Related Topics

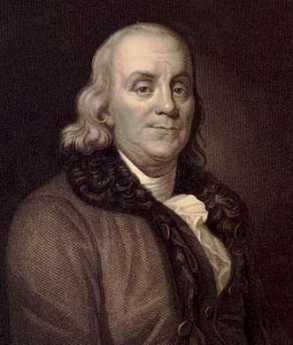

Benjamin Franklin

A collection of Benjamin Franklin tidbits that relate Philadelphia's revolutionary prelate to his moving around the city, the colonies, and the world.

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation were written by John Dickinson, modified by others. Officially unratified for five years, the country was ruled under them in Philadelphia, for thirteen. They taught many lessons, which we sometimes forget we had experienced.

Robert Morris: Think Big

Robert Morris wasn't born rich, or especially poor, but he was probably illegitimate. He had no recollection of his mother; his father, a tobacco trader in England, emigrated to Maryland and died rather young. It didn't take long for young Robert to become one of the richest men in America.

Robert Morris: The Dark Side

The richest man in America suddenly was locked in debtor's prison, $12 million in debt. While in prison, he reduced that to $3 million, and got released under a new bankruptcy law he helped devise.

Revolution in New Jersey

Early, brief but significant.

Those Troublesome Lees of Virginia

|

| Richard Henry Lee |

SOMETHING useful can, of course, be learned from a man's friends, but descriptions given by his enemies are usually briefer. The Lee family of Westmoreland County Virginia were bitter enemies of Robert Morris the Financier of the Revolution, and they surely said some unfair things about him. Morris paid as little attention to the Lees as possible, but for generations, the Lees had been neighbors of the Washingtons, and so could not be completely brushed aside. Furthermore, they were close to the center of Thomas Jefferson's anti-Federalist party. So insights into the Lee family probably illuminate the main disputes before, during, and after the Revolution. They even illuminate the mixed character of George Washington, who was sometimes unusual by Virginia standards. Nevertheless, the Lees had the same quality of heedless idealism to be found in Samuel Adams of Massachusetts and Patrick Henry of Virginia which goes beyond the ability of two-feet-on-the-ground revolutionaries like Robert Morris and Benjamin Franklin to understand, or even abide; this conflict runs throughout the history of the American founding. It seemed to baffle even those who switched positions, like James Madison going in a leftish direction, and Thomas Paine, going toward the right. So, although reckless idealism cannot be an inborn character, it must quickly acquire very deep roots.

.jpg)

|

| Arthur Lee |

Arthur Lee and his brothers William and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, were passionate rebels of the Patrick Henry ("Give me liberty or give me death") sort, intermittently reviving lifelong attacks on Robert Morris. Highborn Tidewater aristocrats, they were ancestors of Virginia's revered General Robert E. Lee. Arthur had even attended Eton College and later studied medicine in England. The Lee brothers started attacking Robert Morris well before his famous abstention from the critical 1776 vote on independence. It's much too easy to shrug the Lees off as landed aristocrats who disdained self-made men, or as passionate Jacobins who hated self-made rich people, or maybe just narrow-minded nuts. Out of their often inaccurate attacks emerges an outline of what a lot of other people thought about Robert Morris. Many of these polar mind-sets outline the main divisions of political strife in America right up to the present. For present purposes, let's try to understand why Morris might risk his substantial fortune in underground smuggling before the war, and then dedicate his huge energies to winning the war -- while at the same time, not only refuse to agree to the Declaration of Independence (he did finally sign it in August 1776), but speak out in public opposition to independence. What explains Morris' apparent double-talk?

<The explanation I choose to accept is that Robert Morris' real feelings were too sophisticated for this particular crisis, reaching clearer expression in his later activities promoting the Articles of Confederation and its revision the United States Constitution. A man given to terse one-liners, Morris said in December 1775 that he joined his fellow Americans in striving for "Constitutional Liberty" but could not join them in promoting independence.

Morris was never explicit about what would achieve Liberty without Independence; perhaps something like the independent Irish parliament which English Whigs then supported, or the Scottish local parliament which exists today, was in his mind. Both of them link a single King to a commonwealth. At the time, no one was interested in the political philosophy of a shipping merchant.

But today we are in a position to see no member nation of the British Commonwealth has a written constitution; written constitutions are a comparatively recent innovation and not necessarily an essential one. The American Constitution today continues to argue about original intent and living documents, so it is still possible to prefer the wisdom of a benign King to written constitutions. The British goal seems to be to infuse overarching principles of government so deeply into citizen minds that such principles overwhelm any written commandments, however vague all that may sound to outsiders who prefer to niggle over documents. Not in America, of course, because an immigrant nation like ours cannot grow cultural roots sufficiently deep in a few generations, and must have written rules. Great Britain's recent difficulties with immigrants from the Commonwealth may well reassert the limits of unwritten constitutions; constant questioning of the written American constitution by more recent immigrant groups may become a part of the British life, too.

The Articles of Confederation were written by the eminent lawyer John Dickinson, said to be the man closest to sharing Robert Morris' political philosophy. However, for five years the Articles were unratified, and Morris began to believe this lack of ratification was the reason the states were so resistant to taxation. So Dickinson gets credit for writing the Articles, but Morris must be seen as their father. Believing the lack of federal taxation was the main difficulty, and blaming the unratified Articles as the reason for it, our businessman man-of-action pushed them through. Unfortunately, with the Articles it didn't work because the taxation problem still remained, so Morris turned his immense energies toward replacing the Articles with something which would work. It does not twist American history a great deal to believe that Robert Morris, Jr. was one of the main driving forces behind both the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution of the United States. He was neither a lawyer nor a political scientist and therefore was quite indifferent to who got credit for the documents. As Ronald Reagan was to discover two centuries later, that's one of the best ways to get anything done.

Morris could read; he knew the Articles didn't endorse Federal taxation. But he was apparently convinced an unwritten constitution always contains the latitude to do what simply has to be done; anything else amounts to shooting yourself in the foot. After the Battle of Trenton, when Morris became President of the United States for three months in everything except name, he still blamed his troubles on the inability to levy taxes, which in turn was due to failure of the states to ratify those Articles. So sensible a man as John Dickinson would never assume overly strict interpretation was intended; obviously, a state must confiscate private property when otherwise it cannot survive. After five years of state inaction, Morris abruptly pushed the Articles through to ratification. But he was wrong, it didn't help. When he finally grasped that the explicit limitations on taxation were intentional, intended to override any implicit power in the Articles whatever, he promptly threw his weight behind John Jay, George Washington, and James Madison to support a new Constitutional Convention setting it right, especially the national government's ability to levy taxes. Since Washington had by then become his best friend, who actually lived next door in Morris' Market Street house for years, there is not much paper trail of this interaction between these old friends. Once he got his tax mandate at the Convention, however, Morris had hardly anything further to say. His frenetic later activity immediately after the Constitution was enacted can almost surely be attributed to lifelong habits of a negotiator, avoiding mention of anything which might distract from his main goal, in this case of ratifying the Congressional right to levy federal taxes, but not abandoning subordinate goals for a moment. What the Lees hated about Morris, therefore, cannot be easily explained, but certainly, one feature of it was his ability to hold his cards face-down. The Lees didn't hold their cards, they flourished them. In their eyes, no gentleman would do anything else.

The incidents of June 1776 place the Lees in a more favorable light if they are seen as urging instinctive decisions by popular mandate, essentially favoring an unwritten British Constitutional arrangement. The Lees believed the place of a gentleman was at the head of a troop, daring the rest to follow their lead. The British had blockaded Boston, passed the Prohibitory Acts, fought naval battles in the Delaware River in May of that year. A huge British fleet had landed in New York harbor, and the agitated colonists were about to declare war. At the very moment of crisis, that rich Philadelphia merchant had refused to vote for independence. The Virginia tobacco planters were dancing a war dance in a city known for its pacifist Quakers, while their neighbor George Washington was conducting an actual war with the British. It was then revealed that Robert Morris had been participating in a gunpowder smuggling operation known as the Secret Committee, and Morris had made considerable profits from it. While many of his friends defended Morris, it was pretty easy to go wild with indignation about trusting him to sit on a secret espionage committee, unwatched. The very least that could be done was to appoint Arthur Lee, already a member of the Continental Congress, to that Secret Committee to sound the alarm if anything looked funny. The ironic fact seems to be that Morris and the Lees were passionately committed to the same unwritten approach to government, primarily based on trust in personal character, otherwise defined as fidelity to an unwritten tribal code. If you are the right sort of person, you will be with us; if you are not with us, you must not be the right sort of person. Unfortunately, a nation of immigrants may not survive if it adopts too many such notions.

The Lees had expressed disruptive views of Morris in the past, but they were exactly the sort of clan likely to confront scoundrels whenever facts called for it, and sometimes even when they didn't. The underlying conflicts, fiercely advocating both a strong centralized government and a loose decentralized one but not defining either, continue to run through American politics until the present. Whether Morris ever acknowledged it or not, he ended up on the side of defined contracts, as opposed to a Code of Honor. But he spent his life as a man of his word because in business your word is your bond; if you are any good, you won't need to cheat. If our Tower of Compromises is to endure, its limits of such agreement must be few, but they must somehow be strictly understood.

Originally published: Thursday, April 19, 2012; most-recently modified: Friday, September 20, 2019