like a diplomatic corps, doesn't it? For the briefest of moments, one person represents the views of his country. The rest of his life is spent preparing for that moment. The most familiar American example is Benjamin Franklin, for eight years our ambassador to France. Franklin received heavy criticism for spending American money on social functions in Paris. John Adams, in particular, was outraged to see Franklin engaged in a constant series of dinners, balls, Royal parties, and salons; he was obviously having the time of his life, year after year. After all, he really only accomplished two tangible things -- he signed the Alliance with France which effectively won the war, and he signed the Treaty of Paris where Britain agreed to stop fighting.

U.S. and E.U. Exchange Experiences (1)

THE Global Interdependence Center (GIC), founded by Nobelist Lawrence Klein in 1976, brings noted foreign financiers to address Philadelphians interested in finance, and takes those Philadelphians abroad to return the visits. It's a gracious, entertaining, and highly stimulating travel club of very nice folks. Its 25th Annual Monetary and Trade Conference (in 2001) was especially exhilarating. Christian Noyer, President of the Banque de France, gave a description of the rationale and direction of the European common currency. Since he was the Euro's driving force right from the beginning, the experience of hearing him was pretty much like hearing Alexander Hamilton tell the story of the founding of the American banking system. Such a notable event needs to be reported.

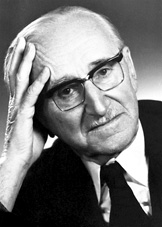

|

| Christian Noyer |

Christian Noyer urged that the central concept of the European Union is deliberate, voluntary surrender of national sovereignty -- for a mutually beneficial purpose. The declared purpose of the limited surrender of national control of the currency is economic; price stability, lower interest rates, the stimulation of international trade by lowering transaction costs. But the unstated, grander, purpose is the elimination of war. Because the limited technical purpose has been achieved in almost all areas, the grander purpose of eliminating war has not been an accident. With this simple, even humble, declaration it immediately becomes possible for a mildly irritated American audience to understand that European reluctance to become our active military ally grows out of a highly commendable set of motives, and widely differing historical experiences.

<As things worked out, the new nations who have recently joined the Union ("The U") are anxious to modernize, because the people of those nations demand modernization and their leaders must agree to achieve it. Inflation, that hitherto inevitable fund-raiser for national governments, must be eliminated in order to join and stays eliminated because the other members of The U will not tolerate it in a partner. In his curious way, "price stability" has placed the Union on the side of the people against the locally powerful, although it would be untactful to emphasize it. From the elimination of inflation comes lower interest rates, and from that, a stable currency. From that comes economic growth, for which the political lingo seems to be "modernity". As a consequence of this undeniable success, all nations in the area want to join the Union, and none wants to leave it. If that prevailing attitude doesn't lead to the elimination of what might then be a civil war, it's hard to know what will eliminate it. The marvel of all this skillful analysis is how natural, soft and modest it sounded, feeling like an old soft shoe. Eventual political unification is clearly an old dream in Noyer's head, but for now, he seems content with the vindication that it is possible to have a currency without having a country control it. It seems to be a steamroller of economic logic, flattening out the pretenses of merely political power.

No less an economist than Martin Feldstein has written that stable unified currency is doomed in the European context of widely diverse labor markets; Noyer seems pleasantly serene in the face of this argument. He wouldn't say so, of course, but some in the audience got the idea that Noyer probably believes the power of this cooperative idea will eventually discipline the unions the way it disciplined the politicians. One certainly hopes so, for the sake of this smooth, likable French aristocrat.

Compromise Outside the Borders of a Debate

|

| Cardinal Mazarin |

For example, the north European states, Germans, in particular, must resign themselves to subsidizing the Mediterranean nations for years to come, working a hard work ethic while they watch their wards live an easier one. But it can be accomplished; New England has been subsidizing Mississippi for more than a century, and Appalachia has been fighting the rest of the country's wars for them since 1860. The South was always more feudal, had a more distinct class system, had a culture of upper-class military schools, whereas the North had a background of largely religious reasons for emigrating to the New World. Lincoln, for example, was an ardent Whig, which in those days meant an advocate of helping commerce by the intervention of government. That is essentially a 17th Century French idea, said to originate with Cardinal Mazarin and Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Whether it is useful to continue the same idea for four later centuries is an emotional issue in a class with our own reluctance to change a word of the Constitution. There is even a shadow of present concern that Americans will have so forgotten the lessons of free interstate commerce that they might somehow surrender it for some other blandishment. Certainly, free international trade has its enemies. The abolition of slavery was, of course, an overdue achievement, too, but perhaps our long slog toward equal rights has allowed this second crusade to overshadow the history of what really was the main one. In case anyone feels impelled to start a quarrel about this viewpoint, let me remind him that Quakers started the abolition movement, right here in Philadelphia, and have nothing to apologize about, for maintaining the Union was a more important justification for Civil War that was the abolition of slavery.

|

| Jean-Baptiste Colbert |